Abstract

Cell polarity in the adult mammalian testis refers to the polarized alignment of developing spermatids during spermiogenesis and the polarized organization of organelles (e.g., phagosomes, endocytic vesicles, genetic materials, Golgi apparatus) in Sertoli cells and germ cells to support spermatogenesis. Without these distinctive features of cell polarity in the seminiferous epithelium, it is not possible to support the daily production of millions of sperm in the limited space provided by the seminiferous tubules in either rodent or human males through the adulthood. In short, cell polarity provides a novel mean to align spermatids and the supporting organelles (e.g., phagosomes, Golgi apparatus, endocytic vesicles) in a highly organized fashion spatially (and/or temporally) in the seminiferous epithelium during the epithelial cycle of spermatogenesis, analogous to different functional assembling units in a manufacturing plant such that as developing spermatids move along the “assembly line” conferred by Sertoli cells, different structural/functional components can be added (or removed for degradation or recycling) to the developing spermatids during spermiogenesis so that functional spermatozoa are produced at the end of the assembly line. Herein, we briefly review findings regarding the regulation of cell polarity in the testis with specific emphasis on developing spermatids, supported by an intriguing network of regulatory proteins along a local functional axis. Emerging evidence has suggested that cell cytoskeletons provide the tracks which in turn confer the unique assembly lines in the seminiferous epithelium. We also provide some thought-provoking concepts based on which functional experiments can be designed in future studies.

Keywords: Testis, cell polarity, spermatids, Sertoli cells, actin nucleation, actin, microtubules, cytoskeleton, spermatogenesis, seminiferous epithelial cycle, ectoplasmic specialization, blood-testis barrier

Introduction

In the mammalian testis, developing germ cells, in particular elongating/elongated spermatids, and Sertoli cells display remarkable cell polarity throughout the seminiferous epithelial cycle of spermatogenesis in rodents and humans (1, 2). For instance, the heads of all elongating spermatids point towards to the basement membrane with their tails to the tubule lumen (Figure 1). On the other hand, Sertoli cell nuclei, Golgi apparatus, tight junctions (TJs) and basal ectoplasmic specialization (basal ES, a testis-specific actin-rich adherens junction (AJ) type) are located near the base of Sertoli cells, almost adjacent to the basement membrane of the tunica propria (1, 3–5). This strict orientation of developing spermatids and Sertoli cell-based ultrastructures thus facilitate the maximal number of spermatids to be packed within the confined and limited space of the seminiferous tubules and they can also be supported by a fixed population of Sertoli cells functionally in the testes (3, 6). As such, ~30–50 million vs. ~200–300 million of sperm (7–9) can be produced daily in each adult rodent or human male through spermatogenesis during adulthood. The concept of apico-basal polarity conferred by the concerted efforts of the three polarity protein complexes is known for decades, which is essential to embryogenesis and morphogenetic development of multiple organs include the testis, and multiple cellular functions (10–15). However, the presence of polarity proteins in the testis that are crucial to spermatogenesis was not reported until 2008 when the Par (partitioning-defective)-based polarity complex of Par3/Par6/aPKC (atypical protein kinase C)/Cdc43 was first identified in the rat testis (16). Thereafter, the presence of Scribble/Dlg1 (Discs large)/Lgl2 (Lethal giant larvae) polarity complex (17), to be followed by the Crb3 (Crumbs homolog-3)-based complex (18), in the testis were reported in subsequent years. The reason that we sought to examine the likely involvement of cell polarity in spermatogenesis stems from the initial observation that when adult Sprague-Dawley rats treated with a single dose of adjudin, a male contraceptive under investigator in our laboratory (19, 20), by oral gavage were found to induce considerable disarray in the alignment of elongating/elongated spermatids across the seminiferous epithelium (16). For instance, the heads of developing spermatids no longer aligned perpendicular to the basement membrane but deviated by as much 90° to 180° from the intended orientation versus spermatids in normal testes (16). Furthermore, this defect in spermatid polarity occurred within ~6–12 hr, at least 12–24 hr before extensive exfoliation of germ cells from the seminiferous epithelium took place in the testis (16) (Figure 1). These findings thus implicate that there may be a functional relationship between spermatid polarity and the underlying cytoskeletons that confer spermatid adhesion. When the actin microfilament organization at the Sertoli-spermatid interface, which is known as the apical ectoplasmic specialization (ES), was examined by electron microscopy, considerable truncation of actin microfilaments was detected (16). As such, F-actin no longer capable of supporting spermatid adhesion and spermatid orientation, leading to their eventual premature release from the testis. This concept that relates the function of polarity proteins and the involvement of cytoskeletal organization in mammalian cells and tissues is indeed supported by studies in other epithelia (21–23).

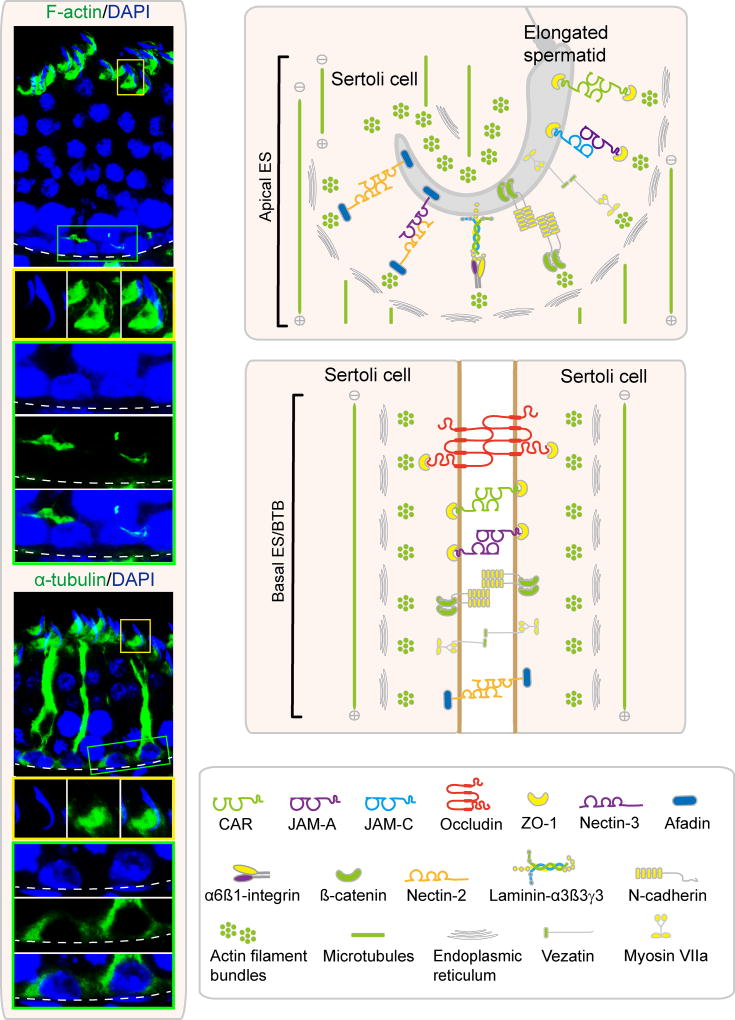

Figure 1. Role of actin- and microtubule (MT)-based cytoskeletons to support cell polarity and spermatogenesis in the mammalian testis.

On the left/top panel, the micrographs illustrate the organization of F-actin (green fluorescence, visualized by Alexa Fluor 488 phalloidin) across the seminiferous epithelium in a stage VII tubule with the localization of F-actin at the apical ES and basal ES/BTB enlarged in the yellow and green boxed areas, respectively, and shown below. On the left/bottom panel, the micrographs illustrate the organization of α-tubulin (the building blocks of microtubules (MTs); green fluorescence, visualized by an anti-α-tubulin antibody and an Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated secondary antibody) across the epithelium in a stage VII tubule with the localization of MT at the apical ES and basal ES/BTB enlarged in the yellow and green boxed areas, respectively, and shown below. Cell nuclei were visualized by DAPI. The MT-conferred tracks to support cell and organelle transports are distinctively noted. Scale bar, 80 µm; insets (in yellow or green), 25 µm; which apply to corresponding micrographs/insets. On the right panel, it is the schematic drawing illustrating the organization of actin microfilaments and MTs that support the apical ES and also basal ES which is also an integrated component of the BTB. Also shown as the several known cell adhesion complexes in both sites.

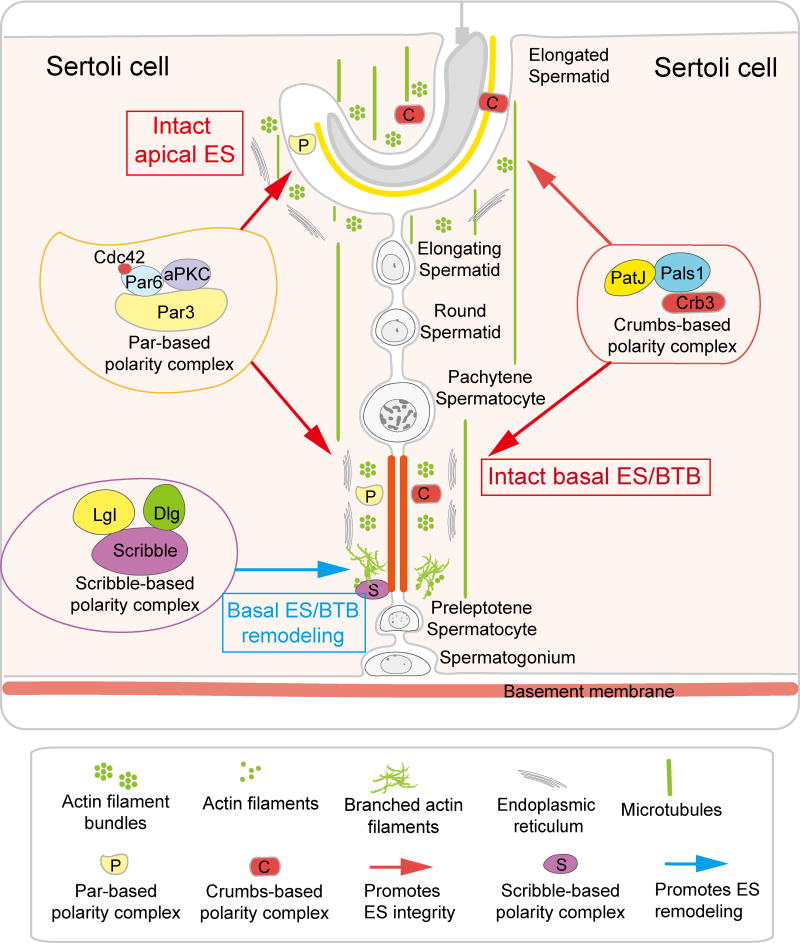

In this earlier report, it was shown that a knockdown of Par3 or Par6 by RNAi indeed perturbed the localization of adhesion proteins at the Sertoli cell-cell interface (16). For instance, Par3 or Par6 knockdown induced re-distribution of JAM-A (Junctional Adhesion Molecule-A, also known as JAM-1, a TJ integral membrane protein (24)) and α-catenin (a basal ES adaptor protein (25, 26)) so that these proteins no longer localized tightly to the Sertoli cell-cell interface to support the Sertoli TJ-permeability barrier function (16). These findings also implicated that the F-actin organization in Sertoli cells had been disrupted since both TJ- and basal ES-based adhesion proteins utilize F-actin for attachment. The concept that polarity proteins exert their regulatory role in conferring spermatid polarity in the testis through changes in cytoskeletal organization is supported by two subsequent reports when the role of Scribble (17) and Crb3 (18) in the testis was examined. For instance, a knockdown of Scribble/Dlg1/Lgl2 was found to promote the organization of F-actin at the Sertoli cell basal ES/BTB, making the BTB “tighter” (17) whereas Crb3 knockdown perturbed actin organization at the apical and basal ES, perturbing the Sertoli cell BTB function, making the Sertoli cell TJ-barrier “leaky” (18). In short, in normal testes, the Par3/Par6- and the Crb3-based polarity complex confer apical and basal ES integrity, promoting spermatid and Sertoli cell adhesion and polarity by organizing actin microfilaments at the ES to support adhesion and polarity function (Figure 2). On the other hand, the Scribble/Dlg1/Lgl2 polarity complex promotes apical and basal ES disruption (Figure 2) during the epithelial cycle of spermatogenesis. In short, the functionality of the Par3/Par6- and Crb3-based polarity complexes and the Scribble-based polarity complex are antagonistic, and they mediate their regulatory effects through changes in actin microfilament organization at the ES as noted in Figure 2.

Figure 2. A schematic drawing that illustrates the contrasting roles of the Par- and Crumbs-based polarity complexes vs. the Scribble-based polarity complex to support ES dynamics in the testis.

It is noted that both the Par- and Crumbs-based polarity complexes and their component proteins support apical and basal ES integrity whereas the Scribble-based polarity complex (and its component proteins) promotes ES disruption (see text for details). Abbreviations used: aPKC, atypical protein kinase C; Cdc42, cell cycle division 42; CRB, Crumbs; CRB3, Crumbs homolog-3; Dlg, discs large; ES, ectoplasmic specialization; Lgl, lethal giant larvae; Par3, partitioning-defective; Par6, partitioning-defective 6; Pals1, protein associated with Lin-7 1; PatJ, Pals1 associated tight junciton protein.

Ectoplasmic specialization (ES), cell polarity and cytoskeletal function in the testis

It is noted that ES is a testis-specific atypical adherens junction (AJ) since it is constituted by proteins usually found at the TJ (e.g., JAM-A, JAM-C), gap junction (e.g., connexin 43), and even focal adhesion complex (FAC, also known as focal contact restricted to the cell-extracellular matrix interface) (e.g., p-FAK-Tyr397 (phosphorylated/activated focal adhesion kinase at Tyr-397 from the N-terminus), p-FAK-Tyr407), as well as putative AJ adhesion protein complexes (e.g., nectin-afadin) (27, 28). On the other hand, some of the best studied AJ adhesion protein complexes found in other epithelia, such as N-cadherin/β-catenin are only stage-specifically expressed at the apical ES at the Sertoli-spermatid interface at stage VII-early VIII tubules (29). However, N-cadherin/β-catenin remains conspicuously expressed at the basal ES at the BTB in virtually all stages of the epithelial cycle (29, 30), utilizing actin for attachment as in other epithelia (30). In the mammalian testis, ES is restricted to the Sertoli-spermatid (step 8–19 or 8–16 spermatids in rat or mouse testes) interface in the adluminal compartment designated apical ES (31–33). Once apical ES appears in stage VIII tubules between Sertoli cells and step 8 spermatids, it replaces all other anchoring junctions at the site, including desmosome and gap junction, becoming the only anchoring device from step 8 spermatids through step 19 in the rat testis to support spermiogenesis. However, ES is also found at the Sertoli cell-cell interface near the basement membrane which is a major constituent junction type of the blood-testis barrier (BTB) (34–37). But in sharp contrast to the apical ES, basal ES coexist with TJ and gap junction, which together with the intermediate filament-based desmosome, these junctions constitute the BTB. The most notable feature of the apical ES is the prominent array of actin microfilaments assembled into bundled that tightly arranged between the apposing Sertoli-spermatid interface and the cisternae of endoplasmic reticulum at the apical ES (Figure 1). For basal ES, there are two arrays of actin filament bundles sandwiched between the apposing Sertoli cell plasma membranes and the cisternae of endoplasmic reticulum (Figure 1). This array of actin microfilament bundles at the apical ES also confers one of the strongest adhesive strength to the ES, almost twice as strong as the desmosome when the force required to disrupt apical ES vs. desmosome was quantified (38). This finding is unusual since desmosome (a cell-cell intermediate filament based anchoring junction found in skin between keratinocytes) is considered to be one of the strongest anchoring junctions in mammalian epithelia outside the testis (39, 40). Interestingly, adjudin primarily targets apical ES, capable of disrupting this anchoring junction in the testis in preference to the desmosome at the Sertoli cell-step 1–8 spermatid interface (41). While the apical and basal ES are also indistinguishable by electron microscopy except that apical ES has a single array of actin filament bundles vs. two arrays of actin filament bundles, the constituent proteins are considerably different (Table 1).

Table 1.

Different types of constituent adhesion protein complexes at apical and basal ES in rodent testes*

| Junction type | Location | Protein complex | Main constituent proteins |

|---|---|---|---|

| Apical ES | Sertoli cell-spermatid (step 8–19 spermatids in rat or step 8–16 spermatids in mouse testes) | Integrin-laminin | α6β1-integrin-laminin-α3β3γ3 |

| Nectin-afadin-ponsin | Nectin-2/3-afadin | ||

| Cadherin-catenin | N- (or E-) cadherin-β-catenin | ||

| Vezatin-myosin | Vezatin-myosin VIIa | ||

| JAM- or CAR-ZO-1 | JAM-C-ZO-1; CAR-ZO-1 | ||

| Basal ES | Sertoli-Sertoli cell | Cadherin-catenin complex | N-cadherin-β-catenin |

| Nectin-afadin-ponsin complex | Nectin-2-1-afadin | ||

| Vezatin-myosin complex | Vezatin-myosin VIIa | ||

| JAM- or CAR-ZO-1 | JAM-A-ZO-1; CAR-ZO-1 |

Abbreviations: CAR, coxsackie and adenovirus receptor (a TJ integral membrane protein in the testis); ES, ectoplasmic specialization; JAM, Junctional Adhesion Molecule; ZO-1, zonula occludens-1.

Spermatids, from step 8 to 19 spermatids or 8 to 16 spermatids in the rat or mouse testis, respectively, are highly polarized cells in which their heads are aligned perpendicular to the basement membrane and their tails point towards the tubule lumen (Figure 1). Since the only anchoring device at the spermatid-Sertoli cell interface is apical ES, it is logical to speculate that apical ES confers spermatid polarity during the entire phase of spermiogenesis. Thus, basal ES at the Sertoli cell-cell interface that constitutes the BTB also likely contributes to Sertoli cell polarity even though there are other cell junctions at the BTB. Indeed, it was subsequent shown that both Sertoli and germ cells express virtually all three polarity protein complexes and their corresponding binding/functional partners, such as the Par-based complex and its binding partners (e.g., Par3, Par6, aPKC, Cdc43), the Crb-based complex and its binding partners (e.g., Crb3, Pals1 (protein associated with Lin-7 seven 1), PatJ (Pals1 associated tight junction protein)), the Scribble-based complex (e.g., Scribble, Dlg1, Lgl2) (Table 2). Furthermore, many of these proteins display stage-specific localization in the seminiferous epithelium during the epithelial cycle, and they likely exert their regulatory roles through their effects on the cytoskeletal function are summarized and evaluated in the following sections.

Table 2.

Component proteins, their localization and function of the three polarity protein complexes in rodent testes*

| Polarity protein complex | Constituent protein | Location | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Par-based polarity complex | Par3, Par6, aPKC, Cdc43, 14-3-3 (also known as Par5) | Apical and basal ES | Interacts with apical ES adhesion protein complexes; support F-actin organization, spermatid polarity and adhesion |

| Scribble-based polarity complex | Scrib, Dlg1–4, Lgl1/2 | Basal ES (stage VII–VIII) | Promotes BTB remodeling |

| Crumbs-based polarity complex | Crb3, Pals1, PATJ | Apical and basal ES | Supports F-actin network, basal and apical ES function and spermatid adhesion |

Abbreviations used: aPKC, atypical protein kinase C; Cdc42, cell cycle division 42; CRB, Crumbs; CRB3, Crumbs homolog-3; Dlg1–4, discs large1–4; ES, ectoplasmic specialization; Lgl1/2, lethal giant larvae 1/2; Par3, partitioning-defective; Par6, partitioning-defective 6; Pals1, protein associated with Lin-7 1; PatJ, Pals1 associated tight junciton protein; Scrib, Scribble.

The Par-based polarity complex and cytoskeletal function

The role of Par-based polarity complex in modulating mammalian cellular function is well established (14, 42–44). In the testis, Par6 is localized at the apical and basal ES at the spermatid-Sertoli and Sertoli cell-cell interface, respectively, in virtually all stages of the epithelial cycle in the rat (16). Par6 localization at the apical ES is almost superimposable with nectin 3 (16), a spermatid-specific apical ES protein (and an integral membrane protein) in the testis (45, 46). Par6 also co-localizes well with occludin (a BTB-specific integral membrane protein (47)) at the basal ES/BTB (16). However, a considerable down-regulation of Par6 was noted following treatment of adult rats with adjudin (50 mg/kg b.w., by oral gavage), and this was associated with considerable defects in spermatid polarity across the entire seminiferous epithelium in which groups of elongating/elongated spermatids had their heads pointed at least 90° to 180° away from the basement membrane, to be followed by extensive spermatid exfoliation from the testis. Interestingly, the organization of actin filaments at the apical ES was grossly perturbed in which actin filaments were truncated and dissociated from the bundles, making the actin failed to support adhesion protein complexes at the site (16). Furthermore, a specific knockdown of either Par3 or Par6 by RNAi also grossly perturbed the localization of either JAM-A (a TJ integral membrane protein) and α-catenin (a basal ES adaptor protein) since these proteins no longer tightly associated with the Sertoli cell cortical zone, but diffusely localized at the site, being re-distributed to the cell cytosol. Since these proteins all utilize actin for attachment, their mis-localization supports the notion that the F-actin organization has been compromised following Par3 or Par6 knockdown (Table 2). These findings also suggest that the Par-based polarity complex in normal testis promotes apical and basal ES/BTB integrity through proper organization of F-actin cytoskeleton since its knockdown would impede organization of ES proteins at the Sertoli cell cortical zone. Taking collectively, these data also suggest that the Par-based polarity protein complex supports spermatid polarity and adhesion via its interaction with apical ES adhesion protein complexes, and it exerts its regulatory role through changes in the organization of actin filaments at the ES.

The Scribble-based polarity complex and cytoskeletal function

The Scribble-based complex is another important polarity protein complex module known to regulate multiple cellular functions including tumorigenesis (5, 14, 48–50). Unlike Par6, Scribble is localized predominantly at the basal ES/BTB in adult rat testes, but more robust expression at the BTB is detected at stage VII-VIII of the epithelial cycle (17), at the time when BTB undergoes remodeling to facilitate the transport of preleptotene spermatocytes across the immunological barrier (1, 51). These findings also suggest that a down-regulation of Scribble may promote BTB integrity. Indeed, a knockdown of the Scribble polarity complex by RNAi using siRNA duplexes specific to Scribble, Dlg1 and Lgl2 (i.e., a triple knockdown) was found to promote the Sertoli cell TJ-permeability barrier, making it “tighter” (17) (Table 2). When the Scribble/Dlg1/Lgl2 in the testis was also silenced by RNAi in vivo, it was found that occludin remained robustly expressed at the basal ES/BTB in late stage VIII tubules (17) when it should have been considerably down-regulated to support the transport of preleptotene spermatocytes at the immunological barrier (52). A careful examination of actin organization at the BTB discovered that the F-actin remained robustly expressed even at late stage VIII tubule when it should have been considerably down-regulated to facilitate BTB remodeling (17). These findings thus provide the compelling evidence that the Scribble-based polarity protein complex, unlike the Par-based polarity complex, promotes BTB remodeling during the epithelial cycle under physiological conditions. As such, it is robustly expressed at the basal ES/BTB in stage VII–VIII tubules when the BTB undergoes remodeling, and its silencing by RNAi promotes BTB integrity by tightening the Sertoli cell TJ-barrier function.

The Crumbs-based polarity complex and cytoskeletal function

Similar to other mammalian epithelia in which the Crumbs-based polarity protein complex plays a prominent role in conferring cell polarity and in modulating multiple cellular functions (44, 53, 54), the testis is also known to express the Crumbs-based polarity complex (18). The Crumbs homolog in the rat testis is Crb3, which is restrictively expressed at the basal ES/BTB and co-localizes with N-cadherin in virtually all stages of the epithelial cycle (18). Unlike Par6, Par3 and Scribble which are cytosolic proteins, Crb3 is a small integral membrane protein, besides localized at basal ES/BTB, it was also associated with the stalk-like structures across the base of the seminiferous epithelium conferred by either F-actin or MTs to support the transport of spermatids and cell organelles (e.g., endosomes, phagosomes) (18) (Table 2). Interestingly, PATJ, a binding partner of Crb3, is also expressed at the basal ES/BTB in virtually all stages of the cycle, but most prominently in stage VII tubules and also robustly expressed at the apical ES (but limited to stage VII tubules) (18). A knockdown of Crb3 by RNAi was found to perturb the Sertoli cell TJ-permeability barrier function via changes in the distribution of TJ (e.g., CAR, ZO-1) and basal ES proteins (e.g., N-cadherin, β-catenin) (18), making its functional role similar to Par3-based polarity protein that they both promote apical ES and basal ES/BTB integrity under physiological conditions (Figure 2). But the function of the Crumbs- and Par-based polarity complexes is in sharp contrast to the Scribble-based polarity protein complex which promotes BTB remodeling, illustrating the effects of Par- and Crb3-based complexes are antagonistic to Scribble-based complex regarding their regulatory role on basal ES/BTB dynamics (Figure 2). However, these findings are in agreement with the role of the Par- and Crb-based polarity complexes vs. Scribble-based polarity complex in other epithelia/tissues, wherein the Par- and Crb-based polarity complexes are mutually exclusive with the Scribble-based complex regarding their localization and functionally. For instance, the Par- and Crb-based complexes are localized near the TJs at the apex of epithelial cells whereas the Scribble is found near the base of epithelial cells (55). Additionally, Crb3 was shown to exert their disruptive effects on the Sertoli cell TJ-permeability barrier following its knockdown through changes in the organization of actin microfilaments across the Sertoli cells in which actin filaments were considerably truncated, failing to support adhesion protein complexes at the ES (18). An in vivo knockdown of Crb3 in the testis also induced considerable disorganization of F-actin network, impeding spermatid adhesion at the apical ES, leading to unwanted spermiation and re-distribution of proteins at the basal ES/BTB (18).

Remarks

Collectively, findings summarize above illustrate the polarity protein complexes found in the testis that confer spermatid and Sertoli cell polarity throughout the epithelial cycle exert their regulatory effects through changes in the organization of cytoskeletal network (Figure 2). However, it must be noted that studies performed thus far focus only on the actin-based cytoskeleton, it remains to be investigated in future studies if one or all of these polarity protein complexes also modulate the organization of MT-based cytoskeleton. This is important since the MT-based network is located adjacent to the actin-based cytoskeleton at the ES (31, 56–59), and studies have shown that MTs are playing a crucial role in concert with F-actin to support the transport of spermatids and other organelles (e.g., phagosomes, residual bodies, endocytic vesicles) as well as Sertoli cell and spermatid adhesion (60–63).

Role of the apical ES-BTB-BM functional axis in cell polarity in the testis

Introduction

The sections above have briefly summarized recent findings regarding the role of the three polarity protein complexes in the testis to support spermatid and Sertoli cell polarity, and its likely involvement in cell adhesion, through their regulatory role on the cytoskeletal elements in Sertoli cells. However, recent studies have demonstrated the presence of an elaborate local regulatory axis that functionally connects the apical compartment, the BTB, the basal compartment and the basement membrane of the tunica propria. This axis is important since it supports and coordinates different cellular events across the seminiferous epithelium during the epithelial cycle. For instance, the events of spermiation and remodeling of the BTB to support the release of mature spermatids into the tubule lumen and the transport of preleptotene spermatocytes across the immunological barrier, respectively, take place concurrently in stage VIII but at the opposite ends of the epithelium. Studies summarized below have shown that these events are tightly regulated through biologically active peptide fragments released at the apical ES or basement membrane, which in turn potentiate further breakdown of the apical ES to facilitate spermiation. At the same time, these autocrine-based fragments also promote BTB remodeling. Recent studies have shown that these autocrine-based fragments induce defects in spermatid polarity, supporting the notion that the polarity protein complexes and their partner proteins are involved in this functional axis. Herein, we carefully evaluate these findings to provide some guides for future studies.

The apical ES–BTB/basal ES axis

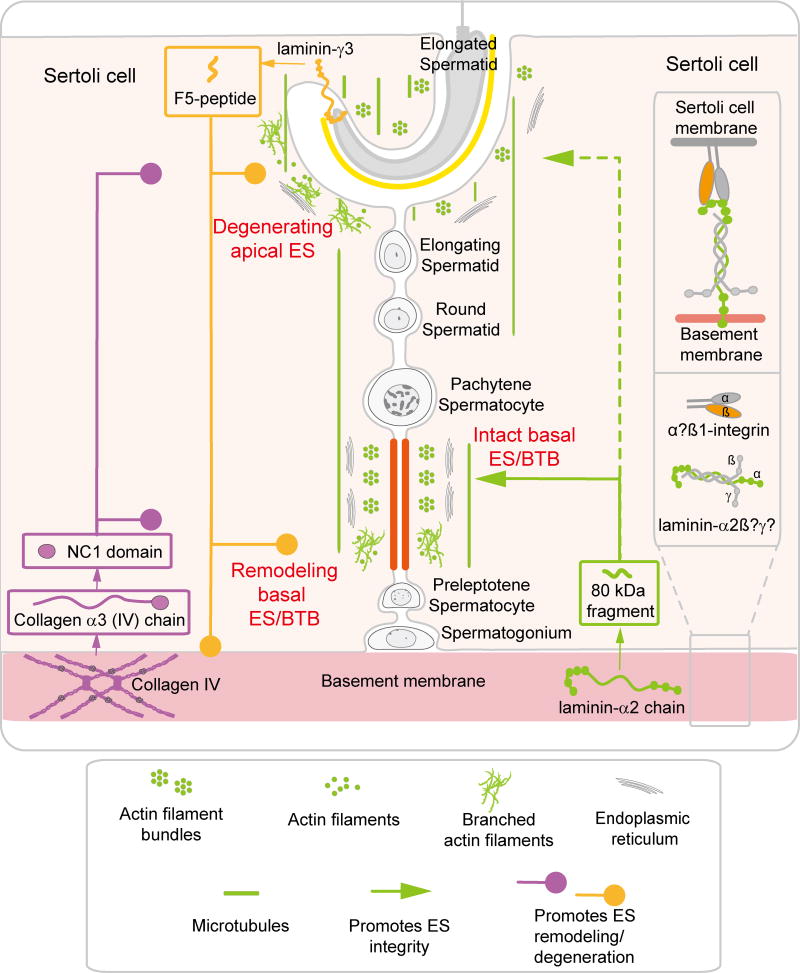

Studies during the last decade have demonstrated the presence of a local functional axis known as the apical ES–basal ES/BTB–basement membrane (BM) that coordinates cellular events across the seminiferous epithelium to support spermatogenesis (64–66) (Figure 3; Table 3). It was first reported that an integrated structural protein at the apical ES – laminin-α3β3γ3 expressed exclusively by elongated spermatids (67) which serves as a ligand and forms a bona fide complex with α6β1-integrin expressed only by Sertoli cells (68–70) – could be cleaved by metalloproteinases (MMPs, such as MMP-2) (68) to generate biologically active fragments to modulate BTB function (71). In short, at stage VIII of the epithelial cycle, at the time of apical ES degeneration to facilitate the release of sperm at spermiation near the tubule lumen, MMP-2 cleaves laminin-γ3 chain to generate biologically active peptides which can induce BTB remodeling near the basement membrane (68, 71). Thus, the cellular events of spermiation and BTB remodeling that take place simultaneously but across the seminiferous epithelium at the opposite ends in order to facilitate the release of sperm and the transport of preleptotene spermatocytes at the barrier, respectively, can be tightly coordinated through this functional axis. Subsequent studies using a phthalate-based toxicant model has demonstrated MMP-2-mediated laminin chain cleavage and that a disruption of the apical ES can induce secondary disruption of the BTB function (72, 73). These findings thus provide compelling evidence to support the presence of this functional axis. Furthermore, study has identified a 50-amino acid peptide fragment from laminin-γ3 chain designated F5-peptide which when over-expressed in Sertoli cells or by including the synthetic 50-amino acid peptide in the Sertoli cells cultured in vitro effectively perturbs Sertoli TJ-permeability barrier function (74, 75). More important, the use of synthetic F5-peptide or through its overexpression using a cDNA construct and a mammalian expression vector pCI-neo, these findings in vitro were reproduced in studies in vivo (74, 75) (Figure 3). Subsequent study has also shown that F5-peptdie is actively transported into Sertoli cells utilizing the drug transporter Slc15a1 (76). Besides inducing BTB remodeling, the release of this F5-peptide also potentiates further breakdown of the apical ES so that this F5-peptide exerts its disruptive effects at the apical ES as well as the basal ES to coordinate apical ES degeneration and basal ES/BTB remodeling at stage VIII of the epithelial cycle (75). Collectively, these findings illustrate that this an autocrine-based local signaling pathway to coordinate cellular events that takes place at the apical ES near the tubule lumen and also near the basement membrane at the BTB. In this context, it is of interest to note that the biologically active laminin-generated peptides were also shown to modulate basement membrane function by down-regulating β1-integrin expression at the basement membrane (71), which is also an integrated component of the basement membrane besides an adhesion protein at the apical ES (69, 71). This latter finding thus supports the notion the apical ES-BTB/basal ES axis is extended to the basement membrane. In this context, it is of interest to note that the presence of this local regulatory function axis has been confirmed in studies using the phthalate-induced Sertoli cell injury model, illustrating a disruption of the apical ES function, such as laminin chains breakdown at the apical ES, would lead to a disruption of the basal ES/BTB function (72, 73, 77). These findings also illustrate that this functional axis is also the target of environmental toxicants, and this axis is also a likely candidate for non-hormonal male contraceptive development (78).

Figure 3. A schematic drawing that illustrates the role of several autocrine peptides: F5-peptide, NC1 domain peptide and 80 kDa fragment, in the apical ES-basal ES/BTB-basement membrane functional axis to support spermatogenesis.

It is noted that F5-peptide derived from the laminin-γ3 chain at the apical ES, NC1 domain peptide from the collagen α3 (IV) chains in the basement membrane, and also the 80 kDa fragment from the laminin-α2 chain in the basement membrane are biologically active autocrine-based peptides in the apical ES-basal ES/BTB-basement membrane functional axis to regulation spermatogenesis. In short, both F5-peptide and NC1 domain peptide induce apical ES degeneration and basal ES remodeling, whereas the 80 kDa fragment derived from the laminin-α2 chain promotes ES integrity. At this writing, the other two laminin chains that constitute the functional ligand with laminin-α2 chain in the basement membrane remain unknown. Also, the identity of the integrin-α chain that form bona fide complex with integrin-β1 chain to serve as the receptor in the basement membrane remains unknown. (see text for details).

Table 3.

Autocrine-based biologically active peptide fragments in the apical ES-basal ES/BTB-basement membrane functional axis in rodent testes*

| Biological active peptide fragment |

Originated Protein |

Original Location |

Target site | Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F5-peptide | Laminin-γ3 chain | Apical ES | Apical ES, BTB, basement membrane | Disrupts F-actin/MT organization, apical ES and spermatid polarity; promotes basal ES/BTB remodeling; down-regulates β1-integrin expression |

| NC1 (non-collagenous 1) domain peptide | Collagen α3 (IV) chain | Basement membrane | Apical ES, BTB | Disrupts F-actin/MT organization; induces apical ES breakdown and defects in spermatid polarity; perturbs basal ES/BTB integrity |

| 80 kDa fragment peptide | Laminin-α2 chain | Basement membrane | BTB | Promotes BTB integrity; maintains F-actin/MT organization |

Abbreviations used: BTB, blood-testis barrier; ES, ectoplasmic specialization; MT, microtubule.

The apical ES–BTB/basal ES–BTB-basement membrane axis

In order to confirm the presence of a functional axis between the apical ES-basal ES/BTB and the basement membrane, β1-integrin in Sertoli cell epithelium in vitro was knocked down by RNAi, which was shown to down-regulate the expression of ZO-1 at the Sertoli cell-cell interface considerably (71), illustrating the Sertoli cell TJ-barrier was disrupted. This finding thus supports the notion regarding the presence of a feedback regulatory loop between the BTB/basal ES and the basement membrane. To further expand this observation, additional studies were performed to examine any functional relationship between basement membrane and the basal ES/BTB (and/or the apical ES). In fact, this possibility is also supported by findings in the literature that biologically active fragments are released from collagen (mostly type IV collagen chains) or laminin chains in the basement membrane (also known as basal lamina) which are capable of modulating angiogenesis, cell survival, cell proliferation, cell differentiation, tissue homeostasis and pathogenesis of diseases in other mammalian tissues and/or organs (79–83). As expected, studies have shown that biologically active fragments released from collagen α3 (IV) chains (a predominant constituent component of the basement membrane in the testis (84)), such as the NC1 (non-collagenous 1) domain peptide from its C-terminal region is a potent peptide that perturbs the Sertoli cell TJ-permeability barrier in vitro (85). More important, this NC1 domain peptide is likely generated through the action of MMP-9 in the basement membrane (86) which is then transported to the adluminal compartment utilizing the MT-based tracks to induce apical ES breakdown, besides exerting its disruptive effects to perturb the Sertoli cell TJ-permeability barrier function (87). Furthermore, this NC1 domain peptide generated at the basement membrane when overexpressed in the testis in vivo was also shown to induce apical ES degeneration, leading to unwanted release of sperm that mimicked spermiation besides perturbing the Sertoli cell BTB integrity (87), consistent with the findings in vitro (87) (Figure 3; Table 3).

The basement membrane provides a crucial regulatory loop in the local apical ES–basal ES/BTB functional axis

As noted above, the F5-peptide derived from the laminin-γ3 chain at the apical ES (71, 74, 75), and the NC1 domain peptide derived from the collagen α3 (IV) chain in the basement membrane (85, 87), both biologically active peptides are known to induce apical ES and basal ES/BTB degeneration/remodeling (Figure 3). Thus, these two peptides potentiate both the release of sperm at spermiation to tubule lumen in the adluminal compartment and BTB remodeling near the basement membrane to support the transport of preleptotene spermatocytes across the immunological barrier. However, two recent papers have demonstrated that an 80 kDa fragment is also generated from laminin-α2 chains in the basement membrane, which, in contrast to the F5-peptide and NC1 domain peptide, has the opposite effects at the apical ES and basal ES/BTB function (88, 89) (Figure 3; Table 3), in sharp contrast to the F5-peptide and NC1 domain peptide. Unlike the F5-peptide and NC1 domain peptide which promote BTB remodeling by making the barrier “leaky”, this 80 kDa laminin-α2 chain fragment promotes Sertoli cell BTB integrity, by tightening the TJ-barrier, making it “tighter” instead (88, 89). This conclusion is reached based on findings that a knockdown of laminin-α2 chain by RNAi was found to perturb the Sertoli cell TJ-permeability barrier (89), illustrating its presence in the testis in vivo is to promote the Sertoli cell BTB function. Taking collectively, these findings also demonstrate the presence of a tightly regulated loop between the basal ES/BTB and the basement membrane in which some locally generated peptides (e.g., F5-peptide, NC1 domain peptide) can perturb whereas others (e.g., 80 kDa laminin-α2 fragment) can promote Sertoli cell BTB function, illustrating there is a network of local regulators having antagonistic effects to support restructuring of cell axis along this apical ES-basal ES/BTB-basement membrane axis. These antagonistic effects of these two types of locally produced regulatory peptides are physiologically necessary since during the transport of preleptotene spermatocytes, the BTB cannot be compromised, even transiently, to avoid the leakage of harmful substances (e.g., environmental toxicants or unwanted hormonal factors) into the adluminal compartment. But this can only be achieved if the “old” BTB located above the preleptotene spermatocytes in transport is “open” only after the “new” BTB situated behind the transporting preleptotene spermatocytes is “close”. In short, these two different autocrine-based biologically active peptides, by working in concert, are providing a unique mechanism to induce BTB restructuring to support spermatocyte transport across the barrier.

Cell polarity and the apical ES-basal ES/BTB-basement membrane functional axis

One would argue that what role does polarity protein is playing in this apical ES–basal ES/BTB–basement membrane functional axis based on the published findings briefly discussed above? First, it was noted that testes treated with recombinant F5-peptide to perturb apical ES and basal ES/BTB function that led to spermatid exfoliation and BTB disruption, respectively, were associated with extensive defects of spermatid polarity in which many elongated spermatids no longer pointed toward the basement membrane but deviated by 90° to 180° from the intended orientation (74). Similar defects in elongated spermatid polarity were also noted when testes were transfected with F5-peptide using a cDNA construct cloned to a mammalian expression vector pCI-neo (75). These defects in elongated spermatid polarity are also noted in testes overexpressed with NC1 domain peptide (87). Taking collectively, these findings illustrate that one of the mechanism(s) by which these biologically active peptides modulate apical ES and basal ES function is mediated through changes in cell polarity. Detailed analysis of the phenotypes in the seminiferous epithelium have shown that the organization of F-actin and also MT was grossly perturbed in testes overexpressed with F5-peptide (75) or treated locally with F5 recombinant protein (74). For instance, the track-like structures prominently conferred by MTs (and also by F-actin) that lay perpendicular to the basement membrane across the seminiferous epithelium are either truncated or extensively mis-aligned. For instance, some MT-based tracks are found to lay in parallel to the basement membrane which are not seen in the seminiferous epithelium of normal testes. Other functional studies have shown that polarity proteins also exerts their regulatory effects through changes in the organization of F-actin and/or MTs. For instance, a knockdown of polarity protein Crb3 leads to a disorganization of F-actin across the Sertoli cell cytosol, failing to support proper localization of cell adhesion protein complexes (e.g., CAR/ZO-1, N-cadherin/β-catenin), making the Sertoli cell TJ-permeability “leaky” (18). A careful examination of the cytoskeletal function in these cells have noted that actin microfilaments across the Sertoli cell cytosol are truncated, failing to stretch across the entire Sertoli cell cytosol to support adhesion function at the ES (18). This pattern of disruptive F-actin organization is also noted in the testis in vivo following transfection with specific Crb3 siRNA duplexes, but not in testes transfected with non-target negative control siRNA duplexes (18). For instance, F-actin is grossly truncated and disorganized at the apical and basal ES/BTB, thereby leading to apical and basal ES disruption (18) since the apical (e.g., nectin-afadin, integrin-laminin) and basal ES (e.g., N-cahderin-β-catenin) adhesion protein complexes utilize F-actin for attachment. A disruption of the actin-based cytoskeletons then renders a compromise of these ES adhesion protein complex functionality, perturbing spermatid adhesion and also inter-Sertoli cell basal ES/BTB function. On the other hand, a triple knockdown of the Scribble complex including Scribble and its two partner proteins Dlg1 and Lgl2 in Sertoli cells cultured in vitro are known to promote the Sertoli cell TJ-permeability barrier function by making the TJ-barrier “tighter” (17). This is mediated through a re-organization of actin microfilaments across the Sertoli cells so that actin filaments are re-aligned considerably at the cell cortical zone, thereby tightening up the TJ-permeability barrier (17). When the F-actin organization in the seminiferous epithelium is assessed following the Scribble/Dlg1/Lgl2 triple knockdown in the testis in vivo, this triple knockdown in the testis indeed promotes BTB integrity in which F-actin remains robustly expressed at the basal ES (17). This thus recruits occludin to the basal ES/BTB site in the seminiferous epithelium and occludin remains robustly expressed even in late stage VIII tubules (17) when it should have been considerably subsided to facilitate the transport of preleptotene spermatocytes across the immunological barrier in late stage VIII tubules (52).

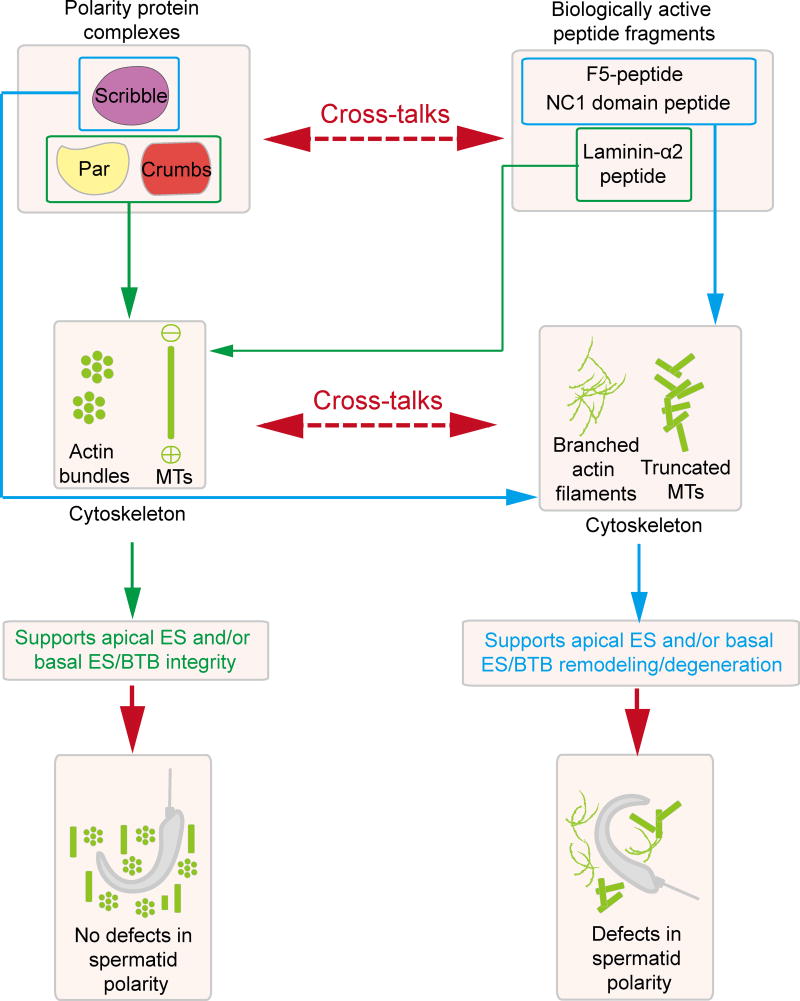

In short, these findings collectively thus illustrate that polarity proteins such as Crb3 and Scribble that are known to be mutually exclusive to each other functionally in multiple epithelia (55) are also functionally similar in the testis. For instance, Crb3 promotes Sertoli cell BTB function by making the Sertoli cell TJ-permeability “tighter” and Scribble promotes BTB disruption by making the barrier “leaker” which is why the knockdown of Crb3 vs. the knockdown of Scribble/Dlg1/Lgl2 perturb Sertoli cell TJ function or promotes TJ-permeability barrier, respectively (17, 18). More important, these changes are modulated through corresponding organization of F-actin in Sertoli cells. These findings also support the emerging concept that in the testis, polarity proteins exert their regulatory effects through the underlying F-actin cytoskeletal function through re-organization of actin microfilaments at the ES by maintaining spermatid polarity. Furthermore, the local regulatory axis also coordinates cellular events that take place across the seminiferous epithelium (e.g., sperm release at spermiation and BTB remodeling at the apical ES vs. basal ES/BTB at stage VIII of the epithelial cycle) through the release of regulatory peptides such as F5-peptide, NC1 domain peptide, and 80 kDa fragment from corresponding laminin-γ3 chain, collagen α3 (IV) chain or laminin-α2 chain, that exert their effects though changes in the organization of the underlying actin- or MT-based cytoskeletons. It is tempting to speculate that these biologically active peptide may exert their regulatory effects on cytoskeletal functions through an involvement of polarity proteins since spermatid polarity in the seminiferous epithelium is grossly perturbed with the functional axis in the epithelium is compromised by manipulating the homeostatic levels of either F5-peptide, NC1 domain peptide or the laminin-α2 level. We thus summarize these findings as depicted in Figure 4, which serves a working model for designing functional experiments to assess the involvement of polarity proteins and cytoskeletons in regulating cellular events across the seminiferous epithelium through the local regulatory axis of apical ES-basal ES/BTB-basement membrane.

Figure 4. A schematic drawing that illustrates the likely biological interactions between the three polarity protein complexes and the autocrine-based peptides in the apical ES-basal ES/BTB-basement membrane to support spermatogenesis in particular spermatid polarity.

Concluding remarks and future perspectives

Herein, we provide a hypothetical model regarding the role of the three polarity protein complexes in regulating spermatogenesis (Figure 4). We also provide a working model regarding the role of the three polarity complex modules in the apical ES-basal ES/BTB-basement membrane functional axis, in particular how these polarity proteins are involved in modulating the organization of cytoskeletal networks in Sertoli cells to support various cellular events during the epithelial cycle of spermatogenesis (Figure 3). There are several pressing questions need to be addressed in future studies. For instance, what is the clue(s) that triggers the production of biologically active fragments generated at the apical ES, the basal ES or the basement membrane? Does this involve cytokines and steroids (e.g., testosterone) which are known to modulate cell junction dynamics in the testis? It is likely that protein kinases, such as c-Src, c-Yes, mTORC1 and mTORC2, are involved in these events, but regulatory signals that trigger an activation of these non-receptor protein kinases remain unknown.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (NICHD R01 HD056034 to C.Y.C.; U54 HD029990 Project 5 to C.Y.C.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest: Nothing to declare

References

- 1.de Kretser DM, Kerr JB. The cytology of the testis. In: Knobil E, Neill JB, Ewing LL, Greenwald GS, Markert CL, Pfaff DW, editors. The Physiology of Reproduction. Vol. 1. Raven Press; New York: 1988. pp. 837–932. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheng CY, Mruk DD. Sertoli Cell Biology. 2. Griswold, M.D.: Amsterdam, Elsevier; 2015. Biochemistry of Sertoli cell/germ cell junctions, germ cell transport, and spermiation in the seminiferous epithelium; pp. 333–383. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hermo L, Pelletier RM, Cyr DG, Smith CE. Surfing the wave, cycle, life history, and genes/proteins expressed by testicular germ cells. Part 1: background to spermatogenesis, spermatogonia, and spermatocytes. Microsc Res Tech. 2010;73:241–278. doi: 10.1002/jemt.20783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clermont Y, Morales C, Hermo L. Endocytic activities of Sertoli cells in the rat. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1987;513:1–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1987.tb24994.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gao Y, Cheng CY. Does cell polarity matter during spermatogenesis? Spermatogenesis. 2016;6:e1218408. doi: 10.1080/21565562.2016.1218408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sharpe RM, McKinnell C, Kivlin C, Fisher JS. Proliferation and functional maturation of Sertoli cells, and their relevance to disorders of testis function in adulthood. Reproduction. 2003;125:769–784. doi: 10.1530/rep.0.1250769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson L, Petty CS, Neaves WB. A comparative study of daily sperm production and testicular composition in humans and rats. Biol Reprod. 1980;22:1233–1243. doi: 10.1093/biolreprod/22.5.1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson L, Petty CS, Neaves WB. Further quantification of human spermatogenesis: germ cell loss during postprophase of meiosis and its relationship to daily sperm production. Biol Reprod. 1983;29:207–215. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod29.1.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson L, Zane RS, Petty CS, Neaves WB. Quantification of the human Sertoli cell population: its distribution, relation to germ cell numbers, and age-related decline. Biol Reprod. 1984;31:785–795. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod31.4.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cearns MD, Escuin S, Alexandre P, Greene ND, Copp AJ. Microtubules, polarity and vertebrate neural tube morphogenesis. J Anat. 2016;229:63–74. doi: 10.1111/joa.12468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elkouby YM. All in one- integrating cell polarity, meiosis, mitosis and mechanical forces in early oocyte differentiation in vertebrates. Int J Dev Biol. 2017;61:179–193. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.170030ye. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wong EWP, Cheng CY. Polarity proteins and cell-cell interactions in the testis. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2009;278:309–353. doi: 10.1016/S1937-6448(09)78007-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huebner RJ, Ewald AJ. Cellular foundations of mammary tubulogenesis. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2014;31:124–131. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2014.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Campanale JP, Sun TY, Montell DJ. Development and dynamics of cell polarity at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2017;130:1201–1207. doi: 10.1242/jcs.188599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ramanujam R, Low TYF, Lim YW, Motegi F. Forceful patterning in mouse preimplantation embryos. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2017.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wong EWP, Mruk DD, Lee WM, Cheng CY. Par3/Par6 polarity complex coordinates apical ectoplasmic specialization and blood-testis barrier restructuring during spermatogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:9657–9662. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801527105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Su WH, Wong EWP, Mruk DD, Cheng CY. The Scribble/Lgl/Dlg polarity protein complex is a regulator of blood-testis barrier dynamics and spermatid polarity during spermatogenesis. Endocrinology. 2012;153:6041–6053. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-1670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gao Y, Lui WY, Lee WM, Cheng CY. Polarity protein Crumbs homolog-3 (CRB3) regulates ectoplasmic specialization dynamics through its action on F-actin organization in Sertoli cells. Scientific reports. 2016;6:28589. doi: 10.1038/srep28589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cheng CY. Toxicants target cell junctions in the testis - insights from the indazole-carboxylic acid model. Spermatogenesis. 2014;4:e981485. doi: 10.4161/21565562.2014.9814895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mruk DD, Silvestrini B, Cheng CY. Anchoring junctions as drug targets: Role in contraceptive development. Pharmacol Rev. 2008;60:146–180. doi: 10.1124/pr.107.07105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu J, Akhmanova A. Microtubule-organizing centers. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2017;33:4.1–4.25. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbiol-100616-060615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kreitzer G, Myat MM. Microtubule motors in establishment of epithelial cell polarity. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology. 2017 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a027896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sackmann E. How actin/myosin crosstalks guide the adhesion, locomotion and polarization of cells. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research. 2015;1853:3132–3142. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2015.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tarulli GA, Meachem SJ, Schlatt S, Stanton PG. Regulation of testicular tight junctions by gonadotrophins in the adult Djungarian hamster in vivo. Reproduction. 2008;135:867–877. doi: 10.1530/REP-07-0572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sobarzo CM, Lustig L, Ponzio R, Denduchis B. Effect of di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate on N-cadherin and catenin protein expression in rat testis. Reprod Toxicol. 2006;22:77–86. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ha HK, Park HJ, Park NC. Expression of E-cadherin and alpha-catenin in a varicocele-induced infertility rat model. Asian J Androl. 2011;13:470–475. doi: 10.1038/aja.2010.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wong EWP, Mruk DD, Cheng CY. Biology and regulation of ectoplasmic specialization, an atypical adherens junction type, in the testis. Biochem Biophys Acta. 2008;1778:692–708. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cheng CY, Mruk DD. Cell junction dynamics in the testis: Sertoli-germ cell interactions and male contraceptive development. Physiol Rev. 2002;82:825–874. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00009.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnson K, Boekelheide K. Dynamic testicular adhesion junctions are immunologically unique. II. Localization of classic cadherins in rat testis. Biol Reprod. 2002;66:992–1000. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod66.4.992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee NPY, Mruk DD, Lee WM, Cheng CY. Is the cadherin/catenin complex a functional unit of cell-cell-actin-based adherens junctions (AJ) in the rat testis? Biol Reprod. 2003;68:489–508. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.102.005793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vogl AW, Vaid KS, Guttman JA. The Sertoli cell cytoskeleton. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2008;636:186–211. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-09597-4_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vogl A, Pfeiffer D, Mulholland D, Kimel G, Guttman J. Unique and multifunctional adhesion junctions in the testis: ectoplasmic specializations. Arch Histol Cytol. 2000;63:1–15. doi: 10.1679/aohc.63.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Russell LD, Peterson RN. Sertoli cell junctions: morphological and functional correlates. Int Rev Cytol. 1985;94:177–211. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)60397-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cheng CY, Mruk DD. The blood-testis barrier and its implication in male contraception. Pharmacol Rev. 2012;64:16–64. doi: 10.1124/pr.110.002790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pelletier RM. The blood-testis barrier: the junctional permeability, the proteins and the lipids. Prog Histochem Cytochem. 2011;46:49–127. doi: 10.1016/j.proghi.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Franca LR, Auharek SA, Hess RA, Dufour JM, Hinton BT. Blood-tissue barriers: Morphofunctional and immunological aspects of the blood-testis and blood-epididymal barriers. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2012;763:237–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaur G, Thompson LA, Dufour JM. Sertoli cells - immunological sentinels of spermatogenesis. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2014;30:36–44. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2014.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wolski KM, Perrault C, Tran-Son-Tay R, Cameron DF. Strength measurement of the Sertoli-spermatid junctional complex. J Androl. 2005;26:354–359. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.04142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Green KJ, Getsios S, Troyanovsky S, Godsel LM. Intercellular junction assembly, dynamics, and homeostasis. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2:a000125. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Green KJ, Simpson CL. Desmosomes: New perspectives on a classic. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:2499–2515. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5701015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wolski KM, Mruk DD, Cameron DF. The Sertoli-spermatid junctional complex adhesion strength is affected in vitro by adjudin. J Androl. 2006;27:790–794. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.106.000422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wu Y, Griffin EE. Regulation of cell polarity by PAR-1/MARK kinase. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2017;123:365–397. doi: 10.1016/bs.ctdb.2016.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sasaki H. Roles and regulations of Hippo signaling during preimplantation mouse development. Dev Growth Differ. 2017;59:12–20. doi: 10.1111/dgd.12335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Assemat E, Bazellieres E, Pallesi-Pocachard E, Le Bivic A, Massey-Harroche D. Polarity complex proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1778:614–630. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ozaki-Kuroda K, Nakanishi H, Ohta H, Tanaka H, Kurihara H, Mueller S, Irie K, Ikeda W, Sakai T, Wimmer E, Nishimune Y, Takai Y. Nectin couples cell-cell adhesion and the actin scaffold at heterotypic testicular junctions. Curr Biol. 2002;12:1145–1150. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00922-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Inagaki M, Irie K, Ishizaki H, Tanaka-Okamoto M, Miyoshi J, Takai Y. Role of cell adhesion molecule nectin-3 in spermatid development. Genes Cells. 2006;11:1125–1132. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2006.01006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cyr D, Hermo L, Egenberger N, Mertineit C, Transler J, Laird D. Cellular immunolocalization of occludin during embryonic and postnatal development of the mouse testis and epididymis. Endocrinology. 1999;140:3815–3825. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.8.6903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Elsum I, Yates L, Humbert PO, Richardson HE. The Scribble-Dlg-Lgl polarity module in development and cancer: from flies to man. Essays Biochem. 2012;53:141–168. doi: 10.1042/bse0530141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Worzfeld T, Schwaninger M. Apicobasal polarity of brain endothelial cells. Journal of cerebral blood flow and metabolism : official journal of the International Society of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 2016;36:340–362. doi: 10.1177/0271678X15608644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Halaoui R, McCaffrey L. Rewiring cell polarity signaling in cancer. Oncogene. 2015;34:939–950. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xiao X, Mruk DD, Wong CKC, Cheng CY. Germ cell transport across the seminiferous epithelium during spermatogenesis. Physiology. 2014;29:286–298. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00001.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li MWM, Xia W, Mruk DD, Wang CQF, Yan HHY, Siu MKY, Lui WY, Lee WM, Cheng CY. TNFα reversibly disrupts the blood-testis barrier and impairs Sertoli-germ cell adhesion in the seminiferous epithelium of adult rat testes. J Endocrinol. 2006;190:313–329. doi: 10.1677/joe.1.06781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Margolis B. The Crumbs3 polarity protein. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2017 doi: 10.1101/cshperspecta027961. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Medina E, Lemmers C, Lane-Guermonprez L, Le Bivic A. Role of the Crumbs complex in the regulation of junction formation in Drosophila and mammalian epithelial cells. Biol Cell. 2002;94:305–313. doi: 10.1016/s0248-4900(02)00004-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Iden S, Collard JG. Crosstalk between small GTPases and polarity proteins in cell polarization. Nature Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:846–859. doi: 10.1038/nrm2521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tang EI, Mruk DD, Cheng CY. Regulation of microtubule (MT)-based cytoskeleton in the seminiferous epithelium during spermatogenesis. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2016;59:35–45. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2016.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vogl A, Pfeiffer D, Redenbach D, Grove B. Sertoli cell cytoskeleton. In: Russell L, Griswold M, editors. The Sertoli Cell. Cache River Press; Clearwater: 1993. pp. 39–86. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Russell LD, Clermont Y. Anchoring device between Sertoli cells and late spermatids in rat seminiferous tubules. Anat Rec. 1976;185:259–278. doi: 10.1002/ar.1091850302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Russell LD, Malone JP, MacCurdy DS. Effect of the microtubule disrupting agents, colchicine and vinblastine, on seminiferous tubule structure in the rat. Tissue Cell. 1981;13:349–367. doi: 10.1016/0040-8166(81)90010-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tang EI, Lee WM, Cheng CY. Coordination of actin- and microtubule-based cytoskeletons supports transport of spermatids and residual bodies/phagosomes during spermatogenesis in the rat testis. Endocrinology. 2016;157:1644–1659. doi: 10.1210/en.2015-1962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Li N, Mruk DD, Tang EI, Lee WM, Wong CK, Cheng CY. Formin 1 regulates microtubule and F-actin organization to support spermatid transport during spermatogenesis in the rat testis. Endocrinology. 2016;157:2894–2908. doi: 10.1210/en.2016-1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.O'Donnell L, O'Bryan MK. Microtubules and spermatogenesis. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2014;30:45–54. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2014.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.O'Donnell L. Mechanisms of spermiogenesis and spermiation and how they are disturbed. Spermatogenesis. 2014;4:e979623. doi: 10.4161/21565562.2014.979623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cheng CY, Mruk DD. A local autocrine axis in the testes that regulates spermatogenesis. Nature Rev Endocrinol. 2010;6:380–395. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2010.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cheng CY, Mruk DD. An intracellular trafficking pathway in the seminiferous epithelium regulating spermatogenesis: a biochemical and molecular perspective. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2009;44:245–263. doi: 10.1080/10409230903061207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cheng CY, Wong EWP, Yan HHN, Mruk DD. Regulation of spermatogenesis in the microenvironment of the seminiferous epithelium: New insights and advances. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2010;315:49–56. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2009.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yan HHN, Cheng CY. Laminin α3 forms a complex with β3 and γ3 chains that serves as the ligand for α6β1-integrin at the apical ectoplasmic specialization in adult rat testes. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:17286–17303. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513218200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Siu MKY, Cheng CY. Interactions of proteases, protease inhibitors, and the β1 integrin/laminin γ3 protein complex in the regulation of ectoplasmic specialization dynamics in the rat testis. Biol Reprod. 2004;70:945–964. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.103.023606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Palombi F, Salanova M, Tarone G, Farini D, Stefanini M. Distribution of β1 integrin subunit in rat seminiferous epithelium. Biol Reprod. 1992;47:1173–1182. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod47.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Salanova M, Stefanini M, De Curtis I, Palombi F. Integrin receptor α6β1 is localized at specific sites of cell-to-cell contact in rat seminiferous epithelium. Biol Reprod. 1995;52:79–87. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod52.1.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yan HHN, Mruk DD, Wong EWP, Lee WM, Cheng CY. An autocrine axis in the testis that coordinates spermiation and blood-testis barrier restructuring during spermatogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:8950–8955. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711264105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yao PL, Lin YC, Richburg JH. TNFα-mediated disruption of spermatogenesis in response to Sertoli cell injury in rodents is partially regulated by MMP2. Biol Reprod. 2009;80:581–589. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.108.073122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yao PL, Lin YC, Richburg JH. Mono-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate-induced disruption of junctional complexes in the seminiferous epithelium of the rodent testis is mediated by MMP2. Biol Reprod. 2010;82:516–527. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.109.080374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Su L, Mruk DD, Lie PPY, Silvestrini B, Cheng CY. A peptide derived from laminin-γ3 reversibly impairs spermatogenesis in rats. Nat Communs. 2012;3:1185. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2171. (doi:1110.1038/ncomms2171) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gao Y, Mruk DD, Lui WY, Lee WM, Cheng CY. F5-peptide induces aspermatogenesis by disrupting organization of actin- and microtubule-based cytoskeletons in the testis. Oncotarget. 2016;7:64203–64220. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.11887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Su L, Zhang Y, Cheng CY, Lee WM, Ye K, Hu D. Slc15a1 is involved in the transport of synthetic F5-peptide into the seminiferous epithelium in adult rat testes. Scientific reports. 2015;5:16271. doi: 10.1038/srep16271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mazaud-Guittot S. Dissecting the phthalate-induced Sertoli cell injury: the fragile balance of proteases and their inhibitors. Biol Reprod. 2011;85:1091–1093. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.111.095976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wan HT, Mruk DD, Wong CKC, Cheng CY. The apical ES-BTB-BM functional axis is an emerging target for toxicant-induced infertility. Trends Mol Med. 2013;19:396–405. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2013.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Marneros AG, Olsen BR. The role of collagen-derived proteolytic fragments in angiogenesis. Matrix Biol. 2001;20:337–345. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(01)00151-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Digtyar AV, Pozdnyakova NV, Feldman NB, Lutsenko SV, Severin SE. Endostatin: current concepts about its biological role and mechanisms of action. Biochemistry. Biokhimiia. 2007;72:235–246. doi: 10.1134/s0006297907030017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Horejs CM. Basement membrane fragments in the context of the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Eur J Cell Biol. 2016;95:427–440. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2016.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Heinegard D. Proteoglycans and more - from molecules to biology. Int J Exp Pathol. 2009;90:575–586. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2613.2009.00695.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gaggar A, Weathington N. Bioactive extracellular matrix fragments in lung health and disease. J Clin Invest. 2016;126:3176–3184. doi: 10.1172/JCI83147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Siu MKY, Cheng CY. Dynamic cross-talk between cells and the extracellular matrix in the testis. BioEssays. 2004;26:978–992. doi: 10.1002/bies.20099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wong EWP, Cheng CY. NC1 domain of collagen α3(IV) derived from the basement membrane regulates Sertoli cell blood-testis barrier dynamics. Spermatogenesis. 2013;3:e25465. doi: 10.4161/spmg.25465. (PMID:23885308; PMCID:PMC23710226; DOI:23885310.23884161/spmg.23825465) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Siu MKY, Lee WM, Cheng CY. The interplay of collagen IV, tumor necrosis factor-α, gelatinase B (matrix metalloprotease-9), and tissue inhibitor of metalloprotease-1 in the basal lamina regulates Sertoli cell-tight junction dynamics in the rat testis. Endocrinology. 2003;144:371–387. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-220786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Chen H, Mruk DD, Lee WM, Cheng CY. Regulation of spermatogenesis by a local functional axis in the testis: role of the basement membrane-derived noncollagenous 1 domain peptide. FASEB J. 2017 doi: 10.1096/fj.201700052R. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Gao Y, Chen H, Lui WY, Lee WM, Cheng CY. Basement membrane laminin α2 regulation of BTB dynamics via its effects on F-actin and microtubule (MT) cytoskeletons is mediated through mTORC1 signaling. Endocrinology. 2017;158:963–978. doi: 10.1210/en.2016-1630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Gao Y, Mruk D, Chen H, Lui WY, Lee WM, Cheng CY. Regulation of the blood-testis barrier by a local axis in the testis: role of laminin α2 in the basement membrane. FASEB J. 2017;31:584–597. doi: 10.1096/fj.201600870R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]