Significance

The nature of animal management in Mesoamerica is not as well understood compared with other state-level societies around the world. In this study, isotope analysis of animal remains from Ceibal, Guatemala, provides the earliest direct evidence of live animal trade and possible captive animal rearing in the Maya region. Carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen isotopes show that domesticated and possibly even wild animals were raised in or around Ceibal and were deposited in the ceremonial core. Strontium isotope analysis reveals the Maya brought dogs to Ceibal from the distant Guatemalan highlands. The possible ceremonial contexts of these captive-reared and imported taxa suggests animal management played an important role in the symbolic development of political power.

Keywords: Maya archaeology, isotope analysis, zooarchaeology

Abstract

This study uses a multiisotope (carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, and strontium) approach to examine early animal management in the Maya region. An analysis of faunal specimens across almost 2,000 years (1000 BC to AD 950) at the site of Ceibal, Guatemala, reveals the earliest evidence for live-traded dogs and possible captive-reared taxa in the Americas. These animals may have been procured for ceremonial functions based on their location in the monumental site core, suggesting that animal management and trade began in the Maya area to promote special events, activities that were critical in the development of state society. Isotopic evidence for animal captivity at Ceibal reveals that animal management played a greater role in Maya communities than previously believed.

Unlike other regions of the world where intensive animal domestication developed as a means to sustain growing human populations in early urban communities, in Mesoamerica mounting evidence suggests that captive rearing and animal trade were directly linked to displays of political and social strength (1–3). To better understand the origins of animal management in the Maya area, we conducted a multifocal isotopic investigation on the archaeological fauna from Ceibal, Guatemala. Ceibal was an important Maya urban center with a nearly 2,000-y occupational history (1000 BC to AD 950), allowing for a long-term examination of animal-related activities. Ceibal’s Central Plaza and monumental site core were among the earliest in the Maya region (4–6). We demonstrate that animals deposited in construction fills and midden material in and around the Central Plaza contained a mix of local and nonlocal individuals. This study reveals the earliest isotopic evidence of live animal trade in the Americas, coinciding with the Maya Middle Preclassic period (700–350 BC), as well as early evidence of possible captive animal rearing or garden hunting. These activities likely promoted the community’s economic growth and political development. Our results suggest that captive animal rearing and long-distance trade took place in Mesoamerica far earlier than has been believed, and that such activities were integral for the development of ceremonial and political power in the Maya region.

The Site of Ceibal

Ceibal has one of the earliest and longest occupations of any site in the Maya region, due to its strategic location on the Pasión River (Fig. 1; refs. 4–7). Radiocarbon and ceramic dating suggest that the Central Plaza and surrounding platforms were constructed at the beginning of Ceibal’s history (∼1000 BC; Table S1), and were among the first monumental construction efforts in the Maya lowlands. These projects and public ceremonies, possibly sponsored by the emerging elites, likely attracted inhabitants of the surrounding region. Ceibal grew to be the largest community in the southwestern Maya lowlands during the Late and Terminal Preclassic periods (350 BC to AD 175; refs. 7–9). Ceremonial deposits of greenstone axes and obsidian artifacts attest to Ceibal’s trade relations with various areas, including the Gulf Coast and Guatemalan highlands (4, 10, 11). After a significant demographic decline during the Early Classic period (AD 175–600), Ceibal recovered to become a major political power under a dynastic rule during the Late Classic period (AD 600–810). Ceibal’s two-millennia history allows archaeologists the unique opportunity to examine the early use of animals and its long-term trend.

Fig. 1.

Map of the Maya region with strontium and oxygen isotope values. 87Sr/86Sr values from ref. 44, with 2σ range around each regional average. Carbonate δ18O values using human bone apatite and tooth enamel from previously reported studies (refs. 34 and 35 for the lowlands; ref. 36 for the highlands). Reprinted with permission from ref. 5.

Isotope Analysis and Animal Management

Isotope analysis was used in this study to assess whether animals were reared in captivity at Ceibal, and whether any terrestrial mammals were imported to Ceibal from another region. A detailed description of isotope methods used in this study is presented in Isotope Analysis Methods. We sampled 10 taxa (Table 1), with a focus on the mammals most commonly found at the site, dogs and deer (Canis lupus familiaris and Odocoileus virginianus), to assess how the Ceibal inhabitants used different species. Specimens were selected from multiple locations around the central site core (group A; Fig. S1), from the outlying residential groups, and from a satellite community, Caobal (12, 13). Specimens were selected from multiple time periods to gauge changes over time.

Table 1.

Summary mean statistics to 1 SD by taxon for bone and tooth enamel sampled for all time periods

| Bone | Tooth enamel | ||||||

| Taxon | δ15Nco (‰, vs. AIR) | δ13Cco (‰, vs. PDB) | δ13Cap (‰, vs. PDB) | 87Sr/86Sr | δ13Cen (‰, vs. PDB) | δ18Oen (‰, vs. PDB) | 87Sr/86Sr |

| Domestic dog | 9.2 ± 1.4 (10) | −11.5 ± 2.4 (10) | −7.9 ± 1.1 (9) | 0.70737 ± 0.0003 (4) | −5.5 ± 2.6 (22) | −3.7 ± 1.0 (22) | 0.70742 ± 0.00053 (23) |

| White-tailed deer | 4.9 ± 1.6 (21) | −21.3 ± 1.1 (21) | −10.9 ± 1.6 (22) | 0.70761 ± 0.0001 (9) | −13.5 ± 0.6 (3) | −2.0 ± 0.7 (3) | 0.70758 ± 0.00012 (3) |

| Peccary | 4.6 ± 0.9 (6) | −19.7 ± 2.8 (6) | −10.5 ± 1.7 (6) | −6.7 (1) | −3.6 (1) | 0.70745 (1) | |

| Large feline | 9.1 ± 1.9 (2) | −17.4 ± 3.0 (2) | −10.6 ± 2.7 (2) | 0.70752 (1) | −8.4 (1) | −3.4 (1) | 0.70753 ± 0.00002 (2) |

| Margay | −15.1 (1) | −2.9 (1) | 0.70749 (1) | ||||

| Tapir | −15.2 ± 1.7 (2) | −6.1 ± 2.3 (2) | 0.707432 ± 0.00008 (2) | ||||

| Lowland paca | 4.6 (1) | −21.0 (1) | −11.1 (1) | −2.9 (1) | |||

| Opossum | −13.5 (1) | −2.1 (1) | 0.70750 (1) | ||||

| Northern turkey | 7.6 ± 1.8 (2) | −8.9 ± 1.1 (2) | −5.2 ± 0.1 (2) | 0.70747 ± 0.00001 (2) | |||

| Ocellated turkey | 8.6 (1) | −17.8 (1) | −9.1 (1) | ||||

| Unidentified turkey | 5.3 ± 0.2 (2) | −18.4 ± 6.1 (2) | −8.9 ± 3.6 (2) | ||||

Parentheses indicate number of individuals sampled. See Dataset S2 for all data.

Stable carbon (δ13C) and nitrogen (δ15N) isotopes from bone collagen can assess whether animals were fed maize-based diets, the primary grain in Mesoamerica, while held in captivity (14, 15). The δ13C values in terrestrial animals vary depending on the proportion of plants they consume that undergo either C3 or C4 photosynthesis. C3 plants have δ13C values that average −26‰, whereas C4 plants, such as maize (Zea mays) and arid-adapted tropical grasses, average −12‰ (16–18). At Ceibal, high δ13C values would be expected from animals consuming predominantly maize, or animals consuming maize-eating prey, since there are relatively few other elevated δ13C sources. δ13C in bone apatite and tooth enamel apatite (δ13Cap and δ13Cen) reflects the total diet, whereas δ13C from collagen (δ13Cco) comes from protein. Due to this fractionation, δ13Cap and δ13Cen values are often shifted toward more positive values compared with collagen. δ15N values in bone collagen reflect the amount of protein in an animal’s diet (19), which may show whether carnivores or omnivores like dogs were given different diets intentionally by their human owners (for example, hunting dogs as opposed to dogs reared for human consumption).

Previous studies of animal diet in Mesoamerica have focused on the Classic and Postclassic periods (AD 200 and later), since there have been more sites excavated from these later periods. Dogs and turkeys have been the focus of many of these investigations since they were domesticated. Isotope studies found evidence that some dogs consumed high quantities of maize (15, 20), corroborating Spanish accounts and Classic period art that depict dogs fattened for human consumption and ritual sacrifice (21–23); however, this has not been consistently demonstrated at every center (24). Evidence of maize-fed turkeys has proven to be more complex and is dependent on whether the turkey is of the northern (Meleagris gallopavo, also known as the “wild” and “domesticated” turkey) or ocellated (Meleagris ocellata) species, as well as the chronological period and region, likely due to the long and complex history of turkey domestication (3, 25, 26). Similarly, while recent isotope studies at the large Classic period city of Teotihuacan in Central Mexico have found evidence of captive-reared rabbits (14) and even ceremonially killed felines, wolves, and eagles (2), comparable evidence has been absent in the Maya area, as well as from the Preclassic record across Mesoamerica in general.

Strontium (87Sr/86Sr) and oxygen (δ18O) isotopes were used in this study to assess whether terrestrial animals were imported to Ceibal from distant locations. Strontium isotope ratios in animal bones and teeth reflect the 87Sr/86Sr value of the local geology in a region (Fig. 1 and Dataset S1; refs. 27 and 28). Nonlocal animals have 87Sr/86Sr values that differ from the local area. Migration studies in Mesoamerica have focused on human remains (29), although a handful have assessed the movement of animals across the landscape as well (30, 31). Thornton (31) found evidence of occasional nonlocal deer and peccaries at Maya sites in Guatemala and Belize, indicating that such animals were exchanged during the Classic and Postclassic periods, perhaps as part of the market economy that existed by that time (32, 33). Before the present study, no investigation had assessed whether animals were moved across the landscape before the Late Classic period.

Oxygen has largely been used in studies of human migration in the Maya area in conjunction with strontium (34–36). Recent studies (37) of modern δ18O annual variability in rain and surface water found that some sources, particularly closed sources like ponds, demonstrate significant δ18O variability throughout the year and might complicate sourcing studies that rely on regional oxygen baselines (38). Physiological investigations have also found that δ18O reflects the extent to which an animal obtains water either from terrestrial water sources or from plant material, the type of plant matter an animal consumes (i.e., C3 plants tend to have higher δ18O than C4 plants), and metabolic variation, three factors that must be taken into consideration when interpreting δ18O among several taxa (39–42). Due to the number of variables that may affect δ18O values, the present study only uses δ18O to corroborate the strontium and carbon data.

Results

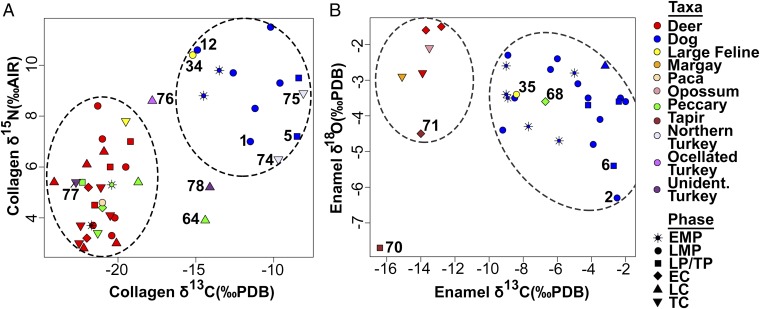

Table 1 lists a statistical summary of the 10 species’ isotope values, expanded in Dataset S2. Regarding collagen, results of the δ13Cco and δ15N analysis of animal diet show that the Ceibal fauna tend to fall into two groups (Fig. 2). One group has lower δ15N (<8.0‰) and δ13Cco (less than −17.0‰), whereas the other has greater values of both isotopes (δ15N ∼ more than 6.0‰, δ13Cco ∼ more than −17.0‰). The former group’s values are expected of animals that consume C3 plant material in the forest (17); the latter group with higher values are expected from animals that eat a partial maize diet or prey that has eaten maize. The group with higher δ15N and δ13Cco values includes the dogs from all periods, the two northern turkeys (M. gallopavo, confirmed by ancient DNA analysis), and one of the two large wild cats (mandible specimen no. 34 and its molar, specimen no. 35), possibly a jaguar (Panthera onca) based on mandibular morphology and size. The ulna of another large feline and the molar of a smaller feline identified as a margay (Leopardus wiedii; specimen nos. 36 and 37), both found behind the Terminal Classic (AD 810–950) palace, had much lower δ13Cco and δ13Cen values, respectively, indicating the two felines from this period consumed the meat of forest-dwelling animals. One turkey that could not be identified to the species level (specimen no. 78) and one peccary (specimen no. 64) have δ13Cco values above −15‰ and δ15N values below 6‰, indicating that they may also have been consuming higher quantities of maize than the cluster of animals with lower carbon isotope values, but also lower quantities of protein than the dogs and northern turkeys. The bone δ13Cap values corroborate this division (Fig. S2), with one Middle Preclassic dog (specimen no. 12) exhibiting lower carbon isotope values than the others (δ13Cap = −10.3‰) and overlapping with the deer that appear to be consuming a mainly C3 forest diet.

Fig. 2.

Ceibal fauna (A) bone collagen and (B) tooth enamel. Specimens mentioned in the text are numbered. The two encircled regions on both graphs denote greater reliance on C3 (Left) and C4 (Right) plants. EC, Early Classic (AD 175–600); EMP, Early Middle Preclassic (1000–700 BC); LC, Late Classic (AD 600–810); LMP, Late Middle Preclassic (700–350 BC); LP/TP, Late Preclassic/Terminal Preclassic (350 BC to AD 175); TC, Terminal Classic (AD 810–950).

Carbon isotope results from tooth enamel apatite also reflect the division between animals consuming a mainly C3 plant diet and a C4 grass (likely maize) diet (Fig. 2). One peccary tooth from the Early Classic period (specimen no. 68, AD 400–500) had elevated δ13Cen (−6.7‰), indicating that it also may have been consuming C4 plants when the enamel formed while it was young. The enamel and bone apatite and collagen was tested from the mandibular and maxillary bone and associated teeth from seven of the dogs (dogs A through G on Dataset S2), and the large feline with the elevated δ13C, to determine whether these animals had consumed similar diets from a young age (the enamel δ13C) to adulthood (bone apatite and collagen δ13C). The elevated carbon ratio was found in both the bone and enamel of the adult feline (specimen nos. 34 and 35, δ13Cco = −15.2‰, δ13Cap = −8.7‰, and δ13Cen = −8.4‰), implying that it had consumed the same elevated δ13C diet since it was a cub and so may have been raised in captivity. Collagen from this feline’s mandible bone and molar roots were radiocarbon dated to the end of the Middle Preclassic period (450–350 BC; Table S2).

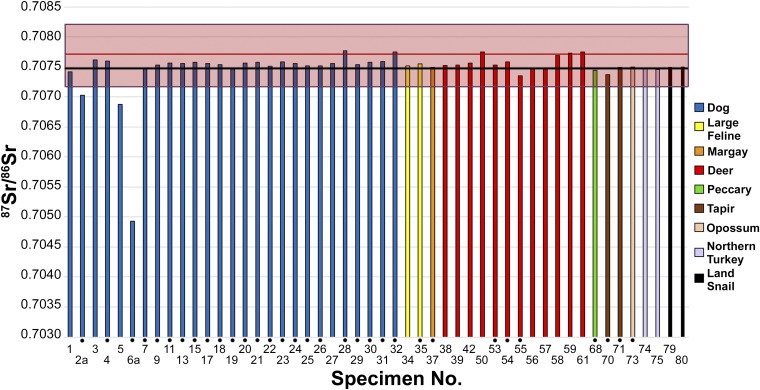

The 87Sr/86Sr and δ18O data show compatible evidence that terrestrial fauna were imported to Ceibal, although only during the Preclassic period. The local 87Sr/86Sr baseline value for Ceibal is 0.70749 (Dataset S1). 87Sr/86Sr results of the archaeological fauna show that 44 of the 46 animals tested fall within the local Ceibal and southern lowlands range (Fig. 3 and Fig. S3). Local δ18O values for the southern lowlands vary between −4.5 and −1‰ (Fig. 1), which also appears to be the case for all but three of the animals. Two Preclassic dogs (specimen nos. 1–2 and 5–6, hereafter dog A and dog C) and one Preclassic tapir (Tapirella bairdii, specimen no. 70) may have come far from Ceibal based on their anomalous 87Sr/86Sr and δ18O values, and likely even outside the Maya lowlands in the case of the dogs. These two dogs’ enamel 87Sr/86Sr and δ18O values were outliers, but their bone apatite values were closer to the lowland range, falling within the local range for dog A (enamel 87Sr/86Sr = 0.70703; bone apatite 87Sr/86Sr = 0.70742) and just below the local range for dog C (enamel 87Sr/86Sr = 0.70493; bone apatite 87Sr/86Sr = 0.70688). This indicates that they moved from elsewhere while alive and lived in or near Ceibal long enough to obtain the local isotope signatures, although there is also a possibility that postmortem diagenetic contamination from the soil made the bone apatite appear more “local” than it actually was. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) of the bones may be able to determine the extent of this diagenesis, but it was not performed in this study (Isotope Analysis Methods). The collagen of dogs A and C was radiocarbon dated, with dog A dating to the end of the Middle Preclassic period (450–350 BC), and dog C dating to the Late Preclassic period (350–300 BC). The tapir enamel had low 87Sr/86Sr for the lowland region (0.70737), although still within the local range, but its δ18Oen value (−7.7‰) was much lower than any of the other animals tested in the study and suggests it either came from another region or was drinking from a significantly different water source than the other animals.

Fig. 3.

87Sr/86Sr for Ceibal fauna, labeled by specimen number (Dataset S2). Black dots below the bars denote enamel samples as opposed to bone apatite. The 87Sr/86Sr range for the southern lowlands (2σ) is highlighted red. The southern lowlands average, marked by the solid red line, is 0.70770 (44). Ceibal’s local average, marked by the black line, is 0.70749.

Discussion

The Preclassic Period (1000 BC to AD 175).

The Preclassic isotope results provide the earliest direct evidence of live-traded dogs in the Americas, as well as evidence of elevated δ13C in a local feline. The radiocarbon dates indicate that these two dogs and feline were deposited around the same time, between 400 and 300 BC (Fig. S4, Table S2, and Radiocarbon Dates and Ceibal Chronology). Evidence for the movement of dogs across the landscape has not been found isotopically in previous Mesoamerican studies, and while nonlocal dogs were recently identified on some of the Caribbean islands (43), these Caribbean dogs postdate the Ceibal dogs by at least a millennium. The nonlocal dogs and feline with elevated δ13C were recovered from two large Middle Preclassic pyramids around Ceibal’s Central Plaza, which suggests that all three may have been involved with early ceremonial events that took place at the site (Fig. S5). The Late Preclassic tapir tooth from the Central Plaza may have been imported to the site as well. The other analyzed animals were likely hunted in the forest around Ceibal, with the exception of the domestic dogs, which were locally provisioned with maize.

The two nonlocal dogs also had the lowest δ15N values compared with the other canines (Fig. 2), suggesting that they consumed less meat and had a different diet. Using the results of baseline studies currently available (Dataset S1; refs. 29 and 44), it appears that the extreme outlier, dog C (specimen no. 6), has 87Sr/86Sr characteristic of the Guatemalan volcanic highlands. Dog A (specimen no. 2) has a higher 87Sr/86Sr value that more closely reflects the range reported in the foothills of central Guatemala. Since obsidian blades were imported to Ceibal from the highlands via the foothills during the Preclassic period, these dogs may have been exchanged along that trade network, either as gifts or as pets belonging to humans traveling on this route.

Dogs A and C came from two of the older structures in the site’s ceremonial core (A-10 and A-18). Dog A was a partial skeleton scattered throughout the construction fill with other secondary midden materials that also contained the feline with elevated δ13C (Fig. S5). The presence of dog A and the captive feline in the same context suggests that these animals were involved in the ceremonial activities that took place in Ceibal’s Central Plaza as the community became a regional center of political power.

The large feline mandible (specimen nos. 34 and 35) had elevated δ13C values in both its tooth enamel and bone apatite and collagen, signifying that it had a similar diet since it was a cub. It may have obtained these values by consuming the meat of animals that had themselves consumed high quantities of maize, such as dogs or maize field scavengers. One possibility is that this feline was killed in a form of “garden hunting” in an agricultural area (45), but the fact that the feline had an elevated δ13C value throughout its life calls into question whether it had been subsisting mainly on maize crop foragers for so long. The two Terminal Classic felines with low carbon values are further evidence elevated δ13C values are not common in wild cats in this area, although at present there has been no research done to determine what the isotopes are of felines living near modern agricultural plots in lowland Mesoamerica, to use for comparison. At the Classic period city of Teotihuacan, Sugiyama et al. (2) determined that jaguars, pumas, wolves, and eagles that had been buried in elaborate deposits in the Moon and Sun Pyramids had high δ13C values (complete feline skeletons had significantly higher δ13Cco than incomplete skeletons, ranging −12 ± 3.9‰, with three values exceeding −10‰). They posited that these animals were held in captivity for ceremonial functions and were fed the meat of maize-eating animals, including possibly humans, thus contributing to their 13C-enriched diets. Classic period Maya art also shows live spotted feline cubs in captivity, as depicted on several stelae from Xultun (46). It is possible that the feline found in the Middle Preclassic monumental structure at Ceibal was reared for similar ceremonial performances, perhaps under the aegis of one of the members of the developing class of elite as a symbol of political power.

A Late Preclassic tapir molar found in the Central Plaza (specimen no. 70) had a δ18Oen value that fell far below the lowlands’ range. The tapir’s 87Sr/86Sr value (0.70737) is low but within the lowland 2σ range. It may have originally come from an area to the south of Ceibal where strontium ratios are lower (44), although the Chiapas area in Mexico is also a possibility since it has not been extensively tested for baseline 87Sr/86Sr and δ18O values. Previous studies (47) of modern tapir enamel δ18O have found that such low values (∼7–8‰) are often dependent on low regional precipitation, which means the tapir may have come from an area with low rainfall. The second tapir tooth in this study (specimen no. 71), which came from an Early Classic (AD 175–300) outlying residence, had a local lowland δ18Oen value of −4.5‰. The Late Preclassic tapir tooth may have been an adornment that belonged to a visitor to Ceibal, or was imported to the site. Its discovery in the Central Plaza suggests that its deposition may have been related to activities that took place in that area, including ceremonies.

Of the other Preclassic period animals tested in this study, the remaining dogs show consistently elevated δ13C values. Specimen no. 12’s unusual δ13C and δ15N values (Fig. 2) indicate it had a unique low-maize, high-protein diet and may have been a hunting dog. The other taxa have much lower δ13C characteristic of C3 plant consumption or, in the case of the carnivores, meat from animals that consumed C3 plants. These animals were likely hunted from the local forest based on their δ18O and 87Sr/86Sr values (Fig. 3).

The Classic Period (AD 175–950).

The Ceibal inhabitants appear to have continued hunting animals from the forest during the Classic period, with several significant exceptions. Few dog remains were recovered in the Classic period at Ceibal, resulting in only a single dog tooth (specimen no. 28) tested from this time in the site’s history. The isotopic data reveal two instances of maize-reared and possibly domesticated turkeys (M. gallopavo), and two peccaries that were possibly consuming maize as well, all within the monumental site core. This suggests that wild animal rearing, which perhaps began during the Preclassic period, was more taxonomically diverse during the Classic period, and included potentially early domestication of the M. gallopavo species of turkey.

No turkeys have been recovered from the Preclassic contexts at Ceibal, although representatives of both turkey species are present throughout the Classic phases. The northern and ocellated turkey are distinct isotopically. The two northern turkeys had higher δ15N than many of the herbivores (Fig. 2), consistent with their omnivorous diet that includes insects and possibly human feces that are enriched in δ15N (26, 48). They also had higher δ13Cco (more than −10‰) than the majority (39 of 45) of specimens tested in this study, perhaps because much of their diet consisted of maize. These values conform with previous reports of northern turkey values during the Classic and Colonial periods, where δ13Cco tends to exceed −11‰ and δ15N > 6‰ (26). The confirmed ocellated turkey and the two unidentified turkeys have lower δ13C, suggesting they lived in a forested environment or, in the case of specimen no. 78, occasionally browsed on C4 vegetation. Although more work is still needed to distinguish maize-fed from garden-foraging turkeys (16), it is possible the latter bird was hunted from an agricultural field.

The majority of the peccaries tested in this study had δ13C values indicative of C3 plant consumption, likely from the forest. However, two peccaries (specimen nos. 64 and 68) consumed higher quantities of C4 plants than the other individuals. Specimen no. 64 came from the Late Classic (AD 600–700) palace, and, because its carbon signature (δ13Cco = −14.4‰) is not as high as the dogs, may have consumed maize from an agricultural field as a crop forager. Like turkeys, more actualistic data are needed to isotopically distinguish crop foraging peccaries from maize-fed individuals. Specimen no. 68, an incisor from an elite Early Classic (AD 400–500) structure, had a high δ13Cen value (−6.7‰) like that of the dogs at the site (Fig. 2), suggesting it had an elevated C4 diet when it was very young and the tooth enamel originally formed, and so may have been raised in captivity.

The remaining animals of the Classic period, including the 14 deer, the three other peccaries, a tapir, a large feline, a margay, and an opossum (Philander opossum), had very low carbon isotope values and local oxygen and strontium isotope ratios (Table 1 and Dataset S2). This suggests that these animals were locally hunted. The differences in δ15N values exhibited among the deer are possibly due to variations in the N-fixing bacteria in the soil where the deer browse, as well as varying processes of nitrification and denitrification as a result of climatic effects on soil runoff (49). There is no temporal pattern exhibited in the isotope values in the deer remains, suggesting the reliance on locally hunted deer did not change over the centuries.

Conclusions

The presence of nonlocal dogs, an imported tapir tooth, and several possible cases of captive-reared animals in and around the ceremonial core of Ceibal suggests that Maya communities managed and moved animals across the landscape centuries earlier than has been believed. The Preclassic dogs found in the early monumental structures that appear to have been born in or near the Guatemala highlands indicate the original purposes of animal trade may have been to augment ceremonial events as the first state-level communities developed. Increased evidence of potentially maize-fed animals during the Classic period, particularly the northern turkey, a species that was in the process of domestication during that time, suggests animal management practices intensified during the Classic period. It is also possible that some animals like peccaries and turkeys were hunted as crop foragers, but further isotope studies to more clearly distinguish captive-reared and foraging animals are needed. Overall, the complex human–animal interactions identified in this study demonstrate the need for further multiisotope investigations in the Maya area, for it appears that live animal trade and management may have played a significant role in societal development.

Methods

Archaeological faunal specimens used in this study were collected by the Ceibal-Petexbatun Archaeological Project and imported to the United States with permission of the Guatemala Institute of Anthropology and History (Instituto de Antropología e Historia), under permit no. DAJ-DGPCYN/196/2013. Specimens were identified using the Florida Museum of Natural History’s comparative skeletal collections. Cleaning and initial preparation of specimens, including enamel drilling, sample grinding, separation of bone collagen and apatite fractions, and removal of contaminants through chemical washes, was performed in the Bone Chemistry Laboratory of the University of Florida (UF) Department of Anthropology (Isotope Analysis Methods). The isotopes δ13C, δ15N, and δ18O were analyzed with Carlo Erba-Delta V and Finnegan MAT 252 isotope ratio mass spectrometers in the Light Stable Isotope Mass Spectrometer Laboratory at the UF Department of Geological Sciences. Bone apatite and enamel 87Sr/86Sr were extracted through ion chromatography in the class 1000 clean laboratories at the UF Department of Geological Sciences and analyzed with a Nu-Plasma multiple-collector inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer. Radiocarbon dating was performed on bone collagen of specimen nos. 1, 5, and 34 at Beta Analytic. We refined these dates using Bayesian analysis with the OxCal 4.2 program and the IntCal13 calibration curve (Fig. S4 and Table S2).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the archaeologists and excavators of the Ceibal-Petexbatun Archaeological Project who recovered the faunal material used in this study. We also thank Erin Thornton and Camilla Speller for the turkey ancient DNA analysis, and Nicole Cannarozzi and Arianne Boileau for assisting with the radiocarbon sampling of the dog and feline mandibles. We thank Jason Curtis for analyzing the light isotope samples on the mass spectrometers at the Light Stable Isotope Mass Spectrometer Laboratory, Department of Geological Sciences, University of Florida. We also thank the two anonymous reviewers for their most valuable and constructive suggestions. Funding for the export and isotope analysis of the remains was made possible by the National Science Foundation (Doctoral Dissertation Improvement Grant 1433043 to K.F.E. and A.E.S.), and the Sigma Xi Scientific Research Society, the University of Florida Latin American Studies Program Tinker Grant, and the University of Florida Department of Anthropology Charles Fairbanks Award (to A.E.S.). Radiocarbon dating was conducted with funding from the Alphawood Foundation (T.I.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1713880115/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Somerville AD, Nelson BA, Knudson KJ. Isotopic investigation of pre-Hispanic macaw breeding in northwest Mexico. J Anthropol Archaeol. 2010;29:125–135. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sugiyama N, Somerville AD, Schoeninger MJ. Stable isotopes and zooarchaeology at Teotihuacan, Mexico reveal earliest evidence of wild carnivore management in Mesoamerica. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0135635. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0135635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thornton EK, et al. Earliest Mexican turkeys (Meleagris gallopavo) in the Maya region: Implications for pre-Hispanic animal trade and the timing of turkey domestication. PLoS One. 2012;7:e42630. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Inomata T, Triadan D, Aoyama K, Castillo V, Yonenobu H. Early ceremonial constructions at Ceibal, Guatemala, and the origins of lowland Maya civilization. Science. 2013;340:467–471. doi: 10.1126/science.1234493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Inomata T, et al. High-precision radiocarbon dating of political collapse and dynastic origins at the Maya site of Ceibal, Guatemala. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114:1293–1298. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1618022114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Inomata T, et al. Public ritual and interregional interactions: Excavations of the central plaza of group A, Ceibal. Anc Mesoam. 2017;28:203–232. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Inomata T, et al. Development of sedentary communities in the Maya lowlands: Coexisting mobile groups and public ceremonies at Ceibal, Guatemala. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:4268–4273. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1501212112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burham M, MacLellan J. Thinking outside the plaza: Ritual practices in Preclassic Maya residential groups at Ceibal, Guatemala. Antiquity. 2014;88:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Triadan D, et al. Social transformations in a Middle Preclassic community: Elite residential complexes at Ceibal. Anc Mesoam. 2017;28:233–264. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aoyama K, Inomata T, Pinzón F, Palomo JM. Polished greenstone celt caches from Ceibal: The development of Maya public rituals. Antiquity. 2017;91:701–717. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aoyama K, et al. Early Maya ritual practices and craft production: Late Middle Preclassic ritual deposits containing obsidian artifacts at Ceibal, Guatemala. J Field Archaeol. 2017;42:408–422. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Munson J, Inomata T. Temples in the forest: The discovery of an early Maya community at Caobal, Petén, Guatemala. Antiquity. 2011;85:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Munson J, Pinzón F. Building an early Maya community: Archaeological investigations at Caobal, Guatemala. Anc Mesoam. 2017;28:265–278. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Somerville AD, Sugiyama N, Manzanilla LR, Schoeninger MJ. Animal management at the ancient metropolis of Teotihuacan, Mexico: Stable isotope analysis of Leporid (cottontail and jackrabbit) bone mineral. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0159982. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0159982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.White CD, Pohl MD, Schwarcz HP, Longstaffe FJ. Isotopic evidence for Maya patterns of deer and dog use at Preclassic Colha. J Archaeol Sci. 2001;28:89–107. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bender MM. Mass spectrometric studies of carbon 13 variations in corn and other grasses. Radiocarbon. 1968;10:468–472. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kohn MJ. Carbon isotope compositions of terrestrial C3 plants as indicators of (paleo)ecology and (paleo)climate. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:19691–19695. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004933107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vogel JC. Variability of carbon isotope fractionation during photosynthesis. In: Ehleringer JR, Hall AE, Farquhar GD, editors. Stable Isotopes and Plant Carbon/Water Relations. Academic; San Diego: 1993. pp. 29–46. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schoeninger MJ, DeNiro MJ. Nitrogen and carbon isotopic composition of bone collagen from marine and terrestrial animals. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 1984;48:625–639. [Google Scholar]

- 20.White CD, Pohl MD, Schwarcz HP, Longstaffe FJ. Feast, field and forest: Deer and dog diets at Lagartero, Tikal, and Copan. In: Emery KF, editor. Maya Zooarchaeology: New Directions in Method and Theory. UCLA Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press; Los Angeles: 2004. pp. 141–158. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clutton-Brock J, Hammond N. Hot dogs: Comestible canids in Preclassic Maya culture at Cuello, Belize. J Archaeol Sci. 1994;21:819–826. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hernández F. Quatros Libros de la Naturaleza y Virtudes Medicinales de las Plantas y Animales de la Nueva España. Escuela de Artes; Morelia, Mexico: 1888. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Landa FD. Papers of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology 18. Harvard Univ Press; Cambridge, MA: 1941. Landa’s Relación de las Cosas de Yucatán. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van der Merwe NJ, Tykot RH, Hammond N, Oakberg K. Diet and animal husbandry of the Preclassic Maya at Cuello Belize: Isotopic and zooarchaeological evidence. In: Katzenberg MA, Ambrose SH, editors. Biogeochemical Approaches to Paleodietary Analysis. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; New York: 2000. pp. 23–38. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thornton EK, Emery KF. The uncertain origins of Mesoamerican turkey domestication. J Archaeol Method Theory. 2017;24:1–24. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thornton E, Emery KF, Speller C. Ancient Maya turkey husbandry: Testing theories through stable isotope analysis. J Archaeol Sci Rep. 2016;10:584–595. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bentley RA. Strontium isotopes from the earth to the archaeological skeleton: A review. J Archaeol Method Theory. 2006;13:135–187. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Graustein WC. 87Sr/86Sr ratios measure the sources and flow of strontium in terrestrial ecosystems. In: Rundel PW, Ehlerginger JR, Nagy KA, editors. Stable Isotopes in Ecological Research. Springer; New York: 1989. pp. 491–512. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Price TD, et al. Strontium isotopes and the study of human mobility in ancient Mesoamerica. Lat Am Antiq. 2008;19:167–180. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Freiwald C, Pugh T. The origins of early Colonial cows at San Bernabé, Guatemala: Strontium isotope values at an early Spanish mission in the Petén lakes region of northern Guatemala. Environ Archaeol. 2018;23:80–96. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thornton EK. Reconstructing ancient Maya animal trade through strontium isotope (87Sr/86Sr) analysis. J Archaeol Sci. 2011;38:3254–3263. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dahlin BH, Bair D, Beach T, Moriarty M, Terry R. The dirt on food: Ancient feasts and markets among the Lowland Maya. In: Staller JE, Carrasco MD, editors. Pre-Columbian Foodways: Interdisciplinary Approaches to Food, Culture, and Markets in Ancient Mesoamerica. Springer; New York: 2009. pp. 191–232. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Masson MA, Freidel DA. An argument for Classic era Maya market exchange. J Anthropol Archaeol. 2012;31:455–484. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Price TD, et al. Kings and commoners at Copan: Isotopic evidence for origins and movement in the Classic Maya period. J Anthropol Archaeol. 2010;29:15–32. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wright LE. Immigration to Tikal, Guatemala: Evidence from stable strontium and oxygen isotopes. J Anthropol Archaeol. 2012;31:334–352. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wright LE, Valdes JA, Burton JH, Price TD, Schwarcz HP. The children of Kaminaljuyu: Isotopic insight into diet and long distance interaction in Mesoamerica. J Anthropol Archaeol. 2010;29:155–178. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Scherer AK, Carteret A, Newman S. Local water resource variability and oxygen isotopic reconstructions of mobility: A case study from the Maya area. J Archaeol Sci Rep. 2015;2:666–676. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lachniet MS, Patterson WP. Oxygen isotope values of precipitation and surface waters in northern Central America (Belize and Guatemala) are dominated by temperature and amount effects. Earth Planet Sci Lett. 2009;284:435–446. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kohn MJ. Predicting animal δ18O: Accounting for diet and physiological adaptation. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 1996;60:4811–4829. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Repussard A, Schwarcz HP, Emery KF, Thornton EK. Oxygen isotopes from Maya archaeological deer remains: Experiments in tracing droughts using bones. In: Iannone G, editor. The Great Maya Droughts in Cultural Context: Case Studies in Resilience and Vulnerability. University Press of Colorado; Boulder, CO: 2014. pp. 231–254. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sponheimer M, Lee-Thorp JA. Oxygen isotopes in enamel carbonate and their ecological significance. J Archaeol Sci. 1999;26:723–728. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tuross N, Warinner C, Kirsanow K, Kester C. Organic oxygen and hydrogen isotopes in a porcine controlled dietary study. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2008;22:1741–1745. doi: 10.1002/rcm.3556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Laffoon JE, Plomp E, Davies GR, Hoogland MLP, Hofman CL. The movement and exchange of dogs in the prehistoric Caribbean: An isotopic investigation. Int J Osteoarchaeol. 2015;25:454–465. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hodell DA, Quinn RL, Brenner M, Kamenov G. Spatial variation of strontium isotopes (87Sr/86Sr) in the Maya region: A tool for tracking ancient human migration. J Archaeol Sci. 2004;31:585–601. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Linares O. “Garden hunting” in the American tropics. Hum Ecol. 1976;4:331–349. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Morley SG. 1937. The Inscriptions of the Peten (Carnegie Institution of Washington, Washington, DC), Carnegie Institution of Washington Publication 437.

- 47.DeSantis LG. Stable isotope ecology of extant tapirs from the Americas. Biotropica. 2011;43:746–754. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sutoh M, Koyama T, Yoneyama T. Variations of natural 15N abundances in the tissues and digesta of domestic animals. Radioisotopes. 1987;36:74–77. doi: 10.3769/radioisotopes.36.2_74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hedin LO, Brookshire ENJ, Menge DNL, Barron AR. The nitrogen paradox in tropical forest ecosystems. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst. 2009;40:613–635. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.