Significance

Regional quantification of feasibility and effectiveness of forest strategies to mitigate climate change should integrate observations and mechanistic ecosystem process models with future climate, CO2, disturbances from fire, and management. Here, we demonstrate this approach in a high biomass region, and found that reforestation, afforestation, lengthened harvest cycles on private lands, and restricting harvest on public lands increased net ecosystem carbon balance by 56% by 2100, with the latter two actions contributing the most. Forest sector emissions tracked with our life cycle assessment model decreased by 17%, partially meeting emissions reduction goals. Harvest residue bioenergy use did not reduce short-term emissions. Cobenefits include increased water availability and biodiversity of forest species. Our improved analysis framework can be used in other temperate regions.

Keywords: forests, carbon balance, greenhouse gas emissions, climate mitigation

Abstract

Strategies to mitigate carbon dioxide emissions through forestry activities have been proposed, but ecosystem process-based integration of climate change, enhanced CO2, disturbance from fire, and management actions at regional scales are extremely limited. Here, we examine the relative merits of afforestation, reforestation, management changes, and harvest residue bioenergy use in the Pacific Northwest. This region represents some of the highest carbon density forests in the world, which can store carbon in trees for 800 y or more. Oregon’s net ecosystem carbon balance (NECB) was equivalent to 72% of total emissions in 2011–2015. By 2100, simulations show increased net carbon uptake with little change in wildfires. Reforestation, afforestation, lengthened harvest cycles on private lands, and restricting harvest on public lands increase NECB 56% by 2100, with the latter two actions contributing the most. Resultant cobenefits included water availability and biodiversity, primarily from increased forest area, age, and species diversity. Converting 127,000 ha of irrigated grass crops to native forests could decrease irrigation demand by 233 billion m3⋅y−1. Utilizing harvest residues for bioenergy production instead of leaving them in forests to decompose increased emissions in the short-term (50 y), reducing mitigation effectiveness. Increasing forest carbon on public lands reduced emissions compared with storage in wood products because the residence time is more than twice that of wood products. Hence, temperate forests with high carbon densities and lower vulnerability to mortality have substantial potential for reducing forest sector emissions. Our analysis framework provides a template for assessments in other temperate regions.

Strategies to mitigate carbon dioxide emissions through forestry activities have been proposed, but regional assessments to determine feasibility, timeliness, and effectiveness are limited and rarely account for the interactive effects of future climate, atmospheric CO2 enrichment, nitrogen deposition, disturbance from wildfires, and management actions on forest processes. We examine the net effect of all of these factors and a suite of mitigation strategies at fine resolution (4-km grid). Proven strategies immediately available to mitigate carbon emissions from forest activities include the following: (i) reforestation (growing forests where they recently existed), (ii) afforestation (growing forests where they did not recently exist), (iii) increasing carbon density of existing forests, and (iv) reducing emissions from deforestation and degradation (1). Other proposed strategies include wood bioenergy production (2–4), bioenergy combined with carbon capture and storage (BECCS), and increasing wood product use in buildings. However, examples of commercial-scale BECCS are still scarce, and sustainability of wood sources remains controversial because of forgone ecosystem carbon storage and low environmental cobenefits (5, 6). Carbon stored in buildings generally outlives its usefulness or is replaced within decades (7) rather than the centuries possible in forests, and the factors influencing product substitution have yet to be fully explored (8). Our analysis of mitigation strategies focuses on the first four strategies, as well as bioenergy production, utilizing harvest residues only and without carbon capture and storage.

The appropriateness and effectiveness of mitigation strategies within regions vary depending on the current forest sink, competition with land-use and watershed protection, and environmental conditions affecting forest sustainability and resilience. Few process-based regional studies have quantified strategies that could actually be implemented, are low-risk, and do not depend on developing technologies. Our previous studies focused on regional modeling of the effects of forest thinning on net ecosystem carbon balance (NECB) and net emissions, as well as improving modeled drought sensitivity (9, 10), while this study focuses mainly on strategies to enhance forest carbon.

Our study region is Oregon in the Pacific Northwest, where coastal and montane forests have high biomass and carbon sequestration potential. They represent coastal forests from northern California to southeast Alaska, where trees live 800 y or more and biomass can exceed that of tropical forests (11) (Fig. S1). The semiarid ecoregions consist of woodlands that experience frequent fires (12). Land-use history is a major determinant of forest carbon balance. Harvest was the dominant cause of tree mortality (2003–2012) and accounted for fivefold as much mortality as that from fire and beetles combined (13). Forest land ownership is predominantly public (64%), and 76% of the biomass harvested is on private lands.

Many US states, including Oregon (14), plan to reduce their greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in accordance with the Paris Agreement. We evaluated strategies to address this question: How much carbon can the region’s forests realistically remove from the atmosphere in the future, and which forest carbon strategies can reduce regional emissions by 2025, 2050, and 2100? We propose an integrated approach that combines observations with models and a life cycle assessment (LCA) to evaluate current and future effects of mitigation actions on forest carbon and forest sector emissions in temperate regions (Fig. 1). We estimated the recent carbon budget of Oregon’s forests, and simulated the potential to increase the forest sink and decrease forest sector emissions under current and future climate conditions. We provide recommendations for regional assessments of mitigation strategies.

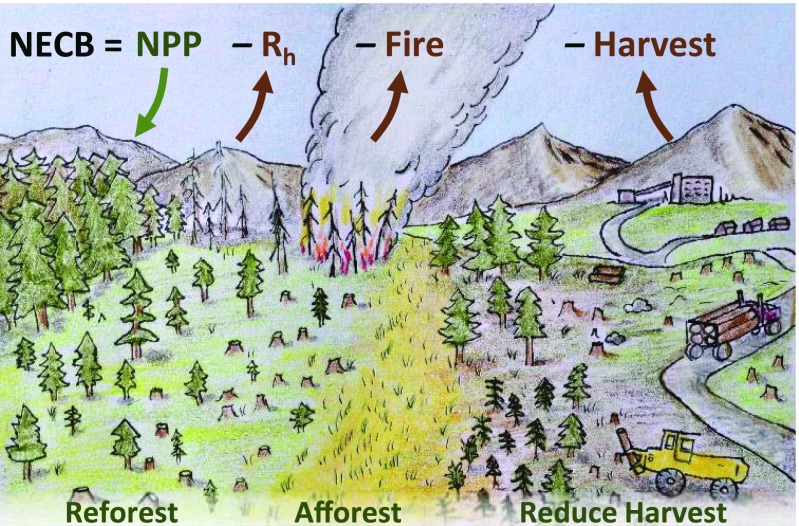

Fig. 1.

Approach to assessing effects of mitigation strategies on forest carbon and forest sector emissions. NECB is productivity (NPP) minus Rh and losses from fire and harvest (red arrows). Harvest emissions include those associated with wood products and bioenergy.

Results

Carbon stocks and fluxes are summarized for the observation cycles of 2001–2005, 2006–2010, and 2011–2015 (Table 1 and Tables S1 and S2). In 2011–2015, state-level forest carbon stocks totaled 3,036 Tg C (3 billion metric tons), with the coastal and montane ecoregions accounting for 57% of the live tree carbon (Tables S1 and S2). Net ecosystem production [NEP; net primary production (NPP) minus heterotrophic respiration (Rh)] averaged 28 teragrams carbon per year (Tg C y−1) over all three periods. Fire emissions were unusually high at 8.69 million metric tons carbon dioxide equivalent (tCO2e y−1, i.e., 2.37 Tg C y−1) in 2001–2005 due to the historic Biscuit Fire, but decreased to 3.56 million tCO2e y−1 (0.97 Tg C y−1) in 2011–2015 (Table S4). Note that 1 million tCO2e equals 3.667 Tg C.

Table 1.

Forest carbon budget components used to compute NECB

| Flux, Tg C⋅y−1 | 2001–2005 | 2006–2010 | 2011–2015 | 2001–2015 | |||

| NPP | 73.64 | 7.59 | 73.57 | 7.58 | 73.57 | 7.58 | 73.60 |

| Rh | 45.67 | 5.11 | 45.38 | 5.07 | 45.19 | 5.05 | 45.41 |

| NEP | 27.97 | 9.15 | 28.19 | 9.12 | 28.39 | 9.11 | 28.18 |

| Harvest removals | 8.58 | 0.60 | 7.77 | 0.54 | 8.61 | 0.6 | 8.32 |

| Fire emissions | 2.37 | 0.27 | 1.79 | 0.2 | 0.97 | 0.11 | 1.71 |

| NECB | 17.02 | 9.17 | 18.63 | 9.14 | 18.81 | 9.13 | 18.15 |

Average annual values for each period, including uncertainty (95% confidence interval) in Tg C y−1 (multiply by 3.667 to get million tCO2e).

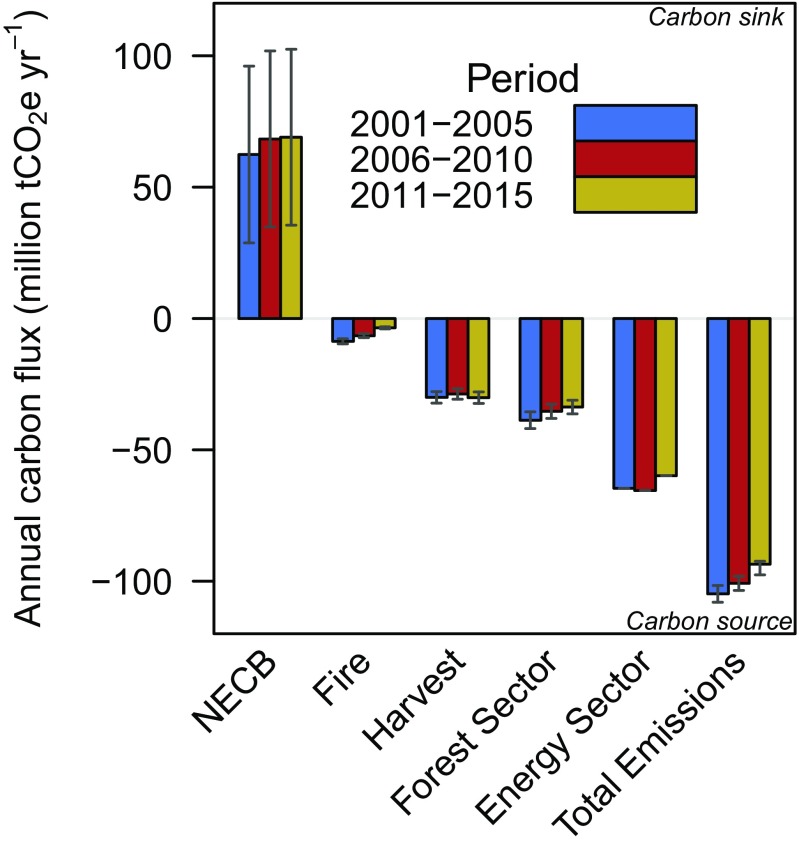

Our LCA showed that in 2001–2005, Oregon’s net wood product emissions were 32.61 million tCO2e (Table S3), and 3.7-fold wildfire emissions in the period that included the record fire year (15) (Fig. 2). In 2011–2015, net wood product emissions were 34.45 million tCO2e and almost 10-fold fire emissions, mostly due to lower fire emissions. The net wood product emissions are higher than fire emissions despite carbon benefits of storage in wood products and substitution for more fossil fuel-intensive products. Hence, combining fire and net wood product emissions, the forest sector emissions averaged 40 million tCO2e y−1 and accounted for about 39% of total emissions across all sectors (Fig. 2 and Table S4). NECB was calculated from NEP minus losses from fire emissions and harvest (Fig. 1). State NECB was equivalent to 60% and 70% of total emissions for 2001–2005 and 2011–2015, respectively (Fig. 2, Table 1, and Table S4). Fire emissions were only between 4% and 8% of total emissions from all sources (2011–2015 and 2001–2004, respectively). Oregon’s forests play a larger role in meeting its GHG targets than US forests have in meeting the nation’s targets (16, 17).

Fig. 2.

Oregon’s forest carbon sink and emissions from forest and energy sectors. Harvest emissions are computed by LCA. Fire and harvest emissions sum to forest sector emissions. Energy sector emissions are from the Oregon Global Warming Commission (14), minus forest-related emissions. Error bars are 95% confidence intervals (Monte Carlo analysis).

Historical disturbance regimes were simulated using stand age and disturbance history from remote sensing products. Comparisons of Community Land Model (CLM4.5) output with Forest Inventory and Analysis (FIA) aboveground tree biomass (>6,000 plots) were within 1 SD of the ecoregion means (Fig. S2). CLM4.5 estimates of cumulative burn area and emissions from 1990 to 2014 were 14% and 25% less than observed, respectively. The discrepancy was mostly due to the model missing an anomalously large fire in 2002 (Fig. S3A). When excluded, modeled versus observed fire emissions were in good agreement (r2 = 0.62; Fig. S3B). A sensitivity test of a 14% underestimate of burn area did not affect our final results because predicted emissions would increase almost equally for business as usual (BAU) management and our scenarios, resulting in no proportional change in NECB. However, the ratio of harvest to fire emissions would be lower.

Projections show that under future climate, atmospheric carbon dioxide, and BAU management, an increase in net carbon uptake due to CO2 fertilization and climate in the mesic ecoregions far outweighs losses from fire and drought in the semiarid ecoregions. There was not an increasing trend in fire. Carbon stocks increased by 2% and 7% and NEP increased by 12% and 40% by 2050 and 2100, respectively.

We evaluated emission reduction strategies in the forest sector: protecting existing forest carbon, lengthening harvest cycles, reforestation, afforestation, and bioenergy production with product substitution. The largest potential increase in forest carbon is in the mesic Coast Range and West Cascade ecoregions. These forests are buffered by the ocean, have high soil water-holding capacity, low risk of wildfire [fire intervals average 260–400 y (18)], long carbon residence time, and potential for high carbon density. They can attain biomass up to 520 Mg C ha−1 (12). Although Oregon has several protected areas, they account for only 9–15% of the total forest area, so we expect it may be feasible to add carbon-protected lands with cobenefits of water protection and biodiversity.

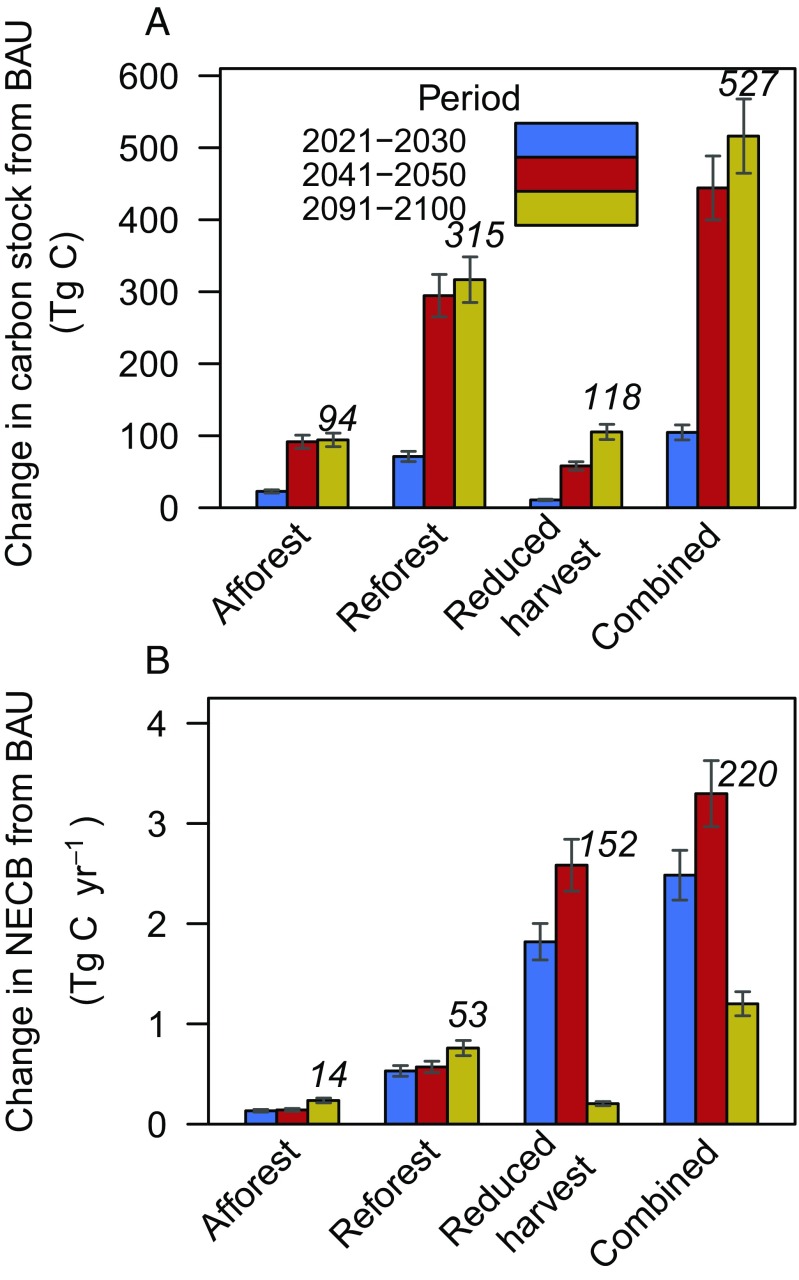

Reforestation of recently forested areas include those areas impacted by fire and beetles. Our simulations to 2100 assume regrowth of the same species and incorporate future fire responses to climate and cyclical beetle outbreaks [70–80 y (13)]. Reforestation has the potential to increase stocks by 315 Tg C by 2100, reducing forest sector net emissions by 5% by 2100 relative to BAU management (Fig. 3). The East and West Cascades ecoregions had the highest reforestation potential, accounting for 90% of the increase (Table S5).

Fig. 3.

Future change in carbon stocks and NECB with mitigation strategies relative to BAU management. The decadal average change in forest carbon stocks (A) and NECB relative to BAU (B) are shown. Italicized numbers over bars indicate mean forest carbon stocks in 2091–2100 (A) and cumulative change in NECB for 2015–2100 (B). Error bars are ±10%.

Afforestation of old fields within forest boundaries and nonfood/nonforage grass crops, hereafter referred to as “grass crops,” had to meet minimum conditions for tree growth, and crop grid cells had to be partially forested (SI Methods and Table S6). These crops are not grazed or used for animal feed. Competing land uses may decrease the actual amount of area that can be afforested. We calculated the amount of irrigated grass crops (127,000 ha) that could be converted to forest, assuming success of carbon offset programs (19). By 2100, afforestation increased stocks by 94 Tg C and cumulative NECB by 14 Tg C, and afforestation reduced forest sector GHG emissions by 1.3–1.4% in 2025, 2050, and 2100 (Fig. 3).

We quantified cobenefits of afforestation of irrigated grass crops on water availability based on data from hydrology and agricultural simulations of future grass crop area and related irrigation demand (20). Afforestation of 127,000 ha of grass cropland with Douglas fir could decrease irrigation demand by 222 and 233 billion m3⋅y−1 by 2050 and 2100, respectively. An independent estimate from measured precipitation and evapotranspiration (ET) at our mature Douglas fir and grass crop flux sites in the Willamette Valley shows the ET/precipitation fraction averaged 33% and 52%, respectively, and water balance (precipitation minus ET) averaged 910 mm⋅y−1 and 516 mm⋅y−1. Under current climate conditions, the observations suggest an increase in annual water availability of 260 billion m3⋅ y−1 if 127,000 ha of the irrigated grass crops were converted to forest.

Harvest cycles in the mesic and montane forests have declined from over 120 y to 45 y despite the fact that these trees can live 500–1,000 y and net primary productivity peaks at 80–125 y (21). If harvest cycles were lengthened to 80 y on private lands and harvested area was reduced 50% on public lands, state-level stocks would increase by 17% to a total of ∼3,600 Tg C and NECB would increase 2–3 Tg C y−1 by 2100. The lengthened harvest cycles reduced harvest by 2 Tg C y−1, which contributed to higher NECB. Leakage (more harvest elsewhere) is difficult to quantify and could counter these carbon gains. However, because harvest on federal lands was reduced significantly since 1992 (NW Forest Plan), leakage has probably already occurred.

The four strategies together increased NECB by 64%, 82%, and 56% by 2025, 2050, and 2100, respectively. This reduced forest sector net emissions by 11%, 10%, and 17% over the same periods (Fig. 3). By 2050, potential increases in NECB were largest in the Coast Range (Table S5), East Cascades, and Klamath Mountains, accounting for 19%, 25%, and 42% of the total increase, whereas by 2100, they were most evident in the West Cascades, East Cascades, and Klamath Mountains.

We examined the potential for using existing harvest residue for electricity generation, where burning the harvest residue for energy emits carbon immediately (3) versus the BAU practice of leaving residues in forests to slowly decompose. Assuming half of forest residues from harvest practices could be used to replace natural gas or coal in distributed facilities across the state, they would provide an average supply of 0.75–1 Tg C y−1 to the year 2100 in the reduced harvest and BAU scenarios, respectively. Compared with BAU harvest practices, where residues are left to decompose, proposed bioenergy production would increase cumulative net emissions by up to 45 Tg C by 2100. Even at 50% use, residue collection and transport are not likely to be economically viable, given the distances (>200 km) to Oregon’s facilities.

Discussion

Earth system models have the potential to bring terrestrial observations related to climate, vulnerability, impacts, adaptation, and mitigation into a common framework, melding biophysical with social components (22). We developed a framework to examine a suite of mitigation actions to increase forest carbon sequestration and reduce forest sector emissions under current and future environmental conditions.

Harvest-related emissions had a large impact on recent forest NECB, reducing it by an average of 34% from 2001 to 2015. By comparison, fire emissions were relatively small and reduced NECB by 12% in the Biscuit Fire year, but only reduced NECB 5–9% from 2006 to 2015. Thus, altered forest management has the potential to enhance the forest carbon balance and reduce emissions.

Future NEP increased because enhancement from atmospheric carbon dioxide outweighed the losses from fire. Lengthened harvest cycles on private lands to 80 y and restricting harvest to 50% of current rates on public lands increased NECB the most by 2100, accounting for 90% of total emissions reduction (Fig. 3 and Tables S5 and S6). Reduced harvest led to NECB increasing earlier than the other strategies (by 2050), suggesting this could be a priority for implementation.

Our afforestation estimates may be too conservative by limiting them to nonforest areas within current forest boundaries and 127,000 ha of irrigated grass cropland. There was a net loss of 367,000 ha of forest area in Oregon and Washington combined from 2001 to 2006 (23), and less than 1% of native habitat remains in the Willamette Valley due to urbanization and agriculture (24). Perhaps more of this area could be afforested.

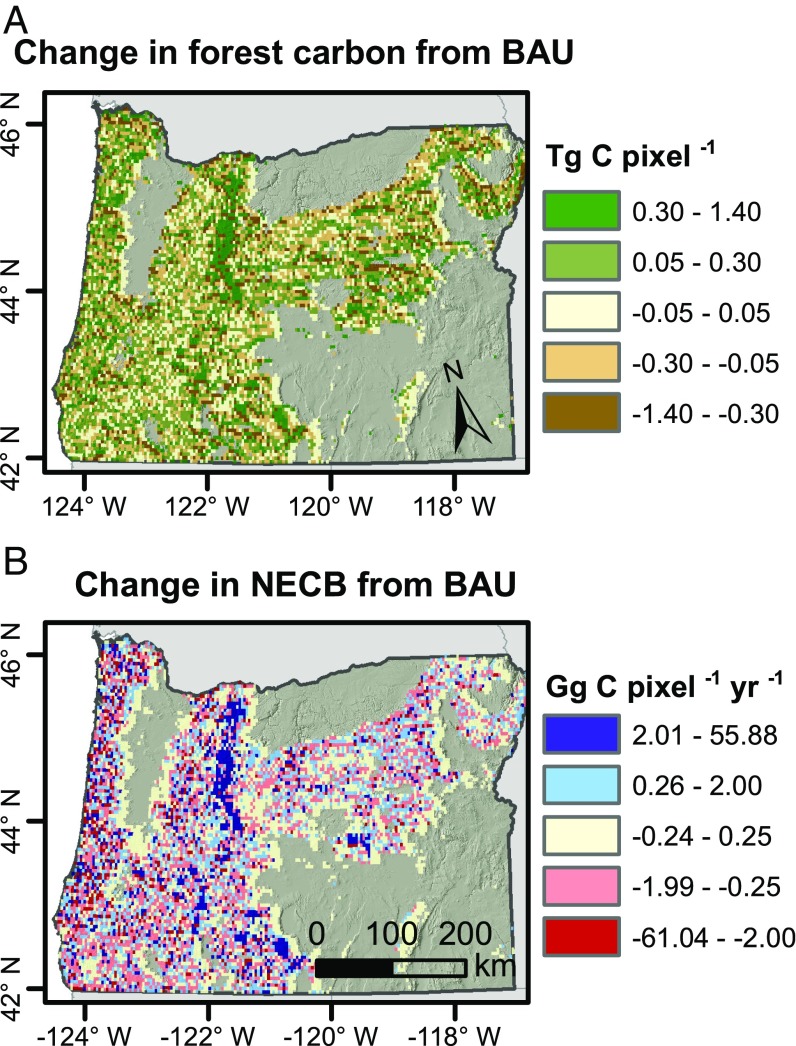

The spatial variation in the potential for each mitigation option to improve carbon stocks and fluxes shows that the reforestation potential is highest in the Cascade Mountains, where fire and insects occur (Fig. 4). The potential to reduce harvest on public land is highest in the Cascade Mountains, and that to lengthen harvest cycles on private lands is highest in the Coast Range.

Fig. 4.

Spatial patterns of forest carbon stocks and NECB by 2091–2100. The decadal average changes in forest carbon stocks (A) and NECB (B) due to afforestation, reforestation, protected areas, and lengthened harvest cycles relative to continued BAU forest management (red is increase in NECB) are shown.

Although western Oregon is mesic with little expected change in precipitation, the afforestation cobenefits of increased water availability will be important. Urban demand for water is projected to increase, but agricultural irrigation will continue to consume much more water than urban use (25). Converting 127,000 ha of irrigated grass crops to native forests appears to be a win–win strategy, returning some of the area to forest land, providing habitat and connectivity for forest species, and easing irrigation demand. Because the afforested grass crop represents only 11% of the available grass cropland (1.18 million ha), it is not likely to result in leakage or indirect land use change. The two forest strategies combined are likely to be important contributors to water security.

Cobenefits with biodiversity were not assessed in our study. However, a recent study showed that in the mesic forests, cobenefits with biodiversity of forest species are largest on lands with harvest cycles longer than 80 y, and thus would be most pronounced on private lands (26). We selected 80 y for the harvest cycle mitigation strategy because productivity peaks at 80–125 y in this region, which coincides with the point at which cobenefits with wildlife habitat are substantial.

Habitat loss and climate change are the two greatest threats to biodiversity. Afforestation of areas that are currently grass crops would likely improve the habitat of forest species (27), as about 90% of the forests in these areas were replaced by agriculture. About 45 mammal species are at risk because of range contraction (28). Forests are more efficient at dissipating heat than grass and crop lands, and forest cover gains lead to net surface cooling in all regions south of about 45° latitude in North American and Europe (29). The cooler conditions can buffer climate-sensitive bird populations from approaching their thermal limits and provide more food and nest sites (30). Thus, the mitigation strategies of afforestation, protecting forests on public lands and lengthening harvest cycles to 80–125 y, would likely benefit forest-dependent species.

Oregon has a legislated mandate to reduce emissions, and is considering an offsets program that limits use of offsets to 8% of the total emissions reduction to ensure that regulated entities substantially reduce their own emissions, similar to California’s program (19). An offset becomes a net emissions reduction by increasing the forest carbon sink (NECB). If only 8% of the GHG reduction is allowed for forest offsets, the limits for forest offsets would be 2.1 and 8.4 million metric tCO2e of total emissions by 2025 and 2050, respectively (Table S6). The combination of afforestation, reforestation, and reduced harvest would provide 13 million metric tCO2e emissions reductions, and any one of the strategies or a portion of each could be applied. Thus, additionality beyond what would happen without the program is possible.

State-level reporting of GHG emissions includes the agriculture sector, but does not appear to include forest sector emissions, except for industrial fuel (i.e., utility fuel in Table S3) and, potentially, fire emissions. Harvest-related emissions should be quantified, as they are much larger than fire emissions in the western United States. Full accounting of forest sector emissions is necessary to meet climate mitigation goals.

Increased long-term storage in buildings and via product substitution has been suggested as a potential climate mitigation option. Pacific temperate forests can store carbon for many hundreds of years, which is much longer than is expected for buildings that are generally assumed to outlive their usefulness or be replaced within several decades (7). By 2035, about 75% of buildings in the United States will be replaced or renovated, based on new construction, demolition, and renovation trends (31, 32). Recent analysis suggests substitution benefits of using wood versus more fossil fuel-intensive materials have been overestimated by at least an order of magnitude (33). Our LCA accounts for losses in product substitution stores (PSSs) associated with building life span, and thus are considerably lower than when no losses are assumed (4, 34). While product substitution reduces the overall forest sector emissions, it cannot offset the losses incurred by frequent harvest and losses associated with product transportation, manufacturing, use, disposal, and decay. Methods for calculating substitution benefits should be improved in other regional assessments.

Wood bioenergy production is interpreted as being carbon-neutral by assuming that trees regrow to replace those that burned. However, this does not account for reduced forest carbon stocks that took decades to centuries to sequester, degraded productive capacity, emissions from transportation and the production process, and biogenic/direct emissions at the facility (35). Increased harvest through proposed thinning practices in the region has been shown to elevate emissions for decades to centuries regardless of product end use (36). It is therefore unlikely that increased wood bioenergy production in this region would decrease overall forest sector emissions.

Conclusions

GHG reduction must happen quickly to avoid surpassing a 2 °C increase in temperature since preindustrial times. Alterations in forest management can contribute to increasing the land sink and decreasing emissions by keeping carbon in high biomass forests, extending harvest cycles, reforestation, and afforestation. Forests are carbon-ready and do not require new technologies or infrastructure for immediate mitigation of climate change. Growing forests for bioenergy production competes with forest carbon sequestration and does not reduce emissions in the next decades (10). BECCS requires new technology, and few locations have sufficient geological storage for CO2 at power facilities with high-productivity forests nearby. Accurate accounting of forest carbon in trees and soils, NECB, and historic harvest rates, combined with transparent quantification of emissions from the wood product process, can ensure realistic reductions in forest sector emissions.

As states and regions take a larger role in implementing climate mitigation steps, robust forest sector assessments are urgently needed. Our integrated approach of combining observations, an LCA, and high-resolution process modeling (4-km grid vs. typical 200-km grid) of a suite of potential mitigation actions and their effects on forest carbon sequestration and emissions under changing climate and CO2 provides an analysis framework that can be applied in other temperate regions.

Materials and Methods

Current Stocks and Fluxes.

We quantified recent forest carbon stocks and fluxes using a combination of observations from FIA; Landsat products on forest type, land cover, and fire risk; 200 intensive plots in Oregon (37); and a wood decomposition database. Tree biomass was calculated from species-specific allometric equations and ecoregion-specific wood density. We estimated ecosystem carbon stocks, NEP (photosynthesis minus respiration), and NECB (NEP minus losses due to fire or harvest) using a mass-balance approach (36, 38) (Table 1 and SI Materials and Methods). Fire emissions were computed from the Monitoring Trends in Burn Severity database, biomass data, and region-specific combustion factors (15, 39) (SI Materials and Methods).

Future Projections and Model Description.

Carbon stocks and NEP were quantified to the years 2025, 2050, and 2100 using CLM4.5 with physiological parameters for 10 major forest species, initial forest biomass (36), and future climate and atmospheric carbon dioxide as input (Institut Pierre Simon Laplace climate system model downscaled to 4 km × 4 km, representative concentration pathway 8.5). CLM4.5 uses 3-h climate data, ecophysiological characteristics, site physical characteristics, and site history to estimate the daily fluxes of carbon, nitrogen, and water between the atmosphere, plant state variables, and litter and soil state variables. Model components are biogeophysics, hydrological cycle, and biogeochemistry. This model version does not include a dynamic vegetation model to simulate resilience and establishment following disturbance. However, the effect of regeneration lags on forest carbon is not particularly strong for the long disturbance intervals in this study (40). Our plant functional type (PFT) parameterization for 10 major forest species rather than one significantly improves carbon modeling in the region (41).

Forest Management and Land Use Change Scenarios.

Harvest cycles, reforestation, and afforestation were simulated to the year 2100. Carbon stocks and NEP were predicted for the current harvest cycle of 45 y compared with simulations extending it to 80 y. Reforestation potential was simulated over areas that recently suffered mortality from harvest, fire, and 12 species of beetles (13). We assumed the same vegetation regrew to the maximum potential, which is expected with the combination of natural regeneration and planting that commonly occurs after these events. Future BAU harvest files were constructed using current harvest rates, where county-specific average harvest and the actual amounts per ownership were used to guide grid cell selection. This resulted in the majority of harvest occurring on private land (70%) and in the mesic ecoregions. Beetle outbreaks were implemented using a modified mortality rate of the lodgepole pine PFT with 0.1% y−1 biomass mortality by 2100.

For afforestation potential, we identified areas that are within forest boundaries that are not currently forest and areas that are currently grass crops. We assumed no competition with conversion of irrigated grass crops to urban growth, given Oregon’s land use laws for developing within urban growth boundaries. A separate study suggested that, on average, about 17% of all irrigated agricultural crops in the Willamette Valley could be converted to urban area under future climate; however, because 20% of total cropland is grass seed, it suggests little competition with urban growth (25).

Landsat observations (12,500 scenes) were processed to map changes in land cover from 1984 to 2012. Land cover types were separated with an unsupervised K-means clustering approach. Land cover classes were assigned to an existing forest type map (42). The CropScape Cropland Data Layer (CDL 2015, https://nassgeodata.gmu.edu/CropScape/) was used to distinguish nonforage grass crops from other grasses. For afforestation, we selected grass cropland with a minimum soil water-holding capacity of 150 mm and minimum precipitation of 500 mm that can support trees (43).

Afforestation Cobenefits.

Modeled irrigation demand of grass seed crops under future climate conditions was previously conducted with hydrology and agricultural models, where ET is a function of climate, crop type, crop growth state, and soil-holding capacity (20) (Table S7). The simulations produced total land area, ET, and irrigation demand for each cover type. Current grass seed crop irrigation in the Willamette Valley is 413 billion m3⋅y−1 for 238,679 ha and is projected to be 412 and 405 billion m3 in 2050 and 2100 (20) (Table S7). We used annual output from the simulations to estimate irrigation demand per unit area of grass seed crops (1.73, 1.75, and 1.84 million m3⋅ha−1 in 2015, 2050, and 2100, respectively), and applied it to the mapped irrigated crop area that met conditions necessary to support forests (Table S7).

LCA.

Decomposition of wood through the product cycle was computed using an LCA (8, 10). Carbon emissions to the atmosphere from harvest were calculated annually over the time frame of the analysis (2001–2015). The net carbon emissions equal NECB plus total harvest minus wood lost during manufacturing and wood decomposed over time from product use. Wood industry fossil fuel emissions were computed for harvest, transportation, and manufacturing processes. Carbon credit was calculated for wood product storage, substitution, and internal mill recycling of wood losses for bioenergy.

Products were divided into sawtimber, pulpwood, and wood and paper products using published coefficients (44). Long-term and short-term products were assumed to decay at 2% and 10% per year, respectively (45). For product substitution, we focused on manufacturing for long-term structures (building life span >30 y). Because it is not clear when product substitution started in the Pacific Northwest, we evaluated it starting in 1970 since use of concrete and steel for housing was uncommon before 1965. The displacement value for product substitution was assumed to be 2.1 Mg fossil C/Mg C wood use in long-term structures (46), and although it likely fluctuates over time, we assumed it was constant. We accounted for losses in product substitution associated with building replacement (33) using a loss rate of 2% per year (33), but ignored leakage related to fossil C use by other sectors, which may result in more substitution benefit than will actually occur.

The general assumption for modern buildings, including cross-laminate timber, is they will outlive their usefulness and be replaced in about 30 y (7). By 2035, ∼75% of buildings in the United States will be replaced or renovated, based on new construction, demolition, and renovation trends, resulting in threefold as many buildings as there are now [2005 baseline (31, 32)]. The loss of the PSS is therefore PSS multiplied by the proportion of buildings lost per year (2% per year).

To compare the NECB equivalence to emissions, we calculated forest sector and energy sector emissions separately. Energy sector emissions [“in-boundary” state-quantified emissions by the Oregon Global Warming Commission (14)] include those from transportation, residential and commercial buildings, industry, and agriculture. The forest sector emissions are cradle-to-grave annual carbon emissions from harvest and product emissions, transportation, and utility fuels (Table S3). Forest sector utility fuels were subtracted from energy sector emissions to avoid double counting.

Uncertainty Estimates.

For the observation-based analysis, Monte Carlo simulations were used to conduct an uncertainty analysis with the mean and SDs for NPP and Rh calculated using several approaches (36) (SI Materials and Methods). Uncertainty in NECB was calculated as the combined uncertainty of NEP, fire emissions (10%), harvest emissions (7%), and land cover estimates (10%) using the propagation of error approach. Uncertainty in CLM4.5 model simulations and LCA were quantified by combining the uncertainty in the observations used to evaluate the model, the uncertainty in input datasets (e.g., remote sensing), and the uncertainty in the LCA coefficients (41).

Model input data for physiological parameters and model evaluation data on stocks and fluxes are available online (37).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Thomas Hilker (deceased) for producing the grass data layer, and Carley Lowe for Fig. 1. This research was supported by the US Department of Energy (Grant DE-SC0012194) and Agriculture and Food Research Initiative of the US Department of Agriculture National Institute of Food and Agriculture (Grants 2013-67003-20652, 2014-67003-22065, and 2014-35100-22066) for our North American Carbon Program studies, “Carbon cycle dynamics within Oregon’s urban-suburban-forested-agricultural landscapes,” and “Forest die-off, climate change, and human intervention in western North America.”

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The CLM4.5 model data are available at Oregon State University (terraweb.forestry.oregonstate.edu/FMEC). Data from the >200 intensive plots on forest carbon are available at Oak Ridge National Laboratory (https://daac.ornl.gov/NACP/guides/NACP_TERRA-PNW.html), and FIA data are available at the USDA Forest Service (https://www.fia.fs.fed.us/tools-data/).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1720064115/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Canadell JG, Raupach MR. Managing forests for climate change mitigation. Science. 2008;320:1456–1457. doi: 10.1126/science.1155458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holtsmark B. The outcome is in the assumptions: Analyzing the effects on atmospheric CO2 levels of increased use of bioenergy from forest biomass. Glob Change Biol Bioenergy. 2013;5:467–473. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Repo A, Tuomi M, Liski J. Indirect carbon dioxide emissions from producing bioenergy from forest harvest residues. Glob Change Biol Bioenergy. 2011;3:107–115. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schlamadinger B, Marland G. The role of forest and bioenergy strategies in the global carbon cycle. Biomass Bioenergy. 1996;10:275–300. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heck V, Gerten D, Lucht W, Popp A. Biomass-based negative emissions difficult to reconcile with planetary boundaries. Nat Clim Chang. 2018;8:151–155. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Field CB, Mach KJ. Rightsizing carbon dioxide removal. Science. 2017;356:706–707. doi: 10.1126/science.aam9726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tollefson J. The wooden skyscrapers that could help to cool the planet. Nature. 2017;545:280–282. doi: 10.1038/545280a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Law BE, Harmon ME. Forest sector carbon management, measurement and verification, and discussion of policy related to climate change. Carbon Manag. 2011;2:73–84. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Law BE. Regional analysis of drought and heat impacts on forests: Current and future science directions. Glob Change Biol. 2014;20:3595–3599. doi: 10.1111/gcb.12651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hudiburg TW, Luyssaert S, Thornton PE, Law BE. Interactive effects of environmental change and management strategies on regional forest carbon emissions. Environ Sci Technol. 2013;47:13132–13140. doi: 10.1021/es402903u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keith H, Mackey BG, Lindenmayer DB. Re-evaluation of forest biomass carbon stocks and lessons from the world’s most carbon-dense forests. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:11635–11640. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901970106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Law B, Waring R. Carbon implications of current and future effects of drought, fire and management on Pacific Northwest forests. For Ecol Manage. 2015;355:4–14. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berner LT, Law BE, Meddens AJ, Hicke JA. Tree mortality from fires, bark beetles, and timber harvest during a hot and dry decade in the western United States (2003–2012) Environ Res Lett. 2017;12:065005. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oregon Global Warming Commission 2017. Biennial Report to the Legislature (Oregon Global Warming Commission, Salem, OR)

- 15.Campbell J, Donato D, Azuma D, Law B. Pyrogenic carbon emission from a large wildfire in Oregon, United States. J Geophys Res Biogeosci. 2007;112:G04014. [Google Scholar]

- 16.King AW, Hayes DJ, Huntzinger DN, West TO, Post WM. North American carbon dioxide sources and sinks: Magnitude, attribution, and uncertainty. Front Ecol Environ. 2012;10:512–519. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilson BT, Woodall CW, Griffith DM. Imputing forest carbon stock estimates from inventory plots to a nationally continuous coverage. Carbon Balance Manag. 2013;8:1. doi: 10.1186/1750-0680-8-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reilly MJ, et al. Contemporary patterns of fire extent and severity in forests of the Pacific Northwest, USA (1985–2010) Ecosphere. 2017;8:e01695. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anderson CM, Field CB, Mach KJ. Forest offsets partner climate‐change mitigation with conservation. Front Ecol Environ. 2017;15:359–365. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Willamette Water 2100 Explorer 2017 Assessing water futures under alternative climate and management scenarios: Agricultural water demand, crop and irrigation decisions. Available at explorer.bee.oregonstate.edu/Topic/WW2100/AgSummaries.aspx. Accessed November 13, 2017.

- 21.Hudiburg T, et al. Carbon dynamics of Oregon and Northern California forests and potential land-based carbon storage. Ecol Appl. 2009;19:163–180. doi: 10.1890/07-2006.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bonan GB, Doney SC. Climate, ecosystems, and planetary futures: The challenge to predict life in Earth system models. Science. 2018;359:eaam8328. doi: 10.1126/science.aam8328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Riitters KH, Wickham JD. Decline of forest interior conditions in the conterminous United States. Sci Rep. 2012;2:653. doi: 10.1038/srep00653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Noss RF, LaRoe ET, Scott JM. Endangered Ecosystems of the United States: A Preliminary Assessment of Loss and Degradation. US Department of the Interior, National Biological Service; Washington, DC: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jaeger W, Plantinga A, Langpap C, Bigelow D, Moore K. Water, Economics and Climate Change in the Willamette Basin. Oregon State University Extension Service; Corvallis, OR: 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kline JD, et al. Evaluating carbon storage, timber harvest, and habitat possibilities for a Western Cascades (USA) forest landscape. Ecol Appl. 2016;26:2044–2059. doi: 10.1002/eap.1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matthews S, O’Connor R, Plantinga AJ. Quantifying the impacts on biodiversity of policies for carbon sequestration in forests. Ecol Econ. 2002;40:71–87. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arnold S, Kagan J, Taylor B. Oregon State of the Environment Report. Oregon Progress Board; Salem, OR: 2000. Summary of current status of Oregon’s biodiversity; pp. 121–126. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bright RM, et al. Local temperature response to land cover and management change driven by non-radiative processes. Nat Clim Chang. 2017;7:296–302. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Betts M, Phalan B, Frey S, Rousseau J, Yang Z. Old-growth forests buffer climate-sensitive bird populations from warming. Diversity Distrib. 2017 doi: 10.1111/ddi.12688. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Architecture 2030 2017 The 2030 Challenge. Available at architecture2030.org. Accessed October 23, 2017.

- 32.Oliver CD, Nassar NT, Lippke BR, McCarter JB. Carbon, fossil fuel, and biodiversity mitigation with wood and forests. J Sustain For. 2014;33:248–275. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harmon ME, Moreno A, Domingo JB. Effects of partial harvest on the carbon stores in Douglas-fir/western hemlock forests: A simulation study. Ecosystems (N Y) 2009;12:777–791. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lippke B, et al. Life cycle impacts of forest management and wood utilization on carbon mitigation: Knowns and unknowns. Carbon Manag. 2011;2:303–333. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gunn JS, Ganz DJ, Keeton WS. Biogenic vs. geologic carbon emissions and forest biomass energy production. GCB Bioenergy. 2011;4:239–242. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hudiburg TW, Law BE, Wirth C, Luyssaert S. Regional carbon dioxide implications of forest bioenergy production. Nat Clim Chang. 2011;1:419–423. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Law BE, Berner LT. NACP TERRA-PNW: Forest Plant Traits, NPP, Biomass, and Soil Properties, 1999-2014. ORNL DAAC; Oak Ridge, TN: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Law BE, Hudiburg TW, Luyssaert S. Thinning effects on forest productivity: Consequences of preserving old forests and mitigating impacts of fire and drought. Plant Ecol Divers. 2013;6:73–85. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meigs G, Donato D, Campbell J, Martin J, Law B. Forest fire impacts on carbon uptake, storage, and emission: The role of burn severity in the Eastern Cascades, Oregon. Ecosystems (N Y) 2009;12:1246–1267. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Harmon ME, Marks B. Effects of silvicultural practices on carbon stores in Douglas-fir western hemlock forests in the Pacific Northwest, USA: Results from a simulation model. Can J For Res. 2002;32:863–877. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hudiburg TW, Law BE, Thornton PE. Evaluation and improvement of the community land model (CLM4) in Oregon forests. Biogeosciences. 2013;10:453–470. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ruefenacht B, et al. Conterminous U.S. and Alaska forest type mapping using forest inventory and analysis data. Photogramm Eng Remote Sens. 2008;74:1379–1388. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peterman W, Bachelet D, Ferschweiler K, Sheehan T. Soil depth affects simulated carbon and water in the MC2 dynamic global vegetation model. Ecol Modell. 2014;294:84–93. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Smith JE, Heath L, Skog KE, Birdsey R. 2006. Methods for calculating forest ecosystem and harvested carbon with standard estimates for forest types of the United States (US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Northeastern Research Station, Newtown Square, PA), General Technical Report NE-343.

- 45.Harmon ME, Harmon JM, Ferrell WK, Brooks D. Modeling carbon stores in Oregon and Washington forest products: 1900–1992. Clim Change. 1996;33:521–550. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sathre R, O’Connor J. Meta-analysis of greenhouse gas displacement factors of wood product substitution. Environ Sci Policy. 2010;13:104–114. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.