Significance

Why has economic inequality risen dramatically over the past few decades even in democracies where individuals could vote for more redistribution? We experimentally study how individuals respond to inequality and find that subjects generally take from richer and give to poorer individuals. However, this behavior removes only a fraction of inequality. Moreover, individuals who give to those who are poorer are generally not the same individuals who also take from others who are richer. These results offer an explanation for the absence of policy interventions that could effectively counter rising differences in wealth: Voters are divided on how to react to inequality in ways that make it difficult to build majority coalitions willing to back political redistribution.

Keywords: inequality, redistribution, democracy, experiment, policy preferences

Abstract

Political polarization and extremism are widely thought to be driven by the surge in economic inequality in many countries around the world. Understanding why inequality persists depends on knowing the causal effect of inequality on individual behavior. We study how inequality affects redistribution behavior in a randomized “give-or-take” experiment that created equality, advantageous inequality, or disadvantageous inequality between two individuals before offering one of them the opportunity to either take from or give to the other. We estimate the causal effect of inequality in representative samples of German and American citizens (n = 4,966) and establish two main findings. First, individuals imperfectly equalize payoffs: On average, respondents transfer 12% of the available endowments to realize more equal wealth distributions. This means that respondents tolerate a considerable degree of inequality even in a setting in which there are no costs to redistribution. Second, redistribution behavior in response to disadvantageous and advantageous inequality is largely asymmetric: Individuals who take from those who are richer do not also tend to give to those who are poorer, and individuals who give to those who are poorer do not tend to take from those who are richer. These behavioral redistribution types correlate in meaningful ways with support for heavy taxes on the rich and the provision of welfare benefits for the poor. Consequently, it seems difficult to construct a majority coalition willing to back the type of government interventions needed to counter rising inequality.

Humanshave always engaged in some degree of wealth redistribution to realize more equitable outcomes (1–3). This is consistent with an extensive body of research based on laboratory experiments documenting that individuals prefer relatively more equal distributions to unequal ones (4–6). However, the massive rise in within-country inequality over the past few decades has by far surpassed increases in redistribution efforts (7–9). This seems surprising since democracies allow citizens to vote for more redistribution (10, 11). We propose an explanation that can reconcile these two facts by highlighting that understanding the absence of large-scale redistribution requires knowledge about the causal impact of favorable and unfavorable distributions of wealth (12) on the willingness of individuals to engage in redistribution (13).

We designed a randomized inequality experiment to study the drivers of redistribution by measuring responses to exogenous changes in inequality as revealed by human reallocation behavior in representative samples of the adult population (see SI Appendix for detailed descriptions of methods, sample, and further results). Our instrument combined a “give-or-take” game with an experiment that randomly varied the level of inequality between two individuals. We first raffled two Amazon gift cards among all survey participants. The two gift cards could take on three values, each corresponding to a different type of inequality. In the “own poorer” condition the values were $/€25 (own) and $/€75 (other). In the “own richer” condition, the value of the gift cards was reversed ($/€75, $/€25). In the “equality” condition, the gift cards were worth $/€50 each. Respondents were randomly assigned to one of those conditions and then given the option to either give to or take from the other winner or to do nothing. Individuals who decided to give or take saw a slider they could drag to indicate how much they wanted to give or take. Respondents could give any amount up to all of the initial endowment to the other winner (if they chose give) or take any amount from the initial endowment of the other winner (if they chose take). A purely self-interested individual would maximize his or her monetary payoff by taking all of the other winner’s endowment under all three treatment conditions. We embedded this experiment in surveys conducted of representative samples of the adult population in the United States (n = 2,749) and Germany (n = 2,217). The experiments were approved by the Internal Review Boards at Washington University in St. Louis (IRB ID 201607129) and Stanford University (eProtocol 38517). All respondents first saw an informed consent text before indicating whether they would like to participate in the survey. SI Appendix provides the exact informed consent text as well as detailed information about the survey and sample.

Our design offers several advantages that help to improve over previous studies. The randomization of advantageous and disadvantageous inequality ensures that any differences in individuals’ allocation choices can be causally attributed to exogenous differences in the initial values of their gift cards. Previous work has primarily relied on observational data for which it is difficult to sustain a causal interpretation of observed correlations between inequality and redistribution (9, 14–18). Some recent experimental work has manipulated information about inequality to explore individual redistribution preferences, although changes in the availability of information are not equivalent to actual changes in the distribution of wealth (19, 20), which is what we study here. Other experimental work has almost exclusively analyzed giving behavior in dictator games that created only one type of extreme inequality in which the dictator had everything while the other person had nothing (21–23) and the dictator could only give to but not take from the other individual (24, 25).

An important recent study (26) has begun to vary the level of inequality while maintaining several of the features that characterize previous experimental work such as the focus on laboratory behavior of students (27), the existence of only one type of (favorable) inequality, and allowing individuals to only give to but not take from one another. By studying representative samples of the American and German adult populations, we can characterize the composition of these societies in terms of human responses to different types of inequality. The use of representative samples is advisable since redistribution behavior among students and other selected subgroups may not necessarily generalize to the voting-eligible population (28). Finally, we develop a within-subjects design to elicit and classify individuals based on their conditional redistribution schedules—that is, their responses to variation in the type (advantageous vs. disadvantageous) and level of inequality. Although this information seems important to explain attitudes toward redistribution among the rich and the poor (29, 30), it has not been collected in existing work on the topic (21, 31).

The Causal Effects of Inequality on Redistribution Behavior

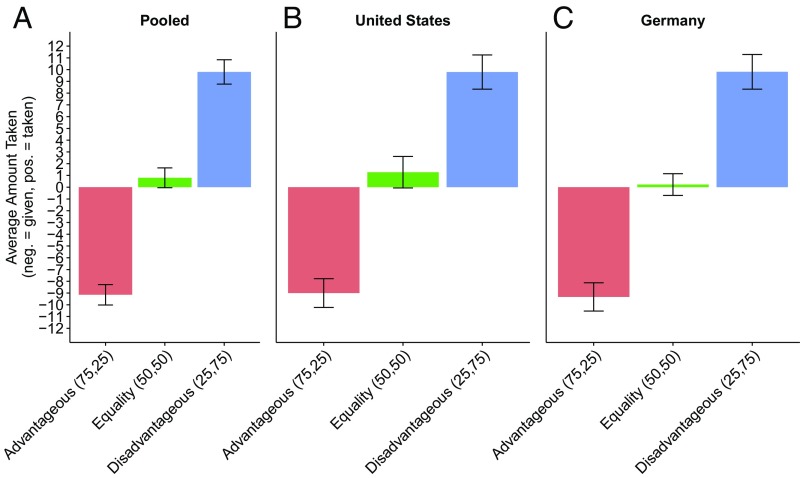

Fig. 1 displays the causal effects of favorable (advantageous) and unfavorable (disadvantageous) inequality on redistribution behavior as observed in the give-or-take experiment. By comparing the average amount of money redistributed in each condition, we can measure the effect of advantageous inequality (own richer) and disadvantageous inequality (own poorer) on human redistribution behavior. We find that a-inequality (own richer) generates a significant level of giving among respondents: On average, richer individuals give $/€9 (12% of their own endowment) to the poorer respondent. Under conditions of equality, the amount reallocated is statistically indistinguishable from zero. In contrast, d-inequality causes significant taking-behavior as individuals who are poorer take $/€10 (13% of the other’s endowment) from the other respondent (see also SI Appendix, Tables S3 and S4). There exist few differences in how Germans and Americans reallocate endowments in response to unequal initial distributions. These results suggest that inequality creates demand for the reallocation of wealth, but the extent of redistribution does not fully remove inequality. This latter finding is consistent with recent experimental results suggesting that even if inequality reflects brute luck, individuals incompletely equalize payoffs (32). We believe that the absence of large-scale policy interventions to reduce increasing inequality reflects that only some individuals are willing to engage in reallocation behavior that equalizes payoffs, whereas others fall short of equalizing.

Fig. 1.

Advantageous (a-)inequality (own richer), equality, and disadvantageous (d-)inequality (own poorer) cause different types of redistribution behavior as measured by the $/€ taken/given in the (A) pooled data, the (B) United States, and (C) Germany. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals calculated from robust standard errors. All differences are statistically significant (P < 0.001). n(total) = 4,966; n(United States) = 2,749; n(Germany) = 2,217.

Estimating Individual-Level Aversion to Inequality

To explore differences in responding to inequality, we asked respondents how much they would give or take conditional on different values of the other winner’s initial gift card value ($/€5, $/€15, $/€25, $/€50, $/€75, $/€85, $/€95) while keeping the initial value of the respondent’s gift card, which was randomly assigned to be either $/€25, $/€50, or $/€75, constant. This provides us with 4,966 individual redistribution schedules that say how much and in which direction each individual would redistribute given a specific distribution of wealth, which here is understood as differences in the value of the two Amazon gift cards. SI Appendix, Fig. S4 shows the frequency of individual redistribution schedules.

To obtain individual-level estimates of how respondents’ redistribution behavior depends on the type and level of inequality, we regress the redistributed amount on the difference in the Amazon gift cards separately for scenarios in which an individual was as rich as or richer than the other (advantageous or a-inequality aversion) and scenarios in which an individual was as poor as or poorer than the other (disadvantageous or d-inequality aversion). SI Appendix, Materials and Methods provides details on this estimation procedure. The estimated coefficient provides us with a measure of the extent to which an individual gives or takes as a function of differences in wealth. In principle, directly interpreting this elasticity also requires taking into account the constant (the redistribution under conditions of equality). However, as the causal evidence reported in Fig. 1 suggests, individuals tend to redistribute an amount close to zero in response to perfect equality. Moreover, we inspect the distribution of the constant estimated in the auxiliary individual-level regressions. We find that the median value is 0 for both aversion to advantageous and aversion to disadvantageous inequality. Therefore, we decide to abstract away from the constant and focus on the estimated aversion parameter to examine differences in how individuals react to changes in inequality.

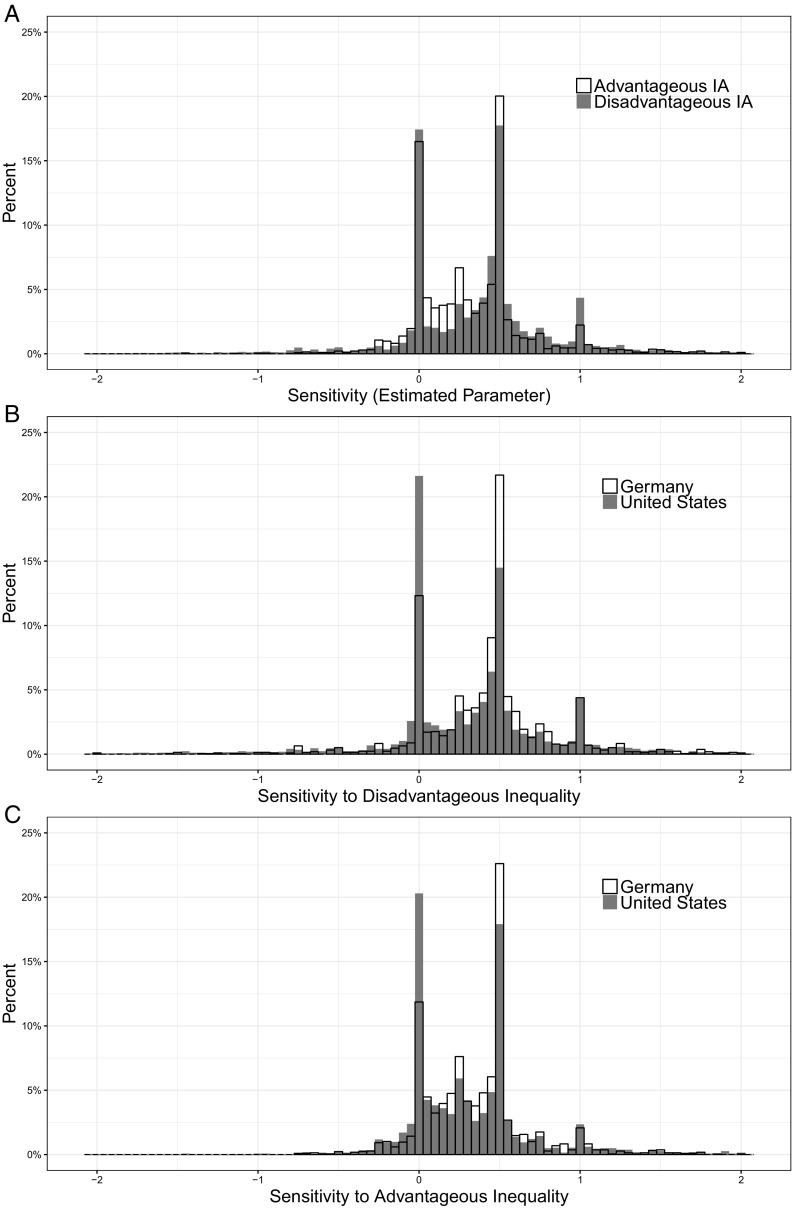

Fig. 2 shows the distributions of individual-level aversion to advantageous and disadvantageous inequality. Parameter values of 0 and 0.5 have a straightforward theoretical interpretation: A value of 0 means that an individual is on average unresponsive to changes in inequality as measured by differences in the gift card values. In contrast, a value of 0.5 indicates that an individual tends to engage in redistribution that equalizes payoffs by either giving or taking 50% of the difference in the values of the two gift cards. The two most frequent values in both distributions are 0 and 0.5. This indicates that a plurality of individuals either accept inequality without engaging in any redistribution or tend to perfectly equalize payoffs.

Fig. 2.

The distributions of individual aversion to a-inequality (white bars) and d-inequality (gray bars) in the give-or-take game differ significantly from each other in the pooled data (A). The distributions of (B) disadvantageous and (C) advantageous inequality aversion also differs significantly between Germany (white bars) and the United States (gray bars). The results are based on a Kolmogorov–Smirnov test of the null hypothesis of no difference between the distributions. The inequality aversion parameters are estimated in a linear regression of the amount taken/given on the difference between individuals’ gift card values in the give-or-take game using respondents’ conditional redistribution schedules (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). See Estimating Individual-Level Aversion to Inequality and SI Appendix, Materials and Methods for details on the underlying estimation procedure. n(Pooled) = 4,796; n(United States) =2,645 (d-inequality), 2,735 (a-inequality); n(Germany) = 2,170 (d-inequality), 2,208 (a-inequality).

Do individuals who are averse to favorable inequality also exhibit aversion to disadvantageous inequality? The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test rejects the null hypothesis of no difference between the two distributions of individual-level inequality aversion (), and the correlation between the inequality aversion parameters is quite weak (, ). This suggests that individuals tend to either equalize only in response to disadvantageous inequality or in response to advantageous inequality, but not both.

When breaking down the distributions of the raw inequality aversion parameters by country, we find that 22% tend to perfectly equalize in Germany when confronted with unfavorable inequality, while only about 15% of Americans remove this type of inequality. Instead, the modal value in the United States is 0 with 20% of respondents leaving the given level of unfavorable inequality unchanged. In contrast, only 12% of Germans are unresponsive to disadvantageous inequality. The stronger tendency of Germans to redistribute proportionally more in response to higher inequality also applies to conditions of advantageous inequality. Twenty-two percent completely remove favorable inequality in Germany, while only 17% eliminate the wealth differences in the give-or-take game in the United States. Among American respondents, the most frequent response to the other individual being poorer (20%) is to leave the distribution of wealth as measured by the gift card values unchanged. In Germany, only 12% refrain from redistribution when confronted with this type of inequality.

The empirical clustering at and around the theoretically meaningful values of 0 (unresponsive) and 0.5 (perfectly equalize) suggests a coding scheme that distinguishes between three redistribution types: Equalizers tend to reallocate an amount that roughly leads to an equal distribution of wealth as measured by the final values of the two Amazon gift cards; that is, on average, respondents classified as equalizers have an elasticity of 0. Nonequalizers do not or only very mildly redistribute wealth. On average, their sensitivity to inequality is estimated at . In Germany and the United States, these two groups comprise the vast majority of individuals (over 70%). Finally, we form a residual category of Other, whose members also tend to redistribute, but their behavior does not seem to be driven by the motivation to equalize payoffs. Instead, this group comprises individuals who either take too much or give too much to equalize payoffs. Therefore, this group consists of strongly altruistic and strongly egoistic individuals whose behavior results in higher levels of postredistribution inequality in the give-or-take game.

Table 1 shows the joint distribution of redistribution types in our representative samples using the classification above for the pooled data and separately by country. We find that 47% of the voting-eligible population can be classified as tending to remove inequality in response to disadvantageous inequality, and the same proportion equalizes when confronted with advantageous inequality. This suggests that the public is divided over how to respond to inequality in ways that make it difficult to build a majority coalition that would be willing to back large-scale redistribution needed to counter rising inequality. In addition, this observation may actually overestimate the coalition for redistribution since only about 30% of all citizens are averse to both disadvantageous and advantageous inequality. This hints at an important explanation for the absence of political redistribution: The group of citizens who would favor the type of policy interventions most effective in leading to lower inequality could be quite small. If we break down our results by country, we find that 38% of all respondents in Germany are averse to both types of inequality, whereas in the United States, only 25% tend to equalize favorable and unfavorable differences in wealth. These results remain very similar when using an alternative classification scheme that varies the cutoff values (see SI Appendix, Materials and Methods and Tables S21–S28).

Table 1.

Frequencies of d-redistribution and a-redistribution types in the pooled sample and by country (weighted)

| A-Redistribution Type | ||||

| D-redistribution type | Equalizer | Nonequalizer | Other | Total |

| Pooled data | ||||

| Equalizer | 30 | 14 | 3 | 47 |

| Nonequalizer | 10 | 17 | 2 | 29 |

| Other | 7 | 9 | 8 | 24 |

| Total | 47 | 39 | 13 | |

| By country—Germany, | ||||

| United States | ||||

| Equalizer | 38, 25 | 15, 13 | 4, 3 | 56, 40 |

| Nonequalizer | 9, 11 | 12, 21 | 2, 3 | 23, 35 |

| Other | 7, 7 | 8, 9 | 7, 9 | 22, 25 |

| Total | 54, 43 | 35, 43 | 12, 14 | |

Types are classified based on the coefficients estimated in individual-level, auxiliary regressions in which we model the amount given as a function of the differences in respondents’ initial gift card values. See SI Appendix, Materials and Methods for estimation details. We use the following coding rules: −0.25≤sensitivity < 0.25, nonequalizer; 0.25≤sensitivity <0.75, equalizer; all other values, other. N = 4, 966.

Individual Redistribution Types and Public Policy

To what extent can the patterns in our experimental data explain citizens’ attitudes toward government redistribution and macrolevel differences in actual redistribution between the United States and Germany? To address this question, we first analyze whether our redistribution type classification, which relies on human behavior as displayed in a highly simplified, two-member society, correlates in theoretically consistent ways with citizens’ opinions on policy instruments that aim at reducing inequality. We focus on two important types of policy instruments: imposing heavy taxes on the rich and the provision of welfare benefits, each of which constitutes a response to unfavorable and favorable inequality, respectively.

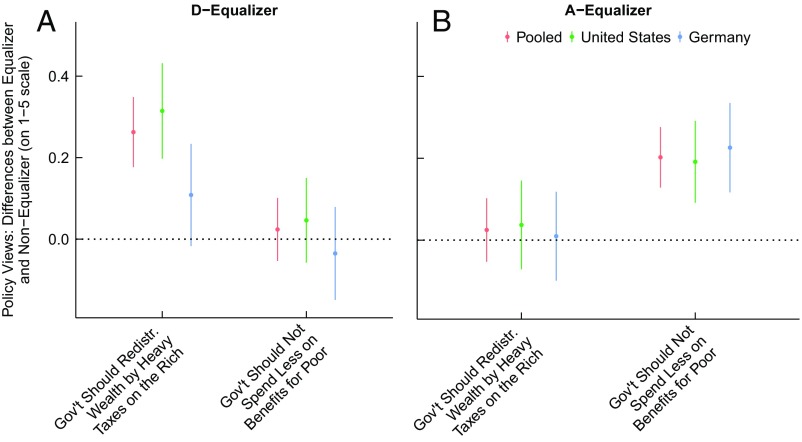

Fig. 3A shows results from a linear regression of individuals’ policy views as measured on a 5-point agree–disagree scale on redistribution type using nonequalizers as the reference group (see also SI Appendix, Tables S13–S20). As one would expect, d-equalizers are significantly more likely to support heavy taxes on the rich than nonequalizers. In contrast, there exists no statistically discernible difference between those two groups when investigating support for upholding current levels of welfare spending. This correlational pattern adds to our confidence in the validity of the proposed classification that distinguishes between d-inequality and a-inequality: Since the behavior we observe under conditions of disadvantageous inequality captures aversion to others being richer, d-equalizers should support policies that aim to reduce the wealth concentration among the rich but not necessarily advocate the provision of benefits meant to make the poorest better off.

Fig. 3.

Redistribution type predicts variation in policy views. Shown are marginal effects of (A) d-equalizer and (B) a-equalizer redistribution types on policy views compared with nonequalizers in the pooled data, United States, and Germany. We use a linear regression to model policy views as a function of redistribution type (using binary indicator variables) and a full set of sociodemographic and political covariates as well as country-fixed effects (SI Appendix, Tables S13–S17 report the underlying estimates in detail). Policy views are measured on a 5-point scale (strongly disagree–strongly agree). Dots with vertical lines indicate point estimates with robust 95% confidence intervals. n(total) = 4,921, n(United States) = 2,733, and n(Germany) = 2,188.

Consistent with this reasoning, Fig. 3B reveals that individuals who reduce advantageous inequality (a-equalizers) are significantly more supportive of avoiding welfare spending cuts. At the same time, as one would expect, a-equalizers and a-nonequalizers do not differ significantly on their support for high taxes on the rich. Overall, these patterns suggest that distinguishing between behavioral responses to a-inequality and d-inequality improves our ability to explain differences in support for government redistribution. Additional results from a validation study in which we randomized whether respondents played the give-or-take game before answering the policy questions or vice versa suggest that the question order did not change the causal effects of inequality on individuals’ redistribution behavior in the give-or-take game (SI Appendix, Table S33). Thus, the correlation between redistribution type and policy views is unlikely to be due to consistency-seeking behavior.

Finally, we explore whether the difference in the frequency of redistribution types between Germany and the United States is consistent with the observable degree of electoral support for political redistribution and the actual level of government redistribution in those two countries. Theoretically, since the share of individuals who are both a- and d-equalizers is considerably smaller in the United States than in Germany, we would expect electoral support for redistribution in the United States to be lower than in Germany. Also, if the unequal distribution of citizens who are both a- and d-equalizers is politically relevant, we should observe more redistribution in Germany than in the United States.

We first explore differences in electoral support for redistribution. To account for cross-country differences in parties’ policy platforms, we compare the major party’s vote share-weighted welfare policy positions. This measure is the product of each party’s welfare policy position (33) and its level of electoral support. The results are reported in SI Appendix, Table S34. We find that both the Social Democratic Party of Germany and the Christian Democratic Union of Germany tend to score considerably higher on this welfare state support measure than the Democratic party and the Republican party in the United States, respectively. This pattern is consistent with our experimental finding in that political redistribution in response to favorable inequality is higher in Germany than in the United States.

Second, we assess the extent of government redistribution observable in Germany and the United States by comparing two important measures of actual redistribution: the reduction in poverty as a function of taxes and transfers, and the reduction in income inequality due to taxes and transfers (SI Appendix, Table S35). We find that on both measures, Germany redistributes considerably more. Through taxes and transfers it reduces the poverty rate by 20 percentage points, whereas the United States reduces the poverty rate by merely 8 percentage points. This difference is all the more striking since the two countries’ before-tax levels of poverty are quite similar (32% in the United States and 36% in Germany; see SI Appendix, Table S35). Similarly, we find that Germany reduces income inequality much more strongly than the United States. These broad patterns appear consistent with our experimental results on the composition of the two countries in terms of how citizens respond to favorable and unfavorable inequality. Knowledge about the joint distribution of a- and d-equalizers may therefore improve our ability to explain both political support for and the actual level of government redistribution in different countries.

Discussion

This study provides causal estimates of how inequality affects redistribution behavior, proposes a method to classify individual redistribution types, and shows that this classification predicts attitudes toward redistributive policies. We believe future work could investigate the potential consequences of relaxing several assumptions of our study since the give-or-take experiment and the setting in which it was embedded strongly simplified the decision-making process that leads to government redistribution in democracies. First, our setting created “mini”-societies in which reallocation was costless. In the real world, redistribution requires bureaucratic effort, and these costs reduce the resources available for reallocation (34). Second, we did not specify the process that generated the initial distribution of wealth. Arguably, if individuals believe that inequality reflects differences in effort as opposed to luck or privilege, this should affect their willingness to redistribute (8, 34–36). Third, our experiment left the social identity of the other winner to whom the individual could give to or take from unspecified. To the extent that individuals treat in-group and out-group members differently, we might expect variation in redistributive behavior conditional on social heterogeneity (37–39). Fourth, we deliberately removed strategic considerations by allowing only one individual to change the distribution of wealth. Plausibly, expectations about how others will respond to higher tax burdens or more generous social benefits can influence how strongly individuals would like to redistribute (34, 35, 40).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Andy Baker, Justin Fox, Catherine E. de Vries, Gregory A. Huber, Roland Hodler, Lukas Linsi, Bill Lowry, Andrew Oswald, David Singer, Margit Tavits, and audiences at the International Political Economy Society’s 2016 annual conference, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the University of Colorado Boulder, Stanford University, the University of Warwick, the 2018 Center for Experimental Political Science NYU Conference, and the London School of Economics and Political Science for helpful comments on earlier versions of this study. M.M.B. and K.F.S. gratefully acknowledge financial support by the Swiss Network for International Studies.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: A full replication archive for this study is publicly available at the Dataverse Project (https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataverse/BLS-PNAS).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1720457115/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Adams RM. The Evolution of Urban Society: Early Mesopotamia and Prehispanic Mexico. Aldine Transaction; New Brunswick, NJ: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hirth KG. Interregional trade and the formation of prehistoric gateway communities. Am Antiq. 1978;43:35–45. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pennisi E. Our egalitarian Eden. Science. 2014;344:824–825. doi: 10.1126/science.344.6186.824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Henrich J, et al. In search of homo economicus: Behavioral experiments in 15 small-scale societies. Am Econ Rev. 2001;91:73–78. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Camerer CF, Fehr E. Measuring social norms and preferences using experimental games: A guide for social scientists. In: Henrich J, Fehr E, Gintis H, editors. Foundations of Human Sociality: Economic Experiments and Ethnographic Evidence from Fifteen Small-Scale Societies. Oxford Univ Press; Oxford: 2004. pp. 55–95. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dawes CT, Fowler JH, Johnson T, McElreath R, Smirnov O. Egalitarian motives in humans. Nature. 2007;446:794–796. doi: 10.1038/nature05651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Piketty T, Saez E. Inequality in the long run. Science. 2014;344:838–843. doi: 10.1126/science.1251936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scheve KF, Stasavage D. Taxing the Rich: A History of Fiscal Fairness in the United States and Europe. Princeton Univ Press; Princeton: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wright G. 2017. The political implications of American concerns about economic inequality. Polit Behav, in press.

- 10.Romer T. Individual welfare, majority voting, and the properties of a linear income tax. J Publ Econ. 1975;4:163–185. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meltzer AH, Richard SF. A rational theory of the size of government. J Polit Econ. 1981;89:914–927. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fehr E, Schmidt KM. A theory of fairness, competition, and cooperation. Q J Econ. 1999;114:817–868. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Norton MI, Ariely D. Building a better America–One wealth quintile at a time. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2011;6:9–12. doi: 10.1177/1745691610393524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perotti R. Growth, income distribution, and democracy: What the data say. J Econ Growth. 1996;1:149–187. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Milanovic B. The median-voter hypothesis, income inequality, and income redistribution: An empirical test with the required data. Eur J Polit Econ. 2000;16:367–410. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kelly NJ, Enns PK. Inequality and the dynamics of public opinion: The self-reinforcing link between economic inequality and mass preferences. Am J Polit Sci. 2010;54:855–870. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lupu N, Pontusson J. The structure of inequality and the politics of redistribution. Am Polit Sci Rev. 2011;105:316–336. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dimick M, Rueda D, Stegmueller D. The altruistic rich? Inequality and other-regarding preferences for redistribution in the US. Q J Polit Sci. 2016;11:385–439. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuziemko I, Norton MI, Saez E, Stantcheva S. How elastic are preferences for redistribution? Evidence from randomized survey experiments. Am Econ Rev. 2015;105:1478–1508. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nair G. 2018. Misperceptions of relative affluence and support for international redistribution. J Polit, in press.

- 21.Cappelen AW, Nielsen UH, Sørensen EØ, Tungodden B, Tyran JR. Give and take in dictator games. Econ Lett. 2013;118:280–283. [Google Scholar]

- 22.List JA. On the interpretation of giving in dictator games. J Polit Econ. 2007;115:482–493. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eckel CC, Grossman PJ, Johnston RM. An experimental test of the crowding out hypothesis. J Publ Econ. 2005;89:1543–1560. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thomsson KM, Vostroknutov A. Small-world conservatives and rigid liberals: Attitudes towards sharing in self-proclaimed left and right. J Econ Behav Organ. 2017;135:181–192. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Engel C. Dictator games: A meta study. Exp Econ. 2011;14:583–610. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Agranov M, Palfrey T. Equilibrium tax rates and income redistribution: A laboratory study. J Publ Econ. 2015;130:45–58. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang B, Li C, Silva HD, Bednarik P, Sigmund K. The evolution of sanctioning institutions: An experimental approach to the social contract. Exp Econ. 2014;17:285–303. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bechtel MM, Scheve KF. Who cooperates? Reciprocity and the causal effect of expected cooperation in representative samples. J Exp Polit Sci. 2017;4:206–228. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cavaillé C, Trump KS. The two facets of social policy preferences. J Polit. 2015;77:146–160. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ballard-Rosa C, Martin L, Scheve KF. The structure of American income tax policy preferences. J Polit. 2017;79:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tammi T. Dictator game giving and norms of redistribution: Does giving in the dictator game parallel with the supporting of income redistribution in the field? J Soc Econ. 2013;43:44–48. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weinzierl M. Popular acceptance of inequality due to innate brute luck and support for classical benefit-based taxation. J Public Econ. 2017;155:54–63. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Volkens A, et al. 2017. The Manifesto Data Collection. Manifesto Project (MRG/CMP/MARPOR) [Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung (WZB), Berlin], Version 2017a.

- 34.Durante R, Putterman L, van der Weele J. Preferences for redistribution and perceptions of fairness: An experimental study. J Eur Econ Assoc. 2014;12:1059–1086. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fisman R, Jakiela P, Kariv S, Markovits D. The distributional preferences of an elite. Science. 2015;349:aab0096. doi: 10.1126/science.aab0096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brosnan SF, de Waal FBM. Monkeys reject unequal pay. Nature. 2003;425:297–299. doi: 10.1038/nature01963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huber JD, Ting MM. , pork and elections. J Eur Econ Assoc. 2017;11:1382–1403. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alesina A, Glaeser E, Sacerdote B. Why doesn’t the United States have a European-style welfare state? Brookings Pap Econ Activ. 2001;2:187–277. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gilens M. Why Americans Hate Welfare: Race, Media, and the Politics of Antipoverty Policy. University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Foellmi R, Oechslin M. Why progressive redistribution can hurt the poor. J Publ Econ. 2008;92:738–747. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.