Significance

Cytidine deaminases of the AID/APOBEC family mutate the genetic material of pathogens or contribute to the generation and diversification of antibody repertoires in jawed vertebrates. In the extant jawless vertebrate, the lamprey, two members of the AID/APOBEC family are implicated in the somatic diversification of variable lymphocyte receptor (VLR) repertoires. We discovered an unexpected diversity of cytidine deaminase genes within and among lamprey species. The cytidine deaminases with features comparable to jawed vertebrate AID are always present, suggesting that they are involved in essential processes, such as VLR assembly. In contrast, other genes show a remarkable copy number variation, like the APOBEC3 genes in mammals. This suggests an unexpected similarity in functional deployment of AID/APOBEC cytidine deaminases across all vertebrates.

Keywords: antigen receptor diversification, jawless vertebrate, evolution, DNA-editing enzymes, RNA-editing enzymes

Abstract

Cytidine deaminases of the AID/APOBEC family catalyze C-to-U nucleotide transitions in mRNA or DNA. Members of the APOBEC3 branch are involved in antiviral defense, whereas AID contributes to diversification of antibody repertoires in jawed vertebrates via somatic hypermutation, gene conversion, and class switch recombination. In the extant jawless vertebrate, the lamprey, two members of the AID/APOBEC family are implicated in the generation of somatic diversity of the variable lymphocyte receptors (VLRs). Expression studies linked CDA1 and CDA2 genes to the assembly of VLRA/C genes in T-like cells and the VLRB genes in B-like cells, respectively. Here, we identify and characterize several CDA1-like genes in the larvae of different lamprey species and demonstrate that these encode active cytidine deaminases. Structural comparisons of the CDA1 variants highlighted substantial differences in surface charge; this observation is supported by our finding that the enzymes require different conditions and substrates for optimal activity in vitro. Strikingly, we also found that the number of CDA-like genes present in individuals of the same species is variable. Nevertheless, irrespective of the number of different CDA1-like genes present, all lamprey larvae have at least one functional CDA1-related gene encoding an enzyme with predicted structural and chemical features generally comparable to jawed vertebrate AID. Our findings suggest that, similar to APOBEC3 branch expansion in jawed vertebrates, the AID/APOBEC family has undergone substantial diversification in lamprey, possibly indicative of multiple distinct biological roles.

The activation-induced-cytidine-deaminase/apolipoprotein-B-RNA-editing-catalytic polypeptide-like (AID/APOBEC) family of enzymes comprises a group of RNA and DNA cytidine deaminases that catalyze a (d)C-to-(d)U transition (1, 2). All family members share a common structural core consisting of a central β-sheet, which is made up of five strands, sandwiched between six or seven α-helices joined by flexible loops of variable lengths. The deaminase superfamily is characterized by two highly conserved motifs, which contribute two cysteines and one histidine—chelating a Zn atom—and a proton-donating glutamic acid to the catalytic pocket (3). Many APOBEC genes are involved in immune responses and hence have shown rapid expansion in jawed vertebrates, particularly notable for the antiviral APOBEC3 genes; for example, a single APOBEC3 gene is present in rodents, expanding to three copies in cattle and seven copies in primates (4). Recent work identifying several AID/APOBEC genes across metazoans, including nonvertebrates, has indicated that lineage-specific expansions, rapid evolution, and gene loss are also prevalent evolutionary trends, suggesting a primary role for them in immune responses (2).

A unique and functionally conserved AID/APOBEC gene present in all jawed vertebrates encodes activation-induced deaminase (AID) (5). First identified in mouse (6) and human (7), AID has been shown to be required for the somatic diversification of Ig genes in all jawed vertebrates examined so far (4). Upon B-cell activation, AID drives secondary diversification of antibody repertoires by the induction of somatic hypermutation of the variable antibody regions resulting in higher affinity variants; in addition, AID-mediated mutations result in double-strand breaks downstream of constant region exons, thus initiating class switch recombination to alter the Ig’s isotype without changing antigen specificity (8, 9). In chickens, rabbits, and some cattle, the generation of the primary antibody repertoire depends on AID-mediated gene conversion (10–15). Despite some differences in the precise composition of the target sequence, AID preferentially deaminates cytidines in WRC (W = A or T, and R = A or G) motifs in single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) (16–23). Critically, AID from all jawed vertebrates so far analyzed exhibit the unusual and unique biochemical property of high-affinity DNA binding with a low catalytic rate (22, 24, 25).

The extant jawless vertebrates (agnathans), namely hagfishes and lampreys, lack Ig-based adaptive immunity and have instead evolved an alternative system, producing diverse clonal repertoires of leucine-rich repeat (LRR) encoding variable lymphocyte receptors (VLRs) (26–31). Lampreys possess three distinct lymphocyte populations: two T-like and one B-like, each distinguished by expression of a unique VLR isotype (32–35). The B-like cells express a GPI-linked VLRB receptor, which can also be secreted in multimeric complexes that bind directly to antigen in an antibody-like manner (36, 37). Both T-like lineages express distinct membrane-bound VLRs, VLRA or VLRC, and assemble their receptors in thymus-like organs termed thymoids, where they likely undergo a selection process that modifies their final repertoires (38–40).

A copy–paste gene conversion-like process comparable to Ig gene conversion has been proposed to underlie VLR gene assembly in lamprey (27, 41, 42). Two cytidine deaminase genes, designated cytidine deaminase 1 (PmCDA1) and 2 (PmCDA2) were subsequently identified in the genome of the sea lamprey Petromyzon marinus (41). PmCDA1 is a single exon gene encoding a polypeptide of 208 amino acids, whereas PmCDA2 encodes a protein of 331 amino acids in four exons. PmCDA2 is preferentially expressed in VLRB+ lymphocytes isolated from the kidney and typhlosole, whereas PmCDA1 expression is associated with VLRA+ and VLRC+ lymphocytes; RNA in situ hybridization analysis indicates the lamprey thymus equivalent as the sole site of PmCDA1 expression in lamprey larvae (38). However, so far, evidence that either PmCDA acts directly on any of the VLR loci is lacking (43).

Despite significant deviation from the primary sequences of jawed vertebrate AID/APOBEC enzymes, sequence analysis of lamprey CDAs suggested that they are active enzymes related to the classical AID/APOBEC family of proteins (2, 41, 44). Indeed, using bacterial and yeast expression and in vitro assays, PmCDA1 was shown to deaminate cytidines (41); however, no such activity was reported for PmCDA2. Despite remarkable sequence divergence (<20% amino acid identity) from mammalian AID/APOBEC proteins, PmCDA1 is an active cytidine deaminase enzyme that shares AID-like characteristics of high-affinity substrate binding, low catalytic rate, temperature adaptation, and trinucleotide sequence specificity (25); together, these findings suggest the possibility that PmCDA1 may have a similar DNA-editing function in vivo.

Given the evolutionary dynamics of the AID/APOBEC gene family, we revisited the lamprey CDA gene family to gain further insight into their potential diversity and evolutionary history. In addition to identifying splice forms of the CDA2 gene, we discovered an unexpected diversity of CDA1-like genes in lampreys with implications for their potential roles in VLR receptor assembly and immune defense.

Results

Identification of CDA-Like Genes in Lamprey.

Using the two identified CDA genes of P. marinus, designated PmCDA1 (accession EF094822) and PmCDA2 (accession EF094823) (41), we conducted homology searches in genomic sequences of the European brook lamprey Lampetra planeri and the related Japanese lamprey Lethenteron japonicum. Though assembly of the L. japonicum genome from the testis of a single individual has recently been reported (45), no such resource yet exists for L. planeri. Therefore, we generated shotgun libraries using genomic DNAs isolated from two L. planeri larvae, Lp#173 and Lp#175 (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 and Table S1). Initial homology hits were extended in both directions and the sequences assembled into contigs, often containing full-length genes or particular exons of interest. For comparative purposes, we generated a similar resource from testis DNA of the same individual (here designated Lj#1) that was used previously for the assembly of the L. japonicum genome (45). Using each of the PmCDA2 exon sequences as queries, closely related sequences were found in both L. japonicum and L. planeri genomes; identical exon/intron boundaries and similar predicted protein sequences suggested that L. japonicum and L. planeri each possess a single CDA2 gene (SI Appendix, Fig. S2 A and B).

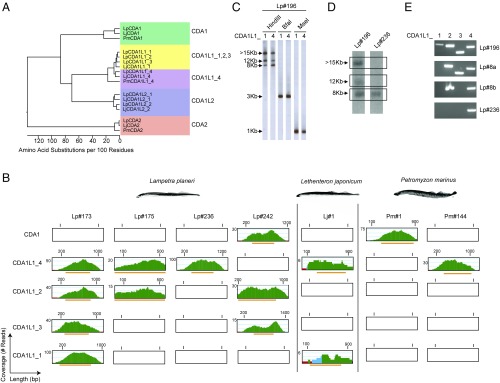

By contrast, a similar approach using the PmCDA1 sequence as a query against the two L. planeri larvae sequence collections failed to recover closely related sequences. Instead, several different CDA1-like genes were identified (Fig. 1 A and B and SI Appendix, Fig. S3). These genes belong to two distinct but related groups, which we termed CDA1-like 1 (CDA1L1) and CDA1-like 2 (CDA1L2) (Fig. 1A). The genome of individual Lp#173 contained four different CDA1L1 genes (CDA1L1_1 to CDA1L1_4) and a single CDA1L2 gene (CDA1L2_1) (Fig. 1B and SI Appendix, Fig. S1). Analysis of the genome sequences of individual Lp#175 identified one CDA1L1_2 gene (with 99.5% sequence identity at amino acid level to the corresponding gene in individual Lp#173) and one CDA1L1_4 gene (with complete identity at the amino acid level); intriguingly, no sequences corresponding to CDA1L1_1 and CDA1L1_3 were found (Fig. 1B and SI Appendix, Fig. S1). One of the two CDA1L2 sequences retrieved from the Lp#175 genome was identical to CDA1L2_1 of Lp#173; a second distinct sequence (CDA1L2_2) shared 89.4% identity with CDA1L2_1 at the amino acid level (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). To confirm the presence of these CDA1L1 genes in other individuals, CDA1L1_1, CDA1L1_2, CDA1L1_3, and CDA1L1_4 genes were amplified using gene-specific primers from genomic DNAs isolated from the whole body of another larva (Lp#196) (SI Appendix, Figs. S1 and S4A). Genomic DNA from individual Lp#196 was then subjected to Southern filter hybridization analysis using probes generated from LpCDA1L1_1 and LpCDA1L1_4 gene sequences, representing the two most divergent sequences of the CDA1L1 gene family. In HindIII digests, three fragments of ∼7.5 kb, 12 kb, and ≥15 kb were detected; both probes (with 92% nucleotide identity) hybridized to the same three bands, albeit with different intensities, indicating that the genomic fragments also differ in nucleotide sequence (Fig. 1C). By contrast, digests of genomic DNA with the restriction enzymes BfaI and MseI produced fragments of ∼3 kb and 1 kb, respectively, indicating that the flanking sequences of the four CDA1L1 genes are similar (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

Identification and difference in copy number of CDA1-like genes in lamprey. (A) Phylogenetic tree showing relationship between lamprey CDA1, CDA1-like, and CDA2 sequences. Distance values are presented as number of amino acid changes per 100 residues calculated using the Kimura distance formula and multiplied by 100 (76). (B) Read coverage plots in whole genome sequences. Green color indicates a coverage by more than five reads; blue, two to five reads; and red, a single read. Orange bars correspond to region of the contigs containing the ORFs of the exons. (C) Representative Southern filter hybridizations of genomic DNAs of Lampetra planeri Lp#196 after digestion with the indicated restriction enzymes hybridized with the indicated probes (sequences deposited as GenBank entries, MG495254 and MG495256). (D) Southern filter hybridizations of genomic HindIII restriction digests of genomic DNAs of L. planeri individuals with different CDA1L1 gene copy numbers hybridized with CDA1L1_4 probe used in C. The autoradiographic images shown are taken from different parts of the same film. (E) PCR analysis of CDA1L1 genes from L. planeri individuals with different CDA1L1 copy numbers. The identities of PCR products were confirmed by sequencing.

Homology searches of the L. japonicum genome assembly and the shotgun library of the same DNA revealed clear homologs of CDA2 exons (SI Appendix, Fig. S2), but no highly conserved PmCDA1 homolog was found. However, a single CDA1L1 (LjCDA1L1) gene was identified in the genome assembly (scaffold 00511: 303521–304156), sharing 93% identity at the protein sequence level with LpCDA1L1_1 (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). Sequences corresponding to this gene were also identified in the shotgun library, along with sequences of a second gene (designated Lj_CDA1L1_4), exhibiting 89% identity with LpCDA1L1_4 at the protein sequence level (SI Appendix, Fig. S4B). Two CDA1L2 genes (designated LjCDA1L2_1 and LjCDA1L2_2), which exhibit between 84% and 91% sequence identity to LpCDA1L2_1 and LpCDA1L2_2 at the protein sequence level were also identified in the L. japonicum genome assembly (scaffold 00078: 2091925–2092732; contig APJL01098605: 2832–2013) and in the collection of L. japonicum shotgun reads (SI Appendix, Fig. S5 A and B). Further analyses uncovered a previously unappreciated complexity of splice variants of CDA1-like and CDA2 genes, all of which are predicted to introduce variations in their C-terminal regions (SI Appendix, Figs. S2–S7 and Table S2); the functional significance of these variants is unclear.

Divergence and Diversity Among CDA1 and CDA1-Like Genes in Lamprey.

We searched the available sequence collections of P. marinus for the presence of genes corresponding to the divergent CDA1-like genes identified in the L. planeri and L. japonicum genomes. We also sequenced the genomes of four additional individuals: two P. marinus (Pm#1 and Pm#144) and two further L. planeri specimens (Lp#236 and Lp#242) (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). Sequences corresponding to the four exons of PmCDA2 were readily identifiable in the genomic sequence collections of all four individuals (SI Appendix, Fig. S2B). Notably, the exon sequences of CDA2 genes of Pm#1 and Pm#144 were identical to the previously described P. marinus sequence and clearly distinguishable from the corresponding L. planeri and L. japonicum CDA2 gene sequences (SI Appendix, Fig. S2A). Similarly, the exon sequences of CDA2 genes from Lp#236 and Lp#242 were identical to those identified in Lp#173 and Lp#175. Analysis of the Pm#1 genome revealed the presence of sequences corresponding to the previously described PmCDA1 gene, with no evidence of additional CDA1L1 sequences (Fig. 1B and SI Appendix, Fig. S4B). By contrast, the second P. marinus individual (Pm#144) lacked PmCDA1 homologs, but instead exhibited sequences homologous to LpCDA1L1_4 (Fig. 1 A and B and SI Appendix, Fig. S4B). As is the case for many L. planeri individuals, the Lp#236 shotgun genome sequences lacked detectable PmCDA1 sequences, but contained a single CDA1L1 gene, CDA1L1_4 (Fig. 1B and SI Appendix, Fig. S4B); this result was confirmed by Southern filter hybridization (Fig. 1D) and PCR (Fig. 1E) analyses. Indeed, additional variations in CDA1L1 gene content were revealed upon further study; the genomes of L. planeri individuals Lp#8a and Lp#8b contained three and two CDA1L1 genes, respectively (Fig. 1E). One additional combination of three CDA1L1 genes was observed in a specimen of another lamprey species, Lampetra fluviatilis (Lf#33) (SI Appendix, Table S3); L. planeri and L. fluviatilis are considered to be highly related paired species (46). Conversely, while the genome sequences of Lp#242 revealed copies of LpCDA1L1_2 and LpCDA1L1_3, no LpCDA1L1_4-related sequences were found. However, this individual possessed a clear ortholog of PmCDA1, named LpCDA1 (Fig. 1 and SI Appendix, Fig. S1). This LpCDA1 sequence was not detectable in any of the other L. planeri genomes studied here. Of note, in the course of a study aimed at genetic interference with lamprey gene functions, we obtained a cDNA clone of a CDA1-like gene from an additional L. japonicum specimen (Lj#2); interestingly, the derived protein sequence (designated LjCDA1) is clearly distinct, yet more related to LpCDA1 and PmCDA1 than to LjCDA1L1_4 sequences (Fig. 1A and SI Appendix, Fig. S3B). Although it was not possible to examine the presence of additional sequences in this individual, this observation indicates that L. japonicum, like P. marinus and L. planeri also exhibit interindividual differences in the type, and possibly also the number, of CDA1-like genes.

Collectively, these results reveal previously unappreciated aspects of the CDA1-like gene family. First, they indicate a striking variability in the number of CDA1L1 genes, best illustrated by L. planeri genomes, which encode either four, three, two, or just one CDA1-like genes. Second, the representation of CDA1-like genes in lamprey genomes appears to follow a certain pattern; irrespective of the total number of CDA1L1 genes present in L. planeri genomes, the CDA1L1_4 gene is almost always present [7/8 animals analyzed by PCR and/or whole genome sequencing (WGS)]. The single animal that lacked this gene (Lp#242) instead possessed a bona fide ortholog to PmCDA1. This striking intraspecific variability of CDA1-like genes is also present in the P. marinus genomes analyzed here; individuals of this species either possess the canonical PmCDA1 gene or instead exhibit a homolog of the CDA1L1_4 gene. A similar phenomenon appears to hold for individuals of L. japonicum, possessing variants of either the CDA1L1_4 or the CDA1 genes. Assuming that the canonical PmCDA1 gene has essential and nonredundant functions in supporting cellular immunity in P. marinus, our observations predicted the presence of structural and/or functional similarities between CDA1 and CDA1L1_4 genes, which we sought to evaluate further.

Next, we examined the complement of CDA1L2-like sequences. The genomes of Lp#236 and Lp#242 contained a single CDA1L2 sequence (SI Appendix, Fig. S5A) with 100% identity to LpCDA1L2_1 of Lp#173 (SI Appendix, Fig. S5B). Interestingly, for P. marinus, identical pseudogenized variants of a single CDA1L2 gene were identified in both the published genome assembly (scaffold GL479158: 189872–190543) (47) and the sequence collections obtained from the two P. marinus individuals studied here; the differences between these three sequences were confined to only four SNPs (SI Appendix, Fig. S5B), indicating that they are orthologous sequences. Notably, the P. marinus CDA1L2 gene exhibits several insertion/deletion mutations and a large internal deletion, compared with the seemingly functional L. planeri and L. japonicum CDA1L2 genes. However, another sequencing study identified a complete version of CDA1L2 in a P. marinus individual (referred to as CDA4 in GenBank accession no. ALO81575.1; SI Appendix, Fig. S3A) that is closely related to the sequence of L. japonicum CDA1L2_2, suggesting that like CDA1L1 genes, the CDA1L2 genes are also subject to pseudogenization or loss.

Predicted Biochemical Features and Structures of Lamprey CDA Proteins.

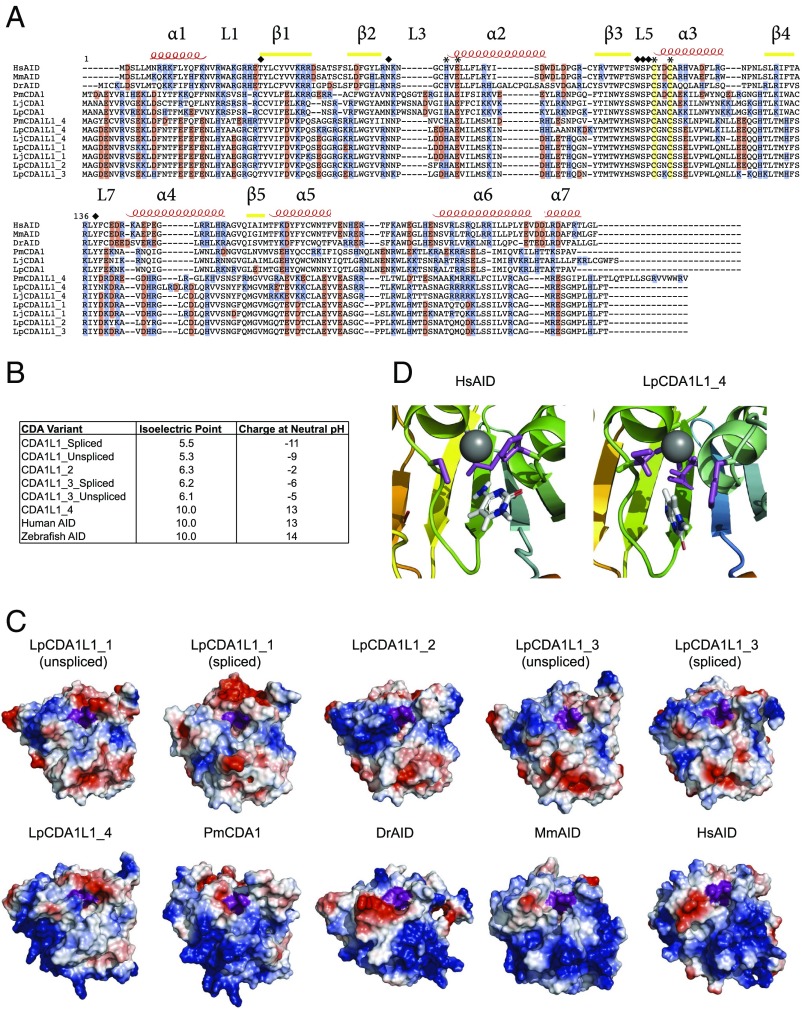

The lamprey deaminases comprise a distinct clade of the AID/APOBEC sequences that are exclusively found in jawed vertebrates (SI Appendix, Fig. S3A) (44). To understand the diversification of the CDA genes in lampreys, we generated a comprehensive alignment of all available sequences from different lamprey species. With respect to a presumptive role of CDA1-like genes in VLRA and VLRC gene assembly, the results summarized above suggest that in the absence of CDA1, CDA1L1_4 might play a similar role. While CDA1 and CDA1L1_4 proteins are not specifically related to the exclusion of other CDA1-like proteins, they encode a stretch of basic amino acid residues toward the C-terminal end of the proteins that are not present in the predicted protein sequences encoded by other CDA1L1 and the CDA1L2 genes (Fig. 2A). Consistent with this characteristic feature, the isoelectric points (pI) for PmCDA1 and CDA1L1_4 fall in the basic range (pI = 9.4, 10, respectively), similar to mammalian and fish AID (25), whereas the isoelectric points of other CDA1L1 proteins are in the neutral to acidic range, closer to that of APOBEC3 enzymes (Fig. 2B) (3, 48, 49).

Fig. 2.

Structural characteristics of CDA1-like proteins. (A) Sequence alignment of Homo sapiens AID (HsAID), Mus musculus AID (MmAID), Danio rerio AID (DrAID), Petromyzon marinus CDA1 (PmCDA1), Lampetra planeri CDA1 (LpCDA1), L. japonica CDA1 (LjCDA1), L. planeri (Lp), and L. japonica (Lj) LpCDA1L1 proteins. The secondary structure of HsAID was used to denote α-helical (α), β-strand (β), and secondary catalytic loop (L) regions. The conserved Zn-coordinating residues (cysteines, histidine, and glutamic acid) are denoted by asterisks. Conserved secondary catalytic residues are indicated by diamonds; note that the replacement of threonine 27 by cysteine in PmCDA1 (and by inference in LpCDA1 and LjCDA1) does not impair enzymatic activity (25) (Fig. 3). Positively and negatively charged residues are colored blue and red, respectively. (B) Summary table indicating the predicted chemical properties of human AID and L. planeri CDA1L1 proteins. (C) Representative surface topology models of the lamprey CDA1L1 proteins, compared with P. marinus CDA1 (PmCDA1), zebrafish AID (DrAID), mouse AID (MmAID), and human AID (HsAID), respectively. Positively and negatively charged residues are colored blue and red, respectively. The catalytic pockets are indicated as an indentation in the center, with the Zn-coordinating triad of two cysteines and a histidine, as well as the catalytic glutamic acid colored purple. The net charge differed among the LpCDA1L1 genes such that LpCDA1L_1– 3 were net-negatively charged, while LpCDA1L1_4 was net-positively charged, akin to PmCDA1, DrAID, MmAID, and HsAID. Regardless of net charge, a concentration of positively charged residues near the catalytic pocket in all LpCDA1L1 proteins is notable. (D) Models of the catalytic pockets of LpCDA1L1_4 and human AID (HsAID) docked with (d)C in a deamination-feasible configuration, showing the interactions between the Zn-coordinating triad and target (d)C; the coordinated Zn is depicted as a gray sphere, with the Zn-coordinating and catalytic glutamic acid residues colored purple.

Next, we sought to examine whether these newly identified transcripts of CDA1L1 genes could potentially encode cytidine deaminase enzymes. To this end, we first generated predicted model structures of each variant based on resolved X-ray and NMR structures of five related AID/APOBEC enzymes; this approach is based on a computational methodology, which allowed us—in combination with biochemical verification—to present the first native and functional structure of human AID (50) that was subsequently confirmed by a partial X-ray crystal structure (51). We noted that all variants form the conserved core structure of a central β-sheet, flanked by 6–7 α-helices, which is the common hallmark of the AID/APOBEC core structure (Fig. 2C and SI Appendix, Fig. S8A) (3). Although the core structure of the CDA1L1 variants was well conserved with that of AID/APOBECs, we noted significant differences among the variants in predicted surface charge composition (Fig. 2C), corresponding to aforementioned isoelectric point differences (Fig. 2B). CDA1L1_1 (both splice variants), CDA1L1_2, and CDA1L1_3 (both splice variants) have an acidic pI and exhibit negative surface charges at neutral pH, while CDA1L1_4 is the only variant that exhibits a basic pI and a highly positively charged surface, identical to the positive charge predicted for human and zebrafish AIDs, and PmCDA1 (Fig. 2B). Indeed, a comparison of structural models indicates a surprisingly high degree of similarity between mammalian AID, CDA1L1_4, and PmCDA1 (Fig. 2C). Despite the predicted surface composition differences, we noted that all variants formed the conserved surface groove and core architecture of the catalytic pocket of AID/APOBECs, with the characteristic Zn-coordinating triad of histidine and two cysteines, and the catalytic proton-donating glutamic acid that is necessary for the process of cytidine deamination (for both splice variants of CDA1L1_1 and CDA1L1_3, and CDA1L1_2, the coordinates are H64, E66, C95, and C98; for CDA1L1_4, the coordinates are H64, E66, C96, and C99) (Fig. 2A and SI Appendix, Fig. S8A). In addition to conservation of the core catalytic residues, we noted conservation of the most important so-called secondary catalytic residues, which impact deamination by forming the walls or floors of the catalytic pocket, stabilizing the core catalytic residues and contributing to the stabilization of the (d)C substrate in deamination-conducive angles within the catalytic pocket (25, 50). In human AID, key secondary catalytic residues are T27, N51, W84, S85, P86, and Y114 (25, 50); indeed, these residues are also conserved in the primary and predicted tertiary structures of the newly identified lamprey proteins, suggesting that they too possess a catalytically active pocket.

To examine whether the structure of this catalytic pocket could adopt a deamination-conducive conformation, a polynucleotide ssDNA substrate was docked with each predicted protein structure. We observed that the putative catalytic pockets of all variants were capable of accommodating a (d)C, in orientations that have previously been shown to support a deamination reaction (Fig. 2D and SI Appendix, Fig. S9) (25, 50). The aforementioned computational-biochemical studies of AID structure and the subsequent partial AID X-ray crystal structure (51) both suggested the presence of two deamination-conducive ssDNA binding grooves on the surface of human AID; interestingly, we recently reported that DrAID and PmCDA1 bind ssDNA using the same positively charged surface residues (52). In the present ssDNA docking experiments, we observed similar productive enzyme–ssDNA complexes for CDA1L1_1–4, further hinting at the possibility that all variants have the potential to be active cytidine deaminase enzymes.

Cytidine Deaminase Activity of Lamprey CDAs.

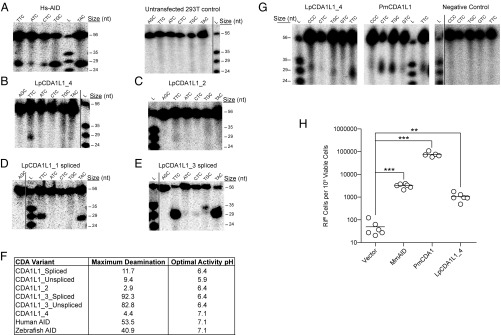

To functionally examine the cytidine deaminase activities of lamprey CDAs, we expressed each of the six CDA1L1 variants of L. planeri in HEK293T cells. As positive controls, human and zebrafish AID proteins, both of which have been extensively characterized as active cytidine deaminases (24, 25, 50, 52), were expressed in 293T cells in parallel (SI Appendix, Fig. S8B). Extracts of 293T cells expressing each protein were tested for cytidine deamination in the standard alkaline cleavage assay for cytidine deaminase activity. It has previously been demonstrated that, compared with human AID, AID orthologs from bony and cartilaginous fish, as well as PmCDA1, are cold-adapted enzymes that exhibit unique sequence specificities diverging from human AID’s classical WRC (W = A/G, R = A/T) sequence preference (24, 25, 52). Given this likelihood of divergent enzymatic properties and having ascertained major differences in their surface charge and pI, the newly identified putative enzymes were tested across a range of conditions, varying incubation temperature, pH, and substrate sequence motifs surrounding the target cytidine (SI Appendix, Fig. S9A). As expected, enzymatic activities could be detected in vitro for human AID (Fig. 3A and SI Appendix, Fig. S9B) and zebrafish AID (SI Appendix, Fig. S9C) with the expected WRC target preference for human AID (TGC and TAC substrates were preferred over CTC, ATC, and TTC substrates) (SI Appendix, Fig. S9 B and C). Cytidine deaminase activities were also recorded for CDA1L1_4 (Fig. 3B and SI Appendix, Fig. S9D), CDA1L1_2 (Fig. 3C and SI Appendix, Fig. S9E), and both variants of CDA1L1_1 (Fig. 3D and SI Appendix, Fig. S9 F and H) and CDA1L1_3 (Fig. 3E and SI Appendix, Fig. S9 G and I), as summarized in Fig. 3F. Notably, CDA1L1_4, the invariant member of the CDA1L1 family, and distinguished by a surface charge distribution comparable to PmCDA1 and human AID, also exhibited cytidine deaminase activity (Fig. 3B and SI Appendix, Fig. S9D). Moreover, as expected from our previous studies (24, 25, 50), all CDA1L1 enzymes appeared to be cold adapted, exhibiting an optimal temperature of 14–22 °C, compared with human AID (optimal temperature of 32–37 °C); the optimal pH varied among the enzymes in a manner that correlated with each variant’s pI and predicted overall surface charge (Fig. 3F). The only variant (CDA1L1_4) which carries a positive charge similar to human AID, preferred a neutral pH, while the other negatively charged variants were active at lower pH conditions (pH 5.9–6.4). To further validate these results, we employed two additional and independent experimental systems for measuring cytidine deaminase activity. First, we used a prokaryotic system (24, 25, 52) to express LpCDA1L1_4 in parallel with PmCDA1. Confirming the aforementioned observations, both proteins exhibited cytidine deaminase activities (Fig. 3G). Second, we employed a rifampicin-resistance assay upon expression of mouse AID, PmCDA1, and LpCDA1L1_4 in Escherichia coli (53). The results shown in Fig. 3H provide independent support for the mutagenic activity of LpCDA1L1_4. Thus, we conclude that the newly identified proteins indeed encode active cytidine deaminases enzymes.

Fig. 3.

Cytidine deamination activity of CDA1L1 variants. (A) Representative alkaline cleavage gel of human AID (Hs-AID) activity using different substrates, each containing the target (d)C in varying nucleotide sequence contexts at various temperatures [results are shown for assay conducted at 37 °C, pH 7.1 (cf. SI Appendix, Fig. S9A, Middle)]. A representative negative control deamination assay using extracts of untransfected 293T cells is shown at Right. (B) Representative alkaline cleavage assay of LpCDA1L1_4. (C–E) Representative alkaline cleavage assays for LpCDA1L1_2, LpCDA1L1_1, and LpCDA1L1_3, the latter two proteins in spliced versions (cf. SI Appendix, Fig. S4). The enzyme assays in B–E were conducted at 22 °C in phosphate buffer (pH 6.4), except for LpCDA1L1_4, which was tested at pH 7.1. (F) Summary table indicating the enzymatic activities of human AID and Lampetra planeri CDA1L1 proteins (cf. SI Appendix, Fig. S9). (G) Representative alkaline cleavage assay gels of LpCDA1L1_4 (Left) and PmCDA1L1 (Middle) purified as N-terminally tagged GST fusion proteins expressed in E. coli. The proteins were incubated at 14 °C with different bubble substrates containing the target (d)C in varying nucleotide sequence contexts, in phosphate buffer (pH 7.1). The Right gel depicts the negative control experiment wherein substrates were incubated with buffer alone and no enzyme, under the same conditions. (H) Mutagenic activities of the mouse AID (MmAID), PmaCDA1, and LpCDA1L1_4 in bacteria containing a mutation in the ung-1 gene that encodes for uracil-DNA glycosylase 1 (UDG1), which prevents repair of deaminase-induced C-to-U DNA transitions. Activity was measured as the number of rifampicin-resistant (RifR) colonies per 109 viable cells (number of ampicillin-resistant colonies) (53). Deaminase activities were evaluated against the vector control using an unpaired Student’s t test with Welch’s correction. ***P < 0.0001, **P < 0.0021. In this assay, LpCDA1L1_1 and _2 also showed significant deaminase activities. Some display items were combined from different parts of the same autoradiographic films; the splice sites are indicated by solid lines.

Discussion

We have identified members of the AID/APOBEC family in jawless vertebrates, including two CDA1-like clades, designated CDA1L1 and CDA1L2. Previous analyses showed that, despite the low sequence identity between them, PmCDA1 and human AID share certain commonalities, namely, the ability to bind DNA substrate with high affinity and catalyze deamination at an unusually slow rate (25). Here, we show that the newly identified proteins of the CDA1L1 subgroup, which are substantially divergent from both PmCDA1 and human AID, sharing no more than ∼26% amino acid sequence identity with either, are active cytidine deaminase enzymes. More detailed biochemical analysis will be necessary to elucidate whether any of the CDA1 variants share the unusual binding affinity and catalytic rates with other AID orthologs (25). Interestingly, unlike other CDA1L1 proteins in lampreys, the CDA1L1_4 protein, encoded by the CDA1L1_4 gene, shares a unique chemical property with PmCDA1 and AID, namely, a high net positive surface charge. This positively charged surface is a feature of AID that distinguishes it from related APOBEC3 proteins, which have neutral or net negative charges (3). We speculate that as in human AID, this highly positive surface charge modulates the efficiency of ssDNA substrate on/off binding kinetics (50), functionally distinguishing CDA1L1_4 from the other CDA1-like proteins.

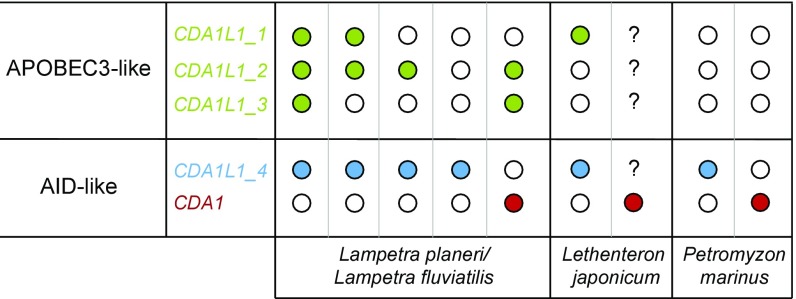

Combined with its cytidine deamination activity, our data are consistent with the evolution of CDA1L1_4 toward a similar DNA editing function in vivo as PmCDA1. Therefore, our findings raise the intriguing possibility that lampreys have found different solutions for VLRA/C assembly; the gene conversion process might be governed by either a canonical CDA1 gene in P. marinus, or by a variant thereof, in L. japonicum and L. planeri or, alternatively, by CDA1L1_4, found to exist in individuals of four lamprey species: P. marinus; L. planeri; L. fluviatilis, and L. japonicum. Of note, so far, CDA1 and CDA1L1_4 genes have not been found in the same individual, indicating a mutually exclusive genetic complement (Fig. 4), although large-scale population surveys are required to determine the frequencies of these genes in different populations.

Fig. 4.

Summary of the genomic configurations of CDA1-related genes in different lamprey species analyzed in this study and schematic representation of unique CDA1 and CDA1-like genotypes in different lamprey species. Each column represents a different animal of that species. Colored dots represent confirmed presence of genes (green, CDA1L1_1, _2, or _3; blue, CDA1L1_4; and red, CDA1); open dots correspond to absent; “?” corresponds to unexplored presence of genes. For details, see SI Appendix, Table S3.

Recent work on the evolution of the AID/APOBEC superfamily suggests that its members initially evolved to serve a role during the development of immune facilities, and that their rapid evolution and expansion was subsequently driven by a host-pathogen arms race (44). In humans, the members of the APOBEC3 subfamily exist within a single chromosomal locus. To varying degrees, each individual APOBEC3 branch member (A3A, A3B, A3C, A3D, A3F, A3G, and A3H) exhibits activity against different viruses, including retroviruses, like HIV (20, 54–57). The copy number variability (CNV) of APOBEC3 clade members from a single copy in mice to up to seven genes in primates, and the striking sequence divergence among primate APBOEC3 orthologs, may have arisen in response to pathogen pressure; indeed, variability in copy numbers also exists among different human populations, with some individuals lacking APOBEC3B (58). Our present analysis indicates that the situation of CDA genes in lampreys is similarly complex. We established that each of the four species analyzed in this study, L. planeri, L. fluviatilis, L. japonicum, and P. marinus possesses one highly conserved ortholog of the CDA2 gene, hinting at nonredundant function(s), which may include assembly of VLRB genes. By contrast, individuals of the four lamprey species exhibit different complements of up to six CDA1-like genes (Figs. 1A and 4). The precise sequences and numbers of these genes differed between species and, remarkably, between individuals of the same species sampled from different locations; however, because our animals were collected over a period of several years, it is not yet possible to establish a correlation between the number of CDA1-like genes and a specific ecological niche.

With respect to CDA1 and CDA1L1_4 genes, one could envisage that lampreys possess both but invariably delete either one during early embryonic development; however, our analysis of the germ-line DNA of the Lj#1 (which exhibits only CDA1L1_4) renders this possibility unlikely. Since lampreys are known to undergo programmed genome rearrangement with loss of up to 20% of their genome (59), it is formally possible that the variable gene numbers of the other members of the CDA1 gene family (Fig. 4) could be due to this phenomenon. However, we believe this possibility is unlikely because programmed gene loss is proposed to primarily target genes important for embryonic development (60, 61); furthermore, comparison of germ-line and somatic genomic sequences provided by an improved genome assembly of the sea lamprey (62) suggests that CDA1-like genes are not subject to programmed gene loss.

Hence, with respect to the evolutionary trajectory of lamprey CDA1-like genes, two major themes emerge. First, all lamprey individuals studied possess a gene encoding a cytidine deaminase with chemical features comparable to the originally described PmCDA1. Analogous to AID, the enzymes encoded by this group of CDA1-like genes are highly positively charged and possibly function in assembly of the VLRA/C loci. These genes thus represent a core component of the genetic network underlying the development of the two T-like cell lineages in lampreys. Second, variable numbers of other CDA1-like genes were also found in lampreys. They appear to be functionally divergent, as illustrated by distinct predicted surface topologies and substantial net negative charge with correspondingly optimal in vitro activity at acidic pH, more akin to APOBEC3A and 3G than AID (48, 49); this property may reflect adaptation to functions in acidic cellular compartments, such as endosomes and may thus be related to antiviral activities. We propose that the presence or absence of these genes in lamprey is analogous to copy number variations observed for APOBEC3 genes in jawed vertebrates and a direct result of distinct kinds of pathogen pressure.

While sharing relatively low sequence homology (around 26%) at the protein level, CDA1L1 genes are most closely related to CDA1 (Fig. 1A). Indeed, both still show the same genetic structure and can encode full-length ORFs in a single exon. Recent analysis has demonstrated that APOBEC3 genes evolved from AID in eutherian animals with subsequent paralog expansions resulting in multiple antiviral APOBEC3 genes (44). One can speculate about a comparable situation in lamprey, wherein CDA1-like genes evolved from CDA1, resulting in a similar paralog expansion that has also produced variable copy numbers of these genes between species and individuals. Further work is required to delineate the range of biological functions of the CDA1 group members in lamprey immunity, for instance with respect to their substrate specificities and the structures of interaction surfaces of viral inhibitors; encouraging preliminary results indicate that it might be possible to generate biallelically mutant animals using the CRISPR/Cas9 methodology (63).

Materials and Methods

Animals.

All animal experiments were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations and were approved by the review committee of the Max Planck Institute of Immunobiology and Epigenetics and the Regierungspräsidium Freiburg, Germany.

WGS.

For DNA extraction, kidney, gills, and intestine were mechanically disrupted; whole bodies were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and ground to powder; blood cells were pelleted by centrifugation. Tissues/cells were proteinase K digested and nucleic acids extracted using phenol-chloroform using standard protocols. RNA was removed with RNase. The final DNA preparations were dissolved in TE buffer and their concentrations measured on a Qbit 3.0 instrument (Invitrogen) and integrity assessed by agarose gel electrophoresis. Sequencing libraries were prepared from a minimum of 500 ng of total genomic DNA using the Illumina TruSeq DNA PCR-Free LT Sample Preparation Kit (FC-121-3001); libraries were sequenced in 2 × 250 bp paired-end mode to a depth of 150 million reads using the rapid mode on an HiSeq2500 instrument (Illumina). The average size of sequenced DNA fragments (∼400–500 bp) allowed us to fuse the paired reads into single contigs.

Generation of BLAST Databases from WGS.

Illumina adapter sequences were trimmed off the read ends using cutadapt in paired-end mode (64). Low-quality bases were removed using prinseq (65) with minimum base quality 20 in a window of three bases with a step size of two bases, retaining reads of at least 30-nt length. For lower quality libraries, window and step size were increased. Reads with mean quality below 26 were removed as appropriate. Forward and reverse mates were merged using flash (66), allowing for up to 300 bases overlap. Spaces in read names were replaced with underscores using the sed command. The resulting merged as well as unmerged read files were formatted into one nucleotide blast database allowing for read name parsing.

CDA Contig Assembly from BLAST Databases.

Genomic sequence collections were searched for CDA-like sequences using the BLASTn algorithm on the SequenceServer BLAST server (version 1.0.9) (67), installed in-house. BLAST parameters were set to an expectation cutoff of 1E−5, allowing a maximum number of 1,000 returned sequences. From the resulting hits, contigs were assembled with SeqMan Pro (version 13.0.0, DNASTAR) using a match size of 25 nucleotides and a minimum match percentage of 99% with otherwise default parameters. Contigs were manually curated and used as queries against the nonredundant National Center for Biotechnology Information protein database using the BLASTx algorithm to identify bona fide CDA-encoding sequences.

Phlyogenetic Comparison of AID/APOBEC Family Members with Lamprey CDAs.

Phylogenetic relationships were derived using an approximate maximum likelihood (ML) method as implemented in the FastTree program (68) and the full ML method implemented in MEGA7 (69). To increase the accuracy of topology in FastTree, we increased the number of rounds of minimum-evolution subtree-prune-regraft (SPR) moves to 4 (-spr 4) as well as utilized the options -mlacc and -slownni to make the maximum-likelihood nearest-neighbor interchanges (NNIs) more exhaustive.

Southern Filter Hybridizations.

Southern filter hybridizations were carried out as described (39). Final wash conditions were 0.1 × SSC/0.1% SDS at 60 °C.

PCR of CDA Genes with Version-Specific Primers.

PCR was carried out on genomic DNA using the proof-reading Phusion polymerase (New England Biolabs) as described (39). CDA1L1 version-specific forward primers (CDA1L1_1, 5′-GTCAGAAATAATCCCTTGGAC-3′; CDA1L1_2, 5′-CAGAAATAATCCCTCGTTCCG-3′; CDA1L1_3, 5′-CTGAAGAAACAGCACAAGCTG-3′; and CDA1L1_4, 5′-GCGGCGAACAATAAAGACAAG-3′) were used with a universal reverse primer (CDA1L1_New_Rev1, 5′-AGGGTTTGTCATGTAAACAGG-3′). Long-range PCR to link CDA1L1 gene bodies to their 3′ exons was carried out using the same forward primers but with a reverse primer designed to anneal to the presumptive 3′-UTRs of the 3′ exons (CDA1L1_ExC_UTR2, 5′-ACAGCTAGACGATCAAACGTTAA-3′) (10-s denaturation at 98 °C, 30-s annealing at 58 °C, 10-min elongation at 72 °C for 35 cycles).

RT-PCR.

Total RNA was extracted using TriReagent (Sigma), treated with RNase-free DNase (Roche) and converted to cDNA using SuperScript II and random hexamer primers, following the manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen). cDNAs were amplified using the CDA1L1 version-specific primers described above, coupled either to one universal reverse primer specific for unspliced products (CDA1L1_New_Rev1, described above) or for the spliced product (LpCDA1L1_r, 5′-GCTTCCTCAGCCCTCAGAACCTG-3′). The actin control was amplified using the following primers: LjActin1 5′-TGAAGTGCGACGTGGACATC-3′ and LjActin4 5′-CAAGAGCCTTCCTGCAACTCTG-3′.

Transcriptome Assembly.

Total RNA was isolated from gills, kidney, intestine, and blood as described above and quality checked using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer to ensure RNA integrity numbers (RIN) greater than 8. RNA-seq libraries were made from 3,000 ng of total RNA using the Illumina TruSeq stranded mRNA library prep kit (RS-122-2101) utilizing polyA selection to enrich for mRNA. Libraries were then amplified for seven cycles. Libraries were sequenced at 2 × 100 bp paired end using HiSeq2500 (Illumina). Trimmomatic (version 0.30) (70), Trim Galore! (version 0.3.3) (www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/trim_galore/), and fastx-toolkit (hannonlab.cshl.edu/fastx_toolkit/) program suites were used to trim adapters and low-quality bases and remove reads that were too short for assembly or had overall low quality. The reads from each organ were combined per individual for de novo transcriptome assembly. We additionally applied in silico fragment normalization to 30× coverage using the normalize_by_kmer_coverage.pl utility from Trinity. The assembly was performed using Trinity (version r20131110) (71) with default settings. The best ORFs were subsequently extracted using the Transdecoder tool from Trinity; ORFs with identical amino acid sequences were collapsed together using CD-Hit (version 4.6.1–2012-08-27) (72). Collections of unique ORFs for each animal were converted into BLAST databases as described above.

RNA-Seq Expression Analysis.

Using the trimmed and processed reads described above as an input, reads were aligned from each organ from L. planeri specimen Lp#131 and Lp#132 against the different CDA gene variants using HiSAT2 (Galaxy version 2.0.5.1) (73) with default parameters and alignments with a quality score of less than 30 filtered out. Read counts per gene were extracted using Samtools IdX Stats and converted to log2 counts per million (log2 cpm).

Expression of CDA Variants.

The newly identified CDA variants were expressed in bacterial and eukaryotic cells as previously described for human and bony fish AID (21, 24, 25, 74). Briefly, for expression in 293T cells, amplicons containing ORFs of CDA variants were obtained and KpnI and EcoRV restriction sites were added to the 5′ and 3′ ends, respectively, of each ORF by PCR, followed by cloning into the expression vector pcDNA3.1/V5-His-TOPO, upstream of the V5 linker and polyhistidine tag. Plasmids that contained correct inserts were verified by restriction analyses and sequencing. Two independent correct expression constructs were carried forward for expression of each CDA variant. As positive controls for enzyme assays, expression vectors containing human AID and zebrafish AID ORFs were constructed in the same manner. To express each CDA variant, purified plasmid from each of the two sister expression constructs was transfected at a concentration of 5 µg per plate into 25 × 10 cm tissue culture plates each containing 5 × 105 HEK293T cells. To prepare for transfection, HEK 293T cells were grown to 50% confluence in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium containing 10% supplemented calf serum, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, and 55 units/mL penicillin and 55 µg/mL streptomycin. The cells were transfected using PolyJet In Vitro DNA Transfection Reagent (SignaGen) diluted in serum-free media and harvested by centrifugation 48 h posttransfection. Protein expression was confirmed by Western blot using a polyclonal rabbit anti-V5 Tag antibody (Abcam). Each cell pellet was suspended in 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 8.2), 500 mM NaCl, 50 µg/mL RNase A, 0.2 mM PMSF, and then lysed using a French press pressure cell (Thermospectronic). The lysate was centrifuged to clear cellular debris and the supernatant was flash frozen. Expression of N-terminally tagged GST-fusion CDA proteins was carried out as previously described for human and bony fish AID (21, 24, 25). ORF sequences encoding each CDA were cloned into the expression vector pGEX5.3 (GE Healthcare) using the EcoR1 site downstream of the GST tag. Expression constructs were verified by restriction analyses and sequencing. E. coli containing each expression vector were induced to express protein with 1 mM IPTG at 16 °C for 16 h. Cells were lysed using the French pressure cell press (Thermospectronic), followed by purification using glutathione sepharose high-performance beads (Amersham) as per manufacturer’s recommendations. GST-CDA proteins were stored in 20 mM Tris⋅HCl pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT.

Cytidine Deamination Enzyme Assays.

To test the activity of CDA variants, we used the standard alkaline cleavage assay for cytidine deamination as previously described for human AID/APOBECs (19, 21, 24, 25, 52). Partially single-stranded substrates containing a target (d)C inside bubble regions of varying sizes and nucleotide sequence contexts surrounding the target (d)C, were used to test for deamination activity. Substrates were prepared as previously described (19, 21, 24, 25, 52). Briefly, polynucleotide kinase (NEB) was used to 5′ label 2.5 pmol of the target strand with [γ-32P] ATP (PerkinElmer), followed by purification by mini-Quick spin DNA columns (Roche) and annealing with threefold excess of the complementary strand to generate bubble substrates.

To determine the activity of the CDA variants and controls, the two independent preparations of each CDA variant were incubated in parallel with human and zebrafish AID positive controls, and untransfected 293T lysate negative controls, with 10–50 fmol radioactively labeled substrates, in 100 mM phosphate buffer pH 6.4 or 7.1, to a final volume of 20 µL, for 1–16 h at temperatures ranging from 14 °C to 37 °C, followed by heat-inactivation at 85 °C for 15 min, uracil excision by uracil-DNA glycosylase (UDG) for 30 min in a final volume of 30 µL, addition of NaOH to a final 180 mM, and heating to 95 °C for 10 min to induce cleavage at the alkali-labile abasic site. Following addition of loading dye and denaturation, electrophoresis was performed on a 14% denaturing acrylamide gel. The gels were exposed to a Kodak Storage Phosphor Screen GP (Bio-Rad) and visualized using a PhosphorImager on Quantity One software (Bio-Rad). Percent deamination of each substrate (d)C was calculated for each CDA variant using Quantity One software (Bio-Rad) and averaged between two independent duplicate preparations of each variant.

Bacterial Resistance Assays.

cDNA sequences corresponding to MmAID, PmCDA1, and LpCDA1L1_4 were cloned into the pTrc99A vector (Pharmacia; a kind gift from Cristina Rada, MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology, Cambridge, UK) using NcoI/HindIII restriction sites and transformed into the ung-1 derivative of the KL16 E. coli strain, BW310 (a kind gift from Cristina Rada). Six independent cultures per construct were grown overnight at 37 °C to saturation in LB medium supplemented with 100 µg/mL ampicillin and 1 mM IPTG. Mutagenic activity is expressed as the number of colony-forming units grown on LB agar plates containing 100 µg/mL rifampicin per 109 viable cells grown on LB agar plates containing 100 µg/mL ampicillin relative to a vector only control as previously described (53).

Structure Prediction of CDA Variants.

For structural modeling and substrate docking, we used the same strategy as previously described for determination of AID’s functional and breathing structure (3, 50), which has since been confirmed by a partial AID crystal structure (51). Briefly, five homologous APOBEC structures were chosen as templates for homology modeling: mouse A2 NMR (PDB: 2RPZ), A3A NMR (PDB: 2M65), A3C (PDB: 3VOW), A3F-CTD X-ray (PDB: 4IOU), and A3G-CTD X-ray (PDB: 3E1U). APOBEC structures were obtained from the Protein Data Bank (www.rcsb.org) and visualized using PyMOL v1.7.6 (https://pymol.org/2/). Using I-TASSER (https://zhanglab.ccmb.med.umich.edu/I-TASSER/), full-length orthologous AID and CDA protein structures were modeled at pH 7 from APOBEC templates to generate 9–25 models for each (variability due to model convergence), for a total of 145 models. Nonhomologous regions between the target and APOBEC template, such as the N and C termini, were modeled ab initio. The catalytic pocket was defined by the solvent accessible cavity containing the Zn-coordinating and catalytic residues. Protein charge and pI were predicted for each protein structure using the PARSE force field in PROPKA 3.0. DNA substrates were docked to each AID or CDA model using Swiss-Dock (www.swissdock.ch). Each substrate was constructed in Marvin Sketch v.5.11.5 (www.chemaxon.com/products/marvin/marvinsketch/), while surface topology and docking parameters were generated using Swiss-Param (swissparam.ch). These output files served as the ligand file in Swiss Dock. The 5′-TTTGCTT-3′ ssDNA substrates were chosen, since the former has been shown to be the preferred substrate of both human and bony fish AID. ssDNA was docked within 30 × 30 × 30 Å (x, y, and z) from the Zn-coordinating histidine in the catalytic pocket. Substrate docking simulations for each AID or CDA enzyme resulted in 5,000–15,000 binding modes, eight or more of which were clustered based on root mean square (rms) values. The 32 lowest-energy clusters were selected, thus representing 256 of the lowest-energy individual binding events within 32 low-energy clusters for each AID or CDA, and these were analyzed in University of California San Francisco Chimera v1.7 (https://www.cgl.ucsf.edu/chimera) (75). Deamination-conducive CDA-DNA complexes were defined by the accessibility of the (d)C-NH2 substrate group to the catalytic Zn-coordinating and the glutamic acid residues within the putative catalytic pockets.

Sequence Deposition.

Whole genome reads (accession nos. SAMN08109814–SAMN08109820) and raw transcriptome reads (accession nos. SAMN08109821–SAMN08109828) were submitted to the Sequence Read Archive at the NCBI. cDNA sequences were submitted to GenBank at the NCBI (accession nos. MG495252–MG495272).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Tamami Hirai for expert technical assistance; Dr. Cristina Rada for reagents; Dr. Max Cooper for insightful discussion of his unpublished data on the CDA gene family in lampreys; and the Experimental Unit of Aquatic Ecology and Ecotoxicology (U3E), Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique 1036, which is part of the research infrastructure Analysis and Experimentations on Ecosystems-France, for help with the provision of animals. S.J.H. and T.B. are supported by the Max Planck Society, the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft through SFB 746, and the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013), ERC Grant agreement 323126. M.L. is supported by a Canadian Cancer Society Research Institute innovation grant and Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) Discovery Grant 2015-047960. E.M.Q. is supported by an NSERC postgraduate doctoral scholarship, and J.J.K. is supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research doctoral fellowship. L.M.I. and L.A. are supported by the NIH and the intramural funds of the National Library of Medicine at the NIH.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data Deposition: The data reported in this paper have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database (accession nos. SAMN08109814–SAMN08109820 and SAMN08109821–SAMN08109828). The sequences reported in this paper have been deposited in the GenBank database (accession nos. MG495252–MG495272).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1720871115/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Conticello SG. The AID/APOBEC family of nucleic acid mutators. Genome Biol. 2008;9:229. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-6-229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iyer LM, Zhang D, Rogozin IB, Aravind L. Evolution of the deaminase fold and multiple origins of eukaryotic editing and mutagenic nucleic acid deaminases from bacterial toxin systems. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:9473–9497. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.King JJ, Larijani M. A novel regulator of activation-induced cytidine deaminase/APOBECs in immunity and cancer: Schrödinger’s CATalytic pocket. Front Immunol. 2017;8:351. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Salter JD, Bennett RP, Smith HC. The APOBEC protein family: United by structure, divergent in function. Trends Biochem Sci. 2016;41:578–594. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2016.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Muramatsu M, et al. Specific expression of activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID), a novel member of the RNA-editing deaminase family in germinal center B cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:18470–18476. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.26.18470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Muramatsu M, et al. Class switch recombination and hypermutation require activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID), a potential RNA editing enzyme. Cell. 2000;102:553–563. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00078-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Revy P, et al. Activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID) deficiency causes the autosomal recessive form of the Hyper-IgM syndrome (HIGM2) Cell. 2000;102:565–575. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00079-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dickerson SK, Market E, Besmer E, Papavasiliou FN. AID mediates hypermutation by deaminating single stranded DNA. J Exp Med. 2003;197:1291–1296. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Honjo T, Muramatsu M, Fagarasan S. AID: How does it aid antibody diversity? Immunity. 2004;20:659–668. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arakawa H, Hauschild J, Buerstedde JM. Requirement of the activation-induced deaminase (AID) gene for immunoglobulin gene conversion. Science. 2002;295:1301–1306. doi: 10.1126/science.1067308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Knight KL, Becker RS. Molecular basis of the allelic inheritance of rabbit immunoglobulin VH allotypes: Implications for the generation of antibody diversity. Cell. 1990;60:963–970. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90344-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sun J, et al. Antibody repertoire development in fetal and neonatal piglets. I. Four VH genes account for 80 percent of VH usage during 84 days of fetal life. J Immunol. 1998;161:5070–5078. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parng CL, Hansal S, Goldsby RA, Osborne BA. Gene conversion contributes to Ig light chain diversity in cattle. J Immunol. 1996;157:5478–5486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Butler JE. Immunoglobulin diversity, B-cell and antibody repertoire development in large farm animals. Rev Sci Tech. 1998;17:43–70. doi: 10.20506/rst.17.1.1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reynaud CA, Anquez V, Grimal H, Weill JC. A hyperconversion mechanism generates the chicken light chain preimmune repertoire. Cell. 1987;48:379–388. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90189-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bransteitter R, Pham P, Scharff MD, Goodman MF. Activation-induced cytidine deaminase deaminates deoxycytidine on single-stranded DNA but requires the action of RNase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:4102–4107. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0730835100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pham P, Bransteitter R, Petruska J, Goodman MF. Processive AID-catalysed cytosine deamination on single-stranded DNA simulates somatic hypermutation. Nature. 2003;424:103–107. doi: 10.1038/nature01760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Larijani M, Frieder D, Basit W, Martin A. The mutation spectrum of purified AID is similar to the mutability index in Ramos cells and in ung(-/-)msh2(-/-) mice. Immunogenetics. 2005;56:840–845. doi: 10.1007/s00251-004-0748-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sohail A, Klapacz J, Samaranayake M, Ullah A, Bhagwat AS. Human activation-induced cytidine deaminase causes transcription-dependent, strand-biased C to U deaminations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:2990–2994. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu Q, et al. APOBEC3B and APOBEC3C are potent inhibitors of simian immunodeficiency virus replication. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:53379–53386. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408802200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Larijani M, Martin A. Single-stranded DNA structure and positional context of the target cytidine determine the enzymatic efficiency of AID. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:8038–8048. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01046-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Larijani M, et al. AID associates with single-stranded DNA with high affinity and a long complex half-life in a sequence-independent manner. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:20–30. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00824-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carpenter MA, Rajagurubandara E, Wijesinghe P, Bhagwat AS. Determinants of sequence-specificity within human AID and APOBEC3G. DNA Repair (Amst) 2010;9:579–587. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2010.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dancyger AM, et al. Differences in the enzymatic efficiency of human and bony fish AID are mediated by a single residue in the C terminus modulating single-stranded DNA binding. FASEB J. 2012;26:1517–1525. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-198135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Quinlan EM, King JJ, Amemiya CT, Hsu E, Larijani M. Biochemical regulatory features of activation-induced cytidine deaminase remain conserved from lampreys to humans. Mol Cell Biol. 2017;37:e00077-17. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00077-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boehm T, et al. VLR-based adaptive immunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2012;30:203–220. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-075038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pancer Z, et al. Somatic diversification of variable lymphocyte receptors in the agnathan sea lamprey. Nature. 2004;430:174–180. doi: 10.1038/nature02740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alder MN, et al. Diversity and function of adaptive immune receptors in a jawless vertebrate. Science. 2005;310:1970–1973. doi: 10.1126/science.1119420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pancer Z, et al. Variable lymphocyte receptors in hagfish. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:9224–9229. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503792102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kasamatsu J, Suzuki T, Ishijima J, Matsuda Y, Kasahara M. Two variable lymphocyte receptor genes of the inshore hagfish are located far apart on the same chromosome. Immunogenetics. 2007;59:329–331. doi: 10.1007/s00251-007-0200-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li J, Das S, Herrin BR, Hirano M, Cooper MD. Definition of a third VLR gene in hagfish. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:15013–15018. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1314540110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kasamatsu J, et al. Identification of a third variable lymphocyte receptor in the lamprey. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:14304–14308. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001910107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hirano M, et al. Evolutionary implications of a third lymphocyte lineage in lampreys. Nature. 2013;501:435–438. doi: 10.1038/nature12467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Das S, et al. Organization of lamprey variable lymphocyte receptor C locus and repertoire development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:6043–6048. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1302500110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Das S, et al. Evolution of two prototypic T cell lineages. Cell Immunol. 2015;296:87–94. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2015.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alder MN, et al. Antibody responses of variable lymphocyte receptors in the lamprey. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:319–327. doi: 10.1038/ni1562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Herrin BR, et al. Structure and specificity of lamprey monoclonal antibodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:2040–2045. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711619105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bajoghli B, et al. A thymus candidate in lampreys. Nature. 2011;470:90–94. doi: 10.1038/nature09655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Holland SJ, et al. Selection of the lamprey VLRC antigen receptor repertoire. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:14834–14839. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1415655111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Das S, et al. Genomic donor cassette sharing during VLRA and VLRC assembly in jawless vertebrates. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:14828–14833. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1415580111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rogozin IB, et al. Evolution and diversification of lamprey antigen receptors: Evidence for involvement of an AID-APOBEC family cytosine deaminase. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:647–656. doi: 10.1038/ni1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nagawa F, et al. Antigen-receptor genes of the agnathan lamprey are assembled by a process involving copy choice. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:206–213. doi: 10.1038/ni1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hirano M. Evolution of vertebrate adaptive immunity: Immune cells and tissues, and AID/APOBEC cytidine deaminases. BioEssays. 2015;37:877–887. doi: 10.1002/bies.201400178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Krishnan A, Iyer LM, Holland SJ, Boehm T, Aravind L. Diversification of AID-APOBEC–like deaminases in metazoa: Identification of clades and widespread roles in immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115:E3201–E3210. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1720897115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mehta TK, et al. Evidence for at least six Hox clusters in the Japanese lamprey (Lethenteron japonicum) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:16044–16049. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1315760110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rougemont Q, et al. Low reproductive isolation and highly variable levels of gene flow reveal limited progress towards speciation between European river and brook lampreys. J Evol Biol. 2015;28:2248–2263. doi: 10.1111/jeb.12750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smith JJ, et al. Sequencing of the sea lamprey (Petromyzon marinus) genome provides insights into vertebrate evolution. Nat Genet. 2013;45:415–421, 421e1-2. doi: 10.1038/ng.2568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Harjes S, et al. Impact of H216 on the DNA binding and catalytic activities of the HIV restriction factor APOBEC3G. J Virol. 2013;87:7008–7014. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03173-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pham P, Landolph A, Mendez C, Li N, Goodman MF. A biochemical analysis linking APOBEC3A to disparate HIV-1 restriction and skin cancer. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:29294–29304. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.504175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.King JJ, et al. Catalytic pocket inaccessibility of activation-induced cytidine deaminase is a safeguard against excessive mutagenic activity. Structure. 2015;23:615–627. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2015.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Qiao Q, et al. AID recognizes structured DNA for class switch recombination. Mol Cell. 2017;67:361–373.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.06.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Abdouni H, et al. Zebrafish AID is capable of deaminating methylated deoxycytidines. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:5457–5468. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Petersen-Mahrt SK, Harris RS, Neuberger MS. AID mutates E. coli suggesting a DNA deamination mechanism for antibody diversification. Nature. 2002;418:99–103. doi: 10.1038/nature00862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang H, et al. The cytidine deaminase CEM15 induces hypermutation in newly synthesized HIV-1 DNA. Nature. 2003;424:94–98. doi: 10.1038/nature01707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chen H, et al. APOBEC3A is a potent inhibitor of adeno-associated virus and retrotransposons. Curr Biol. 2006;16:480–485. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Warren CJ, Westrich JA, Doorslaer KV, Pyeon D. Roles of APOBEC3A and APOBEC3B in human papillomavirus infection and disease progression. Viruses. 2017;9:E233. doi: 10.3390/v9080233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Willems L, Gillet NA. APOBEC3 interference during replication of viral genomes. Viruses. 2015;7:2999–3018. doi: 10.3390/v7062757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kidd JM, Newman TL, Tuzun E, Kaul R, Eichler EE. Population stratification of a common APOBEC gene deletion polymorphism. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e63. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Smith JJ, Antonacci F, Eichler EE, Amemiya CT. Programmed loss of millions of base pairs from a vertebrate genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:11212–11217. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902358106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bryant SA, Herdy JR, Amemiya CT, Smith JJ. Characterization of somatically-eliminated genes during development of the sea lamprey (Petromyzon marinus) Mol Biol Evol. 2016;33:2337–2344. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Timoshevskiy VA, Lampman RT, Hess JE, Porter LL, Smith JJ. Deep ancestry of programmed genome rearrangement in lampreys. Dev Biol. 2017;429:31–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2017.06.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Smith JJ, et al. The sea lamprey germline genome provides insights into programmed genome rearrangement and vertebrate evolution. Nat Genet. 2018;50:270–277. doi: 10.1038/s41588-017-0036-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Square T, et al. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated mutagenesis in the sea lamprey Petromyzon marinus: A powerful tool for understanding ancestral gene functions in vertebrates. Development. 2015;142:4180–4187. doi: 10.1242/dev.125609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Martin M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnetJ. 2011;17:10. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Schmieder R, Edwards R. Quality control and preprocessing of metagenomic datasets. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:863–864. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Magoč T, Salzberg SL. FLASH: Fast length adjustment of short reads to improve genome assemblies. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:2957–2963. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Priyam A, et al. 2015. Sequenceserver: A modern graphical user interface for custom BLAST databases. bioRxiv:10.1101/033142.

- 68.Price MN, Dehal PS, Arkin AP. FastTree 2–Approximately maximum-likelihood trees for large alignments. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9490. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. MEGA7: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol. 2016;33:1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Grabherr MG, et al. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-seq data without a reference genome. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:644–652. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Li W, Godzik A. Cd-hit: A fast program for clustering and comparing large sets of protein or nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:1658–1659. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kim D, Langmead B, Salzberg SL. HISAT: A fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat Methods. 2015;12:357–360. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Abdouni HS, et al. DNA/RNA hybrid substrates modulate the catalytic activity of purified AID. Mol Immunol. 2018;93:94–106. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2017.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pettersen EF, et al. UCSF Chimera–A visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem. 2004;25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kimura M. A simple method for estimating evolutionary rates of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. J Mol Evol. 1980;16:111–120. doi: 10.1007/BF01731581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.