Significance

We demonstrate that the initial spread of farming outside of the area of its first appearance in the Fertile Crescent of Southwest Asia, into Central Anatolia, involved adoption of cultivars by indigenous foragers and contemporary experimentation in animal herding of local species. This represents a rare clear-cut instance of forager adoption and sustained low-level food production. We have also demonstrated that farming uptake was not uniform, with some forager communities rejecting it despite proximity to early farming communities. We also show that adoption of small-scale cultivation could still have significant social consequences for the communities concerned. The evidence suggests forager adoption of cultivation and initiation of herding was not necessarily motivated by simple economic concerns of increasing levels of food production and security.

Keywords: Neolithic, spread of farming, early herding, Anatolia, low-level food production

Abstract

This paper explores the explanations for, and consequences of, the early appearance of food production outside the Fertile Crescent of Southwest Asia, where it originated in the 10th/9th millennia cal BC. We present evidence that cultivation appeared in Central Anatolia through adoption by indigenous foragers in the mid ninth millennium cal BC, but also demonstrate that uptake was not uniform, and that some communities chose to actively disregard cultivation. Adoption of cultivation was accompanied by experimentation with sheep/goat herding in a system of low-level food production that was integrated into foraging practices rather than used to replace them. Furthermore, rather than being a short-lived transitional state, low-level food production formed part of a subsistence strategy that lasted for several centuries, although its adoption had significant long-term social consequences for the adopting community at Boncuklu. Material continuities suggest that Boncuklu’s community was ancestral to that seen at the much larger settlement of Çatalhöyük East from 7100 cal BC, by which time a modest involvement with food production had been transformed into a major commitment to mixed farming, allowing the sustenance of a very large sedentary community. This evidence from Central Anatolia illustrates that polarized positions explaining the early spread of farming, opposing indigenous adoption to farmer colonization, are unsuited to understanding local sequences of subsistence and related social change. We go beyond identifying the mechanisms for the spread of farming by investigating the shorter- and longer-term implications of rejecting or adopting farming practices.

From its emergence in the 10th and 9th millennia cal BC in the Fertile Crescent of Southwest Asia (1, 2), agriculture increasingly dominated subsistence practices across western Eurasia and supplanted foraging as the primary means of food acquisition for many human communities. How and why the Southwest Asian form of agriculture expanded beyond its area of origin has been the subject of debate for decades. As with other instances of the spread of farming, two explanations traditionally dominated discussions: namely, that cultivation and herding was spread by colonizing agriculturalists (the demic diffusion model) (3, 4), or that these practices were adopted by foragers after contact with agriculturalists (5). Moving beyond the polarized positions offered by these explanations, recent critiques have suggested that a more fluid and variable pattern of change may have occurred during the adoption of food production (6). In practice, these critiques have not generally broken down the widespread classic forager–agriculturalist analytical dichotomies (7) attested to in much of the literature on the spread of farming, probably because they have not been evidenced through the compilation of detailed local-scale archaeological and paleoenvironmental histories.

A key region for testing our understanding of the economic, social, and cultural history of food production, as it spread, is the high-altitude Central Anatolian plateau, which has some of the earliest evidence for the development of sedentary and agricultural societies beyond the Fertile Crescent. Often attributed to demic diffusion, an understanding of how agriculture spread into Central Anatolia, as in many regions, has been obscured by a lack of detailed local-scale archaeological and paleoenvironmental histories in which the relationships between social and economic change can be closely investigated through time. This paper presents an analysis of a wide range of evidence, from the sites of Pınarbaşı and Boncuklu, for the first appearance of agriculture in the second half of the ninth millennium cal BC in the Konya Plain of Central Anatolia. As a result of the work of our projects reported herein, the settlement record of Central Anatolia now stretches from the Epipaleolithic into the early Holocene and is thus contemporary with the Levantine Natufian and earlier Aceramic Neolithic [Prepottery Neolithic A (PPNA), early and middle PPNB]. Recent work has shown there is evidence for a significant degree of cultivation and caprine herding before 8000 cal BC at Aşıklı Höyük in Cappadocia (8, 9), and large-scale mixed farming—that is, the integrated cultivation and herding of fully domestic cereals, legumes, and caprines—by at least 7100 cal BC on the Konya Plain at Çatalhöyük East (10). The evidence presented herein, covering the early part of the early Holocene from approximately 9800–7800 cal BC, provides insights into the context, origins, and outcomes of the appearance of agriculture in the region, questioning the dominant view that the spread of cultivation in areas beyond the Fertile Crescent resulted from colonization by migrant farming communities. As well as providing an archaeological example of the spread of agriculture in prehistory through social interactions, the paper also aims to explore the social and cultural consequences of the decision to adopt or reject farming for Anatolia’s early Holocene communities.

Background

As in other geographical areas, interpretations of how agriculture—here defined broadly as the cultivation of plants and herding of animals—spread onto the Anatolian plateau have been dominated by two polarized positions. One posits that cultivation and herding spread into the region with farmers, possibly as part of a Neolithic demographic transition, in which growing population in successful farming regions pushed some people to colonize new areas and regions (3). This claim has been most clearly expressed for Central Anatolia by research that used the similarity of Central Anatolian Neolithic crop and weed seed packages to those from northern Syria to suggest the introduction of cultivation by colonizing farmers from that region (11). While these similarities, as with evidence for obsidian distributions, point to meaningful interactions between settlements across these regions, they do not themselves identify the mechanism by which the crops spread. Rather, they demonstrate a possible point of origin from which they might well have diffused by other mechanisms, including exchange, well evidenced at these periods.

Opposing approaches propose that foragers were responsible for the spread of agriculture by adopting it from farmers with whom they were in contact. In Central Anatolia material culture continuity with the Epipaleolithic combined with borrowed features from the PPNB (approximately 8500–7000 cal BC) of the Levant have been used to identify local indigenous contributions to the development of animal husbandry at Aşıklı (8). Adoptionist models have been best developed in Europe (5, 6, 12), with the most detailed seeing a long “availability” phase of several centuries at the forager–farmer “frontier zone,” giving way to a competitive and, therefore, unstable “substitution” phase, where crops and animals were incorporated into food acquisition practices on a small-scale basis, and then a “consolidation” phase of larger-scale agricultural production (6, 12). Rapid uptake of agriculture during the substitution phase—in effect an unstable transition point—is a key element of this model, separating distinct phases of foraging and farming that are considered economically and socially incompatible (12).

In recent years these polarized interpretations have been modified to admit more overlap: colonization proponents suggesting the possibility of small-scale forager adoption and assimilation within the context of broader colonizing processes, and adoption models, including options for the small-scale movement of some farmers as part of the transfer processes of farming practice (5). Despite this narrowing of the gap between extremes, most accounts still envisage broad processes at either end of a possible spectrum, with significant regions representing one broad process or another (3–5, 10, 13).

Such dichotomous thinking is largely a product of fundamentally different a priori understanding of foragers and small-scale early farming communities. At the heart of colonizer models is an understanding that foragers would not find cultivation or herding attractive prospects (3, 4), with limited time invested in subsistence pursuits, and practices, such as residential mobility and generalized reciprocity, militating against the adoption of cultivation (14, 15). Furthermore, transmission of knowledge about agricultural species, practices, and management might have faced social barriers, relying on long-term observation and close interpersonal communication that would have been easier within rather than between communities (4). However, recent ethnographic work has raised significant challenges to these assumptions, suggesting less uniformity and more flexibility in many forager practices, including time invested in subsistence activities, generalized reciprocity, social practice, and degrees of mobility (16–18). Dichotomous models ultimately present a narrow range of possibilities for the spread of agriculture in prehistory based on a shallow historical understanding of foragers and farmers, often drawn from recent colonial experiences. It is very likely that the social practices, behaviors, identities, and world-views of foragers and farmers of the late Pleistocene and early Holocene were quite different from societies encountered over the past 500 y (1, 19, 20).

The Sites, Their Landscapes, and Chronology

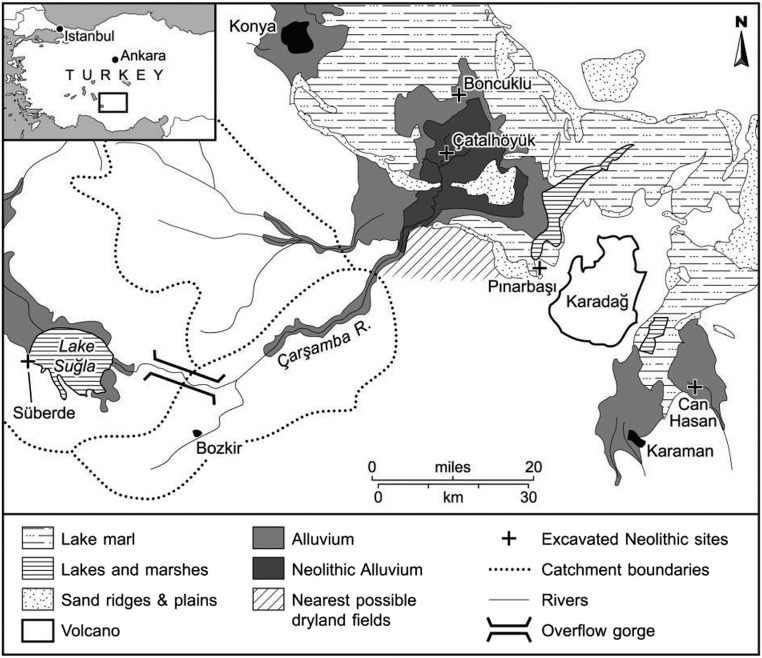

We address the issue of agricultural transition in Central Anatolia using archaeological evidence from the excavation of two settlements in Turkey’s Konya plain. Pınarbaşı (21) is located on the eastern edge of the southwest Konya basin (Fig. 1), with the 10th/9th millennium cal BC settlement mound located a few tens of meters away from the Epipaleolithic and Late Neolithic rockshelter (22). Boncuklu (23) is located 31 km to the northwest, in the center of the same basin, 9.5 km northeast of Çatalhöyük East (Fig. 1). Both settlements are approximately 1 ha in area (SI Appendix, Figs. S1 and S4) and consist of suboval domestic buildings—at Pınarbaşı with wattle and daub superstructures (21), and at Boncuklu with mudbrick superstructures (23)—in both cases interspersed with open spaces. In contrast, the later site of Çatalhöyük East is a much larger mound of 13 ha in area, with densely packed rectangular mudbrick houses (10, 24, 25).

Fig. 1.

Map of central Anatolia showing the principal sites mentioned in the text.

Accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) radiocarbon dating of a total of 16 short-life samples from Pınarbaşı, including those from in situ contexts, such as burials and floors, combined with Bayesian analysis of site sequences provide a site chronology (SI Appendix, SI Text 1). This analysis indicates that occupation in Area D, one of the two trenches excavated into the early Holocene settlement mound, started at or just after the Pleistocene/Holocene transition, around 9800–9400 cal BC (SI Appendix, Figs. S1 and S2 and Table S2), with earlier phases of occupation in Area A (SI Appendix, Fig. S1) dated from around 9000 cal BC (SI Appendix, Table S1), although this does not date the beginning of the sequence in Area A. In both excavation areas, occupation appears to have continued through the ninth millennium cal BC, ending between 8200 and 7800 cal BC (SI Appendix, Figs. S2 and S3). Bayesian analysis of the stratigraphic sequence (SI Appendix, SI Text 1, Fig. S3, and Table S1) indicates that the site occupation ended around 8000 cal BC, although a date from context ADK, in a long-lasting final phase of deposition, suggests occupation may well have continued into the early eighth millennium (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). Thus, the sequence chronologically spans much of the Levantine PPNA and early to middle PPNB, during which agriculture first emerges in the Fertile Crescent.

Bayesian analysis of the Boncuklu sequence of C14 dates, derived from nine short-life seed and nut remains and in situ human burials from Area H (SI Appendix, Figs. S4 and S5), suggests an early settlement phase of approximately 8300–8100 cal BC and a later phase of approximately 8100–7800 cal BC (SI Appendix, SI Text 1, Fig. S5, and Table S3) from those preserved occupation deposits that have been the focus of excavation to date. Chipped stone points in the latest levels, similar to Musular (approximately 7600–7000 cal BC) (26), Canhasan III (approximately 7400–7100 cal BC), and early Çatalhöyük (approximately 7100–7000 cal BC) (27), suggest occupation after 7600 cal BC, although we have not yet located reliable in situ dating samples from those latest contexts.

These results confirm that the early phases at Pınarbaşı form the earliest dated Holocene settlement in Central Anatolia, predating the settlement at Boncuklu by approximately 1,200 y. The two sites were contemporary settlements for at least 300–500 y, and Boncuklu continued to be occupied for a few centuries after Pınarbaşı. Both sites are at least partially contemporary with levels 4 and 3 at Aşıklı in Cappadocia and Pınarbaşı is probably earlier than and contemporary with Aşıklı level 5 (8, 9).

Abundant off-site geomorphological evidence (28) and on-site archaeological data point to the presence of a wetland steppe mosaic on the plain in the early Holocene, including streams, lakes, and wetlands, some located close to both sites. Boncuklu’s anthracological assemblage records a wide diversity of taxa, despite the overall low density of wood charcoal macroremains, dominated by wetland/riparian plants, such as willow/poplar, that comprise 64–71% of the sample ref. 29, table 1. Seed data (SI Appendix, SI Text 2 and Tables S4 and S5) also show a high abundance of wetland species, including indicators of open water and marsh/riparian habitats, as do the phytoliths, which are dominated by reed forms (SI Appendix, SI Text 3 and Fig. S9). Combined with faunal evidence for large mammals, whose habitats include marshy conditions (SI Appendix, SI Text 4), fish, and waterfowl, these data indicate the presence of extensive wetland areas around Boncuklu and overwhelmingly demonstrate the significance of wetland exploitation for the community. Regular, but lower frequency, exploitation of the semiarid woodland of almond, terebinth, and oak, located on the hills and their fringes on the edge of the plain, is indicated by anthracological (29), seed, and faunal data (SI Appendix, SI Texts 1–3).

Table 1.

Summary of plant macrofossil data (NISP sum and % frequency of key macrofossil classes from Boncuklu and trenches at Pınarbaşı)

| Key plant classes | Site | |||||||

| Boncuklu | Pınarbaşı D | Pınarbaşı Late A | Pınarbaşı Early A | |||||

| Contexts analyzed | 45 | 8 | 19 | 13 | ||||

| Sample volume | 3,184 | 473 | 1,499 | 675 | ||||

| NISP, sum (% frequency) | ||||||||

| Total | 36,060 | (100.00%) | 1,071 | (100.00%) | 3,408 | (100.00%) | 2,381 | (100.00%) |

| Cereal grain | 38 | (0.11%) | 0 | (0.00%) | 0 | (0.00%) | 0 | (0.00%) |

| Cereal chaff | 31 | (0.09%) | 0 | (0.00%) | 0 | (0.00%) | 0 | (0.00%) |

| Pulses | 307 | (0.85%) | 0 | (0.00%) | 0 | (0.00%) | 0 | (0.00%) |

| Nutshell (charred) | 257 | (0.71%) | 328 | (30.63%) | 1,329 | (39.00%) | 281 | (11.80%) |

| Nutshell (not charred) | 346 | (0.96%) | 22 | (2.05%) | 70 | (2.05%) | 139 | (5.84%) |

| Wild seeds (charred) | 29,390 | (81.50%) | 109 | (10.18%) | 747 | (21.92%) | 265 | (11.13%) |

| Wild seeds (not charred) | 5,691 | (15.78%) | 612 | (57.14%) | 1,262 | (37.03%) | 1,696 | (71.23%) |

For full data see SI Appendix, Table S4.

While wetland plant exploitation is evidenced at Pınarbaşı, the plant record is dominated by almond and other species indicative of semiarid steppe woodland (30, 31), indicating a greater exploitation of the hill zone for fuel and structural wood than at Boncuklu. The Pınarbaşı faunal assemblage (SI Appendix, SI Text 4) shows the exploitation of animals from hill, wetland, and steppe environments. Several Pınarbaşı datasets, therefore, suggest a relatively balanced exploitation of plain and hill resources, reflecting the ecotonal location of Pınarbaşı in contrast to that of Boncuklu, which is more wetland focused.

Plant Exploitation

Archaeobotanical sampling at Pınarbaşı (30) and Boncuklu (SI Appendix, SI Text 2 and Table S4) demonstrates that the two settlements had differing plant-based subsistence practices (Tables 1 and 2). Both saw the collection of almonds, terebinth nuts, and hackberry fruits, with a focus on almond exploitation at Pınarbaşı (30), perhaps reflecting the proximity of the site to almond-rich woodland on the Karadağ (29, 31). Nuts form a common element of the assemblage at Boncuklu alongside clubrush (Bolboschoenous glaucus) tubers (Tables 1 and 2 and SI Appendix, Tables S4 and S5), perhaps indicating a local adaptation to an abundance of these resources, also found at Çatalhöyük East. There is currently no clear evidence for the collection and processing of wild plant seeds at Pınarbaşı, where the main species present are unlikely foods (30). Boncuklu’s seed assemblage is extremely rich and dominated by a range of wetland plant seeds (SI Appendix, SI Text 2 and Tables S4 and S5), several of which (B. glaucus, docks, and knotweeds) have been identified as food species in contemporary sites in other regions (32). While use of these seeds for food is possible, other explanations are plausible, including the introduction of seeds to the site as part of the reed fuel load evidenced in macrofossil (SI Appendix, SI Text 2, Fig. S6, and Table S4) and microfossil assemblages (SI Appendix, SI Text 3 and Fig. S9). Several wetland plant species also have a high, significant correlation with cultivars, suggesting that some may have arrived as cultivation weeds (SI Appendix, SI Text 2 and Table S5).

Table 2.

Standardized counts, ubiquity, and % frequency of the probable crops at Boncuklu

| Taxon | English name | Component | Sum | Ubiquity | % Frequency |

| Cereals | |||||

| Triticum dicoccum and/or T. dicoccoides | Wild emmer wheat | Grain MNI | 6 | 3 | 6.7 |

| Triticum monococcum and/or T. boeoticum | Wild einkorn wheat | Grain MNI | 9 | 6 | 13.3 |

| Triticum monococcum or T. dicoccum | Wild einkorn or wild emmer | Grain MNI | 2 | 1 | 2.2 |

| Triticum spp. | Wheat | Grain MNI | 3 | 3 | 6.7 |

| Cereal indeterminate | Grain MNI | 6 | 6 | 13.3 | |

| Triticum dicoccum and/or T. dicoccoides | Wild emmer wheat | Glume base | 13 | 4 | 8.9 |

| Triticum monococcum and/or T. boeoticum | Wild einkorn wheat | Glume base | 6 | 4 | 8.9 |

| Triticum monococcum or T. dicoccum | Wild einkorn or wild emmer | Glume base | 10 | 6 | 13.3 |

| Triticum “New type” | “New Type” wheat | Glume base | 2 | 1 | 2.2 |

| Triticum spp. | Wheat | Glume base | 5 | 2 | 4.4 |

| Legumes | |||||

| Pisum sp. | Pea | Seed MNI | 8 | 2 | 4.4 |

| Lens culinaris | Lentil | Seed MNI | 1 | 1 | 2.2 |

| Viceae spp. large-seeded | Legume | Seed MNI | 72 | 21 | 46.7 |

For full data see SI Appendix, Table S4.

A fundamental difference between the sites is in the evidence for cultivation: 10th–9th millennium Pınarbaşı shows no evidence for the cultivation or gathering of cereals and legumes (Tables 1 and 2): the few crop remains in 10th/9th millennium deposits were intrusive, the typical range of weeds associated with cultivation for this period were lacking, and abundant phytoliths showed no evidence for the presence of wheat and barley (30). Boncuklu shows sparse, yet well-dated and compelling evidence for the presence of cereals, legumes, and their weeds in the seed (Tables 1 and 2 and SI Appendix, SI Text 2 and Table S4) and phytolith assemblages (SI Appendix, SI Text 3 and Fig. S9). At Boncuklu, probable crop seeds and chaff form 1.1% of the archaeobotanical assemblage (Tables 1 and 2 and SI Appendix, Table S4), being present in approximately 50% of the analyzed contexts. All of the crop remains were poorly preserved but the grains and chaff of emmer and einkorn wheat were identified plus two “new type” wheat spikelet forks, among the earliest known in southwest Asia (Tables 1 and 2). Wild einkorn and probable wild-type emmer grains were present, as well as several large emmer grains (SI Appendix, SI Text 2 and Fig. S7B) typical of cultivated types (for definition, see SI Appendix, SI Text 2). Most chaff was too damaged for unambiguous distinction of wild/domestic status, although two nonbasal emmer spikelet forks preserved undamaged domestic-type rachis scars present (SI Appendix, SI Text 2). Direct AMS dating has confirmed the age of emmer and einkorn chaff, demonstrating that they are not intrusive from later uses of the site. Phytoliths, trapped in a reed leaf mat on a building floor, confirmed the in situ presence of wheat. Cultivated barley and its wild relatives are lacking, with barley phytoliths probably from the small seeded weedy barley species that are found in the macrofossil assemblages (SI Appendix, SI Texts 2 and 3). AMS dates confirmed that the naked wheat and hulled barley remains reported earlier (23) were contaminants from recent occupation. Also present is lentil and pea (Tables 1 and 2), the latter including a small number with rough (wild-type) and smooth (domestic-type) testas preserved among a range of other large-seeded legumes.

The presence of wheat chaff macrofossils and phytoliths, plus the seeds of several agricultural weeds (SI Appendix, SI Text 2 and Tables S4 and S5) found commonly in other early farming sites (24, 33), suggests that crops were cultivated and processed at Boncuklu. Several probable weeds have strong correlation coefficient values with legume and cereal remains (SI Appendix, SI Text 2 and Table S5), among them wet-loving species whose presence, with the dominance of multicell cereal phytoliths (SI Appendix, SI Text 3), suggest that some crops were grown in relatively well-watered conditions, such as those that would have been located close to Boncuklu.

In overall composition the economic seed assemblage is very similar to those from contemporary sites in southeast Anatolia and the eastern Fertile Crescent, with a small amount of cereals and legumes, with legumes most abundant, used alongside a range of possible foraged wild foods (2, 32, 34, 35). Cropping is far less visible at Boncuklu (1.1% of the assemblage and 50% ubiquity) than in the partially contemporary occupation at Aşıklı level 2, where crops form 70% of the assemblage and were present in approximately 80% of samples (36, 37). A contrast can also be drawn at Çatalhöyük East, whose early assemblages (Mellaart Pre-Level XII) are similar to those from Boncuklu, having many wetland plant seeds and little wood, where crops form approximately 35% of the assemblage and are present in 100% of samples (25, 38). The low frequency of crops in an otherwise abundant plant assemblage suggests that cultivated plants were used and processed in modest quantities at Boncuklu. This is also supported by material culture evidence. Rare bone sickle hafts and two flint sickle blades hint at some plant reaping at Boncuklu, but obsidian microwear studies have yet to identify obsidian sickle blades and extensive archaeobotanical evidence for the use of reeds and sedges suggest potential alternative purposes for those few sickle tools we have identified. In addition, there are no built in situ storage bins or likely storage pits in Boncuklu’s buildings, such as at later Çatalhöyük, and possible storage bins/pits are also uncommon outside buildings, suggesting plant food storage was modest in scale, perhaps mostly in baskets or bags. While grinding stones are present, the site lacks the larger grinders, mortars, and pestles seen at Pınarbaşı which could also have performed other functions, such as grinding ochre and organic tools.

Dietary evidence adds to this picture. Human skeletons have few dental caries, consistent with the limited use of sticky carbohydrate-rich cereal grains in the diet. However, diet spacing between humans and the main meat animals at the sites shown by C and N stable isotopes (SI Appendix, SI Text 6) suggests plant consumption was more important in the Holocene compared with the Late Glacial, contrasting the values from Boncuklu and 10th/9th millennium Pınarbaşı with those from the Epipaleolithic occupation at Pınarbaşı (Table 3). Isotopic evidence shows that plant protein consumption at Boncuklu was similar to the levels found at Çatalhöyük East, but values at both are lower than 10th/9th millennium Pınarbaşı, indicating that plant protein was a higher dietary component at the latter site (SI Appendix, SI Text 6). An obvious source for this is the protein-rich wild almonds that dominated the botanical assemblages there (Tables 1 and 2), and were probably processed on the numerous, large ground stone tools at Pınarbaşı. This evidence confirms the significance of nut/fruit exploitation as a distinctive contribution to the development of early sedentary behavior on the Anatolian plateau compared with the Levant (21, 33). It also demonstrates dietary differences with contemporary Boncuklu, perhaps caused by consumption of fewer fruits/nuts and greater focus on cereals, legumes, low protein tubers, and wild plant seeds in the diet, as indicated in the macrofossil remains.

Table 3.

Nitrogen stable isotope values of samples from human and faunal remains with diet spacing (Δ15N) compared between Pınarbaşı (Epipaleolithic and ninth millennium cal BC), Boncuklu and Çatalhöyük

| Species or taxon | Pınarbaşı Epipaleolithic δ15N ‰ | Δ15N diet-human | Pınarbaşı ninth millenium cal BC δ15N ‰ | Δ15N diet-human | Boncuklu Höyük δ15N ‰ | Δ15N diet-human | Çatalhöyük δ15N ‰ | Δ15N diet-human |

| Humans | 14.8 (n = 2) | — | 11.8 (n = 4) | — | 12.3 (n = 12) | — | 12.7 (n = 68) | — |

| Bos sp. | 9.4 (n = 2) | 5.4 | 9.8 (n = 5) | 2.0 | 9.3 (n = 24) | 3 | 9.8 (n = 79) | 2.9 |

| Sus sp. | — | — | — | — | 7.4 (n = 7) | 4.9 | 8.0 (n = 28) | 4.7 |

| Caprines | 7.1 (n = 22) | 7.7 | 7 (n = 10) | 4.8 | 9.6 (n = 6) | 2.7 | 9.6 (n = 176) | 3 |

Animal Exploitation

At 10th/9th millennium Pınarbaşı, the hunting of large wild mammals, wild aurochsen especially, dominate the prey spectrum [approximately 34% number of identified specimens (NISP)] (Table 4 and SI Appendix, SI Text 4) and certainly meat consumption. Sheep and goat are present in relatively high proportions (27% combined) (Table 4), but still lower than at earlier Epipaleolithic Pınarbaşı (14th–12th millennia cal BC) (22): morphometric analysis is on-going so the domestic/wild status based on morphology is not yet clear. Equids and wild boar have lower representation (7% and 6%, respectively) (Table 4 and SI Appendix, SI Text 4). Fowling and fishing took place, but not as commonly as at earlier Epipaleolithic Pınarbaşı or at Boncuklu. Migrant birds were better represented than those that only breed in Central Anatolia, suggesting that fowling targeted aggregated migrating flocks. C and N stable isotope evidence also suggests that the animal protein contribution to Pınarbaşı 10th/9th millennium human diets may well have been lower than at either Boncuklu or Çatalhöyük (Table 3 and SI Appendix, SI Text 6).

Table 4.

The relative proportions of mammalian taxa (Lepus/hare size and larger) at Pınarbaşı and Boncuklu, expressed as NISP and NISP%

| Pınarbaşı | Boncuklu | ||||

| Taxon | English name | NISP | NISP % | NISP | NISP % |

| Bos primigenius | Aurochs | 92 | 34 | 169 | 31 |

| Equus sp. | Equid | 18 | 7 | 46 | 9 |

| Large cervid | Deer | 3 | 1 | 5 | 1 |

| Dama dama | Fallow deer | 0 | 0 | 12 | 2 |

| Sus scrofa | Pig | 16 | 6 | 258 | 48 |

| Ovis/Capra | Sheep/goat | 53 | 20 | 13 | 2 |

| Ovis sp. | Sheep | 17 | 6 | 3 | 1 |

| Capra sp. | Goat | 2 | 1 | 4 | 1 |

| Castor fiber | Beaver | 1 | <1 | 0 | 0 |

| Canis sp. | Wolf/dog | 0 | 0 | 12 | 2 |

| Vulpes vulpes | Red fox | 56 | 21 | 13 | 2 |

| Lepus europeaus | European hare | 12 | 4 | 4 | 1 |

| Total | 270 | 100 | 539 | 100 | |

Boncuklu also sees a high representation of wild cattle (Table 4), which would have dominated in terms of meat-yield. Numerically, however, the bones of wild boar (Sus scrofa) are most common (45%) (Table 4), contrasting with Pınarbaşı. Both Boncuklu and Pınarbaşı were close to lake and marsh areas, so the high degree of difference in Sus exploitation is unlikely to relate only to environmental factors. Rather, for example, it may reflect attempts by Boncuklu’s farmers to control wild boar numbers, since these animals are notorious crop robbers. As with plant exploitation, divergent hunting practices are seen between these two sites. Sheep and goat representation is another point of difference: the Boncuklu assemblage shows very infrequent presence (Table 4), while their wild/domestic status is uncertain on morphometric grounds. Fowling and fishing are well represented in the Boncuklu fauna, underlining the wetland focus of animal exploitation there. The human C and N stable isotope data from Boncuklu supports higher animal protein contribution to diet, notably from aurochsen and boar (Table 3 and SI Appendix, SI Text 6), with the addition of significant wetland resources, such as fish and water birds, relative to 10th/9th millennium Pınarbaşı.

Study of the caprine C and N stable isotopes from Pınarbaşı (SI Appendix, SI Text 5) indicates that the diet of the 10th/9th millennium cal BC caprines was very similar to that of the Epipaleolithic caprines (SI Appendix, Fig. S10). These caprine isotope values contrast with the higher N and varied C3 and C4 plant diet of the morphologically domestic seventh millennium cal BC caprines from Çatalhöyük and Pınarbaşı (SI Appendix, Fig. S10). Given the similarities between Epipaleolithic and early Holocene caprine diets, it is unlikely that the caprines of 10th/9th millennia Pınarbaşı were being managed by humans: the probability is that all caprines were hunted. At Boncuklu, however, although some of the caprines have a similar dietary signature to those found at early Pınarbaşı, three of the six caprine bones analyzed have higher N, two dramatically higher (SI Appendix, Fig. S11), similar to the later caprines from Çatalhöyük East and West; it is likely that this reflects a diet of marsh, saline and steppe adapted plants, such as might be found on the plain, rather than the classic caprine habitat of the surrounding hills (SI Appendix, SI Text 6). It may also reflect stress in these animals consequent upon management (SI Appendix, SI Text 6). This isotope evidence, along with the presence of a modest amount of herbivore dung on site at Boncuklu, apparently used as fuel and represented by spherulites in soil micromorphological thin-sections, raises the possibility of small-scale experimentation with caprine herding close to the site (SI Appendix, SI Text 4). The scale of this activity and its dietary contribution is likely to have been very small indeed, given the faunal assemblage at Boncuklu contains only approximately 4% NISP of caprines (Table 4).

Invention, Migration, or Adoption of Farming on the Konya Plain?

This evidence allows us to consider the way in which cultivation and herding arrived in the Konya Plain by 8300 cal BC. While possible, the local development of cultivation seems unlikely as Central Anatolia is outside the historic and recent wild distribution range of several of those cultivars found at Boncuklu, including wild emmer wheat and lentil. While einkorn has been considered a possible local domesticate, there is no evidence it was present in Central Anatolia in the Late Glacial or early Holocene in the wild, being absent from Epipaleolithic (22) and earlier 10th/9th millennium Pınarbaşı (30). More probable is that the hulled cereals were introduced to the site, and indeed Central Anatolia as a whole, alongside pea and lentil, from those areas in which cultivation was established earlier (2, 33, 35, 39). Even if locally present, Boncuklu’s location—in a wetland area on the plain—is some distance from the habitats in which wild cereals would have grown naturally, suggesting local incipient cultivation is unlikely. The situation for small-scale animal husbandry is less clear-cut but seems highly likely. Boncuklu is >15 km from the hills in which wild sheep and goat were found and it is possible that local animals were brought into management on the plain from there. An alternative, although one that would be difficult to identify, is that herded stock, like cultivars, were introduced to the site from other regions.

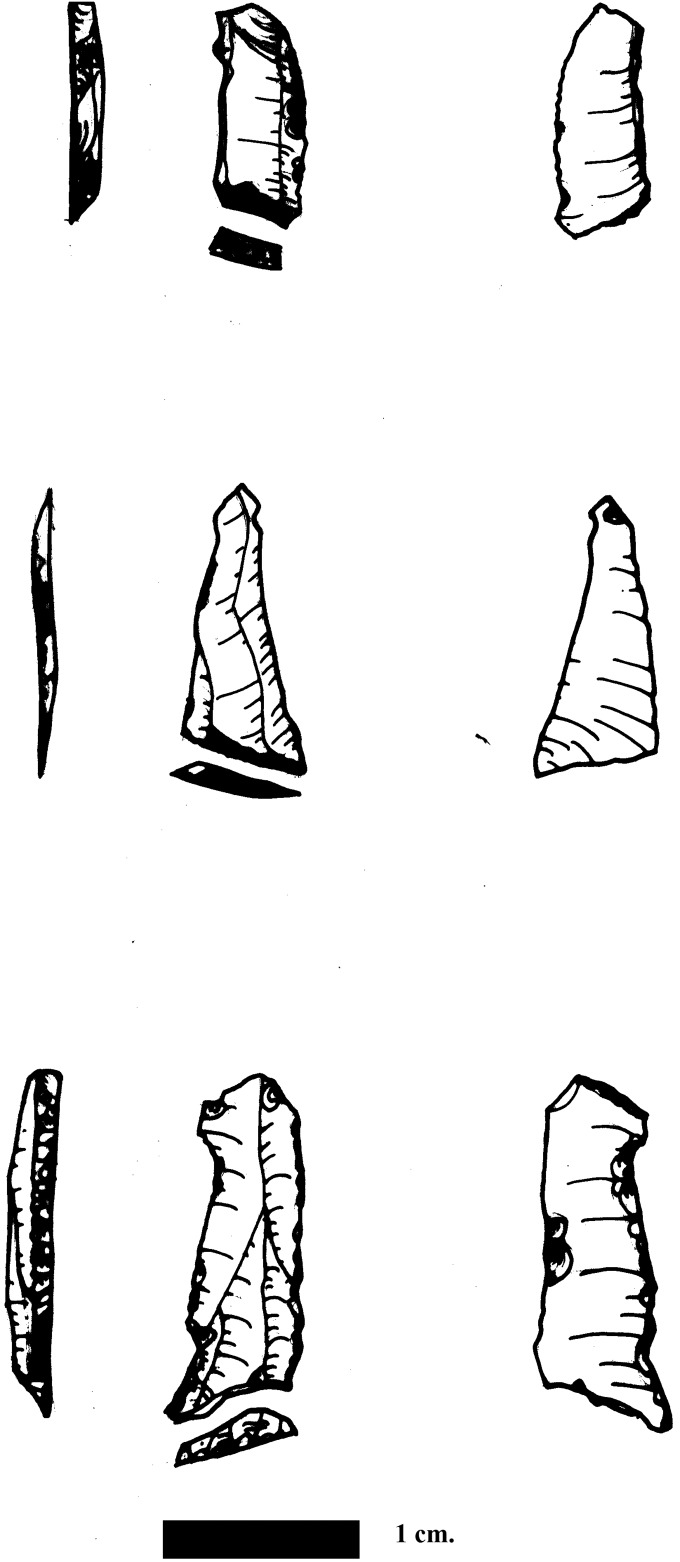

Material culture and ancient DNA (aDNA) evidence also point to the adoption of cultivation and herding by an indigenous Central Anatolian community rather than being brought to the site by incoming farmers from other regions. Among the artifacts, the chipped stone assemblages are very distinctive, being extremely similar through the whole early Holocene occupation sequences at Pınarbaşı and Boncuklu, from the 10th to 8th millennia. Microliths are the principal formal tool type, especially scalene bladelets (Fig. 2), with small flakes being the preponderant debitage (23). Cappadocian obsidian, obtained from 160 km to the east, is the predominant raw material. The assemblages also have clear similarities to local antecedents represented at Epipaleolithic Pınarbaşı (22, 40) and contrast strongly with the contemporary larger blade and point assemblages seen in the PPNA and early PPNB sites of the Levant and southeast Anatolia (22), the regions from which any migrant farmers would have, of necessity, originated. Thus, the lithic evidence suggests that the Boncuklu community was not derived from incoming Levantine or southeastern Anatolian farmer communities, but represent an indigenous forager population. Descent of the 10th/9th millennium populations from earlier local communities, as evidenced at Epipaleolithic Pınarbaşı, is quite probable. While not conclusive in this regard, recent aDNA results from four individuals at Boncuklu give broad support to this proposition, showing that they derived from a genetically distinct Central Anatolian population, contrasting with late Pleistocene and early Holocene Levantine and Iranian populations (41, 42) with low overall genetic diversity, typical of early Eurasian forager populations (43).

Fig. 2.

Typical Boncuklu microliths.

In sum, material culture and aDNA evidence suggest that farming was adopted by an indigenous Anatolian forager community obtaining its cultivars from elsewhere, most probably via exchange, which is clearly evidenced at Boncuklu by the presence of Cappadocian obsidian and Mediterranean shell beads (23, 40). Such exchange networks are already well evidenced at Epipaleolithic Pınarbaşı (21, 22) and those phases at early Holocene Pınarbaşı that predate Boncuklu. Indeed, it is worth noting that the obsidian sources, types of Mediterranean shell beads, and ground stone sources are the same for both sites in the early Holocene. It is also possible that farming could have traveled with those who moved as part of partner exchanges, suggested for later populations in the aceramic Neolithic of the Konya Plain (44), although the low genetic diversity of Boncuklu’s aDNA evidence (43) would suggest any such network was restricted in geographical area.

Adoption and Rejection of Small-Scale Food Production in the Ninth Millennium Cal BC Konya Plain

Multiple sources of evidence suggest that, in contrast to Pınarbaşı, Boncuklu saw the uptake of cropping and experimentation with animal management, in both cases on a modest scale. These data provide an archaeological signature for low-level food production (7), where cropping and herding made a small contribution to the food economy of Boncuklu, complementing the foraging activities that are so well represented through its occupation. Cropping at Boncuklu appears to have remained at a modest scale over at least 500 y of the site’s occupation between approximately 8300 and 7800 cal BC. This persistent low level of cultivation matches the expectations of neither the availability phase nor substitution phase of Zvelebil and Rowley-Conwy agricultural transition model. Rather, Boncuklu saw long-term, stable, and small-scale use of crops, with no immediate rapid phase of transformation into a large-scale farming economy. Pınarbaşı, on the other, hand shows no evidence for cultivation of crops at all and appears not to have taken them into its subsistence system. While some consumption of crop products cannot be excluded at Pınarbaşı, archaebotanical, artifact, and dietary evidence suggests a major quantitative and qualitative difference in plant acquisition and use compared with contemporary phases at Boncuklu.

In this context it seems unlikely that experimentation with sheep/goat herding and long-lived, low-level cropping had a purely economic motivation, such as an increase in food supply. Even food security and risk reduction seem unlikely motivations in this context, where wetland conditions may have caused challenges for cultivation and whose natural productivity offered a significant diversity of foodstuffs, available through most seasons. It seems unlikely that overhunting of this or other species, or impacts of small-scale cultivation on local animal biomass, would account for the herding of what must have been very small numbers of caprines (Table 4). The attraction of cropping may have been the development of diversity in plant-based foods, perhaps introducing a new range of seed foods that were previously unknown or unutilized. Other interests may also have been served in bringing small numbers of caprines in proximity to the community and in taking up cropping, perhaps of a social or symbolic nature. These could have included an interest in displays of control over animals, the consumption of caprine meat in feasts and other contexts, or access to other products that provided materials of both utilitarian and symbolic significance, such as dung, hair, milk, and bone. Cropping may have opened-up new forms of food or beverages, or signified social and cultural ties to other groups in the wider region, well evidenced elsewhere in the artifact record of exchange and interaction (23, 40, 46). Farming may also have been of interest because of the opportunities for social distinctiveness it created for particular households, as seen in the use of diverse household symbolic practices at Boncuklu (47).

Relationships Between the Sites of Pınarbaşı, Boncuklu, and Çatalhöyük

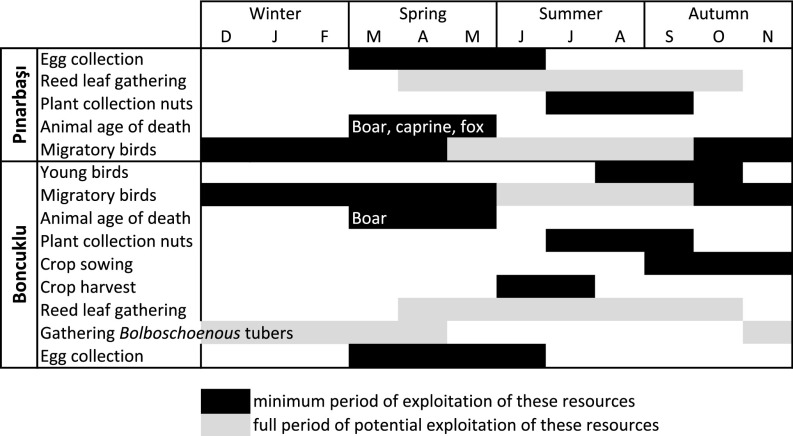

A major issue in understanding the implications of this evidence for the spread of farming is the relationship between the occupants of Boncuklu and Pınarbaşı during the period of approximately 8300–7800 cal BC when both sites were occupied. It is important to establish if the sites were home to separate communities or a single community that used and moved between both settlements. Seasonality evidence (Fig. 3) is crucial in this regard.

Fig. 3.

Indicators of the seasonality of exploitation of particular animal and plant resources on the sites at Pınarbaşı and Boncuklu.

At Pınarbaşı, the birds, studied by N.R., include many year-round residents, spring and autumn migrants, along with overwintering birds, which are better represented than those that only breed in Central Anatolia. Fowling probably concentrated on the more aggregated migrating flocks. It is possible that the majority of birds found were taken during March and April, but such a restricted time period seems unlikely, given the range of species and number of birds represented at Pınarbaşı. Thus, the Pınarbaşı avifauna evidence more likely suggests occupation October–April, with quite possibly additional months represented in the record. The majority of birds from Boncuklu, studied by Y.E., were wetland birds, which could be divided into seasonal migrants, year-round residents, and visitors. The recorded numbers indicate a strong exploitation of overwintering flocks but with spring, early summer, and autumn visitors also targeted to a lesser extent. Indeed, one young bird at approximately 6 mo after hatching could be assigned to early autumn based on the spongy, undifferentiated end of the tibiotarsus. These observations support occupation at Boncuklu from September/October through to April, but do not discount the possibility that birds were exploited for a greater part of the year.

Other seasonally specific resource exploitation evidence common at the sites is indicated in Fig. 3 and demonstrates occupation for most of the year, supporting our view that the communities were sedentary for significant periods. It is notable that the seasons where there is very strong evidence of activity at Boncuklu are also, for the most part, the seasons well represented in the fauna and flora at Pınarbaşı. The only season when evidence for resource exploitation is not clear at Pınarbaşı is late autumn to early winter, but it is likely that winter fowling covers much of this period at Pınarbaşı, as well as at Boncuklu.

There are other contrasts in social and material practices that suggest that we are looking at distinct communities with their own distinctive identities. A range of more elaborate bead and ornament types are found at Boncuklu, but not at Pınarbaşı (46). Pınarbaşı houses had wattle and daub superstructures (21). The walls of Boncuklu buildings are constructed of mudbrick and the buildings have distinctive internal arrangements, with “cleaner” slightly raised southeastern floor areas and “dirtier,” northwestern kitchen areas around the main hearth (Fig. 4). These arrangements reflect a structured and repetitive use of domestic space not seen at Pınarbaşı and prefigure practices at Çatalhöyük with its north/south division between clean and dirty areas in houses (10). Many of the Boncuklu dead were buried under the clean area of the houses during their occupation (47), as at Çatalhöyük East, a practice not documented at Pınarbaşı, where burials seem to have taken place outside buildings, possibly in small cemetery areas (21). There is also greater evidence for ritual and symbolic practice in the buildings at Boncuklu compared with Pınarbaşı. At Boncuklu the clean areas of the houses were idiosyncratically decorated with paint and saw the incorporation of animal bones, especially wild aurochs horns and skulls into the walls and floors (47). Boncuklu’s buildings are repeatedly reconstructed on the same location, over the ancestral dead and ancestral houses, also prefiguring practices at Çatalhöyük, and demonstrate a more institutionalized social role for households than is apparent in communities such as those at Pınarbaşı (47).

Fig. 4.

Typical Boncuklu domestic building.

Therefore, we think it highly unlikely that the groups at Pınarbaşı and Boncuklu belonged to a single coresident community, who moved between two settlement locales, despite the probability of links and interactions between these communities. The highly structured use of domestic space at Boncuklu, with associated ritual and symbolic practices, seems directly antecedent to very similar practices at Çatalhöyük East. This forcefully suggests that the community at Boncuklu was a direct antecedent to that at Çatalhöyük East, although not necessarily the only one (44), unlike Pınarbaşı, whose occupation ended around 7800 cal BC.

Discussion and Conclusions

Analysis of chronological, material culture and seasonality evidence demonstrates that the Konya Plain of Central Anatolia was home to contemporary settlements in the later ninth and early eighth millennium cal BC, occupied by two communities with quite distinctive cultural identities. Although located in broadly similar environments, the two communities made contrasting economic choices: the Boncuklu community adopted and sustained low-level crop cultivation and developed animal management; the Pınarbaşı community rejected both. These settlements maintained their cultural and economic distinctiveness for 300–500 y, despite plentiful evidence of shared technologies and participation in the same exchange networks with the same obsidian sources and a similar range of marine shells. Contemporary Aşıklı, 150 km to the east, appears to provide a further contrast, with a more substantial mixed-farming economy, including a wide range of crops and significant investment in herding (8, 36, 37). The fuller publication of the early phases from Aşıklı will allow even more thorough analysis of these contrasts. Taken together, the evidence shows that in Central Anatolia’s first phase of farming, during the late ninth and early eighth millennium BC, there was an economic mosaic with a network of settlements, connected by exchange and other interactions, supported by different food-procurement strategies. Notably, Boncuklu households demonstrated strong evidence of highly structured domestic behaviors incorporating a major role for symbolic and ritual practices in contrast to Pınarbaşı households. The evidence demonstrates that during the early spread of farming beyond the Fertile Crescent, not only did low-level food production persist for centuries in such contexts, but it was associated with distinct ritual, symbolic, and social practices and thus bound up with community identities.

The first phase of farming in the Konya Plain occurred in the second half of the ninth millennium cal BC through the adoption of cultivation and probably experimentation with herding by indigenous foragers. Clearly, this is at odds with explanations that have attributed farming emergence beyond the Fertile Crescent to the demographic expansion of farmers from that region (3, 4, 11, 19). Evidence does not support a large-scale demographic transition model, and while the archaeological evidence does not preclude the movement of modest numbers of individuals to and fro between Central Anatolia and those areas with farming communities to the south and east, the initial aDNA evidence suggests that Boncuklu’s community was a genetically limited pool (42), distinct from the Levantine Neolithic communities (41) and perhaps, thus, even small-scale movements of people were also not very frequent. It should be pointed out that these statements relate to the initial phase of farming in Central Anatolia and the evidence does not exclude later episodes of farmer colonization or smaller scale population exchanges, the latter of which has been supported by contrast of the Boncuklu population’s genetic record to those from later Neolithic sites in Central and Western Anatolia (42). Rather than be propelled by demic diffusion, cultivation was adopted at Boncuklu from approximately 8300 cal BC as a sustained endeavor used on a small-scale, in absolute terms and relative to other food-acquisition practices. Animal husbandry was also used as part of a range of low-level food-production practices. These practices developed in a context where the social and symbolic significance of herding and cultivation might have been more important than their productive economic value, at least in the initial stages of their adoption.

These observations are important for further understanding both the substantive history of early farming development in Eurasia and its core theory. Cultivation and herding did not arrive on the Konya Plain with a “big bang” but through the introduction of a limited range of plants and animals produced in small quantities. That such low-level food production was stable for at least 300 y does not fit the definition of a “substitution phase” in existing European-focused models of farming transition, those that envisage the existence of “farming frontiers” during which a rapid transition to larger-scale food production occurs (12). This contrast may reflect the distinct circumstances that pertained in areas fringing the Fertile Crescent in the millennia during which sedentism and farming emerged. There was no frontier as such in the Konya region, with incoming farmers absent from its archaeological record, and local indigenous communities responding in diverse and complex ways to the availability of crops and the option of herding animals enabled through their wide-reaching exchange and communication networks.

The uptake of food production within a tightly bound set of cultural practices, appears, thus, to have contributed to the long-term success and perpetuation of the Boncuklu community, and thus may well have provided an important factor in its survival into the mid-eighth millennium and its continuities, probably of population and certainly of social practices, with the community at Çatalhöyük East. Economically, cropping and herding diversified the range of available foods and added some whose production could be increased if required. Beyond that, adoption of farming appears to have had significant social consequences for households at Boncuklu when we consider the major differences between Boncuklu houses and those at Pınarbaşı, where the community rejected farming and apparently continued long-standing preexisting social practices and household behaviors. This is expressed in more intense house-based ritual and symbolic practices, increasingly structured use of domestic space, as well as in the character of and continuities in households at Boncuklu. These factors clearly promoted social stability. Economically, the long phase of low-level food production at Boncuklu provided the foundation for a major transition to large mixed-farming–reliant communities in Central Anatolia following approximately 7800 cal BC, as ultimately represented in the local sequence by Çatalhöyük East. The pace of such changes remain to be demonstrated by further research and it is an open question as to whether this transition from low-level food production to large-scale mixed farming was a rapid step change or slow and incremental.

The persistence of foraging and rejection of farming at Pınarbaşı is also worthy of further consideration. Pınarbaşı’s longevity as a settlement locale in the early Holocene appears to have been based on hunting of wild mammals, wetland exploitation, and significant focus on nut exploitation, all afforded by its ecotonal setting between the hills, plain, and wetland. Perhaps this existing diversity, including nutritious storable plant resources, was a key factor in a lack of interest in adopting cultivation. Another factor may have been a conscious desire to maintain traditional identities and long-standing distinctions with other communities, in part reflected in its particular way of life and its specific connections with particular elements in landscape, for example the almond and terebinth woodlands whose harvests underwrote the continuity of the Pınarbaşı settlement.

The variability in response to the possibilities of early food production in a relatively small geographical area demonstrated here is notable and provides an example useful in evaluating the spread of farming in other regions. It shows the possible role of indigenous foragers, the potential patchwork and diffuse nature of the spread of farming, the lack of homogeneity likely in the communities caught up in the process, the probability of significant continuities in local cultural traditions within the process, and the potentially long-term stable adaptation offered by low-level food production. The strength of identities linked to exploitation of particular foods and particular parts of the landscape may have been a major factor contributing to rejection or adoption of food production by indigenous foragers.

The results are also relevant for understanding the processes that underpinned the initial development of farming within the Fertile Crescent itself: that is, the region in which the wild progenitors of the Old World founder crops and stock animals are found. Recent research has rejected the notion of a core area for farming’s first appearance in southwest Asia and demonstrated that farming developed in diverse ways over the Fertile Crescent zone from the southern Levant to the Zagros, very analogous to the situation just described for Central Anatolia (2). Cultivation, herding, and domestication developed in that region, and it seems inescapable that exchange of crops and herded animals occurred between communities (2), involving a spread of farming within the Fertile Crescent, leading eventually to the Neolithic farming package that was so similar across the region and which spread into Europe (5). Central Anatolia was clearly linked to the Fertile Crescent, with significant evidence of exchange and some shared cultural traditions from at least the Epipaleolithic (22). The evidence presented here demonstrates very clearly the movement of crops between settlements and regions in early phases of the Neolithic through exchange, and thus allows us to identify episodes of crop exchange that were probably taking place within the Fertile Crescent itself, but are difficult, if not impossible, to distinguish due to the presence of crop progenitors across much of the region.

In conclusion, we show that contextually specific explanations for the movement of farming are necessary and should not rely on either simple demographic movement scenarios, on an assumption of homogeneous responses to farming availability in regions, on assumptions of the existence of strongly bounded farming frontiers, or models from other regions that may not be relevant to the local social, cultural, and economic circumstances. In addition, we have provided insights into the consequences of the adoption of food production for forager communities so involved, demonstrating that the early spread of agriculture, like its initial development in the Fertile Crescent, was an extended and variable affair embedded in the social connections and regional exchange networks of the early Holocene rather than driven purely by economic advantage and subsistence concerns.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was undertaken with permission of the Ministry of Culture and Tourism of the Republic of Turkey, with support of the Konya Museum and Karatay Belediyesi. Research was funded by The British Institute at Ankara, British Academy (Research Development Award BR100077), a British Academy Large Research Grant LRG 35439, Australian Research Council (Grants DP0663385 and DP120100969), National Geographic Award GEFNE 1-11, the University of Oxford (Wainwright Fund), Australian Institute for Nuclear Science and Engineering (Awards AINGRA05051 and AINGRA10069), and the Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research (Postdoctoral Research Grant 2008 The Origins Of Farming In The Konya Plain, Central Anatolia).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1800163115/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Asouti E, Fuller D. A contextual approach to the emergence of agriculture in southwest Asia: Reconstructing Early Neolithic plant-food production. Curr Anthropol. 2013;54:299–345. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arranz-Otaegui A, Colledge S, Zapata L, Teira-Mayolini LC, Ibáñez JJ. Regional diversity on the timing for the initial appearance of cereal cultivation and domestication in southwest Asia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:14001–14006. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1612797113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bellwood P. First Farmers. The Origins of Agricultural Societies. Blackwell; Oxford: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bellwood P. The dispersals of established food-producing populations. Curr Anthropol. 2009;50:621–626. doi: 10.1086/605112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barker G. The Agricultural Revolution in Prehistory. Why Did Foragers Become Farmers? Oxford Univ Press; Oxford: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zvelebil M. Mesolithic prelude and Neolithic revolution. In: Zvelebil M, editor. Hunters in Transition. Cambridge Univ Press; Cambridge, UK: 1986a. pp. 5–16. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith B. Low-level food production. J Archaeol Res. 2001;9:1–43. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stiner MC, et al. A forager-herder trade-off, from broad-spectrum hunting to sheep management at Aşıklı Höyük, Turkey. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:8404–8409. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1322723111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Özbaşaran M. Aşıklı. In: Özdoğan M, Başgelen N, Kuniholm P, editors. Neolithic in Turkey; New Excavations, New Discoveries. Central Turkey. Ege Yayınları; Istanbul, Turkey: 2012. pp. 135–158. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hodder I. Çatalhöyük: The leopard changes its spots. A summary of recent work. Anatolian Studies. 2014;64:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Colledge S, Conolly J, Shennan S. Archaeobotanical evidence for the spread of farming in the eastern Mediterranean. Curr Anthropol. 2004;45(Suppl 4):S35–S58. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zvelebil M, Rowley-Conwy P. Transition to farming in northern Europe: A hunter-gatherer perspective. Norw Archaeol Rev. 1984;17:104–128. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zvelebil M. Mesolithic societies and the transition to farming: Problems of time scale and organization. In: Zvelebil M, editor. Hunters in Transition. Cambridge Univ Press; Cambridge, UK: 1986b. pp. 151–166. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sahlins M. Stone Age Economics. Aldine; Chicago: 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Binford L. Post Pleistocene adaptations. In: Binford S, Binford L, editors. New Perspectives in Archaeology. Aldine; Chicago: 1968. pp. 313–341. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kelly R. The Foraging Spectrum. Cambridge Univ Press; Cambridge, UK: 2013. The lifeways of hunter-gatherers. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pennington R. Hunter-gatherer demography. In: Panter-Brick C, Layton R, Rowley-Conwy P, editors. Hunter-Gatherers. An Interdisciplinary Perspective. Cambridge Univ Press; Cambridge, UK: 2001. pp. 170–204. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rowley-Conwy P. Time, change and the archaeology of hunter-gatherers. How original is the ‘original affluent society’? In: Panter-Brick C, Layton R, Rowley-Conwy R, editors. Hunter-Gatherers. An Interdisciplinary Perspective. Cambridge Univ Press; Cambridge, UK: 2001. pp. 39–72. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bar-Yosef O. East to west—Agricultural origins and dispersal into Europe. Curr Anthropol. 2004;45(Suppl 4):S1–S3. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Finlayson W, Warren G. Changing Natures. Hunter-Gatherers, First Farmers and the Modern World. Duckworth; London: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baird D. Pınarbașı; from epipalaeolithic campsite to sedentarising village in central Anatolia. In: Özdoğan M, Başgelen N, Kunihom P, editors. Neolithic in Turkey; New Excavations, New Discoveries. Central Turkey. Ege Yayınları; Istanbul: 2012a. pp. 181–218. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baird D, et al. Juniper smoke, skulls and wolves tails. The Epipalaeolithic of the Anatolian plateau in its SW Asian context; insights from Pınarbașı. Levant. 2013;45:175–209. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baird D, Fairbairn A, Martin L, Middleton C. The Boncuklu project; the origins of sedentism, cultivation and herding in central Anatolia. In: Özdoğan M, Başgelen N, Kuniholm P, editors. Neolithic in Turkey; New Excavations, New Discoveries. Central Turkey. Ege Yayınları; Istanbul, Turkey: 2012. pp. 219–244. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fairbairn A, Asouti E, Near J, Martinoli D. Macro-botanical evidence for plant use at Neolithic Çatalhöyük south-central Anatolia, Turkey. Veg Hist Archaeobot. 2002;11:41–54. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bogaard A, et al. The archaeobotany of mid-later Neolithic occupation levels at Çatalhöyük. In: Hodder I, editor. Humans and Landscapes of Çatalhöyük: Reports from the 2000-2008 Seasons. Monographs of the Cotsen Institute of Archaeology, Univ of California at Los Angeles; Los Angeles: 2013. pp. 93–128. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Özbaşaran M, Güneş D, Kayacan N, Erdoğu B, Buienhuis H. Musular. The 8th millennium cal. BC satellite site of Aşıklı. In: Özdoğan M, Başgelen N, Kuniholm P, editors. Neolithic in Turkey; New Excavations, New Discoveries. Central Turkey. Ege Yayınları; Istanbul, Turkey: 2012. pp. 159–180. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bayliss A, et al. Getting to the bottom of it all: A Bayesian approach to dating the start of Çatalhöyük. J World Prehist. 2015;28:1–26. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boyer P, Roberts N, Baird D. Holocene environment and settlement in the Konya Plain, Turkey: Integrating geoarchaeology and field survey. Geoarchaeology. 2006;21:675–698. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Asouti E, Kabukcu C. Holocene semi-arid oak woodlands in the Irano-Anatolian region of Southwest Asia: Natural or anthropogenic? Quat Sci Rev. 2014;90:158–182. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fairbairn A, Jenkins E, Baird D, Jacobsen D. 9th millennium plant subsistence in the central Anatolian highlands: New evidence from Pınarbașı, Karaman province, central Anatolia. J Archaeol Sci. 2014;41:801–812. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Asouti E. Woodland vegetation and fuel exploitation at the prehistoric campsite of Pınarbaşı, south-central Anatolia, Turkey: The evidence from the wood charcoal macro- remains. J Archaeol Sci. 2003;30:1185–1201. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Savard M, Nesbitt M, Jones MK. The role of wild grasses in subsistence and sedentism: New evidence from the northern Fertile Crescent. World Archaeol. 2006;38:179–196. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Willcox G, Fornite S, Herveux L. Early Holocene cultivation before domestication in northern Syria. Veg Hist Archaeobot. 2008;17:313–325. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tanno K, Willcox G. How fast was wild wheat domesticated? Science. 2006;311:1886. doi: 10.1126/science.1124635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Riehl S, Zeidi M, Conard NJ. Emergence of agriculture in the foothills of the Zagros mountains of Iran. Science. 2013;341:65–67. doi: 10.1126/science.1236743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Zeist W. Some notes on the plant husbandry of Aşıklı Höyük. In: van Zeist W, editor. Reports on Archaeobotanical Studies in the Old World. The Groningen Institute of Archaeology, Univ of Groningen; Groningen, The Netherlands: 2003. pp. 115–142. [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Zeist W, de Roller G. Plant remains from Aşıklı Höyük, a pre-pottery Neolithic site in Central Anatolia. Veg Hist Archaeobot. 1995;4:179–185. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fairbairn A, Near J, Martinoli D. Macrobotanical investigations of the North, South and KOPAL areas at Çatalhöyük. In: Hodder I, editor. Inhabiting Çatalhöyük: Reports from the 1995-1999. McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research; Cambridge, UK: 2005. pp. 1–201. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vigne J-D, et al. First wave of cultivators spread to Cyprus at least 10,600 y ago. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:8445–8449. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1201693109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Baird D. The Late Epipalaeolithic, Neolithic and Chalcolithic of the Anatolian plateau, 13000–4000 BC calibrated. In: Potts D, editor. Blackwell’s Companion to Near Eastern Archaeology. Blackwell’s; Oxford: 2012b. pp. 431–465. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kılınç G, et al. Archaeogenomic analysis of the first steps of neolithisation in Anatolia and the Aegean. Proc R Soc B. 2017;284:20172064. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2017.2064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Broushaki F, et al. Early Neolithic genomes from the eastern Fertile Crescent. Science. 2016;353:499–503. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf7943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kılınç GM, et al. The demographic development of the first farmers in Anatolia. Curr Biol. 2016;26:2659–2666. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2016.07.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baird D. The history of settlement and social landscapes in the Early Holocene in the Çatalhöyük area. In: Hodder I, editor. Çatalhöyük Perspectives. Çatalhöyük Project. Vol 6. McDonald Institute/British Institute of Archaeology at Ankara Monographs; Cambridge, UK: 2006. pp. 55–74. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Asouti E, Fairbairn A. Farmers, gatherers or horticulturalists? Reconstructing landscapes of practice in the early Neolithic. In: Finlayson B, Warren G, editors. Landscapes in Transition. Oxbow Books; Oxford: 2010. pp. 161–172. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Baysal E. A tale of two assemblages; early Neolithic manufacture and use of beads in the Konya Plain. Anatolian Studies. 2013;63:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Baird D, Fairbairn A, Martin L. The animate house, the institutionalization of the household in Neolithic Central Anatolia. World Archaeol. 2017;49:753–776. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.