Abstract

Background

Total hip (THA) and knee arthroplasty (TKA) are two of the most successful procedures in orthopedics. Current evaluation trends focus on patient-reported outcomes. We sought to compare the changing WOMAC scores from various time points from pre-operative to 1-year follow-up between separate THA and TKA cohorts. In addition, we compared THA and TKA patients’ joint perception, satisfaction, and function via a questionnaire.

Methods

One hundred elective THA (n = 50) and TKA (n = 50) patients at one institution were randomly selected and contacted between 2 and 4 years after the index surgery. A questionnaire assessed joint perception, satisfaction and function of their total joint. Clinical function scores utilizing the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) from the pre-operative, 3-month and 1-year post-arthroplasty visits were compared between groups.

Results

78% of the THA group perceived their replaced joint as “native” vs 32% of TKA patients. 54% of THA patients (vs 16% of TKA patients) reported uninhibited function of their total joint. 24% of TKA patients noted to be least satisfied with their total joint compared to 2% in the THA group. Both groups demonstrated significant improvement in WOMAC scores after surgery, but the mean 3-month (12.4 (THA) vs 19.3 (TKA)) and 1-year (6.5 (THA) vs 14.1 (TKA)) follow-up WOMAC scores were significantly better in the THA group.

Conclusion

Evaluation of a patient’s joint perception is a valuable tool that should be used to assess function in conjunction with validated clinical functional scores. Our data suggest further improvements in total knee implant design and implantation strategies are necessary.

Keywords: Joint perception, Adult reconstruction, Total joint arthroplasty outcomes, Total hip arthroplasty, Total knee arthroplasty, WOMAC scores

1. Introduction

Total hip and knee arthroplasty (THA/TKA) are regarded by the medical community as two of the most successful life altering procedures available for patients1,2. There are many ways to evaluate the success of these procedures including implant survival, complications, revision rates, and patient reported outcomes measures (PROMs)3.

Historically, the surgeon was the main judge in determining the success of a total joint arthroplasty (TJA) procedure4,5. This evolved into the traditional era of measuring clinical success by the achievement of various benchmark parameters such as full range of motion and independent ambulation while remaining free from post-operative complications6,7.

In the last few years, there has been a dramatic shift in clinical evaluation parameters across the entire healthcare industry. Patient satisfaction data are now being directly tied to compensation8 and every subspecialty field has started to acknowledge this critical component in its evaluations. Studies in TJA outcomes have noted up to 10% of THA patients2,9,10 and 15–30% of TKA patients11, 12, 13 report dissatisfaction following elective surgery. Perhaps even more concerning, Harris et al. reported on the discordance between patient and surgeon satisfaction after THA and TKA, highlighting the need for TJA surgeons to consider patient reported outcomes as a critical element in the overall success of the procedure14.

The correlation between patient satisfaction and joint specific outcome scores has been well documented14. The Western Ontario and McMaster University Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) has been extensively utilized and remains a very reliable joint specific outcome score that has been shown to be responsive to change over time15,16. In addition, it is one of the most widely used PROMs in the setting of THA and TKA17 as it covers 24 total items across elements of pain, stiffness, and function16. In addition to WOMAC scores, patient reported joint perception following TJA has become a critical component in outcome measures18. Several authors have demonstrated that patients reporting their artificial joint as “natural” as opposed to “artificial” are more likely to report higher rates of satisfaction and have higher outcome scores4.

The purpose of this study was two-fold: First, we sought to investigate and compare the changing WOMAC scores from various time points from pre-operative to 1-year follow-up in separate THA and TKA cohorts. Second, utilizing a basic questionnaire, we compared post-operative patient-reported total joint perception, satisfaction rates, and function following THA and TKA.

2. Methods

Approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) prior to conducting this study. We identified all patients that underwent a primary elective THA or TKA from 2009 to 2011 by a single surgeon at a single institution. We excluded bilateral TJA patients, any cases associated with other procedures, and any TJA procedure that was not elective (i.e. traumatic). Fifty patients were selected at random from each of the elective THA and TKA groups, yielding 100 patients in total. These patients were contacted by phone by an orthopedic resident between 2- and 4-years out from their procedure and each was asked to answer a questionnaire assessing their joint perception, satisfaction and function after undergoing the replacement (Table 1). In terms of patient satisfaction, the questionnaire asked each patient to rate his or her level of satisfaction on a scale of 1–10. Lower scores (=1–6) were associated with some level of patient dissatisfaction while higher scores (=7–10) were considered “overall satisfied” with the TJA.

Table 1.

Patient questionnaire assessing total joint perception, satisfaction, and function.

| Questions | Answer Choices |

|---|---|

| Question 1: “How do you perceive your hip or knee after undergoing total hip or knee replacement? | #1: Like a native or natural joint |

| #2: Like an artificial joint with no restriction | |

| #3: Like an artificial joint with minimal restriction | |

| #4: Like an artificial joint with major restriction | |

| #5: Like a nonfunctional joint | |

| Question 2: “How do you rate your satisfaction after undergoing the total joint arthroplasty on a scale from 1 to 10?” | A score of 1 indicating the worst possible and a score of 10 indicating the best possible result |

| Question 3: “How would you rate the function of your joint after replacement?” | #1: I can do anything |

| #2: I can do most things | |

| #3: I feel limited | |

| #4: I feel severely limited | |

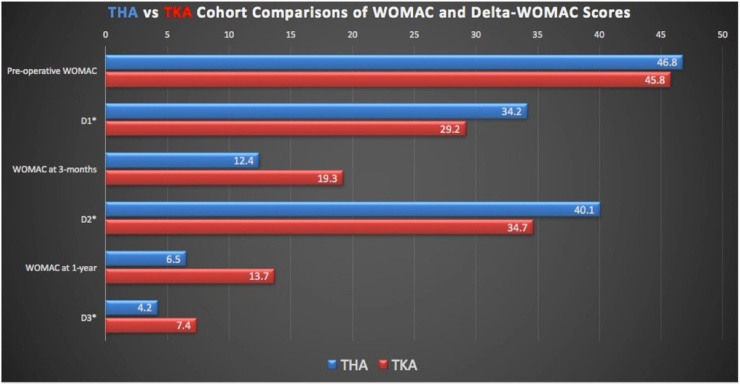

Additionally, clinical function scores using the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) from the pre-operative visit as well as the 3-month and 1-year post-operative follow-up time points were compared between the THA and TKA groups. The overall scores were compared in addition to the magnitude of score changes from the pre-operative period to each of the follow-up time points (Fig. 1). In addition, the post-operative time points were compared to one another (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

WOMAC and Delta-WOMAC score comparisons between THA and TKA groups. Scores are presented as means and include the pre-operative, and 3-month and 1-year post-operative WOMAC scores. In addition, the Delta-WOMAC scores represent the change in score from the pre-operative to 3-month post-operative (= “D1”) period, the pre-operative to 1-year post-operative (=”D2”) period, and the 3-month to 1-year post-operative score change (=”D3”).

The two groups were compared using the Student t-test and the chi-square test for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. Distribution parameters (means, standard deviations (SDs), frequencies, and proportions) were used to describe the study patient sample. Patient demographics (age, gender, BMI) and clinical variables (ASA scores and tourniquet times) were collected from individual chart reviews (Table 2). Data were analyzed using SPSS Statistical Software (IBM Corporation 2012, Somers, NY, USA).

Table 2.

Patient demographic and clinical variables distributed by cohort.

| ASA Scores |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cohort | % Female | Age (years) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | BMIa | Tourniquet Time (min) |

| THA | 38 | 63.14+/− 8.7 | 1 | 36 | 13 | 0 | 28.7+/−4.5 | |

| TKA | 72 | 67.12+/−8.6 | 1 | 22 | 26 | 1 | 31.6+/−7.2 | 33.7+/−6.5 |

| p-values | <0.001 | 0.226 | 0.005 | 0.008 | 0.02 | |||

Continuous variables (Age, BMI, Tourniquet time) are presented as mean +/− standard deviation.

Other abbreviations: THA = Total hip arthroplasty; TKA = Total knee arthroplasty; ASA = American Society of Anesthesiologists score.

P-values in the bottom row represent comparisons between the cohorts with respect to given variable at the α < 0.05 significance level; Bold values represent statistically significant differences.

BMI = body mass index; Units of measurement are kg/m2.

3. Results

The mean ages were similar between the TKA and THA cohorts (67.12+/−8.6 years and 63.14+/−8.7 years, respectively; p = 0.226) (Table 2). By comparison, the TKA cohort was comprised of more females (72% vs 38%, p < 0.001), had higher ASA scores (p = 0.008), and mean BMI values were higher (31.6+/−7.2 vs 28.7+/−4.5, p = 0.02) than the THA cohort (Table 2).

Both the THA and TKA groups were found to have a similar mean pre-operative WOMAC scores of 46.8 and 45.9, respectively (p = 0.832, Fig. 1). However, the mean 3-month and 1-year post-arthroplasty WOMAC scores were significantly better in the THA group (12.4 and 6.5, respectively) compared to the TKA group (19.3 and 14.1, respectively) at both time points (p = 0.014 and p = 0.047, respectively) (Fig. 1). The relative changes in WOMAC scores from the pre-operative to each of the post-operative visits, 3-month (=”D1”) and 1-year (=”D2”), favored greater relative score changes in the TKA group, but this difference did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 1). Likewise, the relative change between the 3-month and 1-year post-operative visits (=”D3”) were also similar between cohorts (Fig. 1).

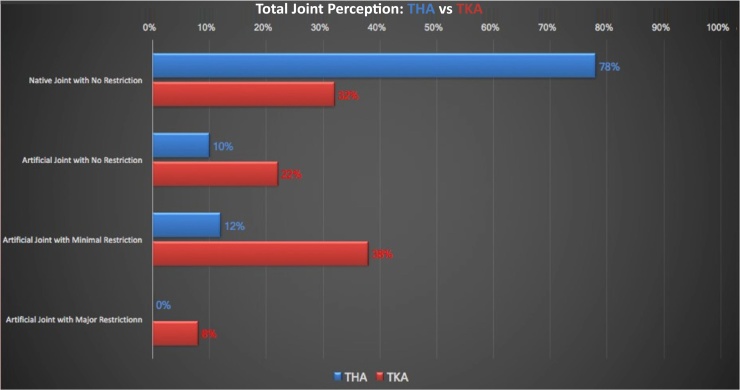

78% of the THA group perceived their replaced joint as a “native/natural” joint with no restriction vs 32% of the patients in the TKA group (p = 0.003, Fig. 2). Furthermore, 46% of the patients who underwent TKA reported their perception of some level of restriction in their artificial joint compared to just 12% reporting restriction in the THA cohort (p = 0.002, Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Patient-reported total joint perception following THA vs TKA. All patients (n = 50) in each cohort were asked how they perceive their total joint following THA or TKA.

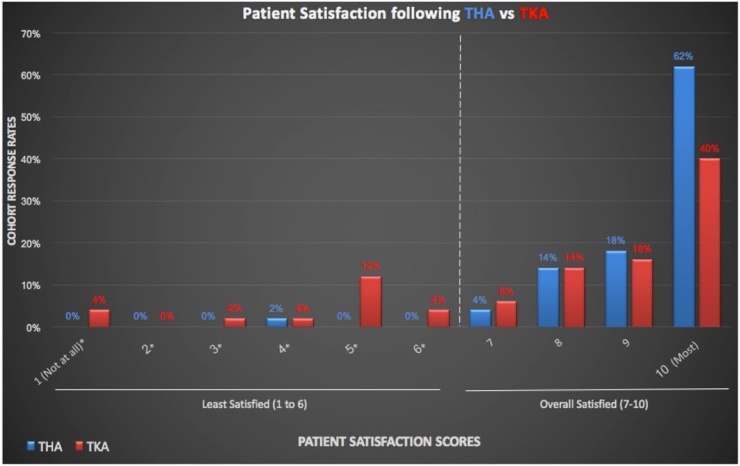

With respect to patient satisfaction, 24% of the TKA cohort expressed some level of dissatisfaction compared to just 2% of patients undergoing THA (p = 0.003, Fig. 3). 98% of THA patients were “overall satisfied” with their surgery (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Patient satisfaction scores following THA vs TKA. All patients (n = 50) in each cohort were asked to rate their level of satisfaction from 1 (=not at all satisfied) to 10 (=most satisfied). Satisfaction ratings from 1 to 6 were considered “least satisfied” ratings and are marked with an asterisk (*). Patient satisfaction scores from 7 to 10 were considered “overall satisfied” with their procedure.

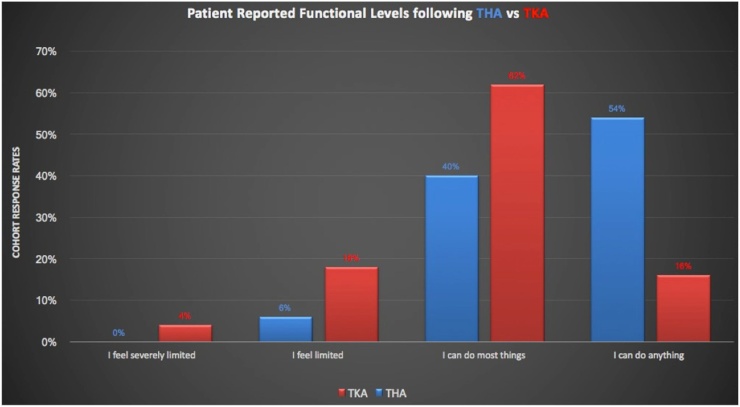

54% of THA patients reported uninhibited function (=“I can do anything”) in response to the questionnaire compared to only 16% of the TKA cohort (p = 0.002, Fig. 4). Almost one-third of TKA patients reported some level of limitation in function (Fig. 4). Patients’ perception and self-reported satisfaction and function scores corroborated with their WOMAC clinical function scores.

Fig. 4.

Patient-reported functional levels following THA vs TKA. All patients (n = 50) in each cohort were asked to select the most appropriate response indicating their current functional level of their total joint replacement.

4. Discussion

THA and TKA remain two of the most successful, cost-effective orthopedic procedures19. As volume and popularity continue to increase, TJA surgeons are challenged to improve results in terms of PROMs and patient satisfaction rates after surgery12,15. While we still lack a generalized definition of success following TJA, several clinical variables have been shown to play important roles in TJA outcomes. Some of these variables are system-based (e.g. hospital and/or surgeon case volumes) while many are patient-related (e.g. socioeconomic status, medical comorbidities, and preoperative patient expectations)11,20, 21, 22. There has been a trend in the literature focused on assessing the relationship between THA and TKA patient-reported outcomes and patient-reported joint perception18,24.

Our study adds to the existing body of literature reporting the aforementioned post-operative WOMAC score discrepancies in favor of THA over TKA2,18,25. Furthermore, our study demonstrates THA patients’ perceived function and satisfaction rates were superior to those reported in the TKA cohort, and these results corroborated with their clinical function scores. While the latter is somewhat intuitive, there is a paucity of data demonstrating correlation between WOMAC scores and joint perception. Collins et al. recently showed patient joint perception strongly correlated with WOMAC scores in both THA and TKA patients18. In addition, this same study noted lower WOMAC scores and significantly worse joint perception in the TKA cohort18.

As we continue to comprehensively re-define success following TJA, the concept of joint perception rapidly evolved into its own validated PROM specific to artificial joints, known as the Forgotten Joint Score (FJS-12)26. The ultimate goal following elective TJA, as reported through the FJS-12, is for patients to forget their artificial joint26. While we did not utilize the FJS-12 in our study, our inclusion of joint perception approximates a much broader post-operative evaluation component in TJA based on a patient’s awareness of his or her artificial joint27. Thus, our study has provided PROMs, patient joint perception, patient satisfaction rates, and patient-reported functional levels as part of a multifaceted approach that has become the contemporary standard in evaluating overall success following elective TJA2.

Our study does have several limitations. While the mean age and mean pre-operative WOMAC scores were similar between the TKA and THA cohorts, a greater proportion of TKA patients were female and both ASA scores and mean BMI values were significantly higher in the TKA cohort (Table 2). Although no consensus has been reached regarding the impact of age, gender, and BMI with respect to relative impact on patient outcomes and satisfaction12,22, we performed separate chi-squared analyses with respect to each clinical variable and outcome of interest, and none of these demonstrated statistical significance at the

other important variables were not factored into our study. Pre-operative expectations23, clinical depression13, and incidence of post-operative complications2 have been demonstrated to negatively impact patient outcomes and satisfaction. Finally, our sample size was relatively small, although the magnitude of this limitation is somewhat diminished as we did achieve statistical significance in our primary outcome of interest.

As we move forward in a changing healthcare environment centered on PROMs and patient satisfaction rates in addition to the traditional evaluation modalities, the field of TJA is redefining its critical determinants of success. As these components continue to delineate, it is vital for orthopedic surgeons to understand the current patient-centered approach and plan the pre-operative discussion with each patient accordingly. By elucidating some of the differences between THA and TKA, we feel it is important for the TJA surgeon to discuss the greater potential for an inferior relative outcome when comparing these 2 procedures.

Conflict of interest statement

Each author certifies that he or she has no commercial associations (eg, consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

Ethical review committee statement

This study has been reviewed and approved by our ethical committee. We will provide the official letter as a separate attachment.

Study location

This research was performed at the Rothman Institute at Abington-Jefferson Health, Willow Grove, Pennsylvania.

Contributor Information

Matthew Varacallo, Email: matt.varacallo@tenethealth.com.

Rajit Chakravarty, Email: rajit.chakravarty@tenethealth.com.

Kevin Denehy, Email: kevin.denehy@louisville.edu.

Andrew Star, Email: Andrew.Star@RothmanInstitute.com.

References

- 1.Kahn T.L., Soheili A.C., Schwarzkopf R. Poor WOMAC scores in contralateral knee negatively impact TKA outcomes: data from the osteoarthritis initiative. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(8):1580–1585. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2014.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bourne R.B., Chesworth B., Davis A., Mahomed N., Charron K. Comparing patient outcomes after THA and TKA: is there a difference. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(2):542–546. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-1046-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Theodoulou A., Bramwell D.C., Spiteri A.C., Kim S.W., Krishnan J. The use of scoring systems in knee arthroplasty: a systematic review of the literature. J Arthroplasty. 2016;31(10):2364–2370. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2016.05.055. e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Behrend H., Zdravkovic V., Giesinger J., Giesinger K. Factors predicting the forgotten joint score after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2016;31(9):1927–1932. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2016.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lieberman J.R., Thomas B.J., Finerman G.A., Dorey F. Patients’ reasons for undergoing total hip arthroplasty can change over time. J Arthroplasty. 2003;18(1):63–68. doi: 10.1054/arth.2003.50010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hamilton D.F., Giesinger J.M., MacDonald D.J., Simpson A.H., Howie C.R., Giesinger K. Responsiveness and ceiling effects of the forgotten joint score-12 following total hip arthroplasty. Bone Jt Res. 2016;5(3):87–91. doi: 10.1302/2046-3758.53.2000480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ha C.W., Park Y.B., Song Y.S., Kim J.H., Park Y.G. Increased range of motion is important for functional outcome and satisfaction after total knee arthroplasty in Asian patients. J Arthroplasty. 2016;31(6):1199–1203. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2015.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shirley E.D., Sanders J.O. Patient satisfaction: implications and predictors of success. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 2013;95(10):e69. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.L.01048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Watson B.S., Jenkins P.J., Ballantyne J.A. The natural history of unexplained early poor function following total hip replacement. Int Orthop. 2014;38(1):33–37. doi: 10.1007/s00264-013-2099-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bourne R.B., Chesworth B.M., Davis A.M., Mahomed N.N., Charron K.D. Patient satisfaction after total knee arthroplasty: who is satisfied and who is not. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(1):57–63. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-1119-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berliner J.L., Brodke D.J., Chan V., SooHoo N.F., Bozic K.J. Can preoperative patient-reported outcome measures be used to predict meaningful improvement in function after TKA. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2017;475(1):149–157. doi: 10.1007/s11999-016-4770-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jacobs C.A., Christensen C.P. Factors influencing patient satisfaction two to five years after primary total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(6):1189–1191. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2014.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hirschmann M.T., Testa E., Amsler F., Friederich N.F. The unhappy total knee arthroplasty (TKA) patient: higher WOMAC and lower KSS in depressed patients prior and after TKA. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2013;21(10):2405–2411. doi: 10.1007/s00167-013-2409-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harris I.A., Harris A.M., Naylor J.M., Adie S., Mittal R., Dao A.T. Discordance between patient and surgeon satisfaction after total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28(5):722–727. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2012.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giesinger J.M., Hamilton D.F., Jost B., Behrend H., Giesinger K. WOMAC, EQ-5D and knee society score thresholds for treatment success after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2015;30(12):2154–2158. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2015.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giesinger K., Hamilton D.F., Jost B., Holzner B., Giesinger J.M. Comparative responsiveness of outcome measures for total knee arthroplasty. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2014;22(2):184–189. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2013.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chesworth B.M., Mahomed N.N., Bourne R.B., Davis A.M., SG O.J.R.R. Willingness to go through surgery again validated the WOMAC clinically important difference from THR/TKR surgery. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(9):907–918. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Collins M., Lavigne M., Girard J., Vendittoli P.A. Joint perception after hip or knee replacement surgery. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2012;98(3):275–280. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2011.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gwynne-Jones D.P., Iosua E.E., Stout K.M. Rationing for total hip and knee arthroplasty using the new zealand orthopaedic association score: effectiveness and comparison with patient-reported scores. J Arthroplasty. 2016;31(5):957–962. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2015.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Naal F.D., Impellizzeri F.M., Lenze U., Wellauer V., von Eisenhart-Rothe R., Leunig M. Clinical improvement and satisfaction after total joint replacement: a prospective 12-month evaluation on the patients’ perspective. Qual Life Res. 2015;24(12):2917–2925. doi: 10.1007/s11136-015-1042-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maratt J.D., Lee Y.Y., Lyman S., Westrich G.H. Predictors of satisfaction following total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2015;30(7):1142–1145. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2015.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Williams D.P., O’Brien S., Doran E. Early postoperative predictors of satisfaction following total knee arthroplasty. Knee. 2013;20(6):442–446. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2013.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Neuprez A., Delcour J.P., Fatemi F. Patients’ expectations impact their satisfaction following total hip or knee arthroplasty. PLoS One. 2016;11(12):e0167911. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0167911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuroda Y., Matsumoto T., Takayama K., Ishida K., Kuroda R., Kurosaka M. Subjective evaluation before and after total knee arthroplasty using the 2011 knee society score. Knee. 2016;23(6):964–967. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2016.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Caracciolo B., Giaquinto S. Determinants of the subjective functional outcome of total joint arthroplasty. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2005;41(2):169–176. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Behrend H., Giesinger K., Giesinger J.M., Kuster M.S. The “forgotten joint” as the ultimate goal in joint arthroplasty: validation of a new patient-reported outcome measure. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(3):430–436. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2011.06.035. e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matsumoto M., Baba T., Homma Y. Validation study of the forgotten joint score-12 as a universal patient-reported outcome measure. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2015;25(7):1141–1145. doi: 10.1007/s00590-015-1660-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]