Abstract

Introduction: Adolescence is a challenging period and cultural background plays an important role in families with adolescent. So exploring parents’ concerns in the specific context of Iran may improves nurses' family-based services and helps to reduce conflicts Iranian families with respect to adolescents. In this paper we explore perceptions of Iranian parents’ concerns in the family with raising adolescent children.

Methods: Participants of this qualitative content analysis study were 23 parents with adolescents, who were recruited through purposive sampling. Data collection was done through semi structured in-depth interviews and analyzed based on Graneheim and Landman’s approach. Lincoln and Guba’s criteria were used to ensure the accuracy and strength of the study.

Results: The theme "rebellion against parents’ authority" was supported by two categories: (1) parent-teenage conflict, and (2) difficulty in controlling. As the offspring enter adolescence, parents feel that their child is going to leave their domain.

Conclusion: Findings from this study showed that the incongruity arises when traditional family norms fail to adapt to new patterns. Change of social and cultural norms in developing societies, has led to generational differences in families. This issue accompanied with adolescence, increases parents’ concern. So we recommend parental educational programs for learning effectively patterns for resisting internal challenges and communicate with adolescents.

Keywords: Adolescent, Family, Fathers, Mothers, Parenting qualitative

Introduction

Both during adolescence and thereafter (having survived various struggles), adolescents gradually look for a new balance. Adolescents often experience physical, psychological, social and behavioral changes1 that result in difficulties for them and those around them. This is a difficult stage for both adolescents2 and also for the entire family and often increases tensions as well as inappropriate behaviors and relationships between parents and adolescents.3 Family changes through various development stages and adapts itself to the growth of children.4 Failure to deal adequately with them will disrupt the family.5,6 According to the 2011 census, the population of the age group of 10-19 years in Iran was reported to 12.3 million.7 Therefore, the study on adolescents is very important in our country.

The lack of proper communication with the parents is one of the problems in this period. Most conflicts between parents and their offspring occur during adolescence and inappropriate interaction between them is considered one of the greatest problems in this period.8,9 Many parents find their adolescent discordant. This perception leads to employing distinctive behaviors by parents against their offspring.10 Parents often behave based on the presumption that they share a common privacy with their adolescent without any boundaries.

This assumption often results in disturbing adolescents’ privacy which is correlated with their anxiety, depression and low satisfaction.11 In otherwords, adolescents perceive some of their parents’ behaviors as intrusion into their privacy.12 For most parents and families, this period is one of tension and rebellion.10

Review of literature and study existing research gaps according to result of studies contexts (family, home, school, and neighborhood) exert a powerful influence on adolescent development.4,13,14 Severe offenses in families create and solidify emotional and behavioral problems in adolescents15 and, in some cases, these might have outcomes such as delinquency, addiction, neurotic disorders, dropping out of school, leaving home, etc.16,17

Delinquency related literature identifies this period as challenging and critical for both parents and adolescents.18 Numerous studies have investigated these challenges and relevant solutions 19,20 and a majority of them have focused on parenting methods and their effects on adolescents and the ways of managing this period by parents.21-23 However, no clear answers have emerged as to why parents perceive this period as being so challenging, what issues parents exactly experience and what their concerns are relating to their adolescent offspring.

According to various studies, parents in Iran, like other countries, have similarly faced discrepancies administering their parental role and find raising adolescents to be extremely stressful.3 Also growth of social networks and the changing patterns of communication among adolescents are in many cases unwelcome for parents.24,25 In particular, recent social and cultural evolutions in Iran have brought about additional issues during this period. For instance, an increase in the number of city dwellers and further industrialization have generated new lifestyles among Iranian families and have presented the necessity for expanding social norms and modern patterns.26,27 Also the research conducted in Iran showed that the behavioral and emotional problems are seen in adolescents.28,29 In the Iranian society, the family is considered as the basic social unit in which the child plays a central role. Families are responsible for their children at all stages of life and they live with their parents until they are married even during their adulthood. Raising a child in such context where family relationships are limited and closed can cause differences.30,31

In order to comprehensively examine parents’ experiences, it is necessary to consider both social and cultural background. Exploring parents’ concerns regarding their adolescents’ upbringing can provide supporting strategies and proper planning. Reducing conflicts between parents and adolescents, can be an important step taken towards improving adolescents’ mental health. Therefore, the present study was conducted with the aim of exploring concerns of Iranian parents with their adolescents.

Materials and methods

This qualitative study was conducted in 2016 (January- December inclusive). Conventional content analysis was used to describe concerns of parents with their adolescents. In order to recruit parents of adolescent children, the researcher (MRF) contacted school administrators and gained permission to contact high schools across Tabriz city zones. Tabriz is the capital of East Azerbaijan province and located in northwest of Iran. Cultural variation was ensured, by selecting high schools from all five education districts of Tabriz.

Participants of this study were parents with adolescents, who were chosen via purposive sampling. The researcher, with the help of school staff, informed parents about the study when they attended a school meeting, dropped their child off at school, or enquired about their child’s educational status. The researcher consciously selects certain participants and Information-rich cases that can teach a great deal about the central focus of the study. The parents should have adolescent children between the ages of 12-18 years the parents should be living together, and neither of the parents should have a diagnosed mental health disorder. We selected only the most eager and vocal participants. A total of 23 participants were chosen: 13 mothers and 10 fathers. In-depth interviews were conducted individually, face-to-face, in a private room, on school grounds. All interviews were recorded (audio) and lasted between 45 to 71 minutes. The unstructured interview started with a general question in both mothers and fathers and explored the main concern of parents about their adolescent offspring. Sample of asked fallow up questions were: “As a parent, what is your main concern about your adolescent offspring?” and “Can you have proper interactions with your offspring?” or “What issues do you and your offspring face?”

Probes such as “How so?” and “Why?” were used for clarifying the response of participants. When data saturation was reached no further interviews were conducted.

All interviews were analyzed using conventional content analysis based on Graneheim and Lundman’s approach. First, the interviews were transcribed verbatim and reviewed several times to obtain a sense of the whole. Second, the text was analyzed word-by-word, line-by-line and paragraph-by-paragraph and it was divided into meaning units that were condensed. For example one of the participants described her experiences about her adolescent son's issues as such: “I have problems with his studying. He is just lazy and sleeps a lot, doesn’t study as expected e.g., He lies down in front of the TV.” The meaning unit obtained from this quote, was “ignoring the lessons and watch TV instead of studying.” The condensed meaning units were abstracted and labelled with a code. After abstracting mentioned meaning unit, codes of “non-sense of responsibility for studying” and “waste of time” were extracted. The various codes were compared based on differences and similarities and sorted into sub-categories and categories. For example that codes along with other similar codes, were abstracted into sub-category in title of “behaviors incongruous with parents’ expectations”. We repeatedly revised the basic texts and during the next step, the theme was formed based on latent content of the categories.32 In order to categorize and manage the data, MAXQDA 10 software was used.

Lincoln and Guba’s criteria were used to ensure the accuracy and strength of the study.33 In credibility criteria, to prolonged time in the field (period of 11 months from January 21, until December 20), the duration of the interviews with participants at schools was increased and also regular research team meetings including the in-depth review of transcripts, discussion of initial findings with participant to obtain their thoughts regarding the extracted codes and categories. Moreover, the study team are experienced qualitative researchers and there was extensive monitoring throughout. Some of interviews along with the codes was shared with the parents in order to ensure their agreement regarding accuracy of the extracted codes. To meet the criteria of dependability and confirmability, an audit trail was kept including a journal of reflections by the researcher which was monitored and discussed during project supervision. For transferability, maximum variation in terms of culture, parental age, education level, occupation and number of children were considered during recruitment.

This study approved by the Ethics Committee of Tabriz University of medical sciences (No. 5.4.13613 & ethics code: TBZMED.REC.1394.1071). Interested parents were then provided with information about the study and assured that should they wish to participate all information would be kept confidential. Verbal and written consent was obtained from all study participants for participation in the study and recording their voice.

Results

Participants of this study were 23 parents with adolescent offspring. Mean age of mothers was 42.53 with a standard deviation of 4.11. Fathers’ age mean was 45.88 with a standard deviation of 6.11 and adolescents’ age mean was 15.68 with a standard deviation of 1.91. Seven mothers had adolescent daughters and six mothers had adolescent sons. Among male participants, four fathers had adolescent daughters and six fathers had adolescent sons. Parents’ educational attainment ranged from junior high school to postgraduate studies. The number of offspring in each family varied from one to three.

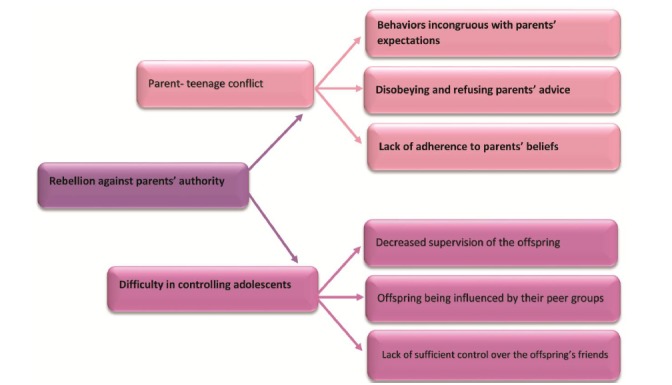

The theme “rebellion against parents’ authority” emerged from the data. As the offspring enter adolescence, parents feel that their child is going to leave their domain. This theme was supported by two categories: “parent- teenage conflict” and “difficulty in controlling adolescents” Figure 1 displays the theme, categories and sub-categories.

Figure 1.

Theme, categories and sub-categories of concerns for Iranian parents with adolescents

Parent- teenage conflict

Following offspring’s entrance into their adolescence, some of their behaviors contradict their parents’ wants, beliefs and opinions. "Behaviors incongruous with parents’ expectations" was first sub-category of parent- teenage conflict. The following are some examples:

A 44-year-old mother said: “My daughter does something that we really don’t like, neither me nor her father, because they are completely against our beliefs. For a while she was regularly saying her prayers but, she has stopped, she uncovers her hair.”

Another mother said: “I have problems with his studying. He is just lazy and sleeps a lot, doesn’t study as expected e.g., He lies down in front of the TV. He’d had some problems with her school lessons and had failed in some classes, but hadn’t told us his grades.”

Disobeying and refusing parents’ advice was another sub-category, which usually occurred in the context of social behaviors. Parent emphasis the adolescent to cover her hair completely or not make up when they go out, but the offspring does not observe these advices. Also, he or she does not obey the parents' orders about to do housework, or despite parents' emphasis, returns home late:

A 45-year-old father said: “She doesn’t like housework. For example, I ask her to do the dishes some days, but she puts off doing it and finally doesn’t do it. Most of the time that we work around the house, she lies on the sofa and says: ‘I won’t help, if you have much to do, ask a cleaner!” Another 41-years-old mother said: “Despite our home laws, my son went out with his friend and returned late. I repeated this several times, but he did not pay attention at all. ”

Adolescents’ "lack of adherence to their parents’ beliefs" was the last issues. Parents were unable to convince their offspring to accept their beliefs and faced resistance by their adolescents. Parents regularly argue with their offspring:

A 38-year-old mother said: “We can’t coerce her into doing anything. If we ask nicely, she may do it but, most of the time, she persists in her own ideas. For example, about hijab, we argue and talk a lot but she never accepts it. We always have conflicts at home.”

Difficulty in controlling adolescents

As the child grows up, parents feel that their control over their offspring has decreased and they cannot sufficiently supervise them:

A 43-year-old mother said: “When he was a child, I had more control over him. As he grows up, my control decreases. I myself get older too, I get weaker and he gets stronger. Since he has grown up, my concerns have grown too. He isn’t with me all the time and I’m not near him at every moment.”

In parents' opinion, influence of peers and friends on their adolescents and its outcomes are inevitable. They copy and learn many things from their close friends. Losing peers is disappointing for an adolescent. Moreover, each peer (such as a classmate) experiences their own unique issues that can cause problems for parents and their offspring:

One 45-year-old- father said: “The influence of a friend is tremendous. In this age, they accept their friends’ ideas more than their parents’ advice. They may accept what we say easily, if it’s said by their friend. Whatever they don’t know, they learn from each other. Once, he had gotten a low mark and his friend had advised him not to show it to me.”

One 38-year-old mother talked about such concerns and said: “Her classmates are very important for her. She is influenced by them. She thinks if she acts against their ideas, she’ll lose them and will be alone at school.”

The final issue is lack of sufficient control over the offspring’s friends. This emphasized parents’ concerns that their adolescents might have relationships with people who are completely different from their own families in terms of culture and behavioral norms and the parents’ inability to control the behavior of their offspring’s friends.

A 38-year-old mother said: “She has friends at school with whom she’s gotten close and they influence her way of life. I don’t know how them. Everyone has their own beliefs and I can’t control who she may meet.”

Discussion

The present study was conducted through conventional content analysis with the aim of exploring the concerns of Iranian parents regarding their adolescents. Rebellion against parents’ authority was revealed as the theme of the study and the most important concern of Iranian parents. The word authority is defined as the domain of leadership and possession, which is related to a geophysical space.34 In the social sciences, domain is more than just a container. Domain is the result of social activities and processes in which space and society are connected to each other and it is considered a reflection of authority, power and control.35 Humans manifest their authoritarianism in the form of interactions, confinement, access, management and control.36 When a slight loss occurs in any of these areas, a person may feel that the subject has exited their domain. In this study, "parent-teenage conflict" categories was identified with behaviors incongruous with parents’ expectations, disobeying parents and lack of adherence to the parents’ beliefs.

Parents have conflict with their offspring, when adolescents do not behave according to their expectations. The reason for such incongruity may be changing social and cultural norms. Generational values of the Iranian people have evolved often in incongruent ways. In Iran, families are deeply rooted in the country national culture as well as religious beliefs.30 This situation has led to a discrepancy between traditional and modern values and beliefs.27 Consequently, today we see conflicts within families due to the divergence of modern values from those more traditional.

Adolescents’ disobedience of their parents was addressed in a study examining disobedience both at school and at home.37 Formation of these behaviors in adolescents is associated with their age and also to a great extent by their parents’ behavior. Using the wrong method to influence offspring can increase conflict and result in adolescents rebelling against parents’ authority.

The second category was difficulty in controlling adolescents. Controlling is a process that compares what there must be and what there is now and compares ideals with what is existing. Controlling refers to limitations, roles and behaviors that are banned for the offspring.38

Parental control was first conceptualized as a parenting styles. In 1990’s researchers began clarifying the concepts of behavioral and mental control and defining each distinctly.39 Behavioral control refers to aspects such as parents’ expectations, setting rules and supervising the offspring. On the other hand, mental control is parents’ attempt to control offspring’s activities negatively, which affects their mental status. Aggressive and harsh behaviors such as using impulsive verbal expressions, imposing feelings of guilty and not expressing love are examples of mental control.38,40

Based on the emerged concepts, parents believe that their supervision of their offspring has decreased. Offspring, after entering adolescence, seek independence, authority and information, and prefer to access these on their own and often this deviates from parents’ ideals, resulting in parents feeling a lack of control.12 Adolescents try to exert independence in decision making, in their feelings and actions and tend to distance themselves from their parents’ control.41 Consequently, parents feel that their supervision of their offspring has decreased. Since supervision helps identify deviations, it is superior to controlling; a decrease in supervision may result in a decrease in controlling.42

The concept of “offspring being influenced by their peer groups” and “lack of sufficient control over the offspring’s friends” are also reveal parents’ concerns regarding their decreasing degree of control over their adolescents. Peer groups play a major role in adolescents’ socialization and result in decreased dependence on their families. Friendships with peer groups tend to deepen during this period of life. Rejection by one’s peers is a large and burdensome issue for an adolescent.43 While positive relationships can decrease social anxiety in adolescents, negative relationships and lack of love can cause depression.44 One study showed that school friends affect each other’s behavior, including problematic behaviors.45 Another study revealed that the possibility of smoking in adolescents, who have smoker friends, is higher than others.46 Overall, adolescents are influenced to a greater degree by their peers’ influence than their parents’ or communal values’ effect.47 Therefore, as identified in this study and consonant with other studies, friends and related issues are among parents’ major concerns.

Generally, adolescence consists of stages in which different changes take place.48 Puberty is a physical, cognitive and moral development,49 which occurs during early adolescence. Mid-adolescence brings a tendency towards being influenced by peers.48 The concepts that emerged in this study are consistent with the changes observed in these stages of adolescence. Parent-child conflict is commonly observed during early adolescence and being influenced by one’s peer group is often seen during mid-adolescence.

Various previous studies have mentioned the categories observed in this study. However, in the present study all of the concepts are presented under the comprehensive umbrella of “rebellion against parents’ authority,” demonstrating parents’ concern about their adolescent offspring. Our findings also support the importance of context-related factors. Because of that the findings of this study should be considered in the context of Iranian culture and religion. Certain issues are specific to Iranian society, values and religious views and, in this regard, may be different than issues of concern for parents of other cultures. For example concern about observing proper dressing and, having an appropriate appearance such as not wearing frippery make-up are the specific issues in our country. We are witnessing the conflict that arises when traditional family norms fail to adapt to new changes. This accompanied with adolescence, intensifies parents’ concern.

Although the strengths of the study included a significant number of interviews with both mothers and fathers recruited from multiple school settings, in this study the parents’ family problems and the spouse marital issues, was not investigated completely and deeply. Also, the study focused on the parents’ expressions and their opinions were not conformed to their children viewpoints. The findings of this study reflect the cultural characteristics of a society.

Based on this, statewide parental education should be implemented in two domains: first, from an intrapersonal perspective, parents should improve appropriate patterns to resist their inner challenges; second, from an interpersonal aspect, parental education should emphasize teaching influential ways of communication with their adolescent as well as better recognition and understanding of their adolescent’s condition.

Conclusion

The results of this study show that rebellion against parents’ authority is a concern for parents during their offspring’s adolescence. The rebellion against authority is mostly related to the physical, mental and social changes during this period. The changes in adolescence such as a desire for autonomy and identity, may result in parent-teenage conflict. These issues along with cognitive developments, logical and ethical justifications and formation of values and viewpoints in adolescents might cause a greater distance between parents and their offspring. On the other hand, adolescents’ great inclination towards their peers results in taking an interest in their peers and copying similar behavior. Therefore, managing the offspring by the peer groups puts their parents mentally under pressure. Of course, each of above-mentioned points has complicated and deep relationship with each other and considering the condition, they may occur as a cause or effect or as a chain of events and variously affect parents’ feelings and experiences.

Acknowledgments

This article was part of a PhD dissertation. Authors’ sincere appreciation goes to the all research participants and Tabriz University of Medical Sciences.

Ethical issues

None to be declared.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest in this study.

Citation: Valizadeh L, Zamanzadeh V, Rassouli M, Rahkar Farshi M. Concerns of parents with or raising adolescent children: a qualitative study of Iranian families. J Car Sci 2018; 7 (1): 27-33. doi:10.15171/jcs.2018.005

References

- 1.Kaye DK. Negotiating the transition from adolescence to motherhood: coping with prenatal and parenting stress in teenage mothers in Mulago hospital, Uganda. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:83. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seraji F, Alibakhshi M. Parents’ Worries about Harm Caused to Adolescents by Computer Games: Findings from a Mixed Methods Research. Quarterly Journal of Family and Research. 2015;12(1):31–50. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parvizi S, Ahmadi F. Adolescence health and friendships, a Qualitative study. Journal of Kashan University of Medical Sciences. 2007;10(4):46–51. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Leifer G, Fleck E. Growth and development across the lifespan. 2nd ed. Netherlands: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2013.

- 5. Bitter JR. Theory and practice of family therapy and counseling. 2nd ed. United States: Brooks Cole 2013.

- 6.Baumrind D. The influence of parenting style on adolescent competence and substance use. J Early Adolesc. 1991;11(1):56–95. doi: 10.1177/0272431691111004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Statistical Center Of Iran. Selected finding of the 2011 national population and housing census Tehran [Internet]. 2011 [cited 25 Feb 2015]. Available from: https://www.amar.org.ir/Portals/1/Iran/census-2.pdf.

- 8.Fuligni AJ. Gaps, conflicts, and arguments between adolescents and their parents. New Dir Child Adolesc Dev. 2012;2012(135):105–10. doi: 10.1002/cd.20006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nasiri M, Tefagh M, Maghsoudi J, Hasan zade A. Comparative investigation of adolescent’s communicational problems wtthparents from the points of view of these two groups. Journal of Shahrekord Uuniversity of Medical Sciences. 2001;3(2):31–8. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Talakoub B, Esmailee M, Salimi Bajestani H. The effectiveness of guided imagery in reducing parent-child conflicts. Family and research. 2013;10(1):127–41. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hale WW, Raaijmakers QAW, Gerlsma C, Meeus W. Does the level of expressed emotion (LEE) questionnaire have the same factor structure for adolescents as it has for adults? Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2007;42(3):215–20. doi: 10.1007/s00127-006-0145-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hawk ST, Keijsers L, Hale III WW, Meeus W. Mind your own business! Longitudinal relations between perceived privacy invasion and adolescent-parent conflict. Journal of Family Psychology. 2009;23(4):511. doi: 10.1037/a0015426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fine A, Mahler A, Steinberg L, Frick PJ, Cauffman E. Individual in context: the role of impulse control on the association between the home, school, and neighborhood developmental contexts and adolescent delinquency. J Youth Adolesc. 2017;46(7):1488–502. doi: 10.1007/s10964-016-0565-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Skuse D, Bruce H, Dowdney L, Mrazek D. Child psychology and psychiatry: frameworks for practice. 2nd ed. United States: Wiley 2011.

- 15.Moharreri F, Soltanifar A, Khalesi H, Eslami N. The evaluation of efficacy of the positive parenting for parents in order improvement of relationship with their adolescents. Medical Journal of Mashhad University of Medical Sciences. 2012;55(2):116–23. (Persian). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rahmani r, Seyed fatemi n, Baradaran RM, Sedaghat k. Relationship between parenting style and academic competence among adolescents studying in Tabriz high schools, 2002. Journal of Fundamentals of Mental Health. 2006;8(30):11–6. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zarei E. Relationship between parent child– rearing practices and high risk behavior on basis of cloninger's scale. Journal of Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences. 2010;18(3):220–4. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rezai Niaraki F, Rahimi H. The impact of authoritative, permissive and authoritarian behavior of parents on self-concept, psychological health and life quality. European Online Journal of Natural and Social Sciences. 2013;2(1) [Google Scholar]

- 19.Trick S, Jantzer V, Haffner J, Parzer P, Resch F. Parental monitoring and its relation to behavior problems and risk behaviour in an adolescent school sample. Praxis der Kinder psychologie und Kinderpsychiatrie. 2016;65(8):592–608. doi: 10.13109/prkk.2016.65.8.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Medlow S, Klineberg E, Jarrett C, Steinbeck K. A systematic review of community-based parenting interventions for adolescents with challenging behaviours. Journal of adolescence. 2016;52:60–71. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mounts NS. Parental management of adolescent peer relationships in context: the role of parenting style. J Fam Psychol. 2002;16(1):58–69. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.16.1.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuppens S, Laurent L, Heyvaert M, Onghena P. Associations between parental psychological control and relational aggression in children and adolescents: a multilevel and sequential meta-analysis. Dev Psychol. 2013;49(9):1697–712. doi: 10.1037/a0030740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paley B, Conger RD, Harold GT. Parents' affect, adolescent cognitive representations, and adolescent social development. J Marriage Fam. 2000;62(3):761–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.00761.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ahn J. The effect of social network sites on adolescents' social and academic development: Current theories and controversies. J Am Soc Inf Sci Technol. 2011;62(8):1435–45. doi: 10.1002/asi.21540. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mikami AY, Szwedo DE, Allen JP, Evans MA, Hare AL. Adolescent peer relationships and behavior problems predict young adults' communication on social networking websites. Dev Psychol. 2010;46(1):46–56. doi: 10.1037/a0017420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parvizy S, Ahmadi F. A qualitative study on adolescence, health and family. Ment Health Fam Med. 2009;6(3):163–72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sadeghi Fasaei S, Erfanmanesh I. Social analysis of modernization impacts on Iranian families and the necessity of planning an Iranian-Islamic example. Journal of Woman in Culture Arts. 2013;5(1):61–82. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mohammadi MR, Arman S, Khoshhal Dastjerdi J, Salmanian M, Ahmadi N, Ghanizadeh A. et al. Psychological problems in Iranian adolescents: application of the self-report form of strengths and difficulties questionnaire. Iran J Psychiatry. 2013;8(4):152–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mohammadi MR, Salmanian M, Ghanizadeh A, Alavi A, Malek A, Fathzadeh H. et al. Psychological problems of Iranian children and adolescents: parent report form of strengths and difficulties questionnaire. J Ment Health. 2014;23(6):287–91. doi: 10.3109/09638237.2014.924049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sharifi V, Mojtabai R, Shahrivar Z, Alaghband-Rad J, Zarafshan H, Wissow L. Child and adolescent mental health care in Iran: current status and future directions. Arch Iran Med. 2016;19(11):797–804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Behjati-Ardakani Z, Navabakhsh M, Hosseini H. Sociological study on the transformation of fertility and childbearing concept in Iran. Journal of Reproduction & Infertility. 2017;18(1):153–161. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. 2004;24(2):105–12. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic inquiry. United States: SAGE Publications; 1985.

- 34.Heidari Far MR. Concept of territory in global era. Geopolitics Quarterly. 2011;7(4):120–36. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Richardson CB, Mulvey KL, Killen M. Extending social domain theory with a process-based account of moral judgments. Human Development. 2012;55(1):4–25. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Smetana JG. Moral development: The social domain theory view. The oxford handbook of developmental psychology: body and mind. 1st ed. New York, NY, US: Oxford University Press; 2013.

- 37.Kalhotra SK, Sharma V. A comparative study on obedient/disobedient behavior in secondary+ 1 level students. US-China Education Review. 2013;3(9):685–92. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Grolnick WS. The Psychology of Parental Control: How Well-meant Parenting Backfires. 3rd ed. New York: Psychology press, Taylor & Francis group; 2012.

- 39.Soenens B, Beyers W. The cross-cultural significance of control and autonomy in parent-adolescent relationships. J Adolesc. 2012;35(2):243–8. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shek DT, Law MYM. Parental behavioral control, parental psychological control and parent-child relational qualities: relationships to Chinese adolescent risk behavior. Chinese Adolescents in Hong Kong. 2014;5:51–69. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Markova S, Nikitskaya E. Coping strategies of adolescents with deviant behaviour. Int J Adolesc Youth. 2017;22(1):36–46. doi: 10.1080/02673843.2013.868363. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Soenens B, Vansteenkiste M, Sierens E. How are parental psychological control and autonomy-support related? a cluster-analytic approach. J Marriage Fam. 2009;71:187–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2008.00589.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Safari Shali R, Abde-Molaee A. The impact of socialization factors on adolescents’ identity peers, school, and mass media. Quarterly Journal of Family and Research. 2015;12(2):117–36. [Google Scholar]

- 44.La Greca AM, Harrison HM. Adolescent peer relations, friendships, and romantic relationships: do they predict social anxiety and depression? J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2005;34(1):49–61. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3401_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Geven S, Weesie J, van Tubergen F. The influence of friends on adolescents’ behavior problems at school: The role of ego, alter and dyadic characteristics. Social Networks. 2013;35(4):583–92. doi: 10.1016/j.socnet.2013.08.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fuemmeler BF, Taylor LA, Metz AE, Brown RT. Risk-taking and smoking tendency among primarily African american school children: moderating influences of peer susceptibility. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2002;9(4):323–30. doi: 10.1023/a:1020743102967. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Parvizi S, Ahmadi F, Pourasadi H. A qualitative study on social predisposing factors of adolescents’ health. Iran Journal of Nursing. 2011;24(69):8–17. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hockenberry M, Wilson D. WONG'S nursing care of infants and children. 9th ed. Netherlands: Mosby/Elsevier; 2010.

- 49.Sajjadi M, Moshki M, Abasnezhad A, Bahri N. Educational needs of fathers about boys puberty period and its related factors. Zahedan Journal of Research in Medical Sciences. 2012;14(2):66–70. [Google Scholar]