Abstract

Introduction: Coping with disease is of the main components improving the quality of life in multiple sclerosis patients. Identifying the characteristics of this concept is based on the experiences of patients. Using qualitative research is essential to improve the quality of life. This study was conducted to explore the features of coping with the disease in patients with multiple sclerosis.

Method: In this conventional content analysis study, eleven multiple sclerosis patients from Iran MS Society in Tehran (Iran) participated. Purposive sampling was used to select participants. Data were gathered using semi structured interviews. To analyze data, a conventional content analysis approach was used to identify meaning units and to make codes and categories.

Results: Results showed that features of coping with disease in multiple sclerosis patients consists of (a) accepting the current situation, (b) maintenance and development of human interactions, (c) self-regulation and (d) self-efficacy. Each of these categories is composed of sub-categories and codes that showed the perception and experience of patients about the coping with disease.

Conclusion: Accordingly, a unique set of features regarding features of coping with the disease were identified among the patients with multiple sclerosis. Therefore, working to ensure the emergence of, and subsequent reinforcement of these features in MS patients can be an important step in improving the adjustment and quality of their lives.

Keywords: Qualitative research, Multiple sclerosis, Coping

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic debilitating disease which appears in young adults in the most productive period of their lives1 and 85% to 90% of patients are characterized with periods of worsening and improvement.2 This disease is the most common neurological disorder in humans and the most common disease leading to disability in young people.3 It is considered one of the most important life-changing diseases, because it damages the best time of the individuals’ life and leads them gradually to inability.4

The number of patients in Iran has been announced 40000, which is on the rise; however, some people with this disease have still not been diagnosed.5 The prognosis of this disease is uncertain and the patients experience various physical and mental disorders that strongly influence their daily performance, social and family lives, functional independence, and individual planning for the future.6,7,8 The disease is also associated with negative consequences and emotional distress such as depression which the patients need to cope with.9

On the other hand, the cost of treatment for any patient with multiple sclerosis in Iran is estimated to be $1,000 monthly10 and much of the costs is imposed on patients, together with physical and mental disabilities caused by the disease which require more coping with the disease.11

The patients, who suffer from chronic diseases such as multiple sclerosis, have numerous problems and having to deal with the disease is only one of them.12 Considering the specific problems of these patients, it is required that the way they cope with their disease ought to be in a way, or have characteristics that would help it work.

Coping with chronic illnesses is strongly associated with the quality of life due to biological, physical, psychological and social stresses they impose, and thus exert profound influences on individuals, their families and social interactions with the outside world.13 On the other hand, coping with disease facilitates the healing process by preventing further complications, increasing the effectiveness of patient care and family support, thus leading to better coping with the disease.14 From the perspective of patients, coping with chronic diseases such as multiple sclerosis is not also limited to a process; however it includes different stages and is often repeated.12 Therefore, the explanation of the features of coping with the disease based on the experiences of patients can be effective in the transfer from mere medical focus to using individual experiences for improving coping and the quality of life.15

Features of coping with diseases contain factors and characteristics that are frequently seen in patients who succeed in coping with the disease, and these characteristics can be a model for other peers in coping with the disease. The explanation and identification of these features using qualitative researches can enable health professionals and families to help patients foster their abilities in coping with the disease and enhance their quality of life. However, quantitative studies might fail to do so, as they might, in such cases, be incapable of creating rich data, which is often the result of deep understanding of the phenomenon. On the other hand, coping with the disease is a multidimensional concept,16 which could vary depending on the context and Soci-cultural factors as well as being affected by the differences within and across individuals.17 Furthermore, such issues might be coupled with certain problems which are peculiar to the Iranian context to further complicate the matter; Iranian patients with MS may not have easy access to the required medications, may lack support in terms of rehabilitation, treatment costs, etc., which are specific to the area of Iran.18 Achieving a better quality of life and also help achieve positive outcome. Therefore, this study adopted a qualitative approach to explore the features of coping with the disease in patients with multiple sclerosis.

Materials and methods

This study is a qualitative research with conventional content analysis approach which was performed in 2015 in Iran MS Society at Tehran. In this approach, the codes classification were directly extracted from the interviews.19,20 In this study, the categories were extracted irrespective of preconceived categories of data.

Eleven patients with multiple sclerosis participated in the study (6 women and 5 men). Patients were selected through purposive sampling, based on the willingness and ability to provide a rich experience. Data collection was continued until saturation which occurred when a new category and data did not appear. The inclusion criteria for the participants were a-having a definite diagnosis of multiple sclerosis disease by a neurologist, b-having the desire to participate in the study, and c- having the ability to express experiences, d- having at least two years of experience of MS. The data were collected through semi-structured and in-depth face to face interviews. Each interview lasted on average 60 to 110 min. All interviews were conducted in a peaceful environment and with prior agreement of the participants. All Interviews were conducted in Iran MS Society at Tehran. The interviews began with the main questions “what does coping with the disease mean to you?” “What are the main features of a person who has been coping with their disease?” After each interview, the text was transcribed on a word file and the initial codes were extracted after several times of listening. Then, the sub-categories and categories were formed based on the similarities of the extracted codes. All patients were interviewed only once.

In analyzing the data, the Graneheim and Lund man models21 were used, with the following steps: a- transcribing the interview immediately after it was conducted, b- reading the entire text to understand its general content, c- determining units of meaning and initial codes, and d- classifying the initial codes in more comprehensive categories. To provide rigorous and reliable data, the researchers spent quite a long time in the field, collecting the data and analyzing the data collected. Recommendations of the associates and other specialized partners in this area were used to determine the categories. Coded interviews were returned to the participants to reach agreement among the researchers and participants in the research.

This study is part of a doctoral thesis approved by the ethics committee of Tehran University of Medical Science in Iran (Code of Ethics IR.Tums.Rec.1394.1171). Before data collection, the researchers obtained oral and written informed consents ensuring the confidentiality of the names of people, preserving privacy and emphasizing voluntary participation. The participants were informed of the purposes of the research, and provided with the researcher’s contact information so that they could have their questions answered. All participants were assured of the confidentiality of the information.

Results

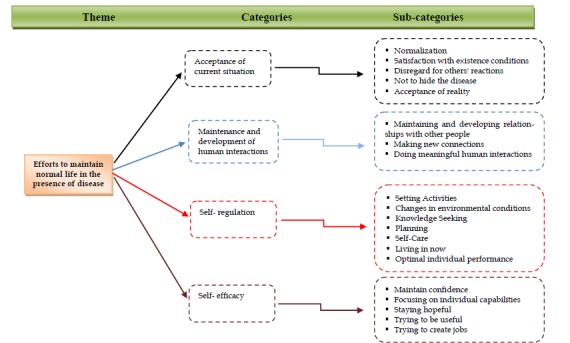

The mean age of the participants was 33.2, and the average dealing duration was 10.5 years. Based on the content analysis, four main categories were obtained including: 1- acceptance of the current situation 2- maintenance and development of human interactions 3- self-regulation and 4- self-efficacy. The categories were integrated in the heart of normal life maintenance in the presence of diseases. Each category contains several sub-categories that are listed in figure 1.

Figure 1.

The Categories and Sub-categories of interviews with patients about coping with disease

Accepting the current situation

This category includes subcategories of becoming normal, feeling satisfied with the existing status, ignoring the reactions of others, and accepting the fact rather than concealing it. Participants believed that accepting the current position along with accepting the realities of the disease, the chronic nature, treatment, complications of the disease are symptoms of coping with the disease. Additionally, the participants expressed that lack of response to others about the disease, lack of fear and shame about revealing the illness, coping in a simple and relaxed way with the disease, as well as being satisfied with the conditions can help to accept the position and cope with the disease. One of the participants about the satisfaction with the existing conditions said: “I'm happy with my condition. I have my job and also when the students come by, I talk with them about my abilities....” (Participant #3, age 40, 11 years of disease experience).

The other participant, regarding the acceptance of the disease, stated: “I think coping with the disease means that I accept my disease and not hide it from others”. (Participant #5, age 29, 2 years of disease experience).

Maintenance and development of human interactions

This category includes subcategory of maintenance and development of relationships with people, and making new meaningful connections and social interactions. Most participants thought of the maintenance and development of relationships with family members or other peers with MS joining and interacting in forums, especially in the MS Society as well as social interactions with other people with different ideas and religions, as features of coping with the disease. Patients also noted maintenance of the role and social relationships and having effective communications with people are the signs of coping with the disease. In this regard, one participant said:

“I have maintained my relationships with other people like the past .... The disease didn’t affect my relationships with family and others”. (Participant #2, age 31, 15 years of disease experience).

Another participant said: “I am in touch with various MS associations in different cities and even some foreign countries. I read the trusted magazines of MS International Federation”. (Participant #3, age 40, 11 years of disease experience).

Self-regulation

This category includes subcategories of regulation of the activities, changing the environmental conditions, seeking for knowledge, planning, and self-care, living at the present and demonstrating a desirable individual performance. Participants expressed that patients can cope with disease through self-regulation behaviors, including the modulation of activities and environments appropriate to their condition, having adequate knowledge about the disease and planning, adaption to their disease. Also from the perspective of the participants, seeking information about patients, making plans for the future, and enjoying the present moment, regardless of the disease and self-care indicate the coping with disease by the patient. A participant in this regard, said:

“I have no problem with MS. I go climbing. Now I should have more time to rest. For example, if I previously worked 8 hours a day, now I work 6 hours a day, I do not let myself feel the fatigue”.(Participant #3, age 40, 11 years of disease experience). A participant about finding information in the study, said: “I read an article, and I became more open minded to the disease. I got to know the disease better.... studies were very helpful”. (Participant #1, age 32, 16 years of disease experience).

Regarding the planning for the future especially with the disease, a participant noted: “despite the disease I only work, thinking about the future, and I plan to live. When I go to bed while I do not know whether I will be alive tomorrow or not, yet I do hope to stay alive". (Participant #11, age 24, 4 years of disease experience).

As for the changes in environmental conditions another participant said “in any environment I set my environment with the disease in mind, for example, to reduce fatigue, I take required equipment available...” (Participant #6, age 29, 6 years of disease experience).

Self- Efficacy

This category includes the subcategories of maintaining self-confidence, focusing on individual capabilities, hoping, trying to be useful and create employment. The participants believed that having a positive attitude and being full of energy, hoping for the future and a better tomorrow, trying to be effective for the community and proving the individual abilities in the presence of the disease symptoms in patients with MS are indicators of coping with the disease. A participant in this regard, said: “I am always hoping for a better tomorrow. I hope that a cure will be discovered for multiple sclerosis...” (Participant #10, age 46, 17 years of disease experience).

One of participants on the employment and efforts to benefit the community said: “Thanks to God I was able to set up an employment workshop where was also selected as the top entrepreneurs...” (Participant #11, age 24, 4 years of disease experience).

Regarding trying to be useful and to focus on individual capabilities, another participant also noted, “Despite being bound to the wheelchair, I do my daily work independently. I buy the house requirements and I feel that I am effective...” (Participant #10, age 46, 17 years of disease experience).

About the protection of the confidence a participant stated: “when would you like me to take my wheelchair along to play soccer with you?”... I even jokingly asked them when I could go to their houses to steal a wheelchair”. (Participant #4, age 27, 5 years of disease experience).

The concept of "efforts to maintain normal life in the presence of the disease" was extracted from the categories of accepting the current situation, maintenance and development of human interactions, self-regulation, and self-efficacy. The most important feature of coping with the disease in patients with multiple sclerosis is the efforts patients make to have a normal life in the same condition. Trying to focus their thoughts on their daily activities rather than the disease, and endeavoring to nurture hope and adopt a positive outlook about the future, the patients want to stand on their own feet and take care of their work independently.

Discussion

According to the results of this research, features of coping with multiple sclerosis were identified in four categories: accepting current situation, maintenance and development of human interactions, self-regulation and self-efficacy. The first feature of coping with the disease is accepting the current situation. From the perspective of the participants, the main feature of individuals coping with the disease is that patients accept the terms and conditions as they are. Acceptance of the disease can include cognitive acceptance (acceptance of its chronic nature, being incurable, the treatment and complications of the disease), emotional acceptance (with calm and confidence), and behavioral acceptance (conducting activities to protect personal goals). These findings are consistent with the results of Dennison et al., according to whom acceptance prognostic uncertainty is a key factor in coping of MS patients.22 Hwang et al., argues that the acceptance of disease diagnosis and carrying out the required performances for protection of health alongside having a positive vision are necessary to restore a sense of well-being and health.23 Studies in this area suggest

that if patients accept their disability and disease, then they accept themselves, they are more likely to be accepted by society. These studies also confirm that such patients are more likely to understand emotional support than discrimination and also have higher self-esteem and satisfaction with life.24,25 Maintenance and development of human interactions is the second floor and feature of coping with the disease in MS patients.

Maintenance and development of personal and social human interactions means developing the communications with other people and to avoid the isolation of the same disease. These findings are consistent with Silverman et al., where participants mentioned social connections as facilitators and social limitations as barriers to resilience in people with multiple sclerosis.26 Based on the results obtained by Tangney et al., and Murray et al., interpersonal and social interactive relationships have positive impacts on the knowledge, confidence, social support, clinical outcomes, behavior, improving decision-making, and self-care.27,28 According to the results of Irvine et al., also relationships with others, family, and friends is a big selling point in coping with the disease of patients and uncertainty of living with MS.9 On the other hand, the poor social interactions may lead to an increase in the use of avoidance coping strategies as well as depression and psychological distress in patients, thus leading to a mismatch between the person and the disease.29

The third floor obtained from the data was self-regulation which was mentioned as the features of coping with disease. Self-regulation includes the efforts by the patient in order to perform activities targeted at the disease. From the perspective of the participants carrying out the activities such as planning, living in the present, activities appropriate to the patient's condition, having a good individual performance, seeking information about the disease, and self-care are the symptoms of coping with MS. According to the results of this study, one of the subsets of self-regulation is seeking information about the disease. In the qualitative study by Ghafari et al., information seeking was considered as one the coping factors in MS patients, which is consistent with the findings of the present study.30 Also according to the findings of Fallahi-Khoshknab et al., knowledge deficit was one of the themes extracted in confronting with MS, which is also consistent with the findings of the present study.31

Another subset of the self-regulation was self- care. Studies indicate that following self-care activities not only improves the quality of life for individuals and families, but also play an important role in reducing health care costs associated with repeated

hospitalizations.32,33 Jaarsma et al., notes adherence to self-care behaviors in patients with chronic diseases is very important and patients performing self-care can affect their comfort, functional ability, and disease process.34 The other subset of self- regulation was planning. Planning for the future is considered an important variable in the process of changing behavior. So that scheduling by patients is followed by promotion of self-care, independence and decision-making, and doing individual activities, which could improve the quality of life and thus lead to better coping of the patients with the disease.33

The other main category obtained through the data was the self- efficacy. Self- efficacy is beliefs of patients with MS about their ability to perform the desired functions for coping with the disease. From the perspective of patients, individuals’ beliefs in their own strengths and abilities in disease management, and also trying to be useful, creating jobs, hoping and maintaining the confidence are the features of coping with the disease. Self-efficacy creates motivations directly through efficiency expectations and also influences the motivation of the patient through the perceived barriers or steadfastness to continue the commitment to follow-up plans of action.35 High self- efficacy increases the chances of success in active performance in the actual physical ability.36 While low self-efficacy is related to increased levels of stress, poorer responses to pain and less motivation to pursue programs related to health.37 For example, a subset of self- efficacy in this study was to preserve confidence. Lear month states that if a patient has no self-confidence in developing balance and abilities, it is unlikely that they can perform the actual activities appropriate to their ability and capacities. While a belief in individual abilities and strengths reinforces self-confidence, and the motivation of the patient and can lead to improved quality of life and coping with the disease.38

Coping with the disease is a multi-faceted phenomenon that not only patients but also community members and health personnel (physicians, nurses, specialists, psychologists, social workers, etc.) play important roles in the process of changing behaviors related to health and wellbeing in people. And since coping with the disease is inevitable in order to improve the quality of life, identifying the characteristics of compliance with the disease and using various educational approaches and therapists to help patients in order to have a normal life in the presence of the disease is necessary. The results of this study are limited to features consistent with the disease into the culture of Iran, so more studies are required to use more findings to be done in different cultures, as well as the small sample size in this study do not necessarily represent all patients with multiple sclerosis is not Iran.

Conclusion

Acceptance of the current position, maintenance and development of human interactions, self-regulation and self-efficacy are the features of patients coping with MS disease. Our findings suggest that effective interventions should be performed in order to strengthen the mentioned features in patients especially those recently diagnosed with the disease and patients with poor coping in order to help them cope with these conditions.

Acknowledgments

This study was part of a PhD dissertation in nursing. This research was funded by the research department at Tehran University of Medical Sciences. Authors extend their appreciation to all the study participants for their contributions.

Ethical issues

None to be declared.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest in this study.

Citation: Dehghani A, Dehghan Nayeri N, Ebadi A. Features of coping with disease in Iranian multiple sclerosis patients: a qualitative study. J Car Sci 2018; 7 (1): 35-40. doi:10.15171/jcs.2018.006

References

- 1.Goretti B, Portaccio E, Zipoli V, Hakiki B, Siracusa G, Sorbi S. et al. Impact of cognitive impairment on coping strategies in multiple sclerosis. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2010;112(2):127–30. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2009.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Busch AK, Spirig R, Schnepp W. Coping with multiple sclerosis in partnerships: a systematic review of the literature. Nervenarzt. 2014;85(6):727–37. doi: 10.1007/s00115-014-4017-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dehghani A, Mohammad khan Kermanshahi S, Memarian R, Hojati H, Shamsizadeh M. The effect of peer-led education on depression of multiple sclerosis patients. Iranian Journal of Psychiatric Nursing. 2013;1(1):63–71. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belbasis L, Bellou V, Evangelou E, Ioannidis JP, Tzoulaki I. Environmental risk factors and multiple sclerosis: an umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14(3):263–73. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14):70267-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Etemadifar M, Sajjadi S, Nasr Z, Firoozeei TS, Abtahi SH, Akbari M. et al. Epidemiology of multiple sclerosis in Iran: a systematic review. Eur Neurol. 2013;70(5-6):356–63. doi: 10.1159/000355140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stadelmann C. Multiple sclerosis as a neurodegenerative disease: pathology, mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Curr Opin Neurol. 2011;24(3):224–9. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e328346056f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scalfari A, Neuhaus A, Degenhardt A, Rice GP, Muraro PA, Daumer M. et al. The natural history of multiple sclerosis, a geographically based study 10: relapses and long-term disability. Brain. 2010;133(7):1914–29. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burschka JM, Keune PM, Hofstadt-van Oy U, Oschmann P, Kuhn P. Mindfulness-based interventions in multiple sclerosis: beneficial effects of Tai Chi on balance, coordination, fatigue and depression. BMC Neurol. 2014;14(1):165. doi: 10.1186/s12883-014-0165-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Irvine H, Davidson C, Hoy K, Lowe-Strong A. Psychosocial adjustment to multiple sclerosis: exploration of identity redefinition. Disabil Rehabil. 2009;31(8):599–606. doi: 10.1080/09638280802243286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Etemadifar M, Izadi S, Nikseresht A, Sharifian M, Sahraian MA, Nasr Z. Estimated prevalence and incidence of multiple sclerosis in Iran. Eur Neurol. 2014;72(5-6):370–4. doi: 10.1159/000365846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ghanati E, Hadiyan M, Daghighi asli AR. Economic expenditures of multiple sclerosis medications and feasibility of providing health insurance policies for medications. Journal of Health Administration. 2011;14(45):37–54. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bachmann S. Coping with chronic disease. Praxis. 2014;103(7):379–84. doi: 10.1024/1661-8157/a001605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tallner A, Waschbisch A, Hentschke C, Pfeifer K, Mäurer M. Mental Health in Multiple Sclerosis Patients without Limitation of Physical Function: The Role of Physical Activity. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16(7):14901–11. doi: 10.3390/ijms160714901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Atik D, Karatepe H. Scale Development Study: Adaptation to Chronic Illness. Acta Medica Mediterranea. 2016;32(1):135–42. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lode K, Bru E, Klevan G, Myhr K, Nyland H, Larsen J. Coping with multiple sclerosis: a 5‐year follow‐up study. Acta Neurol Scand. 2010;122(5):336–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2009.01313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bianchi V, De Giglio L, Prosperini L, Mancinelli C, De Angelis F, Barletta V. et al. Mood and coping in clinically isolated syndrome and multiple sclerosis. Acta Neurol Scand. 2014;129(6):374–81. doi: 10.1111/ane.12194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bogart KR. The role of disability self-concept in adaptation to congenital or acquired disability. Rehabil Psychol. 2014;59(1):107–15. doi: 10.1037/a0035800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ghandehari K, Riasi HR, Nourian A, Boroumand AR. Prevalence of multiple sclerosis in north east of Iran. Multiple Sclerosis. 2010. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Valizadeh L, Zamanzadeh V, Habibzadeh H, Alilu L, Gillespie M, Shakibi A. Experiences of Iranian nurses that intent to leave the clinical nursing: a content analysis. J Caring Sci. 2016;5(2):169–78. doi: 10.15171/jcs.2016.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–88. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. 2004;24(2):105–12. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dennison L, McCloy Smith E, Bradbury K, Galea I. How Do People with Multiple Sclerosis Experience Prognostic Uncertainty and Prognosis Communication? A Qualitative Study. PloS one. 2016;11(7):e0158982. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0158982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hwang JE, Cvitanovich DC, Doroski EK, Vajarakitipongse JG. Correlations between quality of life and adaptation factors among people with multiple sclerosis. Am J Occup Ther. 2011;65(6):661–9. doi: 10.5014/ajot.2011.001487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mercer K, Giangregorio L, Schneider E, Chilana P, Li M, Grindrod K. Acceptance of commercially available wearable activity trackers among adults aged over 50 and with chronic illness: a mixed-methods evaluation. JMIR mHealth and uHealth. 2016;4(1) doi: 10.2196/mhealth.4225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Verhoof EJA, Maurice-Stam H, Heymans HS, EversAWM EversAWM, Grootenhuis MA. Psychosocial well-being in young adults with chronic illness since childhood: the role of illness cognitions. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health. 2014;8(1):12. doi: 10.1186/1753-2000-8-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Silverman AM, Verrall AM, Alschuler KN, Smith AE, Ehde DM. Bouncing back again, and again: a qualitative study of resilience in people with multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil. 2017;39(1):14–22. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2016.1138556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tangney JP, Baumeister RF, Boone AL. High self-control predicts good adjustment, less pathology, better grades, and interpersonal success. J Pers. 2004;72(2):271–324. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-3506.2004.00263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murray E, Burns J, See TS, Lai R, Nazareth I. Interactive Health Communication Applications for people with chronic disease. Cochrane Database syst rev. 2005;4 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004274.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cacioppo JT, Cacioppo S. Social relationships and health: The toxic effects of perceived social isolation. Soc Personal Psychol Compass. 2014;8(2):58–72. doi: 10.1111/spc3.12087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ghafari S, Fallahi-Khoshknab M, Nourozi K, Mohammadi E. Patients’ experiences of adapting to multiple sclerosis: a qualitative study. Contemp Nurse. 2015;50(1):36–49. doi: 10.1080/10376178.2015.1010252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fallahi-Khoshknab M, Ghafari S, Nourozi K, Mohammadi E. Confronting the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: a qualitative study of patient experiences. J Nurs Res. 2014;22(4):275–82. doi: 10.1097/jnr.0000000000000058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vosoghi Karkazloo N, Abootalebi Daryasari Gh, Farahani B, Mohammadnezhad E, Sajjadi A. The study of self-care agency in patients with diabetes (Ardabil) Modern Care Journal. 2012;8(4):197–204. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kilic M, Ede H, Yildirim T. The effect of risk factors on the prevalence, awareness and control of hypertension: a multiple logistic regression analysis. Acta Med Mediterr. 2015;31:1285–90. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jaarsma T, Cameron J, Riegel B, Stromberg A. Factors Related to Self-Care in Heart Failure Patients According to the Middle-Range Theory of Self-Care of Chronic Illness: a Literature Update. Curr Heart Fail Rep. 2017;14(2):71–7. doi: 10.1007/s11897-017-0324-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Motl RW, McAuley E, Wynn D, Sandroff B, Suh Y. Physical activity, self-efficacy, and health-related quality of life in persons with multiple sclerosis: analysis of associations between individual-level changes over one year. Qual Life Res. 2013;22(2):253–61. doi: 10.1007/s11136-012-0149-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Özkaya İ, Biçer EK, Yardimci B, Tunckale A. A Preventive Effect of the Mediterranean Diet on Cardiovascular Disease Risk in Type 2 Diabetics (Premedic Trial) Acta Med Mediterr. 2016;32:255. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Soundy A, Benson J, Dawes H, Smith B, Collett J, Meaney A. Understanding hope in patients with Multiple Sclerosis. Physiotherapy. 2012;98(4):344–50. doi: 10.1016/j.physio.2011.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Learmonth Y, Paul L, Miller L, Mattison P, McFadyen A. The effects of a 12-week leisure centre-based, group exercise intervention for people moderately affected with multiple sclerosis: a randomized controlled pilot study. Clin Rehabil. 2012;26(7):579–93. doi: 10.1177/0269215511423946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]