Abstract

Growing evidence has begun to elucidate the contribution of epigenetic mechanisms in the modulation and maintenance of gene expression and behavior. Histone acetylation is one such epigenetic mechanism, which has been shown to profoundly alter gene expression and behaviors. In this review, we begin with an overview of the major epigenetic mechanisms including histones acetylation. We next focus on recent evidence about the influence of environmental stimuli on various motivated behaviors through histone acetylation and highlight how histone deacetylase inhibitors can correct some of the pathologies linked to motivated behaviors including substance abuse, feeding and social attachments. Particularly, we emphasize that the effects of histone deacetylase inhibitors on motivated behaviors are time and context-dependent.

Keywords: Epigenetics, histone deacetylase inhibitors, drug addiction, feeding, social behaviors, maternal behavior, aggression, sexual behaviors, pair bonding

1. Introduction

Motivation is an essential human and animal characteristic that initiates, guides and maintains goal-oriented behaviors, for instance seeking or hunting for food, reproduction, and care of offspring. Motivation is thus a goal-directed action that allows seeking out appetitive stimuli (such as drugs of abuse, palatable foods, and social interactions) or avoiding deterring incentives (such as pain, fear, and stress). In general, behaviors governed by motivation exhibit significant plasticity throughout an individual’s lifetime to permit adaptation to environmental changes that can impact one’s survival or well-being. Clinical and preclinical research have made exciting advances at understanding some of the neural and molecular bases of motivation. Indeed, genes modulate behavior by encoding molecular products, which consequently control brain development and brain function. Therefore, it is important to understand genetic and epigenetic regulation of behaviors, as impaired motivation in patients with psychological disorders, such as schizophrenia, severely weakens functional and cognitive behaviors, ultimately leading to impairments in daily life activities and maintaining social relationships (Volkow, Wang et al. 2011, Fervaha, Zakzanis et al. 2014). In a study investigating the relationship between cognitive function and motivation in transgenic mice, overexpression of dopamine receptors by 15% (Kellendonk, Simpson et al. 2006) -comparable increase observed in patients with schizophrenia (Laruelle 1998)- led to impairments in accuracy and precision to receive a cue-induced reward, and normalizing dopamine receptor expression to control levels rescued accuracy in this test (Avlar, Kahn et al. 2015). This and numerous other studies have thus shown that the mesocorticolimbic dopamine system is a central component in motivational neural circuitry, as this system is activated during motivated behavior and can be “high-jacked” by artificial rewards, i.e. drugs of abuse or highly palatable foods (Calipari, Bagot et al. 2016, Calipari, Juarez et al. 2017, McNamara, Davis et al. 2017, Rakovska, Baranyi et al. 2017). These artificial rewards can induce recurring brain reward system dysfunctions that gradually escalate and result in habitual use and loss of self-restrain (Koob and Le Moal 2001).

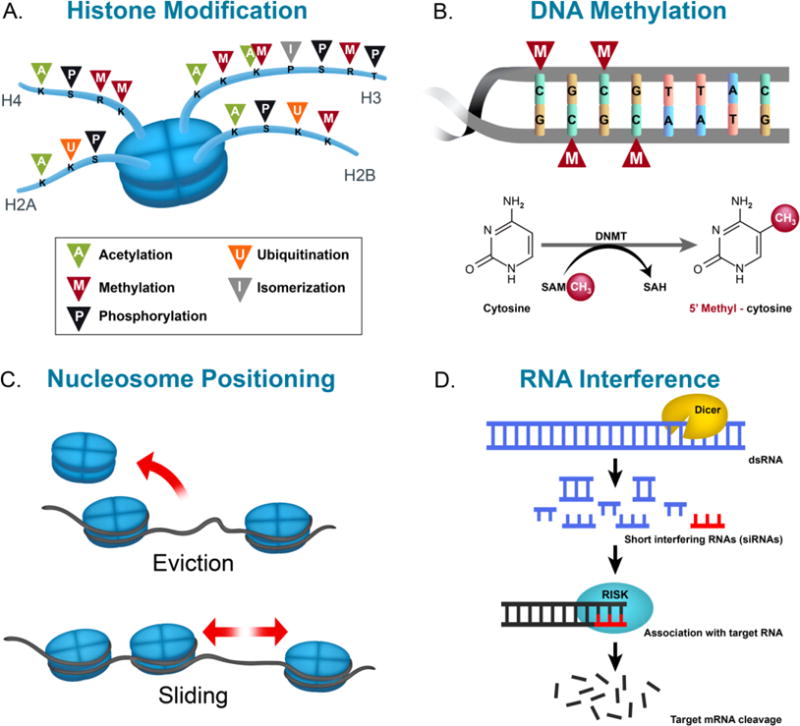

The idea of an “epigenetic landscape” was first coined by Conrad Waddington in the 1940s to describe the creation of a phenotype as a result of elaborate interplays during development between the environment and the genome (Waddington 2012). Recent attempts to establish a common definition have introduced molecular concepts to describe epigenetics as “mitotically and/or meiotically heritable changes in gene function that cannot be explained by changes in DNA sequence” (Allis, Caparros et al. 2007). In this review, we broadly define epigenetics to indicate the mechanisms influencing gene expression leading to changes in phenotype without changing the primary DNA sequence. While illustrated independently in Figure 1 (panels A–D), epigenetic modifications form a multifaceted, collaborative, and cross-regulating system, which is oftentimes reversible, to control gene expression. For example, methyl-CpG binding protein 2 (MeCP2) acts as a bridge between histone methylation on lysine 9 (H3K9me) and DNA methylation, two chromatin-associated gene silencing mechanisms, to reinforce a repressive chromatin state (Fuks, Hurd et al. 2003). Changes in epigenetic patterns were initially thought to only be heritable as epigenetic programming can begin while the fetus is developing in the uterus, but this notion is challenged by the fact that phenotype and epigenetic patterns vary as genetically identical twins become older (Fraga, Ballestar et al. 2005). Additionally, maternal environmental exposures during gestation and preconceptual paternal exposure to environmental stimuli can impact the offspring’s phenotype via alterations of epigenetic marks (Perera and Herbstman 2011, Day, Savani et al. 2016). Epigenetic changes can indeed result in enduring neuroadaptations influencing the organism’s subsequent response to stress, metabolism, or motivated behaviors, thereby altering its vulnerability to the development of diseases. Interestingly, in addition to allowing us to comprehend the link between environmental influences and phenotypical changes, understanding how motivated behaviors are regulated by epigenetic mechanisms can thus offer the opportunity for therapeutic interventions in individuals suffering from neuropsychological disorders such as addiction or social impairments. In this context, a thorough discussion of each of these modes of epigenetic regulation is beyond the scope of this review and will thus only be briefly discussed. Rather, we will focus on histone acetylation and the use of histone deacetylase inhibitors as potential candidates for intervention to regulate dysfunctional motivated behaviors.

Figure 1.

Illustration of epigenetic modifications: histone modification (A), DNA methylation (B), nucleosome positioning (C), and RNA interference (D). Abbreviations: K, S, R, and P – lysine, serine, arginine, and proline residues, respectively, DNMT – DNA methyltransferase, SAM – S-Adenosyl methionine, CH3 – methyl group, SAH – S-Adenosyl homocysteine, dsRNA – double stranded RNA.

1.1 A brief introduction to epigenetic modifications

1.1.1 Nucleosome positioning

Nucleosomes consist of 147 bp of DNA wrapped around eight histone proteins. Each histone octamer is composed of two copies of histones H2A, H2B, H3, and H4, whereas histone H1 is associated to each nucleosome to sustain chromosome assembly. Nucleosome positioning and occupancy are indispensable for governing transcription of genes. While nucleosomes are present at promoters and enhancers, their position is modulated to adapt binding of transcription factors and RNA polymerase machineries by various mechanisms (Kraushaar, Jin et al. 2013). Promoters of transcriptionally active genes generally contain sections of DNA with high nucleosome vacancy at the 5′ and 3′ untranslated region, which allows space for the assembly and disassembly of the transcription machinery. Several groups of large ATP-dependent enzymes are known to control movement, stability, and structure of nucleosomes. These complexes, known as chromatin remodeling complexes, can be classified into four families (SWI/SNF, ISWI, CHD and INO80) that share similar ATPase domains but differ in the composition of their unique subunits (Ho and Crabtree 2010). Chromatin remodelers can induce histone-octamer sliding without unwinding DNA (Saha, Wittmeyer et al. 2006). During DNA repair, chromatin remodelers can replace histone octamers with repair-specific octamers of histone isoforms and modifications in chromatin regions that contain damaged DNA. This histone eviction process, also referred to as nucleosome eviction, can in turn impact the activation of gene promoters (Groth, Rocha et al. 2007).

1.1.2 Histone modifications

Histones are highly alkaline proteins that associate with negatively-charged DNA in the nucleus with the purpose of packaging the DNA into chromatin. Histones can be modified at specific residues by various post-translational modifications (PTM) that include, among others, acetylation, phosphorylation, phosphoacetylation, methylation, ubiquitination, sumoylation, and isomerization predominantly at their N-terminal tails (Grayson and Guidotti 2013). These unique chemical signatures can affect global chromatin assembly, transcription factor binding, or recruitment of transcriptional cofactors. Histone PTMs also permit for chromatin relaxation or compression around genetic loci leading to the promotion or repression of gene transcription. Notably, the majority of histone modifications can occur on the tails of the 4 core histone proteins H2A, H2B, H3, and H4, and can interact with each other, thereby opening a wide array of histone PTM combinations and a complex regulation of gene transcription (Nightingale, Gendreizig et al. 2007, van Attikum and Gasser 2009).

1.1.3 DNA methylation

The most studied epigenetic modification is DNA methylation, a process that consists of a methyl moiety transferred from S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) to the 5′ position of cytosines or adenines, catalyzed by DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) (Jangra, Sriram et al. 2016). Notably, DNA methylation in the mammalian brain can be particularly dynamic, with demethylation or de novo methylation events occurring rapidly following neuronal activity (Guo et al., 2011). Furthermore, the methylation status of cytosine residues at the 5′ position of the cytosine rings in the CG sequence can affect gene transcription in complex ways—depending mostly on the genomic localization and the transcriptional cofactor environment [for additional discussion, please see (Jones 2012, Ghavifekr Fakhr, Farshdousti Hagh et al. 2013, Iurescia, Seripa et al. 2016)]— and has thus been associated with major enduring neuroadaptations underlying higher order brain processes (Meaney and Szyf 2005). Environmental influences, such as drug-seeking behaviors, can moreover induce alterations to DNA methylation. For example, cocaine self-administration, extinction, and reinstatement is associated with an upregulation of striatal and cortical immediate early gene c-Fos expression and with decreased methylation of CpG dinucleotides at its promoter region (Wright, Hollis et al. 2015). Methyl supplementation via chronic l-methionine attenuated drug-primed reinstatement, blocked cocaine-induced c-Fos upregulation, and rescued CpG methylation to controls level (Wright, Hollis et al. 2015).

1.1.4 Noncoding RNA

Non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) act as regulators of gene expression via transcriptional and post-transcriptional mechanisms and modulate epigenetic events through chromatin remodeling (Kaikkonen, Lam et al. 2011). ncRNAs can be short, less than 200 bp long and classified as small ncRNA (sncRNA), while longer transcripts are termed as long ncRNA (lncRNA) (Peschansky and Wahlestedt 2014). Small ncRNA classes are grouped under the term RNA interference (RNAi), otherwise known as a mechanism by which short double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) is utilized for sequence-specific alteration of gene expression, by binding to either the coding or promoter region of the target mRNA (Tollefsbol 2011). These small ncRNAs are comprised of microRNA (miRNA), small interfering RNA (siRNA), and piwi RNA (piRNA). miRNA induces target mRNA degradation or repress protein translation (Figure 1). Recent findings have reported miRNAs as novel biomarkers of cancer, screens for insulin deficiency, and as a possible treatment for drug addiction (Zhang, Li et al. 2014, Liu, Li et al. 2015). siRNA leads to mRNA degradation in the cytoplasm and enter the nucleus for chromatin modification and siRNA screening has allowed for effective identification of novel positive and negative regulators of insulin promoter activity and insulin secretion in pancreatic β-cells (Ku, Pappalardo et al. 2012). Intravenous injection of opioid receptor μ (MOR) siRNA-containing brain-specific targeted exosomes prevents morphine relapse by downregulating MOR in mice, which is a primary target for opioid analgesics used clinically and involved in the reinforcing effects and addiction to opiates (Liu, Li et al. 2015). piRNA targets invasive transposon transcripts in germlines, thus acting as guardians of the genome (Ishizu, Siomi et al. 2012).

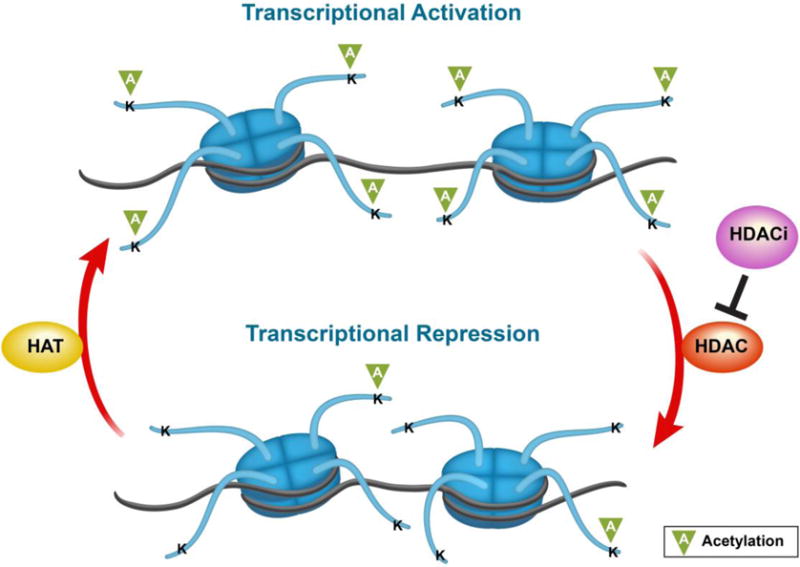

2. Histone acetylation

Acetylation of histone tail lysine residues is known to occur in different organisms for the regulation of diverse nuclear and cytoplasmic processes. Considered a very common PTM that targets larger macromolecular complexes, acetylation of lysine residues can occur in over 1,750 proteins that together comprise 3,600 lysine acetylation sites (Choudhary, Kumar et al. 2009). Importantly, this acetylated state is controlled through the opposing activities of histone acetyltransferases (HATs) and histone deacetylases (HDACs) (Figure 2). HATs neutralize the positively charged ε-amino group of specific lysine residues by transferring an acetate group from acetyl-CoA to the lysine residue, thereby enhancing their acetylation, and thus rendering DNA more accessible by decreasing binding affinity between the histone tail and DNA (Shogren-Knaak, Ishii et al. 2006) otherwise the positive lysine binds to negatively charged DNA in the absence of the acetyl group. HDACs hydrolyze the acetyl moiety, i.e. remove the acetyl groups, and reduce DNA accessibility for transcription to occur. Through the balance between HAT and HDAC activities, the levels of histone acetylation are thus regulated in a highly dynamic manner that represent a unique molecular framework for the integration of environmental stimulations on gene expression. Indeed, although proteins carrying HAT or HDAC activities have non-histone targets, HATs generally favor DNA availability to transcription factors, thereby promoting DNA transcription at a given locus, whereas HDACs generally act as transcriptional corepressors by deacetylating histone core proteins, resulting in chromatin condensation and the inhibition of transcriptional activating complexes (Haery, Thompson et al. 2015). In this context, HATs and HDACs represent valuable candidates for pharmacological intervention at the interface of gene x environment interactions. Notably, because the literature on HAT inhibitors (HATi) and their involvement in regulating behaviors remains sparse as of date, we will focus the remainder of our discussion on HDACs and HDAC inhibitors (HDACi) and their role in the regulation of motivated behaviors.

Figure 2.

Illustration of chromatin conformation according to HAT/HDAC balance. Abbreviations: K – lysine residue, HAT – histone acetylase, HDAC – histone deacetylase, and HDACi – histone deacetylase inhibitor.

2.1 Classification and localization of HDACs

Presently, 18 mammalian HDACs are recognized are and divided into two protein families with HDAC activity, the “classical” zinc-dependent family and the nicotinamide-adenine-dinucleotide (NAD+)-dependent sirtuins (Table 1). Phylogenetic classes further segment the zinc-dependent HDAC family into classes I, II, and IV in which class I is composed of HDACs 1, 2, 3, and 8, class II is composed of HDACs 4–7, 9, and 10, and class IV is composed of HDAC11. Class III NAD+-dependent sirtuins are composed of 7 isoforms, SIRT1-7. The function and activity of HDACs vary depending on their structure and intracellular localization.

Table 1.

Target selectivity of histone deacetylase inhibitors and in vivo potency. Names in parenthesis indicate abbreviated HDACi or alternative HDACi name.

| HDACi Family | HDACi | HDAC Class Specificity | HDAC Isoform Selectivity | In Vivo Potency | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydroxamic Acids | Trichostatin A (TSA) | Classes I, II, & IV | Isoform-nonselective | nM-μM | (Scholz, Weinert et al. 2015) | |

| Vorinostat (SAHA) | Classes I, II, & IV | Isoform-nonselective | nM | (Schroeder, Lewis et al. 2013) | ||

| Belinostat (PXD101) | Classes I & II | Isoform-nonselective | μM | (Scholz, Weinert et al. 2015) | ||

| Panobinostat (LBH589) | Classes I & II | Isoform-nonselective | μM | (Scholz, Weinert et al. 2015) | ||

| Givinostat (ITF2357) | Classes I & II | Isoform-nonselective | nM | (Finazzi, Vannucchi et al. 2013) | ||

| Abexinostat (PCI 24781) | Classes I & II | Isoform-nonselective | nM | (Scholz, Weinert et al. 2015) | ||

| Pracinostat (SB939) | Classes I & II | Isoform-nonselective | μM | (Novotny-Diermayr, Hart et al. 2012) | ||

| Resminostat (4SC-201) | Pan inhibitor | HDACs 1, 3, & 6 | μM | (Mandl-Weber, Meinel et al. 2010) | ||

| MC-1568 | Class IIa | HDACs 4 & 5 | μM | (Nebbioso, Manzo et al. 2009) | ||

| Tubacin | Class IIa | HDAC6 | μM | (Lin, Nazif et al. 2015) | ||

| PCI-34051 | Class I | HDAC8 | μM | (Rettig, Koeneke et al. 2015) | ||

|

| ||||||

| Aliphalic Acids | Valproic Acid (VPA) | Classes I & IIa | HDACs 1 & 2 | μM-mM | (Gottlicher, Minucci et al. 2001, Phiel, Zhang et al. 2001) | |

| Sodium Butyrate (NaB) | Classes I & IIa (not HDAC6) | Isoform- nonselective | mM | (Hubbert, Guardiola et al. 2002) | ||

| Phenybutyrate (PB) | Classes I & IIa | Isoform- nonselective | mM | (Leng, Liang et al. 2008) | ||

|

| ||||||

| Cyclic Peptides | Romidepsin (FK228) | Class I & II | HDACs 1 & 2 | nM | (Frumm, Fan et al. 2013) | |

| Apicidin | Class I | HDACs 2 & 3 | nM | (Khan, Jeffers et al. 2008) | ||

|

| ||||||

| Benzamides | Entinostat (MS-275) | Class I | HDACs 1 | nM-μM | (Scholz, Weinert et al. 2015) | |

| Mocetinostat (MGCD-0103) | Classes I & IV | HDACs 1 | μM | (Fournel, Bonfils et al. 2008) | ||

| Tacedinaline (CI-994) | Class I | HDACs 1 & 2 | μM | (Scholz, Weinert et al. 2015) | ||

| RGFP136 | Class I | HDAC3 | μM | (Malvaez, McQuown et al. 2013) | ||

|

| ||||||

| Other (not HDACi) | Nicotinamide | Class III | SIRTs 1–4, 5, & 6 | μM | ||

| Suramin | Class III | SIRTs 1, 2, & 5 | μM | |||

| Sirtinol | Class III | SIRT1 | μM | (Hu, Jing et al. 2014) | ||

| Tenovin | Class III | SIRT1 & 2 | μM | |||

| AGK2 | Class III | SIRT1–3 | μM | |||

Members of the HDAC classes I, II, and IV closely share sequence similarity and require Zn2+ for deacetylase activity. Class I HDACs localize within the nucleus, apart from HDAC8 which has the ability to transport into the cytoplasm (Bjerling, Silverstein et al. 2002). Larger proteins compose class II HDACs and shuttle between the nucleus and cytoplasm (Bjerling, Silverstein et al. 2002). The sequence similarity of HDAC11 to class I, II, and III HDACs is low and is therefore characterized within its own HDAC class (Gao, Cueto et al. 2002). The members of the HDAC class III do not have sequence similarity to the other HDAC classes as they require NAD+ as a cofactor and deacetylate different sets of substrate proteins (Herskovits and Guarente 2014). SIRT1 and SIRT2 localize in both the nucleus and the cytoplasm (Jin, Yan et al. 2007). SIRT1 may shuttle from the nucleus to the cytoplasm during neuronal differentiation, neurite outgrowth, tumor progression, and apoptosis. SIRT2 can deacetylate tubulin, and shuttle from the nucleus to the cytoplasm during cell cycle progression, cancer, and bacterial infection. SIRT3, SIRT4, and SIRT5 are found in the mitochondria and each have unique enzymatic activities. SIRT6 and SIRT7 are localized in the nucleus and the nucleolus, respectively. While SIRT7 requires NAD+ binding at its catalytic domain, there have been opposing reports regarding its deacetylase activity against the common HDAC substrate p53 (Michishita, Park et al. 2005, Kiran, Anwar et al. 2015).

Few studies have examined HDAC expression in the brain, specifically in monoaminergic and in neuropeptidergic neurons. These neuron subtypes modulate various behaviors such as feeding, drug addiction, and social behaviors (Takase, Oda et al. 2013). The ventral tegmental area (VTA) contains dopamine neurons that play an important part in the reward system and regulate feeding, drug addiction, and social behaviors (Young, Gobrogge et al. 2011). In the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus (AR), orexigenic neurons, containing neuropeptide Y (NPY) and agouti-related peptide (AgRP), and anorexigenic neurons, containing pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC), largely regulate feeding behaviors (Morton, Cummings et al. 2006). The hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus (PVN) contains neurons that produce oxytocin and vasopressin, neuropeptides critical in social behaviors (Donaldson and Young 2008). Takase and colleagues (2013) revealed that expression patterns of HDACs 1–3, 5–7, 9 and 11 were comparable among monoaminergic and neuropeptidergic neurons in which immunoreactive puncta was found in CRH, oxytocin, and vasopressin neurons of the PVN; orexin neurons of the lateral hypothalamic area (LHA); AgRP and POMC neurons of the ARC; histamine neurons of the tuberomammillary nucleus; dopamine neurons of the VTA; serotonin neurons of the dorsal raphe (DR); and in the noradrenaline neurons of the locus coeruleus. Interestingly, HDACs 4, 8, and 10 expression varied amongst the different neuronal groups. HDAC4 immunoreactivity, for instance, was not detected in histamine, AgRP, or POMC neurons, whereas, only a minute population of oxytocin and histamine neurons exhibited HDAC8 immunoreactivity. Similarly, HDAC10 expression was only found in AgRP, POMC, dopamine, and noradrenaline neurons (Takase, Oda et al. 2013), whereas HDAC6 but not HDAC4 or HDAC10 mRNA and protein signal in the mouse brain is enriched in serotoninergic neurons of the dorsal raphe (Espallergues, Teegarden et al. 2012, Fukada, Hanai et al. 2012). Altogether, HDACs expression in the central nervous system therefore exhibit a substantial structure and neuronal subpopulation specificity that further supports an isoform specificity in their involvement in motivated behaviors. Notably, this observation is of particular interest as it provides an important layer of specificity to the actions of HDACi in the central nervous system.

2.2 Overview and Classification of Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors

HDACi have emerged as promising cancer therapeutic agents as atypical patterns of histone modifications are involved in cancer development. HDACi have the potential to target non-histone proteins to inhibit cell proliferation, stimulate cell cycle arrest, inhibit angiogenesis, and induce senescence of cancer cells (Bolden, Peart et al. 2006, Peng and Seto 2011). Presently, HDACi are being used as stand-alone therapies or in combination with other agents, chemotherapies, radiation therapies, or immune checkpoint therapies in numerous clinical cancer trials (Zain and O’Connor 2010, Mazzone, Zwergel et al. 2017, Qiu, Xiao et al. 2017). However, clinical results do not coincide with preclinical work in terms of efficacy against solid tumors and off-target toxicity with negative side-effects (Subramanian, Bates et al. 2010). Approaches to surmount these setbacks involve localized administration to sidestep systemic toxicity and the formation of new isoform selective HDACi (Gryder, Sodji et al. 2012).

The four main classes of HDACi are structurally composed of hydroxamic acids, cyclic peptides, benzamides, and aliphatic acids, with their inhibition potency largely dependent on HDAC specificity (Table 1). To name a few, hydroxamic-acid based HDACi include Vorinostat (SAHA), Trichostatin A (TSA), Belinostat, and Abexinostat. These HDACi can block at least two HDAC classes, accordingly dubbed as pan-HDAC inhibitors, and are active at nanomolar concentrations. Through the application of X-ray crystallography, hydroxamic-acid containing HDAC inhibitors have been postulated to interact with the catalytic site of HDACs, thereby blocking substrate access to the active zinc ion at its base (Finnin, Donigian et al. 1999). Cyclic peptides, such as Romidepsin, consist of the most structurally complex class of HDACi and exhibit inhibitory activity on HDAC classes at low nanomolar ranges (Khan, Jeffers et al. 2008). While the HDACi that belong to the benzamide class, such as MS-275, are less potent by showing inhibition at micromolar concentrations they do exhibit the advantage of HDAC isoform specificity (Table 1). Lastly, aliphatic acids are the least potent HDACi (valproic acid and butyric acid) as they possess millimolar levels of activity, yet show HDAC class specificity (Lee, Choi et al. 2001). The Class III HDACs, whose seven members are NAD+-dependent enzymes are not inhibited by the five conventional HDACi classes (Table 1) will consequently not be discussed. Notably, despite the wide existing array of HDACi, the currently available inhibitors generally lack selectivity as isoform-selective inhibitors are described for only a few HDACs. While this obstacle can be addressed in preclinical studies with an RNAi-based strategy, it implies, in a clinical environment, the consideration of broad range inhibitors with higher risks for side effects. Nonetheless, it is important to also take into account the structure and neuronal subpopulation specificity in the expression pattern of HDACs throughout the central nervous system, which can substantially participate in lowering the risk for adverse side-effects for HDACi.

3. Motivated behaviors

3.1 Effects of HDACi on drug-seeking behavior

There is a growing consensus that neural and behavioral plasticity play a role in addiction, subsequently resulting in enduring molecular changes in central brain regions involved in reward and ensued by life-long behavioral impairments (Nestler 2014, Walker, Cates et al. 2015). Likewise, internal and external risk factors such as prenatal exposure to drugs or early life stressful experiences can prime an individual for drug dependency, revealing the importance of lasting neuroadaptations in influencing vulnerability to addiction (Pena, Bagot et al. 2014). In this context, it is thus important to note that the neurochemical mechanisms regulating long-term associative memories in brain areas receiving midbrain dopaminergic inputs, such as the striatum and prefrontal cortex, are thought to influence persistent drug use (Hyman, Malenka et al. 2006). Notably, the transcriptional alterations underlying enduring neuroadaptations that arise due to chronic drug usage have been recently reported as being regulated by epigenetic events, with the most investigated chromatin modification in animal models of addiction being histone acetylation (Martin, Jayanthi et al. 2012, Alaux-Cantin, Warnault et al. 2013, Huang, Levine et al. 2014, Nestler 2014). In addition to uncovering a new perspective on the lasting neuroadaptations underlying addiction-related behaviors, this opens a novel strategy for therapeutical intervention in which epigenetic drugs such as HDACi could possibly play a critical role in reducing drug seeking behaviors and withdrawal symptoms. In this section, we will thus focus on the effects of HDACi on the chronic use of three heavily studied drugs of abuse, cocaine, opioids, and alcohol.

3.1.1 Cocaine

Chronic cocaine use is associated with enduring changes of the neural reward circuitry that can ultimately lead to addiction. As the reward circuitry adapts to excess release of endogenous dopamine with chronic cocaine use, the body begins to develop drug tolerance (Adinoff 2004, Kalivas 2007, Koob and Simon 2009). Consequently, chronic cocaine users feel the need to increase the concentration and frequency of self-administration to achieve the euphoria experienced with initial use and to avoid withdrawal symptoms. So far, there is virtually no FDA-approved treatment for cocaine addiction but extensive translational research aims to uncover potential therapeutics. HDACi have received great attention among potential treatments for addiction to cocaine. In rats, chronic cocaine administration induces histone H3 hyperacetylation at the FosB, BDNF, and Cdk5 promoters in the striatum. This histone hyperacetylation is maintained for at least 7 days after the final cocaine injection (Kumar, Choi et al. 2005), and thus illustrates the proposed role for epigenetic mechanisms, and histone acetylation in particular, as molecular substrates for the enduring effects of chronic cocaine exposure. At the behavioral level, dopamine receptor 1 agonism and sodium butyrate (NaB) co-treatment preceding cocaine exposure augment cocaine-induced locomotor activity and conditioned place preference (CPP) with an associated increase in striatal H3 phosphoacetylation and H3 deacetylation at promoter regions of tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) and BDNF (Schroeder, Penta et al. 2008). Histone H3 phosphoacetylation is the arrangement of acetylation and phosphorylation, known to have synergistic effects on overall chromosome condensation. Notably, NaB treatment alone does not affect striatal histone H3 phosphoacetylation but requires simultaneous activation of dopamine D1 receptors (Schroeder et al., 2008). Furthermore, HDACi’s effects on chronic cocaine exposure are highly dose-dependent when given concurrently with cocaine. Indeed, a high, systemic dose of NaB (Table 2) facilitating histone H3K14 and H4K8 acetylation in the mouse hippocampus and H3K14 in the nucleus accumbens, increases cocaine CPP acquisition while impairing extinction (Itzhak, Liddie et al. 2013, Raybuck, McCleery et al. 2013). A low dose, conversely, enables extinction of cocaine place preference (Raybuck, McCleery et al. 2013). While HDACi treatment post cocaine exposure fails to decrease self-administration (Wang, Lv et al. 2010), Romieu et al (2008) showed that it is necessary to co-administer a low dose of TSA to significantly reduce cocaine self-administration. As summarized in Table 2, these observations indicate that the attenuating effects of HDAC inhibition on cocaine use and preference are highly dose- and time-dependent, with only low HDACi doses when given concomitantly with cocaine decreasing self-administration and enhancing extinction. Altogether, these data do support the modulation of neuroadaptations resulting from chronic cocaine exposure by HDAC inhibition. In line with the complexity of such processes, however, the effects of HDACi are highly dependent on experimental factors such as dose or timing of injection, which thus represent critical factors requiring to be taken into consideration in an eventual clinical context.

Table 2.

HDACi’s mediating behavioral responses to cocaine. The behavioral outcome for each HDACi during pre-treatment, concurrent, or post-treatment are listed, along with changes of histone acetylation and gene expression changes per brain regions. Arrows indicate an increase (

) or decrease (

) or decrease (

). Abbreviations: i.p. – intraperitoneal, i.v. – intravenous, PRE – pretreatment, CON – concurrent treatment with drug, POST – post-treatment, CPP – conditioned place preference, NaB – sodium butyrate, TSA – trichostatin A, i.p. – intraperitoneal, i.v. – intravenous, NAcc – nucleus accumbens, CPP – conditioned place preference, Vent Mid – ventral midbrain, Hipp – hippocampus, Infr Ctx – infralimbic cortex, TH – tyrosine hydroxylase, BDNF – brain-derived neurotrophic factor, Cbp – CREB binding protein, Cdk5 – cyclin-dependent kinase 5, CaMKIIα – calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase type II alpha, GluR2 – glutamate receptor 2, NR2A – NMDA receptor subunit 2A, NR2B – NMDA receptor subunit 2B.

). Abbreviations: i.p. – intraperitoneal, i.v. – intravenous, PRE – pretreatment, CON – concurrent treatment with drug, POST – post-treatment, CPP – conditioned place preference, NaB – sodium butyrate, TSA – trichostatin A, i.p. – intraperitoneal, i.v. – intravenous, NAcc – nucleus accumbens, CPP – conditioned place preference, Vent Mid – ventral midbrain, Hipp – hippocampus, Infr Ctx – infralimbic cortex, TH – tyrosine hydroxylase, BDNF – brain-derived neurotrophic factor, Cbp – CREB binding protein, Cdk5 – cyclin-dependent kinase 5, CaMKIIα – calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase type II alpha, GluR2 – glutamate receptor 2, NR2A – NMDA receptor subunit 2A, NR2B – NMDA receptor subunit 2B.

| HDACi | Dose (mg/kg) | Time of Exposure with Drug | Route of Admin. | Behavioral Effect | Region Effects | Histone Effects | Gene Specific Effects | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NaB | 100 | PRE | i.p. |

locomotor sensitization locomotor sensitization |

Striatum |

pAcH3 pAcH3 |

cFos cFos |

(Kumar, Choi et al. 2005) |

| 100 | PRE | i.p. |

locomotor sensitization locomotor sensitization |

Striatum |

H3ac H3ac |

TH TH |

(Schroeder, Penta et al. 2008) | |

| Vent Mid |

H4ac H4ac |

BDNF BDNF |

||||||

CPP acquisition CPP acquisition | ||||||||

| 400 | CON | i.v. |

Self-administration Self-administration |

(Sun, Wang et al. 2008) | ||||

| 1200 | CON | i.p. |

CPP acquisition CPP acquisition CPP extinction CPP extinction Reinstatement Reinstatement |

NAcc |

H3K14ac H3K14ac |

(Malvaez, Sanchis-Segura et al. 2010) | ||

| 1200 | CON | i.p. |

CPP acquisition CPP acquisition CPP extinction CPP extinction |

Hipp |

H3K14ac& H4K8ac (Cocaine naive) H3K14ac& H4K8ac (Cocaine naive) |

(Itzhak, Liddie et al. 2013) | ||

| 1200 | CON | i.p. |

CPP acquisition CPP acquisition CPP extinction CPP extinction |

Infr Ctx & NAcc |

H3K14ac H3K14ac |

(Raybuck, McCleery et al. 2013) | ||

| 300 | CON | i.p. |

CPP extinction CPP extinction |

|||||

| TSA | 2 | PRE | i.p. |

CPP acquisition CPP acquisition |

Striatum |

pAcH3 pAcH3 |

cFos cFos |

(Kumar, Choi et al. 2005) |

| 0.3 | CON | i.v. |

Self-administration Self-administration Locomotor sensitization Locomotor sensitization |

(Romieu, Host et al. 2008) | ||||

| 0.75 | POST | Intra-NAcc (shell) |

Self-administration Self-administration |

NAcc shell, NAcc core, & mPFC |

H3ac H3ac |

(NAcc shell) Cbp, BDNF-P2, BDNF-P3, FosB, Cdk5, CaMKIIα, GluR2, NR2A, & NR2B (NAcc shell) Cbp, BDNF-P2, BDNF-P3, FosB, Cdk5, CaMKIIα, GluR2, NR2A, & NR2B |

(Wang, Lv et al. 2010) | |

| SAHA | 0.75 | POST | Intra-NAcc (shell) |

Self-administration Self-administration |

NAcc shell, NAcc core, & mPFC |

H3ac H3ac |

(Wang, Lv et al. 2010) | |

| MS-275 | CON | Intra-NAcc (shell) |

Locomotor sensitization Locomotor sensitization |

NAcc |

H3K14ac, H3K9ac, H3K9me2, & H3K9me3 H3K14ac, H3K9ac, H3K9me2, & H3K9me3 |

G9a, GLP, & SUV39H1 G9a, GLP, & SUV39H1 |

(Kennedy, Feng et al. 2013) |

3.1.2 Opioids

Although the most efficient pain relieving pharmaceuticals are opioid analgesics, repeated use can lead to dependence, thus resulting in the necessity to understand the neurobiological basis of opioid addiction (Fields and Margolis 2015). Opioids, such as heroin and morphine, elicit changes in the reward circuitry and alter autonomic processes controlled by the brainstem. The neuroadaptations associated with chronic opioid intake have been linked to specific regulations of histone acetylation in the brain. Indeed, activation of the δ-opioid receptor prompts nuclear translocation of β-arrestin 1, a cytosolic regulator and scaffold of GPCR signaling, to the nucleus and is selectively augmented at p27 and c-fos promoters. Recruitment of the HAT p300 ensues and is subsequently followed by increased local histone H4 acetylation and transcription of p27 and c-fos (Kang, Shi et al. 2005). Recurring morphine exposure is sufficient to induce behavioral sensitization and enhance acetylation of H3K14 in the nucleus accumbens (NAcc) and basolateral amygdala (BLA) (Jing, Luo et al. 2011, Sheng, Lv et al. 2011, Wang, Lai et al. 2015, Chen, Xu et al. 2016). Notably, sub-effective doses of NaB and VPA, that do not affect locomotor activity, can increase acetylated histone H3 levels in the NAcc, inhibit acute morphine-induced hyperactivity, and reduce behavioral sensitization (Jing, Luo et al. 2011). Moreover, intra-NAcc TSA administration increases histone H3 phosphoacetylation (P-AcH3) in the NAcc and augments heroin-induced conditioned place preference (CPP) while TSA alone does not induce place preference or aversion (Sheng, Lv et al. 2011). Additionally, heroin-induced P-AcH3 were specific to the NAcc as changes induced by heroin or TSA were not observed in the medial prefrontal cortex, another critical area affected by drugs of abuse (Sheng, Lv et al. 2011). Likewise, systemic and central administration of NaB enhances heroin- seeking and increases the expression of acetylated H3K18, H4K5, and H4K8 (Chen, Xu et al. 2016). Furthermore, intra-BLA infusions of TSA in rat significantly increase acquisition and expression of morphine-induced CPP (Table 3), but facilitate its extinction and reduces subsequent reinstatement, with a concomitant hyperacetylation of H3K14 and upregulation of BDNF, ΔFosB, and CREB expression (Wang, Lai et al. 2015), indicating that HDAC inhibition can affect the neuroadaptations underlying several stages of morphine-induced CPP. In addition, HDAC activity in the ventrolateral orbital cortex (VLO) is another target of morphine-induced behavioral sensitization as intra-VLO TSA injection significantly enhances morphine-induced sensitization and upregulates protein levels of pERK, AceH3K9, and BDNF (Wei, Zhu et al. 2016). It is important to note that the timing of HDACi administration is important for inhibiting opioid- induced behavioral sensitization, as co-administration of opioids with HDACi augmented opioid-induced CPP-acquisition and reinstatement (Chen, Xu et al. 2016, Sheng, Lv et al. 2011, Wei, Zhu et al. 2016), while HDACi treatment prior to opioid exposure reduced hyperactivity, increased CPP extinction, and reduced CPP reinstatement (Jing, Luo et al. 2011, Wang, Lai et al. 2015).

Table 3.

HDACi’s mediating behavioral responses to heroin or morphine. The behavioral outcome for each HDACi during pre-treatment, concurrent, or post-treatment are listed, along with changes of histone acetylation and gene expression changes per brain regions. Arrows indicate an increase (

) or decrease (

) or decrease (

). Abbreviations:: i.p. - intraperitoneal, PRE - pretreatment, CON - concurrent treatment with drug, POST - post-treatment, CPP - conditioned place preference, NaB - sodium butyrate, TSA - trichostatin A, NAcc - nucleus accumbens, BLA - basolateral amygdala, VLO - ventrolateral orbital cortex, BDNF - brain-derived neurotrophic factor, Cbp - CREB binding protein, pERK - phosphor ERK.

). Abbreviations:: i.p. - intraperitoneal, PRE - pretreatment, CON - concurrent treatment with drug, POST - post-treatment, CPP - conditioned place preference, NaB - sodium butyrate, TSA - trichostatin A, NAcc - nucleus accumbens, BLA - basolateral amygdala, VLO - ventrolateral orbital cortex, BDNF - brain-derived neurotrophic factor, Cbp - CREB binding protein, pERK - phosphor ERK.

| HDACi | Dose (mg/mg) | Route of Admin. | Time of Exposure with Drug | Behavioral Effect | Region Effects | Histone Effects | Gene Specific Effects | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NaB | 40, 80, or 160 | i.p. | PRE |

Hyperactivity Hyperactivity |

NAcc |

AcH3 AcH3 |

(Jing, Luo et al. 2011) | |

| Intra-NAcc | CON |

Reinstatement Reinstatement |

NAcc |

AcH3K18, AcH4K5, and AcH4K8 AcH3K18, AcH4K5, and AcH4K8 |

(Chen, Xu et al. 2016) | |||

| Intra-NAcc | CON |

CPP acquisition CPP acquisition |

NAcc |

pAcH3 pAcH3 |

(Sheng, Lv et al. 2011) | |||

| TSA | Intra-BLA | PRE |

CPP acquisition CPP acquisition CPP extinction CPP extinction  Reinstatement Reinstatement |

BLA |

AcH3K14 AcH3K14 |

BDNF, ΔFosB, and CREB BDNF, ΔFosB, and CREB |

(Wang, Lai et al. 2015) | |

| Intra-VLO | CON |

sensitization sensitization |

VLO |

AceH3K9 AceH3K9 |

pERK and BDNF pERK and BDNF |

(Wei, Zhu et al. 2016) |

3.1.3 Alcohol

Strikingly, 4% of worldwide deaths are linked to alcohol dependence (Collins, Patel et al. 2011), which is the second most detrimental psychiatric disorder according to the World Health Organization (WHO). Clinical studies have shown that individuals with alcohol dependence exhibit alterations in methylated DNA and DNMT levels within various cell classes within the cortex and amygdala (Ponomarev, Wang et al. 2012), suggesting an epigenetic basis for alcohol dependence. Unfortunately, existing pharmacotherapies are very limited with modest effectiveness in treating physical dependence and relapse (Krishnan-Sarin, O’Malley et al. 2008). Translational research is paving the way for outlining the molecular mechanisms that drive genetic changes and behavioral impairments triggered by alcohol abuse. For example, ethanol-induced hyperacetylation of histone H3K9 was first revealed through primary cell culture (Park, Miller et al. 2003). At present, the effects of alcohol on gene expression in the mouse and rat brain have been well documented, specifically within the prefrontal cortex, nucleus accumbens, hippocampus, and the amygdala (Abernathy, Chandler et al. 2010, Contet 2012). Interestingly, patterns of histone acetylation depend on the alcohol treatment paradigm, the timing of exposure to alcohol, and withdrawal period from alcohol (Table 4). Chronic alcohol intake enhances anxiety-like responses that are associated with HDAC hypoactivity, attenuates acetylation of histones H3 and H4, and represses CBP and NPY transcription in the central and medial amygdala. Notably, the development of alcohol withdrawal-related anxiety and deficiency of NPY expression in the central and medial amygdala was rescued by TSA treatment, suggesting that amygdaloid histone acetylation is involved in alcohol tolerance and dependence and that certain HDACi may be potential therapeutic agents in treating alcohol withdrawal symptoms (Pandey, Ugale et al. 2008).

Table 4.

HDACi’s mediating behavioral re sponses to alcohol. The behavioral outcome for each HDACi during pre-treatment or concurrent treatment are listed, along with changes of histone acetylation and gene expression changes per brain regions. Arrows indicate an increase (

) or decrease (

) or decrease (

). Abbreviations: i.p. - intraperitoneal, i.c.v. - intracerebroventricualr, PRE - pretreatment, CON - concurrent treatment with drug, TSA - trichostatin A, PFC - prefrontal cortex, Hippo - hippocampus, Amyg - amygdala, NAcc - nucleus accumbens, DS - dorsal striatum, NR2B - NMDA receptor subunit 2B, BDNF - brain-derived neurotrophic factor.

). Abbreviations: i.p. - intraperitoneal, i.c.v. - intracerebroventricualr, PRE - pretreatment, CON - concurrent treatment with drug, TSA - trichostatin A, PFC - prefrontal cortex, Hippo - hippocampus, Amyg - amygdala, NAcc - nucleus accumbens, DS - dorsal striatum, NR2B - NMDA receptor subunit 2B, BDNF - brain-derived neurotrophic factor.

| HDACi | Dose (mg/mg) | Route of Admin. | Time of Exposure with Drug | Behavioral Effect | Region Effects | Histone Effects | Gene Specific Effects | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TSA | i.c.v. or i.p. | PRE |

Self-administration Self-administration |

PFC |

AceH3K9 AceH3K9 |

NR2B NR2B |

(Qiang, Li et al. 2014) | |

| CON | Hippo |

AceH3 AceH3 |

BDNF BDNF |

(Sakharkar, Vetreno et al. 2016) | ||||

| 2 | i.p. | CON |

Self-administration Self-administration Anxiety-like behaviors Anxiety-like behaviors |

Amyg |

AceH3 AceH3 |

BDNF& Arc BDNF& Arc |

(Pandey, Ugale et al. 2008) | |

| SAHA, TSA, or MS-275 | i.p. | CON |

Self-administration Self-administration |

NAcc |

AcH4 AcH4 |

(Warnault, Darcq et al. 2013) | ||

| MS-275 | i.c.v. | PRE |

Self-administration Self-administration |

NAcc and DS |

AcH4 AcH4 |

(Jeanblanc, Lemoine et al. 2015) |

The timing of HDACi administration is also critical for controlling alcohol seeking behaviors, since administration of HDACi before or after voluntary ethanol exposure can have opposing molecular and behavioral consequences. In mice and rats, repeated chronic intermittent ethanol (CIE) exposure with repeated withdrawal experiences increase subsequent ethanol intake yet the mechanisms that facilitate motivation for continued ethanol consumption are not fully understood. CIE exposure causes DNA demethylation and increased histone acetylation at the promoter region of the NR2B gene in the prefrontal cortex of mice. Administration of either DNMT inhibitor 5-azacytidine (5′AZA) or TSA 30 minutes prior to CIE exposure can likewise reduce DNA methylation and increase histone acetylation in the NR2B promoter to reinforce ethanol drinking 5 days post-CIE exposure (Qiang, Li et al. 2014). HDACi effects on alcohol consumption are highly dependent on the experimental paradigm, however, as opposite effects are observed under binge-like drinking conditions. Indeed, while excessive alcohol drinking increases DNMT1 levels and reduces histone H4 acetylation in the mouse and rat NAcc, binge-like alcohol drinking in mice is reduced by systemic administration of 5′AZA or the HDACi TSA, SAHA, or MS-275 (Warnault, Darcq et al. 2013). In self-administration paradigms, the HDACi SAHA reduces alcohol seeking behavior in rats (Warnault, Darcq et al. 2013), whereas central administration of the class I-selective HDACi MS-275 decreases ethanol self-administration by 75%, motivation to consume alcohol by 25%, and reduces relapse by 50%, alongside histone H4 hyperacetylation in the NAcc and dorsolateral striatum (Jeanblanc, Lemoine et al. 2015). HDACi can control the level of alcohol seeking depending on the timing of administration. Systemic or central TSA treatment 30 minutes prior to CIE increases alcohol self-administration (Qiang, Li et al. 2014), while MS-275 treatment 3 hours prior to self-administration sessions reliably reduces alcohol intake (Jeanblanc, Lemoine et al. 2015). These findings thus suggest that DNMT and HDAC inhibitors can control the level of alcohol seeking and consumption behaviors in adulthood, depending whether they are co-administered prior to or after alcohol intake.

It is well known that early exposure to alcohol (i.e. during adolescence) is a significant predictor of alcohol dependence during adulthood (Grant 1998). CIE exposure during adolescence induced anxiety-like behaviors with a concomitant increase of HDAC2 and HDAC4 levels in the amygdala, reduced CeA and MeA acetylated H3K9 only 24 hours after the last adolescent ethanol exposure (Pandey, Ugale et al. 2008). Notably, enhanced HDAC activity and reduced histone acetylation endured through adulthood, with decreased BDNF-Arc expression in the amygdala, suggesting that epigenetic mechanisms underlie long-term effects of ethanol exposure during adolescence. Nevertheless, TSA administration in adulthood reversed the adolescent alcohol-driven effects: H3 acetylation deficits at the BDNF and Arc genes were normalized to control levels, whereas anxiety-like behaviors and ethanol self-administration were attenuated (Pandey, Ugale et al. 2008). Moreover, TSA treatment also rescues the down-regulation of BDNF expression in the hippocampus observed in adulthood following adolescent alcohol exposure (Sakharkar, Vetreno et al. 2016), which indicates that the rescuing effects of HDAC inhibition on the long-term effects of alcohol exposure are widespread. Although it would be valuable to examine the downstream targets of BDNF within the amygdala and NAcc to better understand the related molecular underpinnings, these observations altogether support the use of HDACi to revert the long-term effects of alcohol exposure.

3.2. Effects of HDACi on feeding behaviors

The control of food intake for the body’s immediate and long-term energy demands is carried through a multifaceted integration of endocrine and neural inputs. The brain employs long-term signals of metabolic status and short-term signals related to nutrient content of discrete meals to sustain energy homeostasis and satiety (Williams 2014). Furthermore, hedonic factors such as palatability, motivation, and learned associations distinctly impact feeding behavior. Adiposity signals, such as the hormones leptin and insulin, influence the homeostatic and hedonic aspects of feeing behaviors, in part by modulating the hindbrain response to satiation signals, through downstream projections from the hypothalamus or via direct action in the caudal brainstem (Williams 2014). Interestingly, promising evidence associates HDAC activity in modulating glucose and energy metabolism as the expression profile of HDACs is altered in the medial hypothalamus in response to fasting and high-fat diet-induced obesity (Funato, Oda et al. 2011). In mice, a 24-hour food-deprivation period increases HDAC3 and HDAC4 and decreases HDAC10 and HDAC11 mRNA expression in the medial hypothalamus, whereas a 4-week high-fat diet increases HDAC5 and −8 levels. Short term fasting also decreases acetylation of histones H3 and H4 in the ventromedial hypothalamus (Funato, Oda et al. 2011). Accordingly, hypothalamic leptin signaling is substantially impaired in HDAC5 knockout mice while HDAC5 overexpression in the mediobasal hypothalamus improves leptin sensitivity and ameliorates high-fat diet-induced leptin resistance and obesity (Kabra, Pfuhlmann et al. 2016). Therefore, selective HDAC5 deactivation/activation within hypothalamic nuclei could prove as a promising approach to counteract leptin resistance and obesity. Such a particular involvement of HDAC5 in adipocyte functions is further supported by the reduced HDAC5 and HDAC6 mRNA expression levels in adipocytes of obese human subjects and in mice fed on a high-fat diet for 16 weeks (Bricambert, Favre et al. 2016). Interestingly, hypoxia-induced CREB-dependent activation in adipocytes is a possible mechanism leading to obesity, as it has been shown to reduce inducible cAMP early repressor (ICER), a passive transcriptional repressor that prevents binding of CREB and thus leading to gene silencing of various genes encoding for adipokines involved in insulin resistance. Notably, HDAC5 and HDAC6 down-regulation in adipocytes by RNAi or selective HDAC inhibitors mimics the effects of hypoxia on the expression of ICER, and leads to a deficit in insulin-induced glucose uptake, which thereby highlights a critical role for HDAC5 and HDAC6 in adipocytes function (Bricambert, Favre et al. 2016). Furthermore, it is important to note that cognitive impairment associated with metabolic syndrome (i.e. abdominal obesity, elevated fasting plasma glucose, high serum triglycerides, and low high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol) levels could be a strong risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease. Mice maintained on a high-fat diet not only exhibited metabolic disorder-related symptoms (significantly raised levels of serum glucose, triglycerides, total cholesterol) but also showed severe deficits in learning and memory and impairments in passive avoidance tasks, along with increased oxidative stress and inflammatory markers (Sharma, Taliyan et al. 2015). Notably, TSA administration rescued the high-fat diet-induced metabolic, cognitive impairments, and BDNF protein deficits (Sharma, Taliyan et al. 2015) suggesting that the corrected performance in cognitive tasks and metabolic parameters in TSA-treated mice maintained on a high-fat diet might occur via enriched BDNF-based synaptic plasticity. Although the exact HDACs involved in this process still remain unknown, these findings indicate that in addition to its effects on physiological adipocyte functions, abnormal HDAC activity could play a role in the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative and metabolic syndromes, and that HDAC inhibition can offer interesting neuroprotective and neuro-regenerative properties.

3.3 Effects of HDACi on motivated social behaviors

3.3.1 Maternal Behavior

Healthy postnatal development is contingent upon the quality and quantity of maternal care. However, the integrity of maternal behavior can be compromised by psychiatric disorders, such a postpartum depression and drug addiction, which can significantly hinder infant growth (Numan and Young 2016). As a result, the neural mechanisms that underlie mother-infant bonds have been extensively studied and revealed the importance of the medial preoptic area (MPOA) in facilitating maternal behavior in response to hormonal and pup-elicited sensory stimulation. Interestingly, promising work by Stolzenberg et al (2012 and 2014) has begun to associate the degree of maternal responsiveness, in the absence of endocrine events related to pregnancy and parturition, with histone modifications. Indeed, nulliparous females retrieve foster pups faster and sustain higher levels of maternal responsiveness when compared to postpartum females (Stolzenberg and Rissman 2011). This rapid pup retrieval response is enhanced by oral NaB treatment when compared to nulliparous females treated with vehicle (Stolzenberg, Stevens et al. 2012). Importantly, while maternal experience-dependent changes in maternal care were associated with upregulated expression of estrogen receptor β (Esr2), oxytocin, and CBP mRNA in the MPOA, NaB treatment reduced the amount of maternal experience required to promote genetic expression of Esr2, oxytocin, and CREB binding protein (CBP), suggesting that HDAC inhibition potentiates maternal responsiveness (Stolzenberg, Stevens et al. 2012). For pup-naïve mice, the environment can affect the valence of pup stimuli, as NaB-facilitated pup retrieval occurred in the home cage and failed to induce pup retrieval in a novel environment. One possible explanation offered by the authors is that maternal responsiveness from nulliparous females is potentiated by NaB treatment where sensory cues from pup stimuli are neutral in a familiar environment and prove to be aversive in a novel environment. The enhanced maternal responsiveness endured 1 month after NaB treatment and was associated with a stable increased up-regulation of Esr2 mRNA levels and decreased down-regulation of oxytocin and Dnmt3a mRNA through recruitment of the histone acetyltransferase CBP to the Esr2 and oxytocin promoter and diminished expression of the de novo DNA methyltransferase (Stolzenberg, Stevens et al. 2014). Similar to maternal responsiveness, the degree of maternal licking and grooming (LG) in the offspring results from a complex epigenetic regulation of GR expression involving DNA methylation, histone acetylation, and transcription factor (NGFI-A) binding to its promoter (Weaver, Cervoni et al. 2004). These changes are maintained throughout adulthood and in turn shaped offspring to become low LG mothers with heightened stress responsivity in comparison with offspring from high LG mothers (Weaver, Cervoni et al. 2004). Additionally, central infusion of TSA or cross-fostering rescued the behavioral impairments and altered epigenetic states back to control levels (Weaver, Cervoni et al. 2004). Together these findings suggest a potential mechanism through which maternal behavior facilitates enduring changes in gene expression, and importantly reveal the promoting and potentiating effects of HDAC inhibition on maternal behavior.

3.3.2 Aggressive Behavior

A fundamental social behavior, aggression serves as a function of territorial defense, group structure, reproductive success, monogamy, competition for food, and parental investment (Clutton-Brock and Huchard 2013). The neural mechanisms that mediate aggressive behavior are hence likely to be conserved across the animal kingdom. Stressful environments or environments with a presence of violent encounters have been attributed to cause aggressive behaviors in humans and rodents alike (Takahashi, Quadros et al. 2012). At the molecular level, the serotonergic system in the amygdala and prefrontal cortex has been linked to impulsive aggression in adulthood with early exposure to stress and violence (Nelson and Trainor 2007). Additionally, genetic and hormonal factors interact with the environment to modulate the expression of sex-related aggressive behaviors. For instance, while aggression toward a male intruder is exhibited by socially-isolated male mice, but not female mice (Pinna, Agis-Balboa et al. 2004), treatment with L-methionine (MET), a methyl donor involved in DNA methylation, inhibits aggression in socially-isolated males with an associated down-regulation of reelin and glutamic acid decarboxylase67 (GAD67) mRNA levels in the prefrontal cortex (Pinna, Agis-Balboa et al. 2004). Interestingly, the selective down-regulation of reelin and GAD67 in prefrontal cortex is also observed in patients suffering from schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, who display higher rates of anger and aggression than the general population (Guidotti, Auta et al. 2000). In this paradigm, it is important to note that VPA treatment reversed the behavioral and epigenetic modifications induced by MET in socially-isolated mice (Tremolizzo, Doueiri et al. 2005), an effect that could be partially explained by increased local histone acetylation and a direct or indirect dissociation of DNMT and HDAC1-containing repressor complexes from the Gad67 and reelin promoters (Kundakovic, Chen et al. 2009). As reduced levels of reelin and GAD67 in cortical interneurons is an associated risk for schizophrenia (Guidotti, Auta et al. 2000), these observations suggest that targeting HDACs could prove valuable in treating aggression-seeking behaviors. Likewise, combination therapy of VPA with atypical antipsychotics results in faster improvements in patients hospitalized for acute exacerbation of schizophrenia (Casey, Daniel et al. 2003), suggesting that HDACi could promote therapeutic success through potentiation of currently available therapeutics.

3.3.3 Sexual Behavior

Disruption of histone acetylation during development influences how the brain and sexual behavior are organized in a sex-specific manner (Murray, Hien et al. 2009, Matsuda, Mori et al. 2011). Indeed, while the principal nucleus of the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNSTp) is generally larger in male mice due to higher cell death in the BNSTp in female mice, the masculinizing actions of testosterone in the BNSTp is eliminated by perinatal VPA treatment, as evidenced by a reduction of BNSTp volume and cell number in males and testosterone-treated females that are comparable to oil-treated females (Murray, Hien et al. 2009). Markedly, the effects of VPA were not present in the suprachiasmatic nucleus or the anterodorsal nucleus of the thalamus, two control brain regions not sexually dimorphic in mice, which indicates that these effects of VPA are specific and depend on an interaction with the hormonal status rather than denoting unspecific interactions with brain development. Moreover, HDAC2 and 4 binding at the estrogen receptor alpha (Esr1) and aromatase genes, which are known to facilitate masculinization of sexual behavior, is higher in the MPOA of male rats when compared to females (Matsuda, Mori et al. 2011). Accordingly, HDAC inhibition by TSA treatment or specific HDAC2 and 4 disruption by antisense oligodeoxynucleotides during early postnatal development resulted in impaired adult male sexual behavior (Matsuda, Mori et al. 2011), indicating that HDAC activity, carried out in particular by HDAC2 and 4, is critical for masculinization of the brain. It is important to note, however, that despite representing a powerful illustration of the widespread involvement of HDACs and their importance in the functions of the central nervous system, these data also reveal the potential consequences of HDACi exposure during developmental periods.

In adult female rodents, ovarian hormones—estrogens in particular—regulate gene transcription through the activation of genomic and non-genomics events (Vasudevan and Pfaff 2008), which in turn directly control sexual behaviors such as sexual receptivity. For a female rodent to show sexual receptivity, she must arch her back and move her tail to the side to allow a male to achieve penile intromission (i.e. lordosis), a behavior that is estrogen-dependent and under the control of the ventromedial hypothalamus (VMH) (Walf, Ciriza et al. 2008, Cameron 2011). Interestingly, estrogen control of gene expression is associated with epigenetic mechanisms in several brain areas (Sharma et al., 2012, Fortress et al., 2014), including the VMH where estradiol-β treatment increases histone methylation (H3K9) and acetylation of histone H4 proteins (Weil, Murakami et al. 2010). Furthermore, histone acetylation is linked to lordosis behavior as VMH-microinjections of NaB promote estrogen-induced lordosis in virgin females and reduces male-directed rejection behaviors (Weil, Murakami et al. 2010, Bonthuis, Patteson et al. 2011). However, NaB treatment has no effect on female sexual receptivity in the absence of a functional estrogen receptor alpha (ERα), necessary to induce female sexual receptivity, as NaB cannot promote lordosis independently of estrogen and progesterone and cannot sustain receptivity in sexually-experienced females in the absence of estrogen and progesterone replacement in ERα knockout female mice (Bonthuis, Patteson et al. 2011). Hence it is necessary for future studies to interrogate how these molecular mechanisms incorporate endocrine-facilitated acquisition of sexual behaviors. Moreover, these findings support the notion that HDACi are dependent on the context/environment, which thus indicates that they potentiate the impact of the environment rather than triggering an independent response.

3.3.4 Pair Bonding

The unique social system of the monogamous prairie vole (Microtus ochrogaster) makes it an excellent model for investigating the neurobiological mechanisms underlying social bonding in humans. This animal model moreover highlights the importance of normal brain development as conveyed by the impact of environmental factors and their epigenetic contributions on social development as deficits of social interactions is a common feature of psychiatric disorders. In prairie voles, at least 24 hours of cohabitation with mating facilitates an enduring partner preference (Williams, Catania et al. 1992, Insel, Preston et al. 1995). This monogamous behavior, only observed in 3% of mammalian species, is modulated by numerous neuropeptides and neurotransmitters including but not limited to oxytocin, vasopressin, and dopamine (Young, Gobrogge et al. 2011). Recent studies have provided exciting evidence for an epigenetic basis that mediates the regulation of these important neurotransmitters. In virgin females that cohabitated for only 6 hours without mating, TSA infusion within the NAcc reliably facilitates the formation of partner preference and enhances histone H3 acetylation at the oxytocin receptor (OXTR) and vasopressin 1a receptor (V1aR) genes promoters, accompanied by enhanced OXTR and V1aR mRNA and protein expression (Wang, Duclot et al. 2013). While these changes are recapitulated by 24h cohabitation with mating, TSA effects are dependent on the exposure to social cohabitation, which indicates that HDAC inhibition only potentiates the impact of social interaction during the cohabitation period, ultimately leading to pair bonding (Wang, Duclot et al. 2013). Remarkably, cohabitation with mating or central TSA treatment in male prairie voles only upregulates OXTR, but not V1aR, mRNA and protein expression in the NAcc (Duclot, Wang et al. 2016), indicating that the molecular correlates for the initiation of a social pair bond in the prairie vole NAcc are sexually dimorphic. It would nonetheless be interesting to examine the effects of central TSA in the other brain regions associated with pair bonding, such as the lateral septum (LS) and ventral pallidum (VP) as the facilitative effects of V1aR expression might be present in these latter regions within males since V1aR antagonism within the LS and VP prevents male-specific partner preference formation (Liu, Curtis et al. 2001, Lim and Young 2004). These findings thus reveal the critical role of epigenetic mechanisms in the regulation of oxytocin neurotransmission in the nucleus accumbens underlying formation of partner preference, and highlight the promising value of HDACi as candidates for altering the ability to form social attachment.

4. Conclusion and Implications

In this review, we summarized and discussed the current literature on the role of HDACi in modulating motivated behaviors. Along with the increasing association of epigenetic mechanisms, including histone acetylation, with high order brain functions such as motivated behaviors, the possibility to dynamically alter neuroplasticity-related gene expression through readily available pharmacological tools such as HDACi has gained substantial interest over the years. As a result, HDACi have now been reported to modulate a variety of complex processes such as addictive or social behaviors. Notably, HDAC inhibition has showed promising effects in reducing seeking of several classes of drugs of abuse, including cocaine, opiates, or alcohol. Moreover, HDACi can also positively affect feeding behaviors, and complex social behaviors such as maternal responsiveness, social attachment, as well as aggressive or sexual behaviors. Inherent from the relatively limited availability of isoform-selective HDACi, their use in a therapeutic context could seem difficult at first due to a high risk for adverse side-effects. Nevertheless, the currently available preclinical data support a rather specific action of HDACi and limited side-effects which could be explained by one of their key features of action. Indeed, while the molecular effects of HDACi observed can be widespread and affect a variety of neuroadaptations, they depend on activation of the given targets by stimuli such as neuronal activity or hormones, indicating that they facilitate and potentiate the impact of environmental signals on gene expression rather than triggering neuroadaptations on their own. Co-administration of TSA and heroin enhances heroin-induced CPP, while TSA treatment on heroin-naïve subjects cannot facilitate locomotor activity or place preference (Sheng, Lv et al. 2011). Moreover, it is important to consider the tissue and neuronal subpopulation specificity in HDACs expression which, in combination with the activation-dependent nature of HDACi’s effects, provides another layer of specificity even to inhibitors with poor isoform-selectivity. Although developing such isoform-selective HDACi remains of critical importance, these observations do support the use of HDACi for intervening on motivated behaviors. It is important to note, however, that the potentiating effect commonly observed following HDACi treatment, although representing a unique advantage, warrants careful timing of administration as it also underlines the risk for facilitating undesirable negative experiences. This is particularly well illustrated, for instance, by the potential of HDACi to enhancing the reinforcing properties of drugs of abuse, as seen with cocaine and opiates. Accordingly, the range of processes modulated by HDACi expands beyond the motivated behaviors described in this review to other complex behaviors, such as emotional response and stress-related mood disorders, or learning and memory and cognitive performances (Sandner, Host et al. 2011, Graff and Tsai 2013, Fass, Schroeder et al. 2014, Schmauss 2015). In this context, it is therefore not surprising to observe interest in clinical trials investigating HDACi effects in the central nervous system beyond the cancer field, such as psychiatric disorders (Covington, Vialou et al. 2011, Hasan, Mitchell et al. 2013, Covington, Maze et al. 2015, Qiu, Xiao et al. 2017). Interestingly, recent exciting work combines positron emission tomography with Martinostat, an imaging probe selective for HDACs 1, 2, and 3 (class I), to evaluate HDACs expression and distribution between healthy and disease-afflicted individuals in vivo (Wey et al., 2016). This novel neuroimaging technique, in combination with the preclinical work, will help better understand the link between HDACs and brain functions, as well as help refine HDACi-based interventions to ultimately highlight HDAC inhibition in the central nervous system as a promising avenue for treatment for brain disorders and abnormalities in social behaviors.

Highlights.

Environmental stimuli influence motivated behaviors through histone acetylation.

The effects of histone deacetylase inhibitors are time- and context-dependent.

Histone deacetylase inhibitors potentiate the impact of the environment.

Histone deactylase inhibitors alter drug addiction, feeding, and social behaviors.

Acknowledgments

We thank Charles Badland for his assistance with the figures. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01-MH058616 to ZXW and R01-MH087583, R01-MH099085, and R01-MH109450 to MK.

Appendix

- Introduction

-

1.1A brief introduction to epigenetic modifications

-

1.1.1Nucleosome positioning

-

2.1.1Histone modifications

-

3.1.1DNA methylation

-

4.1.1Noncoding RNA

-

1.1.1

-

1.1

- Histone acetylation

-

2.1Classification and localization of HDACs

-

2.2Overview and classification of histone deacetylase inhibitors

-

2.1

- Motivated behaviors

-

3.1Effects of HDACi on drug-seeking behavior

-

3.1.1Cocaine

-

3.1.2Opioids

-

3.1.3Alcohol

-

3.1.1

-

3.2Effects of HDACi on feeding behaviors

-

3.3Effects of HDACi on motivated social behaviors

-

3.3.1Maternal behavior

-

3.3.2Aggressive behavior

-

3.3.3Sexual behavior

-

3.3.4Pair bonding

-

3.3.1

-

3.1

Conclusions and Implications

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest

The authors report no conflict of interest as it related to the content of this work.

References

- Abernathy K, Chandler LJ, Woodward JJ. Alcohol and the prefrontal cortex. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2010;91:289–320. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7742(10)91009-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adinoff B. Neurobiologic processes in drug reward and addiction. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2004;12(6):305–320. doi: 10.1080/10673220490910844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alaux-Cantin S, Warnault V, Legastelois R, Botia B, Pierrefiche O, Vilpoux C, Naassila M. Alcohol intoxications during adolescence increase motivation for alcohol in adult rats and induce neuroadaptations in the nucleus accumbens. Neuropharmacology. 2013;67:521–531. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allis CD, Caparros ML, Jenuwein T, Reinberg D. Epigenetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Cold Spring Harbor: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Avlar B, Kahn JB, Jensen G, Kandel ER, Simpson EH, Balsam PD. Improving temporal cognition by enhancing motivation. Behav Neurosci. 2015;129(5):576–588. doi: 10.1037/bne0000083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjerling P, Silverstein RA, Thon G, Caudy A, Grewal S, Ekwall K. Functional divergence between histone deacetylases in fission yeast by distinct cellular localization and in vivo specificity. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22(7):2170–2181. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.7.2170-2181.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolden JE, Peart MJ, Johnstone RW. Anticancer activities of histone deacetylase inhibitors. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5(9):769–784. doi: 10.1038/nrd2133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonthuis PJ, Patteson JK, Rissman EF. Acquisition of sexual receptivity: roles of chromatin acetylation, estrogen receptor-alpha, and ovarian hormones. Endocrinology. 2011;152(8):3172–3181. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bricambert J, Favre D, Brajkovic S, Bonnefond A, Boutry R, Salvi R, Plaisance V, Chikri M, Chinetti-Gbaguidi G, Staels B, Giusti V, Caiazzo R, Pattou F, Waeber G, Froguel P, Abderrahmani A. Impaired histone deacetylases 5 and 6 expression mimics the effects of obesity and hypoxia on adipocyte function. Mol Metab. 2016;5(12):1200–1207. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2016.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calipari ES, Bagot RC, Purushothaman I, Davidson TJ, Yorgason JT, Pena CJ, Walker DM, Pirpinias ST, Guise KG, Ramakrishnan C, Deisseroth K, Nestler EJ. In vivo imaging identifies temporal signature of D1 and D2 medium spiny neurons in cocaine reward. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(10):2726–2731. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1521238113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calipari ES, Juarez B, Morel C, Walker DM, Cahill ME, Ribeiro E, Roman-Ortiz C, Ramakrishnan C, Deisseroth K, Han MH, Nestler EJ. Dopaminergic dynamics underlying sex-specific cocaine reward. Nat Commun. 2017;8:13877. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron NM. Maternal programming of reproductive function and behavior in the female rat. Front Evol Neurosci. 2011;3:10. doi: 10.3389/fnevo.2011.00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey DE, Daniel DG, Wassef AA, Tracy KA, Wozniak P, Sommerville KW. Effect of divalproex combined with olanzapine or risperidone in patients with an acute exacerbation of schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28(1):182–192. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen WS, Xu WJ, Zhu HQ, Gao L, Lai MJ, Zhang FQ, Zhou WH, Liu HF. Effects of histone deacetylase inhibitor sodium butyrate on heroin seeking behavior in the nucleus accumbens in rats. Brain Res. 2016;1652:151–157. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2016.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhary C, Kumar C, Gnad F, Nielsen ML, Rehman M, Walther TC, Olsen JV, Mann M. Lysine acetylation targets protein complexes and co-regulates major cellular functions. Science. 2009;325(5942):834–840. doi: 10.1126/science.1175371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clutton-Brock TH, Huchard E. Social competition and selection in males and females. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2013;368(1631):20130074. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2013.0074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins PY, Patel V, Joestl SS, March D, Insel TR, Daar AS, B. Scientific Advisory, H. the Executive Committee of the Grand Challenges on Global Mental. Anderson W, Dhansay MA, Phillips A, Shurin S, Walport M, Ewart W, Savill SJ, Bordin IA, Costello EJ, Durkin M, Fairburn C, Glass RI, Hall W, Huang Y, Hyman SE, Jamison K, Kaaya S, Kapur S, Kleinman A, Ogunniyi A, Otero-Ojeda A, Poo MM, Ravindranath V, Sahakian BJ, Saxena S, Singer PA, Stein DJ. Grand challenges in global mental health. Nature. 2011;475(7354):27–30. doi: 10.1038/475027a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contet C. Gene Expression Under the Influence: Transcriptional Profiling of Ethanol in the Brain. Curr Psychopharmacol. 2012;1(4):301–314. doi: 10.2174/2211556011201040301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covington HE, 3rd, Maze I, Vialou V, Nestler EJ. Antidepressant action of HDAC inhibition in the prefrontal cortex. Neuroscience. 2015;298:329–335. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.04.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covington HE, 3rd, Vialou VF, LaPlant Q, Ohnishi YN, Nestler EJ. Hippocampal-dependent antidepressant-like activity of histone deacetylase inhibition. Neurosci Lett. 2011;493(3):122–126. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day J, Savani S, Krempley BD, Nguyen M, Kitlinska JB. Influence of paternal preconception exposures on their offspring: through epigenetics to phenotype. Am J Stem Cells. 2016;5(1):11–18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson ZR, Young LJ. Oxytocin, vasopressin, and the neurogenetics of sociality. Science. 2008;322(5903):900–904. doi: 10.1126/science.1158668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duclot F, Wang H, Youssef C, Liu Y, Wang Z, Kabbaj M. Trichostatin A (TSA) facilitates formation of partner preference in male prairie voles (Microtus ochrogaster) Horm Behav. 2016;81:68–73. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2016.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espallergues J, Teegarden SL, Veerakumar A, Boulden J, Challis C, Jochems J, Chan M, Petersen T, Deneris E, Matthias P, Hahn CG, Lucki I, Beck SG, Berton O. HDAC6 regulates glucocorticoid receptor signaling in serotonin pathways with critical impact on stress resilience. J Neurosci. 2012;32(13):4400–4416. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5634-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fass DM, Schroeder FA, Perlis RH, Haggarty SJ. Epigenetic mechanisms in mood disorders: targeting neuroplasticity. Neuroscience. 2014;264:112–130. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.01.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fervaha G, Zakzanis KK, Foussias G, Graff-Guerrero A, Agid O, Remington G. Motivational deficits and cognitive test performance in schizophrenia. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(9):1058–1065. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields HL, Margolis EB. Understanding opioid reward. Trends Neurosci. 2015;38(4):217–225. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2015.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finazzi G, Vannucchi AM, Martinelli V, Ruggeri M, Nobile F, Specchia G, Pogliani EM, Olimpieri OM, Fioritoni G, Musolino C, Cilloni D, Sivera P, Barosi G, Finazzi MC, Di Tollo S, Demuth T, Barbui T, Rambaldi A. A phase II study of Givinostat in combination with hydroxycarbamide in patients with polycythaemia vera unresponsive to hydroxycarbamide monotherapy. Br J Haematol. 2013;161(5):688–694. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]