Abstract

Purpose

To describe an efficient numerical optimization technique using non-linear least squares to estimate perfusion parameters for the Tofts and extended Tofts models from dynamic contrast enhanced (DCE) MRI data and apply the technique to prostate cancer.

Methods

Parameters were estimated by fitting the two Tofts-based perfusion models to the acquired data via non-linear least squares. We apply Variable Projection (VP) to convert the fitting problem from a multi-dimensional to a one-dimensional line search to improve computational efficiency and robustness. Using simulation and DCE-MRI studies in twenty patients with suspected prostate cancer, the VP-based solver was compared against the traditional Levenberg-Marquardt (LM) strategy for accuracy, noise amplification, robustness to converge, and computation time.

Results

The simulation demonstrated that VP and LM were both accurate in that the medians closely matched assumed values across typical signal to noise ratio (SNR) levels for both Tofts models. VP and LM showed similar noise sensitivity. Studies using the patient data showed that the VP method reliably converged and matched results from LM with approximate 3× and 2× reductions in computation time for the standard (two-parameter) and extended (three-parameter) Tofts models. While LM failed to converge in 14% of the patient data, VP converged in the ideal 100%.

Conclusion

The VP-based method for non-linear least squares estimation of perfusion parameters for prostate MRI is equivalent in accuracy and robustness to noise, while being more reliably (100%) convergent and computationally about 3× (TM) and 2× (ETM) faster than the LM-based method.

Keywords: Prostate Cancer, Dynamic-Contrast-Enhanced Magnetic Resonance Imaging, Pharmacokinetic Modeling, Perfusion, Multi-Parametric Magnetic Resonance Imaging

1. INTRODUCTION

Perfusion imaging via dynamic contrast-enhanced (DCE) MRI uses pathological angiogenesis as a biomarker for differentiation of cancerous vs. normal tissue [1]. In tumors, due to abnormal angiogenesis, there is a corresponding increase in the amount of blood delivered to the capillary bed and perfusing the tissue, and this can be detectable with MRI. A number of perfusion models applicable to DCE-MRI have been proposed [2–4]. Among these models, the Tofts model (TM) [5] and extended Tofts model (ETM) [6] are often used in perfusion analysis [7–23]. In the two-parameter TM, the perfusion parameters Ktrans, the volume transfer constant between blood plasma and extra-vascular extra-cellular space (EES), and kep, the rate constant, are estimated from the DCE-MRI data. Ktrans and kep are related by kep = Ktrans/ve, where ve represents the fractional volume of the EES. With the ETM, a third parameter, the vascular fractional volume, vp, is also allowed. It is known that parameters Ktrans and kep both tend to increase in malignant vs. benign tissue [24–28]. Thus, it is desirable to obtain accurate estimates of these parameters.

The contrast concentration vs. time curves from DCE-MRI are used to estimate the pharmacokinetic parameters by fitting a perfusion model to the acquired data. This is done traditionally by using an implementation of non-linear or linear least-squares estimation [29]. Non-linear least squares (NLLS) such as the Levenberg-Marquardt (LM) algorithm [30,31] allow mathematical flexibility in the perfusion model but often require an iterative search and selecting the initial search point. NLLS methods have been used in DCE-MRI [32–34]. Use of multiple search starting points can provide higher accuracy in the results but with increased computation time [33]. Linear least squares (LLSQ) optimizations have also been used in DCE-MRI [32,34,35]. However, the linearization of a non-linear problem can result in differences in data weighting and possible bias [34,36]

The goal of this work is to use the variable projection (VP) approach [37] to develop a robust and efficient numerical optimization strategy which addresses current limitations of both NLLS and LLSQ methods in DCE-MRI. The VP-based NLLS framework arises naturally from the TM and ETM perfusion models with no additional assumptions or simplifications. At the same time, the VP-based approach is shown to have superior characteristics such as speed, simplicity of implementation, and overall robustness vs. a widely-used NLLS implementation, LM.

The fitting algorithm presented here is based on the general approach of variable projection (VARPRO or “VP”), described in the mathematical literature several decades ago [37]. This approach reduces the dimensionality of the problem of estimation of multiple parameters from a data set according to some mathematical model and has been used in multiple applications. Examples in MR include determining the localized polynomial approximation parameters for model-based reconstruction [38], MR spectroscopy [39–41], T1 mapping in single [42] and multichannel [43] acquisition, T1ρ mapping as a biomarker for liver cirrhosis [44], fat-water estimation [45–50], and MR fingerprinting [51]. Variable projection has been also used in kinetic parameter estimation of DCE-MRI to account for an unknown arterial input function (AIF) via multichannel blind identification [52,53]. However, to our knowledge VARPRO has not been applied to the TM and ETM where the perfusion parameters are estimated with this technique.

The VP-based method for estimating the perfusion parameters is presented here in the context of prostate cancer, the most common non-cutaneous cancer among men in the United States [54]. If found in its early stages, a number of treatment options can lead to high survival rates. Due to the limited specificity of monitoring the prostate specific antigen (PSA) level the use of MRI for diagnosis or staging of prostate cancer has increased in recent years. Prostate MRI is typically performed using a multi-parametric MRI (mpMRI) exam [55–57] which includes T2-weighted spin-echo (T2SE), diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI), and T1-weighted DCE-MRI sequences. Quantitative perfusion based on the DCE-MRI has been widely studied in the prostate [9,18–20,24,27,58–61], and DCE-MRI plays a role in risk stratification for patients with suspected prostate cancer in the PI-RADS v2 reporting system [57]. DCE-MRI is especially important in the evaluation of local recurrence after radiotherapy or radical prostatectomy [62,63].

In the following sections we derive formulas for DCE-MRI perfusion parameter estimation for the TM and ETM using the VARPRO approach, compare performance with traditional Levenberg-Marquardt methods, and demonstrate its applicability in a group of 20 patients with known prostate cancer as validated by histology. This work is an expansion of material presented previously in abstract form [64,65].

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Parameter Estimation Using VARPRO for the Tofts Model

Perfusion is modeled as a two compartment system in which a low-molecular weight gadolinium contrast agent can diffuse out of the blood vessels into the EES but not enter the cells. Therefore, the two compartments of the tracer distribution are the blood plasma and the EES. In the derivations which follow, lower and upper case bold denote vector and matrix, respectively, [·]* denotes the conjugate transpose of [·], and [·]t denotes that the first dimension of [·] has length N, with each entry corresponding to a different time t for N total time frames. Using the original Tofts model (TM) [5] the modeled tissue contrast concentration p(t) is given by Eq. (1) for each voxel:

| (1) |

where Ktrans and kep are the transfer constant and rate constant respectively, each measured in min−1, and a(τ) is the measured or assumed AIF. This integral form of the TM can subsequently be discretized to yield:

| (2) |

where ⊗ is the convolution operator and at and pt are the vector versions of a(t) and p(t). Also note that ht(kep) is defined as e−kept. Eq. (2) can be re-expressed in linear algebraic form using the N × N matrix A comprised of elements of at:

| (3) |

where A is given by:

| (4) |

and zero-padded boundary conditions are assumed to include only the first N points to match the acquired perfusion data, ct.

The goal of pharmacokinetic parameter estimation is to fit the model pt to the measurements ct for each voxel of interest. That is to say, Ktrans and kep are selected to best fit the model, pt, to the measured data, ct.

The discrete parametric model in Eq. (2) can be fit on a pixel-wise basis to the time-course data associated with DCE-MR image series via NLLS regression, wherein the difference between the model as realized with a specific parameter set and the data is minimized. This fitting can be done by first defining the NLLS cost function J(Ktrans, kep):

| (5) |

and minimizing it through some iterative numerical process to find the optimum values of the model parameters, K̂trans and k̂ep. For the TM the cost function depends on both Ktrans and kep, and thus a two-dimensional (2D) optimization problem must be solved for each voxel. As J(Ktrans, kep) is quadratic with respect to Ktrans, one can derive a closed-form analytical expression for its NLLS-optimal value which will be a (non-linear) function of the other parameter, kep, and the data vector, ct. As shown in Appendix A, the closed-form expression for K̂trans is:

| (6) |

where:

| (7) |

Using the VARPRO method, the parametric expression for K̂trans can then be inserted back into Eq. (5) which causes the dimensionality of J to be reduced from 2D to 1D. Doing so, as developed further in Appendix A, leads to the following simplified cost function expression:

| (8) |

To find k̂ep from Eq. (8), one can evaluate the cost function for a range of kep values and find the minimum of J(K̂trans(kep), kep) via line search. The found k̂ep is then used to directly determine K̂trans via Eq. (6), completing the optimization. The simplification in the search for optimum values K̂trans and k̂ep provided by VARPRO is illustrated in Supplemental Figure S1.

2.2 Parameter Estimation Using VARPRO for the Extended Tofts Model (ETM)

Compared to the standard Tofts Model, the extended Tofts Model (ETM) has an additional term, the vascular fraction, vp, as shown below:

| (9) |

The VARPRO technique can be applied to the ETM similarly to the TM. Again, the integral form can be expressed in algebraic form but now with the linear terms Ktrans and vp combined into a vector x:

| (10) |

where the dimension N × 2 matrix Bt(kep) is defined by:

| (11) |

Eq. (10) for ETM is similar to Eq. (3) for TM in that the linear term is projected onto the other non-linear term to reduce the dimensionality of the problem to only one dimension. The only difference in ETM is the above-described vector vs. a scalar. The remainder of the optimization of ETM is essentially the same as for the TM, shown in Appendix B, and leading to the results:

| (12) |

| (13) |

2.3 Implementation

For efficient optimization, we used the Golden Section Search (GSS) technique [66], in which the minimum is found by sequentially narrowing the search range until reaching a prescribed tolerance. The GSS technique substantially reduces the number of iterations to find the minimum. An advantage of GSS is that given the viable range of search for the optimum parameter, the number of iterations is predictable based on the desired estimation resolution or tolerance [66]. Also, the one-dimensionality of the problem eliminates any uncertainty about the initialization of the optimization process. The search range need only encompass possible values of kep. For this work, the search range for kep = [0.03 – 6] min−1 with tolerance of 0.0005 requires twelve iterations for VARPRO-based method. To match both methods, the LM iteration was stopped at twelve iterations as well and found to be adequate. We have used the magnitude of the MRI data for our patient studies and not the complex data.

The additional term in the ETM, vp, must physiologically be a value between 0 and 1, and it is expected to be small, the order of 0.01. No constraints were placed on its estimation, and for LM vp was initialized as 0.01.

2.4 Patient Studies

The VP-based perfusion analysis described above was evaluated in numerical simulations as well as in human studies performed under a protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board. All enrolled subjects gave formal informed consent. All patients who met the following criteria were enrolled: (i) underwent the standard protocol for prostate MRI exam at 3 Tesla (Discovery MR750w, GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI), (ii) exam interpretation by one of the coauthors (ATF, five years experience in prostate MRI), (iii) subsequent histological evaluation of a prostate specimen after transrectal ultrasound-guided biopsy in either the 2nd or 4th quarter of 2016. This was a total of 20 subjects, 16 of which had subsequent radical prostatectomy. Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Prostate adenocarcinoma was documented in 19 of the 20 patients after biopsy.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients used for evaluation of VARPRO-based estimation technique.

| Case # | Age (year) | Weight (kg) | DCE-MRI frame time (s) | PSA at the time of mpMRI a (ng/mL) | Gleason Score | Tumor description (number, location, size) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biopsy | RP b | ||||||

| 1 | 66 | 110 | 6.374 | 8.7 | 4+3 | 3+4 | Single lesion/Right superior-mid posterior/1.5 × 1.1 × 0.5 cm |

| 2 | 64 | 73 | 6.597 | 11.0 | 4+3 | 4+3 | Dominant lesion/Posterior right peripheral zone/1.0 × 0.8 × 0.4 cm |

| 3 | 59 | 75 | 6.768 | 3.0 | 3+3 | 3+3 | Single lesion/Right posterior/base/Extruded BPH nodule at the prostate base/0.4 cm |

| 4 | 57 | 87 | 6.781 | 9.5 | 3+4 | 3+4 | Multifocal/Left superior posterior/Left dominant peripheral zone/0.9 × 0.5 × 0.4 cm |

| 5 | 69 | 82 | 6.087 | 20.5 | 4+4 | 3+4 | Multifocal/Left peripheral zone/dominant nodule, in left anterior inferior to left posterior superior/0.6 × 0.4 × 0.4 cm |

| 6 | 62 | 88 | 6.659 | 5.9 | benign | NP c | No evidence of malignancy at biopsy. |

| 7 | 75 | 92 | 7.073 | 6.0 | 3+3 | NP c | Midline posterior peripheral zone/needle biopsy |

| 8 | 64 | 70 | 5.836 | 5.3 | 3+3 | NP c | Left apex/needle biopsy |

| 9 | 71 | 85 | 6.630 | 4.8 | 3+3 | NP c | Bilateral/dominant right peripheral zone/needle biopsy |

| 10 | 68 | 86 | 5.295 | 6.5 | 3+3 | 3+4 | Multifocal/Dominant lesion right anterior prostate/2.3 × 1.8 × 1.1 cm/Multiple tumor foci left posterior prostate |

| 11 | 64 | 82 | 6.592 | 7.7 | 4+3 | 4+3 | Single lesion/left anterior mid prostate/1.0 × 0.5 × 0.4 cm |

| 12 | 60 | 75 | 6.380 | 7.8 | 4+3 (R) | 4+3 | Two lesions/right mid inferior posterior prostate/1.3 × 1.1 × 0.8 cm/left superior mid posterior prostate/1.4 × 1.2 × 0.5 cm |

| 13 | 67 | 111 | 6.369 | 4.7 | 3+4 | 3+4 | Single tumor/right posterior/2.4 × 1.2 × 1.0 cm |

| 14 | 71 | 84 | 6.329 | 6.5 | 4+3 (L) | 3+4 | Two lesions/left superior mid anterior posterior prostate/1.2 × 0.8 × 0.6 cm/right superior mid inferior anterior posterior prostate/1.1 × 1.1 × 0.9 cm |

| 15 | 64 | 153 | 5.640 | 8 | 3+4 | 3+4 | Multifocal/posterior aspect of right and left prostatic lobes |

| 16 | 59 | 82 | 6.340 | 21.4 | 4+4 | benign | Prostatectomy revealed benign prostatic tissue with scattered foamy histiocytic aggregates, consistent with positive response to neoadjuvant androgen deprivation therapy (ADT). Note mpMRI of the prostate was performed prior to ADT. |

| 17 | 67 | 84 | 6.448 | 13.4 | 3+4(L)/3+3(R) | 4+3 | Two lesions/left and right lobes/1.8 and 0.7 cm |

| 18 | 70 | 71 | 6.231 | 4.8 | 3+3 | 3+4 | Single lesion/left posterior/1.2 × 0.8 × 0.8 cm |

| 19 | 56 | 98 | 6.099 | 5.3 | 4+4 | 3+4 | Single lesion/involves right and left prostate/2.6 × 1.6 × 1.0 cm |

| 20 | 60 | 111 | 6.395 | 19.9 | 3+4 | 3+4 | Single lesion/left prostate/1.5 × 1.5 × 1.4 cm |

mpMRI = multi-parametric MRI

RP = radical prostatectomy

NP = not performed

In all cases, an mpMRI exam was done, which included T2SE, DWI with DWI-derived apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) map, and DCE-MRI sequences utilizing our institutional protocol. Relevant to this work are the acquisition parameters for the DCE-MRI sequence [67], summarized in Table 2, based on a 3D fast spoiled gradient-echo (SPGR) acquisition [68] with view sharing [69]. Gadolinium based MR contrast agent (Dotarem, gadoterate meglumine, Guerbet, Roissy CdG, France) at a dose of 0.1 mmol/kg was administered intravenously at 3 ml/s followed by a 20 ml saline flush at 3 ml/s using a mechanical power injector. Signal reception was done using 32 coil elements, 16 in an anterior array and 16 in a posterior array.

Table 2.

Typical imaging parameters for DCE-MRI

| TR (Repetition Time) | 5.3 ms a | |

| TE (Echo Time) | 2.2 ms a | |

| Sampling Resolution b (in-plane matrix) × slice | 256×384×38 | |

| Field of View b | 220×442×114 mm3 | |

| Spatial Resolution b | 0.86×1.15×3.0 mm3 | |

| Acceleration | RY | 2.49 |

| RZ | 1.12 | |

| Bandwidth | ±62.5 kHz | |

| Flip Angle | 12° | |

| Scan Time | ~ 4 min a | |

| Frame Time | 6.6 s a | |

| Temporal footprint | 19 s a | |

May change slightly depending on body habitus

Expressed as anterior/posterior (A/P) × left/right (L/R) × superior/inferior (S/I), corresponding to frequency × phase × slice encode directions

For each case there were one or more foci of suspected prostate cancer depicted on mpMRI, and the index lesion was noted in the radiological report. The representative axial section containing this index lesion was selected for subsequent analysis. For all 31 time frames of the DCE-MRI acquisition, the MRI signals in the target section were converted to concentration of contrast material by using the SPGR signal model [70]. Specifically, using the SPGR and fast exchange model equations, as well as the imaging parameters, the MRI signal was mapped to concentration, assuming known T10 for blood and tissue (1600 ms, and 1597 ms), the contrast agent relaxivity, r1 (4.0 mM−1s−1), and arterial maximum concentration (6 mM). The relative ratio between the arterial and tissue MRI signal was preserved. The resultant converted signals were then used for subsequent analysis. Ideally, the T1 relaxation times of the tissue and blood are estimated by T1-mapping [43]. However, in this work the relaxivity, r1, and pre-contrast, T10 value were assumed known from the literature [71]. The blood concentration curve vs. time was normalized for each individual by matching the area under the curve (first-pass) to the total concentration based on the weight of each patient. The blood volume was estimated as 5 L for a 70 kg man and extrapolated for lower or higher weights.

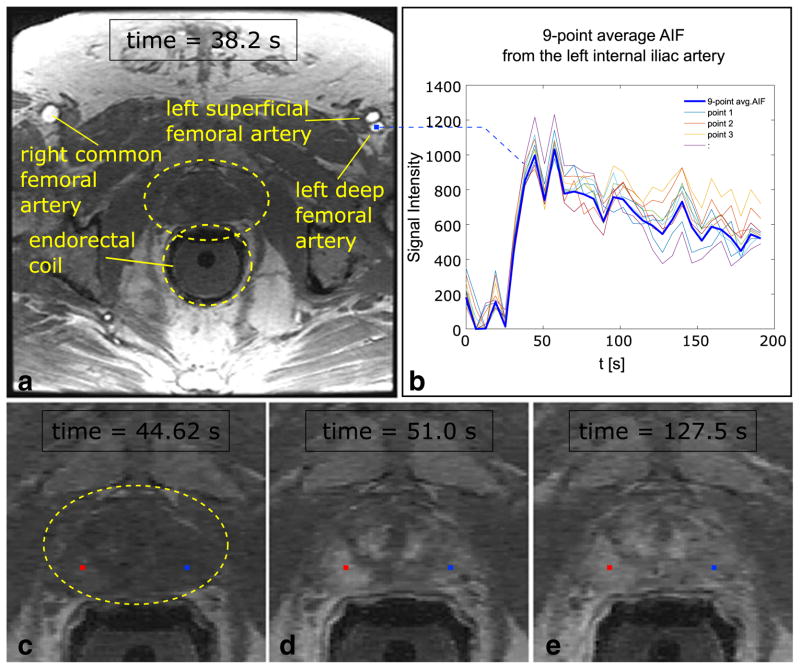

For each case the AIF, at in the derivation, was selected from a 3×3 voxel ROI chosen from within the lumen of the subject’s left or right external iliac or proximal femoral artery in the same axial section as the dominant lesion. This is illustrated for one of the twenty patient studies in Figure 1. Prior to this work we found that an ROI of this size provided good signal averaging across multiple pixels without contamination by edge effects at the lumen edge.

Figure 1.

(a) Axial slice of the pelvis (Patient #1) through the prostate showing the bilateral femoral arteries, prostate (within yellow oval) and endo-rectal coil (yellow circle, not active for DCE-MRI sequence). The arteries are enhanced at time 38.2 s post-injection. (b) Graph of the average (bold curve) arterial input function selected from the left deep femoral artery as shown. The average is from nine (3×3) individual voxels (non-bold curves). (c–e) Source DCE-MRI images demonstrate an area of hyperenhancement of cancerous tissue in the right peripheral zone at the apex compared to the non-cancerous tissue in the contralateral side at times 44.6 s (c), 51.0 s (d), and 127.5 s (e). Red and blue points show the representative voxels in the cancer and non-cancerous regions respectively. These are used in Figure 2.

2.5 Comparison with Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm

The proposed VP-based parameter estimation, which entails solving a one-dimensional optimization problem, was compared with conventional multi-dimensional non-linear estimation based on the Levenberg-Marquardt (LM) method. Comparisons of accuracy and precision were performed as well as comparisons of the speed of convergence, i.e., the number of iterations and elapsed time from the onset of fitting until a stable cost function minimum value was achieved. All computations were performed using MATLAB (R2016a, The Mathworks, Natick, MA) on a Linux (CentOS 6.8)-based workstation with two E5-2670v2 CPUs (each with 10 cores at 2.5GHz) and 64GB of RAM.

2.5.1. Accuracy and Precision

To validate the accuracy and precision of VP-based perfusion estimation, a numeric simulation was developed as described schematically in the flowchart in supporting Figure S2. Thirty-one time frames with 6.6 s sampling were assumed, matching the clinical DCE-MRI protocol of Table 2. Tissue perfusion was simulated according to the TM with various assumed values of Ktrans (0.1, 0.2, 0.3, and 0.4 min−1) and ve (0.1, 0.2, and 0.3) that created a total of twelve combinations of (Ktrans, kep = Ktrans/ve) that span those reported for normal and malignant tissue. Additionally for the ETM a vp value of 0.01 was assumed. A population-based AIF was used [72].

Simulated MRI signals were then generated from these assumed tissue and arterial contrast concentration curves with the SPGR signal model. To approximate the statistical properties of the magnitude MR images that are typically obtained clinically, zero-mean Gaussian noise was added to the simulated signals (AIF and tissue) which were then converted back into concentration curves for perfusion analysis using both the VP and LM techniques. This was performed for all combinations and for each of six different signal to noise ratio (SNR) levels which spanned those observed in our patient studies.

For this work the noise added to the simulated MR signal was expressed as a fraction of the peak signal enhancement over the time series. To relate this to that observed clinically, the standard deviation, σ, was measured in an ROI within an enhancing region of the prostate of a difference image [73] made between consecutive DCE-MRI images near the end of the 31-frame acquisition; i.e. having negligible frame-to-frame change in mean signal. The SNR was then defined as the highest mean signal enhancement of that ROI over the unsubtracted time series divided by . This was performed for ten consecutive DCE-MRI prostate studies acquired similarly to those of Table 1 and having suspicious enhancing lesions. SNR values measured with this approach ranged from 16 to 31. The analogous SNR levels used in the simulation were chosen to encompass this range and ranged from 10 to 35.

For each estimation method (VP and LM), for each (Ktrans, kep), or (Ktrans, kep, vp) combination, and for each assumed SNR level, Monte Carlo simulation was performed 500 times for both TM and ETM. The resultant estimated perfusion parameters were then tabulated.

2.5.2. Convergence

To compare the speed of convergence of VP with LM, perfusion analysis was performed using the patient data. For each patient, ten voxels were selected by a radiologist coauthor (AK, >20 years experience in prostate MRI) from the axial section previously identified: five pixels from within the index lesion and five from normal tissue, typically from the same zone of the prostate as the malignant tissue but on the contralateral side. The mean time per iteration was noted in performing the fit for each voxel for both the VP and LM methods. This was done by executing each method 100 times and determining the average computation time. Next, for each voxel the full estimation process was performed and the residual determined after each iteration, where the residual is defined as the root-mean-square (RMS) deviation of the difference between the estimated and acquired perfusion signals. The residual was plotted separately vs. the absolute cumulative computation time. The estimated Ktrans and kep values were noted.

For each voxel the LM estimation processes were initialized with a starting (Ktrans, kep) randomly selected from the range of [0.05 – 2] min−1 for both TM and ETM, and the additional term in ETM, vp was initialized with 0.01. The VP optimization process, which does not need an initial guess, searches the range of [0.03 – 6] min−1 for k̂ep using GSS as described.

3. RESULTS

The fitting performed using our VARPRO-based strategy is illustrated in Figure 2. Figures 2a–b show examples of the cost function, J, (Eq. (8)) plotted vs. kep for two representative voxels from cancerous (a) and normal (b) tissue selected from the study shown in Figure 1 (red and blue points). In each case k̂ep is selected as that corresponding to the minimum of J, and K̂trans is then calculated via Eq. (6). The resultant estimated tissue perfusion signals, pt, generated using the calculated K̂trans and k̂ep values (dashed lines) are plotted vs. time and compared to the acquired perfusion data (solid lines), ct, in Figure 2c for both the cancerous (red) and normal (blue) tissues.

Figure 2.

Cost function (J) vs. kep shown for one voxel in (a) the cancerous region (red line) and one voxel in (b) the non-cancerous region (blue line) in the same patient shown in Figure 1. Black dots correspond to points selected each iteration by Golden Section Search (GSS) method. (c) Estimated perfusion (dashed line) vs. acquired perfusion (solid line) for the two representative voxels shown in Figure 1c–e. The optimum kep values (cost function minimum) found via GSS method and the subsequently computed Ktrans are indicated.

Figure 3 shows box-and-whisker plots which compare the VP and LM estimation methods for a range of assumed SNR levels for the specific case of (Ktrans=0.2 min−1, kep=1.0 min−1, vp =0.01(for ETM)), for both perfusion models, TM (a) and ETM (b). A summary of results for TM over all of the combinations considered is presented in supporting Tables S1, S2. The summary of results for ETM is similar and not presented for brevity.

Figure 3.

The results of the numeric simulation using Monte Carlo simulation. Ktrans (top) and kep (bottom) box-and-whisker plots are depicted for VP and LM for six SNR levels (10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 35). The boxes depict the median, first and third quartiles and the whiskers mark the 10th and 90th percentiles across 500 Monte Carlo samples for the specific combination of Ktrans =0.2 min−1, kep =1.0 min−1, vp =0.01. Figure 3a, b show the results for Tofts and extended Tofts model respectively.

Results illustrating the convergence process for VP vs. LM are shown in supporting Figure S3a–b for Tofts and extended Tofts model respectively. In this figure the ten selected points from Patient #4 were used to demonstrate the convergence process. Five points from the dominant lesion were shown on top and five points from the normal region at the bottom. Each plot shows the results for VP (blue) and LM (red). The plots are representative of those seen for all ten patient studies.

Figure 4a compares the computation times required to attain convergence for the first ten patient studies, with results for Patients #1 to #5 in the first row and #6 to #10 in the second row. Each plot is comprised of comparisons of VP with LM for each of the ten points selected for that patient. For all 100 points in these ten patient cases VP converged. As indicated on top of each plot, in some cases the LM failed to converge, e.g. one point in Patient #2, and these were excluded from the plots. The quantization of times along the abscissa is due to the discrete computation time per iteration for each method. Figure 4b shows the same results for the ETM.

Figure 4.

(a) Absolute computation time for convergence for each point (total of ten points for each patient) shown for VP and LM using the Tofts model. The VP-based method converged for all 100 points. At the top of each plot, the number of points (out of ten) that failed for LM method is noted. The failed points are not shown in the plots. (b) the equivalent plots for the extended Tofts model. (c) Absolute computation time for convergence for all the analyzed points in (a, b). 15 out of 100 points failed to converge for the LM method using the Tofts model and 14 failed using the extended Tofts model. Box-and-whisker plots depict median (dashed line), mean (solid line), first and third quartiles, and 10th and 90th percentiles.

Figure 4c shows the combination of all of the computation time data of Figure 4a, b. Of the 100 points analyzed (ten for each patient) a total of 15 for TM (14 for ETM) failed to converge using the LM method. Box-and whisker plots of the remaining 85 (86 for ETM) comparisons are shown. The mean values using the TM were 0.244 ms for LM and 0.079 ms for VP, and the ratio (0.244/0.079 = 3.08) is taken as the average speed-up in computation time provided by VP. The equivalent numbers for ETM are: LM = 0.477 ms, VP = 0.263 ms, ratio= 0.477/0.263=1.8. Similar results to those in Figure 4 were found for Patients #11-#20. In aggregate, for Patients, #1 - #20 LM failed to converge for the Tofts model for 29 of the 200 points analyzed (14.5%). 7/29 (24.1%) of the failed points occurred in cancerous tissue and 22/29 (75.9%) in normal tissue. Similar results were found for LM for the Extended Tofts Model. The VP method successfully converged for 200/200 points (100%) for both models.

Figure 5 summarizes the results in all twenty patients. Figure 5a is a summary presentation of the estimated Ktrans pharmacokinetic parameters for all voxels analyzed from the twenty patient studies using the VP method for TM and ETM. Figure 5b shows the ROC curve using the pathology results from biopsy and prostatectomy as the standard and calculated based on Ktrans for TM (solid line) and ETM (dashed line). Figure 5c, d shows the same results for kep. The cut-off values for Ktrans and kep, sensitivity, specificity and area under the curve (AUC) are noted on the figure.

Figure 5.

(a) The Ktrans range estimated for normal and cancer region in twenty patients for Tofts and extended Tofts model via the VARPRO technique. (b) The ROC curve based on Ktrans, for Tofts and extended Tofts model. The equivalent information for kep is shown in (c, d). The cut-off values (solid dot on the ROC curve), sensitivity, specificity, and the AUC are noted on the figures (b, d) for TM and ETM.

Results from mpMRI exams that include T2SE, ADC map, and the VARPRO-based perfusion maps are shown for two representative patients in Figure 6 and Figure 7. No artifact related to the VARPRO technique was observed in any of 20 clinical patients.

Figure 6.

66-year-old male (Patient #1) with PSA of 8.7 ng/mL. Prostate biopsy revealed adenocarcinoma, Gleason 4 + 3 = 7 on the right and benign tissue on the left.: (a) T2-weighted spin echo (T2SE) image, and (b) apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) map demonstrate an ill-defined heterogeneous tumor of hypointensity in the right posterolateral peripheral zone at the mid gland (b, arrow). (c–f) Corresponding perfusion abnormality is comparably shown on Ktrans and kep maps from VARPRO (VP) using Tofts model (TM) and extended Tofts model (ETM). The 10 representative points used for computation speed comparisons, are shown in the major tumor and the contralateral side in (c) and (d).

Figure 7.

64-year-old male (Patient #2) with PSA of 11 ng/mL.: (a) T2 signal abnormalities and (b) diffusion restriction (ADC map) in the right posterior peripheral zone (b, arrow). (c, e) Ktrans and (d, f) kep maps from VARPRO (VP) using Tofts model (TM) and extended Tofts model (ETM), reveal hyperenhancing lesion in the right posterolateral peripheral zone. The 10 representative points used for computation speed comparisons are shown in the major tumor and the contralateral side in (c) and (d). Prostate biopsy yielded adenocarcinoma, Gleason score 4+3=7 disease on the right.

4. DISCUSSION

In this work we have demonstrated how the Variable Projection (VARPRO) approach can be used to computationally simplify and improve the reliability of non-linear least squares (NLLS) estimation of the Tofts and extended Tofts model for determining pharmacokinetic parameters, Ktrans and kep, (and vp) from 4D DCE-MRI data. NLLS estimation of perfusion parameters using our VARPRO-based optimization strategy is fundamentally more efficient than alternative NLLS fitting techniques because the search is performed only across one dimension as opposed to throughout a two or three-dimensional space. In our numerical implementation, this strategy enabled an approximate 5× reduction in computation time per iteration (as seen in Figures S2 and Figure 4) and 3× reduction in overall fitting time for TM and 2× reduction for ETM.

The robustness of the perfusion estimation through noise was evaluated with a numeric simulation in which true perfusion values were assumed and noise was added to the simulated MR signals. The SNR levels used in the simulation and the assumed Ktrans, kep, and vp values spanned those found to be typical in prostate DCE-MRI patient studies from our institution. As demonstrated through numeric simulation, VP-based perfusion parameter estimation exhibits comparable accuracy and precision to the standard LM algorithm for a broad range of SNR levels, assuming the LM technique is properly initialized and appropriately terminated. If the LM method is initialized far from the optimum value, for this problem class, the optimization process was commonly observed to fall into suboptimal local minima.

Both VP and LM algorithms have more computation burden for the ETM compared to TM. This is expected due to the more involved computations at each iteration. However, for the VP technique, the computational advantage is less because for TM the term being inverted is a scalar (Eq. (8)) but in Eq. (13), it is a matrix. Thus a bigger step for VP and that is why the speed ratio changes from 3 to 1.8.

The clinical applicability of the VARPRO-based technique was shown by generating perfusion maps from 3D DCE-MRI image sequences from 20 subjects with known or highly suspected prostate cancer. In the patient studies, the LM method failed to converge in 29/200 points (14.5%) for the TM fitting and 30/200 (15%) for ETM fitting. Almost one quarter of these failures were in points within cancer and the remainder in the contralateral normal tissue. On the other hand, the VP-based optimization successfully converged in 200/200 (100%) of the points for both TM and ETM fitting. This ideal performance realized by VP is desirable in any clinical test (including prostate DCE-MRI) where the presence and location of cancer are typically not known prior to the exam. Eliminating technical failure (in this case a failure to converge) is one of the earliest necessary steps in showing efficacy of a possible new clinical test [74].

As described in the Introduction, the VARPRO technique can be applied to the group of non-linear least squares problems that are separable and have a linear combination of nonlinear and/or linear terms. Conceivably this technique could be used to reduce the dimensionality of the search for optimum parameters for other models of perfusion using DCE-MRI data; e.g. [34].

This work does have limitations. One of these is the lack of subject- and system-specific T1- and -mapping (i.e., RF flip angle) before contrast injection. Doing so would provide patient-specific, pre-contrast T1 values and improve the accuracy and precision with which MR signal is converted to concentration. However, many of the findings presented here, such as the basic derivation and simulation studies, did not rely on this conversion process. Another limitation is that motion correction was not used in the VARPRO-based analysis, but motion did not seem problematic in any of the 20 cases. Also, the VP method could conceivably have been compared with other estimation methods. For NLLS this could have been, for example, a trust-region-based approach [33,75]. However, this is still a multi-dimensional optimization, like LM is dependent on the initialization, and has been shown to have problems in convergence similar to LM [33]. Detailed comparison with LLSQ was considered to be beyond the scope of this work. Finally, the relatively low number of patient studies, 20 in this case, is limiting from a statistical power standpoint. However, these were used simply to show the applicability of the VARPRO-based method to prostate DCE-MRI data of known cancer. A larger number would be warranted for any studies of sensitivity, specificity, or accuracy.

In summary, we have shown mathematically how the Variable Projection (VP) approach can be applied to non-linear least squares estimation of perfusion parameters from a time series of DCE-MR images for both the Tofts and Extended Tofts models. The conversion of the problem to a one-dimensional optimization simplifies the search and initialization. Compared to the standard Levenberg-Marquardt method the VP approach provides similar accuracy and noise sensitivity, approximately three-fold reduced computation time, and 100% reliability in convergence in both cancerous and non-cancerous tissues.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Support is acknowledged from Mayo Graduate School, the Mayo Clinic Discovery Translation Program, and from NIH [grant number EB000212, RR018898], and DOD [grant number W81XWH-15-1-0431].

APPENDIX A

Here the steps to derive Eq. (6) from Eq. (5) are shown. Eq. (5) is repeated as Eq. (A.1)

| (A.1) |

where bt(kep) = Aht(kep) Eq. (A.1) can be expanded to:

| (A.2) |

To minimize J, the cost function is differentiated with respect to (Ktrans)* and set to zero:

| (A.3) |

Solving for Ktrans gives the optimum value, K̂trans, as a function of kep:

| (A.4) |

which is Eq. (6) in the text. The final expression for the cost function, Eq. (8), is developed by inserting the expression for K̂trans from Eq. (A.4) into Eq. (A.1) leading to:

| (A.5) |

For brevity bt(kep) is shown as bt in the remainder of the derivation. Eq. (A.5) can be expanded to:

| (A.6) |

Upon noting in the first term that equals unity, the first and second terms of Eq. (A.6) cancel, resulting in:

| (A.7) |

Because is independent of kep it can be dropped for the optimization, resulting in Eq. (8).

APPENDIX B

The VARPRO technique can similarly be applied to the extended Tofts Model (ETM). Starting with Eq. (10) from the text, repeated here as Eq. (B.1):

| (B.1) |

The cost function J is then:

| (B.2) |

which can be expanded (similar to Eq. (A.2)) to the expression shown here:

| (B.3) |

where Bt(kep) is shown as Bt for brevity. The only difference vs. Eq. (A.2) is that is a vector replacing Ktrans and Bt is a matrix replacing vector bt. To minimize J, the cost function is differentiated with respect to x* and set to zero:

| (B.4) |

Solving for x gives the optimum value, x̂, as a function of kep:

| (B.5) |

Insertion into Eq. (B.2), expansion, and simplification similar to that in Appendix A leads to the final expression for the cost function, dependent only on the single variable kep and the final term is dropped to form Eq. (13) in the text.

| (B.6) |

The optimum value for kep, can be found by line search and then used in Eq. (B.5) to calculate the optimum Ktrans, vp that are imbedded in x̂.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Leach MO, Brindle KM, Evelhoch JL, Griffiths JR, Horsman MR, Jackson A, et al. The assessment of antiangiogenic and antivascular therapies in early-stage clinical trials using magnetic resonance imaging: issues and recommendations. Br J Cancer. 2005;92:1599–610. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Larsson HB, Stubgaard M, Frederiksen JL, Jensen M, Henriksen O, Paulson OB. Quantitation of blood-brain barrier defect by magnetic resonance imaging and gadolinium-DTPA in patients with multiple sclerosis and brain tumors. Magn Reson Med. 1990;16:117–31. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910160111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brix G, Semmler W, Port R, Schad LR, Layer G, Lorenz WJ. Pharmacokinetic parameters in CNS Gd-DTPA enhanced MR imaging. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1991;15:621–8. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199107000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tofts PS, Brix G, Buckley DL, Evelhoch JL, Henderson E, Knopp MV, et al. Estimating kinetic parameters from dynamic contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MRI of a diffusable tracer: standardized quantities and symbols. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1999;10:223–32. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2586(199909)10:3<223::aid-jmri2>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tofts PS, Kermode AG. Measurement of the blood-brain barrier permeability and leakage space using dynamic MR imaging. 1. Fundamental concepts. Magn Reson Med. 1991;17:357–67. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910170208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tofts PS. Modeling tracer kinetics in dynamic Gd-DTPA MR imaging. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1997;7:91–101. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1880070113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Padhani AR, Leach MO. Antivascular cancer treatments: functional assessments by dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. Abdom Imaging. 2005;30:325–42. doi: 10.1007/s00261-004-0265-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schmid VJ, Whitcher B, Padhani AR, Taylor NJ, Yang G-Z. Bayesian methods for pharmacokinetic models in dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2006;25:1627–36. doi: 10.1109/tmi.2006.884210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fütterer JJ, Heijmink SWTPJ, Scheenen TWJ, Veltman J, Huisman HJ, Vos P, et al. Prostate cancer localization with dynamic contrast-enhanced MR imaging and proton MR spectroscopic imaging. Radiology. 2006;241:449–58. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2412051866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sourbron SP, Buckley DL. On the scope and interpretation of the Tofts models for DCE-MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2011;66:735–45. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bonekamp D, Jacobs MA, El-Khouli R, Stoianovici D, Macura KJ. Advancements in MR imaging of the prostate: from diagnosis to interventions. Radiographics. 2011;31:677–703. doi: 10.1148/rg.313105139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ng CS, Waterton JC, Kundra V, Brammer D, Ravoori M, Han L, et al. Reproducibility and comparison of DCE-MRI and DCE-CT perfusion parameters in a rat tumor model. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2012;11:279–88. doi: 10.7785/tcrt.2012.500296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li X, Huang W, Rooney WD. Signal-to-noise ratio, contrast-to-noise ratio and pharmacokinetic modeling considerations in dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. Magn Reson Imaging. 2012;30:1313–22. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2012.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heye T, Davenport MS, Horvath JJ, Feuerlein S, Breault SR, Bashir MR, et al. Reproducibility of dynamic contrast-enhanced MR imaging. Part I. Perfusion characteristics in the female pelvis by using multiple computer-aided diagnosis perfusion analysis solutions. Radiology. 2013;266:801–11. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12120278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heye T, Merkle EM, Reiner CS, Davenport MS, Horvath JJ, Feuerlein S, et al. Reproducibility of dynamic contrast-enhanced MR imaging. Part II. Comparison of intra- and interobserver variability with manual region of interest placement versus semiautomatic lesion segmentation and histogram analysis. Radiology. 2013;266:812–21. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12120255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang N, Zhang L, Qiu B, Meng L, Wang X, Hou BL. Correlation of volume transfer coefficient Ktrans with histopathologic grades of gliomas. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2012;36:355–63. doi: 10.1002/jmri.23675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heye T, Boll DT, Reiner CS, Bashir MR, Dale BM, Merkle EM. Impact of precontrast T10 relaxation times on dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI pharmacokinetic parameters: T10 mapping versus a fixed T10 reference value. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2014;39:1136–45. doi: 10.1002/jmri.24262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang W, Chen Y, Fedorov A, Li X, Jajamovich GH, Malyarenko DI, et al. The impact of arterial input function determination variations on prostate dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging pharmacokinetic modeling: a multicenter data analysis challenge. Tomography. 2016;2:56–66. doi: 10.18383/j.tom.2015.00184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sanz-Requena R, Martí-Bonmatí L, Pérez-Martínez R, García-Martí G. Dynamic contrast-enhanced case-control analysis in 3T MRI of prostate cancer can help to characterize tumor aggressiveness. Eur J Radiol. 2016;85:2119–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2016.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dikaios N, Atkinson D, Tudisca C, Purpura P, Forster M, Ahmed H, et al. A comparison of Bayesian and non-linear regression methods for robust estimation of pharmacokinetics in DCE-MRI and how it affects cancer diagnosis. Comput Med Imaging Graph. 2017;56:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.compmedimag.2017.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keil VC, Mädler B, Gieseke J, Fimmers R, Hattingen E, Schild HH, et al. Effects of arterial input function selection on kinetic parameters in brain dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI. Magn Reson Imaging. 2017;40:83–90. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2017.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simoncic U, Leibfarth S, Welz S, Schwenzer N, Schmidt H, Reischl G, et al. Comparison of DCE-MRI kinetic parameters and FMISO-PET uptake parameters in head and neck cancer patients. Med Phys. 2017;44:2358–68. doi: 10.1002/mp.12228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen X, Xie T, Fang J, Xue W, Tong H, Kang H, et al. Quantitative in vivo imaging of tissue factor expression in glioma using dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI derived parameters. Eur J Radiol. 2017;93:236–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2017.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ocak I, Bernardo M, Metzger G, Barrett T, Pinto P, Albert PS, et al. Dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI of prostate cancer at 3 T: a study of pharmacokinetic parameters. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;189:849. doi: 10.2214/AJR.06.1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alonzi R, Padhani AR, Allen C. Dynamic contrast enhanced MRI in prostate cancer. Eur J Radiol. 2007;63:335–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2007.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oto A, Yang C, Kayhan A, Tretiakova M, Antic T, Schmid-Tannwald C, et al. Diffusion-weighted and dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI of prostate cancer: correlation of quantitative MR parameters with Gleason score and tumor angiogenesis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;197:1382–90. doi: 10.2214/AJR.11.6861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fedorov A, Fluckiger J, Ayers GD, Li X, Gupta SN, Tempany C, et al. A comparison of two methods for estimating DCE-MRI parameters via individual and cohort based AIFs in prostate cancer: a step towards practical implementation. Magn Reson Imaging. 2014;32:321–9. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2014.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fennessy FM, Fedorov A, Penzkofer T, Kim KW, Hirsch MS, Vangel MG, et al. Quantitative pharmacokinetic analysis of prostate cancer DCE-MRI at 3T: comparison of two arterial input functions on cancer detection with digitized whole mount histopathological validation. Magn Reson Imaging. 2015;33:886–94. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2015.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Papoulis A. Probability, Random Variables, and Stochastic Processes. McGraw-Hill; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Levenberg K. A Method for the solution of certain non-linear problems in least squares. Q Appl Math. 1944;11:164–8. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marquardt DW. An algorithm for least-squares estimation of nonlinear parameters. J Soc Ind Appl Math. 1963;11:431–41. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Murase K. Efficient method for calculating kinetic parameters using T1-weighted dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2004;51:858–62. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ahearn TS, Staff RT, Redpath TW, Semple SIK. The use of the Levenberg-Marquardt curve-fitting algorithm in pharmacokinetic modelling of DCE-MRI data. Phys Med Biol. 2005;50:N85–92. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/50/9/N02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kallehauge JF, Sourbron S, Irving B, Tanderup K, Schnabel JA, Chappell MA. Comparison of linear and nonlinear implementation of the compartmental tissue uptake model for dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2017;77:2414–23. doi: 10.1002/mrm.26324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Flouri D, Lesnic D, Sourbron SP. Fitting the two-compartment model in DCE-MRI by linear inversion. Magn Reson Med. 2016;76:998–1006. doi: 10.1002/mrm.25991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Feng D, Ho D, Chen K, Wu LC, Wang JK, Liu RS, et al. An evaluation of the algorithms for determining local cerebral metabolic rates of glucose using positron emission tomography dynamic data. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 1995;14:697–710. doi: 10.1109/42.476111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Golub GH, Pereyra V. The differentiation of pseudo-inverses and nonlinear least squares problems whose variables separate. SIAM J Numer Anal. 1973;10:413–32. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boada F, Liang Z-P, Haacke EM. Improved parametric reconstruction using variable projection optimization. Inverse Probl. 1998;14:19–27. [Google Scholar]

- 39.van der Veen JWC, de Beer R, Luyten PR, van Ormondt D. Accurate quantification ofin vivo31P NMR signals using the variable projection method and prior knowledge. Magn Reson Med. 1988;6:92–8. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910060111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sima DM, Van Huffel S. Separable nonlinear least squares fitting with linear bound constraints and its application in magnetic resonance spectroscopy data quantification. J Comput Appl Math. 2007;203:264–78. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mullen KM, van Stokkum IHM. The variable projection algorithm in time-resolved spectroscopy, microscopy and mass spectrometry applications. Numer Algorithms. 2009;51:319–40. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Haldar JP, Anderson J, Sun S. Maximum likelihood estimation of T1 relaxation parameters using VARPRO. Proc 15th Annu Meet ISMRM; 2007. p. 41. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Trzasko JD, Mostardi PM, Riederer SJ, Manduca A. Estimating T1 from multichannel variable flip angle SPGR sequences. Magn Reson Med. 2013;69:1787–94. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rauscher I, Eiber M, Ganter C, Martirosian P, Safi W, Umgelter A, et al. Evaluation of T1ρ as a potential MR biomarker for liver cirrhosis: comparison of healthy control subjects and patients with liver cirrhosis. Eur J Radiol. 2014;83:900–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2014.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hernando D, Haldar JP, Sutton BP, Ma J, Kellman P, Liang Z-P. Joint estimation of water/fat images and field inhomogeneity map. Magn Reson Med. 2008;59:571–80. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hernando D, Kellman P, Haldar JP, Liang Z-P. Robust water/fat separation in the presence of large field inhomogeneities using a graph cut algorithm. Magn Reson Med. 2010;63:79–90. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bydder M, Yokoo T, Yu H, Carl M, Reeder SB, Sirlin CB. Constraining the initial phase in water fat separation. Magn Reson Imaging. 2011;29:216–21. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2010.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yin X, Guo Y, Li W, Huo E, Zhang Z, Nicolai J, et al. Chemical shift MR imaging methods for the quantification of transcatheter lipiodol delivery to the liver: preclinical feasibility studies in a rodent model. Radiology. 2012;263:714–22. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12111916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Berglund J, Kullberg J. Three-dimensional water/fat separation and T2* estimation based on whole-image optimization--application in breathhold liver imaging at 1. 5 T. Magn Reson Med. 2012;67:1684–93. doi: 10.1002/mrm.23185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stinson EG, Trzasko JD, Fletcher JG, Riederer SJ. Dual echo Dixon imaging with a constrained phase signal model and graph cuts reconstruction. Magn Reson Med. 2017;78:2203–15. doi: 10.1002/mrm.26620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhao B, Setsompop K, Ye H, Cauley SF, Wald LL. Maximum likelihood reconstruction for magnetic resonance fingerprinting. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2016;35:1812–23. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2016.2531640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Riabkov DY, Di Bella EVR. Estimation of kinetic parameters without input functions: analysis of three methods for multichannel blind identification. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2002;49:1318–27. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2002.804588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Riabkov DY, Di Bella EVR. Blind identification of the kinetic parameters in three-compartment models. Phys Med Biol. 2004;49:639–64. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/49/5/001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.National Cancer Institute. Prostate Cancer—Patient Version. https://www.cancer.gov/types/prostate.

- 55.Delongchamps NB, Rouanne M, Flam T, Beuvon F, Liberatore M, Zerbib M, et al. Multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging for the detection and localization of prostate cancer: combination of T2-weighted, dynamic contrast-enhanced and diffusion-weighted imaging. BJU Int. 2011;107:1411–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09808.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.De Rooij M, Hamoen EHJ, Fütterer JJ, Barentsz JO, Rovers MM. Accuracy of multiparametric MRI for prostate cancer detection: a meta-analysis. Am J Roentgenol. 2014;202:343–51. doi: 10.2214/AJR.13.11046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Weinreb JC, Barentsz JO, Choyke PL, Cornud F, Haider MA, Macura KJ, et al. PI-RADS prostate imaging – reporting and data system: 2015, version 2. Eur Urol. 2016;69:16–40. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.08.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kershaw LE, Buckley DL. Precision in measurements of perfusion and microvascular permeability with T1-weighted dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2006;56:986–92. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fennessy FM, Fedorov A, Gupta SN, Schmidt EJ, Tempany CM, Mulkern RV. Practical considerations in T1 mapping of prostate for dynamic contrast enhancement pharmacokinetic analyses. Magn Reson Imaging. 2012;30:1224–33. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2012.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Winfield JM, Payne GS, Weller A, DeSouza NM. DCE-MRI, DW-MRI, and MRS in cancer: challenges and advantages of implementing qualitative and quantitative multi-parametric imaging in the clinic. Top Magn Reson Imaging. 2016;25:245–54. doi: 10.1097/RMR.0000000000000103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bansal S, Gupta NP, Yadav R, Khera R, Ahlawat K, Gautam D, et al. Multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging-transrectal ultrasound fusion prostate biopsy: a prospective, single centre study. Indian J Urol. 2017;33:134–9. doi: 10.4103/0970-1591.203414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rouvière O, Vitry T, Lyonnet D. Imaging of prostate cancer local recurrences: why and how? Eur Radiol. 2010;20:1254–66. doi: 10.1007/s00330-009-1647-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kitajima K, Murphy RC, Nathan MA, Froemming AT, Hagen CE, Takahashi N, et al. Detection of recurrent prostate cancer after radical prostatectomy: comparison of 11C-Choline PET/CT with pelvic multiparametric MR imaging with endorectal coil. J Nucl Med. 2014;55:223–32. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.113.123018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kargar S, Stinson EG, Borisch EA, Froemming AT, Kawashima A, Mynderse LA, Trzasko JDRS. Robust and efficient pharmacokinetic parameter estimation: application to prostate DCE-MRI. Proc Intl Soc Mag Reson Med, ISMRM. 2016:2463. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kargar S, Stinson EG, Borisch EA, Froemming AT, Kawashima A, Mynderse LA, et al. Robust and efficient perfusion parameter estimation for DCE-MRI of the prostate utilizing the variable projection (VARPRO) method. Proc Intl Soc Mag Reson Med. 2017:4385. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Coveney PV. Scientific Grid computing. Philos Trans A Math Phys Eng Sci. 2005;363:1707–13. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2005.1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Froemming AT, Borisch EA, Trzasko JD, Grimm RC, Manduca A, Young P, et al. The application of sparse reconstruction to high spatio-temporal resolution dynamic contrast enhanced MRI of the prostate: initial clinical experience with effect on image and parametric perfusion characteristic quality. Proc Intl Soc Mag Reson Med. 2015:1169. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Haider CR, Hu HH, Campeau NG, Huston J, Riederer SJ. 3D high temporal and spatial resolution contrast-enhanced MR angiography of the whole brain. Magn Reson Med. 2008;60:749–60. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Riederer SJ, Tasciyan T, Farzaneh F, Lee JN, Wright RC, Herfkens RJ. MR fluoroscopy: technical feasibility. Magn Reson Med. 1988;8:1–15. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910080102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Frahm J, Haase A, Matthaei D. Rapid NMR imaging of dynamic processes using the FLASH technique. Magn Reson Med. 1986;3:321–7. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910030217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.de Bazelaire CM, Duhamel GD, Rofsky NM, Alsop DC. MR imaging relaxation times of abdominal and pelvic tissues measured in vivo at 3. 0 T: preliminary results. Radiology. 2004;230:652–9. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2303021331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Parker GJM, Roberts C, Macdonald A, Buonaccorsi GA, Cheung S, Buckley DL, et al. Experimentally-derived functional form for a population-averaged high-temporal-resolution arterial input function for dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2006;56:993–1000. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.NEMA standards publication MS 1-2008 (R2014) determination of signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) in diagnostic magnetic resonance imaging. 2008;2008:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Thornbury JR Eugene W. Caldwell Lecture. Clinical efficacy of diagnostic imaging: love it or leave it. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1994;162:1–8. doi: 10.2214/ajr.162.1.8273645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gill AB, Black RT, Bowden DJ, Priest AN, Graves MJ, Lomas DJ. An investigation into the effects of temporal resolution on hepatic dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI in volunteers and in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Phys Med Biol. 2014;59:3187–200. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/59/12/3187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.