Abstract

Background

Snail-borne parasitic diseases, such as angiostrongyliasis, clonorchiasis, fascioliasis, fasciolopsiasis, opisthorchiasis, paragonimiasis and schistosomiasis, pose risks to human health and cause major socioeconomic problems in many tropical and sub-tropical countries. In this review we summarize the core roles of snails in the life cycles of the parasites they host, their clinical manifestations and disease distributions, as well as snail control methods.

Main body

Snails have four roles in the life cycles of the parasites they host: as an intermediate host infected by the first-stage larvae, as the only intermediate host infected by miracidia, as the first intermediate host that ingests the parasite eggs are ingested, and as the first intermediate host penetrated by miracidia with or without the second intermediate host being an aquatic animal. Snail-borne parasitic diseases target many organs, such as the lungs, liver, biliary tract, intestines, brain and kidneys, leading to overactive immune responses, cancers, organ failure, infertility and even death. Developing countries in Africa, Asia and Latin America have the highest incidences of these diseases, while some endemic parasites have developed into worldwide epidemics through the global spread of snails. Physical, chemical and biological methods have been introduced to control the host snail populations to prevent disease.

Conclusions

In this review, we summarize the roles of snails in the life cycles of the parasites they host, the worldwide distribution of parasite-transmitting snails, the epidemiology and pathogenesis of snail-transmitted parasitic diseases, and the existing snail control measures, which will contribute to further understanding the snail-parasite relationship and new strategies for controlling snail-borne parasitic diseases.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s40249-018-0414-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Snail-borne parasitic diseases, Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, Snail control

Multilingual abstracts

Please see Additional file 1 for translations of the abstract into the five official working languages of the United Nations.

Background

Snail-borne parasitic diseases (SBPDs) are major parasitic diseases that remain important public health issues worldwide, particularly in impoverished countries. Millions of people in approximately 90 countries have suffered from SBPDs, in which snails serve as the transmitting vectors and intermediate hosts (Table 1). Thus, the elimination or control of snails may be an alternative approach to the focused control of SBPDs and may effectively interrupt the transmission of SBPDs. Previous studies have documented the relationship between certain parasites and their intermediate host snails, but few studies have focused on the crucial importance of snails in the complex interactions between snails and snail-borne parasites [1]. Moreover, a better understanding of the basic biology of SBPDs and the vectors that transmit them are needed to explain the expanding geographical distribution of these diseases. This review discusses our current knowledge of SBPDs, with a particular focus on new evidence of the global distribution and the physical control of parasite-transmitting snails as well as the epidemiology and clinical aspects of SBPDs.

Table 1.

The distribution of snails that can transmit parasitic diseases and the parasites they can carry

| Categories | Distribution | Ac | Cs | Fb | Fh | Of | Ov | Pw | Sh | Si | Sj | Smal | Sman | Smek | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Achatinidae | |||||||||||||||

| Achatina fulica | East Africa, America, Brazil, China, Guam, India, Japan, Madagascar, Mauritius, Pacific Islands, Seychelles, Southeast Asia, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Zanzibar | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [21, 22, 77] |

| Ampullariidae | |||||||||||||||

| Pila ampullacea | Thailand | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [21] |

| Pi. angelica | Thailand | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [22] |

| Pi. gracilis | Thailand | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [21] |

| Pi. pesmei | Thailand | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [23] |

| Pi. polita | Thailand | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [21] |

| Pi. scutata | Malaysia | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [21] |

| Pi. turbinis | Thailand | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [21] |

| Pomacea canaliculata | Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, California, China, Dominican Republic, Florida, Guam, Hawaii, Indonesia, Japan, Korea, Laos, Malaysia, New Nyaya, North Korea, Paraguay, Philippines, Singapore, Sri Lanka, Texas, Thailand, Uruguay, Vietnam | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [21, 77] |

| Po. lineata | Brazil | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [3] |

| Ancylidae | |||||||||||||||

| Ferrissia tenuis | India | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [100] |

| Ariophantidae | |||||||||||||||

| Girasia peguensis | China | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [21] |

| Hemiplecta distincta | Thailand | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [23] |

| Microparmarion malayanus | Burma, Malaysia | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [21] |

| Assimineidae | |||||||||||||||

| Assiminea latericea | China | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [11] |

| Bithyniidae | |||||||||||||||

| Alocinma longicornis | China | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [11] |

| Bithynia fuchsiania | China | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [12] |

| Bit. funiculate | Laos, Thailand | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [13] |

| Bit. goniompharus | Laos, Thailand | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [13] |

| Bit. inflate | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Bit. leachi | Germany | + | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [14] |

| Bit. misella | China | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [12] |

| Bit. siamensis | Cambodia, Laos, Thailand | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [13, 15] |

| Bit. troscheli | Russia | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [16] |

| Parafossarulus eximius | China | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [17] |

| Pa. striatulus | China | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [12] |

| Pa. sinensis | China | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [18] |

| Pa. anomalospiralis | China | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [19] |

| Pa. manchouricus | China, Japan, Korea | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [20] |

| Bradybaenida | |||||||||||||||

| Bradybaena despecta | China, East Timor, Japan, Myanmar | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [21] |

| Br. ravida | China, North Korea, Japan, Russia, | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [21] |

| Br. circulus | Japan | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [21] |

| Br. similaris | China, Brazil, East Timor, Japan, Pacific Islands | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [21, 101] |

| Euhadra quaesita | Japan | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [21] |

| Plectotropis applanata | China | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [21] |

| Buccinidae | |||||||||||||||

| Clea helena | Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [23, 102] |

| Camaenidae | |||||||||||||||

| Satsuma mercatoria | Pacific Islands | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [21] |

| Camaena cicatricosa | China, Japan, Myanmar, Pacific Islands, Vietnam | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [21] |

| Cyclophoridae | |||||||||||||||

| Pupina complanata | America, Malaysia | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [21] |

| Helicarionidae | |||||||||||||||

| Parmarion martensi | Japan, Hawaii | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [103] |

| Lymnaeidae | |||||||||||||||

| Fossaria cubensis | America, Bolivia, Caribbean Islands, Colombia, Cuba, Mexico, Uruguay, Venezuela | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [43] |

| Galba cousin | Colombia, Ecuador, Venezuela | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [43] |

| G. glaticallsformis | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| G. pervia | China | + | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [44] |

| G. truncatula | Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, France, Italy, Mexico, Peru, Portugal, Spain, Switzerland, the Netherlands, Venezuela | + | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [43, 45–47, 104, 105] |

| Lymnaea bulimoides | Mexico | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [46] |

| Ly. diaphana | Argentina, Chile, Peru | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [43] |

| Ly. fuscus | Sweden | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [48] |

| Ly. humilis | Mexico | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [46] |

| Ly. japonica | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Ly. neotropica | Argentina, Peru | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [43] |

| Ly. obrussa | Mexico | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [46] |

| Ly. ollula | Japan, Korea | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [49] |

| Ly. palustris | Sweden | + | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [21, 48] |

| Ly. rupestris | Brazil | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [43] |

| Ly. tomentosa | Australia | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [50] |

| Ly. viatrix | Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Mexico, Peru, Uruguay | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [43, 46] |

| Ly. viridis | Australia, China, Korea, Vietnam | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [49, 50] |

| Omphiscola glabra | France, Germany, Italy | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [45, 47] |

| Pseudosuccinea columella | Africa, Australia, Caribbean Islands, Central America, Europe, New Zealand, North America, South America, Tahiti | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [10, 51] |

| Radix auricularia | China, Czech Republic, France, Germany, Iceland, Italy, Korea, Poland, | + | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [11, 47, 52, 53] |

| Ra. lagotis | Austria, China, Czech Republic | + | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [11, 45] |

| Ra. natalensis | Egypt, Senegal | + | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [54] |

| Ra. ovata (Ra. peregra) | Czech Republic, France, Iceland, Italy, Poland, Spain, the Netherlands | + | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [45, 47, 53] |

| Ra. plicatula | – | + | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Ra. swinhoei | China, Japan, Poland, Thailand, Vietnam | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [55] |

| Stagnicola palustris | Italy | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [47] |

| Physidae | |||||||||||||||

| Physa acuta | Japan, Peru | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [21, 106] |

| Planorbidae | |||||||||||||||

| Biomphalaria alexandrina | Egypt, Libya, Sudan | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | [24] |

| Bio. amazonica | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | – |

| Bio. andecola | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | – |

| Bio. arabica | Saudi Arabia | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | [25] |

| Bio. camerunensis | Cameroon | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | [26] |

| Bio. choanomphala | Albert, Kyoga, Victoria | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | [27] |

| Bio. glabrata | Caribbean Islands, south America | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | [24] |

| Bio. helophila | Cuba, Peru | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | [28, 106] |

| Bio. intermedia | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | – |

| Bio. kuhniana | China, Venezuela | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | [29] |

| Bio. obstructa | Cuba | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | [28] |

| Bio. occidentalis | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | – |

| Bio. peregrine | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | – |

| Bio. pfeiffei | Africa, Chad | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | [30] |

| Bio. prona | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | – |

| Bio. schrommi | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | – |

| Bio. smithi | Lake Edward | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | [27] |

| Bio. stanleyi | Lake Albert | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | [27] |

| Bio. straminea | Argentina, Brazil, Caribbean, China, Grenada, Guadeloupe, Martinique, Paraguay, St Lucia, Uruguay | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | [29] |

| Bio. sudanica | lakes and rivers through central and eastern Africa | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | [31] |

| Bio. temascalensis | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | – |

| Bio. tenagophila | Brazil | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | [29] |

| Bulinus africanus | Kenya | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | [32] |

| Bu. bavayi | Madagascar | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | [33] |

| Bu. beccari | Saudi Arabia | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | [25] |

| Bu. camerunensis | Cameroon | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | [34] |

| Bu. contortus | Portugal | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | [35] |

| Bu. crystallinus | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – |

| Bu. forakalii | Cameroon, Chad, Gabon, Rhodesia, Senegal, Tanzania, Zaire | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | + | – | – | – | – | [25, 30, 36] |

| Bu. globosus | Cameroon, Kenya, Lake Victoria area, Nigeria, Pemba, Senegal, Unguja Island, Zanzibar | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | + | – | – | – | – | [32, 34, 37, 38] |

| Bu. liratus | Madagascar | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | [33] |

| Bu. nasutus | Kenya, Zanzibar | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | [32, 37] |

| Bu. nyassanus | Denmark, Malawi | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | [39] |

| Bu. obtusispira | Madagascar | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | [33] |

| Bu. reticulatus | Cameroon | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | [37] |

| Bu. rohlfsi | Nigeria | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | [38] |

| Bu. senegalensis | Cameroon, Senegal | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | [34] |

| Bu. tropicus | Cameroon | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | [34] |

| Bu. truncatus | Cameroon, Chad, Egypt, Nile Delta, North Africa, Portugal, Saudi Arabia, Senegal, Sub-Saharan Africa, Sudan | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | + | – | – | – | – | [25, 30, 34, 35] |

| Bu. ugandae | Lake Victoria | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | [32] |

| Bu. umbilicatus | Senegal | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | [34] |

| Bu. wright | Saudi Arabia | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | [25] |

| Gyraulus convexiusculus | China, India, Korea, Thailand | + | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [11, 22, 40, 41] |

| Hippeutis cantori | China, Korea | + | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [11, 41] |

| H. umbilicalis | Bangladesh, China, Thailand | + | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [11, 42] |

| Indoplanorbis exustus | Camroon, Malaysia, Thailand | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [21, 22, 107] |

| Lanistes carinatus | Thailand | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [23] |

| La. purpureus | Kenya | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | [32] |

| Planorbarius metidjensis | Portugal | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | [35] |

| Segmentina hemisphaerula | Korea, Thailand | + | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [41] |

| Seg. trochoideus | Bangladesh, Thailand | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [42] |

| Pleuroseridae | |||||||||||||||

| Semisulcospira amurensis | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Sem. cancellata | China | + | + | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | [108] |

| Sem. kurodai | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Sem. libertina | China | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | [109] |

| Sem. mandarina | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Sem. peregrinorum | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Sem. toucheana | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Pomatiopsidae | |||||||||||||||

| Neotricula aperta | Cambodia, Laos, Thailand | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | [59] |

| Oncomelania hupensis | China, Indonesia, Philippines | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | [60] |

| Robertsiella kaporensis | Malaysia | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | [110] |

| Subulinidae | |||||||||||||||

| Allopeas kyotoensis | Japan | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [21] |

| Opeas javanicum | Pacific Islands | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [21] |

| Subulina octona | Brazil, Pacific Islands | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [21, 111] |

| Succineidae | |||||||||||||||

| Succinea lauta | Japan | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [21] |

| Su. pfeifferi | Norway | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [112] |

| Thiaridae | |||||||||||||||

| Melanoides tuberculata | America, Australia, Brazil, China, Egypt, India, Iran, Israel, Jordan, Kenya, Mexico, Saudi Arabia, Thailand, United Arab Emirates, Venezuela | – | + | – | – | – | – | + | + | – | – | – | – | – | [22, 32, 56, 57] |

| Tarebia granifera (M. granifera) | South-East Asia, North and South America and Africa | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | [58] |

| Viviparidae | |||||||||||||||

| Bellamya aeruginosa | China | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [21] |

| Be. ingallsiana | Malaysia | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [21] |

| Be. quadrata | China | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [113] |

| Cipangopaludina chinensis | China, Japan, North Korea | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [21] |

| Filopaludina martensi martensi | Thailand | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [23] |

| F. sumatrensis polygramma | Thailand | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [23] |

| Sinotaia quadrata | Japan | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [114] |

Ac = Angiostrongylus cantonensis; Cs = Clonorchis sinensis; Fb = Fasciolopsis buski; Fh = Fasciola hepatica; Of = Opisthorchis felineus; Ov = Opisthorchis viverrini; Pw = Paragonimus westermani; Sh = Schistosoma haematobium; Si = Schistosoma intercalatum; Sj = Schistosoma japonicum; Smal = Schistosoma malayensis; Sman = Schistosoma mansoni; Smek = Schistosoma mekongi

Roles of snails in the life cycles of parasites

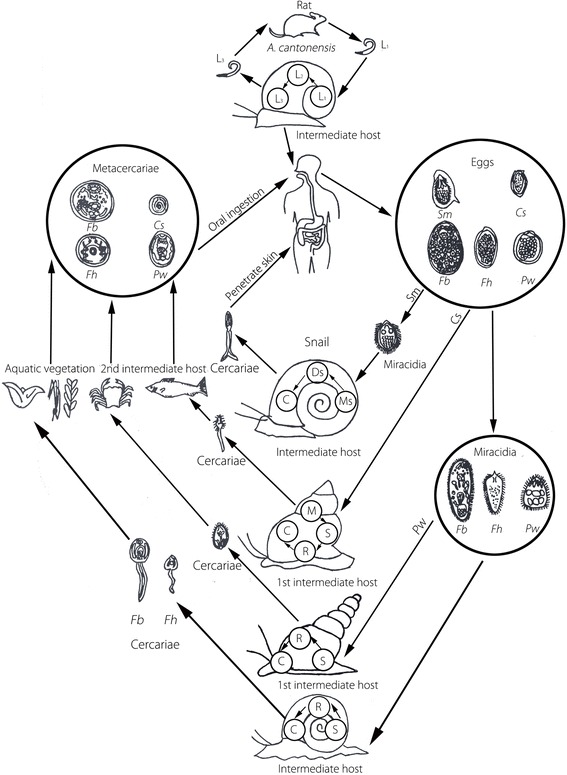

Based on the roles of snails and the developmental stages of the parasites they host, SBPDs can be divided into five groups (Fig. 1). Group I includes Nematoda diseases in which snails act as an intermediate host, a representative pathogen for which is Angiostrongylus cantonensis. The first-stage larvae (L1) of A. cantonensis are shed into the external environment via rat faeces (definitive host) [2]. The snails become infected when they ingest the infected rat faeces or when these larvae penetrate their body wall or respiratory pores [3]. L1 moult twice into second-stage (L2) and third-stage larvae (L3) in the mollusc tissue [3]. The other four groups are associated with Trematoda. In group II, snails serve as the only intermediate host and become infected by penetrating miracidia. A typical example of a group II SBPD is Schistosoma mansoni. The eggs of the parasite hatch and release ciliated miracidia that penetrate the snails and asexually replicate through two sporocyst generations (mother and daughter sporocyst stages). Finally, thousands of cercariae are shed into the water, that infect humans who come into contact with the contaminated water [4]. In group III, snails are the first intermediate hosts and become infected by ingesting parasite eggs. Clonorchis sinensis is a typical species of this group. In these parasites, after miracidia are released from the eggs they subsequently develop into sporocysts and finally form cercariae that then infect freshwater fish, which are the second intermediate host [5]. In group IV, snails may become the first intermediate host and are infected by miracidia [6]. For example, Paragonimus westermani eggs hatch and release miracidia into the water, which undergo various stages within the snails. The miracidia develop into sporocysts, rediae and cercariae successively, then invade a second intermediate host, such as crabs and crayfish [6]. In group V, snails are the first intermediate host and are infected by penetrating miracidia, with the second intermediate host being aquatic plants [7, 8], such as Fasciolopsis buski and F. hepatica. The eggs hatch into ciliated miracidia that swim to snails such as P. westermani [9]. After invading the snails, they transform into sporocysts, rediae, and then cercariae that encyst on aquatic vegetation and become metacercariae [7, 8, 10].

Fig. 1.

Schematic illustration of the life cycles of six snail-borne parasites, including A. cantonensis, C. sinensis, F. buski, F. hepatica, P. westermani and S. mansoni. C: Ceceariae; Cs: Clonorchis sinensis; Ds: Daughter sporocysts; Fb: Fasciolopsis buski; Fh: Fasciola hepatica; L1: first-stage larvae; L2: second-stage larvae; L3: third-stage larvae; M: Miracidia; Ms.: Mother sporocysts; Pw: Paragonimus westermani; R: Rediae; S: Sporocysts; Sm: Schistosoma mansoni

In summary, snails are the only intermediate hosts of A. cantonensis and S. mansoni, while they serve as the first intermediate hosts of C. sinensis, P. westermani, F. buski, and F. hepatica. The parasites undergo several developmental stages within the snails, demonstrating the vital role of snails in SBPDs (Fig. 1).

Global distribution of parasite-transmitting snails

Terrestrial and freshwater snails are intermediate hosts in the life cycles of various parasites. The distributions of 136 snail species from 18 families are described in Table 1.

Bithyniidae snails are intermediate hosts of C. sinensis, Opisthorchis felineus and O. viverrini and are endemic to several geographical regions in Asia and Europe, including Cambodia, China, Germany, Japan, Korea, Laos, Russia and Thailand [11–20]. Planorbidae snails are the intermediate hosts of F. buski, Schistosoma haematobium, S. intercalatum and S. mansoni. These snails are widespread throughout Africa, Asia and Latin America and serve as intermediate hosts of F. hepatica [11, 21–42]. Lymnaeidae snails are primarily found in Africa, Asia, North America and South America [10, 11, 21, 43–55]. Thiaridae snails, which are reported to serve as intermediate hosts for many parasites, such as P. westermani, C. sinensis and S. haematobium, are distributed worldwide, but primarily in Africa, Asia, Oceania, North America and South America [22, 32, 56–58] (Table 1).

Most parasites require a specific snail species as an intermediate host. For example, the life cycles of Schistosoma japonicum and S. mekongi require Oncomelania hupensis and Neotricula aperta as their intermediate hosts, respectively. These snails have limited distributions: N. aperta is endemic to Cambodia, Laos and Thailand [59], and O. hupensis is found only in China, Indonesia and the Philippines [60]. Pomacea canaliculata, which is native to South America, was introduced to China in the 1980s and has since replaced Achatina fulica to become a major intermediate host that is the primary cause of A. cantonensis infection in humans in China [61].

To some extent, a correlation exists between the distribution of snails and parasitic diseases. Mapping the distribution of snails may help clarify their interactions with parasitic diseases and identify environmental factors that will help better detect and predicting the prevalence of these diseases. Geographic information systems (GISs) and remote sensing (RS) techniques have been increasingly used to map and model the distribution of snails. These techniques, which provide information on snail habitats and dispersal areas and to predict snail-infested regions, have been utilized masterfully in several areas, including Africa [62]. Spatial-temporal scan statistics, another new technique, accurately detects snail-infested areas to determine targeted intervention and surveillance strategies [63].

Epidemiology and pathogenesis of snail-transmitted parasitic diseases

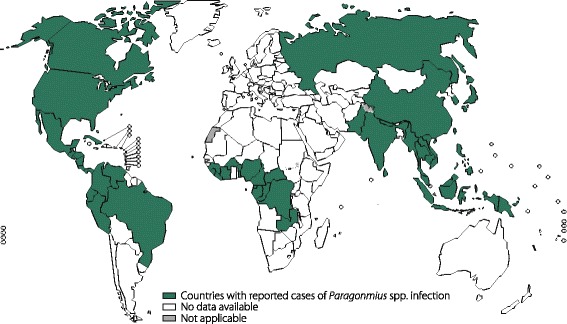

Paragonimiasis

Paragonimiasis, which is caused by members of the genus Paragonimus, is an inflammatory lung disease. Approximately 20 million people are infected with Paragonimus species (World Health Organization 2002) [64], and 293 million are at risk of infection [65]. The disease is primarily endemic to China, Korea, and Japan, as well as several other Asian countries [66]. P. westermani is the most common and widespread species of this genus and is widely distributed in Asia (Fig. 2). This parasite can infect human lungs, brain, spinal cord, and other organs, causing pulmonary, neurological, and abdominal diseases [66].

Fig. 2.

Global distribution of paragonimiasis

Fasciolopsiasis

Fasciolopsiasis, which results from F. buski infection, is highly prevalent in Asian countries and can be fatal in endemic areas [9] (Fig. 3). Generally, low-intensity F. buski infections cause mild symptoms, such as diarrhoea, abdominal pain, and headaches. However, high-intensity infections can cause death due to extensive intestinal erosion, ulceration, haemorrhaging, abscesses, and inflammation [67].

Fig. 3.

Global distribution of fasciolopsiasis

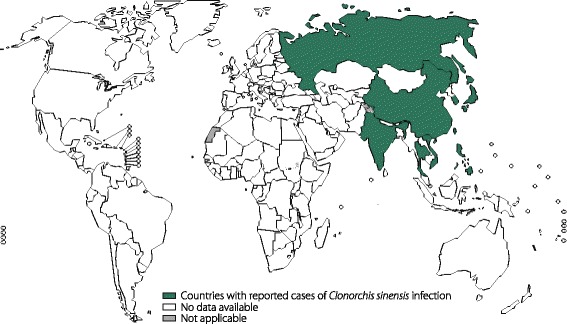

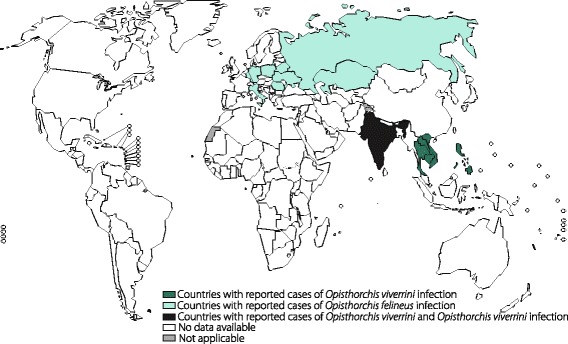

Clonorchiasis and opisthorchiasis

Pathogens that cause clonorchiasis and opisthorchiasis include the liver flukes C. sinensis, O. viverrini and O. felineus, members of the Opisthorchiidae family. Thirty-five million people are estimated to be infected with C. sinensis worldwide, approximately 15 million of whom are Chinese (Fig. 4). Approximately 10 million people are infected with O. viverrini, with 4 in 5 infections having occurred in Thailand and the remainder having occurred in Laos [68]. It is believed that 1.2 million people are infected with O. felineus, which is endemic to the area encompassing the former Soviet Union [67] (Fig. 5). C. sinensis has been classified by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) as a probable carcinogen (group 2A), while O. viverrini has been definitively validated as a carcinogen (class 1) [69]. Patients with mild C. sinensis infections are generally asymptomatic or have few clinical manifestations (such as diarrhoea and abdominal pain) [67], while severe infections can lead to acute pain in the right upper abdomen. Patients carrying O. viverrini are typically asymptomatic. Severe opisthorchiasis can lead to obstructive jaundice, cirrhosis, cholangitis, acalculous cholecystitis, or bile peritonitis [70]. Acute O. felineus infections produce fever and hepatitis-like symptoms, while chronic infections results in obstruction, inflammation and fibrosis of the biliary tract, liver abscesses, pancreatitis, and suppurative cholangitis [71].

Fig. 4.

Global distribution of clonorchiasis

Fig. 5.

Global distribution of opisthorchiasis

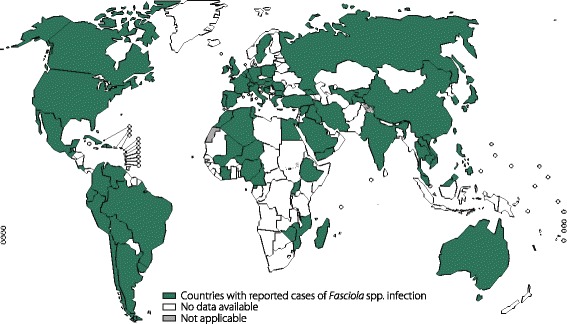

Fascioliasis

Fascioliasis is a disease caused by the liver trematode, F. hepatica, and is responsible for zoonotic diseases, especially livestock [72]. Fascioliasis has historically been endemic in Andean countries, the Caribbean, the Caspian region, northern Africa and western Europe [10]; however, it has recently spread globally, including to many countries in Africa, the Americas, Asia, Europe and Oceania [1] (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Global distribution of fascioliasis

Fascioliasis manifests as intrahepatic and ectopic fascioliasis, with intrahepatic fascioliasis including acute and chronic phases. In the acute phase, which is caused by the migration of the immature trematode to the liver, clinical manifestations include fever, vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhoea, urticaria, hepatomegaly and eosinophilia. During the chronic phase, when the flukes localize to the bile duct, the symptoms can present as intermittent biliary obstruction and inflammation [1, 67]. The migration of the parasites to other organs, such as the gastrointestinal tract, lungs, brain, muscles and eyes, results in ectopic fascioliasis without specific symptoms [73]. In recent years, fascioliasis has become a significant public health problem, causing extensive human morbidity (over 20 million cases reported worldwide) and considerable economic loss [43].

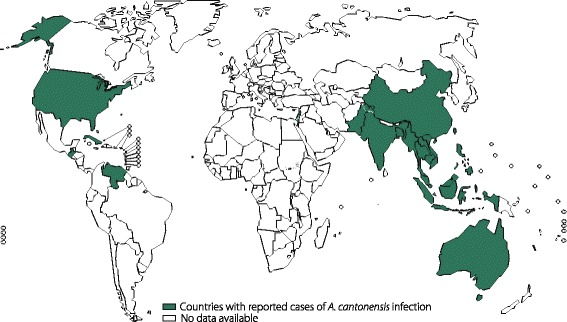

Angiostrongyliasis

Angiostrongyliasis is caused by the emerging pathogen, A. cantonensis, which was first discovered in 1935 in Canton, China, by Chen [3]. Now Angiostrongyliasis has spread from endemic areas in the Pacific Basin and Southeast Asia to countries in the Americas, including Brazil, the Caribbean Islands and the USA, and has been found in many areas worldwide [74] (Fig. 7). By 2008, more than 2800 cases had been documented in nearly 300 countries and regions [61], of which the major outbreaks were reported in endemic areas, particularly in China. For example, an extensive outbreak of 160 cases that occurred in 2006 in Beijing, China, attracted a great deal of public attention [75]. Additionally, sporadic cases have been reported in Europe, primarily from travellers returning from endemic regions [61].

Fig. 7.

Global distribution of angiostrongyliasis. The figure was drawn according to integrated information from previous studies. Countries with reported disease cases are coloured green, and countries with no available data are coloured white

The primary clinical manifestations of human angiostrongyliasis, which is one type of larva migrans [74], include eosinophilic meningitis (EM), meningoencephalitis and ocular angiostrongyliasis (OA), among which, EM is the most common presentation in humans when the larvae migrate to the brain. [2]. Major symptoms of angiostrongyliasis include vomiting, nausea, paraesthesia, headaches and neck stiffness [61]. Severe EM and meningoencephalitis are also reported to lead to neurologic dysfunction, coma and even death in some cases [76]. When the larvae migrate to the host’s eyes, which is rare, the disease manifests as OA, with symptoms including diplopia, strabismus and vision loss ranging from blurred vision to blindness [77].

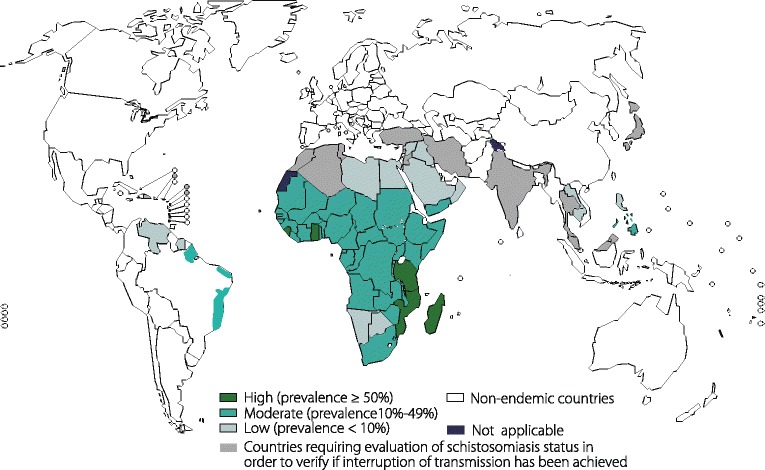

Schistosomiasis

Schistosomiasis, a neglected tropical disease, is an infection of blood flukes from the genus Schistosoma and has been reported in 78 countries in Africa, Asia and Latin America, especially in impoverished communities without access to a sound public health system [60, 78]. Schistosomiasis affects at least 230 million people worldwide, resulting in extensive social and economic burdens [4] (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Global distribution of schistosomiasis. Figures 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 8, were obtained from the World Health Organization (WHO) at http://www.who.int/neglected_diseases/NTD__A_statistical_update_latest_data_available.pdf and were authorized by the WHO to reproduce in this review

Schistosomiasis is an immune disease in which the body’s immune system overreacts to the eggs, cercariae, schistosomula and adult worms, leading to egg granulomas, cercarial dermatitis, vasculitis and endophlebitis, respectively [4].

Acute schistosomiasis occurs in individuals who are infected for the first time, presenting as fever, headache, abdominal pain, myalgia, malaise, fatigue and eosinophilia. Chronic schistosomiasis, which is common in endemic regions, manifests as non-specific intermittent rectal bleeding, abdominal pain and diarrhoea, heavily affecting people’s ability to study and work and can even lead to death [4].

In addition, S. haematobium is the only urogenital schistosomiasis pathogen whose typical symptom is haematuria [79]. Urogenital schistosomiasis may induce genital lesions, vaginal bleeding, pain during sexual intercourse, vulva nodules, and pathology of the prostate, seminal vesicles and other organs, with infertility being a potential long-term consequence [78].

In addition to the wide geographical distribution of SBPDs mentioned above, other SBPDs are distributed over a comparatively smaller scale. For example, echinostomiasis is primarily endemic in Southeast Asia, the Middle East and East Africa [80]. Halzoun, which is acquired by consuming raw freshwater fish containing Clinostomum metacercariae, has been reported in Japan, Korea, India and China [81].

Snail control

Intermediate hosts of various parasite species are essential in the transmission of SBPDs; Thus, the control of snail populations below a certain threshold is an efficient measure to limit the spread of SBPDs. Such control methods can be categorized into physical, chemical and biological measures.

Physical control measures aim at reducing snail populations through environmental management. For example, eliminating natural water bodies (such as marshes and ponds) and regulating human settlement in areas of risk are efficient measures. In some areas, proper drainage and environmental engineering have also decreased S. haematobium and S. japonicum transmission [82]. Another effective measure, mechanical disturbance, can potentially eliminate most snails by disturbing their epilithic habitats using boat-mounted rototillers or tractors and rakes. In addition, the removal of bird roosting sites, implementation of mechanized farming and the rotation of aquatic and xeromorphic crops can also reduce snail populations [83].

Chemical control generally involves the use of either synthetic or natural chemical molluscicides, and the application of chemical molluscicides remains one of the most efficient methods of snail control [84]. Copper sulfate, sodium pentachlorophenate (NaPCP), N-tritylmorpholine, and niclosamide (Bayluscide) were widely used from the 1950s to 1970s to control snails, especially to control schistosomiasis in Asia, Africa and South America [85]. In China, over 2000 chemicals have been developed and used since the 1950s, such as NaPCP, nicotinanilide, and bromoacetamide [84]. Among these synthetic molluscicides, only niclosamide is recommended by the World Health Organization; therefore, a 50% wettable powder of niclosamide ethanolamine salt (WPN) is the only synthetic compound available in China, where it has been widely used in snail control [84]. Remarkably, no clear evidence has emerged regarding snail resistance after extensive and prolonged niclosamide application for over 20 years [86] despite WPN being both toxic to fish and costly [84]. To address these problems, a novel molluscicide, quinoid-2′, 5-dichloro-4′-nitrosalicylanilide salt, has been developed that has the same molluscicidal effects as WPN but is cheaper and is significantly less toxic to fish [84]. Another new molluscicide, a niclosamide suspension concentrate, is physically more stable, more effective, and less toxic than WPN [87]. These molluscicides can be more useful than other snail control methods in areas endemic for schistosomiasis [84, 87].

Due to the high cost, toxicity, environmental contamination, and possible development of snail resistance to chemical molluscicides [88], natural molluscicides are rapidly being developed. Many plant extracts are potential molluscicides that are environmentally friendly, less toxic and are less likely to cause snails to develop resistance [89]. Many plant products have shown to be effective. For example, solvent extracts of fresh, mature Solanum nigrum leaves and species of the genus Atriplex repel Biomphalaria alexandrina [89, 90], while Atriplex inflata has been reported to repel Galba truncatula [90]. Some plant extracts, such as those from Tetrapleura tetraptera and Piper species [89] display significant activity against Biomphalaria glabrata. Similarly, aqueous and ethyl acetate crude extracts of Glinus lotoides fruit [91] and methanolic extracts from fresh Solanum aculeastrum root bark and berries [92] show molluscicidal activity against Biomphalaria pfeifferi. Crude camellia and mangosteen extracts are effective molluscicides for controlling Bithynia siamensis goniomphalos [93]. Punica granatum and Canna indica may have potent effects against Lymnaea acuminata, and the concentrations used to kill snails are non-toxic to fish [94]. Linalool, derived from Cinnamomum camphora, shows molluscicidal activity against O. hupensis and may work by damaging the gills and hepatopancreas [88]. Products from Hypericum species hexane extracts may be used as potential molluscicides to control Radix peregra snails [95].

Biological control is another method used to reduce snail populations and influence the transmission of SBPDs. In Senegal, field trials have demonstrated that water stocked with predatory prawns (Macrobrachium vollenhoveni) led to fewer infected snails and reduced schistosomiasis transmission in villages [96]. A laboratory experiment showed that predatory prawns prefer to consume snails infected with schistosomes, and young and growing prawns kill snails most efficiently [97]. The water bug, Sphaerodema urinator, shares a common habitat with freshwater snails and has been used to control host snails that transmit schistosomiasis. One study indicated that S. urinator may be an effective biological agent as a predator of the intermediate hosts of Schistosoma in water [98]. The black carp, Mylopharyngodon piceus, is a noteworthy predator of snails that are intermediate hosts of C. sinensis and O. viverrini. Investigations showed that black carp can decrease snail population densities under both semi-field and field conditions and have been used successfully as biological controls in different regions of the world [99]. Although the potential of biologically controlling freshwater snails has received recent attention, it may negatively impact human health. However, when biological control is successful, it is mutually beneficial to both humans and nature [96].

Conclusions

SBPDs, including most trematodiasis diseases (clonorchiasis, fascioliasis, fasciolopsiasis, opisthorchiasis, paragonimiasis and schistosomiasis) and some nematodiasis diseases (e.g., angiostrongyliasis) with an expanding geographical distribution, remain highly prevalent worldwide and have substantial deleterious impacts on human health, predominantly in tropical and sub-tropical areas. Consequently, breaking the disease transmission cycle by controlling host snail populations is an alternative method of reducing the spread of such diseases due to the lack of clinically effective SBPD vaccines and potential parasite resistance to the currently available anthelmintic drugs.

Compared with physical and synthesized chemical molluscicide control methods, plant-derived molluscicides are more environmentally friendly, less toxic and are less likely to cause snails to develop resistance, suggesting a promising novel method of reducing endemic snail populations. In addition, comprehensive molecular epidemiology studies, an understanding of the ecology of medically important snails and further insights into snail-parasite interactions, particularly those based on large-scale data mining of genomic snail datasets, are necessary to identify specific or key molecules involved in snail survival, metabolism and development. These molecules could be potential targets for natural molluscicides, which could be developed as novel and effective treatment and control strategies against SBPDs.

Additional file

Multilingual abstracts in the five official working languages of the United Nations. (PDF 352 kb)

Acknowledgements

We sincerely appreciate the World Health Organization authorizing our request to reproduce Figures 3, 5, 6, 7 and 8 in this review.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Key Research and Development Program of China (grant no. 2016YFC1202003, 2016YFC1202005 and 2016YFC1200500), the Project of Basic Platform of National Science and Technology Resources of the Ministry of Sciences and Technology of China (grant no. TDRC-2017-22), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81371836, 81572023 and 81271855), Guangdong Natural Science Foundation (grant no. 2014A030313134), the Science and Technology Planning Project of Guangdong Province (grant no. 2016A050502008), the Science and Technology Planning Project of Guangzhou (grant no. 201607010029), the 111 Project (grant no. B12003), the Undergraduates Innovation Training Program of Guangdong Province (grant nos. 201410558274 and 201601084) and the Teaching Reform Project of Sun Yat-sen University (grant no. 2016012).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- Ac

Angiostrongylus cantonensis

- Cs

Clonorchis sinensis

- EM

Eosinophilic meningitis

- Fb

Fasciolopsis buski

- Fh

Fasciola hepatica

- L1

First-stage larvae

- L2

Second-stage larvae

- L3

Third-stage larvae

- NaPCP

Sodium pentachlorophenate

- OA

Ocular angiostrongyliasis

- Of

Opisthorchis felineus

- Ov

Opisthorchis viverrini

- Pw

Paragonimus westermani

- SBPDs

Snail-borne parasitic diseases

- Sh

Schistosoma haematobium

- Si

Schistosoma intercalatum

- Sj

Schistosoma japonicum

- Smal

Schistosoma malayensis

- Sman

Schistosoma mansoni

- Smek

Schistosoma mekongi

- WPN

niclosamide ethanolamine salt

Authors’ contributions

LXT, GQY, YL and SLG performed the literature search and drafted the first version of the manuscript. KO and LZY designed, coordinated and revised the review. All author read the manuscript and agree to submit and publish in Infectious Diseases of Poverty.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s40249-018-0414-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Xiao-Ting Lu, Email: luxt3@mail2.sysu.edu.cn.

Qiu-Yun Gu, Email: guqy3@mail2.sysu.edu.cn.

Yanin Limpanont, Email: yanin.lim@mahidol.ac.th.

Lan-Gui Song, Email: 308916762@qq.com.

Zhong-Dao Wu, Email: 1151917403@qq.com.

Kamolnetr Okanurak, Email: kamolnetr.oka@mahidol.ac.th.

Zhi-Yue Lv, Email: lvzhiyue@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Sripa B, Kaewkes S, Intapan PM, Maleewong W, Brindley PJ. Food-borne trematodiases in Southeast Asia. Adv Parasitol. 2010;72:305–350. doi: 10.1016/S0065-308X(10)72011-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cowie RH. Biology, systematics, life cycle, and distribution of Angiostrongylus cantonensis, the cause of rat lungworm disease. Hawaii J Med Public Health. 2013;72:6–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thiengo SC, Simões Rde O, Fernandez MA, Maldonado A., Jr Angiostrongylus cantonensis and rat lungworm disease in Brazil. Hawaii J Med Public Health. 2013;72:18–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Colley DG, Bustinduy AL, Secor WE, King CH. Human schistosomiasis. Lancet. 2014;383:2253–2264. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61949-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zheng S, Zhu Y, Zhao Z, Wu Z, Okanurak K, Lv Z. Liver fluke infection and cholangiocarcinoma: a review. Parasitol Res. 2017;116:11–19. doi: 10.1007/s00436-016-5276-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu Q, Wei F, Liu W, Yang S, Zhang X. Paragonimiasis: an important food-borne zoonosis in China. Trends Parasitol. 2008;24:318–323. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2008.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moazeni M, Ahmadi A. Controversial aspects of the life cycle of Fasciola hepatica. Exp Parasitol. 2016;169:81–89. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2016.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singh UC, Kumar A, Srivastava A, Patel B, Shukla VK, Gupta SK. Small bowel stricture and perforation: an unusual presentation of Fasciolopsis buski. Trop Gastroenterol. 2011;32:320–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aksoy DY, Kerimoglu U, Oto A, Erguven S, Arslan S, Unal S, et al. Infection with Fasciola hepatica. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2005;11:859–861. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2005.01254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mas-Coma S, Bargues MD, Valero MA. Fascioliasis and other plant-borne trematode zoonoses. Int J Parasitol. 2005;35:1255–1278. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2005.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guo YH, Lv S, Gu WB, Liu HX, Wu Y, Zhang Y. Species composition and distribution of medical mollusca in Shanghai City. Chin J Schisto Control. 2015;27:36–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guo YH, Wang CM, Luo J, He HX. Intermediate host of main parasites: molluscs distributed in Beijing region. Chin J Vector Bio Control. 2009; 20:449–453. (in Chinese).

- 13.Kiatsopit N, Sithithaworn P, Saijuntha W, Boonmars T, Tesana S, Sithithaworn J, et al. Exceptionally high prevalence of infection of Bithynia siamensis goniomphalos with Opisthorchis viverrini cercariae in different wetlands in Thailand and Lao PDR. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2012;86:464–469. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2012.11-0217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hering-Hagenbeck S, Schuster RA. Focus of opisthorchiidosis in Germany. Appl Parasitol. 1996;37:260–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miyamoto K, Kirinoki M, Matsuda H, Hayashi N, Chigusa Y, Sinuon M, et al. Field survey focused on Opisthorchis viverrini infection in five provinces of Cambodia. Parasitol Int. 2014;63:366–373. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2013.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Serbina EA. The effect of trematode parthenites on the individual fecundity of Bithynia troscheli (Prosobranchia: Bithyniidae) Acta Parasitol. 2014;60:40–49. doi: 10.1515/ap-2015-0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhao WH, Wang HJ, Wang HZ, Liu XQ. Conversion methods of freshwater snail tissue dry mass and ash free dry mass. Chin J Appl Ecolo. 2009;20:1452–1458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li LH, Zhou YB, Zheng SB, Wu JY, Song XX, He Z, et al. Distribution of univalvia molluscs in area with natural decline of Oncomelania hupensis snails in eastern Dongting Lake area. Chin J Schisto Control. 2014;26:22–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lu YX, Yang LD, Hu M, Gui AF, Zuo SL. Parafossarulus anomalospiralis: first intermediate host of Clonorchis sinensis:a first report in Hubei Province. China Chin J Parasitol Parasit Dis. 1994;12:290. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Choi DW. Clonorchis sinensis: life cycle, intermediate hosts, transmission to man and geographical distribution in Korea. Arzneimittelforschung. 1984;34:1145–1151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhou WC, She SS, Chen DN, Lin J, Guo YH, Chen SL. Description on the intermediate hosts of Angiostrongylus cantonensis. Chin J Zoonoses. 2007;23:401–408. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sri-Aroon P, Chusongsang P, Chusongsang Y, Pornpimol S, Butraporn P, Lohachit C. Snails and Trematode infection after Indian Ocean tsunami in Phang-Nga Province, southern Thailand. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2010;41:48–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tesana S, Srisawangwong T, Sithithaworn P, Laha T, Andrews R. Prevalence and Intensity of infection with third stage larvae of Angiostrongylus cantonensis in mollusks from Northeast Thailand. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009;80:983–987. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCreesh N, Booth M. The effect of simulating different intermediate host snail species on the link between water temperature and schistosomiasis risk. PLoS One. 2014;9:e87892. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mostafa OM, Bin Dajem SM, Al-Qahtani A, Ibrahim EH, Al-Quraishy SA. Developing species-specific primers to identify Bulinus truncatus and Bulinus beccari, the intermediate hosts of Schistosoma haematobium in Saudi Arabia. Gene. 2012;499:256–261. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2012.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Greer GJ, Mimpfoundi R, Malek EA, Joky A, Ngonseu E, Ratard RC. Human schistosomiasis in Cameroon. II Distribution of the snail hosts Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1990;42:573–580. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1990.42.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stensgaard AS, Utzinger J, Vounatsou P, Hürlimann E, Schur N, Saarnak CF, et al. Large-scale determinants of intestinal schistosomiasis and intermediate host snail distribution across Africa: does climate matter? Acta Trop. 2013;128:378–390. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2011.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vidigal TH, Caldeira RL, Simpson AJ, Carvalho OS. Identification of Biomphalaria havanensis and Biomphalaria obstructa populations from Cuba using polymerase chain reaction and restriction fragment length polymorphism of the ribosomal RNA intergenic spacer. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2001;96:661–665. doi: 10.1590/S0074-02762001000500013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Attwood SW, Huo GN, Qiu JW. Update on the distribution and phylogenetics of Biomphalaria (Gastropoda: Planorbidae) populations in Guangdong Province, China. Acta Trop. 2015;141:258–270. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2014.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moser W, Greter H, Schindler C, Allan F, Ngandolo BN, Moto DD, et al. The spatial and seasonal distribution of Bulinus truncatus, Bulinus forskalii and Biomphalaria pfeifferi, the intermediate host snails of schistosomiasis, in N’Djamena, Chad. Geospat Health. 2014;9:109–118. doi: 10.4081/gh.2014.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McCreesh N, Arinaitwe M, Arineitwe W, Tukahebwa EM, Booth M. Effect of water temperature and population density on the population dynamics of Schistosoma mansoni intermediate host snails. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:503. doi: 10.1186/s13071-014-0503-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kariuki HC, Clennon JA, Brady MS, Kitron U, Sturrock RF, Ouma JH, Ndzovu ST, et al. Distribution patterns and cercarial shedding of Bulinus nasutus and other snails in the Msambweni area, Coast Province, Kenya. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2004;70:449–456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stothard JR, Brémond P, Andriamaro L, Sellin B, Sellin E, Rollinson D. Bulinus species on Madagascar: molecular evolution, genetic markers and compatibility with Schistosoma haematobium. Parasitology. 2001;123:S261–S275. doi: 10.1017/S003118200100806X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zein-Eddine R, Djuikwo-Teukeng FF, Al-Jawhari M, Senghor B, Huyse T, Dreyfuss G. Phylogeny of seven Bulinus species originating from endemic areas in three African countries, in relation to the human blood fluke Schistosoma haematobium. BMC Evol Biol. 2014;14:271. doi: 10.1186/s12862-014-0271-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arfaa F, Massoud J, Chu KY. Susceptibility of Portuguese Bulinus contortus to Iranian strains of Schistosoma haematobium and S. bovis. Bull World Health Organ. 1967;37:165–166. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Frandsen F. Host-parasite relationship of Bulinus forskalii (Ehrenberg) and Schistosoma intercalatum fisher 1934, from Cameroun. J Helminthol. 1975;49:73–84. doi: 10.1017/S0022149X00023178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rollinson D, Stothard JR, Southgate VR. Interactions between intermediate snail hosts of the genus Bulinus and schistosomes of the Schistosoma haematobium group. Parasitology. 2001;123:S245–S260. doi: 10.1017/s0031182001008046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Betterton C, Ndifon GT, Tan RM. Schistosomiasis in Kano State, Nigeria. II Field studies on aestivation in Bulinus rohlfsi (Clessin) and B globosus (Morelet) and their susceptibility to local strains of Schistosoma haematobium (Bilharz) Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1988;82:571–579. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1988.11812293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Madsen H, Bloch P, Phiri H, Kristensen TK, Furu P. Bulinus nyassanus is an intermediate host for Schistosoma haematobium in Lake Malawi. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2001;95:353–360. doi: 10.1080/00034983.2001.11813648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jauhari RK, Nongthombam PD. Occurrence of a snail borne disease, cercarial dermatitis (swimmer itch) in Doon Valley (Uttarakhand), India. Iran J Public Health. 2014;43:162–167. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chung PR, Jung Y, Park YK. Segmentina hemisphaerula: a new molluscan intermediate host for Echinostoma cinetorchis in Korea. J Parasitol. 2001;87:1169–1171. doi: 10.1645/0022-3395(2001)087[1169:SHANMI]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gilman RH, Mondal G, Maksud M, Alam K, Rutherford E, Gilman JB, et al. Endemic focus of Fasciolopsis buski infection in Bangladesh. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1982;31:796–802. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1982.31.796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Correa AC, Escobar JS, Noya O, Velásquez LE, González-Ramírez C, Hurtrez-Boussès S, et al. Morphological and molecular characterization of Neotropic Lymnaeidae (Gastropoda: Lymnaeoidea), vectors of fasciolosis. Infect Genet Evol. 2011;11:1978–1988. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2011.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu GH, Wang SY, Huang WY, Zhao GH, Wei SJ, Song HQ, et al. The complete mitochondrial genome of Galba pervia (Gastropoda: Mollusca), an intermediate host snail of Fasciola spp. PLoS One. 2012;7:e42172. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bargues MD, Vigo M, Horak P, Dvorak J, Patzner RA, Pointier JP, et al. European Lymnaeidae (Mollusca: Gastropoda), intermediate hosts of trematodiases, based on nuclear ribosomal DNA ITS-2 sequences. Infect Genet Evol. 2001;1:85–107. doi: 10.1016/S1567-1348(01)00019-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cruz-Mendoza I, Quiroz-Romero H, Correa D, Gómez-Espinoza G. Transmission dynamics of Fasciola hepatica in the plateau region of Mexico. Effect of weather and treatment of mammals under current farm management. Vet Parasitol. 2011;175:73–79. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2010.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cipriani P, Mattiucci S, Paoletti M, Scialanca F, Nascetti G. Molecular evidence of Trichobilharzia franki Müller and Kimmig, 1994 (Digenea: Schistosomatidae) in Radix auricularia from Central Italy. Parasitol Res. 2011;109:935–940. doi: 10.1007/s00436-011-2295-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Novobilský A, Kašný M, Beran L, Rondelaud D, Höglund J. Lymnaea palustris and Lymnaea fuscus are potential but uncommon intermediate hosts of Fasciola hepatica in Sweden. Parasit Vectors. 2013;6:251. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-6-251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kim HY, Choi IW, Kim YR, Quan JH, Ismail HA, Cha GH, et al. Fasciola hepatica in snails collected from water-dropwort fields using PCR. Korean J Parasitol. 2014;52:645–652. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2014.52.6.645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Baldock FC, Arthur RJ. A survey of fascioliasis in beef cattle killed at abattoirs in southern Queensland. Aust Vet J. 1985;62:324–326. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-0813.1985.tb07650.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cañete R, Yong M, Sánchez J, Wong L, Gutiérrez A. Population dynamics of intermediate snail hosts of Fasciola hepatica and some environmental factors in San Juan y Martinez municipality, Cuba. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2004;99:257–262. doi: 10.1590/S0074-02762004000300003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Soldánová M, Selbach C, Sures B, Kostadinova A, Pérez-Del-Olmo A. Larval trematode communities in Radix auricularia and Lymnaea stagnalis in a reservoir system of the Ruhr River. Parasit Vectors. 2010;3:56. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-3-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Huňová K, Kašný M, Hampl V, Leontovyč R, Kuběna A, Mikeš L, et al. Radix spp.: identification of trematode intermediate hosts in the Czech Republic. Acta Parasitol. 2012;57:273–284. doi: 10.2478/s11686-012-0040-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dar YD, El-Husseny IM. Experimental infection of Radix natalensis and Culiseta longiareolata larvae with Plagiorchiid xiphidiocercariae in Egypt. J Egypt Soc Parasitol. 2013;43:679–687. doi: 10.12816/0006424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kaset C, Eursitthichai V, Vichasri-Grams S, Viyanant V, Grams R. Rapid identification of lymnaeid snails and their infection with Fasciola gigantica in Thailand. Exp Parasitol. 2010;126:482–488. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2010.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Radev V, Kanev I, Gold D. Life cycle and identification of an eyefluke from Israel transmitted by Melanoides tuberculata (Muller, 1774) J Parasitol. 2000;86:773–776. doi: 10.1645/0022-3395(2000)086[0773:LCAIOA]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yousif F, Ayoub M, Tadros M, El Bardicy S. The first record of Centrocestus formosanus (Nishigori, 1924) (Digenea: Heterophyidae) in Egypt. Exp Parasitol. 2016;168:56–61. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2016.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Miranda NA, Perissinotto R. Stable isotope evidence for dietary overlap between alien and native gastropods in Coastal Lakes of northern KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. PLoS One. 2012;7:e31897. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Limpanont Y, Chusongsang P, Chusongsang Y, Limsomboon J, Sanpool O, Kaewkong W, et al. A new population and habitat for Neotricula aperta in the Mekong River of northeastern Thailand: a DNA sequence-based phylogenetic assessment confirms identifications and interpopulation relationships. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2015;92:336–339. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.14-0467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cheng G, Li D, Zhuang D, Wang Y. The influence of natural factors on the spatio-temporal distribution of Oncomelania hupensis. Acta Trop. 2016;164:194–207. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2016.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang QP, Wu ZD, Wei J, Owen RL, Lun ZR. Human Angiostrongylus cantonensis: an update. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012;31:389–395. doi: 10.1007/s10096-011-1328-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Simoonga C, Utzinger J, Brooker S, Vounatsou P, Appleton CC, Stensgaard AS, et al. Remote sensing, geographical information system and spatial analysis for schistosomiasis epidemiology and ecology in Africa. Parasitology. 2009;136:1683–1693. doi: 10.1017/S0031182009006222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gao FH, Abe EM, Li SZ, Zhang LJ, He JC, Zhang SQ, et al. Fine scale spatial-temporal cluster analysis for the infection risk of Schistosomiasis japonica using space-time scan statistics. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:578. doi: 10.1186/s13071-014-0578-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kim TI, Oh SR, Dai F, Yang HJ, Ha SD, Hong SJ. Inactivation of Paragonimus westermani metacercariae in soy sauce-marinated and frozen freshwater crabs. Parasitol Res. 2017;116:1003–1006. doi: 10.1007/s00436-017-5380-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Keiser J, Utzinger J. Food-borne trematodiasis: current chemotherapy and advances with artemisinins and synthetic trioxolanes. Trends Parasitol. 2007;23:555–562. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2007.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chen MX, Ai L, Zhang RL, Xia JJ, Wang K, Chen SH, et al. Sensitive and rapid detection of Paragonimus westermani infection in humans and animals by loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) Parasitol Res. 2011;108:1193–1198. doi: 10.1007/s00436-010-2162-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Keiser J, Utzinger J. Food-borne trematodiases. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2009;22:466–483. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00012-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Andrews RH, Sithithaworn P, Petney TN. Opisthorchis viverrini: an underestimated parasite in world health. Trends Parasitol. 2008;24:497–501. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2008.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Toledo R, Esteban JG, Fried B. Current status of food-borne trematode infections. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012;31:1705–1718. doi: 10.1007/s10096-011-1515-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Keiser J, Utzinger J. Emerging foodborne trematodiasis. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:1507–1514. doi: 10.3201/eid1110.050614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sripa B, Pairojkul C. Cholangiocarcinoma: lessons from Thailand. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2008;24:349–356. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e3282fbf9b3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jabbour-Zahab R, Pointier JP, Jourdane J, Jarne P, Oviedo JA, Bargues MD, et al. Phylogeography and genetic divergence of some lymnaeid snails, intermediate hosts of human and animal fascioliasis with special reference to lymnaeids from the Bolivian Altiplano. Acta Trop. 1997;64:191–203. doi: 10.1016/S0001-706X(96)00631-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ashrafi K, Bargues MD, O'Neill S, Mas-Coma S. Fascioliasis: a worldwide parasitic disease of importance in travel medicine. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2014;12:636–649. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2014.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Song L, Wang X, Yang Z, Lv Z, Wu Z. Angiostrongylus cantonensis in the vector snails Pomacea canaliculata and Achatina fulica in China: a meta-analysis. Parasitol Res. 2016;115:913–923. doi: 10.1007/s00436-015-4849-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.He ZY, Jia L, Huang F, Liu GR, Li J, Dou XF, et al. Investigation on outbreak of angiostrongyliasis cantonensis in Beijing. Chin J Public Health. 2007;23:1241–1242. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kim JR, Hayes KA, Yeung NW, Cowie RH. Diverse gastropod hosts of Angiostrongylus cantonensis, the rat lungworm, globally and with a focus on the Hawaiian islands. PLoS One. 2014;9:e94969. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Martins YC, Tanowitz HB, Kazacos KR. Central nervous system manifestations of Angiostrongylus cantonensis infection. Acta Trop. 2015;141:46–53. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2014.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.World Health Organization: Schistosomiasis. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs115/en/. Accessed Oct 2017.

- 79.World Health Organization: Schistosomiasis frequently asked questions about worms. http://www.who.int/schistosomiasis/resources/faqs/en/. Accessed 25 Sep 2016.

- 80.Chunge RN, Chunge CN. Infection with Echinostoma sp. in a group of travellers to Lake Tanganyika, Tanzania, in January 2017. J Travel Med. 2017;24:tax036. doi: 10.1093/jtm/tax036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wang M-L, Chen H-Y, Shih H-H. Occurrence and distribution of yellow grub trematodes (Clinostomum complanatum) infection in Taiwan. Parasitol Res. 2017;116:1761–1771. doi: 10.1007/s00436-017-5457-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Li ZJ, Ge J, Dai JR, Wen LY, Lin DD, Madsen H, et al. Biology and control of snail intermediate host of Schistosoma japonicum in the People's Republic of China. Adv Parasitol. 2016;92:197–236. doi: 10.1016/bs.apar.2016.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Leighton BJ, Zervos S, Webster JM. Ecological factors in schistosome transmission, and an environmentally benign method for controlling snails in a recreational lake with a record of schistosome dermatitis. Parasitol Int. 2000;49:9–17. doi: 10.1016/S1383-5769(99)00034-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Xia J, Yuan Y, Xu X, Wei F, Li G, Liu M, et al. Evaluating the effect of a novel molluscicide in the endemic schistosomiasis japonica area of China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11:10406–10418. doi: 10.3390/ijerph111010406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.King CH, Sutherland LJ, Bertsch D. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of chemical-based mollusciciding for control of Schistosoma mansoni and S. haematobium transmission. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:e0004290. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Dai J, Li Y, Wang W, Xing Y, Qu G, Liang Y. Sensitivity of Oncomelania hupensis to niclosamide: a nation-wide survey in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11:3086–3095. doi: 10.3390/ijerph110303086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Dai JR, Wang W, Liang YS, Li HJ, Guan XH, Zhu YC. A novel molluscicidal formulation of niclosamide. Parasitol Res. 2008;103:405–412. doi: 10.1007/s00436-008-0988-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Yang F, Long E, Wen J, Cao L, Zhu C, Hu H, et al. Linalool, derived from Cinnamomum camphora (L.) Presl leaf extracts, possesses molluscicidal activity against Oncomelania hupensis and inhibits infection of Schistosoma japonicum. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:407. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-7-407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Rawani A, Ghosh A, Chandra G. Laboratory evaluation of molluscicidal & mosquito larvicidal activities of leaves of Solanum nigrum L. Indian J Med Res. 2014;140:285–295. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hamed N, Njeh F, Damak M, Ayadi A, Mezghani-Jarraya R, Hammami H. Molluscicidal and larvicidal activities of Atriplex inflata aerial parts against the mollusk Galba truncatula, intermediate host of Fasciola hepatica. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2015;57:473–479. doi: 10.1590/S0036-46652015000600003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kiros G, Erko B, M G, Mekonnen Y. Laboratory assessment of molluscicidal and cercariacidal effects of Glinus lotoides fruits. BMC Res Notes. 2014;7:220. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-7-220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Wanyonyi AW, Chhabra SC, Mkoji G, Njue W, Tarus PK. Molluscicidal and antimicrobial activity of Solanum aculeastrum. Fitoterapia. 2003;74:298–301. doi: 10.1016/S0367-326X(03)00030-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Aukkanimart R, Boonmars T, Pinlaor S, Tesana S, Aunpromma S, Booyarat C, et al. Histopathological changes in tissues of Bithynia siamensis goniomphalos incubated in crude Eextracts of Camellia seed and Mangosteen pericarp. Korean J Parasitol. 2013;51:537–544. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2013.51.5.537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Tripathi SM, Singh DK. Molluscicidal activity of Punica granatum bark and Canna indica root. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2000;33:1351–1355. doi: 10.1590/S0100-879X2000001100014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Teixeira T, Rainha N, Rosa JS, Lima E, Baptista J. Molluscicidal activity of crude water and hexane extracts of Hypericum species to snails (Radix peregra) Environ Toxicol Chem. 2012;31:748–753. doi: 10.1002/etc.1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Sokolow SH, Huttinger E, Jouanard N, Hsieh MH, Lafferty KD, Kuris AM, et al. Reduced transmission of human schistosomiasis after restoration of a native river prawn that preys on the snail intermediate host. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:9650–9655. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1502651112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Sokolow SH, Lafferty KD, Kuris AM. Regulation of laboratory populations of snails (Biomphalaria and Bulinus spp.) by river prawns, Macrobrachium spp. (Decapoda, Palaemonidae): implications for control of schistosomiasis. Acta Trop. 2014;132:64–74. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2013.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Younes A, El-Sherief H, Gawish F, Mahmoud M. Biological control of snail hosts transmitting schistosomiasis by the water bug, Sphaerodema urinator. Parasitol Res. 2017;116:1257–1264. doi: 10.1007/s00436-017-5402-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hung NM, Duc NV, Stauffer JR, Madsen H. Use of black carp (Mylopharyngodon piceus) in biological control of intermediate host snails of fish-borne zoonotic trematodes in nursery ponds in the Red River Delta, Vietnam. Parasit Vectors. 2013;6:142. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-6-142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Devi NP, Jauhari RK. Diversity and cercarial shedding of malaco fauna collected from water bodies of Ratnagiri district, Maharashtra. Acta Trop. 2008;105:249–252. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Carvalho Odos S, Scholte RG, Mendonça CL, Passos LK, Caldeira RL. Angiostrongylus cantonensis (nematode: Metastrongyloidea) in molluscs from harbour areas in Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2012;107(6):740. doi: 10.1590/S0074-02762012000600006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Invasive species compendium: Clea helena (assassin snail). http://www.cabi.org/isc/datasheet/108187#20163318989. Updated 22 June 2017.

- 103.Hollingsworth RG, Howe K, Jarvi SI. Control measures for slug and snail hosts of Angiostrongylus cantonensis, with special reference to the semi-slug Parmarion martensi. Hawaii J Med Public Health. 2013;72:75–80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Medeiros C, Scholte RG, D'ávila S, Caldeira RL, Carvalho Odos S. Spatial distribution of Lymnaeidae (Mollusca, Basommatophora), intermediate host of Fasciola hepatica Linnaeus, 1758 (Trematoda, Digenea) in Brazil. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2014;56:235–252. doi: 10.1590/S0036-46652014000300010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Dreyfuss G, Correa AC, Djuikwo-Teukeng FF, Novobilský A, Höglund J, Pankrác J, et al. Differences in the compatibility of infection between the liver flukes Fascioloides magna and Fasciola hepatica in a Colombian population of the snail Galba sp. J Helminthol. 2015;89:720–726. doi: 10.1017/S0022149X14000509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Paraense WL. Planorbidae, Lymnaeidae and Physidae of Peru (Mollusca: Basommatophora) Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2003;98:767–771. doi: 10.1590/S0074-02762003000600010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Campbell SJ, Stothard JR, O'Halloran F, Sankey D, Durant T, Ombede DE, et al. Urogenital schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminthiasis (STH) in Cameroon: an epidemiological update at Barombi Mbo and Barombi Kotto crater lakes assessing prospects for intensified control interventions. Infect Dis Poverty. 2017;6:49. doi: 10.1186/s40249-017-0264-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Liu YY, Zhang WZ, Wang YX. First intermediate hosts of lung fluke in China. Chin J Zoolog. 1984;2:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Cheng YZ, Li LS, Lin GH, Zhou PC, Jiang DW, Fang YY, et al. Survey on the foci of Paragonimus in Youxi, Yongtai and Pinghe counties of Fujian Province. Chin J Parasitol Parasit Dis. 2010;28:406–410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Yuan HC, Upatham ES, Kruatrachue M, Khunborivan V. Susceptibility of snail vectors to oriental anthropophilic Schistosoma. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1984;15:86–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Oliveira AP, Gentile R, Maldonado Júnior A, Lopes Torres EJ, Thiengo SC. Angiostrongylus cantonensis infection in molluscs in the municipality of São Gonçalo, a metropolitan area of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: role of the invasive species Achatina fulica in parasite transmission dynamics. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2015;110:739–744. doi: 10.1590/0074-02760150106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Bakke TA. Taxonomy of Leucochloridium sp. (Digenea) infecting Succinea pfeifferi Rossmässler, 1835. Z Parasitenkd. 1978;55:153–164. doi: 10.1007/BF00384830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Gu Q, Zhang M, Zhou C, Zhu G, Dong J, Gao Y, et al. Analysis of genetic diversity and population structure of Bellamya quadrata from lakes of middle and lower Yangtze River. Genetica. 2015;143:545–554. doi: 10.1007/s10709-015-9852-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Hirai N, Tatarazako N, Koshio M, Kawabe K, Shiraishi F, Hayakawa Y, et al. Seasonal changes in sex ratio, maturation, and size composition of fresh water snail, Sinotaia quadrata histrica, in Lake Kasumigaura. Environ Sci. 2004;11:243–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Multilingual abstracts in the five official working languages of the United Nations. (PDF 352 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.