Congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract (CAKUT) are the most common cause of pediatric chronic kidney disease in Western countries. 1,2 They represent a spectrum of malformations, including renal dysplasia, duplex kidney, hydronephrosis, vesicoureteric reflux, obstructive uropathies such as posterior urethral valve and pelviureteric and ureterovesical junction obstruction, and non-obstructive megaureter, among others.2–8 The CAKUT spectrum of malformations may be isolated, syndromic with associated extrarenal malformations, or part of other syndromes such as maturity onset diabetes of the young (MODY) and DiGeorge syndrome.2 The precise cause of CAKUT is unknown; however, these abnormalities are known to result from missteps during critical stages of kidney development, such as ureteric budding, mesenchymal to epithelial transition, branching morphogenesis, and nephron patterning and elongation.2–8 Genomic studies have played a significant role in understanding the pathogenesis of CAKUT and kidney development. Unfortunately, identification of single-gene causes of CAKUT using the classic genetic approach of linkage analysis followed by direct sequencing has been very challenging because of phenotype heterogeneity,9 and investigators working in this area have been trying to develop efficient ways to unravel the genetic basis of CAKUT. One innovative multistep approach was recently reported by a group of investigators in the United States and Europe.10

WHAT DOES THIS IMPORTANT STUDY SHOW?

This recent study, by multiple groups in the United States and Europe led by a team at Columbia University, New York, and published in the New England Journal of Medicine, used a unique approach to map the gene responsible for the renal defects in the 22q11.2 microdeletion that has been recognized for years to be the cause of DiGeorge syndrome.10 This is the most common microdeletion syndrome in humans,11 and patients classically present with malformations in multiple organs, including facial anomalies, cardiac defects, neurologic malformations and learning disability, thymic hypoplasia resulting in T-cell deficiency, hypoparathyroidism, and CAKUT, among others.11–13 The prevalence of CAKUT in 22q11.2 microdeletion is ~30%.13 Apart from the association between haploinsufficiency in the transcription factor gene TBX1 and cardiac malformations in 22q11.2 microdeletion, the genetic basis for other phenotypic expression of the microdeletion is unknown.14

In the study from Lopez-Rivera et al,10 a large cohort of patients referred with a diagnosis of CAKUT (isolated CAKUT and syndromic CAKUT) were subjected to whole-genome copy number variation analysis followed by: (1) critical examination of the area of overlap in patients with 22q11.2 microdeletion, (2) molecular genetic characterization of the pathogenicity of candidate genes using high-throughput in vivo phenotyping in zebrafish, (3) statistical analysis to determine the mutation burden in candidate genes, and (4) recapitulation of the CAKUT phenotype using global and tissue-specific knockout of the candidate genes in murine models. Using the multitiered strategy, 9 candidate genes were linked to the renal phenotype in DiGeorge syndrome.10 Knockdown of 3 of these genes (snap29, aifm3, and crkl) was found to be associated with renal anomalies in zebrafish. Most importantly, it was shown that targeted knockdown in crkl alone was enough to induce the CAKUT phenotype in zebrafish, and patients with isolated CAKUT were found to have pathogenic mutations in the human homolog (CRKL), thus establishing this gene as a new cause of both syndromic and isolated CAKUT.10

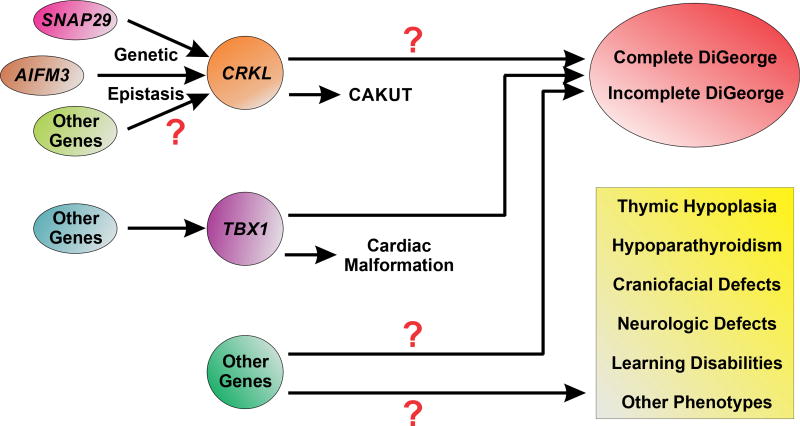

CRKL encodes a 39-kDa Src homology domain–containing adaptor protein with a variety of functions, including cell proliferation, cell migration and adhesion, apoptosis, and the regulation of gene expression.15,16 George et al17 showed that targeted deletion of the CRKL gene and its paralog CRK2 in the kidney induces irregular podocyte morphogenesis and progressive proteinuria. The authors determined that the observed defects in podocyte structure and glomerular filtration barrier integrity were due to loss of a critical hetero-oligomeric interaction between CRKL, CRK2, and nephrin at the slit diaphragm. In the present study, Lopez-Rivera et al demonstrate that isolated knockdown and knockout of the CRKL gene in zebrafish and mice, respectively, recapitulate renal defects observed in patients with DiGeorge syndrome. Furthermore, they showed how neighboring genes (ie, aifm3 and snap29) can interact with one another (genetic epistasis) to produce features consistent with CAKUT phenotype in DiGeorge syndrome (Fig 1). However, it remains unclear how the genes causing CAKUT may interact with genes causing other phenotypes associated with 22q11.2 microdeletions to produce the complete or incomplete spectrum of phenotypic expression seen in DiGeorge syndrome (Fig 1). Taken together, both these studies highlight the significance of CRKL as a critical mediator of macro- and microarchitectural developmental processes in the kidney.

Figure 1.

Proposed mechanism of gene-gene interactions in congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract (CAKUT) and DiGeorge syndrome. Epistatic interactions between CRKL, AIFM3, and SNAP29 have been shown to recapitulate features of CAKUT. Other genes may also contribute to produce the full spectrum of anomalies characteristic of DiGeorge syndrome. Haploinsufficiency of TBX1 has been previously established as a cause of the cardiac malformation associated with the 22q11.2 microdeletion. It remains unclear if there are critical gene-gene interactions with TBX1 that may also contribute to the renal phenotypes characteristic of DiGeorge syndrome. Finally, the potential pathogenic contribution of other genes not characterized in this study to the various phenotypic anomalies associated with DiGeorge syndrome specifically and the 22q11.2 microdeletion more broadly are yet to be determined.

The study by Lopez-Rivera et al is highly significant and innovative because it uses a population-based approach to dissect the genetic basis of a complex phenotype in a highly heterogeneous population and clearly illustrates the strength of multiple tools to establish the genetic basis of complex syndromes. One of the main limitations of the study is the inability to model all 9 candidate genes associated with CAKUT. However, the current findings represent a substantial advance in our understanding of gene-gene interactions in complex hereditary kidney disease. These novel insights may have implications for understanding the genetic basis of other complex malformations and inform the development of targeted therapeutics for the treatment of hereditary kidney disease.

HOW DOES THIS STUDY COMPARE WITH PRIOR STUDIES?

Previous approaches to identifying candidate causal CAKUT genes included the use of classic genetic techniques (eg, linkage analysis and direct sequencing) for the interrogation of large pedigrees. More recently, these modalities have been combined with whole-exome sequencing and other next-generation sequencing strategies to accelerate the pace of gene discovery.18 This approach was used in the identification of CAKUT genes such as ROBO2, DSTYK, and TNXB.9,19,20 However, the method is very challenging because of phenotypic heterogeneity of CAKUT. Consequently, it is not surprising that multiple loci have been reported without a causative gene being identified in some cases.21,22 Others have used a biased candidate gene screening approach in search of mutations in a panel of select genes chosen based on their biological functions and the phenotype induced by disruption of these genes in murine or other animal models. With this approach, Kohl et al23 showed that 12 recessive murine candidate genes were responsible for CAKUT in 2.5% of 574 individuals screened. This approach is laborious, time consuming, and likely more expensive than the approach reported in the study by Lopez-Rivera et al. Furthermore, the candidate gene approach will not allow for the identification of critical gene-gene interactions that may contribute to genetic renal syndromes. In this regard, one of the major findings of the present study is that complex genetic syndromes with multiorgan involvement may not be inherited in classic Mendelian fashion and that a significant number may be due to epistatic interactions between different genes.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS FOR NEPHROLOGISTS?

This study clearly illustrates the merits of using a multiprong approach for understanding the genetic basis of complex malformations and the need for genetic testing when such patients are encountered in clinical practice. Currently, the tools clinicians use to treat children with CAKUT are limited: one can reduce urinary tract infection risk with antibiotic prophylaxis or behavioral modification, or one can use surgery to improve the underlying anatomic anomalies.24,25 Thus, from a clinical perspective, it is crucially important to understand the underlying cause of CAKUT in order to target novel therapies for these patients. Evaluating patients with multiple malformations via advanced genetic testing and functional in vivo modeling will lead to a more sophisticated understanding of the pathogenesis of complex developmental disorders. Further, it may uncover fundamental gene-gene interactions that produce phenotypic variability. To the researcher, the present study shows clearly the power of multidisciplinary collaborative science for the efficient elucidation of the molecular basis of complex medical problems.

Acknowledgments

Support: Dr Gbadegesin is supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) grants 5R01DK098135 and 5R01DK094987. Dr Hall receives funding through the American Society of Nephrology/Amos Medical Faculty Development Program and the P&F grant of the Duke O’Brien Center for Kidney Research. Dr Routh is supported by NIH/NIDDK grant 5K08DK100534.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: The authors declare that they have no relevant financial interests.

Peer Review: Evaluated by an Associate Editor and Deputy Editor Berns.

References

- 1.Annual Report. Rockville, MD: EMMES Corp; 2014. North American Pediatric Renal Transplant Cooperative Study (NAPRTCS) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vivante A, Kohl S, Hwang DY, Dworschak GC, Hildebrandt F. Single-gene causes of congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract (CAKUT) in humans. Pediatr Nephrol. 2014;29(4):695–704. doi: 10.1007/s00467-013-2684-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vainio S, Lin Y. Coordinating early kidney development: lessons from gene targeting. Nat Rev Genet. 2002;3(7):533–543. doi: 10.1038/nrg842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ichikawa I, Kuwayama F, Pope JCT, Stephens FD, Miyazaki Y. Paradigm shift from classic anatomic theories to contemporary cell biological views of CAKUT. Kidney Int. 2002;61(3):889–898. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dressler GR. Advances in early kidney specification, development and patterning. Development. 2009;136(23):3863–3874. doi: 10.1242/dev.034876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schedl A. Renal abnormalities and their developmental origin. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8(10):791–802. doi: 10.1038/nrg2205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reidy KJ, Rosenblum ND. Cell and molecular biology of kidney development. Semin Nephrol. 2009;29(4):321–337. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2009.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Faa G, Gerosa C, Fanni D, et al. Morphogenesis and molecular mechanisms involved in human kidney development. J Cell Physiol. 2012;227(3):1257–1268. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gbadegesin RA, Brophy PD, Adeyemo A, et al. TNXB mutations can cause vesicoureteral reflux. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24(8):1313–1322. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012121148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lopez-Rivera E, Liu YP, Verbitsky M, et al. Genetic drivers of kidney defects in the DiGeorge syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(8):742–754. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1609009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hacıhamdioğlu B, Hacıhamdioğlu D, Delil K. 22q11 deletion syndrome: current perspective. Appl Clin Genet. 2015;8:123–132. doi: 10.2147/TACG.S82105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DiGeorge AM. Discussions on a new concept of the cellular basis of immunology. J Pediatr. 1965;67(5):907–908. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kobrynski LJ, Sullivan KE. Velocardiofacial syndrome, DiGeorge syndrome: the chromosome 22q11.2 deletion syndromes. Lancet. 2007;370(9596):1443–1452. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61601-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yagi H, Furutani Y, Hamada H, et al. Role of TBX1 in human del22q11.2 syndrome. Lancet. 2003;362(9393):1366–1373. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)14632-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feller SM. Crk family adaptors-signalling complex formation and biological roles. Oncogene. 2001;20(44):6348–6371. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Birge RB, Kalodimos C, Inagaki F, Tanaka S. Crk and CrkL adaptor proteins: networks for physiological and pathological signaling. Cell Commun Signal. 2009;7:13. doi: 10.1186/1478-811X-7-13. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1478-811X-7-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.George B, Fan Q, Dlugos CP, et al. Crk1/2 and CrkL form a hetero-oligomer and functionally complement each other during podocyte morphogenesis. Kidney Int. 2014;85(6):1382–1394. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hall G, Gbadegesin RA. Translating genetic findings in hereditary nephrotic syndrome: the missing loops. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2015;309(1):F24–F28. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00683.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lu W, van Eerde AM, Fan X, et al. Disruption of ROBO2 is associated with urinary tract anomalies and confers risk of vesicoureteral reflux. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;80(4):616–632. doi: 10.1086/512735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sanna-Cherchi S, Sampogna RV, Papeta N, et al. Mutations in DSTYK and dominant urinary tract malformations. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(7):621–629. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1214479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Darlow JM, Dobson MG, Darlay R, et al. A new genome scan for primary nonsyndromic vesicoureteric reflux emphasizes high genetic heterogeneity and shows linkage and association with various genes already implicated in urinary tract development. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2014;2(1):7–29. doi: 10.1002/mgg3.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weng PL, Sanna-Cherchi S, Hensle T, et al. A recessive gene for primary vesicoureteral reflux maps to chromosome 12p11-q13. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20(7):1633–1640. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008111199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kohl S, Hwang DY, Dworschak GC, et al. Mild recessive mutations in six Fraser syndrome-related genes cause isolated congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25(9):1917–1922. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013101103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang HH, Gbadegesin RA, Foreman JW, et al. Efficacy of antibiotic prophylaxis in children with vesicoureteral reflux: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Urol. 2015;193(3):963–969. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2014.08.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Routh JC, Bogaert GA, Kaefer M, et al. Vesicoureteral reflux: current trends in diagnosis, screening, and treatment. Eur Urol. 2012;61(4):773–782. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]