Abstract

Psammomatoid juvenile ossifying fibroma (PJOF), a variant of juvenile ossifying fibroma (JOF), is a locally aggressive neoplasm of the children and young adults. This entity has predilection for the sinonasal region. It forms a differential diagnosis for many bone neoplasms. We report three cases of PJOF, in young patients whose biopsy showed the presence of psammomatoid bodies in a cellular fibrous stroma. The diagnosis of JOF indicates requirement of extensive surgery due to its locally aggressive nature.

Keywords: Aggressive, juvenile, psammomatoid

INTRODUCTION

Juvenile ossifying fibroma (JOF) is a rare osseous neoplasm which mainly affects the children and young adults.[1] Trabecular JOF (TJOF) and psammomatoid JOF (PJOF) are the two histological variants described.[2] TJOFs commonly involve the jaw and PJOF, the sinonaso-orbital region. Diagnosing JOF becomes important as it is locally aggressive with a tendency to recur and mimics various other neoplasms clinically, radiologically as well as histologically. We report three such cases of PJOF.

CASE REPORTS

Case 1

An 11-year-old male child presented with proptosis and visual loss of the right eye for 6 months. Computed tomography (CT) brain and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a large osseous mass occupying the nasal cavity, ethmoid and sphenoid sinuses, extending into the medial wall of right orbit and anterior cranial fossa (ACF) base with heterogenous contrast enhancement [Figure 1a and b]. He underwent LeFort osteotomy and near-total excision of the lesion [Figure 1c]. Over the period of next 1 year, the mass progressively increased in size. A year later, he presented with right eye proptosis, nasal block, and complete loss of vision on the right side. On examination, there was right optic atrophy. MRI showed T2 isointense lesion with contrast enhancement in the right nasal cavity and ethmoidal sinus with extension to the ACF base [Figure 1d and e]. Repeat LeFort osteotomy and near-total excision of the lesion were performed. The excision was staged due to severe blood loss. Postoperative imaging showed residue involving ACF base.

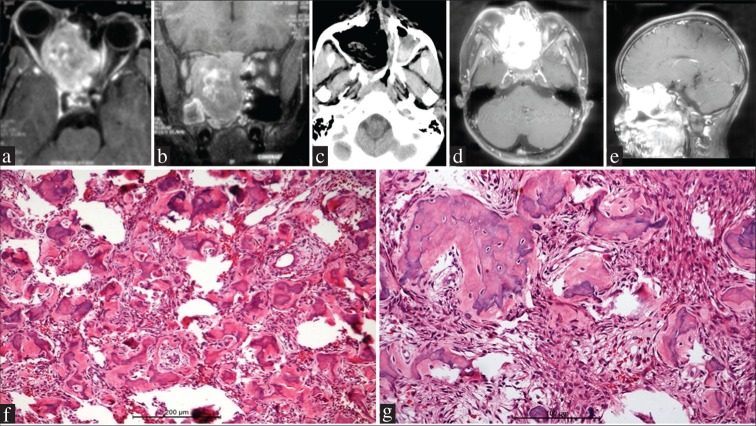

Figure 1.

Case 1. (a and b) Magnetic resonance imaging brain postcontrast axial (a) and coronal (b) sections showing a large tumor occupying the sphenoid and ethmoid sinuses, extending into the medial wall of the right orbit and displacing the globe. The tumor enhances well on contrast and is extending into the anterior cranial fossa base and filling the nasal cavity (c) Postoperative computed tomographic scan showing near-total resection of the tumor. (d and e) Magnetic resonance imaging brain postcontrast axial (c) and sagittal (d) sections performed 1 year later showing regrowth of the contrast enhancing tumor involving paranasal sinuses and nasal cavity, with anterior cranial fossa base infiltration (f and g) Spherical calcified ossicles resembling psammoma bodies are embedded in a cellular fibrous stroma. The ossicles have irregular margins in contrast to psammoma bodies and are variably calcified (f = H and E, ×200; g = H and E, ×400)

Histopathology revealed a fibro-osseous lesion composed of fragments of woven bony psammomatoid bodies in a cellular background, composed of spindle cells forming a fibrous stroma.

There was no atypia in the cellular component [Figure 1f and g]. Over the next 6 months, the residual tumor further progressed. This time, he underwent a bifrontal approach and transcranial transbasal radical complete excision of the tumor. Postoperatively, he had meningitis which responded to antibiotics and he had an uneventful recovery.

Case 2

A 15-year-old female child presented with a swelling over the left side of the face for 1 month. MRI showed a 3.5 cm × 2.9 cm × 3.6 cm well-defined lesion showing moderate heterogeneous contrast enhancement in the left frontal sinus and left ethmoid sinus invading the left orbit and having intranasal extension. She underwent resection of the lesion.

Histopathologic examination of the tissue showed a cellular tumor composed of spindle cells which were arranged in fascicles and whorls. Many spherical bodies with a basophilic center and vague concentric lamination resembling psammoma bodies were seen among these spindle cells. The stroma was fibrous. Mitotic activity was not conspicuous [Figure 2a and b]. Immunohistochemistry with epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) showed these cells to be negative, thus ruling out a meningioma.

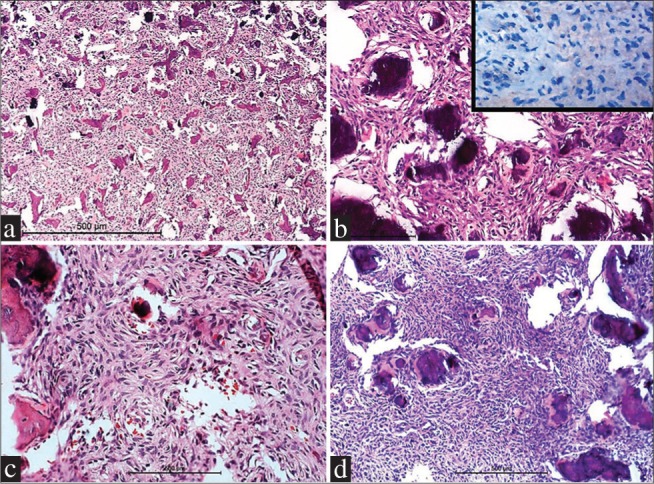

Figure 2.

Case 2 (a and b) and Case 3 (c and d) showing basophilic psammomatoid ossicles in a cellular background of fibroblastic tissue. Tumor cells are negative for epithelial membrane antigen (inset, B) (a = H and E, ×100; b = H and E, ×400, c and d = H and E, ×200)

Case 3

An 11-year-old female child presented with 1-month history of swelling over the right scalp. CT scans revealed a right frontal intradiploic expansile lesion. Clinical differentials considered were histiocytosis and meningioma. She underwent craniotomy and excision of the lesion. Histopathological examination showed a spindle cell tumor with intervening spherical ossicles and new bone formation. The tumor was cellular but had bland cellular morphology [Figure 2c and d]. Immunohistochemistry for EMA was negative in the tumor cells which were positive for vimentin.

DISCUSSION

JOF is an aggressive fibro-osseous neoplasm with a tendency to invade and recur. Neoplastic, developmental, as well as reactive processes are known to cause fibro-osseous lesions of the head and neck.[3] Overall, the benign fibro-osseous lesions of the head and neck region are uncommon.[1] They include fibrous dysplasia, ossifying fibroma (OF), and cement-osseous dysplasia, which share some histopathological features. OF can be further divided into conventional and juvenile forms.[4] Distinguishing these lesions from each other requires clinical, radiological, and histological correlation. It is essential to accurately diagnose JOF as it is locally aggressive and thus requires extensive surgical resection.

El-Mofty described two histopathological variants of JOF as TJOF and PJOF.[2] PJOF was first reported by Benjamins, in 1938, who named it osteoid fibroma with atypical ossification of the frontal sinus. In 1985, Solomon et al. introduced the term PJOF. In addition to its aggressive behavior, PJOF also has a very strong tendency to recur, 30%–56% of the cases have been reported to have recurrence.[3] JOF affects young age with PJOF occurring in patients < 21 years.[5] The most commonly involved site of JOF is the facial bones (85%), followed by calvarium (12%) and mandibular region (10%). About 3% of the reported cases have been found extracranially.[6,7] In contrast to the TJOF occurring more in the jaws, particularly the maxilla, PJOF is more commonly seen within the sino-naso-orbital regions.[2] The ethmoidal sinuses are most commonly involved, followed by the frontal, maxillary, and the sphenoid sinuses.[7] All the three patients in our study were below 20 years (15 and 11 years) with involvement of sino-orbital region, frontal and ethmoidal sinuses as commonly seen in the studies.

Clinical presentation is varied. JOF usually presents as an asymptomatic swelling of the bone,[8] may manifest with rapid painless expansion of the affected bone mimicking malignancy such as osteosarcoma.[9] Intracranial extension has been discovered in neoplasms arising adjacent to the cribriform plate. There was intracranial extension in one of our cases (Case 1).

Radiographically, JOFs exhibit radiolucent and radiodense areas with thin sclerotic rims. It mimics other bone lesions such as fibrous dysplasia, cemento-OF, aneurysmal bone cyst, osteogenic sarcoma, and osteoblastoma. It is differentiated from fibrous dysplasia by its relatively well-delineated border from the surrounding tissue, as seen in the present cases.[8,10] Aggressive lesions with marked destruction of adjacent structures mimic osteosarcoma radiographically; the lack of periosteal reaction in JOF helps in differentiation.

Histopathology forms the mainstay of diagnosing JOFs. The PJOF is characterised by the presence of spherical ossicles/psammoma bodies in a variably cellular fibrous stroma. Gögl termed the spherical structures as “psammoma-like bodies.”[3] The stroma is fibrous composed of plump spindle-shaped cells arranged as fascicles and whorls surrounding the spherical ossicles, with intervening collagen.

PJOF has to be distinguished from OFs and extracranial meningioma histologically. In OFs, the deposits usually have a smooth contour with a thin radiating fringe of collagen fibers, whereas in PJOF, the collagenous rim is thick and irregular. Meningiomas with psammoma bodies closely mimic PJOF; however, the psammomatoid ossicles in PJOF are different from the acellular spherical true psammoma bodies. The cells in meningioma demonstrate EMA positivity, whereas it is negative in JOFs.

Treatment of PJOF is mainly surgical requiring extensive resection to reduce the possibility of recurrence. Our patients underwent resection of the tumor. One of them had recurrence within a span of 1 year and required resurgery. Surgery is the main treatment modality as radiotherapy has minimal role in JOF.

CONCLUSION

PJOF is a rare, aggressive neoplasm of young age characterized by the presence of calcified spherical ossicles in a variably cellular stroma. This is often mistaken for other neoplasms clinically, radiologically, and histologically. Hence, this neoplasm needs to be considered in the differential diagnosis of osseous lesions of the head and neck in young patients. The tumor requires extensive surgical resection and follow-up, thus making its identification important.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brannon RB, Fowler CB. Benign fibro-osseous lesions: A review of current concepts. Adv Anat Pathol. 2001;8:126–43. doi: 10.1097/00125480-200105000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.El-Mofty S. Psammomatoid and trabecular juvenile ossifying fibroma of the craniofacial skeleton: Two distinct clinicopathologic entities. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2002;93:296–304. doi: 10.1067/moe.2002.121545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Solomon M, Khandelwal S, Raghu A, Carnelio S. Psammomatoid juvenile ossifying fibroma of the mandible: A histochemical insight. Internet J Dent Sci. 2009;7:2. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sarode SC, Sarode GS, Waknis P, Patil A, Jashika M. Juvenile psammomatoid ossifying fibroma: A review. Oral Oncol. 2011;47:1110–6. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2011.06.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patil RS, Chakravarthy C, Sunder S, Shekar R. Psammomatoid type juvenile ossifying fibroma of mandible. Ann Maxillofac Surg. 2013;3:100–3. doi: 10.4103/2231-0746.110081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keles B, Duran M, Uyar Y, Azimov A, Demirkan A, Esen HH, et al. Juvenile ossifying fibroma of the mandible: A case report. J Oral Maxillofac Res. 2010;1:e5. doi: 10.5037/jomr.2010.1205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Foss RD, Fielding CG. Juvenile psammomatoid ossifying fibroma. Head Neck Pathol. 2007;1:33–4. doi: 10.1007/s12105-007-0001-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thankappan S, Nair S, Thomas V, Sharafudeen KP. Psammomatoid and trabecular variants of juvenile ossifying fibroma-two case reports. Indian J Radiol Imaging. 2009;19:116–9. doi: 10.4103/0971-3026.50832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rinaggio J, Land M, Cleveland DB. Juvenile ossifying fibroma of the mandible. J Pediatr Surg. 2003;38:648–50. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2003.50145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patigaroo SA. Juvenile psammomatoid ossifying fibroma (JPOF) of maxilla-a rare entity. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2011;10:155–8. doi: 10.1007/s12663-010-0065-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]