A panel of veterinary and academic experts reviewed current available evidence on age at death for labradors and reached a consensus that their average/typical life span was 12 years of age.1 A prospective cohort study that described the longevity of 39 pedigree adult neutered labradors, showed that 89.7 per cent lived to meet/exceed this typical life span. The study showed that maintenance of lean body mass and reduced accumulation of body fat were associated with attaining a longer than average life span while sex and age at neutering were not associated with longevity.1

The present cohort was derived from 31 litters via 19 known (7 unknown) dams and 12 known (7 unknown) sires enrolled in a prospective longitudinal study at a median age of 6.5 years at the start of the study on July 16, 2004. The last dog died on September 09, 2015 at the age of 17.1 years and the oldest dog, a male, reached 17.9 years. The aim of this study was to compare the longevity of the present cohort fed to maintain a body condition score (BCS) between 2 and 4 on a 5-point scale to three historical comparison groups of pedigree labradors taken from previously published studies. The ‘oldest of the old’ labradors from the present cohort could hold important clues on how to achieve healthy ageing. Further analysis of the cohort’s clinical data is being undertaken with the objective to develop key strategies to increase the health span of dogs:

2004 UK Kennel Club (KC) survey dogs owned/kept by owners and breeders that died in the previous 10 years (1994–2003).2

1987 US ‘Restricted’ group (n=24) fed 25 per cent less than a sex-matched and bodyweight-matched sibling pair to maintain a mean BCS between 4 and 5 on a 9-point scale; 48 puppies from seven litters with seven dams and two sires randomly assigned to feeding group at six weeks of age, started on the study from eight weeks of age in 1987 and followed until death of all dogs in this pair-fed study.3–5

1987 US ‘Control’ group (n=24) initially fed ad libitum and then fed a restricted amount of food to prevent excessive weight gain.

Descriptive statistics are reported for age at death using median, minimum and maximum values. Median age at death was compared using Kruskal-Wallis analysis of variance with post hoc Dunn’s pairwise comparisons. After excluding 32 KC survey dogs that died at <3.5 years of age, survival analysis was used to derive Kaplan-Meier product limit estimates of the survival functions with post hoc pairwise log rank tests and results are reported as median survival time (MST) with 95 per cent confidence intervals. The proportions of dogs surviving to 12 years and those alive at/beyond 15.6 years of age were compared using cross-tabulations with χ2 or Fisher’s exact tests. Level of significance for multiple comparisons was set at P<0.008 using a Bonferroni correction as α/k where α/is 0.05 and k is the number of comparisons (six). A one-sample sign test was used to compare the median age at death of the longevity cohort to the average/typical life span of 12 years for labradors.

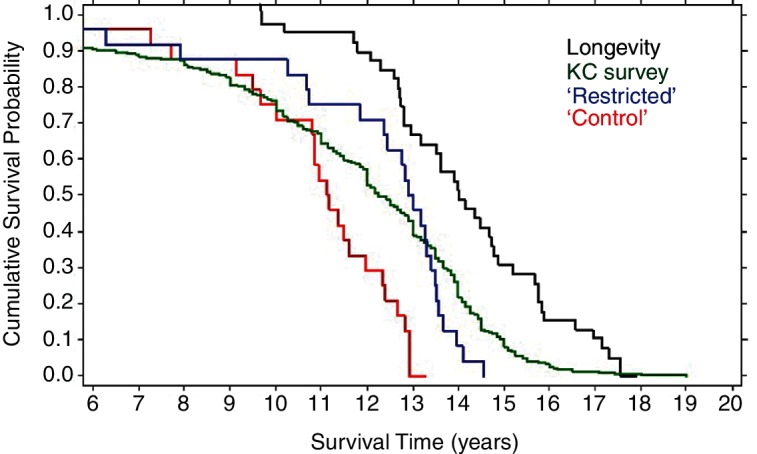

The current cohort lived significantly longer than each of the historical comparison groups (P<0.0001). Survival analysis revealed significant differences in MSTs with the present cohort living longer than each of the other groups (P≤0.004, Table 1, Fig 1). Almost 90 per cent of the present cohort reached the average expected age of 12 years for labrador retrievers while only 30 per cent of the US ‘Control’ group achieved this (P<0.0001, Table 2). Additionally, 28 per cent of the dogs in the present cohort reached/exceeded exceptional longevity, defined as being alive at/beyond 15.6 years of age6 and this was significantly greater than any of the historical comparison groups (P<0.0001, Table 2). Furthermore, the median age at death in the present cohort of 14.01 years was significantly greater than the average/typical life span of 12 years for labrador retrievers (P<0.0001). While age at neutering was not found to be linked to longevity in the present cohort, evaluation of the effect of age of neutering was not possible for the US dogs.5

TABLE 1.

Descriptive statistics for age at death of the four groups of dogs and results of survival analysis

| Group | Descriptive statistics | Survival analysis | ||||

| N | Median age* | (Min-Max) | N | MST† | (95% CI) | |

| Longevity study | 39 | 14.01a | (9.68–17.90) | 39 | 14.01a | (13.18 to 14.77) |

| KC survey | 574 | 12.25b | (0.17–19.00) | 542 | 12.58b | (12.17 to 12.92) |

| ‘Restricted’ | 24 | 12.95b | (4.30–14.56) | 24 | 12.90b | (12.38 to 13.40) |

| ‘Control’ | 24 | 11.16b | (3.50–13.29) | 24 | 11.14c | (10.80 to 11.99) |

*Kruskal-Wallis analysis of variance (P< 0.0001) with post hoc Dunn’s pairwise comparisons: median ages with different superscripts are significantly different from one another.

†MST; Kaplan-Meier log rank P<0.0001; MSTs with different superscripts are significantly different from one another (P≤0.004).

CI, confidence interval; KC, Kennel Club; MST, median survival time.

FIG 1:

Kaplan-Meier survival curves showing that the longevity study group lived significantly longer than the historical comparison groups. KC, Kennel Club.

TABLE 2.

Numbers and proportions of dogs achieving a typical life span (average expected age of 12 years) and an exceptional life span (age of≥15.6 years)

| Group | Total dogs | Dogs reaching typical life span | Dogs reaching exceptional life span | ||||

| N | n | %* | 95% CI | n | %† | 95% CI | |

| Longevity study | 39 | 35 | 89.7a | 74.8 to 96.7 | 11 | 28.20a | 15.6 to 45.1 |

| KC survey | 574 | 302 | 52.61ab | 48.4 to 56.8 | 24 | 4.18b | 2.8 to 6.3 |

| ‘Restricted’ | 24 | 17 | 70.83ab | 48.8 to 86.6 | 0 | 0b | NA |

| ‘Control’ | 24 | 7 | 29.16b | 13.4 to 51.3 | 0 | 0b | NA |

*Proportions (%) with different superscripts are significantly different, P<0.0001.

†Proportions (%) with different superscripts are significantly different, P<0.0001.

CI, confidence interval; KC, Kennel Club.

In spite of being 16 years and 17 years of age, the last five dogs in the present cohort continued to be full of life, active, social and highly engaged with their animal welfare specialists and social groups. This suggests that the dogs experienced an increase in health span and not only in the actual years lived.

The dogs in the present cohort were more closely related than the dogs in the UK KC study but less closely related than the dogs in the US sibling-matched study and this suggests that while genetics is important, it is unlikely to be the primary driver of longevity. The environmental conditions that the dogs in the present cohort experienced were similar to those of the dogs in the US study while the dogs in the KC study were dogs kept by owners belonging to a UK breed club. There are likely to be differences in the living conditions experienced by the different groups of dogs that may have affected longevity. However, the reduced variation and fewer changes over time in management factors of the present cohort provided an opportunity to evaluate life span while controlling for the potential confounding impact of such variables.

The results of this study showed that the present cohort lived significantly longer than previously studied labradors and had a greater than expected proportion living well beyond that of the expected breed life span, despite the limitations of using historical comparison groups and the fact that all of these groups of dogs are inherently biased. These 39 labradors experienced a combination of a high quality plane of nutrition with appropriate husbandry and healthcare. Increased understanding and control of the ageing process provides an opportunity to estimate the impact of the longevity dividend. For human beings this is defined as the social, economic and health bonuses for both individuals and populations that accrue as a results of medical interventions to slow the rate of ageing.7 The importance of the ‘oldest of the old’ dogs as reported here is that they can provide a model system for exploring the longevity dividend in human beings as well as dogs.8

Footnotes

Competing interests: VJA and JP received payment from Spectrum Brands (and formerly P&G) for provision of analytical services and interpretation of data. KC and DMM are employees of Spectrum Brands (and formerly of P&G).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Adams VJ, Watson P, Carmichael S, et al. . Exceptional longevity and potential determinants of successful ageing in a cohort of 39 Labrador retrievers: results of a prospective longitudinal study. Acta Vet Scand 2016;58:29 10.1186/s13028-016-0206-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adams VJ, Evans KM, Sampson J, et al. . Methods and mortality results of a health survey of purebred dogs in the UK. J Small Anim Pract 2010;51:512–24. 10.1111/j.1748-5827.2010.00974.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kealy RD, Lawler DF, Ballam JM, et al. . Effects of diet restriction on life span and age-related changes in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2002;220:1315–20. 10.2460/javma.2002.220.1315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lawler DF, Evans RH, Larson BT, et al. . Influence of lifetime food restriction on causes, time, and predictors of death in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2005;226:225–31. 10.2460/javma.2005.226.225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lawler DF, Larson BT, Ballam JM, et al. . Diet restriction and ageing in the dog: major observations over two decades. Br J Nutr 2008;99:793–805. 10.1017/S0007114507871686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Waters DJ, Kengeri SS, Clever B, et al. . Exploring mechanisms of sex differences in longevity: lifetime ovary exposure and exceptional longevity in dogs. Aging Cell 2009;8:752–5. 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2009.00513.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olshansky SJ, Perry D, Miller RA, et al. . In pursuit of the longevity dividend. Scientist 2006;20:28–36. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Creevy KE, Austad SN, Hoffman JM, et al. . The Companion Dog as a Model for the Longevity Dividend. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2016;6:a026633 10.1101/cshperspect.a026633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]