Abstract

Background

Moxifloxacin is a second-line anti-TB drug that is useful in the treatment of drug-resistant TB. However, little is known about its target site pharmacokinetics. Lower drug concentrations at the infection site (i.e. in severe lung lesions including cavitary lesions) may lead to development and amplification of drug resistance. Improved knowledge regarding tissue penetration of anti-TB drugs will help guide drug development and optimize drug dosing.

Methods

Patients with culture-confirmed drug-resistant pulmonary TB scheduled to undergo adjunctive surgical lung resection were enrolled in Tbilisi, Georgia. Five serum samples per patient were collected at different timepoints including at the time of surgical resection (approximately at Tmax). Microdialysis was performed in the ex vivo tissue immediately after resection. Non-compartmental analysis was performed and a tissue/serum concentration ratio was calculated.

Results

Among the seven patients enrolled, the median moxifloxacin dose given was 7.7 mg/kg, the median age was 25.2 years, 57% were male and the median creatinine clearance was 95.4 mL/min. Most patients (71%) had suboptimal steady-state serum Cmax (total drug) concentrations. The median free moxifloxacin serum concentration at time of surgical resection was 1.23 μg/mL (range = 0.12–1.80) and the median free lung tissue concentration was 3.37 μg/mL (range = 0.81–5.76). The median free-tissue/free-serum concentration ratio was 3.20 (range = 0.66–28.08).

Conclusions

Moxifloxacin showed excellent penetration into diseased lung tissue (including cavitary lesions) among patients with pulmonary TB. Moxifloxacin lung tissue concentrations were higher than those seen in serum. Our findings highlight the importance of moxifloxacin in the treatment of MDR-TB and potentially any patient with pulmonary TB and severe lung lesions.

Introduction

The global health impact of TB is substantial. TB has emerged as the leading cause of death due to an infectious disease with an estimated 1.8 million deaths per year; TB is now one of the top 10 causes of mortality worldwide.1 The global emergence of MDR-TB and XDR-TB is an enormous public health threat and major barrier to effective TB control. In the recently adapted ‘End TB Strategy’ one of the three main pillars of the pathway to eliminate TB was to intensify research and innovation including the optimization of new and currently available drugs.2,3 One promising area of research aimed at optimizing available treatments is the study of the pharmacokinetics of anti-TB drugs and in particular the concentrations of drugs at the site of disease in pulmonary TB.4

The fluoroquinolones are considered cornerstone drugs for the treatment of drug-resistant TB and their use has been associated with a significantly higher odds of treatment success among patients with MDR-TB and XDR-TB.5 Moxifloxacin in particular is a promising higher-generation fluoroquinolone with potent in vitro and early bactericidal activity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis6 and activity against non-replicating M. tuberculosis persisters in vitro.7 Fluoroquinolones exhibit concentration-dependent killing and the pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic indices Cmax/MIC and AUC/MIC are both important in determining optimal drug activity.8–10 Serum drug concentrations are used for these indices; however, for any drug to exert its maximal pharmacological effect it has to get to the target site at sufficiently high free concentrations.9

The primary organ in which M. tuberculosis causes disease is the lung, and lesions there are varied, ranging from a small infiltrate to a cavitary lesion, which is a hallmark of progressive pulmonary TB. Advanced lung lesions are characterized by necrosis and decreased vascularization, features that may not be conducive for drug penetration. Available clinical data have shown that cavitary lesions are associated with worse clinical outcomes, including increased risk of relapse and development of acquired drug resistance. One hypothesis is that this is due to lower drug concentrations in such cavitary lesions.11 Recent advancements in technology have created new opportunities to carry out studies to address the important issue of drug concentration at the site of disease. Recent work by Prideaux et al.4 utilized a MALDI-TOF MS imaging technique to investigate the spatial distribution of moxifloxacin in infected human lung tissue among patients with TB; however, there is a lack of additional data and in particular no information on moxifloxacin free drug concentrations in the lungs of patients with TB. In regards to the fluoroquinolones, only free drug can penetrate into the bacterial cell and bind to its target, DNA gyrase. In order to quantitatively capture free moxifloxacin concentrations inside lung lesions, we utilized the method of microdialysis, an emerging technique that allows for the measurement of unbound drug in the extracellular space of virtually any tissue.12,13 Improved knowledge regarding tissue penetration of anti-TB drugs will help guide drug development and optimize drug dosing and management.

Patients and methods

Study population

Patients with culture-confirmed pulmonary TB receiving moxifloxacin and scheduled to undergo adjunctive surgical lung resection were enrolled from the National Center for Tuberculosis and Lung Diseases (NCTLD) in Tbilisi, Georgia. All patients were receiving 400 mg of moxifloxacin orally given by directly observed therapy (‘DOT’) and on the day of surgery received moxifloxacin orally with a few millilitres of water approximately 2 h prior to surgical resection. Five of the seven patients included in this study were part of a previous report on the pharmacokinetics of pyrazinamide where detailed study methodologies can be found.14

Ethics

All study participants provided informed consent and the study was approved by the NCTLD (IRB00009508), Emory University (IRB00062584) and University of Florida (IRB201300419) Institutional Review Boards.

Serum pharmacokinetics

On the day of surgery, serum samples were collected at 0, 2, 4 and 8 h after receiving moxifloxacin. Another serum sample was collected at the time of lung resection (∼2 h after drug administration, which was the expected Tmax of moxifloxacin). The collected samples were stored in a −80 °C freezer until shipment to the University of Florida Infectious Disease Pharmacokinetics Laboratory (IDPL). At the IDPL, drug concentrations were measured using a validated LC-MS/MS assay on a Thermo Scientific TSQ Quantum Ultra LC-MS-MS system (serial number: TQU03470) and an Accela 1250 UHPLC pump (serial number: 925147) with a model Accela Open PAL autosampler (serial number: 240091), a Dell Dimension computer and Thermo Scientific Corp. Xcalibur 2.2 SP1.48 analytical software. The lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) was 0.2 μg/mL. The moxifloxacin recovery from human plasma was 100%. The overall inter-batch precision of quality controls ranged from 1.88% to 8.39%.

Tissue pharmacokinetics

Immediately after surgical resection, microdialysis was performed in the ex vivo lung tissue. The microdialysis probe was inserted into the central area of the resected lesion. The inner lesion location of probe placement was confirmed after microdialysis when the lesion was bisected and placement was verified visually. As previously described, the ‘no net flux’ method was utilized for calibration and determination of tissue concentrations.14,15 To perform microdialysis, four different concentrations of moxifloxacin (0.5, 3, 10 and 20 μg/mL) in Ringer’s solution were infused for ∼35–40 min each. The collected microdialysates were kept in a −80 °C freezer until shipment to the University of Florida IDPL. A modification of the assay described above was used to quantify moxifloxacin in microdialysate solution (free drug). Here, samples utilized to prepare the standard curves were diluted in saline. The LLOQ was 0.02 μg/mL and the overall inter-batch precision of quality controls ranged from 5.16% to 6.98%.

Laboratory

Acid fast bacillus (AFB) smear and culture examinations were performed on the sputum and tissue samples obtained. Tissue samples also underwent pathological examination. All laboratory methods are as previously described.14

Radiology

When available, preoperative chest CT scans were reviewed independently by two Emory University chest radiologists. They described the dominant abnormality as a mass, cavitary or infiltrate lesion.

Data analysis

Non-compartmental analysis (NCA) was performed in Phoenix WinNonlin® and apparent total body clearance and volume of distribution (CL/F and V/F), half-life (t½), elimination rate constant (kel), maximum serum concentration and time at which it occurred (Cmax and Tmax) as well as area under the concentration–time curve (AUC) were determined. Concentration values for data points below the LLOQ were replaced with half the LLOQ value. A tissue/serum concentration ratio was calculated using the free serum concentration at time of surgical resection. Free serum concentrations were calculated by multiplying total serum concentrations times expected fraction unbound (0.49).16–19 The Mann–Whitney U-test (or Wilcoxon rank sum test)20 was used to investigate potential differences in median free moxifloxacin lung tissue concentrations and lung tissue/serum ratios between culture-positive and culture-negative patients as well as between patients with different lesion types. Further data analyses were done using SAS® software, version 9.4.

Results

Study population

Seven patients undergoing surgical resection for drug-resistant TB were enrolled (Table 1). The median age was 25.2 years; over half were male (57%) and had no history of prior TB treatment before TB diagnosis (57%). No patients had HIV infection or diabetes mellitus; three patients (43%) were coinfected with either hepatitis B (2) or C (1) virus. The median BMI was 19.5 kg/m2, while median creatinine clearance was 95.4 mL/min and albumin was 4.0 g/dL. One patient had isoniazid-resistant and rifampicin-susceptible TB, while three patients had MDR-TB (resistance to both isoniazid and rifampicin) and three patients had XDR-TB (resistance to isoniazid, rifampicin, ofloxacin and at least one injectable second-line agent, i.e. amikacin, kanamycin or capreomycin). All patients were receiving 400 mg of moxifloxacin daily at the time of surgery for a median of 266 days prior to the surgical procedure and at a median dose of 7.7 mg/kg.

Table 1.

Study population characteristics for seven patients with drug-resistant pulmonary TB

| Parameter | Valuea |

|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | |

| male | 4 (57) |

| age (years) | 25.2 (20–54) |

| Georgian ethnicityb | 4 (57) |

| hepatitis C antibody positive | 1 (14) |

| hepatitis B surface antigen positive | 2 (29) |

| current alcohol use | 0 |

| current tobacco use | 2 (29) |

| prior treatment for TB | 3 (43) |

| weight (kg) | 52.0 (49–74) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 19.5 (15–25) |

| Laboratory values | |

| creatinine clearancec (mL/min) | 95.4 (72–141) |

| albumin level (g/dL) | 4.0 (3.5–4.9) |

| haemoglobin level (g/dL) | 13.0 (10.7–15.5) |

| ALT level (U/L) | 14 (10–133) |

| TB characteristics and treatment | |

| drug susceptibility pattern | |

| isoniazid monoresistant | 1 (14) |

| MDR | 3 (43) |

| XDRd | 3 (43) |

| receiving 400 mg of moxifloxacine | 7 (100) |

| moxifloxacin (mg/kg) | 7.7 (5.4–8.2) |

| days receiving moxifloxacin | 266 (13–415) |

| type of surgery | |

| lobectomy | 3 (43) |

| segmentectomy | 4 (57) |

Data are presented either as number (%) or median (range).

1 Armenian, 1 Azeri and 2 other.

Using the Cockcroft–Gault equation.32

Resistance to isoniazid, rifampicin, ofloxacin and at least one injectable second-line agent (i.e. amikacin, kanamycin or capreomycin).

At time of surgical resection.

Serum pharmacokinetics

The total serum concentration–time profiles are shown in Figure 1. Among the seven patients, only two (29%) had Cmax concentrations within the recommended range of 3–5 μg/mL based on a 400 mg daily dose.21 The median t½ (7.0 h) was similar to values reported in the literature for TB patients, while the Tmax (2.0 h) was slightly higher. There was no significant correlation between moxifloxacin dose (mg/kg) and serum Cmax (R = 0.40, P = 0.37). Further NCA results are shown in Table 2.

Figure 1.

Moxifloxacin free + bound serum concentrations versus time in adults with drug-resistant TB.

Table 2.

NCA of serum moxifloxacin concentrations

| Parameter | Moxifloxacin (n = 7), median (range) |

|---|---|

| kel (h−1) | 0.099 (0.032–0.792) |

| t½ (h) | 7.0 (0.9–21.9) |

| Tmax (h) | 2.0 (1.8–2.0) |

| Cmax (μg/mL) | 2.6 (0.24–4.5) |

| AUClast (μg·h/mL) | 14.2 (0.94–22.2) |

| AUC0–∞ (μg·h/mL) | 28.3 (1.1–49.3) |

| CL/F (L/h) | 14.1 (8.1–353.6) |

| V/F (L) | 142.5 (94.2–896.7) |

kel, elimination rate constant; t½, half-life; Tmax, time to Cmax; Cmax, maximum serum concentration; AUClast, area under the concentration–time curve from time zero to time of last measurable concentration; AUC0–∞, area under the concentration–time curve from time zero to infinity; CL, clearance; V, volume of distribution; F, bioavailability (assumed to be 1 for purposes of analysis).

Tissue pharmacokinetics

The median lung tissue concentration of free (non-protein-bound) moxifloxacin was 3.37 μg/mL with a range of 0.81–5.76 μg/mL. In comparison with the serum free concentration of moxifloxacin at the time of surgical resection (imputed based on well-recognized moxifloxacin protein-binding literature values),16–19 the median tissue/serum concentration ratio was 3.20 (range = 0.66–28.08) (Table 3); with the exception of one subject all patients had ratios >1. There was no significant correlation between moxifloxacin free serum and tissue concentrations (R = −0.13, P = 0.78).

Table 3.

Comparison of free serum and cavitary moxifloxacin concentrations among patients with drug-resistant pulmonary TB

| ID | Dose (mg/kg) | Serum concentration at time of resectiona (μg/mL) | Tissue concentration (μg/mL) | Tissue/serum ratio | Tissue culture | Radiology (dominant lesion) | Pathology, necrosis/ AFB staining |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5.4 | 1.23 | 0.81 | 0.66 | positive | cavitary | 1/1 |

| 2 | 8.0 | 1.24 | 1.25 | 1.01 | positive | cavitary | 2/2 |

| 3 | 8.0 | 1.40b | 1.74 | 1.24 | negative | mass | 3/3 |

| 4 | 8.2 | 0.46 | 3.55 | 7.70 | positive | cavitary | 3/3 |

| 5 | 7.7 | 1.80 | 5.76 | 3.20 | negative | cavitary | 2/1 |

| 6 | 6.4 | 0.16 | 4.36 | 27.21 | negative | mass | 3/2 |

| 7 | 5.7 | 0.12 | 3.37 | 28.08 | negative | consolidation | 1/0 |

| Median (range) | 7.7 (5.4–8.2) | 1.23 (0.12–1.80) | 3.37 (0.81–5.76) | 3.20 (0.66–28.08) |

Necrosis: 0, not present; 1 (rare), scattered within a field; 2 (moderate), confluent within a field; 3 (severe), present in multiple confluent fields.

AFB staining: 0, not present; 1, rare; 2, scattered in a field; 3, many in a field.

Free serum concentration = measured moxifloxacin concentration × 0.49.16–19

Serum concentration at time of resection was simulated for subject 3 using a one-compartment body model.

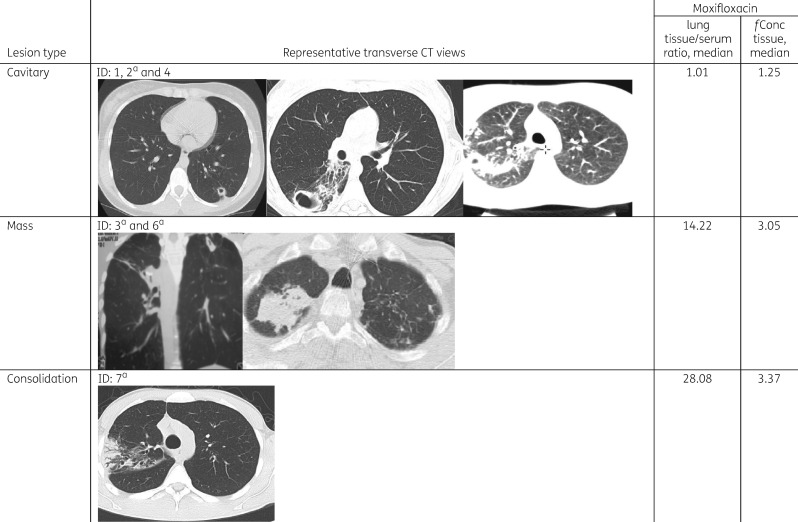

Radiology

Among the seven patients, six had chest CT scans available for review. Cavitary (three) and mass (two) lesions were the dominant abnormalities with the other main lesion identified as a consolidation (one) (Table 3). For the one patient without an available CT for review, the official read of the CT scan in Georgia reported the presence of a cavitary lesion. The lowest free moxifloxacin lung tissue concentrations and tissue/serum ratios were observed in patients with cavitary lesions, followed by mass type lesions and one patient with a consolidation (Figure 2). However, there were no significant differences in the median free moxifloxacin lung tissue concentrations and lung/serum concentration ratios among the four patients with cavitary disease as compared with the two patients with mass lesions.

Figure 2.

Comparison of radiology, moxifloxacin lung tissue/serum concentration ratios and free lung tissue concentration. Among six patients with films available for review three main lesion types were identified including cavitary lesions, mass lesions and one patient with an infiltrate (consolidation). aThe results for subjects 2, 3, 6 and 7 were reported in part in a previous report evaluating the tissue penetration of pyrazinamide.14fConc tissue, free concentration in lung tissue (μg/mL).

Laboratory results

Pathology

All tissue samples revealed the presence of granulomas and necrosis with most having areas of moderate to severe necrosis (5/7, 71%). Six (86%) of seven demonstrated vascularization and fibrosis surrounding granulomas and were AFB smear positive (Table 3). No significant correlations were found between lung tissue moxifloxacin concentrations based on the level of necrosis (R = 0.26, P = 0.58) or AFB quantification (R = −0.17, P = 0.71). Similarly, there was no significant correlation found between the lung tissue/serum moxifloxacin concentration ratio based on the level of necrosis (R = −0.04, P = 0.94) or AFB quantification (R = −0.38, P = 0.40).

Microbiology

Tissue cultures from three patients were positive for M. tuberculosis (Table 3). When comparing the three culture-positive patients with the four culture-negative patients, there was a trend towards lower median moxifloxacin lung tissue concentrations (1.25 versus 3.87) and median lung tissue/serum concentration ratios (1.01 versus 15.21) in patients who were culture positive, but the results were not statistically significant. Of note, two of the three patients with a positive tissue culture had the two lowest moxifloxacin tissue concentrations.

Discussion

We found excellent lung tissue penetration (including cavitary lesions) of moxifloxacin in a cohort of patients with drug-resistant pulmonary TB who were undergoing adjunctive surgery. Overall serum total drug exposure was relatively low in our study population; median AUC0–∞ and Cmax were 28.3 μg·h/mL and 2.6 μg/mL, respectively, and the majority of patients (71%) had suboptimal peak concentrations (below the recommended range of 3–5 μg/mL). These findings suggest the need for dose optimization and highlight the potential benefit of therapeutic drug monitoring in the treatment of drug-resistant TB.

The serum drug concentrations among our study cohort were lower as compared with two other studies reported in the literature. Among 12 young healthy volunteers, Lubasch et al.22 observed a Cmax of 4.34 μg/mL and total AUC of 39.3 μg·h/mL after a single dose of 400 mg of moxifloxacin. In another clinical pharmacology study among nine pulmonary TB patients from Brazil receiving 400 mg of moxifloxacin daily, the median Cmax and AUC were 6.13 μg/mL (range = 4.47–9.00) and 55 μg·h/mL (range = 36–79), respectively.23 The patient characteristics (median age, body weight and creatinine clearance) of these patients were similar to our Georgian study cohort. One explanation for the lower serum concentrations in our study population may be a cohort selection bias, since subjects enrolled in this study were chosen to undergo surgery due in part to their lack of clinical improvement after prolonged treatment. In addition, anaesthesia may have affected drug absorption on the day of surgery.24 Premedication with morphine, pethidine and anticholinergics, as well as the small volume of water administered with moxifloxacin prior to surgery, have been shown to affect pharmacokinetic parameters by delaying gastric emptying and consequently drug absorption.25

Interestingly, even in patients with low serum concentration a considerable amount of drug was found in their lung tissue and the lung concentrations were noticeably higher than the serum moxifloxacin concentrations. The median free (unbound to proteins) lung tissue concentration was 3.37 μg/mL (range = 0.81–5.76 μg/mL). Tissue concentrations may have been higher when compared with free serum concentrations for a variety of potential reasons: clearance from the tissue may have been different compared with serum; a delay in target site penetration; and accumulation of moxifloxacin in macrophages from which drug can be released again into the extracellular space (similar to a depot effect). The accumulation of moxifloxacin in macrophages in vitro has been reported previously.26 Also, for reasons mentioned above, serum concentrations on the day of surgery may have been lower than usual while there still was drug in the tissue (depot effect), resulting in a greater tissue/serum concentration ratio. We observed a broad range of tissue/serum concentration ratios (range = 0.66–28.08; median = 3.20), which is mainly due to very low serum concentrations (close to zero) in subjects 6 and 7 (their tissue concentrations were close to the median of 3.37 μg/mL). Without these two subjects a narrower range of tissue/serum concentration ratios is obtained (0.66–7.70).

In conformity with our results, Prideaux et al.4 reported an average moxifloxacin caseum/plasma concentration ratio of ∼3 both in patients receiving a single dose and in those given multiple doses (steady-state group). Total drug concentrations in caseum (ng/g of tissue) were determined after homogenizing the respective tissue and compared with total serum concentrations (ng/mL). Their work also illustrated a heterogeneous distribution of several drugs (including moxifloxacin) within the tissue between cellular and acellular parts of diseased lung. In general, whole tissue homogenates have certain limitations such as the unknown tissue binding of a drug (including inter-patient variability), the potentially heterogeneous distribution of a drug within the tissue before homogenization (surrounding uninvolved lung tissue, fibrous wall, necrotic centre/caseum) and the fact that they do not consider the intracellular accumulation of certain drugs inside, for instance, immune cells. Due to this, some of the moxifloxacin accumulates inside macrophages, and thus will not be available for bacterial kill outside of the cell,26 where persisting bacilli are typically found. In contrast, microdialysis, which was used in our study, overcomes these limitations as it measures only the unbound drug, i.e. the pharmacologically active moiety. Microdialysis is a minimally invasive technique that has been utilized for several decades in drug development, clinical drug monitoring and dose optimization of anti-infective agents, but has been little used to measure drug concentrations in the lung.12 While it has been used in patients in vivo during and after cardiothoracic surgery,27 our group has used resected lung ex vivo to perform microdialysis.14,15 While this does not allow the measurement of certain pharmacokinetic parameters such as Cmax and AUC, it does allow for the use of the ‘no net flux’ method of calibration,28 which is considered the optimal microdialysis technique for obtaining an accurate drug concentration measurement. Additionally, using ex vivo lung tissue limits any risk of harm to the patient. Another advantage of microdialysis is that it measures drug concentrations in the extracellular space,12 where persisting bacilli are mainly located;29 eradicating this small population of bacilli remains a major therapeutic challenge.

In another prospective open-label pharmacokinetic study, Breilh et al.30 investigated the degree of moxifloxacin lung tissue diffusion at steady-state in 49 patients undergoing lung surgery for bronchial cancer. The mean ratios between lung tissue homogenate and plasma concentrations after intravenous and oral administration were 3.53 (SD ± 1.89) and 4.36 (SD ± 1.48), respectively. Although whole tissue concentrations are difficult to interpret with respect to clinical relevance, these results were slightly higher and yet similar to the drug concentration ratios we found and provide further evidence of the high degree of lung tissue penetration of moxifloxacin. Higher tissue protein binding as compared with plasma protein binding may be an explanation for higher tissue/plasma ratios when measuring whole lung concentrations. One important factor for a higher lung tissue/serum ratio (when compared with a TB lesion/serum ratio) is that moxifloxacin penetration from uninvolved lung tissue into TB lesions may be hindered to a certain extent. Unfortunately, we did not measure drug concentrations in the surrounding lung tissue, which is a limitation being addressed in future studies.

Our study is subject to certain limitations. First, a small number of patients were enrolled into this study, which contributed to a considerable variability in the data. Free serum moxifloxacin concentrations at the time of surgical resection were imputed based on well-recognized literature values for moxifloxacin protein binding (∼51%).16–19 Inter-individual variability in the protein binding may have contributed to the variability in free-tissue/free-serum concentration ratios. Further, after removal of the lesion via surgical resection, microdialysis was immediately performed; this process took ∼3 h. Given the heterogeneous distribution of moxifloxacin in TB lesions,4 drug redistribution between regions of high concentrations (e.g. macrophage layers) and lower concentrations (e.g. necrotic foci) may have contributed to the relatively high variability in free-tissue/free-serum concentration ratios. Moreover, for ethical reasons the measurement of in vivo moxifloxacin lung concentrations over time was not feasible. Hence, lung tissue concentrations at only one timepoint per patient (immediately after lung tissue resection) were determined. This prevents the calculation of a target site AUC. Since the AUC/MIC ratio represents the most relevant pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic index for moxifloxacin, the AUC at the infection site would be a valuable parameter to ascertain in future studies. Additionally, the relatively small number of patients made it hard to determine if there are any identifiable predictors of higher tissue penetration such as radiological or pathological features and the clinical significance of low tissue concentrations.

Based on the rather low Cmax values in our study cohort and the recommended target Cmax range of 3–5 μg/mL (total drug),21 most patients would require an increased dose of 600–800 mg. The use of higher doses in the 600–800 mg range was previously suggested by Gumbo et al.31 based on an in vitro study where mycobacteria were exposed to free moxifloxacin serum concentrations in the hollow-fibre infection model system. However, our measured free lung tissue concentrations suggest that more than half of the patients had sufficient target site exposure at a daily dose of 400 mg. The accumulation of moxifloxacin at the target site should thus be taken into account in future in vitro pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic studies to further improve the translation from in vitro experiments to clinical application.

In summary, moxifloxacin showed excellent penetration into the diseased tissue of patients with pulmonary TB including those with cavitary disease as well as a variety of other radiological lesion types. The findings of our study emphasize the important role of moxifloxacin in second-line therapy as well as in patients with progressive and severe lung lesions.

Acknowledgements

The findings of this study were presented, in part, at the Twenty-seventh European Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ECCMID), Vienna, Austria, 2017 (Abstract Number P1197) and the ECCMID satellite meeting of the ESCMID PK/PD of Anti-Infectives Study Group/International Society of Anti-Infective Pharmacology (EPASG/ISAP), Vienna, Austria, 2017.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health Fogarty International Center (D43TW007124), the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (K23AI103044; R21AI122001), the Atlanta Clinical and Translational Science Institute (UL1TR000454), Georgia Clinical & Translational Science Alliance (UL1TR002378) and the Emory University Global Health Institute.

Transparency declarations

None to declare.

References

- 1. WHO. Global Tuberculosis Report 2016 (WHO/HTM/TB/2016.13). Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 2016. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/250441/1/9789241565394-eng.pdf?ua=1. [Google Scholar]

- 2. WHO. A Global Action Framework for TB Research: In Support of the Third Pillar of WHO’s End TB Strategy (WHO/HTM/TB/2015.26). Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 2015. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/195772/1/9789241509756_eng.pdf?ua=1. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lienhardt C, Lönnroth K, Menzies D. et al. Translational research for tuberculosis elimination: priorities, challenges, and actions. PLoS Med 2016; 13: e1001965.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Prideaux B, Via LE, Zimmerman MD. et al. The association between sterilizing activity and drug distribution into tuberculosis lesions. Nat Med 2015; 21: 1223–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bastos ML, Hussain H, Weyer K. et al. Treatment outcomes of patients with multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis according to drug susceptibility testing to first- and second-line drugs: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 59: 1364–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pletz MWR, De Roux A, Roth A. et al. Early bactericidal activity of moxifloxacin in treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis: a prospective, randomized study. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2004; 48: 780–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lakshminarayana SB, Huat TB, Ho PC. et al. Comprehensive physicochemical, pharmacokinetic and activity profiling of anti-TB agents. J Antimicrob Chemother 2015; 70: 857–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Vaddady PK, Lee RE, Meibohm B.. In vitro pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic models in anti-infective drug development: focus on TB. Future Med Chem 2010; 2: 1355–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Drusano G. Antimicrobial pharmacodynamics: critical interactions of ‘bug and drug’. Nat Rev Microbiol 2004; 2: 289–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Scaglione F. Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) considerations in the management of Gram-positive bacteraemia. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2010; 36 Suppl 2: S33–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kempker RR, Kipiani M, Mirtskhulava V. et al. Acquired drug resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis and poor outcomes among patients with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Emerg Infect Dis 2015; 21: 992–1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Deitchman AN, Heinrichs MT, Khaowroongrueng V. et al. Utility of microdialysis in infectious disease drug development and dose optimization. AAPS J 2017; 19: 334–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Azeredo FJ, Dalla Costa T, Derendorf H.. Role of microdialysis in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics: current status and future directions. Clin Pharmacokinet 2014; 53: 205–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kempker RR, Heinrichs MT, Nikolaishvili K. et al. Lung tissue concentrations of pyrazinamide among patients with drug-resistant pulmonary tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2017; 61: e00226-17.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kempker RR, Barth AB, Vashakidze S. et al. Cavitary penetration of levofloxacin among patients with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2015; 59: 3149–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Stass H, Dalhoff A, Kubitza D. et al. Pharmacokinetics, safety, and tolerability of ascending single doses of moxifloxacin, a new 8-methoxy quinolone, administered to healthy subjects. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1998; 42: 2060–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ostergaard C, Sørensen TK, Knudsen JD. et al. Evaluation of moxifloxacin, a new 8-methoxyquinolone, for treatment of meningitis caused by a penicillin-resistant pneumococcus in rabbits. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1998; 42: 1706–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Müller M, Stass H, Brunner M. et al. Penetration of moxifloxacin into peripheral compartments in humans. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1999; 43: 2345–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. US FDA. NDA 21-085 Avelox Clinical Pharmacology and Biopharmaceutics Review.1998. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/99/21-085_Avelox_biopharmr.pdf.

- 20. LaMorte WW. Mann Whitney U Test (Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test) http://sphweb.bumc.bu.edu/otlt/mph-modules/bs/bs704_nonparametric/BS704_Nonparametric4.html.

- 21. Alsultan A, Peloquin CA.. Therapeutic drug monitoring in the treatment of tuberculosis: an update. Drugs 2014; 74: 839–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lubasch A, Keller I, Borner K. et al. Comparative pharmacokinetics of ciprofloxacin, gatifloxacin, grepafloxacin, levofloxacin, trovafloxacin, and moxifloxacin after single oral administration in healthy volunteers. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2000; 44: 2600–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Peloquin CA, Hadad DJ, Molino LP. et al. Population pharmacokinetics of levofloxacin, gatifloxacin, and moxifloxacin in adults with pulmonary tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2008; 52: 852–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nimmo WS, Peacock JE.. Effect of anaesthesia and surgery on pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Br Med Bull 1988; 44: 286–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wood M. Pharmacokinetic drug interactions in anaesthetic practice. Clin Pharmacokinet 1991; 21: 285–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Michot JM, Seral C, Van Bambeke F. et al. Influence of efflux transporters on the accumulation and efflux of four quinolones (ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, garenoxacin, and moxifloxacin) in J774 macrophages. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2005; 49: 2429–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hutschala D, Skhirtladze K, Kinstner C. et al. In vivo microdialysis to measure antibiotic penetration into soft tissue during cardiac surgery. Ann Thorac Surg 2007; 84: 1605–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. de Lange ECM, Recovery and calibration techniques: toward quantitative microdialysis In: Mueller M, ed. Microdialysis in Drug Development. New York, NY, USA: Springer, 2013; 13–33. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Grosset J. Mycobacterium tuberculosis in the extracellular compartment: an underestimated adversary. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2003; 47: 833–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Breilh D, Jougon J, Djabarouti S. et al. Diffusion of oral and intravenous 400 mg once-daily moxifloxacin into lung tissue at pharmacokinetic steady-state. J Chemother 2003; 15: 558–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gumbo T, Louie A, Deziel MR. et al. Selection of a moxifloxacin dose that suppresses drug resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis, by use of an in vitro pharmacodynamic infection model and mathematical modeling. J Infect Dis 2004; 190: 1642–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. National Kidney Foundation. Cockcroft-Gault Formula https://www.kidney.org/professionals/KDOQI/gfr_calculatorCoc.