Abstract

Background: Delivering health topics in schools through peer education is known to be beneficial for all students involved. In this study, we have evaluated a peer-education workshop that aims to educate primary and secondary school students on hygiene, the spread of infection and antibiotics.

Methods: Four schools in south-west England, in a range of localities, took part in peer-education workshops, with students completing before, after and knowledge-retention questionnaires. Mixed-effect logistic regression and mixed-effect linear regression were used to analyse the data. Data were analysed by topic, region and peer/non-peer-educator status. Qualitative interviews and focus groups with students and educators were conducted to assess changes in participants’ skills, confidence and behaviour.

Results: Qualitative data indicated improvements in peer-educator skills and behaviour, including confidence, team-working and communication. There was a significant improvement in knowledge for all topics covered in the intervention, although this varied by region. In the antibiotics topic, peer-educators’ knowledge increased in the retention questionnaire, whereas non-peer-educators’ knowledge decreased. Knowledge declined in the retention questionnaires for the other topics, although this was mostly not significant.

Conclusions: This study indicates that peer education is an effective way to educate young people on important topics around health and hygiene, and to concurrently improve communication skills. Its use should be encouraged across schools to help in the implementation of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance that recommends children are taught in an age-appropriate manner about hygiene and antibiotics.

Introduction

Antibiotic resistance has been a growing threat over the last few decades in all areas of the world,1 with an estimated 25 000 deaths in Europe each year caused by resistant bacteria.2 Prudent use of antibiotics can slow the emergence of resistance, yet a 2016 Eurobarometer survey showed that almost half of Europeans do not know that antibiotics are ineffective against viruses.3 Furthermore, only 56% of those surveyed correctly knew that antibiotics are ineffective against cold and flu.4 Education of the public in the correct use of antibiotics is a key strategy in the fight against antibiotic resistance.

Antibiotics are the most commonly prescribed medicine for children.5 Children are our future generation of antibiotic users and prescribers; therefore, targeting this group with educational strategies would likely have a long-term impact. Everyday hygiene, such as hand washing and covering sneezes with a tissue, can help reduce the spread of infection6 and therefore the need for antibiotics. Within this study we have used a comprehensive educational programme covering microbes, the spread of infection and treatment of infection to educate children on how to keep themselves healthy. Subsequently, through this programme we aim to reduce antibiotic use in young people.

Peer education is a popular learning tool, particularly in the field of health education. Studies have shown that peer-led strategies have a myriad of benefits for all those involved. For peer educators themselves, benefits include positive changes in attitudes, confidence, self-esteem, communication and knowledge.7–10 For those receiving the education from their peers, several studies have shown peer education to be more effective in improving knowledge and changing attitudes and behaviours than those of adult-led teaching programmes.11–13

e-Bug is an educational programme for classroom and home use that teaches children about microbes, the spread of infection and antibiotic use.14 Initially part-funded by DG SANCO of the European Commission, and now operated by PHE, e-Bug is an international project disseminating teaching resources to junior and senior schools across the world. The e-Bug resources are available in 23 different languages and have been proven to be effective in improving students’ knowledge.15 Furthermore, the e-Bug interactive science show has also been shown to improve knowledge in children and their parents.16 The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance on ‘Antimicrobial Stewardship – Changing Risk-Related Behaviours in the General Population’ recommends that all schools use e-Bug to teach about hygiene, the spread of infection and antibiotics.17

In this study we have adapted the e-Bug science show to create a peer-education workshop that was delivered and evaluated in schools across south-west England. This work has been a collaboration between PHE and the Forest of Dean District Council. Environmental health departments have a major role in protecting public health and in the education of the community. Environmental health officers already have relationships in place with their local schools, often visiting schools to promote good hygiene practice.

The aim of the e-Bug peer-education workshops was to provide young people with the knowledge and confidence to look after their own health. Our objectives are to evaluate the effectiveness of using peer education to improve young people’s knowledge about hygiene and antibiotic use. We will also assess the teacher and peer-educator attitudes to running the workshops in their schools.

Methods

School selection

The peer-education workshop evaluation was carried out in the academic year 2013–14 in three areas in south-west England. All secondary schools in these regions were approached via letter and e-mail, or through the county council’s Healthy Living and Learning schools programme. Four secondary schools—two rural, one in a small town and one inner city school—agreed to take part in the study. All secondary school students were Year 8, aged 12–13 years.

Participating secondary schools were responsible for recruitment of primary school classes who would be taught by the 12- to 13-year-olds on the second day of the workshop. These were local primary schools who fed into the secondary school. Students from these schools were in Year 5 or 6, aged 9–11 years. In the inner city school and one of the rural schools, the 12- to 13-year-olds also taught younger secondary school students in Year 7 (aged 11–12 years) from the same school. For the purpose of data analysis, and discussion in this paper, these students will be classed as primary school students. All schools participating in the study were state comprehensive schools.

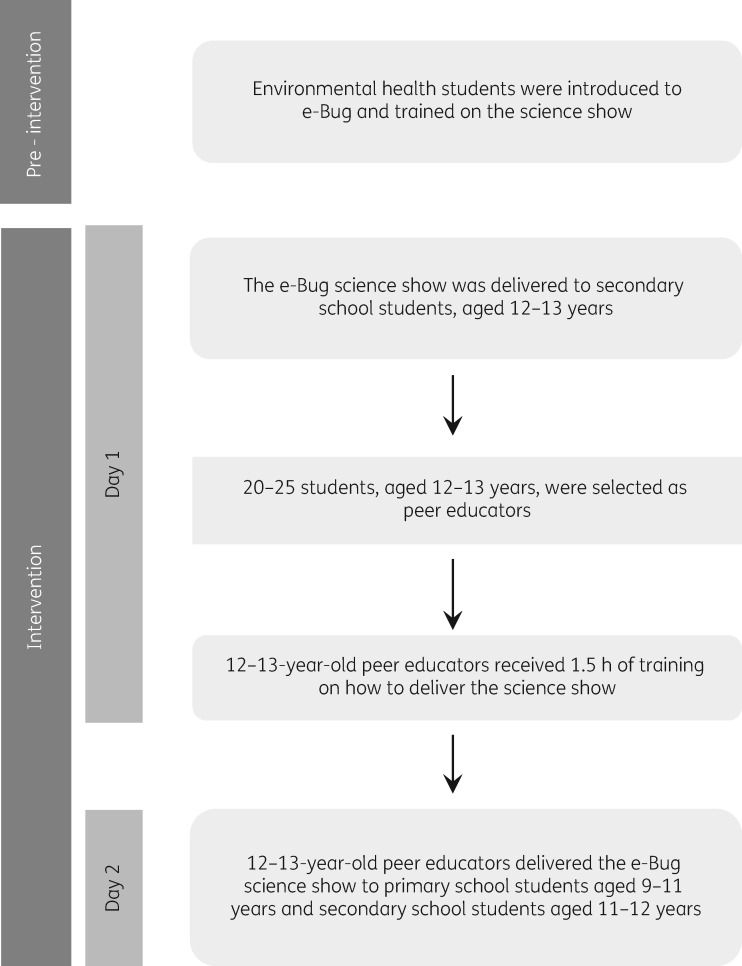

The intervention (Figure 1)

Figure 1.

The e-Bug peer education workshop.

Environmental health students were recruited to assist e-Bug staff during the workshop. Sixteen students were recruited through e-mails and advertisements distributed to universities across England. The project fulfilled the Public Health Intervention fields of their Portfolio of Professional Practice.

Prior to the workshop, environmental health students taking part in the project attended a training day to familiarize themselves with the e-Bug science show and learn more about the project. During this event, the interactive activities were demonstrated and the learning outcomes for each topic were covered. The science show consists of five interactive stands covering the topics of microbes, hand hygiene, respiratory hygiene, food hygiene and antibiotics. See Table 1 for a detailed description of the activities.

Table 1.

e-Bug interactive science show

| Stand | Learning outcomes | Activity |

|---|---|---|

| Microbe Mania | participants are taught about different types of microbes, how bacteria and viruses differ and where microbes can be found | using images of microbes, participants create model microbes in Petri dishes |

| Horrid Hands | participants learn how microbes spread through touch and when and how we should wash our hands | UV gel is used to show how easily microbes spread through touch; an activity with pepper and water demonstrates the importance of using soap |

| Super Sneezes | participants are taught how microbes spread through coughs and sneezes, and how this can be prevented by using a tissue | a spray gun with green food colouring (the ‘snot gun’) demonstrates how far microbes spread in a sneeze |

| Kitchen Mayhem | participants learn about microbes found in foods and how to prevent the spread of these microbes during food handling | participants make a chicken sandwich using a playdough chicken fillet coated in UV powder; the fluorescence shows how easily microbes spread during cooking |

| Antibiotic Awareness | participants are taught about antibiotics, antibiotic resistance and the importance of prudent antibiotic use | an acid/base colour change titration experiment shows the importance of finishing a course of antibiotics |

On day 1 of the intervention, e-Bug and environmental health staff delivered the e-Bug science show to participating students in the secondary schools. Students attended the workshop in groups of between 20 and 30. A short introduction was delivered before the students split into five groups and rotated around the interactive stands. Each had a large backing poster and an interactive activity to help teach the topic. Students spent ∼10 min on each stand.

After all participating students had received the science show, between 20 and 25 students of mixed ability were selected as peer educators by the school. During the second part of day 1, these peer educators were assigned a topic/stand and in groups of four or five were trained on how to deliver the e-Bug science show and the important learning points to cover. The training lasted for 1.5 h and a training booklet was provided to assist with learning.

On the second day of the intervention, the peer educators delivered their topic/stand to visiting primary school children. This took the same format as day 1, with students spending around 10 min on each stand. The peer educators were observed by e-Bug staff to ensure the correct educational messages were delivered.

Quantitative data collection and analysis

Before, after and knowledge-retention questionnaires were used to evaluate the effect of the intervention. Knowledge-retention questionnaires were completed 6 weeks post-intervention. Questionnaires were based on previous validated questionnaires used to evaluate the e-Bug resources.15,16 The questionnaire was split into five sections, representing the five topics covered. For primary school students, these were ‘true’ or ‘false’ questions, with a third option for ‘don’t know’. For secondary school students, the questions were multiple choice with four options given. The questionnaires are available as Supplementary data at JAC Online.

Questionnaires were coded and double entered into an EpiData 3.1 database by two researchers (V. L. Y. and A. C.). Each question and section was analysed separately by calculating the percentage of questions that were correctly answered. Students who had left any question blank were omitted from the analysis of that particular section. For the true/false or multiple choice questions, mixed-effect logistic regression was used to analyse the data, whereas mixed-effect linear regression was performed on the section percentages. These different models were used to take account of the different types of outcome variable: in the former case it was binary and in the latter case continuous, taking values between 0 and 100. Models consisted of main effects (region, questionnaire and, for senior schools, peer status) and interactions (two-way for junior schools and two-way and three-way for senior schools), which were subsequently removed if found not to be statistically significant. A likelihood ratio test (LRT) was used to ascertain statistical significance, with 5% being chosen as the significance level. Two-way interactions were used for junior schools to assess whether the degree of improvement and retention varied between regions, whereas three-way interactions were used for senior schools to determine whether this varied between regions and peers. All data manipulation and statistical analysis were performed in STATA version 13.1.

Qualitative data collection and analysis

Qualitative data were gathered to explore behaviour change among participants. Interviews were carried out post-intervention with teachers and focus groups of peer educators (three groups of four students) at two of the secondary schools (one rural and one town school). Teacher interviews and one student focus group were recorded and transcribed verbatim. The remaining focus groups were recorded through researcher notes. Consent from the teachers and parental consent for the students were obtained prior to interview.

Qualitative data were analysed using a modified framework analysis. Use of NVivo software (QSR International Pty Ltd, Melbourne, Australia) facilitated the organization of the data. Data were coded and refined in order to identify themes. Two researchers agreed on code categories and themes, the lead researcher coding all transcripts and a second researcher coding 17% of the data for reliability and quality assurance. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion between the researchers until agreement was reached.

Ethical considerations

Consent from an NHS Research Ethics Committee was not needed for this type of study as it does not involve NHS patients, staff or facilities. This is in accordance with the National Research Ethics Service guidelines, which characterize the study as ‘service evaluation’. Participants gave verbal consent to participate.

Results

Quantitative

Across the four secondary schools involved in the study, 1194 questionnaires were completed by 476 students (this included the before, after and retention questionnaires). In seven primary schools and three Year 7 groups, 1576 questionnaires were completed by 589 students.

Pre-knowledge of the topics differed between regions. In primary schools, four out of the five topics had the highest pre-knowledge in the inner city school, with the lowest pre-knowledge occurring for all topics in the rural schools. The hand hygiene topic had the highest pre-knowledge amongst both primary and secondary schools, with antibiotics having the lowest. This was consistent across all areas.

A significant improvement in knowledge for each topic was observed in both primary (Table 2) and secondary (Table 3) school students. This improvement, however, did vary between areas. For all topics for primary students, and most topics for secondary students, the knowledge improvement was greatest in the rural schools and lowest in the inner city school.

Table 2.

Percentage change in knowledge for primary school students, by questionnaire section

| Before teaching, % correct | Before teaching change, % (95% CI) | After teaching change, % (95% CI) | Retention change, % (95% CI) | P value for interaction | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microbe Mania | <0.001 | ||||

| rural | 52.2 | 0.0 | 24.1 (20.8, 27.4) | 24.7 (21.3, 28.1) | |

| inner city | 71.3 | 19.5 (13.5, 25.5) | 24.6 (19.0, 30.2) | 28.5 (22.7, 34.3) | |

| town | 67.8 | 15.8 (10.4, 21.2) | 26.7 (21.2, 32.1) | 29.2 (22.8, 35.6) | |

| Horrid Hands | 0.002 | ||||

| rural | 72.2 | 0.0 | 10.2 (7.3, 13.2) | 12.4 (9.3, 15.4) | |

| inner city | 80.0 | 8.4 (3.3, 13.6) | 11.6 (6.7, 16.5) | 9.5 (4.4, 14.7) | |

| town | 76.6 | 4.2 (−0.5, 9.0) | 10.3 (5.5, 15.1) | 8.7 (3.0, 14.3) | |

| Super Sneezes | <0.001 | ||||

| rural | 61.3 | 0.0 | 26.3 (22.9, 29.6) | 24.6 (21.2, 28.0) | |

| inner city | 73.7 | 11.6 (6.2, 17.0) | 23.5 (18.5, 28.4) | 20.5 (15.1, 25.8) | |

| town | 68.0 | 6.6 (1.7, 11.5) | 28.1 (23.1, 33.1) | 24.4 (18.2, 30.5) | |

| Kitchen Mayhem | 0.02 | ||||

| rural | 61.3 | 0.0 | 11.9 (8.8, 15.0) | 15.2 (12.0, 18.4) | |

| inner city | 64.9 | 3.9 (−1.6, 9.3) | 9.9 (4.8, 14.9) | 10.5 (5.2, 15.9) | |

| town | 67.5 | 6.4 (1.4, 11.4) | 20.4 (15.3, 25.4) | 15.6 (9.7, 21.4) | |

| Antibiotic Awareness | <0.001 | ||||

| rural | 26.2 | 0.0 | 22.9 (19.6, 26.2) | 11.2 (7.8, 14.5) | |

| inner city | 43.5 | 15.6 (10.2, 21.0) | 20.7 (15.7, 25.7) | 19.8 (14.3, 25.3) | |

| town | 30.7 | 4.3 (−1.0, 9.6) | 17.0 (11.7, 22.3) | 11.5 (5.4, 17.6) |

Percentages given are absolute percentage changes from the baseline before teaching change (0.0).

Table 3.

Percentage change in knowledge for secondary school students, by questionnaire section

| Before teaching, % correct | Before teaching change, % (95% CI) | After teaching change, % (95% CI) | Retention change, % (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microbe Mania | <0.001a | ||||

| peers | |||||

| rural | 64.0 | −2.7 (−10.1, 4.7) | 22.5 (15.0, 29.9) | 9.4 (1.3, 17.4) | |

| inner city | 79.4 | 15.0 (4.1, 25.9) | 32.6 (22.2, 43.0) | 23.7 (8.8, 38.7) | |

| town | 70.0 | 4.6 (−5.5, 14.8) | 22.6 (10.8, 34.3) | −0.7 (−11.6, 10.1) | |

| non-peers | |||||

| rural | 65.8 | 0.0 | 19.8 (16.3, 23.3) | 11.8 (8.0, 15.5) | |

| inner city | 68.7 | 3.2 (−2.4, 8.9) | 13.0 (7.0, 19.1) | 0.8 (−5.4, 6.9) | |

| town | 68.9 | 3.7 (−3.0, 10.3) | 4.7 (−2.5, 11.8) | 9.2 (1.9, 16.4) | |

| Horrid Hands | 0.01a | ||||

| peers | |||||

| rural | 75.0 | 1.9 (−7.1, 11.0) | 4.5 (−4.5, 13.5) | 15.5 (6.1, 25.0) | |

| inner city | 81.9 | 10.4 (−2.2, 23.0) | 13.3 (0.8, 25.8) | 16.9 (0.7, 33.2) | |

| town | 67.5 | −3.8 (−15.9, 8.4) | 2.9 (−10.3, 16.1) | −2.0 (−14.8, 10.7) | |

| non-peers | |||||

| rural | 71.4 | 0.0 | 2.3 (−1.0, 5.7) | 9.8 (6.1, 13.5) | |

| inner city | 64.1 | −8.9 (−15.6, −2.2) | −6.7 (−13.7, 0.3) | −1.5 (−8.7, 5.7) | |

| town | 69.0 | −2.3 (−10.2, 5.5) | 5.4 (−3.1, 14.0) | −0.8 (−9.3, 7.7) | |

| Super Sneezes | 0.01a | ||||

| peers | |||||

| rural | 58.3 | −2.8 (−10.3, 4.8) | 22.3 (14.8, 29.8) | 22.8 (14.5, 30.9) | |

| inner city | 67.2 | 8.0 (−3.2, 19.1) | 32.5 (21.8, 43.2) | 29.0 (14.2, 43.8) | |

| town | 58.3 | −0.7 (−11.4, 10.0) | 19.7 (8.2, 31.1) | 12.9 (2.2, 23.6) | |

| non-peers | |||||

| rural | 60.6 | 0.0 | 16.2 (12.8, 19.6) | 18.8 (15.2, 22.4) | |

| inner city | 60.4 | −0.5 (−6.2, 5.2) | 11.0 (4.8, 17.1) | 9.4 (2.9, 15.8) | |

| town | 58.5 | −1.0 (−7.6, 5.7) | 18.3 (11.0, 25.7) | 8.6 (1.3, 15.9) | |

| Kitchen mayhem | 63.5 | 0.0 | 12.4 (9.8, 14.9) | 12.4 (9.6, 15.1) | <0.001b |

| Antibiotic Awareness | <0.001a | ||||

| peers | |||||

| rural | 30.6 | −5.7 (−14.6, 13.2) | 23.0 (14.2, 31.9) | 36.8 (27.3, 46.3) | |

| inner city | 51.5 | 16.1 (3.2, 29.0) | 40.4 (28.0, 52.7) | 44.3 (26.6, 62.0) | |

| town | 32.9 | −2.1 (−14.5, 10.2) | 18.4 (4.4, 32.3) | 20.3 (7.6, 32.9) | |

| non-peers | |||||

| rural | 37.0 | 0.0 | 25.1 (20.9, 29.3) | 23.4 (18.9, 28.0) | |

| inner city | 39.4 | 1.8 (−5.2, 8.6) | 17.0 (9.8, 24.2) | 13.4 (5.9, 20.9) | |

| town | 37.0 | 0.3 (−7.7, 8.4) | 13.7 (4.9, 22.4) | 10.8 (2.2, 19.4) |

Percentages given are absolute percentage changes from the baseline before teaching change (0.0).

Kitchen Mayhem showed no significant difference between region or peer/non-peer.

P value for interaction.

P value for teaching change.

The retention questionnaires for all schools showed a decline in knowledge from immediately post-intervention for most topics; however, this was mostly not significant. Students’ knowledge 6 weeks post-intervention was still higher than before the workshop, showing the students had learnt and retained knowledge through the intervention. Significant decline in knowledge did occur in the antibiotic topics in the primary rural schools; however, this was not replicated in the other regions and it was not replicated in the secondary schools. In some regions and topics, knowledge in the retention questionnaire actually increased, e.g. the primary town and inner city schools for the Microbe Mania topic.

Peer educators did not have a higher baseline knowledge compared with non-peer educators and there was not any notable difference in peer/non-peer knowledge change in the after questionnaire. However, for some topics, peer educators demonstrated a higher level of knowledge retention compared with non-peers. This is particularly evident in the antibiotics topic, where peer-educators’ knowledge actually increased in all regions and non-peer-educators’ knowledge decreased.

A full breakdown of improvement scores for individual questions is available in the Supplementary data. Closer examination of each individual antibiotic question show that although a significant improvement in knowledge was observed for most questions post-intervention, some questions, such as ‘Bacteria are becoming resistant to antibiotics’ for primary students, had a low retention of knowledge across all regions. In addition, for the secondary students’ antibiotic questions, only the question ‘To treat coughs and colds we should rest and take fluids’ showed a significant difference between peer educators and non-peer educators in their knowledge retention.

Qualitative

Five main themes emerged during the teacher interviews: reasons for running the intervention; planning and organization of the intervention; future of the intervention; student knowledge gain; and student behaviour change. Reasons for running the intervention included the benefits and opportunities for their students; to develop links and relationships with local primary schools; and to raise the profile of science and awareness of the topics covered. Teachers also discussed the opportunity for education to be taken back to families.

‘I think that there’s that opportunity to give that education and then take it back to the families and their communities’

Teachers discussed the practical aspects of planning and organizing the intervention and spoke positively about working with outside organizations such as local environmental health scientists.

‘And it’s really, it was really good with, working with outside agencies as well, so that they see that science is more than just what we teach them in the classroom’

Teachers commented that peer educators gained a range of skills during the intervention, such as confidence, self-esteem and focus, as well as knowledge gain in the topics covered. Teachers noted that peer-educator behaviour changed during the event and that normally quiet and reserved students performed remarkably well during the teaching of their peers.

‘Yeah, yeah they, obviously their behaviour was, in terms of class behaviour was, they were brilliant, represented the school amazingly, but their confidence just grew throughout the day, completely, and yeah, it was incredible really.’

Since the workshop, one teacher noted a change in behaviour in the peer educators, describing them as more responsive to learning.

‘I think they are, I think they’re more responsive to some of their learning, when we’ve done some feedback with them since, and yourself, and we, they were all willing, more or less, to open up and be honest and tell about their experience. And yeah, I think that many of them have, it’s given them an opportunity and I think that there’s definitely, whether it’s small steps in some, I think there’s a better behaviour, better focus and generally they’re, they’ve improved, some of them, in their skills.’

All schools who took part were keen to repeat the intervention at their school and teachers made practical suggestions for improvements such as ensuring an appropriate location and running the workshop at end of the academic year when schools have more availability.

Four themes emerged from the student focus groups: expectations prior to the intervention; knowledge and behaviour change; teaching others; and planning and running the event. Peer educators expressed feelings of both excitement and nerves prior to the workshops, but all said that they enjoyed the event, in particular teaching others. When asked what they had learnt from the workshops, students commented on confidence, how to teach and team working.

‘It helps with teamwork because if you’re saying things together you need to know when you’re saying it and that helps’

Some students said they were more likely to wash their hands now and several students also taught members of their family at home.

‘I told my mum to wash her hands after she was working outside but I don’t think she did.’

Discussion

The knowledge questionnaires confirm that the peer-education workshop was effective at changing knowledge around hygiene, infection and antibiotic topics. Furthermore, qualitative data suggest that peer educators gained confidence and communication skills through the workshops and that peer educators demonstrated behaviour change since the event. Knowledge improvement was seen for most topics, although this varied across the different regions and there are areas where further improvements could be made. Differences between regions could be accounted for by the implementation of the workshop. The four workshops were each delivered at a different point in the school year, meaning some topics may have already been covered in lessons and by different e-Bug and environmental health staff with a range of backgrounds and expertise. The greatest knowledge improvement was seen in the rural schools, although these schools had the lowest baseline knowledge and therefore a greater capacity for improvement.

The antibiotics topic had the lowest pre-workshop knowledge for all schools, perhaps because it had not been covered in the school curriculum. The data from these workshops show not only that students’ knowledge of antibiotics improved, but also that this knowledge was retained for at least 6 weeks. Retention of knowledge was generally better for the peer educators, compared with non-peer educators, and this is particularly evident in the antibiotics topic, where in one question knowledge actually increased in the retention data for the peer educators. This greater retention of data suggests the workshops had a greater benefit for those who acted as peer educators. Furthermore, the data show that these workshops are an effective way to teach young people about antibiotics.

Other work in this area

The majority of published peer-led education studies have focused around sexual health,18 HIV prevention19 and smoking.12,20 Other health behaviours have also been addressed through peer education, such as asthma21 and healthy eating.22 There have been a limited number of studies using peer-led teaching to address the issues of infection and antibiotic use. In 1998, Early et al.23 used school-based peer education to increase the frequency of hand washing among children. A significant increase in hand washing was seen after the study and, if combined with accessible and convenient hand hygiene facilities, this increase remained 6 weeks post-intervention. In addition, a study by Cebotarenco and Bush24 in 2008 used peer education to reduce the use of antibiotics for colds and flu within a region in Moldova. Students and their parents were both involved in this study and the intervention was shown to be successful through self-reporting for antibiotic use.

Strengths of the intervention

The intervention in this study used both primary and secondary schools, with secondary schools using the workshop as an opportunity to increase recruitment of primary school students. However, this intervention is transferable and can be adapted to suit other educational needs. For example, the workshop could be run in just one school, with either students in higher year groups teaching younger students or students of the same age teaching each other. In addition, using an interactive science show format, rather than a standard lesson, allows staff to pick and choose topics and activities to suit their lesson or group’s ability. Activities such as the respiratory hygiene ‘snot gun’ demonstration lend themselves well to assemblies, science or health fairs and other formats where time is restricted.

Furthermore, by educating children and providing take-home materials, we can also access parents and other family members. Therefore, the reach of this intervention is wider than just the students who participated.

Limitations

Despite the success of this workshop, there are limitations. In the current format, a considerable time commitment is required from the secondary school. Students who receive the science show only miss one normal lesson and, given the science show covers topics in the national curriculum, this is unlikely to have an impact. Those acting as peer educators miss almost 2 full days; however, given the wider benefits for these students, some schools may consider this to be justified. Further work could be done to see whether the workshops can be condensed and run successfully in a shorter time frame. Furthermore, several members of staff are required to run the event as one member of staff is required on each topic/stand. It may be that a greater number of schools would run the workshops if it was feasible for schools to host the event independently of e-Bug or environmental health staff, perhaps using other initial educators such as further- or higher-education students. The science show activities are designed to be run on a small budget, with less than £200 needed to set up and run the event with multiple schools. Finally, further work could be carried out to see whether the resulting knowledge change is sustained over a longer period of time. In addition, if follow-up sessions were to be performed it may be possible to investigate changes in behaviour around hygiene and antibiotics, as well as knowledge.

Future work

Upon completion of this evaluation, a peer-education resource pack was developed, outlining how schools can set up and run the intervention. This pack is available for educators to download on the e-Bug web site (www.e-bug.eu). Future work will revolve around seeking endorsement for the pack from public and environmental health bodies and in promotion through these organizations. In addition, we will continue to gather information from educators on how the intervention can be adapted to better suit their needs.

Conclusions

Overall, the e-Bug peer-education workshop has been shown to successfully improve young people’s knowledge on antibiotics, hygiene and the spread of infection. These workshops should be encouraged within schools of all regions, due to the benefits for all involved. Not only does the intervention improve knowledge, confidence and behaviour in young people, but it also educates the next generation of antibiotic users on the importance of prudent antibiotic use.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all schools who took part in the intervention and all environmental health students who contributed to the running of the workshops. In addition, we would like to thank Beverley Hoekstra for assisting with the workshops.

Funding

This work was supported by Public Health England and the British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy.

Transparency declarations

None to declare.

Supplementary data

The questionnaires and a full breakdown of the individual questions are available as Supplementary data at JAC Online (http://jac.oxfordjournals.org/).

References

- 1. WHO. Antimicrobial Resistance: Global Report on Surveillance, 2014. http://www.who.int/drugresistance/documents/surveillancereport/en/.

- 2. ECDC. Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance in Europe, Annual Report of the European Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance Network (EARS-Net), 2014. http://ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications/publications/antimicrobial-resistance-europe-2014.pdf.

- 3. European Union. Special Eurobarometer 445, Antimicrobial Resistance, 2016. http://ec.europa.eu/dgs/health_food-safety/amr/docs/eb445_amr_generalreport_en.pdf.

- 4. Eurosurveillance Editorial Team. Special Eurobarometer: use of antibiotics declining in the European Union but much work still needed. Euro Surveill 2013; 18: pii=20641. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Spyridis N, Sharland M.. The European Union Antibiotic Awareness Day: the paediatric perspective. Arch Dis Child 2008; 93: 909–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Little P, Stuart B, Hobbs FD. et al. An internet-delivered handwashing intervention to modify influenza-like illness and respiratory infection transmission (PRIMIT): a primary care randomised trial. Lancet 2015; 386: 1631–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ochieng BM. Adolescent health promotion: the value of being a peer leader in a health education/promotion peer education programme. Health Educ J 2003; 62: 61–72. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Strange V, Forrest S, Oakley A. et al. Peer-led sex education—characteristics of peer educators and their perceptions of the impact on them of participation in a peer education programme. Health Educ Res 2002; 17: 327–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Backett-Milburn K, Wilson S.. Understanding peer education: insights from a process evaluation. Health Educ Res 2000; 15: 85–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Turner G. Peer support and young people's health. J Adolesc 1999; 22: 567–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tobler NS. Drug prevention programs can work: research findings. J Addict Dis 1992; 11: 1–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ayaz S, Acil D.. Comparison of peer education and the classic training method for school aged children regarding smoking and its dangers. J Pediatr Nurs 2015; 30: e3–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mellanby AR, Newcombe RG, Rees J. et al. A comparative study of peer-led and adult-led school sex education. Health Educ Res 2001; 16: 481–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. McNulty CA, Lecky DM, Farrell D. et al. Overview of e-Bug: an antibiotic and hygiene educational resource for schools. J Antimicrob Chemother 2011; 66 Suppl 5: v3–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lecky DM, McNulty CA, Touboul P. et al. Evaluation of e-Bug, an educational pack, teaching about prudent antibiotic use and hygiene, in the Czech Republic, France and England. J Antimicrob Chemother 2010; 65: 2674–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lecky DM, Hawking MK, Verlander NQ. et al. Using interactive family science shows to improve public knowledge on antibiotic resistance: does it work? PLoS One 2014; 9: e104556.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Antimicrobial Stewardship—Changing Risk-Related Behaviours in the General Population 2016. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/indevelopment/gid-phg89/documents.

- 18. Layzer C, Rosapep L, Barr S.. A peer education program: delivering highly reliable sexual health promotion messages in schools. J Adolesc Health 2014; 54 Suppl 3: S70–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Borgia P, Marinacci C, Schifano P. et al. Is peer education the best approach for HIV prevention in schools? Findings from a randomized controlled trial. J Adolesc Health 2005; 36: 508–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Campbell R, Starkey F, Holliday J. et al. An informal school-based peer-led intervention for smoking prevention in adolescence (ASSIST): a cluster randomised trial. Lancet 2008; 371: 1595–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Shah S, Peat JK, Mazurski EJ. et al. Effect of peer led programme for asthma education in adolescents: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2001; 322: 583–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Forneris T, Fries E, Meyer A. et al. Results of a rural school-based peer-led intervention for youth: goals for health. J Sch Health 2010; 80: 57–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Early E, Battle K, Cantwell E. et al. Effect of several interventions on the frequency of handwashing among elementary public school children. Am J Infect Control 1998; 26: 263–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cebotarenco N, Bush PJ.. Reducing antibiotics for colds and flu: a student-taught program. Health Educ Res 2008; 23: 146–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.