Abstract

Background

Atovaquone/proguanil, registered as Malarone®, is a fixed-dose combination recommended for first-line treatment of uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria in non-endemic countries and its prevention in travellers. Mutations in the cytochrome bc1 complex are causally associated with atovaquone resistance.

Methods

This systematic review assesses the clinical efficacy of atovaquone/proguanil treatment of uncomplicated malaria and examines the extent to which codon 268 mutation in cytochrome b influences treatment failure and recrudescence based on published information.

Results

Data suggest that atovaquone/proguanil treatment efficacy is 89%–98% for P. falciparum malaria (from 27 studies including between 18 and 253 patients in each case) and 20%–26% for Plasmodium vivax malaria (from 1 study including 25 patients). The in vitro P. falciparum phenotype of atovaquone resistance is an IC50 value >28 nM. Case report analyses predict that recrudescence in a patient presenting with parasites carrying cytochrome b codon 268 mutation will occur on average at day 29 (95% CI: 22, 35), 19 (95% CI: 7, 30) days longer than if the mutation is absent.

Conclusions

Evidence suggests atovaquone/proguanil treatment for P. falciparum malaria is effective. Late treatment failure is likely to be associated with a codon 268 mutation in cytochrome b, though recent evidence from animal models suggests these mutations may not spread within the population. However, early treatment failure is likely to arise through alternative mechanisms, requiring further investigation.

Introduction

Infection with Plasmodium spp. is a major cause of mortality worldwide, causing 235 000–639 000 deaths in 2015 and 148 000 000–304 000 000 clinical cases of malaria. Most cases are in endemic countries, although malaria is also one of the most frequent causes of morbidity in travellers returning to non-endemic countries. Atovaquone/proguanil (Malarone®) is a fixed-dose combination often used as a first-line treatment for uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum infections in non-endemic countries.1,2 It has been used on a large scale as a treatment in areas where treatment failures of artemisinin combination therapies (TFACT)3 are problematic.4 It is now considered a first-line prophylaxis against malaria for travellers5 and particularly military personnel whose experience of adverse events with mefloquine prophylaxis is becoming increasingly recognized.6 Atovaquone/proguanil is also being studied in a new chemo-vaccination strategy where individuals are exposed to P. falciparum sporozoites and then take atovaquone/proguanil to treat pre-symptomatic infections and generate antimalarial immunity (P. G. Kremsner, unpublished). Taken together with the recent expiry of patent protection for Malarone®, usage of atovaquone/proguanil is likely to rise in the future.

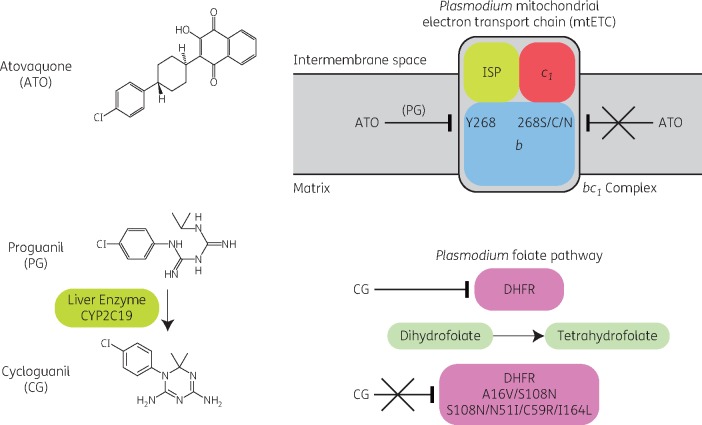

Atovaquone is a hydroxynaphthoquinone that selectively inhibits the mitochondrial electron transport chain at the cytochrome bc1 complex of malaria parasites (Figure 1).7 This mechanism of antiparasitic activity is complemented by the individual actions of proguanil and its metabolite, cycloguanil (Figure 1). Proguanil itself has no direct effects on the parasite, but it enhances atovaquone’s ability to collapse the membrane potential of malaria parasites by sensitizing mitochondria to atovaquone.8 Proguanil is converted into cycloguanil by the hepatic CYP2C19 system and cycloguanil inhibits parasite dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR), which is essential for folate production and parasite replication.9

Figure 1.

Mechanisms of action and resistance to atovaquone/proguanil. Structures of atovaquone, proguanil and cycloguanil are shown. Atovaquone targets cytochrome b in the bc1 complex [formed by cytochromes b and c1 and the Rieske iron–sulphur protein (ISP)] of the Plasmodium mitochondrial electron transport chain. The mitochondrial electron transport chain is located on the inner membrane of mitochondria, separating the intermembrane space (the space between the outer and inner membranes) from the centrally located matrix. Atovaquone works in synergy with proguanil, but its activity is reduced by mutations in cytochrome b (and in particular Y268S/C/N). Proguanil is metabolized to cycloguanil by the liver enzyme CYP2C19. Cycloguanil targets the enzyme DHFR in the Plasmodium folate pathway. Activity of cycloguanil is reduced by mutations in DHFR, including A16V/S108N and S108N/N51I/C59R/I164L. This figure appears in colour in the online version of JAC and in black and white in the print version of JAC.

Several mechanisms can potentially influence the efficacy of atovaquone/proguanil for treatment. Mutations in P. falciparum cytochrome b (PfCYTb) (in particular leading to Y268S/C/N) cause atovaquone resistance both in vitro and in vivo.10–12 Interestingly, a recent report, using a rodent model of malaria infection, describes that mutations in Plasmodium berghei CYTb are lethal during transmission of the parasite in the mosquito vector.13 This suggests that these mutations may not be able to spread within a population, although this hypothesis has yet to be demonstrated for P. falciparum in the field. Cycloguanil resistance in parasites is conferred by multiple mutations in DHFR. Polymorphisms in host CYP2C19 also affect proguanil metabolism and can lower cycloguanil concentrations.14

Reports of frequencies of treatment failure associated with atovaquone/proguanil vary, although the risk of failure has not been systematically examined particularly with respect to mutations at codon 268 of PfCYTb. In this systematic review, we examine all original in vivo data where atovaquone/proguanil was used exclusively to treat malaria and relate findings on risk of recrudescence to mutations in PfCYTb and available results from in vitro assays. We also estimate clinical efficacy of atovaquone/proguanil treatment of uncomplicated malaria. Results may impact on existing guidelines for the treatment of uncomplicated malaria.

Methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

This systematic review was registered at PROSPERO (number CRD42015020757) on 25 February 2015 and updated on 13 October 2017.

PubMed (1966–present) and ScienceDirect (1823–present) were interrogated on the 19 May 2015 with the following search strategy {[(Atovaquone AND Proguanil) OR (Malarone)] AND (falciparum OR vivax OR ovale OR malariae OR knowlesi)}. Records were assessed for eligibility using title, or title and abstract. Eligible records were screened for duplicates and full-text obtained for the remaining records that were then reassessed for eligibility. Data were extracted from these articles by two reviewers and tabulated. Inclusion and exclusion criteria and extracted data variables are summarized in the Supplementary Methods (available as Supplementary data at JAC Online).

Group studies

Two reviewers assessed group study eligibility and the risk of bias in the trials using the modified Cochrane risk of bias tool.15 Six domains of bias were assessed with regard to selection, performance, detection, attrition, reporting and other, and the risk of bias deemed as low, medium, high or unclear. The information was not used to exclude studies from this review, but the assessment fed into the interpretation of results.

For all group studies, the total numbers of patients enrolled into each treatment arm, those followed up to 28 days and those with treatment failure or recrudescence were extracted and combined to obtain the proportion of patients for whom treatment had been successful in the ITT and PP populations. For randomized controlled trials (RCT), this information was also extracted for the comparator antimalarial arm(s) to allow meta-analyses (pooled ORs of the alternative intervention versus atovaquone/proguanil).

A random effects model to derive a pooled OR of treatment success for atovaquone/proguanil versus comparator treatments, if appropriate, was applied and interpreted in conjunction with a corresponding heterogeneity χ2 test and additional sensitivity analyses undertaken (Supplementary Methods). Data were analysed with Stata version 14, with forest plots generated in Review Manager version 5.3.

In vitro/ex vivo studies

For in vitro/ex vivo studies, no mathematical synthesis was carried out.

Case reports

Preliminary exploratory analyses examined all the variables using graphs and statistical tests for comparisons according to the nature of the data. Regression techniques were implemented to understand potential associations between pretreatment parasitaemia and (i) minimum days to recrudescence (defined as the length of time in days since treatment to the occurrence of clinical signs or parasitological diagnosis, whichever came first), and (ii) parasitaemia at recrudescence with presence of mutation in PfCYTb codon 268 in both cases (Supplementary Methods).

Results

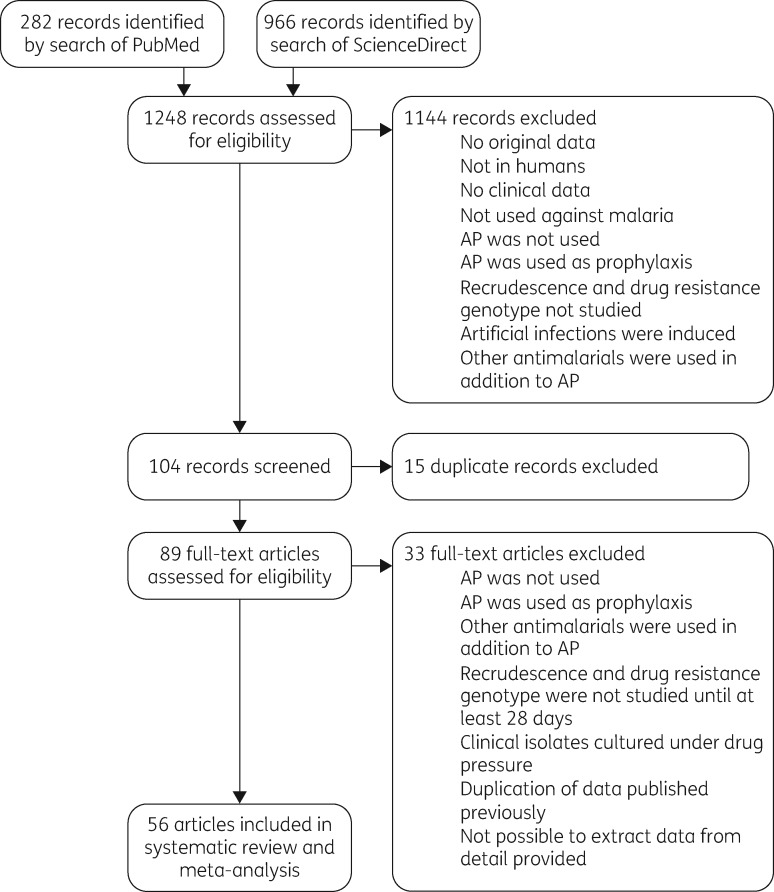

A total of 282 records were returned using PubMed and 966 using ScienceDirect (Figure 2). The 1248 records were assessed for eligibility, using title, or title and abstract, and 1144 records were excluded at this point, as they did not meet the inclusion criteria. Of the remaining 104 records, 15 duplicate records were excluded. Full text was obtained for the remaining 89 records and assessed for eligibility. Of these, 33 were excluded as they did not meet the inclusion criteria. Thus, 56 articles met the inclusion criteria for this systematic review; within these, 20 included case reports, 29 included group studies and 15 included in vitro/ex vivo data. The case reports and group studies were included in the meta-analysis.

Figure 2.

Study selection. AP, atovaquone/proguanil.

The 29 group studies (Table 1) consisted of 27 with eligible data for atovaquone/proguanil treatment of P. falciparum infection and single studies with eligible data for atovaquone/proguanil treatment of Plasmodium vivax infection and Plasmodium ovale spp. and Plasmodium malariae infection. Together, the 27 P. falciparum studies began with 1960 patients, of whom 1695 were treated and followed up to 28 days (86.5%). A total of 1640 patients were successfully treated up to 28 days, 83.7% of the 1960 original patients and 96.8% of the 1695 treated and followed-up patients. The one P. vivax study began with 25 patients, of whom 19 were treated and followed up to 28 days (76%). Five patients were successfully treated up to 28 days, 20% of the original 25 patients, and 26.3% of the treated and followed up patients. The one study of P. ovale spp. and P. malariae began with six patients and all were successfully treated up to 28 days.

Table 1.

Characteristics of group studies

| Paper | Species of Plasmodium | Country of infection | Country of diagnosis/ treatment | Period of study | Type of study | Number of patients with ITT with atovaquone/ proguanil | Number of patients assessed at day 28 | Number of patients cured at day 28 | Percentage attendance | Percentage treatment success (ITT population) | Percentage treatment success (PP population) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anabwani et al. 199930 | P. falciparum | Kenya | Kenya | 1994 | RCT | 84 | 81 | 76 | 96.4 | 90.5 | 93.8 |

| Borrmann et al. 200331 | P. falciparum | Gabon | Gabon | 1999–2000 | RCT | 100 | 92 | 87 | 92 | 87 | 94.6 |

| Bouchard et al. 200032 | P. falciparum | Worldwide | France | 1994–95 | RCT | 25 | 21 | 21 | 84 | 84 | 100 |

| Bustos et al. 199933a | P. falciparum | Philippines | Philippines | 1994–95 | RCT | 55 | 54 | 54 | 98 | 98.2 | 100 |

| Carrasquilla et al. 201217 | P. falciparum | Columbia | Columbia | 2007–08 | RCT | 53 | 53 | 52 | 100 | 98.1 | 98.1 |

| de Alencar et al. 199734 | P. falciparum | Brazil | Brazil | 1995–96 | RCT | 88 | 73 | 72 | 83 | 81.8 | 98.6 |

| Gürkov et al. 200835 | P. falciparum | Ethiopia | Ethiopia | 2006 | RCT | 32 | 30 | 28 | 93.8 | 87.5 | 93.3 |

| Giao et al. 200436 | P. falciparum | Vietnam | Vietnam | 2001–02 | RCT | 81 | 77 | 73 | 95.1 | 90.1 | 94.8 |

| Llanos-Cuentas et al. 200137 | P. falciparum | Peru | Peru | 1995–96 | RCT | 20 | 19 | 19 | 95 | 95 | 100 |

| Looareesuwan et al. 199938 | P. falciparum | Thailand | Thailand | 1993–94 | RCT | 91 | 79 | 79 | 86.8 | 86.8 | 100 |

| Mulenga et al. 199939 | P. falciparum | Zambia | Zambia | 1993–94 | RCT | 82 | 80 | 80 | 97.6 | 97.6 | 100 |

| Mulenga et al. 200621 | P. falciparum | Zambia | Zambia | 2000–02 | RCT | 128 | 97 | 92 | 75.8 | 71.9 | 94.8 |

| Radloff et al. 199640 | P. falciparum | Gabon | Gabon | 1994–95 | RCT | 71 | 63 | 62 | 88.7 | 87.3 | 98.4 |

| Tahar et al. 201441 | P. falciparum | Cameroon | Cameroon | 2008–09 | RCT | 168 | 156 | 140 | 92.9 | 83.3 | 89.7 |

| total RCT | 1078 | 975 | 935 | ||||||||

| weighted average (95% CI)b | 92.5 (88.4, 95.8) | 89.2 (84.7, 93) | 97.6 (95.4, 99.2) | ||||||||

| Blonde et al. 200742 | P. falciparum | Africa | France | 2004–05 | Obs | 48 | 15d | 15 | 31.3 | 31.3 | 100 |

| Boggild et al. 200943 | P. falciparum | Thailand | Thailand | 2004–05 | Obsc | 70 | 68 | 67 | 97.1 | 95.7 | 98.5 |

| Bouchard et al. 201244 | P. falciparum | Worldwide | Europe | 2003–09 | Obs | 253 | 194 | 191 | 76.7 | 75.5 | 98.5 |

| Chih et al. 200645 | P. falciparum | Africa | Australia | 2003–05 | Obs | 52 | 19d | 19 | 36.5 | 36.5 | 100 |

| Gay et al. 199746 | P. falciparum | Worldwide | Philippines France | 1993–95 | Obsc | 18 | 18 | 18 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Grynberg et al. 201547 | P. falciparum | Worldwide | Israel | 2001–13 | Obs | 44 | 44 | 38 | 100 | 86.4 | 86.4 |

| Krudsood et al. 200748 | P. falciparum | Thailand | Thailand | 2004–05 | Obs | 140 | 137 | 134 | 97.9 | 95.7 | 97.8 |

| Lacy et al. 200249 | P. falciparum | Indonesia | Indonesia | 1999–2000 | Obs | 19 | 19 | 18 | 100 | 94.7 | 94.7 |

| Malvy et al. 200250 | P. falciparum | Worldwide | France | 1999–2001 | Obs | 112 | 112 | 112 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Na-Bangchang et al. 200551 | P. falciparum | Thailand Zambia | Thailand Zambia | 2000–01 | Obs | 26 | 22 | 22 | 84.6 | 84.6 | 100 |

| Sabchareon et al. 199852 | P. falciparum | Thailand | Thailand | 1994–95 | Obs | 32 | 26 | 26 | 81.3 | 81.3 | 100 |

| Tahar et al. 201353 | P. falciparum | Cameroon | Cameroon | 2008–09 | Obs | 18 | 18 | 17 | 100 | 94.4 | 94.4 |

| Thybo et al. 200454 | P. falciparum | Africa | Denmark | 1999–2000 | Obs | 50 | 28 | 28 | 56 | 56 | 100 |

| total Obs | 882 | 720 | 705 | ||||||||

| weighted average (95% CI)b | 87.6 (73.8, 97.1) | 83.4 (69.7, 93.8) | 99.1 (97.4, 99.97) | ||||||||

| Looareesuwan et al. 199655 | P. vivax | Thailand | Thailand | 1990–93 | Obs | 25 | 19 | 5 | 76 | 20 | 26.3 |

| Radloff et al. 199656 | P. ovale spp. | Gabon | Gabon | 1995 | Obs | 3 | 3 | 3 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| P. malariae | 3 | 3 | 3 | 100 | 100 | 100 | |||||

Obs, observational study.

Atovaquone/proguanil data from this paper are included in the RCT section, but further analysis including data for the comparator antimalarial treatments was not undertaken for the following reason. Participants were originally randomized to atovaquone/proguanil and chloroquine, but a low cure rate for the latter resulted in a protocol amendment to include sulfadoxine/pyrimethamine. However, at the time of this change, participants in the atovaquone/proguanil arm were not separated to allow direct comparison.

Weighted averages were calculated taking into account both population size and heterogeneity.

Data are from an RCT, but either the study was not designed to test the efficacy of atovaquone/proguanil (or another antimalarial with atovaquone/proguanil as the control) or the trial data are not described.

Denominator excludes patients with mixed infections or those receiving non-atovaquone/proguanil treatments (<15% of the total for each study). Denominator would increase if these patients were included, but the overall cure rates would remain unchanged at 100%.

Of note, only 14 of the studies were RCT designed to test the efficacy of atovaquone/proguanil or used atovaquone/proguanil as a control treatment and participants of these made up only 55% of the total participants included here. Most of the studies from which these data were gathered, including the RCT, were of low methodological quality, being small and having between 18 and 253 participants receiving atovaquone/proguanil. Risk of bias during selection was determined to be unclear in 10 of 14 RCT group studies, as methods for randomization and concealment of allocation were unclear (Table 2). Risk of bias during performance was determined to be high in 13 of 14 studies, as blinding of participants and researchers was used in only one study. Risk of detection bias was determined to be unclear in all but one RCT study, as allocated interventions were not blinded. Risk of bias due to a high rate of attrition (<10%, low; between 10% and 20%, medium; >20% high) or patients withdrawn from the trial without explanation was high in only one RCT study. Risk of bias due to selective reporting was low to medium in all studies as 28 day cure rate was defined as either a primary (low) or secondary (medium) outcome in all cases. Another potential bias was that 11 of the 14 RCT studies were carried out by, funded by or supported by GlaxoSmithKline or its preceding companies Glaxo Wellcome and Wellcome Research Laboratories.

Table 2.

Risk of bias in RCT

| Paper | Type of bias |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| selection |

performance | detection | attrition | reporting | other | ||

| RSG | AC | ||||||

| Anabwani et al. 199930 | unclear | unclear | high | unclear | low | low | unclear |

| Borrmann et al. 200331 | low | low | high | unclear | medium | low | unclear |

| Bouchard et al. 200032 | unclear | unclear | high | unclear | medium | low | unclear |

| Bustos et al. 199933 | unclear | unclear | high | unclear | low | low | unclear |

| Carrasquilla et al. 201217 | unclear | unclear | high | low | low | medium | low |

| de Alencar et al. 199734 | unclear | unclear | high | unclear | medium | medium | unclear |

| Gürkov et al. 200835 | unclear | unclear | high | unclear | low | medium | low |

| Giao et al. 200436 | low | low | high | unclear | low | medium | unclear |

| Llanos-Cuentas et al. 200137 | unclear | unclear | high | unclear | low | low | unclear |

| Looareesuwan et al. 199938 | unclear | unclear | high | unclear | medium | low | unclear |

| Mulenga et al. 199939 | unclear | unclear | high | unclear | low | low | unclear |

| Mulenga et al. 200621 | low | unclear | low | unclear | high | low | unclear |

| Radloff et al. 199640 | low | unclear | high | unclear | medium | medium | unclear |

| Tahar et al. 201441 | unclear | unclear | high | unclear | low | medium | low |

RSG, random sequence generation; AC, allocation concealment.

High-quality data for the efficacy of atovaquone/proguanil are scarce, but provide estimates of treatment success in RCT group studies of between 89% and 98% for P. falciparum malaria (Table 1; weighted averages based on population size and heterogeneity), between 20% and 26.3% for P. vivax malaria (from one study) and 100% (in three patients each) for P. malariae and P. ovale spp. malaria.

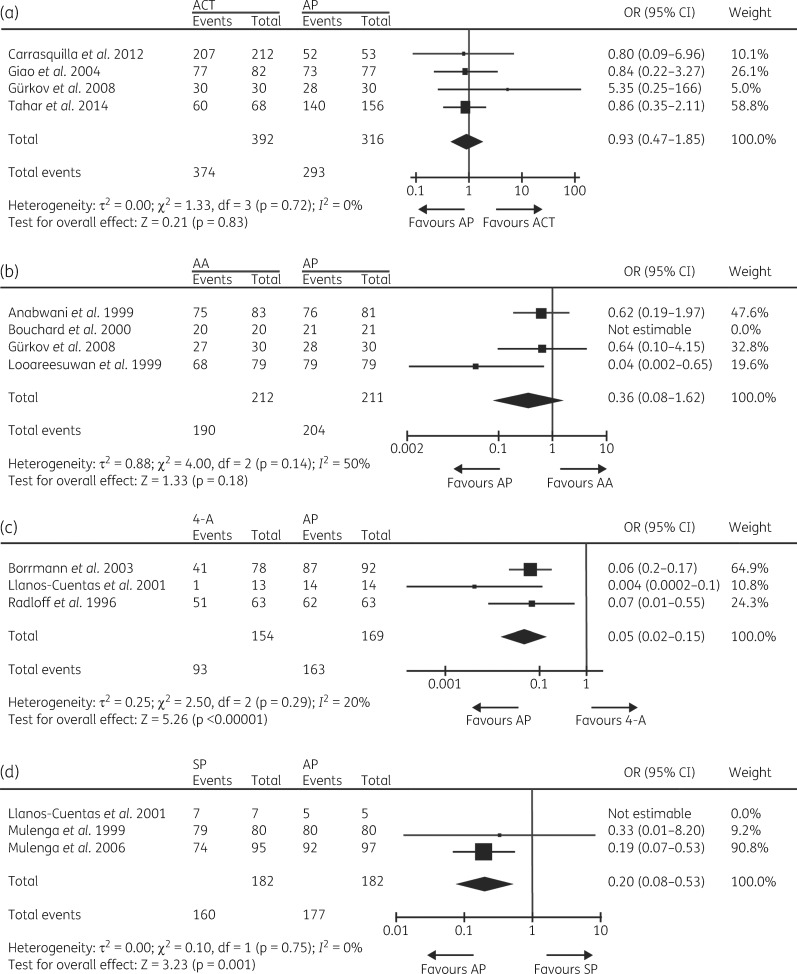

Comparator antimalarial treatments (with number of times trialled in parentheses) were chloroquine (two), amodiaquine (two), sulfadoxine/pyrimethamine (three), chloroquine/sulfadoxine/pyrimethamine (one), quinine (one), quinine/tetracycline (one), halofantrine (two), mefloquine (one), and the artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACT), artemether/lumefantrine (two), artesunate/mefloquine (one), artesunate/amodiaquine (one) and dihydroartemisinin/piperaquine/trimethoprim/primaquine (one). Nine of the 14 RCT presented here were analysed in a previous Cochrane Library systematic review from 2005.16 Subsequent RCT involving atovaquone/proguanil have used ACT predominantly as the comparator treatment(s). Given the diversity of treatments used in the trials and to allow results to be generalized to a larger population, trial data involving ACT, 4-aminoquinolines (chloroquine and amodiaquine) and amino alcohols (mefloquine, halofantrine and quinine), were grouped for a meta-analysis (Table S1). Sulfadoxine/pyrimethamine was analysed alone. The analysis indicates that there is no significant difference (P = 0.83) in treatment success between the use of atovaquone/proguanil and ACT (Figure 3a). Sensitivity analysis was consistent with this outcome (Table S2). Given the grouped ACT in this analysis, we combined the data for two different ACT in one three-arm study.17 However, analysing each arm separately did not change the outcome of the analysis (Table S2). Analysis of atovaquone/proguanil versus the amino alcohols group (Figure 3b) indicates that treatment success with atovaquone/proguanil is not significantly more effective (P = 0.18) and statistical significance was maintained for the majority of scenarios during sensitivity analysis (Table S2). As previously reported individually for amodiaquine and chloroquine,16 meta-analysis of the three trials that used atovaquone/proguanil versus 4-aminoquinolines (Figure 3c) suggested that atovaquone/proguanil is more effective than 4-aminoquinolines (P < 0.00001) and the sensitivity analysis was predominantly consistent with this outcome (Table S2). This can be explained by the prevalence of mutations in pfcrt and pfmdr1 conferring resistance to chloroquine and amodiaquine in the regions of study.18–20 Similar findings (P = 0.001) emerged when analysing atovaquone/proguanil versus sulfadoxine/pyrimethamine (Figure 3d and Table S2). This can be explained by the increasing development of sulfadoxine/pyrimethamine resistance over time between the two studies undertaken in Zambia.21,39

Figure 3.

Forest plots for the relative treatment successes at day 28 of patients treated with atovaquone/proguanil (AP) or (a) ACT, (b) amino alcohols (AA), (c) 4-aminoquinolines (4-A) or (d) sulfadoxine/pyrimethamine (SP).

Eligible data on in vitro/ex vivo clinical isolates exposed to atovaquone were available in 15 papers (Table 3). The amount of data and the level of detail available did not allow further mathematical syntheses, but the data can be used to hypothesize about what the in vitro/ex vivo phenotype of atovaquone resistance might be. All P. falciparum isolates with the WT Y amino acid at codon 268 have an atovaquone IC50 ≤28 nM, with the majority <10 nM. All single isolates with N, C or S at 268 have IC50 values between 20.5 and 17 000 nM. A further four isolates with S at 268 were reported to have a median (IQR) IC50 value of 5.7 nM (1.7–1216).22 Isolates with mixed genotypes were susceptible to atovaquone in vitro, with median IC50 values between 4.7 and 5 nM. Isolates of unknown genotype ranged in IC50 values from low nanomolar to low micromolar. The 38 P. vivax isolates had a pooled mean IC50 value of 29.4 nM.23

Table 3.

Characteristics of in vitro/ex vivo studies

| Paper | Species of Plasmodium | Country of infection | Country of diagnosis/ treatment | Period of studya | Number of isolates | Atovaquone IC50 (nM) | Dispersion (nM) | Codon 268 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basco 200357 | P. falciparum | Cameroon | Cameroon | 2001–02 | 37 | 0.58 geometric mean | 0.27–2.2 range | Y |

| Durand et al. 200858 | P. falciparum | DRC | France | 2007 | 1b | 10 | not stated | Y |

| Fivelman et al. 200211 | P. falciparum | Nigeria | UK | 2002 | 1c | 1888 mean | 107 SD | N |

| Gay et al. 199746 | P. falciparum | worldwide | The Philippines, France | 1993–95 | 96 | 1.4 median | 5.5 90th percentile | – |

| Ingasia et al. 201522 | P. falciparum | Kenya | Kenya | 2008–12 | 143 | 3 median | 1–6.9 IQR | Y |

| 4 | 5.7 median | 1.7–1216 IQR | S | |||||

| 74 | 4.7 median | 2.2–11.1 IQR | Y/S | |||||

| 6 | 5 median | 2–11.8 IQR | Y/S/N | |||||

| Khositruithikul et al. 200859 | P. falciparum | Thailand | Thailand | 1998–2005 | 83 | 3.4 mean | 1.6 SD | Y |

| 0.83–6.81 range | ||||||||

| Legrand et al. 200760 | P. falciparum | French Guiana | French Guiana | 2005 | 1b | 1.6 | not stated | Y |

| 1c | 20.5 | not stated | S | |||||

| Looareesuwan et al. 199655 | P. falciparum | Thailand | Thailand | 1990–93 | 12b | 9 mean | not stated | – |

| NS | 13 486 mean | not stated | – | |||||

| 3c | 10.4 mean | not stated | – | |||||

| 3d | 3.3 mean | not stated | – | |||||

| Lütgendorf et al. 200661 | P. falciparum | Thailand | Thailand | 2000 | 37b | 3.2 | not stated | – |

| Musset et al. 200662 | P. falciparum | worldwide | France | 1999–2004 | 477 | 1.79 geometric mean, 2 mediane | 0.1–28 range | Y |

| 1c | 8230 | not stated | S | |||||

| Musset et al. 200612 | P. falciparum | W. Africa | France | 2003–05 | 1c | 9.89 | not stated | Y |

| 1c | 1.49 | not stated | Y | |||||

| 1c | 7.87 | not stated | Y | |||||

| 1c | 17 000 | not stated | C | |||||

| 1c | 8230 | not stated | S | |||||

| 1c | 10 400 | not stated | S | |||||

| Savini et al. 200863 | P. falciparum | Comoros | France | 2008 | 1b | 2.9 | not stated | Y |

| 1c | 390 | not stated | S | |||||

| Tahar et al. 201441 | P. falciparum | Cameroon | Cameroon | 2008–09 | 55b | 1.32 geometric mean | 1.06–1.65 95% CI | Y |

| 0.184–5.30 range | ||||||||

| Treiber et al. 201123 | P. vivax | Thailand | Thailand | 2008 | 38 | 29.4 mean | not stated | – |

| van Vugt et al. 200264 | P. falciparum | Thailand | Thailand | 1998–2000 | 39b | 2.21 median | 0.11–17.8 range | – |

| 10c | 2.86 median | 0.84–38.9 range | – |

NS, recurrence after atovaquone treatment alone – although number not stated.

Where not given, the year of publication is given in italics.

Pretreatment.

Recurrence after atovaquone/proguanil treatment.

Pretreatment isolates from c.

Means include the data from the isolate taken after recurrence after atovaquone/proguanil treatment.

Data for case reports were available from 20 papers for 36 individuals (Table 4). Thirty-three of the cases were of P. falciparum infection and there was one case each of P. malariae, P. ovale spp. and P. vivax infection. Variables have been summarized, with means, standard deviations (SD), medians and IQR for continuous or count data and proportions for categorical or binary data types (Table S3). Data for pretreatment parasitaemia (baseline), parasitaemia at treatment failure/recrudescence and genotype were not available for non-falciparum infections and so these species were not included in subsequent analyses.

Table 4.

Characteristics of case reports

| Paper | Species of Plasmodium | Country of infection | Country of diagnosis/ treatment | Period of studya | Pretreatment parasitaemia (%) | Codon 268 pretreatmentb | Days until symptomatic | Days until parasitological diagnosis | Minimum days until recrudescence | Parasitaemia at recrudescence (%) | Codon 268 post- treatmentb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blossom et al. 200565 | P. vivax | Zambia | USA | 2002 | – | – | 21 | 21 | 21 | – | – |

| Contentin et al. 201166 | P. falciparum | Guinea | France | 2011 | 7 | – | 20 | 20 | 20 | 1.7 | – |

| David et al. 200367 | P. falciparum | Cameroon | Denmark | 2002 | 1 | – | 21 | 21 | 21 | 2.5 | – |

| Durand et al. 200858 | P. falciparum | DRC | France | 2007 | 1.6 | Y** | – | 28 | 28 | 0.001 | Y** |

| Färnert et al. 200310 | P. falciparum | Ivory Coast | Sweden | 2000 | 1 | Y* | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4 | Y* |

| 0.5 | S* | 28 | 28 | 28 | 1.6 | S** | |||||

| Fivelman et al. 200211 | P. falciparum | Nigeria | UK | 2002 | 1.5 | – | 28 | 33 | 28 | <1 | N |

| Forestier et al. 201168 | P. falciparum | Cameroon | France | 2009 | 2 | – | 21 | 21 | 21 | 3 | – |

| Koch et al. 200769 | P. falciparum | Ghana | Germany | 2007 | 1 | – | 4 | 4 | 4 | <1 | – |

| Kuhn et al. 200570 | P. falciparum | Sierra Leone | Canada | 2005 | – | Y** | 19 | – | 19 | – | S** |

| Legrand et al. 200760 | P. falciparum | French Guiana | French Guiana | 2005 | – | Y** | – | 24 | 24 | – | S** |

| Müller-Stöver et al. 200771 | P. malariae | Nigeria | Germany | 2007 | – | – | 98 | 98 | 98 | – | – |

| Musset et al. 200612 | P. falciparum | W. Africa | France | 2003–05 | 0.002 | Y* | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0.5 | Y* |

| 0.3 | Y** | – | 7 | 7 | 1 | Y** | |||||

| 0.007 | Y** | 11 | 11 | 11 | 0.75 | Y** | |||||

| 0.35 | Y** | 22 | 22 | 22 | 0.47 | C** | |||||

| 13 | Y** | 26 | 26 | 26 | 5 | S** | |||||

| 4 | Y** | 26 | 26 | 26 | 5 | C** | |||||

| 0.15 | Y** | 39 | 39 | 39 | 0.25 | S** | |||||

| 0.2 | Y* | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1.1 | Y* | |||||

| 2.8 | Y** | – | 28 | 28 | 1.5 | S** | |||||

| Oswald et al. 200772 | P. ovale spp. | Mozambique | USA | 2007 | – | – | 31 | 45 | 31 | – | – |

| Perry et al. 200973 | P. falciparum | India, Nepal | Canada | 2007 | 3.4 | – | 18 | 34 | 18 | 2 | C |

| Plucinski et al. 201474 | P. falciparum | Nigeria | USA | 2012–13 | <5 | Y** | 31 | 34 | 31 | 3 | S** |

| Rose et al. 200875 | P. falciparum | Mozambique | Canada | 2006 | 1.2 | – | – | 33 | 33 | 3.2 | S |

| Savini et al. 200863 | P. falciparum | Comoros | France | 2008 | 0.5 | Y** | 23 | 23 | 23 | 1.3 | S** |

| Schwartz et al. 200376 | P. falciparum | Kenya | Israel | 2002 | 3 | Y** | 30 | 30 | 30 | – | S** |

| Sutherland et al. 200827 | P. falciparum | Africa | Africa, UK, Switzerland | 2004–08 | – | – | – | 42 | 42 | 1.1 | C |

| 1 | – | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4 | Y | |||||

| 2.5 | – | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0.1 | Y | |||||

| 0.1 | – | 23 | 25 | 23 | 0.3 | S | |||||

| – | – | – | 4 | 4 | 1 | Y | |||||

| – | – | – | 21 | 21 | 0.2 | C | |||||

| <0.1 | Y | 26 | 26 | 26 | <0.1 | C | |||||

| – | – | 32 | 32 | 32 | 3 | C | |||||

| Wichmann et al. 200477 | P. falciparum | DRC | Germany | 2004 | 0.1 | Y | 19 | 19 | 19 | 0.01 | Y |

Where not given, the year of publication is given in italics.

Where given,

PfDHFR S108, N51, C59 and

PfDHFR S108N, N51I, C59R.

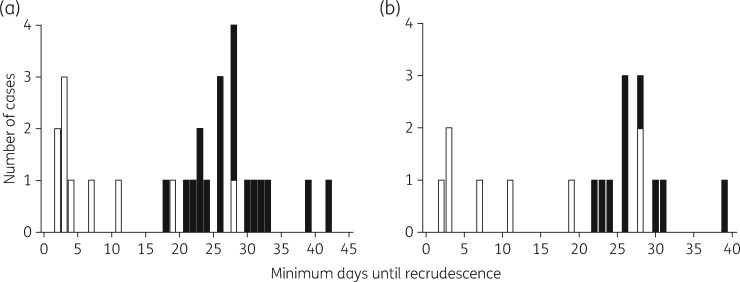

A raw data plot, Figure 4(a), presents the minimum number of days to recrudescence of infection after atovaquone/proguanil treatment, which takes into account the onset of symptoms if prior to parasitological diagnosis, versus the absence or presence of mutation (Y268S/C/N) in PfCYTb at the time of recrudescence. This suggests that distributions may differ across groups by mutation (confirmed by a preliminary Kruskal–Wallis test; P < 0.001). In a subset of parasite isolates it was possible to define if there had been a change in codon 268 following treatment. A raw data plot of the minimum number of days to recrudescence versus this dataset suggested distributions may differ by codon 268 change (P = 0.009; Kruskal–Wallis test; Figure 4b).

Figure 4.

Relationship between the number of days until recrudescence of malaria infection and the status of codon 268 in PfCYTb. Numbers of cases of patients infected with P. falciparum parasites (a) with (white bars) or without (black bars) mutation at codon 268 in PfCYTb at the time of recrudescence and (b) with (white bars) or without (black bars) a change at codon 268 in PfCYTb between the initial infection and the time of recrudescence.

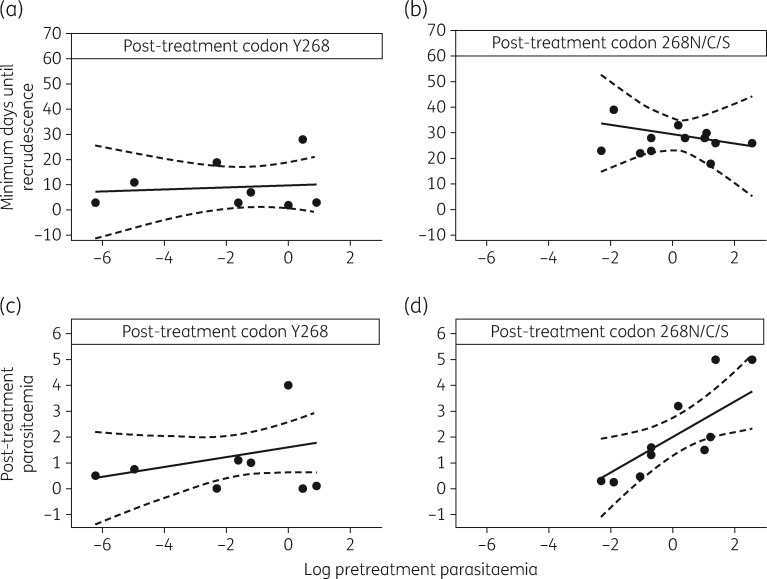

Figure 5 presents the relationship between pretreatment parasitaemia and minimum days until recrudescence in the absence or presence of a mutation in PfCYTb, using an interaction model (Figure 5a and b). Analyses of the complete and observed (by multiple imputation) datasets suggest that pretreatment parasitaemia does not appear to influence the minimum days until recrudescence in general and that there is evidence that this effect is not modified by the presence of mutation in PfCYTb (P = 0.62 and 0.87, respectively; Table S4). However, according to complete data analysis, there is evidence (P < 0.001; Table S4) that grouping (the codon 268 present post-treatment) is a statistically significant predictor of the minimum days until recrudescence and the evidence is further supported by the observed data analysis (P = 0.002; Table S4). The model predicts that patients presenting with a baseline parasitaemia of 1% will have an average minimum number of days until recrudescence of 29 (95% CI: 22, 35) days if mutation in codon 268 in PfCYTb is present, whilst this is 19 (95% CI: 7.3, 30) days shorter in duration if the mutation is absent. Note that although a slight departure from normality for the standardized residuals (P = 0.02) was calculated, we opted for model simplicity rather than introducing another quadratic term.

Figure 5.

Relationship between pretreatment parasitaemia and (a and b) minimum days until recrudescence and (c and d) post-treatment parasitaemia in the absence or presence of mutation at codon 268 in PfCYTb. Complete data sets (filled circles) are shown with predicted lines of fit by multiple imputation (continuous lines) and their 95% CI (broken lines).

Figure 5 also presents the relationship between baseline pretreatment parasitaemia and parasitaemia at recrudescence (post-treatment parasitaemia) in the absence or presence of a mutation in PfCYTb, using an interaction model (Figure 5c and d). Analyses of the complete and observed datasets suggest that baseline parasitaemia (on a log scale) increases slightly and linearly with parasitaemia at recrudescence of infection (P = 0.004 and 0.029, respectively; Table S5). Furthermore, analysis of the complete dataset suggests that the level of increase differs by grouping using codon 268 presence post-treatment, although this effect no longer holds when observed data analysis has been implemented (P = 0.04 versus P = 0.217; Table S5). Note that the two settings do not exhibit massive differences in estimates and their precisions. Here, the model predicts that patients presenting with a baseline parasitaemia of 1% (geometric mean, which coincides with the median; Table S5) will have an average post-treatment parasitaemia of 2.0% (95% CI: 1.2%, 2.8%) if a mutation in codon 268 in PfCYTb is present.

Additional analyses to incorporate pretreatment parasitaemia interval values as <0.01 and <5 (Table 4), using scenarios in which these values were ‘1’, their upper limit, ‘2’, half the interval values and ‘3’, a 10th of the value, provided no substantial quantitative changes in the above estimates presented and their precision and no qualitative changes to the conclusion (Table S6 and Table S7).

Discussion

Atovaquone/proguanil was developed as a combination therapy when early clinical studies showed that atovaquone as a single agent was associated with recrudescence of highly atovaquone-resistant infections in ∼30% of patients.24In vitro evidence of synergy with proguanil prompted development of this combination, whose initial high cost precluded widespread use. As generic formulations of atovaquone/proguanil reduce costs, and as TFACT emerge, atovaquone/proguanil is one of the few non-ACT combinations registered for management of malaria. Determining its overall efficacy and identifying markers that predict treatment failures is important for policymakers in public health.

To carry out the widest scrutiny of evidence on the efficacy of atovaquone/proguanil, we included two broad types of studies. The first type (summarized in Table 1) describes efficacy of atovaquone/proguanil in the treatment of malaria often (in just over 50% of cases) in the context of an RCT. The quality of these types of studies is relatively low for several reasons associated with potentials for bias (Table 2). The second more mechanistic analysis of atovaquone/proguanil’s efficacy (summarized in Tables 3 and 4) included review of in vitro susceptibility analysis of parasites, where available, and detailed analysis of individual case reports of treatment failures and their association with parasitaemia and mutation in PfCYTb. These latter reports are often richer in data and provide insights that complement findings from larger studies.

While datasets were small and associated with potential bias (and thus requiring cautious interpretation), the overall efficacy of atovaquone/proguanil expressed as a weighted average based on study population sizes and heterogeneity is 89% and 83% in ITT analyses of RCT and observational studies, respectively, and is 98% and 99% in PP analyses. This is a reassuringly acceptable level of efficacy and to date there are no indications of treatment failures becoming associated with particular geographical areas that would preclude atovaquone/proguanil use to treat travellers or prevent infections from such areas. Furthermore, meta-analysis suggests that atovaquone/proguanil treatment success is equivalent to the use of ACT and amino alcohols and better than 4-aminoquinolines and sulfadoxine/pyrimethamine, although caution is required in some cases due to the grouping of different antimalarials within a class. This extends findings from a prior meta-analysis that concluded that atovaquone/proguanil is more effective than chloroquine, amodiaquine and mefloquine.16 This general reassurance is important particularly in light of complications that are being associated with the use of mefloquine and that have been reviewed recently in a UK House of Commons Defence Committee report on mefloquine’s use in military personnel.25 Doxycycline and atovaquone/proguanil remain as the only alternatives to mefloquine recommended for antimalarial prophylaxis.5 While atovaquone/proguanil is considered safe, it has been reported that safety data are relatively sparse and would benefit from further large trials.16 The safety of atovaquone/proguanil was not studied here.

The in vitro phenotypic assays for atovaquone susceptibility and its relationship to target genotype suggest that WT amino acid (Y268) is uniformly associated with susceptibility. The threshold for defining susceptibility is an IC50 value ≤28 nM, with most isolates in different studies having IC50 values <10 nM. Although the aggregated IC50 values for P. vivax were 29 nM, it is unlikely that this slightly higher value compared with P. falciparum susceptibility contributed to the higher treatment failure rates as these are most likely due to relapse because of the non-susceptibility of hypnozoite stages found in the liver to atovaquone/proguanil.26

Analysis of individual case reports and the dynamics of recrudescing infection highlight further interesting findings. The presence or appearance of mutation (Y268S/C/N) in PfCYTb is strongly associated with a late recrudescing infection (Figures 4 and 5) where late onset of symptoms or parasitological recrudescence (whichever is earlier, which we have defined as minimum days to recrudescence here) is on average 29 days (95% CI: 22, 35) after treatment has commenced. This is in accord with a previous estimate of the mean time to recrudescence of parasites carrying the Y268C mutation of 28 days (95% CI: 23.0, 33.0).27 Understanding the mechanisms that account for the length of time until recrudescence is worthy of further investigation. One possible factor underlying this phenotype is a loss of parasite fitness due to mutation. This has been reported previously, using in vitro growth assays, for atovaquone-resistant parasites carrying PfCYTb mutations, though not at position 268.28 Our data suggest that patients should be monitored for up to 42 days. Late recrudescence in these cases should always be treated with an alternative antimalarial treatment regimen.

A recent report has demonstrated that mutations in P. berghei CYTb are invariably lethal to the parasite during transmission in the mosquito vector.13 This finding lends weight to the hypothesis that PfCYTb mutations may not be able to spread within a population. If true, this would preclude the requirement to monitor for these mutations in endemic areas. The available data are in general agreement with this, as codon 268 mutations are very rarely observed in parasites from patients that suffer later recrudescence, prior to drug pressure (Table 4) and no geographical foci of atovaquone/proguanil treatment failure or PfCYTb mutations have been reported. However, this does not preclude the spread of PfCYTb mutations carried by parasite sub-populations, where the mutation cannot be detected by conventional means, or the spread of parasites with permissive genetic backgrounds that favour PfCYTb mutation following drug pressure. Our findings also identify the need for further characterization of the genetic backgrounds of parasites in patients experiencing early recrudescence. These studies should aim to determine the mechanism of this high-grade resistance as well as identifying associated markers, although other factors that may cause or contribute to the phenotype of early treatment failure will need to be considered carefully (e.g. non-compliance to treatment, use of substandard or counterfeit medications, poor absorption or metabolism of the medication by the patient).

While not considered in detail, it is worth noting that there are 17 case reports that provide molecular markers for cycloguanil resistance, the triple PfDHFR mutation S108N, N51I, C59R (Table 4). Only 4 of 17 infections carried parasites with sensitive genotypes at first presentation. One of these four infections recrudesced with parasites carrying a resistant genotype, leaving three infections caused by parasites with PfDHFR-inhibitor sensitive genotypes post-treatment. Interestingly, all parasites defined as recrudescing by day 3 (Table 4) carried PfDHFR sensitive genotypes, suggesting that cycloguanil did not contribute to failure. All later treatment failures (from day 7) were caused by parasites carrying genotypes associated with resistance to cycloguanil. Therefore, atovaquone/proguanil treatment failures from day 7 onwards are most likely to be caused by parasites that are already resistant to cycloguanil.

After our database search was closed, an additional series of case reports that was not picked up was identified independently.29 These six cases were of patients who had recrudesced more than once after atovaquone/proguanil treatment and in all cases time to recrudescence was ≥19 days. In five cases where the post-treatment genotype of PfCYTb was available, it was of the 268C/S mutation. In four of six patients with second recrudescences, the time to recrudescence was ≥20 days and all four genotypes bore mutant variants at position 268. These observations suggest that the proguanil component of atovaquone/proguanil has sufficient antimalarial efficacy to suppress parasitaemias for 2–3 weeks and that the dynamics of late treatment failure are consistent with absence of atovaquone efficacy. These cases were incorporated into a secondary analysis of the case reports. Findings with regard to the relationship between pretreatment parasitaemia and minimum days until recrudescence in the absence or presence of a mutation in PfCYTb are consistent with those presented in Table S8.

Overall, atovaquone/proguanil therapy is comparable in efficacy to ACT used in treating uncomplicated malaria. Detailed genotype–phenotype analysis in this systematic review has illustrated several new findings. There are differences between early and late treatment failures because mutations in the target conferring resistance to atovaquone are identified most commonly in late and not early treatment failures. The mechanism of early treatment failure after atovaquone/proguanil treatment needs further investigation. Recent evidence is also reassuring that spread of the 268 mutations conferring atovaquone resistance may be limited by poor transmissibility in the insect stages of P. falciparum infections.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by the European Union Seventh Framework Programme under grant agreement n° 304948—NanoMal (to S. K. and H. M. S.). H. M. S. is supported by the Wellcome Trust Institutional Strategic Support Fund (204809/Z/16/Z) awarded to St George’s University of London.

Transparency declarations

None to declare.

Author contributions

S. K., together with P. G. K., designed the systematic review and meta-analysis protocol. B. H.-Y. T. and S. K. created the search strategy. B. H.-Y. T., H. M. S. and R. B. searched for publications. B. H.-Y. T., H. M. S. and R. B. did the review and data extraction. I. C. S. conducted all the statistical aspects of the study. I. C. S., H. M. S. and R. B. performed the analysis and all authors critically interpreted the results. H. M. S., R. B. and S. K. wrote the first draft of the article and all authors provided critical revisions to writing thereafter.

Supplementary data

Supplementary Methods and Tables S1 to S8 are available as Supplementary data at JAC Online.

References

- 1. WHO. Guidelines for the Treatment of Malaria, Third Edition 2015. http://www.who.int/malaria/publications/atoz/9789241549127/en/.

- 2. WHO. World Malaria Report 2016 2016. http://www.who.int/malaria/publications/world-malaria-report-2016/en/.

- 3. Krishna S, Kremsner PG.. Antidogmatic approaches to artemisinin resistance: reappraisal as treatment failure with artemisinin combination therapy. Trends Parasitol 2013; 29: 313.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. WHO. Update on Artemisinin Resistance—April 2012 2012. http://www.who.int/malaria/publications/atoz/updateartemsininresistanceapr2012/en/.

- 5. PHE. Guidelines for Malaria Prevention in Travellers from the UK 2017. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/malaria-prevention-guidelines-for-travellers-from-the-uk.

- 6. Nevin RL. Rational risk-benefit decision-making in the setting of military mefloquine policy. J Parasitol Res 2015; 2015: 260106.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Barton V, Fisher N, Biagini GA. et al. Inhibiting Plasmodium cytochrome bc1: a complex issue. Curr Opin Chem Biol 2010; 14: 440–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Srivastava IK, Vaidya AB.. A mechanism for the synergistic antimalarial action of atovaquone and proguanil. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1999; 43: 1334–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Foote SJ, Galatis D, Cowman AF.. Amino acids in the dihydrofolate reductase-thymidylate synthase gene of Plasmodium falciparum involved in cycloguanil resistance differ from those involved in pyrimethamine resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1990; 87: 3014–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Färnert A, Lindberg J, Gil P. et al. Evidence of Plasmodium falciparum malaria resistant to atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride: case reports. BMJ 2003; 326: 628–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fivelman QL, Butcher GA, Adagu IS. et al. Malarone treatment failure and in vitro confirmation of resistance of Plasmodium falciparum isolate from Lagos, Nigeria. Malar J 2002; 1: 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Musset L, Bouchaud O, Matheron S. et al. Clinical atovaquone-proguanil resistance of Plasmodium falciparum associated with cytochrome b codon 268 mutations. Microbes Infect 2006; 8: 2599–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Goodman CD, Siregar JE, Mollard V. et al. Parasites resistant to the antimalarial atovaquone fail to transmit by mosquitoes. Science 2016; 352: 349–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kaneko A, Bergqvist Y, Taleo G. et al. Proguanil disposition and toxicity in malaria patients from Vanuatu with high frequencies of CYP2C19 mutations. Pharmacogenetics 1999; 9: 317–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC. et al. The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011; 343: d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Osei-Akoto A, Orton L, Owusu-Ofori SP.. Atovaquone-proguanil for treating uncomplicated malaria. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005; issue 4: CD004529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Carrasquilla G, Barón C, Monsell EM. et al. Randomized, prospective, three-arm study to confirm the auditory safety and efficacy of artemether-lumefantrine in Colombian patients with uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2012; 86: 75–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bacon DJ, McCollum AM, Griffing SM. et al. Dynamics of malaria drug resistance patterns in the Amazon basin region following changes in Peruvian national treatment policy for uncomplicated malaria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2009; 53: 2042–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Frank M, Lehners N, Mayengue PI. et al. A thirteen-year analysis of Plasmodium falciparum populations reveals high conservation of the mutant pfcrt haplotype despite the withdrawal of chloroquine from national treatment guidelines in Gabon. Malar J 2011; 10: 304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mayengue PI, Kalmbach Y, Issifou S. et al. No variation in the prevalence of point mutations in the Pfcrt and Pfmdr1 genes in isolates from Gabonese patients with uncomplicated or severe Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Parasitol Res 2007; 100: 487–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mulenga M, Malunga P, Bennett S. et al. Folic acid treatment of Zambian children with moderate to severe malaria anemia. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2006; 74: 986–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ingasia LA, Akala HM, Imbuga MO. et al. Molecular characterization of the cytochrome b gene and in vitro atovaquone susceptibility of Plasmodium falciparum isolates from Kenya. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2015; 59: 1818–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Treiber M, Wernsdorfer G, Wiedermann U. et al. Sensitivity of Plasmodium vivax to chloroquine, mefloquine, artemisinin and atovaquone in north-western Thailand. Wien Klin Wochenschr 2011; 123 Suppl 1: 20–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Canfield CJ, Pudney M, Gutteridge WE.. Interactions of atovaquone with other antimalarial drugs against Plasmodium falciparum in vitro. Exp Parasitol 1995; 80: 373–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. House of Commons Defence Committee. An Acceptable Risk? The Use of Lariam for Military Personnel: Government Response to the Committee’s Fourth Report of Session 2015–16 2016. https://www.parliament.uk/business/committees/committees-a-z/commons-select/defence-committee/inquiries/parliament-2015/inquiry/publications/.

- 26. Dembele L, Gego A, Zeeman AM. et al. Towards an in vitro model of Plasmodium hypnozoites suitable for drug discovery. PLoS One 2011; 6: e18162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sutherland CJ, Laundy M, Price N. et al. Mutations in the Plasmodium falciparum cytochrome b gene are associated with delayed parasite recrudescence in malaria patients treated with atovaquone-proguanil. Malar J 2008; 7: 240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Peters JM, Chen N, Gatton M. et al. Mutations in cytochrome b resulting in atovaquone resistance are associated with loss of fitness in Plasmodium falciparum. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2002; 46: 2435–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cottrell G, Musset L, Hubert V. et al. Emergence of resistance to atovaquone-proguanil in malaria parasites: insights from computational modeling and clinical case reports. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2014; 58: 4504–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Anabwani G, Canfield CJ, Hutchinson DB.. Combination atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride vs. halofantrine for treatment of acute Plasmodium falciparum malaria in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1999; 18: 456–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Borrmann S, Faucher JF, Bagaphou T. et al. Atovaquone and proguanil versus amodiaquine for the treatment of Plasmodium falciparum malaria in African infants and young children. Clin Infect Dis 2003; 37: 1441–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bouchaud O, Monlun E, Muanza K. et al. Atovaquone plus proguanil versus halofantrine for the treatment of imported acute uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria in non-immune adults: a randomized comparative trial. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2000; 63: 274–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bustos DG, Canfield CJ, Canete-Miguel E. et al. Atovaquone-proguanil compared with chloroquine and chloroquine-sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine for treatment of acute Plasmodium falciparum malaria in the Philippines. J Infect Dis 1999; 179: 1587–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. de Alencar FE, Cerutti C Jr, Durlacher RR. et al. Atovaquone and proguanil for the treatment of malaria in Brazil. J Infect Dis 1997; 175: 1544–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gürkov R, Eshetu T, Miranda IB. et al. Ototoxicity of artemether/lumefantrine in the treatment of falciparum malaria: a randomized trial. Malar J 2008; 7: 179.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Giao PT, de Vries PJ, Hung LQ. et al. CV8, a new combination of dihydroartemisinin, piperaquine, trimethoprim and primaquine, compared with atovaquone-proguanil against falciparum malaria in Vietnam. Trop Med Int Health 2004; 9: 209–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Llanos-Cuentas A, Campos P, Clendenes M. et al. Atovaquone and proguani hydrochloride compared with chloroquine or pyrimethamine/sulfodaxine for treatment of acute Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Peru. Braz J Infect Dis 2001; 5: 67–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Looareesuwan S, Wilairatana P, Chalermarut K. et al. Efficacy and safety of atovaquone/proguanil compared with mefloquine for treatment of acute Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Thailand. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1999; 60: 526–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mulenga M, Sukwa TY, Canfield CJ. et al. Atovaquone and proguanil versus pyrimethamine/sulfadoxine for the treatment of acute falciparum malaria in Zambia. Clin Ther 1999; 21: 841–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Radloff PD, Philipps J, Nkeyi M. et al. Atovaquone and proguanil for Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Lancet 1996; 347: 1511–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Tahar R, Almelli T, Debue C. et al. Randomized trial of artesunate-amodiaquine, atovaquone-proguanil, and artesunate-atovaquone-proguanil for the treatment of uncomplicated falciparum malaria in children. J Infect Dis 2014; 210: 1962–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Blonde R, Naudin J, Bigirimana Z. et al. Tolerance and efficacy of atovaquone-proguanil for the treatment of paediatric imported Plasmodium falciparum malaria in France: clinical practice in a university hospital in Paris. Arch Pediatr 2008; 15: 245–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Boggild AK, Krudsood S, Patel SN. et al. Use of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ agonists as adjunctive treatment for Plasmodium falciparum malaria: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis 2009; 49: 841–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bouchaud O, Mühlberger N, Parola P. et al. Therapy of uncomplicated falciparum malaria in Europe: MALTHER—a prospective observational multicentre study. Malar J 2012; 11: 212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Chih DT, Heath CH, Murray RJ.. Outpatient treatment of malaria in recently arrived African migrants. Med J Aust 2006; 185: 598–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Gay F, Bustos D, Traore B. et al. In vitro response of Plasmodium falciparum to atovaquone and correlation with other antimalarials: comparison between African and Asian strains. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1997; 56: 315–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Grynberg S, Lachish T, Kopel E. et al. Artemether-lumefantrine compared to atovaquone-proguanil as a treatment for uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria in travelers. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2015; 92: 13–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Krudsood S, Patel SN, Tangpukdee N. et al. Efficacy of atovaquone-proguanil for treatment of acute multidrug-resistant Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Thailand. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2007; 76: 655–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lacy MD, Maguire JD, Barcus MJ. et al. Atovaquone/proguanil therapy for Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax malaria in Indonesians who lack clinical immunity. Clin Infect Dis 2002; 35: e92–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Malvy D, Djossou F, Vatan R. et al. Experience with the combination atovaquone-proguanil in the treatment of uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria—report of 112 cases. Med Trop (Mars) 2002; 62: 229–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Na-Bangchang K, Manyando C, Ruengweerayut R. et al. The pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of atovaquone and proguanil for the treatment of uncomplicated falciparum malaria in third-trimester pregnant women. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2005; 61: 573–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Sabchareon A, Attanath P, Phanuaksook P. et al. Efficacy and pharmacokinetics of atovaquone and proguanil in children with multidrug-resistant Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 1998; 92: 201–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Tahar R, Sayang C, Ngane Foumane V. et al. Field evaluation of rapid diagnostic tests for malaria in Yaounde, Cameroon. Acta Trop 2013; 125: 214–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Thybo S, Gjorup I, Ronn AM. et al. Atovaquone-proguanil (malarone): an effective treatment for uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria in travelers from Denmark. J Travel Med 2004; 11: 220–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Looareesuwan S, Viravan C, Webster HK. et al. Clinical studies of atovaquone, alone or in combination with other antimalarial drugs, for treatment of acute uncomplicated malaria in Thailand. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1996; 54: 62–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Radloff PD, Philipps J, Hutchinson D. et al. Atovaquone plus proguanil is an effective treatment for Plasmodium ovale and P. malariae malaria. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 1996; 90: 682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Basco LK. Molecular epidemiology of malaria in Cameroon. XVII. Baseline monitoring of atovaquone-resistant Plasmodium falciparum by in vitro drug assays and cytochrome b gene sequence analysis. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2003; 69: 179–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Durand R, Prendki V, Cailhol J. et al. Plasmodium falciparum malaria and atovaquone-proguanil treatment failure. Emerg Infect Dis 2008; 14: 320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Khositnithikul R, Tan-Ariya P, Mungthin M.. In vitro atovaquone/proguanil susceptibility and characterization of the cytochrome b gene of Plasmodium falciparum from different endemic regions of Thailand. Malar J 2008; 7: 23.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Legrand E, Demar M, Volney B. et al. First case of emergence of atovaquone resistance in Plasmodium falciparum during second-line atovaquone-proguanil treatment in South America. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2007; 51: 2280–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Lütgendorf C, Rojanawatsirivet C, Wernsdorfer G. et al. Pharmacodynamic interaction between atovaquone and other antimalarial compounds against Plasmodium falciparum in vitro. Wien Klin Wochenschr 2006; 118: 70–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Musset L, Pradines B, Parzy D. et al. Apparent absence of atovaquone/proguanil resistance in 477 Plasmodium falciparum isolates from untreated French travellers. J Antimicrob Chemother 2006; 57: 110–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Savini H, Bogreau H, Bertaux L. et al. First case of emergence of atovaquone-proguanil resistance in Plasmodium falciparum during treatment in a traveler in Comoros. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2008; 52: 2283–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. van Vugt M, Leonardi E, Phaipun L. et al. Treatment of uncomplicated multidrug-resistant falciparum malaria with artesunate-atovaquone-proguanil. Clin Infect Dis 2002; 35: 1498–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Blossom DB, King CH, Armitage KB.. Occult Plasmodium vivax infection diagnosed by a polymerase chain reaction-based detection system: a case report. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2005; 73: 188–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Contentin L, Grammatico-Guillon L, Desoubeaux G. et al. Atovaquone-proguanil treatment failure in Plasmodium falciparum. Presse Med 2011; 40: 1081–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. David KP, Alifrangis M, Salanti A. et al. Atovaquone/proguanil resistance in Africa: a case report. Scand J Infect Dis 2003; 35: 897–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Forestier E, Labe A, Raffenot D. et al. Post-malaria neurological syndrome complicating a relapse of Plasmodium falciparum malaria after atovaquone-proguanil treatment. Med Mal Infect 2011; 41: 41–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Koch S, Göbels K, Richter J. et al. Cerebral malaria in spite of peripheral parasite clearance in a patient treated with atovaquone/proguanil. Parasitol Res 2007; 100: 747–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Kuhn S, Gill MJ, Kain KC.. Emergence of atovaquone-proguanil resistance during treatment of Plasmodium falciparum malaria acquired by a non-immune north American traveller to west Africa. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2005; 72: 407–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Müller-Stöver I, Verweij JJ, Hoppenheit B. et al. Plasmodium malariae infection in spite of previous anti-malarial medication. Parasitol Res 2008; 102: 547–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Oswald CB, Summer AP, Fischer PR.. Relapsing malaria infection in an adolescent following travel to Mozambique. Travel Med Infect Dis 2007; 5: 254–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Perry TL, Pandey P, Grant JM. et al. Severe atovaquone-resistant Plasmodium falciparum malaria in a Canadian traveller returned from the Indian subcontinent. Open Med 2009; 3: e10–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Plucinski MM, Huber CS, Akinyi S. et al. Novel mutation in cytochrome b of Plasmodium falciparum in one of two atovaquone-proguanil treatment failures in travelers returning from same site in Nigeria. Open Forum Infect Dis 2014; 1: ofu059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Rose GW, Suh KN, Kain KC. et al. Atovaquone-proguanil resistance in imported falciparum malaria in a young child. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2008; 27: 567–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Schwartz E, Bujanover S, Kain KC.. Genetic confirmation of atovaquone-proguanil-resistant Plasmodium falciparum malaria acquired by a nonimmune traveler to East Africa. Clin Infect Dis 2003; 37: 450–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Wichmann O, Muehlen M, Gruss H. et al. Malarone treatment failure not associated with previously described mutations in the cytochrome b gene. Malar J 2004; 3: 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.