Abstract

Introduction

Anastomotic leakage continues to be one of the most serious complications following low anterior resections. Early diagnosis of a leak is difficult but critical to minimize morbidity and mortality.

Aim

To evaluate changes in serum concentrations of 27 different cytokines following low anterior resection, with the goal of finding new, early biomarkers of anastomotic leak.

Material and methods

This is a prospective observational study that includes 32 patients undergoing elective low anterior resection for rectal cancer. Blood samples were collected preoperatively and on postoperative day 3.

Results

Five patients developed anastomotic leak (15%). On postoperative day 3, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP), interleukin (IL)-6, and regulated on activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted (RANTES) were significantly higher in patients with anastomotic leak, while IL-9 and fibroblast growth factor (FGF) 2 were significantly lower. Analysis of relative changes in the concentration of cytokines from preoperative to postoperative day 3 revealed a significant increase of IL-6 and granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) in patients with an anastomotic leak. Upon receiver operating curve (ROC) analysis, the performance of hs-CRP was found to be excellent (AUC = 0.99), and performance of ΔIL-6, IL-6, RANTES, and FGF2 was good (AUC: 0.81–0.87). Patients who developed an anastomotic leak preoperatively had significantly lower levels of macrophage inflammatory protein-1 α (MIP-1α), monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1), IL-8, FGF2, and G-CSF.

Conclusions

The single most accurate serum biomarker of anastomotic leakage continues to be hs-CRP. However, when analyzing relative changes of cytokine levels, ΔIL-6 appears to be a better leak predictor than CRP.

Keywords: rectal cancer, low anterior resection, anastomotic leak, leak markers, serum cytokines

Introduction

Anastomotic leakage (AL) continues to be the most difficult complication following low anterior resection. The range of leakage can vary from 3% to 19% of rectal resection, depending on the type of operation and patient [1–4]. An early diagnosis of AL, before the patient develops serious complications, can minimize morbidity and mortality [5, 6]. Nonetheless, identification of dehiscence is often difficult and delayed to the point where the patient’s well-being is already at risk.

Today, the diagnosis of AL relies on clinical assessment, biochemical markers, and imaging studies, which still may not provide all the information needed [7]. It is clear that the current means of AL diagnosis are not always satisfactory, thereby creating the need for newer, more effective methods to be researched and instituted.

The most commonly used method to identify AL is C-reactive protein (CRP) testing [8, 9]. It is a non-specific, acute phase reactant, released in response to inflammation. Its ability to aid early detection of AL has been well documented [9]. Two major drawbacks of CRP testing are the low specificity and low positive predictive values associated with the method. Persistent postoperative CRP increases can often be related to a number of complications that are not necessarily linked to AL.

Aim

In this study, the authors evaluated postoperative changes in serum concentration of 27 different cytokines following low anterior resection for rectal cancer, with the goal of finding new, early biomarkers of anastomotic leak.

Material and methods

Study population

Patients enrolled in this study were recruited as part of a prospective, non-randomized study comparing inflammatory, immune, and angiogenic responses in colorectal patients following robotic and conventional surgery. It was conducted as part of the WROVASC – Integrated Cardiovascular Center project. The study population consisted of 32 unselected patients with rectal adenocarcinoma (located within 12 cm of the anal verge), who underwent elective restorative rectal resection at the Regional Specialist Hospital, Wroclaw, Poland between 2013 and 2015. Exclusion criteria included patients under 18 years of age, emergency operations, advanced cancers that were not amenable to curative resection, immunosuppression, current steroid use, and patients with American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status ≥ 4.

Preoperative workup included a physical examination, colonoscopy, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the pelvis, computed tomography (CT), abdomen, pelvis and chest X-ray or chest CT. Patients with suspected nodal involvement and patients with T3 or T4 tumors underwent neo-adjuvant treatment. Patients were given the choice to undergo either open colorectal surgery (OCS) or robot-assisted colorectal surgery (RACS), after receiving detailed information from the operating surgeon as to the advantages and disadvantages of each technique.

The standard clinical pathway was applied to all patients. Everyone received intravenous antibiotic prophylaxis prior to incision. Postoperatively, oral liquids were permitted on postoperative day 1 and, if tolerated, advanced to liquid and solid diets on postoperative days 2 and 3. Nasogastric tubes were not inserted and surgical closed drains were removed on postoperative day 1. The criteria for discharge included tolerance of a soft diet and no patient complaints or reported complications.

Patient demographics, comorbidities, perioperative outcomes, and postoperative complications (up to 30 days after surgery) were recorded prospectively in the database. Anastomotic dehiscence was defined as “a communication between the intra- and extraluminal compartments, owing to a defect of the integrity of the intestinal wall at the anastomosis between the colon and rectum or the colon and anus” in accordance with the International Study Group of Rectal Cancer [10]. Blood samples from patients were collected prior to surgery and at postoperative day 3, prior to any clinical manifestation of AL. The study protocol was approved by the Medical Ethics Committees of the Regional Specialist Hospital. Informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Analytical methods

Blood was drawn by venipuncture, allowed to clot for 30 minutes, and then centrifuged (15 min, 720×g). Sera were collected, aliquoted, and kept frozen at –80° until examination. The concentrations of 27 cytokines were measured and included: IL-1β, IL-1ra, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-7, IL-8, IL-9, IL-10, IL-12 (p70), IL-13, IL-15, IL-17, interferon (IFN)-γ, IFN-γ-inducible protein (IP)-10, eotaxin-1, FGF-2, G-CSF, granulocyte-monocyte colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP)-1, macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-1α and -1β, regulated on activation, normal T-cell expressed and secreted (RANTES), tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-A, and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF)-BB. Measurements were performed in duplicate, according to the manufacturer’s instructions, using the BioPlex 200 System (Bio-Rad, Hercules CA). The system uses a flow cytometry-based method utilizing magnetic microspheres conjugated with monoclonal antibodies (Luminex xMAP technology) for simultaneous determination of analytes. Standard curves and concentrations were calculated using Bioplex Manager 6.0 software (Bio-Rad) and based on the five-parameter logistic plot regression formula. Finally, hs-CRP was measured using the Multigent CRP Vario immunoturbidimetric test with the Architect 4100 Ci analyzer (Abbott Laboratories, Lake Bluff IL).

Statistical analysis

Data distribution was tested using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test for normality and equality of variances using the F-test. Data were analyzed using the t-test for independent samples with Welch correction when necessary or the Mann-Whitney U test, and presented, respectively, as means with 95% confidence interval (CI) or medians with interquartile range. The predictive power of cytokines was assessed using ROC analysis. Overall performance was determined in terms of area under the ROC curve (AUC) with the 95% CI. The AUC values were interpreted as follows: excellent (AUC ≥ 0.91), good (AUC: 0.81–0.90), fair (AUC: 0.71–0.80), poor (AUC: 0.50–0.70). Sensitivity and specificity of potential markers at the optimal cut-off value (based on the Youden index), as well as likelihood ratios and predictive values for assumed 9.6% prevalence of anastomotic leak [8], were also calculated.

In order to examine the effect of AL and other factors on potential biomarkers, analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was applied. All calculated probabilities were two-tailed and p-values ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The statistical analysis was conducted using MedCalc Statistical Software version 16.8 (MedCalc Software bvba, Ostend, Belgium; https://www.medcalc.org; 2016). Relative changes (increases/decreases) on postoperative day 3, as compared to baseline preoperative levels, were measured and expressed as fold increase (denoted as ΔPOD3).

Results

A total of 32 patients with rectal cancer undergoing restorative rectal resection were enrolled in the study. Of these, 18 patients underwent open rectal resection and 14 had the robot-assisted procedure. Demographic and perioperative data are shown in Table I. A total of 17 (53%) patients underwent neoadjuvant treatment and 13 (41%) patients received a defunctioning stoma. Five (15.2%) patients developed anastomotic leak. Anastomotic leaks were diagnosed between postoperative days 3 and 12. All required reoperation.

Table I.

Characteristics of rectal cancer (RC) patients

| Parameter | RC patients without leak | RC patients with leak | Probability, p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean ± SD [years] | 69.8 ±8.3 | 66.4 ±10 | 0.425t |

| Sex, F/M | 10/17 | 2/3 | 1F |

| Stage, TNM7th: 0/I/II/III/IV | 0/3/11/13/0 | 1/1/2/1/0 | 0.092χ2 |

| Stage T: Tis/1/2/3/4 | 0/0/5/17/5 | 1/0/1/3/0 | 0.096χ2 |

| Stage N: 0/1/2 | 14/6/7 | 4/0/1 | 0.414χ2 |

| Stage G: 1/2/3* | 4/20/3 | 2/3/0 | 0.350χ2 |

| ASA | 5/14/8 | 1/4/0 | 0.353χ2 |

| Length of surgery [min], mean ± SD | 205.5 ±74 | 182 ±89 | 0.539t |

| Harvested lymph nodes, n (range) | 14 (3–22) | 12 (3–22) | 0.308M |

– t-test for independent samples

– Fisher’s exact test

– chi-square test

– Mann-Whitney U test.

Cytokine concentrations

Of the 27 cytokines measured, the levels of IL-2, IL-15, and IL-17 were all below the lower limit of detection in the majority of samples assessed. As a result, they were dropped from further analysis.

On postoperative day 3, there were differences in the concentrations of IL-6, hs-CRP, IL-9, RANTES and FGF2. Interestingly, while hs-CRP, IL-6, and RANTES were significantly higher in patients with a leak, the concentrations of IL-9 and FGF2 were significantly lower (Table II).

Table II.

Comparison of serum cytokine concentrations at postoperative day 3 (POD3) in patients with and without anastomotic leak

| Cytokines (POD3) | Without leak | With leak | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inflammatory mediators: | |||

| IL-1β | 2.05 (1.6–2.7) | 1.54 (0.5–4.6) | 0.420t |

| IL-1ra | 133.8 (103–174) | 152.2 (23–1013) | 0.741t |

| IL-6 | 42.6 (25.2–72.1) | 227.7 (19–2662) | 0.024t |

| TNF-α | 30.8 (24.5–38.8) | 22.8 (9.4–55.7) | 0.326t |

| hs-CRP | 107.9 (84.7–137.4) | 314.8 (240.8–411.5) | < 0.001t |

| Th1/Th2/Th9 immune response: | |||

| IL-4 | 4.53 (3.19–5.75) | 4.31 (2.67–7.98) | 0.850M |

| IL-5 | 5.93 (2.7–9.2) | 1.78 (0.31–5.87) | 0.310t |

| IL-7 | 9.08 (6.44–17.57) | 8.89 (6.1–12.24) | 0.527M |

| IL-9 | 16.15 (13.1–20) | 7.17 (2.1–24.2) | 0.011t |

| IL-10 | 12.53 (7.9–19.9) | 12.67 (1.06–151.9) | 0.987t |

| IL-12 (p70) | 64.2 (45.8–90) | 41.1 (12.1–140) | 0.318t |

| IL-13 | 10.5 (7.98–14.9) | 7.2 (3.5–14.9) | 0.281t |

| IFN-γ | 49.8 (38–65.1) | 49.9 (20.6–120.7) | 0.993t |

| Chemokines: | |||

| Eotaxin-1 | 60 (45.2–79.6) | 45.2 (15.2–134.2) | 0.450t |

| IP-10 | 940 (688–1283) | 842 (253–2798) | 0.789t |

| IL-8 | 29 (22.4–63.6) | 42.1 (25–126) | 0.704M |

| MCP-1 | 59.9 (39–183.3) | 131.3 (65.1–346.5) | 0.255M |

| MIP-1α | 3.62 (2.88–4.55) | 2.71 (0.76–9.59) | 0.364t |

| MIP-1β | 56.3 (43–73.6) | 54.9 (7.8–386.4) | 0.951t |

| RANTES | 2710 (2119–3465) | 6561 (1410–30526) | 0.017t |

| Growth factors: | |||

| FGF2 | 23.4 (17.5–31.3) | 9.5 (3.82–23.6) | 0.023t |

| G-CSF | 83.6 (68.2–102.6) | 102.2 (25.9–404.1) | 0.502t |

| GM-CSF | 26.8 (21.6–33.4) | 30.8 (15.5–61.3) | 0.618t |

| PDGF-BB | 1520 (1129–2046) | 1438 (732–2824) | 0.883t |

| VEGF-A | 151.1 (109.5–208.6) | 150.4 (69–327.8) | 0.991t |

– t-test for independent samples

– Mann-Whitney U test. Data presented as mean with 95% CI or medians with interquartile range. All concentrations were measured in pg/ml, except for hs-CRP presented in mg/l.

Relative changes in cytokine levels

Changes in cytokine concentrations on postoperative day 3 were also compared to baseline preoperative levels. There were significantly more pronounced increases in IL-6 and G-CSF in patients with AL (Table III).

Table III.

Comparison of relative changes in serum cytokine concentrations at POD3 (ΔPOD3) as compared to cytokine baseline levels in rectal cancer patients without and with anastomotic leak

| Cytokines (ΔPOD3) | Without leak | With leak | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inflammatory mediators: | |||

| IL-1β | 1.26 (0.8–1.6) | 1.48 (0.88–2.58) | 0.613M |

| IL-1ra | 1.22 (0.95–1.57) | 1.82 (0.22–15.2) | 0.596t |

| IL-6 | 3.1 (1.6–7.1) | 20.8 (7.3–22.1) | 0.019M |

| TNF-α | 1.15 (0.96–1.37) | 1.1 (0.38–3.21) | 0.864t |

| hs-CRP | 23.8 (17.4–32.5) | 87.1 (10.5–72.1) | 0.170t |

| Th1/Th2/Th9 immune response: | |||

| IL-4 | 1.05 (0.86–1.29) | 1 (0.5–2) | 0.855t |

| IL-5 | 1.26 (0.95–1.67) | 0.69 (0.14–3.48) | 0.133t |

| IL-7 | 1.26 (0.98–1.61) | 1.39 (0.25–7.87) | 0.778t |

| IL-9 | 1.16 (0.92–1.47) | 1.36 (0.36–5.09) | 0.634t |

| IL-10 | 1.41 (0.81–2.45) | 2.2 (0.29–16.6) | 0.531t |

| IL-12 (p70) | 1.42(1.13–1.97) | 1.69 (0.95–2.39) | 0.850M |

| IL-13 | 1.06 (0.84–1.34) | 0.77 (0.33–1.81) | 0.283t |

| IFN-γ | 1.01 (0.83–1.23) | 1.06 (0.31–3.58) | 0.857t |

| Chemokines: | |||

| Eotaxin-1 | 0.81 (0.70–0.93) | 0.75 (0.29–1.93) | 0.706t |

| IP-10 | 0.73 (0.54–1.01) | 1.04 (0.45–2.4) | 0.386t |

| IL-8 | 1.09 (0.73–1.71) | 4.16 (1.53–12.93) | 0.100M |

| MCP-1 | 0.97 (0.72–1.8) | 2.89 (1.69–10.56) | 0.076M |

| MIP-1α | 1.11 (0.86–1.42) | 2.09 (0.91–3.21) | 0.237M |

| MIP-1β | 0.94 (0.73–1.2) | 1.44 (0.37–5.63) | 0.212t |

| RANTES | 0.78 (0.51–1.2) | 1.04 (0.34–2.99) | 0.609t |

| Growth factors: | |||

| FGF2 | 1.03 (0.82–1.28) | 1.02 (0.14–7.21) | 0.989t |

| G-CSF | 1.11 (0.87–1.42) | 2.27 (0.51–10) | 0.046t |

| GM-CSF | 1.05 (0.89–1.22) | 1.31 (0.41–4.2) | 0.589t |

| PDGF-BB | 0.90 (0.71–1.14) | 0.77 (0.29–2.02) | 0.617t |

| VEGF-A | 1.75 (1.26–2.45) | 1.8 (0.23–13.8) | 0.958t |

– t-test for independent samples

– Mann-Whitney U test. Data presented as mean (95% CI) or median (IQR) relative changes (fold increase at a given time point as compared to cytokine preoperative level).

Predictive power of cytokines as AL markers

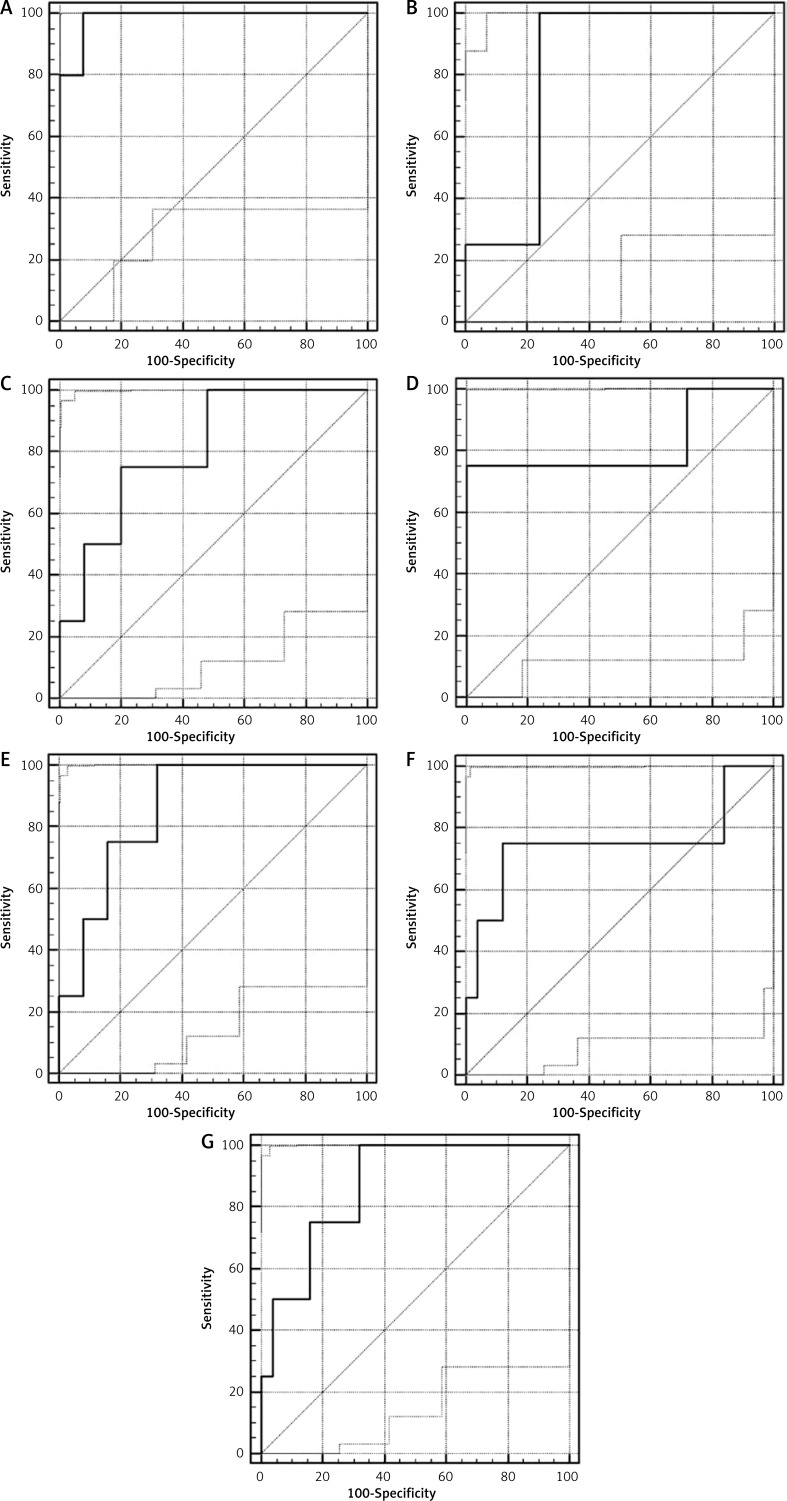

A ROC analysis was used to evaluate the power of cytokines as potential AL markers. Only cytokines, which differed significantly at postoperative day 3 were analyzed. Of these, overall performance of hs-CRP was found to be excellent while ΔIL-6, IL-6, RANTES, and FGF2 were all identified as good, and ΔG-CSF and IL-9 were devoid of predictive power (Figure 1). Additionally, specificity, likelihood ratios and predictive power of hs-CRP were superior to other markers (Table IV).

Figure 1.

ROC curves of cytokines with a potential as AL markers (hsCRP (A), IL-6 (B), RANTES (C), IL-9 (D), FGF2 (E), DG-CSF (F), (DIL-6 (G))

Table IV.

Discriminative power of analyzed cytokines as markers of anastomotic leak

| Marker | AUC (95% CI), p | Cut-off1 | Sens. and Spec. | LR+ and LR– | +PV and –PV2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hs-CRPPOD3 | 0.99 (0.86–1), < 0.0001 | > 203.8 mg/l | 100% and 92.3% | 13 and 0 | 58 and 100 |

| RANTESPOD3 | 0.81 (0.62–0.93), 0.007 | > 3689 pg/ml | 75% and 80% | 3.75 and 0.3 | 28.5 and 97 |

| IL-6POD3 | 0.82 (0.63–0.94), < 0.001 | > 65.9 pg/ml | 100% and 76% | 4.2 and 0 | 31 and 100 |

| FGF2POD3 | 0.86 (0.68–0.96), < 0.0001 | ≤ 17.4 pg/ml | 100% and 68% | 3.1 and 0 | 25 and 100 |

| IL-9POD3 | 0.82 (0.63–0.94), 0.078 | ≤ 6.8 pg/ml | 75% and 100% | – and 0.25 | 100 and 97 |

| ΔG-CSFPOD3 | 0.75 (0.56–0.89), 0.213 | > 1.9 | 75% and 88% | 6.2 and 0.3 | 40 and 97 |

| ΔIL-6POD3 | 0.87 (0.69–0.97), < 0.0001 | > 4.9 | 100% and 68% | 3.1 and 0 | 25 and 100 |

In case of relative changes (Δ) cut-off value is a fold increase at a given time point compared to cytokine baseline (preoperative) level;

prevalence of the leak following colorectal surgery was estimated to be 9.6% [8].

Factors affecting prospective biomarkers of AL

In order to test whether an elevation in the prospective biomarker at postoperative day 3 can be attributed solely to AL, the authors examined the effect of AL and cancer-related (tumor grade and cancer stage N and T), patient-related (patient’s physical status – ASA grade), and surgery-related factors (type of surgery, length and extent of surgery) using ANCOVA.

The concentrations of hs-CRP at postoperative day 3 were affected not only by AL but also by cancer-related factors such as tumor grade and depth of invasion (T stage). These seemed also to be affected by patient’s physical status, which was determined using the ASA physical status classification system, as well as by the type of surgical procedure performed (open or minimally invasive). However, no statistical significance was reached. The concentrations of IL-6 on postoperative day 3 were significantly affected by tumor grade, depth of invasion (stage T), and type of surgery. RANTES was significantly affected by the extent of surgery as measured by the number of lymph nodes harvested. FGF2 seemed to be affected by tumor grade, although the statistical significance was not reached. Relative change in IL-6 (ΔIL-6POD3) was the only prospective biomarker of AL that was not affected by factors related to cancer, the patient, or type of surgery (Table V).

Table V.

Significance of the effect exerted by cancer-, patient- or surgery-related factors on the prospective AL biomarkers when examined with AL using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA)

| Covariates | CRP(POD3) | IL-6(POD3) | FGF2(POD3) | RANTES(POD3) | ΔIL-6(POD3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer-related factors: | |||||

| AL and tumor grade (G) | AL: p = 0.001 G: p = 0.020 |

AL: p = 0.007 G: p = 0.033 |

AL: p = 0.006 G: p = 0.082 |

AL: p = 0.031 G: p = 0.668 |

AL: p = 0.006 G: p = 0.173 |

| AL and stage N (N) | AL: p < 0.001 N: p = 0.777 |

AL: p = 0.006 N: p = 0.180 |

AL: p = 0.020 N: p = 0.376 |

AL: p = 0.028 N: p = 0.804 |

AL: p = 0.006 N: p = 0.465 |

| AL and stage T (T) | AL: p < 0.00 T: p = 0.034 |

AL: p = 0.003 T: p = 0.084 |

AL: p = 0.031 T: p = 0.631 |

AL: p = 0.066 T: p = 0.337 |

AL: p = 0.003 T: p = 0.146 |

| Patient-related factors: | |||||

| AL and ASA (A) | AL: p < 0.001 A: p = 0.073 |

AL: p = 0.010 A: p = 0.328 |

AL: p = 0.040 A: p = 0.591 |

AL: p = 0.019 A: p = 0.872 |

AL: p = 0.005 A: p = 0.306 |

| Surgery-related factors: | |||||

| AL and type of surgery (S) | AL: p = 0.001 S: p = 0.095 |

AL: p = 0.124 S: p = 0.083 |

AL: p = 0.034 S: p = 0.896 |

AL: p = 0.015 S: p = 0.449 |

AL: p = 0.037 S: p = 0.144 |

| AL and length of surgery (L) | AL: p < 0.001 L: p = 0.366 |

AL: p = 0.038 L: p = 0.746 |

AL: p = 0.013 L: p = 0.211 |

AL: p = 0.009 L: p = 0.199 |

AL: p = 0.019 L: p = 0.649 |

| AL and extent of surgery (E) | AL: p < 0.001 E: p = 0.994 |

AL: p = 0.018 E: p = 0.895 |

AL: p = 0.039 E: p = 0.548 |

AL: p = 0.025 E: p = 0.036 |

AL: p = 0.012 E: p = 0.334 |

Preoperative concentrations of cytokines and AL

The authors also compared preoperative concentration of cytokines in patients who did and did not develop AL in the perioperative period (Table VI). Patients who developed AL were characterized by significantly lower baseline levels of MCP-1, MIP-1α, IL-8, FGF2, and G-CSF.

Table VI.

Comparison of preoperative serum cytokine concentrations in patients with and without anastomotic leak

| Cytokines (preoperative) | Without leak | With leak | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inflammatory mediators: | |||

| IL-1β | 1.68 (1.3–2.1) | 1.11 (0.6–2.2) | 0.140t |

| IL-1ra | 114.5 (91.8–143) | 78.6 (22.3–276) | 0.239t |

| IL-6 | 13.1 (9.1–19) | 18.1 (4.1–16) | 0.286t |

| TNF-α | 28.4 (23.6–34.3) | 20.7 (14.1–30.4) | 0.172t |

| hs-CRP | 4.01 (2.8–5.8) | 3.6 (0.4–30.8) | 0.902W |

| Th1/Th2/Th9 immune response: | |||

| IL-4 | 4.49 (3.4–7.2) | 3.58 (2.7–11.9) | 0.670M |

| IL-5 | 2.86 (1.9–4.2) | 1.27 (0.4–4.3) | 0.109t |

| IL-7 | 9.08 (7.1–11.6) | 6.15 (2.7–14.1) | 0.216t |

| IL-9 | 14.5 (11.2–18.7) | 8.06 (2–32) | 0.109t |

| IL-10 | 8.79 (6.6–11.7) | 7.09 (1.3–39.6) | 0.752W |

| IL-12 (p70) | 41.8 (31.3–55.7) | 34.1 (11.3–102) | 0.588t |

| IL-13 | 10.6 (8–14.2) | 9.8 (4.2–22.7) | 0.811t |

| IFN-γ | 52.7 (41.7–66.5) | 49.8 (21.3–117) | 0.853t |

| Chemokines: | |||

| Eotaxin-1 | 74.9 (57.8–97.1) | 56.7 (30.9–104) | 0.382t |

| IP-10 | 1213 (948–1552) | 1087 (361–3271) | 0.740t |

| IL-8 | 37.1 (26.3–52.2) | 12.3 (8.1–18.9) | 0.010t |

| MCP-1 | 77.9 (60.4–100) | 38.3 (18.6–79) | 0.031t |

| MIP-1α | 2.96 (2.52–3.65) | 1.85 (1.53–2.36) | 0.012M |

| MIP-1β | 60.7 (44.8–82.2) | 39.6 (19–82.7) | 0.257t |

| RANTES | 3417 (1881–5093) | 13090 (2064–20669) | 0.192t |

| Growth factors: | |||

| FGF2 | 23.5 (17.6–31.3) | 10 (4.3–23.2) | 0.023t |

| G-CSF | 73 (58.8–85.2) | 46.8 (33.4–65.4) | 0.027M |

| GM-CSF | 26.9 (22.1–32.7) | 23.8 (11.4–49.9) | 0.633t |

| PDGF-BB | 1854 (1389–2473) | 1832 (902–3720) | 0.973t |

| VEGF-A | 92.7 (64.9–133) | 78.3 (32.6–188) | 0.697t |

– t-test for independent samples

– Mann-Whitney U test

– t-test with Welch correction. Data presented as mean with 95% CI or medians with interquartile range. All concentrations were measured in pg/ml, except for hs-CRP presented in mg/l.

Discussion

Anastomotic leaks prolong hospital stay, increase morbidity, and contribute to one third of all postoperative deaths following colorectal surgery [11]. Because early leaks frequently cause only subtle and insidious symptoms, detection can often be difficult, even for the experienced surgeon [6, 12]. Compounding this is the fact that current diagnostic tests are frequently inadequate [7]. This includes CT scanning and contrast studies, which have limited accuracy when used for early detection [13].

When considering serum biomarkers, CRP is the most common marker used to predict AL [14]. In fact, it has proven to be a useful negative predictive test for AL on postoperative days 3–5 following colorectal surgery [8, 9, 15, 16]. Still, the downsides of CRP testing are its limited sensitivity (70%), specificity (76%), and low positive predictive value (16%), as they relate to AL [17].

Another marker used as a leak predictor is procalcitonin (PCT). This is believed to have a high specificity when detecting bacterial infection, and was initially used in intensive care units to monitor treatment of sepsis [18]. More recently, PCT has been used as a leak predictor. Its advantage over CRP is not yet clear. Lagoutte et al. evaluated leak markers between postoperative days 1 and 4 in a group of 100 colorectal patients [19]. They found PCT to be less accurate than CRP in detecting AL. Conversely, two more recent studies with larger cohorts demonstrated that PCT on postoperative day 5 had similar or better accuracy than CRP [20].

Recently, researchers have proposed evaluation of the peritoneal fluid cytokines for early detection of AL [21]. They theorize that local inflammation at the site of the anastomosis occurs before the first systemic symptoms of sepsis. In line with this is the concept that cytokines measured locally, in the proximity of anastomosis, can provide real-time information on its healing. Several studies have explored this hypothesis and have shown that levels of TNF, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-10 in drain fluid were significantly higher in patients with AL [22–25]. Furthermore, the difference in cytokine levels between patients with AL and those without AL has been observed as early as postoperative day 1.

These early data are promising, although not solid. There is a lack of information on diagnostic sensitivity and specificity of peritoneal cytokines and, in most reports, their diagnostic accuracy was low. This concept also appears to have stalled in the current era of enhanced recovery programs, in which abdominal drains are not recommended [26, 27].

Being aware that CRP is not the primary mediator of inflammation, the authors made the decision to analyze mediators upstream to CRP in the inflammatory cascade and to evaluate inflammatory and immune mediators circulating in the peripheral blood, in search of novel AL markers.

To date, only a few reports have studied the relation between postoperative concentrations of systemic cytokines and AL. In 2014, Ellebaek et al. evaluated 10 different serum cytokines in the postoperative period and observed a significant increase of IL-1β, IL-4, IL-6, IL-8, and IL-10 on postoperative days 1-5 in patients with an early leak [28]. Reisinger et al. analyzed serum inflammation markers (CRP, calprotectin, IL-6) and intestinal damage markers in patients undergoing colorectal resection [29]. They found that CRP and calprotectin (a neutrophil activation product) showed not only high sensitivity (100%), but also high specificity (89%) during AL testing on postoperative day 3.

In the present study, of the 27 parameters analyzed on postoperative day 3, IL-6, hs-CRP, IL-9, RANTES, and FGF2 differed significantly between patients with and without AL. The ROC curve analysis revealed good diagnostic accuracy of IL-6, RANTES, and FGF2 for AL, but none were superior to hs-CRP. In fact, when compared with other analyzed parameters on postoperative day 3, hs-CRP had the highest sensitivity (100%) and the highest specificity (92%). As is evident from these results, hs-CRP continues to be the single most accurate serum biomarker of AL.

It is important to note that AL is not the sole factor affecting hs-CRP and cytokine concentrations in the perioperative period. Preoperative factors, including tumor grade, stage of neoplastic disease, and the patient’s general state of health, might also influence cytokine concentrations at baseline [30, 31]. This, in turn, will have an impact on postoperative levels. Thus, if not addressed, the tumor- or patient-related factors may contribute to higher levels of cytokines and CRP, subsequently leading to false positive suspicion of AL. In this context, analysis of relative changes in the concentrations of biomarkers at postoperative day 3, in relation to their baseline preoperative levels, appears to be preferred, as it permits elimination of the effect of pre-surgical factors. As seen from this study, changes in IL-6, but not hs-CRP, were indicative of AL. Unlike absolute values measured at postoperative day 3, they were not affected by tumor- or patient-related factors. Moreover, changes in IL-6 were not affected by the type of surgical approach (robotic or open) or the length or extent of surgery, which further underlies the potential of relative IL-6 determination as an AL biomarker.

There are a number of patient-related factors associated with an increased risk of AL, including diabetes, alcohol, obesity, steroid use, malnutrition, and radiation therapy [32, 33]. Although colorectal surgeons are well versed on this subject, they are still often unable to reliably predict which anastomosis will fail. It is clear that our knowledge on the processes involved in bowel healing is still deficient.

Cytokines act as modulators of inflammatory and immune responses and may also impact the patient’s ability to heal. In this study, the analysis of baseline cytokine concentrations showed that lower baseline levels of MCP-1, MIP-1α, IL-8, FGF2, and G-CSF characterized a patient’s chance of developing AL. Because FGF2 is a transforming factor, and supports tumor growth, low levels of it may be beneficial for patients from the cancer perspective, although insufficient FGF2 expression may hamper the patient’s ability to regenerate the damaged tissues. Still, it is a critical growth factor for fibroblasts and its application has been found useful in surgical wound healing [34]. Additionally, the use of exogenous G-CSF, a hematopoietic growth factor, has been shown to be beneficial for accelerated wound healing in clinical studies [35]. Similarly, MCP-1, MIP-1α, and IL-8 chemokines are all key players in wound healing, being of particular use during the inflammatory and proliferative phase [36]. Thus, low baseline levels of the above-mentioned cytokines may be reflected as deficiencies in the patient’s ability to mount a sufficient and timely inflammatory response, as well as subsequent healing of surgical anastomosis.

This study is one of only a few reports to evaluate serum concentrations of cytokines in the early postoperative course following low anterior resections for rectal cancer. The report does have several drawbacks, including the small cohort of 32 patients and, of those, only 5 who developed AL. It should be noted, however, that the study protocol was designed to be small, with the primary goal of gathering information on the potential of serum cytokines as AL predictors. The intent was to do this prior to launching a larger study.

Conclusions

Among 27 different serum cytokines examined on postoperative day 3, hs-CRP was found to have the best diagnostic accuracy when testing for AL. When analyzing relative changes between preoperative and postoperative day 3 cytokine levels, however, relative IL-6 appears to be a better leak predictor than CRP. Additionally, relative IL-6 is not influenced by patient- or tumor-related factors other than AL. Also of note in this study, the cohort of patients with AL presented preoperatively with low levels of MCP-1, MIP-1α, IL-8, FGF2, and G-CSF, which may indicate their reduced ability to heal surgical anastomosis.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Rullier E, Laurent C, Garrelon JL, et al. Risk factors for anastomotic leakage after resection of rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 1998;85:355–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1998.00615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matthiessen P, Hallböök O, Rutegård J, et al. Defunctioning stoma reduces symptomatic anastomotic leakage after low anterior resection of the rectum for cancer: a randomized multicenter trial. Ann Surg. 2007;246:207–14. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3180603024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vignali A, Fazio VW, Lavery IC, et al. Factors associated with the occurrence of leaks in stapled rectal anastomoses: a review of 1,014 patients. J Am Coll Surg. 1997;185:105–13. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(97)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tan WP, Talbott VA, Leong QQ, et al. American Society of Anesthesiologists class and Charlson’s comorbidity index as predictors of postoperative colorectal anastomotic leak: a single-institution experience. J Surg Res. 2013;184:115–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2013.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kornmann VN, van Ramshorst B, Smits AB, et al. Beware of false-negative CT scan for anastomotic leakage after colonic surgery. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2014;29:445–51. doi: 10.1007/s00384-013-1815-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alves A, Panis Y, Trancart D, et al. Factors associated with clinically significant anastomotic leakage after large bowel resection: multivariate analysis of 707 patients. World J Surg. 2002;26:499–502. doi: 10.1007/s00268-001-0256-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hirst NA, Tiernan JP, Millner PA, Jayne DG. Systematic review of methods to predict and detect anastomotic leakage in colorectal surgery. Colorectal Dis. 2014;16:95–109. doi: 10.1111/codi.12411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singh PP, Zeng IS, Srinivasa S, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of use of serum C-reactive protein levels to predict anastomotic leak after colorectal surgery. Br J Surg. 2014;101:339–46. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garcia-Granero A, Frasson M, Flor-Lorente B, et al. Procalcitonin and C-reactive protein as early predictors of anastomotic leak in colorectal surgery: a prospective observational study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56:475–83. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e31826ce825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rahbari NN, Weitz J, Hohenberger W, et al. Definition and grading of anastomotic leakage following anterior resection of the rectum: a proposal by the International Study Group of Rectal Cancer. Surgery. 2010;147:339–51. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2009.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Snijders HS, Wouters MW, van Leersum NJ, et al. Meta-analysis of the risk for anastomotic leakage, the postoperative mortality caused by leakage in relation to the overall postoperative mortality. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2012;38:1013–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2012.07.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sutton CD, Marshall LJ, Williams N, et al. Colorectal anastomotic leakage often masquerades as a cardiac complication. Colorectal Dis. 2004;6:21–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2004.00574.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sparreboom CL, Wu ZQ, Ji JF, Lange JF. Integrated approach to colorectal anastomotic leakage: communication, infection and healing disturbances. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:7226–35. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i32.7226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mik M, Berut M, Dziki L, Dziki A. Does C-reactive protein monitoring after colorectal resection with anastomosis give any practical benefit for patients with intra-abdominal septic complications? Colorectal Dis. 2016;18:O252–9. doi: 10.1111/codi.13386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zawadzki M, Czarnecki R, Rzaca M, et al. C-reactive protein and procalcitonin predict anastomotic leaks following colorectal cancer resections – a prospective study. Videosurgery Miniinv. 2016;10:567–73. doi: 10.5114/wiitm.2015.56999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Poskus E, Karnusevicius I, Andreikaite G, et al. C-reactive protein is a predictor of complications after elective laparoscopic colorectal surgery: five-year experience. Videosurgery Miniinv. 2015;10:418–22. doi: 10.5114/wiitm.2015.54077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reynolds IS, Boland MR, Reilly F, et al. C-reactive protein as a predictor of anastomotic leak in the first week after anterior resection for rectal cancer. Colorectal Dis. 2017;19:812–8. doi: 10.1111/codi.13649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Biron BM, Ayala A, Lomas-Neira JL. Biomarkers for sepsis: what is and what might be? Biomark Insights. 2015;10(Suppl 4):7–17. doi: 10.4137/BMI.S29519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lagoutte N, Facy O, Ravoire A, et al. C-reactive protein and procalcitonin for the early detection of anastomotic leakage after elective colorectal surgery: pilot study in 100 patients. J Visc Surg. 2012;149:e345–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jviscsurg.2012.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giaccaglia V, Salvi PF, Antonelli MS, et al. Procalcitonin reveals early dehiscence in colorectal surgery: the PREDICS study. Ann Surg. 2016;263:967–72. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yamamoto T, Umegae S, Matsumoto K, Saniabadi AR. Peritoneal cytokines as early markers of peritonitis following surgery for colorectal carcinoma: a prospective study. Cytokine. 2011;53:239–42. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fouda E, El Nakeeb A, Magdy A, et al. Early detection of anastomotic leakage after elective low anterior resection. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15:137–44. doi: 10.1007/s11605-010-1364-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bertram P, Junge K, Schachtrupp A, et al. Peritoneal release of TNF-alpha and IL-6 after elective colorectal surgery and anastomotic leakage. J Invest Surg. 2003;16:65–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Herwig R, Glodny B, Kühle C, et al. Early identification of peritonitis by peritoneal cytokine measurement. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:514–21. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6231-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sammour T, Singh PP, Zargar-Shoshtari K, et al. Peritoneal cytokine levels can predict anastomotic leak on the first postoperative day. Dis Colon Rectum. 2016;59:551–6. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang HY, Zhao CL, Xie J, et al. To drain or not to drain in colorectal anastomosis: a meta-analysis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2016;31:951–60. doi: 10.1007/s00384-016-2509-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rondelli F, Bugiantella W, Vedovati MC, et al. To drain or not to drain extraperitoneal colorectal anastomosis? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Colorectal Dis. 2014;16:O35–42. doi: 10.1111/codi.12491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ellebæk MB, Baatrup G, Gjedsted J, et al. Cytokine response in peripheral blood indicates different pathophysiological mechanisms behind anastomotic leakage after low anterior resection: a pilot study. Tech Coloproctol. 2014;18:1067–74. doi: 10.1007/s10151-014-1204-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reisinger KW, Poeze M, Hulsewé KW, et al. Accurate prediction of anastomotic leakage after colorectal surgery using plasma markers for intestinal damage and inflammation. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;219:744–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2014.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krzystek-Korpacka M, Zawadzki M, Neubauer K, et al. Elevated systemic interleukin-7 in patients with colorectal cancer and individuals at high risk of cancer: association with lymph node involvement and tumor location in the right colon. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2017;66:171–9. doi: 10.1007/s00262-016-1933-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krzystek-Korpacka M, Diakowska D, Kapturkiewicz B, et al. Profiles of circulating inflammatory cytokines in colorectal cancer (CRC), high cancer risk conditions, and health are distinct. Possible implications for CRC screening and surveillance. Cancer Lett. 2013;337:107–14. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mäkelä JT, Kiviniemi H, Laitinen S. Risk factors for anastomotic leakage after left-sided colorectal resection with rectal anastomosis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:653–60. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6627-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cong ZJ, Fu CG, Wang HT, et al. Influencing factors of symptomatic anastomotic leakage after anterior resection of the rectum for cancer. World J Surg. 2009;33:1292–7. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-0008-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nunes QM, Li Y, Sun C, et al. Fibroblast growth factors as tissue repair and regeneration therapeutics. Peer J. 2016;4:e1535. doi: 10.7717/peerj.1535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fine JD, Manes B, Frangoul H. Systemic granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) enhances wound healing in dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa (DEB): results of a pilot trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:56–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rees PA, Greaves NS, Baguneid M, Bayat A. Chemokines in wound healing and as potential therapeutic targets for reducing cutaneous scarring. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle) 2015;4:687–703. doi: 10.1089/wound.2014.0568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]