Abstract

Healthcare reform typically involves orchestrating a policy change, mediated through some form of operational, systems, financial, process or practice intervention. The aim is to improve the ways in which care is delivered to patients. In our book ‘Health Systems Improvement Across the Globe: Success Stories from 60 Countries’, we gathered case-study accomplishments from 60 countries. A unique feature of the collection is the diversity of included countries, from the wealthiest and most politically stable such as Japan, Qatar and Canada, to some of the poorest, most densely populated or politically challenged, including Afghanistan, Guinea and Nigeria. Despite constraints faced by health reformers everywhere, every country was able to share a story of accomplishment—defining how their case example was managed, what services were affected and ultimately how patients, staff, or the system overall, benefited. The reform themes ranged from those relating to policy, care coverage and governance; to quality, standards, accreditation and regulation; to the organization of care; to safety, workforce and resources; to technology and IT; through to practical ways in which stakeholders forged collaborations and partnerships to achieve mutual aims. Common factors linked to success included the ‘acorn-to-oak tree’ principle (a small scale initiative can lead to system-wide reforms); the ‘data-to-information-to-intelligence’ principle (the role of IT and data are becoming more critical for delivering efficient and appropriate care, but must be converted into useful intelligence); the ‘many-hands’ principle (concerted action between stakeholders is key); and the ‘patient-as-the-pre-eminent-player’ principle (placing patients at the centre of reform designs is critical for success).

Keywords: international health reform, healthcare system, appropriate healthcare, patient-centred care, quality improvement, patient safety

Introduction

Healthcare reform inherently involves policy-initiated changes to improve targeted aspects of healthcare services. It can encompass macro, meso or micro levels of the system, and one or many settings. Its goals include achieving efficiencies, implementing new or revamped quality and safety practices, acquiring and applying advanced technology to improve care, and ensuring the right information is available to enable providers and care recipients to make the most informed, clinically appropriate and cost-effective healthcare decisions. At its most basic, reform is about deciding which systems and processes to keep and which to alter or substitute to bring about improved care to patients.

Said that way, reform sounds relatively simple: plan change, implement it and thereby deliver improvements. In practice, however, reform is not linear, but rich in complexity [1]. It presents many challenges to its proponents. As Nobel-prizewinning psychologist, Daniel Kahneman once indicated: ‘Reforms always create winners and losers … and the losers will always fight harder than the winners’ [2].

Complex systems are path-dependent, exhibit various forms of inertia [3] and their progress with change is often painfully slow. Sometimes change is impossible to predict accurately, or at all. Whether reformers are trying to enact minor tweaks, more concerted adaptations or major transformations, they invariably need technical or technological support, expert input and cooperation between parties to realize the envisaged change. Every change involves politics, cultural shifts, the mobilization of power and the exercise of resource reallocations. Some reforms are highly specific to provider types, organizations, regions or countries, while others are intended to be universal, and designed to be taken up virtually everywhere. Explaining whether or the extent to which a reform initiative has been successful is dependent on the appraiser, and his or her perspectives, ideology or interests. Reforms are usually multi-faceted and influenced by a mix of factors that are woven into a country's fabric, including its economy, culture, geography, socioeconomic circumstances, population size, and its political framework and relative stability or instability, to name a few key variables.

A focus on success

Our recently edited compendium ‘Health Systems Improvement Across the Globe: Success Stories from 60 Countries’ [4] takes on the task of examining health reform achievement narratives drawing on data from 60 countries, and offering a unique global perspective. It seeks to understand how different health systems, sectors or sub-sectors experience success with health reform. Taken together, the book highlights a variety of reform initiatives, and the impact that they are having, or have had, within the included countries. It helps define which are the success factors, and hones in on the key lessons learnt from the cases themselves. The chapters consider how to apply the value of the case-successes to other initiatives within the originating country, and how these might be spread across other healthcare systems.

This is book number two in a series focused on health reform from various standpoints. It follows ‘Healthcare Reform, Quality and Safety: Perspectives, Participants, Partnership and Prospects in 30 Countries’ [5, 6]. The first book explored national-level challenges to enhancement and transformation initiatives in a selection of health systems, and the relationship of those initiatives to the improvement of quality of care and safety to patients at various levels in each system.

The newly released book shifts attention away from the many challenges faced by healthcare reformers, and instead, acknowledges their success stories. It thus presents a positive perspective, one that is rare in today's scholarly literature, which typically tends to view a good news story as no real news at all. Criticism, and a problem-oriented focus, permeate most academic books, articles and reports. Taken together, the book provides information on the plurality and multi-dimensionality of reforms, and an array of accomplishments that are the result of considerable efforts to improve care across health systems. It is based on several critical premises: that every health system, no matter how resource-constrained, has a success story to tell; that improvement comes in many guises; and that strategically important reforms can, and in fact do, prevail, often overcoming resource and logistical constraints, or political and cultural barriers.

Over 161 contributing authors in the 60 countries, experts on the topics they presented, were set three key tasks for the presentation of their story. First, they chose an exemplar of success, and then analysed their case, carefully considering its impact on their healthcare system, or the care it provides, or both. Second, armed with their case, authors identified the main lessons learnt for the benefit of others interested in transferring this information to their own healthcare systems. Third, they advanced recommendations based on their assessment of the prospects for future success; that is, they defined what could be done elsewhere to apply, build on or improve upon their defined success story. The answers to these questions shaped the weft and weave of the stories that make up the chapters of this book.

The book does more, however, than simply share these success stories and reflect on their capacity for take-up elsewhere. It provides deep and powerful insights into what reformers in other countries can do to emulate the accomplishments outlined by the reporting teams of authors, who hail from all manner of health systems and settings. Let us turn to what is at the core of these insights.

A global reform journey

We live in a complex, politically challenging and worrying world. There are problems in reporting even something as seemingly simple as how many countries there are. According to the UN, there are 206 states in the world. Of these 193 are member states, two are observer states (The Vatican and Palestine) and 11 are classified as ‘other’ or ‘disputed’ states. Despite that challenge, of these 206 states, 60 contributed a chapter to this book, accounting for almost one third of all countries, and many major ones. The fact that we were able to gather such a large number of chapter writers is a result of intense efforts to create a network of internationally regarded experts over half a decade. It is a pleasing outcome, as publications within the health reform genre typically focus on problems in wealthy countries (e.g. those in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD]) and tend not to include stories of those resource-constrained or politically fragile countries, which face unique challenges, yet paradoxically may have many lessons to share.

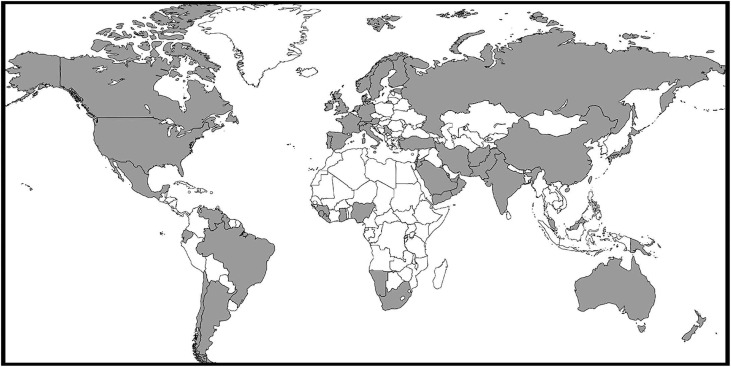

The range, depth and breadth of the stories within this book reflect the diversity of their countries of origin. There are 5 low income, 22 middle income, 35 high income and 1 currently unclassified healthcare system. They cover health systems that provide care to over two-thirds of the world's 7.4 billion people. The contributing countries are spread over 85.8 million square kilometres of the earth (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

A map of the countries which contributed to ‘Health Systems Improvement Across the Globe–Success Stories from 60 Countries’ (contributing countries are shaded). Source: https://mapchart.net/

The book is structured to align with the World Health Organisation (WHO) regions [7], and includes details on population size, demographic and socioeconomic status, life expectancy and mortality rates, density of health workforce and health expenditure of each country. This provides valuable context of the health landscape across which each health reform initiative has had to navigate.

The meaning of success

There are many things we do not ‘know’, and other things we do not ‘do well’. Then there are things we do not know how to do well. We call these wicked problems [8, 9]. They are typically thought of as complex, hard to solve, hard even to tame. There is no right way to tackle them, and no guarantee of success. Health reform is like that: it is challenging to do, and tough to make gains. Each country's target story, and successful outcomes, varied greatly from others (Appendix A). Some authors focused on how a specific populations’ or groups’ health improved, for example organ donor recipients in Spain, neglected or abused children in Serbia and stroke patients in Austria. Others such as the authors of the Taiwan, Oman and Israel chapters addressed how care was enhanced or distributed through mechanisms including better data and IT infrastructure, each taking a different perspective on how this was accomplished in their particular setting.

The effects of implementing accreditation, performance management programs and quality improvement systems was a popular theme in multiple success stories, although every story was unique in its tenor, focus and lessons learned. In the United States of America, success was found through improvements of safety systems in surgical care; in Jordan, enhanced accreditation and regulatory standards were identified; and in Namibia, a country with a multitude of complex challenges, success was nurtured through the implementation of quality management systems.

Procedural change initiatives such as those implemented by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in the English National Health Service (NHS) helped ensure payers have access to evidence-based data to inform decision-making and reduce geographical variation in the allocation of scarce resources. Taking a different tack, medical training initiatives in Malta helped curb the brain drain of medical staff from that country.

How adaptable are these and all the other case examples? One clear example of transferability in action was that of the ‘Between the Flags’ program from Australia [10]. This system-wide initiative aimed to optimize responses to patient emergencies with the most appropriate medical resources. The program implemented colour coded, standardized observational charts with clinician prompts for escalation as a patient deteriorates. It evolved from an earlier program that set the course for change by embedding medical emergency teams in hospitals. The influence of this program is evidenced in Qatar where the ‘Early Warning System’ reform success story was based on the lessons originally taken, and adapted, from the Australian initiative.

Another example is the superb summary of the concerted international efforts in West Africa (Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone) to combat Ebola. There is much to learn from this chapter, in which WHO experts Shamsuzzoha Syed and Ed Kelley describe ways of building resilience in vulnerable societies when disaster strikes.

Thinking across the plethora of case examples, a few ubiquitous determinants of future success emerged. Repeatedly, some level of seed funding (or in some cases, significant commitment of resources) is involved. In many cases, a champion or, more frequently, a collaboration or critical mass of people, believes in and catalyzes the change. Most successful exemplars reported that they built momentum over time, and rarely achieved their objectives quickly or decisively. Perseverance is an attribute of success, and reform is a journey not a destination. Political will in actively promoting an improvement project, or just standing behind the initiative in order to get a reform result, is also a ubiquitous feature.

There are other common factors we found, time and again, across the case studies. Successful reform is often grounded in an environment where the appropriate stakeholders are engaged, are effectively communicating and collaborating, and where governance, leadership and accountability are assigned in the right places. These foundations are critical, and their significance appears to outrank the more obvious constraints which can drag down reform initiatives in the muddied, hard-to-change political and socioeconomic contexts which persist in many health systems, rich and poor alike.

Another prevalent theme in reform measures is the involvement of, or focus on, patients and their needs. The story from Wales describes how shared decision-making between patients and physicians can lead to increased patient satisfaction and in some cases more effective clinical care even during times of austerity. In Scotland, the aphoristic premise of ‘Working in partnership with people, rather than doing things to people’ has helped stimulate concerted efforts to promote collaboration between the country's government, its citizens, and its patients and healthcare professionals, encouraging multiple stakeholders to work together towards improving healthcare delivery.

A major message is that gains from reform measures cannot be linked to any one factor alone. Rather, the joint success factors are often interlinked, and thus attribution is always tough to untangle. It is hard to say which variables are more critical than others, as many feed into success. For example, it is not completely possible to identify what was most helpful when introducing technical enhancements such as those of IT (as in Finland, Oman or Pakistan), accreditation (as in Jordan, Afghanistan or Turkey), quality improvement systems (as in Brazil, Namibia or Russia) or new policy initiatives (as in Argentina, Rwanda or Iran). That said, change always needs groups of skilled, proactive participants who can make or break the initiative. Indeed, a culture that is sufficiently engaged and receptive, and willing to drive or simply embrace the implementation of the targeted change, is a perennial precondition to success.

Meta-lessons

An emergent meta-lesson from the 60 stories of reform is obvious, but telling: each country was able to document a successful or potentially successful initiative, regardless of their economic status or political situation. Even Afghanistan, which has been at war since 2001, or Papua New Guinea, which has recently gone backwards on the WHO's development indicators, or Jordan, whose health system is going through significant resource pressures and a refugee crisis, could muster a compelling case articulating an inspiring achievement.

Another meta-message centers on the extent of the change people try to enable. With time and focused effort, small scale, purpose-designed, local initiatives can and often do lead to system-wide improvements. For example, universal healthcare, a streamlined policy landscape, or more integrated care delivery are big picture goals for most countries. To make progress in a journey of success on these broad-based, and often daunting issues, countries might start small, achieve some early goals, and build momentum. By funding projects that are initially modest in scale, and piloting or testing the improvement initiatives, reformers can help shape the environment, preparing the ground for later implementation of measures that can lead to systems-wide enhancements. We think of this as the ‘acorn-to-oak tree’ principle of reform, and it is exemplified by chapters from Iran, New Zealand, Estonia, Ecuador and Fiji.

Another overarching lesson learned is that the method by which information is captured, analysed and communicated throughout a systems change is fundamental. No reform can stick unless stakeholders are informed, information is exchanged and communication occurs at the right time, in the right place, between the right people, through the right medium. In the modern world, this interaction is mediated by technology: the integrated use of IT, effective data capture and transmission, and accessible databases and decision support tools. We call this the ‘data-to-information-to-intelligence’ reform principle. It is becoming increasingly essential to the provision of high quality and safe care, as the authors from Chile, the United Arab Emirates, South Africa, Ireland, China and Italy note.

The book also teaches that implementation predicated on relationships between key stakeholders, using evidence on which to base decisions, and adopting clear principles of reform design provide a strong opportunity to deliver system improvements, as shown by Mexico, Venezuela, The Gulf States (Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates), Nigeria, Ghana, Portugal and Lebanon. For us, such partnership approaches exemplify what we have come to call the ‘many-hands’ principle of reform.

A final meta-lesson is the most crucial of all: placing the patient, their experience and well-being, at the centre of an initiative, anchors it to the point of the whole reform enterprise, whichever country is involved; Northern Ireland, Germany, Denmark, Guyana, Hong Kong and Malaysia, illuminate this point. We label it the ‘patient-as-the-pre-eminent-player’ reform principle. That is the obvious, bedrock test for any reform: does it make care better for patients?

Conclusion

The countries included in the book were diverse. Each of them is at a different stage in a health reform journey; a journey which is, in turn, embedded in and emerging from a unique social, economic, geographic and political environment. Each and every included country provided fascinating details of a successful reform initiative, irrespective of the constraints they faced.

Each case discussed ways to overcome challenges to realize success, with examples drawn from the wealthiest countries, those in the middle-range of income, and the poorest. Indeed, wealth does not guarantee immediate investments in support of success. Japan, France, Norway and Sweden, by way of example, have amongst the strongest indicators for health (e.g. the highest life expectancy rates and lowest maternal and infant mortality rates), yet, while they are doing well in meeting such targets, their health systems are facing increasing challenges that include an aging population and rising prevalence of chronic disease, both of which place a cost burden on them of considerable magnitude [11].

A penultimate message from this compendium is that just as challenges continue to evolve, so too do the methods of reform. In this context, it will serve us well to remember that one successful case study if done well can provide the motivation for other successes; but if we aggregate the knowledge from them, as we do in this book, we can provide a platform of information on which reformers and improvers everywhere can build much better health systems for the future.

Success is a good news story, and these are stories that need to be shared. To report success, of course, is one thing. Transferring the lessons learnt to other settings is another. But if we are to make systems improvements, enhance services and provide better care to patients, such stories must be both shared and translated.

Acknowledgements

We would like to sincerely thank all chapter authors: Afghanistan: Omarzaman Sayedi, Edward Chappy, Lauren Archer, Nafiullah Pirzad; Argentina: Hugo Arce, Ezequiel García-Elorrio, Viviana Rodríguez; Australia: Jeffrey Braithwaite, Ken Hillman, Charles Pain, Clifford F. Hughes; Austria: Maria M. Hofmarcher-Holzhacker, Judit Simon, Gerald Haidinger; Brazil: Claudia Maria Travassos, Victor Grabois, José Carvalho de Noronha; Canada: Jonathan I. Mitchell, Qendresa Hasanaj, Hélène Sabourin, Danielle Dorschner, Stephanie Carpenter, Toby Yan, Wendy Nicklin, G. Ross Baker, John van Aerde, Sarah Boucaud; Chile: Marcos Vergara Iturriaga, Leonel Valdivia; China: Hao Zheng; Denmark: Janne Lehmann Knudsen, Carsten Engel, Jesper Eriksen; Ecuador: Jonás Gonseth, Maria Cecilia Acuña; England: Martin Powell, Russell Mannion; Estonia: Kaja Põlluste, Ruth Kalda, Margus Lember; Fiji: Jalal Mohammed, Nicola North, Toni Ashton; Finland: Persephone Doupi, Jorma Komulainen, Minna Kaila, Ilkka Kunnamo; France: René Amalberti, Thomas le Ludec; Germany: Oliver Groene, Holger Pfaff, Helmut Hildebrandt; Ghana: Sodzi Sodzi-Tettey, Richard Selormey, Cynthia Bannerman; The Gulf States: The Gulf Health Council for Cooperation Council States; Guyana: William Adu-Krow, Vishwa Mahadeo, Vasha Elizabeth Bachan, Melissa Ramdeen; Hong Kong: Hong Fung, Eliza Lai-Yi Wong, Patsy Yuen-Kwan Chau, Eng-Kiong Yeoh; India: Girdhar Gyani; Introduction, and Discussion and Conclusion: Jeffrey Braithwaite, Russell Mannion, Yukihiro Matsuyama, Paul Shekelle, Stuart Whittaker, Samir Al-Adawi, Kristiana Ludlow, Wendy James; Iran: Ali Mohammad Mosadeghrad; Ireland: Feargal McGroarty; Israel: Eyal Zimlichman; Italy: Americo Cicchetti, Silvia Coretti, Valentina Iacopino, Simona Montilla, Entela Xoxi, Luca Pani; Japan: Yukihiro Matsuyama; Jordan: Salma Jaouni Araj, Edward Chappy; Lebanon: Nasser Yassin, Maysa Baroud, Reem Talhouk, Sandra Mesmar, Sara Kaddoura; Malaysia: Ravindran Jegasothy, Ravichandran Jeganathan, Safurah Jaafar; Malta: Sandra C. Buttigieg, Kenneth Grech, Natasha Azzopardi-Muscat; Mexico: Enrique Ruelas, Octavio Gómez-Dantés; Namibia: Apollo Basenero, Christine S. Gordon, Ndapewa Hamunime, Joshua Bardfield, Bruce Agins; The Netherlands: Roland Bal, Cordula Wagner; New Zealand: Jacqueline Cumming, Jonathon Gray, Lesley Middleton, Haidee Davis, Geraint Martin, Patricia Hayward; Nigeria: Emmanuel Aiyenigba; Northern Ireland: Levette Lamb, Denise Boulter, Ann Hamilton, Gavin G. Lavery; Norway: Ellen Tveter Deilkås, Geir Bukholm, Ånen Ringard; Oman: Ahmed Al-Mandhari, Abdullah Al-Raqadi, Badar Awladthani; Pakistan: Syed Shahabuddin, Usman Iqbal; Papua New Guinea: Paulinus Lingani Ncube Sikosana, Pieter Johannes van Maaren; Portugal: Paulo Sousa, José-Artur Paiva; Preface: Clifford F. Hughes, Wendy Nicklin; Qatar: David Vaughan, Mylai Guerro, Yousuf Khalid Al Maslamani, Charles Pain; Russia: Vasiliy V. Vlassov, Alexander L. Lindenbraten; Rwanda: Roger Bayingana, Edward Chappy; Scotland: Andrew Thompson, David Steel; Serbia: Mirjana Živković Šulović, Ivan Ivanovic, Milena Vasic; South Africa: Lizo Mazwai, Grace Labadarios, Bafana Msibi; Spain: Rafael Matesanz, Elisabeth Coll Torres, Rosa Suñol; Sweden: John Øvretveit, Mats Brommels; Switzerland: Anthony Staines, Patricia Albisetti, Paula Bezzola; Taiwan: Yu-Chuan (Jack) Li, Wui-Chiang Lee, Min-Huei Hsu, Usman Iqbal; Turkey: Mustafa Berktaş, İbrahim H. Kayral; the United Arab Emirates: Subashnie Devkaran; United States of America: Amy Showen, Melinda Maggard-Gibbons; Venezuela: Pedro Delgado, Luis Azpurua; Wales: Adrian Edwards; West Africa: Shamsuzzoha B. Syed, Edward T. Kelley; Yemen: Khaled Al-Surimi.

Appendix A: Summary of success stories from 60 countries—themes and topics

| Primary Theme | Region | Country | Topic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Policy, Coverage and Governance | The Americas | Argentina | Government legislation and non-government initiatives on quality and safety |

| Chile | Creating symbolic capital and institutional motivation for success | ||

| Mexico | Monitoring and evaluation system for health reform | ||

| Venezuela | Mision Barrio Adentro (‘Inside the Ghetto Mission’) national primary care program | ||

| Africa | Rwanda | Community-based health insurance | |

| Europe | Serbia | Child abuse and neglect | |

| Eastern Mediterranean | Iran | The wide-ranging reforms via the Health Transformation plan | |

| The United Arab Emirates | Improving quality through a single payment system | ||

| South-East Asia and the Western Pacific | India | Public-private partnership to increase safety and affordability of care | |

| Japan | Improving health insurance | ||

| Quality | The Americas | Brazil | Quality improvement initiatives |

| Africa | Namibia | A national quality management model | |

| Europe | Russia | Legislative improvements to improve healthcare quality | |

| Eastern Mediterranean | Yemen | Improvement of basic health services in Yemen: A successful Donor-driven Improvement Initiative | |

| South-East Asia and the Western Pacific | New Zealand | Ko Awatea organization for innovation and quality improvement | |

| Standards, Accreditation and Regulation | The Americas | Canada | Improving stroke outcomes through accreditation |

| Africa | South Africa | Regulation of healthcare establishments via a juristic body | |

| Europe | Turkey | National healthcare accreditation | |

| Eastern Mediterranean | Afghanistan | Minimum required standards (MRS) | |

| Jordan | Healthcare accreditation council | ||

| Organizing Care | The Americas | Ecuador | Improving hospital management |

| Guyana | Establishing clinics for elderly care | ||

| Africa | Nigeria | A responsive health delivery system | |

| West Africa (Guinea, Liberia, Sierra Leone) | Organizing care at the macro level to tackle Ebola | ||

| Europe | Austria | Stroke-units as a mechanism to improve health outcomes | |

| Denmark | Pathways for cancer patients | ||

| Estonia | Reform in primary healthcare | ||

| Germany | ‘Healthy Kinzigtal’ population-based healthcare system | ||

| Northern Ireland | Improving maternal and paediatric care | ||

| Spain | Organ donation and transplantation | ||

| Wales | Shared decision-making in practice and strategic improvements | ||

| Eastern Mediterranean | The Gulf States (Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates) | Procuring pharmaceuticals and medical supplies from the Gulf Cooperation Council countries | |

| Qatar | Qatar Early Warning System (QEWS) for deteriorating patients | ||

| South-East Asia and the Western Pacific | Australia | ‘Between the flags’ rapid response system in emergency care | |

| Fiji | Strengthening primary care | ||

| Hong Kong | Care for elderly patients after hospital discharge | ||

| Malaysia | A journey to enhance maternal health | ||

| Papua New Guinea | Establishing the provincial Health Authority | ||

| Safety | The Americas | The United States of America | Improving safety in surgical care |

| Europe | France | Care-centred approach: Increasing patients’ feelings of safety | |

| The Netherlands | ‘Prevent Harm, Work Safely’ program | ||

| Norway | Standardization of measuring and monitoring adverse events | ||

| Workforce and Resources | Africa | Ghana | Arresting the medical brain drain |

| Europe | England | The role of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) | |

| Italy | Management of pharmaceutical innovation | ||

| Malta | Medical training and regulation | ||

| Technology and IT | Europe | Finland | eHealth in clinical practices |

| Ireland | Innovative treatment of hemophilia | ||

| Israel | Electronic health records and the health information exchange program | ||

| Sweden | Researching and learning from clinical data | ||

| Eastern Mediterranean | Oman | Al-Shifa electronic health record system | |

| Pakistan | Role allocation, accreditation and databases, e.g. cardiac surgery database | ||

| South-East Asia and the Western Pacific | China | Self-service in tertiary hospitals | |

| Taiwan | Improvements in information technology | ||

| Collaborations and Partnerships | Europe | Portugal | Reducing hospital-acquired infection |

| Scotland | Partnerships and collaborations promoting systems improvements | ||

| Switzerland | Collaborations to improve patient safety | ||

| Eastern Mediterranean | Lebanon | Social innovation and blood donations |

Funding

This work was supported by National Health and Medical Research Council [grant number 1054146 to J.B.].

References

- 1. Braithwaite J, Clay-Williams R, Nugus P et al. . Health care as a complex adaptive system In: Hollnagel E, Braithwaite J, Wear R (eds). Resilient Health Care. Farnham, Surrey, UK: Ashgate Publishing, 2013: 57–76. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lewis M. The Undoing Project: A Friendship That Changed Our Minds. London, UK: Allen Lane, 2017: 138. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Coiera E. Why system inertia makes health reform so difficult. BMJ 2011;342:d3693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Braithwaite J, Mannion R, Matsuyama Y et al. (eds). Health Systems Improvement Across the Globe: Success Stories from 60 Countries. Abingdon, UK: Taylor & Francis, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Braithwaite J, Matsuyama Y, Mannion R et al. (eds). Healthcare Reform, Quality and Safety: Perspectives, Participants, Partnerships and Prospects in 30 Countries. Farnham, Surrey, UK: Ashgate Publishing, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Braithwaite J, Matsuyama Y, Mannion R et al. . How to do better health reform: a snapshot of change and improvement initiatives in the health systems of 30 countries. Int J Qual Health Care 2017;28:843–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. World Health Organization , WHO regional offices, Switzerland: http://www.who.int/about/regions/en/ Accessed [7 April 2017].

- 8. Rittel HWJ, Webber MM. Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sci 1973;4:155–69. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Westbrook JI, Braithwaite J, Georgiou A et al. . Multimethod evaluation of information and communication technologies in health in the context of wicked problems and sociotechnical theory. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2007;14:746–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hughes C, Pain C, Braithwaite J et al. . ‘Between the flags’: implementing a rapid response system at scale. BMJ Qual Saf 2014;23:714–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Amalberti R, Nicklin W, Braithwaite J. Preparing national health systems to cope with the impending tsunami of ageing and its associated complexities. Towards more sustainable health care. Int J Qual Health Care 2016;28:412–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]