Abstract

ATP-sensitive potassium channels (KATP channels) link cell metabolism to electrical activity by controlling the cell membrane potential. They participate in many physiological processes but have a particularly important role in systemic glucose homeostasis by regulating hormone secretion from pancreatic islet cells. Glucose-induced closure of KATP channels is crucial for insulin secretion. Emerging data suggest that KATP channels also play a key part in glucagon secretion, although precisely how they do so remains controversial. This Review highlights the role of KATP channels in insulin and glucagon secretion. We discuss how KATP channels might contribute not only to the initiation of insulin release but also to the graded stimulation of insulin secretion that occurs with increasing glucose concentrations. The various hypotheses concerning the role of KATP channels in glucagon release are also reviewed. Furthermore, we illustrate how mutations in KATP channel genes can cause hyposecretion or hypersecretion of insulin, as in neonatal diabetes mellitus and congenital hyperinsulinism, and how defective metabolic regulation of the channel may underlie the hypoinsulinaemia and the hyperglucagonaemia that characterize type 2 diabetes mellitus. Finally, we outline how sulphonylureas, which inhibit KATP channels, stimulate insulin secretion in patients with neonatal diabetes mellitus or type 2 diabetes mellitus, and suggest their potential use to target the glucagon secretory defects found in diabetes mellitus.

Introduction

Whether you indulge in a large slice of chocolate cake or decide to fast for the day, the pancreatic islets of Langerhans ensure that the swings in your blood sugar level are not large. Each islet contains several types of endocrine cells, which have opposing roles in glucose homeostasis. Insulin, the only hormone to lower blood glucose concentration, is secreted by the β cells, which make up >60% of the islet: it stimulates glucose uptake and storage in liver, muscle and adipose tissue. Insufficient insulin secretion results in elevated blood glucose levels, a hallmark of diabetes mellitus. The α cells release glucagon, the body's principal plasma-glucose-elevating hormone. By increasing hepatic glucose production, glucagon prevents hypoglycaemia during fasting and exercise and provides glucose to brain and active muscles. Somatostatin, released from δ cells, inhibits both insulin and glucagon secretion.

Hormone secretion from all three cell types is triggered by action potential firing that leads to the influx of calcium ions (Ca2+) through voltage-gated Ca2+ channels and a rise in the intracellular Ca2+ concentration that activates secretory granule exocytosis. In β cells and δ cells, glucose metabolism elicits electrical activity and hormone secretion by closing ATP-sensitive potassium channels (KATP channels).1–4 Paradoxically, KATP channel closure seems to have the opposite effect in α cells, where genetic or pharmacological inactivation of the channel is associated with inhibition of secretion.5,6 This Review provides an introduction to the differing role of KATP channels in insulin and glucagon secretion and considers how defective KATP channel activity causes the hormonal abnormalities associated with diseases such as diabetes mellitus and hyperinsulinism.

Regulation of electrical activity

The KATP channel consists of four pore-forming Kir6.x sub-units and four regulatory sulphonylurea receptor (SUR) subunits,2 which in islet cells constitute Kir6.2 (encoded by KCNJ11) and SUR1 (encoded by ABCC8).7–9 The hallmark of the KATP channel is its inhibition by intracellular ATP, which binds to Kir6.2 to cause channel closure.10 Conversely, interaction of intracellular MgATP (the active form of ATP) and MgADP with SUR1 stimulates channel opening.11–13 Modulation by adenine nucleotides means that KATP channel activity is, in turn, regulated by cell metabolism. The fact that magnesium ions (Mg2+) are not required for ATP (or ADP) binding to Kir6.2 but are needed for binding to SUR1 reflects the different structure of the binding sites on these proteins; this property can also be used experimentally to distinguish between nucleotide effects on Kir6.2 and SUR1. Drug binding to SUR1 also regulates channel activity: KATP channel openers, such as diazoxide, stimulate channel opening whereas sulphonylurea drugs, such as tolbutamide and glibenclamide, induce channel closure.14–16

KATP channels link metabolism to cellular electrical activity by regulating the membrane potential. Gating of the KATP channel is both voltage-independent and time-independent, so that KATP channel activity results in an ATP-gated leak current.17 The effect of this leak current on the electrical activity of the cell depends on the relative magnitudes of the KATP current and other, depolarizing membrane currents. When the KATP current dominates, the membrane will hyperpolarize, switching off electrical activity. Conversely, if inward currents dominate—as is the case when KATP channels are almost completely closed—membrane depolarization occurs. If this depolarization is sufficient, electrical activity will be initiated.18 It is important to recognize that when the electrical resistance of the membrane is very high—as when most KATP channels are shut—even a tiny change in current can have a large effect on the membrane potential.

Role of the KATP channel in β cells

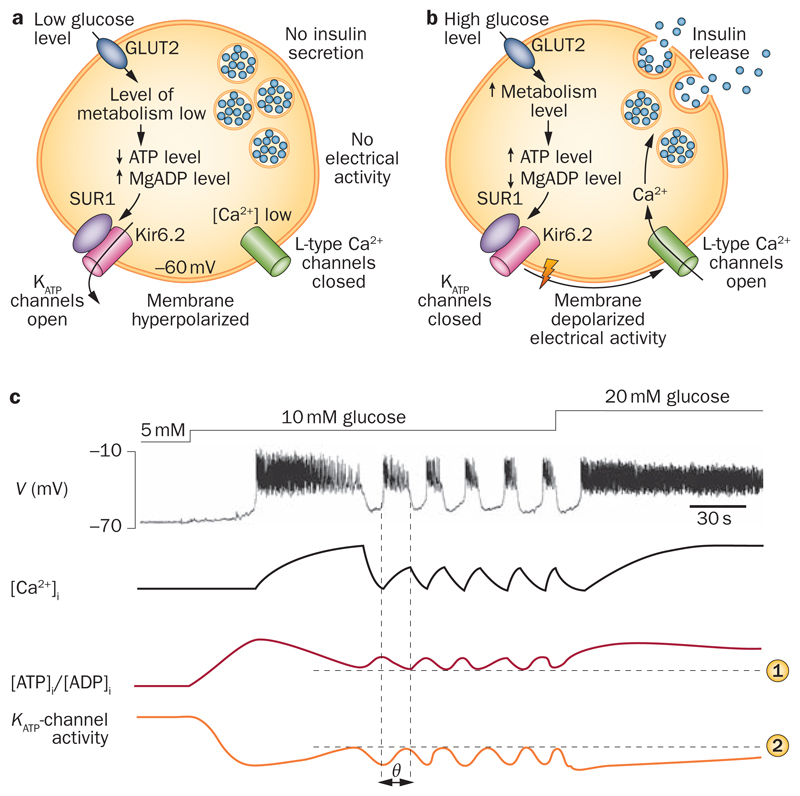

The KATP channel is essential for glucose-stimulated insulin secretion.1 At glucose concentrations that do not stimulate insulin secretion, the ambient level of intracellular ATP ensures that KATP channel activity is high enough to keep the membrane hyperpolarized, preventing electrical activity and insulin secretion (Figure 1). KATP channel closure in response to metabolically generated ATP reduces the KATP current so that background inward currents now make a greater contribution to the membrane potential. As a consequence, the membrane depolarizes and electrical activity is initiated if this depolarization exceeds the threshold for initiation of action potential firing—which in β cells lies between –60 mV and –50 mV.19

Figure 1. KATP channel modulation of β-cell electrical activity.

Insulin secretion is a | inhibited at low glucose concentrations and b | stimulated at high glucose levels. c | Schematic illustrating the changes in membrane potential (V), intracellular Ca2+ ([Ca2+]i), cytosolic [ATP]i/[ADP]i ratio and whole-cell KATP current produced by increasing glucose concentrations. At 5 mM glucose, KATP channels are active because of the low [ATP]i/[ADP]i ratio, which keeps the membrane hyperpolarized and prevents electrical activity. At 10 mM glucose, via stimulation of glucose metabolism, the [ATP]i/[ADP]i ratio increases, resulting in a reduced KATP current. When KATP channel activity is sufficiently low, the membrane depolarizes initiating electrical activity and Ca2+ influx. Elevation of [Ca2+]i activates ATP-consuming Ca2+-pumps, causing a fall in the [ATP]i/[ADP]i ratio, reactivation of KATP channels, membrane repolarization and temporary termination of electrical activity. Elevated [Ca2+]i also opens Ca2+-activated K+-channels, which contributes to the membrane repolarization (not shown). In the hyperpolarized state, Ca2+ influx ceases, [Ca2+]i returns to basal, ATP consumption falls, the [ATP]i/[ADP]i ratio is restored, KATP and Ca2+-activated K+ channels close and electrical activity is reinitiated. Horizontal lines indicate the fall in ATP ([ATP]i/[ADP]i) needed to activate KATP channels to the level (KATP channel activity) required to initiate repolarization of the burst. Thus, the oscillations in the [ATP]i/[ADP]i are phase shifted (θ) with respect to changes in intracellular Ca2+, KATP channel activity and action potential firing (vertical lines). At 20 mM glucose, ATP production is high enough to compensate for the increased ATP consumption. Consequently, the [ATP]i/[ADP]i ratio is maintained at a sufficiently high level to keep KATP channels closed, resulting in continuous electrical activity. Abbreviation: KATP channels, ATP-sensitive potassium channels.

High-threshold voltage-gated Ca2+ channels activate during the action potentials, and the associated Ca2+ influx triggers Ca2+-dependent exocytosis of insulin granules. L-type Ca2+ channels underlie the action potential in rodent β cells,20 but in humans P/Q-type Ca2+ channels are functionally more important.21 Unlike mouse β cells, human β cells also have a prominent T-type Ca2+ current that activates at voltages as negative as –60 mV and a voltage-gated Na+ current.21 These differences, together with the smaller KATP current (10% of that in mouse β cells), may explain why electrical activity and insulin secretion from human β cells are triggered at lower glucose concentrations than those from mouse β cells.22

At glucose concentrations between ~6 mM and 20 mM, electrical activity in mouse β cells consists of characteristic bursts of action potentials (lasting 5–15 s), which are superimposed on depolarized plateaux and separated by repolarized electrically silent intervals (5–20 s),23,24 as shown schematically in Figure 1. The duration of the bursts increases, and the interburst interval decreases, with increasing glucose concentration and eventually culminates in continuous electrical activity. β cells from other species also generate bursts, but these are less regular than those seen in the mouse, and different ion channels probably contribute to their generation. Although the bursts were first described ~45 years ago,25–28 their origin still remains a matter of debate. Thus, they have variously been attributed to oscillations in KATP channel activity,29,30 opening of small-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels,31 periodic activation of depolarizing currents,32 Ca2+ channel inactivation33 or cell–cell coupling.19,34

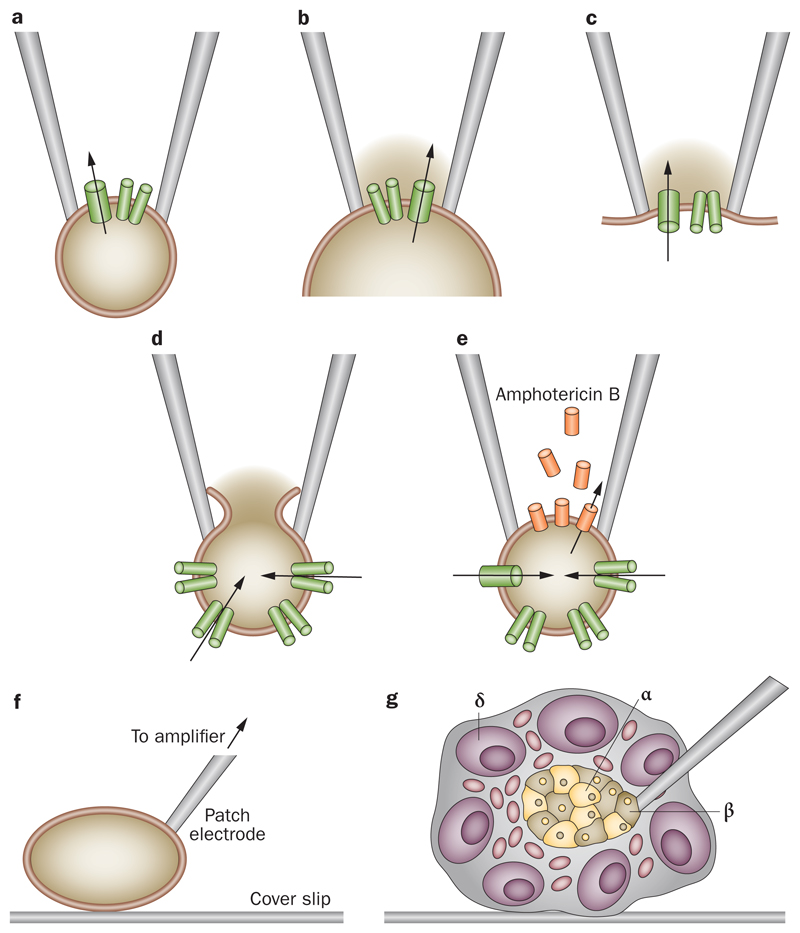

Many of the early patch-clamp studies of β cells were performed on isolated cells maintained in tissue culture, in which the rapid oscillatory electrical activity characteristic of β cells in freshly isolated intact islets23 is either absent and electrical activity is continuous, or it occurs on a timescale 10–20 times slower than that in intact islets.31,35 This finding suggests that β-cell isolation could lead to changes in channel density, channel regulation and/or cell–cell coupling. When the integrity of the islet is maintained, and electrical activity is recorded from β cells lying within the islet, normal bursting activity is recorded (Figure 1c). The various patch-clamp configurations, and how they can be used to study ion channel function, are illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Patch clamping enables the activity of one or more ion channels to be recorded from single cells or isolated membrane patches with high precision.

a | In the cell-attached configuration, the patch electrode is sealed to the surface of an intact cell, allowing channel activity in the patch of membrane under the electrode tip to be studied under physiological conditions. If the pipette is withdrawn from the cell surface, an excised membrane patch is produced, spanning the pipette tip, which has its b | intracellular surface (inside-out patch), or c | extracellular surface (outside-out patch) exposed to the bath solution. Inside-out patches are used to test the effects of intracellular modulators on channel activity (for example, ATP). The whole-cell configuration measures the summed activity of the many ion channels in the membrane of the whole cell. d | The standard whole-cell method is obtained by forming a cell-attached patch and then destroying the patch membrane with strong suction to gain electrical access to the cell interior. The intracellular solution then dialyses with that in the patch (so, for example, ATP is lost or the intracellular solution can be manipulated). e | The perforated patch method preserves cellular metabolism and intracellular second messenger systems by using a pore-forming antibiotic (such as amphotericin B) to provide electrical access to the cell interior. Parts a to e adapted from Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol., 54 (2), Ashcroft, F. M. & Rorsman, P. Electrophysiology of the pancreatic β-cell, 87143, ©1989, with permission from Elsevier.

Perforated patch measurements (which preserve cellular metabolism, Figure 2e) from β cells within intact islets reveal that each glucose-induced burst is associated with the gradual development of an outward current (termed Kslow),36,37 which is produced by activation of Ca2+-activated K+ channels (50%) and reactivation of KATP channels (50%).29 This current arises because Ca2+ influx through L-type Ca2+ channels, which open during the β-cell action potential, increases intracellular Ca2+ and thereby activates Ca2+-activated K+ channels. It also leads to increased ATP consumption by Ca2+-ATPases, and a fall in intracellular ATP levels,38–40 which partially reopens KATP channels closed by glucose metabolism. When Kslow has increased sufficiently to overcome the depolarizing influence of other ion channels, the burst terminates. Cessation of electrical activity results in a fall in intracellular Ca2+ levels, restoration of cellular ATP levels and thus closure of both Ca2+-activated K+-channels and KATP channels. As a result, the membrane depolarizes, triggering a second burst.19

The progressive lengthening of the bursts observed as glucose levels increase results from the reduced activation of KATP channels during electrical activity. This decline in KATP channel activity has been attributed to increased ATP generation (as a result of increased glucose metabolism), which enables more efficient buffering of ATP consumption by Ca2+-ATPases and further elevates the submembrane ATP concentration.19 Thus, KATP channel closure not only initiates electrical activity, but oscillations in the reactivation and closure of KATP channels shape the bursting behaviour of the β cell and underlie the graded increase in insulin secretion observed as glucose levels are elevated. This model also explains how sulphonylureas, which close KATP channels, convert oscillatory electrical activity into continuous action potential firing.41

Sulphonylureas have been used for almost 60 years to treat type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) because of their ability to close KATP channels and stimulate electrical activity and insulin secretion.15,42 These drugs act as partial antagonists, producing a maximum block of only ~60% if studied in excised membrane patches (Figure 2b) in the absence of intracellular Mg-nucleotides.43 When studied under whole-cell conditions (Figure 2d), however, they fully block channel activity.14 This is because sulphonylureas prevent channel activation by Mg-nucleotides that are present in the cell, but not (unless added) in the solution that perfuses the intracellular surface of an excised inside-out patch. As ATP inhibition of the channel is no longer antagonized by Mg-nucleotide activation, channel inhibition is enhanced.44,45 This complicated mechanism of drug action has an important consequence: it predicts that mutations that substantially decrease ATP inhibition will also reduce the maximal extent of sulphonylurea block of the whole-cell KATP current. It may also explain why some patients with severe activating KATP channel mutations (see below) cannot be treated with sulphonylureas.46

Role of the KATP channel in α cells

Glucagon is released from α cells in response to a fall in the blood glucose concentration or an increase in circulating levels of amino acids, fatty acids, hormones and neurotransmitters.47,48 Precisely how glucose regulates glucagon release remains controversial. At the heart of the debate is whether secretion is primarily controlled by an intrinsic mechanism (as in the β cell), or by an extrinsic mechanism that involves paracrine factors (such as hormones, metabolites and ions) released from neighbouring β cells or δ cells in response to changes in plasma glucose levels,47 or even from innervating nerve terminals.49 These hypotheses are not, of course, mutually exclusive. Furthermore, whatever mechanism(s) are involved, studies on islets from mice lacking KATP channels indicate that KATP channels have a key role.5,6,50 What is in question is whether regulation of KATP channel activity directly controls glucagon secretion (as it does insulin release) or if channel activity has an indirect, permissive role by setting the stage for other mechanisms that operate via changes in membrane conductance.

Candidates for a glucose-dependent extrinsic regulator of glucagon release include insulin,51 zinc52 and GABA,53 all of which are released from β cells when blood glucose levels rise and have been shown to inhibit α-cell electrical activity and glucagon secretion in isolated islets.54 Zinc, an activator of KATP channels,55 co-crystallizes with insulin and is co-released in response to glucose. However, it seems that zinc is not a physiological regulator of glucagon release, because mice lacking zinc in their insulin granules (owing to a β-cell-specific knockout of the zinc transporter ZnT8) show no defect in glucagon secretion.56 Somatostatin, released from δ cells in response to glucose elevation, may also contribute to the inhibitory action of glucose on glucagon secretion, as glucagon secretion in islets isolated from mice lacking somatostatin is enhanced and no longer regulated by glucose.57,58 Nevertheless, it remains possible that loss of somatostatin, or indeed ZnT8, may lead to compensatory changes that mask the normal physiological function of these proteins.

The fact that in both human and rodent islets, glucagon secretion is maximally inhibited by glucose concentrations with no or little stimulatory effect on insulin secretion59 and that glucose remains capable of inhibiting glucagon secretion in isolated islets (that is, when innervation has been severed)60 suggests that α cells do indeed possess an intrinsic glucose-sensing mechanism. The nature of this regulation remains obscure, but modulation of α-cell electrical activity is an obvious candidate.

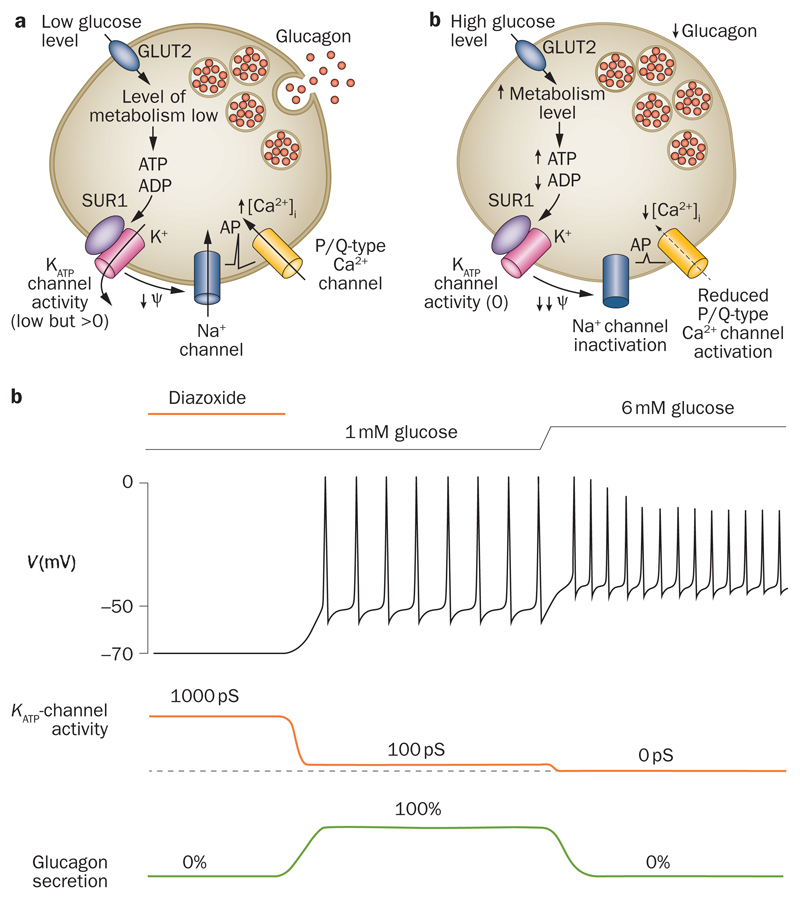

Unlike β cells, α cells are electrically active in the absence of glucose (Figure 3).61–64 This difference reflects the fact that the whole-cell KATP conductance measured in metabolically intact α cells exposed to glucose-free solution is much less than that in β cells (1–10%).65,66 However, the maximal KATP conductance (measured in the absence of intracellular ATP) is as high, or higher, in α cells than in β cells.67,68 The half-maximal concentration of MgATP required to inhibit the KATP current in β cells dialysed with MgATP is much higher (about sevenfold) than that observed in inside-out patches,69 probably due to intracellular generation of MgADP. Interestingly, it requires less ATP to block whole-cell KATP currents in α cells than in β cells,70 which may account for the smaller KATP currents observed in metabolically intact α cells than β cells.

Figure 3. KATP channel modulation of α-cell electrical activity.

a | Glucagon secretion is stimulated at low glucose levels and b | inhibited at high glucose levels. c | Schematic illustrating the changes in membrane potential (V), whole-cell KATP current and glucagon secretion produced by increasing glucose levels from 1 mM to 6 mM or by hyperactivation of the KATP channel using the KATP-channel activator diazoxide (far left). KATP channels are under strong tonic inhibition (99%) at low glucose levels, so that the membrane is depolarized sufficiently to elicit electrical activity, which consists of large-amplitude action potentials. Electrical activity is associated with activation of voltage-gated Na+ channels and voltage-gated Ca2+ channels, and Ca2+ influx through the latter triggers glucagon secretion. Increasing glucose levels to 6 mM closes KATP channels completely, further depolarizing the membrane. As in β cells, membrane depolarization increases action potential frequency. However, it also reduces α-cell spike amplitude, due to inactivation of voltage-gated Na+ channels, which leads to less activation of the P/Q-type Ca2+ channels linked to exocytosis and thus to reduced glucagon secretion. Abbreviation: KATP channels, ATP-sensitive potassium channels.

Whatever the reason that the KATP conductance in α cells exposed to low glucose concentrations is less than that in β cells, it ensures that the membrane is sufficiently depolarized for action potential firing to occur in the absence of glucose. The paradox is why further closure of KATP channels should reduce glucagon secretion but increase insulin release: surprisingly, tolbutamide inhibits glucagon secretion yet activates insulin release.60 Tolbutamide also results in α-cell membrane depolarization, a reduction in the peak amplitude of the action potential and, in some cases, even cessation of electrical activity. Our group have postulated that depolarization results in voltage-dependent inactivation of inward currents—most importantly sodium ion (Na+) currents—involved in action potential firing.60,71 This idea is supported by the fact that the Na+-channel blocker tetrodotoxin, which mimics the effect of tolbutamide on peak action potential amplitude, also inhibits glucagon release. Importantly, the reduction in action potential amplitude is expected to reduce Ca2+ entry through P/Q-type Ca2+ channels and thereby decrease glucagon release. From the voltage-dependence of exocytosis, it can be predicted that a 10–15 mV reduction in action potential peak voltage will produce a ~80% decrease in exocytosis.72

A key question is whether glucose exerts a tolbutamide-like effect on KATP channel activity and action potential firing. The fact that glucose inhibition of glucagon secretion is antagonized by low concentrations of diazoxide suggests this may be the case.60 Indeed, a small (10%) glucose-induced reduction in KATP channel activity has been observed in isolated rat α cells.73 Puzzlingly, in stark contrast to what is observed in intact islets, glucose stimulates electrical activity and secretion in isolated α cells. This difference may be because the whole-cell KATP conductance is greater in isolated α cells (0.45 nS/pF)73 than in α cells within intact islets (0.02 nS/pF; P. Rorsman, unpublished work). A possible explanation for this difference is that the loss of surrounding β cells may induce changes in α-cell gene expression, as was observed following β-cell destruction.74

A novel mechanism for extrinsic regulation of glucagon release has been proposed by Li et al. based on the finding that γ-hydroxybutyrate (GHB) is released from β cells in response to glucose metabolism and that GHB release is required for glucose-induced inhibition of glucagon release.75 Both the α-cell receptor for GHB and the molecular mechanism by which GHB prevents glucagon secretion are unknown, but an intriguing possibility is that GHB blocks KATP channels, either directly or indirectly.

Role of the KATP channel in exocytosis

Both Kir6.2 and SUR1 are found at high density in dense-core secretory granules of pancreatic β cells, α cells and δ cells76–79 but their role there is unclear and the type of dense-core granule involved is controversial. Several studies have provided evidence that SUR1 and Kir6.2 localize to the insulin secretory granules in β-cells.76–78 However, others have argued that KATP channel subunits are confined to non-insulin-containing dense-core granules.79

Why KATP channels are present in the granules is also unknown. Possibly, it might provide a route for trafficking KATP channels to or from the plasma membrane. Evidence also exists that KATP channels have a role in exocytosis. This idea is suggested by the fact that SUR1 binds to the exocytosis-regulating protein EPAC2.80 EPAC2 mediates the incretin effects of hormones such as glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1), and these effects are absent or reduced in mice lacking SUR1.81,82 One hypothesis suggests that by enhancing the ATP-sensitivity of KATP channels, EPAC2 facilitates KATP channel closure and membrane depolarization in response to incretins (such as GLP-1).83 Another idea is that SUR1 serves as a scaffold protein for EPAC2 and other proteins involved in exocytosis. Interactions of SUR1 with various exocytotic proteins, such as syntaxin-1A84 and the Ca2+ sensor piccolo80 have also been reported but their functional significance is not yet established.

In addition to the well-documented ability of sulphonylureas to close KATP channels (and so trigger islet-cell secretion), these drugs potentiate Ca2+-evoked exocytosis in both β cells85 and α cells86 by a mechanism that is downstream of KATP channel closure. However, KATP channels are not involved, as sulphonylureas still stimulate exocytosis in β cells from mice lacking SUR1.81 Although these findings have been contested,87 it has been discovered in the past few years that sulphonylureas bind directly to EPAC2.88 The extent to which this mechanism of drug action is of therapeutic significance remains unclear and, in any case, is dependent on sulphonylurea-induced membrane depolarization and Ca2+ entry.

Effects of KATP channel mutations

Neonatal diabetes mellitus

Gain-of-function mutations in the genes encoding either Kir6.2 (KCNJ11) or SUR1 (ABCC8) cause neonatal diabetes mellitus (NDM), a rare monogenic form of diabetes mellitus that usually presents within the first 6–9 months of life.89–92 The disease may be permanent or follow a remitting–relapsing time course. The reduced insulin secretion causes not only diabetes mellitus but also intrauterine growth retardation and a low birth weight. Because KATP channels are expressed in multiple tissues, around 20% of patients also exhibit neurological symptoms, such as mental and motor developmental delay, muscle hypotonia, hyperactivity and, in rare cases, epilepsy.90 Expression of a human NDM mutation (Kir6.2-Val59Met) in mice indicates that hypotonia results from impaired neuronal regulation of muscles, not from enhanced KATP channel activity in skeletal muscle.93

Multiple mutations in Kir6.2 and SUR1 that cause NDM have been studied biophysically.46,94–98 All increase the KATP current, either by reducing the ability of ATP to block the channel or by enhancing Mg-nucleotide stimulation. The increased KATP current prevents β-cell depolarization in response to glucose metabolism and impairs insulin secretion. Mice in which activating KATP channel mutations are expressed specifically in the β cell show severe loss of glucose-induced insulin secretion and diabetes mellitus.99–101 However, sulphonylureas, which close the open KATP channels, remain effective secretagogues. In general, those mutations that produce the greatest reduction in ATP sensitivity are associated with the most severe clinical phenotype.95

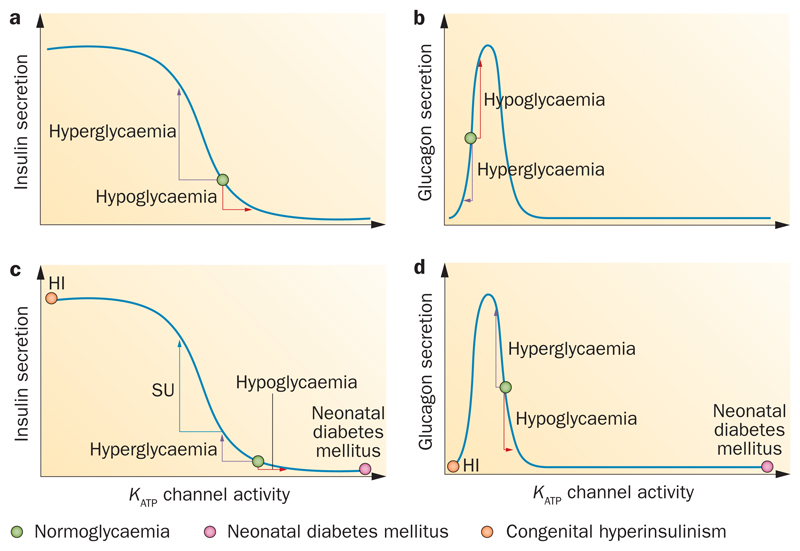

The effect of Kir6.2 and SUR1 mutations on glucagon secretion has received less attention. Nevertheless, one might predict that the effect would resemble that of diazoxide;60 in other words, severe mutations that cause a large increase in KATP conductance would be expected to inhibit glucagon secretion whereas those that produce a small increase in KATP current would stimulate glucagon release (Figure 4b,c).

Figure 4. Relationship between KATP channel activity and hormone release.

a | Sigmoidal relationship between β-cell KATP channel activity and insulin release. The green circle indicates channel activity at normal glycaemic levels in humans (~4–5 mM), where insulin secretion is slightly stimulated. Hyperglycaemia decreases KATP channel activity and stimulates insulin secretion. Hypoglycaemia increases KATP channel activity and inhibits insulin release. b | Bell-shaped relationship between α-cell KATP channel activity and glucagon release. Hyperglycaemia decreases KATP channel activity and inhibits glucagon secretion. Hypoglycaemia increases KATP channel activity and stimulates glucagon release. c | In β cells from patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), KATP channel activity is enhanced (either because of impaired metabolism or activating KATP channel variants or mutations). Hypoglycaemia supresses insulin secretion further. Hyperglycaemia increases insulin secretion but not as much as in nondiabetic β cells.140 Closure of KATP channels by sulphonylureas (SU) reduces channel activity at normal glycaemic levels and so boosts insulin secretion in both normoglycaemia and hypoglycaemia. The pink circle shows that in neonatal diabetes mellitus (NDM) KATP channel activity is so much enhanced that insulin secretion is abolished. The orange circle shows that in congenital hyperinsulinism (HI) there is little or no KATP channel activity, which causes persistent insulin secretion. d | In α cells from patients with T2DM, KATP channel activity is enhanced. Because of the bell-shaped relationship, reduced KATP channel activity in response to hyperglycaemia leads to increased glucagon secretion whereas hypoglycaemia causes reduced glucagon secretion. The orange circle illustrates the situation in severe HI and the pink circle in NDM. Abbreviation: KATP channels, ATP-sensitive potassium channels.

Prior to the discovery that KATP channel mutations could cause NDM, all patients with NDM were treated with insulin. Now, >90% of patients with NDM have switched to sulphonylurea therapy,102,103 which substantially improves their glucose homeostasis and reduces the risk of diabetic complications.102,104 Interestingly, patients with NDM usually require a much higher sulphonylurea dose (relative to body weight) than patients with T2DM. A lower sensitivity of the mutant KATP channel to sulphonylureas,46,99 or a higher open probability at ambient glucose levels, may contribute to the need for a higher dose. The sulphonylurea dose required also often declines with time after the onset of therapy, which suggests that β-cell mass or function may gradually improve when glucose homeostasis and/or normal KATP channel activity is restored. Fascinatingly, in a subset of mice expressing a β-cell-specific activating KATP channel mutation, early sulphonylurea treatment led to permanent remission of diabetes mellitus.105 To what extent this might be the case in humans is unknown. Sulphonylurea therapy might also restore normal function of glucagon-secreting α cells by bringing the KATP-channel activity in α cells into a range in which paracrine factors and circulating hormones become operational.

Congenital hyperinsulinism

Loss-of-function mutations in Kir6.2 or SUR1 result in congenital hyperinsulinism (HI), which is characterized by persistent and unregulated insulin secretion despite low blood glucose levels.92,106–109 The disease usually presents soon after birth as life-threatening hypoglycaemia. Strong suppression of glucagon secretion and of counter-regulation during hypoglycaemia also occur.110

Histologically, HI may be diffuse or focal. In diffuse HI, β cells in all islets are affected, whereas in focal HI, affected islets are confined to a small region of the pancreas. Focal HI usually occurs when the patient carries a recessive mutation in the paternal allele and locally loses the (normal) maternal allele by somatic deletion. Focal HI is treated by identification of the affected region of the pancreas using 18F-dihydroxyphenylalanine PET (18F-DOPA PET) scanning, followed by its surgical excision, and this treatment results in a cure.111,112 Diffuse HI is usually inherited recessively, but dominant mutations, which cause a less severe phenotype, have also been identified.108 The disease is sometimes treatable by KATP channel openers, such as diazoxide, but most cases require near total pancreatectomy. Interestingly, patients with dominant HI who do not undergo pancreatectomy may develop diabetes mellitus in later life.108,109

Patch-clamp studies have shown that β cells obtained from resected pancreases of patients with congenital HI have few or no functional KATP channels,113 This may be due to lack of KATP channels in the plasma membrane (by affecting protein expression, maturation, assembly or trafficking) or the loss of Mg-nucleotide activation. The resulting reduction in KATP channel activity explains why β cells are depolarized and show increased intracellular calcium and insulin secretion, even at low glucose levels. Glucose elevation is able to cause a further modest increase in insulin secretion,114 presumably via its effect on metabolic amplifying pathways that lie downstream of KATP channel closure.115

A major puzzle in studies of congenital HI is why mouse models do not recapitulate the human disease, even when the identical mutation is involved.116 In mice, loss of Kir6.2 or SUR1 does not cause sustained hypoglycaemia—rather, blood glucose levels normalize within a few days of birth, and in later life animals develop glucose intolerance.117,118 In addition, whereas heterozygous Kcnj11 and Abcc8 knockout mice do show mild HI and improved glucose tolerance,119 except for a few rare dominant mutations in humans, most people with heterozygous mutations are nonsymptomatic. Why these differences occur is still unclear.

Insulin secretion from islets isolated from patients with congenital HI and mice lacking SUR1 also shows some differences.114 A further complication is that freshly isolated islets from mice lacking SUR1 behave differently from those that have been cultured overnight.120 It is also important to remember that mouse and human islets are not identical. In contrast to human islets, mouse islets are densely innervated.121 Furthermore, adrenaline stimulates glucagon secretion (by binding to β-receptors122) in mouse islets, but (if anything) inhibits glucagon secretion in human islets.59 As a consequence of these differences, the counter-regulatory response is much weaker in humans than in mice, which might contribute to the differences in mice and humans with HI.

Role of the KATP channel in T2DM

T2DM is far more prevalent than NDM and a worldwide scourge. It currently afflicts 335 million people and the number increases hourly.1 T2DM is a bihormonal disorder that involves both insufficient insulin secretion and defective glucagon secretion. Glucagon secretion is increased at high plasma glucose concentrations (exacerbating the consequences of impaired insulin secretion) and is inadequate at low plasma glucose levels (potentially resulting in fatal hypoglycaemia).123 Oversecretion of glucagon contributes considerably to the hyperglycaemia in patients with T2DM, and suppression of glucagon secretion by administration of somatostatin leads to a marked reduction in the insulin required to maintain euglycaemia.124 The report that mice in which the glucagon receptor has been genetically inactivated remain normoglycaemic even after complete chemical destruction of the β cells, whereas wild-type mice become strongly hyperglycaemic, highlights the role of glucagon as a causal factor in diabetic hyperglycaemia.125 Interestingly, both under physiological and diabetic conditions, very few α cells (only ~2%) are needed to prevent major counter-regulatory deregulation.126

T2DM has a strong genetic component, but disease risk is also enhanced by factors such as age, pregnancy and obesity.1 Multiple genes are probably involved, which may differ between individuals. One of the first to be associated with increased T2DM risk was a common polymorphism (Glu23Lys) in the Kir6.2-encoding gene (KCNJ11).127,128 Subsequently, this variant was shown to be in strong linkage disequilibrium with another variant, Ser1369Ala, in the adjacent SUR1-encoding gene (ABCC8), such that >95% of people who are homomeric for Kir6.2-Lys23 also carry two copies of SUR1-Ala1369. Thus, either variant could cause the increased disease risk. Although the increase in individual risk is small (OR 1.2), the population risk is highly significant, because 58% of people carry at least one Kir6.2-Lys23 allele.128

How the ‘at-risk’ variant(s) predisposes to T2DM is not fully resolved. In clinical studies, the Kir6.2-Lys23 variant has been shown to reduce glucose-induced suppression of glucagon secretion whilst not affecting insulin secretion.129 At the molecular level, the effects of the mutation(s) on KATP channel function are subtle and vary between laboratories. For example, increases, decreases and no change in ATP sensitivity have been documented for the Kir6.2-Lys23 variant.130–132 Studies combining both polymorphisms reveal that the Kir6.2-Lys23/SUR1-Ala1369 variant shows a very small reduction in the ATP concentration causing half-maximal inhibition (IC50) of KATP channel activity.133 This may be because the SUR1-Ala1369 variant enhances the ATPase activity of nucleotide binding site 2 of SUR1 and leads to increased nucleotide activation of the channel by Mg-nucleotides.134 However, although there is a difference in IC50, at higher (presumably more physiological) ATP concentrations, no difference in channel inhibition exists between ‘low-risk’ and ‘at-risk’ channels.134 Thus, how the Kir6.2-Lys23/SUR1-AlaA1369 variant increases the risk of T2DM is not immediately clear.

A further complication is that T2DM is (usually) a disease of later life. This fact is generally attributed to a gradual decline in β-cell function or mass, which is postulated to occur with age in all individuals but only progresses to overt T2DM in people who initially have compromised β-cell function. Clinical evidence indeed suggests a progressive age-dependent decline in β-cell function.135 Although longitudinal studies on isolated human islets are impossible (for obvious reasons), evidence exists that islets from organ donors with T2DM exhibit reduced glucose metabolism and glucose-induced insulin secretion.136 Fascinatingly, restoration of glucose metabolism by pharmacological activators of glucokinase restores glucose metabolism and insulin secretion in these islets.136 Thus, impaired glucose metabolism may be a feature of T2DM. If so, this would decrease glucose-induced KATP channel closure and, particularly if combined with a lower KATP channel ATP sensitivity, might compromise β-cell function. Importantly, even small changes in KATP channel activity can have dramatic effects on β-cell and α-cell electrical activity

Sulphonylureas, by closing KATP channels, are expected to normalize Ca2+ entry in β cells from patients with T2DM. However, if a metabolic defect exists, sulphonyureas will not fully restore insulin secretion because glucose metabolites are also required for downstream steps in insulin release (subsequent to KATP channel closure). By contrast, metabolism is not predicted to be impaired in patients with NDM caused by KATP channel mutations. This difference may explain why sulphonylureas continue to work in NDM, but—despite being initially effective—eventually fail in T2DM (secondary failure).137

Conclusions

KATP channel closure has a dual role in the regulation of pancreatic hormone release. Depending on the relative magnitudes of the resting KATP current and other currents in the cell, it can either stimulate (insulin) or inhibit (glucagon) secretion. Dysregulation of this mechanism might underlie the reciprocal changes in insulin secretion and glucagon secretion found in T2DM. Gain-of-function mutations cause a spectrum of diabetes syndromes that range in severity from NDM to T2DM; conversely, loss-of-function mutations cause HI. Defects in islet cell metabolism may also be expected to affect glucose homeostasis via changes in KATP channel activity, and several studies suggest that it may contribute to impaired hormone secretion in both NDM138,139 and T2DM. Future work should be directed at investigating the role of impaired KATP channel regulation in T2DM, and its effect on both insulin and glucagon secretion. Available data also suggest it might be worth exploring the potential of sulphonylureas for the treatment of the impaired glucagon secretion found in both type 1 diabetes mellitus and T2DM.

Key points.

Closure of ATP-sensitive potassium channels (KATP channels) stimulates insulin secretion but inhibits glucagon release

The role of KATP channels in insulin secretion is well understood, but precisely how glucose inhibits glucagon release remains controversial

Activating mutations in KATP channel genes cause neonatal diabetes mellitus, whereas loss-of-function mutations cause congenital hyperinsulinism

Both insufficient insulin secretion and dysregulation of glucagon release contribute to impaired glucose homeostasis in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM)

A common KATP channel haplotype predisposes to T2DM

An age-dependent decline in metabolism may also contribute to T2DM via mechanisms that are both dependent on, and independent of, KATP channels

Review criteria.

This Review was based on the authors’ personal collection of publications concerning KATP-channels, insulin secretion and glucagon release. All papers cited were English-language, full-text papers.

Acknowledgements

Work in the authors’ laboratories is funded by the Wellcome Trust, the European Union, Diabetes UK, the Medical Research Council and the Royal Society. F. M. Ashcroft holds the Wolfson-Royal Society merit award.

Footnotes

Author contributions

Both authors contributed equally to all aspects of manuscript preparation.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Contributor Information

Frances M. Ashcroft, Henry Wellcome Centre for Gene Function, Department of Physiology, Anatomy and Genetics, Parks Road, Oxford OX1 3PT, UK

Patrik Rorsman, Oxford Centre for Diabetes, Endocrinology and Metabolism, Radcliffe Department of Medicine, University of Oxford, Churchill Hospital, Oxford OX3 7LJ, UK.

References

- 1.Ashcroft FM, Rorsman P. Diabetes mellitus and the β cell: the last ten years. Cell. 2012;148:1160–1171. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nichols CG. KATP channels as molecular sensors of cellular metabolism. Nature. 2006;440:470–476. doi: 10.1038/nature04711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ashcroft FM, Harrison DE, Ashcroft SJ. Glucose induces closure of single potassium channels in isolated rat pancreatic beta-cells. Nature. 1984;312:446–448. doi: 10.1038/312446a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang Q, et al. R-type Ca2+-channel-evoked CICR regulates glucose-induced somatostatin secretion. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:453–460. doi: 10.1038/ncb1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gromada J, et al. ATP-sensitive K+ channel-dependent regulation of glucagon release and electrical activity by glucose in wild-type and SUR1−/− mouse α-cells. Diabetes. 2004;53(Suppl. 3):S181–S189. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.suppl_3.s181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shiota C, Rocheleau JV, Shiota M, Piston DW, Magnuson MA. Impaired glucagon secretory responses in mice lacking the type 1 sulfonylurea receptor. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2005;289:E570–E577. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00102.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aguilar-Bryan L, et al. Cloning of the beta cell high-affinity sulfonylurea receptor: a regulator of insulin secretion. Science. 1995;268:423–426. doi: 10.1126/science.7716547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Inagaki N, et al. Reconstitution of IKATP: an inward rectifier subunit plus the sulfonylurea receptor. Science. 1995;270:1166–1170. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5239.1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sakura H, Ammala C, Smith PA, Gribble FM, Ashcroft FM. Cloning and functional expression of the cDNA encoding a novel ATP-sensitive potassium channel subunit expressed in pancreatic β-cells, brain, heart and skeletal muscle. FEBS Lett. 1995;377:338–344. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)01369-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tucker SJ, Gribble FM, Zhao C, Trapp S, Ashcroft FM. Truncation of Kir6.2 produces ATP-sensitive K+ channels in the absence of the sulphonylurea receptor. Nature. 1997;387:179–183. doi: 10.1038/387179a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shyng S, Ferrigni T, Nichols CG. Regulation of KATP channel activity by diazoxide and MgADP. Distinct functions of the two nucleotide binding folds of the sulfonylurea receptor. J Gen Physiol. 1997;110:643–654. doi: 10.1085/jgp.110.6.643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gribble FM, Tucker SJ, Ashcroft FM. The essential role of the Walker A motifs of SUR1 in K-ATP channel activation by Mg-ADP and diazoxide. EMBO J. 1997;16:1145–1152. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.6.1145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nichols CG, et al. Adenosine diphosphate as an intracellular regulator of insulin secretion. Science. 1996;272:1785–1787. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5269.1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trube G, Rorsman P, Ohno-Shosaku T. Opposite effects of tolbutamide and diazoxide on the ATP-dependent K+ channel in mouse pancreatic β-cells. Pflugers Arch. 1996;407:493–499. doi: 10.1007/BF00657506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gribble FM, Reimann F. Sulphonylurea action revisited: the post-cloning era. Diabetologia. 2003;46:875–891. doi: 10.1007/s00125-003-1143-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sturgess NC, Ashford ML, Cook DL, Hales CN. The sulphonylurea receptor may be an ATP-sensitive potassium channel. Lancet. 1985;2:474–475. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(85)90403-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ashcroft FM, Ashcroft SJ, Harrison DE. Properties of single potassium channels modulated by glucose in rat pancreatic β-cells. J Physiol. 1988;400:501–527. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ashcroft F, Rorsman P. Type 2 diabetes mellitus: not quite exciting enough? Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13(Suppl. 1):R21–R31. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rorsman P, Eliasson L, Kanno T, Zhang Q, Gopel S. Electrophysiology of pancreatic β-cells in intact mouse islets of Langerhans. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2011;107:224–235. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2011.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schulla V, et al. Impaired insulin secretion and glucose tolerance in beta cell-selective Cav1.2 Ca2+ channel null mice. EMBO J. 2003;22:3844–3854. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Braun M, et al. Voltage-gated ion channels in human pancreatic beta-cells: electrophysiological characterization and role in insulin secretion. Diabetes. 2008;57:1618–1628. doi: 10.2337/db07-0991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rorsman P, Braun M. Regulation of insulin secretion in human pancreatic islets. Annu Rev Physiol. 2013;75:155–179. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-030212-183754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Henquin JC, Meissner HP. Significance of ionic fluxes and changes in membrane potential for stimulus-secretion coupling in pancreatic β-cells. Experientia. 1984;40:1043–1052. doi: 10.1007/BF01971450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Atwater I, Ribalet B, Rojas E. Mouse pancreatic beta-cells: tetraethylammonium blockage of the potassium permeability increase induced by depolarization. J Physiol. 1979;288:561–574. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dean PM, Matthews EK. Electrical activity in pancreatic islet cells. Nature. 1968;219:389–390. doi: 10.1038/219389a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meissner HP. Electrical characteristics of the β-cells in pancreatic islets. J Physiol (Paris) 1976;72:757–767. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Atwater I, Ribalet B, Rojas E. Cyclic changes in potential and resistance of the beta-cell membrane induced by glucose in islets of Langerhans from mouse. J Physiol. 1978;278:117–139. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1978.sp012296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cook DL, Crill WE, Porte D., Jr Plateau potentials in pancreatic islet cells are voltage-dependent action potentials. Nature. 1980;286:404–406. doi: 10.1038/286404a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kanno T, Rorsman P, Gopel SO. Glucose-dependent regulation of rhythmic action potential firing in pancreatic beta-cells by K(ATP)-channel modulation. J Physiol. 2002;545:501–507. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.031344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Larsson O, Kindmark H, Brandstrom R, Fredholm B, Berggren PO. Oscillations in KATP channel activity promote oscillations in cytoplasmic free Ca2+ concentration in the pancreatic beta cell. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:5161–5165. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.10.5161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ammala C, et al. Inositol trisphosphate-dependent periodic activation of a Ca2+-activated K+ conductance in glucose-stimulated pancreatic β-cells. Nature. 1991;353:849–852. doi: 10.1038/353849a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Worley JF, 3rd, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum calcium store regulates membrane potential in mouse islet β-cells. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:14359–14362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Satin LS, Tavalin SJ, Smolen PD. Inactivation of HIT cell Ca2+ current by a simulated burst of Ca2+ action potentials. Biophys J. 1994;66:141–148. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80759-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sherman A, Rinzel J, Keizer J. Emergence of organized bursting in clusters of pancreatic β-cells by channel sharing. Biophys J. 1998;54:411–425. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(88)82975-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smith PA, Ashcroft FM, Rorsman P. Simultaneous recordings of glucose dependent electrical activity and ATP-regulated K+-currents in isolated mouse pancreatic β-cells. FEBS Lett. 1990;261:187–190. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)80667-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gopel SO, et al. Activation of Ca2+-dependent K+ channels contributes to rhythmic firing of action potentials in mouse pancreatic β cells. J Gen Physiol. 1999;114:759–770. doi: 10.1085/jgp.114.6.759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goforth PB, et al. Calcium-activated K+ channels of mouse β-cells are controlled by both store and cytoplasmic Ca2+: experimental and theoretical studies. J Gen Physiol. 2002;120:307–322. doi: 10.1085/jgp.20028581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tarasov AI, et al. The mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter MCU is essential for glucose-induced ATP increases in pancreatic β-cells. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e39722. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Detimary P, Gilon P, Henquin JC. Interplay between cytoplasmic Ca2+ and the ATP/ADP ratio: a feedback control mechanism in mouse pancreatic islets. Biochem J. 1998;333:269–274. doi: 10.1042/bj3330269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rolland JF, Henquin JC, Gilon P. Feedback control of the ATP-sensitive K+ current by cytosolic Ca2+ contributes to oscillations of the membrane potential in pancreatic β-cells. Diabetes. 2002;51:376–384. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.2.376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Henquin JC. ATP-sensitive K+ channels may control glucose-induced electrical activity in pancreatic β-cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1988;156:769–775. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(88)80910-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Henquin JC. The fiftieth anniversary of hypoglycaemic sulphonamides. How did the mother compound work? Diabetologia. 1992;35:907–912. doi: 10.1007/BF00401417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zunkler BJ, Lins S, Ohno-Shosaku T, Trube G, Panten U. Cytosolic ADP enhances the sensitivity to tolbutamide of ATP-dependent K+ channels from pancreatic β-cells. FEBS Lett. 1988;239:241–244. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(88)80925-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gribble FM, Tucker SJ, Ashcroft FM. The interaction of nucleotides with the tolbutamide block of cloned ATP-sensitive K+ channel currents expressed in Xenopus oocytes: a reinterpretation. J Physiol. 1997;504:35–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.00035.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Proks P, Reimann F, Green N, Gribble F, Ashcroft F. Sulfonylurea stimulation of insulin secretion. Diabetes. 2002;51(Suppl. 3):S368–S376. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.2007.s368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Masia R, et al. An ATP-binding mutation (G334D) in KCNJ11 is associated with a sulfonylurea-insensitive form of developmental delay, epilepsy, and neonatal diabetes. Diabetes. 2007;56:328–336. doi: 10.2337/db06-1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gromada J, Franklin I, Wollheim CB. α-cells of the endocrine pancreas: 35 years of research but the enigma remains. Endocr Rev. 2007;28:84–116. doi: 10.1210/er.2006-0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rorsman P, Salehi SA, Abdulkader F, Braun M, MacDonald PE. KATP-channels and glucose-regulated glucagon secretion. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2008;19:277–284. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Miki T, et al. ATP-sensitive K+ channels in the hypothalamus are essential for the maintenance of glucose homeostasis. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:507–512. doi: 10.1038/87455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Munoz A, et al. Regulation of glucagon secretion at low glucose concentrations: evidence for adenosine triphosphate-sensitive potassium channel involvement. Endocrinology. 2005;146:5514–5521. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kawamori D, et al. Insulin signaling in α cells modulates glucagon secretion in vivo. Cell Metab. 2009;9:350–361. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ishihara H, Maechler P, Gjinovci A, Herrera PL, Wollheim CB. Islet β-cell secretion determines glucagon release from neighbouring α-cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:330–335. doi: 10.1038/ncb951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rorsman P, et al. Glucose-inhibition of glucagon secretion involves activation of GABAA-receptor chloride channels. Nature. 1989;341:233–236. doi: 10.1038/341233a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Franklin I, Gromada J, Gjinovci A, Theander S, Wollheim CB. β-cell secretory products activate α-cell ATP-dependent potassium channels to inhibit glucagon release. Diabetes. 2005;54:1808–1815. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.6.1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Prost AL, Bloc A, Hussy N, Derand R, Vivaudou M. Zinc is both an intracellular and extracellular regulator of KATP channel function. J Physiol. 2004;559:157–167. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.065094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hardy AB, Serino AS, Wijesekara N, Chimienti F, Wheeler MB. Regulation of glucagon secretion by zinc: lessons from the β cell-specific Znt8 knockout mouse model. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2011;13(Suppl. 1):112–117. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2011.01451.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cheng-Xue R, et al. Tolbutamide controls glucagon release from mouse islets differently than glucose: involvement of KATP channels from both α-cells and δ-cells. Diabetes. 2013;62:1612–1622. doi: 10.2337/db12-0347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hauge-Evans AC, et al. Somatostatin secreted by islet delta-cells fulfills multiple roles as a paracrine regulator of islet function. Diabetes. 2009;58:403–411. doi: 10.2337/db08-0792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Walker JN, et al. Regulation of glucagon secretion by glucose: paracrine, intrinsic or both? Diabetes Obes Metab. 2011;13(Suppl. 1):95–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2011.01450.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.MacDonald PE, et al. A KATP channel-dependent pathway within alpha cells regulates glucagon release from both rodent and human islets of Langerhans. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e143. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gopel SO, Kanno T, Barg S, Rorsman P. Patch-clamp characterisation of somatostatin-secreting -cells in intact mouse pancreatic islets. J Physiol. 2000;528:497–507. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00497.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rorsman P, Hellman B. Voltage-activated currents in guinea pig pancreatic α2 cells. Evidence for Ca2+-dependent action potentials. J Gen Physiol. 1988;91:223–242. doi: 10.1085/jgp.91.2.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Manning Fox JE, Gyulkhandanyan AV, Satin LS, Wheeler MB. Oscillatory membrane potential response to glucose in islet β-cells: a comparison of islet-cell electrical activity in mouse and rat. Endocrinology. 2006;147:4655–4663. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Quoix N, et al. Glucose and pharmacological modulators of ATP-sensitive K+ channels control [Ca2+]c by different mechanisms in isolated mouse α-cells. Diabetes. 2009;58:412–421. doi: 10.2337/db07-1298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Barg S, Galvanovskis J, Gopel SO, Rorsman P, Eliasson L. Tight coupling between electrical activity and exocytosis in mouse glucagon-secreting α-cells. Diabetes. 2000;49:1500–1510. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.9.1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gopel SO, et al. Regulation of glucagon release in mouse-cells by KATP channels and inactivation of TTX-sensitive Na+ channels. J Physiol. 2000;528:509–520. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00509.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bokvist K, et al. Characterisation of sulphonylurea and ATP-regulated K+ channels in rat pancreatic α-cells. Pflugers Arch. 1999;438:428–436. doi: 10.1007/s004249900076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Huang YC, Rupnik M, Gaisano HY. Unperturbed islet α-cell function examined in mouse pancreas tissue slices. J Physiol. 2011;589:395–408. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.200345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tarasov AI, Girard CA, Ashcroft FM. ATP sensitivity of the ATP-sensitive K+ channel in intact and permeabilized pancreatic β-cells. Diabetes. 2006;55:2446–2454. doi: 10.2337/db06-0360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Leung YM, et al. Electrophysiological characterization of pancreatic islet cells in the mouse insulin promoter-green fluorescent protein mouse. Endocrinology. 2005;146:4766–4775. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ramracheya R, et al. Membrane potential-dependent inactivation of voltage-gated ion channels in α-cells inhibits glucagon secretion from human islets. Diabetes. 2010;59:2198–2208. doi: 10.2337/db09-1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gopel S, et al. Capacitance measurements of exocytosis in mouse pancreatic α-, β- and δ-cells within intact islets of Langerhans. J Physiol. 2004;556:711–726. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.059675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Olsen HL, et al. Glucose stimulates glucagon release in single rat α-cells by mechanisms that mirror the stimulus-secretion coupling in beta-cells. Endocrinology. 2005;146:4861–4870. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Thorel F, et al. Conversion of adult pancreatic α-cells to β-cells after extreme β-cell loss. Nature. 2010;464:1149–1154. doi: 10.1038/nature08894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Li C, et al. Regulation of glucagon secretion in normal and diabetic human islets by γ-hydroxybutyrate and glycine. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:3938–3951. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.385682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Geng X, Li L, Watkins S, Robbins PD, Drain P. The insulin secretory granule is the major site of KATP channels of the endocrine pancreas. Diabetes. 2003;52:767–776. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.3.767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ozanne SE, Guest PC, Hutton JC, Hales CN. Intracellular localization and molecular heterogeneity of the sulphonylurea receptor in insulin-secreting cells. Diabetologia. 1995;38:277–282. doi: 10.1007/BF00400631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Guiot Y, et al. Morphological localisation of sulfonylurea receptor 1 in endocrine cells of human, mouse and rat pancreas. Diabetologia. 2007;50:1889–1899. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0731-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yang SN, et al. Glucose recruits KATP channels via non-insulin-containing dense-core granules. Cell Metab. 2007;6:217–228. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Shibasaki T, Sunaga Y, Fujimoto K, Kashima Y, Seino S. Interaction of ATP sensor, cAMP sensor, Ca2+ sensor, and voltage-dependent Ca2+ channel in insulin granule exocytosis. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:7956–7961. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309068200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Eliasson L, et al. SUR1 regulates PKA-independent cAMP-induced granule priming in mouse pancreatic β-cells. J Gen Physiol. 2003;121:181–197. doi: 10.1085/jgp.20028707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Nakazaki M, et al. cAMP-activated protein kinase-independent potentiation of insulin secretion by cAMP is impaired in SUR1 null islets. Diabetes. 2002;51:3440–3449. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.12.3440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kang G, Leech CA, Chepurny OG, Coetzee WA, Holz GG. Role of the cAMP sensor Epac as a determinant of KATP channel ATP sensitivity in human pancreatic β-cells and rat INS-1 cells. J Physiol. 2008;586:1307–1319. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.143818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kang Y, et al. ATP modulates interaction of syntaxin-1A with sulfonylurea receptor 1 to regulate pancreatic β-cell KATP channels. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:5876–5883. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.089607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Eliasson L, et al. PKC-dependent stimulation of exocytosis by sulfonylureas in pancreatic β cells. Science. 1996;271:813–815. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5250.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hoy M, et al. Tolbutamide stimulates exocytosis of glucagon by inhibition of a mitochondrial-like ATP-sensitive K+ (KATP) conductance in rat pancreatic A-cells. J Physiol. 2000;527(Pt 1):109–120. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00109.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Mariot P, Gilon P, Nenquin M, Henquin JC. Tolbutamide and diazoxide influence insulin secretion by changing the concentration but not the action of cytoplasmic Ca2+ in β-cells. Diabetes. 1998;47:365–373. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.47.3.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zhang CL, et al. The cAMP sensor Epac2 is a direct target of antidiabetic sulfonylurea drugs. Science. 2009;325:607–610. doi: 10.1126/science.1172256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Gloyn AL, et al. Activating mutations in the gene encoding the ATP-sensitive potassium-channel subunit Kir6.2 and permanent neonatal diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1838–1849. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hattersley AT, Ashcroft FM. Activating mutations in Kir6.2 and neonatal diabetes: new clinical syndromes, new scientific insights, and new therapy. Diabetes. 2005;54:2503–2513. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.9.2503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Rubio-Cabezas O, Flanagan SE, Damhuis A, Hattersley AT, Ellard S. KATP channel mutations in infants with permanent diabetes diagnosed after 6 months of life. Pediatr Diabetes. 2012;13:322–325. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2011.00824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Flanagan SE, et al. Update of mutations in the genes encoding the pancreatic β-cell KATP channel subunits Kir6.2 (KCNJ11) and sulfonylurea receptor 1 (ABCC8) in diabetes mellitus and hyperinsulinism. Hum Mutat. 2009;30:170–180. doi: 10.1002/humu.20838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Clark RH, et al. Muscle dysfunction caused by a KATP channel mutation in neonatal diabetes is neuronal in origin. Science. 2010;329:458–461. doi: 10.1126/science.1186146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Proks P, et al. Molecular basis of Kir6.2 mutations associated with neonatal diabetes or neonatal diabetes plus neurological features. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:17539–17544. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404756101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.McTaggart JS, Clark RH, Ashcroft FM. The role of the KATP channel in glucose homeostasis in health and disease: more than meets the islet. J Physiol. 2010;588:3201–3209. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.191767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ellard S, et al. Permanent neonatal diabetes caused by dominant, recessive, or compound heterozygous SUR1 mutations with opposite functional effects. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:375–382. doi: 10.1086/519174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Babenko AP, et al. Activating mutations in the ABCC8 gene in neonatal diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:456–466. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Proks P, Girard C, Ashcroft FM. Functional effects of KCNJ11 mutations causing neonatal diabetes: enhanced activation by MgATP. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:2717–2726. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Koster JC, Marshall BA, Ensor N, Corbett JA, Nichols CG. Targeted overactivity of β cell KATP channels induces profound neonatal diabetes. Cell. 2000;100:645–654. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80701-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Girard CA, et al. Expression of an activating mutation in the gene encoding the KATP channel subunit Kir6.2 in mouse pancreatic β cells recapitulates neonatal diabetes. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:80–90. doi: 10.1172/JCI35772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Remedi MS, et al. Secondary consequences of β cell inexcitability: identification and prevention in a murine model of KATP-induced neonatal diabetes mellitus. Cell Metab. 2009;9:140–151. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Pearson ER, et al. Switching from insulin to oral sulfonylureas in patients with diabetes due to Kir6.2 mutations. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:467–477. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ashcroft FM. New uses for old drugs: neonatal diabetes and sulphonylureas. Cell Metab. 2010;11:179–181. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Zung A, Glaser B, Nimri R, Zadik Z. Glibenclamide treatment in permanent neonatal diabetes mellitus due to an activating mutation in Kir6.2. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:5504–5507. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Remedi MS, Agapova SE, Vyas AK, Hruz PW, Nichols CG. Acute sulfonylurea therapy at disease onset can cause permanent remission of KATP-induced diabetes. Diabetes. 2011;60:2515–2522. doi: 10.2337/db11-0538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Dunne MJ, Cosgrove KE, Shepherd RM, Aynsley-Green A, Lindley KJ. Hyperinsulinism in infancy: from basic science to clinical disease. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:239–275. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00022.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Thomas PM, et al. Mutations in the sulfonylurea receptor gene in familial persistent hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia of infancy. Science. 1995;268:426–429. doi: 10.1126/science.7716548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Huopio H, et al. A new subtype of autosomal dominant diabetes attributable to a mutation in the gene for sulfonylurea receptor 1. Lancet. 2003;361:301–307. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12325-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Ocal G, et al. Clinical characteristics of recessive and dominant congenital hyperinsulinism due to mutation(s) in the ABCC8/KCNJ11 genes encoding the ATP-sensitive potassium channel in the pancreatic β cell. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2011;24:1019–1023. doi: 10.1515/jpem.2011.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Hussain K, Bryan J, Christesen HT, Brusgaard K, Aguilar-Bryan L. Serum glucagon counterregulatory hormonal response to hypoglycemia is blunted in congenital hyperinsulinism. Diabetes. 2005;54:2946–2951. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.10.2946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Hardy OT, et al. Accuracy of [18F]fluorodopa positron emission tomography for diagnosing and localizing focal congenital hyperinsulinism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:4706–4711. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-1637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Blomberg BA, Moghbel MC, Saboury B, Stanley CA, Alavi A. The value of radiologic interventions and 18F-DOPA PET in diagnosing and localizing focal congenital hyperinsulinism: systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol Imaging Biol. 2013;15:97–105. doi: 10.1007/s11307-012-0572-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Kane C, et al. Loss of functional KATP channels in pancreatic β-cells causes persistent hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia of infancy. Nat Med. 1996;2:1344–1347. doi: 10.1038/nm1296-1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Henquin JC, et al. In vitro insulin secretion by pancreatic tissue from infants with diazoxide-resistant congenital hyperinsulinism deviates from model predictions. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:3932–3942. doi: 10.1172/JCI58400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Henquin JC. The dual control of insulin secretion by glucose involves triggering and amplifying pathways in β-cells. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2011;93(Suppl. 1):S27–S31. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8227(11)70010-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Hugill A, Shimomura K, Ashcroft FM, Cox RD. A mutation in KCNJ11 causing human hyperinsulinism (Y12X) results in a glucose-intolerant phenotype in the mouse. Diabetologia. 2010;53:2352–2356. doi: 10.1007/s00125-010-1866-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Miki T, et al. Defective insulin secretion and enhanced insulin action in KATP channel-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:10402–10406. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Seghers V, Nakazaki M, DeMayo F, Aguilar-Bryan L, Bryan J. Sur1 knockout mice. A model for K(ATP) channel-independent regulation of insulin secretion. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:9270–9277. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.13.9270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Remedi MS, et al. Hyperinsulinism in mice with heterozygous loss of KATP channels. Diabetologia. 2006;49:2368–2378. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0367-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Szollosi A, Nenquin M, Henquin JC. Overnight culture unmasks glucose-induced insulin secretion in mouse islets lacking ATP-sensitive K+ channels by improving the triggering Ca2+ signal. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:14768–14776. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701382200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Rodriguez-Diaz R, et al. Alpha cells secrete acetylcholine as a non-neuronal paracrine signal priming β cell function in humans. Nat Med. 2011;17:888–892. doi: 10.1038/nm.2371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.De Marinis YZ, et al. GLP-1 inhibits and adrenaline stimulates glucagon release by differential modulation of N- and L-type Ca2+ channel-dependent exocytosis. Cell Metab. 2010;11:543–553. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Cryer PE. Hypoglycaemia: the limiting factor in the glycaemic management of type I and type II diabetes. Diabetologia. 2002;45:937–948. doi: 10.1007/s00125-002-0822-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Shah P, et al. Lack of suppression of glucagon contributes to postprandial hyperglycemia in subjects with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:4053–4059. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.11.6993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Lee Y, Wang MY, Du XQ, Charron MJ, Unger RH. Glucagon receptor knockout prevents insulin-deficient type 1 diabetes in mice. Diabetes. 2011;60:391–397. doi: 10.2337/db10-0426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Thorel F, et al. Normal glucagon signaling and β-cell function after near-total α-cell ablation in adult mice. Diabetes. 2011;60:2872–2882. doi: 10.2337/db11-0876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Sakura H, et al. Sequence variations in the human Kir6.2 gene, a subunit of the βcell ATP-sensitive K-channel: no association with NiDDM in while Caucasian subjects or evidence of abnormal function when expressed in vitro. Diabetologia. 1996;39:1233–1236. doi: 10.1007/BF02658512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Gloyn AL, et al. Large-scale association studies of variants in genes encoding the pancreatic β-cell KATP channel subunits Kir6.2 (KCNJ11) and SUR1 (ABCC8) confirm that the KCNJ11 E23K variant is associated with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2003;52:568–572. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.2.568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Tschritter O, et al. The prevalent Glu23Lys polymorphism in the potassium inward rectifier 6.2 (KiR6.2) gene is associated with impaired glucagon suppression in response to hyperglycemia. Diabetes. 2002;51:2854–2860. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.9.2854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Riedel MJ, Boora P, Steckley D, de Vries G, Light PE. Kir6.2 polymorphisms sensitize β-cell ATP-sensitive potassium channels to activation by acyl CoAs: a possible cellular mechanism for increased susceptibility to type 2 diabetes? Diabetes. 2003;52:2630–2635. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.10.2630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Schwanstecher C, Meyer U, Schwanstecher M. K(IR)6.2 polymorphism predisposes to type 2 diabetes by inducing overactivity of pancreatic β-cell ATP-sensitive K+ channels. Diabetes. 2002;51:875–879. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.3.875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Villareal DT, et al. Kir6.2 variant E23K increases ATP-sensitive K+ channel activity and is associated with impaired insulin release and enhanced insulin sensitivity in adults with normal glucose tolerance. Diabetes. 2009;58:1869–1878. doi: 10.2337/db09-0025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Hamming KS, et al. Coexpression of the type 2 diabetes susceptibility gene variants KCNJ11 E23K and ABCC8 S1369A alter the ATP and sulfonylurea sensitivities of the ATP-sensitive K+ channel. Diabetes. 2009;58:2419–2424. doi: 10.2337/db09-0143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Fatehi M, et al. The ATP-sensitive K+ channel ABCC8 S1369A type 2 diabetes risk variant increases MgATPase activity. Diabetes. 2012;61:241–249. doi: 10.2337/db11-0371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.U. K. prospective diabetes study 16. Overview of 6 years' therapy of type II diabetes: a progressive disease. U. K. Prospective Diabetes Study Group. Diabetes. 1995;44:1249–1258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Doliba NM, et al. Glucokinase activation repairs defective bioenergetics of islets of Langerhans isolated from type 2 diabetics. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2012;302:E87–E102. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00218.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Iafusco D, et al. No beta cell desensitisation after a median of 68 months on glibenclamide therapy in patients with KCNJ11-associated permanent neonatal diabetes. Diabetologia. 2011;54:2736–2738. doi: 10.1007/s00125-011-2273-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Njolstad PR, et al. Neonatal diabetes mellitus due to complete glucokinase deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1588–1592. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105243442104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Gloyn AL. Glucokinase (GCK) mutations in hyper- and hypoglycemia: maturity-onset diabetes of the young, permanent neonatal diabetes, and hyperinsulinemia of infancy. Hum Mutat. 2003;22:353–362. doi: 10.1002/humu.10277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Rosengren AH, et al. Reduced insulin exocytosis in human pancreatic β-cells with gene variants linked to type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2012;61:1726–1733. doi: 10.2337/db11-1516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]