Introduction

Successful aging may be viewed as favorably adapting to the physiologic and functional changes that occur as one advances in age, while maintaining a sense of purpose and connection (Flood, 2002). A positivistic approach is offered as alternative to established models and frameworks that regard aging as an evitable consequence of life except in the absence of disease and disability (Dillaway & Byrnes, 2009; Rowe & Kahn, 1998). Novel pathways to achieve successful aging continue to evolve as the population of older adults in the US increases. New paradigms are needed to provide guidance and support as adults move into the later decades of life, striving to maintain their independence, intent upon aging in place. Pursuing a focused, goal-based approach, that is, articulating what is wanted in life at a particular point in time, throughout one’s lifespan is an emerging strategy for older adults that may require a shift in attitude and approach for care providers. Multiple, self-care programs (Chronic Disease Self-Management; Matter of Balance) to promote health have been touted as a means to age successfully. Yet, these programs pay little regard to a critical first step, that is, the personal goals of older adults. The capacity to self-identify goals and to pursue actions towards achieving those goals transcends age. The purpose of this paper is to examine life goals of low-income, community-dwelling older adults participating in a wellness coaching program so as to gain insight into this key aspect of successful aging. Consideration and review of the initial step of self-selected goals is presented to provide a critical reference point for aging care providers to intervene, so as to promote successful aging.

Background and Significance

Out-patient health care delivery for older adults in the US remains focused on quick visits, as evidenced by an average time of 23 minutes spent with providers across all specialties, with little opportunity for assessing and incorporating personal needs, preferences, and goals (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 2013). Health care providers cite insufficient time and limited financial resources as barriers to proactive, goal based care, particularly for older adults with multiple morbidities (Bleijenberg et al., 2013). Discharge planners and community service providers reported that disabilities and deficits remain the central focus with insufficient attention to older adults’ goals when transitioning from hospital to home setting. (Chapin, Chandran, Sergeant, & Koenig, 2014). When an older adult meets with a health care provider for routine assessments or disease management, seldom are they queried as to their preferences and desires for specific life goals. There is a lack of shared decision-making and individualization so as to chart the course for their upcoming years. Low-income older adults face a particular disadvantage as health care providers may not acknowledge their ability or interest to participate in self-care (Williems, Maesschalck, Deveugele, Derese, & DeMaeseneer, 2005). Visits often conclude with distribution of general patient education materials without any individualization and consideration of personal preferences (Beverly, Wray, Chiu, & LaCoe, 2014). Lack of shared decision-making does not align with continued health care reform focused on changing the delivery process to a tailored, person-centered approach that improves the experience of care, improves the health of populations with a resulting reduction in health care costs (Berwick, Nolan, & Whittington, 2008). Shifting health care efforts to patient centered and goal directed health promotion and disease prevention strategies calls for more holistic frameworks (Chapin et al., 2014). One such framework is the theory of successful aging (Topaz, Troutman-Jordan, & MacKenzie, 2014).

Theory of Successful Aging

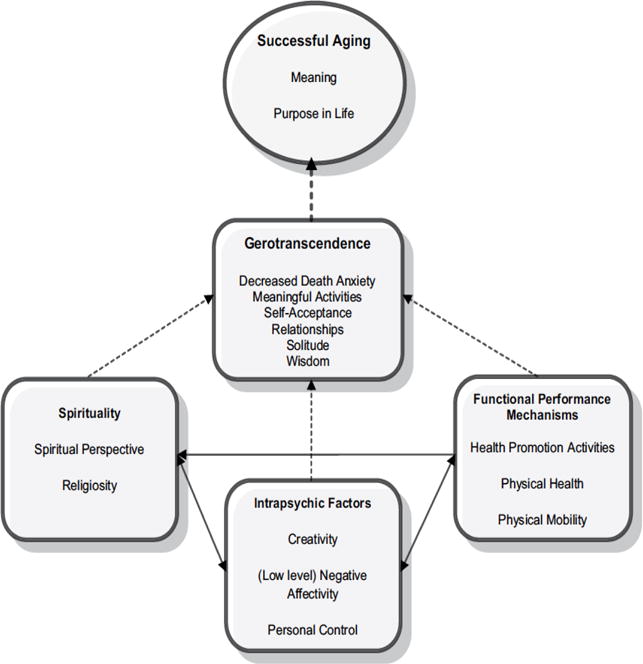

Supporting successful aging requires a personal, multi-factorial approach involving the older adult, care providers, and significant others. As depicted in Figure 1, Troutman’s mid-range theory of Successful Aging defines 3 processes - functional performance mechanisms, intra-psychic factors and spirituality - as contributing to the complex process of gero-transcendence and ultimately, successful aging (Topaz et al., 2014). Health care currently is structured on potential or existing patient problems with care directed towards prevention or management of illness. Geriatric care in particular applies the translation of decades of scientific research focused on disease states or clinical symptoms. Most previous research efforts have pursued isolated body systems (eg. cardiac, renal, endocrine) yet an older adult’s daily function is dependent upon effective symbiotic relationships among physical systems. Intertwined within these relationships are the psychosocial, intra-personal and spiritual elements, now beginning to receive attention in research and health care.

Figure 1.

Theory of Successful Aging

(adapted for use from Topaz, et al., 2014)

Application of the model suggests aging successfully requires a multi-faceted approach and a coaching intervention may help to guide the older adult to integrate major influencers as they focus on personal goal achievement. Currently, there are no known, formally implemented health care programs that combine a comprehensive and holistic, geriatric focused assessment and formal coaching mechanism for older adults. To age successfully, a comprehensive and holistic approach is needed to guide and inform the older adult as they select health care options and lifestyle strategies that align with self-identified goals.

COLLAGE is a national member consortium of continuing care retirement communities (CCRC) and older adult housing sites initiated and developed by Kendal Outreach, LCC (KOLLC), a subsidiary of The Kendal Corporation, a non-profit organization, and the Institute for Aging Research (IFAR) at Hebrew SeniorLIfe, a Massachusetts not-for-profit corporation. Members in the consortium participate in the application of the first computerized, valid and reliable approach to annual standardized resident assessments in the US within senior housing. Members of the COLLAGE consortium participate in the integrated comprehensive assessment that identifies current performance, needs, and preferences. Using 2 tools from the interRAI (interRAI.org, 2017) assessment system, the consortium has been supporting the health and well-being of community-dwelling older adults for several years, providing assessment data in the areas of cognition, communication and vision, mood and behavior, psychological well-being, functional status, health conditions, and social support. Three years ago, one continuing care retirement community (CCRC) within the COLLAGE consortium, added a wellness coaching component to the COLLAGE assessment system resulting in an extremely positive impact on the life satisfaction of its residents (Howard, Schreiber, Morris, Russotto, & Flashner-Fineman, 2016). This outcome was the primary impetus to offer a revised program, Vitalize 360, that combines the assessment system with the wellness coaching strategy and provides a comprehensive, integrative program designed to best serve the health and wellness needs of community-dwelling older adults.

As a wellness coaching program, Vitalize 360 is consistent with the evolving perspective of facilitating aging in place through a person-centered, and self-defined, goal based approach to health care. Through the Vitalize 360 process, personal preferences assume center-stage and older adults are encouraged and guided to establish life goals with an associated action plan for goal achievement. If people participate in activities that have a personal sense of meaning and purpose, they are much more likely to change their behavior (Röcke, Lachman, & Blanchard-Fields, 200). The primary objective is to engage and motivate older adults to pursue activities directed toward goal achievement so as to improve quality of life, and achieve successful aging.

Vitalize 360 – The Power of Wellness

The Vitalize 360 wellness coaching program consists of three key components as an integrated, health promotion system. First, older adults participate in an integrated comprehensive, geriatric assessment that identifies current performance, needs, and preferences. The assessment is conducted through the application of two interRAI tools, the Health and Social Check-up (HSC) and Lifestyle Survey (LS). As integrated tools, the HSC and LS are basic intake forms and serve two key functions: (1) they provide a foundational description of the persons health, function, and social needs; and 2) they focus the older adult’s attention on his/her strengths and challenges in the major domains of wellness i.e., physical fitness and exercise, recreational activities, nutrition, emotional and psychological functioning, cognition, and spirituality. The Health and Social Check-up generates a minimal, comprehensive set of measures on disease state, clinical complications, cognition, function, mood, social supports, environmental conditions, medication use, and health service use. The Lifestyle Survey collects personal, preferential data within the context of the wellness domains, exercise and physical activity, recreation, nutrition, sleep patterns and social relationships. These tools are available for use by researchers and health service organizations, requiring a contract with interRAI, the non-profit organization who developed these tools and continue monitoring the use and revisions. (interRAI.org, 2017).

The Administrative Team of the COLLAGE consortium provides oversight to the training of the wellness coaches, comprised of 2 full days in a small group setting with other new coaches, followed by periodic webinars and seminars. Though not a requirement, most coaches have education and training as registered nurses or social workers. The wellness coach meets with each resident for approximately one hour, and, through a directed conversation, collaborates with the older adult to complete the Health and Social Check-up. The structure allows opportunity to explain any unclear questions and, limitations from visual impairment or health literacy are circumvented. The Lifestyle Survey is designed for completion by the resident immediately following the initial assessment.

Completion of the Health and Social Check-up and the Lifestyle Survey generates a summary, a Resident Snapshot, provided from an established computer software platform designed specifically for the Health and Social Check-up and Lifestyle Survey. The summary report is the second component of the Vitalize 360 program and draws from the personal assessment to identify potential problems or risks (e.g., cognitive decline, falls, re-hospitalizations, nutritional deficits) as well as options the older adult is interested in pursuing (e.g., fall prevention program, cognitive training, physical activity). The algorithms used to create the resident snapshot results are based on research conducted using specific interRAI items from large national and international data sets (Hirdes et al., 2008; Morris et al., 2016a; Morris et al., 2016b; Morris et al., 2014a; Morris et al., 2014b; Morris, Berg, Fries, Steel, & Howard, 2013).

The initial assessment (Health and Social Check-up and Lifestyle Survey) is followed by health coaching sessions conducted by the wellness coach and constitutes the third component. The coach sets the stage for the older adult to engage in a set of programmed steps to achieve self -identified goals which will help him/her maximize health status, functioning, and overall well being. The dialogue begins with the wellness coach posing the questions, “ What are your life goals?” “ What is it that you want out of your life now?” The older adult dialogues with the wellness coach directly to determine personal life goals and create an individualized wellness plan, the Vitality Plan to achieve the goals. Once the Vitality Plan is complete, the coach will contact the older adult at least once, every 3 months to assess participation in the suggested activities and progress towards goal achievement. Full reassessments involving updates to the Health and Social Check-up and Lifestyle Surveys occur no less than once annually and more frequently should the older adult experience a major life event such as hospitalization or death of a significant other.

Personal Coaching

Coaching as a formal process most commonly is associated with an organized sport, involving an individual or small group. Children and young adults most often are recipients of the reinforcement of desired behaviors (Ammentorp et al., 2013). The coaching concept also has extended to middle-aged adults as they develop and pursue personal and professional goals. People may enlist the aid of professional life coaches to receive formal guidance towards improved decision-making and achievement of self-identified and self-prioritized goals (Ammentorp et al., 2013). Use of personal coaches has gained popularity as adults strive for increased life satisfaction and quality of life but may remain unsure as to the best strategies to achieve these outcomes.

Perhaps constrained by preconceived notions and biases about aging, life coaching among older adults is not commonplace and based on the belief that older adults, viewed as ‘older and wiser,’ no longer need advice or instruction to manage their lives. Yet, similar to younger generations, there is expanding attention and effort towards maintaining and improving quality of life and satisfaction among the cohort, and concomitantly supporting the potential to maximize opportunities and achieve life goals, regardless of age. Health status and control of disease state are central elements with advancing age and the need for disease prevention and health care self-management become priorities in an attempt to age successfully.

Established coaching strategies for older adults are based on a disease or illness model and address targeted health behaviors to prevent or manage disease states. There is demonstrated success with coaching for chronic problems of hypertension, diabetes, and asthma (Federman et al., 2015; Ogedegbe et al., 2013, Margolius et al., 2012). In efforts directed toward disease management, older adult are assigned target goals such as normal peak flows, normotensive blood pressure, normal hemoglobin A1c, normal BMI (Ogedegbe et al., 2013; Margoulis et al., 2012; Engel & Lindner, 2006; Kronk-Schoen, 2015). Targeting specific health behaviors either in response to a problem or as a preventive measure also has shown favorable outcomes. Older adults are coached to achieve goals such as engagement of physical activity, adherence to a healthy diet, compliance with prescribed medications, and effective pain management (Langford et al.,2015 Clark et al., 2005; Tingjian, Wilber, & Simmons, 2011; Stahl, Albert, Dew, Lockovich, & Reynolds, 2014; Van Hoecke, Delecluse, Bogaerts, & Boen, 2014; Wijsman et al., 2013).

With established self-management programs, the older adults are assigned or prescribed a target goal(s) to achieve, based on disease state or health risk rather than building on current wellness state and potential opportunities to achieve goals that are personally meaningful. The Vitalize 360 program includes individualized coaching without specific end points such as lower BMI or increased disease self-management. Rather, the program used an older adult’s life goals and preferences to guide the coaching process that includes goal setting and empathetic listening. Designed specifically for community-dwelling older adults, Vitalize 360 directs older adults in selecting personal goals that align with their assessment results and developing an action plan for goal achievement. By empowering older adults with summarized assessment results and encouraging them to develop life goals that address their personal preferences, the strategy has potential to empower older adults to assume responsibility and adopt self-care behaviors to promote healthy aging as they strive to achieve their self-selected goals and advance towards successful aging.

As the concept of life goals for septuagenarians and octogenarians gains attention among health care providers, and many health care providers promote evidence-based and self-management programs for the older adults, there is value to take pause initially, gain perspective on the perception and direction of older adults, and complete an examination of the life goals established by low-income, community-dwelling older adults who participated in Vitalize 360 through their housing site. The purpose of the paper is to examine the life goals selected by low-income, community-dwelling older adults participating in a wellness coaching program so as to gain insight into this key aspect of a holistic approach for older adults to support successful aging.

Methods

A secondary analysis design was used as, the primary purpose for collecting data was to complete the assessment component and Vitality Plan of the Vitalize 360 program for residents who voluntarily participated in the wellness coaching program. Participation in Vitalize 360 is offered as part of the care services within 3 subsidized housing sites, serving as the setting for the study. The parent organization has oversight for continuing care retirement communities (CCRC) and low-income housing. Based on the successful outcomes from implementation of Vitalize 360 at one of the CCRC’s (Howard et al.,2016), the program was offered to residents within the subsidized housing units. IRB approval was obtained from the institutional compliance board of the parent organization.

The principle investigator and wellness coaches employed multiple strategies to recruit older adults to the Vitalize 360 program including formal presentations, newsletters, flyers, and personal invitations. Inclusion criteria were resident status at one of the 3 housing sites and age 60 or older. Older adults with moderate cognitive impairment and inability to read English were excluded from the study. Once interest was expressed, the wellness coach contacted the older adult to schedule the initial, personal assessment meeting. Following the meeting and the collection of baseline, assessment data, older adult residents completed the Lifestyle Survey. Data from this tool and the Health and Social Check-up were then entered into a software system designed specifically for the interRAI assessment tools. A Resident Snapshot is generated from the assessment tools and provides a summary of the older adult’s health status and personal preferences. At a follow-up meeting, the wellness coach and older adult meet to discuss the content from the resident snapshot and to generate a Vitality Plan that includes life goals and an action plan for goal achievement.

Examination of personal, life goals among a sample of 161 older adult residents in 3 subsidized housing sites began with a review of each subject’s Vitality Plan. Prior to this review, all vitality plans were de-identified by a data analyst to assume confidentiality. The researchers opted for an inductive approach to develop a scheme for categorizing the personal goal statements (Waltz, Strickland, & Lenz, 2017). A review of 25% of the responses generated a list of 10 goal categories. Next, the entire set of goal statements were reviewed independently by two researchers, one a registered nurse and the other, a social worker, and each personal goal statement was coded into one of the 10 major categories. Though not reported here, an ‘other’ category served as a repository for those individual goals not fitting into the major categories. Subsequently, the two researchers reviewed the goals and discussed categorization until consensus was achieved.

Results

The average age of the participants, each of whom developed a Vitality Plan, was 85.2 (sd=8.95) and 75.8% were female. There was no racial diversity within the sample of white older adult. Often found in aging, Jewish populations in the US, the sample was homogenous with 98% having at least 8 years of formal education. Approximately 84% of the older adults lived alone and most rated their health as good (54.7%) or fair (32%). Participants responded to a quality of life item and 34% reported being pleased with life as a whole, 31% mostly satisfied, and only 3.2% unhappy. In addition, the overwhelming majority (95%) reported they lived in a supportive community. All participants resided in independent housing and were physically active as the average, self-reported physical activity level was between 2 and 3 hours in the past 3 days.

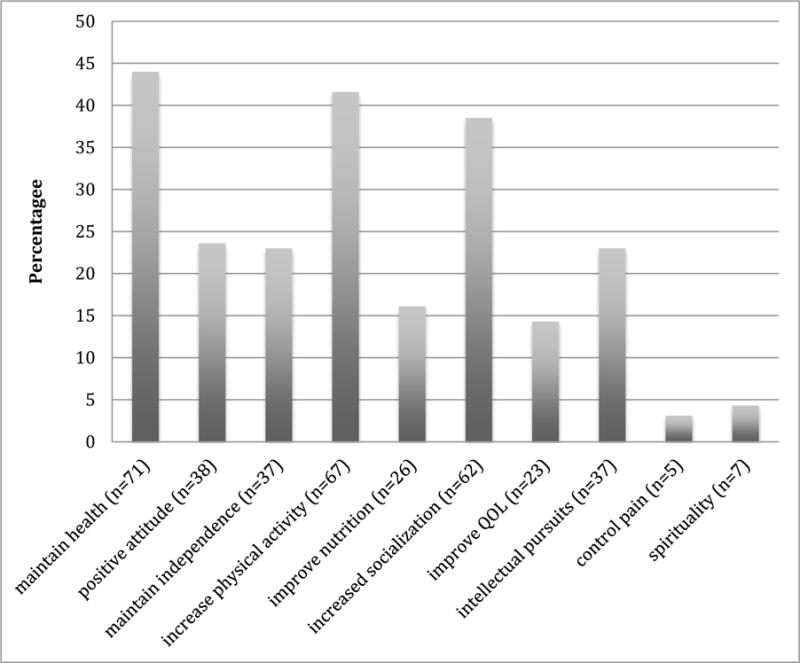

Figure 2 lists the 10 major goal categories extracted from the Vitality Plan review. Goals with the highest frequency were: maintaining health, increasing physical activity, and increasing socialization.

Figure 2.

Vitality Plan – Major Life Goals

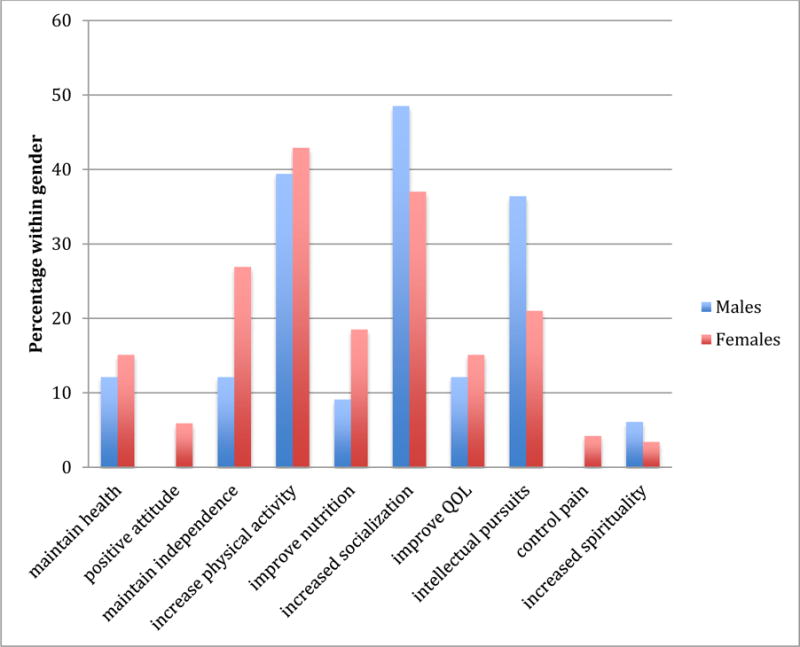

Although the majority of the sample was female, we examined if there were differences between males and females and the life goals they selected. Chi square analyses revealed no significant differences in selected goals between men and women but the goals of maintain independence, improved nutrition, increased socialization and intellectual pursuits represented the largest discrepancies between males and females. More women than men wanted to maintain their independence and improve nutrition while more men than women wanted to increase socialization and engage in intellectual pursuits (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Life Goals for Males and Females

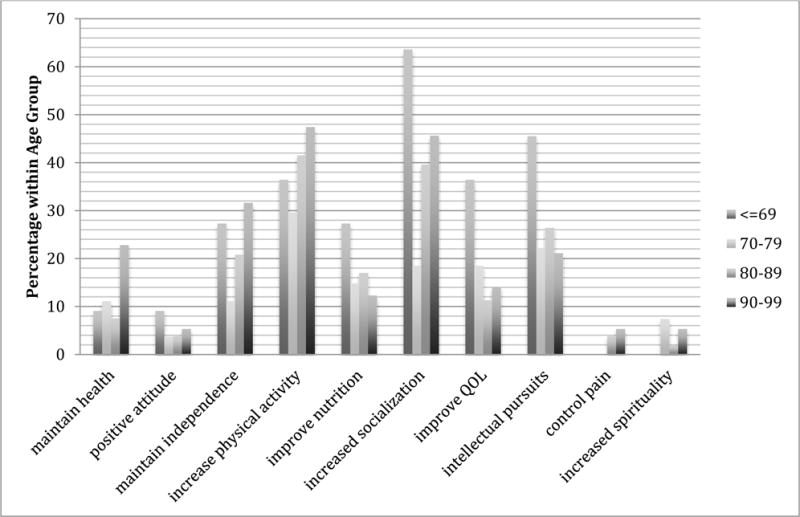

The participant ages spanned several decades with the oldest being 102 years. Table 1 summarizes the distribution of age across the decades and interestingly, the majority were 90-99 years old. There were life goals for only 2 individuals over 99 years old and so their data were eliminated from the goal-specific analysis. For the youngest cohort (<=69), increased socialization, intellectual pursuits, increased physical activity and improved quality of life were goals selected most often. In the subsequent decades, increased physical activity was the most commonly selected goal followed by intellectual pursuits. The goals of increased physical activity, increased socialization, and intellectual pursuits, were identified most often by the octogenarians. An increase in physical activity was the most commonly selected goal among participants in their 90’s, followed by socialization and independence goals. While not a commonly selected goal across the age span, maintaining health as a goal occurs most frequently among those in their nineties in contrast to the other decades. Given the increased multi-morbidity with advancing age, the outcome is expected.

Table 1.

Distribution of Ages

| AGE RANGE | NUMBER | PERCENTAGE |

|---|---|---|

| 61-69 | 12 | 7.8% |

| 70-79 | 27 | 17.6% |

| 80-89 | 55 | 35.9% |

| 90-99 | 57 | 37.3% |

| 100-102 | 2 | 1.2% |

Discussion

The purpose of the project was to examine life goals selected by white, low-income, community-dwelling older adults participating in a wellness coaching program so as to gain insight into potential aspects of successful aging. In view of Troutman’s theory, a detailed review demonstrated that functional performance mechanisms are valued most highly. Maintenance of health and increased physical activity were 2 commonly identified personal goals within this sample. A third goal, increased socialization, aligns with the intra-psychic factors representing the need for personal contact. Notably, 38 of the participants identified the personal goal of a positive attitude, another component of the intra-psychic factors within Troutman’s successful aging model. While the third key element of the aging model, spirituality, was not prominent among the self-selected goals for this sample, it may be that the sample older adults were satisfied with their level of spirituality and had no need to improve upon what already is in place. The results align with the motivations for goals reported by Street, O’Connor and Robinson (2007) who found social health, accomplishment, and independence as key motivations and only a 1.6% identified a spiritually motivating factor. This work also underscores the importance of establishing goals and supporting efforts towards goal achievement as the relationship between physical health and depression is mediated by perceived progress towards goal achievement (Street, et al., 2007).

While there are many reports on the use of goal setting specific to a disease process or common geriatric symptom, eg., falls, there is limited information about the support for self-selected life goals for all older adults. Au, Ng, Lai, & Tsien (2015) found goal pursuit, not necessarily goal achievement, was associated with greater life satisfaction. For the youngest older adult cohort, affiliation goals were more important while for the oldest older adult group, altruistic goals increased life satisfaction (Au et al., 2015). Similarly, the young old (<=69 years) of the study sample reported here selected the goal of increased socialization most often.

Second only to maintenance of health, increase in physical activity was the most frequently cited personal goal and was prominent across all decades. Specific goal-setting behaviors and social support from family and friends were identified as key factors in maintaining physical activity as reported by Floegel and colleagues (2015). Increasing physical activity indirectly by providing financial and social incentives to achieve prescribed walking goals was effective among a group of older adults residing in a retirement community (Harkins, Kullgren, Bellany, Karlawish & Glanz, 2017). Notably, White, Wojcicki and McAuley (2011) found that personal goals were not directly related to physical activity outcomes but that establishing goals served as a mediator between self-efficacy and functional limitations.

Limitations

The sample of low-income older adults lacked racial and ethnic diversity limiting the generalization of results to a broader population. The results presented here are a secondary analysis of existing data collected to evaluate the effectiveness of a wellness coaching program designed for community-dwelling older adults. While project did not examine actual or perceived goal attainment, the analysis points to the need for further exploration in the area. As one advances into the later decades of life, there are persistent challenges to physical and psychosocial health state. These challenges may require an adjustment of personal goals as some originally established goals may be unattainable. While not a consideration in the study, personal tenacity and the ability to modify personal goals over time may contribute to increased life satisfaction (Bailly, Gana, Hervé, Joulain, & Alaphilippe, 2014). Using a collaborative goal setting model, Waldersen et al.,(2014) found when older adults were flexible and willing to adopt new strategies, opportunity for goal attainment increased.

Conclusion

Providing optimal health care to the elderly is costly. Older adults represent 13% of the total population but account for 34% of total US personal health care expenses (DHHS, 2010). Without major changes, this financial disproportion will increase markedly by 2030, when the number of adults 65 years and older is expected to comprise 20% of the US population (CDC, 2013; DHHS, 2010). Approximately 9% of older adults live below the poverty level, another 5% classified as near-poor (DHHS, 2010). Notably, an estimated 1.8 million older adults live in federally subsidized housing, a group consisting disproportionately of single women between 70-90 years of age (Wilden & Redfoot, 2002). Nearly all receive Medicare benefits, and 86% receive supplemental insurance (US Census Bureau, 2010).

This project examined person-centered goals developed in a personalized, wellness coaching program, Vitalize 360 among a vulnerable population residing in subsidized senior housing. Within the program is a reliable, valid, comprehensive and systematic assessment system (Hirdes et al., 2008) that identifies the health care needs of older adults and, through the developed Vitality Plan, directs them to those resources that will be most beneficial. In resource restricted environments, readily identifying and connecting persons to available supports are foundational to any wellness promotion efforts.

Consideration of life goals of older adults deserves the persistent and dedicated attention of health care providers. Given the complexity of the aging process, the preferences of the older adult at the center of the care planning process strategically supports goal attainment. Toto, Skidmore, Terhorst, Rosen & Weiner (2014) reported that for community-dwelling older adults, personal goal attainment is based on the involvement of health care providers, a supportive setting, and caregiver support. In the project, all participants were members of a housing site within which, support for the development of goals and goal attainment is facilitated through the wellness coaching program, Vitalize 360. Lower socioeconomic status may have a negative effect on overall health outcomes. As shown in the work by McLaughlin, Connell, Heeringa, Li, and Scott Roberts (2010), those with higher socioeconomic status had an increased incidence of successful aging. Geriatric care providers need to be mindful of the impact socioeconomic status may have on health outcomes of older adults.

Nursing has a responsibility to move beyond the stereotypical, broad-based geriatric interventions and focus on individualization of care. Implementation and evaluation of a person-centered, goal-based approach to care for older adults is needed as the US continues with health care reform. Examining health care costs and the potential savings from a goal-based approach may serve well to increase acceptance into models of care delivery. All persons, including older adults are more likely to pursue those activities that provide meaning and purpose (Röcke, Lachman, &Bllanchard-Fields, 2008) and when care provided is aligned with personal needs, increased wellness for the older adult follows (Flood, 2002). Providing an opportunity to create and pursue self-selected life goals of older adults is worth consideration when developing and testing interventions designed to support successful aging. One participant in the Vitalize 360 program shared the following comment. In creating his Vitality Plan, goals established long ago in younger years reemerged, providing a renewed sense of direction and purpose to life, a possible representation of successful aging.

Figure 4.

Life Goals by Age Group

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to gratefully acknowledge and thank the 161 older adults who, through their participation in the Vitalize 360 program, provided the data for this project. In addition, the authors wish to acknowledge the assistance of Ms. Ashley Whitelock, RN who provided consistent support for the revision of the manuscript. The project was supported by NIH/NIA P 30 AG048785 Boston Roybal Center for Active Lifestyle Interventions (RALI) and NIH/NINR P 20NR015320 Northeastern University Center for Self-Care & Health Technoology (NUCare).

Contributor Information

Elizabeth P. Howard, Associate Professor, Northeastern University, Bouvé College of Health Sciences, School of Nursing, Boston, Massachusetts 02115.

Kara E. Louvar, Research Assistant, Hebrew SeniorLife, Institute for Aging Research, Boston, MA.

References

- Ammentorp J, Uhrenfeldt L, Angel F, Ehrensvärd M, Carlsen E, Kofoed P. Can life coaching improve health outcomes?–A systematic review of intervention studies. BMC Health Services Research. 2013;13:428. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-13-428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Au A, Ng E, Lai S, Tsien T. Goals and life satisfaction of Hong Kong Chinese older adults. Clinical Gerontologist. 2015;38:224–234. doi: 10.1080/07317115.2015.1008117. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bailly N, Gana K, Hervé C, Joulain M, Alaphilippe D. Does flexible goal adjustment predict life satisfaction in older adults? A six-year longitudinal study. Aging and Mental Health. 2014;18(5):662–670. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2013.875121. http://dx.doi.org.ezproxy.neu.edu/10.1080/13607863.2013.875121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beverly EA, Wray LA, Chiu C, LaCoe CL. Older adults’ perceived challenges with health care providers treating their type 2 diabetes and comorbid conditions. Clinical Diabetes Jan. 2014;32(1):12–17. doi: 10.2337/diaclin.32.1.12. https://doi.org/10.2337/diaclin.32.1.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleijenberg N, Ten Dam VH, Steunenberg B, Drubbel I, Numans ME, De Wit NJ, Schuurmans MJ. Exploring the expectations, needs and experiences of general practitioners and nurses towards a proactive and structured care programme for frail older patients: a mixed-methods study. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2013;69(10):2262–2273. doi: 10.1111/jan.12110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2013 State and National Summary Tables. 2013 Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ahcd/namcs_summary/2013_namcs_web_tables.pdf.

- Chapin RK, Chandran D, Sergeant JF, Koenig TL. Hospital to community transitions for adults: discharge planners and community service providers’ perspectives. Social Work in Health Care. 2014;53(4):311–329. doi: 10.1080/00981389.2014.884037. http://dx.doi.org.ezproxy.neu.edu/10.1080/00981389.2014.884037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark PG, Rossi JS, Greaney ML, Riebe DA, Greene GW, Saunders SD, Lees FD. Intervening on exercise and nutrition in older adults. The Rhode Island SENIOR project. Journal of Aging and Health. 2005;16(6):753–778. doi: 10.1177/0898264305281105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillaway HE, Byrnes M. Reconsidering successful aging: a call for renewed and expanced academic critiques and conceptualizations. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2009;28:702–722. doi: 10.1177/0733464809333882. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Engel L, Lindner H. Impact of using a pedometer on time spent walking in lder adults with type 2 diabetes. The Diabetes Educator. 2006;32(1):98–107. doi: 10.1177/0145721705284373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Federman AD, Martynenko M, O’Conor R, Kannry J, Karp A, Lurio J, Wisnivesky JP. Rationale and design of a comparative effectiveness trial of home- and clinic-based self-management support coaching for older adults with asthma. Contemporary Clinical Trials. 2015;44:103–111. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2015.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floegel TA, Giacobbi JR, Dzierzewski JM, Aiken-Morgan AT, Roberts B, McCrae CS, Buman MP. Intervention Markers of Physical Activity Maintenance in Older Adults. American Journal Of Health Behavior. 2015;39(4):487–499. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.39.4.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flood M. Successful aging: a concept analysis. Journal of Theory Construction & Testing. 2002;6(2):105–108. [Google Scholar]

- Harkins KA, Kullgren JT, Bellany SL, Karlawish J, Glanz K. A trial of financial and social incentives to increase older adults’ walking. American Jl Preventive Medicine. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.11.011. Available online 3 January 2017. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2016.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hirdes JP, Ljunggren G, Morris JN, Frijters DH, Soveri HF, Gray L, Gilgen R. Reliability of the interRAI suite of assessment instruments: A 12-country study of an integrated health information system. BMC Health Services Research. 2008;8(1):277. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-8-277. doi: http://dx.doi.org.ezproxy.neu.edu/10.1186/1472-6963-8277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard EP, Schreiber R, Morris JN, Russotto A, Flashner-Fineman S. COLLAGE 360: A model of person-centered care to promote health among older adults. Journal of Ageing Research and Healthcare. 2016;1(1) doi: 10.14302/issn.2474-7785.jarh-16-1123. Available at: http://www.openaccesspub.org/journals/jarh/viewarticle.php?art_id=322&jid=38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kronk-Schoen JL, Shim R, Nagel R, Lehman J, Myers M, Lucey C, Post DM. Outcomes of a health coaching intervention delivered by medical students for older adults with uncontrolled type 2 diabetes. Gerontology & Geriatrics Education. 2015 doi: 10.1080/02701960.2015.1018514. Published online: 20 Feb 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langford DP, Fleig L, Brown KC, Cho NJ, Frost M, Ledoven M, Ashe MC. Back to the future-feasibility of recruitment and retention to patient education and telephone follow-up after hip fracture: A randomized control trial. Patient Preference and Adherence. 2015;9:1342–1351P. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S86922. doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S86922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolius D, Bodenheimer T, Bennett H, Wong J, Hgo V, Padilla G, Thom DH. Health coaching to improve hypertension treatment in a low-income, minority population. Annals of Family Medicine. 2012;10(3):199–205. doi: 10.1370/afm.1369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin SJ, Connell CM, Heeringa SG, Li LW, Scott Roberts J. Successful Aging in the United States: Prevalence Estimates From a National Sample of Older Adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2010;65B(2):216–226. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbp101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JN, Howard EP, Steel K, Berg C, Tchalla A, Munankarmi A, David D. Strategies to reduce the risk of falling: cohort study analysis with 1-year follow-up in community dwelling older adults. BMC Geriatrics. 2016a;16:92. doi: 10.1186/s12877-016-0267-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JN, Howard E, Steel K, Perlman C, Fries BE, Garms-Homolova V, Szczerbinska K. Updating the MDS Cognitive Performance Scale. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology. 2016b;29(1):47–55. doi: 10.1177/0891988715598231. jgpn.sagepub.com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JN, Howard EP, Steel K, Schreiber R, Fries BE, Lipsitz LA, Goldman B. Predicting risk of hospital and emergency department use for home care elderly persons through a secondary analysis of cross-national data. BMC Health Services Research. 2014a;14:519. doi: 10.1186/s12913-014-0519-z. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6963/14/519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JN, Howard EP, Fries BE, Berkowitz R, Goldman B, David D. Using the community health assessment to screen for continued driving. Accident Analysis and Prevention. 2014b Feb;63:104–119. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2013.10.030. Epub 2013 Nov 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JN, Berg K, Fries BE, Steel K, Howard EP. Scaling functional status within the interRAI suite of assessment instruments. BMC Geriatrics. 2013 Nov 21;13(1):128. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-13-128. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogedegbe G, Fernandez S, Fournier L, Silver SA, Kong J, Gallagher S, Teresi JA. The counseling older adults to control hypertension (COACH) trial: design and methodology of a group-based lifestyle intervention for hypertensive minority older adults. Contemporary Clinical Trials. 2013;35(1):70–79. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2013.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Röcke C, Lachman ME, Blanchard-Fields F. Perceived trajectories of life satisfaction across past, present, and future: Profiles and correlates of subjective change in young, middle-aged, and older adults. Psychology and Aging. 2008;23(4):833–847. doi: 10.1037/a0013680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe JW, Kahn RL. Successful Aging. New York: Pantheon; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Stahl ST, Albert SM, Dew MA, Lockovich MH, Reynolds CF. Coaching in health dietary practices in at-risk older adults: a case of Indicated depression prevention. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2014;171(5):499–505. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13101373. doi: org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13101373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Street H, O’Connor M, Robinson H. Depression in older adults: exploring the relationship between goal setting and physical health. Int J Geriat Psychiatry. 2007;22:1115–1119. doi: 10.1002/gps.1797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tingjian Y, Wilder KH, Simmons J. Motivating high-risk older adults to exercise: does coaching matter? Home Health Care Services Quarterly. 2011;30(2):84–95. doi: 10.1080/01621424.2011.569670. Published online: 16 May 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toto PE, Skidmore ER, Terhorst L, Rosen J, Weiner DK. Goal attainment scaling (GAS) in geriatric primary care: a feasibility study. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics. 2015;60(1):16–21. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2014.10.022. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2014.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topaz M, Troutman-Jordan M, MacKenzie M. Construction, deconstruction, and reconstructon: the roots of successful aging theories. Nursing Science Quarterly. 2014;27(3):226–233. doi: 10.1177/0894318414534484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Hoecke AS, Delecluse C, Bogaerts A, Boen F. The long-term effectiveness of need-supportive physical activity counseling compared with a standard referral in sedentary older adults. Journal of Aging and Physical Activity. 2014;22(2):186–198. doi: 10.1123/JAPA2012.0261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldersen BW, Wolff JL, Roberts L, Bridges AW, Gitlin LN, Szanton SL. Functional goals and predictors of their attainment in low-income community-dwelling older adults. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2016.11.017. Available online 19 December 2016 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2016.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Waltz CF, Strickland OL, Lenz ER. Measurement in Nursing and Health Research. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- White SM, Wojcicji TR, McAuley E. Social cognitive influences on physical activity behavior in middle-aged and older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2012;67B(1):18–26. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbr064. https://doi-org.ezproxy.neu.edu/10.1093/geronb/gbr064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wijsman CA, Westendorp RG, Verhagen EA, Catt M, Slagboom PE, Anton JM, Mooijaart SP. Effects of a web-based intervention on physical activity and metabolism in older adults: randomized controlled trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2013;15(11):e233. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2843. Published online 2013 Nov 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]