SYNOPSIS

This article provides an overview of the basis, utility and validity of qualitative methods in research. It is aimed to enhance the understanding of a broad spectrum of readers: ranging from those mystified by such approaches, to those wanting a better critical knowledge to apply to literature review, and for healthcare providers considering developing an interest in the field. Qualitative research is crucial in augmentation of disease knowledge as well as the development of incremental care strategies and operational aspects of care that improves health outcomes.

Keywords: Qualitative, focus group, interview, patient perspective, phenomenology, coding, ethnography, conceptual framework

‘Not everything that can be counted counts, and not everything that counts can be counted.’

William Bruce Cameron, Professor of Sociology, 1963

Introduction

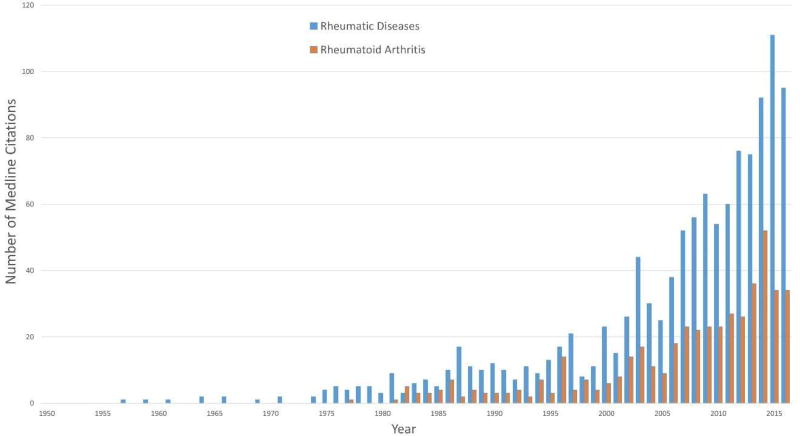

The last two centuries of medical research advancements were driven by the systematic collection of measurable assessments relying upon quantifiable constructs and producing measurable variables within populations. Quantitative research has far progressed medical science, but tells us little about the opinions and experiences of living with disease that could provide actionable insight but are less amenable to quantification. Qualitative research, on the other hand, provides valuable insight into patient experiences, attitudes, behavior, meaning, thoughts and broadens our understanding of human disease, and thusly in recent years, has carved a bona fide position as valuable science in healthcare operations and understanding of disease (figure 1).1,2 This position has been hard won for a science that inherently relies upon subjectivity in both data collection and analysis; and though endeavours to be free of bias, will always be guided by investigator perception and sensitivity. Though recently less so, still faces challenges in obtaining research funding and a difficulty publishing in high-impact journals persisting to some extent.3

Figure 1.

Number of Medline citations identified for a search of Qualitative Research AND Rheumatic Disease from 1950 to 2015.

This chapter reviews the underpinnings, utility and validity of qualitative method; punctuated with examples of how they have been applied in rheumatic disease research. In order to optimally define qualitative methodology, it is contrasted in this chapter with its counterpart, quantitative methodology, to which all readers have an acquaintanceship, hopefully making it easier to assimilate the less familiar ideas of qualitative research; revealing how these seemingly diverse schools are, in fact, interdependent; with quality research often employing both approaches. This review is addressed to a broad spectrum of readers: ranging from those wishing to better appraise the burgeoning number of published qualitative studies to researchers considering the role qualitative methods might play in answering their own research questions. We hope to inspire serious interest – and perhaps dedicated careers - in applying these methods to deciphering a deeper understanding of the biopsychosocial burden of rheumatic disease and how qualitative research methods might support the development of incremental management strategies4 to improve health-related quality of life (HRQoL), and perhaps even survival.5

WHAT IS QUALITATIVE RESEARCH?

Qualitative research explores the meaning attached to health-related experiences, cultures, views, opinions, and practices by individuals within their personal social and cultural context.6 Though data is represented by words that reflect recorded speech and behaviour (in contrast to numerical quantity, distribution, magnitude and frequency of quantitative research methods), qualitative methods are marked by careful, deliberate strategies of robust and systematic data collection, organization and interpretation of non-numerical data. Where quantitative research predominantly examines the relationships between independent, dependent and extraneous variables represented by numerical values, the corresponding qualitative analytic units are themes and concepts that arise through discussion, observation or document review. In contrast to quantitative research methods, the interactive nature of qualitative research enables investigators to actively participate in the quest for enhanced understanding (not necessarily definitive answers) and unexpected scientific lines of enquiry can emerge within the process of data acquisition1 (table 1).

Table 1.

Similarities and differences between qualitative and quantitative research methods

| Concept | Quantitative | Qualitative |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Goals | Generate comparisons and correlations of attributes | Investigate human perspectives |

|

| ||

| Level of Investigation | Broad, impersonal | Deep, personal |

|

| ||

| Level of Data Detail | Concise, numerical summation | Richly, detailed description |

|

| ||

| Focus | Relationship of numerical values | Personal experience |

|

| ||

| Driver | To prove / predict a hypothesis | Discovery / exploration |

|

| ||

| Research question | Hypothesis statement often proving a single predicted outcome to measure descriptive, causal, or associative/relational occurrences or states resulted in units of magnitude, quantity or frequency | Exploratory question seeking new understanding of human experience in dynamic, yet unquantifiable and in specifically described situations and settings |

|

| ||

| Sample size | Large – focused on precise trends across large groups | Small –focused collected case content |

|

| ||

| Sample recruitment | Random, representative, generalizable | Purposeful, not necessarily representative nor generalizable |

|

| ||

| Setting of Data Collection | Experimental; May occur in ‘the field’ with descriptive studies | Usually from where the participants are, i.e. ‘the field’, natural environment |

|

| ||

| Instruments | May be surveys with closed-ended questions | The interviewer or observer are the instruments with open-ended queries |

| May use equipment such as beakers, pipettes, serum testing etc. | ||

|

| ||

| Method Types: | Descriptive | Historical analysis using archival data |

| Correlative | ||

| Causal | Phenomonolgy | |

| Comparative | Ethnography / Participant observation (direct or indirect) | |

| Inferential | ||

| Action research | ||

|

| ||

| Data units / Coding | Numerical whether nominal, ordinal, interval, or ratio data | Words / Concepts |

|

| ||

| Analytic approach | Deductive: based on existing theories or established views | Inductive; allows data to emerge and guide the researcher and often takes researcher back to data collection phase to clarify/further explore a concept |

|

| ||

| Analysis | Statistical modeling to confirm accuracy and reproducibility | Interpretive and Identification of concepts and creation of themes |

|

| ||

| Design | Highly structured, experimental and quasi-experimental Design is fully committed prior to implementation | ‘Emergent’, i.e. responsive to data collection and subject to change depending on initial findings |

|

| ||

| Design Perspective | Objective, outcome-oriented | Subjective, process-oriented |

|

| ||

| Data Sources | Variable, objective medical data, quantifiable subjective data reduced to data points | Interviews, observation, audio/visual clips or documents |

|

| ||

| Data Collection Platform | Spreadsheets or other formulaic templates | Recording transcriptions generating volumes of narrative |

|

| ||

| Data | Scalable | Non-scalable |

| Easy to understand / interpret | Difficult to analyze and interpret | |

| Easy to generate comparisons | Collect more than one type to get holistic, comprehensive understanding to answer one question | |

|

| ||

| Success Indicator | Predetermine / predict an outcome | Saturation of newly discovered concepts |

|

| ||

| Conclusion | Strongly formulated with generalizability | Tentative |

|

| ||

| Presentation of Data | Often follows a formulaic statistical report that is central with some narrative describing background, arguments regarding relevance of results and conclusions drawn | Narrative, interpretative, often contains direct participant quotes or behaviour descriptions, also with brief background and conclusion |

|

| ||

| Resource Consumption Data Collection: | Variable depending on source of data Minimal, calculations often set as formulas run on computers | Time / labour intensive |

| Data Analysis: | Time / labour intensive | |

| Data Reporting: | Commonly formulaic, able to require minimal effort | Requires several people to evaluate the same data Requires high level narrative and literary skills |

Investigation typically takes the form of open-ended survey answers, field-note observations and/or anonymized transcripts obtained in focus group, or semi-structured individual patient interviews1 to form the descriptive raw data of the research from which the interpretation is derived.7 Qualitative methods can be applied to any study of human interactions, patient experiences, communication, diagnostic evaluation, disease activity definitions and health measurement scale development relevant to disease management1 focusing directly on the health condition itself, or any other aspect of care, including technical or operational facets. Pharmaceutical companies routinely apply qualitative research methods to healthcare providers and patients for marketing purposes; and recently have been more involved in funding the development of patient-reported outcome measures (PROMS) for use in clinical trials within diseases of interest to them.

However, the main use of qualitative methods in healthcare is to evaluate and understand the perspectives of patients and healthcare providers as a means to heighten knowledge of disease processes, diagnostic evaluation and management to improve health outcomes and health related quality of life (HRQoL). In the rheumatic diseases these include physician and patient treatment decision-making in RA and OA8,9,10, prescribing practices for musculoskeletal pain11, family and relationships in RA12, parenting and arthritis13,14, experiences of JIA15, patient-healthcare provider interactions16,17,18–23, perceived health benefits of treatment/intervention24,25,26, adherence to intervention26–29, as well as developing research priorities30. Increasingly, qualitative research has become more focused on specific disease manifestations that might only affect a minority of patients within a disease entity e.g. body image dissatisfaction in patients with cutaneous lupus31 or potentially common but hitherto neglected experiences of diseases such as fatigue in OA.32 However, qualitative investigations are not limited to patient experiences and might include any person related to any part of the disease process or healthcare experience, depending on the question to be answered (table 2). Subjects might therefore include family, friends, caregivers, clinicians, community healthcare providers, laboratory scientists, specialist nurses, rehabilitation specialists, trainees and administrative staff. Qualitative research is an inquisitive process; capturing motivation/adherence, emotions, needs, perceptions, experience, or opinions in words but otherwise follows a similar degree of robust and systematic data collection, organization and interpretation.

Table 2.

Application and goals of qualitative research methods

| Procurement of data sufficient to generate hypotheses for future quantitative investigation |

| Conceptual framework to characterize / facilitate understanding of a disease, issue, or area of concern/phenomena |

| Emergence of recurrent themes for actionable attention |

| Protocols, policy, educational materials |

| Classification System / Taxonomy |

| Survey instruments to measure relevance, importance, intensity of qualitative concepts e.g. PROM |

WHEN TO CHOOSE QUALITATIVE METHODS

Quantitative methods have formed the mainstay of biomedical research and are generally applied when there is sufficient information to form a hypothesis that can be tested using quantifiable comparative, associative, hierarchical or interval-type assessments. Qualitative strategies might be employed when there is insufficient data to form a stable hypothesis or quantitative assessment; and attainment of more information might help to formulate one. Alternately, quantitative results might be available but there is a need to understand the personal human relevance / motivation that drives the results. Both qualitative and quantitative research methods provide important tools that complement each other toward larger goals with many research projects adopting a mixed methods approach for comprehensiveness.

The preferred methodology for any given project is determined by the goals of the overall research question (see below). Increasingly, dovetailing of qualitative with more traditional quantitative research methods in a complementary fashion has been proven to support broader research goals. An integrated mixed-methods approach has become the mainstay of PROM development throughout medical and rheumatic disease research (2,33. An example of innovative blending of qualitative and quantitative methods, is the McMaster Toronto Arthritis patient preference questionnaire (MACTAR)34 The MACTAR captures both qualitative and quantitative data on patient priorities of physical function by enabling patients to set and quantify their own health-related priorities. The MACTAR identified a number of domains relating to functional impairment in SSc patients that are not captured in the Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index, highlighting the importance of patient participation in outcome measure design, content development and adoption35.

The incorporation of qualitative methods is particularly relevant to PROM development where capturing the patient experience is paramount to the success of the instrument leading to regulatory bodies such as the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) establishing that engaging the target patient population in PROM development should be used to support labelling claims and marketing authorization36,37. The importance of the patient voice has led to patient research partners coining the phrase ‘nothing about us, without us!’38.

One of several examples of qualitative patient data influencing outcomes, is the derivation of a minimal set of outcome measure for clinical trials in connective tissue disease-related interstitial lung disease (CTD-ILD)39. The project sought qualitative perspectives from both experts and patients with their relationships to the emerged concepts which were examined and cross-examined subsequently with quantitative strategies to gauge degree of importance. The qualitative input from patients altered the direction of the entire study and the final product – and, further, drew physician experts’ attention to the symptom of ‘cough’ as central to the ILD experience inspiring further independent quantitative investigations on potential causes, therapeutic implications and potential methods for capturing the severity and impact of cough in CTD-ILD39,40. The integration of quantitative and qualitative research studies can be challenging and less readily amenable to traditional meta-analytical approaches of aggregating data from multiple studies3,41,42. Nonetheless, applying mixed-method approaches expands the boundaries of research enabling a more complete assessment of most aspects of human disease41. Examples of effective integration of applied methods is presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Examples of mixed methods production motifs

| 1. PROM development: |

| Qualitative focus group data collection/analysis with isolation of concepts >> Quantitative testing of concepts for relevance/important in larger group >> Qualitative focus group/interview field-testing of best language >> Qualitative action research with patients to develop a set of questions >> Quantitative testing of questions using factor analysis, test-retest, etc |

| 2. Phenomonologic experience of living with a rheumatic health condition: |

| Qualitative focus group experience of living with ‘x’ condition with analysis yielding ‘y’ as prevalent interfering symptom >> Quantitative assessment of ‘y’ as a reliable marker of disease activity in ‘x’ in randomized controlled clinical trial |

| 3. Phenomonolgic experience with historical analysis of published blogs of people living with a specific manifestation of an autoimmune health condition: |

| Qualitative focus groups with analysis yielding unexpected pervasive self-management technique >> a. action research working with patients to develop anticipatory guidance strategies for safety AND b. quantitative testing of self-management technique for efficacy |

| 4. Ethnography combined with focus groups to learn barriers to healthcare access in a rural area: |

| Qualitative focus groups with analysis of perceived power differences between healthcare providers and patients as a barrier >> recorded observation of behaviour of patients and providers within health system identifying specific areas of concern >> qualitative action research with patient and providers to develop strategies that create equanimity in communication >> quantitative assessment of effectiveness of new strategies vs. prior behaviour. |

APPROACHES TO QUALITATIVE RESEARCH METHODS

Qualitative research methods include a variety of techniques for systematically collecting, organizing and interpreting human experiences captured through open discussion and observation1. Phenomenology, the study of human experience, is the overarching concept of qualitative research and drives almost all methods of performing qualitative research in healthcare, typically using interviews and focus groups, and can unearth unexpected experiences considered important by patients, otherwise overlooked by clinicians. For example, focus groups in rheumatoid arthritis (RA), revealed that a recurrent and pervasive theme that arose in the focus group data was the symptom of fatigue. The strong emergence of this caused subsequent research to quantify the magnitude of intensity, frequency, and correlation of fatigue in RA resulting in the quantitative discovery of fatigue as a reliable indicator of RA disease activity43.

Ethnography is the systematic study based on observation of people and has been more often used for cultural or social research cultures. It can take the form of direct observation by a non-participatory party or indirect by the researcher actually taking part in the natural setting in which the behaviour is observed. There have been few ethnographic studies but it is an application becoming more common; especially in combination with interview methods. One of the few studies in RA, used ethnography to understand the barriers to arthritis care in a Mayan community44. This study observed both people with arthritis and healthcare providers of varying levels, revealing that availability and attainability of access was further complicated by patient acceptability of the diminishing levels of quality of life that appeared to be related to indigenous vs non-indigenous power imbalances. The study concluded that accessibility strategies that are culturally sensitive and developed with Mayans are needed in order to increase Mayans accessing care [18]. Another ethnographic study investigated self-injection practices, yielding important insight to suboptimal injection practices identifying improvement areas for patient performance and healthcare team behaviour44,45.

Action research may involve observation and/or interview techniques and sets out to develop a product (policy, educational materials etc.) by engaging the expertise of the participants to solve a problem. This approach has been successfully applied to developing a handbook by patients for patients with rheumatoid arthritis46 and to develop goal roadmaps for the operational enhancement of scleroderma centers47.

Historical analysis is another application which examines, often historical and usually published narrative data, such as newspapers and journals for data relevant to answering a question in qualitative research. The expansion of digital blogs and forums could lead to an expansion of this tool in chronic illnesses. The patient experience of disease can also be captured in non-textual form as exemplified by examination of the later works of Klee, Renoir, Hugue and Gaudi who each expressed their experiences of living with debilitating health and fear of mortality at the hands of autoimmune diseases48–50.

Regardless of the chosen strategy, qualitative methods are at best implemented or supervised by those who might have received dedicated academic training such as medical anthropologists, psychologists, social workers, etc. or someone recognized as being experienced in this field; the inclusion of which is often a quality indicator of the research. Because the multi-disciplinary nature is an important quality indicator of the research, healthcare providers and lay people, such as patients, can be trained to implement the components of qualitative research such as information gathering and analytic methods. However qualitative research demands the same level of respect and rigor as other scientific endeavors in medical research; in fact it is arguably a more challenging task to crystalize the “true” voice when expressing both the common and disparate experiences of a group of subjects, whatever the context.

The Research Question

The careful construction of the research question is crucial to good yield of data and efficiency in both qualitative and quantitative research. A good question defines the goal of the data collection and frames the existing research gap while at the same time delineating the confines of the research scope (Tables 4–6). An excellent question guides research design, choice of methodology and supports project planning and assessing resources. Further it serves to rein in the focus when the qualitative exploration reveals so many interesting and tempting distractors; and finally a good research question facilitates the delivery of the published findings by framing the reportable content (publication) of the analysis and results.

Table 4.

Examples of General Topics for Qualitative Research in Healthcare

| Understanding barriers / facilitators to accessing or learning something (e.g. online patient portals, quality healthcare, obtaining appropriate therapy, improving physical function etc) |

| Motivation for behaviours (e.g. patient medication adherence, provider prescribing practices,providing health education and counselling etc.) |

| Social, home, employment or healthcare team dynamics (stress-related situations, communication etc) |

| Beliefs, perceptions or priorities (e.g. patient beliefs surrounding methotrexate use or vaccines, healthcare provider beliefs surrounding pain in osteoarthritis, patient priorities in healthcare provision etc.) |

Table 6.

Examples of Qualitative Research Questions

| To understand system-level and interpersonal factors of prolonged prednisone use and delay of DMARD optimisation in young African American women with systemic lupus erythematosus. |

| To identify barriers to early diagnosis of systemic lupus erythematosus of Hispanic population in Milwaukee. |

| To characterize the daily life experience of systemic sclerosis patients living with calcinosis. |

| What are the most disabling aspects to patients diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis in the first three years? |

| What are the expectations of scleroderma patients, patient families and scleroderma specialists in a scleroderma center of excellence? |

The subject of the research question deserves considerable thought; focusing on the most essential stakeholders to answer the question/s at hand. For certain research questions, the perspectives of very different stakeholders may be required to accurately and comprehensively address the issue. Further, sometimes a 360▫ perspective of all potential stakeholders is useful. This strategy is frequently used when developing disease specific Core Sets for the International Classification of Functioning, Health and Disability (ICF) and developed on the converging insights of patients, family members, physicians, rehabilitation therapists, social workers, and psychologists, such as in mixed methods approach in ankylosing spondylitis to develop a quantifiable health index51.

Focus Groups and Interviews

Interviews and focus groups are the main, most commonly used methods of data collection in healthcare related phenomenological research. They provide rich detail of personal perspective in narrative data form; however each method has different qualities and dynamics that generally yield different depths and expanses of insight. A combinations of approaches, applied in an iterative fashion can support researchers seeking rich and varied data to answer a specific research question. For instance, a series of interviews might initially collect insights that can be further explored in a focus group; or the focus group might generate themes that require more in-depth probing in an interview format. The choice of strategy depends, amongst other factors, on the sensitivity of the subject. Interviews and focus groups require a skill, sensitivity and sensibility to conduct and typically comprise unstructured or semi-structured interview techniques adhering to a planned topic or question guide (see below). Important environmental considerations, especially for people with rheumatic diseases, must include ease of access to a venue and comfort with attention to room temperature, seating, availability of water and proximity to lavatories as well as when participants are getting tired.

Focus groups induce narrative data through discussion of an issue or topic that is common to a group of people with shared experiences52,53. Focus groups facilitate discussion and debate amongst participants; clarifying convergent and divergent views expressed54. The group strategy helps to characterize common and divergent cultural and social experiences in healthcare – whilst simultaneously providing reassurance to group members by dispelling a sense of “nobody knows how I feel” in relation to the subject of interest. The group dynamics and interactions of a focus group can create a relaxed setting and also widen the range of response compared to individual interviews, as each member, in addition to sharing their own perspective, hears others’ perspectives processing them against their own perspective. This comparison with other perspectives arising in the group ignites a deepening of participants’ self-exploration and sharing53.

Group discussion also sparks recollection of details for participants that might have been forgotten or overlooked by the participant in an interview setting. Focus groups also provide an opportunity to capture language and phrasing that target populations adopt to describe experiences. The vocabulary and descriptive phrases can prove particularly valuable if goals include developing patient-reported outcome measures, patient education materials, or manuals for healthcare providers etc.40,55. The size and composition of the group will influence the narrative. A group that is too large may impair the depth of expression or completion of communication; and some participants may not have a chance to speak at all. Another important consideration when assembling groups is factors that might interfere with comfortable and free expression, for example, hierarchical differences when examining barriers in the operational flow of clinic, or gender when examining sexual health. In these situations, separate focus groups should accommodate each member-type (so-called strata).

Audio-recording with subsequent verbatim transcription of study data enables independent verification of the study findings3. The researcher or assistant should also take field notes to observe and document tone, emotionality and physical behaviors that emphasize, clarify, seemingly contradict or add to a participant’s voiced perspective.

Purposive sampling techniques to ensure broad participation from within the target patient population can be applied to maximize the transferability (external validity) of the study interpretation and the specific patient populations to which they pertain3. In contrast to quantitative research methods, diversity within the study population can be a strength as the findings are not necessarily meant to be transferable across large population groups3. A complete description of the study population (and the extent to which a priori purposive sampling framework was achieved), site and context provides clarity and context on the sample population to which the interpretations purport3.

Whether focus groups or individual interviews are adopted, an a priori purposive sampling framework can help ensure a representative sample of patients with respect to clinical phenotype and demographics, whilst also ensuring adequate diversity of the cohort in terms of ethnicity, geographic and cultural participation. Qualitative research methods do not adhere to traditional sample size calculations and generally involve smaller sample sizes than their quantitative counterparts. There is not a minimum number of interview subjects or focus groups for any given subject. Instead, the choice of qualitative research method and subject sample size is dictated by the research question and goal of achieving thematic saturation56. Large sample sizes are not always appropriate and can complicate analysis with a single case study design sometimes proving an adequate and effective method for tackling a specific research question7.

Qualitative researchers need to be alert to many of the same biases that befall quantitative research such as sampling, analysis and selective presentation of data42. The unique role of the investigator in data acquisition (e.g. interviewing style and topic guide) and their own personal characteristics (e.g. age, gender, social status, personality and health [disabled or able]) can influence the participant experience and the quality of data collection42,57. It is acknowledged that investigator’s personal experiences, values, perceptions and preconceived concepts influence the data acquisition process in semi-structured interview of focus group setting. Whilst the effects of this bias are not easily eliminated, investigators should use reflexive reporting to openly describe investigator’s preconceptions and how these assumptions were challenged or supported during the course of data collection and analysis3,55.

Topic/Question Guide Development and Application

The topic guide is a carefully constructed flow of the interview questions, which is the backbone of active data collection, and ideally should be published with the results of study. Interview questions are open-ended queries that should be clear, simple and easy to understand when posed out loud. If questions are more complex, consider choreographing pauses in the midst of the question to allow for comprehension and reflection before completing the question. After writing a question, ask it aloud to other research team members to afford opportunities to modify awkward-sounding questions. Poorly constructed questions, can cause the group to falter in momentum. The order of questions can be important, and is based on cultivating comfort and then fostering an openness of communication that might occur naturally when encountering new people in non-research daily life. Brief opening questions that are straightforward and easy for interviewee or group members to answer helps to establish rapport between interviewer/moderator and the interviewee/group allowing time for participants to feel comfortable with speaking are good to begin sessions. Subsequent transitioning questions continue to warm the participant to speaking as well as sharing one’s own and responding to others’ perspectives. Both of which serve to ease the discussion into the sharper focus on the central/key questions necessary to procure material that address the overall research question. A smaller number of key questions that target the data collection is likely to procure a higher quality and more comprehensive yield, than many key questions. In our research, we often use the technique of beginning certain key questions by asking the participant to ‘think back’. For example, ‘think back to the time, when you first new something was not right with your health (leaving a pause here), what were the changes to your health you noticed?. The application of this and similar techniques helps to guide the participant’s mind, placing them in the midst of the situation/experience of interest sensitizing the participant to re-experience and thus to more readily recall and share important details.

Back up and probe questions, are exactly what their names imply, and are used to keep a discussion progressing when group members might be shy or uncertain what to say or to follow a particular remark more deeply. In regard to probing remarks further, we avoid direct questions that might sound harsh, instead we might say, ‘that’s interesting, can you comment further on your remark?’ The tone of the moderator can make all the difference in the same words either creating defensiveness or sounding inviting. Our goal is to maintain a tone that is soft, friendly and interested. Eye contact with each participant is important and should be gentle reflecting the qualities of the prior sentence.

QUALITATIVE DATA ANALYSIS

Irrespective of the qualitative research method, the raw “data” is typically in narrative form and include transcripts, reflective notes and field notes together form the descriptive raw “data” of the research but cannot provide an interpretation 4,7 without rigorous analytic application.

The assembling of the analytical team is vital to the success and perceived quality of the study. A multi-disciplinary team with varying fields of expertise is exemplary affording opportunity to see the narrative in diverse perspectives. In the best situation, the team is led by someone with significant experience in conducting, supervising and, if possible, comfort in teaching qualitative methods. Regardless of the scientific discipline, with practice, the sensitivity and capability of the researcher deepens; and the data is only as reliable as the care, accuracy, and as much objectivity as the situation allows, as implemented by the researcher.

The most common approach to qualitative data analysis is grounded theory which is the purest of inductive approaches whereby the data is approached without preconceived codes by the researcher; thus the researcher analyzes with naïve eyes, allowing the data to speak for itself and to be the driver of the emerging framework58. The theories produced by the research are ‘grounded’ only in the data collected with no input from prior studies. Here, codes are developed as part of the on-going analytic process and they are modified and refined with new discoveries in the data. There is constant re-engagement with already coded sections, this dynamic which is part of most qualitative analyses called constant comparative. Although various approaches to systematic analysis of qualitative data exist, each involves the process of de-contextualisation (compiling repositories of shared experiences using individual components lifted from the data) and re-contextualisation (ensuring these defined experiences collate with the context from which they were originally identified to avoid issues around data fragmentation related de-contextualisation)7.

Virtually all qualitative analytic methods are derived from grounded theory. Other methods range from the start list method whereby the analysts develop a list of preconceived codes based on past studies to which new codes are added during the analysis59. Such approaches can help expedite the process when pre-existing data is available. At the far end, is the more deductive spectrum, with a definitive code list applied1,2,7,60. This method can be seen in the strict application of ICF coding to a focus group transcript. Such studies gauge frequency of occurrence and therefore sit on the borderline between qualitative and quantitative in nature. Analytic approaches are dictated by what is already known, what the question is, and the overall goal of the research.

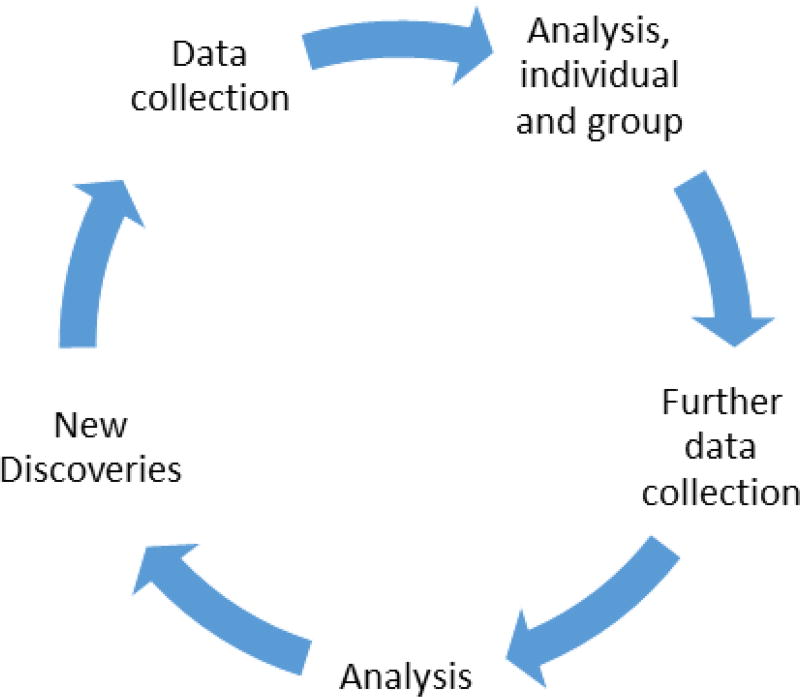

Analysis and interpretation of qualitative data is subjective and complex in nature, and a difficult, time-intensive task. It is an iterative process returning to the same script repeatedly as an individual analyst and as a team of analysts, with several independent analysts performing identical tasks on the same manuscript/s –repeatedly - and the team discussing and comparing coding of their individual efforts until the final analysis is settled (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Schematic of dynamics between data collection and analysis: a continually iterative in both intra- and inter- analysis that integrates new data and continually refines existing data.

The process of data analysis runs continuously in parallel with data acquisition as investigators are often present and active participants in the process of capturing experiences7. Analysis of the textual data needs to be systematic and thorough, and is therefore labor-intensive and time-consuming7. In striking contraindication to best quantitative practices, it is only through analysis that the halt of data collection is signaled. No new information arising in the analyses signals saturation has been reached and data collection can be discontinued.

The process begins with each analyst conducting an overview of a virgin transcript or recording, developing a receptiveness to the narrative as the first step in analysis, called familiarisation, allows concepts and themes to emerge2. This is achieved by reading the narrative in its entirety without yet attempting to code. After appreciating the scope, depth, and evolution of ideas, the manuscript is marked line by line for discrete ‘thought-units’ which are chunks of text that reflect a single concept. Thought-units may become filed under ‘codes’. Codes are labels consisting of a single word or discrete phrase that embody the essence of an important element of the narrative. Coding is an integral component in categorizing data and building a framework in a way that explains the diversity of experiences expressed in the data2,7. The identification of contrary experiences (“deviant” or negative opinions) enables investigators to interrogate their data with greater scrutiny, challenging and qualifying hypotheses, and refining interpretations7. Iterative testing on new or expanded samples can be used to confirm propositions derived from earlier analyses7.

Codes relevant to the research question are assembled into ‘code structures’. Code structures make categorical sense of emerging themes and is often displayed in outline form. Remembering that qualitative research is in all spheres an iterative process, the code structure will continually change and be modified until a final conceptual framework emerges after all the narratives have been coded. The framework is often used to provide both understanding of a phenomenology as well as future directions in research and care.

Alternatively, there is also a place for quantification in some strictly qualitative studies. Johnson et al, sought to understand physician expert perceptions of disease sub-typing in SSc using semi-structured interviews to collect qualitative insight and after implying qualitative analytic methods was able to calculate frequency of discrete codes correlated to individual participants61. This combined analytic technique was also used to understand the experiences of patients living with SSc-related calcinosis62; calculation of quantifiable frequency data facilitated understanding useful both in supporting normative assumptions as well as providing direction for actionable deliverables in care. In this case, learning that many patients routinely extract calcinosis by either self-instrumentation or warm water-soaking and extrusion, provoked the not-yet tested, but safe enough, anticipatory guidance regarding topical antibiotic use.

Several computer software programs are available to assist with organization, retrieval and re-organisation of data7. However, the rigour of the analysis and the development of the framework is dependent on the researcher only. If the software program interferes with the essential intimacy the researcher must have with the narrative, then it is best to revert to non-software-assisted analysis until those skills and sensibilities are more deeply set. The beauty of such software is to afford a researcher already intimate with the data, more avenues of exploration that confer a deeper intimacy of relational associations7.

QUALITATIVE RESEARCH AS AN EMERGING, ACCEPTED and ESSENTIAL METHOD IN HEALTH SCIENCES

Also, the quality indicators of quantitative methods are not the quality indicators of qualitative method requiring a unique set of indicators to ensure qualitative rigour1,3,63. Qualitative studies, expectedly, are not completely reproducible in another group of participants; given the smaller non-randomised purposeful sample sizes, and more personal nature; and as such the data inherently lacks unadulterated generalizability. In qualitative research, bias is virtually inescapable as analysis relies on the sensibilities of the analyst, though working hard to be objective, it is through empathy that coding is signaled. A very messy – very human – but scientifically sound business!

It is crucial that qualitative research methods consider many of the same quality standards governing quantitative research such as the validity (credibility), objectivity (confirmability) and generalizability (transferability) of the research findings3. Attention should also be drawn to the inevitable influence of bias on the relevance and validity of the study findings3. The researcher’s personal and professional preconceptions cannot be entirely negated but a complete and transparent account of the role and effect of the researcher at each step of the research process ensures bias can be accounted for in the interpretation of the study findings3.

Articles should include the relevance of the question and rationale of the approach, e.g. why qualitative and why the particular applications and sampling strategy selected as well as the principal of saturation. Inclusion of the actual interview guide as well as information on the analysis (e.g. number of coders, multi-disciplinary team, the code structure, management of divergent cases, etc is essential information when reporting the research64,65. Thus, to ensure rigor, protocols and guidelines have been presented. The most accepted of these is the COREQ. The COREQ is a 32-Item checklist that is used for pre-publication in some journals to assure qualitative research has been conducted with utmost rigour66. The COREQ consists of three domains with several questions under each: a. the study team, b. the study design, c. the analysis and findings66. The first study exploring the Raynaud experience in SSc demonstrating that current SSc PROMs do not capture the complex burden on morbidity67, is a clear example of data summarization formatted for ease of quality evaluation. It is important to recognize that some of the items are arguably controversial e.g. member-checking; but an overall guidance for quality assurance is necessary providing opportunity for the team to explain their process.

CONCLUSION

The acceptance of qualitative research has been a long road fraught with criticism but the scientific community has begun to appreciate the value of the unquantifiable. In many regards, the comparatively recent emergence of qualitative research methods in health science research reflects a return to pre-20th century medicine. Then, as now, clinicians appreciated the huge wealth of information that can be derived from observing and listening to patients recounting personal experiences of illness and qualitative research methods provide an important reminder of the complementary art and science of medicine. Over the course of this century, qualitative research has provided patients, carers and healthcare workers with a greater voice, ensuring their personal experiences contribute to knowledge development, clinical assessments and the shaping of future healthcare services42.

Table 5.

The anatomy of the Qualitative Research Question

| Inductive and incites exploration |

| Framed as a question (what, why, how) or an aim (infinitive verb, e.g. ‘To explain’, ‘To identify’ etc.) |

| Clear focus on singular and distinct phenomenon |

| Neutral language that is open |

| Stated subject of interest |

| Target patient population well-defined |

| Setting well-defined |

Key Points.

Qualitative research is an indispensable form of research vital information that impacts the biopsychosocial burden of chronic illness and in improved healthcare operations

Qualitative research is often used as a foundation or in complement to more traditional quantitative research methods to augment knowledge of rheumatic diseases

Qualitative research, though inherently subjective, is a robust process that can be evaluated and held to a high standard of quality

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

Neither author has any conflicts of interest to disclose relevant to the contents of this article.

References

- 1.Malterud K. The art and science of clinical knowledge: evidence beyond measures and numbers. Lancet (London, England) 2001;358(9279):397–400. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05548-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bradley EH, Curry LA, Devers KJ. Qualitative data analysis for health services research: developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Serv Res. 2007;42(4):1758–1772. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00684.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Malterud K. Qualitative research: standards, challenges, and guidelines. Lancet (London, England) 2001;358(9280):483–488. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05627-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.A G. The Heroism of Incremental Care. The New Yorker: Annals of Medicine. 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saketkoo LA. Wildflowers abundant in the garden of systemic sclerosis research, while hopeful exotics will one day bloom. Rheumatology. 2017 doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kex420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ong BN, Richardson JC. The contribution of qualitative approaches to musculoskeletal research. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2006;45(4):369–370. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kel022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pope C, Ziebland S, Mays N. Qualitative research in health care. Analysing qualitative data. BMJ (Clinical research ed.) 2000;320(7227):114–116. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7227.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suter LG, Fraenkel L, Holmboe ES. What factors account for referral delays for patients with suspected rheumatoid arthritis? Arthrit Rheum-Arthr. 2006;55(2):300–305. doi: 10.1002/art.21855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ballantyne PJ, Gignac MAM, Hawker GA. A patient-centered perspective on surgery avoidance for hip or knee arthritis: Lessons for the future. Arthrit Rheum-Arthr. 2007;57(1):27–34. doi: 10.1002/art.22472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kroll TL, Richardson M, Sharf BF, Suarez-Almazor ME. "Keep on truckin"" or '"it's got you in this little vacuum": Race-based perceptions in decision-making for total knee arthroplasty. Journal of Rheumatology. 2007;34(5):1069–1075. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klein D, MacDonald A, Drummond N, Cave A. A qualitative study to identify factors influencing COXIB prescribed by family physicians for musculoskeletal disorders. Fam Pract. 2006;23(6):659–665. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cml048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mann C, Dieppe P. Different patterns of illness-related interaction in couples coping with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;55(2):279–286. doi: 10.1002/art.21837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barlow JH, Cullen LA, Foster NE, Harrison K, Wade M. Does arthritis influence perceived ability to fulfill a parenting role? Perceptions of mothers, fathers and grandparents. Patient Education and Counseling. 1999;37(2):141–151. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(98)00136-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Backman CL, Smith LD, Smith S, Montie PL, Suto M. Experiences of mothers living with inflammatory arthritis. Arthrit Rheum-Arthr. 2007;57(3):381–388. doi: 10.1002/art.22609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Degotardi PJ, Revenson TA, Ilowite NT. Family-level coping in juvenile rheumatoid arthritis: Assessing the utility of a quantitative family interview. Arthritis Care and Research. 1999;12(5):314–324. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199910)12:5<314::aid-art2>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sanders C, Donovan JL, Dieppe PA. Unmet need for joint replacement: a qualitative investigation of barriers to treatment among individuals with severe pain and disability of the hip and knee. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2004;43(3):353–357. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rhodes LA, McPhillips-Tangum CA, Markham C, Klenk R. The power of the visible: the meaning of diagnostic tests in chronic back pain. Soc Sci Med. 1999;48(9):1189–1203. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00418-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Donovan JL, Blake DR. Qualitative study of interpretation of reassurance among patients attending rheumatology clinics: "just a touch of arthritis, doctor?". BMJ (Clinical research ed.) 2000;320(7234):541–544. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7234.541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haugli L, Strand E, Finset A. How do patients with rheumatic disease experience their relationship with their doctors? A qualitative study of experiences of stress and support in the doctor-patient relationship. Patient Educ Couns. 2004;52(2):169–174. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(03)00023-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ward V, Hill J, Hale C, Bird H, Quinn H, Thorpe R. Patient priorities of care in rheumatology outpatient clinics: a qualitative study. Musculoskeletal Care. 2007;5(4):216–228. doi: 10.1002/msc.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hay MC, Cadigan RJ, Khanna D, et al. Prepared patients: internet information seeking by new rheumatology patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59(4):575–582. doi: 10.1002/art.23533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arthur V, Clifford C. Rheumatology: the expectations and preferences of patients for their follow-up monitoring care: a qualitative study to determine the dimensions of patient satisfaction. J Clin Nurs. 2004;13(2):234–242. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2702.2003.00873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hale ED, Treharne GJ, Lyons AC, et al. "Joining the dots" for patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: personal perspectives of health care from a qualitative study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65(5):585–589. doi: 10.1136/ard.2005.037077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marshall NJ, Wilson G, Lapworth K, Kay LJ. Patients' perceptions of treatment with anti-TNF therapy for rheumatoid arthritis: a qualitative study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2004;43(8):1034–1038. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Woolhead GM, Donovan JL, Dieppe PA. Outcomes of total knee replacement: a qualitative study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2005;44(8):1032–1037. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thorstensson CA, Roos EM, Petersson IF, Arvidsson B. How do middle-aged patients conceive exercise as a form of treatment for knee osteoarthritis? Disabil Rehabil. 2006;28(1):51–59. doi: 10.1080/09638280500163927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Campbell R, Evans M, Tucker M, Quilty B, Dieppe P, Donovan JL. Why don't patients do their exercises? Understanding non-compliance with physiotherapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee. J Epidemiol Commun H. 2001;55(2):132–138. doi: 10.1136/jech.55.2.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Veenhof C, van Hasselt TJ, Koke AJA, Bijlsma JWJ, van den Ende CHM. Active involvement and long-term goals influence long-term adherence to behavioural graded activity in patients with osteoarthritis: a qualitative study. Aust J Physiother. 2006;52(4):273–278. doi: 10.1016/s0004-9514(06)70007-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sale JE, Gignac M, Hawker G. How "bad" does the pain have to be? A qualitative study examining adherence to pain medication in older adults with osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;55(2):272–278. doi: 10.1002/art.21853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tallon D, Chard J, Dieppe P. Exploring the priorities of patients with osteoarthritis of the knee. Arthritis Care and Research. 2000;13(5):312–319. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200010)13:5<312::aid-anr11>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hale ED, Treharne GJ, Norton Y, et al. 'Concealing the evidence': the importance of appearance concerns for patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2006;15(8):532–540. doi: 10.1191/0961203306lu2310xx. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Power JD, Badley EM, French MR, Wall AJ, Hawker GA. Fatigue in osteoarthritis: a qualitative study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2008;9:63. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-9-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adamson J, Gooberman-Hill R, Woolhead G, Donovan J. 'Questerviews': using questionnaires in qualitative interviews as a method of integrating qualitative and quantitative health services research. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2004;9(3):139–145. doi: 10.1258/1355819041403268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tugwell P, Bombardier C, Buchanan WW, Goldsmith CH, Grace E, Hanna B. The MACTAR Patient Preference Disability Questionnaire--an individualized functional priority approach for assessing improvement in physical disability in clinical trials in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1987;14(3):446–451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mouthon L, Rannou F, Berezne A, et al. Patient preference disability questionnaire in systemic sclerosis: a cross-sectional survey. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59(7):968–973. doi: 10.1002/art.23819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Administration USDoHaHSFaD. [Accessed 06/01/2016];Guidance for Industry: Patient-Reported Outcome Measures: Use in Medical Product Development to Support Labeling Claims. 2009 doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-4-79. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM193282.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Bottomley A, Jones D, Claassens L. Patient-reported outcomes: assessment and current perspectives of the guidelines of the Food and Drug Administration and the reflection paper of the European Medicines Agency. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(3):347–353. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chu LF, Utengen A, Kadry B, et al. "Nothing about us without us"-patient partnership in medical conferences. BMJ (Clinical research ed.) 2016;354:i3883. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i3883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saketkoo LA, Mittoo S, Huscher D, et al. Connective tissue disease related interstitial lung diseases and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: provisional core sets of domains and instruments for use in clinical trials. Thorax. 2014;69(5):428–436. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2013-204202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saketkoo LA, Mittoo S, Frankel S, et al. Reconciling healthcare professional and patient perspectives in the development of disease activity and response criteria in connective tissue disease-related interstitial lung diseases. J Rheumatol. 2014;41(4):792–798. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.131251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Morgan DL. Practical strategies for combining qualitative and quantitative methods: applications to health research. Qual Health Res. 1998;8(3):362–376. doi: 10.1177/104973239800800307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lempp H, Kingsley G. Qualitative assessments. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2007;21(5):857–869. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Minnock P, Kirwan J, Bresnihan B. Fatigue is a reliable, sensitive and unique outcome measure in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology. 2009;48(12):1533–1536. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kep287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Loyola-Sanchez A, Richardson J, Wilkins S, et al. Barriers to accessing the culturally sensitive healthcare that could decrease the disabling effects of arthritis in a rural Mayan community: a qualitative inquiry. Clinical rheumatology. 2016;35(5):1287–1298. doi: 10.1007/s10067-015-3061-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schiff M, Saunderson S, Mountian I, Hartley P. Chronic Disease and Self-Injection: Ethnographic Investigations into the Patient Experience During Treatment. Rheumatol Ther. 2017;4(2):445–463. doi: 10.1007/s40744-017-0080-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Prothero L, Georgopoulou S, de Souza S, Bosworth A, Bearne L, Lempp H. Patient involvement in the development of a handbook for moderate rheumatoid arthritis. Health Expect. 2017;20(2):288–297. doi: 10.1111/hex.12457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jaeger VK, Aubin A, Baldwin N, et al. Optimizing Scleroderma Centers of Excellence: Perspectives from Patients and Scleroderma (SSc) Experts. Arthritis & Rheumatology. 2014;66:S1180–S1181. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hinojosa-Azaola A, Alcocer-Varela J. Art and rheumatology: the artist and the rheumatologist's perspective. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2014;53(10):1725–1731. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ket459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pou MA, Diaz-Torne C, Azevedo VF. Manolo Hugue: from sculpture to painting due to arthritis. Reumatol Clin. 2011;7(2):135–136. doi: 10.1016/j.reuma.2009.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Suter H. Paul Klee's illness (systemic sclerosis) and artistic transfiguration. Front Neurol Neurosci. 2010;27:11–28. doi: 10.1159/000311189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kiltz U, van der Heijde D, Boonen A, et al. Development of a health index in patients with ankylosing spondylitis (ASAS HI): final result of a global initiative based on the ICF guided by ASAS. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(5):830–835. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.O'Sullivan R. Focus groups as qualitative research. Sociology. (2) 1998;32(2):418–419. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Morgan D. Focus Groups as Qualitative Research. Second. Thousand Oaks; California: 1997. [Accessed 2017/12/19]. http://methods.sagepub.com/book/focus-groups-as-qualitative-research. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Krueger R, Casey M. Focus Groups: A practical guide for applied research. 3. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hale ED, Treharne GJ, Kitas GD. Qualitative methodologies I: asking research questions with reflexive insight. Musculoskeletal Care. 2007;5(3):139–147. doi: 10.1002/msc.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Guest GBA, Johnson L. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Method. 2006;18:59–82. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Benestad B, Vinje O, Veierod MB, Vandvik IH. Quantitative and qualitative assessments of pain in children with juvenile chronic arthritis based on the Norwegian version of the pediatric pain questionnaire. Scandinavian Journal of Rheumatology. 1996;25(5):293–299. doi: 10.3109/03009749609104061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Weidenfeld and Nicolson; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. SAGE Publications; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stamm TA, Mattsson M, Mihai C, et al. Concepts of functioning and health important to people with systemic sclerosis: a qualitative study in four European countries. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(6):1074–1079. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.148767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Johnson SR, Fransen J, Khanna D, et al. There Is a Need for New Systemic Sclerosis Subset Criteria. A Content Analytic Approach. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2015;74:1141–1141. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Christensen AM, Khalique S, Cenac S, et al. Systemic Sclerosis (Ssc) Related Calcinosis: Patients Provide What Specialists Want to Learn Development of a Calcinosis Patient Reported Outcome Measure (Prom) Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2015;74:600–600. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mays N, Pope C. Qualitative research in health care. Assessing quality in qualitative research. BMJ (Clinical research ed.) 2000;320(7226):50–52. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7226.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Giacomini MK, Cook DJ. Users' guides to the medical literature: XXIII. Qualitative research in health care B. What are the results and how do they help me care for my patients? Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA. 2000;284(4):478–482. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.4.478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Giacomini MK, Cook DJ. Users' guides to the medical literature: XXIII. Qualitative research in health care A. Are the results of the study valid? Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA. 2000;284(3):357–362. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.3.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health C. 2007;19(6):349–357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pauling JD, Domsic RT, Saketkoo LA, et al. A multi-national qualitative research study exploring the patient experience of Raynaud’s phenomenon in systemic sclerosis. Arth Care Res. 2018 doi: 10.1002/acr.23475. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]