Abstract

Background/Objectives

Bariatric surgery produces robust weight-loss, however, factors associated with long-term weight-loss maintenance among adolescents undergoing Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery (RYGB) are unknown.

Subjects/Methods

Fifty adolescents (mean±SD age and BMI = 17.1±1.7yrs and 59±11kg/m2) underwent RYGB, had follow-up visits at 1-yr and at a visit between 5–12yrs following surgery (FABS-5+ visit; mean±SD 8.1±1.6yrs). A non-surgical comparison group (n=30; mean±SD age and BMI = 15.3±1.7yrs and BMI=52±8kg/m2) was recruited to compare weight trajectories over-time. Questionnaires (health-related and eating behaviors, health responsibility, impact of weight on quality of life, international physical activity questionnaire (IPAQ), and dietary habits via surgery guidelines) were administered at the FABS-5+ visit. Post-hoc, participants were split into 2 groups: long-term weight loss maintainers (n=23; baseline BMI=58.2kg/m2; 1-yr BMI=35.8kg/m2; FABS-5+ BMI=34.9kg/m2) and re-gainers (n=27; baseline BMI=59.8kg/m2; 1-yr BMI=36.8 kg/m2; FABS-5+ BMI=48.0kg/m2) to compare factors which might contribute to differences. Data were analyzed using generalized estimating equations adjusted for age, sex, baseline BMI, baseline diabetes status, and length of follow-up.

Results

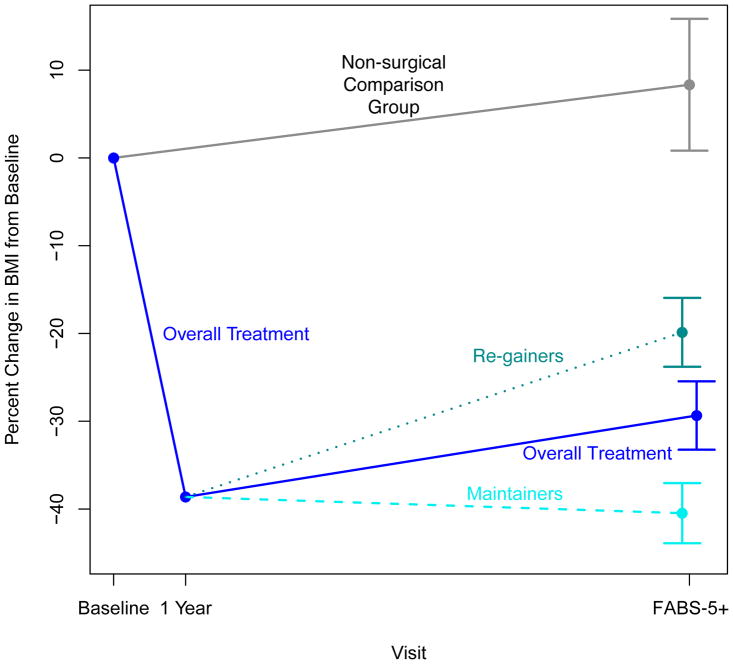

The BMI of the surgical group declined from baseline to 1-yr (−38.5±6.9%), which, despite some regain, was largely maintained until FABS-5+ (−29.6±13.9 % change). The BMI of the comparison group increased from baseline to the FABS-5+ visit (+10.3±20.6%). When the surgical group was split into maintainers and re-gainers, no differences in weight-related and eating behaviors, health responsibility, physical activity/inactivity, or dietary habits were observed between groups. However, at FABS-5+, maintainers had greater overall QOL scores than re-gainers (87.5±10.5 vs. 65.4±20.2, p<0.001) and in each QOL sub-domain (p<0.01 all).

Conclusions

Long-term weight outcomes for those who underwent weight loss surgery were superior to those who did not undergo surgical treatment. While no behavioral factors were identified as predictors of success in long-term weight-loss maintenance, greater QOL was strongly associated with maintenance of weight loss among adolescents who underwent RYGB surgery.

Keywords: Adolescent, Bariatric Surgery, Obesity, Maintenance, Lifestyle

Introduction

Adolescents with severe obesity are an expanding population with many serious comorbid conditions that accompany their excess adiposity.1, 2 Unfortunately, treatment options producing meaningful and sustainable weight-loss in this population are limited.3–5 Bariatric surgery leads to robust weight-loss accompanied by cardiometabolic improvements among adolescents with severe obesity.6–9 However, long term outcomes of bariatric surgery in adolescence have rarely been reported and factors driving sustainability of weight loss in adolescents are unknown. Understanding more about the long-term effects of bariatric surgery used in adolescence is of paramount importance to better inform clinicians, patients and their families, researchers, and insurance providers.

In adults with obesity, bariatric surgery results in substantial heterogeneity in weight-loss outcomes and the ability to maintain the nadir weight-loss acheived.10, 11 Preoperative factors such as sex,12 ethnicity,13 baseline weight,11, 14 physical activity levels,15 and eating behavior phenotypes14 have all been identified as important variables which may explain variability in weight-loss outcomes for adults. Additionally, several post-operative behavioral factors have been shown to influence weight-loss outcomes. These factors include adherence to food intake guidelines such portion size,16, 17 physical activity and inactivity,18 and self-weighing.17 Whether these post-operative factors influence weight-loss maintenance in the post-bariatric surgery setting among adolescents has yet to be examined.

The primary goal of this analysis was to examine whether self-reported, post-operative factors related to eating behaviors, physical activity patterns, health-related behaviors, family responsibility, and weight-related quality of life (QOL) were associated with long-term weight-loss maintenance among adolescents with severe obesity whom underwent bariatric surgery. Importantly, we additionally examined weight trajectories over the same time-course in a non-surgical comparison group in order to better understand the long-term weight characteristics of those adolescents who undergoing surgery versus those who opt for other treatments.

Methods

Data Collection of the Surgical Cohort

Fifty adolescents underwent Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery from May 2001 to February 2007 at a Cincinnati Children’s Hospital and Medical Center. Early outcomes19 and long-term outcomes of surgery in this cohort have been previously described.20 To conduct long-term follow-up assessments, the Follow-up of Adolescent Bariatric Surgery at 5 Plus years (FABS-5+) extension study was designed. FABS-5+ study staff located, recruited, and prospectively conducted a one-time, long-term study visit with this cohort. Inclusion criteria for FABS-5+ consisted of: any individual ≤21 years of age who underwent bariatric surgery at this institution between May 2001–February 2007 and exclusion criteria consisted of anyone unable to complete self-report forms due to developmental delay or death prior to long-term study visit.

Long-term follow-up study data were gathered by clinical research coordinators either at the Medical Center or in the participant’s home. For participants who chose to have a home visit, a trained examiner from Examination Management Services, Inc. (Dallas, TX) conducted visits. None of the long-term follow-up data were collected by members of the bariatric clinical treatment team. All data were obtained by direct measurement or obtained by a structured health interview. Height was measured to the closest 1.0 mm in standing position. Weight was measured in light clothing to the nearest 0.1 kg on an electronic scale (Tanita model TBF-310, Tokyo, Japan). Baseline and 1 year postoperative data (anthropometric, clinical features, biochemical measures, and questionnaires) were obtained by merging data from prior research databases or by abstraction from clinical records. Study procedures were approved by the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center Institutional Review Board.

Comparison Cohort

To compare the weight trajectories over time, a non-surgical comparison group was recruited from the multi-component, family-based pediatric weight management (PWM) program at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center (CCHMC). This group was comprised of 30 treatment-seeking adolescents with severe obesity who completed an initial medical assessment from December 2001 to December 2007. The PWM program at CCHMC for youth with overweight and obesity is designed to provide on-going follow-up care by a multi-disciplinary team. The initial treatment phase was 4–6 months and offered follow-up visits every 2 weeks, with on-going monthly follow-up visits thereafter. Treatment components included nutrition counseling, group exercise sessions, and behavior intervention therapies to improve eating habits and level of physical activity. However, participation by this cohort in CCHMC’s PWM was limited, with only 16 (60%) of patients completing a follow-up visit at 6 months, and 8 (27%) at 12 months. Therefore, exposure to a medically-supervised PWM program for this cohort was limited, with 14 (40%) of patients receiving no follow-up care for weight management during the 12-months post-baseline evaluation.

Comorbidity definitions

The diagnosis of diabetes mellitus at baseline was established by referring physician study investigators confirmed the diagnosis with corroborating clinical data taken from individual chart review. Confirmation included review of medication use for diabetes, HbA1c and fasting blood glucose analyses, and prior medical records from referring primary care physician and/or endocrinologist. At long-term follow up, diabetes was defined as either taking medications for diabetes, or HbA1c ≥ 6.5%, or if HbA1c was not available, by fasting glucose ≥ 7 mmol/l, or if laboratory values were unavailable, by self-report during the structured health interview.

Hypertension at baseline and follow-up was defined as systolic blood pressure or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 95th percentile for sex/height or if systolic blood pressure or diastolic blood pressure were ≥140mmHg or ≥90mmHg, respectively, or if medication was used for control of blood pressure.

Dyslipidemia was defined at baseline and follow-up as having either an elevated low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL) level (≥3.36 mmol/l if age <21 or ≥4.14 mmol/l if age ≥ 21), or depressed high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL) level (<1.03 mmol/l or <1.29 mmol/l for males and females, respectively), or elevated fasting triglyceride level (≥1.47 mmol/l if age <21 or >2.26 mmol/l if age ≥ 21), or if using a lipid-lowering medication.

Questionnaires

Health Behaviors and Expectancies Questionnaire

The health behaviors and expectancies questionnaire was developed and piloted as part of a post-graduate research project (unpublished). Questions were based on critical review of the bariatric literature in conjunction with health beliefs and locus of control and were reviewed by an expert panel prior to dissemination. Prospectively questionnaires were collected only at the FABS5+ visit in order to examine current behaviors with weight-loss maintenance. Participants completed a questionnaire developed to capture 3 domains specific to adolescent bariatric surgery: 1) Weight-related behaviors; 2) Eating behaviors; 3) Family health responsibility (e.g. whether primary health responsibilities are attributed to parents or to adolescent undergoing surgery). A list of questions for each domain can be found in Appendix 1 with a distribution of responses and how the questionnaires were scored. In brief, composite scores were calculated with higher scores of weight-related behavior indicating worse behaviors, higher scores of eating behavior indicating worse behaviors, and negative scores of health responsibilities indicate responsibilities being more attributable towards parents than adolescents. Participants were also asked about their long-term adherence to dietary guidelines given to them by the bariatric team. Example: eating 60+ grams of protein/day or limiting volume of solid food to 1.5 cup/meal. Adherence to guidelines was classified into 3 categories: 1) Ideal: Those who followed the recommendations on 5 out of 7 days per week; 2) Okay: Followed some but not all recommendations most days of the week; 3) Poor: Have not followed recommendations within the past 6 months. For analysis ‘ideal’ and ‘okay’ were combined and compared with ‘poor’.

Weight-related Quality of Life (IWQOL)

Participants completed the Impact of Weight on Quality of Life-Lite instrument which is a validated, 31-item, self-report measure of obesity-specific quality of life.21 In addition to an overall score for weight-related QOL, scores of the five sub-domains were reported: Physical Function, Self-esteem, Sexual Life, Public Distress, and Work.

International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ)

The IPAQ was scored and participants were classified into 3 standard categories22: 1) Inactive: Individuals who do not meet criteria for minimally active or health-enhancing physical activity are considered ‘insufficiently active’; 2) Minimally Active: Meeting one of the three following criteria: a) ≥3 days of vigorous activity of at least 20 min/day, or b) ≥5 days of moderate-intensity activity or walking of at least 30 min/day, or c) ≥5 days of any combination of walking, moderate-intensity or vigorous intensity activities achieving a minimum of at least 600 MET-min/week; 3) Health-enhancing physical activity: Individuals who exceed the minimum public health physical activity recommendations, and are accumulating enough activity for a healthy lifestyle. This includes: a) vigorous-intensity activity on at least 3 days achieving a minimum of at least 1500 MET-minutes/week or b) 7 or more days of any combination of walking, moderate-intensity or vigorous intensity activities achieving a minimum of at least 3000 MET-minutes/week. Physical inactivity and screen time were also examined using ancillary questions using a 30 day recall of average time spent in sedentary activities.

Post-surgical Weight-loss Maintainers and Re-Gainers

To examine the difference between those able to maintain their post-surgical weight-loss and those who gained back a proportion of their weight, adolescents were classified as maintainers if percent change in BMI from baseline to FABS-5+ visit was within 20% of the original change in BMI from baseline to the 1-year follow-up visit. For examples and further data on different percent cut-points (i.e. 5%, 10%, 15% etc.) refer to appendix 2.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive characteristics of the comparison and surgical cohort were calculated with mean (SD) or N (%). Differences between maintainers and re-gainers were evaluated using generalized estimating equations adjusting for age, sex, baseline BMI, baseline diabetes status, and follow-up time length with robust variance estimation for confidence intervals and P-values and to account for the longitudinal nature of our data. All analyses were conducted in R v3.2.3.23

Results

Table 1 shows baseline (pre-operative) characteristics of the surgical and comparison (non-surgical) group. The primary purpose of the non-surgical comparison group was to provide a reasonably well-matched group of treatment-seeking, adolescents with severe obesity to compare weight trajectories over time. Despite attempts to recruit a similar comparison group, baseline differences were apparent as the surgical group tended to be older, heavier, were more likely to be diabetic, and have pre-hypertension or hypertension.

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the surgery group and a non-surgical comparison group.

| Non-surgical Comparison Group | Surgery Group | |

|---|---|---|

| (N=30) | (N=50) | |

| Age at baseline (years) | 15.3 (1.72) | 17.1 (1.69) |

| Gender (female) | 22 (73.3%) | 31 (62.0%) |

| Height (cm) | 168 (7.4) | 171 (8.56) |

| Weight (kg) | 146 (23.7) | 174 (36.6) |

| Baseline BMI (kg/m2) | 52.0 (8.41) | 59.1 (10.6) |

| Race: | ||

| White | 14 (46.7%) | 44 (88.0%) |

| Black | 15 (50.0%) | 6 (12.0%) |

| Other | 1 (3.3%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Hispanic | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (4.0%) |

| Dyslipidemia | 23 (76.7%) | 41 (82.0%) |

| Diabetes | 3 (10.0%) | 8 (16.0%) |

| Pre-hypertension/Hypertension | 6 (20.0%) | 23 (46.0%) |

Abbreviations: BMI = body mass index

Values presented are mean (SD) or N (%) where indicated.

Table 2 displays the follow-up time and change in weight and BMI among the surgical and comparison group. Overall the mean follow-up time was similar between groups, 8.1±1.6 and 7.3±2.1 years, respectively. The surgical group showed a mean percent change in BMI from baseline to 1-year of −38.5±6.9%. From baseline to FABS-5+ the mean percent change in BMI for the surgical group was −29.6±13.9% due to mean weight regain (percent change in BMI) between 1-year and FABS-5+ of +14.9±22.1%. The comparison group showed an increase in percent BMI from baseline to FABS-5+ of +10.3±20.6%.

Table 2.

Change from baseline to 1-year and FABS-5+ in anthropometric characteristics of the surgery group and comparison group.

| Overall Groups | Surgical Group Split | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Comparison | Surgery | Re-gainers | Maintainers | |

| (N=30) | (N=50) | (N=27) | (N=23) | |

| Follow-up Time (years) | 7.3 (2.1) | 8.1 (1.6) | 8.2 (1.8) | 8.0 (1.4) |

| Baseline Weight (kg) | 146 (23.7) | 174 (36.6) | 176 (35.5) | 172 (38.4) |

| Weight Change from Baseline to FABS-5+ (kg) | +17.0 (33.7) | −50.7 (25.4) | −35.0 (20.0) | −69.2 (17.6) |

| Baseline BMI (kg/m2) | 52.0 (8.4) | 59.1 (10.6) | 59.8 (10.7) | 58.2 (10.6) |

| % Change BMI from Baseline to 1-Year | --- | −38.5 (6.9) | −38.3 (6.2) | −38.6 (7.8) |

| % Change BMI from Baseline to FABS-5+ | +10.3 (20.6) | −29.6 (13.9) | −20.1 (10.5) | −40.7 (7.9) |

| % Change BMI from 1-Year to FABS-5+ | --- | 14.9 (22.1) | 30.1 (17.3) | −2.9 (10.9) |

Abbreviations (in order of appearance): BMI = body mass index; FABS-5+ = Follow-up of Bariatric Surgery after at least 5 years.

Values presented are mean (SD) or N (%) where indicated.

Adolescents were classified as maintainers if % change in BMI from baseline to FABS-5+ visit was within 20% of the original change in BMI from baseline to the 1-year follow-up visit. For examples and further data refer to Appendix 1.

Due to the heterogeneity in weight regain from 1-year to FABS-5+ the surgical group was divided post hoc into 2 groups (Figure 1): surgical maintainers (n=23) and re-gainers (n=27). The maintainer and re-gainer groups displayed similar features of follow-up time, baseline BMI, and change in BMI from baseline to 1-year. However, the maintainer group continued to reduce their BMI from 1-year to FABS-5+ (−2.9±10.9%) in comparison to the re-gainers (+30.1±17.3%). Despite regaining a proportion of the lost weight, the re-gainers still showed a mean percent change in BMI from baseline of -20.1±10.5%.

Figure 1.

Percent change in BMI from baseline in the surgical treatment (overall, maintainers, and re-gainers) versus non-surgical comparison group. Adolescents were classified as maintainers if percent change in BMI from baseline to FABS-5+ visit was within 20% of the original change in BMI from baseline to the 1-year follow-up visit.

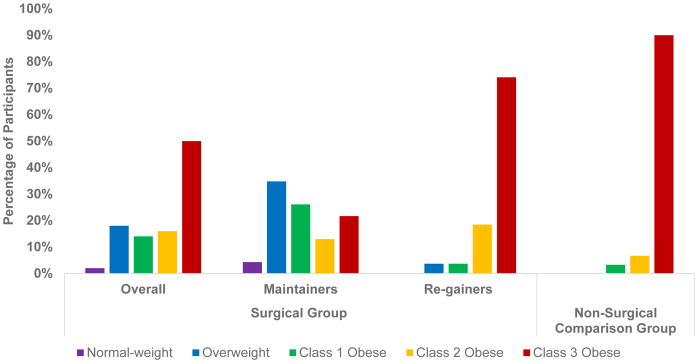

Figure 2 shows the obesity status (BMI based) distribution at the FABS-5+ visit for the surgical group overall was as follows: Normal-weight 1/50 (2%), overweight 9/50 (18%), class 1 obesity 7/50 (14%), class 2 obesity 8/50 (16%), class 3 obesity 25/50 (50%); for the Non-surgical comparison group: Normal-weight 0/30 (0%), overweight 0/30 (0%), class 1 obesity 1/30 (3.3%), class 2 obesity 2/30 (6.7%), and class 3 obesity 27/30 (90%); surgical re-gainers: Normal-weight 0/27 (0%), overweight 1/27 (3.7%), class 1 obesity 1/27 (3.7%), class 2 obesity 5/27 (18.5%), and class 3 obesity 20/27 (74.1%); surgical maintainers: Normal-weight 1/23 (4.3%), overweight 8/23 (34.8%), class 1 obesity 6/23 (26.1%), class 2 obesity 3/23 (13%), and class 3 obesity 5/23 (21.7%).

Figure 2.

Distribution of participants among obesity categories at FABS-5+ visit between groups.

To test the hypothesis that weight-related and eating behaviors, health responsibilities, and weight-related QOL would differ among surgical maintainers and those who regained weight after the first year, we dichotomized the surgical group by weight regain status and analyzed patient reported outcomes at the FABS-5 visit. Table 3 shows the adjusted mean differences (adjusted for age, sex, baseline BMI, baseline diabetes status, and follow-up time length) between groups. No statistically significant differences were observed between groups for weight-related behaviors, eating behaviors, or health responsibilities (p > 0.05 for all). However, the maintainers reported greater overall weight-related QOL and higher scores in each weight-related QOL sub-scale (Physical Function, Self-esteem, Sexual Life, Public Distress, and Work) as compared to those who regained weight over the long term beyond 1 year (p<0.01 all). The results did not differ in unadjusted analysis. Although the composite scores of the health-related behaviors were not statistically different between maintainers and re-gainers; re-gainers were more likely to consume more than 1.5 cups of food in any given meal and more likely to eat when bored (p<0.01 all; Appendix 3). We also noted sex and baseline BMI to be associated with differential outcomes in terms of QOL (Appendix 4). Males had higher self-esteem QOL than females (p=0.026) with a trend toward higher overall QOL (p=0.118) and public distress QOL (p=0.121). Males also had greater odds of computer use outside of work/school for 2+ hours than females (p=0.058) and a trend towards greater physical inactivity (p=0.151). Higher BMI at baseline was associated with worse health responsibilities (p=0.007), lower physical function QOL (p=0.010), and lower public distress QOL (p<0.001). No significant association between baseline BMI and physical activity/inactivity was observed.

Table 3.

Differences in weight-related and eating behaviors, health responsibilities, and quality of life between surgical re-gainers and maintainers.

| Surgical Groups | Re-gainers | Maintainers | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Mean (sd) | Mean (sd) | Adjusted Mean Difference* (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Weight-related Behaviors a | 16.2 (5.1) | 17.1 (3.8) | −1.5 (−3.7, 0.8) | 0.199 |

| Eating Behaviors b | 54.4 (9.4) | 53.2 (7.4) | 1.1 (−3.7, 5.8) | 0.668 |

| Health Responsibilities c | −1.0 (6.9) | −1.5 (6.7) | 0.6 (−2.9, 4.1) | 0.740 |

| Overall QOL d | 65.4 (20.2) | 87.5 (10.5) | −20.7 (−29.1, −12.3) | <0.001 |

| - Physical Function Sub-Scale | 68.9 (22.7) | 87.4 (15.0) | −16.4 (−25.8, −7.0) | <0.001 |

| - Self-Esteem Sub-Scale | 46.7 (28.0) | 77.3 (17.6) | −30.4 (−43.5, −17.3) | <0.001 |

| - Sexual Life Sub-Scale | 75.0 (27.7) | 92.1 (12.1) | −15.2 (−26.7, −3.8) | 0.009 |

| - Public Distress Sub-Scale | 64.3 (25.4) | 90.8 (14.7) | −24.9 (−34.9, −14.9) | <0.001 |

| - Work Sub-Scale | 80.1 (20.2) | 96.7 (6.4) | −15.3 (−23.4, −7.2) | <0.001 |

Adjusted for age, sex, baseline BMI, baseline diabetes status, and follow-up time length.

Composite score of weight-related behavior questions provided in Appendix 2 and 3, higher scores indicate worse behaviors.

Composite score of eating behavior questions provided in Appendix 2 and 3, higher scores indicate worse behaviors.

Composite score of health responsibilities related to adolescents and parents provided in Appendix 2 and 3, negative scores indicate responsibilities being more attributable towards parents than adolescents.

Impact of weight on quality of life questionnaire – lite version (IWQOL-Lite)

We additionally examined whether differences in physical inactivity and adherence to dietary recommendations from the bariatric team were present between groups (Table 4). In adjusted analysis, we observed no meaningful difference between surgical maintainers and re-gainers for physical inactivity or adherence to dietary recommendations. The results remained unchanged in unadjusted analysis.

Table 4.

Differences in physical activity and in dietary habits between surgical re-gainers and maintainers.

| Re-gainers | Maintainers | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sitting 3+ Hours Daily | 80.8% | 65.0% | 2.4 (0.6, 9.3) | 0.207 |

| Computer Use Outside of Work/School Daily for 2+ Hours | 37.5% | 29.4% | 1.3 (0.3, 5.6) | 0.711 |

| Physically Inactive a | 26.9% | 15.0% | 2.0 (0.4, 10.7) | 0.420 |

| Poor Dietary Habits b | 23.1% | 45.0% | 0.3 (0.1, 1.3) | 0.108 |

Data are presented percentages within each category with odds ratios (gainers as reference group = 1) calculated using robust variance estimations adjusted for age, sex, baseline BMI, baseline diabetes status, and follow-up time length.

Determined as the lowest physical activity level (meeting no recommendations) from the IPAQ.

Determined as not following the dietary recommendations provided by the bariatric surgery team within the past 6 months. Example: Eating 60+ grams of protein/day or limiting volume of solid food intake to 1 ½ cups/meal.

Conclusion

To our knowledge this is the first study to examine factors associated with long-term weight-loss maintenance among adolescents receiving Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. We observed a high degree of weight-loss maintenance, with nearly half of participants maintaining within 20% of their nadir weight-loss achieved. Despite some degree of heterogeneity in weight-loss maintenance following bariatric surgery, long-term weight outcomes in participants with severe obesity who underwent surgery were superior to a non-surgical comparison group. Although we expected to observe an association between lifestyle/behavioral factors and success in long-term weight-loss, no statistically significant behavioral predictors were found, though some physical activity and dietary habits appeared to be different between re-gainers and maintainers. These differences observed would be large enough to be of interest if we had more precision in our estimates with a larger study needed in order to confirm. Interestingly, those participants who did maintain weight loss reported significantly greater weight-related QOL overall and in each sub-domain of weight-related QOL.

Contrary to what has been observed in adults,18, 24 we did not observe statistically significant associations of physical activity levels or sitting-time with weight-loss maintenance despite there being potentially meaningful mean differences between groups. The majority of participants, similar to adults,25 were highly inactive and sedentary, regardless of group assignment. The adult literature is inconclusive as to whether exercise-focused interventions can improve weight-loss outcomes after bariatric surgery, with some studies showing greater weight-loss and maintenance,26, 27 while other studies showing no changes in body composition.28 Despite this, exercise interventions in adults following bariatric surgery have demonstrated effectiveness at improving fitness and insulin sensitivity.28, 29 Whether post-bariatric lifestyle-focused interventions can improve health and weight outcomes among adolescents has yet to be explored.

Despite the lack of association between dietary behaviors and weight loss maintenance on the whole, we did observe some potentially meaningful differences between groups in specific questions: portion size and eating while bored, which could have contributed to our findings. Mitchell and colleagues, in a large cohort of adults undergoing bariatric surgery found that 3 modifiable behaviors (self-weighing, not eating when full, and lack of eating continuously) were associated with more favorable weight change 3 years after bariatric surgery.30 While we did not measure self-weighing habits, we did observe adherence to a portion size of less than 1½ cups per meal (e.g. not eating when full) and being less likely to eat while bored (e.g. lack of eating continuously) associated with those who maintained weight-loss versus those who gained. Whether modification of these specific behaviors might lead to greater weight-loss maintenance requires further study.

We observed no association between health responsibilities (i.e. whether primary health responsibilities fall under the control of parents or adolescents responsibilities) and weight-loss maintenance. Health responsibility shifted towards being placed upon participants rather than parents among both surgical maintainers and re-gainers across time, as expected, as teens transitioned to early adulthood. Whether the similarities in transition of those responsibilities from parent to adolescent might may have accounted for the lack of association between groups was an able to be determined from this study.

Weight-related QOL has been previously shown to be substantially impaired in adolescents with severe obesity prior to undergoing bariatric surgery compared to youth with normal-weight, overweight, and obesity.31 Comparing the present study with values previously reported in similar populations, the weight-related QOL values observed in the surgical re-gainers are similar to the pre-operative bariatric youth with severe obesity, by contrast the weight-related QOL values of maintainers were similar to that of youth with obesity and overweight. Of additional interest, males tended to have higher overall QOL than females, particularly in the self-esteem domain. Whether these sex differences influenced outcomes or is suggestive of females requiring more intensive social support and behavioral modification post-surgery is worthy of investigation. Higher baseline BMI was also predictive of worse physical function and public distress QOL at FABS5+, suggesting that even with robust weight-loss provided by bariatric surgery issues due to very high BMI prior to surgery persist. We were unable to determine if the higher QOL is a byproduct of weight loss success or if improving weight-related QOL is a mechanism for achieving weight-loss maintenance, though this deserves further investigation.

The strengths of this study include the long duration of follow-up and direct anthropometric measurement and structured health interviews by trained staff. Limitations include the relatively homogenous population (high female and white representation), which hampers generalizability, and the fact that measures of lifestyle and behavior characteristics were available only at the long-term follow-up visit, precluding us from examining changes over time and addressing whether baseline characteristics predicted weight-loss maintenance. Further the measures of diet and physical activity were based on self- report rather than objective data and as such are subject to reporter bias. Due to the prospective nature of the study we were unable to reliably compare lifestyle and behavioral characteristics between the surgery and comparison groups.

Understanding factors contributing to long-term weight-loss maintenance in the post-bariatric surgery setting is vital in order for clinicians to provide patients and their families with tools necessary to achieve long-term weight success. Other than weight-related QOL, portion size, and eating while bored, for the majority of lifestyle and behavioral characteristics measured we were not able to discern an association with long-term weight-loss maintenance. Future work to elucidate modifiable behavioral and lifestyle characteristics predictive of long-term weight-loss maintenance among adolescents undergoing bariatric surgery should be a priority.

Acknowledgments

Funding: Dr. Rudser and Mr. Kaizer are supported in part by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences/NIH (UL1TR000114). The other authors received no funding for this project.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: Dr. Inge received research grant funding from Ethicon Endosurgery for this project. Dr. Kelly serves as a consultant for Novo Nordisk, Orexigen, and Vivus Pharmaceuticals but does not accept personal or professional income for these activities. Dr. Kelly receives research support in the form of drug/placebo from Astra Zeneca Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Fox serves as a site principal investigator for a clinical trial sponsored by Novo Nordisk Pharmaceuticals. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest. No honorarium, grant, or other form of payment was given to anyone to produce the manuscript.

Financial Disclosure: Dr. Fox receives salary support for her role as a site principal investigator for Novo Nordisk Pharmaceuticals. The other authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Bibliography

- 1.Skinner AC, Perrin EM, Moss LA, Skelton JA. Cardiometabolic Risks and Severity of Obesity in Children and Young Adults. New England Journal of Medicine. 2015;373:1307–1317. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1502821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Skinner AC, Skelton JA. Prevalence and trends in obesity and severe obesity among children in the United States, 1999–2012. JAMA pediatrics. 2014;168:561–6. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kelly AS, Barlow SE, Rao G, Inge TH, Hayman LL, Steinberger J, et al. Severe Obesity in Children and Adolescents: Identification, Associated Health Risks, and Treatment Approaches: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2013;128:1689–1712. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182a5cfb3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kelly AS, Fox CK, Rudser KD, Gross AC, Ryder JR. Pediatric obesity pharmacotherapy: Current state of the field, review of the literature, and clinical trial considerations. Int J Obes (Lond) 2016 doi: 10.1038/ijo.2016.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Danielsson P, Kowalski J, Ekblom O, Marcus C. Response of severely obese children and adolescents to behavioral treatment. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166:1103–8. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamapediatrics.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Inge TH, Courcoulas AP, Jenkins TM, Michalsky MP, Helmrath MA, Brandt ML, et al. Weight Loss and Health Status 3 Years after Bariatric Surgery in Adolescents. New England Journal of Medicine. 2016;374:113–123. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1506699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ryder JR, Edwards NM, Gupta R, Khoury J, Jenkins TM, Bout-Tabaku S, et al. Changes in Functional Mobility and Musculoskeletal Pain After Bariatric Surgery in Teens With Severe Obesity: Teen-Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery (LABS) Study. JAMA pediatrics. 2016;170:871–7. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.1196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kelly AS, Ryder JR, Marlatt KL, Rudser KD, Jenkins T, Inge TH. Changes in inflammation, oxidative stress, and adipokines following bariatric surgery among adolescents with severe obesity. Int J Obes (Lond) 2015 doi: 10.1038/ijo.2015.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Inge TH, Prigeon RL, Elder DA, Jenkins TM, Cohen RM, Xanthakos SA, et al. Insulin Sensitivity and beta-Cell Function Improve after Gastric Bypass in Severely Obese Adolescents. J Pediatr. 2015;167:1042–8e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang S, Stoll CT, Song J, Varela J, Eagon CJ, Colditz GA. The effectiveness and risks of bariatric surgery: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis, 2003–2012. JAMA Surgery. 2014;149:275–287. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2013.3654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Livhits M, Mercado C, Yermilov I, Parikh JA, Dutson E, Mehran A, et al. Preoperative predictors of weight loss following bariatric surgery: systematic review. Obes Surg. 2012;22:70–89. doi: 10.1007/s11695-011-0472-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adams ST, Salhab M, Hussain ZI, Miller GV, Leveson SH. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for morbid obesity: what are the preoperative predictors of weight loss? Postgrad Med J. 2013;89:411–6. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2012-131310. quiz 415, 416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buffington CK, Marema RT. Ethnic Differences in Obesity and Surgical Weight Loss between African-American and Caucasian Females. Obesity Surgery. 2006;16:159–165. doi: 10.1381/096089206775565258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robinson AH, Adler S, Stevens HB, Darcy AM, Morton JM, Safer DL. What variables are associated with successful weight loss outcomes for bariatric surgery after 1 year? Surgery for obesity and related diseases: official journal of the American Society for Bariatric Surgery. 2014;10:697–704. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2014.01.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bond DS, Evans RK, Wolfe LG, Meador JG, Sugerman HJ, Kellum JM, Demaria EJ. Impact of self-reported physical activity participation on proportion of excess weight loss and BMI among gastric bypass surgery patients. The American surgeon. 2004;70:811–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sarwer DB, Wadden TA, Moore RH, Baker AW, Gibbons LM, Raper SE, Williams NN. Preoperative eating behavior, postoperative dietary adherence, and weight loss after gastric bypass surgery. Surgery for obesity and related diseases: official journal of the American Society for Bariatric Surgery. 2008;4:640–6. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2008.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mitchell JE, Christian NJ, Flum DR, Pomp A, Pories WJ, Wolfe BM, et al. Postoperative Behavioral Variables and Weight Change 3 Years After Bariatric Surgery. JAMA Surg. 2016;151:752–7. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2016.0395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herman KM, Carver TE, Christou NV, Andersen RE. Keeping the weight off: physical activity, sitting time, and weight loss maintenance in bariatric surgery patients 2 to 16 years postsurgery. Obes Surg. 2014;24:1064–72. doi: 10.1007/s11695-014-1212-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miyano G, Jenkins TM, Xanthakos SA, Garcia VF, Inge TH. Perioperative outcome of Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: A children’s hospital experience. Journal of pediatric surgery. 2013;48:2092–2098. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2013.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Inge TH, Jenkins TM, Xanthakos SA, Dixon JB, Daniels SR, Zeller MH, Helmrath MA. Long-term outcomes of bariatric surgery in adolescents with severe obesity (FABS-5+): a prospective follow-up analysis. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(16)30315-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kolotkin RL, Crosby RD. Psychometric evaluation of the impact of weight on quality of life-lite questionnaire (IWQOL-lite) in a community sample. Quality of life research: an international journal of quality of life aspects of treatment, care and rehabilitation. 2002;11:157–71. doi: 10.1023/a:1015081805439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjostrom M, Bauman AE, Booth ML, Ainsworth BE, et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35:1381–95. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000078924.61453.FB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Team RC. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thomas JG, Bond DS, Phelan S, Hill JO, Wing RR. Weight-loss maintenance for 10 years in the National Weight Control Registry. American journal of preventive medicine. 2014;46:17–23. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coen PM, Goodpaster BH. A role for exercise after bariatric surgery? Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism. 2016;18:16–23. doi: 10.1111/dom.12545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shadid S, Jakob RC, Jensen MD. LONG-TERM, SUSTAINED, LIFESTYLE-INDUCED WEIGHT LOSS IN SEVERE OBESITY: THE GET-ReAL PROGRAM. Endocrine Practice. 2015;21:330–338. doi: 10.4158/EP14381.OR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rothwell L, Kow L, Toouli J. Effect of a Post-operative Structured Exercise Programme on Short-Term Weight Loss After Obesity Surgery Using Adjustable Gastric Bands. Obesity Surgery. 2015;25:126–128. doi: 10.1007/s11695-014-1323-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coen PM, Tanner CJ, Helbling NL, Dubis GS, Hames KC, Xie H, et al. Clinical trial demonstrates exercise following bariatric surgery improves insulin sensitivity. The Journal of clinical investigation. 125:248–257. doi: 10.1172/JCI78016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stegen S, Derave W, Calders P, Van Laethem C, Pattyn P. Physical Fitness in Morbidly Obese Patients: Effect of Gastric Bypass Surgery and Exercise Training. Obesity Surgery. 2011;21:61–70. doi: 10.1007/s11695-009-0045-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mitchell JE, Christian NJ, Flum DR, Pomp A, Pories WJ, Wolfe BM, et al. Postoperative behavioral variables and weight change 3 years after bariatric surgery. JAMA Surgery. 2016;151:752–757. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2016.0395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zeller MH, Inge TH, Modi AC, Jenkins TM, Michalsky MP, Helmrath M, et al. Severe obesity and comorbid condition impact on the weight-related quality of life of the adolescent patient. J Pediatr. 2015;166:651–9. e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]