Abstract

Purpose

We describe the key elements of early palliative care (PC) across the illness trajectory and examine whether visit content was associated with patient-reported outcomes and end-of-life care.

Methods

We performed a secondary analysis of patients with newly diagnosed advanced lung or noncolorectal GI cancer (N = 171) who were randomly assigned to receive early PC. Participants attended at least monthly visits with board-certified PC physicians and advanced practice nurses at Massachusetts General Hospital. PC clinicians completed surveys documenting visit content after each encounter. Patients reported quality of life (Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–General) and mood (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale and Patient Health Questionnaire-9) at baseline and 24 weeks. End-of-life care data were abstracted from the electronic health record. We summarized visit content over time and used linear and logistic regression to identify whether the proportion of visits addressing a content area was associated with patient-reported outcomes and end-of-life care.

Results

We analyzed data from 2,921 PC visits, most of which addressed coping (64.2%) and symptom management (74.5%). By 24 weeks, patients who had a higher proportion of visits that addressed coping experienced improved quality of life (P = .02) and depression symptoms (Depression subscale of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, P = .002; Patient Health Questionnaire-9, P = .004). Patients who had a higher proportion of visits address treatment decisions were less likely to initiate chemotherapy (P = .02) or be hospitalized (P = .005) in the 60 days before death. Patients who had a higher proportion of visits addressing advance care planning were more likely to use hospice (P = .03).

Conclusion

PC clinicians’ focus on coping, treatment decisions, and advance care planning is associated with improved patient outcomes. These data define the key elements of early PC to enable dissemination of the integrated care model.

INTRODUCTION

The dissemination of early palliative care (PC) models is an important priority in oncology. Randomized trials,1-6 systematic reviews,7-9 and meta-analyses10,11 show that PC improves quality of life (QOL), mood, and end-of-life care, especially when provided early after the diagnosis of advanced cancer. On the basis of this evidence, the ASCO clinical practice guidelines12 recommend early PC with cancer treatment for all patients with advanced cancer. Whereas most large health care systems have hospital-based PC programs, fewer have outpatient clinics.13-15 Hospital-based PC often focuses on symptom management and end-of-life decision making.16-18 In contrast, providing care in the ambulatory setting enables PC clinicians to establish longitudinal relationships with patients and their families, to help patients understand their prognosis and make decisions about their cancer care over time.19,20 Yet, published studies describing the content and nature of PC when provided throughout the course of illness are lacking.

To develop outpatient PC programs, clinicians require guidance on the essential elements of providing care for patients in the ambulatory care setting from diagnosis until death. A qualitative analysis21 using electronic health records (EHR) from a prior randomized trial2 of early PC integrated with oncology care in patients with advanced lung cancer demonstrated that PC clinicians established rapport with patients and addressed illness and prognostic understanding during initial visits; focused on symptoms and coping throughout the illness trajectory; and discussed end-of-life issues in final visits. This study highlighted some of the key differences in PC practice between inpatient and outpatient settings. Specifically, in the ambulatory care setting, PC clinicians established longitudinal relationships and proactively addressed patients’ concerns throughout the course of illness.

Although this study provided insights into the key components of early PC, it included only a retrospective analysis of clinician documentation from the EHR and lacked an examination of associations between the content of the PC visits and patient outcomes. Thus, in our recent randomized trial of early PC integrated with oncology care at Massachusetts General Hospital (Boston, MA),1 we prospectively collected data on the focus of PC visits over time. Here, we describe the content of PC visits across the illness trajectory and assess whether visit content was associated with changes in patients’ QOL, mood, and end-of-life care.

METHODS

Study Procedures

We examined prospective data from a randomized trial of early PC integrated with oncology care versus oncology care alone for patients newly diagnosed with advanced lung or GI cancer treated at Massachusetts General Hospital.1 Patients assigned to the intervention participated in at least monthly visits with a PC physician or advanced practice nurse throughout the course of illness. PC and oncology appointments were generally scheduled on the same day. If a scheduled outpatient visit did not take place and could not be scheduled within 4 weeks of the previous visit, the PC clinician contacted the patient via telephone. If intervention participants were hospitalized at the participating institution, they were followed by the inpatient PC team throughout their hospital admission. Although the PC clinicians practice per the National Consensus Project guidelines,22 they tailored visits to meet the individual needs of patients and families. The PC clinician completed an electronic survey after every visit detailing the content of the encounter.

Participants

Patients were eligible to participate if they were within 8 weeks of a diagnosis of incurable lung or noncolorectal GI cancer, ≥ 18 years old, and not already receiving PC services. We previously reported the study eligibility and screening procedures.1 Follow-up is ongoing, and this analysis includes data from patients in the intervention group with a minimum of 18 months of follow-up and their PC clinicians.

Measures

Clinician postvisit survey.

The investigative team developed the postvisit survey specifically for this trial to document the visit content. After each visit, PC clinicians completed electronic surveys indicating which topics they addressed from the following list: rapport, symptom management, coping with life-threatening illness, illness understanding and education, treatment decisions, advance care planning, and disposition to other facilities. Clinicians could select more than one content area. When a content area was selected, the clinician was prompted to indicate the specific focus. For example, if clinicians selected symptom management, they denoted which of the following symptoms they addressed: pain, dyspnea, depression, anxiety, insomnia, fatigue, delirium, nausea and vomiting, and other. If clinicians selected coping with life-threatening illness, they were prompted to indicate which of the following coping techniques they used: behavioral coping, spiritual coping, maintaining or redirecting hope, life review, counseling, referral to an outside provider, or other. Each selected focus triggered follow-up questions, such as how symptoms were addressed, medications prescribed, and referrals provided.

Patient demographic and clinical characteristics.

Participants reported their demographic characteristics at baseline. We reviewed patients’ EHRs to obtain additional clinical information (eg, cancer type and stage, treatments, comorbidities).

QOL.

Patient QOL was assessed at baseline and 24 weeks using the 27-item Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–General23 scale. Participants rated their well-being in the past 7 days across four subdomains (ie, physical, social, emotional, functional). Responses were summed to yield a total score, with higher scores indicating better QOL.

Mood symptoms.

Anxiety and depression symptoms were assessed at baseline and 24 weeks using the 14-item Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale (HADS).24 The HADS consists of one subscale for anxiety and one subscale for depression to measure symptom severity during the past 7 days. In addition, patients completed the nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9),25 which measures symptoms of major depression according to the criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition.

End-of-life care.

For decedents who received their end-of-life care at the participating institution (n = 125), we reviewed EHRs to identify receipt of any new chemotherapy regimen, hospitalization, or emergency department visit in the 60 days before death, as well as receipt of hospice care and the location of death.

Statistical Analyses

The analyses were conducted using SPSS version 22.0.0.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL) and Excel 2013 (Microsoft, Redmond, WA). Descriptive statistics were used to analyze frequencies, means, and standard deviations. Because the present analyses report exploratory outcomes, we used two-tailed tests with an α = .05 for all inferential statistics, rather than more conservative adjustments that increase the risk of type II errors.

Examining longitudinal variation in the content of PC visits requires thoughtful data reduction for two reasons. First, patients differed considerably in their number of PC visits, from a few to dozens. Second, patients’ needs and the content of PC visits may change not only as time moves forward, but also looking backward from the final visit before death.26 Accordingly, we grouped PC visits into seven ordered categories representing the first, second, third, middle, third to last, second to last, and final visits (Appendix Fig A1, online only). In analyzing the initial three visits, we excluded data from visits that were simultaneously among the final three visits. In analyzing the final three visits, we included only data from decedents. All data from the remaining middle visits were averaged within-patient to summarize the middle visits.

We used percentages to describe the proportion of visits within each time category that addressed a particular content area. The sum of percentages could exceed 100% because clinicians could select more than one content area per visit. For inferential tests, the Z-test for differences in proportions was used to compare the proportion of the initial three visits versus the final three visits addressing a particular content area. For the two most common content areas, we also used the Z-test to examine changes in focus from the initial three to final three visits.

Multiple regression was used to examine whether visit content was associated with changes in QOL and mood from baseline to the 24-week follow-up. On the basis of the literature,27-30 we hypothesized that symptom management and coping should contribute to QOL and mood. Thus, we entered the following two independent variables into the model simultaneously: the proportion of visits to date by 24 weeks focused on symptom management and the proportion focused on coping. We excluded rapport because it is nonspecific and the other content areas that were infrequently addressed during the first 24 weeks. Nonetheless, we conducted sensitivity analyses including these other content areas. Participants with three or fewer visits were excluded as nonrepresentative. Covariates in all models included age, sex, education level, cancer type, Charlson comorbidity index, baseline status of the outcome variable, and the total number of PC visits by 24 weeks. The study was powered for the aims of the randomized trial, and the present analyses were powered to detect small to modest effects (eg, standardized regression coefficient β ≈ 0.15) as statistically significant in regression analyses.

We calculated odds ratios to examine whether visit content was associated with end-of-life care for decedents. A separate logistic regression model was used for each dependent variable (eg, receipt of hospice). Five independent variables were entered into the model simultaneously, namely, the proportion of all visits addressing symptom management, coping, illness understanding, treatment decisions, and advance care planning. The two other content areas were excluded as a result of being nonspecific (rapport) or inherently associated with end-of-life care (disposition). As in the analyses of patient-reported outcomes, we excluded participants with fewer than three visits and adjusted the models for the covariates of age, sex, education level, cancer type, Charlson comorbidity index, and number of PC visits before death.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

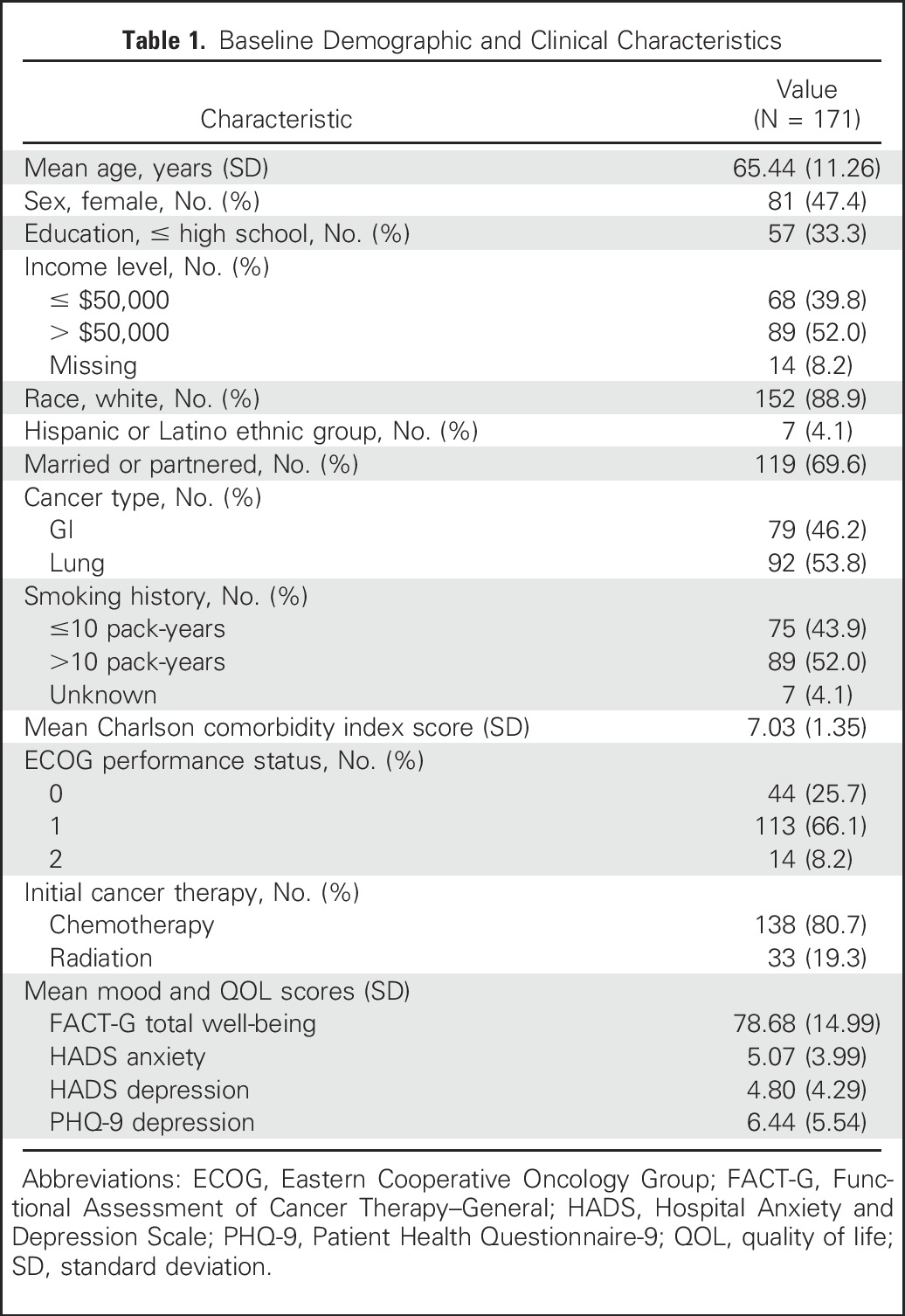

From May 2, 2011, to July 20, 2015, 175 of 350 patients enrolled onto the trial were randomly assigned to the intervention group. Of these, 97.7% of patients (171 of 175 patients) attended at least one PC visit, whereas four died or withdrew before participating in a visit (Fig A1). As shown in Table 1, participants had a mean age of 65.44 years (range, 26 to 87 years) and were predominantly white (88.9%).

Table 1.

Baseline Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

By the 18-month follow-up, participants attended 2,921 visits (mean per patient, 17.1 visits; range, one to 59 visits) with a PC clinician. Most participants (95.9%; 164 of 171 participants) had at least three visits. The mean visit duration was 34.04 minutes (standard deviation, 14.78 minutes), and visits were predominantly conducted in the ambulatory setting (83.2%), with some in the hospital (10.0%) or by telephone (6.7%). Forty PC clinicians conducted study visits, with 90.0% of the visits conducted by 10 clinicians and 47.2% of visits conducted by advance practice nurses. The majority of patients (84.2%; 144 of 171 patients) had at least one joint visit with the both the PC and oncology clinicians, with oncology clinicians present for 23.0% of all visits. Nearly all patients (97.7%; 167 of 171 patients) had a caregiver attend at least one visit, with caregivers attending 71.7% of all visits.

Content of PC Visits

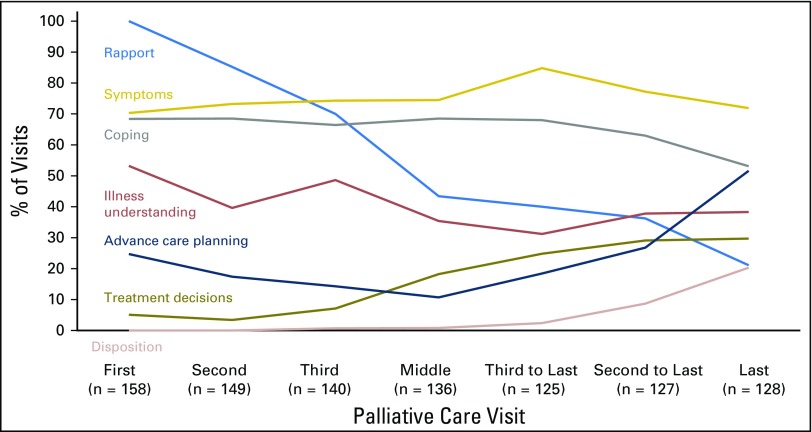

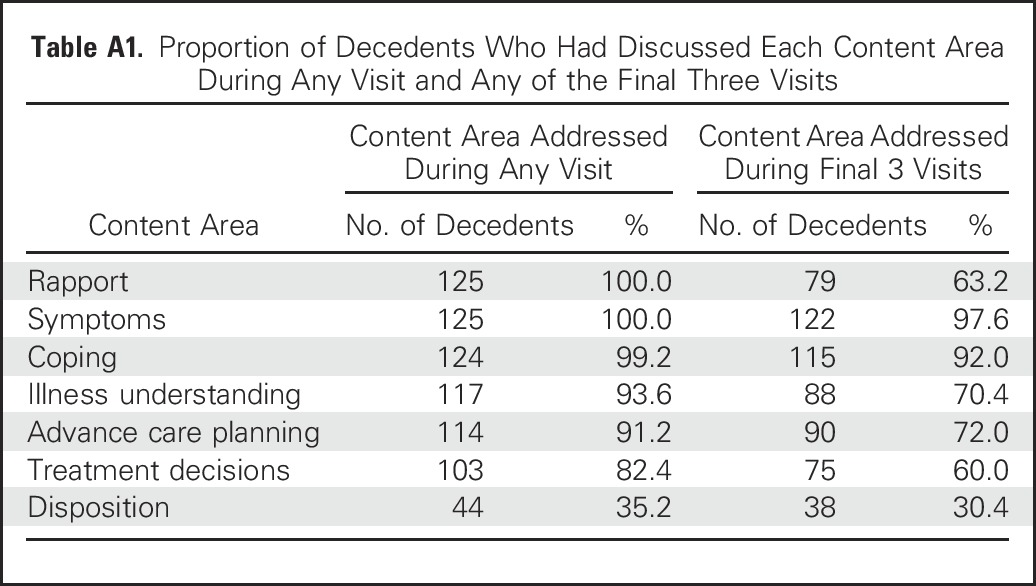

The most common topics PC clinicians addressed at visits were symptom management (74.6%; 2,179 of 2,921 visits) and coping with life-threatening illness (64.2%; 1,875 of 2,921 visits), but other visit content varied across the illness trajectory (Fig 1). From the initial three visits (sample, n = 158) to decedents’ final three visits (sample, n = 128), the proportion of visits emphasizing rapport decreased from 85.7% (383 of 447 visits) to 32.4% (123 of 380 visits; Z = −15.68; P < .001), and the proportion emphasizing illness understanding decreased from 47.2% (211 of 447 visits) to 35.8% (136 of 380 visits; Z = –3.32; P < .001). In contrast, from the initial three to final three visits, we observed an increase in the proportion of visits addressing advance care planning (19.0% [85 of 447 visits] v 32.4% [123 of 380 visits], respectively; Z = 4.42; P < .001), treatment decisions (5.1% [23 of 447 visits] v 27.9% [106 of 380 visits], respectively; Z = 8.98; P < .001), and disposition (0.2% [one of 447 visits] v 10.5% [40 of 380 visits], respectively; Z = 6.81; P < .001). Although the timing of content addressed varied, clinicians documented that they discussed most content areas at some point during the illness trajectory (Appendix Table A1, online only).

Fig 1.

Content of palliative care (PC) visits across the illness trajectory. PC clinicians recorded the content they addressed after each visit. Reported proportions for the final three visits are restricted to decedents. Reported proportions for the initial three visits exclude visits that were also among the final three visits. Reported proportions for middle visits represent averages across all available middle visits. Relative to the initial three visits, the final three visits increasingly addressed treatment decisions (P < .001), advance care planning (P < .001), and disposition (P < .001), but decreasingly addressed rapport (P < .001) and illness understanding (P < .001).

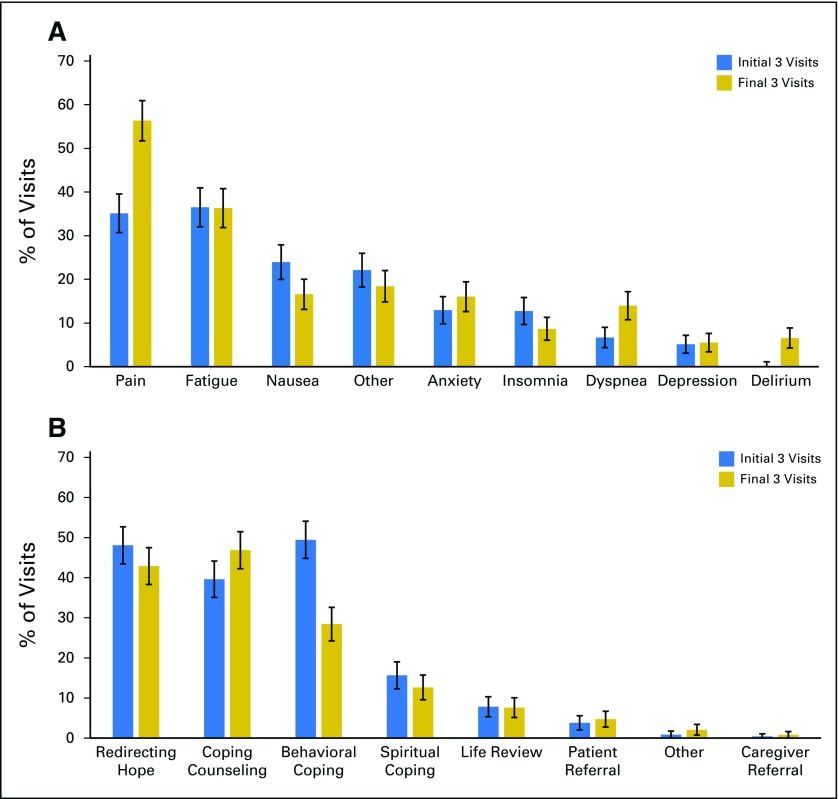

Although PC clinicians discussed pain, fatigue, and nausea most frequently with patients, the symptoms addressed varied over time (Fig 2). From the initial three visits to the final three visits, we observed an increase in visits that addressed pain (35.1% [157 of 447 visits] v 56.3% [214 of 380 visits], respectively; Z = 6.11; P < .001), dyspnea (6.7% [30 of 447 visits] v 13.9% [53 of 380 visits], respectively; Z = 3.47; P < .001), and delirium (0.0% [zero of 447 visits] v 6.6% [25 of 380 visits], respectively; Z = 5.51; P < .001), whereas nausea was addressed less often (23.9% [107 of 447 visits] v 16.6% [63 of 380 visits], respectively; Z = −2.61; P = .009). Clinicians most commonly managed symptoms through patient education and counseling (83.0%; 1,808 of 2,179 visits) or by initiating, adjusting, or discontinuing medications (43.4%; 946 of 2,179 visits). PC clinicians documented that they referred 9.9% of patients to social work, 8.2% to psychiatry, 6.4% to psychology, and 2.9% to pastoral counseling.

Fig 2.

Symptom management and coping support across the illness trajectory. (A) Over time, symptom management focused increasingly on pain (P < .001), dyspnea (P < .001), and delirium (P < .001) but less on nausea (P = .009). (B) Coping support shifted from behavioral coping strategies (P < .001) toward increased coping counseling (P = .04).

The PC clinicians typically provided coping support by redirecting hope, providing supportive counseling about the illness trajectory, and discussing behavioral strategies, but this also varied over time (Table 2). From the initial three visits to the final three visits, PC clinicians emphasized behavioral coping strategies less (49.4% [221 of 447 visits] v 28.4% [108 of 380 visits], respectively; Z = −6.16; P < .001) and counseling more (39.6% [177 of 447 visits] v 46.8% [178 of 380 visits], respectively; Z = 2.10, P = .04).

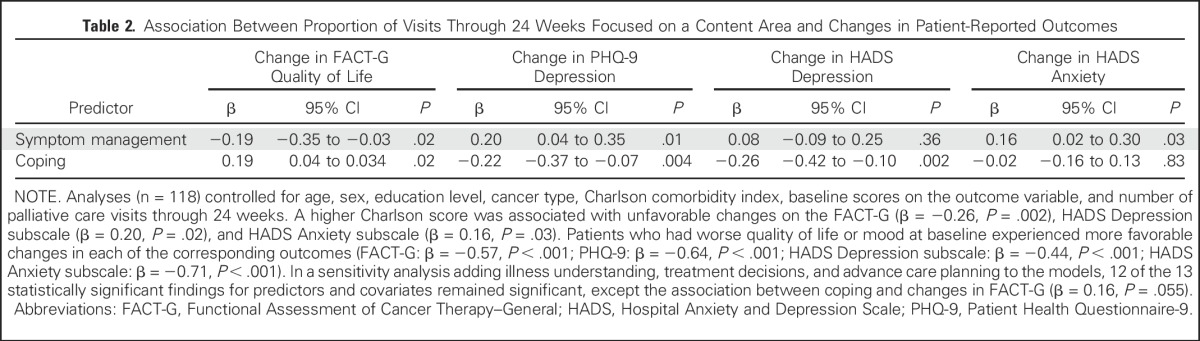

Table 2.

Association Between Proportion of Visits Through 24 Weeks Focused on a Content Area and Changes in Patient-Reported Outcomes

Associations With QOL and Mood

By 24 weeks (sample, n = 118), a higher proportion of visits to date addressing coping was associated with improvements in QOL (β = 0.19, P = .02) and depression symptoms (PHQ-9: β = −0.22, P = .004; HADS Depression subscale: β = −0.26, P = .002) from baseline to follow-up (Table 3). In contrast, a higher proportion of visits to date that focused on symptom management was associated with decrements in QOL (β = −0.19, P = .02) and worsening symptoms of depression (PHQ-9: β = 0.20, P = .01) and anxiety (HADS Anxiety subscale: β = 0.16, P = .03) from baseline to week 24. The other content areas were not significantly associated with changes in patient-reported outcomes.

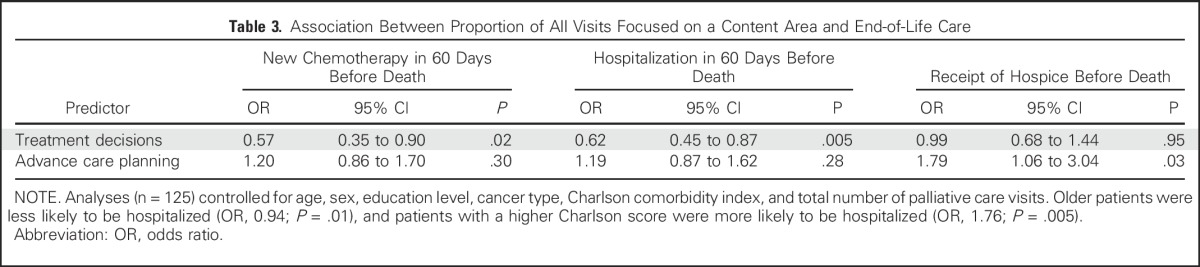

Table 3.

Association Between Proportion of All Visits Focused on a Content Area and End-of-Life Care

Associations With End-of-Life Care

Among decedents (sample, n = 125), 19.2% (24 of 125 patients) began a new chemotherapy regimen, 64.8% (81 of 125 patients) had a hospital admission, and 48.8% (61 of 125 patients) had an emergency department visit in the 60 days before death. In addition, 81.6% (102 of 125 patients) received hospice, and 57.6% (72 of 125 patients) died at home. As shown in Table 3, a higher proportion of all PC visits that addressed treatment decisions was associated with a lower odds of receiving new chemotherapy (odds ratio [OR], 0.57; P = .02) and having a hospital admission (OR, 0.62; P = .005) in the 60 days before death. A higher proportion of all PC visits that addressed advance care planning was associated with a higher odds of receiving hospice (OR, 1.79; P = .03). The proportions of visits addressing symptoms, coping, or illness understanding were not significantly associated with end-of-life care.

DISCUSSION

With increasing interest in disseminating the early, integrated palliative and oncology care model, data describing the nature and focus of PC clinicians’ interactions with patients are essential for the development of outpatient practices. The present investigation used data from the largest noncluster randomized controlled trial of outpatient PC,1 which we prospectively designed to assess the targets of PC visits across key content areas identified by an ASCO expert panel.12 Analyses demonstrate how the content of PC visits varies across the patients’ illness trajectory to respond to their needs as their health status changes. To our knowledge, this is the first study to link the content of PC visits to patient-reported outcomes and end-of-life care. Thus, these findings not only describe the salient elements of early PC but also help elucidate the potential mechanisms by which early PC improves patients’ outcomes.12,31-33

Addressing coping was a consistent hallmark of PC across the illness trajectory and was the only content area associated with improved patient-reported outcomes in this study. When PC clinicians spent a greater proportion of visits discussing coping during the first 24 weeks, patients reported improvements in both QOL and depression symptoms from baseline to follow-up. Among the coping techniques PC clinicians used, they discussed redirecting hope34,35 throughout the illness trajectory, behavioral coping strategies early on, and the direct provision of counseling more often in later visits. Interestingly, this parallels practices in psychotherapy in which cognitive strategies are increasingly used over behavioral strategies when patients have less control.36

Symptom management was also a hallmark of PC across the illness trajectory. PC clinicians focused most on pain and fatigue, with discussions about pain, dyspnea, and delirium increasing over time. They addressed symptom management more often in the first 24 weeks among patients who were experiencing worsening QOL and depression and anxiety symptoms, likely in response to the needs of patients with higher symptom burden. Notably, PC clinicians managed symptoms through patient education and counseling more often than medications. Although oncology clinicians are often appropriately prescribing and adjusting medications for symptoms, these data suggest that patients may benefit from additional education and counseling regarding the use of such medicines and support for nonpharmacologic strategies.

PC clinicians attended to treatment decisions and advance care planning increasingly during later visits, and focusing on these topics in a greater proportion of visits was associated with the delivery of what is commonly characterized as higher quality end-of-life care.6,22,37,38 We observed that PC clinicians often addressed the difficult topics of treatment decisions and advance care planning after focusing on less emotionally charged topics such as symptoms, coping, and illness understanding. Moreover, oncologists and caregivers participated in many PC visits. Early, longitudinal involvement of PC can increase opportunities for oncology and PC to work collaboratively to enhance patients’ ability to understand and cope with their illness, which may help patients and caregivers to better tolerate future difficult discussions about discontinuing chemotherapy and advance care planning.19,39,40

The limitations of this investigation should be noted. Associations between the visit content and patient outcomes were based on observational data within the intervention group of the randomized controlled trial, prohibiting any causal claims. Although we controlled for demographic and health characteristics, it is possible that the observed effects were influenced by factors outside of the PC visits, such as variation in psychosocial support. Another limitation was that this analysis was based on PC clinicians reporting about the nature of the visit, rather than using audio recordings of the visits to determine the content. PC clinician recall bias may underestimate or overestimate true associations between visit content and outcomes. In addition, although participants had similar baseline scores on patient-reported measures as patients with advanced cancer in other studies,41-43 they were predominantly white and educated and treated in an urban academic center. In other populations and settings, PC visits may need to prioritize topics differentially based on patients’ individual needs and may achieve different outcomes.

In summary, addressing symptom management and coping are key hallmarks of early PC across the illness trajectory, with an emphasis on coping associated with improvements in QOL and depression symptoms. Although emphasized more in later visits, focusing on treatment decisions and advanced care planning were associated with the delivery of higher quality end-of-life care. This study defines the key elements of early PC for patients with advanced cancer and provides a roadmap for building outpatient PC practices to enable dissemination of this care model.

Appendix

Fig A1.

Flow diagram.

Table A1.

Proportion of Decedents Who Had Discussed Each Content Area During Any Visit and Any of the Final Three Visits

Footnotes

Supported by the National Institute of Nursing Research (Grant No. R01NR012735, J.S.T.) and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (Grant No. U54GM104940, M.H.).

Presented, in part, at the 38th Annual Meeting of the Society of Behavioral Medicine, San Diego, CA, March 29-April 1, 2017.

The views expressed are the opinions of the authors and not the institutions or funders.

Clinical trial information: NCT01401907.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Michael Hoerger, Joseph A. Greer, Jennifer S. Temel

Collection and assembly of data: Michael Hoerger, Joseph A. Greer, Areej El-Jawahri, Emily R. Gallagher, Jennifer S. Temel

Data analysis and interpretation: All authors

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Defining the Elements of Early Palliative Care That Are Associated With Patient-Reported Outcomes and the Delivery of End-of-Life Care

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jco/site/ifc.

Michael Hoerger

No relationship to disclose

Joseph A. Greer

Research Funding: Pfizer (Inst)

Vicki A. Jackson

No relationship to disclose

Elyse R. Park

No relationship to disclose

William F. Pirl

No relationship to disclose

Areej El-Jawahri

No relationship to disclose

Emily R. Gallagher

No relationship to disclose

Teresa Hagan

No relationship to disclose

Juliet Jacobsen

No relationship to disclose

Laura M. Perry

No relationship to disclose

Jennifer S. Temel

Research Funding: Novartis/Pfizer (Inst)

REFERENCES

- 1.Temel JS, Greer JA, El-Jawahri A, et al. : Effects of early integrated palliative care in patients with lung and GI cancer: A randomized clinical trial. J Clin Oncol 35:834-841, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. : Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 363:733-742, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, et al. : Effects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer: The Project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial. JAMA 302:741-749, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bakitas MA, Tosteson TD, Li Z, et al. : Early versus delayed initiation of concurrent palliative oncology care: Patient outcomes in the ENABLE III randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 33:1438-1445, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M, et al. : Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: A cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet 383:1721-1730, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greer JA, Pirl WF, Jackson VA, et al. : Effect of early palliative care on chemotherapy use and end-of-life care in patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 30:394-400, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zimmermann C, Riechelmann R, Krzyzanowska M, et al. : Effectiveness of specialized palliative care: A systematic review. JAMA 299:1698-1709, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.El-Jawahri A, Greer JA, Temel JS: Does palliative care improve outcomes for patients with incurable illness? A review of the evidence. J Support Oncol 9:87-94, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Higginson IJ, Evans CJ: What is the evidence that palliative care teams improve outcomes for cancer patients and their families? Cancer J 16:423-435, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kavalieratos D, Corbelli J, Zhang D, et al. : Association between palliative care and patient and caregiver outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 316:2104-2114, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gaertner J, Siemens W, Meerpohl JJ, et al. : Effect of specialist palliative care services on quality of life in adults with advanced incurable illness in hospital, hospice, or community settings: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 357:j2925, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferrell BR, Temel JS, Temin S, et al. : Integration of palliative care into standard oncology care: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline update. J Clin Oncol 35:96-112, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dumanovsky T, Augustin R, Rogers M, et al. : The growth of palliative care in US hospitals: A status report. J Palliat Med 19:8-15, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hui D, Elsayem A, De la Cruz M, et al. : Availability and integration of palliative care at US cancer centers. JAMA 303:1054-1061, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hughes MT, Smith TJ: The growth of palliative care in the United States. Annu Rev Public Health 35:459-475, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gade G, Venohr I, Conner D, et al. : Impact of an inpatient palliative care team: A randomized control trial. J Palliat Med 11:180-190, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glare PA, Chow K: Validation of a simple screening tool for identifying unmet palliative care needs in patients with cancer. J Oncol Pract 11:e81-e86, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chong K, Olson EM, Banc TE, et al. : Types and rate of implementation of palliative care team recommendations for care of hospitalized veterans. J Palliat Med 7:784-790, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jackson VA, Jacobsen J, Greer JA, et al. : The cultivation of prognostic awareness through the provision of early palliative care in the ambulatory setting: A communication guide. J Palliat Med 16:894-900, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Temel JS, Greer JA, Admane S, et al. : Longitudinal perceptions of prognosis and goals of therapy in patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: Results of a randomized study of early palliative care. J Clin Oncol 29:2319-2326, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yoong J, Park ER, Greer JA, et al. : Early palliative care in advanced lung cancer: A qualitative study. JAMA Intern Med 173:283-290, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care : Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care (ed 3). Pittsburgh, PA: National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cella D, Hahn EA, Dineen K: Meaningful change in cancer-specific quality of life scores: Differences between improvement and worsening. Qual Life Res 11:207-221, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP: The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 67:361-370, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB: The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 16:606-613, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li Z, Tosteson TD, Bakitas MA: Joint modeling quality of life and survival using a terminal decline model in palliative care studies. Stat Med 32:1394-1406, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Greer JA, Jacobs JM, El-Jawahri A, et al. : Role of patient coping strategies in understanding the effects of early palliative care on quality of life and mood. J Clin Oncol 36:53-60, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.American Cancer Society : Cancer Facts & Figures 2017. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2017/cancer-facts-and-figures-2017.pdf

- 29.Faller H, Schuler M, Richard M, et al. : Effects of psycho-oncologic interventions on emotional distress and quality of life in adult patients with cancer: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol 31:782-793, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yennurajalingam S, Urbauer DL, Casper KL, et al. : Impact of a palliative care consultation team on cancer-related symptoms in advanced cancer patients referred to an outpatient supportive care clinic. J Pain Symptom Manage 41:49-56, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Greer JA, Jackson VA, Meier DE, et al. : Early integration of palliative care services with standard oncology care for patients with advanced cancer. CA Cancer J Clin 63:349-363, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meier DE, Beresford L: Outpatient clinics are a new frontier for palliative care. J Palliat Med 11:823-828, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brereton L, Clark J, Ingleton C, et al. : What do we know about different models of providing palliative care? Findings from a systematic review of reviews. Palliat Med 31:781-797, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Back A, Arnold R, Tulsky J. Mastering Communication With Seriously Ill Patients: Balancing Honesty With Empathy and Hope. Cambridge, United Kingdom, Cambridge University Press, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Norton SA, Bowers BJ: Working toward consensus: Providers’ strategies to shift patients from curative to palliative treatment choices. Res Nurs Health 24:258-269, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Heckhausen J, Wrosch C, Schulz R: A motivational theory of life-span development. Psychol Rev 117:32-60, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McNiff KK, Neuss MN, Jacobson JO, et al. : Measuring supportive care in medical oncology practice: Lessons learned from the quality oncology practice initiative. J Clin Oncol 26:3832-3837, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wright AA, Keating NL, Ayanian JZ, et al. : Family perspectives on aggressive cancer care near the end of life. JAMA 315:284-292, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Epstein RM, Street RL, Jr: Patient-Centered Communication in Cancer Care: Promoting Healing and Reducing Suffering. Bethesda, MD, National Cancer Institute, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hoerger M, Epstein RM, Winters PC, et al. : Values and options in cancer care (VOICE): Study design and rationale for a patient-centered communication and decision-making intervention for physicians, patients with advanced cancer, and their caregivers. BMC Cancer 13:188, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, et al. : The project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial to improve palliative care for rural patients with advanced cancer: Baseline findings, methodological challenges, and solutions. Palliat Support Care 7:75-86, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Voogt E, van der Heide A, van Leeuwen AF, et al. : Positive and negative affect after diagnosis of advanced cancer. Psychooncology 14:262-273, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Minton O, Strasser F, Radbruch L, et al. : Identification of factors associated with fatigue in advanced cancer: A subset analysis of the European palliative care research collaborative computerized symptom assessment data set. J Pain Symptom Manage 43:226-235, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]