Abstract

Human adenoviruses (AdV) cause generally mild infections of the respiratory and GI tracts as well as some other tissues. However, AdV can cause serious infection in severely immunosuppressed individuals, especially pediatric patients undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, where mortality rates are up to 80% with disseminated disease. Despite the seriousness of AdV disease, there are no drugs approved specifically to treat AdV infections. We report here that USC-087, an N-alkyl tyrosinamide phosphonate ester prodrug of HPMPA, the adenine analog of cidofovir, is highly effective against multiple AdV types in cell culture. USC-087 is also effective against AdV-C6 in our immunosuppressed permissive Syrian hamster model. In this model, hamsters are immunosuppressed by treatment with high dose cyclophosphamide. Injection of AdV-C6 (or AdV-C5) intravenously leads to a disseminated infection that resembles the disease seen in humans, including death. We have tested the efficacy of orally-administered USC-087 against the median lethal dose of intravenously administered AdV-C6. USC-087 completely prevented or significantly decreased mortality when administered up to 4 days post challenge. USC-087 also prevented or significantly decreased liver damage caused by AdV-C6 infection, and suppressed virus replication even when administered 4 days post challenge. These results imply that USC-087 is a promising candidate for drug development against HAdV infections.

INTRODUCTION

Human adenoviruses (HAdV) have a linear duplex DNA genome that encodes about 35 genes and is enclosed in an icosahedral protein capsid without a lipid membrane (reviewed in (Berk, 2013; Ison and Hayden, 2016; Lion, 2014; Wold and Ison, 2013). There are more than 70 types (genotypes, previously referred to as serotypes) of HAdV that are grouped into 7 species (A-G). Two Species C types discussed in this article are named HAdV-C5 and HAdV-C6 (for the sake of brevity, we will refer to these viruses as Ad5 and Ad6, respectively). Ad5 and Ad6 are ubiquitous, infect most children, and generally cause asymptomatic or fairly mild infection of the respiratory, gastrointestinal, ocular, or other tissues; the infections usually are self-limiting in healthy individuals.

The most serious HAdV infections occur in immunocompromised individuals (reviewed in (Ip et al., 2013; Ison and Hayden, 2016; Lion, 2014; Martinez-Aguado et al., 2015; Wold and Ison, 2013). Especially at risk are young children undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT), where the incidence of infection ranges from 5%–6% to 42%–47% depending on the study (Ison and Hayden, 2016; Lion, 2014; Sandkovsky et al., 2014). Mortality rates are as high as 26% with symptomatic infection and 80% for disseminated disease. Many AdV types can be isolated from these patients but Species C types predominate (Lion, 2014). With pediatric solid organ transplants, incidence is 4% to 38% in liver transplants, 7%–50% in heart and lung transplants, and 4% to 57% in small bowel recipients. Mortality rates are up to 54% in liver transplants and 18% in kidney recipients. In adult allo-HSCT, the incidence ranges from 3% to 15% (Lion, 2014).

With disseminated AdV disease, multiple organs are involved, and AdV DNA can be detected by PCR in peripheral blood, urine, bronchoalveloar fluid, and cerebral spinal fluid; death is associated with persisting or increasing AdV levels in peripheral blood and multi-organ failure (Lion, 2014). Risk factors include young age, receipt of T cell-depleted and/or mismatched grafts, use of the anti-CD52 antibody alemtuzumab, severe lymphopenia with low CD3+ T cell counts, acute graft versus host disease, early and persistent isolation of AdV from multiple sites, high initial AdV levels in the blood, and increasing AdV levels in serial stool samples beyond 106 virus copies per gram (Ison and Hayden, 2016; Lion, 2014; Lion et al., 2010; Sandkovsky et al., 2014).

There are no drugs approved specifically to treat AdV infections, despite the seriousness of disseminated AdV disease in immunocompromised individuals and in otherwise healthy individuals with life-threatening respiratory infections. Intravenous gamma globulins have been employed, and cidofovir (CDV) is used routinely in many transplant clinics (Ison and Hayden, 2016; Lion, 2014; Lion et al., 2010). CDV, an acyclic nucleoside phosphonate, is an analog of cytidine monophosphate. Following entry into the cell, it is converted by cellular anabolic kinases into CDV-diphosphate, which is an analog of cytidine triphosphate and used as a substrate by the AdV DNA polymerase more efficiently than by cellular DNA polymerases. Although it is not an obligate chain terminator, incorporation of the compound into AdV DNA eventually leads to termination of DNA synthesis. Recent studies report that CDV appears to be effective against HAdV not only in immunocompromised transplant patients, but also in adult immunocompetent patients with HAdV respiratory infections (Kim et al., 2015; Lee et al., 2017). A significant problem with CDV is poor cellular uptake (because of the charged phosphate group at physiological pH) (Holy, 2003). Also, it is a substrate for organic anion transporter 1, which leads to accumulation of CDV in renal tubules and nephrotoxicity (Cundy, 1999). Treatment with CDV is also associated with neutropenia and leukopenia that contribute to its dose limiting toxicity (Lalezari et al., 1997).

Brincidofovir (BCV, previously named CMX001) is being developed as an antiviral against AdV and a number of other DNA viruses (reviewed in (Florescu and Keck, 2014; Hostetler, 2009)). BCV (3-hexadecyloxy-1-propanol-cidofovir) is a lipophilic derivative of CDV (Hostetler, 2010). The lipid moiety not only improves oral bioavailability, but also facilitates the uptake of BCV into cells. Within cells, the lipid group is cleaved off by cellular phospholipase C, leaving charged CDV which cannot exit cells easily (Hostetler, 2010). Unlike CDV, BCV is not a substrate for the human organic anion transporter 1 and does not accumulate in renal tubules or cause nephrotoxicity (Ciesla et al., 2003). BCV inhibits the replication of almost all DNA viruses (Lanier et al., 2010), including multiple AdV types in cell culture, with EC50 values close to 0.02 μM (Hartline et al., 2005). In a case report, BCV suppressed a disseminated HAdV-C2 infection in a pediatric allo-HSCT patient (Paolino et al., 2011). In a recent randomized placebo-controlled multicenter phase II clinical trial, preemptive treatment with BCV was evaluated in 48 pediatric and adult allo-HSCT patients with asymptomatic HAdV viremia (Grimley et al., 2017). BCV treatment biweekly was reported to reduce all-cause mortality and also appeared to be associated with an early and marked decline in HAdV viremia in subjects with HAdV levels of >1,000 genome copies/ml at baseline, although the results were not statistically significant (Grimley et al., 2017). The most common adverse event associated with oral BCV treatment was diarrhea. The most common HAdVs observed in this trial were members of Species C (Grimley et al., 2017).

USC-087, an N-alkyl tyrosinamide phosphonate ester prodrug of HPMPA (Holy and Rosenberg, 1987a, b), the adenine analog of cidofovir, was evaluated against infection in cell culture by multiple HAdV types from different species. Orally administered USC-087 (Fig. 1A) was further evaluated for oral efficacy following intravenous (i.v.) infection by Ad5 or Ad6 in the permissive immunosuppressed Syrian hamster model developed in the Wold laboratory (Toth et al., 2008; Wold and Toth, 2012). In this model, young (to reflect the age of the target human population) Syrian hamsters are immunosuppressed by treatment with high-dose cyclophosphamide. The hamsters are then infected i.v. with Ad5 or Ad6, which replicate to high levels in the liver and other organs, causing pathology or mortality depending on the infecting dose of virus. Using this model, which closely resembles the disseminated HAdV infection and HAdV disease seen in immunocompromised human patients, we previously showed that BCV (Tollefson et al., 2014; Toth et al., 2008), CDV (Tollefson et al., 2014), ganciclovir (Ying et al., 2014b), and valganciclovir (Toth et al., 2015) are active against Ad5 replication and pathogenesis. We now report that orally-administered USC-087 is highly efficacious at a non-toxic dose against Ad5 or Ad6 replication, pathogenesis, and mortality following i.v. infection.

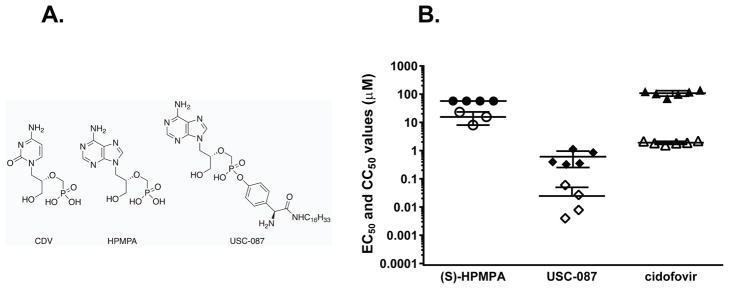

Figure 1. Structures (A) and in vitro anti-HAdV activity (B) of CDV, HPMPA and USC-087.

Antiviral activity (against HAdV-C5) and cytotoxicity were evaluated in 3–5 separate experiments and EC50 values (open symbols) and CC50 values (solid symbols) are shown with horizontal bars representing the mean and standard deviation of the data.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses

A wild-type human Ad6 isolate (VR-6; Tonsil 99) was purchased from ATCC and cultured and purified as described in (Tollefson et al., 2007). A wild-type Ad5 (named wt500) was plaque purified from a virus stock purchased from the ATCC. This isolate has been used in previous studies (Tollefson et al., 2014; Tollefson et al., 2017; Toth et al., 2015; Ying et al., 2014b). The titer of the virus stocks was determined by plaque assay (Tollefson et al., 2007). For the in vitro studies, wild-type stocks of HAdV-B3, HAdV-C5, HAdV-C6, HAdV-B7, and HAdV-D8 were purchased from ATCC and propagated on human foreskin fibroblast cells. Low passage primary human foreskin fibroblast cells were prepared and passaged as described previously (Prichard et al., 2013).

Antiviral compounds

USC-087 was prepared from commercially purchased HPMPA (Rasayan, Inc.; Angene, Inc) and Boc-L-tyrosine (Sigma-Aldrich) using the synthetic route of McKenna (McKenna et al., 2017). A sample of USC-087 made by the same route on a multigram-scale was supplied by a CRO, SRI International (Menlo Park, CA, USA) and then further purified at the USC laboratory by an automated flash chromatography method described herein (Supplemental data; 99%: 1H and 31P NMR, LC/MS, C,H,N elemental analysis; used in the in vivo studies). The CDV control for the in vitro studies was kindly provided by Gilead Sciences, Foster City, CA. CDV for in vivo studies was obtained from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID).

Antiviral Assays

In vitro antiviral assays were performed in primary human foreskin fibroblast cells and included a concurrent assessment of cytotoxicity using the same number of cells and at equivalent levels of compound exposure such that accurate selective index (SI) values could be obtained.

The cytopathic effect (CPE) reduction assays were performed in assay medium consisting of MEM with Earle’s salts, 2% FBS and standard concentrations of L-glutamine, penicillin, and gentamycin. Cells were seeded into 384-well microtiter plates and were subsequently incubated at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator for 24 h to allow the formation of confluent monolayers. Dilutions of test compounds were prepared in the plates in a series of 5-fold dilutions in duplicate wells to yield final concentrations that range from 300 to 0.1 μM or from 10 to 0.003 μM. Monolayers were then infected at a multiplicity of infection of 0.005 TCID50/cell with Ad5 and incubated further until 100% CPE was observed in the virus control wells. Cytopathology was determined by the addition of CellTiter-Glo reagent (Promega, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer’s suggested protocol. Concentrations of test compounds sufficient to reduce CPE by 50% (EC50) were interpolated from the experimental data. Cytotoxicity was also determined with CellTiter-Glo and concentrations of the compounds that decreased cell viability by 50% (CC50) were also calculated from the data and selective index (SI) values were calculated as the CC50/EC50 as a measure of antiviral activity.

Syrian hamsters

Syrian hamsters (Mesocricetus auratus) were purchased from Envigo (Harlan, Indianapolis, IN) at approximately 80 g body weight. All studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Saint Louis University and were conducted according to federal and institutional regulations.

Dosing Solution Preparation

For biological tests, USC-087 was formulated as a stirred suspension (24 h before use, experiments depicted in Figs. 2 and 3) or stable dispersion (experiments depicted in Fig. 4) in 0.5% aqueous CMC (carboxymethylcellulose sodium salt) after brief sonication (Branson 2510 sonicator) at room temperature. In the preferred procedure, CMC (low viscosity), (Sigma-Aldrich [Lot # SLBS7273]) (10.0 g) was added carefully to 1990 mL of deionized water in portions, and the mixture was gently shaken until homogenous (4 h at room temperature). To evaluate the stability of this dispersion, 12 mg of USC-087 in 12 mL of the CMC solution was prepared as described and monitored visually at room temperature (Fig. S8). No loss of homogeneity could be observed visually after 48 h.

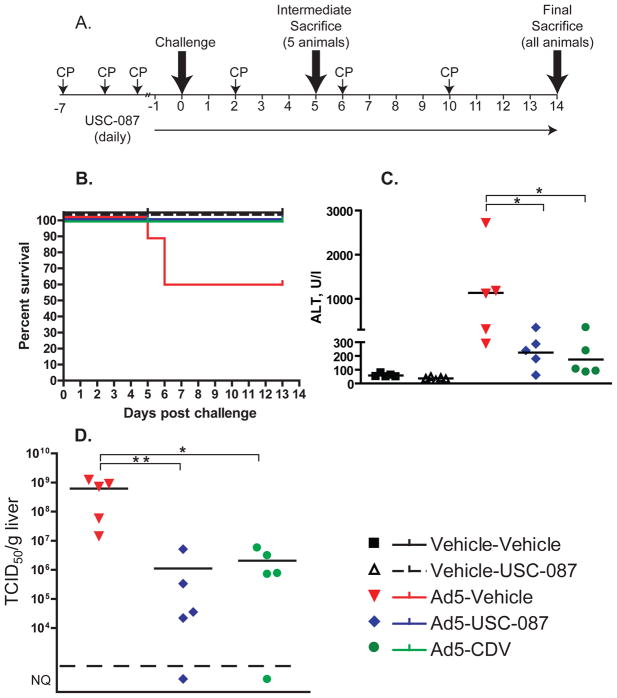

Figure 2. USC-087 administered prophylactically reverses Ad5-induced mortality and morbidity, mitigates Ad5-induced liver damage, and decreases virus burden in the liver of immunosuppressed female Syrian hamsters.

Ad5-infected hamsters were administered with vehicle or 10 mg/kg of USC-087 p.o. q.d., or with 20 mg/kg of CDV i.p. 3 times weekly; starting 1 day before challenge. A. Diagram of the experimental design. B. Survival. Ad5-Vehicle v. all other groups p=0.0161 (Log rank). C. Serum alanine aminotransferase levels. For this and similar subsequent figures, each symbol represents the value from an individual animal; the horizontal bar signifies the mean. D. Virus burden in the liver. NQ: not quantifiable (below the quantification threshold of 5×104 TCID50/g); *: p<0.05, **: p<0.01

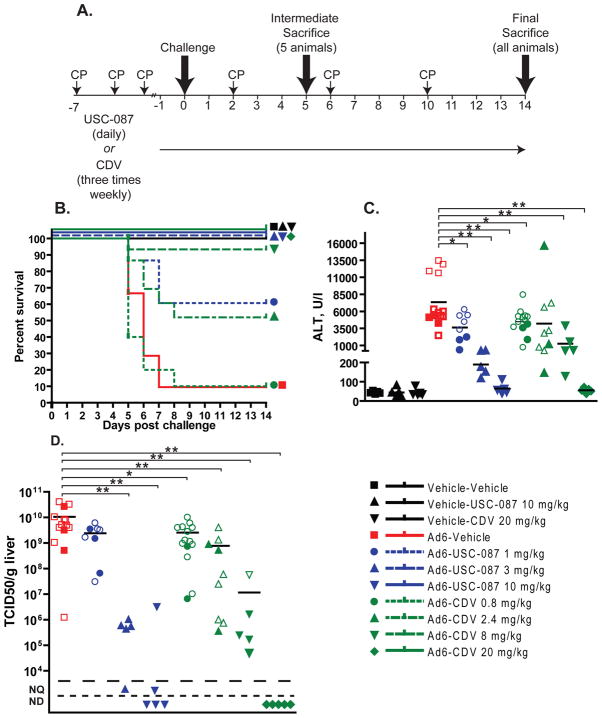

Figure 3. Prophylactically administered USC-087 is more effective in counteracting the effects of disseminated Ad6 infection in female Syrian hamsters than equimolar doses of CDV.

USC-087 was administered p.o. starting at one day prior to infection and continued daily for the course of the experiment. CDV was administered i.p. starting with an induction dose one day before virus challenge and continued with 3 weekly injections for the duration of the experiment. A. Diagram of the experimental design. B. Survival. Ad6-Vehicle v. Ad6-USC-087 1 mg/kg p=0.0047; Ad6-Vehicle v. Ad6-USC-087 3 mg/kg or Ad6-USC-087 10 mg/kg p<0.0001; Ad6-Vehicle v. Ad6-CDV 0.8 mg/kg p=0.4505; Ad6-Vehicle v. Ad6-CDV 2.4 mg/kg p=0.0178; Ad6-Vehicle v. Ad6-CDV 8 mg/kg p=0.0001; Ad6-Vehicle v. Ad6-CDV 8 mg/kg p<0.0001 (Log rank); C. Serum alanine transaminase levels. Empty symbols in this and subsequent graphs indicate that the sample was collected from a moribund animal sacrificed ahead of schedule. D. Virus burden in the liver. *: p<0.05, **: p<0.01; for the purposes of statistical calculations, a value of 5×104 TCID50/g was assumed for all not detectable and not quantifiable samples; NQ: not quantifiable; ND: not detectable

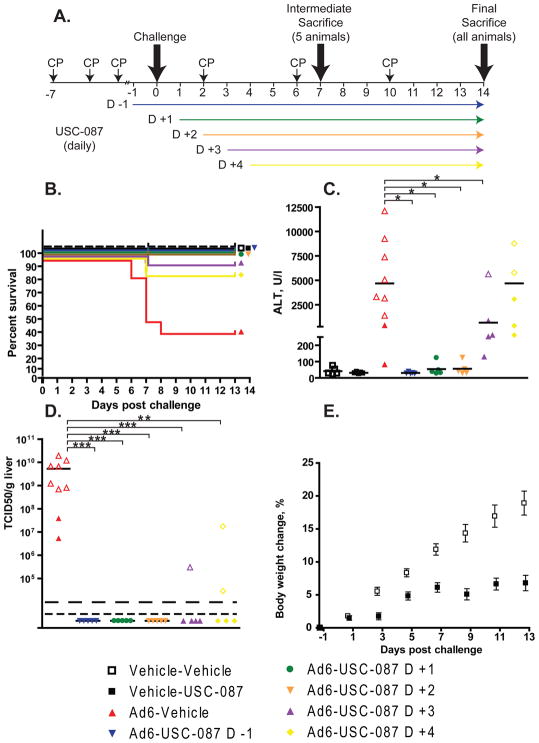

Figure 4. USC-087 reduces mortality and morbidity even when administered 3 or 4 days after virus challenge.

CP-treated hamsters were infected i.v. with Ad6 and left untreated or treated with USC-087 at 10 mg/kg p.o. q.d. Treatment with the drug started at 1 day before or 1, 2, 3, or 4 days after virus challenge. A. Diagram of the experimental design. B. Survival. n=15. Ad6-Vehicle v. all Ad6-USC-087 p<0.05 (Log rank) C. Serum ALT levels at 7 days post challenge n=5 to 9. *: p<0.05 D. Virus burden in the liver at 7 days post challenge. Empty symbols represent data collected from moribund animals. **: p<0.01, ***: p<0.001; for the purposes of statistical calculations, a value of 5×104 TCID50/g was assumed for all not detectable and not quantifiable samples), NQ: not quantifiable, ND: not detectable. E. Mean body weight changes for the Vehicle-Vehicle and the Vehicle-USC-087 groups. p<0.0001 (Two-Way ANOVA).

Infection of hamsters with adenovirus; treatment with USC-087 or CDV

The hamsters were immunosuppressed using cyclophosphamide (CP) (Toth et al., 2008). CP was administered intraperitoneally (i.p.) twice weekly for the duration of the study, starting with an induction of 140 mg/kg, and then at a dose of 100 mg/kg for all subsequent injections.

Virus challenge

After 3 injections of CP, Ad5 or Ad6 was injected i.v. (via the jugular vein) after anesthetizing the animals with ketamine/xylazine. Three experiments were performed; a pilot prophylactic experiment, a dose range-finding prophylactic experiment, and a therapeutic experiment, for which we used different challenge schedules, described below.

In the pilot experiment, we used female hamsters and Ad5 as the challenge virus. The challenge dose was 2×1011 plaque forming units (PFU)/kg, which is the LD50 for Ad5 with female hamsters.

In the dose range experiment we used Ad6, because it is more pathogenic than Ad5 (Tollefson et al., 2017). The challenge dose was 3×1010 PFU/kg, which is the LD90 of Ad6 for female hamsters.

For the therapeutic experiment, we used the most stringent conditions; challenging male hamsters, which are more susceptible to HAdV infection than females (Ying et al., 2018), with the more pathogenic Ad6 (Tollefson et al., 2017). The challenge dose was 1.7×1010 PFU/kg, which is the LD50 of Ad6 for male hamsters.

Treatment with antiviral compounds

USC-087 was administered through oral gavage (p.o.) in 1 ml of 0.5% carboxymethyl-cellulose (CMC) in an aqueous solution. For the prophylactic-type experiments (Pilot and Dose range), USC-087 administration started one day before virus challenge and continued daily for the duration of the experiment (Figs. 2A and 3A). For the therapeutic experiments, drug administration started one day before, or 1, 2, 3, or 4 days post challenge, and then continued daily for the course of the study (Fig. 4A).

For experiments in which CDV was used as a positive control, CDV was injected i.p. in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) starting one day before virus challenge, and then 3 times weekly for the duration of the experiment (Fig. 3A).

Endpoints

Treatment groups consisted of 15 animals. All hamsters were observed and weighed daily. Five hamsters of each group were sacrificed at 5 days (for the prophylactic study) or at 7 days (for the therapeutic study) post Ad6 challenge. At necropsy, serum and liver were collected. The virus was extracted from the liver and was quantified by 50% Tissue Culture Infectious Dose (TCID50) assay in HEK-293 cells (Toth et al., 2008), and serum was assayed for liver transaminase levels. The remaining ten hamsters in each group were used for a survival study.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 4 (GraphPad Software). Two-way ANOVA was used to compare body weight changes. For serum transaminase levels and virus burden in the liver, the overall effect was calculated using Kruskal-Wallis test, and comparison between groups was performed using Mann-Whitney U-test. P = 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Chemistry

1H and 31P NMR (Varian VNMRS-500 NMR spectrometer) and LC/MS (LCQ Deca XP Max). Analysis of the multigram scale sample of USC-087 supplied by the CRO indicated the presence of ~7% of phosphorous-containing impurities (Fig. S1). 1H NMR analysis (Fig. S2) also identified several impurities. LC/MS analysis (Fig. S3) suggested that one impurity was N-hexadecyl tyrosine amide, presumably from unreacted synthon (vd.(McKenna et al., 2017)).

To obtain highly purified USC-087 suitable for biological studies requiring multigram amounts of the prodrug, we used automated flash chromatography (ISCO Teledyne CombiFlash Rf+) on a silica gel column (Fig. S4). This method is convenient and practical for gram-scale preparations of highly purified USC-087. The isolated product satisfied C,H,N combustion analysis, was >99% pure by 1H (Fig. S5) and 31P NMR (Fig. S6) and had the expected MS peak (Fig. S7). It was unchanged after 1 month storage at room temperature or at 4 °C.

Tissue culture

The antiviral activity of USC-087 against Ad6 was evaluated in a series of in vitro CPE assays to identify the most potent analogs of S-HPMPA. These studies indicated that USC-087 was more than 600-fold more potent than HPMPA and more than 75-fold more potent than the CDV control (Fig. 1B). The enhanced potency of the compound was greater than the increased cytotoxicity and resulted in an improvement of the SI values from 3.8 to >20 when compared to HPMPA. The antiviral activity of the compound was also assessed against HAdV-B3, HAdV-B7, HAdV-C5, and HAdV-D8 with EC50 values of 0.015, 0.002, 0.025, and 0.035 μM, respectively; these values are similar to the antiviral activity against Ad6 (EC50 of 0.025 ± 0.026 μM). These data taken together indicated that USC-087 was a potent inhibitor of HAdV and that it warranted further study in animal models of infection.

Prophylactic administration of USC-087 prevents morbidity and mortality induced by Ad5 infection in Syrian hamsters

To assess the efficacy of USC-087 in vivo, we performed an experiment with hamsters challenged i.v. with Ad5 (Fig. 2A). The animals were immunosuppressed with CP, and sorted into 5 groups, two uninfected and three Ad5-infected. The uninfected (injected with virus vehicle, i.e. PBS) groups were: (1) virus vehicle i.v. and drug vehicle p.o. (Vehicle-Vehicle), and (2) virus vehicle i.v. plus 10 mg/kg USC-087 p.o (Vehicle-USC-087). Animals in the infected groups received 2×1011 PFU of Ad5 per kg i.v. There were three such groups, in which the animals received (1) Ad5 i.v. and drug vehicle p.o. (Ad5-Vehicle), (2) Ad5 i.v. plus 10 mg/kg USC-087 p.o. (Ad5-USC-087), or (3) Ad5 plus CDV i.p. (Ad5-CDV). CDV treatment was started with a 37 mg/kg inducer dose and continued at 20 mg/kg, 3 times weekly. Both USC-087 and CDV treatments started at 1 day before virus challenge, and then continued daily (q.d.) or 3 times weekly, respectively.

In-life observations

There were 5 treatment-related deaths in the study, all in the Ad5-Vehicle group (Fig. 2B). HAdV infection induced body weight loss, which was reversed by both USC-087 and CDV treatment (Fig. S9). A small, but significant decrease in body weight gain was observed for the Vehicle-USC-087 group compared to the Vehicle-Vehicle group (data not shown).

Necropsy

At 5 days post challenge, 2 of the 5 Ad5-infected, vehicle-treated hamsters had yellow mottled liver with enlarged gall bladder. The Ad5-infected hamsters sacrificed moribund had yellow, mottled, friable liver with enlarged gall bladder. The mottled appearance of the liver can indicate ongoing hepatocellular necrosis, while the enlarged gall bladder can result from reduced food intake or compression of the bile duct, all consequences of adenovirus infection. At 13 days post challenge, no significant findings were noted for any of the animals.

Clinical chemistry

At the Day 5 necropsy, serum was collected and was analyzed for transaminase levels. The serum alanine transaminase (ALT) levels were elevated for all the Ad5-infected, vehicle-treated hamsters (Fig. 2C). USC-087 or CDV treatment mitigated liver pathology; the serum ALT levels were only mildly elevated for the Ad5-infected, USC-087- and CDV-treated hamsters (Fig. 2C).

Virus burden in the liver

At 5 days post challenge, liver samples were collected at necropsy and were analyzed for infectious virus burden. Vehicle-treated, Ad5-infected animals had very high virus burden in the liver (Fig. 2D). Oral USC-087 (dosed at 10 mg/kg) or CDV (dosed at 20 mg/kg) i.p. reduced the virus burden in the Ad5-infected animals (Fig. 2D).

Orally dosed USC-087 is more efficacious than equimolar doses of i.p. dosed CDV

Female Syrian hamsters were treated with 1, 3, or 10 mg/kg of USC-087 p.o. (Ad6-USC-087 1, 3, and 10 mg/kg groups) or CDV doses i.p. that were molar equivalents of CDV matching the three USC-087 doses (Ad6-CDV 0.8, 2.4, and 8 mg/kg groups), or left untreated (Ad6-Vehicle group) (Fig 3A). Additionally, a group of animals was treated with the known effective i.p. dose of CDV (Ad6-CDV 20 mg/kg group). During the study, treatment with USC-087 and CDV continued daily or 3 times weekly, respectively. One day after the initiation of treatment with the drugs, the hamsters were injected with the LD90 (3×1010 PFU/kg) of Ad6. We chose Ad6 as the challenge virus to increase the rigor of the experiment because it is more pathogenic in hamsters than Ad5 (Tollefson et al., 2017). Hamsters were observed and weighed daily. At 5 days after challenge, 5 animals were sacrificed from each group, while the remaining 10 hamsters were sacrificed at 14 days after challenge or when they became moribund.

In-life observations

There were 35 treatment-related deaths in the study: 11 in the Ad6-Vehicle group, 5 in the Ad6-USC-087 1 mg/kg group, 12 in the Ad6-CDV 0.8 mg/kg group, 6 in the Ad6-CDV 2.4 mg/kg group, and 1 in the Ad6-CDV 8 mg/kg group (Fig. 3B). Notably, there were no deaths in the Ad6-USC-087 3 mg/kg group or the Ad6-USC-087 10 mg/kg group. Hamsters in the Ad6-infected groups lost weight from the onset of the study; USC-087 and CDV treatment reversed body weight loss for Ad6-challenged hamsters in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. S10). A small, but significant decrease in body weight gain was observed for the Vehicle-USC-087 group compared to the Vehicle-Vehicle group (data not shown).

Necropsy

At 5 days post challenge, 5 of the 5 Ad6-infected, vehicle-treated hamsters scheduled for sacrifice had yellow mottled liver with enlarged gall bladder. There were 4 of 5, 5 of 5, 3 of 5, and 2 of 5 animals with such pathology in the Ad6-USC-087 1 mg/kg, Ad6-CDV 0.8 mg/kg, Ad6-CDV 2.4 mg/kg, and Ad6-CDV 8 mg/kg groups, respectively. No gross pathology was observed with the animals in the Ad6-USC-087 3 mg/kg, Ad6-USC-087 10 mg/kg, or Ad6-CDV 20 mg/kg groups. The Ad6-infected hamsters sacrificed moribund had yellow, mottled, friable liver with enlarged gall bladder. At 14 days post challenge, no significant findings were noted for any of the animals.

Clinical chemistry

At the Day 5 necropsy, serum was collected and was analyzed for transaminase levels. Data collected from animals that were sacrificed moribund between Days 5 and 8 are also included. The serum alanine transaminase (ALT) levels were elevated for all the Ad6-infected, vehicle-treated hamsters (Fig. 3C). USC-087 or CDV treatment mitigated liver pathology in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3C).

Virus burden in the liver

At 5 days post challenge, liver samples were collected at necropsy and were analyzed for infectious virus burden. Data collected from animals that were sacrificed moribund between Days 5 and 8 are also included. Vehicle-treated, Ad6-infected animals had very high virus burden in the liver (Fig. 3D). USC-087 or CDV treatment of the Ad6-infected animals reduced the virus burden in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3D).

Therapeutic administration of USC-087 prevents morbidity and mortality induced by disseminated Ad6 infection in immunosuppressed male Syrian hamsters

To test for possible sex differences, this experiment was performed using male animals. The animals were immunosuppressed, and then injected i.v. with vehicle or the LD50 of Ad6 (for male hamsters: 1.7×1010 PFU per kg). We administered USC-087 p.o. at 10 mg/kg q.d., starting at 1 day before, or 1, 2, 3, or 4 days after Ad6 injection (groups Ad6-USC-087 D -1, D +1, D +2, D +3, D +4, respectively) (Fig. 4A). An Ad6-infected group that did not receive drug, and groups that received virus vehicle and drug vehicle only or virus vehicle plus drug (started at 1 day before challenge) were used as controls.

The body weights and any signs of morbidity of the animals were recorded daily. At 7 days post challenge, 5 hamsters of each group (designated at the start of the experiment) were sacrificed; the remaining 10 hamsters were sacrificed at 14 days post challenge. Hamsters that became moribund before Day 14 were sacrificed as needed.

In life observations

We observed 55% mortality in the Ad6-Vehicle group, while no deaths occurred in the groups that received USC-087 starting from 1 day before or 1 or 2 days after challenge (Fig. 4B). We saw 10% and 15% mortality in the groups in which treatment started 3 or 4 days post challenge, respectively (Fig. 4B). Ad6-injected animals started losing weight at around 4 to 5 days post challenge (data not shown). The body weight loss was greatest in the Ad6-Vehicle group. By 8 days post challenge, Ad6-infected hamsters that received USC-087 starting from 1 day before or 1 or 2 days after challenge had mostly recovered and showed minimal body weight loss compared to untreated animals (Fig. S11). Drug treatment starting 3 or 4 days post challenge had a mitigating effect.

Necropsy

At 7 days post challenge, all the animals in the Ad6-Vehicle group, 1 in the Ad6-USC-087 D +3 group, and 2 in the Ad6-USC-087 D +4 group had yellow mottled liver with enlarged gall bladder. No such pathology was seen in the Ad6-USC-087 D-1, D +1, or D +2 groups. The hamsters sacrificed moribund had yellow, mottled, friable liver with enlarged gall bladder. At 14 days post challenge, no significant HAdV infection-related findings were noted for any of the animals.

Serum chemistry

Serum was collected at the 7 day sacrifice time point and from animals sacrificed moribund up to that time point. USC-087 treatment nearly completely prevented liver damage by Ad6 when administration started up to 2 days post challenge (Fig. 4C). The treatment was partially effective when started at 3 or 4 days after infection (Fig. 4C).

Virus burden in the liver

At 7 days post challenge, liver samples were collected at necropsy and were analyzed for infectious virus burden. Vehicle-treated, Ad6-infected animals had very high virus burden in the liver (Fig. 4D). Remarkably, USC-087 treatment of the Ad6-infected animals inhibited virus replication even when administered 4 days post challenge (Fig. 4D).

At the 10 mg/kg dose, USC-087 is slightly toxic

We have observed that uninfected, USC-087-treated hamsters gained weight at a slower pace than their untreated counterparts (Fig. 4E). Further, upon gross necropsy, we observed that the kidneys of USC-087-treated hamsters were paler and enlarged compared to vehicle-treated ones, irrespective of whether the animals was infected with HAdV or not. Histopathological evaluation of the kidneys revealed minimal to mild degree of tubular degeneration.

DISCUSSION

HAdV infections can cause multi-organ disease in immunocompromised patients. The high mortality rate of the disease in this patient population makes it imperative to develop efficacious, antiviral drugs to fight HAdV infections. Here we demonstrated that oral administration of USC-087, an N-alkyl tyrosinamide phosphonate-ester of HPMPA, is a potent inhibitor of HAdV infections and is effective against i.v. challenge with Ad5 or Ad6 in the immunosuppressed Syrian hamster model. These two species C Ads are frequently found in transplant patients with disseminated HAdV infections (Lion, 2014). The compound reduced virus burden and pathology in the liver, the main target for HAdV replication in the hamster model. As a result, mortality was prevented completely or reduced significantly for USC-087-treated hamsters, even when the administration of the compound started at 4 days after virus challenge. It is known that a significant amount of progeny virus can be isolated from the liver of infected animals by that time (Fig. 4), suggesting that USC-087 treatment can be successful in patients with ongoing HAdV infection and showing that USC-087 is one of the very few compounds exhibiting good efficacy against HAdVs.

A number of compounds and agents have been reported to have anti-HAdV activity in cell culture (reviewed in (Wold and Ison, 2013)). Ribavirin is a nucleoside analog of guanosine that is active against Species C Ads in culture (Morfin et al., 2005), but its efficacy is controversial and it is not recommended for clinical use (Lion, 2014). Ribavirin is ineffective against Ad5 in the immunosuppressed Syrian hamster model (Tollefson et al., 2014). Ganciclovir, an analog of 2-deoxyguanosine, has been employed occasionally, with uncertain success, in the clinic (Ison, 2006; Lenaerts et al., 2008; Lindemans et al., 2010; Matthes-Martin et al., 2013; Sandkovsky et al., 2014; Wold and Ison, 2013). Ganciclovir is active against many herpes viruses (Field and Vere Hodge, 2013); after entering cells, it is phosphorylated by a viral-coded thymidine kinase or UL97 protein kinase, then is converted to the triphosphate form (Prichard and Kern, 2011). However, HAdV does not encode a kinase that is known to phosphorylate the drug, and phosphorylated GCV was not detected in Ad5-infected cells (Ying et al., 2014a). Nevertheless, the human mitochondrial deoxyguanosine kinase does phosphorylate it to a limited extent and it is possible that a homologous enzyme in the hamster might also exhibit similar activity (Sjoberg et al., 1998). Regardless, ganciclovir (Ying et al., 2014a) as well as valganciclovir (Toth et al., 2015) had good activity against Ad5 in the immunosuppressed Syrian hamster model. These compounds inhibit Ad5 DNA replication, possibly by inhibiting the Ad5 DNA polymerase (Ying et al., 2014a; Ying et al., 2015).

Very recently, a number of other compounds and agents have been shown to have anti-HAdV activity in cell culture. These include cardiotonic steroids (Grosso et al., 2017), 3-hydroxy-quinazoline-2,4(1H,3H)-diones (Kang et al., 2016), phenols in black tea extract (Karimi et al., 2016), dioscin, a compound extracted from air potato (Liu et al., 2013), 6-azacytidine (Alexeeva et al., 2015), and pyrrole and pyrrolopyrimidine compounds (Hamdy and El-Senousy, 2013; Mohamed et al., 2015).

Another promising approach for treating HAdV infections is anti-HAdV adoptive T-cell therapy. For the immunocompromised patients, the loss of HAdV-specific CD4 and CD8 T cells is a critical factor to sensitivity to opportunistic viral infections (Lion, 2014). To remedy this, researchers attempted to adoptively transfer virus specific T cells into T-cell-depleted patients. Because Ad-specific T cells are present in the peripheral blood of healthy adults only at low frequencies, researchers developed processes to enrich Ad-specific T cells (Feucht et al., 2015; Khanna and Smith, 2013; O’Reilly et al., 2016). Therapies based on RNA interference are also under development. While these methods are in the early phase of research, the results are encouraging (Kneidinger et al., 2012; Pozzuto et al., 2015; Schaar et al., 2016).

As opposed to large DNA viruses like herpesviruses and poxviruses, HAdVs have only two virus encoded enzymes, the DNA polymerase and the protease. Besides approaches that target the host (Hutterer et al., 2015), these two viral proteins are the only obvious targets of inhibitors. Thus, it is clear that generating efficacious anti-adenoviral small molecule compounds is a difficult task. We believe that USC-087, only the third compound to show oral efficacy in vivo against HAdV infection in the hamster model, is a very promising lead that can be the basis of further development.

Supplementary Material

Adenovirus infections of immunocompromised patients can cause serious multi-organ disease

The immunosuppressed Syrian hamster is an adequate animal model to test the efficacy of antiadenoviral drugs in vivo

USC-087, a novel antiviral drug, is efficacious in suppressing HAdV replication and pathogenesis in hamsters

Acknowledgments

This project was funded in part with Federal funds from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, under Contract Nos. HHSB272201000021I, HHSN272201100022I, HHSN272201100016I and Grant No. R44AI100401, and by the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences. The authors thank Dawn Schwartz for assistance.

Footnotes

Supplementary data (Appendix A)

USC-087 preliminary analysis (NMR and LC/MS spectra); flash chromatography purification details; NMR and MS spectra, combustion analysis data for purified sample; body weight changes.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alexeeva I, Nosach L, Palchykovska L, Usenko L, Povnitsa O. Synthesis and Comparative Study of Anti-Adenoviral Activity of 6-Azacytidine and Its Analogues. Nucleosides, Nucleotides & Nucleic Acids. 2015;34:565–578. doi: 10.1080/15257770.2015.1034363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berk AJ. Adenoviridae. In: Knipe DM, Howley PM, editors. Fields Virology. Lippincott williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia, PA: 2013. pp. 1704–1731. [Google Scholar]

- Choudhry A, Mathena J, Albano JD, Yacovone M, Collins L. Safety evaluation of adenovirus type 4 and type 7 vaccine live, oral in military recruits. Vaccine. 2016;34:4558–4564. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciesla SL, Trahan J, Wan WB, Beadle JR, Aldern KA, Painter GR, Hostetler KY. Esterification of cidofovir with alkoxyalkanols increases oral bioavailability and diminishes drug accumulation in kidney. Antiviral Res. 2003;59:163–171. doi: 10.1016/s0166-3542(03)00110-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cundy KC. Clinical pharmacokinetics of the antiviral nucleotide analogues cidofovir and adefovir. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1999;36:127–143. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199936020-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feucht J, Opherk K, Lang P, Kayser S, Hartl L, Bethge W, Matthes-Martin S, Bader P, Albert MH, Maecker-Kolhoff B, Greil J, Einsele H, Schlegel PG, Schuster FR, Kremens B, Rossig C, Gruhn B, Handgretinger R, Feuchtinger T. Adoptive T-cell therapy with hexon-specific Th1 cells as a treatment of refractory adenovirus infection after HSCT. Blood. 2015;125:1986–1994. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-06-573725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field HJ, Vere Hodge RA. Recent developments in anti-herpesvirus drugs. Br Med Bull. 2013;106:213–249. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldt011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florescu DF, Keck MA. Development of CMX001 (Brincidofovir) for the treatment of serious diseases or conditions caused by dsDNA viruses. Expert Review of Anti-Infective Therapy. 2014;12:1171–1178. doi: 10.1586/14787210.2014.948847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimley MS, Chemaly RF, Englund JA, Kurtzberg J, Chittick G, Brundage TM, Bae A, Morrison ME, Prasad VK. Brincidofovir for asymptomatic adenovirus viremia in pediatric and adult allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant recipients: A randomized placebo-controlled Phase II trial. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2017;23:512–521. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2016.12.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosso F, Stoilov P, Lingwood C, Brown M, Cochrane A. Suppression of Adenovirus Replication by Cardiotonic Steroids. J Virol. 2017:91. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01623-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu L, Qu J, Sun B, Yu X, Li H, Cao B. Sustained viremia and high viral load in respiratory tract secretions are predictors for death in immunocompetent adults with adenovirus pneumonia. PloS One. 2016;11:e0160777. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0160777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamdy NA, El-Senousy WM. Synthesis and antiviral evalution of some novel pyrazoles and pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyridazines bearing 5,6,7,8-tetrahydronaphthalene. Acta Pol Pharm. 2013;70:99–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartline CB, Gustin KM, Wan WB, Ciesla SL, Beadle JR, Hostetler KY, Kern ER. Ether lipid-ester prodrugs of acyclic nucleoside phosphonates: activity against adenovirus replication in vitro. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:396–399. doi: 10.1086/426831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holy A. Phosphonomethoxyalkyl analogs of nucleotides. Curr Pharm Des. 2003;9:2567–2592. doi: 10.2174/1381612033453668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holy A, Rosenberg I. Stereospecific syntheses of 9-(S)-(3-hydroxy-2-phosphonylmethoxypropyl)adenine (HPMPA) Nucleic Acids Symp Ser. 1987a:33–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holy A, Rosenberg I. Synthesis of isomeric and enantiomeric O-phosphonylmethyl derivatives of 9-(2,3-dihydroxypropyl)adenine. Collection of Czechoslovak Chemical Communications. 1987b;52:2775–2809. [Google Scholar]

- Hostetler KY. Alkoxyalkyl prodrugs of acyclic nucleoside phosphonates enhance oral antiviral activity and reduce toxicity: current state of the art. Antiviral Res. 2009;82:A84–A98. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hostetler KY. Synthesis and early development of hexadecyloxypropylcidofovir: an oral antipoxvirus nucleoside phosphonate. Viruses. 2010;2:2213–2225. doi: 10.3390/v2102213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutterer C, Eickhoff J, Milbradt J, Korn K, Zeittrager I, Bahsi H, Wagner S, Zischinsky G, Wolf A, Degenhart C, Unger A, Baumann M, Klebl B, Marschall M. A novel CDK7 inhibitor of the Pyrazolotriazine class exerts broad-spectrum antiviral activity at nanomolar concentrations. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59:2062–2071. doi: 10.1128/AAC.04534-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ip W, Zhan H, Gilmour KC, Davies EG, Qasim W. 22q11.2 deletion syndrome with life-threatening adenovirus infection. J Pediatr. 2013;163:908–910. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.03.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ison MG. Adenovirus infections in transplant recipients. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:331–339. doi: 10.1086/505498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ison MG, Hayden RT. Adenovirus. In: Hayden RT, Wolk D, Carroll K, Tang Y, editors. Diagnostic Microbiology of the Immunocompromised Host. 2. ASM Press; Washington, DC: 2016. pp. 217–232. [Google Scholar]

- Jhanji V, Chan TC, Li EY, Agarwal K, Vajpayee RB. Adenoviral keratoconjunctivitis. Surv Ophthalmol. 2015;60:435–443. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2015.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang D, Zhang H, Zhou Z, Huang B, Naesens L, Zhan P, Liu X. First discovery of novel 3-hydroxy-quinazoline-2,4(1H,3H)-diones as specific anti-vaccinia and adenovirus agents via ‘privileged scaffold’ refining approach. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2016;26:5182–5186. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2016.09.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karimi A, Moradi MT, Alidadi S, Hashemi L. Anti-adenovirus activity, antioxidant potential, and phenolic content of black tea (Camellia sinensis Kuntze) extract. J Complement Integr Med. 2016;13:357–363. doi: 10.1515/jcim-2016-0050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanna R, Smith C. Cellular immune therapy for viral infections in transplant patients. Indian J Med Res. 2013;138:796–807. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SJ, Kim K, Park SB, Hong DJ, Jhun BW. Outcomes of early administration of cidofovir in non-immunocompromised patients with severe adenovirus pneumonia. PloS One. 2015;10:e0122642. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0122642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kneidinger D, Ibrisimovic M, Lion T, Klein R. Inhibition of adenovirus multiplication by short interfering RNAs directly or indirectly targeting the viral DNA replication machinery. Antiviral Res. 2012;94:195–207. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2012.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalezari JP, Stagg RJ, Kuppermann BD, Holland GN, Kramer F, Ives DV, Youle M, Robinson MR, Drew WL, Jaffe HS. Intravenous cidofovir for peripheral cytomegalovirus retinitis in patients with AIDS. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126:257–263. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-126-4-199702150-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanier R, Trost L, Tippin T, Lampert B, Robertson A, Foster S, Rose M, Painter W, O’Mahony R, Almond M, Painter G. Development of CMX001 for the treatment of poxvirus infections. Viruses. 2010;2:2740–2762. doi: 10.3390/v2122740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M, Kim S, Kwon OJ, Kim JH, Jeong I, Son JW, Na MJ, Yoon YS, Park HW, Kwon SJ. Treatment of adenoviral acute respiratory distress syndrome using cidofovir with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. J Intensive Care Med. 2017;32:231–238. doi: 10.1177/0885066616681272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenaerts L, De Clercq E, Naesens L. Clinical features and treatment of adenovirus infections. RevMedVirol. 2008;18:357–374. doi: 10.1002/rmv.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindemans CA, Leen AM, Boelens JJ. How I treat adenovirus in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. Blood. 2010;116:5476–5485. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-259291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lion T. Adenovirus infections in immunocompetent and immunocompromised patients. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2014;27:441–462. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00116-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lion T, Kosulin K, Landlinger C, Rauch M, Preuner S, Jugovic D, Potschger U, Lawitschka A, Peters C, Fritsch G, Matthes-Martin S. Monitoring of adenovirus load in stool by real-time PCR permits early detection of impending invasive infection in patients after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Leukemia. 2010;24:706–714. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C, Wang Y, Wu C, Pei R, Song J, Chen S, Chen X. Dioscin’s antiviral effect in vitro. Virus Res. 2013;172:9–14. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Aguado P, Serna-Gallego A, Marrugal-Lorenzo JA, Gomez-Marin I, Sanchez-Cespedes J. Antiadenovirus drug discovery: potential targets and evaluation methodologies. Drug Discovery Today. 2015;20:1235–1242. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2015.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthes-Martin S, Boztug H, Lion T. Diagnosis and treatment of adenovirus infection in immunocompromised patients. Expert Review of Anti-Infective Therapy. 2013;11:1017–1028. doi: 10.1586/14787210.2013.836964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna CE, Kashemirov BA, Krylov IS, Zakharova VM. Method to improve antiviral activity of nucleotide analogue drugs. 9,550,803 B2. US Patent. 2017 Jan 24;

- Mohamed MS, Abd El-Hameed RH, Sayed AI, Soror SH. Novel antiviral compounds against gastroenteric viral infections. Arch Pharm (Weinheim) 2015;348:194–205. doi: 10.1002/ardp.201400387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morfin F, Dupuis-Girod S, Mundweiler S, Falcon D, Carrington D, Sedlacek P, Bierings M, Cetkovsky P, Kroes AC, van Tol MJ, Thouvenot D. In vitro susceptibility of adenovirus to antiviral drugs is species-dependent. AntivirTher. 2005;10:225–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly RJ, Prockop S, Hasan AN, Koehne G, Doubrovina E. Virus-specific T-cell banks for ‘off the shelf’ adoptive therapy of refractory infections. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2016;51:1163–1172. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2016.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paolino K, Sande J, Perez E, Loechelt B, Jantausch B, Painter W, Anderson M, Tippin T, Lanier ER, Fry T, DeBiasi RL. Eradication of disseminated adenovirus infection in a pediatric hematopoietic stem cell transplantation recipient using the novel antiviral agent CMX001. J Clin Virol. 2011;50:167–170. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2010.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JY, Kim BJ, Lee EJ, Park KS, Park HS, Jung SS, Kim JO. Clinical features and courses of adenovirus pneumonia in healthy young adults during an outbreak among korean military personnel. PloS One. 2017;12:e0170592. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0170592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pozzuto T, Roger C, Kurreck J, Fechner H. Enhanced suppression of adenovirus replication by triple combination of anti-adenoviral siRNAs, soluble adenovirus receptor trap sCAR-Fc and cidofovir. Antiviral Res. 2015;120:72–78. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2015.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prichard MN, Kern ER. The search for new therapies for human cytomegalovirus infections. Virus Res. 2011;157:212–221. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2010.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prichard MN, Williams JD, Komazin-Meredith G, Khan AR, Price NB, Jefferson GM, Harden EA, Hartline CB, Peet NP, Bowlin TL. Synthesis and antiviral activities of methylenecyclopropane analogs with 6-alkoxy and 6-alkylthio substitutions that exhibit broad-spectrum antiviral activity against human herpesviruses. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:3518–3527. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00429-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandkovsky U, Vargas L, Florescu DF. Adenovirus: current epidemiology and emerging approaches to prevention and treatment. Current Infectious Disease Reports. 2014;16:416. doi: 10.1007/s11908-014-0416-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaar K, Roger C, Pozzuto T, Kurreck J, Pinkert S, Fechner H. Biological antivirals for treatment of adenovirus infections. Antiviral Therapy. 2016;21:559–566. doi: 10.3851/IMP3047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjoberg AH, Wang L, Eriksson S. Substrate specificity of human recombinant mitochondrial deoxyguanosine kinase with cytostatic and antiviral purine and pyrimidine analogs. Mol Pharmacol. 1998;53:270–273. doi: 10.1124/mol.53.2.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan D, Zhu H, Fu Y, Tong F, Yao D, Walline J, Xu J, Yu X. Severe community-acquired pneumonia caused by human adenovirus in immunocompetent adults: A multicenter case series. PloS One. 2016;11:e0151199. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0151199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tollefson AE, Kuppuswamy M, Shashkova EV, Doronin K, Wold WS. Preparation and titration of CsCl-banded adenovirus stocks. Methods in Molecular Medicine. 2007;130:223–235. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-166-5:223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tollefson AE, Spencer JF, Ying B, Buller RM, Wold WS, Toth K. Cidofovir and brincidofovir reduce the pathology caused by systemic infection with human type 5 adenovirus in immunosuppressed Syrian hamsters, while ribavirin is largely ineffective in this model. Antiviral Res. 2014;112:38–46. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2014.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tollefson AE, Ying B, Spencer JF, Sagartz JE, Wold WSM, Toth K. Pathology in permissive Syrian hamsters after infection with species C human adenovirus (HAdV-C) is the result of virus replication: HAdV-C6 replicates more and causes more pathology than HAdV-C5. J Virol. 2017:91. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00284-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toth K, Spencer JF, Dhar D, Sagartz JE, Buller RM, Painter GR, Wold WSM. Hexadecyloxypropyl-cidofovir, CMX001, prevents adenovirus-induced mortality in a permissive, immunosuppressed animal model. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:7293–7297. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800200105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toth K, Ying B, Tollefson AE, Spencer JF, Balakrishnan L, Sagartz JE, Buller RM, Wold WS. Valganciclovir inhibits human adenovirus replication and pathology in permissive immunosuppressed female and male Syrian hamsters. Viruses. 2015;7:1409–1428. doi: 10.3390/v7031409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wold WS, Toth K. Syrian hamster as an animal model to study oncolytic adenoviruses and to evaluate the efficacy of antiviral compounds. Adv Cancer Res. 2012;115:69–92. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-398342-8.00003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wold WSM, Ison MG. Adenoviruses. In: Knipe DM, Howley PM, editors. Fields Virology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia, PA: 2013. pp. 1732–1767. [Google Scholar]

- Ying B, Spencer JF, Tollefson AE, Wold WSM, Toth K. Male Syrian hamsters are more susceptible to intravenous infection with species C human adenoviruses than are females. Virology. 2018;514:66–78. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2017.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ying B, Tollefson AE, Spencer JF, Balakrishnan L, Dewhurst S, Capella C, Buller RM, Toth K, Wold WS. Ganciclovir inhibits human adenovirus replication and pathogenicity in permissive immunosuppressed Syrian hamsters. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014a;58:7171–7181. doi: 10.1128/AAC.03860-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ying B, Toth K, Spencer JF, Aurora R, Wold WSM. Transcriptome sequencing and development of an expression microarray platform for liver infection in adenovirus type 5-infected Syrian golden hamsters. Virology. 2015;485:305–312. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2015.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.