Abstract

Disruption of circadian rhythms is commonly reported in individuals with Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Neurons in the primary circadian pacemaker, the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), exhibit daily rhythms in spontaneous neuronal activity which are important for maintaining circadian behavioral rhythms. Disruption of SCN neuronal activity has been reported in animal models of other neurodegenerative disorders; however, the effect of AD on SCN neurophysiology remains unknown. In this study we examined circadian behavioral and electrophysiological changes in a mouse model of AD, using male mice from the Tg-SwDI line which expresses human amyloid precursor protein with the familial Swedish (K670N/M671L), Dutch (E693Q), Iowa (D694N) mutations. The free-running period of wheel-running behavior was significantly shorter in Tg-SwDI mice compared to wild-type (WT) controls at all ages examined (3, 6, and 10 months). At the SCN level, the day/night difference in spike rate was significantly dampened in 6–8 month-old Tg-SwDI mice, with decreased AP firing during the day and an increase in neuronal activity at night. The dampening of SCN excitability rhythms in Tg-SwDI mice was not associated with changes in input resistance, resting membrane potential, or action potential afterhyperpolarization amplitude; however, SCN neurons from Tg-SwDI mice had significantly reduced A-type potassium current (IA) during the day compared to WT cells. Taken together, these results provide the first evidence of SCN neurophysiological disruption in a mouse model of AD, and highlight IA as a potential target for AD treatment strategies in the future.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, suprachiasmatic nucleus, circadian rhythms, A-type potassium current, electrophysiology

INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative form of dementia associated with elevated levels of the amyloid β (Aβ) peptide and the formation of pathological Aβ plaques and neurofibrillary tangles (Selkoe, 1999). The level of circulating Aβ, which is also found in the cerebrospinal fluid of (CSF) of healthy individuals, is tightly coupled to sleep/wake cycles and is molecular clock-dependent (Kress et al., 2018), with Aβ levels increasing throughout the activity phase of humans and rodents (Kang et al., 2009). Furthermore, prolonged sleep deprivation has been found to potentiate Aβ plaque formation in multiple mouse models of AD (Kang et al., 2009; Roh et al., 2012). Patients with AD often exhibit “sundowning syndrome,” a constellation of symptoms including late afternoon/evening delirium, hyperactivity, restlessness, confusion, and aggression, along with misaligned core body temperature and activity rhythms (Volicer et al., 2001; Khachiyants et al., 2011). These symptoms suggest a dysregulated circadian network, which regulates sleep/wake timing and allows anticipation of and preparation for daily recurring environmental events. Indeed, circadian rhythm disruption has been demonstrated in numerous mouse models of AD (Sterniczuk et al., 2010; Stranahan, 2012; Coogan et al., 2013; Oyegbami et al., 2017).

In mammals, the primary circadian pacemaker is located in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) of the hypothalamus. SCN neurons exhibit daily rhythms in spontaneous action potential (AP) firing which are critical for robust and consolidated circadian behavior (Schwartz et al., 1987). Loss or dampening of SCN neuronal activity rhythms has been described in animal models of other neurodegenerative disorders (Kudo et al., 2011a; Kudo et al., 2011b) and aging (Nakamura et al., 2011; Farajnia et al., 2012); however, changes in SCN neurophysiology in AD models have not yet been examined. Therefore, in the present study, we sought to determine whether changes in SCN neuronal excitability are associated with circadian behavioral disruption in a mouse model of AD and to identify the ionic mechanism driving these neurophysiological changes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Male mice expressing the human amyloid precursor protein with the familial Swedish (K670N/M671L), Dutch (E693Q), Iowa (D694N) homozygous mutations (Tg-SwDI; (Davis et al., 2004); commercially available from Mutant Mouse Research and Resource Center JAX or MMRRC; Stock #034843), congenic on a C57-BL6/J background were bred within the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) animal colony and compared to age-matched C57-BL6/J wild-type (WT) mice (generated within the colony or purchased from Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME) for all experiments. Female mice were not used to avoid the potential effect of estrous on circadian behavior (Leise and Harrington, 2011) and A-type potassium current (IA; (Pielecka-Fortuna et al., 2011)). Animals were housed in a 12:12 light/dark cycle (LD) or constant dark (DD) with food and water ad libitum in accordance with UAB IACUC guidelines and the National Institutes of Health guide for the care and use of Laboratory animals (NIH Publications No. 8023, revised 1978). All animals were euthanized with cervical dislocation and rapid decapitation. For loose-patch experiments, mice were individually housed in cages with running wheels for at least three weeks in DD and sacrificed and enucleated in the dark with the aid of night-vision goggles at circadian time (CT; where CT 12 is defined as the onset of activity) 4 or 16. For whole-cell recordings, mice were group-housed in LD and sacrificed between zeitgeiber time (ZT; where ZT 0 equals time of lights-on) 1–2 for day recordings or 11–12 for night recordings.

Behavior

Mice were individually housed with running wheels starting at 3 months or 6 months of age. The same animals were used for the 6 and 10 month old behavioral measurements, and the animals were re-entrained to LD for at least 1 month prior to beginning behavioral measurements at 10 months of age. Wheel-running activity was recorded and analyzed using ClockLab software (Actimetrics, Wilmette, IL) as described previously (Paul et al., 2012). Behavior was analyzed across 10 days of activity after the mice had been in DD for 7–10 days. The free-running period was determined by chi-squared periodogram analysis. Activity onset was fit by eye and activity offset was defined as the last point at which the activity in three of the previous six bins exceeded the mean activity level.

Electrophysiology

Fresh, coronal brain slices containing the SCN were prepared from Tg-SwDI and WT mice (6–8 months) using previously published methods (as in (Paul et al., 2012)). Loose-patch recordings were performed between CT 6–8 or CT 18–20. All whole-cell recordings were performed from ZT 4–8 or ZT 14–18. Resting membrane potential and input resistance were measured in current clamp mode (as in (Paul et al., 2016)). Persistent sodium current (INaP) was measured using a slow depolarizing voltage ramp (−100mV to +10mV, 59mV/s) and analyzed using previously described methods (as in (Paul et al., 2016)). A-type potassium current (IA) was measured in the presence of TEA (1 mM, in place of 1 mM NaCl), bicuculline (20 µM), tetrodotoxin (0.5 µM) and CdCl2 (25 µM) using progressive depolarizing voltage steps from −40 mV to 40 mV (at 5 mV steps) from a holding potential of −90 mV and again from a holding potential of −30 mV (to inactivate IA). IA was isolated by subtracting the cell response to the second step protocol from that of the first step protocol using offline subtraction. IA recordings were limited to cells in the dorsomedial SCN which have been previously shown to exhibit circadian changes in IA (Itri et al., 2010).

Data analysis and availability. All statistics were calculated using SPSS 22 software. Data were analyzed with independent samples t-tests, two-way ANOVAs and mixed-design two-way ANOVAs. In the event that assumptions of normality and homogenous variances were not met, a nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test was used instead. Significance was ascribed at p < 0.05. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

RESULTS

Circadian behavior is altered in Tg-SwDI as early as 3-months of age

To determine whether circadian behavior was disrupted in Tg-SwDI, as well as examine behavioral changes across disease progression, we monitored wheel-running behavior of Tg-SwDI and WT mice at 3, 6 and 10 months of age. In LD, both Tg-SwDI and WT mice demonstrated clear entrainment to the light cycle at all ages (Fig. 1A), with the majority of activity taking place during the dark phase (Table 1). At 3 months, Tg-SwDI mice exhibited significantly higher activity compared to WT mice while in LD (independent samples t-test, t11 = 3.086, p < 0.01; Table 1), but this difference was lost when the animals were placed in DD (Fig.1C; Table 2). At 10 months, the same increase in activity was seen in Tg-SwDI in LD (two-way mixed design ANOVA, significant genotype X age interaction, Table 3; Fisher’s LSD post-hoc, p < 0.05) and in DD (p < 0.005; Table 3, Fig. 1C). There were no other significant differences found between genotypes in LD behavior (Table 1).

Figure 1. Period of circadian behavioral rhythms is shortened in Tg-SwDI mice at all examined ages.

(a) Representative double plotted actograms of wheel-running activity for WT (left) and Tg-SwDI mice (right) at 3, 6 and 10 months of age beginning in LD and then released into DD. (b-e) Quantification of behavioral rhythms in DD at each age. Bar graphs indicate means ± SEM of free-running period (b), average activity (c), interdaily variability of activity onset (d) and offset (e). Symbols denote significant difference between genotypes at one age (*p < 0.05) or significant main effect of genotype for 6 and 10 months animals (#p < 0.05 or ###p < 0.001. n = 6–7 mice per genotype, per age.

Table 1.

Summary of circadian behavioral parameters for Tg-SwDI mice in LD.

| WT | Tg-SwDI | |

|---|---|---|

| 3 months | n = 7 | n = 6 |

| Activity (rev/min) | 16.1 ± 1.3 | 21.6 ± 1.2 |

| Light Activity (rev/day) | 718 ± 157 | 1583 ± 962 |

| Dark Activity (rev/day) | 22510 ± 1908 | 29563 ± 1008 |

| Total Activity (rev/day) | 23227 ± 1896 | 31146 ± 1665 |

| % Lights on Activity (%) | 3.2 ± 0.7 | 4.6 ± 2.5 |

| Phase Angle (hr) | 0.10 ± 0.06 | 0.53 ± 0.03 |

| Activity Onset Error (hr) | 0.18 ± 0.05 | 0.18 ± 0.08 |

| Activity Offset Error (hr) | 0.9 ± 0.22 | 0.84 ± 0.12 |

| 6 months | n = 7 | n = 7 |

| Activity (rev/min) | 13.7 ± 1.2 | 11.2 ± 1.7 |

| Light Activity (rev/day) | 2401 ± 497 | 1536 ± 320 |

| Dark Activity (rev/day) | 17291 ± 1882 | 14654 ± 2340 |

| Total Activity (rev/day) | 19693 ± 1798 | 16191 ± 2492 |

| % Lights on Activity (%) | 13.2 ± 3.2 | 10.2 ± 2.2 |

| Phase Angle (hr) | 0.25 ± 0.19 | −0.11 ± 0.14 |

| Activity Onset Error (hr) | 0.37 ± 0.09 | 0.33 ± 0.09 |

| Activity Offset Error (hr) | 1.02 ± 0.22 | 1.09 ± 0.34 |

| 10 months | n = 7 | n = 7 |

| Activity (rev/min) | 8.2 ± 1.4 | 13.9 ± 1.5 |

| Light Activity (rev/day) | 1058 ± 381 | 793 ± 216 |

| Dark Activity (rev/day) | 10757 ± 1924 | 19184 ± 2221 |

| Total Activity (rev/day) | 11815 ± 2050 | 19976 ± 2149 |

| % Lights on Activity (%) | 11.1 ± 3.9 | 4.5 ± 1.3 |

| Phase Angle (hr) | 0.81 ± 0.39 | 0.09 ± 0.11 |

| Activity Onset Error (hr) | 0.48 ± 0.11 | 0.16 ± 0.11 |

| Activity Offset Error (hr) | 1.4 ± 0.34 | 1.41 ± 0.28 |

Table 2.

Summary of circadian behavioral parameters for Tg-SwDI mice in DD.

| WT | Tg-SwDI | |

|---|---|---|

| 3 months | n = 7 | n = 6 |

| Tau (h) | 23.84 ± 0.03 | 23.68 ± 0.07 |

| Power | 1457 ± 120 | 1430 ± 135 |

| Activity (rev/min) | 17.4 ± 2.2 | 21.5 ± 3.0 |

| Alpha length (h) | 11.9 ± 1.1 | 14.3 ± 1.2 |

| Fragmentation (bouts/day) | 3.0 ± 0.4 | 3.6 ± 0.4 |

| Avg. bout length (min) | 230.8 ± 35.5 | 182.6 ± 25.6 |

| 6 months | n = 7 | n = 7 |

| Tau (h) | 23.91 ± 0.04 | 23.54 ± 0.05 |

| Power | 1322 ± 127 | 1276 ± 110 |

| Activity (rev/min) | 12.1 ± 1.6 | 13.3 ± 1.9 |

| Alpha length (h) | 13.0 ± 0.6 | 13.0 ± 0.5 |

| Fragmentation (bouts/day) | 3.9 ± 0.4 | 4.5 ± 0.3 |

| Avg. bout length (min) | 146.1 ± 20.7 | 120.7 ± 14.2 |

| 10 months | n = 7 | n = 7 |

| Tau (h) | 23.89 ± 0.03 | 23.57 ± 0.06 |

| Power | 872 ± 83 | 1177 ± 145 |

| Activity (rev/min) | 7.2 ± 1.3 | 14.3 ± 1.3 |

| Alpha length (h) | 13.6 ± 0.2 | 13.8 ± 1.2 |

| Fragmentation (bouts/day) | 5.5 ± 0.4 | 4.4 ± 0.5 |

| Avg. bout length (min) | 74.7 ± 12 | 141.8 ± 20.1 |

Table 3.

Summary of ANOVA results for circadian behavioral parameters for 6 & 10 month old Tg-SwDI mice.

| Main effect genotype F (P) |

Main effect age F (P) |

Interaction F (P) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| LD | |||

| Activity | 0.62 (0.45) | 9.94 (0.008) | 80.73 (<0.001) |

| Light Activity | 1.62 (0.23) | 14.79 (0.002) | 1.22 (0.29) |

| Dark Activity | 0.99 (0.34) | 2.92 (0.11) | 88.90 (<0.001) |

| Total Activity | 0.62 (0.45) | 9.94 (0.008) | 80.75 (<0.001) |

| % Lights on Activity | 1.68 (0.22) | 6.08 (0.03) | 1.22 (0.29) |

| Phase Angle | 3.41 (0.09) | 5.47 (0.04) | 1.24 (0.29) |

| Activity Onset Error | 3.15 (0.10) | 0.10 (0.76) | 1.87 (0.20) |

| Activity Offset Error | 0.01 (0.92) | 2.63 (0.13) | 0.02 (0.89) |

| DD | |||

| Tau | 56.66 (<0.001) | 0.00 (1.00) | 0.39 (0.54) |

| Power | 0.91 (0.36) | 7.86 (0.02) | 3.22 (0.10) |

| Activity | 4.79 (0.05) | 3.37 (0.09) | 7.35 (0.02) |

| Alpha length | 0.01 (0.93) | 1.23 (0.39) | 0.03 (0.87) |

| Fragmentation | 0.46 (0.51) | 3.92 (0.07) | 5.70 (0.03) |

| Avg. bout length | 1.2 (0.29) | 2.77 (0.12) | 9.36 (0.01) |

| Activity Onset Error | 4.76 (0.05) | 2.43 (0.15) | 1.15 (0.31) |

| Activity Offset Error | 34.31 (<0.001) | 1.44 (0.25) | 0.19 (0.67) |

When placed in DD, several differences in circadian behavior were revealed (Fig. 1; Table 2). Most notably, the free-running period (FRP) of Tg-SwDI mice was significantly shorter than that of WT mice at all observed ages (3 mo.: independent samples t-test, t11 = 2.208, p < 0.05; 6 and 10 mo.: two-way mixed design ANOVA, main effect of genotype p < 0.001; Table 3; Fig. 1B). This difference was greatest at 6 months, when the FRP of Tg-SwDI activity was ~22 minutes shorter than in WT mice. Although the amplitude/strength of the behavioral rhythms did not differ between the two genotypes at any age as measured by the chi-squared periodogram power or number of activity bouts per day (Tables 2, 3), the organization of activity differed between the two genotypes. The interdaily variability of activity offset was significantly increased in Tg-SwDI mice across all ages (3 mo.: independent samples t-test, t11 = 2.331, p < 0.05; 6 and 10 mo.: main effect of genotype, p < 0.00110 mo., t9.7 = 4.179, p < 0.005; Fig. 1E), while there was decreased interdaily variability in the activity onset in Tg-SwDI 6 and 10 months of age (Fig. 1D; main effect of genotype, p = 0.05; Tables 2 and 3).

SCN neurophysiological rhythms are altered in Tg-SwDI

To examine whether SCN neuronal activity rhythms were also disrupted in a model of AD, we next conducted loose-patch electrophysiological recordings during the subjective day (CT 6–8) or subjective night (CT 18–20) in Tg-SwDI and WT mice that were housed in DD for at least 3 weeks. Both WT and Tg-SwDI neurons displayed the typical day/night differences in spontaneous firing rate (SFR), with higher activity during the day and lower activity at night (Fig. 2; two-way ANOVA, main effect of time, F1,216 = 99.325, p < 0.001). However the rhythm in SFR was dampened in Tg-SwDI mice (genotype×time interaction, F1,216 = 13.385, p < 0.001). This was especially prevalent during the subjective day, when Tg-SwDI neurons were firing at a rate nearly 2 Hz slower than WT neurons (p < 0.001).

Figure 2. Neuronal activity rhythm is impaired in Tg-SwDI SCN neurons.

(a) Means ± SEM spontaneous action potential frequencies of SCN neurons during the subject day and subjective night from WT and Tg-SwDI mice housed in DD. ***p < 0.001; n = 45–76 cells, 2–3 slices per group. (b) Representative cell-attached loose-patch traces (5 s) from each group in (a).

We next sought to examine altered membrane properties in Tg-SwDI neurons that could explain this change in SCN neuronal activity. To do this, we conducted whole-cell current clamp recordings during the day (ZT 4–8) or night (ZT 14–18) in SCN neurons from Tg-SwDI and WT (Fig. 3). Surprisingly, Tg-SwDI neurons continued to show day/night differences in resting membrane potential (RMP; Fig. 3C) and input resistance (Rinput; Fig. 3D) similar to that seen in WT neurons (two-way ANOVA, main effect of time: RMP, F1,59 = 4.102, p < 0.05; Rinput, F1,59 = 19.186, p < 0.001; Fig. 3C,D) with day-night variation in SFR similar to that observed with loose patch (Fig. 2). Furthermore, the daily variation in the action potential after-hyperpolarization amplitude was present in both genotypes (two-way ANOVA, main effect of time, F1,49 = 10.091, p < 0.005; Fig. 3E), and there did not appear to be any other differences in the average action potential waveforms of each genotype (Fig. 3F).

Figure 3. Passive and active membrane properties of WT and Tg-SwDI neurons.

(a) Representative traces (5 s) of current clamp recordings from WT or Tg-SwDI neurons during the day or early-night. (b-d) Means ± SEM of spontaneous action potential frequency (b), resting membrane potential (c) and input resistance (d) of cells represented in (a). n = 11–21 cells, 3–4 slices per group. (e-f) Mean ± SEM of afterhyperpolarization amplitude (e) and average action potential waveforms (f) of the spontaneously active neurons from (a-d). n = 9–18 cells per group. Main effect of time, p < 0.05 for (c) and p < 0.005 for (d-e).

We have recently reported that the persistent sodium current (INaP), a major contributor to the excitatory drive in SCN neurons (Pennartz et al., 1997; Jackson et al., 2004; Kononenko et al., 2004), is rhythmic within the SCN, and this rhythm contributes to the daily change in SCN neuronal activity independent of changes in RMP (Paul et al., 2016). Therefore, we next sought to examine INaP in Tg-SwDI and WT neurons during the day and the night using a slow depolarizing voltage ramp (as in Paul, et al., 2015; Fig. 4). Consistent with our previous findings, peak INaP magnitude was increased during the day, when SCN cells are more active (two-way ANOVA, main effect of time, F1,84 = 5.246, p < 0.05), but, surprisingly, the magnitude of INaP in Tg-SwDI neurons was not different from that of WT cells at either time (Fig. 4A).

Figure 4. Persistent sodium current rhythm remains intact in Tg-SwDI neurons.

Means ± SEM of peak inward current (a) and averaged normalized response (b-c) to slow depolarizing voltage ramp (−100 to +10 mV; 59mV/s) from WT or Tg-SwDI cells during the day (b) or night (c). n = 16–29 cells, 3–4 slices per group. Main effect of time, p < 0.05 for (a).

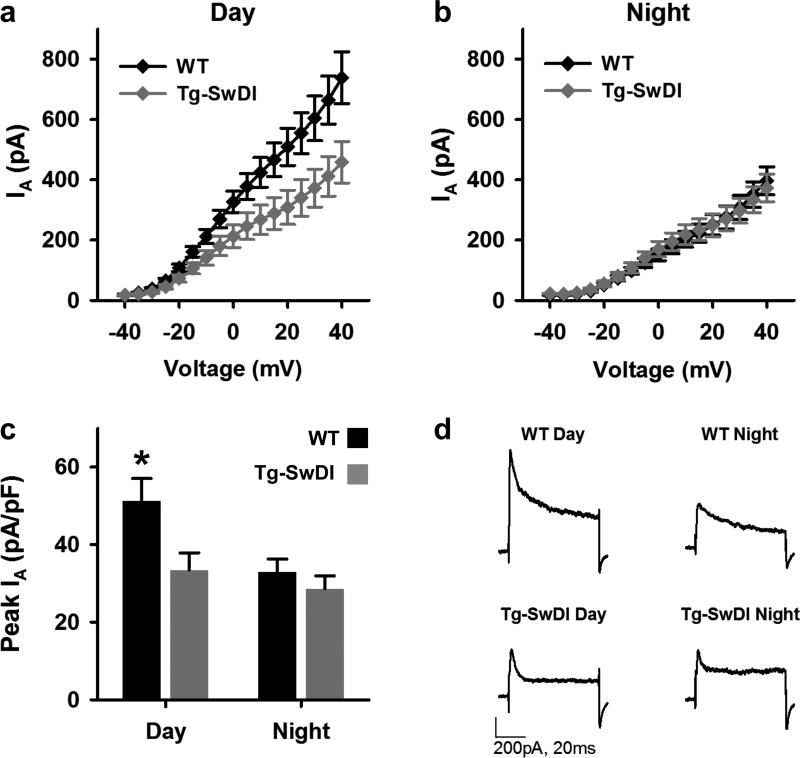

A-type potassium current (IA) is another current that exhibits a daily change in magnitude in SCN neurons and contributes to SCN excitability rhythms with greater current during the day (Itri et al., 2010; Farajnia et al., 2012). In SCN neurons and neocortical interneurons, IA allows continuous spontaneous firing without spike adaptation (Itri et al., 2010; Williams and Hablitz, 2015). Moreover, recent reports have shown reduced IA in hippocampal neurons from a different mouse model of AD and in neurons treated with Aβ42 (Hall et al., 2015; Scala et al., 2015). Thus, we next sought to determine whether IA is altered in SCN neurons of Tg-SwDI. To do this, we performed voltage-clamp recordings in SCN neurons from Tg-SwDI and WT mice during the day and night. To isolate IA, cells were exposed to two sets of progressive depolarizing voltage steps (see Methods) first from a holding potential of −90 mV and then from a holding potential of −30 mV to inactivate IA channels. The difference between the responses to these two stimuli was then used to determine the peak outward current at each step. As expected, the WT neurons had greater IA during the day than at night (Fig. 5A,D). This day/night difference was not seen in Tg-SwDI neurons (Fig. 5B,D). A comparison of IA at the highest step, normalized to cell capacitance, revealed that IA was significantly increased during the day in WT neurons (Kruskal-Wallis, H(3) = 19.025, p < 0.001; post hoc asymptotic significant, p < 0.005; Fig. 5C) but not in Tg-SwDI neurons (p = 0.627; Fig. 5C). In fact, during the day, normalized IA was significantly reduced in Tg-SwDI neurons compared to WT IA (p < 0.001).

Figure 5. Day/night difference in IA is lost in dorsal SCN of Tg-SwDI mice.

(a-b) I-V plots (mean ± SEM) of IA from WT (black) and Tg-SwDI (gray) neurons measured during the mid-day (a) or early night (b) using of progressive depolarizing voltage steps (−40mV to +40mV, 5mV steps) from a holding potential of first −90mV and then −30mV. IA was isolated by subtracting the current response to the second protocol from the response to the first protocol. (c) Mean ± SEM of normalized peak IA (at +40mV) of cells in (a-b). **p < 0.005, n = 25–39 cells, 3–4 slices per group. (d) Representative traces showing the subtracted current response to +40mV voltage step from neurons in (a-c).

DISCUSSION

Circadian rhythm disruption is one of the most widely reported, non-cognitive symptoms found in Alzheimer’s disease, but the underlying cause of these circadian changes is still poorly understood. Similar circadian decline has also been associated with normal aging and aging-related disorders, such as Huntington’s and Parkinson’s diseases (Kudo et al., 2011a; Kudo et al., 2011b; Nakamura et al., 2011; Farajnia et al., 2012). Moreover, mouse models of these disorders have demonstrated that decline in the circadian system can be found in the SCN at the membrane level before changes in the molecular clock can be found (Kudo et al., 2011a; Kudo et al., 2011b; Nakamura et al., 2011). These reports have led to the proposal that the neurophysiological output of the SCN may be the “weak-link” of the circadian system in aging and aging-related disorders (Colwell, 2011). In the present study, we provide the first evidence that disruption of rhythmic SCN neuronal activity is also present in a mouse model of AD which exhibits altered circadian behavior. Additionally, we found suppressed daytime IA to be underlying these electrophysiological deficits.

Our first major finding was that Tg-SwDI mice exhibit a significantly shortened FRP as early as 3 months of age. This result is consistent with previous studies which also found shortened FRPs in other AD mouse models (triple transgenic and APP/PS1) early in the disease progression (Sterniczuk et al., 2010; Oyegbami et al., 2017). Together, these findings suggest that circadian changes have the potential to serve as an early warning for individuals in the early stages of AD. Measuring FRP in human patients can be difficult due to the need for constant conditions; however, chronotype could be used as an alternative measure since it has been shown to correlate with FRP (Duffy et al., 2001).

Although many studies have reported circadian behavioral deficits in various mouse models of AD, evidence that this decline occurs at the level of the master circadian pacemaker, the SCN, has been limited. In fact, no evidence of Aβ plaque formation in the SCN has been reported (van de Nes et al., 1998; Stopa et al., 1999; Gorman and Yellon, 2010), consistent with our unpublished observations. Given the numerous reports of physiological changes occurring other brain areas of AD mice prior to plaque formation or neuronal degeneration (Hsia et al., 1999; Jacobsen et al., 2006; Tomiyama et al., 2010), we hypothesized that alterations in membrane excitability in SCN neurons could explain changes in behavioral rhythms in the absence of gross pathology. Our finding that SCN neuronal excitability rhythms are altered in AD provides novel evidence that the circadian system is can be directly impacted in Tg-SwDI as young as 6 months of age. Considering the proximity of the SCN to the third ventricle, and thus access to elevated Aβ circulating in the CSF (Reiter et al., 2014), it is possible that circulating Aβ in the CSF can directly act on SCN neurons. Numerous reports have shown that circadian behavior degrades in the process of normal aging (Valentinuzzi et al., 1997; Dijk and Duffy, 1999). Likewise, the electrophysiological output of the SCN declines with aging (Nakamura et al., 2011; Farajnia et al., 2012). Thus, age can be a major confounding factor when studying the effect of neurodegenerative disorders on circadian rhythms because many animal models do not develop pathology until reaching an advanced age. To avoid this, we used selected the Tg-SwDI AD model because this model begins developing Aβ pathology and spatial learning deficits as early as 3 months (Xu et al., 2007).

The dampening of SCN rhythms in TgSwDI mice was predominantly driven by decreased neuronal activity during the day. Furthermore, our data show that reduction in IA during the day was underlying these changes in spontaneous SCN activity. Interestingly, decreased daytime neuronal excitability and A-type current have also been reported in SCN neurons of WT mice near the end of their lifespan (~2yr; (Farajnia et al., 2012)). Reduction of IA has also been reported in dentate granule cells from the J20 AD mouse model and in large ventrolateral neurons of sleep deprived flies overexpressing AβArctic (Hall et al., 2015; Tabuchi et al., 2015). However, in both of these cases decreased IA was associated with hyperexcitability in those cells, whereas IA appears to have the opposite effect in the SCN. Our finding that reduced IA has an inhibitory effect on neuronal activity is consistent with previous research in the SCN showing that pharmacological inhibition of IA with 4-AP during the day suppresses SCN spontaneous spiking, mimicking the phenotype of SCN activity in old mice as well as Tg-SwDI mice (Farajnia et al., 2012). In other brain regions, 4-AP in neorcortical fast-spiking basket cells improves spike accommodation, increasing the inter-spike interval during repetitive spiking (Williams and Hablitz, 2015). The inter-regional differences in the role of IA in the maintenance and rate of action potential firing and how it is altered in neurodegeneration are important areas of future research.

Although multiple studies have described the rhythm in IA in the SCN (Itri et al., 2010; Farajnia et al., 2012) and shown its importance for circadian behavior (Granados-Fuentes et al., 2015), the specific mechanism driving its rhythmicity has remained elusive. Importantly, multiple A-type channel sub-units (Kv4.1 and Kv4.2) did not show day/night rhythms in transcript expression or protein levels when examined at ZT 6 and ZT 14 (Itri et al., 2010). Interestingly, mice lacking expression of Kv4.2 sub-units exhibit shortened free running periods in circadian behavior similar to that found in Tg-SwDI mice (Granados-Fuentes et al., 2012). In other brain regions, phosphorylation of Kv4.2 at Ser-616 has been shown to regulate IA density (Hu et al., 2006; Scala et al., 2015). Moreover, recent work has demonstrated that Aβ42-induced suppression of IA in hippocampal neurons is associated with an increase in Kv4.2 phosphorylation at this site (Scala et al., 2015). Future work will be needed to determine if post-translational modifications of A-type potassium channels are responsible for regulating daily rhythms in IA in the SCN. Moreover, it is important to note that the present studies were conducted in male mice, and thus, future studies should determine whether sex impacts day-night differences in SCN physiology. This knowledge could provide insight into the causes of circadian decline in aging and aging-related disorders as well as provide a direction towards new treatment strategies to restore proper rhythmicity in various diseases.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants R01NS082413 (KLG) and F31NS086282.

References

- Colwell CS. Linking neural activity and molecular oscillations in the SCN. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2011;12:553–569. doi: 10.1038/nrn3086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coogan AN, Schutova B, Husung S, Furczyk K, Baune BT, Kropp P, Hassler F, Thome J. The circadian system in Alzheimer's disease: disturbances, mechanisms, and opportunities. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;74:333–339. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis J, Xu F, Deane R, Romanov G, Previti ML, Zeigler K, Zlokovic BV, Van Nostrand WE. Early-onset and robust cerebral microvascular accumulation of amyloid beta-protein in transgenic mice expressing low levels of a vasculotropic Dutch/Iowa mutant form of amyloid beta-protein precursor. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:20296–20306. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312946200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dijk DJ, Duffy JF. Circadian regulation of human sleep and age-related changes in its timing, consolidation and EEG characteristics. Ann Med. 1999;31:130–140. doi: 10.3109/07853899908998789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy JF, Rimmer DW, Czeisler CA. Association of intrinsic circadian period with morningness-eveningness, usual wake time, and circadian phase. Behav Neurosci. 2001;115:895–899. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.115.4.895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farajnia S, Michel S, Deboer T, vanderLeest HT, Houben T, Rohling JH, Ramkisoensing A, Yasenkov R, Meijer JH. Evidence for neuronal desynchrony in the aged suprachiasmatic nucleus clock. J Neurosci. 2012;32:5891–5899. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0469-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorman MR, Yellon S. Lifespan daily locomotor activity rhythms in a mouse model of amyloid-induced neuropathology. Chronobiol Int. 2010;27:1159–1177. doi: 10.3109/07420528.2010.485711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granados-Fuentes D, Norris AJ, Carrasquillo Y, Nerbonne JM, Herzog ED. I(A) channels encoded by Kv1.4 and Kv4.2 regulate neuronal firing in the suprachiasmatic nucleus and circadian rhythms in locomotor activity. J Neurosci. 2012;32:10045–10052. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0174-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granados-Fuentes D, Hermanstyne TO, Carrasquillo Y, Nerbonne JM, Herzog ED. IA Channels Encoded by Kv1.4 and Kv4.2 Regulate Circadian Period of PER2 Expression in the Suprachiasmatic Nucleus. J Biol Rhythms. 2015;30:396–407. doi: 10.1177/0748730415593377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall AM, Throesch BT, Buckingham SC, Markwardt SJ, Peng Y, Wang Q, Hoffman DA, Roberson ED. Tau-dependent Kv4.2 depletion and dendritic hyperexcitability in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci. 2015;35:6221–6230. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2552-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsia AY, Masliah E, McConlogue L, Yu GQ, Tatsuno G, Hu K, Kholodenko D, Malenka RC, Nicoll RA, Mucke L. Plaque-independent disruption of neural circuits in Alzheimer's disease mouse models. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:3228–3233. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.3228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu HJ, Carrasquillo Y, Karim F, Jung WE, Nerbonne JM, Schwarz TL, Gereau RWt. The kv4.2 potassium channel subunit is required for pain plasticity. Neuron. 2006;50:89–100. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itri JN, Vosko AM, Schroeder A, Dragich JM, Michel S, Colwell CS. Circadian regulation of a-type potassium currents in the suprachiasmatic nucleus. J Neurophysiol. 2010;103:632–640. doi: 10.1152/jn.00670.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson AC, Yao GL, Bean BP. Mechanism of spontaneous firing in dorsomedial suprachiasmatic nucleus neurons. J Neurosci. 2004;24:7985–7998. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2146-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen JS, Wu CC, Redwine JM, Comery TA, Arias R, Bowlby M, Martone R, Morrison JH, Pangalos MN, Reinhart PH, Bloom FE. Early-onset behavioral and synaptic deficits in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:5161–5166. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600948103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang JE, Lim MM, Bateman RJ, Lee JJ, Smyth LP, Cirrito JR, Fujiki N, Nishino S, Holtzman DM. Amyloid-beta dynamics are regulated by orexin and the sleep-wake cycle. Science. 2009;326:1005–1007. doi: 10.1126/science.1180962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khachiyants N, Trinkle D, Son SJ, Kim KY. Sundown syndrome in persons with dementia: an update. Psychiatry Investig. 2011;8:275–287. doi: 10.4306/pi.2011.8.4.275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kononenko NI, Shao LR, Dudek FE. Riluzole-sensitive slowly inactivating sodium current in rat suprachiasmatic nucleus neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2004;91:710–718. doi: 10.1152/jn.00770.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kress GJ, Liao F, Dimitry J, Cedeno MR, FitzGerald GA, Holtzman DM, Musiek ES. Regulation of amyloid-beta dynamics and pathology by the circadian clock. J Exp Med. 2018 doi: 10.1084/jem.20172347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudo T, Loh DH, Truong D, Wu Y, Colwell CS. Circadian dysfunction in a mouse model of Parkinson's disease. Exp Neurol. 2011a;232:66–75. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudo T, Schroeder A, Loh DH, Kuljis D, Jordan MC, Roos KP, Colwell CS. Dysfunctions in circadian behavior and physiology in mouse models of Huntington's disease. Exp Neurol. 2011b;228:80–90. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2010.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leise TL, Harrington ME. Wavelet-based time series analysis of circadian rhythms. J Biol Rhythms. 2011;26:454–463. doi: 10.1177/0748730411416330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura TJ, Nakamura W, Yamazaki S, Kudo T, Cutler T, Colwell CS, Block GD. Age-related decline in circadian output. J Neurosci. 2011;31:10201–10205. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0451-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyegbami O, Collins HM, Pardon MC, Ebling FJ, Heery DM, Moran PM. Abnormal clock gene expression and locomotor activity rhythms in two month-old female APPSwe/PS1dE9 mice. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2017 doi: 10.2174/1567205014666170317113159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul JR, Johnson RL, Jope RS, Gamble KL. Disruption of circadian rhythmicity and suprachiasmatic action potential frequency in a mouse model with constitutive activation of glycogen synthase kinase 3. Neuroscience. 2012;226:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.08.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul JR, DeWoskin D, McMeekin LJ, Cowell RM, Forger DB, Gamble KL. Regulation of persistent sodium currents by glycogen synthase kinase 3 encodes daily rhythms of neuronal excitability. Nat Commun. 2016;7:13470. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennartz CM, Bierlaagh MA, Geurtsen AM. Cellular mechanisms underlying spontaneous firing in rat suprachiasmatic nucleus: involvement of a slowly inactivating component of sodium current. J Neurophysiol. 1997;78:1811–1825. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.78.4.1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pielecka-Fortuna J, DeFazio RA, Moenter SM. Voltage-gated potassium currents are targets of diurnal changes in estradiol feedback regulation and kisspeptin action on gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons in mice. Biol Reprod. 2011;85:987–995. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.111.093492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiter RJ, Tan DX, Kim SJ, Cruz MH. Delivery of pineal melatonin to the brain and SCN: role of canaliculi, cerebrospinal fluid, tanycytes and Virchow-Robin perivascular spaces. Brain Struct Funct. 2014;219:1873–1887. doi: 10.1007/s00429-014-0719-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roh JH, Huang Y, Bero AW, Kasten T, Stewart FR, Bateman RJ, Holtzman DM. Disruption of the sleep-wake cycle and diurnal fluctuation of beta-amyloid in mice with Alzheimer's disease pathology. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4:150ra122. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scala F, Fusco S, Ripoli C, Piacentini R, Li Puma DD, Spinelli M, Laezza F, Grassi C, D'Ascenzo M. Intraneuronal Abeta accumulation induces hippocampal neuron hyperexcitability through A-type K(+) current inhibition mediated by activation of caspases and GSK-3. Neurobiol Aging. 2015;36:886–900. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.10.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz WJ, Gross RA, Morton MT. The suprachiasmatic nuclei contain a tetrodotoxin-resistant circadian pacemaker. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84:1694–1698. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.6.1694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selkoe DJ. Translating cell biology into therapeutic advances in Alzheimer's disease. Nature. 1999;399:A23–31. doi: 10.1038/399a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterniczuk R, Dyck RH, Laferla FM, Antle MC. Characterization of the 3xTg-AD mouse model of Alzheimer's disease: part 1. Circadian changes. Brain Res. 2010;1348:139–148. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stopa EG, Volicer L, Kuo-Leblanc V, Harper D, Lathi D, Tate B, Satlin A. Pathologic evaluation of the human suprachiasmatic nucleus in severe dementia. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1999;58:29–39. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199901000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stranahan AM. Chronobiological approaches to Alzheimer's disease. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2012;9:93–98. doi: 10.2174/156720512799015028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabuchi M, Lone SR, Liu S, Liu Q, Zhang J, Spira AP, Wu MN. Sleep interacts with abeta to modulate intrinsic neuronal excitability. Curr Biol. 2015;25:702–712. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomiyama T, Matsuyama S, Iso H, Umeda T, Takuma H, Ohnishi K, Ishibashi K, Teraoka R, Sakama N, Yamashita T, Nishitsuji K, Ito K, Shimada H, Lambert MP, Klein WL, Mori H. A mouse model of amyloid beta oligomers: their contribution to synaptic alteration, abnormal tau phosphorylation, glial activation, and neuronal loss in vivo. J Neurosci. 2010;30:4845–4856. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5825-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentinuzzi VS, Scarbrough K, Takahashi JS, Turek FW. Effects of aging on the circadian rhythm of wheel-running activity in C57BL/6 mice. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:R1957–1964. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1997.273.6.R1957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Nes JA, Kamphorst W, Ravid R, Swaab DF. Comparison of beta-protein/A4 deposits and Alz-50-stained cytoskeletal changes in the hypothalamus and adjoining areas of Alzheimer's disease patients: amorphic plaques and cytoskeletal changes occur independently. Acta Neuropathol. 1998;96:129–138. doi: 10.1007/s004010050872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volicer L, Harper DG, Manning BC, Goldstein R, Satlin A. Sundowning and circadian rhythms in Alzheimer's disease. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:704–711. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.5.704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams SB, Hablitz JJ. Differential modulation of repetitive firing and synchronous network activity in neocortical interneurons by inhibition of A-type K(+) channels and Ih. Front Cell Neurosci. 2015;9:89. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2015.00089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu F, Grande AM, Robinson JK, Previti ML, Vasek M, Davis J, Van Nostrand WE. Early-onset subicular microvascular amyloid and neuroinflammation correlate with behavioral deficits in vasculotropic mutant amyloid beta-protein precursor transgenic mice. Neuroscience. 2007;146:98–107. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.01.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]