Abstract

Androgen receptor (AR) signaling is vital to the viability of all forms of prostate cancer (PCa). With the goal of investigating the effect of simultaneous inhibition and depletion of AR on viability of PCa cells, we designed, synthesized and characterized the bioactivities of bifunctional agents which incorporate the independent cancer killing properties of an antiandrogen and genistein, and the AR downregulation effect of genistein within a single molecular template. We observed that a representative conjugate, 9b, is much more cytotoxic to both LNCaP and DU145 cells relative to the antiandrogen and genistein building blocks as single agents or their combination. Moreover, conjugate 9b more effectively down-regulates cellular AR protein levels relative to genistein and induces S phase cell cycle arrest. The promising bioactivities of these conjugates warrant further investigation.

Keywords: Prostate Cancer, Genistein, Androgen Receptor, Antiandrogen, LNCaP, DU145

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Among American men, prostate cancer (PCa) is the second most leading cause of cancer-related death and accounts for nearly 240,000 new cases each year.1, 2 Androgen receptor (AR) expression has been shown by numerous studies to be vital in PCa progression.3 However, AR is also involved in the normal function of the prostate and other tissues.4 In its unbound state, AR is a steroid hormone receptor found in the cytoplasm associated with heat shock proteins (HSP-90), cytoskeletal proteins, and other chaperones.5 After binding to one of its natural ligands (dihydrotestosterone (DHT) or testosterone), AR undergoes a conformational change which results in homodimerization, followed by nuclear translocation, DNA binding, and the transcription of AR regulated genes.6

For patients with advanced hormone-sensitive PCa, androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) is often employed as a complementary therapy, in the form of antiandrogens (Fig. 1A), to luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) agonists. While most patients respond well to ADT, many of these patients will become refractory to treatment and develop castration resistant PCa (CRPC).7 The importance of AR expression in CRPC progression is clear as AR expression is nearly 6-fold higher in CRPC compared to hormone-sensitive PCa.8 As such, second-line therapies such as enzalutamide and abiraterone are employed to treat CRPC by targeting AR regulation/signaling and androgen synthesis respectively.9–11

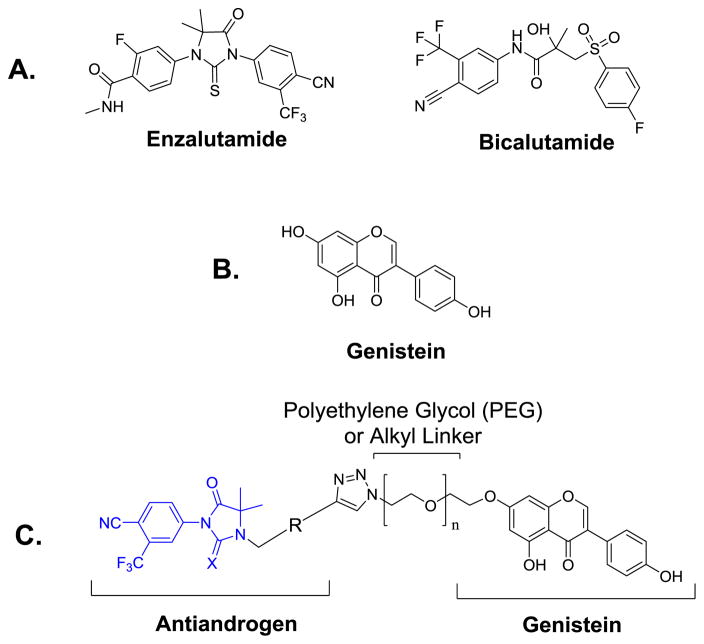

Figure 1.

(A) Structures of representative FDA approved antiandrogens, (B) Structure of genistein, (C) Design of thio/hydantoin-derived antiandrogen-genistein conjugates (X = O or S).

Genistein (Fig. 1B), a natural soy isoflavone, is among the most potent phytogestrogens to have shown beneficial antitumor activity.12 Genistein has the potential to become a powerful therapeutic against PCa due to many properties that work in concert to exhibit anti-proliferative activity in cancer cells.12 Several studies have shown that genistein elicits pleotropic effects, inhibiting and/or downregulating several cancer-relevant targets within the cell. Among the targets whose inhibition and/or downregulation has been implicated in the anti-proliferative activities of genistein include: tyrosine receptor kinases (TRKs), the TRK signal transduction pathway (TRK → Raf →MEK → ERK/p38), mitogen activated protein kinase signaling pathways (MAPKs)13, 14, NF-kB15, 16, Akt signaling16, human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT)17, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), platelet-derived growth factor, matrix metalloprotease-2 and -9 (MMP 2 and 9)18, and angiogenesis. Furthermore, genistein increases the expression of several histone acetyltransferases (HATs) in LNCaP and DuPro PCa cell lines as well as normal prostate epithelial cells.19 The increased expression of HATs allows for the increased acetylation of histones H3 and H4 which increases the transcription of p21 and p16, genes that induce cell cycle arrest and apoptosis.19 Also, increased H3K9 acetylation by genistein caused the re-expression of important tumor suppressor genes such as PTEN, p53, CYLD and FOXO3a.20

Genistein also exerts antiestrogenic and AR modulation activities. In PCa cells, genistein has been shown to decrease AR protein levels and AR-mediated transcriptional activation of prostate specific antigen (PSA) in androgen-dependent cells.21, 22 Mechanistically, it has been shown that the cellular reduction in AR protein induced by genistein in PCa cell is due to the estrogenic activity of genistein which causes downregulation of HDAC6 and a concomitant inhibition of the chaperone function of HSP90, an activity that is essential for the stability of AR protein.23 The impressive bioactivities of genistein strongly support epidemiological studies which have demonstrated a close association between the intake of soy products rich in genistein and daidzein and the reduction in prostate cancer risk.24 However, other reports suggest that the effect of genistein is highly dependent on the mutational status of the AR. Genistein elicits a biphasic effect in LNCaP cells expressing T877A mutant AR, stimulating cell proliferation, AR expression, and transcriptional activity at physiologically attainable concentrations while inducing antiproliferative activities at higher doses.25, 26

Since AR signaling is vital to the viability of all forms of PCa including CRPC, we postulate that simultaneous inhibition and depletion of AR could prove a beneficial therapeutic strategy for all stage of AR dependent PCa. In this study, we disclose bifunctional agents designed to incorporate the independent cancer killing properties of an antiandrogen and genistein, and the AR downregulation effect of genistein within a single molecular template. We observed that a representative bifunctional agent 9b is much more cytotoxic to LNCaP and DU145 cells relative to the antiandrogen and genistein building blocks as single agents or their combination. Moreover, 9b more effectively down regulates AR protein cellular levels relative to genistein and induces S phase cell cycle arrest.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Conjugate design and synthesis

We have shown that the linkage of aryl hydantoin- and aryl thiohydantoin-based antiandrogens through a short PEG linker to plasmonic gold nanoparticles resulted in nanoconjugates with enhanced antiandrogen activities.27 We envisioned that a similar linkage of the antiandrogen to the O-7 position of genistein, a moiety whose modification is compatible with the bioactivity of genistein, will furnish conjugates (Fig. 1C) possessing AR inhibition and depletion activities.28–30

The synthesis of the requisite antiandrogen-genistein conjugates was achieved using a flexible synthetic route (Scheme 1) which enabled variation of the linker lengths and antiandrogen templates in order test the effects of these changes on the bioactivities of the conjugates. The precursors for the reaction – tetrabutylammonium salt of genistein 1, 2-azidoethyl 4-methylbenzenesulfonate 2, PEG-Tosyl-Azide 4 and thio/hydantoin 6–8 – were prepared as previously reported in the literature. 27, 31–35 Genistein-alkyl-azide 3 and genistein-PEG-azide 5 intermediates were made via the condensation of 1 with 2 and 4, respectively. Subsequent Cu(I) catalyzed Huisgen cycloaddition reactions36 between the azides (3 and 5) and the thio/hydantoin 6–8 yielded the desired conjugates 9a–b, 10a–b, and 11a–b (Scheme 1).

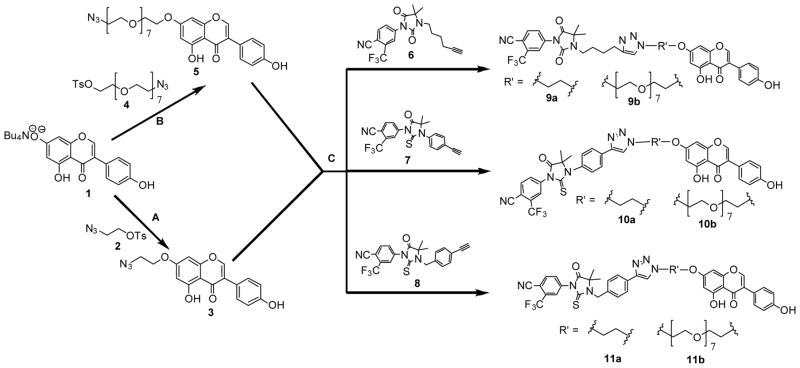

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of antiandrogengenistein conjugates. (A) DMF, 50°C, overnight. (B) DMF, KI, 100°C, overnight. (C) DMSO, DIPEA, CuI, RT, overnight.

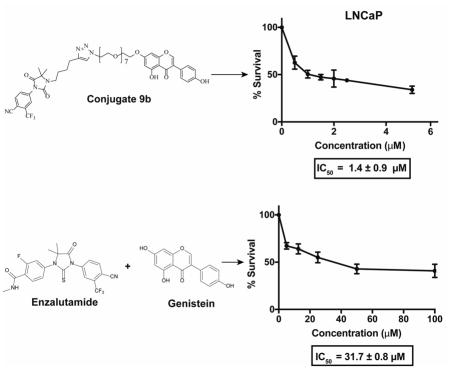

2.2. In vitro anti-proliferative activity study

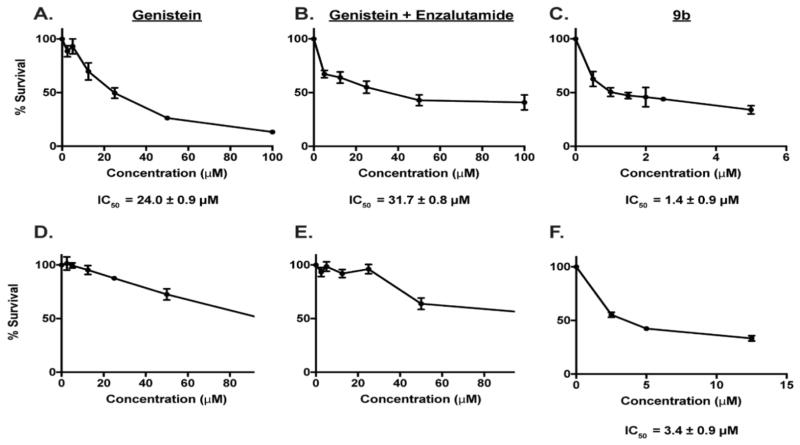

The antiproliferative potential of the synthesized compounds was first evaluated in representative androgen dependent LNCaP and androgen independent DU145 PCa cells lines. A screen of our compounds in LNCaP and DU145 identified 9b as the most potent among the conjugates synthesized while others do not show appreciable activity (data not shown). Importantly, 9b was more potent than the antiandrogen and genistein building blocks, either as single agents or their combination. Specifically, genistein exhibited an IC50 of 24.0 ± 0.9 μM in LNCaP cells and a combination of enzalutamide and genistein did not significantly improve upon the IC50 of genistein, showing IC50 of 31.7 ± 0.8 μM (Fig. 2a–b). The inhibition profile obtained for genistein in LNCaP is within the range of IC50 values (10 μM to 40 μM) reported in the literature.37, 38 In contrast, conjugate (9b) was about 16-fold more potent than genistein, inhibiting the proliferation of LNCaP with an IC50 of 1.4 ± 0.9 μM (Fig. 2c). While genistein and its combination with enzalutamide showed a dose-dependent activity in DU145 cells, 50% inhibition was not obtained within the tested concentration range and we could not calculate the IC50 values (Fig. 2d–e). Gratifyingly, conjugate 9b still exhibited antiproliferative activity against DU145 cells with IC50 of 3.4 ± 0.9 μM (Fig. 2f).

Figure 2.

Dose response curve for (A) genistein, (B) genistein and enzalutamide, and (C) 9b in LNCaP cells. Dose response curves for (D) genistein, (E) genistein and enzalutamide, and (F) 9b in DU145 cells. Data are average of experiments performed in triplicate.

We observed that the percent of LNCaP cell survival for the combination of genistein and enzalutamide hovered around 40% even at concentration as high as 100 μM. Interestingly, conjugate 9b induced a similar effect in both LNCaP and DU145 cells at the low concentration range that enabled IC50 measurement. We reasoned that exposure to higher concentration of 9b will further reduce cell viability below 40%. However, we noticed that higher concentrations of 9b (> 20 μM) resulted in aggregate formation and precipitation of the compound out of the culture media in both LNCaP and DU145. This solubility problem seems to paradoxically blunt the antiproliferative effects of 9b against LNCaP at much higher concentrations while this effect was less pronounced in DU145 cells (Fig. S1).

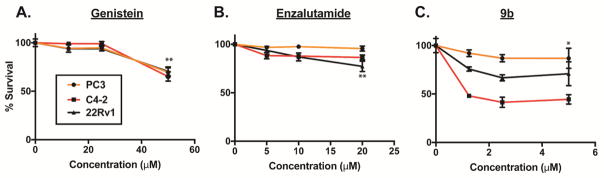

Subsequently, we tested the effects of genistein, enzalutamide and compound 9b on other PCa cell lines – PC3, C4-2 and 22Rv1 (Fig. 3). These cell lines are known to express varying degree of AR and are resistant to anti-androgens. C4-2 is a castration-resistant subline of LNCaP.39 PC3 cell line is a bone metastatic model of human PCa.40 22Rv1 is a castration-resistant subline of CW22R cells, and it was derived from human PCa xenografts via serial circulation in castrated-mice.41 PC3 is AR negative while C4-2 and 22Rv1 cells AR positive. In contrast to C4-2 however, 22Rv1 expresses mostly truncated AR (i.e. lacking the ligand-binding domain of AR). These cells were exposed to varying doses of genistein, enzalutamide, and 9b in serum-fed condition. The effect of agents on cell growth was assessed at 72h post drug treatment.

Figure 3.

Dose response curves for (A) genistein (**=p<0.0006), (B) enzalutamide (**=p<0.002), and (C) 9b (*=p<0.004) in PC3, C4-2, and 22Rv1 cells. Data are average of two independent experiments done in duplicate.

Genistein, at the highest dose tested (50 μM), reduced the growth of PC3, C4-2 and 22Rv1 cells by about 40%, suggesting that genistein also inhibits cell growth independently of AR signaling. As predicted, PC3 cells were resistant to enzalutamide because its growth is not dependent on AR signaling. As expected, enzalutamide modestly reduced the growth of C4-2 and 22Rv1 cells. At 2.5 μM dose, we observed that 9b only moderately reduced PC3 cell growth (5–10 %) while still maintaining statistical significance. Interestingly however, C4-2 and 22Rv1 cells were sensitive to compound 9b, with the full-length AR expressing C4-2 being more sensitive. At 1.25 μM dose, 9b inhibited C4-2 and 22Rv1 cell growth by 50% and 15–20%, respectively. These observations indicate that the presence of the full-length AR may be another key determining factor for the inhibition of PCa cell growth by compound 9b. Collectively, our data suggests that 9b, a conjugate of genistein and a hydantoin-derived antiandrogen, derives its antiproliferative activities against PCa cell lines through a combination of inhibition of AR-dependent and –independent pathways.

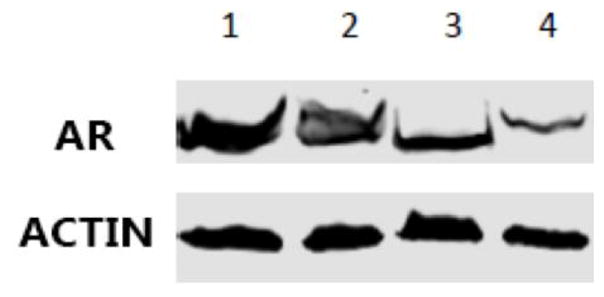

2.3. Effect of 9b on intracellular AR protein levels

To determine if the conjugate 9b retains the AR downregulation activity of genistein, we evaluated its effect on AR protein levels in LNCaP cells. Relative to DMSO control, we observed that 9b induced a dose-dependent downregulation of AR (Fig 4). The AR downregulation activity of 9b was more pronounced than that of genistein as we could only see evidence of AR downregulation in cells treated higher concentration of genistein (2.5 μM for 9b vs 25 μM for genistein) (Fig. S2, lane 2).

Figure 4.

Western blot analysis of AR expression. Lane 1 = DMSO, Lane 2 = 9b (0.5 μM), Lane 3 = 9b (1.25 μM), Lane 4 = 9b (2.5 μM).

Genistein causes AR downregulation through inhibition of HDAC6-Hsp90 cochaperone function.23 However a recent report showed that antiandrogen tagged with hydrophobic moiety derived from adamantyl group simulates AR protein misfolding which is then processed and degraded by the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS).42, 43 To examine the contribution of UPS to the AR downregulation activity of 9b, we incubated cells with various concentrations of compound 9b and the proteasome inhibitor Bortezomib. We observed only a minor increase in AR levels at higher concentration of Bortezomib (Fig S2, compare lanes 4 & 5). This result may suggest that UPS contributes minimally to the mechanism of AR downregulation by 9b. However, this preliminary study could not conclusively ascertain the mechanism of AR downregulation induced by 9b.

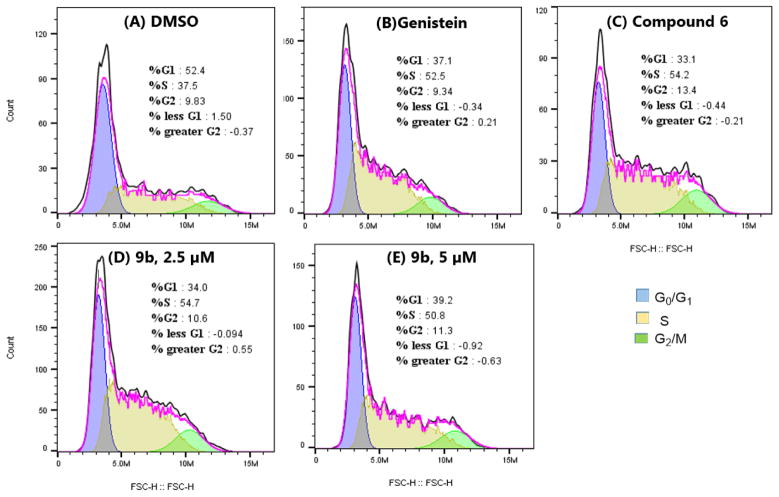

2.4. Effect of 9b on cell cycle progression

To determine if the anti-proliferative activities of 9b result from its alteration of cell cycle pattern, we evaluated the effect of 9b on LNCaP cell cycle progression using DMSO, genistein and antiandrogen compound 6 as controls. We observed that, relative to the DMSO control, 9b, genistein and 6 caused significant increase in cell accumulation at the S-phase after 24 h of treatment. Literature precedent revealed that the effect of genistein on cell cycle is concentration dependent, switching from S-phase arrest at 25 μM (the concentration we tested in this study) to G2/M phase arrest at 100 μM.44 We did not notice any switch in the pattern of cell cycle arrest induced by 9b at the two concentrations that we tested (Fig. 5) as 9b caused S-phase arrest at both concentration. This data suggests that although 9b induced a similar alteration to cell cycle progression as the antiandrogen and genistein building blocks, it elicited this effect at significantly lower concentration than these building blocks.

Figure 5.

Cell cycle profiles of LNCaP cells after treatment with (A) DMSO, (B) genistein (25 μM), (C) compound 6 (40 μM), (D, E) compound 9b at 2.5 μM and 5 μM, respectively.

3. Conclusion

We reported herein a series of bifunctional agents which incorporate the independent cancer killing properties of an antiandrogen and genistein, and the AR downregulation effect of genistein within a single molecular template. We observed that a representative conjugate, 9b, is much more cytotoxic to C4-2, 22Rv1, LNCaP and DU145 cells relative to the antiandrogen and genistein building blocks as single agents or their combination. Although about 2-fold more cytotoxic to LNCaP compared to DU145 cells, the toxicity of 9b toward AR-negative DU145 could be due to promoted uptake by GPCR6A, a cell surface AR-like receptor overexpressed in DU145 and which has been implicated in the cytotoxicity of antiandrogen-tagged nanoparticles.27 Moreover, 9b more effectively down regulates AR protein cellular levels relative to genistein (Supp Info, Fig S2) and induces S-phase cell cycle arrest. Finally, western immunoblotting studies suggest that UPS contribute minimally to the mechanism of AR downregulation by 9b. Collectively, our data suggests that 9b, a conjugate of genistein and hydantoin-derived antiandrogen, derives its antiproliferative activities against PCa cell lines through a combination of inhibition/perturbation of AR-dependent and independent pathways. Further studies are necessary to conclusively validate the mechanism of action of 9b.

4. Experimental

4.1. Materials and methods

All commercially available starting materials were used without further purification. Genistein was procured from TCI America (OR, USA). Reaction solvents were either high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) grade or American Chemical Society (ACS) grade and used without further purification. Analtech silica gel plates (60 F254) were used for analytical TLC, and Analtech preparative TLC plates (UV 254, 2000 μm) were used for purification. UV light was used to examine the spots. 200–400 mesh silica gel was used in column chromatography. For NMR spectra, Varian-Gemini 400 MHz magnetic resonance spectrometer was used. 1H NMR spectra were recorded in parts per million (ppm) relative to the peak of CDCl3, (7.26 ppm) or DMSO-d6 (2.49 ppm). 13C spectra were recorded relative to the central peak of the CDCl3 triplet (77.0 ppm) or the DMSO-d6 septet (39.7 ppm) and were recorded with complete heterodecoupling. Multiplicities are described using the abbreviations: s, singlet; d, doublet, t, triplet; q, quartet; m, multiplet. High-resolution mass spectra were recorded at the Georgia Institute of Technology mass spectrometry facility in Atlanta.

LNCaP and DU145 cells were obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA). Cells were routinely cultured in phenol-red free RPMI-1640 (Lonza, Walkersville, MD) for LNCaP, EMEM (Quality Biological, Gaithersburg, MD) for DU145 following the manufacturer’s suggested protocols with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Atlanta Biologicals, Norcross, GA) and Penicillin/Streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). All cell cultures were incubated at 37 °C under a 5% CO2 atmosphere. The following antibodies were used in immunoblotting studies: AR (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), actin (Cell Signaling Technologies, Danvers, MA). Propidium iodide (Calbiochem-Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany) was used in cell cycle experiments, and Bortezomib (gift from Ronghu Wu’s lab, Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta, GA) was used as a protease inhibitor in immunoblotting in addition to RNAse inhibitor (Amresco, Solon, OH). DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), enzalutamide (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI), and genistein (TCI America, Portland, OR) were used in multiple assays.

4.2. Synthesis of antiandrogen-genistein conjugates

4.2.1. Synthesis of 7-(2-azidoethoxy)-5-hydr oxy-3-(4-hydr oxyphe nyl)-4H-c hr omen-4-one (3)

1 (0.5 g, 0.9 mmol) and 2 (0.56 g, 2.33 mmol) were dissolved in DMF (25 mL). The mixture was reacted overnight at 50° C. The product was purified via column chromatography 5% Acetone: 95% DCM. The product was yielded as a white solid. (232.5 mg, 70.2 %). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 13.03 (s, 1H), 9.69 (s, 1H), 8.48 (s, 1H), 7.51 – 7.37 (m, 2H), 6.92 – 6.80 (m, 2H), 6.74 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H), 6.47 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H), 4.40 – 4.26 (m, 2H), 3.80 – 3.69 (m, 2H). MS (ESI) m/z: 339.09, found 339.18.

4.2.2. Synthesis of 7-((23-azido-3,6,9,12,15,18,21-heptaoxatricosyl)ox y)-5-hydrox y-3-(4-hydr oxyphenyl)-4H-chromen-4-one (5)

1 (0.270 g, 0.525 mmol), 4 (0.318 g, 0.575 mmol) and KI (0.01 g, 0.05 mmol) were dissolved in 5 mL of DMF. The mixture was reacted overnight at 100° C. The product was purified via preparative TLC (1:3 Acetone/DCM and eluent: 2:3 Acetone/DCM). The product was obtained as a pale-yellow oil (330 mg, 96.9 %). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 12.83 (s, 1H), 8.01 (s, 1H), 7.77 (s, 1H), 7.38 – 7.30 (m, 2H), 6.92 – 6.85 (m, 2H), 6.32 (q, J = 2.3 Hz, 2H), 4.11 – 4.03 (m, 2H), 3.87 – 3.81 (m, 2H), 3.74 – 3.67 (m, 4H), 3.67 – 3.62 (m, 22H), 3.40 – 3.34 (m, 2H). HRMS (ESI) m/z calculated for C31H41O12N3Na [M+Na]+: 670.2582, found 670.2572.

4.2.3. Synthesis of 4-(3-(4-(1-(2-((5-hydroxy-3-(4-hydr oxyphenyl)-4-oxo-4H-chromen-7-yl)ox y)ethyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)butyl)-4,4-dimethyl-2,5-dioxoimida zolidin-1-yl)-2-(trifluor omethyl)be nzonitrile (9a)

6 (100 mg, 0.26 mmol), 3 (89.9 mg, 0.26 mmol), and DIPEA (59.93 mg, 0.46 mmol) were dissolved in anhydrous DMSO under argon. Copper (I) Iodide (25.23 mg, 0.13 mmol) was added and the reaction mixture was stirred under argon at ambient temperature overnight. The reaction was diluted with DCM and washed with 1:4 NH4OH/Saturated NH4Cl (3×30 mL) and saturated NH4Cl (30 mL) and the organic layer was dried under sodium sulfate, filtered and concentrated in vacuo. Column chromatography (eluent 80:4:1 – DCM: Acetone: MeOH) gave the product as an orange-white solid (105.3 mg, 56 %). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 9.54 (s, 1H), 8.33 (d, J = 0.8 Hz, 1H), 8.21 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 8.09 (s, 1H), 7.94 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 7.87 (s, 1H), 7.29 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 6.73 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 6.58 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 6.31 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 4.66 (t, J = 5.0 Hz, 2H), 4.43 (t, J = 4.9 Hz, 2H), 2.59 (t, 2H), 1.56 (m, 4H), 1.34 (s, 6H) 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 180.8, 175.1, 164.1, 162.2, 157.9, 157.8, 154.9, 152.9, 147.1, 137.3, 136.5, 130.6, 130.4, 125.3, 124.5, 123.0, 115.5, 106.1, 98.9, 93.4, 68.1, 67.5, 62.0, 61.2, 31.2, 28.8, 26.7, 25.0, 22.9. HRMS (ESI) m/z calculated for C36H32O7N6F3 [M+H]+: 717.2279, found 717.2275.

4.2.4. Synthesis of 4-(3-(4-(1-(2-((5-hydrox y-3-(4-hydr oxyphenyl)-4-oxo-4H-chromen-7-yl)ox y)ethyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)phenyl)-4,4-dimethyl-5-oxo-2-thioxoimida zolidin-1-yl)-2-(trifluoromethyl)ben zonitrile (10a)

7 (121 mg, 1 mmol), 3 (100 mg, 1 mmol), and DIPEA (66 mg, 1.75 mmol) were dissolved in anhydrous DMSO under argon. Copper (I) Iodide (28 mg, 0.5 mmol) was added and the reaction mixture was stirred under argon at ambient temperature overnight. The reaction was diluted with DCM and washed with 1:4 NH4OH/Saturated NH4Cl (3×30 mL) and saturated NH4Cl (30 mL) and the organic layer was dried under sodium sulfate, filtered and concentrated in vacuo. Column chromatography (eluent 80:4:1 – DCM: Acetone: MeOH) gave the product as a white solid (141.1 mg, 77.4%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.87 (s, J = 0.7 Hz, 1H), 9.52 (s, 1H), 8.68 (s, 1H), 8.32 (d, J = 3.2 Hz, 1H), 8.30 (s, 1H), 8.22 (s, 1H), 8.01 (dd, J = 8.4, 2.0 Hz, 1H), 7.96 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.38 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.33 – 7.27 (m, 2H), 6.73 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 6.64 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H), 6.39 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 4.80 (t, J = 5.1 Hz, 2H), 4.52 (t, J = 4.9 Hz, 2H), 1.46 (s, 6H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 180.9, 180.4, 175.4, 164.1, 162.2, 157.9, 157.9, 155.0, 146.0, 138.6, 136.6, 135.2, 134.5, 131.9, 131.4, 130.8, 130.6, 126.7, 123.2, 123.0, 121.4, 115.5, 109.1, 106.2, 99.0, 93.5, 67.3, 66.8, 60.2, 31.2, 23.4, 21.2. HRMS (ESI) m/z calculated for C38H28O6N6F3S [M+H]+: 753.1738, found 753.1714.

4.2.5. Synthesis of 4-(3-(4-(1-(2-((5-hydrox y-3-(4-hydr oxyphenyl)-4-oxo-4H-chromen-7-yl)ox y)ethyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)ben zyl)-4,4-dimethyl-5-oxo-2-thioxoimida zolidin-1-yl)-2-(trifluoromethyl)ben zonitrile (11a)

8 (25 mg, 0.06 mmol), 3 (19.86 mg, 0.06 mmol), and DIPEA (12.9 mg, 0.1 mmol) were dissolved in anhydrous DMSO under argon. Copper (I) Iodide (5.57 mg, 0.03 mmol) was added and the reaction mixture was stirred under argon at ambient temperature overnight. The reaction was diluted with DCM and washed with 1:4 NH4OH/Saturated NH4Cl (3×30 mL) and saturated NH4Cl (30 mL) and the organic layer was dried under sodium sulfate, filtered and concentrated in vacuo. Column chromatography (eluent 80:4:1 – DCM: Acetone: MeOH) gave the product as a white solid (51.5 mg, 87.1%).1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.93 (s, 1H), 9.61 (s, 1H), 8.65 (s, 1H), 8.44 – 8.36 (m, 2H), 8.09 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.82 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.55 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.36 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 6.80 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 6.70 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 6.45 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 5.12 (s, 2H), 4.83 (t, 2H), 4.57 (t, 2H), 1.44 (s, 6H). HRMS (ESI) m/z calculated for C39H30O6N6F3S [M+H]+: 767.1894, found 767.1895.

4.2.6. Synthesis of 4-(3-(4-(1-(23-((5-hydrox y-3-(4-hydr oxyphenyl)-4-oxo-4H-chromen-7-yl)ox y)-3,6,9,12,15,18,21-heptaoxatricosyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)butyl)-4,4-dimethyl-2,5-dioxoimida zolidin-1-yl)-2-(trifluoromethyl)ben zonitrile (9b)

6 (52.4 mg, 0.138 mmol), compound 5 (90 mg, 0.138 mmol), and DIPEA (31.4 mg, 0.241 mmol) were dissolved in anhydrous DMSO under argon. Copper (I) Iodide (13.2 mg, 0.07 mmol) was added and the reaction mixture was stirred under argon at ambient temperature overnight. The reaction was diluted with DCM and washed with 1:4 NH4OH/Saturated NH4Cl (3×30 mL) and saturated NH4Cl (30 mL) and the organic layer was dried under sodium sulfate, filtered and concentrated in vacuo. Column chromatography (eluent 80:4:1 – DCM: Acetone: MeOH) gave the product. The product was lyophilized and gave a yellow oil (15.2 mg, 12.8 %). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ12.83 (s, 1H), 8.11 (s, 1H), 7.97 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 7.87 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.78 (s, 1H), 7.52 (s, 1H), 7.31 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 6.90 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 6.32 (dd, J = 12.4, 2.2 Hz, 2H), 4.48 (t, 2H), 4.10 (t, 2H), 3.82 (m, 4H), 3.60 (m, J = 10.2 Hz, 24H), 3.35 (t, 2H), 2.75 (t, 2H), 1.75 (m, 4H), 1.48 (s, 6H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 180.8, 174.7, 164.6, 162.5, 161.0, 157.8, 157.2, 152.6, 136.5, 135.2, 133.6, 133.3, 130.0, 127.9, 126.0, 123.7, 123.3, 123.0, 122.4, 121.9, 120.6, 115.7, 115.0, 108.1, 106.2, 98.7, 92.9, 70.8, 70.6, 70.4, 69.5, 69.3, 68.0, 61. 9, 50.3, 40.1, 28.9, 26.8, 25.0, 23.5. HRMS (ESI) m/z calculated for C50H60O14N6F3 [M+H]+: 1025.4114, found 1025.4104.

4.2.7. Synthesis of 4-(3-(4-(1-(23-((5-hydrox y-3-(4-hydr oxyphenyl)-4-oxo-4H-chromen-7-yl)ox y)-3,6,9,12,15,18,21-heptaoxatricosyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)phenyl)-4,4-dimethyl-5-oxo-2-thioxoimida zolidin-1-yl)-2-(trifluoromethyl)ben zonitrile (10b)

7 (35.8 mg, 0.086 mmol), 5 (71.2 mg, 0.11 mmol), and DIPEA (18 mg, 0.14 mmol) were dissolved in anhydrous DMSO under argon. Copper (I) Iodide (8.1 mg, 0.043 mmol) was added and the reaction mixture was stirred under argon at ambient temperature overnight. The reaction was diluted with DCM and washed with 1:4 NH4OH/Saturated NH4Cl (3×30 mL) and saturated NH4Cl (30 mL) and the organic layer was dried under sodium sulfate, filtered and concentrated in vacuo. Column chromatography (eluent 80:4:1 – DCM: Acetone: MeOH) gave the product. The product was lyophilized and an orange-white solid was obtained (28.3 mg, 30.7 %). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 12.83 (s, 1H), 8.11 (s, 1H), 8.05 – 7.90 (m, 4H), 7.85 (dd, J = 8.3, 1.9 Hz, 1H), 7.76 (s, 1H), 7.33 (dd, J = 11.2, 8.1 Hz, 4H), 6.90 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 6.31 (q, J = 2.2 Hz, 2H), 4.60 (t, 2H), 4.12 – 3.99 (m, 2H), 3.90 (t, 2H), 3.81 (t, J = 4.5 Hz, 2H), 3.73 – 3.51 (m, 24H), 1.60 (s, 6H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ180.8, 179.8, 175.0, 164.6, 162.5, 157.8, 156.7, 152.7, 146.3, 137.1, 135.2, 134. 5, 133.7, 133.4, 132.2, 130.0, 127.1, 123. 6, 123.2, 122.3, 121.9, 120.5, 115.7, 114.8, 110.1, 106.2, 98.7, 92.9, 70.8, 70.6, 70.5, 70.4, 69.4, 69.3, 67.9, 66.5, 50.5, 23.7. HRMS (ESI) m/z calculated for C52H56O13N6F3S [M+H]+: 1061.3573, found 1061.3568.

4.2.8. Synthesis of 4-(3-(4-(1-(23-((5-hydrox y-3-(4-hydr oxyphenyl)-4-oxo-4H-chromen-7-yl)ox y)-3,6,9,12,15,18,21-heptaoxatricosyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)benzyl)-4,4-dimethyl-5-oxo-2-thioxoimida zolidin-1-yl)-2-(trifluoromethyl)ben zonitrile (11b)

8 (25 mg, 0.06 mmol), compound 5 (38.5 mg, 0.06 mmol), and DIPEA (12.9 mg, 0.1 mmol) were dissolved in anhydrous DMSO under argon. Copper (I) Iodide (5.57 mg, 0.03 mmol) was added and the reaction mixture was stirred under argon at ambient temperature overnight. The reaction was diluted with DCM and washed with 1:4 NH4OH/Saturated NH4Cl (3×30 mL) and saturated NH4Cl (30 mL) and the organic layer was dried under sodium sulfate, filtered and concentrated in vacuo. Purification with preparative TLC (eluent 80:4:1 – DCM: Acetone: MeOH) gave the product. The product was lyophilized and this gave a red-orange solid (22.1 mg, 34.3 %) 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 12.83 (s, 1H), 8.06 (d, J = 11.9 Hz, 1H), 7.99 – 7.90 (m, 2H), 7.83 (dd, J = 8.2, 2.1 Hz, 3H), 7.77 (s, 1H), 7.47 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 7.32 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 6.91 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 6.36 – 6.28 (m, 2H), 5.13 (s, 2H), 4.58 (t, 2H), 4.07 (t, J = 4.7 Hz, 2H), 3.89 (t, 2H), 3.82 (t, J = 4.7 Hz, 2H), 3.71 – 3.49 (m, 24H), 1.46 (s, 6H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 180.8, 179.9, 175.4, 164.6, 162.5, 157.8, 156.8, 152.7, 137.3, 135.9, 135.2, 133.6, 133.3, 132.2, 130.1, 128.3, 127.1, 126.2, 123.6, 123.2, 122.2, 121.4, 120.5, 115.7, 114.8, 110.1, 106.2, 98.7, 92.9, 70.8, 70.6, 70.5, 69.4, 69.3, 67.9, 65.4, 53.4, 50.5, 47.3, 29.7, 23.7. HRMS (MALDI) m/z calculated for C53H58O13N6F3S [M+H]+: 1075.3735, found 1075.3768.

4.3. Cell viability assay

For all experiments, cells (4,500 cells per well) were grown in 96-well cell culture treated microtiter plates (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) with the appropriate compound in triplicate for 72 h. An MTS assay (CellTiter 96 Aqueous One Solution, Promega, Madison, WI) was used to determine cell viability following manufacturer instructions. Analysis on GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA) was used to determine IC50 values.

4.4. Western blot analysis

LNCaP cells (106 cells/dish) were seeded in petri dishes 24 hours prior to treatment with various concentrations of compounds for 24h. For the UPS inhibition study, cells were incubated with Bortezomib, a protease inhibitor, at 20 nM and 40 nM for 2 hours, prior to treatment with the target compounds. Thereafter, media was removed and cells were washed with chilled 1X PBS buffer and resuspended in CelLyticM buffer containing a cocktail of protease inhibitor (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Protein concentration was determined through Bradford protein assay. Equal amount of protein was then loaded onto an SDS-page gel (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) and resolved by electrophoresis at a constant voltage of 100 V for 2 h. The gel was transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane and probed for AR, and actin as loading control.

4.5. Cell cycle analysis

LNCaP cells were seeded onto 6-well plates at a density of 1×106 cells in 5 mL of media, and incubated in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37 °C overnight. Following aspiration of media, fresh media containing drugs were added to the cells and incubated for 24 h. After incubation, cells were trypsinized, harvested and fixed with 70% EtOH. Fixed cells were stained with freshly prepared propidium iodide solution containing RNAse A, and then analyzed on flow cytometer (BD FACS Acuri, BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA, USA). Unstained cells were used as control. Each experiment was performed in triplicate.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This project was financially supported in part by NIH grant R21CA185690 (A.K.O.), and NIH/NIMHD/RCMI Grant 5G12MD007590 (B.C.). Alex George is a grateful recipient of the Georgia Tech’s President’s Undergraduate Research Award (PURA).

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version, at: ______

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, United States Cancer Statistics (USCS), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014.

- 2.DeSantis CE, Lin CC, Mariotto AB, Siegel RL, Stein KD, Kramer JL, Alteri R, Robbins AS, Jemal A. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2014;64:252–271. doi: 10.3322/caac.21235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cronauer MV, Schulz WA, Burchardt T, Anastasiadis AG, de la Taille A, Ackermann R, Burchardt M. International journal of oncology. 2003;23:1095–1102. doi: 10.3892/ijo.23.4.1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lamb AD, Massie CE, Neal DE. BJU international. 2014;113:358–366. doi: 10.1111/bju.12415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bennett NC, Gardiner RA, Hooper JD, Johnson DW, Gobe GC. The international journal of biochemistry & cell biology. 2010;42:813–827. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2009.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen Y, Clegg NJ, Scher HI. The Lancet Oncology. 2009;10:981–991. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70229-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shafi AA, Yen AE, Weigel NL. Pharmacology & therapeutics. 2013;140:223–238. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2013.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Linja MJ, Savinainen KJ, Saramaki OR, Tammela TL, Vessella RL, Visakorpi T. Cancer research. 2001;61:3550–3555. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tran C, Ouk S, Clegg NJ, Chen Y, Watson PA, Arora V, Wongvipat J, Smith-Jones PM, Yoo D, Kwon A, Wasielewska T, Welsbie D, Chen CD, Higano CS, Beer TM, Hung DT, Scher HI, Jung ME, Sawyers CL. Science (New York, NY) 2009;324:787–790. doi: 10.1126/science.1168175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gartrell BA, Saad F. Therapeutic advances in urology. 2015;7:194–202. doi: 10.1177/1756287215592288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Attard G, Reid AH, Yap TA, Raynaud F, Dowsett M, Settatree S, Barrett M, Parker C, Martins V, Folkerd E, Clark J, Cooper CS, Kaye SB, Dearnaley D, Lee G, de Bono JS. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26:4563–4571. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.9749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dixon RA, Ferreira D. Phytochemistry. 2002;60:205–211. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(02)00116-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cao C, Li SR, Dai X, Chen YQ, Feng Z, Qin X, Zhao Y, Wu J. Zhonghua shao shang za zhi = Zhonghua shaoshang zazhi = Chinese journal of burns. 2008;24:118–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sasamura H, Takahashi A, Yuan J, Kitamura H, Masumori N, Miyao N, Itoh N, Tsukamoto T. Urology. 2004;64:389–393. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2004.03.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davis JN, Kucuk O, Sarkar FH. Nutrition and cancer. 1999;35:167–174. doi: 10.1207/S15327914NC352_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li Y, Sarkar FH. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2002;8:2369–2377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jagadeesh S, Kyo S, Banerjee PP. Cancer research. 2006;66:2107–2115. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Su S-J, Yeh T-M, Chuang W-J, Ho C-L, Chang K-L, Cheng H-L, Liu H-S, Cheng H-L, Hsu P-Y, Chow N-H. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2005;69:307–318. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Majid S, Kikuno N, Nelles J, Noonan E, Tanaka Y, Kawamoto K, Hirata H, Li LC, Zhao H, Okino ST, Place RF, Pookot D, Dahiya R. Cancer research. 2008;68:2736–2744. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kikuno N, Shiina H, Urakami S, Kawamoto K, Hirata H, Tanaka Y, Majid S, Igawa M, Dahiya R. International journal of cancer Journal international du cancer. 2008;123:552–560. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davis JN, Muqim N, Bhuiyan M, Kucuk O, Pienta KJ, Sarkar FH. International journal of oncology. 2000;16:1091–1097. doi: 10.3892/ijo.16.6.1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davis JN, Kucuk O, Sarkar FH. Molecular carcinogenesis. 2002;34:91–101. doi: 10.1002/mc.10053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Basak S, Pookot D, Noonan EJ, Dahiya R. Molecular cancer therapeutics. 2008;7:3195–3202. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hwang YW, Kim SY, Jee SH, Kim YN, Nam CM. Nutrition and cancer. 2009;61:598–606. doi: 10.1080/01635580902825639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maggiolini M, Vivacqua A, Carpino A, Bonofiglio D, Fasanella G, Salerno M, Picard D, Ando S. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;62:1027–1035. doi: 10.1124/mol.62.5.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mahmoud AM, Zhu T, Parray A, Siddique HR, Yang W, Saleem M, Bosland MC. PLoS One. 2013;8:e78479. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dreaden EC, Gryder BE, Austin LA, Tene Defo BA, Hayden SC, Pi M, Quarles LD, Oyelere AK, El-Sayed MA. Bioconjug Chem. 2012;23:1507–1512. doi: 10.1021/bc300158k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rusin A, Zawisza-Puchalka J, Kujawa K, Gogler-Piglowska A, Wietrzyk J, Switalska M, Glowala-Kosinska M, Gruca A, Szeja W, Krawczyk Z, Grynkiewicz G. Bioorg Med Chem. 2011;19:295–305. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2010.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rusin A, Gogler A, Glowala-Kosinska M, Bochenek D, Gruca A, Grynkiewicz G, Zawisza J, Szeja W, Krawczyk Z. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2009;19:4939–4943. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.07.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rusin A, Krawczyk Z, Grynkiewicz G, Gogler A, Zawisza-Puchalka J, Szeja W. Acta Biochim Pol. 2010;57:23–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grynkiewicz G, Zegrocka-Stendel O, Pucko W, Ramza J, Kościelecka A, Kołodziejski W, WoŸniak K. Journal of Molecular Structure. 2004;694:121–129. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jiao L, Qiu Q, Liu B, Zhao T, Huang W, Qian H. Bioorg Med Chem. 2014;22:6857–6866. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2014.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dreaden EC, Raji IO, Austin LA, Fathi S, Mwakwari SC, Humphries WHt, Kang B, Oyelere AK, El-Sayed MA. Small (Weinheim an der Berg strasse, Germany) 2014;10:1719–1723. doi: 10.1002/smll.201303190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gryder BE, Akbashev MJ, Rood MK, Raftery ED, Meyers WM, Dillard P, Khan S, Oyelere AK. ACS Chem Biol. 2013;8:2550–2560. doi: 10.1021/cb400542w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gryder BE. PhD Dissertation. Georgia Institute of Technology; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bock VD, Hiemstra H, van Maarseveen JH. European Journal of Organic Chemistry. 2006;2006:51–68. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Onozawa M, Fukuda K, Ohtani M, Akaza H, Sugimura T, Wakabayashi K. Japanese journal of clinical oncology. 1998;28:360–363. doi: 10.1093/jjco/28.6.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhao R, Xiang N, Domann FE, Zhong W. Nutrition and cancer. 2009;61:397–407. doi: 10.1080/01635580802582751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thalmann GN, Anezinis PE, Chang SM, Zhau HE, Kim EE, Hopwood VL, Pathak S, von Eschenbach AC, Chung LW. Cancer research. 1994;54:2577–2581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kaighn ME, Narayan KS, Ohnuki Y, Lechner JF, Jones LW. Investigative urology. 1979;17:16–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sramkoski RM, Pretlow TG, 2nd, Giaconia JM, Pretlow TP, Schwartz S, Sy MS, Marengo SR, Rhim JS, Zhang D, Jacobberger JW. In vitro cellular & developmental biology Animal. 1999;35:403–409. doi: 10.1007/s11626-999-0115-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Neklesa TK, Tae HS, Schneekloth AR, Stulberg MJ, Corson TW, Sundberg TB, Raina K, Holley SA, Crews CM. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7:538–543. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gustafson JL, Neklesa TK, Cox CS, Roth AG, Buckley DL, Tae HS, Sundberg TB, Stagg DB, Hines J, McDonnell DP, Norris JD, Crews CM. Angewandte Chemie (International ed in English) 2015;54:9659–9662. doi: 10.1002/anie.201503720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ismail IA, Kang K-S, Lee HA, Kim J-W, Sohn Y-K. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2007;575:12–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.07.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.