Abstract

Synaptic neurotransmission relies on maintenance of the synapse and meeting the energy demands of neurons. Defects in excitatory and inhibitory synapses have been implicated in schizophrenia, likely contributing to positive and negative symptoms as well as impaired cognition. Recently, accumulating evidence suggests bioenergetic systems, important in both synaptic function and cognition, are abnormal in psychiatric illnesses such as schizophrenia. Animal models of synaptic dysfunction demonstrate endophenotypes of schizophrenia, as well as bioenergetic abnormalities. Here we report findings on the bioenergetic interplay of astrocytes and neurons and discuss how dysregulation of these pathways may contribute to the pathogenesis of schizophrenia, highlighting metabolic systems as important therapeutic targets.

Keywords: bioenergetic coupling, schizophrenia, glucose utilization, lactate shuttle, metabolism, mitochondria

Introduction

Schizophrenia is a devastating illness that affects over 2 million people in the U.S. and displays a wide range of psychotic symptoms, as well as cognitive deficits and profound negative symptoms that are often treatment resistant [1–6]. This illness is highly heritable, suggesting a major role for genetic variants in its complex pathophysiology. Large genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have reported over 100 genetic loci containing common alleles conveying minor schizophrenia associations [7], while rare de novo copy number variations (CNVs), which often span multiple genes, confer higher effects on risk [8, 9]. There is accumulating evidence of bioenergetic dysfunction in chronic schizophrenia, including deficits in energy storage and usage in the brain. While it is possible that genetic variation in metabolic genes contributes to these energetic deficits, genetic risk for schizophrenia is conferred by a large number of alleles, with risk variants each typically conferring a small portion of overall risk [10]. Interestingly, these studies demonstrate a convergence of de novo mutations and altered gene expression on sets of functionally related proteins, pointing to the regulation of plasticity at excitatory synapses as a pathogenic mechanism in schizophrenia [9]. Taken together, the bioenergetic deficits and genetic risk for synaptic dysfunction in schizophrenia lead to the following question: how do defects in bioenergetic function develop and contribute to the pathophysiology of this illness?

In this review, we will describe bioenergetic coupling in detail and discuss, in turn, how metabolic dysfunction may contribute to impaired synapse activity and maintenance. We will discuss the role of glucose/lactate utilization in cognition, as well as evidence for bioenergetic changes in schizophrenia. We will consider possible drivers of abnormal bioenergetic coupling, including genetic risk factors for schizophrenia, metabolic consequences of abnormal glutamatergic brain development, and the effects of antipsychotic medications. We will integrate these data into a working model to understand the bioenergetic interplay of astrocytes and neurons in psychiatric disorders (such as schizophrenia) characterized by synaptic dysfunction, and possible treatment strategies.

Bioenergetic coupling and energy supply at the synapse

Bioenergetic coupling in the brain requires the coordination of multiple systems and cell types to deliver energetic substrates in a spatio-temporal manner. There are multiple mechanisms in the brain to meet neuronal energy demands, including glycolysis, oxidative phosphorylation, and lactate uptake. Additionally, glutamate released at the synapse signals increased energetic demand to astrocytes and enhances production of bioenergetic substrates via increased glucose uptake, glycolytic rate, and lactate generation [11–13]. In order to shape plasticity, glutamate levels in the synapse are normally tightly controlled by astrocytes, which remove extracellular glutamate via excitatory amino acid transporters (EAATs)[14]. These transporters rely on the electrochemical gradient maintained by the adenosine triphosphate (ATP) dependent Na+/K+ ATP pump. Thus, the clearance of synaptic glutamate is bioenergetically costly as well.

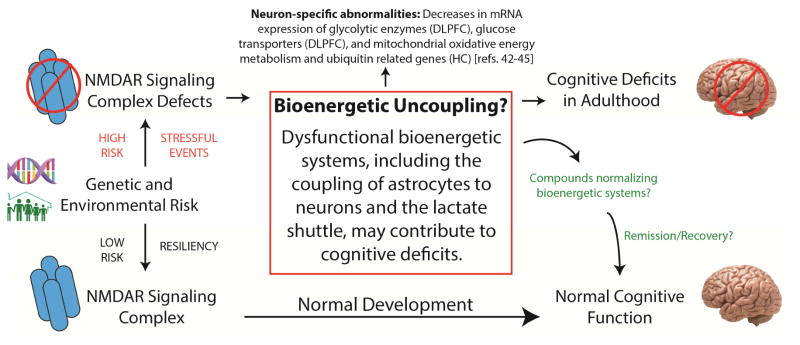

While the role of glutamate clearance in bioenergetic homeostasis is generally well understood, the principal mechanism fulfilling the energy requirements of neurons has been debated. Two bioenergetic ideologies offer viable energy production pathways under normal and pathological conditions. An early hypothesis stated that the main mechanism of energy production for neurotransmission was systemically derived glucose taken up by neurons and metabolized by oxidative phosphorylation [15]. Conversely, a more recent and well-supported hypothesis suggests that astrocytes produce lactate in aerobic conditions (Warburg effect), with lactate shuttling from astrocytes to meet the bioenergetic needs of neurons. Pellerin and Magistretti have termed the net flow of lactate from astrocytes to neurons the “astrocyte-neuron lactate shuttle” (Figure 1), which may help fuel neuronal oxidative phosphorylation [16, 17]. This hypothesis posits that neuronal activation increases the concentration of glutamate in the synapse, activates glycolysis in glycogen rich glial cells even in the presence of normal oxygen levels, and generates lactate which is transported out of astrocytes and into neurons via monocarboxylate transporters (MCTs)[15, 18, 19]. For example, lactate generated by glycolysis in glial cells constitutively supports synaptic transmission even under conditions in which a sufficient supply of glucose and intracellular ATP are present [16]. Lactate production in astrocytes and the lactate shuttle are now thought to be the main mechanisms supporting bioenergetic coupling [20–22]. We discuss both hypotheses in detail in the supplement.

Figure 1.

Bioenergetic coupling in normal brain. Glycolysis and oxidative metabolism via tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle are key pathways in maintaining synaptic function. Both neurons and astrocytes undergo glycolysis even during aerobic conditions. Glucose, which feeds the glycolytic pathway, can enter cells through glucose transporters (GLUTs) or be derived from the breakdown of glycogen in astrocytes. Meeting the energy demand of neurons is highly reliant on the metabolic coupling of neurons to glycolysis and lactate production in astrocytes. There are several key enzymes in glycolysis, including hexokinase (HXK) and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH). This metabolic coupling also requires monocarboxylate transporters (MCTs), which rapidly transport lactate generated by astrocytes into the extracellular space and into neurons. Here lactate is converted back to pyruvate by LDH, which may enter the TCA cycle and oxidative phosphorylation to generate 30–36 molecules of adenosine triphosphate (ATP). This net flow of energetic substrates from astrocytes to neurons to support neuronal activity is termed the “astrocyte-neuron lactate shuttle.”

Glucose/lactate utilization in normal cognition

The importance of glucose/lactate utilization in cognitive function is more resolved. The coupling mechanism between neuronal activity and astrocyte lactate production is essential for working memory performance and long-term memory formation in rodents, which is impaired following disruption of the MCTs and bioenergetic coupling [23, 24]. “Breaking” the lactate shuttle disrupts synaptic transmission, resulting in cognitive impairment [25, 26]. Patients with schizophrenia experience a wide range of psychotic symptoms, as well as profound negative symptoms and cognitive deficits [1–6]. Since bioenergetic coupling and neurotransmission are tightly coupled to cognitive function, these pathways could be important pathophysiological substrates in schizophrenia.

Evidence for abnormal bioenergetic function in schizophrenia from transcriptomic and proteomic studies

Schizophrenia pathology features a number of abnormalities associated with glucose metabolism, the lactate shuttle, and bioenergetic coupling, suggesting energy storage and usage deficits in the brain in this illness (Table 1)[27–40]. Studies employing microarrays found significant decreases in the expression of genes encoding proteins involving the malate shuttle, tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, ornithine–polyamine, aspartate–alanine, and ubiquitin metabolism in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) in schizophrenia. These changes were not attributable to antipsychotic treatment, which may have a restorative effect [37]. Alterations in these genes might have significant implications for oxidative phosphorylation, which is a key mechanism of ATP production for neurotransmission. Other studies implicate mitochondrial dysfunction in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia [39, 40]. Further, a genetic study demonstrated evidence in schizophrenia for linkage between enzymes that control glycolysis, such as 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase 2 (PFKFB2), hexokinase (HXK) 3, and pyruvate kinase (PK) 3, suggesting that genetic risk for this illness includes bioenergetic substrates [41].

Table 1.

Summary of metabolic abnormalities in schizophrenia and models of schizophrenia.

| Model | n # | Brain region | Cell specific? |

Finding | Method | Antipsychotic effect? |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human | 13/group | DLPFC | No | Abnormal TCA cycle activity | Enzyme assays | 9/13 off medication | 27 |

| Human | 3–7/group | Striatum | No | 20% fewer mitochondria | Electron micrographs | May normalize | 28 |

| Human | 26/group | Frontal lobe | No | 22% reduction in creatine kinase kf | 31P-MRS | Unknown | 29 |

| Human | 6–9/group | Wernicke’s area | No | Abnormal expression of metabolic enzymes | 2D-GE-MS | Unknown | 33 |

| Human | 10/group | Prefrontal cortex | No | Mito. function and oxidative stress protein/gene changes | 2D-DIGE and microarrays | 7/10 off medication | 34 |

| Human | 10/group | Prefrontal cortex | No | Decreased TCA/metabolic genes | Microarrays | May normalize | 37 |

| Human | 12–13/group | Cortex, BG, cerebellum | No | Defects in mitochondrial respiratory chain | Enzyme assays | Unknown | 58 |

| Human | 15/group | CSF | No | Elevated CSF lactate | Metabolite analyzer | Trend with decreased CSF lactate | 32 |

| Human | 35/group | DLPFC | No | Abnormal synaptic and metabolic proteins | 2D-GE-MS | Affects some proteins | 35 |

| Human | 15/group | ACC | No | Altered TCA/glycolysis/gluconeogenesis proteins | 2D-GE-MS | Some proteins correlate | 36 |

| Human | 13–15/group | ALIC | No | Decreased lactate (19%)/alanine (24%) | 1H-NMR | Unknown | 38 |

| Human | 987 | n/a | No | PFKFB2, HXK3, PK3 linked to SCZ | Linkage analyses | Minimal | 41 |

| Human | 22–24/group | Hippocampus | Yes | Decrease in mito. oxidative metabolism genes | LCM-microarray | Unlikely | 42 |

| Human | 36/group | DLPFC | Yes | Decrease in mito. and ubiquitin-proteasome genes | LCM-microarray | No | 43 |

| Human | 19/group | DLPFC | Yes | Decrease in mitochondrial energy production genes | LCM-microarray | Unlikely | 44 |

| Human | 16/group | DLPFC | Yes | Decrease in glycolytic/glucose transport genes | LCM-qPCR | Possible | 45 |

| Human | 9–33/group | Nucleus caudatus/cortex gyrus frontalis | No | 63%/43% reduction in COX activity | Assays/PCR | Unknown | 59 |

| Human | 12–19/group | PBMCs | No | Altered glycolytic pathway proteins | LC-MS/assays | Used APD naïve patients | 61 S.I. |

| Human | 7–9/group | DLPFC | No | Abnormal energy metabolism proteins | 2D-DIGE-MS | Unknown | 53 S.I. |

| Human | 48–62/group | Serum/urine | No | Increased pyruvate | NMR | Unknown | 86 S.I. |

| MK-801 treated rat | 5–6/group | Cortex | No | Increased lactate levels | 1D/2D in vivo NMR | No | 42 S.I. |

| MK-801 treated rat | 12/group | Cerebral cortex | No | Abnormal energy metabolism protein expression | 2-DE-MS | No | 30 |

| MK-801 treated rat | 11–12/group | Cortex/hippocampus | No | Disturbed TCA cycle | 1H-MAS-NMR | No | 31 |

| MK-801 treated rat | 4–7/group | Sensory cortices/limbic structures | No | Region specific changes in metabolism | quantitative [14C]2-deoxyglucose autoradiographic | No | 43 S.I. |

| MK-801 treated rat | 9/group | Cortico–striato–thalamo–cortical loop | No | Decreased lactate, reduced glycolysis in parietal/temporal cortex | 13C-NMR-HPLC | No | 45 S.I. |

| PCP treated rat | 8/group | Frontal cortex | No | Decreased pyruvate and PK, altered complex I subunits | 1H-NMR, LCMS, assays | No | 85 S.I. |

| NR1 KD mouse | 12/group | Frontal cortex and hippocampus | No | Increased PK, abnormal glycolysis/gluconeogenesis/TCA | LCMS | No | 131 |

| NR1 KD mouse | 5/group | Cortex | No | Decrease glucose/lactate transporter expression | qPCR | No | 132 |

Abbreviations. Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC); tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA); forward rate constant (kf); magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS); 2 dimensional gel electrophoresis (2D-GE); 2 dimensional difference gel electrophoresis (2D-DIGE); mass spectrometry (MS); mitochondrial (mito.); basal ganglia (BG); cerebral spinal fluid (CSF); anterior cingulate cortex (ACC); anterior limb of the internal capsule (ALIC); nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR); 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-biphosphatase 2 (PFKFB2); hexokinase 3 (HXK3); pyruvate kinase 3 (PK3); schizophrenia (SCZ); laser-capture microdissection (LCM); quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR); cyclooxygenase (COX); peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC); antipsychotic drug (APD); magic angle spin (MAS); high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC); liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LCMS); phencyclidine (PCP); pyruvate kinase (PK); supplementary information (S.I.).

Consistent with these findings, three other groups found cell-specific changes in gene expression of bioenergetic factors in schizophrenia [42–45]. Using dentate granule neuron samples from the hippocampus, one group observed decreases in mRNA expression for clusters of genes that facilitate mitochondrial oxidative energy metabolism, ubiquitin-proteasome systems, and synaptic plasticity [42]. This included transcripts for lactate dehydrogenase A, NADH dehydrogenases, and ATP synthases. Most schizophrenia subjects in this study were on antipsychotic medication at the time of death, although unmedicated and medicated subjects contributed almost equally to these findings. Changes were not observed in bipolar disorder (BPD) or major depression disorder (MDD) subjects, some of which were also on psychotropic medications [42]. Another group found marked decreases in mitochondrial and ubiquitin related genes in layer 3 and 5 pyramidal neurons in the DLPFC of schizophrenia subjects (n=36, n=19)[43, 44]. These results also did not extend to a cohort of BPD or MDD subjects (n=19), suggesting that cell-subtype specific alterations of metabolic gene expression may be unique to schizophrenia. Authors posit these changes in schizophrenia are not due to medication effects, since this cohort of BPD and MDD subjects also included patients on antipsychotic medication, and changes in these transcripts in pyramidal cells in the DLPFC of antipsychotic-treated monkeys were not detected [43]. These findings support a molecular link between signatures of mitochondrial dysfunction and spine pathology in schizophrenia, which is well-documented in this brain region [46–49]. Supporting this hypothesis, ubiquitin-proteasome systems are strongly linked to metabolics and the control of synaptic protein connectivity, signaling, and turnover [50–54]. For instance, degradation of the main positive regulator of glycolysis (PFKFB3) in neurons through the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway would result in an inability to upregulate glycolytic flux during increased synaptic activity [55].

We have recently demonstrated similar metabolic deficits in pyramidal neurons from the DLPFC, including decreases in mRNA expression of glycolytic enzymes (HXK1, PFK1) and glucose transporters (GLUT1, GLUT3) in schizophrenia [45]. These changes were not detected in pyramidal neurons from antipsychotic treated rats, suggesting a neuron-specific deficit in glucose uptake and metabolism in schizophrenia that is not due to medication effects. Alternatively, this finding may reflect a compensatory mechanism for neurons to maintain adequate amounts of glucose entering the pentose pathway, slowing glycolysis in favor of supporting mechanisms that protect from oxidative damage [55]. Decreased glycolysis in neurons could increase the strain on metabolic systems, such as the lactate shuttle, to meet energetic demands. These data are consistent with a hypothesis put forth by McDermott and Silva, who postulated that impaired neuronal uptake of glucose through GLUT1 and GLUT3 could contribute to the pathogenesis of schizophrenia [56]. Taken together, these findings suggest that bioenergetic pathways function differently across different brain regions and are cell-subtype specific. The differential involvement of brain regions, circuits, and cell types is in keeping with the diversity of cognitive symptoms in schizophrenia, since persons afflicted with this illness have heterogeneity in the onset, prognosis, and phenotype of cognitive impairment.

Proteomic analyses also highlight the abnormal expression of bioenergetic targets in schizophrenia [33]. In the posterior superior temporal gyrus, 11 downregulated and 14 upregulated proteins were found in schizophrenia. About half of these hits are enzymes involved the regulation of energy metabolism, such as aldolase C and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, likely to impact bioenergetic systems. The same study also reported differentially expressed ATP synthase subunits, which may result in altered ATP metabolism and ultimately contribute to bioenergetic uncoupling in schizophrenia. Importantly, all schizophrenia subjects in this study were treated with antipsychotic medication. Some proteomic studies suggest that these metabolic abnormalities could be an effect of medication, while others implicate bioenergetic dysfunction as a central element of the disease [36, 41].

Several other postmortem studies have found abnormalities in the activity of metabolic enzymes in schizophrenia. For instance, there is a decrease in first half and an increase in second half TCA cycle enzyme activity in the DLPFC of schizophrenia [27]. Most of these subjects (9/13) were off of antipsychotic medications for at least 6 months prior to death, suggesting that alterations in TCA cycle enzyme activity are a core feature of the illness [41]. We also found decreases in the activity of two glycolytic enzymes, HXK and PFK, in the DLPFC of schizophrenia subjects (n=16)[57]. Other studies have also shown a decrease in specific activity of mitochondrial respiratory chain enzymes in the frontal cortex [58, 59]. These data suggest that functionality of metabolic proteins, and not expression levels alone, could be important in the pathophysiology of chronic schizophrenia.

Postmortem studies have several limitations, such as postmortem interval, mRNA/protein integrity, lifetime effects of medication on brain neurochemistry, and samples that reflect the later or more “mature” stages of the illness. These factors may variably impact dependent measures, including mRNA, protein, and receptor binding site expression [60]. One way to circumvent many of these challenges is to perform studies in living patients. In vivo proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) studies offer a noninvasive approach to directly study brain bioenergetics in schizophrenia. Interestingly, a study employing phosphorous spectroscopy (31P-MRS) found a decrease (22%) in creatine kinase activity in schizophrenia, an enzyme critical for maintaining stable ATP levels during altered neuronal activity [29]. Other MRS studies in medication naïve patients also implicate abnormal bioenergetic pathways in schizophrenia, suggesting that decreases in the availability of high-energy phosphates may be a common feature of the illness [61]. For example, using high field MRS, one study demonstrated elevated in vivo brain lactate levels in patients with schizophrenia, possibly indicating metabolic dysfunction with a shift towards anaerobic glycolysis [62]. However, MRS studies also face limitations. This includes large voxel sizes unable to differentiate contributions from white or gray matter, low signal to noise ratio, long acquisition times, and (often) small sample sizes. Patient variability and methodological differences could contribute to the inconsistent reports from imaging studies on bioenergetics in schizophrenia. However, MRS studies overall have provided meaningful indexes of brain activity and disruption of metabolic energy pathways in schizophrenia at a macroscopic level.

Do certain cell-subtypes exhibit greater bioenergetic susceptibility in schizophrenia?

Apart from pyramidal cells, another class of neurons raises interest due to its particularly high-energy usage and susceptibility to oxidative stress: GABAergic interneurons. Parvalbumin positive (PV+) interneurons are highly sensitive to redox states and reactive oxygen species signaling, and oxidative stress is linked to long lasting PV+ interneuron defects and cognitive deficits in adulthood [63]. Particularly, there is evidence that oxidative stress during the critical window in development leads to loss of PV+ interneurons, and may contribute to abnormal brain development and schizophrenia pathology [63, 64]. Early in development, the accumulation of Cl− by Na-K-Cl cotransporter (NKCC1) results in GABAA receptors exhibiting excitatory properties, stimulating synaptic growth and requiring large amounts of energy. Later in life, GABAA receptors become inhibitory due to the delayed expression of the chloride exporter K-Cl cotransporter (KCC2)[65]. We previously found decreases in KCC2 protein in the DLPFC in schizophrenia, possibly reflecting higher cortical energetic demands similar to that of early in life [66]. Another study found increased mRNA expression of two chloride channel regulatory kinases (OXSR1 and WNK3) in the DLPFC in schizophrenia, suggesting a further dysregulation of chloride transport and energy consumption [67]. Together, these findings suggest abnormal an abnormal GABAergic metabolic profile in schizophrenia, which could be due to oxidative stress.

A brain with dysfunction in multiple brain regions and cell-subtypes such as in schizophrenia may not have the reserve capacity to compensate for this deficit. While there is strong evidence for disruption of limbic circuits in schizophrenia (including frontal cortex, hippocampus, striatum, and thalamus), nearly every brain region has been implicated to an extent (including cerebellum) in schizophrenia pathology. This supports the idea that chronic schizophrenia, often viewed as a developmental illness with synaptic abnormalities, could be accompanied by widespread metabolic dysfunction, attributable to high metabolic demands placed on neurons by the processes involved in neurotransmission.

Glia are another cell type with vital role in bioenergetic homeostasis that may be abnormal in schizophrenia. For instance, a recent study shows that childhood-onset patient derived induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) show delayed differentiation into astrocytes with glial pathology [68]. However, limited work has been done examining bioenergetic processes of glial cells in schizophrenia, and there is little direct evidence for cell-subtype metabolic dysfunction in astrocytes in this illness. However, astrocyte and neuron metabolics are tightly coupled via the glutamate/glutamine cycle, and extensive work has been done examining these substrates in schizophrenia.

The metabolic role of astrocytes in glutamatergic function

It is well established that glutamatergic systems are disrupted in schizophrenia. In normal brain, neurons have lower capacity than astrocytes for glutamate reuptake. Astrocytes are responsible for the majority of glutamate uptake (about 75%) via EAATs and recycle glutamate to the precursor glutamine, which neurons can readily transport [69–71]. This is referred to as the glutamate/glutamine cycle, and is bioenergetically costly. However, glutamate entering astrocytes can meet several metabolic fates, including entering the TCA cycle or lactate/ATP production [72–74]. Studies have confirmed that a significant amount of glutamate is oxidatively metabolized in astrocytes to lactate (by glutamate dehydrogenase and the TCA cycle) when energetic demand is high, and that the amount converted to glutamine is proportionately decreased [70, 73, 74]. Interestingly, EAATs are co-expressed with Na+/K+ ATPases, mitochondria, and glycolytic enzymes to signal rapid glycolysis and lactate generation when neuronal activity is high [75, 76]. Since the glutamate/glutamine cycle in astrocytes is tightly linked to both metabolics and neurotransmission, alterations in this cycle may indicate disrupted bioenergetics coupling between neurons and astrocytes.

We and other groups have found changes in cellular and subcellular localization of glutamate transporters in schizophrenia [75, 77–80]. Abnormal EAAT expression on astrocytes may lead to pathological glutamate spillover, as well as a decrease in the generation of bioenergetic substrates for neuronal consumption [79]. Localization of EAATs impacts synaptic plasticity [77], and changes in localization suggest uncoupling of glutamate transporter protein complexes from mitochondria [78]. Supporting this hypothesis, one study demonstrated decreased labeling of astrocytes adjacent to blood vessels in schizophrenia, suggesting decreased access to the vascular space, which is the primary source of glucose. Such changes could contribute to diminished metabolic capacity [81]. Since astrocytes are integral to the bioenergetic homeostasis and fidelity of synaptic function, targeted studies examining changes in these cells is a promising avenue for understanding the pathophysiology of schizophrenia [82].

What drives metabolic abnormalities in schizophrenia?

Pharmacologic, genetic and theoretical considerations suggest schizophrenia as a developmental disorder with synaptic dysfunction [83–87]. The accumulating evidence discussed above suggests metabolic disturbances are also a key feature of this illness. As the brain develops, bioenergetic organization and the formation of synapses occur simultaneously, creating a fundamentally interdependent system. Reflecting the heterogeneous nature of schizophrenia, some “indirect” cases may develop an intermediate metabolic phenotype secondary to inherited genetic risk for synaptic dysfunction, while some “direct” cases may have genetic risk for impaired bioenergetic systems, leading to the inability of cells to meet the energy demands of synaptic machinery. Thus, metabolic dysfunction may be a primary cause of schizophrenia and/or an intermediate phenotype secondary to synaptic dysfunction.

Genomic variation of synaptic and metabolic systems confers risk for schizophrenia

The genetic risk for schizophrenia is complex and includes numerous synaptic risk factors that appear to contribute to its pathophysiology. For example, genetic susceptibility factors include genes that play roles in NMDAR function, synapse development/plasticity, and postsynaptic pathways [7–9, 84, 88–97]. These prominent abnormalities are part of a complex genetic profile that includes genomic variation in other functionally related groups such as metabolic proteins [37–44]. Thus, the metabolic phenotype observed in schizophrenia could be driven by inherited synaptic and metabolic risk factors, including single-nucleotide polymorphisms or rare CNVs. The combination of synaptic and metabolic genetic insults could coalesce over development, resulting in a brain with synaptic disturbances and diminished bioenergetic capacity. This could contribute to abnormalities described in this illness such as decreased spine density [46, 98], loss of neuropil [99], decreased expression of glutamate transporters [80, 83–87, 100–102], altered expression of glutamate receptors, and other changes [100, 103]. This hypothesis is also supported by genetic linkage studies and numerous findings of abnormally regulated transcripts related to mitochondrial function, glucose utilization, and other high-energy pathways [37–44].

Does synaptic dysfunction during brain development yield an intermediate metabolic phenotype?

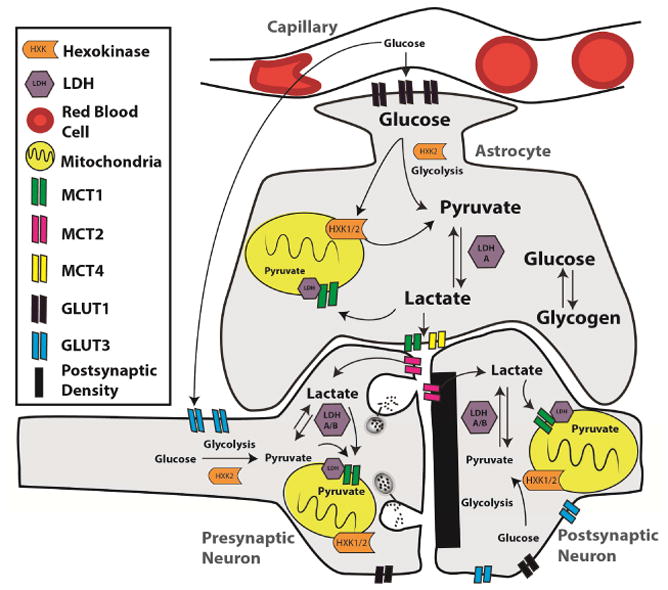

Although alterations in metabolic gene expression may confer some risk for schizophrenia, it is also possible that genetic risks culminating in synaptic dysfunction could be driving perturbations of metabolic systems. Metabolism is intimately linked to normal synaptic function and abnormal synapses are likely to have altered bioenergetic capacity. Developing a brain with synaptic dysfunction could result in an intermediate metabolic phenotype in schizophrenia, which may contribute to cognitive symptoms (Figure 2). This coincides with the developmental nature of schizophrenia, where the age of onset is typically later in life (18–25 years)[104]. Taken together, these data raise the question of whether or not metabolic dysfunction in schizophrenia is genetic, an intermediate phenotype acquired secondary to antipsychotic treatment, or some combination of those factors.

Figure 2.

Genetic and environmental risk factors for schizophrenia include genomic variants and stressful events that impact the NMDA receptor signaling complex. There is a close interrelationship between the development of glutamatergic synapses and the meeting of bioenergetic demands, which if disrupted could in return affect synaptic function, generating a pathological cycle and possibly an intermediate metabolic phenotype. This phenotype could include a metabolic uncoupling of astrocytes and neurons, affecting pathways such as the astrocyte neuron lactate shuttle, and result in an inability to support increases in neuronal activity. There is evidence that the astrocyte neuron lactate shuttle is necessary for cognitive functions such as long-term memory, suggesting bioenergetic uncoupling could contribute to cognitive deficits in adulthood in this illness. Abbreviations. Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC); hippocampus (HC).

Changes in metabolic systems in schizophrenia due to antipsychotic drug treatment

It is possible that metabolic abnormalities in schizophrenia are due to the high percentage of subjects taking antipsychotic medications, often for several decades. Antipsychotic drugs are known to have potent interactions with metabolic pathways in the brain. We discuss this important topic, as well as other drugs that have metabolic effects, in detail in the supplement.

Metabolic abnormalities in drug-naïve patients

Studies in drug-naïve patients offer valuable information on the pathophysiology of schizophrenia. Several studies account for this potential limitation through unmedicated patient populations, which we discuss in detail in the supplement. However, animal models may inform the specific mechanisms underlying these effects.

Animal models as a valuable tool

Given the complex and heterogeneous nature of schizophrenia, it is likely that metabolic genetic predisposition, an intermediate metabolic phenotype secondary to genetic risk for synaptic dysfunction, and treatment with antipsychotic drugs may all contribute to the bioenergetic deficits observed in this illness. Multifaceted contributions can make interpreting human results challenging, highlighting the utility of animal models to better investigate these important questions. Animal models of synaptic dysfunction may provide a tool to address the hypothesis that metabolic disturbances may be an intermediate phenotype secondary to genetic risk for synaptic dysfunction. The evidence suggesting a central role for the glutamatergic system in this illness has led to development of several animal models of synaptic dysfunction. Specifically, defects in NMDARs in schizophrenia [105–113] have led to generation of NMDA receptor hypofunction models [114–120]. For example, the NMDA receptor GluN1 subunit knockdown model demonstrates impaired social interaction, increased stereotypic behaviors, decreased performance in spatial and working memory tasks, and increased auditory and visual event related potentials (suggesting decreased inhibitory tone)[116, 118, 120–122]. Other targeted mutations in genes encoding glutamate receptors result in similar schizophrenia-like phenotypes, several of which have been implicated in schizophrenia (reviewed in [123]). In addition to genetic models, pharmacological models such as administration of phencyclidine, MK-801, and other NMDA-receptor antagonists can induce positive and negative symptoms associated with schizophrenia [124, 125]. NMDA receptor hypofunction models are widely used in schizophrenia research, but are not the only models of dysfunctional synapses. Several other genetic models also exhibit behavioral abnormalities considered endophenotypes for schizophrenia (including astrocyte pathology models), such as GluR-A knockout mice, disrupted in schizophrenia 1 (DISC1) transgenic mice, serine racemase knockout mice, nicotinic receptor knockout mice, and SynGAP heterozygotes (Table 2)[120, 126–130].

Table 2.

Characteristics of Selected Animal Models of Schizophrenia with “Synaptic Dysfunction”

| Animal model | Transgenic? | Memory deficit? | PPI deficit? | Social deficit? | Novel object deficit? | Metabolic disturbance? | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GluR-A knockout | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Unk | 128, 77 S.I. |

| DISC I transgenic | Yes | Females | Yes | Males | No | Unk | 129, 130 |

| SynGAP heterozygotes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Unk | 126 |

| NR1 knockdown | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Altered glycolytic enzymes/glucose transport | 131, 132 |

| α7 nicotinic receptor knockout | Yes | Yes | No | Unk | Unk | Unk | 79 S.I., 80 S.I. |

| α5 nicotinic receptor knockout | Yes | No | No | No | Unk | Unk | 81 S.I. |

| Serine racemase knockout mice | Yes | Yes | Yes | Some | No | Unk | 82 S.I. |

| Acute NMDA antagonism | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Increased lactate and glucose utilization | 119 |

| Chronic PCP administration | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Mitochondrial abnormalities, decreased pyruvate kinase | 85 S.I. | |

| Ketamine administration | No | Yes | Varies | Varies | Varies | Altered PPP and glycolysis/gluconeogenesis metabolites | 84 S.I. |

| MCT4 conditional knockout | No | Yes | Ukn | Ukn | Ukn | Impaired lactate shuttle | 23, 24 |

| Dominant-negative SNARE mice | Yes | Yes | Ukn | Ukn | Ukn | Abnormal ATP/adenosine | 83 S.I. |

Abbreviations. Disrupted in schizophrenia (DISC); synaptic ras GTPase-activating protein (SynGAP); N-methyl d-aspartate (NMDA); pentose phosphate pathway (PPP); monocarboxylate transporter (MCT); soluble attachment protein receptor (SNARE); unknown (Unk); supplementary information (S.I.).

Models informing antipsychotic treatment on metabolic systems

An alternate approach to the challenge of medicated patient populations is using model systems to probe for the effects of antipsychotic drugs on metabolic systems. We discuss this in the supplement.

Evidence for an intermediate metabolic phenotype in genetic models of synaptic dysfunction

There is evidence suggesting developing a brain with synaptic dysfunction yields an intermediate metabolic phenotype. This may be due to failure of astrocytes to develop or maintain metabolic coupling with neurons. There is strong evidence linking glycolysis/lactate shuttle defects to developmental NMDA receptor dysfunction in GluN1 subunit KD mice, including abnormal mitochondrial PK protein expression [30, 131]. It is unclear which isoform (PKM1 or PKM2) is abnormally expressed, an important consideration as isoform expression varies in cells with different glycolytic profiles. We have also shown marked decreases in two metabolic transporters important in this pathway in the frontal cortex of GluN1 KD mice (MCT4, 63% and GLUT3, 60%)[132]. MCT4 plays a vital role in transporting lactate generated from glycolysis in astrocytes into the synaptic cleft for neurons to take up, while GLUT3 transports glucose directly into neurons to be metabolized [133]. Neurons are unable to sustain a high glycolytic flux during prolonged synaptic activity and instead meet their bioenergetic requirements from other sources such as the lactate shuttle, suggesting that defects in lactate transporter MCT4 could lead to bioenergetic uncoupling between cell types [55]. Both synaptic function and meeting of energetic demands are essential for cognition, and failure of either could contribute to the cognitive symptoms seen in schizophrenia. It is possible that defects in excitatory synapses in the GluN1 KD model could lead to a metabolic intermediate phenotype and contribute to poor cognitive performance in these animals. Similar metabolic phenotypes are seen in pharmacological models of NMDA receptor dysfunction.

Conclusions

This review highlights recent work in both human and animal models implicating bioenergetic dysfunction in schizophrenia. Pathogenic mechanisms underlying metabolic defects in schizophrenia are complex and not readily explained by genetic variance or neurochemical changes alone. Adding to this complexity, antipsychotic medications appears to interact with metabolic systems in diverse ways. In vivo and postmortem studies have begun to reveal the consequences of abnormal metabolic gene expression and developing a brain with dysfunctional synapses. In addition, reverse translational approaches have become increasingly valuable, as it is likely that a combination of diverse variables contributes to the bioenergetic deficits in schizophrenia. Teasing apart primary versus secondary causes also poses a challenge not easily overcome by human studies alone, particularly between intertwined entities such as metabolic and synaptic systems. Some bioenergetic disturbances in schizophrenia may be cell or cell-subtype or micro-domain specific, leading to recent studies examining specific cortical lamina, cell subtypes, and microdomains. Collectively, these findings highlight the importance of synaptic and metabolic interplay in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia and provide the framework for future studies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

MH107487, MH107916, MH09445, Lindsay Brinkmeyer Schizophrenia Research Fund, L.I.F.E. (Local Initiative for Excellence) Foundation Award

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures

The authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Association AP. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buchanan RW, Carpenter WT. Schizophrenia: Introduction and overview. In: Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, editors. Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry. Vol. 1. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams, and Wilkins; 2000. pp. 1096–1110. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fleischhacker W. Negative symptoms in patients with schizophrenia with special reference to the primary versus secondary distinction. L’Encephale. 2000;26(1):12–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zanello A, Curtis L, Badan Ba M, Merlo MC. Working memory impairments in first-episode psychosis and chronic schizophrenia. Psychiatry research. 2009;165:10–18. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2007.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Potkin SG, Turner JA, Brown GG, McCarthy G, Greve DN, Glover GH, et al. Working memory and DLPFC inefficiency in schizophrenia: the FBIRN study. Schizophrenia bulletin. 2009;35:19–31. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wobrock T, Schneider M, Kadovic D, Schneider-Axmann T, Ecker UK, Retz W, et al. Reduced cortical inhibition in first-episode schizophrenia. Schizophrenia research. 2008;105:252–261. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics C. Biological insights from 108 schizophrenia- associated genetic loci. Nature. 2014;511:421–427. doi: 10.1038/nature13595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fromer M, Pocklington AJ, Kavanagh DH, Williams HJ, Dwyer S, Gormley P, et al. De novo mutations in schizophrenia implicate synaptic networks. Nature. 2014;506:179–184. doi: 10.1038/nature12929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kirov G, Pocklington AJ, Holmans P, Ivanov D, Ikeda M, Ruderfer D, et al. De novo CNV analysis implicates specific abnormalities of postsynaptic signalling complexes in the pathogenesis of schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 2012;17:142–153. doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Owen MJ, Craddock N, O’Donovan MC. Suggestion of roles for both common and rare risk variants in genome- wide studies of schizophrenia. Archives of general psychiatry. 2010;67:667–673. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pellerin L, Magistretti PJ. Glutamate uptake into astrocytes stimulates aerobic glycolysis: a mechanism coupling neuronal activity to glucose utilization. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1994;91:10625–10629. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.22.10625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chatton JY, Marquet P, Magistretti PJ. A quantitative analysis of L-glutamate-regulated Na+ dynamics in mouse cortical astrocytes: implications for cellular bioenergetics. The European journal of neuroscience. 2000;12:3843–3853. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Loaiza A, Porras OH, Barros LF. Glutamate triggers rapid glucose transport stimulation in astrocytes as evidenced by real-time confocal microscopy. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2003;23:7337–7342. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-19-07337.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Balcar VJ, Johnston GAR. THE STRUCTURAL SPECIFICITY OF THE HIGH AFFINITY UPTAKE OF l-GLUTAMATE AND l-ASPARTATE BY RAT BRAIN SLICES. Journal of neurochemistry. 1972;19:2657–2666. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1972.tb01325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chih CP, Roberts EL., Jr Energy substrates for neurons during neural activity: a critical review of the astrocyte- neuron lactate shuttle hypothesis. Journal of cerebral blood flow and metabolism: official journal of the International Society of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 2003;23:1263–1281. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000081369.51727.6F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nagase M, Takahashi Y, Watabe AM, Kubo Y, Kato F. On-site energy supply at synapses through monocarboxylate transporters maintains excitatory synaptic transmission. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2014;34:2605–2617. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4687-12.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pellerin L, Bouzier-Sore AK, Aubert A, Serres S, Merle M, Costalat R, et al. Activity-dependent regulation of energy metabolism by astrocytes: an update. Glia. 2007;55:1251–1262. doi: 10.1002/glia.20528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Magistretti PJ, Chatton J-Y. Relationship between L-glutamate-regulated intracellular Na+ dynamics and ATP hydrolysis in astrocytes. Journal of Neural Transmission. 2005;112:77–85. doi: 10.1007/s00702-004-0171-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rouach N, Koulakoff A, Abudara V, Willecke K, Giaume C. Astroglial metabolic networks sustain hippocampal synaptic transmission. Science (New York, NY) 2008;322:1551–1555. doi: 10.1126/science.1164022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weber B, Barros LF. The Astrocyte: Powerhouse and Recycling Center. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 2015:7. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a020396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schurr A. Lactate: The Ultimate Cerebral Oxidative Energy Substrate? Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism. 2005;26:142–152. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Magistretti PJ, Allaman I. A cellular perspective on brain energy metabolism and functional imaging. Neuron. 2015;86:883–901. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Newman LA, Korol DL, Gold PE. Lactate produced by glycogenolysis in astrocytes regulates memory processing. PLoS One. 2011;6:e28427. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Suzuki A, Stern SA, Bozdagi O, Huntley GW, Walker RH, Magistretti PJ, et al. Astrocyte-neuron lactate transport is required for long-term memory formation. Cell. 2011;144:810–823. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jolivet R, Allaman I, Pellerin L, Magistretti PJ, Weber B. Comment on recent modeling studies of astrocyte- neuron metabolic interactions. Journal of cerebral blood flow and metabolism: official journal of the International Society of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 2010;30:1982–1986. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2010.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mangia S, DiNuzzo M, Giove F, Carruthers A, Simpson IA, Vannucci SJ. Response to ‘comment on recent modeling studies of astrocyte-neuron metabolic interactions’: much ado about nothing. Journal of cerebral blood flow and metabolism: official journal of the International Society of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 2011;31:1346–1353. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2011.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bubber P, Hartounian V, Gibson GE, Blass JP. Abnormalities in the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle in the brains of schizophrenia patients. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011;21:254–260. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2010.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kung L, Roberts RC. Mitochondrial pathology in human schizophrenic striatum: a postmortem ultrastructural study. Synapse. 1999;31:67–75. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199901)31:1<67::AID-SYN9>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Du F, Cooper AJ, Thida T, Sehovic S, Lukas SE, Cohen BM, et al. In vivo evidence for cerebral bioenergetic abnormalities in schizophrenia measured using 31P magnetization transfer spectroscopy. JAMA psychiatry. 2014;71:19–27. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.2287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou K, Yang Y, Gao L, He G, Li W, Tang K, et al. NMDA receptor hypofunction induces dysfunctions of energy metabolism and semaphorin signaling in rats: a synaptic proteome study. Schizophrenia bulletin. 2012;38:579–591. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbq132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sun L, Li J, Zhou K, Zhang M, Yang J, Li Y, et al. Metabolomic analysis reveals metabolic disturbance in the cortex and hippocampus of subchronic MK-801 treated rats. PloS one. 2013;8:e60598. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Regenold WT, Phatak P, Marano CM, Sassan A, Conley RR, Kling MA. Elevated cerebrospinal fluid lactate concentrations in patients with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia: implications for the mitochondrial dysfunction hypothesis. Biological psychiatry. 2009;65:489–494. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martins-de-Souza D, Gattaz WF, Schmitt A, Novello JC, Marangoni S, Turck CW, et al. Proteome analysis of schizophrenia patients Wernicke’s area reveals an energy metabolism dysregulation. BMC Psychiatry. 2009;9:17. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-9-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Prabakaran S, Swatton JE, Ryan MM, Huffaker SJ, Huang JT, Griffin JL, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction in schizophrenia: evidence for compromised brain metabolism and oxidative stress. Mol Psychiatry. 2004;9:684–697. 643. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pennington K, Beasley CL, Dicker P, Fagan A, English J, Pariante CM, et al. Prominent synaptic and metabolic abnormalities revealed by proteomic analysis of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2008;13:1102–1117. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Beasley CL, Pennington K, Behan A, Wait R, Dunn MJ, Cotter D. Proteomic analysis of the anterior cingulate cortex in the major psychiatric disorders: Evidence for disease-associated changes. Proteomics. 2006;6:3414–3425. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200500069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Middleton FA, Mirnics K, Pierri JN, Lewis DA, Levitt P. Gene expression profiling reveals alterations of specific metabolic pathways in schizophrenia. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2002;22:2718–2729. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-07-02718.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Beasley CL, Dwork AJ, Rosoklija G, Mann JJ, Mancevski B, Jakovski Z, et al. Metabolic abnormalities in fronto- striatal-thalamic white matter tracts in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia research. 2009;109:159–166. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ben-Shachar D. Mitochondrial dysfunction in schizophrenia: a possible linkage to dopamine. Journal of neurochemistry. 2002;83:1241–1251. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ben-Shachar D, Laifenfeld D. Mitochondria, synaptic plasticity, and schizophrenia. International review of neurobiology. 2004;59:273–296. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7742(04)59011-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stone WS, Faraone SV, Su J, Tarbox SI, Van Eerdewegh P, Tsuang MT. Evidence for linkage between regulatory enzymes in glycolysis and schizophrenia in a multiplex sample. American journal of medical genetics Part B, Neuropsychiatric genetics: the official publication of the International Society of Psychiatric Genetics. 2004;127B:5–10. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.20132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Altar CA, Jurata LW, Charles V, Lemire A, Liu P, Bukhman Y, et al. Deficient hippocampal neuron expression of proteasome, ubiquitin, and mitochondrial genes in multiple schizophrenia cohorts. Biological psychiatry. 2005;58:85–96. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Arion D, Corradi JP, Tang S, Datta D, Boothe F, He A, et al. Distinctive transcriptome alterations of prefrontal pyramidal neurons in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2015;20:1397–1405. doi: 10.1038/mp.2014.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Arion D, Huo Z, Enwright JF, Corradi JP, Tseng G, Lewis DA. Transcriptome alterations in prefrontal pyramidal cells distinguish schizophrenia from bipolar and major depressive disorders. Biological psychiatry. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2017.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Courtney Sullivan RK, Hasselfeld Kathryn, O’Donovan Sinead, Ramsey Amy, McCullumsmith Robert. Neuron- specific deficits of neuroenergetic processes in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in schizophrenia. Molecular Psychiatry. 2017 doi: 10.1038/s41380-018-0035-3. Under revision. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Garey LJ, Ong WY, Patel TS, Kanani M, Davis A, Mortimer AM, et al. Reduced dendritic spine density on cerebral cortical pyramidal neurons in schizophrenia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1998;65:446–453. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.65.4.446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Glantz LA, Lewis DA. Decreased dendritic spine density on prefrontal cortical pyramidal neurons in schizophrenia. Archives of general psychiatry. 2000;57:65–73. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Glausier JR, Lewis DA. Dendritic spine pathology in schizophrenia. Neuroscience. 2013;251:90–107. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.04.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kolluri N, Sun Z, Sampson AR, Lewis DA. Lamina-specific reductions in dendritic spine density in the prefrontal cortex of subjects with schizophrenia. The American journal of psychiatry. 2005;162:1200–1202. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.6.1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hegde AN, DiAntonio A. Ubiquitin and the synapse. Nature reviews Neuroscience. 2002;3:854–861. doi: 10.1038/nrn961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Murphey RK, Godenschwege TA. New roles for ubiquitin in the assembly and function of neuronal circuits. Neuron. 2002;36:5–8. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00943-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pak DTS, Sheng M. Targeted Protein Degradation and Synapse Remodeling by an Inducible Protein Kinase. Science (New York, NY) 2003;302:1368–1373. doi: 10.1126/science.1082475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ehlers M. Activity level controls postsynaptic composition and signaling via the ubiquitin-proteasome system. Nature neuroscience. 2003;6:231–242. doi: 10.1038/nn1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Speese SD, Trotta N, Rodesch CK, Aravamudan B, Broadie K. The ubiquitin proteasome system acutely regulates presynaptic protein turnover and synaptic efficacy. Current Biology. 2003;13:899–910. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00338-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Herrero-Mendez A, Almeida A, Fernandez E, Maestre C, Moncada S, Bolanos JP. The bioenergetic and antioxidant status of neurons is controlled by continuous degradation of a key glycolytic enzyme by APC/C-Cdh1. Nature cell biology. 2009;11:747–752. doi: 10.1038/ncb1881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McDermott E, de Silva P. Impaired neuronal glucose uptake in pathogenesis of schizophrenia - can GLUT 1 and GLUT 3 deficits explain imaging, post-mortem and pharmacological findings? Medical hypotheses. 2005;65:1076–1081. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2005.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Courtney Sullivan RK, Hasselfeld Kathryn, O’Donovan Sinead, Ramsey Amy, McCullumsmith Robert. Neuron- specific deficits of neuroenergetic processes in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in schizophrenia. JAMA psychiatry. 2017 doi: 10.1038/s41380-018-0035-3. Under revision. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Maurer I, Zierz S, Möller H-J. Evidence for a mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation defect in brains from patients with schizophrenia. Schizophrenia research. 2001;48:125–136. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(00)00075-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cavelier L, Jazin EE, Eriksson I, Prince J, Bave U, Oreland L, et al. Decreased cytochrome-c oxidase activity and lack of age-related accumulation of mitochondrial DNA deletions in the brains of schizophrenics. Genomics. 1995;29:217–224. doi: 10.1006/geno.1995.1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.McCullumsmith RE, Hammond JH, Shan D, Meador-Woodruff JH. Postmortem brain: an underutilized substrate for studying severe mental illness. Neuropsychopharmacology: official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2014;39:65–87. doi: 10.1038/npp.2013.239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pettegrew JW, Keshavan MS, Panchalingam K, et al. Alterations in brain high-energy phosphate and membrane phospholipid metabolism in first-episode, drug-naive schizophrenics: A pilot study of the dorsal prefrontal cortex by in vivo phosphorus 31 nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Archives of general psychiatry. 1991;48:563–568. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810300075011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rowland LM, Pradhan S, Korenic S, Wijtenburg SA, Hong LE, Edden RA, et al. Elevated brain lactate in schizophrenia: a 7 T magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. Translational psychiatry. 2016;6:e967. doi: 10.1038/tp.2016.239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hardingham GE, Do KQ. Linking early-life NMDAR hypofunction and oxidative stress in schizophrenia pathogenesis. Nature reviews Neuroscience. 2016;17:125–134. doi: 10.1038/nrn.2015.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Powell SB, Sejnowski TJ, Behrens MM. Behavioral and neurochemical consequences of cortical oxidative stress on parvalbumin-interneuron maturation in rodent models of schizophrenia. Neuropharmacology. 2012;62:1322–1331. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.01.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ben-Ari Y. Excitatory actions of gaba during development: the nature of the nurture. Nature reviews Neuroscience. 2002;3:728–739. doi: 10.1038/nrn920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sullivan CR, Funk AJ, Shan D, Haroutunian V, McCullumsmith RE. Decreased chloride channel expression in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in schizophrenia. PloS one. 2015;10:e0123158. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0123158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Arion D, Lewis DA. Altered expression of regulators of the cortical chloride transporters NKCC1 and KCC2 in schizophrenia. Archives of general psychiatry. 2011;68:21–31. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Windrem MS, Osipovitch M, Liu Z, Bates J, Chandler-Militello D, Zou L, et al. Human iPSC Glial Mouse Chimeras Reveal Glial Contributions to Schizophrenia. Cell Stem Cell. 21:195–208. e196. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2017.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Arne Schousboe LKB, Madsen Karsten Kirkegaard, Waagepetersen Helle S. Neuroglia. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2013. Amino acid neurotransmitter synthesis and removal; pp. 443–456. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Schousboe A, Scafidi S, Bak LK, Waagepetersen HS, McKenna MC. Glutamate Metabolism in the Brain Focusing on Astrocytes. Advances in neurobiology. 2014;11:13–30. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-08894-5_2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Petr GT, Sun Y, Frederick NM, Zhou Y, Dhamne SC, Hameed MQ, et al. Conditional Deletion of the Glutamate Transporter GLT-1 Reveals That Astrocytic GLT-1 Protects against Fatal Epilepsy While Neuronal GLT-1 Contributes Significantly to Glutamate Uptake into Synaptosomes. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2015;35:5187–5201. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4255-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.McKenna MC, Sonnewald U, Huang X, Stevenson J, Zielke HR. Exogenous glutamate concentration regulates the metabolic fate of glutamate in astrocytes. Journal of neurochemistry. 1996;66:386–393. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.66010386.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.McKenna MC. Glutamate pays its own way in astrocytes. Frontiers in endocrinology. 2013;4:191. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2013.00191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sonnewald U, Westergaard N, Petersen SB, Unsgard G, Schousboe A. Metabolism of [U-13C]glutamate in astrocytes studied by 13C NMR spectroscopy: incorporation of more label into lactate than into glutamine demonstrates the importance of the tricarboxylic acid cycle. Journal of neurochemistry. 1993;61:1179–1182. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1993.tb03641.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.McCullumsmith RE, O’Donovan SM, Drummond JB, Benesh FS, Simmons M, Roberts R, et al. Cell-specific abnormalities of glutamate transporters in schizophrenia: sick astrocytes and compensating relay neurons? Mol Psychiatry. 2016;6:823–830. doi: 10.1038/mp.2015.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Genda EN, Jackson JG, Sheldon AL, Locke SF, Greco TM, O’Donnell JC, et al. Co-compartmentalization of the astroglial glutamate transporter, GLT-1, with glycolytic enzymes and mitochondria. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2011;31:18275–18288. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3305-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.O’Donovan SM, Hasselfeld K, Bauer D, Simmons M, Roussos P, Haroutunian V, et al. Glutamate transporter splice variant expression in an enriched pyramidal cell population in schizophrenia. Translational psychiatry. 2015;5:e579. doi: 10.1038/tp.2015.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Shan D, Mount D, Moore S, Haroutunian V, Meador-Woodruff JH, McCullumsmith RE. Abnormal partitioning of hexokinase 1 suggests disruption of a glutamate transport protein complex in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia research. 2014;154:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2014.01.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sinead O’Donovan CS, McCullumsmith Robert. The role of glutamate transporters in the pathophysiology of neuropsychiatric disorders. NPJ Schizophrenia. 2017 doi: 10.1038/s41537-017-0037-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Shan D, Lucas EK, Drummond JB, Haroutunian V, Meador-Woodruff JH, McCullumsmith RE. Abnormal expression of glutamate transporters in temporal lobe areas in elderly patients with schizophrenia. Schizophrenia research. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2012.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Webster MJ, Knable MB, Johnston-Wilson N, Nagata K, Inagaki M, Yolken RH. Immunohistochemical localization of phosphorylated glial fibrillary acidic protein in the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus from patients with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and depression. Brain, behavior, and immunity. 2001;15:388–400. doi: 10.1006/brbi.2001.0646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Magistretti PJ. Neuron–glia metabolic coupling and plasticity. Journal of Experimental Biology. 2006;209:2304–2311. doi: 10.1242/jeb.02208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Pongrac J, Middleton FA, Lewis DA, Levitt P, Mirnics K. Gene expression profiling with DNA microarrays: advancing our understanding of psychiatric disorders. Neurochemical research. 2002;27:1049–1063. doi: 10.1023/a:1020904821237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mirnics K, Middleton FA, Lewis DA, Levitt P. Analysis of complex brain disorders with gene expression microarrays: schizophrenia as a disease of the synapse. Trends in neurosciences. 2001;24:479–486. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01862-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Frankle WG, Lerma J, Laruelle M. The synaptic hypothesis of schizophrenia. Neuron. 2003;39:205–216. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00423-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Stephan KE, Friston KJ, Frith CD. Dysconnection in schizophrenia: from abnormal synaptic plasticity to failures of self-monitoring. Schizophrenia bulletin. 2009;35:509–527. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Khvotchev M. Schizophrenia and synapse: emerging role of presynaptic fusion machinery. Biological psychiatry. 2010;67:197–198. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hayashi-Takagi A, Sawa A. Disturbed synaptic connectivity in schizophrenia: convergence of genetic risk factors during neurodevelopment. Brain research bulletin. 2010;83:140–146. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2010.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Harrison PJ, Law AJ. Neuregulin 1 and schizophrenia: genetics, gene expression, and neurobiology. Biological psychiatry. 2006;60:132–140. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Millar JK, Wilson-Annan JC, Anderson S, Christie S, Taylor MS, Semple CA, et al. Disruption of two novel genes by a translocation co-segregating with schizophrenia. Human molecular genetics. 2000;9:1415–1423. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.9.1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Stefansson H, Sigurdsson E, Steinthorsdottir V, Bjornsdottir S, Sigmundsson T, Ghosh S, et al. Neuregulin 1 and susceptibility to schizophrenia. American journal of human genetics. 2002;71:877–892. doi: 10.1086/342734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.St Clair D, Blackwood D, Muir W, Carothers A, Walker M, Spowart G, et al. Association within a family of a balanced autosomal translocation with major mental illness. Lancet. 1990;336:13–16. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)91520-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Gulsuner S, Walsh T, Watts AC, Lee MK, Thornton AM, Casadei S, et al. Spatial and Temporal Mapping of De novo Mutations in Schizophrenia To a Fetal Prefrontal Cortical Network. Cell. 2013;154:518–529. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.06.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Mirnics K, Middleton F, Marquez A, Lewis D, Levitt P. Molecular characterization of schizophrenia viewed by microarray analysis of gene expression in prefrontal cortex. Neuron. 2000;28:53–67. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00085-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Purcell SM, Moran JL, Fromer M, Ruderfer D, Solovieff N, Roussos P, et al. A polygenic burden of rare disruptive mutations in schizophrenia. Nature. 2014;506:185–190. doi: 10.1038/nature12975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kirov G, Rujescu D, Ingason A, Collier DA, O’Donovan MC, Owen MJ. Neurexin 1 (NRXN1) deletions in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia bulletin. 2009;35:851–854. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kirov G, Gumus D, Chen W, Norton N, Georgieva L, Sari M, et al. Comparative genome hybridization suggests a role for NRXN1 and APBA2 in schizophrenia. Human molecular genetics. 2008;17:458–465. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Glantz LA, Lewis DA. Dendritic spine density in schizophrenia and depression. Archives of general psychiatry. 2001;58:203. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.2.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Selemon LD, Goldman-Rakic PS. The reduced neuropil hypothesis: a circuit based model of schizophrenia. Biological psychiatry. 1999;45:17–25. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00281-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Meador-Woodruff J, Clinton S, Beneyto M, McCullumsmith R. Molecular abnormalities of the glutamate synapse in the thalamus in schizophrenia. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2003;1003:75–93. doi: 10.1196/annals.1300.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Spangaro M, Bosia M, Zanoletti A, Bechi M, Cocchi F, Pirovano A, et al. Cognitive dysfunction and glutamate reuptake: effect of EAAT2 polymorphism in schizophrenia. Neuroscience letters. 2012;522:151–155. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2012.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Oni-Orisan A, Kristiansen L, Haroutunian V, Meador-Woodruff J, McCullumsmith R. Altered vesicular glutamate transporter expression in the anterior cingulate cortex in schizophrenia. Biological psychiatry. 2008;63:766–775. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Meador-Woodruff J, Healy D. Glutamate receptor expression in schizophrenic brain. Brain research Brain research reviews. 2000;31:288–294. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(99)00044-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Alda M, Ahrens B, Lit W, Dvorakova M, Labelle A, Zvolsky P, et al. Age of onset in familial and sporadic schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1996;93:447–450. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1996.tb10676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Akbarian S, Sucher NJ, Bradley D, Tafazzoli A, Trinh D, Hetrick WP, et al. Selective alterations in gene expression for NMDA receptor subunits in prefrontal cortex of schizophrenics. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 1996;16:19–30. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-01-00019.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Balu DT, Coyle JT. Neuroplasticity signaling pathways linked to the pathophysiology of schizophrenia. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2011;35:848–870. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Coyle J, Tsai G, Goff D. Converging evidence of NMDA receptor hypofunction in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2003;1003:318–327. doi: 10.1196/annals.1300.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Coyle JT. The glutamatergic dysfunction hypothesis for schizophrenia. Harvard review of psychiatry. 1996;3:241–253. doi: 10.3109/10673229609017192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Funk A, Rumbaugh G, Harotunian V, McCullumsmith R, Meador-Woodruff J. Decreased expression of NMDA receptor-associated proteins in frontal cortex of elderly patients with schizophrenia. Neuroreport. 2009;20:1019–1022. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e32832d30d9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Coyle JT, Tsai G, Goff DC. Ionotropic glutamate receptors as therapeutic targets in schizophrenia. Current drug targets CNS and neurological disorders. 2002;1:183–189. doi: 10.2174/1568007024606212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Luby ED, Cohen BD, Rosenbaum G, Gottlieb JS, Kelley R. Study of a new schizophrenomimetic drug; sernyl. AMA archives of neurology and psychiatry. 1959;81:363–369. doi: 10.1001/archneurpsyc.1959.02340150095011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Krystal JH, Karper LP, Seibyl JP, Freeman GK, Delaney R, Bremner JD, et al. Subanesthetic effects of the noncompetitive NMDA antagonist, ketamine, in humans. Psychotomimetic, perceptual, cognitive, and neuroendocrine responses. Archives of general psychiatry. 1994;51:199–214. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950030035004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Lahti AC, Weiler MA, Tamara Michaelidis BA, Parwani A, Tamminga CA. Effects of ketamine in normal and schizophrenic volunteers. Neuropsychopharmacology: official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;25:455–467. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00243-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Mouri A, Noda Y, Enomoto T, Nabeshima T. Phencyclidine animal models of schizophrenia: approaches from abnormality of glutamatergic neurotransmission and neurodevelopment. Neurochemistry international. 2007;51:173–184. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2007.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Olney JW, Farber NB. Glutamate receptor dysfunction and schizophrenia. Archives of general psychiatry. 1995;52:998–1007. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950240016004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Duncan G, Miyamoto S, Gu H, Lieberman J, Koller B, Snouwaert J. Alterations in regional brain metabolism in genetic and pharmacological models of reduced NMDA receptor function. Brain research. 2002;951:166–176. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03156-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Dzirasa K, Ramsey AJ, Takahashi DY, Stapleton J, Potes JM, Williams JK, et al. Hyperdopaminergia and NMDA receptor hypofunction disrupt neural phase signaling. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2009;29:8215–8224. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1773-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Halene TB, Ehrlichman RS, Liang Y, Christian EP, Jonak GJ, Gur TL, et al. Assessment of NMDA receptor NR1 subunit hypofunction in mice as a model for schizophrenia. Genes, Brain and Behavior. 2009;8:661–675. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2009.00504.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Jentsch JD, Roth RH. The neuropsychopharmacology of phencyclidine: from NMDA receptor hypofunction to the dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology: official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 1999;20:201–225. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(98)00060-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Ramsey AJ. NR1 knockdown mice as a representative model of the glutamate hypothesis of schizophrenia. Progress in brain research. 2009;179:51–58. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(09)17906-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Mohn AR, Gainetdinov RR, Caron MG, Koller BH. Mice with reduced NMDA receptor expression display behaviors related to schizophrenia. Cell. 1999;98:427–436. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81972-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Duncan GE, Moy SS, Lieberman JA, Koller BH. Effects of haloperidol, clozapine, and quetiapine on sensorimotor gating in a genetic model of reduced NMDA receptor function. Psychopharmacology. 2006;184:190–200. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0214-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Inta D, Monyer H, Sprengel R, Meyer-Lindenberg A, Gass P. Mice with genetically altered glutamate receptors as models of schizophrenia: a comprehensive review. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews. 2010;34:285–294. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Javitt DC, Zukin SR. Recent advances in the phencyclidine model of schizophrenia. The American journal of psychiatry. 1991;148:1301–1308. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.10.1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Rung JP, Carlsson A, Ryden Markinhuhta K, Carlsson ML. (+)-MK-801 induced social withdrawal in rats; a model for negative symptoms of schizophrenia. Progress in neuro-psychopharmacology & biological psychiatry. 2005;29:827–832. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Guo X, Hamilton P, Reish N, Sweatt J, Miller C, Rumbaugh G. Reduced Expression of the NMDA Receptor- Interacting Protein SynGAP Causes Behavioral Abnormalities that Model Symptoms of Schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology: official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009 doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Barkus C, Feyder M, Graybeal C, Wright T, Wiedholz L, Izquierdo A, et al. Do GluA1 knockout mice exhibit behavioral abnormalities relevant to the negative or cognitive symptoms of schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder? Neuropharmacology. 2012;62:1263–1272. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Bannerman DM, Deacon RM, Brady S, Bruce A, Sprengel R, Seeburg PH, et al. A comparison of GluR-A-deficient and wild-type mice on a test battery assessing sensorimotor, affective, and cognitive behaviors. Behav Neurosci. 2004;118:643–647. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.118.3.643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Hikida T, Jaaro-Peled H, Seshadri S, Oishi K, Hookway C, Kong S, et al. Dominant-negative DISC1 transgenic mice display schizophrenia-associated phenotypes detected by measures translatable to humans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:14501–14506. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704774104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Pletnikov MV, Ayhan Y, Nikolskaia O, Xu Y, Ovanesov MV, Huang H, et al. Inducible expression of mutant human DISC1 in mice is associated with brain and behavioral abnormalities reminiscent of schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 2008;13:173–186. 115. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Wesseling H, Guest PC, Lee CM, Wong EH, Rahmoune H, Bahn S. Integrative proteomic analysis of the NMDA NR1 knockdown mouse model reveals effects on central and peripheral pathways associated with schizophrenia and autism spectrum disorders. Molecular autism. 2014;5:38. doi: 10.1186/2040-2392-5-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Courtney Sullivan KC, Koene Rachael, Ramsey Amy, McCullumsmith Robert. Decreased lactate dehydrogenase activity and abnormal expression of lactate shuttle transporters in schizophrenia. Abstract, Society for Neuroscience Meeting; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 133.Bergersen LH. Lactate transport and signaling in the brain: potential therapeutic targets and roles in body–brain interaction. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism. 2015;35:176–185. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2014.206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.