Abstract

Lymphedema often is confused with other causes of extremity edema and enlargement. Understanding the risk factors and physical examination signs of lymphedema can enable the health care practitioner to accurately diagnose patients ∼90% of the time. Confirmatory diagnosis of the disease is made using lymphoscintigraphy. It is important to correctly diagnose patients with lymphedema so that they can be managed appropriately.

Keywords: extremity, lymphedema, lymphoscintigraphy, diagnosis, staging

Lymphedema is divided into primary and secondary disease ( Fig. 1 ). Primary lymphedema is idiopathic and results from an error in lymphatic development. Secondary lymphedema is acquired and caused by injury to a normally developed lymphatic system. Primary lymphedema is rare, affecting ∼1/100,000 children. 1 Secondary lymphedema is uncommon in children, but is responsible for the disease in 99% of adults. 2

Fig. 1.

Types of lymphedema. ( A ) Pediatric primary lymphedema of the left lower extremity. ( B ) Secondary lymphedema of the right arm following breast cancer treatment. ( C ) Secondary lymphedema of the right leg following inguinal lymphadenectomy and radiation for cancer management. ( D ) Bilateral lower extremity obesity-induced lymphedema in a patient with a BMI of 72. BMI, body mass index.

The term “lymphedema” is often used to describe an overgrown limb regardless of the underlying etiology; 25% of patients referred to our center with “lymphedema” do not have the disease. 3 4 Many conditions are confused with lymphedema: capillary malformation, lymphatic malformation, venous malformation, infantile hemangioma, kaposiform hemangioendothelioma, CLOVES syndrome, Klippel–Trénaunay syndrome, Parkes Weber syndrome, hemihypertrophy, lipedema, lipofibromatosis, obesity, post-traumatic swelling, systemic diseases (e.g., cardiac, renal, hepatic, and rheumatologic), and venous insufficiency. 3 4 It is important to accurately determine if a patient has lymphedema so that the individual is managed correctly. Although ∼90% of patients with lymphedema can be diagnosed by history and physical examination, confirmation requires lymphoscintigraphy ( Table 1 ).

Table 1. History and physical examination findings associated with lymphedema.

| Patient history |

|---|

| A parent has lymphedema |

| Turner syndrome, Noonan syndrome |

| Inguinal/axillary lymphadenectomy or radiation |

| Travel to areas endemic for filariasis |

| History of a BMI > 50 |

| Onset 12–18 months after injury to lymph nodes |

| Progressive enlargement of the area |

| Cellulitis |

| Physical examination |

| Arms or legs affected |

| Distal extremity is involved |

| Pitting edema |

| Positive Stemmer sign |

| Circumferential (not axial) overgrowth |

| Scars in axilla or inguinal area |

| Absence of ulceration |

| Body mass index > 50 |

| Lymphatic vesicles, lymphorrhea |

Staging

Regardless of whether a patient has primary or secondary lymphedema, the subsequent pathophysiology of the condition is equivalent. Over time, the diseased area increases in size because the interstitial lymphatic fluid causes subcutaneous fibroadipose production. 5 6 Lymphedema is a chronic condition that does not improve and slowly worsens. Lymphedema progresses through four stages. 7 Stage 0 indicates a normal extremity clinically, but with abnormal lymph transport (i.e., illustrated by lymphoscintigraphy). Stage 1 is early edema, which improves with limb elevation. Stage 2 represents pitting edema that does not resolve with elevation. Stage 3 describes fibroadipose deposition and skin changes. 7

The severity of lymphedema is categorized as mild (<20% increase in extremity volume), moderate (20–40%), or severe (>40%). 7 Limb volume measurements can be made using a tape measure, perometer, or by water displacement. Tape measurements are the least accurate method to determine extremity volume because it must be calculated; it is also difficult to use the exact reference points for future assessments. In addition, depending on how tight the examiner pulls the tape measure, the circumference can change significantly. In children, extremity measurements are particularly problematic because the limbs are still growing.

History

Onset

The onset of the patient's swelling is ascertained because it is an important factor in the diagnosis of lymphedema. Primary lymphedema almost always affects the pediatric population, adult-onset is uncommon. Boys are more likely to present in infancy, while girls commonly develop the disease during adolescence. 2 Secondary lymphedema following lymphadenectomy and/or radiation typically begins 12 to 18 months following the injury to lymph vessels. Three-fourths of patients develop swelling within 3 years after the injury and the risk of lymphedema is 1% each year thereafter. 8 Edema that forms immediately following an injury to an extremity is not consistent with lymphedema.

Axillary or Inguinal Injury

Axillary or inguinal lymph node injury is the most significant risk factor for developing lymphedema. Trauma to the lymphatic vasculature must be severe to cause lymphedema. For example, only one third of women who have axillary lymphadenopathy and radiation develop the condition. 9 Although penetrating trauma to lymph nodes can cause lymphedema, the risk is much lower compared with removal of lymph nodes or radiation. While patients may present with a history of incidental trauma to an extremity with subsequent edema, blunt injury should not cause lymphedema.

Travel

Patients are queried about travel to areas that contain a parasite that may cause lymphedema (filariasis). The majority of cases are in Bangladesh, India, Indonesia, and Nigeria. 10 Other affected areas include Africa (central), Brazil, Burma, China (southern), Dominican Republic, Guiana, Guyana, Haiti, Malaysia, Nile delta, Pacific Islands, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Surinam, and Thailand. 10

Family History

Individuals are asked whether their parents have extremity swelling. If a patient's mother or father has primary lymphedema, it is likely that he/she has the condition.

Co-Morbidities

Individuals with suspected primary lymphedema are queried if they have Noonan or Turner syndrome, which are associated with lymphedema. Severely obese patients with a body mass index (BMI) >50 can develop lower extremity lymphedema, termed “obesity-induced lymphedema.” 11 12

Symptoms

Individuals with lymphedema have an increased risk of infection in the affected area. If a patient has a history of infections in the diseased extremity or genitalia then he/she is more likely to have lymphedema. Lymphedema typically is painless; if a patient complains of significant pain, it is unlikely he/she has the condition. As the size of the extremity enlarges, however, secondary musculoskeletal discomfort can occur. A markedly enlarged lower extremity can inhibit ambulation. Lymphatic vesicles may bleed or leak lymph fluid (lymphorrhea). Cutaneous ulceration is not typical for lymphedema and should suggest an alternate diagnosis (e.g., venous insufficiency).

Physical Examination

Location

Lymphedema almost universally involves an extremity; rarely, isolated genital or another anatomical area may be affected. The distal extremity exhibits edema; if the hand or foot are not involved, the diagnosis of lymphedema should be questioned. If a patient complains of swelling outside of the limbs or genitalia, lymphedema likely is not the cause. However, primary generalized lymphedema (including the face and trunk) can occur rarely. Primary lymphedema affects the lower extremities in 92% of cases, and 50% have bilateral disease. 2 Sixteen percent of children with idiopathic lymphedema have upper extremity disease. 2

Pitting Edema

Patients with lymphedema exhibit pitting edema early in their disease. Even minor swelling can be appreciated because superficial veins are less visible. Pressing the thumb into the dorsum of the hand or foot will illustrate the pitting edema. 13 Over time, the body reacts to the lymphedematous fluid in the extremity by producing subcutaneous fibroadipose tissue. Consequently, on physical examination the amount of pitting edema is reduced. Individuals with long-standing lymphedema may not exhibit pitting edema on physical examination.

Stemmer Sign

A fairly sensitive and specific sign for lymphedema is the Stemmer sign. 14 If the examiner is unable to pinch the skin on the dorsum of the hand or foot (positive Stemmer sign), it is likely the patient has lymphedema. Swelling, inflammation, and adipose deposition cause the skin to thicken, which reduces the ability to lift and pinch the integument of the distal extremity. The Stemmer sign is more sensitive than specific. If the test is positive, it is likely the patient has lymphedema. However, if the examination is negative, the patient may still have lymphedema depending on the severity of their condition and the length of time they have had the disease.

Scars

Patients with possible lymphedema are examined for scars in the axillary and inguinal regions. Injury to these locations can damage lymphatics and cause lymphedema. The presence of radiation skin fibrosis also is ascertained.

Body Mass Index

Individuals referred with possible lymphedema have their height and weight recorded at the time of their consultation. Patients with a BMI >50 are at risk for obesity-induced lymphedema, and individuals with a BMI >60 likely have the disease. 11 12 Obese patients are also examined for areas of massive localized lymphedema (MLL), which can develop in the background of extremity lymphedema. 15 These areas of soft-tissue overgrowth most commonly affect the thigh, abdomen, or pubic area.

Skin Appearance

Patients with primary lymphedema typically have normal appearing skin. However, primary lymphedema can occur with other types of vascular malformations. Because lymphedema is progressive, patients may develop cutaneous problems, such as bleeding from vesicles, hyperkeratosis, and lymphorrhea. Skin ulceration rarely affects patients with lymphedema because their arterial and venous circulations are intact. However, skin breakdown can occur in the most severe cases.

Syndromic Features

Children with suspected primary lymphedema are examined for syndromic characteristics that are associated with the disease: (1) an extra row of eyelashes, eyelid ptosis, and yellow nails (lymphedema distichiasis syndrome); (2) sparse hair, cutaneous telangiectasias (hypotrichosis-lymphedema-telangiectasia syndrome); (3) generalized edema, visceral involvement, developmental delay, flat faces, hypertelorism, and a broad nasal bridge (Hennekam syndrome). 15 Patients with Noonan syndrome may have short stature, pectus excavatum, webbed neck, hypertelorism, low-set ears, and/or a flat nasal bridge. 16 Individuals with Turner syndrome might exhibit short stature, webbed neck, broad chest, and/or low set ears. 17

Imaging

Although lymphedema usually can be identified by history and physical examination, patients often undergo ultrasound, MRI, and/or CT prior to their referral to our center. These tests are not sensitive or specific for lymphedema and only may show skin thickening or subcutaneous edema. Lymphedema cannot be diagnosed by histopathology; biopsy specimens may show non-specific skin and adipose inflammation.

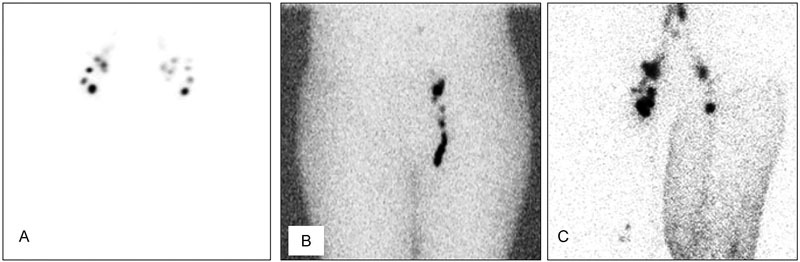

The definitive diagnostic test for lymphedema is lymphoscintigraphy. This study involves the injection of a tracer protein ( 99m Tc-sulfur colloid) into the hand or foot, after which the tracer is preferentially taken up by the lymphatic vasculature. 3 A gamma camera positioned over the patient then detects the 99m Tc-sulfur colloid signal (gamma emissions), with sequential images showing the migration of tracer via the lymphatic system proximally to the inguinal or axillary lymph nodes. Abnormal findings include delayed transit time of the radiolabeled colloid to the regional lymph nodes, dermal backflow (accumulation of tracer in cutaneous lymphatics), asymmetric node uptake, and/or formation of collateral lymphatic channels ( Fig. 2 ). 18 19 The test gives qualitative information (i.e., normal or abnormal lymphatic function) that is 96% sensitive and 100% specific for lymphedema. 20

Fig. 2.

Types of lymphoscintigram results. ( A ) Normal study showing tracer uptake into the bilateral inguinal nodes 45 minutes following injection into the feet. ( B ) Abnormal test illustrating absent uptake of radiolabeled colloid into the right inguinal nodes. ( C ) Abnormal test showing dermal backflow of tracer into the left leg.

Our protocol obtains images at 45 minutes and 2 hours, longer time points are unnecessary. 21 We perform the study on almost all patients referred to our center because the test: (1) confirms lymphedema in patients with an equivocal clinical diagnosis, (2) verifies normal lymphatic function in those suspected to have another condition, or (3) documents the severity of lymphatic dysfunction in patients thought to have lymphedema. 22

Although newer imaging modalities can give information that may be useful for surgical planning, 23 they are not as accurate for diagnosing lymphedema. Magnetic resonance lymphangiography outlines lymphatic vasculature of the limb, but has a sensitivity of 68% for lymphedema. 24 Indocyanine green lymphangiography details subdermal lymphatics, but the specificity for lymphedema is 55%. 25

Conflict of Interest None.

Note

The authors have no financial interest in this manuscript.

References

- 1.Smeltzer D M, Stickler G B, Schirger A. Primary lymphedema in children and adolescents: a follow-up study and review. Pediatrics. 1985;76(02):206–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schook C C, Mulliken J B, Fishman S J, Grant F D, Zurakowski D, Greene A K. Primary lymphedema: clinical features and management in 138 pediatric patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127(06):2419–2431. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318213a218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schook C C, Mulliken J B, Fishman S J, Alomari A I, Grant F D, Greene A K. Differential diagnosis of lower extremity enlargement in pediatric patients referred with a diagnosis of lymphedema. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127(04):1571–1581. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31820a64f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maclellan R A, Couto R A, Sullivan J E, Grant F D, Slavin S A, Greene A K. Management of primary and secondary lymphedema: analysis of 225 referrals to a center. Ann Plast Surg. 2015;75(02):197–200. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0000000000000022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brorson H, Svensson H.Liposuction combined with controlled compression therapy reduces arm lymphedema more effectively than controlled compression therapy alone Plast Reconstr Surg 1998102041058–1067., discussion 1068 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brorson H, Ohlin K, Olsson G, Karlsson M K. Breast cancer-related chronic arm lymphedema is associated with excess adipose and muscle tissue. Lymphat Res Biol. 2009;7(01):3–10. doi: 10.1089/lrb.2008.1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.International Society of Lymphology.The diagnosis and treatment of peripheral lymphedema: 2013 Consensus Document of the International Society of Lymphology Lymphology 201346011–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Petrek J A, Senie R T, Peters M, Rosen P P. Lymphedema in a cohort of breast carcinoma survivors 20 years after diagnosis. Cancer. 2001;92(06):1368–1377. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010915)92:6<1368::aid-cncr1459>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gärtner R, Mejdahl M K, Andersen K G, Ewertz M, Kroman N. Development in self-reported arm-lymphedema in Danish women treated for early-stage breast cancer in 2005 and 2006--a nationwide follow-up study. Breast. 2014;23(04):445–452. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2014.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mendoza N, Li A, Gill A, Tyring S. Filariasis: diagnosis and treatment. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 2009;22(06):475–490. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2009.01271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greene A K, Grant F D, Slavin S A. Lower-extremity lymphedema and elevated body-mass index. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(22):2136–2137. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1201684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greene A K, Grant F D, Slavin S A, Maclellan R A. Obesity-induced lymphedema: clinical and lymphoscintigraphic features. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;135(06):1715–1719. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000001271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bagheri S, Ohlin K, Olsson G, Brorson H. Tissue tonometry before and after liposuction of arm lymphedema following breast cancer. Lymphat Res Biol. 2005;3(02):66–80. doi: 10.1089/lrb.2005.3.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stemmer R. Ein klinisches Zeichen zur Früh- und Differential- diagnose des Lymphödems [A clinical symptom for the early and differential diagnosis of lymphedema] Vasa. 1976;5(03):261–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brouillard P, Boon L, Vikkula M. Genetics of lymphatic anomalies. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(03):898–904. doi: 10.1172/JCI71614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shaw A C, Kalidas K, Crosby A H, Jeffery S, Patton M A. The natural history of Noonan syndrome: a long-term follow-up study. Arch Dis Child. 2007;92(02):128–132. doi: 10.1136/adc.2006.104547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Welsh J, Todd M. Incidence and characteristics of lymphedema in Turner's syndrome. Lymphology. 2006;39(03):152–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gloviczki P, Calcagno D, Schirger Aet al. Noninvasive evaluation of the swollen extremity: experiences with 190 lymphoscintigraphic examinations J Vasc Surg 1989905683–689., discussion 690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Szuba A, Shin W S, Strauss H W, Rockson S. The third circulation: radionuclide lymphoscintigraphy in the evaluation of lymphedema. J Nucl Med. 2003;44(01):43–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hassanein A H, Maclellan R A, Grant F D, Greene A K. Diagnostic accuracy of lymphoscintigraphy for lymphedema and analysis of false-negative tests. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2017;5(07):e1396. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000001396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maclellan R A, Zurakowski D, Voss S, Greene A K. Correlation between lymphedema disease severity and lymphoscintigraphic findings: a clinical-radiologic study. J Am Coll Surg. 2017;225(03):366–370. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2017.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maclellan R A, Greene A K. Lymphedema. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2014;23(04):191–197. doi: 10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2014.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chang D W, Masia J, Garza R, III, Skoracki R, Neligan P C.Lymphedema: surgical and medical therapy Plast Reconstr Surg 2016138(3, Suppl):209S–218S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weiss M, Burgard C, Baumeister R et al. Magnetic resonance imaging versus lymphoscintigraphy for the assessment of focal lymphatic transport disorders of the lower limb: first experiences. Nucl Med (Stuttg) 2014;53(05):190–196. doi: 10.3413/Nukmed-0649-14-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Akita S, Mitsukawa N, Kazama T et al. Comparison of lymphoscintigraphy and indocyanine green lymphography for the diagnosis of extremity lymphoedema. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2013;66(06):792–798. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2013.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]