Abstract

Background

Stroke has a high fatality and disability rate, and is one of the main burdens to human health. It is thus very important to identify biomarkers for the development of effective approaches for the prevention and treatment of stroke. Connexin37 is an anti-inflammatory cytokine and is involved in chronic inflammation and atherosclerosis. Recent studies have found that CONNEXIN37 gene variations are associated with atherosclerosis diseases, such as coronary heart disease and stroke, but its association with stroke in distinct human populations remains to be determined. We report here the analysis of the association of the single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of CONNEXIN37 with ischemic stroke in Han Chinese population.

Methods

Two SNPs of CONNEXIN37 gene were analyzed in 385 ischemic stroke patients and 362 hypertension control patients using ligase detection reaction (LDR) method.

Results

Logistic regression analysis demonstrated that, AG and GG genotypes of SNP rs1764390 and CC genotype of rs1764391 of CONNEXIN37 were associated with an increased risk of ischemic stroke, and that G allele of rs1764390 is a risk factor for ischemic stroke. Further, we found that SNP rs1764390 and SNP rs1764391 in CONNEXIN37 were associated with ischemic stroke under additive/dominant model, and recessive/dominant model, respectively.

Conclusion

Our results indicate that CONNEXIN37 gene polymorphism is an ischemic stroke risk factor in Northern Han Chinese.

Keywords: Stroke, connexin37, SNPs, Han Chinese, Gene polymorphism

Background

Stroke is a complex disease with very high mortality and morbidity [1]. Age, gender, ethnicity, hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, obesity, smoking, poor eating habits and others have been shown to be correlated with stroke [1, 2]. Recent evidences have suggested that the genetic background of an individual contributes to stroke incidence and prognosis [2–6]. Moreover, genetic factors may affect stroke via distinct mechanisms [2, 7], and an individual with a certain gene polymorphism may be more susceptible to stroke and resistant to drug intervention [8–10]. Therefore, gene polymorphism might be an independent risk factor for stroke, suggesting the importance of the identification and validation of biomarkers for the diagnosis, treatment and prognosis of stroke in the era of precision medicine.

Coagulation/fibrinolytic system-related genes, lipoprotein gene, renin-angiotensin system (ACE) related gene, endothelial nitric oxide synthase (NO), methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR), brain natriuretic peptide (BNP), protein kinase C (PKC), PDE4D, and ALOX5AP have been found to be associated with stroke susceptibility [2, 7]. Importantly, emerging data suggest that many gene single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) are correlated with different types of strokes [2, 7]. For example, rs11833579 of WNK and rs12425791 of NINJ2 have been found closely associated with Asian stroke and ischemic stroke, respectively [11], and ARHGEF10 gene polymorphism is closely associated with the risk of ischemic stroke in Northern Han Chinese population [12]. The next challenge would be to elucidate the pathological roles for these genes and SNPs in stroke.

CONNEXIN37 gene (GJA4, also known as Cx37) encodes a gap junction protein. It has been reported that CONNEXIN37 C1019T polymorphism results in the change of proline to serine [13], leading to deregulation of eNOS expression and functions [14]. Moreover, CONNEXIN37 C1019T polymorphism has been revealed to affect endothelial function and elasticity leading to atherosclerosis [15]. Studies in different human races have demonstrated that CONNEXIN37 gene polymorphisms are associated with coronary heart disease [16–19], which increases ACS mortality [20]. Several studies suggest that CONNEXIN37 C1019T polymorphism may be also correlated to acute myocardial infarction [21–24] and subclinical arteries sclerosis indicators such as carotid artery thickness (IMT), arterial compliance and others [25–27]. A 10.7-year cohort study found that C1019T polymorphism of CONNEXIN37 was associated with stroke [25], while another case-control study conducted in Taiwan showed C1019T polymorphism of CONNEXIN37 was not related to Stroke [28]. Therefore, the association of CONNEXIN37 polymorphism with stroke remains to be determined in Chinese and other populations.

In this study, we investigated the CONNEXIN37 SNPs in 385 ischemic stroke patients and 362 hypertension patients without stroke.

Methods

Subjects

A cohort of 385 ischemic stroke patients and 362 control patients were enrolled in this study. The ischemic stroke group included 297 Han Chinese patients as diagnosed during the epidemiological investigation of Fuxin rural areas (Liaoning province, China) between 2004 and 2006 [29], and 88 diagnosed in our hospital. The diagnosis of these 385 ischemic patients was based on WHO standards of thrombotic patients with cerebral infarction and neurological abnormalities. The diagnosis of thrombotic cerebral infarction was confirmed by CT and/or MRI. The 362 control patients were from the same population of ischemic stroke group with matched gender and ethnic during the epidemiological survey. These control patients had hypertension with no history of stroke and other abnormalities, and did not undergo CT or MRI and other imaging studies. The stroke-free patients were controlled for smoking, drinking, blood sugar, cholesterol, obesity and other indicators during the selection [29]. The exclusion criteria were as follows: there was no blood relationship between the selected subjects and the selected subjects had no coronary heart disease, myocardial infarction, carotid and peripheral arterial stenosis, atrial arrhythmias, cancer, or trauma. The participants were not genetically related in three generations. After providing informed consent, 5 ml venous blood was obtained from each participant and kept at − 20 °C until analysis. This study was approved by the ethics committee of China Medical University.

SNP selection and genotyping

Genomic DNA was extracted from EDTA anti-coagulated whole blood in Experimental Center and Virology Laboratory of Shengjing Hospital of China Medical University using TIANamp Blood DNA Kit (Tiangen Biochemical Technology, Beijing, China) according to manufacturer’s protocols. According to the previous literature and NCBI database, genotype detection was selected at the site of secondary allele frequency (MAF) > 0.1 in Beijing Chinese Han population. Tag SNP strategies were used to select the following two potential functional SNPs of CONNEXIN37 gene from the dbSNP and HapMap databases: rs1764391 (ACCCACCCCCTCAGAATGGCCAAAAA[C/T]CCCCAAGTCGTCCCAGCAGCTCTGC); rs1764390 (GGCGAGTCAGTGTGGGGTGACGAGCA[A/G]TCAGATTTCGAGTGTAACACGGCCC). The minor allele frequency (MAF) of these SNPs was greater than 0.1 and pair-wise r2 was more than 0.8. Ligase detection reaction (LDR) method was used for genetyping [30–32]. Primers were designed with Primer 5 and probes were designed by Shanghai Generay Biotech (http://www.generay.com.cn/). The sequences of primers and probes are listed in Tables 1 and 2. Allele and genotype frequencies were determined by analyzing the raw data from ABI 3730XL with Peak Scanner Software v1.0 (ABI). To ensure quality control, genotyping was done without knowledge of case/control status of the subjects, and 10% random samples of cases and controls were genotyped twice by different persons; the reproducibility was 100%.

Table 1.

PCR primer sequences used in this study

| SNP | Primer name | Sequence 5′ to 3′ |

|---|---|---|

| rs1764391 | Forward | GTCTTCTTCTACCTCCCCGTG |

| rs1764391 | Reverse | TTCTCAGGACCCCTCTGTTGG |

| rs1764390 | Forward | TGACGGTGCTCTTCATCTTCC |

| rs1764390 | Reverse | GGTGTGCTGACGAAGAGGAAC |

Table 2.

Probe sequences used in this study

| SNP | Probe name | Sequence 5′ to 3′ |

|---|---|---|

| rs1764391 | TC | CCACCCCCTCAGAATGGCCAAAAAC |

| rs1764391 | TT | TTTCCACCCCCTCAGAATGGCCAAAAAT |

| rs1764391 | TR | p-CCCCAAGTCGTCCCAGCAGCTCTGC-FAM |

| rs1764390 | TA | TTTTCGAGTCAGTGTGGGGTGACGAGCAA |

| rs1764390 | TG | TTTTTTTCGAGTCAGTGTGGGGTGACGAGCAG |

| rs1764390 | TR | p-TCAGATTTCGAGTGTAACACGGCCCTTT-FAM |

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS for Windows software (version 13.0; SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) and SHEsis platform. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) with normal distribution by using the t test. Count data are presented as number of cases and percentage and analyzed using chi-square X2 test. Comparison and analysis of genotype and allele frequencies between cases and controls was performed using Pearson X2 test. The genotype frequencies were tested for Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) using X2 test. SHEsis statistical analysis platform was used to compute haplotype frequencies and linkage disequilibrium coefficient (D’ and r2). Associations between gene polymorphisms and ischemic stroke risk were estimated by computing odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) from unconditional logistic regression models. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Multivariate logistic regression analysis were used after adjusting for age, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, body mass index, smoking and drinking history, triglycerides, high density lipid cholesterol, low density lipid cholesterol and fasting plasma glucose to test the association of gene variation and ischemic stroke risk.

Results

Association between SNPs and ischemic stroke risk

The characteristics of 385 ischemic stroke cases and 362 controls with hypertension are summarized as previously reported [12]. The genotype distributions of CONNEXIN37 rs1764391 and rs1764390 between cases and controls and their associations with ischemic stroke are summarized in Table 3. Recessive, additive and dominant models were applied to test the risk analysis of these variations in stoke patients and control subjects. The associations between these SNPs and IS were also analyzed after adjusting for hypertension diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia and other conventional confounding risk factors. The allele frequencies of CONNEXIN37 gene polymorphisms in controls and cases and their associations with ischemic stroke are shown in Table 4.

Table 3.

Genotype frequencies of CONNEXIN37 gene polymorphisms in cases and controls and their associations with ischemic stroke

| Genotype | IS group (n) | Control group (n) | OR (95%CI)a | P value | Adjusted OR (95%CI)b | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs1764391 | ||||||

| CC | 217 | 242 | ||||

| CT | 160 | 101 | 1.767 (1.297-2.407) | 0.000 | 1.748 (1.149-2.658) | 0.009 |

| TT | 8 | 19 | 0.470 (0.201-1.094) | 0.080 | 0.173 (0.052-0.580) | 0.004 |

| Recessive | 0.383 (0.166-0.886) | 0.025 | 0.138 (0.042-0.459) | 0.001 | ||

| Additive | 1.262 (0.976-1.632) | 0.076 | 1.066 (0.754-1.508) | 0.718 | ||

| Dominant | 1.561 (1.160-2.102) | 0.003 | 1.428 (0.955-2.134) | 0.082 | ||

| rs1764390 | ||||||

| AA | 76 | 100 | ||||

| AG | 223 | 196 | 1.497 (1.050-2.134) | 0.026 | 1.522 (0.937-2.473) | 0.090 |

| GG | 86 | 66 | 1.715 (1.106-2.657) | 0.016 | 1.278 (0.697-2.344) | 0.428 |

| Recessive | 1.290 (0.901-1.847) | 0.164 | 0.950 (0.577-1.565) | 0.841 | ||

| Additive | 1.317 (1.058-1.639) | 0.014 | 1.149 (0.851-1.552) | 0.364 | ||

| Dominant | 1.552 (1.104-2.182) | 0.011 | 1.456 (0.913-2.321) | 0.115 | ||

aUnivariate analysis

bAdjusted OR (Covariates: age, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, body mass index, smoking, drinking history, triglycerides, HDL cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, fasting blood glucose)

Table 4.

Allele frequencies of CONNEXIN37 gene polymorphisms in controls and cases and their associations with ischemic stroke

| Allele | IS group (n) | Control group (n) | OR (95%CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs1764391 | ||||

| C allele | 594 | 585 | 1.00 | – |

| T allele | 176 | 139 | 1.247 (0.971-1.601) | 0.083 |

| rs1764390 | ||||

| A allele | 375 | 396 | 1.00 | – |

| G allele | 395 | 328 | 1.272 (1.038-1.559) | 0.020 |

In the logistic regression models, compared with CC genotype of rs1764391, CT but not TT genotypes were associated with an increased risk of ischemic stroke (OR 1.767, 95%CI 1.297-2.407 for CT, p < 0.001; OR 0.470, 95%CI 0.201-1.094 for TT, p = 0.08, respectively). Under recessive and dominant models, rs1764391 was significantly associated with IS (OR 0.383, 95% CI 0.166-0.886, p = 0.025 and OR 1.561, 95% CI 1.160-2.102, p = 0.003, respectively). After adjustment for stroke risk factors, only under recessive model was rs1764391 associated with IS with OR 0.138 (95% CI0.042-0.459, P = 0.001). The T allele was not associated with ischemic stroke risk with OR of 1.247 (95% CI 0.971-1.601, p = 0.083). These data indicate that the T allele of rs1764391 is not a risk factor for stroke.

In the logistic regression models, compared with AA genotype of rs1764390, AG and GG genotypes were associated with an increased risk of ischemic stroke (OR 1.497, 95% CI 1.050-2.134 for AG, p = 0.026; OR 1.715, 95% CI 1.106-2.657, for GG, p = 0.016, respectively). Under additive and dominant models, rs1764390 was associated with IS with OR and 95% CI 1.317 (1.058-1.639), p = 0.014; 1.552 (1.104-2.182), p = 0.011, respectively. After adjustment for stroke risk factors, the associations did not existed with OR and 95% CI 1.149 (0.851-1.552), P = 0.364; 1.456 (0.913-2.321), P = 0.115, respectively. The G allele was associated with ischemic stroke risk with OR of 1.272 (95% CI 1.038-1.559, p = 0.02). These data indicate that the G allele of rs1764390 is a risk factor for stroke.

Haplotype analysis

We next analyzed the distribution of haplotypes in the cases and controls. The haplotypes with frequencies greater than 0.03% are shown in Table 5. Three haplotypes were constructed in CONNEXIN37 based on the SNPs of rs1764391 and rs1764390. After correcting the P value for multiple testing, we found C-A and T-G were significantly associated with IS with OR and 95% CI 0.813 (0.662-0.998), P = 0.048; 1.403 (1.080-1.822), P = 0.011, respectively.

Table 5.

Frequency distribution of haplotypes of CONNEXIN37 gene in cases and controls

| Haplotype a | IS group (rate) | Control group (rate) | OR (95%CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C-A | 367 (0.476) | 375 (0.518) | 0.813 (0.662-0.998) | 0.048 |

| C-G | 227 (0.295) | 210 (0.290) | 0.996 (0.796-1.246) | 0.972 |

| T-G | 168 (0.218) | 118 (0.163) | 1.403 (1.080-1.822) | 0.011 |

a Frequency of < 0.03 were not included in the analysis

Hardy-Weinberg balance analysis

The observed genotype frequencies of two SNPs followed Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium among the controls (P > 0.05 for two SNPs). For rs1764391, the χ2 and p values were 3.67 and 0.06 for control group, and 12.26 and 0.0005 for the patient group; for rs1764391, the χ2 and p values were 3.098 and 0.078 for control group, and 9.76 and 0.001 for the patient group. These results indicate a balanced genetic and Mendel population.

Linkage disequilibrium test

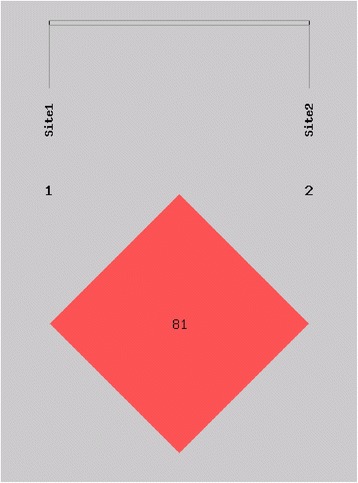

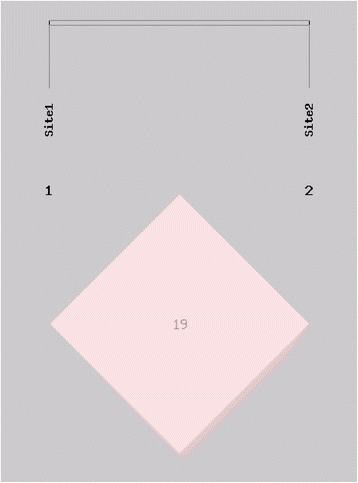

SHEsis statistical analysis of the haplotype frequencies and linkage disequilibrium coefficient (D’ and r2) found that genotype frequencies of the two SNPs followed linkage disequilibrium but at a low level of Linkage Disequilibrium between these SNPs (Table 6 and Figs. 1 and 2).

Table 6.

Linkage disequilibrium test

| SNPs | D’ | r 2 |

|---|---|---|

| rs1764391- rs1764390 | 0.81 | 0.19 |

Fig. 1.

D′of the 2 SNPs. The SNPs rs1764391 and rs1764390 were in linkage disequilibrium

Fig. 2.

r2 of the 2 SNPs. The SNPs rs1764391 and rs1764390 were in linkage disequilibrium

Discussion

In this study, we found that AG and GG genotypes of SNP rs1764390 and CT genotype of rs1764391 in CONNEXIN37 were associated with an increased risk of ischemic stroke, and that G allele of rs1764390 is a risk factor for ischemic stroke. We further demonstrated that SNP rs1764390 and SNP rs1764391 in CONNEXIN37 were associated with ischemic stroke under additive/dominant model, and recessive/dominant model, respectively. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate the association of SNPs rs1764390 and rs1764391 in CONNEXIN37 with ischemic stroke risk in Chinese population.

Stroke is a late-onset disease with age and hypertension the independent risk factors. It has been shown that stroke rate is higher in higher blood pressure and older people [33, 34]. For these reasons, we selected places of residence and sex-matched, higher blood pressure, older patients without stroke as controls. As stroke is a disease of late onset, the selection of older patients as the control group may exclude the potential of genetic background of stroke. Except for obesity and other environmental factors that may be associated with stroke, the genetic factors may have greater impact on the proportion in young patients with relatively low blood pressure. Therefore, this study selected the baseline data that seem not match to highlight the genetic and other factors.

Stroke and coronary heart diseases are all arteriosclerosis-related diseases. It is thus possible that the two diseases may share common susceptible genes. Gap junction proteins are a series of transmembrane proteins that form the gap between cells and allow the exchange of ions and metabolites between cells. Connexin37 is a member of the gap junction protein family, which is mainly expressed in vascular endothelial cells, monocytes and macrophages [13]. These three kinds of cells are the most important cells involved in the arteriosclerosis process. Endothelial dysfunction is the first step of atherosclerosis, followed by migration of mononuclear cells to endothelial cells to form foam macrophages by the absorption of lipid components [35]. Arteriosclerotic mice have found that Connexin37 expression disappears in vascular endothelial cells and increases in foam macrophages [36]. This change in expression suggests that Connexin37 may be associated with arteriosclerosis. Accordingly, it was found that reducing the expression of Connexin37 in leukocytes could increase macrophage foam cells in atherosclerotic plaques, whereas knockout of CONNEXIN37 exacerbates the aortic hardening plaques in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice (ApoE −/−). Wong et al. found that the expression of protein Cx37-pro319 (encoded by allele C) was less adherent than the expressed protein Cx37-ser319 (encoded by allele T) in mononuclear cell lines, suggesting that Connexin37 may inhibit mononuclear cells adhesion, the initiating factor of arteriosclerosis, to reduce atherosclerosis [16].

Previous studies on the CONNEXIN37 gene were focused on rs1764391 locus (C1019T), where the changes in the T and C alleles result in the conversion of proline to tryptophan (P319S), which increases the incidence of myocardial infarction [23, 37]. The results of the study on the relationship between polymorphism and stroke in 2011 suggest that rs1764391 TT and CT (HR 2.83 and 1.69, respectively) have a higher risk ratio than the CC genotype. However, the results of previous studies on the relationship between the rs1764391 allele and atherosclerotic disease are not consistent. Some scholars believe that the two are related, but others think they are irrelevant. Most studies suggest that the C allele is more likely to lead to the occurrence of related diseases, while other studies suggest that the T allele is a causative gene [21, 23, 25, 37]. This difference may be related to the number of cases, but more likely to be associated with the genetic background of different populations. The NCBI database suggests that the frequency of alleles in Asians and Europeans is very different (T 0.151-0.636), indicating difference of the relationship between polymorphism and disease. Therefore, the interpretation of the results should consider different genetic background. Consistent with most previous studies, the results of the present study showed that the rs1764391 locus of the CT + TT and rs1764390 locus AG + GG genotypes was stroke-related, and allele G was the risk of stroke. Our study suggests that the CONNEXIN37 gene mononucleotide polymorphism is associated with ischemic stroke in the northern Chinese Han population. Our findings have provided additional evidence of the importance of CONNEXIN37 in human diseases, especially ischemic stroke.

There are some potential limitations of the present study. First, we only examined the rural elderly patients in Northern China, which may not present on behalf of the populations of other regions, ethnic or social background. Secondly, although Power and Sample Size Calculation (version 3.1.2, 2014) (http://Biostat.mc.vanderbilt.edu/wiki/Main/PowerSampleSize) revealed a power of 0.9 based on the lowest MAF among SNPs [38], the overall sample size was relatively small. Studies of multi-centered with a larger sample size from different regions, ethnic or social background are needed.

Conclusion

Our findings have provided new insights into the roles of CONNEXIN37 SNPs rs1764390 and rs1764391 in the development and progression of ischemic stroke risk in northern Chinese Han population.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all patients for providing blood samples and all the research staff for their contributions to this project.

Funding

This study was supported by the Special Program for National Key Basic Research and Development Program (2010CB535011).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article.

Authors’ contributions

All authors (HL, SY, RW, ZX, XZ, LZ, ZY, and YS) have participated in the conception and design of the study and in the drafting and revising the manuscript. HL, LZ and ZY performed the analysis and interpretation of data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the Ethic Committee of China Medical University and conducted in accordance with Helsinki’s Declaration. All the patients gave their written information consent.

Consent for publication

All authors have reviewed and consented to publication of the paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Hassan A, Markus HS. Genetics and ischaemic stroke. Brain. 2000;123:1784–1812. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.9.1784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Markus HS, Bevan S. Mechanisms and treatment of ischaemic stroke--insights from genetic associations. Nat Rev Neurol. 2014;10:723–730. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2014.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bak S, Gaist D, Sindrup SH, Skytthe A, Christensen K. Genetic liability in stroke: a long-term follow-up study of Danish twins. Stroke. 2002;33:769–774. doi: 10.1161/hs0302.103619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ikram MA, Seshadri S, Bis JC, Fornage M, DeStefano AL, Aulchenko YS, Debette S, Lumley T, Folsom AR, van den Herik EG, et al. Genomewide association studies of stroke. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1718–1728. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0900094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flossmann E, Schulz UG, Rothwell PM. Systematic review of methods and results of studies of the genetic epidemiology of ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2004;35:212–227. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000107187.84390.AA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Munshi A, Das S, Kaul S. Genetic determinants in ischaemic stroke subtypes: seven year findings and a review. Gene. 2015;555:250–259. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2014.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raphaeli G, Mazighi M, Pereira VM, Turjman F, Striefler J. State-of-the-art endovascular treatment of acute ischemic stroke. Adv Tech Stand Neurosurg. 2015;42:33–68. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-09066-5_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kumar P, Kumar A, Srivastava MK, Misra S, Pandit AK, Prasad K. Association of transforming growth factor beta-1-509C/T gene polymorphism with ischemic stroke: a meta analysis. Basic Clin Neurosci. 2016;7:91–96. doi: 10.15412/J.BCN.03070202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yan Y, Luo X, Zhang J, Su L, Liang W, Huang G, Wu G, Huang G, Gu L. Association between phosphodiesterase 4D polymorphism SNP83 and ischemic stroke. J Neurol Sci. 2014;338:3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2013.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kotlega D, Golab-Janowska M, Masztalewicz M, Ciecwiez S, Nowacki P. Association between selected gene polymorphisms and statin metabolism, risk of ischemic stroke and cardiovascular disorders. Postepy Hig Med Dosw (Online) 2016;70:435–447. doi: 10.5604/17322693.1201197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li BH, Zhang LL, Yin YW, Pi Y, Guo L, Yang QW, Gao CY, Fang CQ, Wang JZ, Li JC. Association between 12p13 SNPs rs11833579/rs12425791 near NINJ2 gene and ischemic stroke in East Asian population: evidence from a meta-analysis. J Neurol Sci. 2012;316:116–121. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2012.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li H, Yu S, Wang R, Sun Z, Zhou X, Zheng L, Yin Z, Zhang X, Sun Y. ARHGEF10 gene polymorphism is closely associated with the risk of ischemic stroke in Northern Han Chinese population. Neurol Res. 2017;39:158–164. doi: 10.1080/01616412.2016.1263175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chanson M, Kwak BR. Connexin37: a potential modifier gene of inflammatory disease. J Mol Med (Berl) 2007;85:787–795. doi: 10.1007/s00109-007-0169-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alonso F, Boittin FX, Beny JL, Haefliger JA. Loss of connexin40 is associated with decreased endothelium-dependent relaxations and eNOS levels in the mouse aorta. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;299:H1365–H1373. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00029.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Collings A, Raitakari OT, Juonala M, Mansikkaniemi K, Kahonen M, Hutri-Kahonen N, Marniemi J, Viikari JS, Lehtimaki TJ. The influence of smoking and homocysteine on subclinical atherosclerosis is modified by the connexin37 C1019T polymorphism - the cardiovascular risk in Young Finns study. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2008;46:1102–1108. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2008.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wong CW, Christen T, Pfenniger A, James RW, Kwak BR. Do allelic variants of the connexin37 1019 gene polymorphism differentially predict for coronary artery disease and myocardial infarction? Atherosclerosis. 2007;191:355–361. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yeh HI, Chou Y, Liu HF, Chang SC, Tsai CH. Connexin37 gene polymorphism and coronary artery disease in Taiwan. Int J Cardiol. 2001;81:251–255. doi: 10.1016/S0167-5273(01)00574-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Horan PG, Allen AR, Patterson CC, Spence MS, McGlinchey PG, McKeown PP. The connexin 37 gene polymorphism and coronary artery disease in Ireland. Heart. 2006;92:395–396. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2004.055665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Han Y, Xi S, Zhang X, Yan C, Yang Y, Kang J. Association of connexin 37 gene polymorphisms with risk of coronary artery disease in northern Han Chinese. Cardiology. 2008;110:260–265. doi: 10.1159/000112410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lanfear DE, Jones PG, Marsh S, Cresci S, Spertus JA, McLeod HL. Connexin37 (GJA4) genotype predicts survival after an acute coronary syndrome. Am Heart J. 2007;154:561–566. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.04.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Listi F, Candore G, Balistreri CR, Caruso M, Incalcaterra E, Hoffmann E, Lio D, Caruso C. Connexin37 1019 gene polymorphism in myocardial infarction patients and centenarians. Atherosclerosis. 2007;191:460–461. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Listi F, Candore G, Lio D, Russo M, Colonna-Romano G, Caruso M, Hoffmann E, Caruso C. Association between C1019T polymorphism of connexin37 and acute myocardial infarction: a study in patients from Sicily. Int J Cardiol. 2005;102:269–271. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2004.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yamada Y, Izawa H, Ichihara S, Takatsu F, Ishihara H, Hirayama H, Sone T, Tanaka M, Yokota M. Prediction of the risk of myocardial infarction from polymorphisms in candidate genes. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1916–1923. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hubacek JA, Stanek V, Gebauerova M, Pilipcincova A, Poledne R, Aschermann M, Skalicka H, Matouskova J, Kruger A, Penicka M, et al. Lack of an association between connexin-37, stromelysin-1, plasminogen activator-inhibitor type 1 and lymphotoxin-alpha genes and acute coronary syndrome in Czech Caucasians. Exp Clin Cardiol. 2010;15:e52–e56. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leu HB, Chung CM, Chuang SY, Bai CH, Chen JR, Chen JW, Pan WH. Genetic variants of connexin37 are associated with carotid intima-medial thickness and future onset of ischemic stroke. Atherosclerosis. 2011;214:101–106. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Collings A, Islam MS, Juonala M, Rontu R, Kahonen M, Hutri-Kahonen N, Laitinen T, Marniemi J, Viikari JS, Raitakari OT, Lehtimaki TJ. Associations between connexin37 gene polymorphism and markers of subclinical atherosclerosis: the cardiovascular risk in Young Finns study. Atherosclerosis. 2007;195:379–384. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pitha J, Hubacek JA, Cifkova R, Skodova Z, Stavek P, Lanska V, Kovar J, Poledne R. The association between subclinical atherosclerosis in carotid arteries and Connexin 37 gene polymorphism (1019C>T; Pro319Ser) in women. Int Angiol. 2011;30:221–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Juo SH, Liao YC, Lin HF, Chen PL, Lin WY, Lin RT. Lack of association between a functional genetic variant of connexin 37 and ischemic stroke in a Taiwanese population. Thromb Res. 2012;129:e65–e69. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2011.12.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zheng L, Sun Z, Li J, Zhang R, Zhang X, Liu S, Li J, Xu C, Hu D, Sun Y. Pulse pressure and mean arterial pressure in relation to ischemic stroke among patients with uncontrolled hypertension in rural areas of China. Stroke. 2008;39:1932–1937. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.510677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shi Y, Li Z, Xu Q, Wang T, Li T, Shen J, Zhang F, Chen J, Zhou G, Ji W, et al. Common variants on 8p12 and 1q24.2 confer risk of schizophrenia. Nat Genet. 2011;43:1224–1227. doi: 10.1038/ng.980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thomas G, Sinville R, Sutton S, Farquar H, Hammer RP, Soper SA, Cheng YW, Barany F. Capillary and microelectrophoretic separations of ligase detection reaction products produced from low-abundant point mutations in genomic DNA. Electrophoresis. 2004;25:1668–1677. doi: 10.1002/elps.200405886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yi P, Chen Z, Zhao Y, Guo J, Fu H, Zhou Y, Yu L, Li L. PCR/LDR/capillary electrophoresis for detection of single-nucleotide differences between fetal and maternal DNA in maternal plasma. Prenat Diagn. 2009;29:217–222. doi: 10.1002/pd.2072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goldstein LB, Bushnell CD, Adams RJ, Appel LJ, Braun LT, Chaturvedi S, Creager MA, Culebras A, Eckel RH, Hart RG, et al. Guidelines for the primary prevention of stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2011;42:517–584. doi: 10.1161/STR.0b013e3181fcb238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O'Donnell MJ, Xavier D, Liu L, Zhang H, Chin SL, Rao-Melacini P, Rangarajan S, Islam S, Pais P, McQueen MJ, et al. Risk factors for ischaemic and intracerebral haemorrhagic stroke in 22 countries (the INTERSTROKE study): a case-control study. Lancet. 2010;376:112–123. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60834-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ross R. Cell biology of atherosclerosis. Annu Rev Physiol. 1995;57:791–804. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.57.030195.004043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kwak BR, Mulhaupt F, Veillard N, Gros DB, Mach F. Altered pattern of vascular connexin expression in atherosclerotic plaques. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002;22:225–230. doi: 10.1161/hq0102.104125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wong CW, Christen T, Roth I, Chadjichristos CE, Derouette JP, Foglia BF, Chanson M, Goodenough DA, Kwak BR. Connexin37 protects against atherosclerosis by regulating monocyte adhesion. Nat Med. 2006;12:950–954. doi: 10.1038/nm1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dupont WD, Plummer WD., Jr Power and sample size calculations for studies involving linear regression. Control Clin Trials. 1998;19:589–601. doi: 10.1016/S0197-2456(98)00037-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article.