Abstract

The yeast Metschnikowia fructicola was reported as an efficient biological control agent of postharvest diseases of fruits and vegetables, and it is the bases of the commercial formulated product “Shemer.” Several mechanisms of action by which M. fructicola inhibits postharvest pathogens were suggested including iron-binding compounds, induction of defense signaling genes, production of fungal cell wall degrading enzymes and relatively high amounts of superoxide anions. We assembled the whole genome sequence of two strains of M. fructicola using PacBio and Illumina shotgun sequencing technologies. Using the PacBio, a high-quality draft genome consisting of 93 contigs, with an estimated genome size of approximately 26 Mb, was obtained. Comparative analysis of M. fructicola proteins with the other three available closely related genomes revealed a shared core of homologous proteins coded by 5,776 genes. Comparing the genomes of the two M. fructicola strains using a SNP calling approach resulted in the identification of 564,302 homologous SNPs with 2,004 predicted high impact mutations. The size of the genome is exceptionally high when compared with those of available closely related organisms, and the high rate of homology among M. fructicola genes points toward a recent whole-genome duplication event as the cause of this large genome. Based on the assembled genome, sequences were annotated with a gene description and gene ontology (GO term) and clustered in functional groups. Analysis of CAZymes family genes revealed 1,145 putative genes, and transcriptomic analysis of CAZyme expression levels in M. fructicola during its interaction with either grapefruit peel tissue or Penicillium digitatum revealed a high level of CAZyme gene expression when the yeast was placed in wounded fruit tissue.

Keywords: postharvest pathology, biocontrol agent, fungi, genome assembly, genome annotation, plant pathogen interactions

Introduction

The yeast Metschnikowia fructicola (type strain NRRL Y-27328, CBS 8853) was first isolated from grapes and identified as a new species by Kurtzman and Droby (2001). The identification was achieved by comparing its nucleotide sequence in the species-specific ca. 500–600-nucleotide D1/D2 domain of 26S ribosomal DNA (rDNA) with a database of D1/D2 sequences from all the recognized ascomycetous yeasts available at that time (Kurtzman and Robnett, 1998), and subsequent entries in GenBank.

Yeasts have been identified by many workers as potential biological control agents suitable for the prevention of postharvest diseases, especially since they are naturally occurring on fruits and vegetables, and exhibit a number of traits that favor their use as fungal antagonists. These traits include high tolerance to environmental stresses (low and high temperatures, desiccation, wide fluctuations in relative humidity, low oxygen levels, pH fluctuations, UV radiation) encountered during fruit and vegetable production before and after harvest, and their ability to adapt to the micro-environment present in wounded fruit tissues, characterized by high sugar concentration, high osmotic pressure, low pH and conditions that conducive to oxidative stress. These traits are especially beneficial for their use as biocontrol agents, since the majority of postharvest decay pathogens are necrotrophic and infect fruit through wounded tissues (Droby et al., 2016; Wisniewski et al., 2016). Additionally, many yeast species can grow rapidly on inexpensive substrates in fermenters, traits that are conducive to their large-scale commercial production and use (Spadaro and Droby, 2016). Moreover, in contrast to filamentous fungi, the vast majority of naturally occurring yeasts do not produce allergenic spores or mycotoxins, and have simple nutritional requirements that enable them to colonize dry surfaces for long periods of time (Spadaro et al., 2008).

Significant progress has been made in the development, registration and commercialization of postharvest biocontrol products (Droby et al., 2009, 2016) and a variety of different biocontrol agents have reached advanced stages of development and commercialization. “Shemer,” based on the yeast M. fructicola (Droby et al., 2009), is one of the commercial products that has reached the market.

Several studies have documented the biocontrol efficacy of M. fructicola and its ability to prevent or limit the infection of harvested products by postharvest pathogens (Karabulut et al., 2003, 2004; Spadaro et al., 2013). Similar to other postharvest biocontrol agents, M. fructicola exhibits several modes of action to achieve its ability to act as an antagonist. Like its sister species M. pulcherrima, M. fructicola produces the red pigment, pulcherrimin, which is formed non-enzymatically from pulcherriminic acid and ferric ions (Sipiczki, 2006). Pulcherrimin has been reported to play a role in the control of Botrytis cinerea, Alternaria alternata, and Penicillium expansum on apple (Saravanakumar et al., 2008). Enhanced expression of several genes involved in defense signaling, including PRP genes and MAPK cascade genes was demonstrated in grapefruit when surface wounds were treated with M. fructicola cells (Hershkovitz et al., 2012). The enhanced gene expression was consistent with an induced resistance response suggesting that induced host resistance plays a role in the biocontrol of M. fructicola against postharvest pathogens such as P. digitatum (Hershkovitz et al., 2012). M. fructicola also exhibits chitinase activity and the chitinase gene, MfChi, was demonstrated to be highly induced in yeast cells when cell walls of Monilinia fructicola, the causal agent of brown rot in stone fruit, was added to the growth medium. These data suggest that MfChi may also play a role in the biocontrol activity exhibited by Metschnikowia species (Banani et al., 2015). Macarisin et al. (2010) demonstrated that yeast antagonists, including M. fructicola, used to control postharvest diseases have the ability to produce relatively high amounts of superoxide anions. They also demonstrated that yeast cells applied to surface wounds of fruits produce greater levels of superoxide anions than yeast grown in vitro in artificial media.

Several studies have examined differential gene expression during the interaction of the yeast M. fructicola with host fruit tissue or with the mycelium of the postharvest pathogen P. digitatum (Hershkovitz et al., 2012, 2013). Due to the lack of an assembled genome sequence, de-novo assembly of the transcriptome of M. fructicola was performed, which resulted in the identification of 9,674 unigenes, half of which could be annotated based on homology to genes in the NCBI database (Hershkovitz et al., 2013). Approximately, 69% of the unigene sequences identified in M. fructicola showed high homology to genes of the yeast Clavispora lusitaniae. Thus, the RNA-Seq-based transcriptome analysis generated a large number of newly identified M. fructicola yeast genes and significantly increased the number of sequences available for Metschnikowia species in the NCBI database. Shotgun sequencing data enabled to construct a draft genome of M. fructicola based on Illumina paired-end assembly with ∼7000 contigs that was submitted to Genbank (Hershkovitz et al., 2013).

Details about the structure and annotation of the genomes of yeast biocontrol agents are lacking. Such information would be a valuable tool for analyzing the sequences of putative “biocontrol-related” genes among different species of yeast biocontrol agents, characterizing gene clusters with known and unknown functions, as well as studying global changes in gene transcription rather than just specific, targeted genes. Obtaining full genome sequences would also allow comparative genomic analyses to be conducted among closely related yeast species that do not exhibit antagonist properties (Massart et al., 2015).

In the present study, a whole genome sequence of the 277 type-strain of M. fructicola (NRRL Y-27328) was assembled using PacBio technology. Results indicate that the genome of M. fructicola (Mf genome) is approximately 26 Mbp and contains 8,629 gene coding sequences. The new assembly resulted in a high quality assembly consisting of 93 contigs – the longest one is 2,548,689 bp – with 439X average genome coverage.

In parallel, the genome of another biocontrol strain of M. fructicola (strain AP47) isolated in northern Italy from apple fruit surfaces and used to control brown rot of peaches (Zhang et al., 2010), was assembled by aligning Illumina shotgun sequences (with a genome coverage of 161.8 X), using the genome assembly of the strain 277 as a reference. The mutation rate between the two biocontrol strains of M. fructicola was also determined.

Results and Discussion

Assembly, Gene Prediction and Functional Annotation of the Genome of Metschnikowia fructicola Strain 277

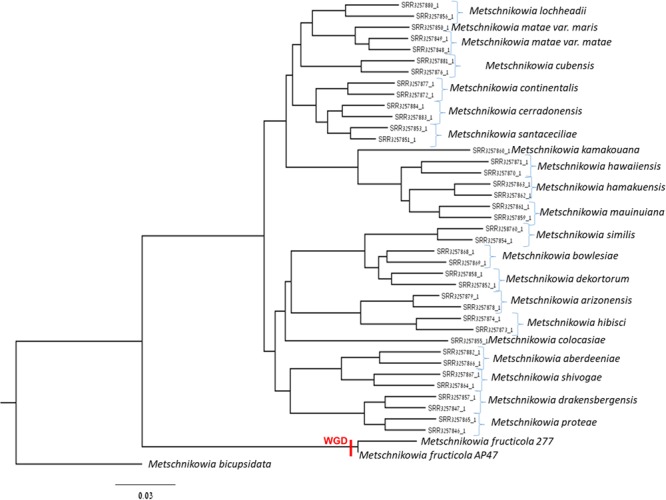

A new assembly of the M. fructicola (type strain NRRL Y-27328, CBS 8853) genome (Genbank accession ANFW02000000) was constructed using sequence data obtained from the Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) RS II Sequencer. The PacBio genomic sequences were assembled with the HGAP3.0 program (Chin et al., 2013) and yielded a high-quality draft genome consisting of 93 contigs with an N50 of 957,836 bp. The estimated genome size is approximately 26 Mb. Total of 8,629 genes were predicted with MAKER, and 6,262 were successfully annotated with Blast2GO (Conesa et al., 2005) and InterProScan (Finn et al., 2016a,b). The results of assembly, gene prediction and annotation are presented in Table 1. In contrast to the previous assembly (Hershkovitz et al., 2013), where 9,674 transcripts were identified, the current high-quality assembly provided a more accurate estimate of the transcript number (8,629) and size of the M. fructicola genome. We believe that the current number is more accurate because it was estimated by using the MAKER gene predictor (Cantarel et al., 2008), trained with the transcript sequences obtained by mapping the RNA reads obtained by Hershkovitz et al. (2013) on a high-quality genomic sequence. On the other hand, the 9,674 predicted by Hershkovitz et al. (2013) were obtained by de novo assembly with the Trinity software (Grabherr et al., 2011), which can be prone to the overestimation of the number of transcripts (Cerveau and Jackson, 2016). The annotated transcripts are listed in Supplementary Table S1, and their sequences, CDSs and protein sequences are presented in Supplementary Data Sheets S1–S3. Supplementary Data Sheet S4 contains the gene coordinates. The main characteristics of the current M. fructicola genome assembly and a comparison to the previous assembly (Hershkovitz et al., 2013) are summarized in Table 1. Comparative analysis of M. fructicola proteins with the other three available closely related genomes of Clavispora lusitaniae, Candida auris, and M. bicupsidata revealed a shared core of homologous proteins coded by 5,776 genes (Supplementary Data Sheet S5). A recently published work describing the phylogeny of strains belonging to Metschnikowia species isolated from the guts of flower-visiting insects (Lachance et al., 2016) allowed us to construct a phylogenetic tree of Metschnikowia spp that is based on the fastq raw-data deposited in Genbank (Figure 1). The tree was constructed using an assembly and alignment-free method of phylogeny reconstruction (Fan et al., 2015). Interestingly, the phylogenetic analysis showed that the two M. fructicola strains described in our study were grouped together and were separate from other Metschnikowia species described by Lachance et al. (2016). This difference in phylogeny may be related to evolutionary history and niche colonization of fruit surfaces versus insect guts.

Table 1.

Summary of the main assembly and annotation features of the genome of the sequenced Metschnikowia fructicola strain 277.

| New sequence | Old sequence (Hershkovitz et al., 2013) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sequencing technology | PacBio | Illumina |

| Genome size | ∼26 Mb | ∼23 Mb |

| Sequencing coverage | 20X | 700X |

| Number of contigs | 93 | 8430 |

| Number of large contigs (>100 Kb) | 84 | 2 |

| N50 (base pairs) | 957,836 bp | 3,784 bp |

| GC content (%) | 45.8% | 45.5% |

| N50 of transcript length (nucleotides) | 5033bp | 589bp |

| Number of genes | 8,629 | 15,803 |

| Annotated genes | 6,277 | – |

FIGURE 1.

Phylogenetic tree comprised of Metschnikowia fructicola 277, Metschnikowia fructicola AP47, and other Metchnikowia species. The tree was constructed using an assembly and alignment-free method of phylogeny reconstruction (Fan et al., 2015). The whole genome duplication event was indicated on the tree with “WGD.”

The GO analysis revealed that 6,262 of the 8,629 identified M. fructicola genes were characterized with 4,493 GO terms (Supplementary Data Sheet S6). The most common descriptors concerning the cellular component were “Cell” and “Cell Part,” followed by “Organelle,” while “Cellular process” and “Metabolic Process,” followed by “Localization,” “Establishment of Localization,” “Biological Regulation,” “Pigmentation” and “Response to stimulus” were the most common in the biological processes. Regarding the molecular function, the most common descriptors were “Binding” and “Catalytic,” followed by “Transporter.” The same descriptors in the three categories were the most common in the genes characterized in the paper of Hershkovitz et al. (2013).

Utilization of M. fructicola 277 Genome for Reference-Based Assembly of Strain AP47

The assembly of the genome of strain 277 presented here is the most comprehensive and complete assembly for M. fructicola to date. This assembly was used as a reference to assemble the genome of the AP47 strain of M. fructicola, obtained by Illumina MySeq (161.8 X) shotgun sequencing data (Table 2). The reference guided assembly resulted in an N50 of 957,045, which was much higher than the one obtained by de novo assembly (Table 3). The length of the AP47 genome was similar to the reference strain 277 (∼26 Mb), but had a slightly higher GC content (46.3% compared to 45.8%).

Table 2.

Sequencing data of the two pair end libraries used to sequence the genome of Metschnikowia fructicola, strain AP47.

| Sequencing data | Library PE1 | Library PE2 | Library MP1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of raw reads | 3717646 | 2599548 | 10188012 |

| Number of clean reads | 2545140 | 2546666 | 9126542 |

| Total length (Mb) | 301.257 | 927.79 | 2977.528 |

| GC percentage | 43% GC | 45% GC | 43% GC |

Table 3.

De novo and reference guided assemblies of the genome of the sequenced Metschnikowia fructicola, strain AP47.

| De novo assembly∗ | Reference guided assembly∗∗ | |

|---|---|---|

| Sequence length | ∼23.3 Mb | ∼26.2 Mb |

| Number of scaffolds | 10,173 | 93 |

| Number of scaffolds > 100 Kb | 35 | 53 |

| Number of scaffolds > 1 Kb | 3156 | 93 |

| N50 (base pairs) | 63,477 bp | 957,045 bp |

| G + C content (%) | 46.3% | 46.3% |

∗Obtained with SPAdes (Bankevich et al., 2012). ∗∗Obtained with IMR-DENOM (http://mtweb.cs.ucl.ac.uk/mus/www/19genomes/IMR-DENOM/).

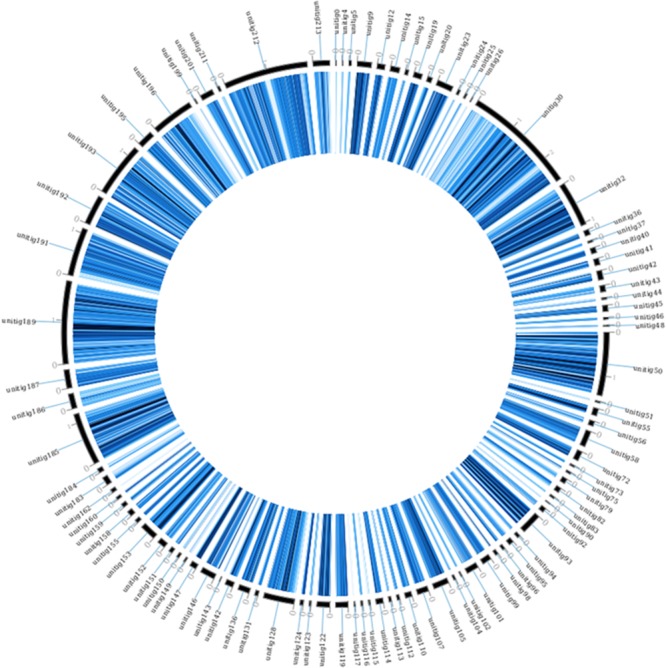

The assembly presented here was also compared to the AP47 strain assembly using a SNP calling approach. Results of this analysis are presented in Table 4, and the complete vcf is found in Supplementary Data Sheet S7. Considering only homozygous polymorphisms, a total of 546,356 SNPs, 11,987 insertions and 5,959 deletions were identified. Among these mutations, 185,649 were in coding regions, and the vast majority of the variations (135,616) were silent. However, 50,822 were missense mutations, and 212 were nonsense mutations. The differences with strain AP47 were mapped on strain 277 and presented in Figure 2.

Table 4.

Number of mutations in the genome sequence of M. fructicola strain AP47, compared to the reference genome of M. fructicola strain 277, and their predicted effect and impact on coding sequences.

| Number of mutations | 564,302 |

|---|---|

| SNPs | 546,356 |

| Insertions | 11,987 |

| Deletions | 5,959 |

| Variant rate | 1 variant every 46 bases |

| Predicted mutation effect | |

| Silent | 135,884 |

| Missense | 49,794 |

| Nonsense | 212 |

| Mutation impact | |

| High | 2,023 (0.08%) |

| Moderate | 50,032 (1.97%) |

| Low | 136,810 (5.39%) |

| Negligible | 2,348,195 (92.56%) |

FIGURE 2.

Homologous SNPs of M. fructicola strain AP47, mapped on the strain 277 genome. The figure was obtained using circoVCF tool (Drori et al., 2017).

The average mutation rate was one every 46 bases, which is exceptionally high in respect to the average reported for other yeast species. For example, the average mutation rate is approximately one SNP every 235 and 269 nucleotides, in C. albicans (Hirakawa et al., 2015) and Saccharomyces cerevisiae, respectively (Drozdova et al., 2016). The high number of observed mutations may be related to the different geographical origin and host species of the strains. The 277 type-strain of M. fructicola (NRRL Y-27328) was isolated in Israel from the surface of grapes, while the AP47 strain was isolated in Italy from the surface of apples.

The strain AP47 Whole Genome Shotgun project has been deposited at DDBJ/ENA/GenBank under the accession MTJM00000000. The version described in this paper is version MTJM01000000.

The D1/D2 region ribosomal region was identified in strain 277 genome by blasting M. pulcherrima D1/D2 region on it. Since we observed that none of the identified SNPs were localized in that region, we can confirm with high confidence that both strains 277 and strain AP47 belong to the same species, which is different from M. pulcherrima (Kurtzman and Robnett, 1998).

Stress-induced genomic instability has been studied in various yeast and bacteria, under a variety of stress conditions. Stresses were suggested to induce several genetic changes including small changes (one to few nucleotides), deletions and insertions, gross chromosomal rearrangements, copy-number variations and movement of mobile elements (Galhardo et al., 2007).

We suggest that M. fructicola as a species could undergo genomic changes in order to survive environmental stresses, in particular on the fruit surface. These changes may have led to evolve mechanisms not only to tolerate stresses, but also to generate large-scale genetic variation as a means of adaptation, giving both M. fructicola strains the genetic traits to be successful plant surface colonizers (intact and wounded surfaces) and, possibly, antagonists of fruit pathogens. A second reason of the high polymorphism-rate between M. fructicola strains may be the high-mutation rate in the promoters of genes putatively involved in the repair or mutation of the genomic sequences. A list of GO terms related to these processes (Supplementary Data Sheet S8) was used to identify 272 annotated genes, and in their promoter sequences the variant rate was of 1/35 bases, against the average of 1/40 in the promoters of the rest of the genomes. The variant rate in the actual transcribed sequence was, however, in line with the rest of the genome (1/66 against 1/67 bases). We also calculated the percentage of these genes showing a putative high impact polymorphism, and 21% of them (57 out of 272) did: this number was slightly higher than the percentage of total genes showing a similar polymorphism (16%, 1,379 out of 8,629).

Uncommonly Large Genome

The genome of M. fructicola was surprisingly large in size, being 26 Mb long. In fact, the most closely related available genomes (M. bicuspidata, C. auris and C. lusitaniae), are 16 Mb (BioProject PRJNA207846, Riley et al., 2016), 12.5 Mb (BioProjects PRJNA342691 and PRJNA267757, Chatterjee et al., 2015) and 11.9 Mb (BioProject PRJNA12753, Butler et al., 2009), respectively. The most probable explanation for such a genome size seemed to be a whole genome duplication event. To have evidence of this, we searched the genome for homologs, finding 5,132 genes out of 8,629, all in pairs but for 228, which come in groups of three or more copies. This is a high degree of homology, since in the genomes of M. bicuspidata, C. auris, and C. lusitaniae we found only 71, 69, and 56 homologous genes, respectively.

Ordinarily, after a whole-genome duplication event in yeasts, most of the duplicates of genes situated in low mutation regions are lost, while the ones situated in rapidly evolving regions accumulate mutations and differentiate themselves from their homologs (Fares et al., 2017). We compared the average number of polymorphisms identified between strains 277 and AP47 on homologous and single-copy genes, finding that the first group of genes has a variant rate of 1/65 bases, while for the second group this value is of 1/68. Since divergence between gene copies can also happen at the expression level, so that each copy can be expressed in a different situation and accumulate mutations useful for a specific environmental condition (Fares et al., 2017), the variant rate in the promoters was also checked. Among the promoters of the homologous genes, the average variant rate is of 1/37 bases, while in the single-copy gene promoters it is of 1/45.

Despite the low difference in the mutation rate of single-copy and homologous genes, particularly in the proper gene sequence and not in the promoters, we believe that the available data strengthen the hypothesis of a whole-genome duplication event being responsible for the large genome of M. fructicola. This is due principally to the fact that nearly all the homologous genes come in pairs, with only 228 having more than one homolog. The sequencing of other M. fructicola strains will undoubtedly be critical to gain further insight on the reasons of this yeast’s large genome.

It should be noted that the strain AP47 has SNPs spread along all the contigs of strain 277 (Figure 2). This seems to indicate that the whole genome duplication event occurred in AP47 as well, and that the strains share a common ancestor. This was observed despite the high mutation rate between the strains.

The genomes of the Metschnikowia spp. present in Table 5 were downloaded from ncbi, to look for others whole-genome duplication events. Since M. bicuspidata is the only one of these species to have been fully annotated, it was impossible to look for the whole genome duplication event as has been done with M. fructicola. Therefore, we blasted both the transcriptomes of M. fructicola and M. bicuspidata on all the considered genomes, counting how many of these had matches on different contigs: even if not every transcript had a match, the result of the analysis gave us an idea of the level of homology inside the genomes of interest. In M. fructicola, 75% of the transcripts had matches on more than one contig. Furthermore, of the M. bicuspidata transcripts with a match on the M. fructicola genome, 58% had a match on more than one contig. On the contrary, none of the other analyzed genomes reached a percentage of transcripts mapping on different contigs of 10%. Based on this data, it seems that the whole-genome duplication event is unique to M. fructicola. This data correlates well with the high homology level found in the genome, because a high number of homologous genes is commonly associated with relatively recent whole genome duplication events (Lenassi et al., 2013).

Table 5.

Homology level in different Metschnikowia spp. genomes.

| Matched transcripts |

Homology level |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M. fructicola transcriptome | M. bicuspidata transcriptome | M. fructicola transcriptome | M. bicuspidata transcriptome | |

| M. aberdeeniae (GCA_002370615.1) | 39.16% | 38.89% | 3.64% | 4.93% |

| M. arizonensis (GCA_002370875.1) | 33.97% | 33.3% | 4.74% | 7.15% |

| M. bicuspidata (PRJNA207846) | 67.96% | 100% | 3.27% | 9.23% |

| M. bowlesiae (GCA_002370295.1) | 36.77% | 38.02% | 5.55% | 7.26% |

| M. cerradonensis (GCA_002370635.1) | 37.66% | 38.51% | 6.98% | 8.1% |

| M. colocasiae (GCA_002370175.1) | 39.89% | 41.32% | 4.71% | 6.55% |

| M. continentalis (GCA_002370835.1) | 37.46% | 38.05% | 8.42% | 9.37% |

| M. cubensis (GCA_002374405.1) | 38.3% | 38.98% | 6.51% | 8.53% |

| M. dekortorum (GCA_002374455.1) | 36.46% | 38% | 5.02% | 6.99% |

| M. drakensbergensis (GCA_002370475.1) | 39.02% | 40.16% | 4.1% | 5.25% |

| M. fructicola | 100% | 66.52% | 74.13% | 58.23% |

| M. hawaiiensis (GCA_002370325.1) | 40.06% | 40.74% | 7.52% | 9.71% |

| M. hibisci (GCA_002374725.1) | 31.71% | 29.57% | 3.4% | 5.91% |

| M. kamakouana (GCA_002374535.1) | 38.86% | 39.3% | 3.67% | 5.58% |

| M. lochheadii (GCA_002370915.1) | 36.49% | 36.3% | 7.21% | 9.44% |

| M. matae (GCA_002370695.1) | 35.07% | 35.12% | 7.93% | 9.56% |

| M. mauinuiana (GCA_002374555.1) | 38.63% | 39.59% | 7.47% | 9.04% |

| M. proteae (GCA_002370515.1) | 39.65% | 40.57% | 3.98% | 5.83% |

| M. santaceciliae (GCA_002374485.1) | 38.08% | 38.74% | 6.57% | 8.4% |

| M. shivogae (GCA_002374645.1) | 39.85% | 40.19% | 3.63% | 5.33% |

| M. similis (GCA_002370765.1) | 36.93% | 38.15% | 5.3% | 7.5% |

The table is divided in two sections. The left section (Matched transcripts) shows the percentage of M. fructicola or M. bicuspidata transcripts having a match when blasted on the genome of various Metschnikowia spp. The homology level on the right section shows the percentage of matched transcripts which also have a second match on another contig.

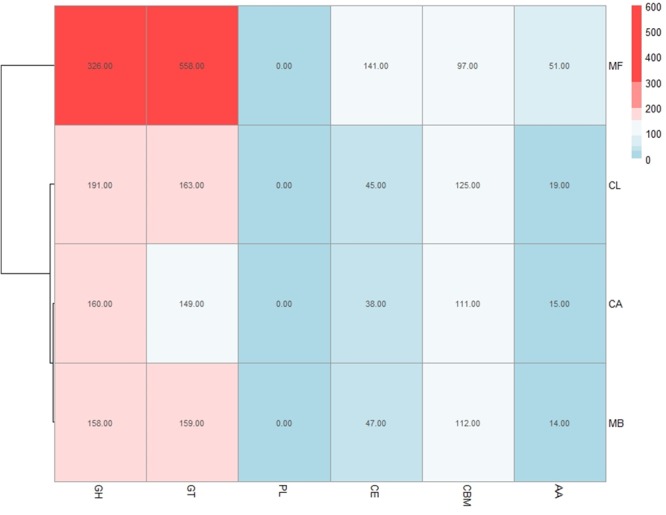

Carbohydrate Active Enzymes

Plant cell walls consist of a complex network of carbohydrate components, including cellulose, hemicellulose and pectin, as well as a variety of proteins and glycoproteins. These polysaccharides, and other analogous microbial related structural compounds, are targets of carbohydrate-active enzymes (CAZymes) that cleave them into oligomers and simple monomers, which can then be used as nutrients by microorganisms (Cantarel et al., 2009). Bacteria and fungi that are associated with and interact with plants have evolved carbohydrate enzymes strongly linked to the plant environment that these microbes inhabit (Kolton et al., 2013). M. fructicola strain 277 MAKER predicted proteins were analyzed with CAT (Park et al., 2010) showing 1,145 putative CAZymes in M. fructicola (Figure 3). This represents one of the largest number of potential CAZyme genes that have been reported in Ascomycetes (Amselem et al., 2011). In comparison, the genomes of Botrytis cinerea and Sclerotinia sclerotiorum, two versatile necrotrophic plant pathogens, contain 367 and 346 putative CAZyme genes, respectively, including 106 and 118 clearly related to cell wall degradation (Apweiler et al., 2001). The impressive repertoire of CAZymes in M. fructicola thus may play an important role in its nutritional status and ability to colonize plant surfaces as well as being an effective biocontrol control agent. This role becomes particularly important giving that injured fruit surfaces contain a wide variety of simple and complex carbohydrates that can be consumed by pathogens. Despite different studies characterizing the action of some of these genes (Jijakli and Lepoivre, 1998; Friel et al., 2007), the prospective role of CAZymes in the mechanism of action of microbial antagonists is yet to be fully explored. Among the identified CAZymes in M. fructicola, 463 have clear assignments to either glycoside hydrolases (GH) or carbohydrate esterases (CE), all involved in fungal cell wall degradation. Two of the aforementioned genes, unitig185_25 and unitig50_23, have a strong resemblance to MfChi (Genbank accession number: HQ113461.1), a M. fructicola chitinase which was shown to inhibit Monilinia fructicola and M. laxa in vitro and on fruit (Banani et al., 2015). A comparison of the number of CAZymes in each of the four annotated genomes belonging to the Metschnikowiaceae family (Mf – Metschnikowia fructicola, Mb – Metschnikowia bicuspidata, CL – Clavispora lusitaniae, and CA – Candida auris) was conducted (Figure 3). Mb is a fresh-water fish pathogen, while CL and CA are both human pathogens. Results indicated that the M. fructicola genome contained a significantly greater variation and number of CAZyme genes, including glycoside hydrolase (GH), glycosyl transferases (GT) and carbohydrate-binding modules (CBM) family genes (Figure 3 and Supplementary Table S2). The Mf genome contained several unique CAZymes involved in the metabolism of glucans, arabinose, and rhamnogalacturonan that are exclusively associated with terrestrial plant hemicellulose.

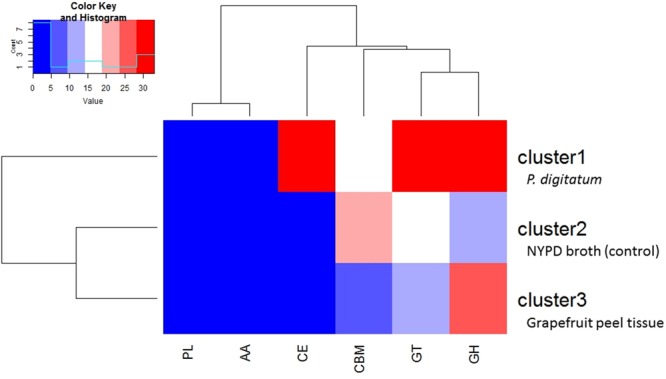

FIGURE 3.

The number of CAZYenzyme genes in each of the 4 sequenced genomes belonging to the Metschnikowiaceae family: Mf – Metschnikowia fructicola, Mb – Metschnikowia bicuspidate, CL – Clavispora lusitaniae, and CA – Candida auris. Different classes of CAZYenzyme genes are designated as GH –Glycoside Hydrolases; GT – Glycosyl Transferases; PL – Polysaccharide Lyases; CE – Carbohydrate Esterases; CBM – Carbohydrate-Binding Modules and AA – Auxiliary Activities. The color reflects the relative number of genes in each of the four species as indicated by the scale in the upper right portion of the figure. 28 genes were included in 2 categories, and therefore the sum of the total of Figure 3 for M. fructicola is slightly more than 1,145, which is the reported number of CAZymes.

M. fructicola Response to P. digitatum and to Grapefruit Peel Tissue

The current assembly and genome annotation of Mf enabled us to examine the identification of genes associated with the interaction of Mf with either P. digitatum or grapefruit peel tissue and determine the genes that are specific to each interaction.

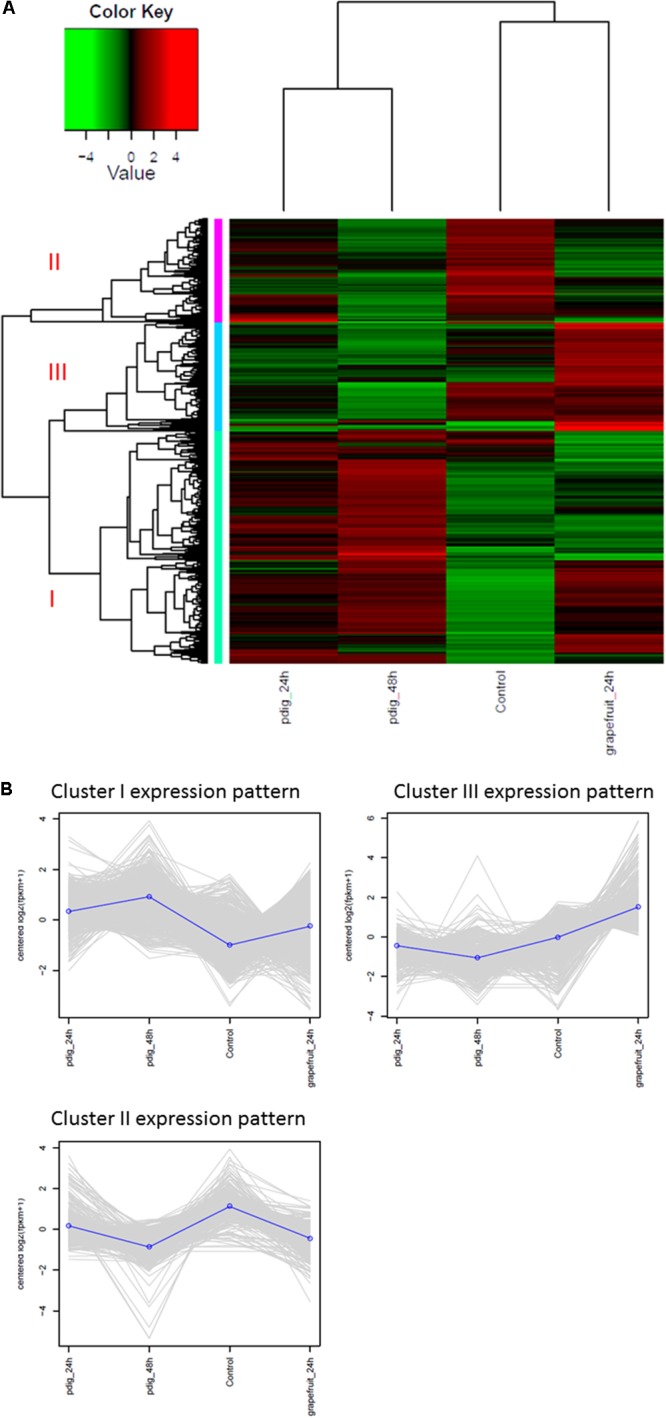

The transcriptomic RNAseq libraries of Mf, available from BioProject PRJNA168317 (Hershkovitz et al., 2013), were then analyzed. These libraries were constructed from Mf under four different conditions: (1) Mf growing in NYPD broth (control), (2) Mf in contact with P. digitatum (Pd) mycelium for 24 h, (3) Mf in contact with P. digitatum (Pd) mycelium for 48 h, and (4) Mf in contact with grapefruit peel for 24 h.

The analysis of DEGs indicated that gene expression in Mf cells that were in contact with fruit peel tissue or had no contact with fruit tissue (control), was more similar to each other than to gene expression in Mf cells that were in contact with P. digitatum mycelia. In total, 2,588 DEGs were identified among Mf cells in contact or not in contact with citrus fruit, peel tissue, and Mf cells that were in contact with P. digitatum mycelium (Supplementary Table S3). The DEGs could be grouped into three different co-expressed clusters (Figures 4A,B).

FIGURE 4.

(A) Heatmap and expression profile of differentially expressed genes in Metschnikowia fructicola (Mf) grown on different substrates. Three clusters were identified. Cluster 1 – genes with higher expression level when Mf was grown in contact with Penicillium digitatum (Pd). Cluster2 – genes with higher expression level when Mf was grown in NYPD broth (control). Cluster 3 - genes with higher expression level when in Mf was grown in contact with grapefruit peel. (B) The expression profile of the three clusters in response to the different growth conditions.

Cluster1 genes were more highly expressed during contact with P. digitatum (Pd) mycelia, relative to cells grown in NYPD broth (control) or on grapefruit peel tissue. We have found 1353 such genes (while only 153 unigenes were found in the previous analysis when using de-novo transcriptome assembly). Cluster 2 genes were more highly expressed in Mf grown in NYPD broth (control) than they were when Mf was in contact with either grapefruit peel tissue or P. digitatum mycelium (total of 635 genes). Cluster 3 genes exhibited higher levels of expression when Mf cells were in contact with grapefruit peel tissue, rather than when grown in NYPD broth (control) or in contact with P. digitatum mycelium (600 genes).

Transcriptomic analysis of CAZyme expression levels in M. fructicola during its interaction with grapefruit peel tissue or P. digitatum mycelium when cultured in a PDB medium revealed a high level of CAZyme gene expression when the yeast was placed in wounded fruit tissue (Figure 5). These results suggest that CAZyme genes may play an important role in the adaptation of M. fructicola to a fruit environment.

FIGURE 5.

Diagram showing the relative number of genes within each class of CAZymesin each cluster. Cluster1 genes were more highly expressed, relative to cells grown in NYPD broth (control) or on grapefruit peel tissue, when the yeast cells were in contact with Penicillium digitatum (Pd) mycelium. Cluster 2 genes were more highly expressed in Mf grown in NYPD broth (control). Cluster 3 genes exhibited higher levels of expression when Mf cells were grown in contact with grapefruit peel tissue. Cluster 3 show also the highest quantity of CAZY enzymes. The color reflects the relative number of genes in each of the clusters as indicated by the scale in the upper left portion of the figure. Different classes of CAZYenzyme genes are designated as GH –Glycoside Hydrolases; GT – Glycosyl Transferases; PL – Polysaccharide Lyases; CE – Carbohydrate Esterases; CBM – Carbohydrate-Binding Modules and AA – Auxiliary Activities.

Secondary Metabolite Clusters Present in M. fructicola

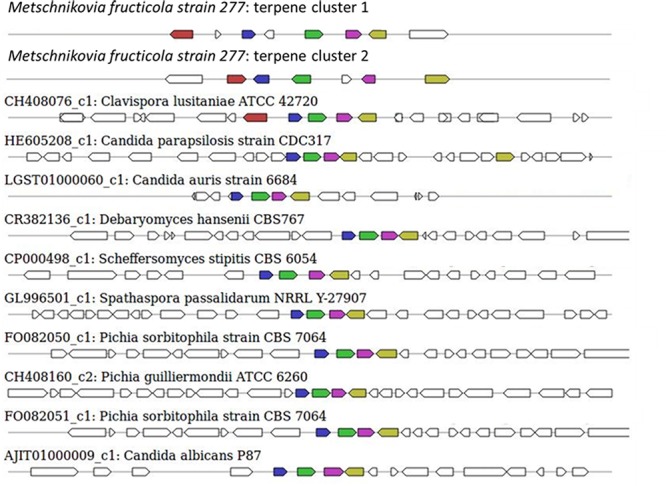

The sequence of the M. fructicola genome revealed that this yeast possesses several secondary metabolite (SM) genes. SMs are known to play an important role in the virulence of many plant pathogens (Namdeo, 2007), but limited knowledge is available about the SM repertoire present in M. fructicola. Using antiSMASH (Weber et al., 2015) software, the M. fructicola genome was analyzed for the presence of secondary metabolite clusters or homologs of these genes present in related fungi. Twenty-six SM gene clusters were identified in M. fructicola, four of which are highly conserved in yeast and other fungi. The remaining 22 clusters could only be designated as putative clusters as similar clusters could not be identified in other fungal genomes using the ClusterFinder algorithm (Cimermancic et al., 2014). These 22 potential clusters included putative saccharide and fatty acid biosynthetic clusters. The analysis of secondary metabolite genes indicated that M. fructicola is capable of producing small, potentially bioactive molecules. Two of the identified clusters (Figure 6 and Table 6) code for the production of a terpene that is conserved within Candida species. Terpenoid compounds are known to play a significant role in yeast antimicrobial defense mechanism (Hyldgaard et al., 2012). The isoprenoid backbones of these compounds are synthesized by terpene synthases (TSs). The classification of various terpene synthases and their catalytic mechanisms have been recently reviewed (Gao et al., 2012). Although terpenoid SMs have not been previously reported in M. fructicola, the genome sequence clearly possesses two gene sequences that encode squalene/phytoene synthases: the transcripts unitig50_211 and unitig147_7.

FIGURE 6.

Secondary metabolite clusters producing terpene and their homology with terpene-synthesis clusters in closely related fungi. The terpene synthesis clusters as indicated by antiSMASH3.0 software. The uppermost clusters represent the terpene-synthesis clusters in M. fructicola while the terpene-synthesis cluster from other yeasts are shown below.

Table 6.

Secondary metabolites clusters identified with antiSMASH (Weber et al., 2015) software.

| Secondary metabolite cluster type | Transcripts of Mf found in cluster | Location |

|---|---|---|

| Terpene cluster | unitig147_4 | unitig147 |

| unitig147_5 | 15287 – 36642 | |

| unitig147_6 | ||

| unitig147_7 | ||

| unitig147_8 | ||

| unitig147_9 | ||

| unitig147_10 | ||

| Terpene cluster | unitig50_207 | unitig50 |

| unitig50_208 | 578895 – 600250 | |

| unitig50_209 | ||

| unitig50_210 | ||

| unitig50_211 | ||

| unitig50_212 | ||

| unitig50_213 | ||

| unitig50_214 |

YAP Gene Expression in M. fructicola

The Yap protein family plays a role in cellular response to oxidative stress (Rodrigues-Pousada et al., 2010) and M. fructicola has been demonstrated to have a high tolerance to oxidative stress (Macarisin et al., 2010). An analysis of YAP genes in the M. fructicola genome revealed the presence of 14 YAP genes (Table 7). In comparison, 7 YAP genes were found in C. albicans (BioProjects PRJNA14005 and PRJNA10701), C. auris (BioProjects PRJNA342691 and PRJNA267757) and M. bicuspidata (BioProject PRJNA207846), while C. lusitaniae (BioProject PRJNA12753) had 6. YAP genes are important for resistant to oxidative stress (Macarisin et al., 2010). a feature that could possibly play a role in the ecological fitness and antagonistic activity of M. fructicola.

Table 7.

Yap family genes and homologs identified in the genome of M. fructicola.

| Systematic name Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Homologue in Mf genome | Gene name | Alias(es) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| YDR259C | Not found | YAP6 | HAL7 | Basic leucine zipper (bZIP) transcription factor |

| YDR423C | Not found | CAD1 | YAP2 | AP-1-like basic leucine zipper (bZIP) transcriptional activator |

| YGR241C | unitig192_208 | YAP1802 | Protein of the AP180 family, involved in clathrin cage assembly | |

| YHL009C | unitig142_42 | YAP3 | Basic leucine zipper (bZIP) transcription factor | |

| unitig187_66 | ||||

| YHR161C | Not found | YAP1801 | Protein of the AP180 family, involved in clathrin cage assembly | |

| YIR018W | Not found | YAP5 | Basic leucine zipper (bZIP) iron-sensing transcription factor | |

| YJR005W | unitig146_71 | APL1 | YAP80 | Beta-adaptin |

| unitig192_37 | ||||

| YJR058C | unitig122_58 | APS2 | YAP17 | Small subunit of the clathrin-associated adaptor complex AP-2 |

| unitig50_345 | ||||

| YLR120C | unitig104_2 | YPS1 | aspartyl protease, | Aspartic protease |

| unitig150_6 | ||||

| unitig193_349 unitig32_12 |

||||

| YLR170C | unitig196_234 | APS1 | YAP19 | Small subunit of the clathrin-associated adaptor complex AP-1 |

| YML007W | Not found | YAP1 | PDR4, DNA-binding transcription factor YAP1, SNQ3, PAR1 | Basic leucine zipper (bZIP) transcription factor |

| YOL028C | Not found | YAP7 | Putative basic leucine zipper (bZIP) transcription factor | |

| YOR028C | Not found | CIN5 | YAP4, HAL6 | Basic leucine zipper (bZIP) transcription factor of the yAP-1 family |

| YPL259C | unitig105_13 | APM1 | YAP54 | Mu1-like medium subunit of the AP-1 complex |

| unitig193_251 | ||||

| YPR199C | Not found | ARR1 | ACR1, YAP8 | Transcriptional activator of the basic leucine zipper (bZIP) family |

Pulcherrimin Cluster Analysis

Pulcherrimin is a M. fructicola metabolite of major interest, since it is involved in the biocontrol action of this yeast (Saravanakumar et al., 2008) and of other biocontrol yeast strains (Castoria et al., 2003). The genes responsible for the biosynthesis of this siderophore were successfully identified only in B. subtilis (Randazzo et al., 2016), and an analysis of orthology with proteinortho and blast showed no homology between the B. subtilis pulcherrimin gene cluster and the proteins predicted in M. fructicola. It is probable that the B. subtilis and M. fructicola genes involved in pulcherrimin biosynthesis are the product of different evolutionary processes.

Conclusion

The genomes of two strains of M. fructicola (277 and AP47) were sequenced, assembled and compared. The comparison of the two genomes sequences indicated a very high rate of mutation, even though it will be necessary to sequence additional strains to establish if the average mutation rate in M. fructicola is intrinsically high, or if the mutation rate identified in the present study is related to the geographical origin and fruit host in which they evolved. The genome size (∼26 Mb) of both M. fructicola strains, as well as the rate of mutation, may suggest that M. fructicola could undergo genomic changes in order to adapt to plant surfaces, tolerate various environmental stresses and survive under restricted nutritional resources. Its adaptation to plant environment can also be explained by the presence of a relatively large number of secondary metabolites clusters, YAP and CAZymes related genes in the genome.

Another interesting result was the discovery of 1,145 putative CAZymes in the M. fructicola genome. These genes could be the target of studies aimed to identify enzymes able to control fungal diseases in vivo, to evaluate their potential use as treatments for fruits and plants.

Materials and Methods

DNA Extraction

Metschnikowia fructicola, Strain 277, (Kurtzman and Droby, 2001) was grown in NYDP (nutrient broth (8 g l-1), yeast extract (5 g l-1), D-glucose (10 g l-1) and chloramphenicol (250 mg l-1). One ml of the yeast cell suspension was aseptically transferred from 24 h old starter culture to 250 ml Erlenmeyer flasks and place on an orbital shaker at 160 rpm for 24 h at 26°C. Yeast cells were pelleted by centrifugation at 6,000 rpm, washed twice with sterile distilled water, re-suspended in sterile water to initial volume and the cell suspension concentration was adjusted to 1 × 108 cells ml-1.

Metschnikowia fructicola strain AP47 was isolated from the carposphere of an apple grown in Piedmont, Northern Italy (Zhang et al., 2010). The strain was stored in tubes of Potato Dextrose Agar and 50 mg/L streptomycin at 4°C. Suspensions of M. fructicola AP47 (5 × 105 cells/mL) were inoculated in 500 mL Potato Dextrose Broth (PDB, Difco) and incubated on a rotary shaker (180 rpm) at 24°C for 4 days. Yeast mass was filtered from the culture, frozen in liquid nitrogen and DNA was extracted from 1 g frozen tissue. The final DNA preparation was incubated overnight at room temperature in 490 μl of Tris-EDTA (TE) buffer and 10 μl of DNase-free RNase (10 μg/ml), followed by phenol-chloroform extraction and isopropanol precipitation. Finally, DNA was resuspended in 30 μl TE buffer. DNA concentration and purity were checked by a spectrophotometer (Nanodrop 2000, Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE, United States), and the DNA integrity was analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis (data not shown).

Sequencing

Strain 277 was sequenced on the Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) RS II Sequencer, as previously described (Hoffmann et al., 2013; Pirone-Davies et al., 2015). Specifically, we prepared the library using 10 μg of genomic DNA, that was sheared to a size of 20 kb fragments by g-tubes (Covaris, Inc., Woburn, MA, United States) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. The SMRTbell 20-kb template library was constructed using DNA Template Prep Kit 1.0 with the 20-kb insert library protocol (Pacific Biosciences; Menlo Park, CA, United States). Size selection was performed with BluePippin (Sage Science, Beverly, MA, United States). The library was sequenced using the P6/C4 chemistry on 24 single-molecule real-time (SMRT) cells (8 with BluePippin and 16 without), with a 240-min collection protocol along with stage start.

The genome of M. fructicola AP47 was sequenced at the Genomics Platform of the Parco Tecnologico Padano using the Illumina MiSeq technology. Two paired-ends were prepared using Nextera XT DNA Sample Preparation Kit, following the manufacturer’s instructions. Two paired-end (PE) libraries were prepared: PE1 with overlapping paired-end reads and PE2 with non-overlapping paired-end reads. One mate pair library was also prepared, using Nextera Mate Pair Sample Preparation Kit and following the manufacturer’s instructions. Libraries were purified by AMPure XP beads and normalized to ensure equal library representation in the pools. Equal volumes of libraries were diluted in the hybridization buffer, heat denatured and sequenced. Standard phi X control library (Illumina) was spiked into the denatured HCT 116 library. The libraries and phi X mixture were finally loaded into a MiSeq 250 and MiSeq 300-Cycle v2 Reagent Kit (Illumina). Base calling was performed using the Illumina pipeline software. PE1 was composed of 2,1 Gb (330 mean insert size, 43% GC, 35% duplication level). PE2 was composed of 846 Mb (132 mean insert size, 45% GC, 12/duplication level).

All the paired end sequences were trimmed with Trimmomatic v. 0.36 (Bolger et al., 2014) and cleaned with sickle v. 1.33 (Joshi and Fass, 2011) (Table 2). The mate pair sequences were trimmed and cleaned with TrimGalore v. 0.4.21.

The genome of M. fructicola AP47 was assembled at first with a de novo approach, using SPAdes (Bankevich et al., 2012), and then with a reference guided approach using IMR-DENOM2, with the strain 277 as the reference.

Assembly

Analysis of the sequence reads was implemented by using SMRT Analysis 2.3.0. The best de novo assembly was established with the PacBio Hierarchical Genome Assembly Process HGAP3.0 program (Chin et al., 2013) using the continuous-long-reads from the four SMRT cells, which contained the longest subreads, with a minimum subread length cutoff of 5000 kb and target coverage of 20X. The resulting HGAP unique contigs (unitigs) were blasted against each other to identify smaller unitigs that show complete overlapping with other larger unitigs. These smaller unitigs were removed from the analysis. Afterward the improved consensus sequence was uploaded in SMRT Analysis 2.3.0. and polished with Quiver using all 24 SMRT cells (Chin et al., 2013).

In total 24 SMRT cells were used, resulting in 93 contigs with 439X average genome coverage. The longest contig comprised 2,548,689 bp.

Transcriptome Assembly, Gene Prediction and Functional Annotation

RNAseq from previous analysis (Hershkovitz et al., 2013) was used to assemble and predict transcribed regions in the Mf genome. Overall, 6,150 transcripts were identified based on tophat, cufflinks and bowtie2 pipeline as described in (Langmead and Salzberg, 2012).

The transcriptome data, together with the transcripts and proteins sequences available on NCBI for M. fructicola, M. biscuspidata, C. auris and C. lusitaniae, were used to train the gene predictor SNAP3, following the suggested procedure4. The augustus gene predictor5 was trained with the WebAUGUSTUS web service (Stanke and Morgenstern, 2005), using as data the sequence of the 6,150 transcripts identified with the RNA seq.

SNAP and augustus were then used as a part of the MAKER software (Cantarel et al., 2008) to conduct the gene prediction in the genome. The evidence used were the 6,150 transcripts discovered with the RNA seq and the transcripts and proteins sequences available on NCBI for M. fructicola, M. biscuspidata, C. auris and C. lusitaniae. The transcripts not coming from M. fructicola were included in the MAKER control files as “altest” evidence, which is specifically used for data from species related to the target genome and not from the target itself. The repeat library was constructed following the Basic protocol6, and MAKER was launched using the option “correct_est_fusion” in the control files and “-fix-nucleotides” in the command line. MAKER produced a gene coordinates gff3 file, which was used to extract the CDSs from the genome in order to translate them with BioPython (Cock et al., 2009) using the Alternative Yeast Nuclear Code, obtaining the protein sequences. Some of the predicted genes had putative CDSs, which did not start with a start codon and/or did not end with a stop one, and were therefore discarded, with the following exceptions: (i) genes missing the stop codon, localized on the plus filament, which were the last gene of their contig; (ii) genes missing the stop codon, localized on the minus filament, which were the first gene of their contig; (iii) genes missing the start codon, localized on the plus filament, which were the first gene of their contig; (iv) genes missing the start codon, localized on the minus filament, which were the last gene of their contig. The genes of these categories were kept as partial genes.

The proteins were annotated with Blast2GO and Interproscan, using as blast database the fungal fraction of uniprot and swissprot databases (UniProt Consortium, 2017).

The CAT webservice was used to find Pfam modules (Finn et al., 2016b) in the proteins and assign them CAZy families.

Proteinortho v. 5.16 was used to look for homologous proteins in the proteomes of M. fructicola 277, C. auris (BioProjects PRJNA342691 and PRJNA267757), M. bicuspidata (BioProject PRJNA207846) and C. lusitaniae (BioProject PRJNA12753).

Gene Expression Analysis

RNAseq analysis was done using RNAseq data from previous research (Hershkovitz et al., 2013). The RNAseq data number SRA054245 was download from SRA database in NCBI. The RNAseq data was mapped using bowtie (Langmead et al., 2009). Expression quantification was estimated using RSEM software (Li and Dewey, 2011). Differential expression analysis was done using edgeR Bioconductor package (Robinson et al., 2010). Clustering was done using K-mean cluster analysis (Basu et al., 2002) differentialy expressed genes threshold was FDR < 0.05 (Benjamini and Hochberg, 1995) and log fold changes greater than 1 or smaller than -1.

Phylogenetic Tree

All raw-data sequences of Metschnikowia species (Lachance et al., 2016) were downloaded from NCBI using SRAtoolkit (Leinonen et al., 2011) from BioProject ID PRJNA312754. The phylogenetic tree was constructed with an assembly and alignment-free method of phylogeny reconstruction from next-generation sequencing data (Fan et al., 2015).

To place the whole-genome duplication event in the three, we downloaded the genomes of all the considered species, and we used them as databases to blast the full transcriptomes of M. fructicola and M. bicuspidata (Table 5), using blastall v. 2.2.26 with default parameters. We then calculated the percentage of transcripts having a match, and, inside this fraction, the percentage of transcripts having a match on at least 2 contigs.

Genome Comparison With M. fructicola Strain AP47

A SNP calling approach was followed, using bwa mem (Li and Durbin, 2009) to map Illumina reads of the strain AP47 of M. fructicola on the assembly of the strain 277. After using samtools view and samtools sort (Li et al., 2009) to obtain a sort.bam file, the following pipeline was used as described by Li (2011) for the SNP calling:

samtools mpileup -guf reference.fa AP47.sort.bam | bcftools view -cg -| vcfutils.pl varFilter -D 200 -Q 20 - > file.vcf

The file AP47.sort.bam was obtained by merging the data from the two Illumina libraries with samtools merge.

The genome of the strain 277 and the gff3 and protein fasta files obtained with MAKER, were used to build a SnpEff (Cingolani et al., 2012) database, and the tool “snpeff eff” was used to evaluate the effect of the homozygous SNPs of the strain AP47. Since M. fructicola is a haploid organism, heterozygous SNPs were probably mistakes. The Alternative Yeast Nuclear Code was used to evaluate the effect of missense SNPs on protein sequences.

Analysis of the Polymorphisms-Related Genes

The variant rate of the genes characterized by gene onthology terms present in Supplementary Data Sheet S8 was calculated, and the same was done with their promoters. Supplementary Data Sheet S8 was obtained by selecting all GO terms including the word “repair” or “mutation,” and then removing manually undesired terms (es: “cell wall repair).

The promoter analysis was performed considering as promoter the 1000 bases preceding the genes in the genome, or the 1000 bases following the genes when these were on the antisense strand.

Analysis of the D1/D2 Region

The primers NL-1 (GCATATCAATAAGCGGAGGAAAAG) and NL-4 (GGTCCGTGTTTCAAGACGG) (O’Donnell, 1993), used by Kurtzman and Robnett (1998) to amplify the D1/D2 region in S. cerevisiae, were blasted on the M. pulcherrima sequences available on NCBI, so to identify the D1/D2 region. The partial sequence of the large subunit ribosomal RNA gene of M. pulcherrima culture-collection CBS:2256 (GenBank: KY108498.1) was therefore downloaded, and blasted on the M. fructicola strain 277 genome. We then proceeded to identify the SNPs present in that region in the strains 277 and AP47, looking at both the homozygous and heterozygous SNPs. The blast version used was blastall v. 2.2.26.

Whole-Genome Duplication Hypothesis

Proteinortho v. 5.16 was used to look for homologous proteins in the proteomes of M. fructicola 277, C. auris (BioProjects PRJNA342691 and PRJNA267757), M. bicuspidata (BioProject PRJNA207846) and C. lusitaniae (BioProject PRJNA12753). The variant rate in single-copy and homologous genes was calculated, and the same was done in their promoters.

The promoter analysis was performed considering as promoter the 1000 bases preceding the genes in the genome, or the 1000 bases following the genes when these were on the antisense strand.

YAP Genes Analysis

The protein sequence of various Yap genes was downloaded from www.yeastgenome.org, and analyzed with Proteinortho v. 5.16 (Lechner et al., 2011), looking for homologs in the proteins predicted for M. fructicola strain 277 and in the proteomes of Candida albicans (BioProjects PRJNA14005 and PRJNA10701), C. auris (BioProjects PRJNA342691 and PRJNA267757), M. bicuspidata (BioProject PRJNA207846) and C. lusitaniae (BioProject PRJNA12753).

Secondary Metabolites Cluster Prediction

Secondary metebolites clustering was predicted using antiSMASH website (Weber et al., 2015).

Pulcherrimin Gene Cluster Analysis

The proteins involved in pulcherrimin biosynthesis in B. subtilis (YVNB, YVNA, YVMC, YVMB, YVMA, CYPX; Randazzo et al., 2016) were downloaded from NCBI and used in a proteinortho v. 5.15 analysis with the MAKER predicted proteins of M. fructicola, with default parameters. The B. subtilis genes of interest were also blasted with blastp (blastall v. 2.2.26) against the predicted proteome of M. fructicola, using an e-value threshold of 10-5.

Author Contributions

EP and NS performed the bioinformatics analyses and contributed to writing the manuscript. MH and MA performed the PacBio sequencing and contigs assembly. EL contributed in DNA extraction and preparation samples for sequencing. MW, MG, DS, and SD designed the study and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Work carried out with a contribution of the LIFE Financial Instrument of the European Union for the Project “Low pesticide IPM in sustainable and safe fruit production” (Contract No. LIFE13 ENV/HR/000580). The authors wish to thank Prof. Alberto Acquadro, University of Torino for his useful suggestion about bioinformatics analysis.

Footnotes

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2018.00593/full#supplementary-material

Fasta file of transcripts of MF.

Fasta file of CDSs of MF.

Fasta file of proteins of MF.

Gff file of MF.

Proteinortho analysis of M. fructicola, M. bicuspidata, C. auris and C. lusitaniae.

Annotation file of MF, produced by Blast2GO.

Vcf file, obtained by mapping the M. fructicola strain AP47 reads on the genome of strain 277.

List of GO terms related to the mutation or repair of the DNA sequence.

Annotation of Mf transcripts.

CAZymes predicted in the M. fructicola 277 genome.

fpkm expression data and statistical differences among conditions analyzed with RNAseq.

References

- Amselem J., Cuomo C. A., van Kan J. A., Viaud M., Benito E. P., Couloux A., et al. (2011). Genomic analysis of the necrotrophic fungal pathogens Sclerotinia sclerotiorum and Botrytis cinerea. PLoS Genet. 7:e1002230. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apweiler R., Attwood T. K., Bairoch A., Bateman A., Birney E., Biswas M., et al. (2001). The InterPro database, an integrated documentation resource for protein families, domains and functional sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 29 37–40. 10.1093/nar/29.1.37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banani H., Spadaro D., Zhang D., Matic S., Garibaldi A., Gullino M. L. (2015). Postharvest application of a novel chitinase cloned from Metschnikowia fructicola and overexpressed in Pichia pastoris to control brown rot of peaches. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 199 54–61. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2015.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bankevich A., Nurk S., Antipov D., Gurevich A. A., Dvorkin M., Kulikov A. S., et al. (2012). SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J. Comput. Biol. 19 455–477. 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu S., Banerjee A., Mooney R. J. (2002). “Semi-supervised clustering by seeding,” in Proceedings of 19th International Conference on Machine Learning Stroudsburg, PA: 19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y., Hochberg Y. (1995). Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. B 57 289–300. 10.2307/2346101 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger A. M., Lohse M., Usadel B. (2014). Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30 2114–2120. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler G., Rasmussen M. D., Lin M. F., Santos M. A., Sakthikumar S., Munro C. A., et al. (2009). Evolution of pathogenicity and sexual reproduction in eight Candida genomes. Nature 459 657–662. 10.1038/nature08064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantarel B. L., Coutinho P. M., Rancurel C., Bernard T., Lombard V., Henrissat B. (2009). The carbohydrate-active EnZymes database (CAZy): an expert resource for glycogenomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 37 233–238. 10.1093/nar/gkn663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantarel B. L., Korf I., Robb S. M., Parra G., Ross E., Moore B., et al. (2008). MAKER: an easy-to-use annotation pipeline designed for emerging model organism genomes. Genome Res. 18 188–196. 10.1101/gr.6743907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castoria R., Caputo L., De Curtis F., De Cicco V. (2003). Resistance of postharvest biocontrol yeasts to oxidative stress: a possible new mechanism of action. Phytopathology 93 564–572. 10.1094/PHYTO.2003.93.5.564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerveau N., Jackson D. J. (2016). Combining independent de novo assemblies optimizes the coding transcriptome for nonconventional model eukaryotic organisms. BMC Bioinformatics 17:525. 10.1186/s12859-016-1406-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee S., Alampalli S. V., Nageshan R. K., Chettiar S. T., Joshi S., Tatu U. S. (2015). Draft genome of a commonly misdiagnosed multidrug resistant pathogen Candida auris. BMC Genomics 16 686. 10.1186/s12864-015-1863-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin C. S., Alexander D. H., Marks P., Klammer A. A., Drake J., Heiner C., et al. (2013). Nonhybrid, finished microbial genome assemblies from long-read SMRT sequencing data. Nat. Methods 10 563–569. 10.1038/nmeth.2474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cimermancic P., Medema M. H., Claesen J., Kurita K., Brown L. C. W., Mavrommatis K., et al. (2014). Insights into secondary metabolism from a global analysis of prokaryotic biosynthetic gene clusters. Cell 158 412–421. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.06.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cingolani P., Platts A., Wang L. L., Coon M., Nguyen T., Wang L., et al. (2012). A program for annotating and predicting the effects of single nucleotide polymorphisms, SnpEff: SNPs in the genome of Drosophila melanogaster strain w1118. Fly 6 80–92. 10.4161/fly.19695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cock P. J., Antao T., Chang J. T., Chapman B. A., Cox C. J., Dalke A., et al. (2009). Biopython: freely available Python tools for computational molecular biology and bioinformatics. Bioinformatics 25 1422–1423. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conesa A., Götz S., García-Gómez J. M., Terol J., Talón M., Robles M. (2005). Blast2GO: a universal tool for annotation, visualization and analysis in functional genomics research. Bioinformatics 21 3674–3676. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Droby S., Wisniewski M., Macarisin D., Wilson C. (2009). Twenty years of postharvest biocontrol research: is it time for a new paradigm? Postharvest Biol. Technol. 52 137–145. 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2008.11.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Droby S., Wisniewski M., Teixidó N., Spadaro D., Jijakli M. H. (2016). The science, development, and commercialization of postharvest biocontrol products. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 122 22–29. 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2016.04.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Drori E., Levy D., Smirin-Yosef P., Rahimi O., Salmon-Divon M. (2017). CircosVCF: circos visualization of whole-genome sequence variations stored in VCF files. Bioinformatics 33 1392–1393. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drozdova P. B., Tarasov O. V., Matveenko A. G., Radchenko E. A., Sopova J. V., Polev D. E., et al. (2016). Genome sequencing and comparative analysis of Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains of the peterhof genetic collection. PLoS One 11:e0154722. 10.1371/journal.pone.0154722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan H., Ives A. R., Surget-Groba Y., Cannon C. H. (2015). An assembly and alignment-free method of phylogeny reconstruction from next-generation sequencing data. BMC Genomics 16:522. 10.1186/s12864-015-1647-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fares M. A., Sabater-Muñoz B., Toft C. (2017). Genome mutational and transcriptional hotspots are traps for duplicated genes and sources of adaptations. Genome Biol. Evol. 9 1229–1240. 10.1093/gbe/evx085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn R. D., Attwood T. K., Babbitt P. C., Bateman A., Bork P., Bridge A. J., et al. (2016a). InterPro in 2017—beyond protein family and domain annotations. Nucleic Acids Res. 45 190–199. 10.1093/nar/gkw1107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn R. D., Coggill P., Eberhardt R. Y., Eddy S. R., Mistry J., Mitchell A. L., et al. (2016b). The Pfam protein families database: towards a more sustainable future. Nucleic Acids Res. 44 D279–D285. 10.1093/nar/gkv1344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friel D., Pessoa N. M. G., Vandenbol M., Jijakli M. H. (2007). Separate and combined disruptions of two exo-beta-1,3-glucanase genes decrease the efficiency of Pichia anomala (strain K) biocontrol against Botrytis cinerea on apple. Mol. Plant Microbe Int. 20 371–379. 10.1094/MPMI-20-4-0371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galhardo R. S., Hastings P. J., Rosenberg S. M. (2007). Mutation as a stress response and the regulation of evolvability. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. 42 399–435. 10.1080/10409230701648502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y., Honzatko R. B., Peters R. J. (2012). Terpenoid synthase structures: a so far incomplete view of complex catalysis. Nat. Prod. Rep. 29 1153–1175. 10.1039/c2np20059g [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabherr M. G., Haas B. J., Yassour M., Levin J. Z., Thompson D. A., Amit I., et al. (2011). Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat. Biotechnol. 29 644–652. 10.1038/nbt.1883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershkovitz V., Ben-Dayan C., Raphael G., Pasmanik-Chor M., Liu J., Belausov E., et al. (2012). Global changes in gene expression of grapefruit peel tissue in response to the yeast biocontrol agent Metschnikowia fructicola. Mol. Plant Pathol. 13 338–349. 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2011.00750.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershkovitz V., Sela N., Taha-Salaime L., Liu J., Rafael G., Kessler C., et al. (2013). De-novo assembly and characterization of the transcriptome of Metschnikowia fructicola reveals differences in gene expression following interaction with Penicillium digitatum and grapefruit peel. BMC Genomics 14:168. 10.1186/1471-2164-14-168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirakawa M. P., Martinez D. A., Sakthikumar S., Anderson M. Z., Berlin A., Gujja S., et al. (2015). Genetic and phenotypic intra-species variation in Candida albicans. Genome Res. 25 413–425. 10.1101/gr.174623.114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann M., Muruvanda T., Allard M. W., Korlach J., Roberts R. J., Timme R., et al. (2013). Complete genome sequence of a multidrug-resistant Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium var. 5- strain isolated from chicken breast. Genome Announc. 1:e1068-e13 10.1128/genomeA.01068-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyldgaard M., Mygind T., Meyer R. L. (2012). Essential oils in food preservation: mode of action, synergies, and interactions with food matrix components. Front. Microbiol. 25 3–12. 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jijakli M. H., Lepoivre P. (1998). Characterization of an exo-beta-1,3-glucanase produced by Pichia anomala strain K, antagonist of Botrytis cinerea on apples. Phytopathology 88 335–343. 10.1094/PHYTO.1998.88.4.335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi N., Fass J. (2011). Sickle: A Sliding-Window, Adaptive, Quality-Based Trimming Tool for FastQ Files. Available at: github com/najoshi/sickle [Google Scholar]

- Karabulut O., Tezcan H., Daus A., Cohen L., Wiess B., Droby S. (2004). Control of preharvest and postharvest fruit rot in strawberry by Metschnikowia fructicola. Biocontrol. Sci. Technol. 14 513–521. 10.1080/09583150410001682287 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karabulut O. A., Smilanick J. L., Gabler F. M., Mansour M., Droby S. (2003). Near-harvest applications of Metschnikowia fructicola, ethanol, and sodium bicarbonate to control postharvest diseases of grape in central California. Plant Dis. 87 1384–1389. 10.1094/PDIS.2003.87.11.1384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolton M., Sela N., Elad Y., Cytryn E. (2013). Comparative genomic analysis indicates that niche adaptation of terrestrial Flavobacteria is strongly linked to plant glycan metabolism. PLoS One 8:e76704. 10.1371/journal.pone.0076704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtzman C. P., Droby S. (2001). Metschnikowia fructicola, a new ascosporic yeast with potential for biocontrol of postharvest fruit rots. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 24 395–399. 10.1371/journal.pone.0076704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtzman C. P., Robnett C. J. (1998). Identification and phylogeny of ascomycetous yeasts from analysis of nuclear large subunit (26S). ribosomal DNA partial sequences. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 73 331–371. 10.1023/A:1001761008817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachance M. A., Hurtado E., Hsiang T. (2016). A stable phylogeny of the large-spored Metschnikowia clade. Yeast 33 261–275. 10.1002/yea.3163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B., Salzberg S. L. (2012). Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 9 357–359. 10.1038/nmeth.1923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B., Trapnell C., Pop M., Salzberg S. L. (2009). Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol. 10:R25. 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lechner M., Findeiß S., Steiner L., Marz M., Stadler P. F., Prohaska S. J. (2011). Proteinortho: detection of (Co-) orthologs in large-scale analysis. BMC Bioinformatics 12:124. 10.1186/1471-2105-12-124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leinonen R., Sugawara H., Shumway M. (2011). The sequence read archive. Nucleic Acids Res. 39(Database issue) D19–D21. 10.1093/nar/gkq1019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenassi M., Gostinèar C., Jackman S., Turk M., Sadowski I., Nislow C., et al. (2013). Whole genome duplication and enrichment of metal cation transporters revealed by de novo genome sequencing of extremely halotolerant black yeast Hortaea werneckii. PLoS One 8:e71328. 10.1371/journal.pone.0071328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B., Dewey C. N. (2011). RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinformatics 12:323. 10.1186/1471-2105-12-323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H. (2011). A statistical framework for SNP calling, mutation discovery, association mapping and population genetical parameter estimation from sequencing data. Bioinformatics 27 2987–2993. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Durbin R. (2009). Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows–Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25 1754–1760. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Handsaker B., Wysoker A., Fennell T., Ruan J., Homer N., et al. (2009). The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25 2078–2079. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macarisin D., Droby S., Bauchan G., Wisniewski M. (2010). Superoxide anion and hydrogen peroxide in the yeast antagonist–fruit interaction: A new role for reactive oxygen species in postharvest biocontrol? Postharvest Biol. Technol. 58 194–202. 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2010.07.008 22017757 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Massart S., Perazzolli M., Höfte M., Pertot I., Jijakli M. H. (2015). Impact of the omic technologies for understanding the modes of action of Biological Control agents against plant pathogens. BIOCONTROL 60 725–746. 10.1007/s10526-015-9686-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Namdeo A. (2007). Plant cell elicitation for production of secondary metabolites: a review. Pharmacogn. Rev. 1 69–79. [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell K. (1993). “Fusarium and its near relatives,” in The Fungal Holomorph: Mitotic, Meiotic and Pleomorphic Speciation in Fungal Systematics eds Reynolds D. R., Taylor J. W. (Wallingford, CT: CAB International; ) 225–233. [Google Scholar]

- Park B. H., Karpinets T. V., Syed M. H., Leuze M. R., Uberbacher E. C. (2010). CAZymes Analysis Toolkit (CAT): web service for searching and analyzing carbohydrate-active enzymes in a newly sequenced organism using CAZy database. Glycobiology 20 1574–1584. 10.1093/glycob/cwq106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirone-Davies C., Hoffmann M., Roberts R. J., Muruvanda T., Timme R. E., Strain E., et al. (2015). Genome-wide methylation patterns in Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovars. PLoS One 10:e0123639. 10.1371/journal.pone.0123639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randazzo P., Aubert-Frambourg A., Guillot A., Auger S. (2016). The MarR-like protein PchR (YvmB) regulates expression of genes involved in pulcherriminic acid biosynthesis and in the initiation of sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. BMC Microbiol. 16:190. 10.1186/s12866-016-0807-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley R., Haridas S., Wolfe K. H., Lopes M. R., Hittinger C. T., Göker M., et al. (2016). Comparative genomics of biotechnologically important yeasts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113 9882–9887. 10.1073/pnas.1603941113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson M. D., McCarthy D. J., Smyth G. K. (2010). edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 26 139–140. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues-Pousada C., Menezes R. A., Pimentel C. (2010). The Yap family and its role in stress response. Yeast 27 245–258. 10.1002/yea.1752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saravanakumar D., Ciavorella A., Spadaro D., Garibaldi A., Gullino M. L. (2008). Metschnikowia pulcherrima strain MACH1 outcompetes Botrytis cinerea, Alternaria alternata and Penicillium expansum in apples through iron depletion. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 49 121–128. 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2007.11.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sipiczki M. (2006). Metschnikowia strains isolated from botrytized grapes antagonize fungal and bacterial growth by iron depletion. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72 6716–6724. 10.1128/AEM.01275-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spadaro D., Droby S. (2016). Development of biocontrol products for postharvest diseases of fruit: the importance of elucidating the mechanisms of action of yeast antagonists. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 47 39–49. 10.1016/j.tifs.2015.11.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spadaro D., Lorè A., Garibaldi A., Gullino M. L. (2013). A new strain of Metschnikowia fructicola for postharvest control of Penicillium expansum and patulin accumulation on four cultivars of apple. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 75 1–8. 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2012.08.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spadaro D., Sabetta W., Acquadro A., Portis E., Garibaldi A., Gullino M. L. (2008). Use of AFLP for differentiation of Metschnikowia pulcherrima strains for postharvest disease biological control. Microbiol. Res. 163 523–530. 10.1016/j.micres.2007.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanke M., Morgenstern B. (2005). AUGUSTUS: a web server for gene prediction in eukaryotes that allows user-defined constraints. Nucleic Acids Res. 33 465–467. 10.1093/nar/gki458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UniProt Consortium (2017). UniProt: the universal protein knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Res. 45 158–169. 10.1093/nar/gkw1099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber T., Blin K., Duddela S., Krug D., Kim H. U., Bruccoleri R., et al. (2015). antiSMASH 3.0—a comprehensive resource for the genome mining of biosynthetic gene clusters. Nucleic Acids Res. 43 237–243. 10.1093/nar/gkv437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisniewski M., Droby S., Norelli J., Liu J., Schena L. (2016). Alternative management technologies for postharvest disease control: the journey from simplicity to complexity. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 122 3–10. 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2016.05.012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D., Spadaro D., Garibaldi A., Gullino M. L. (2010). Selection and evaluation of new antagonists for their efficacy against postharvest brown rot of peaches. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 55 174–181. 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2009.09.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fasta file of transcripts of MF.

Fasta file of CDSs of MF.

Fasta file of proteins of MF.

Gff file of MF.

Proteinortho analysis of M. fructicola, M. bicuspidata, C. auris and C. lusitaniae.

Annotation file of MF, produced by Blast2GO.

Vcf file, obtained by mapping the M. fructicola strain AP47 reads on the genome of strain 277.

List of GO terms related to the mutation or repair of the DNA sequence.

Annotation of Mf transcripts.

CAZymes predicted in the M. fructicola 277 genome.

fpkm expression data and statistical differences among conditions analyzed with RNAseq.