Abstract

INTRODUCTION:

Radical surgical treatment is the preferred action for patients with early-stage non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Qualification for surgical treatment should consider a risk associated with the effect of comorbidities on the general condition of the patient. The aim of this article was an attempt to identify the risk factors for postoperative complications in patients treated for NSCLC, with a special focus on the coexisting diseases.

METHODS:

A total of 400 patients with NSCLC were included in this retrospective study. The incidence of postoperative complications (including major complications according to the European Society of Thoracic Surgeons [ESTS]) was analyzed. Factors associated with high risk of postoperative complications were identified.

RESULTS:

Postoperative complications occurred in 151 patients (39% operated patients), including severe complications according to ESTS in 75 patients (19%). From univariate analysis, risk factors for postoperative complications were arrhythmias, pneumonectomy, and open thoracotomy. According to ESTS, for major complications, the risk factors included age ≥65 years, the presence of comorbidities, hypertension, and arrhythmias. From multivariate analysis, the risk of complications was higher in patients undergoing pneumonectomy and with cardiac arrhythmias, whereas the risk of serious complications according to ESTS was found in people ≥65 years of age and suffering from comorbidities.

CONCLUSIONS:

The risk of postoperative complications is affected by both surgical factors and the general health of the patient. Elderly patients with chronic disease history, hypertension, and arrhythmias have an increased risk of postoperative complications. Knowledge of these factors will identify a group of patients requiring internal consultation and optimization of preoperative treatment and postoperative follow-up.

Keywords: Comorbidity, nonsmall cell lung cancer, postoperative complication

Despite advances in oncological treatment, lung cancer is currently the leading cause of death from malignant neoplasia.[1,2] The disease is most often related to the elderly and long-term smokers, which causes a sizable proportion of patients with coexisting illnesses.[3] Radical surgical treatment is the preferred treatment for patients with early-stage nonsmall cell lung cancer (NSCLC).[4] Qualification for surgical treatment should consider a risk associated with the impact of comorbidities on the general condition of the patient. According to commonly accepted recommendations, the basic parameters considered for the qualification of patients for surgical treatment are the stage of the cancer, patient's performance, and the functional parameters of the lungs.[5,6] The effect of comorbidities with lung cancer on oncological treatment and prognosis has been discussed for several years. In patients in early stages of cancer who are candidates for radical surgical treatment, coexisting illnesses may have significant importance.[7,8] In this retrospective study, postoperative complications were identified in patients with surgically treated NSCLC. We made an attempt to identify the risk factors for postoperative complications, with a special focus on the coexisting diseases.

Methods

Patients

A total of 400 patients (280 men and 120 women) diagnosed with NSCLC, who have been qualified for surgical treatment and operated on in the selected period (from January 2012 to September 2013), were included in this retrospective study. To assure a real-life character of the study, no other specific inclusion/exclusion criteria have been applied. For all patients, data about histopathological diagnosis (squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, and other histological types) and stage of the disease (tumor–node–metastasis [TNM] classification at the time of surgical eligibility – the 7th edition[9]) were collected. Medical records have provided data on the incidence of comorbidities (including coronary artery disease, hypertension, history of myocardial infarction, atrial fibrillation, and other arrhythmias – newly diagnosed and recurrent arrhythmias, peripheral arterial disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), tuberculosis, diabetes, stroke, thyroid disease, other cancers, and chronic kidney disease). In all patients, the extent of surgery (segmentectomy, lobectomy, bilobectomy, and pneumonectomy), type of surgical access (video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery [VATS] and thoracotomy), and postoperative hospitalization were determined.

The occurrence of complications during the postoperative period, up to the date of discharge from the hospital, was analyzed. Any complications were considered, regardless of severity and major pulmonary and cardiovascular complications according to the European Society of Thoracic Surgeons (ESTS), including pneumonia, atelectasis requiring bronchoscopy, adult respiratory distress syndrome, mechanical ventilation lasting >24 h, pulmonary edema, pulmonary embolism, myocardial ischemia, heart failure, arrhythmias, stroke, and acute kidney failure.[10]

In the study group, comorbidities of lung cancer were analyzed. Postoperative complications and severe pulmonary and cardiovascular complications according to ESTS were investigated. The incidence of postoperative complications was analyzed according to the age of the patients (≤65 and >65 years), the type of surgical procedure performed, surgical access applied, and the presence of particular comorbidities. The factors affecting the hospitalization time after surgery were also determined.

Quantitative variables are represented by the following descriptive statistics – mean (range, standard deviation [SD]) – and – qualitative variables as number (n) and percentage (%). For quantitative variables, compliance with the Gaussian distribution was verified using the Shapiro–Wilk test. The homogeneity of variance was verified by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. The Student's t-test was used to examine the differences between groups, for Gaussian distribution variables and homogeneous variance. The Mann–Whitney U-test was used for variables with non-Gaussian distribution or nonhomogeneous variance. Pearson's test was used to examine the relationship between variables of Gaussian distribution. In case one of the variables did not show Gaussian distribution, the Spearman's test was used. Pearson's Chi-squared test was used to investigate the differences between groups for qualitative variables. Statistical significance level of P = 0.05 was assumed. Univariate analysis and multivariate logistic regression (stepwise progressive model) were performed to identify the risk factors for postoperative complications. Factors identified as significant for postoperative complications from univariate analysis were included in multivariate analysis model. Statistical analyses were performed using Statistica 10.0 software (StatSoft, Inc., Tulsa, Oklahoma, USA).

Ethics

For this type of study (retrospective), formal consent is not required.

Results

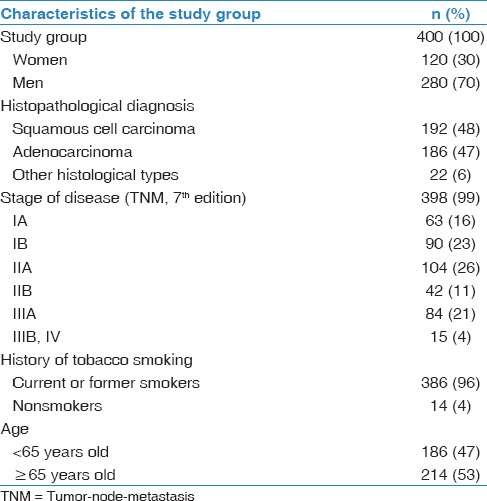

A group of 400 patients treated for NSCLC (280 men and 120 women) were analyzed. The mean age of the patients was 64 years (34–84; SD = 7.47). The characteristics of the study group are shown in Tables 1 and 2. Data on surgical operations are presented in Table 3.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study group

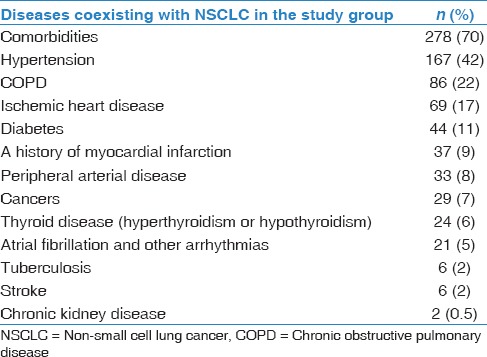

Table 2.

Diseases coexisting with non-small cell lung cancer in the study group

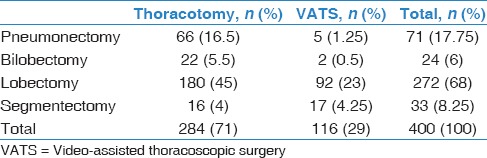

Table 3.

Number of operations performed with regard to operational access

The occurrence of postoperative complications

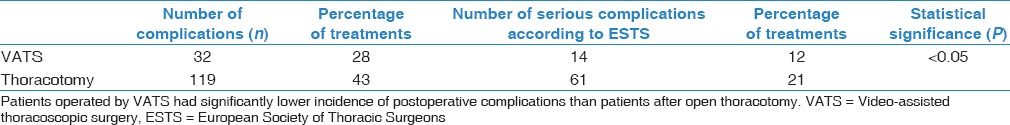

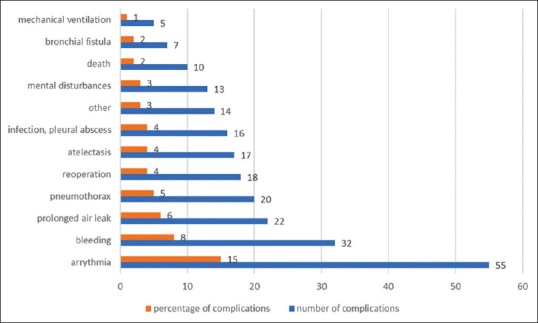

Postoperative complications were observed in 151 patients (39% operated), including severe pulmonary and cardiovascular complications according to ESTS in 75 patients (19%). In the study group, 10 deaths occurred (2%). The description of postoperative complications is presented in Tables 4 and 5 and in Figures 1 and 2.

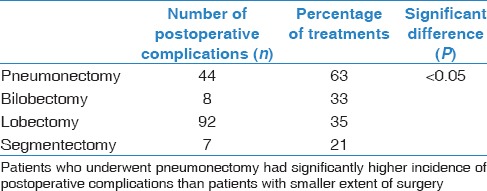

Table 4.

Occurrence of postoperative complications depending on the extent of surgery

Table 5.

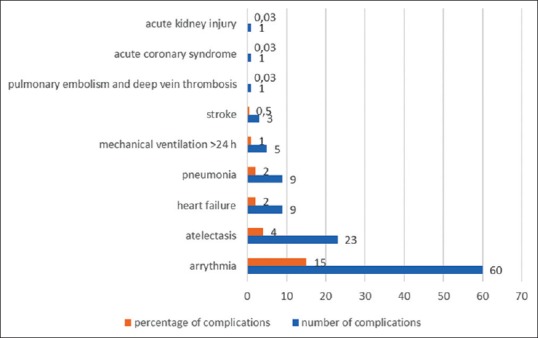

Occurrence of postoperative complications depending on the operational access applied

Figure 1.

The occurrence of postoperative complications in the study group

Figure 2.

The occurrence of severe pulmonary and cardiovascular complications according to the European Society of Thoracic Surgeons in the study group

The influence of comorbidities on the occurrence of postoperative complications

There was a significantly higher incidence of postoperative complications in patients with cardiac arrhythmias (P = 0.02). For COPD (P = 0.08) and diabetes (P = 0.09), the correlation with the occurrence of complications was close to statistically significant. There was no relationship between the incidence of postoperative complications and thyroid disease, stroke, peripheral arterial disease, ischemic heart disease and myocardial infarction, and pulmonary tuberculosis. Statistical analyses did not include chronic kidney disease due to the small number of patients with this coexisting disease (n = 2, 0.5% of the study group).

The occurrence of serious complications according to ESTS was found more often in patients >65 years of age with coexisting illnesses, especially hypertension (P < 0.05).

Postoperative complications were significantly less often in patients with a history of cancer other than lung cancer (P = 0.03), which was associated with lower stages of NSCLC (stage Ia and Ib, according to TNM classification, P < 0.05) and less extensive surgical procedures (segmentectomy, P < 0.003) in this group.

The influence of the extent of surgery and the type of surgical access on postoperative complications

Most complications were found in patients undergoing pneumonectomy (P < 0.05). The rate of complications after lobectomy and bilobectomy was similar. The least complications occurred after the segmentectomy. Data on the occurrence of postoperative complications depending on the extent of surgery are presented in Table 3.

There was a significantly lower incidence of postoperative complications and serious pulmonary and cardiovascular complications according to ESTS in patients operated by the VATS compared to thoracotomy (P < 0.05). Data on the occurrence of postoperative complications depending on operational access are presented in Table 4.

Univariate analysis of risk factors for postoperative complications

Univariate analysis included variables that were significantly associated with the occurrence of complications. The following risk factors for postoperative complications were identified: pneumonectomy (odds ratio [OR] 2.84, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.77–4.57, P = 0.00), atrial fibrillation and other arrhythmias (OR 1.63, 95% CI: 1.04–2.57, P = 0.03), and thoracotomy (OR 1.4, 95% CI: 1.10–1.77, P = 0.0055).

COPD diagnosis was associated with a higher risk of complications – close to statistical significance (OR 1.23, 95% CI: 0.97–1.57, P = 0.09) and similarly diabetes (OR 1.32, 95% CI: 0.95–1.82, P = 0.09).

Segmentectomy was associated with a significantly lower risk of postoperative complications (OR 0.45, 95% CI: 0.23–0.89, P = 0.02). Patients with a history of neoplasm also had a lower risk of complications (OR 0.62, 95% CI: 0.39–0.98, P = 0.04).

Significant risk of major pulmonary and cardiovascular complications according to ESTS was associated with total comorbidity (OR 1.67, 95% CI: 1.14–2.44, P = 0.008), in particular arterial hypertension (OR 1.52, 95% CI: 1.10–2.11, P = 0.01) and atrial fibrillation and other arrhythmias (OR 1.93, 95% CI: 0.99–3.77, P = 0.05) and age ≥65 years (OR 1.52, 95% CI: 1.10–2.10, P = 0.01).

Multivariate analysis of risk factors for postoperative complications

Risk factors identified as significant for postoperative complications and severe pulmonary and cardiovascular complications from univariate analysis were included in multivariate analysis models (stepwise progressive model). An important risk factor for postoperative complications was pneumonectomy (P = 0.000, OR 2.844, 95% CI: 1.756–4.582) and cardiac arrhythmia (P = 0.04, OR 1.610, 95% CI: 1.011–2.565). The risk factors for major pulmonary and cardiovascular complications according to ESTS included age ≥65 years (P = 0.028, OR 1.452, 95% CI: 1.040–2.026) and the presence of coexisting diseases (P = 0.018, OR 1.593, 95% CI: 1.083–2.344).

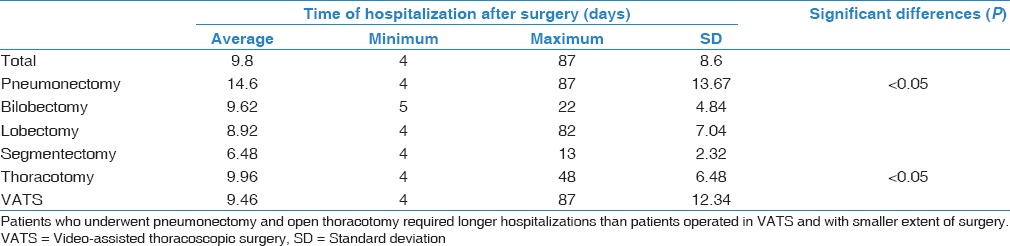

The influence of postoperative complications and the time of hospitalization

The mean hospitalization time after surgery was 9.8 days (4–87; SD 8.59). Data on hospitalization time are presented in Table 6. The extent of surgery has had a significant impact on hospitalization. The hospitalization time of pneumonectomized patients was significantly longer than after lobectomy and segmentectomy (P < 0.05) but did not significantly differ from hospital admission to bilobectomy. Patients undergoing VATS required shorter hospitalizations than patients operated by open method (P = 0.000). The occurrence of postoperative complications was associated with longer hospitalization time (P < 0.05).

Table 6.

Time of hospitalization following surgery, depending on the extent of surgery and surgical access

Discussion

For several years, the oncological literature is a discussion on the importance of the diseases coexisting with lung cancer for the course of treatment and prognosis. Opinion on the importance of coexisting diseases in this group of patients is divided. There are opinions that the diseases coexisting with lung cancer are important for the course of oncological treatment, the occurrence of complications, and long-term prognosis of patients. Thereby, they should be considered for qualification for oncological treatment.[11] This applies particularly to patients in early stages of disease eligible for radical (including surgical) treatment.[7,8,12] In patients with advanced lung cancer, the effect of the tumor itself on the prognosis is predominant, and the significance of coexisting diseases is lower.[13,14]

Radical surgical treatment is the method of choice in patients with NSCLC in early stages of disease and provides chance for cure.[4] However, patients with lung cancer are usually elderly people with multiple comorbidities, especially tobacco-related diseases. The presence of comorbidities often affects the decisions of physicians that qualify patients for treatment, who prefer less aggressive treatment due to concern of possible complications.[15] This is a significant clinical problem for an internist or pulmonologist who refers the patient for surgical treatment. The main aim of the article was to determine the effect of comorbidities of lung cancer on the course of surgical treatment, in order to qualify patients for surgery, avoiding on the one hand excessive operational risk and on the other hand, too cautious approach, reducing the chances of a cure.

In this article, we attempted to identify the risk factors for postoperative complications in the Polish population of patients with lung cancer, with particular emphasis on the role of coexisting diseases. We have analyzed a large group of patients (n = 400) operated on because of NSCLC, representative of gender, age, and history of smoking.[3] High prevalence of comorbidities, most commonly hypertension (42%) and COPD (22%), was observed in the study group. These diseases were more frequent in the study group than those described for the Polish population,[16,17,18] which can be attributed to the prevalence of tobacco smokers in the study group (94% of current or former smokers).

In the present study, the overall complication rate was 39%, and severe pulmonary and cardiovascular complications according to ESTS database were 19%. In the available literature, both reports describing a similar incidence of complications[19,20] and also reports of significantly lower postoperative complications can be found.[21,22] Differences in the reported incidence of complications are due to the complicated reporting criteria. This is caused by the detailed recording of clinical events such as the recurrence of previously diagnosed arrhythmia in the postoperative period or the necessity of transfusion of blood products, which are not considered by many authors but are important for the assessment of the postoperative period.

In the available literature, there is an agreement that the severity of disease according to TNM and the extent of surgery has an effect on the course of the postoperative period,[22,23,24] which is also confirmed by our results, although there are reports that undermine the importance of progression as a risk factor of complications.[21]

As for the importance of other factors, including coexisting illnesses, researchers' opinions are more divided. Many studies have demonstrated the significant effects of chronic pulmonary disease and poor lung function on complications and mortality in postoperative patients.[19,25,26] An article has also been published that undermines the importance of spirometry parameters for the incidence of postoperative complications.[27] Our study did not show statistically significant effects of COPD on the incidence of postoperative complications, although the results were close to statistical significance. This could have resulted from lower COPD severity in the study group compared to other studies on this subject.[28] Kim et al. have shown that the effect of COPD on the incidence of postoperative complications is relatively small in the early stages of the disease and increases with the deterioration of spirometric parameters, hence the absence of statistically significant differences in the study group.[19]

Researchers' opinions on the importance of cardiovascular diseases in the postoperative course are divided. In many studies, there is a significantly higher risk of postoperative complications in cardiologically ill patients,[29,30] although some authors present different data.[21] In our study, we did not observe the relationship between the occurrence of complications and the diagnosis of ischemic heart disease or myocardial infarction, but we showed a significantly higher incidence of complications in patients with hypertension and arrhythmias. Atrial fibrillation is a particularly common complication in patients operated on for lung cancer.[22] The high incidence of arrhythmias in patients treated for lung cancer is thought to be associated with mediastinal lymph node dissection.[31] In the study group, cardiac arrhythmias accounted for 80% of the observed complications and related to 15% of patients treated, which is higher than reported by other authors.[22,31] It is probably related to the inclusion of recurrence of previously diagnosed arrhythmias in our study.

There were significantly fewer postoperative complications in patients with a prior history of oncological treatment. These patients at the same time were characterized by relatively low NSCLC stage and a higher proportion of saving treatments, which can be explained by earlier diagnosis of lung cancer in patients with a history of other cancer disease under constant oncological control.

There was also a relationship between the occurrence of postoperative complications and surgical access (thoracotomy vs. VATS). Patients undergoing VATS had significantly fewer postoperative complications and serious pulmonary and cardiovascular complications than patients operated by open method. These observations correspond to previous reports.[32]

The extent of the surgery had a significant effect on the duration of hospitalization after the procedure (the longest hospital stay after pneumonectomy and bilobectomy) and applied surgical access (after open surgery). Furthermore, postoperative complications were associated with prolonged hospitalization.

Conclusion

We have identified a number of factors that affect the increased risk of postoperative complications in patients treated for NSCLC. Significant for the occurrence of complications are both surgical-related factors (extent of surgery and type of surgical access) and factors related to the general state of health of the patient. Elderly patients, with chronic disease history and hypertension, and especially patients with heart rhythm disorders, have an increased risk of postoperative complications. Knowledge of these risk factors will identify a group of patients requiring internal consultation and optimization of preoperative treatment and postoperative follow-up. This will also allow to avoid higher hospital costs associated with the occurrence of complications. In the age of progressive specialization of particular fields of medicine, it is particularly important to assess the overall clinical condition of the patient by an interdisciplinary team.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank Mrs. Magdalena Lewandowska, MSc, for statistical analysis.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:5–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brambilla E, Travis WD. Lung cancer. In: Stewart BW, Wild CP, editors. World Cancer Report. Lyon: World Health Organization; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kosacka M, Jankowska R. The epidemiology of lung cancer. Pneumonol Alergol Pol. 2007;75:76–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Howington JA, Blum MG, Chang AC, Balekian AA, Murthy SC. Treatment of stage I and II non-small cell lung cancer: Diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American college of chest physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2013;143:e278S–313S. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-2359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jassem J, Biernat W, Bryl M, Chorostowska-Wynimko J, Dziadziuszko R, Krawczyk P, et al. The role of systemic therapies of non-small cell lung cancer and malignant pleural mesothelioma: Updated expert recommendations. Pneumonol Alergol Pol. 2014;82:133–49. doi: 10.5603/PiAP.2014.0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lim E, Baldwin D, Beckles M, Duffy J, Entwisle J, Faivre-Finn C, et al. Guidelines on the radical management of patients with lung cancer. Thorax. 2010;65(Suppl 3):iii1–27. doi: 10.1136/thx.2010.145938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lüchtenborg M, Jakobsen E, Krasnik M, Linklater KM, Mellemgaard A, Møller H, et al. The effect of comorbidity on stage-specific survival in resected non-small cell lung cancer patients. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48:3386–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Birim O, Kappetein AP, Bogers AJ. Charlson comorbidity index as a predictor of long-term outcome after surgery for nonsmall cell lung cancer. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2005;28:759–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2005.06.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldstraw P. International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer Staging Manual in Thoracic Oncology. Orange Park: Editorial Rx Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brunelli A, Berrisford RG, Rocco G, Varela G, European Society of Thoracic Surgeons Database Committee. The European thoracic database project: Composite performance score to measure quality of care after major lung resection. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2009;35:769–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2009.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feinstein AR, Wells CK. A clinical-severity staging system for patients with lung cancer. Medicine (Baltimore) 1990;69:1–33. doi: 10.1097/00005792-199001000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Volpino P, Cangemi R, Fiori E, Cangemi B, De Cesare A, Corsi N, et al. Risk of mortality from cardiovascular and respiratory causes in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease submitted to follow-up after lung resection for non-small cell lung cancer. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 2007;48:375–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mellemgaard A, Bredin P, Iachina M, Green A, Krasnik M, Jakobsen E, et al. Comorbidity: Usage of, and survival after chemotherapy for advanced lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(15_Suppl):e19157. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ball D, Thursfield V, Irving L, Mitchell P, Richardson G, Torn-Broers Y, et al. Evaluation of the simplified comorbidity score (Colinet) as a prognostic indicator for patients with lung cancer: A cancer registry study. Lung Cancer. 2013;82:358–61. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2013.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Rijke JM, Schouten LJ, ten Velde GP, Wanders SL, Bollen EC, Lalisang RI, et al. Influence of age, comorbidity and performance status on the choice of treatment for patients with non-small cell lung cancer; results of a population-based study. Lung Cancer. 2004;46:233–45. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2004.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zdrojewski T, Szpakowski P, Bandosz P, Pajak A, Wiecek A, Krupa-Wojciechowska B, et al. Arterial hypertension in Poland in 2002. J Hum Hypertens. 2004;18:557–62. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Niepsuj G, Kozielski J, Niepsuj K, Ziora D, Polońska A, Cieślicki J, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in inhabitants of zabrze. Wiad Lek. 2002;55(Suppl 1):354–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pływaczewski R, Bednarek M, Jonczak L, Zieliński J. Prevalence of COPD in Warsaw population. Pneumonol Alergol Pol. 2003;71:329–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim ES, Kim YT, Kang CH, Park IK, Bae W, Choi SM, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors for postoperative pulmonary complications after lung cancer surgery in patients with early-stage COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2016;11:1317–26. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S105206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rauma V, Salo J, Sintonen H, Räsänen J, Ilonen I. Patient features predicting long-term survival and health-related quality of life after radical surgery for non-small cell lung cancer. Thorac Cancer. 2016;7:333–9. doi: 10.1111/1759-7714.12333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fernandez FG, Kosinski AS, Burfeind W, Park B, DeCamp MM, Seder C, et al. The society of thoracic surgeons lung cancer resection risk model: Higher quality data and superior outcomes. Ann Thorac Surg. 2016;102:370–7. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2016.02.098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sawada S, Suehisa H, Ueno T, Yamashita M. Changes in post-operative complication and mortality rates after lung cancer resection in the 20-year period 1995-2014. Acta Med Okayama. 2016;70:183–8. doi: 10.18926/AMO/54417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Birim O, Kappetein AP, van Klaveren RJ, Bogers AJ. Prognostic factors in non-small cell lung cancer surgery. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2006;32:12–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Duque JL, Ramos G, Castrodeza J, Cerezal J, Castanedo M, Yuste MG, et al. Early complications in surgical treatment of lung cancer: A prospective, multicenter study. Grupo Cooperativo de Carcinoma Broncogénico de la Sociedad Española de Neumología y Cirugía Torácica. Ann Thorac Surg. 1997;63:944–50. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(97)00051-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Licker MJ, Widikker I, Robert J, Frey JG, Spiliopoulos A, Ellenberger C, et al. Operative mortality and respiratory complications after lung resection for cancer: Impact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and time trends. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;81:1830–7. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.11.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sekine Y, Behnia M, Fujisawa T. Impact of COPD on pulmonary complications and on long-term survival of patients undergoing surgery for NSCLC. Lung Cancer. 2002;37:95–101. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5002(02)00014-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Birim O, Maat AP, Kappetein AP, van Meerbeeck JP, Damhuis RA, Bogers AJ, et al. Validation of the Charlson comorbidity index in patients with operated primary non-small cell lung cancer. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2003;23:30–4. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(02)00721-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang Z, Zhang J, Cheng Z, Li X, Wang Z, Liu C, et al. Factors affecting major morbidity after video-assisted thoracic surgery for lung cancer. J Surg Res. 2014;192:628–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2014.07.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bernard A, Deschamps C, Allen MS, Miller DL, Trastek VF, Jenkins GD, et al. Pneumonectomy for malignant disease: Factors affecting early morbidity and mortality. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2001;121:1076–82. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2001.114350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kanzaki R, Inoue M, Minami M, Shintani Y, Funaki S, Kawamura T, et al. Outcomes of lung cancer surgery in patients with coronary artery disease: A decade of experience at a single institution. Surg Today. 2017;47:27–34. doi: 10.1007/s00595-016-1355-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Muranishi Y, Sonobe M, Menju T, Aoyama A, Chen-Yoshikawa TF, Sato T, et al. Atrial fibrillation after lung cancer surgery: Incidence, severity, and risk factors. Surg Today. 2017;47:252–8. doi: 10.1007/s00595-016-1380-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Piwkowski C. Wydaw Nauk. Poznań: Uniwersytet Medyczny im. Karola Marcinkowskiego w Poznaniu; 2013. Evaluation of video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) lobectomy in treatment of lung cancer patients – A single center experience. [Google Scholar]