Abstract

Policies addressing limitations of medical therapy in patients with advanced medical conditions are typically referred to as Code Status (No Code) policies or Do-Not-Resuscitate (DNR) status polices. Inconsistencies in implementation, understanding, decision-making, communication and management of No Code or DNR orders have led to delivery of poorer care to some patients. Several experts have called for a change in the current approach. The new approach, Goals of Care paradigm, aims to contextualize the decisions about resuscitation and advanced life support within the overall plan of care, focusing on choices of treatments to be given rather than specifically on treatments not to be given. Adopting “Goals of Care” paradigm is a big step forward on the journey for optimizing the care for patients with advanced medical conditions; a journey that requires collaborative approach and is of high importance for patients, community and healthcare systems.

Keywords: Cardiopulmonary resuscitation, critical care, decision-making, palliative care, patient comfort

Policies addressing limitations of medical therapy in patients with advanced medical conditions are integral components of clinical practice worldwide and are mandated by hospital accreditation agencies.[1,2] These policies often focus on decisions regarding resuscitation and advanced life support and are typically referred to as Code Status (No Code) policies or Do-Not-Resuscitate (DNR) status polices. These policies have been important tools in recognizing the limited value of aggressive life support in patients with advanced medical conditions. Studies have shown that around 80%–90% of patients who die in the hospital have DNR orders.[3,4] In Saudi Arabia, several hospitals have adopted “No Code” or DNR polices based on related Fatwa,[5] on Code of Ethics for Healthcare Practitioners by the Saudi Commission for Health Specialties,[6] and on the newly released National Policy And Procedure For DNR Status by the Saudi Health Council.[7] Similar to other countries, studies from hospitals with established policies in Saudi Arabia demonstrated that DNR orders were written for 66% and 84% of patients who eventually die in Intensive Care Units and wards, respectively.[8] However, inconsistencies in implementation, understanding, decision-making, communication, and management of No Code or DNR orders have led to delivery of poorer care to some patients.

In this article, we present reasons why a paradigm shift is needed in the approach to addressing limitations of medical therapy in patients with advanced medical conditions in Saudi Arabia and present a suggested model based on international and local experiences.

Why Change is Needed?

Challenges of the approach of Code Status or DNR have been increasingly recognized, not only in Saudi Arabia but also worldwide.

Inconsistencies in implementation of the concept of No Code or DNR; for example, many hospitals in Saudi Arabia do not have such policies

Inconsistencies in understanding the concept of No Code or DNR: Many practitioners, patients, and families still have uncertainties about the concept of No Code or DNR. A survey of interns and residents in four major hospitals in Jeddah demonstrated lack of familiarity with DNR policies and limited understanding when it comes to treating DNR-labeled patients[9]

Inconsistencies in the decision-making of No Code or DNR: The involvement of patients and families in the decision-making process can be limited with the predominance of physician-based approach in the decision-making process.[9] There are also ethical concerns about the inadequate ways that DNR decisions are made and how they are communicated to patients or their families.[10] Furthermore, patients' dignity, religious concerns, and emotional support aspects are not sufficiently addressed in many existing policies

Inconsistencies in communication of No Code or DNR discussions: It has been noted that the conventional approach of DNR policies may not lead to accurate mutual comprehension between clinicians and patients and to the total and necessary grasp of the latter about the concept of DNR.[11] It is our experience that the “negative” terminology implied by the terms “No Code” or DNR is often perceived by patients and families with suspicion and alarm. The focus of discussion related to Code Status is often isolated from the larger and the obligatory, in our view, context of a patient's plan of care.[11] Due to these difficulties, such conversations may never occur or occur too late[12,13]

Inconsistencies in the management of No Code or DNR orders: There is a common false belief among health-care professionals that a “No Code” or “DNR” order always means that the patient is approaching end of life and that it means that other treatments should be withheld, yet reports from the United Kingdom showed that as much as 50% of inpatients labeled as “No Code” leave hospital to home. Studies have shown that inpatients with “No Code” or DNR status may receive less adequate treatment and have higher mortality than patients without this status.[14,15,16,17,18]

A Proposed Model: Goals of Care

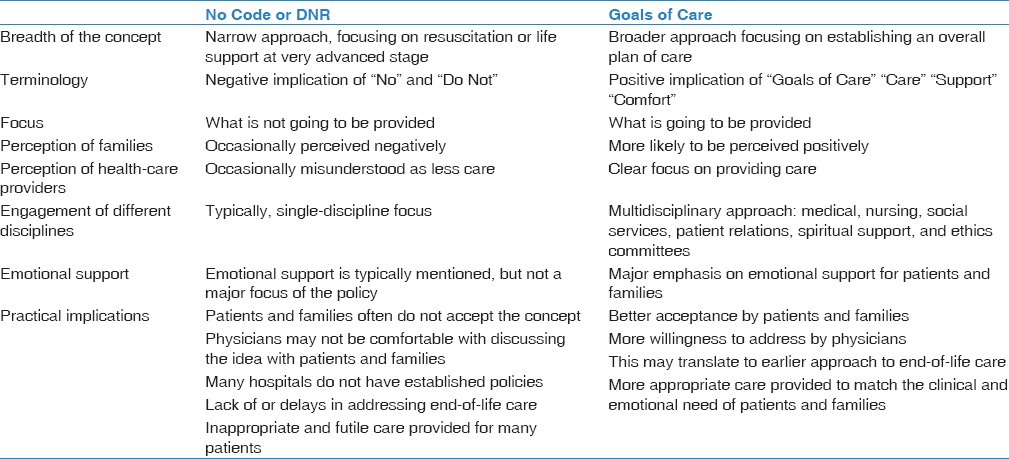

Given these concerns, several experts have called for a change in the current approach.[4] The new approach, Goals of Care paradigm, aims to contextualize the decisions about resuscitation and advanced life support within the overall plan of care, focusing on choices of treatments to be given rather than specifically on treatments not to be given (e.g., withholding cardiopulmonary resuscitation).[4,11] The differences between the traditional approach and Goals of Care model are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison between the traditional model of No Code or Do-Not-Resuscitate (DNR) and the Goals of Care models

The “Goals of Care” paradigm has been designed as a replacement for “No Code” or DNR orders. This approach has been used in several countries, including the USA, Canada, the United Kingdom, and Australia.[19] Recently, the Ministry of National Guard Health Affairs, Saudi Arabia, has revised the existing “No Code” policy to be replaced by “Goals of Care Determination” policy to reflect this new broader approach. If the patient's assessment of likely treatment outcomes suggests the need to have limitations of the levels of care, clinicians determine a patient's situation to one of the two levels of “Goals of Care” instead of “No Code” status as has been the case before; these are either “Support Care” or “Comfort Care” levels.

Support Care, in our model, refers to the level of care in which all types of medical therapy that are normally provided to patients on hospital wards are maintained. This includes physician visits, vital sign monitoring, oxygen, intravenous fluids, nutrition, nursing care, antibiotics, deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis, and respiratory care (suctioning, chest physiotherapy, bronchodilators, etc.). Selected oncology patients can receive palliative anticancer therapy. However, the following therapies are not provided: cardiopulmonary resuscitation including chest compressions, endotracheal intubation, mechanical ventilation, initiation of vasopressor therapy, initiation of renal replacement therapy, admission to an Intensive Care Unit, and major surgical interventions.

For those patients who are already in a critical care area and show no response to aggressive life support interventions, Support Care refers to the level of care in which there is no escalation of life support measures while continuing those measures already applied. Patients with Support Care status who require palliative procedures (i.e., percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube insertion and tracheostomy) can be taken to the operating room. However, major surgical or invasive procedures that are unlikely to change the patient's outcome may not be performed in Support Care patients.

Comfort Care refers to the level of care in which treatments aiming at symptom relief are provided but not disease-targeted therapies. Patients in this group will have physician visitation and nursing care. In addition, nutritional and feeding support will continue. Patients must receive appropriate measures that reduce suffering, pain, thirst, dyspnea, etc., However, other aspects of disease-targeted therapy may not be continued.

Goals of Care policies should emphasize that appropriate measures are taken and monitored to ensure the comfort and dignity of patients at all times. Efforts must be made to reduce patient pain and symptoms. Visiting hours should preferably be extended for immediate family members. Support Care or Comfort Care must not lead to a reduction in the level of communication with the patient and family, but must lead to more support including regular patient assessment and active communication with the patient and family.

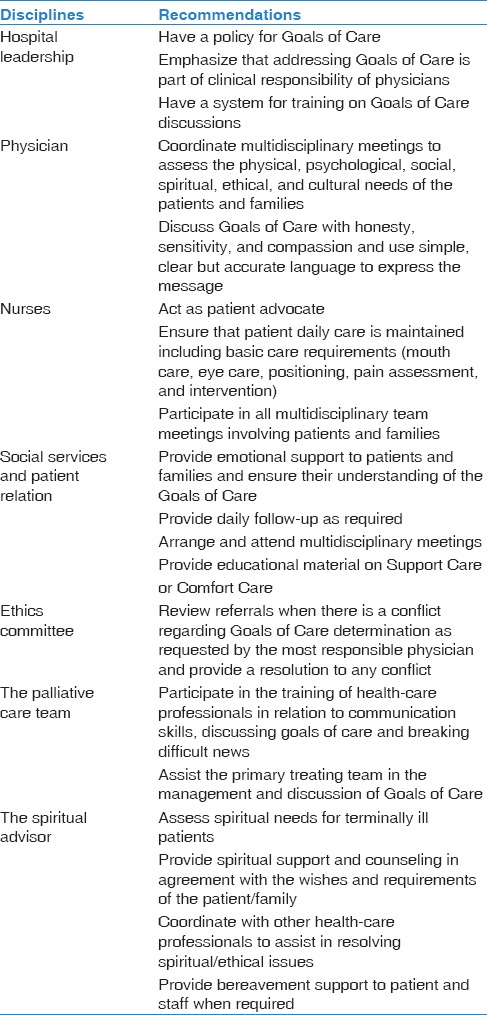

The Goals of Care paradigm emphasizes the multidisciplinary approach that requires the involvement of all health-care providers. Table 2 provides an outline of involvement of different disciplines in the management of patients with Support Care or Comfort Care. Support Care and Comfort Care status determination should activate referral to social services and patient relations for implementation of regular structured follow-up, support, and communication with the family.

Table 2.

Multidisciplinary involvement in managing limitations of medical therapy in patients with advanced medical conditions

Applicability in Saudi Arabia

Using Goals of Care to guide decision-making about medical therapy in patients with advanced medical conditions is expected to enhance the quality of patient care by addressing the aspects of medical care and emotional support as part of a broader global care plan. This would likely alleviate the uncertainties of patients and families regarding decisions that involve limitations of medical care and may reduce refusals and delays in the process. Studies from Saudi Arabia comparing this newly introduced approach with the traditional No Code or DNR approach are needed. A randomized vignette study from the UK compared the approach of DNR orders and Goals of Care approach (also called the Universal Form of Treatment Options [UFTO]) on nurses' decision-making about a deteriorating patient.[20] Nurses in the DNR group agreed or strongly agreed to initiate fewer intense nursing interventions than the UFTO and no-form groups (P < 0.001), including decisions related to monitoring, escalation of concerns, and initiation of treatments (all P < 0.001).[20] On the other hand, there was no difference between the UFTO and no-form groups overall (P = 0.78) or in any of the individual decisions. The study concluded that DNR approach, but not the UFTO approach, appeared to negatively influence nurses' decision-making in a deteriorating patient vignette. Based on these findings, the authors recommended that hospitals adopt the Goals of Care approach.[20]

The Way Forward

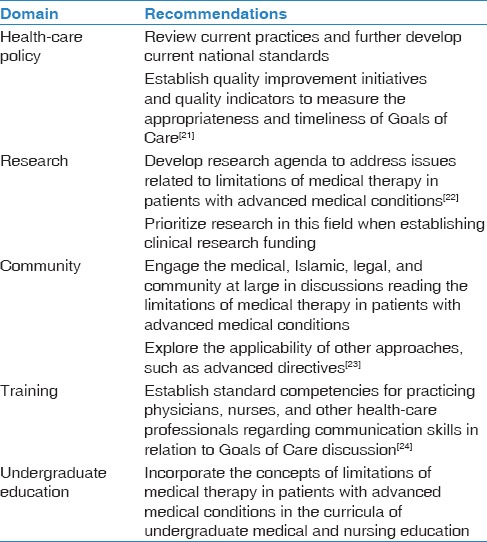

Adoption of Goals of Care concept nationally may address the current challenges in discussions regarding limitations of medical therapy for patients with advanced medical conditions. In addition, it may help bridging the gap in understanding among health-care providers regarding this important issue in Saudi Arabia. Table 3 summarizes high-level recommendations for future directions in addressing Goals of Care with selected references included as examples of similar initiatives. Of particular importance is having structured training to practicing professionals as well as in-training residents. In addition, there is a need for building capacity in training skills of communicating bad news and in incorporating palliative care services across different hospitals.

Table 3.

Selected high-level recommendations for future directions in addressing Goals of Care. Some references are included as examples of similar initiatives

We believe that adopting “Goals of Care” paradigm is a big step forward on the journey for optimizing the care for patients with advanced medical conditions; a journey that requires collaborative approach and is of high importance for our patients, community, and health-care systems.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Joint Commission International Accreditation Standards for Hospitals. Effective. 6th edition. Published by Joint Commision International(JCI); 2017. PFR.1.2 ME 3 & 4, PFR.2.1, AOP. 1.7 ME 1-7, COP. 7- ME 1-7. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saudi Central Board for Accreditation of Healthcare Institutions (CBAHI) National Hospital Standards. PFR.12, 2014. 3rd edition. Published by CBAHI; 2015. Jan, Effective. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aune S, Herlitz J, Bång A. Characteristics of patients who die in hospital with no attempt at resuscitation. Resuscitation. 2005;65:291–9. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2004.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fritz Z, Slowther AM, Perkins GD. Resuscitation policy should focus on the patient, not the decision. BMJ. 2017;356:j813. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: [Last accessed on 2017 Dec 25]. Fatwa No 12086, Dated 30/6/1409 (Hijra) Issued From the Presidency of the Administration of Islamic Research and Ifta. Available from: http://HYPERLINK. http://www.alifta.net/fatawa/fatawachapters.aspx?languagename=en&View=Page&PageID=299&PageNo=1&BookID=17 . [Google Scholar]

- 6.Code of Ethics for Healthcare Practitioners. The Saudi Commission for Health Specialties Department of Medical Education & Postgraduate Studies. http://docplayer.net/11868886-Codeof-ethics-for-healthcare-practitioners-the-saudi-commissionfor-health-specialties-department-of-medical-educationpostgraduate-studies.html . 52p; L.D. no. 1435/9206; ISBN: 978-603-90608-1-9. [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Policy And Procedure For Do-Not-Resuscitate (DNR) Status. Saudi Health Council. 2017 Jan; Rabi II 1438. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rahman MU, Arabi Y, Adhami NA, Parker B, Al-Shimemeri A. The practice of do-not-resuscitate orders in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. The experience of a tertiary care center. Saudi Med J. 2004;25:1278–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amoudi AS, Albar MH, Bokhari AM, Yahya SH, Merdad AA. Perspectives of interns and residents toward do-not-resuscitate policies in Saudi Arabia. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2016;7:165–70. doi: 10.2147/AMEP.S99441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fritz Z, Fuld J. Ethical issues surrounding do not attempt resuscitation orders: Decisions, discussions and deleterious effects. J Med Ethics. 2010;36:593–7. doi: 10.1136/jme.2010.035725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaldjian LC, Broderick A. Developing a policy for do not resuscitate orders within a framework of goals of care. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2011;37:11–9. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(11)37002-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Childers JW, Back AL, Tulsky JA, Arnold RM. REMAP: A Framework for goals of care conversations. J Oncol Pract. 2017;13:e844–50. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2016.018796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gouda A, Al-Jabbary A, Fong L. Compliance with DNR policy in a tertiary care center in Saudi Arabia. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36:2149–53. doi: 10.1007/s00134-010-1985-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen JL, Sosnov J, Lessard D, Goldberg RJ. Impact of do-not-resuscitation orders on quality of care performance measures in patients hospitalized with acute heart failure. Am Heart J. 2008;156:78–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.01.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kazaure H, Roman S, Sosa JA. High mortality in surgical patients with do-not-resuscitate orders: Analysis of 8256 patients. Arch Surg. 2011;146:922–8. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2011.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McNeill D, Mohapatra B, Li JY, Spriggs D, Ahamed S, Gaddi Y, et al. Quality of resuscitation orders in general medical patients. QJM. 2012;105:63–8. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcr137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shepardson LB, Youngner SJ, Speroff T, Rosenthal GE. Increased risk of death in patients with do-not-resuscitate orders. Med Care. 1999;37:727–37. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199908000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adams SD, Cotton BA, Wade CE, Kozar RA, Dipasupil E, Podbielski JM, et al. Do not resuscitate status, not age, affects outcomes after injury: An evaluation of 15,227 consecutive trauma patients. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;74:1327–30. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31828c4698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thomas RL, Zubair MY, Hayes B, Ashby MA. Goals of care: A clinical framework for limitation of medical treatment. Med J Aust. 2014;201:452–5. doi: 10.5694/mja14.00623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moffat S, Skinner J, Fritz Z. Does resuscitation status affect decision making in a deteriorating patient? Results from a randomised vignette study. J Eval Clin Pract. 2016;22:917–23. doi: 10.1111/jep.12559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Choosing Wisely. [Last accessed on 2017 Dec 16]. Available from: http://www.choosingwisely.org/clinician-lists/amda-aggressive-or-hospital-level-care-for-frail-elder/

- 22.Johnson AP, Hanvey L, Baxter S, Daren K. Canadian Researchers at the End of Life Network. Development of advance care planning research priorities: A call to action. J Palliat Care. 2013;29:99–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Al-Jahdali H, Baharoon S, Al Sayyari A, Al-Ahmad G. Advance medical directives: A proposed new approach and terminology from an Islamic perspective. Med Health Care Philos. 2013;16:163–9. doi: 10.1007/s11019-012-9382-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.US Department for Veterans Affairs. National Center for Ethics in Health Care. Caring for Patients with Serious Illness: Building Clinicians’ Communication Skills. [Last accessed on 2017 Dec 16]. Available from: https://www.ethics.va.gov/goalsofcaretraining.asp .