ABSTRACT

The RidA protein (PF01042) from Salmonella enterica is a deaminase that quenches 2-aminoacrylate (2AA) and other reactive metabolites. In the absence of RidA, 2AA accumulates, damages cellular enzymes, and compromises the metabolic network. In vitro, RidA homologs from all domains of life deaminate 2AA, and RidA proteins from plants, bacteria, yeast, and humans complement the mutant phenotype of a ridA mutant strain of S. enterica. In the present study, a methanogenic archaeon, Methanococcus maripaludis S2, was used to probe alternative mechanisms to restore metabolic balance. M. maripaludis MMP0739, which is annotated as an aspartate/glutamate racemase, complemented a ridA mutant strain and reduced the intracellular 2AA burden. The aspartate/glutamate racemase YgeA from Escherichia coli or S. enterica, when provided in trans, similarly restored wild-type growth to a ridA mutant. These results uncovered a new mechanism to ameliorate metabolic stress, and they suggest that direct quenching by RidA is not the only strategy to quench 2AA.

IMPORTANCE 2-Aminoacrylate is an endogenously generated reactive metabolite that can damage cellular enzymes if not directly quenched by the conserved deaminase RidA. This study used an archaeon to identify a RidA-independent mechanism to prevent metabolic stress caused by 2AA. The data suggest that a gene product annotated as an aspartate/glutamate racemase (MMP0739) produces a metabolite that can quench 2AA, expanding our understanding of strategies available to quench reactive metabolites.

KEYWORDS: archaeal metabolism, endogenous stress, aspartate/glutamate racemase, 2-aminoacrylate, heterologous gene expression

INTRODUCTION

The archetypal member of the Rid/YER057c/UK114 protein superfamily, RidA from Salmonella enterica, is an imine deaminase with broad substrate specificity (1–3). Characterization of this protein led to the demonstration that the endogenously generated metabolite 2-aminoacrylate (2AA) causes cellular stress by damaging metabolic enzymes. In S. enterica, RidA ameliorates the potential for stress by quenching 2AA (1, 4–7). The Rid family is sequence diverse and conserved across all domains of life (2), suggesting that the S. enterica paradigm is widespread. In fact, RidA proteins from all three domains quench 2AA in vivo and in vitro (1, 6, 8).

Both the generation of 2AA and the consequences of its persistence are linked to the essential cofactor pyridoxal 5′-phosphate (PLP) (1, 6, 9–11). 2AA is a three-carbon enamine produced as a mechanistic intermediate by several PLP-dependent enzymes, notably serine/threonine dehydratases (1, 12–15). 2AA accumulation leads to decreased activity of some PLP-dependent enzymes, including branched-chain amino acid transaminase (IlvE) (EC 2.6.1.42) (6, 16), serine hydroxymethyltransferase (GlyA) (EC 2.1.2.1) (9, 17), and alanine racemase (Alr and DadX) (EC 5.1.1.1) (10) in S. enterica. Collectively, inactivation of these enzymes leads to growth defects in S. enterica ridA strains (6, 9, 10). Diverse phenotypic defects have been observed in other organisms when the relevant RidA homologs are deleted. Several of those phenotypes, including developmental defects in plants (8, 18) and decreased mitochondrial DNA stability in yeast (19–21, 50), were associated with the accumulation of 2AA.

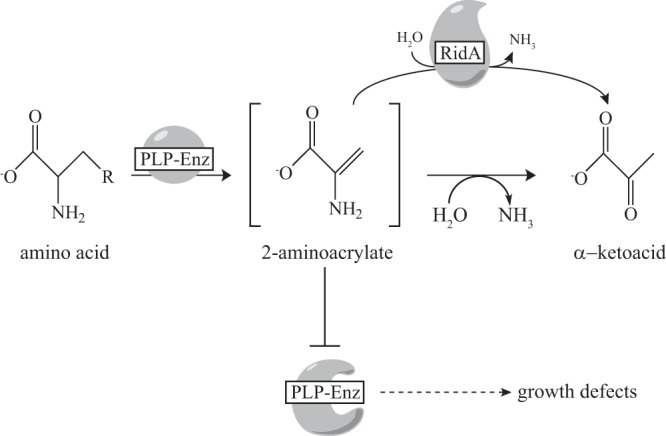

Definition of the RidA paradigm in S. enterica highlighted the potential for uncontrolled metabolites to cause damage, and it emphasized key features of the complex metabolic interactions that can occur in the cellular milieu (Fig. 1). First, reactive metabolites that are obligatory intermediates in PLP-dependent reaction mechanisms can damage cellular processes and compromise fitness. Second, the ability of 2AA to cause cellular damage requires that it leave the active site of the enzyme generator and survive in the cellular milieu long enough to find and to damage target enzymes. The latter point implies a dearth of free water in the cellular milieu, which has implications for the evolution of metabolic pathway strategies (22, 23). The extensive metabolic diversity of life makes it probable that 2AA is not the only metabolite with the potential to damage cellular components (24); furthermore, direct enzymatic quenching is unlikely to be the only mechanism used to modulate reactive molecules. Identifying other proteins or metabolic tactics that can eliminate 2AA stress would provide insights into strategies that have evolved to deal with metabolite stress.

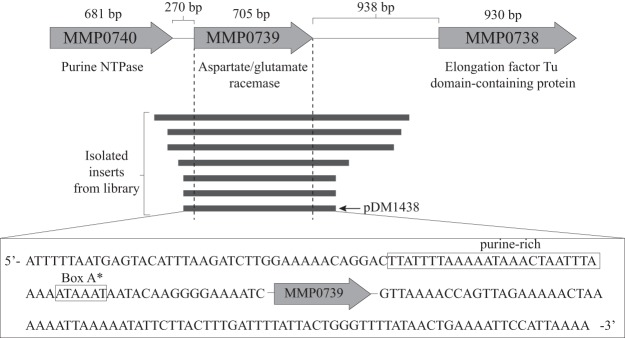

FIG 1.

RidA paradigm of 2AA stress in S. enterica. In S. enterica, 2AA is generated and released from at least three PLP-dependent enzymes (Enz) that catalyze β-elimination reactions with relevant substrates (1, 11). In the absence of RidA, accumulation of 2AA covalently modifies and thus inactivates at least four PLP-dependent enzymes, leading to a number of detectable growth defects (6, 10, 25). R indicates OH (serine), SH (cysteine), or NH2 (2,3-diaminopropionate).

In this study, 2AA was used as a model endogenous stressor in a search for non-RidA proteins that could prevent cellular damage caused by this metabolite. A genomic library of the methanogenic archaeon Methanococcus maripaludis S2, which lacks an annotated RidA in the genome, was used to isolate multicopy suppressors of a S. enterica ridA mutant. In vivo experiments determined that MMP0739 (a putative aspartate/glutamate racemase) functionally substituted for RidA in S. enterica. A working model suggested that complementation by overexpressed heterologous genes was due to quenching of 2AA by a metabolite generated by MMP0739, reflecting a new strategy to deal with metabolite stress.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Methanococcus maripaludis gene product MMP0739 complements an S. enterica ridA mutant.

S. enterica strains lacking ridA are unable to grow on minimal glucose medium supplemented with serine (5 mM) or cysteine (250 μM), due to damage caused by 2AA accumulation (6, 9, 10, 25). Growth can be restored by expressing a functional ridA gene in trans or by supplementing the medium with glycine or isoleucine. The genome of the methanogenic archaeon M. maripaludis lacks any identifiable Rid proteins. A high-copy-number plasmid library of M. maripaludis genomic DNA was used to transform a S. enterica ridA strain (DM12920). Kanamycin-resistant transformants were selected on nutrient medium and replica printed to minimal glucose medium containing serine. Colonies from the serine plates were streaked for isolation, and growth was assessed on medium with serine and medium with cysteine. Of more than 47,000 kanamycin-resistant transformants, 7 grew in the presence of serine or cysteine. Plasmids from each of the 7 transformants were isolated and reintroduced into the parental strain. After confirmation that they allowed growth, each of the plasmid inserts was sequenced.

The sequencing of the 7 plasmids identified unique inserts that overlapped with a single open reading frame (ORF), MMP0739 (Fig. 2). The plasmid with the smallest insert was designated pDM1438 and used for further characterization. The impact of MMP0739 on the growth of a ridA mutant was evaluated, and some of the results are shown in Fig. 3. Several points were taken from those data. First, MMP0739 in trans (pDM1438) restored growth to a ridA mutant in medium with either serine or cysteine present. Exogenous isoleucine or glycine similarly restored growth, consistent with the previously defined role of 2AA in the growth defect. The other 6 plasmids similarly restored growth of the ridA strain, suggesting that the MMP0739 ORF was responsible for the effect (data not shown). Two consecutive stop codons (UAA and UAA) were introduced into the coding sequence of MMP0739 in pDM1438, at residues D28 and K29. The resulting plasmid (pDM1445) failed to complement the ridA mutant, indicating that translation of the MMP0739 ORF was required for suppression (Fig. 3). The pSMART plasmid used to make the genomic library has no defined promoter (26); therefore, the expression of MMP0739 was presumed to be directed by the insert DNA. Consistent with this scenario, there was a 40-bp DNA region upstream of MMP0739 that encoded putative promoter elements, including an AT-rich sequence at the −23 to −30 positions that might include a TATA box and transcription factor B recognition element (BRE) (Fig. 2) (27, 28). Together, these data allowed the conclusion that MMP0739 was transcribed from its native promoter and translation of the MMP0739 gene product was required for functional replacement of RidA in S. enterica.

FIG 2.

Genomic context of MMP0739. A schematic of a part of the M. maripaludis chromosome is shown. Annotations based on the information provided in the BioCyc database are indicated (48). The size of ORF coding sequences and intergenic distances are indicated. The plasmid inserts are schematically represented by dark gray lines. The smallest insert was in pDM1438, and the nucleotide sequence flanking the ORF is shown in the box. Putative promoter elements contained in this insert, including a purine-rich region and box A*, are boxed.

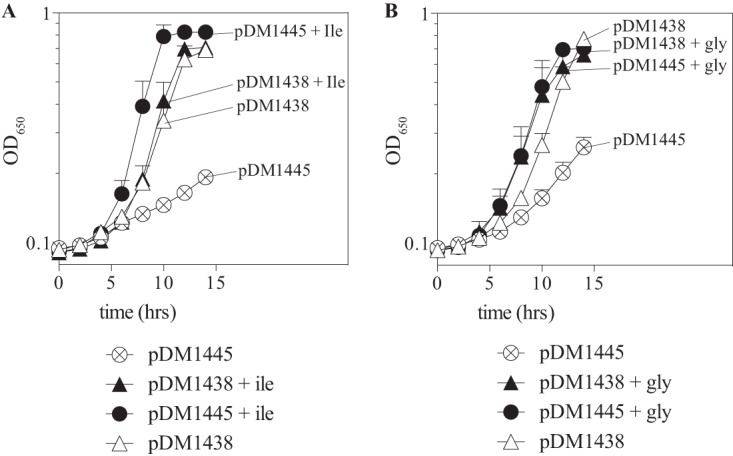

FIG 3.

MMP0739 in trans rescue of the growth defects of a ridA strain. A strain lacking ridA (DM12920) was transformed with a construct that encoded either wild-type MMP0739 (pDM1438) or variant protein MMP0739D28StopK29Stop (pDM1445). Cultures were grown in minimal glucose medium supplemented with 5 mM serine (A) or 250 μM cysteine (B). Open symbols represent growth without further supplementation, and closed symbols represent growth with isoleucine or glycine added as indicated. Growth is reported as OD650 over time. Error bars indicate standard errors of the mean for three biological replicates.

Putative aspartate/glutamate racemases substitute for RidA in vivo.

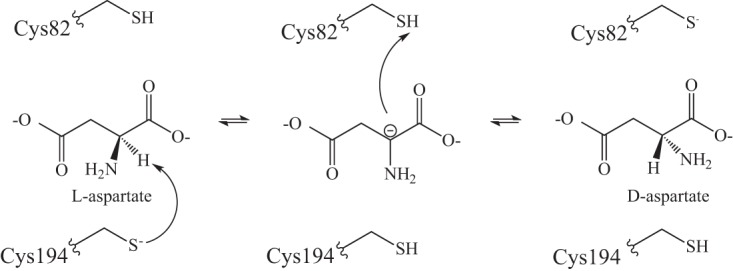

The MMP0739 gene product was annotated as a member of the aspartate/glutamate racemase superfamily (29). In contrast to many racemases, these aspartate/glutamate racemases are PLP-independent enzymes and catalyze bidirectional racemization using a “two-base” mechanism that typically involves two active-site cysteinyl residues (30–34). In this proposed mechanism, the pair of cysteines deprotonate and reprotonate the substrate on opposite faces, to produce both stereoisomers (Fig. 4). Enzymes of this class from Pyrococcus horikoshii (35), Desulfurococcus (36), Bifidobacterium bifidum (37), and Streptococcus thermophilus (30) have been characterized in vitro. Escherichia coli contains two PLP-independent racemases. MurI, a reversible glutamate racemase involved in peptidoglycan biosynthesis (31, 38), is a member of this family and is 19% identical to MMP0739. MurI has been extensively characterized in vitro and in vivo (32, 39). E. coli YgeA (48% identical to MMP0739) is also a member of this family and, by one report, has racemase activity with aspartate and glutamate (40). S. enterica contains MurI and YgeA, as well as two ORFs annotated as putative PLP-independent mandelate racemases (STM3697 and STM3833).

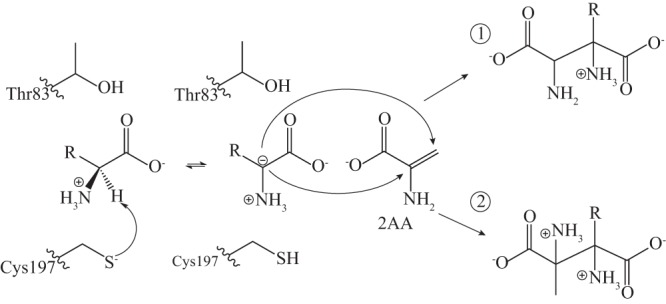

FIG 4.

PLP-independent racemase mechanism. The bidirectional PLP-independent racemase mechanism is shown with the substrate l-aspartate. The active site contains two cysteinyl residues, which catalyze bidirectional conversion of aspartate and glutamate stereoisomers (30–33). In a reversible mechanism, one cysteinyl residue (i.e., Cys194) abstracts a proton from the amino acid substrate, generating an intermediate with a carbanion. The second cysteinyl residue (i.e., Cys82) protonates the intermediate from the opposite face, resulting in formation of the antipodal stereoisomer. Catalytic residues are numbered with respect to the P. horikoshii aspartate racemase AspR (33).

Proteins from E. coli and S. enterica were tested to determine whether multicopy suppression of ridA mutant phenotypes was a common characteristic of the PLP-independent racemase family that included MMP0739. Plasmids from the ASKA collection of pCA24N isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG)-inducible vectors (41) harboring E. coli murI or ygeA were introduced into a ridA mutant strain of S. enterica (DM12920), and growth of the resulting strains was assessed. Plasmid pCA24N-ygeA, but not plasmid pCA24N-murI, restored growth of a ridA strain in the presence of serine or cysteine when expression of the gene was induced (Fig. 5). Control experiments showed that plasmid pCA24N-murI complemented the d-glutamate auxotrophy of an E. coli murI mutant strain (WM335), confirming that a functional protein was made (data not shown) (42, 43). Neither plasmid pDM1438 nor plasmid pCA24N-ygeA complemented the auxotrophy of WM335, suggesting that neither MMP0739 nor YgeA had significant l-glutamate to d-glutamate racemase activity. It was formally possible that a product of the presumed racemase activity mediated the complementation. However, exogenous glutamate/aspartate stereoisomers failed to reverse growth defects of a ridA mutant strain, minimizing this possibility. The requirement for overexpression suggests that a side reaction or moonlighting activity of YgeA could be involved in the suppression of S. enterica ridA mutant phenotypes.

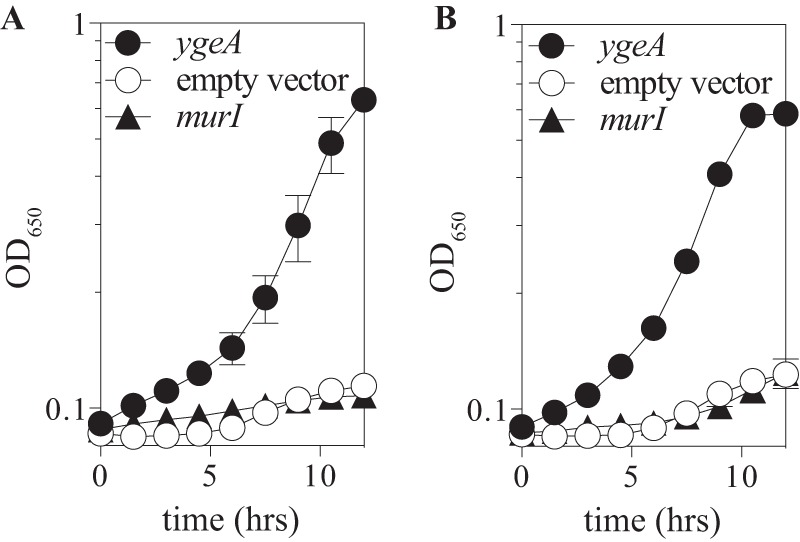

FIG 5.

ygeA complementation of a ridA mutant strain. Strains lacking ridA were transformed with pCA24N plasmids harboring E. coli ygeA, E. coli murI, or no insert (empty vector). Cultures were grown in minimal glucose medium containing 0.5 mM IPTG and 5 mM serine (A) or 250 μM cysteine (B). Error bars indicate standard errors for three biological replicates.

Presumed active-site residues are required for suppression.

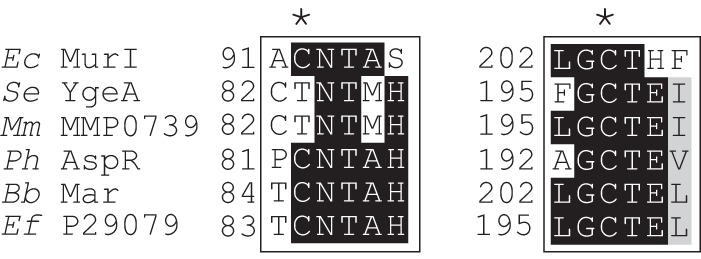

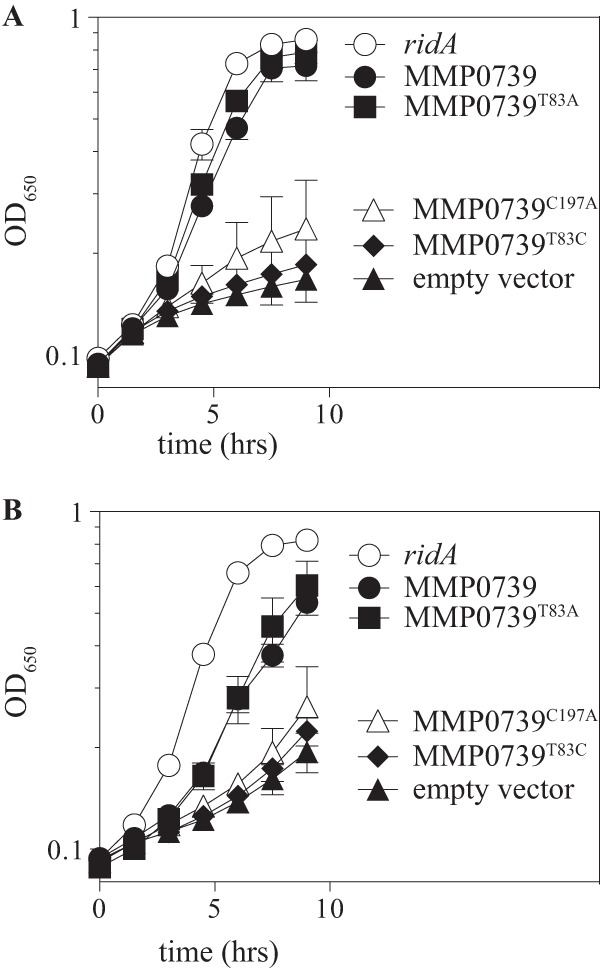

YgeA and MMP0739 differ from the more well-characterized members of the PLP-independent racemase family in that they contain a single conserved cysteine residue in the presumed active site (Fig. 6). In these two proteins, a threonine replaces the second cysteine, a substitution that has implications for the catalytic mechanism shown in Fig. 4. E. coli variants YgeAC197S and YgeAT83C had no aspartate racemase activity in vitro (40). The requirement for these residues in substituting for RidA function was addressed with targeted mutagenesis. S. enterica YgeA is 80% identical to that of E. coli, and variants of this protein were constructed and tested in vivo in complementation assays. Unlike wild-type ygeA strains, neither variant supported growth of a ridA mutant strain in the presence of serine or cysteine (data not shown). MMP0739 has high levels of identity to YgeA surrounding the active site, and plasmids encoding the MMP0739C197A or MMP0739T83C variants similarly failed to complement a ridA mutant strain (Fig. 7). Unexpectedly, substituting Thr83 with alanine produced different results in MMP0739 and YgeA. Expression of the MMP0739T83A variant rescued growth of a ridA strain in medium containing serine or cysteine, while expression of the YgeAT83A variant failed to complement the ridA mutant.

FIG 6.

Active-site sequence alignment of PLP-independent racemase family proteins. Regions containing the two cysteinyl residues critical for the PLP-independent racemase mechanism are shown, from an amino acid sequence alignment of E. coli MurI (GenBank accession no. P22634), S. enterica YgeA (GenBank accession no. Q8ZMA1), M. maripaludis MMP0739 (GenBank accession no. Q6LZ90), P. horikoshii aspartate racemase (AspR) (EMBL-EBI accession no. BAA29761.1) (33), Bifidobacterium bifidum monomeric aspartate racemase (Mar) (GenBank accession no. AB179841) (37), and Enterococcus faecium aspartate racemase (GenBank accession no. P29079) (49). The asterisks mark the positions of the two conserved cysteinyl residues in the current model for the catalytic mechanism.

FIG 7.

Complementation of a S. enterica ridA strain by MMP0739 variants. A strain lacking ridA (DM12920) was transformed with pBAD24 plasmids harboring M. maripaludis MMP0739, S. enterica ridA, mutant MMP0739 alleles encoding T83A, T83C, or C197A variant proteins, or no insert (empty vector). Growth was assessed in minimal glucose medium containing 0.2% arabinose and 5 mM serine (A) or 250 μM cysteine (B). Error bars represent standard errors for three biological replicates.

MMP0739 and YgeA decrease the 2AA load in a ridA mutant.

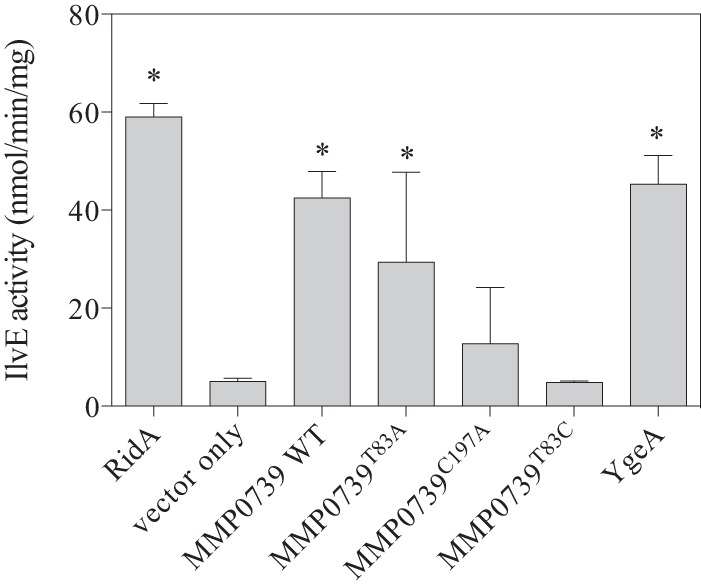

In the absence of RidA, 2AA accumulates and targets PLP-dependent enzymes, including transaminase IlvE in S. enterica. Because 2AA is unstable and cannot be measured directly, the specific activity of IlvE is used as a proxy for the 2AA burden in a strain (6). IlvE activity was assayed in crude extracts of a ridA mutant strain expressing ridA, MMP0739, or ygeA in trans (Fig. 8). The data showed that expression of RidA, MMP0739, and YgeA improved IlvE activity, with RidA allowing the highest levels. Furthermore, expression of the MMP0739T83C and MMP073C197A variant proteins failed to improve IlvE activity, consistent with their inability to complement the ridA mutant phenotypes. Importantly, MMP0739T83A produced an intermediate and statistically significant increase in IlvE activity (Fig. 8). These results correlated with the complementation data and thus were consistent with a mechanism of suppression in which an activity of MMP0739 and YgeA quenched 2AA.

FIG 8.

MMP0739 improvement of IlvE activity in a ridA strain. Strains lacking ridA (DM12920) were transformed with pBAD24 constructs encoding S. enterica RidA, wild-type (WT) MMP0739, T83C, T83A, or C197A MMP0739 variants, S. enterica YgeA, or an empty vector control. Cultures were grown in minimal medium with arabinose (0.2%), with glycerol (30 mM) as the sole carbon source, until all cultures reached full density. IlvE activity was assayed as described in the text. Error bars indicate the standard deviations for crude extracts from three biological replicates, and data are representative of at least two independent experiments. The specific IlvE activity of each strain expressing a recombinant protein was compared to the reduced activity in a ridA mutant strain with an empty vector by using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), and significant values are indicated with asterisks (P < 0.05).

Working model for multicopy suppression by MMP0739.

Members of the PLP-independent racemase family have a catalytic mechanism that requires a dual-cysteine active site (Fig. 4). The two members of this family that substitute for RidA have a cysteine-threonine configuration, and each of these residues affects their ability to complement a ridA mutant in vivo. Our favored working model suggests that an intermediate of the racemase mechanism is involved in quenching 2AA. In this scenario, lack of the second cysteine would affect the persistence of the intermediate, allowing it to interact with the 2AA that accumulates in a ridA mutant (Fig. 9). Importantly, Thr83 is not expected to initiate the reaction and thus limits the enzyme to a unidirectional reaction. A cysteine residue at position 83 would allow a reversible reaction, as described for the PLP-independent racemase mechanism (30–33). The data presented herein, and chemical precedents, are consistent with this scenario and emphasize the potential for a metabolite-quenching mechanism to control stress caused by 2AA. In vitro assays of MMP0739 and YgeA for RidA-like enamine deaminase activity detected no activity.

FIG 9.

Working model for metabolite quenching of 2AA. Our working model for 2AA quenching through a metabolite-mediated mechanism is depicted. In this scenario, a PLP-independent racemase with a threonine-cysteine catalytic pair (i.e., MMP0739 or YgeA) catalyzes the formation of an intermediate with a carbanion from an amino acid substrate. Lack of the canonical racemase proton donor (cysteine) is likely to slow conversion of the intermediate to the substrate antipode. In this scenario, the nucleophilic carbanion attacks 2AA or iminopropionate (IP), resulting in formation of a stable adduct. Nucleophilic attack of 2AA at the β or α carbon would result in the formation of distinct products, with one or two quaternary carbon atoms, respectively.

Conclusions.

The growth defect of a ridA strain of S. enterica is caused by the accumulation of 2AA, which leads to the collective inactivation of PLP-dependent enzymes There are two general ways to bypass the growth defect of a ridA mutant, i.e., (i) reduce the accumulation of 2AA or (ii) absorb the defect by altering flux through the metabolic network (17); the latter allows growth without decreasing the 2AA load in the cell. This study showed that expression of two members of an aspartate/glutamate racemase family with a cysteine-threonine catalytic pair (i.e., MMP0739 and YgeA) can reduce the 2AA burden of a cell. While the current data do not differentiate between direct and indirect roles for these proteins in reducing 2AA, we favor a mechanism in which the carbanion of an intermediate generated by the putative racemase reacts with 2AA or the imine tautomer iminopropionate (IP) to form a stable molecule (Fig. 9). Such a scenario could involve the predicted (aspartate/glutamate) or a noncanonical amino acid substrate of these enzymes. Significantly, these possibilities are not trivial to address with in vitro approaches, given the short half-life of 2AA (1) and the difficulty of detecting YgeA or MMP0739 activity in vitro. Characterization of the RidA paradigm in S. enterica provided precedent for the difficulty of making conclusions about cellular biochemistry solely from in vitro data. In particular, the work emphasized that results can be misleading regarding the cellular milieu in the case of low-level, reactive metabolites, due to the use of aqueous solutions (1). Current methods to detect 2AA damage rely on monitoring of one of the four known damaged enzymes. Sensitive techniques to quantify or to track 2AA in an untargeted manner are needed. In summary, the results herein suggest that cells can control reactive metabolites not only through the Rid paradigm of enzymatic quenching but also through production of molecules that themselves quench rogue metabolites. Emerging technologies in metabolomics, when pursued in the context of genetic and phenotypic analyses, will facilitate increased understanding of the subtleties of metabolism and the strategies that have evolved to control metabolic stress.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, chemicals, and media.

All strains used in this study are derivatives of S. enterica serovar Typhimurium LT2 and are described with relevant plasmids in Table 1. Primers used to construct plasmids are listed in Table 2. Tn10d(Tc) refers to the transposition-deficient mini-Tn10 (44). Difco nutrient broth (NB) (8 g/liter) with NaCl (5 g/liter) was used as a rich medium for S. enterica, and lysogeny broth (LB) was used for E. coli. No-carbon E salts (NCE) medium (45) supplemented with MgSO4 (1 mM) and trace minerals (46), with glucose (11 mM) or pyruvate (50 mM), served as minimal medium. Solid medium contained Difco agar (15 g/liter). When indicated, supplements were present at the following concentrations unless indicated otherwise: serine, 5 mM; isoleucine, 0.3 mM; cysteine, 250 μM; glycine, 1 mM; kanamycin, 50 mg/liter; ampicillin, 150 mg/liter; chloramphenicol, 20 mg/liter. Kanamycin and Tris were purchased from Amresco (Solon, OH), and all other chemicals were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids

| Designation | Relevant genotypea | Description | Derived from |

|---|---|---|---|

| S. enterica strainsb | |||

| DM12920 | ridA1::Tn10d(Tc) | ||

| DM14941 | ridA1::Tn10d(Tc) pDM1438 | M. maripaludis DNA fragment | pSMART HC-Kan |

| DM14966 | ridA1::Tn10d(Tc) pDM1445 | UAA UAA stop codon | pSMART HC-Kan |

| DM15396 | ridA1::Tn10d(Tc) pCA24N-ygeA (gfp) | E. coli ygeA | ASKA collection (41) |

| DM15397 | ridA1::Tn10d(Tc) pCA24N | Empty vector | ASKA collection (41) |

| DM15398 | ridA1::Tn10d(Tc) pCA24N-murI (gfp) | E. coli murI | ASKA collection (41) |

| DM14846 | ridA1::Tn10d(Tc) pDM1439 | S. enterica ridA | pBAD24 |

| DM14847 | ridA1::Tn10d(Tc) | Empty vector | pBAD24 |

| DM15862 | ridA1::Tn10d(Tc) pDM1528 | MMP0739 (codon optimized) T83A | pBAD24 |

| DM15780 | ridA1::Tn10d(Tc) pDM1520 | MMP0739 (codon optimized) | pBAD24 |

| DM15863 | ridA1::Tn10d(Tc) pDM1529 | MMP0739 (codon optimized) C197A | pBAD24 |

| DM15865 | ridA1::Tn10d(Tc) pDM1531 | MMP0739 (codon optimized) T83C | pBAD24 |

| DM15483 | ridA1::Tn10d(Tc) pDM1475 | S. enterica ygeA | pBAD24 |

| DM15932 | ridA1::Tn10d(Tc) pDM1493 | S. enterica ygeA601 T83C | pBAD24 |

| DM15933 | ridA1::Tn10d(Tc) pDM1494 | S. enterica ygeA602 T83A | pBAD24 |

| DM15934 | ridA1::Tn10d(Tc) pDM1495 | S. enterica ygeA603 C197A | pBAD24 |

| Plasmids | |||

| pSMART HC-Kan | High-copy-number, blunt-cloning vector, kan+ (Lucigen) | ||

| pBAD24 (pCV1) | ParaBAD expression vector, bla+ (47) |

Tn10d(Tc) refers to the transposition-defective mini-Tn10 (Tn10Δ16Δ17).

Salmonella enterica strains are derivatives of S. enterica serovar Typhimurium LT2.

TABLE 2.

Primers

| Primer no. | Name | Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| SL1 | CAGTCCAGTTACGCTGGAGTC (Lucigen) | |

| SR2 | GGTCAGGTATGATTTAAATGGTCAGT (Lucigen) | |

| pBAD_F | ATGCCATAGCATTTTTATCC (Eton Biosciences) | |

| pBAD_R | GATTTAATCTGTATCAGG (Eton Biosciences) | |

| PR309 | MMP0739 stop F | TTTTGCTGAATGGGGAGCTCCAAGTTATTATCTAATCGATTGATTTATAATTCGATAGT |

| PR310 | MMP0739 stop R | ACTATCGAATTATAAATCAATCGATTAGATAATAACTTGGAGCTCCCCATTCAGCAAAA |

| PR617 | ygeA for pBAD24 F | NNGCTCTTCNTTCATGGTGAAAACGATCGGACTGTTG |

| PR618 | ygeA for pBAD24 R | NNGCTCTTCNTTATTATTCTGGGGCCGATGA |

| PR696 | YgeA Thr83Ala 5′ | GCATGGTGTTGGCACACAGCACAATGCCTTCTGCG |

| PR697 | YgeA Thr83Ala 3′ | CGCAGAAGGCATTGTGCTGTGTGCCAACACCATGC |

| PR698 | YgeA Thr83Cys 5′ | CGATTTTATGCATGGTGTTGCAACACAGCACAATGCCTTCTG |

| PR699 | YgeA Thr83Cys 3′ | CAGAAGGCATTGTGCTGTGTTGCAACACCATGCATAAAATCG |

| PR700 | YgeA Cys197Ala 5′ | CGCAGGGCGTTATTTTTGGCGCTACTGAAATAGGTTTGCTTG |

| PR701 | YgeA Cys197Ala 3′ | CAAGCAAACCTATTTCAGTAGCGCCAAAAATAACGCCCTGCG |

| PR884 | MMP0739 CO pBAD F | NNGCTCTTCNTTCATGAAAACCATCGGTCTGATCG |

| PR886 | MMP0739 CO pBAD F | NNGCTCTTCNTTATCACAGTTTGCTATCTTTCAGAACG |

| PR901 | MMP0739 CO T83A F | GTGTGCATGGTGTTGGCGCAAATCAGGATGCCT |

| PR902 | MMP0739 CO T83A R | AGGCATCCTGATTTGCGCCAACACCATGCACAC |

| PR903 | MMP0739 CO T83C 5′ | CGGTGTGCATGGTGTTGCAGCAAATCAGGATGCCTT |

| PR904 | MMP0739 CO T83C 3′ | AAGGCATCCTGATTTGCTGCAACACCATGCACACCG |

| PR905 | MMP0739 CO C197A 5′ | GCATCATTCTGGGCGCCACCGAGATCCCGC |

| PR906 | MMP0739 CO C197A 3′ | GCGGGATCTCGGTGGCGCCCAGAATGATGC |

Growth analyses in liquid medium were performed in 96-well microtiter plates in a BioTek ELx808 plate reader. S. enterica cultures grown to full density in NB (2 ml) were used to inoculate the indicated medium (2.5% inoculum). Plates were incubated at 37°C, with shaking, and growth was measured as the change in optical density at 650 nm (OD650). Strains were grown in triplicate, and error bars shown indicate the standard error of the mean. Growth curves were plotted and statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 6.0g.

Genomic library construction.

A Methanococcus maripaludis library was generated using blunt cloning and the commercially available HC-Kan pSMART vector (Lucigen). Genomic DNA (18 μg) was prepared in Tris-EDTA (TE) buffer (pH 8.0) containing glycerol (10%) and was sheared in 30-s intervals using a nebulizer (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer's protocol. Following each nebulizer treatment, a sample of DNA (5 μl) was run on a 1% agarose gel. After a total treatment time of 120 s, the DNA fragments ranged from 1 to 3 kb in size. Sheared DNA was isolated via ethanol precipitation, and a total of 14 μg was recovered. Blunt ends were repaired using the DNATerminator end repair kit (Lucigen), and DNA was again isolated via ethanol precipitation. Ligation reactions and subsequent transformations into competent cells were performed as described in the CloneSMART blunt cloning kit manual (Lucigen). Briefly, 20 reaction mixtures (10 μl each), containing end-repaired DNA (500 ng), CloneSMART vector premix, and CloneSMART DNA ligase, were prepared and then were kept at room temperature for 30 min. Aliquots of ligation mixture (4 μl) were transformed into batches of electrocompetent E. cloni cells (25 μl) and transferred to the recovery medium supplied with the CloneSMART kit. Cells were incubated for 1 h at 37°C before being plated on LB medium containing kanamycin.

Transformations were continued until a minimum of 47,000 clones were obtained. Based on the number of clones isolated from control transformations without insert DNA, it was concluded that 23,500 clones in the library should contain a fragment of M. maripaludis DNA. The M. maripaludis genome is 1.7 Mb in size and contains 1,722 protein-encoding genes (29); therefore, the library achieved 14-fold coverage. Batches of 1,000 to 2,000 colonies were pooled in LB, aliquoted into cryovials containing dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), and stored at −80°C. Scrapings from each vial were used to inoculate LB (5 ml) containing kanamycin, and plasmid DNA was isolated from these cultures using E.Z.N.A. plasmid midi kits (Omega, Norcross, GA).

Subcloning of MMP0739 codon-optimized allele.

An MMP0739 allele was codon optimized for expression in Escherichia coli, synthesized, and cloned into pET28a at NheI and EcoRI restriction sites by GenScript (Piscataway, NJ). The resulting plasmid was designated pDM1516 and was used as the template in PCR. The cloned portion of DNA was amplified using primers PR844 and PR846, which yielded amplification of the stop codon and introduced BspQI cut sites but did not include any His6 or T7 tags. A digested PCR product was ligated into a pBAD24 vector modified to include a BspQI cut site (pCV1), as described previously (47). The resulting plasmid was named pDM1520, and the insert was confirmed by sequencing (Eton Bioscience Inc., San Diego, CA).

Construction of site-directed mutations.

Site-directed mutagenic primers were designed using the Agilent QuikChange primer design tool. Amplification reaction mixtures (50 μl) contained template DNA (100 ng), primers (250 nM), deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs) (250 nM), DMSO (1 μl), Pfu Ultra reaction buffer (5 μl), and Pfu Ultra II polymerase (1 μl). An extension time of 2.5 min per kilobase of the entire plasmid was used. A gradient spanning ±5°C of the estimated melting temperature was used for each primer pair, and the samples were pooled before digestion with DpnI (1 μl) for 8 h. The digested sample (5 μl) was transformed into electrocompetent E. coli DH5α cells. Plasmid DNA was harvested from colonies growing on LB containing the appropriate drug, and mutations were confirmed by sequence analysis performed by Eton Bioscience.

Isoleucine transaminase activity assay.

Isoleucine transaminase activity was measured using permeabilized cells, as described previously (16). Freshly revived strains were used to start overnight cultures, for optimal growth of strains harboring constructs with active racemases. Cultures were grown in minimal NCE medium (5 ml) containing ampicillin (15 mg/liter) and arabinose (0.2%), with glycerol (30 mM) as the sole carbon source. When cultures reached full density, cells were pelleted and washed in NCE medium; pellets were kept at −20°C until they were assayed. Cell pellets were resuspended in 250 μl of potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5). Reaction mixtures (180 μl) contained cell resuspension (50 μl), PLP (50 μM), PopCulture reagent (20 μl), and α-ketoglutarate (10 mM). Mixtures were incubated at 37°C for 10 min prior to the addition of 0.2 M isoleucine (20 μl). After 20 min, reactions were quenched with the addition of 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine (DNPH) (200 μl) to derivatize the product 2-ketomethylvalerate (2KMV). Samples were incubated for 2 min at 37°C, subjected to organic extraction with toluene (1 ml), and washed with 0.5 N HCl. An aliquot (700 μl) of the top layer was mixed with 1.5 N NaOH to promote chromophore formation. Two hundred microliters of the aqueous layer containing the chromophore was removed, and the absorbance at 540 nm was measured using a SpectraMax Plus 384 microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Chromophore concentrations were determined via comparison to a standard curve of 2KMV extractions. An aliquot (25 μl) of resuspended cells was lysed with PopCulture reagent, and the total protein content was determined using the Pierce bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Activity is given in nanomoles of 2KMV produced per minute per milligram of total cellular protein.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Robert S. Phillips and Michael Thomas for helpful discussions regarding the proposed mechanism of suppression and William Whitman for M. maripaludis S2 genomic DNA and discussions about archaeal genetics and physiology. We also acknowledge Jorge Escalante-Semerena for making the ASKA clones pCA24N-ygeA and pCA24N-murI available to us.

This work was supported by competitive grant GM095837 from the National Institutes of Health (to D.M.D.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Lambrecht JA, Flynn JM, Downs DM. 2012. Conserved YjgF protein family deaminates reactive enamine/imine intermediates of pyridoxal 5′-phosphate (PLP)-dependent enzyme reactions. J Biol Chem 287:3454–3461. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.304477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Niehaus TD, Gerdes S, Hodge-Hanson K, Zhukov A, Cooper AJ, ElBadawi-Sidhu M, Fiehn O, Downs DM, Hanson AD. 2015. Genomic and experimental evidence for multiple metabolic functions in the RidA/YjgF/YER057c/UK114 (Rid) protein family. BMC Genomics 16:382. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1584-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hodge-Hanson KM, Downs DM. 2017. Members of the Rid protein family have broad imine deaminase activity and can accelerate the Pseudomonas aeruginosa D-arginine dehydrogenase (DauA) reaction in vitro. PLoS One 12:e0185544. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0185544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Enos-Berlage JL, Langendorf MJ, Downs DM. 1998. Complex metabolic phenotypes caused by a mutation in yjgF, encoding a member of the highly conserved YER057c/YjgF family of proteins. J Bacteriol 180:6519–6528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Christopherson MR, Schmitz GE, Downs DM. 2008. YjgF is required for isoleucine biosynthesis when Salmonella enterica is grown on pyruvate medium. J Bacteriol 190:3057–3062. doi: 10.1128/JB.01700-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lambrecht JA, Schmitz GE, Downs DM. 2013. RidA proteins prevent metabolic damage inflicted by PLP-dependent dehydratases in all domains of life. mBio 4:e00033-13. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00033-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Downs DM, Ernst DC. 2015. From microbiology to cancer biology: the Rid protein family prevents cellular damage caused by endogenously generated reactive nitrogen species. Mol Microbiol 96:211–219. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Niehaus TD, Nguyen TN, Gidda SK, ElBadawi-Sidhu M, Lambrecht JA, McCarty DR, Downs DM, Cooper AJ, Fiehn O, Mullen RT, Hanson AD. 2014. Arabidopsis and maize RidA proteins preempt reactive enamine/imine damage to branched-chain amino acid biosynthesis in plastids. Plant Cell 26:3010–3022. doi: 10.1105/tpc.114.126854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flynn JM, Christopherson MR, Downs DM. 2013. Decreased coenzyme A levels in ridA mutant strains of Salmonella enterica result from inactivated serine hydroxymethyltransferase. Mol Microbiol 89:751–759. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flynn JM, Downs DM. 2013. In the absence of RidA, endogenous 2-aminoacrylate inactivates alanine racemases by modifying the pyridoxal 5′-phosphate cofactor. J Bacteriol 195:3603–3609. doi: 10.1128/JB.00463-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ernst DC, Anderson ME, Downs DM. 2016. L-2,3-Diaminopropionate generates diverse metabolic stresses in Salmonella enterica. Mol Microbiol 101:210–223. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schnackerz KD, Ehrlich JH, Giesemann W, Reed TA. 1979. Mechanism of action of d-serine dehydratase: identification of a transient intermediate. Biochemistry 18:3557–3563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Datta P, Bhadra R. 1978. Biodegradative threonine dehydratase: reduction of ferricyanide by an intermediate of the enzyme-catalyzed reaction. Eur J Biochem 91:527–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Phillips AT, Wood WA. 1965. The mechanism of action of 5′-adenylic acid-activated threonine dehydratase. J Biol Chem 240:4703–4709. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chargaff E, Sprinson DB. 1943. Studies on the mechanism of deamination of serine and threonine in biological systems. J Biol Chem 151:273–280. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schmitz G, Downs DM. 2004. Reduced transaminase B (IlvE) activity caused by the lack of yjgF is dependent on the status of threonine deaminase (IlvA) in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J Bacteriol 186:803–810. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.3.803-810.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ernst DC, Downs DM. 2016. 2-Aminoacrylate stress induces a context-dependent glycine requirement in ridA strains of Salmonella enterica. J Bacteriol 198:536–543. doi: 10.1128/JB.00804-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leitner-Dagan Y, Ovadis M, Zuker A, Shklarman E, Ohad I, Tzfira T, Vainstein A. 2006. CHRD, a plant member of the evolutionarily conserved YjgF family, influences photosynthesis and chromoplastogenesis. Planta 225:89–102. doi: 10.1007/s00425-006-0332-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oxelmark E, Marchini A, Malanchi I, Magherini F, Jaquet L, Hajibagheri MA, Blight KJ, Jauniaux JC, Tommasino M. 2000. Mmf1p, a novel yeast mitochondrial protein conserved throughout evolution and involved in maintenance of the mitochondrial genome. Mol Cell Biol 20:7784–7797. doi: 10.1128/MCB.20.20.7784-7797.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim J-M, Yoshikawa H, Shirahige K. 2001. A member of the YER057c/yjgf/Uk114 family links isoleucine biosynthesis and intact mitochondria maintenance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Cells 6:507–517. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2001.00443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Accardi R, Oxelmark E, Jauniaux N, de Pinto V, Marchini A, Tommasino M. 2004. High levels of the mitochondrial large ribosomal subunit protein 40 prevent loss of mitochondrial DNA in null mmf1 Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells. Yeast 21:539–548. doi: 10.1002/yea.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kreuzer-Martin HW, Lott MJ, Ehleringer JR, Hegg EL. 2006. Metabolic processes account for the majority of the intracellular water in log-phase Escherichia coli cells as revealed by hydrogen isotopes. Biochemistry 45:13622–13630. doi: 10.1021/bi0609164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Christopherson MR, Lambrecht JA, Downs D, Downs DM. 2012. Suppressor analyses identify threonine as a modulator of ridA mutant phenotypes in Salmonella enterica. PLoS One 7:e43082. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Danchin A. 2017. Coping with inevitable accidents in metabolism. Microb Biotechnol 10:57–72. doi: 10.1111/1751-7915.12461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ernst DC, Lambrecht JA, Schomer RA, Downs DM. 2014. Endogenous synthesis of 2-aminoacrylate contributes to cysteine sensitivity in Salmonella enterica. J Bacteriol 196:3335–3342. doi: 10.1128/JB.01960-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McFarland KN, Liu J, Landrian I, Godiska R, Shanker S, Yu F, Farmerie WG, Ashizawa T. 2015. SMRT sequencing of long tandem nucleotide repeats in SCA10 reveals unique insight of repeat expansion structure. PLoS One 10:e0135906. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0135906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pu YG, Jiang YL, Ye XD, Ma XX, Guo PC, Lian FM, Teng YB, Chen Y, Zhou CZ. 2011. Crystal structures and putative interface of Saccharomyces cerevisiae mitochondrial matrix proteins Mmf1 and Mam33. J Struct Biol 175:469–474. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2011.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang J, Li E, Olsen GJ. 2009. Protein-coding gene promoters in Methanocaldococcus (Methanococcus) jannaschii. Nucleic Acids Res 37:3588–3601. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hendrickson EL, Kaul R, Zhou Y, Bovee D, Chapman P, Chung J, Conway de Macario E, Dodsworth JA, Gillett W, Graham DE, Hackett M, Haydock AK, Kang A, Land ML, Levy R, Lie TJ, Major TA, Moore BC, Porat I, Palmeiri A, Rouse G, Saenphimmachak C, Soll D, Van Dien S, Wang T, Whitman WB, Xia Q, Zhang Y, Larimer FW, Olson MV, Leigh JA. 2004. Complete genome sequence of the genetically tractable hydrogenotrophic methanogen Methanococcus maripaludis. J Bacteriol 186:6956–6969. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.20.6956-6969.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamauchi T, Choi SY, Okada H, Yohda M, Kumagai H, Esaki N, Soda K. 1992. Properties of aspartate racemase, a pyridoxal 5′-phosphate-independent amino acid racemase. J Biol Chem 267:18361–18364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Glavas S, Tanner ME. 2001. Active site residues of glutamate racemase. Biochemistry 40:6199–6204. doi: 10.1021/bi002703z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yoshimura T, Esak N. 2003. Amino acid racemases: functions and mechanisms. J Biosci Bioeng 96:103–109. doi: 10.1016/S1389-1723(03)90111-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ohtaki A, Nakano Y, Iizuka R, Arakawa T, Yamada K, Odaka M, Yohda M. 2008. Structure of aspartate racemase complexed with a dual substrate analogue, citric acid, and implications for the reaction mechanism. Proteins 70:1167–1174. doi: 10.1002/prot.21528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu X, Gao F, Ma Y, Liu S, Cui Y, Yuan Z, Kang X. 2016. Crystal structure and molecular mechanism of an aspartate/glutamate racemase from Escherichia coli O157. FEBS Lett 590:1262–1269. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.12148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu L, Iwata K, Kita A, Kawarabayasi Y, Yohda M, Miki K. 2002. Crystal structure of aspartate racemase from Pyrococcus horikoshii OT3 and its implications for molecular mechanism of PLP-independent racemization. J Mol Biol 319:479–489. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00296-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yohda M, Endo I, Abe Y, Ohta T, Iida T, Maruyama T, Kagawa Y. 1996. Gene for aspartate racemase from the sulfur-dependent hyperthermophilic archaeum, Desulfurococcus strain SY. J Biol Chem 271:22017–22021. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.36.22017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yamashita T, Ashiuchi M, Ohnishi K, Kato S, Nagata S, Misono H. 2004. Molecular identification of monomeric aspartate racemase from Bifidobacterium bifidum. Eur J Biochem 271:4798–4803. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.2004.04445.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Doublet P, van Heijenoort J, Bohin JP, Mengin-Lecreulx D. 1993. The murI gene of Escherichia coli is an essential gene that encodes a glutamate racemase activity. J Bacteriol 175:2970–2979. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.10.2970-2979.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fisher SL. 2008. Glutamate racemase as a target for drug discovery. Microb Biotechnol 1:345–360. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7915.2008.00031.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ahn JW, Chang JH, Kim KJ. 2015. Structural basis for an atypical active site of an l-aspartate/glutamate-specific racemase from Escherichia coli. FEBS Lett 589:3842–3847. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2015.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kitagawa M, Ara T, Arifuzzaman M, Ioka-Nakamichi T, Inamoto E, Toyonaga H, Mori H. 2005. Complete set of ORF clones of Escherichia coli ASKA library (a complete set of E. coli K-12 ORF archive): unique resources for biological research. DNA Res 12:291–299. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsi012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lugtenberg EJJ, Wijsman HJW, Van Zaane D. 1973. Properties of a d-glutamic acid-requiring mutant of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 114:499–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Doublet P, van Heijenoort J, Mengin-Lecreulx D. 1992. Identification of the Escherichia coli murI gene, which is required for the biosynthesis of d-glutamic acid, a specific component of bacterial peptidoglycan. J Bacteriol 174:5772–5779. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.18.5772-5779.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Way JC, Davis MA, Morisato D, Roberts DE, Kleckner N. 1984. New Tn10 derivatives for transposon mutagenesis and for construction of lacZ operon fusions by transposition. Gene 32:369–379. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(84)90012-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vogel HJ, Bonner DM. 1956. Acetylornithase of Escherichia coli: partial purification and some properties. J Biol Chem 218:97–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Balch WE, Wolfe RS. 1976. New approach to the cultivation of methanogenic bacteria: 2-mercaptoethanesulfonic acid (HS-CoM)-dependent growth of Methanobacterium ruminantium in a pressurized atmosphere. Appl Environ Microbiol 32:781–791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.VanDrisse CM, Escalante-Semerena JC. 2016. New high-cloning-efficiency vectors for complementation studies and recombinant protein overproduction in Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica. Plasmid 86:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.plasmid.2016.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Caspi R, Billington R, Ferrer L, Foerster H, Fulcher CA, Keseler IM, Kothari A, Krummenacker M, Latendresse M, Mueller LA, Ong Q, Paley S, Subhraveti P, Weaver DS, Karp PD. 2016. The MetaCyc database of metabolic pathways and enzymes and the BioCyc collection of pathway/genome databases. Nucleic Acids Res 44:D471–D480. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yohda M, Okada H, Kumagai H. 1991. Molecular cloning and nucleotide sequencing of the aspartate racemase gene from lactic acid bacteria Streptococcus thermophilus. Biochim Biophys Acta 1089:234–240. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(91)90013-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ernst DC, Downs DM. 2018. Mmf1p couples amino acid metabolism to mitochrondrial DNA maintenance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. mBio 9:e00084-18. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00084-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]