Abstract

The human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT) gene encodes an enzyme responsible for maintaining the integrity of chromosomal ends. hTERT plays a key role in cellular immortalization, tumorigenesis and the progression of cancer. Previously, we reported that hTERT repression is required for the induction of cellular senescence. Thus, transcriptional regulation mechanisms of the hTERT gene may be related to the mechanisms of cellular senescence. In the present study, we clarified the molecular mechanism of hTERT repression by protein kinase C (PKC)-δ, one of the cellular senescence-inducing factors. The results showed that a repressor complex composed of NFX1-91, mSin3A and histone deacetylase 1 was involved in the PKC-δ-induced repression of the hTERT promoter, which resulted in the repression of hTERT transcription. These results suggest that targeted recruitment of the NFX1-91 complex to the hTERT promoter is a potential mechanism for repressing hTERT transcription and further inducing cellular senescence.

Keywords: hTERT, histone deacetylase 1(HDAC), NFX1-91, PKC-δ, transcription

The human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT) plays a key role in maintenance of telomere ends. The augmented expression of hTERT is required for cellular immortalization in cancer cells. Expression of hTERT is mainly regulated at the transcriptional level, where a large number of transcriptional factors and histone acetylation status are related to the regulation of the hTERT promoter (1–3). We have reported that cellular senescence-inducing factors, including TAK1 and p38, repress the hTERT promoter (3, 4). Other reports suggest a critical role for protein kinase C (PKC)-δ in cellular senescence (5).

PKC-δ represses the transcription of several growth-associated genes by inactivating the serum response factor (SRF), a major transcriptional activator of the immediate-early gene promoter, which contributes to the senescence phenotype (6). Furthermore, reactive oxygen species (ROS) activate PKC-δ that then further promotes the generation of ROS in senescent cells. This forms a positive feedback loop to sustain ROS-PKC-δ signaling, which irreversibly blocks cytokinesis and further cell-cycling in senescent cells (5). In addition, we reported that PKC-δ represses the transcription of hTERT as well as induces cellular senescence (7). Inhibition of PKC-δ in senescent human fibroblasts restores the transcription of hTERT, suggesting that PKC-δ induces cellular senescence by repressing hTERT transcription in human cells. Thus, in the present study, we clarified the molecular mechanisms for PKC-δ-induced repression of hTERT transcription.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines

A549 cells (Riken Bioresource Center, Tsukuba, Japan) were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Nissui, Tokyo, Japan) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) at 37 °C in 5% CO2.

Promoter assay

pGL3-Basic (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) containing the hTERT core promoter (–289 to –25) (phTERT-289), mutant hTERT core promoter with two disrupted E-box elements (phTERT-289EM) (3), and vectors containing the human c-MYC promoter were used as reporters. pc-MYC-DEL1/DEL4 contain nested deletion fragments of c-MYC promoter upstream of the luciferase gene (8). A549 cells (1.25 × 105) were seeded onto 24-well plates. DNA fragments for PKC-δ and kinase negative PKC-δ (KN) were prepared from δ-PKC and TB701/HA–PKC-δ-KN (generous gifts from N. Saito and Y. Ono, Kobe University) (9), and inserted into pcDNA3.1 (pcDNA–PKC-δ and pcDNA–PKC-δ-KN). A kinase-negative mutant of PKC-δ substitutes Lys for Ala-376 in the ATP-binding site. The following day, the cells were transfected with reporter and effector constructs using the HilyMax reagent (Dojindo Molecular Technologies, Kumamoto, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. After 48 h, a luciferase assay was performed using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega). The relative luciferase activity was calculated by dividing the firefly luciferase activity by the Renilla luciferase activity.

To evaluate the transcriptional activation ability of c-MYC, we generated GAL4-c-MYC containing a full-length human c-MYC cDNA (amino acids 1–440) fused to the DNA-binding domain of the yeast transcription factor GAL4 (pFA-CMV, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) (10). The luciferase assay was performed using GAL4-c-MYC and pFR-Luc (Agilent Technologies), a luciferase reporter containing five GAL4 binding sites.

Adenovirus production and transduction

Recombinant adenovirus was produced using the Adeno-X Expression System (Takara, Shiga, Japan) as described previously (11). A549 cells underwent adenoviral transduction after a 1 h infection at a multiplicity of infection of 50.

qRT-PCR

RNA was isolated using the High Pure RNA Isolation Kit (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). cDNA was prepared using the ReverTra Ace kit (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan). qRT-PCR was performed using the KAPA SYBR Fast qPCR Kit (KAPA Biosystems, Woburn, MA, USA) and the Thermal Cycler Dice Real Time System TP-800 (Takara). Samples were analysed in triplicate. The following PCR primers were employed: hTERT forward primer, 5′-CGTACAGGTTTCACGCATGTG-3′ and reverse primer, 5′-ATGACGCGCAGGAAAAATG-3′: human c-MYC forward primer, 5′-CGGATTCTCTGCTCTCCTCGAC-3′ and reverse primer, 5′-CCTCCAGCAGAAGGTGATCCA-3′; human β-actin forward primer, 5′-TGGCACCCAGCACAATGAA-3′ and reverse primer, 5′-CTAAGTCATAGTCCGCCTAGAAGCA-3′; human mSin3A forward primer, 5′-AATTTCGCTTGGACAACACC-3′ and reverse primer, 5′-AATTGGAACAGCAATGGAGG-3′; human NFX1-91 forward primer, 5′-CATGCTCTCGCACATCAGTT-3′ and reverse primer, 5′-ACCGTTTCTTGTTACACCGC-3′.

ChIP assay

The ChIP assay was performed using a kit (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) as described previously (11). Briefly, cells were cross-linked with formaldehyde and the cell pellets resuspended in sodium dodecyl sulfate lysis buffer. The sonicated chromatin solution was incubated overnight at 4 °C with either the anti-acetyl-histone H3 (06–599, EMD Millipore), anti-HDAC 1 (06–720, EMD Millipore), anti-c-MYC (sc-764, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), anti-mSin3A (ab34559, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), or anti-NFX1-91 (12) antibodies. Rabbit IgG (#3900S, Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, USA) was used as the control. The immune complexes were collected using salmon sperm DNA/protein A agarose and eluted with elution buffer. Crosslinkage was reversed by heating samples at 65 °C for 6 h, followed by treatment with proteinase K at 45 °C for 60 min.

DNA was used as a template for PCR to amplify the target site in the hTERT promoter. The target sites and the corresponding primer sequences were as follows: hTERT 5′-GGCCGGGCTCCCAGTGGATTCG-3′ (−293 to −272) and 5′-CAGCGGGGAGCGCGCGGCATCG-3′ (+20 to −2). The relative amounts of PCR product amplified from the ChIP assay were normalized to the input DNA and calculated as described previously (11).

Short hairpin RNA

Oligonucleotides containing the siRNA-expressing sequences targeting mSin3A and NFX1-91 were annealed (shmSin3A-1 top: 5′-GATCCCCGGAAACTACACTCCAGCATTGTTCGAAGAGCAATGCTGGAGTGTAGTTTCCTTTTTA-3′, shmSin3A-1 bottom: 5′-AGCTTAAAAAGGAAACTACACTCCAGCATTGCTCTTCGAACAATGCTGGAGTGTAGTTTCCGGG-3′; shmSin3A-2 top: 5′-GATCCCCGGATTCTTCTATGGCAGATGCTTCGAAGAGGCATCTGCCATAGAAGAATCCTTTTTA-3′ and shmSin3A-2 bottom: 5′-AGCTTAAAAAGGATTCTTCTATGGCAGATGCCTCTTCGAAGCATCTGCCATAGAAGAATCCGGG-3′; shNFX1-91-1 top: 5′-GATCCCCTGTGGAACCAGCCCAACTGCCCATCAGTCAATTCGAAGAGTTGACTGATGGGCAGTTGGGCTGGTTCCACATTTTTA-3′ and shNFX1-91-1 bottom: 5′-AGCTTAAAAATGTGGAACCAGCCCAACTGCCCATCAGTCAACTCTTCGAATTGACTGATGGGCAGTTGGGCTGGTTCCACAGGG-3′; shNFX1-91-2 top: 5′-GATCCCCAGATACCTGCACACGCATGTTCGAAGAGCATGCGTGTGCAGGTATCTTTTTTA-3′ and shNFX1-91-2 bottom: 5′-AGCTTAAAAAAGATACCTGCACACGCATGCTCTTCGAACATGCGTGTGCAGGTATCTGGG-3′) and cloned into the pSUPER.retro vector (OligoEngine, Seattle, WA, USA). Viral supernatants were produced after transfection of 293T cells with pGag-pol, pVSV-g, and individual pSUPER.retro vectors using the HilyMax reagent (Dojindo Molecular Technologies). Viral supernatant was prepared as described previously (11), and the target cells were infected with this supernatant for 24 h at 37 °C. After infection, cells were selected with 3 μg/ml puromycin (Enzo Life Sciences, Farmingdale, NY, USA) for 3 days.

Statistical analyses

All experiments were performed at least three times, and the corresponding data are shown. The results are expressed as mean ± standard error of mean. The statistical significance was determined using a two-sided Student’s t-test. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05 (*P,0.05; **P,0.01; ***P,0.001).

Results

PKC-δ repressed transcription of the hTERT gene in a c-MYC-dependent manner

As shown in Fig. 1A, PKC-δ, but not KN, repressed the activity of the wild type hTERT promoter, while did not repress mutant hTERT promoter with disrupted E-boxes as evidence by luciferase reporter assay (Fig. 1A, phTERT-289EM), showing that it repressed the transcription of the hTERT gene in the c-MYC-dependent manner.

Fig. 1.

PKC-δ represses transcription of the hTERT gene in a c-MYC-dependent manner. The expression plasmid for PKC-δ, dominant-negative PKC-δ (KN), or an empty plasmid (null) was transfected together with the reporter plasmids (A) phTERT-289 or phTERT-289EM, or (B) pc-MYC-DEL1 or pc-MYC-DEL4, into A549 cells. Difference between DEL1 and DEL4 fragments of c-MYC promoter was described elsewhere (8). Luciferase assays were performed using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System. (C) A549 cells transduced with the indicated adenovirus were cultured for 3 days. c-MYC expression was assessed by qRT-PCR and normalized to the corresponding β-actin level. (D) The transcriptional activation ability of c-MYC was evaluated by using GAL4-c-MYC and pFR-Luc as described in Materials and Methods. The transfection and luciferase assays were performed as described above. Data are expressed as means ± SD. **P < 0.01 versus null. N = 3 for all assays.

Next, we evaluated the detailed mechanisms for the c-MYC-dependent transcriptional repression of hTERT by PKC-δ. PKC-δ did not affect the promoter activity of c-MYC as evidence by luciferase reporter assay using c-MYC promoter (Fig. 1B), and transcription of c-MYC gene as revealed by using adenoviral expression system (Fig. 1C). We conducted two different experiments to clarify the role of PKC-δ on the promoter activity and endogenous expression of c-MYC. We also investigated changes in the transcriptional activation ability of c-MYC by using GAL4-c-MYC. The results showed that PKC-δ strongly repressed the transcriptional activation ability of c-MYC, as compared to KN (Fig. 1D). This may be a molecular mechanism for the c-MYC-dependent transcriptional repression of hTERT by PKC-δ.

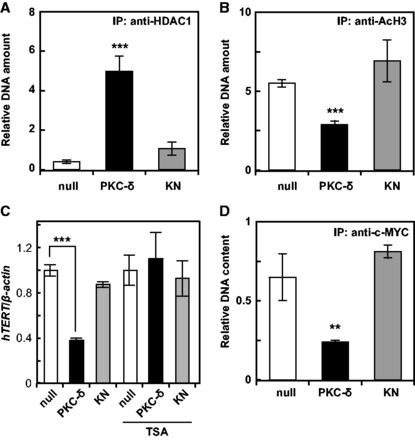

Changes in the quantity of factors binding to the hTERT promoter

Several transcriptional factors including HDAC were reported to be associated with the hTERT promoter (3). The quantity of factors binding to the hTERT promoter was determined by ChIP analysis (12). Firstly, we focused on the histone acetylation status of hTERT promoter. The amount of HDAC1 increased while acetylated histone H3 decreased at the hTERT promoter (Fig. 2A and B). The PKC-δ-induced repression of hTERT transcription was attenuated by trichostatin A treatment (Fig. 2C). Furthermore, we observed a PKC-δ-induced decrease in the amount of c-MYC binding to the hTERT promoter (Fig. 2D). Collectively, these results suggest that PKC-δ removes c-MYC from the hTERT promoter and alternatively recruits HDAC, resulting in deacetylation of histone H3 at the hTERT promoter and the repression of hTERT transcription, one of the models to explain the changes for those factors.

Fig. 2.

Changes in factor binding to the hTERT promoter. The association of HDAC1 (A), acetyl-histone H3 (B), and c-MYC (D) with the hTERT promoter was assessed by the ChIP assay. (C) A549 cells were transfected with the expression plasmid for PKC-δ, KN, or null, and cultured in the presence or absence of 100 nM trichostatin A (TSA). The expression of hTERT was assessed by qRT-PCR. Data are expressed as means ± SD. **P < 0.01 ***P < 0.001 versus null. N = 3 for all assays.

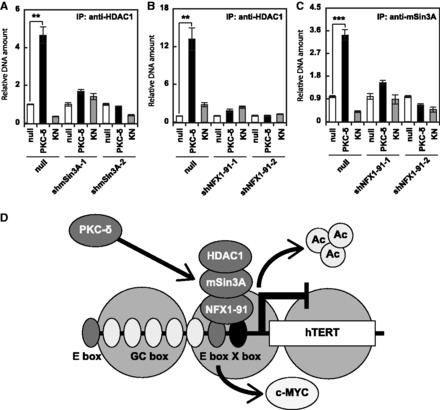

Molecular mechanisms for PKC-δ-induced repression of hTERT transcription

Xu et al. reported that the repression mechanism of hTERT transcription involved the mSin3A/HDAC1/NFX1-91 repressor complex binding to the proximal E-box at the hTERT promoter (11). We assessed the involvement of this repressor complex in the PKC-δ-induced repression of hTERT. The binding of mSin3A and NFX1-91 to the hTERT promoter was increased by PKC-δ (Fig. 3A and B), although the protein expression levels of c-MYC, HDAC1, mSin3A and NFX1-91 remained unchanged (supplementary Fig. S1). This suggested the involvement of the mSin3A/HDAC1/NFX1-91 repressor complex in PKC-δ-induced repression of the hTERT promoter. To clarify this possibility, we established mSin3A-silenced and NFX1-91-silenced A549 cells (Fig. 3C and D, supplementary Fig. S2). PKC-δ-induced repression of hTERT transcription was attenuated in these silenced cells (Fig. 3E–H), indicating that mSin3A and NFX1-91 were involved. The mechanism of this effect appears to be caused by PKC-δ inducing the repressor complex composed of mSin3A, HDAC1 and NFX1-91 to the hTERT promoter and repressing transcription.

Fig. 3.

Molecular mechanisms of PKC-δ-induced repression of hTERT transcription. The association of mSin3A (A) and NFX1-91 (B) with the hTERT promoter was assessed by the ChIP assay. Relative expression of the mSin3A (C) and NFX1-91 (D) genes in mSin3A-silenced (C) and NFX1-91-silenced (D) A549 cells was assessed by qRT-PCR. Relative promoter activity (E) and gene expression (F) of hTERT in mSin3A-silenced A549 cells were assessed by the luciferase assay using phTERTp-289 as described in Materials and Methods and qRT-PCR, respectively. Relative promoter activity (G) and gene expression (H) of hTERT in NFX1-91-silenced A549 cells were assessed by the luciferase assay using phTERTp-289and qRT-PCR, respectively. Data are expressed as means ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 ***P < 0.001 versus null. N = 3 for all assays.

Finally, we analysed the binding mode of the repressor complex. The binding of HDAC1 disappeared in mSin3A-silenced A549 cells (Fig. 4A), and the binding of HDAC1 and mSin3A disappeared in NFX1-91-silenced A549 cells (Fig. 4B and C). These effects also indicated that PKC-δ induces the formation of repressor complex composed of NFX1-91, mSin3A and HDAC1 at the hTERT promoter.

Fig. 4.

PKC-δ induced binding of the NFX1-repressor complex to the hTERT promoter. The association between HDAC1 and the hTERT promoter in mSin3A-silenced (A) and NFX1-91-silenced (B) A549 cells was assessed by the ChIP assay. (C) The association between mSin3A and the hTERT promoter in NFX1-91-silenced A549 cells was assessed by the ChIP assay. Data are expressed as means ± SD. **P < 0.01 ***P < 0.001 versus null. N = 3 for all assays. (D) Schematic representation of PKC-δ-induced repression of hTERT. PKC-δ removes c-MYC, induces deacetylation of histone H3, and recruits the NFX1-repressor complex composed of NFX1-91, mSin3A, and HDAC1 to the hTERT promoter.

Discussion

Several papers have reported critical roles of PKC-δ in cellular senescence (5, 6), showing that it has a role in irreversible growth arrest in senescent cells. We found that senescence-inducing factors including TAK1, PKC-δ and p38 repress transcription of the hTERT gene and induce cellular senescence. Thus, we hypothesized that stringent repression of hTERT was required for the induction of cellular senescence in human cells.

In the present study, to clarify the full spectrum of repression mechanisms of hTERT by senescence-inducing factors, we determined the molecular mechanisms for PKC-δ-induced repression of hTERT. The results showed that PKC-δ repressed hTERT transcription by removing c-MYC and inducing the repressor complex including NFX1-91, mSin3A and HDAC1. The removal of c-MYC would not be necessarily required for the PKC-δ-induced repression of hTERT, because PKC-δ repressed the transcriptional activity ability of c-MYC. NFX1-91 was identified previously as a repressor for the hTERT promoter (12). NFX1-91 binds to an X-box motif located adjacent to the proximal E box of the hTERT promoter, recruiting mSin3A and HDACs, resulting in deacetylation around the hTERT promoter and repression of hTERT transcription (12–14).

Human papillomavirus type-16 E6 induces the expression of hTERT through ubiquitinating and destabilizing NFX1-91 (12, 13, 15). In contrast, we found that PKC-δ induced the repression complex containing NFX1-91, mSin3A and HDAC1, and repressed hTERT transcription. To our knowledge, this is the first study reporting that exogenous signals induce the binding of the NFX1-91 complex to the hTERT promoter, and represses hTERT transcription in cancer cells. These results suggest that targeted recruiting of the NFX1-91 complex to the hTERT promoter is a potential mechanism for repressing hTERT transcription in cancer cells. Furthermore, PKC-δ also repressed the transcriptional activation ability of c-MYC. However, Wang et al. (16) showed that transcriptional activation ability of c-MYC can be inhibited by dominant recruitment of HDAC, thus suggesting that PKC-δ may have global effects on NFX1-91 and HDAC function, which would affect several genes.

There are few reports showing target molecules of PKC-δ in senescent cells. Wheaton and Riabowol (6) have showed that PKC-δ phosphorylates and inactivates SRF, a major transcriptional activator of immediate-early gene promoters in senescent cells. PKC-δ-induced release of SRF from the serum response element would be coordinately regulated with PKC-δ-induced formation of NFX1-91 complex at the hTERT promoter.

Our previous work reported that other senescence-inducing factors, including TAK1 and p38, inhibit transcription of the hTERT gene (3, 4, 14). In particular, we showed that TAK1 repressed the hTERT promoter in an E-box-independent manner through recruiting HDAC to Sp1 at the hTERT promoter. However, in the current study, PKC-δ repressed the hTERT promoter by inducing the binding of NFX1-91 to X-box adjacent to the proximal E-box. Thus, repression of the hTERT promoter by PKC-δ is partially dependent upon E-box (Fig. 1D). Together, these results suggest that cellular senescence-inducing factors repress the hTERT promoter by distinct mechanisms, and that stringent repression of hTERT by such pathways is important for inducing cellular senescence.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. B.V. (Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Chevy Chase, MD, USA) for providing us with the c-MYC reporters (8), and Dr. D.A.G. (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA, USA) for providing us with the anti-NFX1-91 antibody (12).

Funding

This work was supported by the Japanese Society for the Promotion of Science (KAKENHI) grant number 25·4465 to S.Y.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

References

- 1. Daniel M., Peek G.W., Tollefsbol T.O. (2012). Regulation of the human catalytic subunit of telomerase (hTERT). Gene 498, 135–146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kyo S., Takakura M., Fujiwara T., Inoue M. (2008). Understanding and exploiting hTERT promoter regulation for diagnosis and treatment of human cancers. Cancer Sci. 99, 1528–1538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fujiki T., Miura T., Maura M., Shiraishi H., Nishimura S., Imada Y., Uehara N., Tashiro K., Shirahata S., Katakura Y. (2007). TAK1 represses transcription of the human telomerase reverse transcriptase gene. Oncogene 26, 5258–5266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Harada G., Neng Q., Fujiki T., Katakura Y. (2014). Molecular mechanisms for the p38-induced cellular senescence in normal human fibroblast. J. Biochem. 156, 283–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Takahashi A., Ohtani N., Yamakoshi K., Iida S.I., Tahara H., Nakayama K., Nakayama K.I., Ide T., Saya H., Hara E. (2006). Mitogenic signalling and the p16INK4a-Rb pathway cooperate to enforce irreversible cellular senescence. Nat. Cell Biol. 8, 1291–1297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wheaton K., Riabowol K. (2004). Protein kinase C δ blocks immediate-early gene expression in senescent cells by inactivating serum response factor. Mol. Cell Biol. 24, 7298–7311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Katakura Y., Udono M., Katsuki K., Nishide H., Tabira Y., Ikei T., Yamashita M., Fujiki T., Shirahata S. (2009). Protein kinase C δ plays a key role in cellular senescence programs of human normal diploid cells. J. Biochem. 146, 87–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. He T.C., Sparks A.B., Rago C., Hermeking H., Zawel L., da Costa L.T., Morin P.J., Vogelstein B., Kinzler K.W. (1998). Identification of c-MYC as a Target of the APC Pathway. Science 281, 1509–1512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hirai S., Izumi Y., Higa K., Kaibuchi K., Mizuno K., Osada S., Suzuki K., Ohno S. (1994). Ras-dependent signal transduction is indispensable but not sufficient for the activation of AP1/Jun by PKC delta. EMBO J. 13, 2331–2340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yamashita S., Ogawa K., Ikei T., Udono M., Fujiki T., Katakura Y. (2012). SIRT1 prevents replicative senescence of normal human umbilical cord fibroblast through potentiating the transcription of human telomerase reverse transcriptase gene. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 417, 630–634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yamashita S., Ogawa K., Ikei T., Fujiki T., Katakura Y. (2014). FOXO3a potentiates hTERT gene expression by activating c-MYC and extends the replicative life-span of human fibroblast. PLoS One 9, e101864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Xu M., Luo W., Elzi D.J., Grandori C., Galloway D.A. (2008). NFX1 interacts with mSin3A/histone deacetylase to repress hTERT transcription in keratinocytes. Mol. Cell Biol. 28, 4819–4828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Galloway D.A., Gewin L.C., Myers H., Luo W., Grandori C., Katzenellenbogen R.A., McDougall J.K. (2005). Regulation of telomerase by human papillomaviruses. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 70, 209–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Katakura Y. (2006). Molecular basis for the cellular senescence program and its application to anticancer therapy. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 70, 1076–1081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gewin L., Myers H., Kiyono T., Galloway D.A. (2004). Identification of a novel telomerase repressor that interacts with the human papillomavirus type-16 E6/E6-AP complex. Genes Dev. 18, 2269–2282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wang J., Elahi A., Ajidahun A., Clark W., Hernandez J., Achille A., Hao J.H., Seto E., Shibata D. (2014). The interplay between histone deacetylases and c-Myc in the transcriptional suppression of HPP1 in colon cancer. Cancer Biol. Ther. 15, 1198–1207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.