Abstract

Objective

To develop a tool for independent observational assessment of cancer multidisciplinary team meetings (MDMs), and test criterion validity, inter-rater reliability/agreement and describe performance.

Design

Clinicians and experts in teamwork used a mixed-methods approach to develop and refine the tool. Study 1 observers rated pre-determined optimal/sub-optimal MDM film excerpts and Study 2 observers independently rated video-recordings of 10 MDMs.

Setting

Study 2 included 10 cancer MDMs in England.

Participants

Testing was undertaken by 13 health service staff and a clinical and non-clinical observer.

Intervention

None.

Main Outcome Measures

Tool development, validity, reliability/agreement and variability in MDT performance.

Results

Study 1: Observers were able to discriminate between optimal and sub-optimal MDM performance (P ≤ 0.05). Study 2: Inter-rater reliability was good for 3/10 domains. Percentage of absolute agreement was high (≥80%) for 4/10 domains and percentage agreement within 1 point was high for 9/10 domains. Four MDTs performed well (scored 3+ in at least 8/10 domains), 5 MDTs performed well in 6–7 domains and 1 MDT performed well in only 4 domains. Leadership and chairing of the meeting, the organization and administration of the meeting, and clinical decision-making processes all varied significantly between MDMs (P ≤ 0.01).

Conclusions

MDT-MOT demonstrated good criterion validity. Agreement between clinical and non-clinical observers (within one point on the scale) was high but this was inconsistent with reliability coefficients and warrants further investigation. If further validated MDT-MOT might provide a useful mechanism for the routine assessment of MDMs by the local workforce to drive improvements in MDT performance.

Keywords: cancer, quality assessment, observation, multidisciplinary team, patient care team, teamwork

Introduction

Tumour specific multidisciplinary teams (MDTs, sometimes called multidisciplinary tumour boards) are now firmly established as fundamental to the organization of cancer services in the UK and other countries [1–3]. A central component of the MDT model of care is the regular MDM, bringing together a range of health professionals to agree recommendations about the management of patients. With accumulating evidence of the benefits that cancer MDTs confer [3], including reduced variation in survival [4–6], there has been increasing emphasis on ensuring that MDTs perform both effectively and efficiently in order to deliver optimal patient care [7, 8].

In England some aspects of MDT working, such as MDT membership and whether protocols for referral and treatment are in place, are assessed through the national cancer peer review programme. [9] Adherence to these standards, within and between tumour types, is variable [10] and many other aspects of teamworking are not easily translated to measurable national standards, but may equally impact on the quality of care. This includes the quality of leadership of the MDT, the patient-centredness of the decision-making process and the inclusiveness and quality of communication between MDT members [11–13]. Poor quality discussions in MDMs, particularly the failure to consider all relevent information, may result in recommendations that are not implemented in practice [14–16] and/or cause delays in patient treatment [17, 18].

Structured observational assessment and feedback has proved a useful technique to help drive improvements in the way health teams work together, for example during surgical procedures [19]; and in anaesthesia [20]. Independent observers can potentially help MDT members to recognize areas where performance could be improved that they may not have been aware of themselves including what they are doing as well as what could be improved [21]. Structured observational assessment tools for assessing MDT performance within cancer MDMs have been developed [22, 23] but cannot be easily used without some training and supervision. Furthermore, although the assessment of teamwork in routine practice may be beneficial and cost-effective for encouraging health professional development [24], formalized mechanisms to facilitate this are lacking (e.g. using standardized processes, assessing measurable quality standards) [7]. For the routine observational assessment of cancer MDMs to be sustainable and encourage organizational learning, it would need to be feasible for assessments to be undertaken by locally based health services staff, rather than costly external teamwork experts or specialist researchers [25]. We have previously established proof of concept that it is feasible for health service clinicians and managers with no formal training in observational techniques to undertake structured observational assessment and that MDT members find such feedback useful [26].

The Characteristics of an Effective MDT [7], produced by England's National Cancer Action Team (NCAT), outlines the optimal components of MDT performance based on clinical consensus from a survey completed by over 2,000 cancer MDT members. It contains nearly 100 recommendations for effective cancer teamworking organized under 17 ‘domains’, many of which are potentially observable in MDMs. We have previously used this as a framework to underpin the development of a questionnaire, the Team Evaluation and Assessment Measure [27], to enable MDT members to self-assess their performance. In this study, we aimed to develop an observational assessment tool, underpinned by the Characteristics of an Effective MDT, suitable for routine use in cancer MDMs by clinical and non-clinical professionals (including health service staff with no previous experience of conducting such assessments). The objectives were:

To test criterion validity, the extent to which it can discriminate between different levels of performance, when used by health service staff without prior training (Study 1)

To test reliability and agreement when used by different observers, including clinical and non-clinical assessors (Study 2)

To describe team performance in cancer MDMs (including variation within and between MDTs, as well as describing the aspects of teamwork performed most and least well) (Study 2).

Methods

Tool development

Preliminary work was undertaken with 20 MDTs and has been described in detail elsewhere [26]. The content was calibrated against the Characteristics of an Effective MDT [7]. Of the 17 domains of teamwork within this document, the tool includes 10 that are observable in MDMs. Domains include: attendance at MDT meetings, leadership and chairing in MDT meetings, teamworking and culture, personal development and training, physical environment of the meeting venue, technology and equipment available for use in MDT meetings, organization and administration during meetings, patient-centred care, clinical decision-making processes and post-meeting co-ordination of service (e.g. the clarity of ‘next steps’ in the meeting discussion). A prototype version was tested for proof of concept with 20 MDTs [26]. Key findings were that the tool was acceptable and useful but usability could be improved by incorporating descriptive textual ‘anchors’ for extreme and mid-points on the scale.

The tool was modified to improve format and usability. This included developing descriptive anchors for scores at the lower, mid and upper end of the rating scale. The revised tool was subsequently piloted by: (i) a senior cancer nurse and a surgeon (R.J.) who observed video-recordings of five MDMs; (ii) six NHS Trust-based peer observers (senior clinicians and managers) observing MDTs within their Trust in vivo; and (iii) an independent multidisciplinary panel of cancer service researchers. All users provided feedback on face and content validity, acceptability and ease of use and further changes were made including refinements to the descriptive anchors and format/layout of the tool.

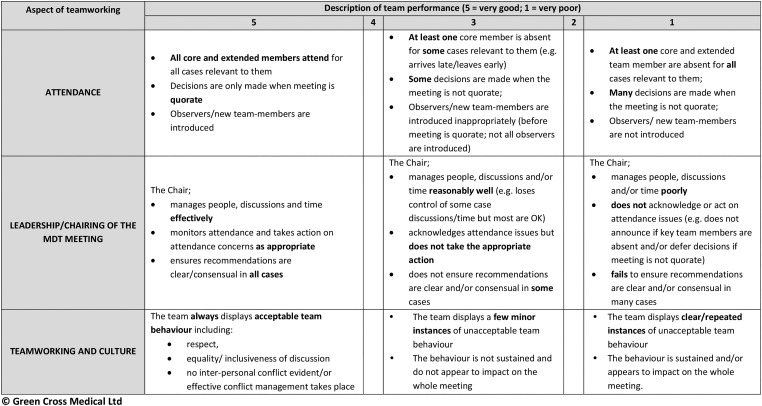

In the resulting MDT-Meeting Observational Tool (hereafter referred at as MDT-MOT) all 10 observable teamwork domains are rated on a 5-point rating scale, using descriptive anchors for the extremes and midpoint of the scale [28]. A score of ‘5’ represents optimal effectiveness, calibrated against recommendations within ‘The Characteristics of an Effective MDT’ [7]. A score of ‘3’ represents effectiveness that exhibits some degree of agreement with the optimum, but not consistently, and a score of ‘1’ represents no or little agreement with the defined optimum. Scores of ‘2’ and ‘4’ were included but not defined to allow observers the freedom to gradate their assessment. This approach to observational scoring (high, medium and low anchors, plus intermediate scores that allow gradation) is particularly useful for assessing workplace performance [28] and has used been extensively in relation to assessing team performance [19, 22, 23] (See Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

MDT-MOT© rating scale for three domains of teamworking (for illustration).

Study 1: assessing criterion validity when used by health service staff without prior training

Participants

Observers were 13 participants at a workshop (facilitated by C.T. and J.H.) about MDT working within a national cancer conference in England. Participants included 1 clinician and 12 non-clinicians (e.g. cancer service managers). None had undertaken structured observational assessment previously.

Procedure

Participants were given a brief introduction to the purpose and use of MDT-MOT and were then asked to use MDT-MOT to independently rate the performance of MDTs they viewed on two brief films. The films consisted of re-enacted MDM excerpts (real meetings were filmed and re-produced faithfully by actors). The films were developed by the National Cancer Action Team (NCAT, responsible for supporting implementation of cancer policy in England at the time) overseen by a panel of cancer experts to illustrate the characteristics of an effective MDT. The excerpts included MDT discussions where optimal and sub-optimal behaviour are shown (Film 2 and 1, respectively) lasting approximately 12 min in total. Participants were asked to act as the independent observer for the MDT and to use MDT-MOT to rate each MDT film individually.

Study 2: assessing MDT performance, inter-rater reliability and agreement using clinical and non-clinical observers

MDT meetings

Ten cancer MDMs were video-recorded; this included two colorectal, two upper GI, two head and neck, two skin, one teenage and young adult, and one urology MDT.

Procedure

MDMs were video-recorded using a digital camcorder with a wide angled lens and external microphone, set on a tripod (facing the attendees). MDT members were asked to maintain patient anonymity in discussions by referring to patients using ID numbers instead of their names. Subsequently, a surgeon registrar (R.J.) and research psychologist (J.H.) independently viewed the films and assessed each MDM using the MDT-MOT. Both were experienced at assessing MDT performance and using observational tools, one was experienced at using the MDT-MOT (J.H.).

Data analyses

In Study 1 criterion validity was established if observers' were able to discriminate between optimal (film 2) and sub-optimal performance (film 1), assessed using Mann–Whitney U tests. In Study 2 descriptive statistics (mean, SD, median, range) for the performance scores per domain are presented. Inter-rater reliability, the extent to which the observers were able to differentiate between MDT performance in each domain of teamworking, was assessed statistically using weighted Kappa [29]. Inter-rater agreement, the extent to which the ratings were identical, was assessed by presenting percentage agreement (both absolute agreement, and within 1-point on the scale) [30]. Variation in performance between MDTs was assessed statistically using Kruskal Wallis. To enable visual comparison of variation between and within MDTs, the summed overall score out of 50 was calculated and ratings for each domain were dichotomized with scores above 3 indicating ‘best performance’ vs. scores of 3 or less. All statistical tests were performed using SPSS version 20.0. Significance was taken at the 0.05 level. The methods presented here align closely with those described in published reporting guidelines for reliability and agreement [30].

Ethics

The protocol for the project was reviewed by the UK National Research Ethics Service (NRES) and was classified and approved as service development.

Results

Study 1: criterion validity of MDT-MOT

Median and mean observer ratings for film 1 (worse teamworking) were 2.5 or less, for 9 out of 10 domains, indicating agreement from the raters that the team exhibited sub-optimal performance. The exception was the physical environment of the meeting venue, with a median rating of 3. In comparison, median and mean observer ratings for film 2 (better teamworking) were all greater than 3, indicating agreement between raters that the team exhibited better performance than film 1 (Table 1). Within-observer comparison of ratings for the two films revealed significant differences for all domains of MDM performance (all P ≤ 0.05; data not shown, available on request), suggesting that MDT-MOT could reliably discriminate between better and worse MDT performance.

Table 1.

Study 1: ratings for domains of MDT meeting performance in each film

| Sub1-domains of MDT meeting performance assessed | Film 1 (worse teamwork) |

Film 2 (better teamwork) |

Statistical significance* | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | Min–Max | Mean | SD | Median | Min–Max | Mean | SD | ||

| Attendance at MDT meetings | 1.0 | 1–3 | 1.73 | 0.91 | 4.0 | 3–5 | 3.91 | 0.83 | U (20) = 6.0, Z = −3.70, P < 0.001 |

| Leadership and chairing | 1.0 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 5.0 | 4–5 | 4.69 | 0.48 | U (24) = 0.0, Z = −4.75, P < 0.001 |

| Teamwork and culture | 1.0 | 1–2 | 1.15 | 0.38 | 5.0 | 4–5 | 4.75 | 0.45 | U (23) = 0.0, Z = −4.56, P < 0.001 |

| Personal development and training | 1.0 | 1–2 | 1.25 | 0.46 | 3.0 | 1–5 | 3.14 | 1.68 | U (13) = 10.0, Z = −2.27, P = 0.023 |

| Physical environment of the meeting venue | 3.0 | 1–4 | 2.46 | 1.05 | 3.5 | 2–5 | 3.67 | 0.99 | U (23) = 34.0, Z = −2.50, P = 0.013 |

| Technology and equipment available for use in MDT meetings | 2.5 | 1–5 | 2.42 | 1.31 | 5.0 | 2–5 | 4.54 | 0.97 | U (23) = 17.5, Z = −3.47, P = 0.001 |

| Organization and administration during MDT meetings | 1.0 | 1–2 | 1.23 | 0.44 | 4.0 | 3–5 | 4.38 | 0.65 | U (24) = 0.0, Z = −4.52, P = 0.001 |

| Patient-centred care | 1.0 | 1–2 | 1.33 | 0.49 | 5.0 | 4–5 | 4.85 | 0.38 | U (23) = 13.0, Z = −0.3.75, P < 0.001 |

| Clinical decision-making | 1.0 | 1–3 | 1.38 | 0.65 | 5.0 | 3–5 | 4.69 | 0.63 | U (24) = 0.5, Z = −4.54, P < 0.001 |

| Post- meeting coordination of services | 1.0 | 1–3 | 1.44 | 0.73 | 4.0 | 2–5 | 3.86 | 1.22 | U (14) = 3.0, Z = −3.13, P = 0.002 |

*Significance of difference between ratings for Films 1 and 2, Mann–Whitney U test.

Study 2: characteristics of cancer MDT meetings

Between 4 and 33 cases were discussed at each meeting (median = 14 cases, mean = 38.6 cases, SD = 1.4) with an average of 10 MDT-members in attendance (range 8–12) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Study 2: characteristics of the observed MDT meetings

| MDT meeting observed | Number of patient cases discussed in meeting | Meeting duration (min) | Number of MDT members in attendance at the meeting |

|---|---|---|---|

| Colorectal | 21 | 99 | 11 |

| Colorectal | 13 | 64 | 9 |

| Colorectal | 16 | 97 | 11 |

| Head and neck | 9 | 43 | 11 |

| Head and neck | 17 | 78 | 10 |

| Skin | 14 | 54 | 9 |

| Teenage and young adult | 10 | 32 | 8 |

| Upper GI | 14 | 80 | 9 |

| Upper GI | 4 | 30 | 12 |

| Urology | 33 | 118 | 8 |

| Total | 151 | 695 | 98 |

| Mean | 15 | 126 | 10 |

| Median | 14 | 71 | 10 |

Inter-rater reliability and agreement using MDT-MOT

Weighted Kappa (K) statistics indicated good reliability for three domains of teamworking: clinical decision-making, organization and administration during MDT meetings, and leadership of the team and chairing of the MDT meeting (K ≥ 0.60) [29, 31]. Percentage agreement showed that in these three domains, plus one further (patient-centred care) at least 80% of observers' ratings were in absolute agreement; and in all but one domain (attendance at MDMs) at least 80% of the ratings agreed at least within 1-point on the scale (Table 3).

Table 3.

Study 2: observers' ratings for domains of MDT meeting performance: reliability and agreement

| Domain of MDT meeting | Observer 1 (surgeon) |

Observer 2 (psychologist) |

Reliabilitya |

Percentage agreement | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | Min–Max | Mean | SD | Median | Min–Max | Mean | SD | Weighted Kappa | Absolute agreement | Agreement ±1 point | |

| Attendance at MDT meetings | 3.5 | 2–5 | 3.8 | 1.14 | 4 | 3–5 | 4.1 | 0.88 | 0.17 | 40 | 70 |

| Leadership and chairing | 4.0 | 1–5 | 3.6 | 1.17 | 4 | 2–4 | 3.4 | 0.84 | 0.62 | 90 | 100 |

| Teamwork and culture | 4.0 | 3–4 | 3.9 | 0.32 | 4 | 3–5 | 3.8 | 0.63 | 0.32 | 70 | 100 |

| Personal development and training | 2.0 | 2–3 | 2.4 | 0.52 | 3 | 2–4 | 2.8 | 0.63 | 0.06 | 50 | 100 |

| Physical environment of the meeting venue | 4.0 | 3–5 | 4.2 | 0.63 | 4 | 4–5 | 4.1 | 0.63 | 0.32 | 70 | 100 |

| Technology and equipment available for use in MDT meetings | 4.0 | 3–4 | 3.8 | 0.50 | 4 | 3–5 | 3.7 | 0.68 | 0.45 | 50 | 80 |

| Organization and administration during MDT meetings | 4.0 | 3–5 | 3.7 | 0.68 | 4 | 3–4 | 3.6 | 0.52 | 0.83 | 90 | 100 |

| Patient-centred care | 4.5 | 3–5 | 3.9 | 0.74 | 4 | 3–5 | 3.7 | 0.68 | 0.24 | 80 | 100 |

| Clinical decision-making | 4.0 | 3–5 | 3.7 | 0.68 | 4 | 3–4 | 3.6 | 0.52 | 0.83 | 90 | 100 |

| Post- meeting coordination of services | 4.5 | 3–5 | 4.4 | 0.70 | 4 | 3–5 | 4.1 | 0.88 | −0.07 | 20 | 90 |

aWeighted Kappa interpretation: ≤0 poor, 0.01–0.20 = slight, 0.21–0.40 = fair, 0.41–0.60 = moderate, 0.61–0.80 = substantial and 0.81–1 = almost perfect [31].

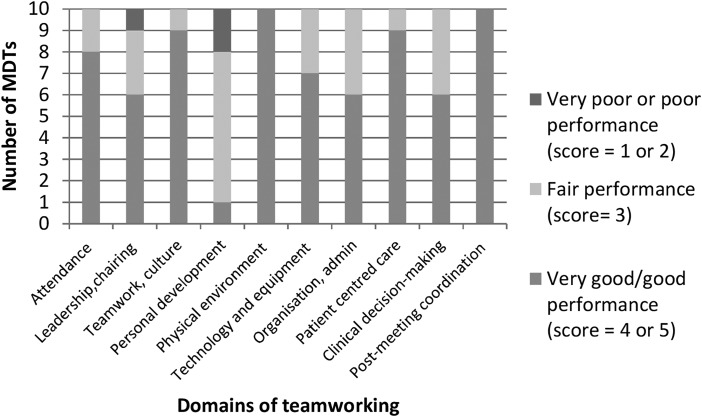

Variation in performance within and between MDTs

There was evidence of consistency in performance across domains within teams, with four MDTs performing well (‘good’ or ‘very good’, i.e. score greater than 3) in eight or nine domains, five MDTs performing well in six or seven domains, and one MDT performing well in only four domains (Table 4, Fig. 2).

Table 4.

Study 2: variation in performance across the ten observable domains of teamworking within and between teams

| Domain of MDT meeting performance | MDT |

Number of MDTs scoring >3 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean score (1–5)a |

|||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | ||

| Attendance at MDT meetings | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 8 |

| Leadership and chairing | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 6 |

| Teamwork and culture | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 9 |

| Personal development and training | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 1 |

| Physical environment of the meeting venue | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 10 |

| Technology and equipment available for use in MDT meetings | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 7 |

| Organization and administration during MDT meetings | 3 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 6 |

| Patient-centred care | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 9 |

| Clinical decision-making | 3 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 6 |

| Post-meeting coordination of services | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 10 |

| Total score (potential range 10–50) | 37 | 39 | 38 | 40 | 39 | 36 | 36 | 39 | 32 | 38 | |

| Number of domains >3 | 6 | 9 | 8 | 9 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 9 | 4 | 7 | |

aBased on the two observers' combined ratings.

Figure 2.

Variation in MDT performance by domain of teamworking.

There was diversity in performance between MDTs. Total scores (out of 50) ranged from 32 to 40 (Table 4). Ratings of performance in relation to leadership and chairing of the meeting, organization and administration during meetings and clinical decision-making processes all varied significantly between MDTs (Kruskal–Wallis test, ≤0.05; data not shown, available on request). No other significant variations in domains between MDTs were found. All MDTs were evaluated well for the physical environment of the meeting venue, but only one MDT performed well in demonstrating evidence of personal development and training within their MDM.

Discussion

This study offers preliminary evidence that the MDT-MOT has good criterion validity. However, the results for reliability and agreement were inconclusive. The findings suggest that, when used by a clinical and non-clinical assessor, MDT-MOT could reliably differentiate performance for 3 of the 10 domains of cancer teamworking, but ratings given for 9 out of the 10 domains of teamworking by the two raters were at least within 1 point of each other 80% of the time, showing high agreement. This is important because it suggests there was some consistency between observers' ratings. The discrepancy between the reliability and agreement coefficients is an acknowledged statistical paradox and is challenging to interpret, particularly because Kappa coefficients are influenced by the prevalence of the phenomenon being measured and sample size [29, 32, 33]. In this study MDTs tended to perform well, with a high prevalence of positive ratings; in such instances chance agreement would be high and Kappa is reduced accordingly. Furthermore, the sample size of 10 MDTs, although comparing favourably to samples in the development of similar tools [22, 23], may not be sufficient to detect a statistically significant coefficient [33]. This is because the MDT-MOT assesses overall meeting performance rather than performance on a patient-by-patient basis (e.g. MDT-Metric for the Observation of Decision-making (MODe)) [22]. Therefore, we suggest that the percentage agreement provides a more useful indicator of reliability in this instance.

As this is the first evaluation of MDT-MOT is unclear to what extent any discrepancies between observers are an artefact of the tool, or may reflect the clinical/non-clinical backgrounds of the observers, and/or their professional biases or experiences as a surgeon and psychologist. The differences may alternatively be accounted for by having varied observer learning curves for using the tool, as one observer was more experienced at using MDT-MOT, as found with other measures [22, 34]. Furthermore, it is likely that some training or at least preparation (e.g. practice using the tool) would optimize the reliability of assessments [25]. Future research should test the reliability of MDT-MOT in the hands of clinical and non-clinical ‘peer’ observers attending meetings in person, an approach that has been used in the development of other tools [22]. In addition, it would be valuable to evaluate the utility and validity of MDT-MOT in relation to existing team member self-assessment tools [27] and other MDT observational measures [22, 23], and to obtain MDT members' views of its utility for MDT development. Furthermore, it would be useful to examine the tools' performance when used with MDTs that may operate differently (e.g. ‘speciality’ MDTs such a paediatric and rarer tumours), and in contexts outside the UK.

MDT-MOT is intended to support team development. Our findings are unlikely to impact on the overall utility of the scale when used in routine practice for this purpose, as it is intended to be used as part of a toolkit to enable MDT members to assess and receive feedback on their MDT performance (e.g. to be used alongside MDT member self-assessment and review of practice, audit of clinical practice, and patient experience survey data), all of which may capture different aspects of performance [21]. Indeed previous research has shown that not only do cancer MDT members assess their MDTs performance differently to external observers particularly in relation to the degree of patient-centredness demonstrated in meetings [21], but there may also be considerable variability in how members of the same MDT view the purpose of the MDT in relation to this domain [35].

Although most MDTs performed well, performance did vary between MDTs. In contrast to findings in a previous study within one tumour type (colorectal) [23] the MDTs in this study typically performed well in relation to having patient-centred discussions, documenting post-meeting actions and having suitable meeting venues. MDTs appeared not to prioritize integration of explicit training into MDMs. This putative benefit of MDMs is cited by MDT members' themselves [7]; however, it may be that in time-pressured meetings it is neglected.

The quality of leadership including chairing of the MDMs also varied considerably. Within the UK context, clinicians typically hold leadership roles due to their clinical expertise, but little opportunity or support is provided for leadership development [36, 37]. Incorporating the assessment of MDMs into routine practice could have benefits for individuals, teams and the wider organization by sharing best practice and highlighting areas for improvement that could be prioritized for investment/training.

Some limitations should be noted. In order to assess criterion validity when used by non-experts without prior training, Study 1 utilized films of re-enacted meetings that had been intentionally produced to represent optimal and sub-optimal team performance as has been used in the development of other tools [38]. However, as these were excerpts they were much shorter than a usual MDM: whole MDMs are likely to contain greater gradations with regards to performance. Study 1 participants were a convenience sample and only included one clinician; future research would benefit from testing with a wider variety of clinical and non-clinical staff, and across a range of MDM settings. The MDTs in Study 2 were also a small convenience sample and thereby caution must be exercised when generalizing beyond these teams, for instance perhaps MDTs that performed better were more likely to consent to being observed. However, the sample did include a range of tumour specialties from six NHS Trusts, and the overall number of cases discussed is comparable to those reported in the development of other observational tools [22, 23]. The MDMs we recorded were stated to be ‘typical’ of the weekly MDM by the team members, though it is recognized that in the busy environment of a case discussion meeting it may be difficult to assess all aspects of the discussion [22, 39]. However, MDT-MOT was designed for the routine assessment of usual busy cancer MDMs by local health services staff with minimum training, and it is reassuring that in this context we have been able to demonstrate criterion validity and good agreement between raters, although the reliability statistics present a weaker agreement and warrant further investigation.

Conclusions

If further validated, MDT-MOT may provide a useful mechanism for the routine assessment of MDM effectiveness. This could not only assist individual MDTs in recognizing where they perform well and those areas to prioritize for development and improvement, but also benefit the wider healthcare organization. Sharing best practice may help organizations to identify where they could support their MDTs further to promote the delivery of effective MDMs and patient care.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the National Cancer Action Team (NCAT). N.S. research was supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care South London at King's College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust. N.S. is a member of King's Improvement Science, which is part of the NIHR CLAHRC South London and comprises a specialist team of improvement scientists and senior researchers based at King's College London. Its work is funded by King's Health Partners (Guy's and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, King's College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, King's College London and South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust), Guy's and St Thomas’ Charity, the Maudsley Charity and the Health Foundation. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health. J.S.A.G. has received funding from the NCAT for the development of a team training/feedback system for cancer MDTs through Green Cross Medical Ltd. N.S. has been a paid advisor to Green Cross Medical Ltd. C.T. and J.H. were funded for this work through a subcontract between King's College London and Green Cross Medical Ltd. N.S. is the Director of the London Safety and Training Solutions Ltd, which undertakes team, safety and human factors training and advisory work on a consultancy basis with hospitals internationally. R.J. reports no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the MDT members and health service staff who participated, and the Trust personnel who facilitated their involvement; other affiliate members of Green Cross Medical Ltd who have supported this work; and the UK's National Cancer Action Team (NCAT) MDT Development steering group and sub-committee members for their input and comments. We would also like to thank Poonam Gohill for research assistance; and Lallita Carballo for her expert feedback during the development of the tool.

References

- 1. Chan WF, Cheung PS, Epstein RJ et al. . Multidisciplinary approach to the management of breast cancer in Hong Kong. World J Surg 2006;30:20–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wright FC, Lookhong N, Urbach D. Multidisciplinary cancer conferences: identifying opportunities to promote implementation. Ann Surg Oncol 2009;16:2731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Taylor C, Munro AJ, Glynne-Jones R et al. . Multidisciplinary team working in cancer: what is the evidence. BMJ 2010;340:c951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kersten C, Cvancarova M, Mjaland S. Does in house availability of multidisciplinary teams increase survival in upper gastrointestinal cancer. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2013;5:60–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kesson EM, Allardice GM, George WD et al. . Effects of multidisciplinary team working on breast cancer survival: retrospective, comparative, interventional cohort study of 13 722 women .Br Med J 2012;344:e2718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Eaker S, Dickam P, Hellstrom V et al. . Regional differences in breast cancer survival despite common guidelines. Cancer Epideimol Biomarkers Prev 2005;14:2914–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. National Cancer Action Team. Characteristics of an Effective MDT. London: National Cancer Action Team, 2010. http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20130513211237/http:/www.ncat.nhs.uk/ (28 July 2015, data last accessed). [Google Scholar]

- 8. De Ieso PB, Coward JI, Letsa I et al. . A study of the decision outcomes and financial costs of multidisciplinary team meetings (MDMs) in oncology. B J Cancer 2013;109:2295–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Department of Health. Manual for Cancer Services. London: Department of Health, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 10. National Cancer Action Team. National Peer Review Programme. Report 2011/2012: An overview of the findings from the 2011/2012 National Cancer Peer Review of cancer service in England. London: National Cancer Action Team, 2012. http://www.cquins.nhs.uk/?menu=info (28 July 2015, date last accessed). [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lanceley A, Savage J, Menon U et al. . Influences on multidisciplinary team decision-making. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2008;18:215–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lamb BW, Sevdalis N, Arora S et al. . Teamwork and team decision-making at multi-disciplinary cancer conferences: barriers, facilitators, and opportunities for improvement. World J. Surg. 2011;35:1970–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rowland S, Callen J. A qualitative analysis of communication between members of a hospital-based multidisciplinary lung cancer team. Euro J Cancer Care 2013;22:22–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Blazeby JM, Wilson L, Metcalfe C et al. . Analysis of clinical decision-making in multi-disciplinary cancer teams. Ann Oncol 2006;17:457–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lamb B, Brown KF, Nagpal K et al. . Quality of care management decisions by multidisciplinary cancer teams: a systematic review. Ann Surg Oncol 2011;18:2116–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. English R, Metcalfe C, Day J et al. . A prospective analysis of implementation of multi-disciplinary team decisions in breast cancer. Breast J 2012;18:456–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Leo F, Venissa NAP, Poudenx M et al. . Multidisciplinary management of lung cancer: how to test its efficacy. J Thorac Oncol 2007;2:69–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Goolam-Hoosen T, Metcalfe C, Cameron A et al. . Waiting times for cancer treatment: the impact of multidisciplinary team meetings. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2004;30:467–71. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hull L, Arora S, Kassab E et al. . Observational Teamwork Assessment for Surgery (OTAS): content validation and tool refinement. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2011;212:234–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fletcher G, Flin R, McGeorge P. Anaesthetists non-technical skills (ANTS): evaluation of a behavioural marker system. Br J Anaesth 2003;90:580–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lamb B, Sevdalis N, Mostafid H et al. . Quality improvement in Multidisciplinary Cancer Teams: An investigation of teamwork and clinical decision-making and cross-validation of assessments. Ann Surg Oncol 2011;18:3535–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lamb B, Wong HW, Vincent C et al. . Teamwork and team performance in multidisciplinary cancer teams: development and evaluation of an observational tool. BMJ Qual Saf 2011;10:849–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Taylor C, Atkins L, Richardson M et al. . Measuring the quality of MDT working: an observational approach. BMC Cancer 2012;12:202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hogston R. Evaluating the quality of nursing care through peer review and reflection; the findings of a qualitative study. Int J Nurs Stud 1995;32:162–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hull LE, Arora S, Symons NR et al. . Training faculty in non-technical skills assessment: national guidelines on program requirements. Ann Surg 2013;258:370–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Harris J, Green JSA, Sevdalis N et al. . Using peer observers to assess the quality of cancer multidisciplinary team meetings: a qualitative proof of concept study. J. Multidiscip. Healthcare 2014;7:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Taylor C, Brown K, Lamb B et al. . Developing and Testing TEAM (Team Evaluation and Assessment Measure), a self-assessment Tool to Improve Cancer Multidisciplinary Teamwork. Ann Surg Oncol 2012;19:4019–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bradburn NM, Sudman S, Wansink B. Asking Questions. The Definitive Guide to Questionnaire Design- for Market Research, Political Polls and Social and Health Questionnaires. San Franciso: Josey-Bass, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Viera AJ, Garret JM. Understanding inter observer agreement: the kappa statistic. Fam Med 2005;37:360–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kottner J, Audigé L, Brorson S et al. . Guidelines for reporting reliability and agreement studies (GRRAS) were proposed. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2011;48:661–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977;159–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. McHugh ML. Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochem. Med. 2012;22:276–82. http://dx.doi.org/10.11613/BM.2012.031 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sim J, Wright CC. The kappa statistic in reliability studies: use, interpretation, and sample size requirements. Phys. Ther. 2005;85:257–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jalil R, Akhter W, Lamb BW et al. . Validation of team performance assessment for multidisciplinary tumor boards. J Urol 2014;192:891–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Taylor C, Finnegan-John J, Green JSA. ‘No decision about me without me’ in the context of cancer multidisciplinary team meetings: a qualitative interview study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014;14:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ham C, Clark J, Spurgeon P et al. . Doctors who become chief executives in the NHS: from keen amateurs to skilled professionals. J. R. Soc. Med. 2011;104:113–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. British Medical Association. Doctors Perspective on Clinical Leadership. London: BMA, 2012. http://bma.org.uk/news-views-analysis/news/2012/june/survey-reveals-doctors-views-of-clinical-leadership (16 March 2016, date last accessed). [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pezzolesi C, Manser T, Schifano F et al. . Human factors in clinical handover: development and testing of a ‘handover performance tool for doctors shift handovers. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2013;25:58–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Healey AN, Undre S, Vincent CA. Developing observational measures of performance in surgical teams. Qual Saf Health Care 2004;13:i33–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]