Abstract

Background

Although attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a common condition for which pharmacotherapy is considered an effective treatment, guidelines on the treatment of ADHD have been challenging to implement. Considering the views of patients and caregivers involved in medication-taking could help shed light on these challenges.

Objective

This review combines the findings of individual studies of medication-taking experiences in ADHD in order to guide clinicians to effectively share decisions about treatment.

Methods

Five databases (MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO, SCOPUS and CINAHL) were systematically searched for relevant published research articles. Articles were assessed for quality using a Critical Appraisal Skills Programme checklist, and synthesis was performed using meta-ethnography.

Results

Thirty-one articles were included in the final synthesis, comprising studies of caregivers, paediatric patients and adult patients across seven countries. Findings were categorized into five different constructs, including coming to terms with ADHD, anticipated concerns about medication, experiences of the effects of medication, external influences and the development of self-management. The synthesis demonstrates that decisions surrounding medication-taking for ADHD evolve as the child patient enters adulthood and moves towards autonomy and self-management. In all parts of this journey, decisions are shaped by a series of ‘trade-offs’, where potential benefits and harms of medication are weighed up.

Conclusions

This review offers a comprehensive insight into medication-taking experiences in ADHD. By considering the shifting locus of decision-making over time and the need for individuals and families to reconcile a variety of external influences, primary care and mental health clinicians can engage in holistic conversations with their patients to share decisions effectively.

Keywords: ADHD, medications, drugs, adherence

Introduction

Attention Deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is characterized by the inability to sustain attention, modulate activity level and moderate impulsive actions (1). Although the resulting maladaptive behaviours are typically first recognized during childhood, symptoms often continue into adulthood (2). Untreated ADHD has been associated with significant social and psychological sequelae (3). Although pharmacotherapy is considered to be an effective treatment for ADHD (4), recommendations vary with regard to the use of medications as a first-line treatment (5,6).

Despite the apparent efficacy of medications and negative consequences of untreated ADHD, rates of adherence to medication regimes are low, with an estimated 50% of patients choosing to discontinue pharmacotherapy (7). ADHD is diagnosed based on clinical symptoms with a lack of objective physical examination or laboratory investigation findings, and moreover, ADHD behaviours can overlap and coexist with other mental health conditions (1). It has also received widespread and often contradictory media coverage in recent years (8). As such, there are likely to be a complex array of factors that contribute to treatment decisions.

Medication adherence is a multidimensional phenomenon that is shaped by factors relating to the patient, type of treatment, condition, healthcare system and individual social circumstances (9). Non-adherence is described as unintentional when the patient wants to adhere but is unable to due to lack of resources or capacity. Intentional adherence, meanwhile, occurs when individuals make an active choice not to comply with treatment recommendations (10). Research in the medical and social sciences has demonstrated the importance of social support in treatment adherence (11). In ADHD, a number of factors have been recognized, including general factors such as age and gender (12) and more specific factors such as duration of treatment and the presence of side effects (13).

Shared decision-making (SDM) is a well-established approach to improving the quality of health care (14,15) that involves clinicians providing information about treatment options and patients (or caregivers) providing information about values so that agreement on the best option for an individual patient can be reached (16). ADHD treatment guidelines recognize the importance of individual family values, concerns and preferences when deciding on treatment options (5,6), emphasizing that SDM is an essential component of ADHD care. Despite this, SDM during the treatment planning process for children newly diagnosed with ADHD has been shown to be limited (17). There is, therefore, a need to support clinicians to better share decisions with ADHD patients and their caregivers.

While a number of qualitative studies have explored patients’ and caregivers’ perspectives on ADHD medication, the clinical and policy application of their findings may be limited by the variety of study settings and populations and the relatively small individual study sample sizes. This review sought to synthesize the findings of these individual studies and was driven by the following question: ‘How can clinicians effectively share decisions about treatment for ADHD?’

Methods

Selection of studies for inclusion

We systematically searched five databases (MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO, SCOPUS and CINAHL) for relevant articles. These databases were chosen to maximize our ability to identify articles from both clinical and non-clinical journals. Search criteria comprised terms in three groups: methodology (search terms qualitative; focus group; interview; ethnography and thematic), focus (search terms medication; adherence; compliance; concordance and drug) and sample (search terms ADHD; ADD and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.). These search terms were combined using Boolean logic terms (OR within the groups and AND between groups). The search was restricted to articles written in English and published in peer-reviewed journals. Searches were conducted in October 2015 and were restricted to articles published since 1987, as this was the first use of the terminology attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, appearing in the revision of the third edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III-R) (18). It is well recognized that qualitative studies can be hard to identify, and that systematic reviews cannot rely on database searching alone (19). In light of this, we also manually searched bibliographies.

All identified titles and abstracts were screened by one researcher (SL). In addition, 10% were independently screened by a second researcher (MAR), with no discrepancies in selections. Studies that were excluded on the basis of abstracts alone typically did not use qualitative methodologies or did not focus on medication-taking experiences. Full-text articles were obtained for all selected abstracts and assessed for inclusion by two researchers (SL and MAR). Inclusion criteria were:

Focuses on individuals with ADHD

Explores medication-taking experiences of patients and/or their caregivers

Uses a qualitative methodology

Original research paper published in English in a peer-reviewed journal

Critical appraisal

Articles selected for inclusion were independently appraised by two authors (SL and MAR) using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) qualitative research checklist (20), an established tool for the appraisal of qualitative studies. Only articles scoring >50% were included in the synthesis.

In light of the debate surrounding the value of critical appraisal in qualitative syntheses, articles were additionally assessed with regard to their relevance to our research question, using the criteria set out by Dixon-Woods et al. (21). Articles included in our synthesis were classified as either ‘Key Papers’—where content closely mirrored the topic of our research question—or ‘Satisfactory Papers’—studies providing a smaller contribution to our synthesis. This classification was agreed upon by two researchers (SL and MAR) and is presented to allow readers to recognize the relative contribution of individual articles to the review

Synthesis

Included studies were synthesized using a meta-ethnographic approach. Meta-ethnography is an approach to the synthesis of qualitative studies pioneered by Noblit and Hare (22). It can be considered as similar to meta-analysis for quantitative research in that it aims to provide a comprehensive insight into the topic of research. However, meta-ethnography differs from meta-analysis in that it seeks to interpret the results of individual studies to create a new conceptual understanding of the subject. It has previously been used to synthesize findings about medication-taking experiences, including in mental illness (23).

Data were extracted from the included articles in the form of ‘first-order constructs’ and ‘second-order constructs’. First-order constructs are examples of direct quotations from research participants, while second-order constructs are the interpretations of these quotations offered by the original researchers. These definitions of first- and second-order constructs have been previously used in health research (24). For each second-order construct extracted from an article, one or more first-order constructs were collected to provide the reviewers with a clearer insight into the meanings. Tables of second-order constructs were collated, which were developed by the authors, into ‘third-order constructs’—higher level interpretations of the second-order constructs derived from the synthesis. Finally, these third-order constructs were developed into an explanatory model of the key themes.

Results

Systematic review

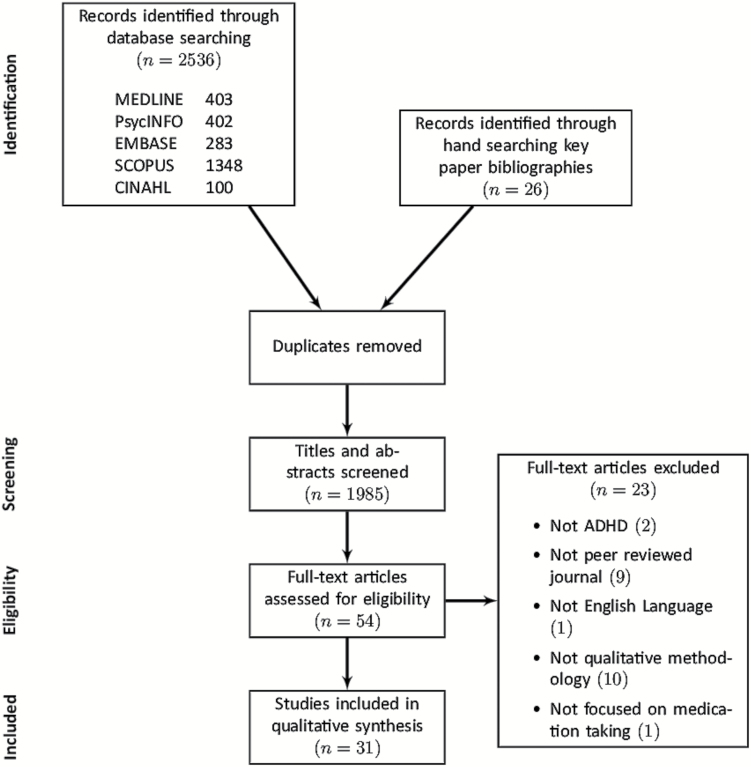

Our search identified a total of 1985 titles and abstracts for screening, of which 26 were identified via hand searching of the bibliographies of key papers, with the rest identified via database search. Full-text articles were obtained for 54 articles. After assessment, 31 articles were found to meet our inclusion criteria. Figure 1 illustrates the systematic review process using a flowchart based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidance (25). Table 1 details the 31 articles selected for inclusion in the synthesis (26–56), including their demographic data. The 31 studies selected for inclusion in our synthesis comprise studies of caregivers, paediatric patients and adult patients across seven different countries.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart.

Table 1.

Characteristics of articles included in the meta-ethnography

| Number | Author, Year | Study population | Sample size | Age of ADHD patients | Recruitment setting | Country | Methods | Relevance | Pharmaceutical funding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 126 | Ahmed et al., 2013 | Parents | 3 focus groups | Not stated | Recruitment agency | Australia | Focus groups | KP | No |

| 227 | Ahmed et al., 2014 | Parents | 3 focus groups | Range 3–12 at diagnosis | Recruitment agency | Australia | Focus groups | SAT | No |

| 328 | Avisar and Lavie-Ajayi, 2014 | Adolescents | 14 interviews | Range 12.5–16.5 | Private practice and acquaintances | Israel | Semi-structured interviews | KP | Not stated |

| 429 | Brinkman et al., 2009 | Parents | 12 focus groups | Range 6–17 | Community paediatric clinic | USA | Focus groups | KP | Yes |

| 530 | Brinkman et al., 2012 | Adolescents | 7 focus groups | Mean 15.1 | Community paediatric clinic | USA | Focus groups | KP | Yes |

| 631 | Bull and Whelan, 2006 | Parents | 10 interviews | Range 5–15 | ADHD support group | Australia | Semi-structured interviews | SAT | Not stated |

| 732 | Charach et al., 2006 | Parents | 3 focus groups | Range 7–15 | Specialty clinic | Canada | Focus groups | KP | No |

| 833 | Charach et al., 2014 | Parents and adolescents | 24 interviews | Range 12–15 | Specialty clinic | Canada | Semi-structured interviews | KP | No |

| 934 | Cheung et al., 2015 | Young adults with ADHD | 40 interviews | Range 16–23 | Paediatric and child psychiatryartments | Hong Kong | Semi-structured interviews | SAT | Yes |

| 1035 | Coletti et al., 2012 | Parents | 5 focus groups | Mean 9.35 | Child psychiatry clinic | USA | Focus groups | KP | Not stated |

| 1136 | Cormier, 2012 | Parents | 16 interviews | Range 6–11 | ADHD support group | USA | Semi-structured interviews | KP | No |

| 1237 | Davis, 2011 | Parents | 28 interviews | Range 6–15 | San Diego ADHD project | USA | Semi-structured interviews & survey | SAT | No |

| 1338 | dosReis et al., 2009 | Parents | 48 interviews | Mean 8.8 Range 6–16 | Primary care and specialty clinics | USA | Semi-structured interviews | SAT | No |

| 1439 | Hansen and& Hansen, 2006 | Parents | 10 interviews | Range 8–22 | Secondary care and ADHD advocacy group | Canada | Semi-structured interviews | KP | Not stated |

| 1540 | Jackson and Peters, 2008 | Parents | 10 interviews | Range 7–18 | Larger study | Not stated | Interviews | KP | Not stated |

| 1641 | Knipp, 2006 | Adolescents | 15 interviews | Not stated | High school | USA | Interviews | SAT | No |

| 1742 | Leggett and Hotham, 2011 | Parents and adolescents | 35 interviews | Mean 11.5 Range 6–17 | Paediatric clinics | Australia | Interviews and semi- structured questionnaire | SAT | No |

| 1843 | Leslie et al., 2007 | Parents | 28 interviews | Mean 9.5 Range 6–16 | Primary care | USA | Semi-structured interviews | SAT | No |

| 1944 | Loe and Cuttino, 2011 | College students | 16 interviews | Mean 20.75 Range 19–22 | Private liberal arts college | USA | Interviews | SAT | No |

| 2045 | Matheson et al., 2013 | Adults with ADHD | 30 interviews | Mean 34.9 Range 18–57 | Outpatient clinic and ADHD charity | UK | Semi-structured interviews and survey | SAT | Yes |

| 2146 | Meaux et al., 2006 | College students | 15 interviews | Range 18–21 | University | USA | Semi-structured interviews | KP | Not stated |

| 2247 | Mills, 2011 | Parents | 19 interviews | Not stated | School district | USA | Semi-structured interviews | KP | Not stated |

| 2348 | O’Callaghan, 2014 | Adults with ADHD | 18 interviews | Range 19–64 | ADHD mentoring scheme and support group | Not stated | Semi-structured interviews | SAT | Not stated |

| 2449 | Searight, 1996 | Children | 25 interviews | Range 5–16 | Paediatric ADHD clinic | USA | Interviews and ethnographic inquiry | SAT | Not stated |

| 2550 | Sikirica et al., 2014 | Parents and adolescents | 66 interviews | Mean 11.9 Range 6–17 | Online panel | 8 European countries | Semi-structured interviews | SAT | Yes |

| 2651 | Singh, 2003 | Parents (fathers) | 61 interviews | Mean 9.5 Range 6–12 | Secondary care clinic | USA | Interviews using a picture-based method | SAT | Not stated |

| 2752 | Singh et al., 2010 | Adolescents | 16 interviews | Range 9–14 | Secondary care | UK | Focus groups and one-one interviews | KP | No |

| 2853 | Taylor et al., 2007 | Parents | 33 interviews | Not stated | University database and ADHD support group | Australia | Semi-structured interviews | SAT | No |

| 2954 | Travell and Visser, 2006 | Parents and children | 17 interviews | Range 11–16 | Local education authority | UK | Semi-structured interviews | SAT | Not stated |

| 3055 | Walker-Noack et al., 2009 | Youth aged 10–21 | 6 focus groups | Mean 14.3 Range 10–21 | Schools | Canada | Focus groups | SAT | No |

| 3156 | Wong et al., 2009 | Young adults aged 15–24 | 15 interviews | Mean 18.2 Range 15–24 | Paediatric and child and adult mental health clinics | UK | In-depth interviews | SAT | Not stated |

Critical appraisal

All assessed articles scored above 50% on the CASP rating, and none was, therefore, excluded on grounds of poor quality. On assigning relevance scores, 13 articles were assigned as key papers and the remaining 18 designated satisfactory. These results are detailed in Table 1 (key papers denoted KP, satisfactory articles denoted SAT). It was noted that some included articles were supported by pharmaceutical industry funding, and this has been presented in Table 1 to demonstrate the spread.

Data extraction and synthesis

In total, 31 second-order constructs emerged from the original articles. These are detailed in Table 2, along with the articles from which they arise. Once the second-order constructs had been established by the review team, these were discussed in meetings and mapped in a series of diagrams to develop third-order constructs that describe the major themes shaping patients’ and caregivers’ experiences with medication. These are presented here and, to more clearly describe our findings, have been used to categorize individual second-order constructs:

Table 2.

Third-order constructs

| Second-order construct | Articles | |

|---|---|---|

| Coming to terms with ADHD | ||

| Varying parental understanding of ADHD | 2, 4, 7, 10, 11, 15, 18, 19, 22, 26, 28 | |

| Intrinsic beliefs about medication | 4, 7, 12, 13, 17, 22, 25, 26, 27, 31 | |

| Coming to terms with the diagnosis | 4, 11, 22, 28 | |

| Fear of stigma | 4, 7, 10, 11, 21, 27, 30 | |

| Considering medication as a last resort | 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 15, 18, 22, 28 | |

| Anticipated concerns about medication | ||

| Fear of addiction | 1, 4, 18, 25 | |

| Concerns about long-term consequences of medication | 1, 2, 8, 14, 28 | |

| Concerns about anticipated side effects | 2, 4, 6, 7, 9, 11, 17, 23 | |

| Worries about the financial cost of medication | 18, 25 | |

| External influences | ||

| Influence of family and friends | 1, 4, 7, 15, 18, 22 | |

| Influence of the media | 2, 4, 7, 15, 22, 28 | |

| Content of information provided | 2, 10, 11, 12, 31 | |

| Relationships with health professionals | 1, 4, 10, 18, 20, 21, 23, 28, 31 | |

| Child–parent relationship | 3, 5, 22, 31 | |

| Relationships with school staff | 4, 15, 28, 29, 31 | |

| Spousal conflicts | 4, 7, 22, 28 | |

| Experiences of misuse of ADHD medications | 21 | |

| Experiences of the effects of medication | ||

| Functional effects of medication | Impact on behaviour | 1, 11, 14, 15, 27, 30 |

| Impact on academic performance | 1, 3, 5, 6, 8–11, 14, 16, 17, 21, 23, 27, 30, 31 | |

| Impact on social skills and interpersonal relationships | 1, 3, 5, 8, 10, 16, 17, 20, 21, 23 | |

| Impact on creativity | 5, 23 | |

| Functional impact of untreated ADHD | 1, 4, 5, 9, 10, 18, 22, 23, 24, 27, 30, 31 | |

| Experiences of actual side effects | 1, 3, 6–9, 14, 15, 18, 21, 24, 25, 29, 30, 31 | |

| The development of self-management | ||

| Situational use of medication | 1, 5, 10, 19, 20, 21, 25 | |

| Persistent doubts about medication use | 4, 14, 22 | |

| Experimenting with medication regime | 4, 5, 7, 10, 14, 21, 28, 31 | |

| Developing autonomy as an individual | 3, 5, 8, 29 | |

| Making future plans for medications | 14, 19, 25, 27, 31 | |

| Finding alternatives to medications | 19, 20 | |

| Consideration of trade-offs | 3, 5, 7, 8, 11, 12, 14, 16, 19, 20, 21, 28 | |

Coming to terms with ADHD

Anticipated concerns about medication

Experiences of the effects of medication

External influences

The development of self-management

Coming to terms with ADHD

For many caregivers, the diagnosis of ADHD was difficult to accept. Many articles noted that the decision to start medication was preceded by an acceptance of ADHD as a biological problem. Caregivers’ decisions about pharmacotherapy were also shaped by their beliefs about medication. For patients, the process of coming to terms with ADHD was often reflected in how ADHD or medication impacted their sense of identity—as one college student stated: ‘I don’t like the idea … that the person I’m most like is the person who I am when I am taking medication … But I find more and more, that when I don’t take it, I don’t act as someone that I think that I am or who I’d like to be …’. (50). The fear of stigma was also commonly cited as a concern, particularly for parents and early on after receiving a diagnosis. A number of articles also described medications as a last resort in ADHD, considered a reasonable option only when other measures had been exhausted.

Anticipated concerns about medication

Both patients and caregivers had concerns about the long-term impact of medication. One parent stated: ‘I don’t know how it’s [medication] going to affect him in the future? I don’t know how it will affect his kids’ (39). Anticipated concerns also included short-term worries such as fears about potential side effects before commencing medication as highlighted in this quote: ‘My fear is that he would kind of “zombie out”’ (41). These anticipated concerns influenced decisions about whether or not to start or continue using ADHD medication. Many of these anticipated concerns were not grounded in any objective information from clinicians or scientific literature but came about from informal sources such as friends and family or the media.

External influences

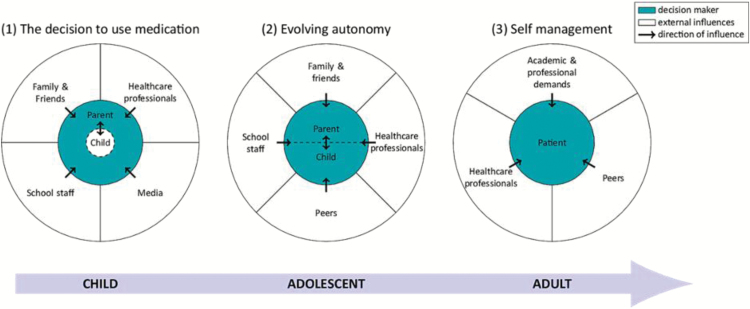

Parents’ decisions to commence medication were often influenced by external parties, including family and friends, and school staff—‘It was like the teachers were pushing me, pushing me. Get him meds, get him meds’ (35). The relative importance of external influences changed during treatment as the patient matured, as illustrated in Figure 2. For children (and their parents), media was a powerful force. In both children and adolescents, school staff played an important role, and for adults, higher education and employment were important factors.

Figure 2.

Model illustrating the patient’s changing relationship with ADHD medication over time.

Experiences of the effects of medication

The experience of both positive and negative effects of medication had a profound influence on patients and caregivers decisions about continuing medication. Patients and caregivers considered the balance of the benefits of medication against side effects, as well as the impact of untreated ADHD, which could equally have positive and negative domains. There were many examples of both physical and mental health effects of the medication. For some young people, the medications caused difficulties regarding their identity and also regarding control over their lives. For example, one young person reported: ‘Like the tablets are taking over me and I can’t control myself, the tablets are in control of me.’ (54).

The development of self-management

Several articles noted that the child’s involvement in medication decisions increased as they matured—as one adolescent said: ‘When I was younger, I didn’t have a whole lot of say-so in what was going on. … It was just, “Take your medicine.” As I got older, they started talking to me more. … It got better as I got older’ (36). In addition, many articles highlighted that caregivers and patients experimented with their medication regime to aid decision-making. This process often culminated in patients using medication selectively to help them meet the demands placed upon them. As one college student put it: ‘It’s good for working but … I don’t really feel like being on it all the time I guess’ (50).

Our synthesis demonstrates that medication-taking experiences are often represented as a series of ‘trade-offs’. This theme recurred either explicitly or implicitly across several articles. When making decisions about medications, patients and caregivers balanced the benefits of medication against negative consequences, including side effects, stigma and the impact of medication on identity. The experience of medication-taking as a set of trade-offs was echoed by both patients and caregivers and persisted throughout different age groups of patients. Often this experience was a major driver towards the development of self-management, as patients chose to take their medication in a way that best balanced their own personal set of trade-offs.

We developed an explanatory model depicting the interplay of several of the second- and third-order constructs in shaping the medication-taking experience. The model illustrates the evolution of external influences on decisions about medication-taking as the patient and caregivers make their journey through treatment and as the patient matures. The coloured circles in the model show how the primary decision maker changes over time. Many articles highlighted that the parent or caregiver is originally the main decision maker with regard to medication, though they are influenced by the behaviours and opinions of the child. This relationship then moves to a pattern of shared decision-making between the parent and the adolescent patient, illustrated in the second circle. Finally, the now adult patient may move to a position of self-management, becoming the primary decision maker in the third circle.

This model also illustrates some of the external influences on decisions about medication, and how these influences can change over time. Several included studies dealt with the initial decision to start medication to treat ADHD. This decision was most often taken by parents/caregivers and was often influenced by pressures from school staff and the opinion of family and friends. Parents were also influenced by the portrayal of both medication and ADHD in the media. In the adolescent phase, during which patients and caregivers negotiate whether to continue medication, patients are influenced by the opinions of their peers and the opinions of school staff, family and friends remain important. However, the influence of media depictions of medication or ADHD seems to lose their influence at this stage. In the adult phase, when the patient moves towards a position of self-managing their medication, the influence of varying academic or professional demands become more important. The relationship between patient, caregiver and healthcare professional plays a role at all stages.

The concept of ‘trade-offs’ and the explanatory model combine to give a conceptual picture of the changing experience of medication-taking in ADHD. ‘Trade-offs’ are largely internal experiences that remain fairly constant throughout the stages of the treatment journey, even if different constructs bore more or less influence at different times. Conversely, the model of evolving decision-making represents some of the external pressures, which change more consistently as the patient matures. The model is not intended to be a summary of the third-order constructs identified in our synthesis; indeed it contains a combination of both second- and third-order constructs. The relationships between individual second- and third-order constructs are outlined in Table 2, which also identifies the included articles that support them. Rather, it is intended to provide a conceptual summary of the complex and evolving processes involved in making decisions about medication-taking for ADHD, as well as illustrating the elements that were consistently highlighted by participants in the included studies.

Discussion

Summary

This synthesis of qualitative studies of medication-taking in ADHD demonstrates that patients’ and caregivers’ experiences can be broadly described by five main themes: Coming to terms with ADHD, Anticipated concerns about medication, Experiences of the effects of medication, External influences and the development of self-management. In addition, the explanatory model described above illustrates that the experience of medication-taking transforms as the patient matures and the locus of decision-making shifts from caregivers to patients. The longitudinal nature of this illustration demonstrates that to support patients in decision-making, clinicians must tailor their interventions to the appropriate stage of their disease experience.

Strengths and limitations

One of the limitations of this work is that we chose to combine data from studies involving children, adolescents and adults. This may have prevented us from appreciating the subtleties of the different experiences of children and adults with ADHD. However, we have attempted to overcome this by producing a longitudinal explanatory model, allowing readers to appreciate that experiences can vary considerably with age. While the explanatory model described in this article depicts a medication-taking journey starting in childhood and continuing into adulthood, many key findings such as the role of trade-offs or the development of self-management could be relevant to patients with ADHD diagnosed and treated later in life. In addition, the majority of articles in this synthesis originated in the USA, which could limit the generalizability of the findings to countries with different state health models and where drugs are less likely to be marketed directly to the public (57). However, with evidence of increasing prescribing tendencies for ADHD in the UK (58), a thorough understanding by clinicians of patients’ and carers’ concerns surrounding medication-taking becomes imperative. The review team in this study included clinically trained researchers which strengthens the clinical focus to our investigation.

Implications for research and practice

This review demonstrates that decisions about initiating and persisting with medications for ADHD are highly complex and are affected by a variety of factors, both internal and external. These findings match the results of previous studies that have described the complexity of treatment decisions and the importance of social-, medical- and treatment-related factors (12,13,59). A previous review exploring non-adherence to pharmacological treatments also proposed a model to guide practitioners working with patients. It proposed three clinical actions: ensuring that patients have the right information, helping patients become motivated to commit to treatment and assisting patients to overcome practical barriers (60). These actions broadly fit with the model generated in this review, which contains additional, disease-specific information. The evolving nature of decision-making as patients move into adulthood and the importance of educational and social functioning are particularly important features of adherence in ADHD compared with the broader adherence literature.

Clinicians involved in ADHD management should be aware of the importance of these factors, and the fact that they evolve from predominantly parental concerns in childhood, to more autonomous decisions in adolescence and adulthood. It is particularly important for clinicians to recognize that these decisions often involve compromises. It is likely that for a given patient, there will factors that both encourage and discourage them towards a choice to take medications. In the case of ADHD, this may be especially relevant because of the variation in clinical guidelines internationally. By recognizing this uncertainty, clinicians can allow individuals to voice their unease and consider all available options. Similarly, the relationships between patients and their caregivers evolve with time of life, as do the external influences on the individual and family unit. Clinicians can acknowledge this shifting dynamic and recognize the autonomy of adolescent patients by including them more in treatment decisions. Furthermore, they can probe individuals and families about family, peer, school and employer factors according to the stage of development of the patient. By voicing the influencing factors and acknowledging them in discussions, patient–clinician discussions can focus on key areas that will help to shape treatment choices.

Future research in this area might further explore the emerging family issues including sibling and parent dynamics and the types of media portrayals that influence perceptions of ADHD and its treatment. Although a proportion of articles included in this study were funded by pharmaceutical industry funding, a more detailed analysis of the effect of this funding was beyond the scope of this review and might be investigated in further studies. In addition, a clinical tool to help support decision-making could also be developed and tested, using the findings from this review.

This synthesis conceptualizes the evolving experiences of using medications for ADHD. Consideration of these findings by clinicians may allow better engagement with both patients and caregivers to support shared decision-making.

Declaration

Funding: none.

Contributions: SL, NRL and MAR were involved in study design and analysis and interpretation of data. SL and MAR drafted the manuscript and NRL critically revised it for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final version.

Conflict of interest: NRL and MAR were supported by fellowships from the National Institute of Health Research.

References

- 1. Rappley MD. Clinical practice. Attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder. N Engl J Med 2005; 352: 165–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fayyad J, De Graaf R, Kessler R, et al. Cross-national prevalence and correlates of adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Br J Psychiatry 2007; 190: 402–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Harpin V, Mazzone L, Raynaud JP, Kahle J, Hodgkins P. Long-term outcomes of ADHD: a systematic review of self-esteem and social function. J Atten Disord 2016; 20: 295–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Faraone SV, Biederman J, Spencer TJ, Aleardi M. Comparing the efficacy of medications for ADHD using meta-analysis. MedGenMed 2006; 8: 4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Subcommittee on Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder; Steering Committee on Quality Improvement and Management , Wolraich M, Brown L, Brown RT, et al. ADHD: clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. Pediatrics 2011; 128: 1007–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. NICE. Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: Diagnosis and Management.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg72 (accessed on 15 July 2016).

- 7. Gajria K, Lu M, Sikirica V, et al. Adherence, persistence, and medication discontinuation in patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder—a systematic literature review. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2014; 10: 1543–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Horton-Salway M. Repertoires of ADHD in UK newspaper media. Health (London) 2011; 15: 533–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sabaté E. (ed.). Adherence to Long-Term Therapies: Evidence for Action. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Horne R, Weinman J, Barber N, et al. Concordance, adherence and compliance in medicine taking. London, UK: NCCSDO, 2005, pp. 40–6. [Google Scholar]

- 11. DiMatteo MR. Social support and patient adherence to medical treatment: a meta-analysis. Health Psychol 2004; 23: 207–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Barner JC, Khoza S, Oladapo A. ADHD medication use, adherence, persistence and cost among Texas Medicaid children. Curr Med Res Opin 2011; 27(suppl 2): 13–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Toomey SL, Sox CM, Rusinak D, Finkelstein JA. Why do children with ADHD discontinue their medication?Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2012; 51: 763–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Barry MJ, Edgman-Levitan S. Shared decision making–pinnacle of patient-centered care. N Engl J Med 2012; 366: 780–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Elwyn G, Laitner S, Coulter A, et al. Implementing shared decision making in the NHS. BMJ 2010; 341: c5146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. O’Connor AM, Llewellyn-Thomas HA, Flood AB. Modifying unwarranted variations in health care: shared decision making using patient decision aids. Health Affairs 2004; 63–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Brinkman WB, Hartl J, Rawe LM, et al. Physicians’ shared decision-making behaviors in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder care. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2011; 165: 1013–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lange KW, Reichl S, Lange KM, Tucha L, Tucha O. The history of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Atten Defic Hyperact Disord 2010; 2: 241–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Greenhalgh T, Peacock R. Effectiveness and efficiency of search methods in systematic reviews of complex evidence: audit of primary sources. BMJ 2005; 331: 1064–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP). 10 Questions to Help You Make Sense of Qualitative Research. Qualitative Research Checklist. http://media.wix.com/ugd/dded87_29c5b002d99342f788c6ac670e49f274.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2015).

- 21. Dixon-Woods M, Sutton A, Shaw R, et al. Appraising qualitative research for inclusion in systematic reviews: a quantitative and qualitative comparison of three methods. J Health Serv Res Policy 2007; 12: 42–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Noblit GW, Hare RD.Meta-Ethnography: Synthesizing Qualitative Studies. Newbury Park, CA: Sage, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Malpass A, Shaw A, Sharp D, et al. ‘Medication career’ or ‘moral career’? The two sides of managing antidepressants: a meta-ethnography of patients’ experience of antidepressants. Soc Sci Med 2009; 68: 154–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Atkins S, Lewin S, Smith H, et al. Conducting a meta-ethnography of qualitative literature: lessons learnt. BMC Med Res Methodol 2008; 8: 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ 2009; 339: b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ahmed R, Borst J, Wei YC, Aslani P. Parents perspectives about factors influencing adherence to pharmacotherapy for ADHD. J Atten Disord 2013; 21: 91–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ahmed R, Borst JM, Yong CW, Aslani P. Do parents of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) receive adequate information about the disorder and its treatments? A qualitative investigation. Patient Prefer Adherence 2014; 8: 661–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Avisar A, Lavie-Ajayi M. The burden of treatment: listening to stories of adolescents with ADHD about stimulant medication use. Ethical Hum Psychol Psychiatry 2014; 16: 37. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Brinkman WB, Sherman SN, Zmitrovich AR, et al. Parental angst making and revisiting decisions about treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics 2009; 124: 580–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Brinkman B, Sherman N, Zmitrovich R, et al. In their own words: adolescent views on ADHD and their evolving role managing medication. Acad Paediatr 2012; 12: 53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bull C, Whelan T. Parental schemata in the management of children with attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder. Qual Health Res 2006; 16: 664–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Charach A, Skyba A, Cook L, Antle BJ. Using stimulant medication for children with ADHD: what do parents say? A brief report. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2006; 15: 75–83. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Charach A, Yeung E, Volpe T, Goodale T, Dosreis S. Exploring stimulant treatment in ADHD: narratives of young adolescents and their parents. BMC Psychiatry 2014; 14: 110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cheung KKW, Wong ICK, Ip P, et al. Experiences of adolescents and young adults with ADHD in Hong Kong: treatment services and clinical management. BMC Psychiatry 2015; 15: 95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Coletti DJ, Pappadopulos E, Katsiotas NJ, Berest A, Jensen PS, Kafantaris V. Parent perspectives on the decision to initiate medication treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2012; 22: 226–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cormier E. How parents make decisions to use medication to treat their child’s ADHD: a grounded theory study. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc 2012; 18: 345–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Davis CC, Claudius M, Palinkas LA, Wong JB, Leslie LK. Putting families in the center: family perspectives on decision making and ADHD and implications for ADHD care. J Atten Disord 2012; 16: 675–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. DosReis S, Mychailyszyn MP, Evans-Lacko SE, et al. The meaning of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder medication and parents’ initiation and continuity of treatment for their child. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2009; 19: 377–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hansen DL, Hansen EH. Caught in a balancing act: parents’ dilemmas regarding their ADHD child’s treatment with stimulant medication. Qual Health Res 2006; 16: 1267–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Jackson D, Peters K. Use of drug therapy in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): maternal views and experiences. J Clin Nurs 2008; 17: 2725–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Knipp DK. Teens’ perceptions about attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder and medications. J Sch Nurs 2006; 22: 120–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Leggett C, Hotham E. Treatment experiences of children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Paediatr Child Health 2011; 47: 512–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Leslie LK, Plemmons D, Monn AR, Palinkas LA. Investigating ADHD treatment trajectories: listening to families’ stories about medication use. J Dev Behav Pediatr 2007; 28: 179–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Loe M, Cuttino L. Grappling with the medicated self: the case of ADHD college students. Symb Interact 2008; 31: 303. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Matheson L, Asherson P, Wong IC, et al. Adult ADHD patient experiences of impairment, service provision and clinical management in England: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res 2013; 13: 184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Meaux JB, Hester C, Smith B, Shoptaw A. Stimulant medications: a trade-off? The lived experience of adolescents with ADHD. J Spec Pediatr Nurs 2006; 11: 214–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Mills I. Understanding parent decision making for treatment of ADHD. School Soc Work J 2011; 36: 41. [Google Scholar]

- 48. O’Callaghan P. Adherence to stimulants in adult ADHD. Atten Defic Hyperact Disord 2014; 6: 111–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Searight HR. Perceptions of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and its treatment among children and adolescents. J Med Humanit 1996; 17: 51–66. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Sikirica V, Flood E, Dietrich CN, et al. Unmet needs associated with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in eight European countries as reported by caregivers and adolescents: results from qualitative research. Patient 2015; 8: 269–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Singh I. Boys will be boys: fathers’ perspectives on ADHD symptoms, diagnosis, and drug treatment. Harv Rev Psychiatry 2003; 11: 308–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Singh I, Kendall T, Taylor C, et al. Young people’s experience of ADHD and stimulant medication: a qualitative study for the NICE guideline on National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Child Adolesc Ment Health 2010; 15: 186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Taylor M, ODonoghue T, Houghton S. To medicate or not to medicate? The Decision making process of western Australian parents following their childs diagnosis with an attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Intl J Disabil Dev Educ 2006; 53: 111–28. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Travell C, Visser J. ADHD does bad stuff to you: young people’s and parents’ experiences and perceptions of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Emot Behav Diffic 2006; 11: 205–16. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Walker-Noack L, Corkum P, Elik N, Fearon I. Youth perceptions of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and barriers to treatment. Can J Sch Psychol 2013; 28: 193–218. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Wong ICK, Asherson P, Bilbow A, et al. Cessation of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder drugs in the young (CADDY)—a pharmacoepidemiological and qualitative study. Health Technol Assessm 2009; 13: 1–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Ventola CL. Direct-to-consumer pharmaceutical advertising: therapeutic or toxic?P T 2011; 36: 669–84. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Beau-Lejdstrom R, Douglas I, Evans SJ, Smeeth L. Latest trends in ADHD drug prescribing patterns in children in the UK: prevalence, incidence and persistence. BMJ Open 2016; 6: e010508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Adler LD, Nierenberg AA. Review of medication adherence in children and adults with ADHD. Postgrad Med 2010; 122: 184–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. DiMatteo MR, Haskard-Zolnierek KB, Martin LR. Improving patient adherence: a three-factor model to guide practice. Health Psychol Rev 2012; 6: 74–91. [Google Scholar]