Abstract

Background

Despite the high prevalence of osteoarthritis and the prominence of primary care in managing this condition, there is no systematic summary of quality indicators applicable for osteoarthritis care in primary care settings.

Objectives

This systematic review aimed to identify evidence-based quality indicators for monitoring, evaluating and improving the quality of care for adults with osteoarthritis in primary care settings.

Methods

Ovid MEDLINE and Ovid EMBASE databases and grey literature, including relevant organizational websites, were searched from 2000 to 2015. Two reviewers independently selected studies if (i) the study methodology combined a systematic literature search with assessment of quality indicators by an expert panel and (ii) quality indicators were applicable to assessment of care for adults with osteoarthritis in primary care settings. Included studies were appraised using the Appraisal of Indicators through Research and Evaluation (AIRE) instrument. A narrative synthesis was used to combine the indicators within themes. Applicable quality indicators were categorized according to Donabedian’s ‘structure-process-outcome’ framework.

Results

The search revealed 4526 studies, of which 32 studies were reviewed in detail and 4 studies met the inclusion criteria. According to the AIRE domains, all studies were clear on purpose and stakeholder involvement, while formal endorsement and use of indicators in practice were scarcely described. A total of 20 quality indicators were identified from the included studies, many of which overlapped conceptually or in content.

Conclusions

The process of developing quality indicators was methodologically suboptimal in most cases. There is a need to develop specific process, structure and outcome measures for adults with osteoarthritis using appropriate methodology.

Keywords: Osteoarthritis, primary care, quality of health care, quality assurance, quality improvement, quality indicators

Introduction

Osteoarthritis is a common chronic condition and one of the leading causes of poor quality of life and disability worldwide (1). In Ontario, Canada, the overall prevalence of osteoarthritis is 24.2%, while ~48.8% of people aged 75–89 years have osteoarthritis (2). Osteoarthritis is typically diagnosed on the basis of radiographic imaging and clinical findings (1). Symptomatic osteoarthritis is defined by the presence of joint symptoms, including pain, aching or stiffness, with radiological confirmation (1). Prior study results show that osteoarthritis is associated with a high economic burden, attributable to the effects of disability, the presence of comorbid disease and the expenses of treatment (3).

Osteoarthritis is frequently diagnosed and treated in primary care settings; it is the second most common diagnosis among adults leading to consultations with their general practitioners (4). Even though it is one of the most prevalent conditions, there has been little evaluation of the quality of care provided for adults with osteoarthritis in primary care settings.

Assessment and monitoring of care quality has become crucial for health care systems worldwide to enhance the accountability of health care providers, to improve resource allocation efficiency, to identify and minimize medical errors and to improve health outcomes (5,6). The assessment and monitoring of care quality can be achieved by using quality indicators, which are based on standards of care and the best available evidence (5). Health care quality indicators are powerful tools that can guide efforts to improve patient care (5).

Quality indicators are defined as ‘a measurement tool, screen or flag that is used as a guide to monitor, evaluate and improve the quality of client care, clinical services, support services and organizational functions that affect patient outcomes’ (7). Data generated from these measures can be used to assess past performance, identify suboptimal practices and plan improvements. Quality indicators indicate potential problems that might need addressing, usually manifested by perceived unacceptable variation in care or statistical outliers (5). Donabedian (8) has conceptualized the assessment of quality through examining the structures, processes and outcomes of care, and many quality indicators have been classified using this framework.

The literature suggests that quality indicators should be evidence based and be derived from the academic literature. However, when scientific evidence is lacking, quality indicators can be defined by an expert panel of professionals by means of consensus techniques based on their experience (6). Evidence suggests that the systematic method of combining scientific evidence and expert opinion is the most rigorous way of developing quality indicators (5).

Despite the growing interest in assessing the quality of care for osteoarthritis, there has been little evaluation of the quality of care for osteoarthritis in primary care settings. This systematic review aimed (i) to identify evidence-based and valid quality indicators feasible for monitoring, evaluating and improving the quality of care for osteoarthritis among adults in primary care settings and (ii) to critically appraise a set of identified quality indicators, using Appraisal of Indicators through Research and Evaluation (AIRE) instrument.

Methods

We conducted a systematic literature review to identify existing quality indicators for primary care of osteoarthritis both in Canada and internationally.

Search strategy

A systematic literature search was conducted using Ovid MEDLINE and Ovid EMBASE databases from 2000 to 2015, restricted to English articles of human studies of people aged 18 years or older. The search terms used combined keywords and medical subject headings for osteoarthritis and quality indicators. The following search terms were used to identify studies related to quality indicators development: ‘performance indicator(s)/measure(s)’, or ‘quality indicator(s)/measure(s)’, or ‘benchmark’, or ‘report card’, or ‘quality of health care’, or ‘clinical guideline’, or ‘quality assurance’. To identify studies related to osteoarthritis care, we used the following search terms: ‘osteoarthritis’, ‘arthritis, degenerative’, ‘osteoarthritis, hip’, ‘osteoarthritis, spine’ and ‘osteoarthritis, knee’. The results from these two search steps were then combined (Supplementary Table 1).

In addition, a grey literature search was conducted to find information about quality indicator development initiatives that were not published in peer-reviewed journals. For that purpose, we searched available public repositories including the National Quality Measures Clearinghouse (NQMC; http://www.qualitymeasures. ahrq.gov) and the National Quality Forum (NQF; http://www. qualityforum.org). Additionally, we looked for existing indicators at web sites of major organizations involved in quality measurement and reporting indicators for assessing the quality of care among patients with osteoarthritis, including the RAND Health Corporation/Assessing Care of Vulnerable Elders (ACOVE), American College of Rheumatology (ACR), Canadian Rheumatology Association (CRA), and American Medical Association (AMA) and AMA-convened Physician Consortium for Performance Improvement (PCPI).

Study selection

The literature suggests the most rigorous way of developing quality indicators is through a systematic literature search combined with consensus techniques (5,9). Where possible, quality indicators should be derived from scientific evidence. The stronger the evidence, the stronger the potential benefit of quality indicators in terms of increase in the likelihood of achieving the best possible clinical outcomes (5,9). The main reasons for developing measures using consensus techniques include synthesizing accumulated expert opinion, enhancing decision-making, facilitating development of indicators where evidence alone is insufficient and identifying areas of care where there is controversy or uncertainty (5).

Therefore, the articles were included for the purpose of this study if both inclusion criteria were met:

The study methodology combined a systematic literature search/development of indicators from clinical guidelines with assessment of quality indicators by an expert panel;

The study provided quality indicators applicable to the provision of primary care for adults with osteoarthritis.

The articles identified were entered in a bibliographical database and duplicates were removed. One of the reviewers (YP) checked for the selected keywords in the title, abstract and subject heading of the articles. The resulting studies were included for full-text review. Two reviewers (YP and YS) independently conducted full-text review according to the inclusion criteria. Also, the references of selected articles were screened for other relevant studies that had not been found in the electronic search. The resulting set of articles was included in the methodological assessment process. The level of agreement between reviewers evaluating studies for inclusion and undertaking methodological assessments was assessed using the kappa statistic (10).

Methodological assessment

We used the AIRE instrument for the methodological assessment of the quality of the included articles (11). It is a validated instrument that has been used previously in similar peer-reviewed studies (12,13). The AIRE instrument contains 20 items, subdivided into four domains: (i) purpose, relevance and organizational context; (ii) stakeholder involvement; (iii) scientific evidence; and (iv) additional evidence, formulation, usage.

Two authors (YP and YS) independently appraised the included sets of indicators with the AIRE instrument. The AIRE instrument was completed for a total set of quality indicators against each instrument item because publications usually gave information about the development and scientific evidence of the total set of indicators instead of for each indicator separately (12,13). Each item of the instrument has a score ranging from 1 to 4 with: 1 = strongly disagree (confident that the criterion has not been fulfilled or no information was available); 2 = unsure whether the criterion has been fulfilled (answer ‘disagree’, depending on the extent to which the criterion has been fulfilled); 3 = unsure whether the criterion has been fulfilled (answer ‘agree’, depending on the extent to which the criterion has been fulfilled); and 4 = strongly agree (confident that the criterion has been fulfilled) (11).

Scores for each of the four domains were calculated by summing up all the scores of the individual items in a category and standardizing the total as a percentage of the maximum possible score for that domain. The maximum possible score for each domain was calculated by multiplying the maximum score per item (4 points) by the number of items in that domain (3,5,9) and the number of appraisers (2). Similarly, the minimum possible score was calculated by using the minimum score per item (1).

The standardized category score is the total score per domain minus the minimum possible score for that domain, divided by the maximum possible score minus the minimum possible score, all multiplied by 100%. The standardized score ranges between 0% and 100%, and a score of 50% and higher indicates a higher methodological quality for each domain of the instrument (13).

We conducted and reported this study according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) statement.

Data extraction

A structured data extraction form was used to describe the selected studies with respect to the quality of osteoarthritis care among adults in primary care settings. The extraction information consisted of the title of the paper and the publication date; summary of the indicator selection process; and description of quality indicators, including type, numerator and denominator of quality indicator. The identified quality indicators were organized according to Donabedian’s ‘structure-process-outcome’ framework (8). A narrative synthesis was used to combine the indicators within themes.

Results

Search results

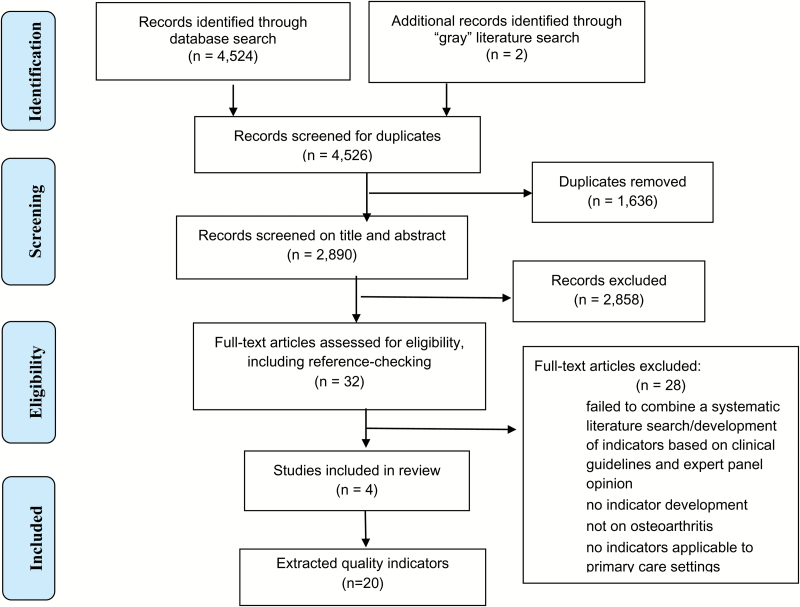

The systematic literature review identified 4524 potentially relevant studies from OVID MEDLINE and OVID EMBASE (Fig. 1). Two additional publications were identified through grey literature searching. After the review of titles/abstracts, only 31 publications were deemed potentially relevant. The full texts of these publications were obtained for the review. One publication was derived after tracking the references. Of these, 28 publications were excluded primarily because of the inability to meet inclusion criteria. Finally, four publications were included in the review (kappa = 0.92; very good agreement) (14).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram for selection of studies for the review.

Study characteristics

The studies included in the review are summarized in Table 1. The included studies were obtained from the USA or Europe. All four articles used a combination of literature review/development of quality indicators from clinical guidelines and some form of consensus technique to derive a final set of quality indicators. One of the studies was focused on assessing care for vulnerable elders with osteoarthritis (15), while the rest focused on the care of osteoarthritis among adults (16–18). All included studies provided quality indicators applicable to assessing the care for osteoarthritis in primary care settings.

Table 1.

Article characteristics

| First author/organization | Organization/initiative | Country/year | Study design |

|---|---|---|---|

| MacLean (15) | RAND/ACOVE | USA/2007 | Literature review for identifying candidate indicators; RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method for critical appraisal of indicators |

| Pencharz (16) | Arthritis Foundation | USA/2004 | Literature review for identifying candidate indicators; consensus technique for critical appraisal of indicators |

| PCPI (17) | Physician Consortium for Performance Improvement/American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons | USA/2006 | Literature/clinical guidelines review for identifying candidate indicators; consensus technique for critical appraisal of indicators |

| EUMUSC.net (18) | The European Musculoskeletal Conditions Surveillance and Information Network project (EUMUSC.net project) | EU member states/2012 | Literature/clinical guidelines review for identifying candidate indicators; modified Delphi technique for critical appraisal of indicators by panellists from 9 European countries |

Methodological quality

The methodological quality of the included studies varied according to the AIRE instrument domains’ scores (Tables 2 and 3). All studies were clear on the first AIRE instrument domain, demonstrating good evidence for describing the purpose of quality indicators development and the patient population to whom they were meant to apply, as well as presenting the indicator selection criteria and applicability of measures.

Table 2.

Appraisal of Indicators through Research and Evaluation Instrument Score

| First author | Appraisal of Indicators through Research and Evaluation Instrument-Standardized Score (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Purpose, relevance and organizational context | Stakeholder involvement | Scientific evidence | Additional evidence, formulation and usage | |

| MacLean (15) | 88 | 73 | 84 | 82 |

| Pencharz (16) | 78 | 67 | 84 | 67 |

| PCPI (17) | 86 | 94 | 78 | 87 |

| EUMUSCUS.net (18) | 86 | 76 | 84 | 85 |

Table 3.

Quality indicators for osteoarthritis care

| Indicator | Source(s) | Description and/or numerator, denominator of indicator | Scientific validity | Reliability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structure indicators | ||||

| Access | EUMUSC.net, 2012 | Description: All professionals managing patients with osteoarthritis at a primary care setting should have continuous access to education on important preventive and therapeutic strategies in the management of osteoarthritis | High content and face validity | No reliability testing identified |

| Waiting time | EUMUSC.net, 2012 | Description: If a patient diagnosed with osteoarthritis has been referred to an orthopaedic surgeon, then the waiting time from first referral should not exceed 3 months | High content and face validity | No reliability testing identified |

| Process indicators | ||||

| Assessment | PCPI, 2006; MacLean, 2007; Pencharz, 2004 | Numerator: Number of patients from the denominator for whom a physical examination (visual inspection, palpation, range of motion) of the involved joint was performed during the initial visit | High content validity | Questionnaire-based test–retest aκ = 0.34, 63% exact agreement (21) |

| Denominator: Number of patients aged 18 years and older with a diagnosis of symptomatic osteoarthritis during the measurement period | ||||

| PCPI, 2006; MacLean, 2007; EUMUSC.net, 2012; Pencharz, 2004; NQF endorsed | Numerator: Number of patients from the denominator with a documentation of assessed pain annually and when new to a primary care provider | High content and face validity | No reliability testing identified | |

| Denominator: Number of patients aged 18 years and older with a diagnosis of symptomatic osteoarthritis during the measurement period | ||||

| PCPI, 2006; MacLean, 2007; EUMUSC.net, 2012; Pencharz, 2004; NQF endorsed | Numerator: Number of patients from the denominator with a documentation of assessed functional status annually and when new to a primary care provider | High content and face validity | Questionnaire-based test–retest κ = 0.53, 62% exact agreement (21) | |

| Denominator: Number of patients aged 18 years and older with a diagnosis of symptomatic osteoarthritis during the measurement period | ||||

| Education | EUMUSC.net, 2012; Pencharz, 2004 | Numerator: Number of patients from the denominator who have been given individually tailored education about the natural history, treatment and self- management of the disease at least once | High content and face validity | No reliability testing identified |

| Denominator: Number of patients aged 18 years and older with a diagnosis of osteoarthritis for >3 months during the measurement period | ||||

| Weight loss | Pencharz, 2004; MacLean, 2007 | Numerator: Number of patients from the denominator who have been advised annually to lose weight | High content validity | Questionnaire-based test–retest κ = 0.80, 90% exact agreement (21) |

| Denominator: Number of patients aged 18 years and older with a diagnosis of osteoarthritis who are overweight during the measurement period | ||||

| Pencharz, 2004; Darzi, 2008 | Numerator: Number of patients from the denominator who have been advised at least annually to lose weight and the benefit of weight loss on the symptoms of osteoarthritis have been explained | High content validity | No reliability testing identified | |

| Denominator: Number of patients aged 18 years and older with a diagnosis of symptomatic osteoarthritis who are overweight during the measurement period | ||||

| Pencharz, 2004; EUMUSC.net, 2012 | Numerator: Number of patients from the denominator who received referral to a weight loss programme | High content and face validity | Questionnaire-based test–retest κ = 0.80, 90% exact agreement (21) | |

| Denominator: Number of patients aged 18 years and older with a diagnosis of symptomatic osteoarthritis who are overweight for 3 years | ||||

| Therapeutic exercise | PCPI, 2006; EUMUSC.net, 2012; Pencharz, 2004; MacLean, 2007 | Numerator: Number of patients from the denominator who has no contraindication to exercise and are physically and mentally able to exercise was offered an individualized exercise programme or was referred to a relevant health professional | High content and face validity | Questionnaire-based test–retest κ = 0.34, 63% exact agreement (21) |

| Denominator: Number of patients aged 18 years and older with a diagnosis of symptomatic osteoarthritis for >3 months during the measurement period | ||||

| Assessment for use of anti-inflammatory medications | PCPI, 2006; NQF endorsed | Numerator: Number of patients from the denominator with a documentation of the assessment for use of anti-inflammatory or analgesic over-the-counter medications | High content and face validity | No reliability testing identified |

| Denominator: Number of patients aged 18 years and older with a diagnosis of osteoarthritis during the measurement period | ||||

| PCPI, 2006; MacLean, 2007; EUMUSC.net, 2012 | Numerator: Number of patients from the denominator taking a NSAID with a documented assessment for gastrointestinal and renal risk factors | High face validity | Questionnaire-based test–retest κ = 0.45, 64% exact agreement (21) | |

| Denominator: Number of patients aged 18 years and older with a diagnosis of osteoarthritis during the measurement period | ||||

| First-line pharmacological therapy | MacLean, 2007; Pencharz, 2004 | Numerator: Number of patients from the denominator who were prescribed acetaminophen first, unless there is a documented contraindication to use | High content validity | Questionnaire-based test–retest κ = 0.45, 68% exact agreement (21) |

| Denominator: Number of patients aged 18 years and older with a diagnosis of osteoarthritis who were started on pharmacological therapy, during the measurement period | ||||

| MacLean, 2007 | Numerator: Number of patients from the denominator who have been advised of the risk of liver toxicity | High content validity | No reliability testing identified | |

| Denominator: Number of patients aged 18 years and older with a diagnosis of osteoarthritis taking high-dose acetaminophen (>3 g/day), during the measurement period | ||||

| Pencharz, 2004 | Description: If oral pharmacologic therapy for osteoarthritis is changed from acetaminophen to a different oral agent, then there should be evidence that the patient has had a trial of maximum dose acetaminophen (suitable for age and comorbid conditions) | High content validity | No reliability testing identified | |

| Gastroprotection | PCPI, 2006; MacLean, 2007 | Numerator: Number of patients from the denominator taking a NSAID in combination with misoprostol or proton pump inhibitor | High content validity | Questionnaire-based test–retest κ = 0.45, 64% exact agreement (21) |

| Denominator: Number of patients aged 18 years and older with a diagnosis of osteoarthritis and a risk factor for gastrointestinal bleeding during the measurement period | ||||

| Assistive devices | MacLean, 2007; Pencharz, 2004; EUMUSC.net, 2012 | Numerator: Number of patients from the denominator for whom the need for ambulatory assistive devices has been assessed | High content and face validity | Questionnaire-based test–retest κ = 0.35, 68% exact agreement (21) |

| Denominator: Number of patients aged 18 years and older with a diagnosis of osteoarthritis who have reported difficulties of walking to accomplish activities of daily living during the measurement period | ||||

| Surgery | MacLean, 2007; Pencharz, 2004; EUMUSC.net, 2012; PCPI, 2006 | Numerator: Number of patients from the denominator who have been referred to an orthopaedic surgeon | High content and face validity | Questionnaire-based test–retest κ = 0.62, 76% exact agreement (21) |

| Denominator: Number of patients aged 18 years and older with a diagnosis of symptomatic osteoarthritis who failed to respond to pharmacological/non-pharmacological treatment during the measurement period | ||||

| Outcome indicators | ||||

| Functional improvement | EUMUSC.net, 2012 | Numerator: Number of patients from the denominator who have reported improvement of functional ability by 20% within 3 months after initiation/change of pharmacological/ non-pharmacological treatment | High content and face validity | No reliability testing identified |

| Denominator: Number of patients aged 18 years and older with a diagnosis of symptomatic osteoarthritis and functional limitation with initiation/change of pharmacological/non-pharmacological treatment during the measurement period | ||||

| Pain reduction | EUMUSC.net, 2012 | Numerator: Number of patients from the denominator who have reported reduction of pain level by 20% within 3 months after initiation/change of pharmacological/non-pharmacological treatment | High content and face validity | No reliability testing identified |

| Denominator: Number of patients aged 18 years and older with a diagnosis of symptomatic osteoarthritis initiation/change of pharmacological/non-pharmacological treatment during the measurement period | ||||

NSAID, Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

aκ = Cohen’s kappa coefficient.

Three studies (15,16,18) received low scores for the second AIRE domain due to lack of information regarding the relevant stakeholders’ involvement at some stage of the indicator development process. According to the Institute of Medicine (IOM), the appropriate high-level leadership, organization or expertise, not the one that develops the measures, has to review and endorse measures of quality intended for population health improvement (19). To that end, we identified which of the extracted quality indicators were endorsed by the NQF and which were not. NQF endorsement is the ‘gold standard’ for health care quality, and NQF-endorsed measures are deemed to be evidence based and valid (20).

The information regarding the piloting of indicators in practice and instructions for presenting and interpreting results were scarcely described in one of the selected studies (16). In the included studies, the quality indicators were appraised for multiple criteria, including importance of the indicators to be scientifically sound, valid and important. All included studies provided information on assessment of the identified indicators for scientific quality. Validity was judged by the members of the expert panel and discussed whether and/or to what extent the quality indicators were linked to the quality of care. MacLean et al. (15) used a RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method for critical appraisal of candidate indicators. The identified indicators in this study were assessed for validity and reliability (21). Pencharz et al. (16) used a RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method for critical appraisal of candidate indicators. The identified indicators in this study were assessed for validity, but no information is identified for reliability testing. PCPI (17) used a consensus technique to assess the candidate indicators for importance and validity, but no information is identified for reliability testing. EUMUSC.net project (18) used a Modified Delphi panel technique with the involvement of researchers and patients to assess the candidate indicators for validity, but no information is identified for reliability testing. Feasibility of data collection was assessed in two studies (16,18).

Quality indicators

Quality indicators were extracted only if they were relevant to the provision of primary care for osteoarthritis. For the purpose of this study, the target population was defined as patients aged 18 and older with a diagnosis of symptomatic osteoarthritis. The identified quality indicators were organized according to Donabedian’s ‘structure-process-outcome’ framework (8). Structure indicators refer to settings where osteoarthritis care is delivered, including adequate facilities, qualification of care providers or administrative structure. Process indicators examine how osteoarthritis care has been provided in terms of appropriateness, acceptability, completeness or competency. Outcome indicators refer to the end points of osteoarthritis care, such as improvement in function or recovery (8).

A total of 20 quality indicators were identified from the included studies, many of which overlap conceptually or in content: 2 structure, 16 process and 2 outcome indicators (Table 3). The structure and outcome indicators were derived from the EUMUSC.net (18) project. Structure indicators included two domains: access to care and waiting time, while outcome indicators were categorized into two domains: functional improvement and pain reduction.

Process indicators represent the way osteoarthritis care is delivered. They were derived from all four articles (15–18). The identified process indicators were categorized into nine domains: (i) assessment, (ii) education, (iii) weight loss, (iv) therapeutic exercise, (v) assessment for use of anti-inflammatory medications, (vi) first-line pharmacological treatment, (vii) gastroprotection, (viii) assistive devices and (ix) surgery.

Discussion

Despite the importance of osteoarthritis care, relatively few quality indicators are formally endorsed as legitimate measures of quality of osteoarthritis care. The current systematic review identified 20 quality indicators for evaluating primary care for adults with osteoarthritis. They assess multiple aspects of primary care for osteoarthritis, including clinical and organizational. All included studies used a rigorous method of developing quality indicators by combining a systematic literature search with appraisal of candidate indicators using expert panel opinion.

One of the important aspects when developing quality indicators is involvement of different stakeholders with different perspectives on quality of care. The studies included in the present systematic review mainly represent the views of multidisciplinary physicians’ panels, including primary care physicians and rheumatologists. None of the included studies represents patients’ or managers’ perspectives on quality of osteoarthritis care in developing quality indicators. However, in the process of developing quality indicators, it is recommended to include the perspectives of all potential end users including patients, their family caregivers, health professionals and managers (5,6).

Outcome indicators identified in this study related to the reduction in pain and functional improvement that serves as a marker of wellness of patients with osteoarthritis. Reasons for the small number of outcome indicators may be the limited scientific evidence linking structure and process to outcomes of osteoarthritis care, or perhaps the length of time it takes to assess outcomes due to the often long-term and fluctuating nature of osteoarthritis. There may be other outcomes of interest that are important to patients and families such as participation in social and recreational activities, community engagement etc. We did not identify any ‘negative’ or ‘do not do’ quality indicators for osteoarthritis care.

The included quality indicators target different populations, such as those with osteoarthritis of hip or knee or any osteoarthritis. However, this difference is not major to cause any difficulties in implementing the underlying quality indicators. Only one study provided quality indicators for evaluating osteoarthritis care among older adults (15), three others aimed to develop indicators for assessing osteoarthritis care among an adult population. Although consensus techniques have supported the candidate indicators, ongoing empirical testing of criterion validity (relative to patient outcomes) and reliability would be appropriate in varied patient populations according to age, sex and other characteristics.

The results of the review presented here provide a useful point of departure for other jurisdictions undertaking evaluation or research on primary care for osteoarthritis. Previous efforts in the osteoarthritis quality indicator field have been based primarily in the USA or Europe. When selecting indicators to be used locally, it is important to ensure that they reflect local circumstances and that they can be used to develop local standards of care (22). In this way, differences in policy priorities and the organization of health care systems can be addressed. Therefore, the identified indicators should be critically appraised by an expert panel to draw conclusions about their applicability to primary care for adults with osteoarthritis in Canada.

There are several studies presenting quality indicators that have been developed for measuring and improving cardiovascular disease care in Canada. For instance, the Canadian Cardiovascular Outcome Research Team (CCORT) in collaboration with the Canadian Cardiovascular Society (CCS) developed quality indicators for care for congestive heart failure specifically for use in the context of Canadian health care system (23). It is anticipated that osteoarthritis quality indicators that will be developed in the context of the Canadian health care system should be useful to clinicians, researchers and policy makers to detect both strengths and weaknesses of existing practice patterns and will have a beneficial impact on the quality of osteoarthritis care in Canada.

Strengths and limitations

This systematic review was conducted to identify evidence-based and valid quality indicators for care for adults with osteoarthritis. As demonstrated in this study, relatively little research has been done to develop indicators to assess the quality of primary care for adults with osteoarthritis. All included studies used a rigorous approach to developing quality indicators by combining a systematic literature search/developing indicators from clinical guidelines with appraisal of candidate indicators using expert panel opinion. However, our decision to include only indicators developed through an evidence-based approach may have led to the exclusion of some indicators that were developed using other approaches.

We assessed the methodological quality of the identified quality indicators using the AIRE instrument that is mainly focused on the indicator development process. Thus, we may underestimate the methodological quality of some studies because the information related to the indicator development process was not always described within the articles. We tried to track down additional information in the literature about the development process of quality indicators and were able to retrieve relevant additional information only for two sets of quality indicators.

Our literature search was restricted to studies published in English, which might have omitted relevant publications in other languages. Due to time constraints, we did not contact any organization/author to elicit any additional information. The study results indicate the need for further development of quality indicators with detailed methodological specifications for monitoring and accurate assessment of the care for adults with osteoarthritis.

Conclusions

Evidence-based and valid quality indicators for assessing quality of primary care for osteoarthritis are scarce, but the identified set of indicators addresses multiple dimensions of osteoarthritis care and provides an excellent starting point for further development. As the disease burden of osteoarthritis is high, and much of it is presented clinically to general practitioners, incorporation of these indicators to routine primary care practice is recommended. Periodic evaluation reports of primary care for osteoarthritis can be useful to monitor performance and serve to evaluate effectiveness of osteoarthritis care.

Quality indicators should be valid and sensitive to the changes they are intended to detect and should be linked to improving patient outcomes. There is a need to develop specific process, structure and outcome measures for adults with osteoarthritis by engaging clinicians, patients and families in the identification of meaningful measures and then determining how they could be collected systematically. Future research is required to implement the identified set of quality indicators in this study, to identify additional quality indicators of relevance to patients and families and to examine the association between identified structures and processes and osteoarthritis care outcomes.

Supplementary material

Supplementary data are available at Family Practice online.

Declaration

Funding: This study is supported by grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) (Funding Reference Number TTF-128263) and the Health System Performance Research Network (Fund #06034) which receives funding from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC). The views expressed in this paper are the views of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the funders.

Ethical approval: none.

Conflict of interest: none.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Zhang Y, Jordan JM. Epidemiology of osteoarthritis. Clin Geriatr Med 2010; 26: 355–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pefoyo AJ, Bronskill SE, Gruneir A et al. The increasing burden and complexity of multimorbidity. BMC Public Health 2015; 15: 415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Le TK, Montejano LB, Cao Z et al. Healthcare costs associated with osteoarthritis in US patients. Pain Pract 2012; 12: 633–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Peat G, McCarney R, Croft P. Knee pain and osteoarthritis in older adults: a review of community burden and current use of primary health care. Ann Rheum Dis 2001; 60: 91–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Campbell SM, Braspenning J, Hutchinson A et al. Research methods used in developing and applying quality indicators in primary care. BMJ 2003; 326: 816–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mainz J. Defining and classifying clinical indicators for quality improvement. Int J Qual Health Care 2003; 15: 523–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Canadian Council on Health Services Accreditation. A Guide to the Development and Use of Performance Indicators. Ottawa, Canada: Canadian Council on Health Services Accreditation, 1996. http://www.cchsa.ca (accessed on 6 October 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 8. Donabedian A. Evaluating the quality of medical care. Milbank Mem Fund Q 1966; 44 (suppl): 166–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fitch K, Bernstein SJ, Burnand B et al. The RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method User’s Manual. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Higgins JP, Deeks JJ(eds). Selecting studies and collecting data. In: Higgins J, Green S (eds). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions: Cochrane Book Series. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons Ltd, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 11. de Koning J, Smulders A, Klazinga NS.. The Appraisal of Indicators through Research and Evaluation (AIRE) Instrument. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Academic Medical Center, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Smeulers M, Verweij L, Maaskant JM et al. Quality indicators for safe medication preparation and administration: a systematic review. PLoS One 2015; 10: e0122695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Strudwick K, Nelson M, Martin-Khan M et al. Quality indicators for musculoskeletal injury management in the emergency department: a systematic review. Acad Emerg Med 2015; 22: 127–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Orwin RG.In: Cooper H, Hedges LV (eds). The Handbook of Research Synthesis. Russell Sage Foundation, New York, 1994, pp. 150–1. [Google Scholar]

- 15. MacLean CH, Pencharz JN, Saag KG. Quality indicators for the care of osteoarthritis in vulnerable elders. J Am Geriatr Soc 2007; 55 (suppl 2): S383–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pencharz JN, MacLean CH. Measuring quality in arthritis care: the Arthritis Foundation’s Quality Indicator set for osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2004; 51: 538–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons/Physician Consortium for Performance Improvement®. Osteoarthritis Physician Performance Measurement Set. American Medical Association, June 2006. http://www.ama-assn.org/apps/listserv/x-check/qmeasure.cgi?submit=PCPI (accessed on 15 November 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 18. EUMUSC.net. Musculoskeletal Conditions Health Care Quality Indicators. 2012. http://www.eumusc.net/workpackages_wp6.cfm (accessed on 22 November 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 19. Institute of Medicine. Toward Quality Measures for Population Health and the Leading Health Indicators. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2013, 134 p. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Patel MM, Brown JD, Croake S et al. The current state of behavioral health quality measures: where are the gaps?Psychiatr Serv 2015; 66: 865–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Østerås N, Garratt A, Grotle M et al. Patient-reported quality of care for osteoarthritis: development and testing of the osteoarthritis quality indicator questionnaire. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2013; 65: 1043–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Marshall MN, Shekelle PG, McGlynn EA et al. Can health care quality indicators be transferred between countries?Qual Saf Health Care 2003; 12: 8–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lee DS, Tran C, Flintoft V et al. CCORT/CCS quality indicators for congestive heart failure care. Can J Cardiol 2003; 19: 357–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.