Abstract

Zika virus (ZIKV) shares a high degree of homology with dengue virus (DENV), suggesting that pre-existing immunity to DENV could impact immune responses to ZIKV. Here, we have tracked the evolution of ZIKV-induced B cell responses in three DENV-experienced donors. The acute antibody (plasmablast) responses were characterized by relatively high somatic hypermutation and a bias toward DENV binding and neutralization, implying the early activation of DENV clones. A DENV-naive donor in contrast showed a classical primary plasmablast response. Five months post-infection, the DENV-experienced donors developed potent type-specific ZIKV neutralizing antibody responses in addition to DENV cross-reactive responses. Since cross-reactive responses were poorly neutralizing and associated with enhanced ZIKV infection in vitro, pre-existing DENV immunity could negatively impact protective antibody responses to ZIKV. The observed effects are epitope dependent suggesting a ZIKV vaccine should be carefully designed for DENV-seropositive populations.

Introduction

ZIKV is a mosquito-borne flavivirus that has been linked to microcephaly and severe neurological complications, such as Guillain-Barré syndrome (1, 2). The virus is closely related to the four serotypes of DENV (DENV1, 2, 3, and -4), as well as other circulating flaviviruses including West Nile virus (WNV), resulting in significant immunological cross-reactivity (3–7). While neutralizing antibodies (nAbs) play an important role in protection against flavivirus infection, they can also contribute to severe disease through a phenomenon termed antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE) (8–10). In the case of DENV, sub-neutralizing concentrations of pre-existing heterotypic nAbs have been implicated in promoting viral replication by facilitating the interaction of the virus with Fc receptor-bearing target cells (8). Importantly, enhancement of ZIKV infection by cross-reactive DENV-specific antibodies and vice versa has been demonstrated in vitro, and ADE of ZIKV pathogenesis by pre-existing anti-flavivirus immunity has been observed in mouse models (5–7, 11–14). Given that ZIKV is currently circulating in regions that are highly endemic for DENV, an understanding of how prior DENV exposure impacts the B cell response to ZIKV will be critical for the design of vaccines and therapies intended for DENV-immune populations.

Previous studies have shown that non-structural protein 1 (NS1), envelope (E), and precursor membrane (prM) proteins are dominant targets for the human B cell response to flaviviruses. NS1 is secreted by infected cells and functions in pathogenesis and immune evasion (15), the surface E protein mediates viral entry and is the primary target for nAbs (7, 16, 17), and PrM is a 166-amino acid protein that is associated with E on immature and partially mature viruses (18). The E protein consists of three domains: domain I (DI), which participates in conformational changes required for viral entry; domain II (DII), which contains the conserved fusion loop (FL); and domain III (DIII), which is the putative receptor binding domain (19). Previous studies have established that monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) targeting epitopes within DIII are typically type-specific and potently neutralizing, whereas mAbs targeting the conserved FL are cross-reactive and poorly neutralizing (7, 16, 17, 20).

In this study, we have longitudinally tracked the ZIKV-specific B cell response in three DENV-experienced donors using single B cell cloning and large-scale antibody isolation. The acute phase (plasmablast) response was dominated by somatically mutated clones that showed preferential binding and neutralization of DENV, providing evidence for original antigenic sin (OAS) during the early B cell response to ZIKV in DENV-experienced donors. Interestingly, however, at 5 months post infection, the memory B cell responses were comprised of both OAS-phenotype antibodies that were broadly cross-reactive and poorly neutralizing as well as de novo generated antibodies that were ZIKV-specific and potently neutralizing. Collectively, the results have implications for the development of ZIKV vaccines intended for DENV-immune populations and provide insight into the role that pre-existing B cell memory plays in modulating the antibody specificities induced by antigenically variable viruses.

Results

Potent plasmablast induction in ZIKV-infected, DENV-experienced donors

To study the early ZIKV-induced B cell response in DENV-experienced individuals, three ZIKV-infected donors (donors 2, 3, and 4) living in a highly DENV endemic region of Colombia were sampled during acute infection (within 8 days after symptom onset) (table S1) (21). A single donor (donor 1) from the United States who was infected with ZIKV while overseas was also sampled for comparison (table S1). As expected, the acute sera from donors 2, 3, and 4 showed strong IgG binding reactivity to whole DENV1-4 particles and recombinant DENV NS1 proteins (fig. S1). In contrast, the acute serum from donor 1 showed little to no such binding (fig. S1). Although the acute serum reactivity to DENV particles and NS1 proteins could, in principle, be due to cross-reactive ZIKV-induced antibodies, previous studies have shown that NS1-specific IgG antibodies are not present in the serum during the first week after the onset of symptoms of ZIKV infection (22, 23), implying that the acute serum reactivity to DENV NS1 observed for donors 2, 3, and 4 is largely mediated pre-existing antibodies that were induced by prior DENV exposure. Furthermore, the acute serum from these three donors showed similar or more potent neutralizing activity against DENV compared to ZIKV, whereas the acute serum from donor 1 showed little to no neutralizing activity against DENV1-4 and relatively weak neutralization of ZIKV. These serological and epidemiological data provide convincing evidence that donor 2, 3, and 4 were previously exposed to DENV, whereas donor 1 was DENV-naïve at the time of infection.

The appearance of antigen-specific plasmablasts in peripheral blood during acute viral infection is typically the first indication of a B cell response (24–26). Therefore, we first measured the plasmablast frequency in peripheral blood approximately one week after symptom onset (table S1). In all three DENV-experienced donors, a massive plasmablast population (CD3−CD20−/loCD19+CD27hiCD38hi) that accounted for 39–63% of peripheral B cells was observed (Fig. 1A, fig. S2). In contrast, the plasmablast population in the ZIKV infected, DENV-naïve donor was relatively small, accounting for only 2.5% of peripheral B cells (Fig. 1A). To deconstruct the acute ZIKV-induced B cell response, we single-cell sorted between 100 and 300 plasmablasts from each donor sample and rescued the antibody variable heavy (VH)- and light (VL)-chain sequences by single-cell PCR. Between 42 and 119 cognate VH and VL pairs from each donor were cloned and expressed as full-length IgGs. Sequence analysis revealed that the plasmablasts sorted from the three DENV-experienced donors were somatically mutated— with per-donor averages ranging between 15 and 20 nucleotide substitutions in VH—and clonally expanded (Fig. 1B, C). This level of somatic hypermutation (SHM) is comparable to that observed in typical IgG+ memory B cells as well as in plasmablasts induced by influenza vaccination (25), supporting a memory B cell origin for these acutely induced cells. In contrast, the majority of plasmablasts isolated from the DENV-naïve donor sample showed little to no SHM and somewhat more limited clonal expansion (Fig. 1B, C), supporting their emergence via activation of naïve B cells. We conclude that ZIKV infection induces a rapid and robust plasmablast response in DENV-experienced donors, and that the large majority of these acutely induced cells appear to originate from the memory B cell compartment.

Figure 1. Analysis of plasmablast responses in one naïve and three DENV-experienced donors.

A) Flow cytometric analysis of plasmablast responses in one naïve and three DENV-experienced donors during ongoing ZIKV infection. Plasmablasts are defined herein as CD19+ CD3− CD20−/lo CD38hi CD27hi cells. Plots shown are gated for CD3− CD20−/lo cells with the CD27hi CD38hi plasmablasts marked by a box. The frequency of plasmablasts within the CD3− CD20−/lo population is shown next to the gate. The numbers in parentheses show the percentage of peripheral B cells that are plasmablasts. Flow cytometry data was analyzed using FlowJo software (v10.0.8). B) Load of somatic mutations (expressed as number of nucleotide substitutions) in VH and VL in plasmablast-derived mAbs isolated from a DENV-naïve (donor 1) and three DENV-experienced donors (donors 2–4). All VH- and VL-chains are shown, regardless of whether the paired antibody chain was recovered. C) Clonal lineage analysis. Heavy chain sequences were assigned to lineages using Clonify (52). Each lineage is represented as a segment proportional to the lineage size. The total number of recovered heavy chains is shown in the center of each pie. All lineages that contain only a single sequence are combined and shown as a single grey segment.

A large proportion of plasmablast-derived mAbs isolated from ZIKV-infected, DENV-experienced donors bind the ZIKV E protein

ELISA binding studies showed that between 50–75% of the mAbs isolated from the DENV-experienced donors bound to whole ZIKV (fig. S3), which is similar to the percentage of antigen-specific mAbs recovered from plasmablasts induced by influenza vaccination and DENV infection (25, 27). In contrast, only 13% of the plasmablast-derived mAbs isolated from the DENV-naïve donor bound with detectable affinity to whole ZIKV particles. To further map the antigenic specificities of the 303 plasmablast-derived mAbs, we performed biolayer interferometry (BLI) binding experiments with recombinant ZIKV NS1 and E proteins. The percentage of mAbs isolated from the three DENV-experienced donors that showed reactivity with ZIKV NS1 was low at 8–12% and higher for recombinant E at 15–39% (Fig. 2A, table S2). In contrast, 17% of the mAbs isolated from the DENV-naïve donor bound to recombinant NS1, whereas only a single mAb bound with detectable affinity to recombinant E (Fig. 2A, table S2). The remaining ZIKV-specific mAbs, which accounted for 13–32% of the corresponding donor responses, bound to epitopes expressed on whole virus but not on recombinant E. Seventy percent of the plasmablast mAbs isolated from donor 1 and about 20–50% of the plasmablast mAbs isolated from donors 2, 3, and 4 could not be associated with any ZIKV reactivity (Fig. 2A). Since anti-prM antibodies have been shown to dominate the antibody response during secondary DENV infection (28), we next investigated the specificities of the whole virus-specific mAbs isolated from the DENV-experienced donors by Western blot. In fact none of the mAbs recognized prM, 30% showed reactivity with E protein from viral lysates, and the remaining mAbs failed to bind to ZIKV in this assay (fig. S4). Hence, the majority of these mAbs likely bind to E-specific epitopes expressed only on intact virions. Notably, similar specificities have been previously described for both DENV and ZIKV (4, 7, 27, 29).

Figure 2. Binding characteristics of mAbs isolated from plasmablasts during acute ZIKV infection.

A) Specificities of the mAbs isolated from one DENV naïve donor and three DENV-experienced donors. Distribution of mAbs that bind to NS1, recombinant E, epitopes expressed only on whole ZIKV and those for which no specificity could be assigned are shown. The number at the top of each bar represents the total number of mAbs cloned from each donor. B) Epitope mapping of recombinant E-specific antibodies isolated from three DENV-experienced donors. Pie charts show the distribution of antibodies that bind to epitopes within DIII, within or proximal to the fusion loop on DII, and defined by mAbs ADI-24314 and ADI-24247. 4G2-like FL: competition with 4G2, WNV E reactive, and E-FL sensitive; non-WNV FL: 4G2 competitive, E-FL sensitive, and WNV E non-reactive; FL proximal: 4G2 competitive, E-FL reactive, and WNV E non-reactive; DIII: recombinant DIII reactive; ADI-24314 competitor: 4G2 non-competitive, ADI-24314 competitive, E-FL reactive; ADI-24247 competitor: 4G2 non-competitive, ADI-24247 competitive, E-FL reactive. NC, not characterized due to low binding affinity. C) Heat map of mAb binding reactivity to ZIKV and DENV1-4 E proteins or whole viral particles (left) and ZIKV and DENV1-4 NS1 proteins (right). The E-specific mAbs shown were isolated from DENV-experienced donors. Apparent binding affinities for recombinant E and NS1 proteins were determined by BLI measurements, and apparent binding affinities for whole virus were determined by ELISA.

To further define the epitopes targeted by the recombinant E-reactive mAbs isolated from the DENV-experienced donors, we (1) compared the apparent binding affinities of the mAbs for recombinant DIII, WNV E, and a previously described ZIKV E protein (E-FL) that contains substitutions within and proximal to the fusion loop that abolish binding by most fusion loop-specific antibodies (30) (fig. S5) and (2) performed competitive binding experiments using two previously characterized mAbs, 4G2 and ZV-67, that bind to the fusion loop on DII and the lateral ridge on DIII, respectively (table S2) (30, 31). Since the fusion loop-specific mAb 4G2 reacts with WNV E and fails to react with E-FL (table S3), we classified mAbs that competed with 4G2, bound to WNV E, and failed to bind to E-FL as “4G2-like FL binders”. 4G2 competitor mAbs that failed to bind to E-FL but did not cross-react with WNV E were classified as “non-WNV FL binders” and 4G2-competitor mAbs that did not cross-react with WNV E but did bind to E-FL were classified as “FL proximal binders”. Altogether, mAbs that bound within or proximal to the fusion loop comprised up to 50% of the recombinant E-reactive responses (Fig. 2B, table S2). Interestingly, DIII-specific mAbs were absent from the donor 3 and donor 4 responses but comprised approximately 30% of the donor 2 response (Fig. 2B, table S2). Six out of the eight DIII-reactive mAbs competed with ZV-67, suggesting that they likely recognize epitopes within or proximal to the lateral ridge on DIII (table S2). This class of antibodies showed preferential VH3-23 germline gene usage and contained convergent sequence signatures in both CDRH3 and CDRL3 (table S4), suggesting that these mAbs may share a common mode of antigen recognition. Notably, a recent study described the isolation of mAbs from several different donors that share these binding and sequence characteristics (32), further supporting convergent antibody recognition of this epitope. To estimate the number of different antigenic sites recognized by the remaining E-specific mAbs, we performed competitive binding experiments with two broadly cross-reactive mAbs from the panel (ADI-24247 and ADI-24314) that did not compete with 4G2, ZV-67, or each other (table S2 and table S5). Between 12 and 35% of the E-specific donor responses bound to epitopes overlapping that of ADI-24247 or ADI-24314 (Fig. 2B). Overall, we conclude that substantial fractions of the acute ZIKV-induced B cell response in DENV-experienced donors are directed against quaternary epitopes expressed only on whole virus, and those that are reactive with recombinant E are largely directed to the fusion loop and other highly conserved epitopes.

The ZIKV-induced plasmablast response in DENV-experienced donors is dominated by DENV cross-reactive clones

The E proteins of ZIKV and DENV share over 50% sequence identity, resulting in significant immunological cross-reactivity (3, 6, 7). To determine the degree to which mAbs generated from plasmablasts during acute ZIKV infection cross-reacted with DENV, we measured the apparent binding affinities of the mAbs for recombinant DENV1-4 E and NS1 proteins. The majority of E-specific mAbs from the three DENV-experienced donors bound with higher affinity to at least one of the four DENV E proteins than to ZIKV E, consistent with a recall response dominated by reactivated DENV-induced memory B cells (Fig. 2C, table S2, and fig. S6). Selected mAbs isolated from donors 2, 3, and 4 that targeted epitopes expressed only on whole ZIKV showed similar DENV-biased binding profiles (fig. S7). In contrast, the whole virus-specific mAbs isolated from donor 1 bound exclusively to ZIKV (Fig. S7).

Strikingly, approximately 50% of the ZIKV E-reactive mAbs isolated from the DENV-experienced donors cross-reacted with all four DENV serotypes (Fig. 2C, table S2). Most of these broadly cross-reactive mAbs targeted epitopes within or proximal to the fusion loop or unknown epitopes defined by ADI-24247 and ADI-24314 (Fig. 2C, table S2). In contrast, the DIII-specific mAbs only showed cross-reactivity with DENV-1 E (Fig. 2C, table S2). Interestingly, 100% of the NS1-specific mAbs isolated from donors 2 and 3 showed cross-reactivity with DENV-1 and -3 NS1, whereas the NS1-specific mAbs from donor 4 were exclusively ZIKV-specific (Fig. 2C, table S6). Sequence analysis revealed that the ZIKV NS1-specific mAbs from donor 4 lacked SHM, supporting a naïve B cell origin (fig. S8). The reasons for this are unclear, but may be due to the lack of pre-existing cross-reactive NS1-specific memory B cells in this donor. As expected, all of the NS1-specific mAbs isolated from donor 1 were ZIKV-specific and lacked SHM (Fig. 2C). Notably, the affinities of these mAbs were comparable to the affinities of the NS1-specific mAbs isolated from the DENV-experienced donors (Fig. 2C, table S6), which is perhaps because the plasmablast-derived antibodies from the DENV-experienced donors had not undergone affinity maturation toward ZIKV. Taken together, the sequencing and binding results provide evidence for OAS during the acute-phase B cell response to ZIKV in DENV-experienced donors.

The majority of plasmablast-derived mAbs isolated from DENV-experienced donors are poorly neutralizing and potently enhancing

To assess the functional properties of the plasmablast-derived mAbs isolated from the DENV-experienced donors, we next performed neutralization and antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE) assays. Due to the large number of mAbs, initial neutralization screening was performed using a single concentration of purified IgG. At a concentration of 1 μg/ml, approximately 20% of mAbs from each donor reduced ZIKV-Paraiba (Para) infectivity by ≥50% and all of these nAbs cross-neutralized at least one of the four DENV serotypes (Fig. 3A). Additionally, the majority of nAbs (53/63 or 84%) showed more potent neutralizing activity against one of the four DENV serotypes than ZIKV-Para (Fig. 3A). We next performed neutralization titration experiments on a subset of mAbs to evaluate neutralization potency. Consistent with the binding and single point neutralization results, a large proportion of mAbs showed preferential neutralization of DENV, further supporting a DENV-induced memory B cell origin for these recently activated cells (Fig. 3B, table S7, fig. S9). Of significance, the majority of plasmablast-derived mAbs showed poorly neutralizing activity against ZIKV-Para (Fig. 3B, C). The notable exceptions were the four DIII-specific mAbs, which showed highly potent neutralizing activity against both ZIKV-Para and DENV-1 (Fig. 3B, C and table S7). These nAbs displayed IC50s between 0.9 and 2.7 ng/ml against ZIKV-Para and between 0.2 and 27 ng/ml against DENV-1 (Fig. 3B, C and table S7). Interestingly, most of the mAbs that bound to quaternary epitopes on the E protein showed little to no neutralizing activity against ZIKV. Previous studies have described two classes of quaternary mAbs (EDE1 and EDE2), which are defined based on differing sensitivity to removal of the N-glycan at Asp153 (4). Given that mAbs directed against EDE2 have been shown to be substantially less potent against ZIKV than mAbs targeting EDE1, it is likely that the quaternary mAbs described here recognize the EDE2 epitope.

Figure 3. Neutralizing activity of mAbs isolated from plasmablasts during acute ZIKV infection in DENV-experienced donors.

A) Heat map showing mAb neutralization of ZIKV-Para, DENV-1, DENV-2, DENV-3, and DENV-4 at a concentration of 1.0 μg/ml. B) Heat map showing neutralization IC50s for selected mAbs against ZIKV-Para, DENV-1, DENV-2, DENV-3, and DENV-4. Epitope assignments are indicated on the left. C) Neutralization IC50s for selected mAbs against ZIKV-Para. IC50 values represent the concentration of IgG required to reduce viral infectivity by 50%. Neutralization assays were performed using a live virus plaque reduction assay. N.N., non-neutralizing.

We next tested the abilities of selected mAbs to enhance ZIKV infection using non-permissive K562 cells. Consistent with prior studies, all of the mAbs enhanced ZIKV infection, but peak enhancement was observed at lower concentrations for the potently neutralizing DIII-specific mAbs compared to the poorly neutralizing cross-reactive mAbs (fig. S10) (6, 7, 16, 33). Additionally, there was a linear correlation between neutralization potency and the sum of the enhancement activity over the range of mAb concentrations tested, as defined by the area under the curve (AUC) (fig. S10). Altogether, the results show that the acute B cell response to ZIKV in DENV-immune donors is dominated by cross-reactive antibodies that show poorly neutralizing activity and a propensity to enhance ZIKV infection in vitro.

Isolation of E-specific mAbs from longitudinal samples obtained from the DENV-experienced donors

To track the evolution of the B cell response to ZIKV in DENV-experienced donors, we collected blood samples from donors 2, 3, and 4 approximately five months post-infection (table S1). To assess the magnitude of the E-specific memory B cell response at this time point, peripheral B cells were stained with a fluorescently labeled ZIKV E protein and analyzed by flow cytometry (Fig. 4A and fig. S11). Interestingly, robust E-specific memory B cell responses were observed in donors 3 and 4, whereas E-specific memory B cells were undetectable in donor 2 (Fig. 4A). The reasons for this are unclear, but given that donor 2 showed the highest frequency of plasmablasts during acute infection, one explanation is that the virus was rapidly cleared by the plasmablast-derived antibodies which prevented the formation of a germinal center (GC) response. Four hundred ZIKV E-specific memory B cells were single-cell sorted from donors 3 and 4, and approximately 200 VH and VL pairs were cloned and expressed as full-length IgGs for further characterization. To assess the extent of affinity maturation that occurred over this time period, the apparent binding affinities of the E-specific memory B cell-derived mAbs were measured and compared to the affinities of the E-specific plasmablast-derived mAbs. As expected, the average apparent affinity for ZIKV E was significantly higher in the memory B cell subset, suggesting that the ZIKV-induced B cells underwent affinity maturation over time (Fig. 4B). Notably, clonal expansions were observed in both donor response repertoires (Fig. 4C), but there were few to no clonal lineages shared between the plasmablast and memory B cell-derived subsets (table S9, fig. S12). Although the sampling size is too small to determine the degree of overlap between the two B cell populations, these results suggest that the most dominant clonal lineages likely differ between the two compartments.

Figure 4. Longitudinal analysis of ZIKV E-specific memory B cell responses in the DENV-experienced donors.

A) ZIKV E-specific memory B cell sorting. FACS plots show ZIKV E reactivity of IgG+ B cells from the three convalescent DENV-experienced donors and a ZIKV seronegative healthy donor control. B cells in quadrant 2 (Q2) were single cell sorted for mAb cloning. ZIKV E was labeled with two different colors to reduce background binding. B) Apparent binding affinities of plasmablast and memory B cell-derived mAbs to recombinant ZIKV E. Red bars indicate the median IC50s. C) Clonal lineage analysis of memory B cell-derived mAbs. Heavy chain sequences were assigned to lineages using Clonify (52). Each lineage is represented as a segment proportional to the lineage size. The total number of recovered heavy chains is shown in the center of each pie. All lineages that contain only a single sequence are combined and shown as a single grey segment. D) Heat map showing apparent binding affinities of the memory B cell-derived mAbs to recombinant ZIKV E and DENV1-4 E proteins. Top panel, mAbs cloned from donor 3; bottom panel, mAbs cloned from donor 4. E) Load of somatic mutations (expressed as number of nucleotide substitutions in the variable region of the heavy chain) in mAbs isolated from plasmablasts and memory B cells in DENV-experienced donors. Each point represents an individual mAb. Red bars indicate the median number of nucleotide substitutions. F) Binding of plasmablast and memory B cell-derived mAbs to recombinant ZIKV E. Apparent binding affinities are shown in the plot. Red bars indicate median apparent IC50s. Statistical comparisons were made using the Mann-Whitney test (*** P < 0.001, ** P < 0.01, n.s. = not significant). 023, ADI-30023 competitor; 056, ADI-30056 competitor; 314, ADI-24314 competitor; 247, ADI-24247 competitor; FL, 4G2 competitor; DIII, recombinant DIII binder; UK, unknown.

ZIKV infection induces de novo and cross-reactive memory B cell responses in DENV-experienced donors

We next assessed the degree of cross-reactivity with the E proteins from DENV1-4. Unexpectedly, 60% and 30% of memory B cell-derived mAbs from donors 3 and 4, respectively, bound exclusively to ZIKV E, suggesting that these antibodies either arose from pre-existing memory B cells that uniformly lost DENV reactivity during the process of affinity maturation or that they originated from activated naïve B cells that had entered GCs and undergone affinity maturation (Fig. 4D, table S8). In support of the latter hypothesis, sequence analysis revealed no overall increase in SHM in the ZIKV-specific memory B cell-derived mAbs compared to the plasmablast-derived mAbs (Fig. 4E). Epitope mapping experiments showed that about 10–20% of the ZIKV-specific memory B cell-derived mAbs bound to epitopes within DIII, 0–15% bound to epitopes within or proximal to the fusion loop, and 0–2% bound to epitopes overlapping that of ADI-24314 (fig. S13, table S8). To estimate the number of different antigenic sites recognized by the remaining ZIKV-specific mAbs, we performed competitive binding assays with two mAbs from the panel (ADI-30056 and ADI-30023) that did not compete with ZV-67, 4G2, ADI-24314, ADI-24247, or each other (table S8). Based on these results, we found that 50–60% of the ZIKV-specific mAbs targeted unknown sites defined by ADI-30056 or ADI-30023 and 10–30% of mAbs did not compete with any of the control mAbs (fig. S13, table S8).

Interestingly, the majority (84%) of DENV cross-reactive mAbs showed reactivity with all four DENV serotypes (Fig. 4D, table S8). Most of these broadly cross-reactive mAbs showed DENV-biased binding profiles and overall higher levels of SHM compared to the ZIKV-specific mAbs, suggesting that they likely arose from pre-existing DENV-induced memory B cells that formed secondary GCs (Fig. 4D and E, table S8). The latter result also provides additional evidence that the ZIKV-specific mAbs originated from naïve B cells that underwent affinity maturation rather than from pre-existing memory B cells that lost DENV cross-reactivity. In addition, the average apparent affinity of the cross-reactive mAbs was significantly higher than that of the plasmablast-derived mAbs and the ZIKV-specific memory B cell-derived mAbs, providing further evidence for GC re-entry by memory B cells (Fig. 4F). Notably, this result is consistent with recent studies in mice demonstrating that memory B cells can re-diversify their BCRs within secondary GCs (34–36). As anticipated based on their broad cross-reactivity, most of these mAbs targeted epitopes within or proximal to the fusion loop on DII (Fig. 4D, table S8).

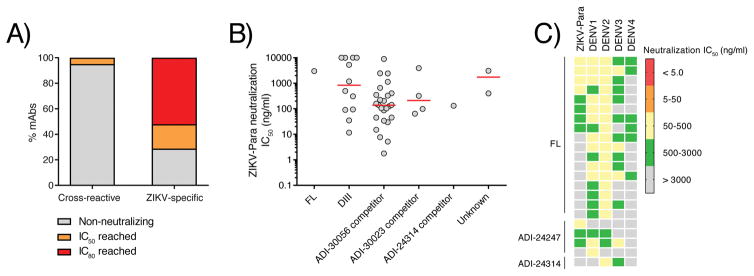

We next tested the memory B cell-derived mAbs for neutralizing activity. Only a small minority of the cross-reactive mAbs (4/80 or 5%) showed neutralizing activity against ZIKV-Para at a concentration of 1 μg/ml, whereas the overwhelming majority (52/73 or 71%) of the ZIKV-specific mAbs showed such neutralizing activity (Fig. 5A, table S8). Neutralization titration experiments revealed that most potent ZIKV-specific mAbs displayed IC50s between 1.0 and 10 ng/ml and targeted epitopes overlapping that of ADI-30056 (Fig. 5B, table S10). Notably, approximately 90% of the cross-reactive mAbs tested showed more potent neutralizing activity against at least one of the four DENV serotypes than ZIKV-Para, further suggesting that these mAbs originated from pre-existing memory B cells that re-entered GCs (Fig. 5C, table S10). We conclude that the ZIKV-induced memory B cell response is comprised of both OAS phenotype antibodies that display broad cross-reactivity and poorly neutralizing activity, as well as de novo generated ZIKV-specific antibodies that show potent but type-specific neutralizing activity.

Figure 5. Neutralizing activity of memory B cell-derived mAbs.

A) Percentage of cross-reactive and ZIKV-specific mAbs that reached neutralization IC50 or IC80 at a concentration of 1.0 μg/ml. B) Neutralization IC50 values of selected mAbs from each competition group. IC50 values represent the concentration of IgG required to reduce viral infectivity by 50%. Red bars indicate median IC50s. C) Heat map showing neutralization IC50s for selected cross-reactive mAbs against ZIKV-Para, DENV-1, DENV-2, DENV-3, and DENV-4. Neutralization assays were performed using a live virus plaque reduction assay.

Discussion

Here, we have used single B cell cloning and large-scale antibody characterization to track the evolution of ZIKV-induced B cell responses in three DENV-experienced donors. In all three donors, massive plasmablast populations were observed during acute ZIKV infection, which were similar in magnitude to the plasmablast responses previously observed in individuals experiencing secondary DENV infection (24). Interestingly, the plasmablast population in a ZIKV-infected, DENV-naïve donor was relatively small, which could be due to multiple factors, such as differences in age, viral load, or immune history. However, the immune history explanation is consistent with previous studies that have shown that peripheral blood plasmablast responses during primary infection are delayed and substantially lower in magnitude than during secondary infection (37, 38). Notably, the plasmablast responses in the three DENV-experienced donors were clonally expanded and showed relatively high levels of SHM—consistent with a recall response dominated by reactivated memory B cells—whereas the plasmablasts from the ZIKV-infected, DENV-naïve donor showed substantially lower levels of SHM and somewhat more limited clonal expansion, suggesting emergence via activation of naïve B cells. Interestingly, over half of the plasmablast-derived mAbs isolated from the DENV-experienced donors showed reactivity with whole ZIKV particles or recombinant ZIKV NS1, whereas a substantially smaller fraction of the plasmablast-derived mAbs from the DENV-naïve donor showed such binding. This result could either be due to the low binding affinity of mAbs isolated from activated naïve B cells or that the plasmablast response in this donor was largely directed against viral antigens that were not tested in this study.

Binding and functional characterization of the plasmablast-derived mAbs from donors 2, 3, and 4 revealed that the acute B cell response to ZIKV is dominated by reactivated DENV clones, thus providing evidence of OAS during the acute-phase B cell response to ZIKV in DENV-experienced donors. Most of these antibodies, although broadly cross-reactive, displayed poorly neutralizing activity and enhanced ZIKV infection in vitro, suggesting that pre-existing immunity to DENV virus may negatively impact early protective B cell responses to ZIKV. Notably, none of the mAbs isolated from the ZIKV-infected DENV-naïve donor showed cross-reactivity with any of the four serotypes of DENV, suggesting that highly conserved epitopes are not immunodominant in the context of primary ZIKV infection. Although ADE has been proposed to be primarily driven by pre-existing serum antibody, plasmablasts secrete substantial amounts of antibody during acute infection. It is therefore possible that boosting of poorly neutralizing responses during the early stages of infection could contribute to ADE. However, it is important to emphasize that while animal studies have suggested a role for ADE in vivo (14), the relevance of ADE in determining the severity and/or higher risk for ZIKV infection remains yet to be elucidated in humans.

Although the majority of plasmablast-derived mAbs isolated from the three DENV-experienced donors were poorly neutralizing, a subset of mAbs from donor 2 showed highly potent neutralizing activity against both ZIKV and DENV-1. These mAbs bound to epitopes within the lateral ridge of DIII and showed convergent sequence signatures in both the heavy and light chains. Notably, similar antibodies were recently isolated from several DENV-immune donors that were selected based on high ZIKV neutralizing titers (32). The identification of recurrent potent nAbs in multiple different donors suggests that this antigenic region may be a particularly attractive target for vaccines intended for DENV-immune populations. Interestingly, despite the identification of potent nAbs from the donor 2 plasmablast population, the acute serum from this donor showed weaker neutralizing activity than the acute sera from donor 3 and 4. One possible explanation for this result is that the donor 3 and 4 sera contain overall higher titers of anti-ZIKV antibodies compared to the donor 2 serum. In support of this hypothesis, the donor 2 acute serum showed substantially weaker binding to whole DENV and ZIKV particles compared to the acute serum from donors 3 and 4.

The phenomenon of OAS has been documented in the context of repeated influenza virus exposure as well as during secondary DENV infections (17, 39–43), and these studies have suggested that memory responses to the primary infecting strain may prevent the induction of effective de novo responses. Interestingly, our results show that the ZIKV-induced memory B cell response in DENV-experienced donors is comprised of both poorly neutralizing OAS-phenotype antibodies—which appear to have originated from pre-existing DENV-induced memory B cells that re-entered GCs—as well as potently neutralizing ZIKV-specific antibodies that likely originated from naïve B cells that entered primary GCs. Hence, our results suggest that effective de novo memory B cell responses to ZIKV can be induced in the presence of pre-existing cross-reactive DENV clones. However, only about 50% of the mAbs isolated from E-specific memory B cells were ZIKV-specific; the remaining mAbs were broadly cross-reactive, poorly neutralizing, and potently enhancing. The relative contribution of these two different classes of antibodies to protection, virulence, and immunopathology of ZIKV infection remains to be elucidated.

One limitation of our study is the small number of donors studied. As a result, intra-donor comparisons can be made with high certainty, but inter-donor comparisons are less robust. However, we found evidence of OAS in all three DENV-experienced donors, suggesting that this phenomenon likely occurs in the majority of ZIKV-infected donors that have been previously exposed to DENV. Another limitation of our study was the use of recombinant ZIKV E for memory B cell sorting, which prevented the isolation of memory B cell-derived mAbs that recognize quaternary epitopes. Finally, since we were not able to obtain detailed medical histories for these donors, it was not possible to determine the number and frequency of prior DENV infections and the number of DENV serotypes to which they had been exposed. However, the serological data strongly suggest that donors 2, 3, and 4 had experienced at least one DENV infection prior to ZIKV infection, which we believe is sufficient for the interpretation of the results of this study.

Importantly, although our study was performed using naturally infected donors, vaccines expressing full-length ZIKV E—which include multiple recently described plasmid DNA, purified inactivated, protein subunit, adenovirus vector, and mRNA vaccines (44–49)—would be expected to induce similar responses in DENV-experienced individuals. Such vaccines, which will need to be deployed in areas that are highly endemic for DENV, will likely induce a substantial OAS response in these individuals. Given this possibility, the clinical development of ZIKV vaccines should also consider the recruitment and immunization of DENV-immune donors. Notably, ongoing Phase I studies on ZIKV vaccine candidates are currently being performed on individuals living in areas that are not endemic for DENV, and therefore the majority of these individuals are likely DENV-naïve. Altogether, the results of this study provide rationale for the design of vaccines specifically focused on the DIII lateral ridge or other ZIKV-specific neutralizing epitopes for use in DENV-immune populations.

Materials and Methods

Study design

We initiated this study to gain and in-depth understanding of the antibody response to ZIKV in DENV-experienced donors. To study these responses, we obtained peripheral blood mononuclear cells from three ZIKV-infected donors that had serological evidence or prior DENV exposure and one ZIKV-infected naïve donor for comparison. Four donors were included in this study because this was the largest number of donors for which large numbers of antibodies could be practically cloned and characterized. At least two independent experiments were performed for affinity measurements, neutralization assays, enhancement assays, and antibody competition assays, and the results shown are derived from single representative experiments. All samples for this study were collected with informed consent of volunteers. This study was unblinded and not randomized.

PBMC and plasma isolation

Blood and serum samples were obtained through Antibody Systems Inc. (Hurst, TX) under The Scripps Research Institute IRB-15-6683. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were isolated as previously described (50). Briefly, whole blood was diluted 1:2 with PBS and underwent ultracentrifugation over layered Lymphoprep (Stemcell Technologies, Cambridge, MA). PBMC monolayer was collected, resuspended, and stored in liquid nitrogen.

Generation of ZIKV and DENV viruses

Vero cells were cultured in Minimal Essential Medium (Corning Cellgro, Manassas, VA) containing 5% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Gibco-Invitrogen, Gaithersburg, MD). Viruses were kindly supplied by Dr. D. Watkins and included Zika-Paraiba 2015, DENV-1 Western Pacific U88535.1, DENV-2 NGC AF038403.1, DENV-3 Selman/78 AY648961, and DENV4 AF326825.1. Vero cells were infected with each virus and maintained until 50% reduction in viability was observed after which supernatant was collected, filtered, and stored at −80°C.

Antibody sequencing

Reverse transcription and subsequent PCR amplification of heavy and light chain variable genes were performed using SuperScriptIII (Life Technologies) according to published protocols (51). All PCR reactions were performed in 25ml volume with 2.5ml of cDNA transcript using HotStar Taq DNA polymerase master mix (QIAGEN) and mixtures of previously described primers (51). Second round nested-PCR reactions were performed using Phusion proofreading polymerase (NEB). Two additional rounds of PCR were performed using primers with barcodes specific to the plate number and well location as well as adapters appropriate for sequencing on an Illumina MiSeq. This reaction was performed in a 25ml volume with HotStar Taq DNA polymerase master mix (QIAGEN). Amplified IgG heavy- and light-chain variable regions were sequenced on an Illumina MiSeq (600-base v3 reagent kit; Illumina) and reads corresponding to the same plate/well location were combined into consensus sequences. Germline assignment was performed with AbStar (https://.github.com/briney/abstar) and clonal lineages were assigned with Clonify (52).

Western Blots

Whole virus ZIKV lysate, whole virus DENV lysate, and recombinant E protein (cat# R01635, Meridian Life Sciences, Memphis, TN) were separated by SDS/PAGE under reducing conditions in 4–20% gels (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) to Polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Thermofisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Membranes were blocked overnight at 4°C in 5% nonfat dry milk (NFDM) in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) containing 0.05% Tween 20 (TBS-T). Subsequently, membranes were incubated with 1:2000 dilution of mAb in 10 ml TBS-T containing 5 % milk for 1 hour and washed three times with TBS-T. The secondary antibody used to detect 4G2 was a goat polyclonal secondary antibody to mouse IgG - H&L (HRP) (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) and the secondary antibody used to detect human mAbs was a goat polyclonal secondary antibody to human IgG - H&L (HRP) (Abcam, Cambridge, MA). Secondary antibodies were diluted 1:2000 in 10 ml TBS-T with 5 % milk and applied to the membrane for 1 hour, and then the membrane was washed three times with TBS-T and developed with HRP development solution (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA)

Focus reduction neutralization test (FRNT)

Virus-specific neutralizing antibody responses were titrated essentially as previously described (53). Briefly, antibody was diluted serially in Minimal Essential Medium (Corning Cellgro, Manassas, VA) containing 5% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Gibco-Invitrogen, Gaithersburg, MD), and incubated 1 hour at 37°C with virus. The initial dilution tested for all mAb was 10 μg/ml and three-fold dilutions were performed. After incubation, the antibody-virus mixture was added in triplicate to 96-well plates containing 80% confluent monolayers of Vero E6 cells. Plates were incubated for 1.5 hours at 37°C. Following the incubation, wells were overlaid with 1% methylcellulose in supplemented MEM media with 2% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Gibco-Invitrogen, Gaithersburg, MD) and 1:100 HEPES (4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid). Plates were incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 40 hours after which cells were fixed and permeabilized with Perm/Wash buffer (BD Biosceinces, San Jose, CA) for 5 minutes. After permeabilization, cells were incubated with 1:2000 dilution of anti-flavivirus antibody (MAB10216) for 2 hours then washed with PBS (EMD Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany). Following washing, cells were incubated with anti-mouse HRP conjugated secondary Ab (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) in Perm/Wash) buffer for 2 hours. Following washing of cells with PBS, plates were developed with peroxidase substrate (KPL, Milford, MA). All viruses were titered to yield 100 plaques per well in the absence of neutralization and fixed at 40 hours to prevent plaque spread/overlap. Experiments were performed in triplicate. Neutralization EC50s were determined using Graphpad Prism software (San Diego, CA). One site - Fit logEC50 was employed using the following model: Y=Bottom + (Top-Bottom)/(1+10^(X-LogEC50)). The top and bottom of the curves were constrained to values of 100 and 0. The EC50 was then defined from the best fit curve for each antibody as defined by the concentration that resulted in 50% reduction in foci number.

Serum ELISAs

For NS1 ELISAs, plates were coated with 5 μg/ml of NS1 proteins diluted in PBS and incubated overnight at 4°C. Wells were washed and then blocked with 3% BSA in PBS for 1 hour at 37°C. Wells were washed and serial dilutions of human plasma diluted in 1% BSA 0.05% Tween-20 were added and incubated for 1 hour at 37°C. Wells were washed and AP-conjugated goat anti-human IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch) secondary was added and incubated for 1 hour at 37°C. Wells were washed twice and developed with para-nitrophenylphosphate in 1x diethanolamine. Plates were read on a Spectramax microplate Reader (Molecular Devices) at 405nm wavelength. For virus binding, ELISA plates were coated with 10 ug/ml of 4G2 (Millipore MAB10216) diluted in PBS and incubated overnight at 4°C. After washing, wells were blocked with 3% BSA in PBS for 1 h at 37°C. After removal of the blocking solution, whole ZIKV or DENV particles diluted in 1% BSA 0.05% Tween-20 were applied to the plates and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. After washing, serum was titrated and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. Wells were washed and AP-conjugated goat anti-human IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch) secondary was added and incubated for 1 hour at 37°C. Wells were washed twice and developed with para-nitrophenylphosphate in 1x diethanolamine. Plates were read on a Spectramax microplate Reader (Molecular Devices) at 405nm wavelength.

MAb binding ELISAs

ELISA plates were coated with 10 ug/ml of 4G2 (Millipore MAB10216) diluted in PBS and incubated overnight at 4°C. After washing, wells were blocked with 3% BSA in PBS for 1 h at 37°C. After removal of the blocking solution, 104 pfu of unpurified ZIKV or DENV particles diluted in 1% BSA 0.05% Tween-20 was added to each well of the ELISA plate and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. After washing, mAbs were either titrated or added at a concentration of 10 ug/ml and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. Wells were washed and AP-conjugated goat anti-human IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch) secondary was added and incubated for 1 hour at 37°C. Wells were washed twice and developed with para-nitrophenylphosphate in 1x diethanolamine. Plates were read on a Spectramax microplate Reader (Molecular Devices) at 405nm wavelength.

Single B cell sorting

For plasmablast sorting, PBMCs were stained using anti-human CD38 (FITC), CD27 (PE-Cy7), CD20 (BUV737), CD3 (APC-Cy7), CD8 (APC-Cy7), and CD14 (APC-H7). Plasmablasts were defined as CD19+ CD3− CD20−/lo CD27high CD38high. For memory B cell sorting, purified B cells were stained using anti-human IgG (BV605), CD27 (BV421), CD8 (PerCP-Cy5.5), CD14 (PerCP-Cy5.5), CD19 (PECy7), CD20 (PECy7) and a mixture of dual-labeled ZIKV E tetramers (50 nM each). Single cells were sorted on a BD FACSAria II into 96-well PCR plates (BioRad) containing 20 μL/well of lysis buffer [5 μL of 5X first strand cDNA buffer (Invitrogen), 0.25 μL RNaseOUT (Invitrogen), 1.25 μL dithiothreitol (Invitrogen), 0.625 μL NP-40 (New England Biolabs), and 12.6 μL dH2O]. Plates were immediately frozen on dry ice before storage at −80°C. Flow cytometry data were analyzed using FlowJo software.

Amplification and cloning of antibody variable genes

Single B cell PCR was performed essentially as previously described (51). Briefly, IgH, Igλ and Igκ variable gene transcripts were amplified by RT-PCR and nested PCR reactions using cocktails of primers specific for IgG (51). The primers used in the second round of PCR contained 40 base pairs of 5′ and 3′ homology to the cut expression vectors to allow for cloning by homologous recombination into Saccharomyces cerevisiae (54). PCR products were cloned into S. cerevisiae using the lithium acetate method for chemical transformation (55). Each transformation reaction contained 20 μl of unpurified heavy chain and light chain PCR product and 200 ng of cut heavy- and light-chain plasmids. Individual yeast colonies were picked for sequencing and down-stream characterization.

Expression and purification of antibodies

Antibodies used for binding experiments, competition assays, neutralization assays, and structural studies were expressed in Saccharomyces cerevisiae cultures grown in 24 well plates (54). After 6 days of growth, the yeast cell culture supernatant was harvested by centrifugation and subject to purification. Cell supernatants were purified by passing over Protein A agarose (MabSelect SuRe™ from GE Healthcare Life Sciences). The bound antibodies were washed with PBS, eluted with 200 mM acetic acid/50 mM NaCl pH 3.5 into 1/8th volume 2M Hepes pH 8.0, and buffer-exchanged into PBS pH 7.0. Fab fragments were generated by digesting the IgGs with papain for 2h at 30°C. The digestion was terminated by the addition of iodoacetamide, and the Fab and Fc mixtures were passed over Protein A agarose to remove Fc fragments and undigested IgG. The flowthrough of the Protein A resin was then passed over CaptureSelect™ IgG-CH1 affinity resin (ThermoFischer Scientific), and eluted with 200 mM acetic acid/50 mM NaCl pH 3.5 into 1/8th volume 2M Hepes pH 8.0. Fab fragments then were buffer-exchanged into PBS pH 7.0.

Biolayer Interferometry binding analysis

IgG binding affinities were determined by BLI measurements using a FortéBio Octet HTX instrument (Pall Life Sciences). For high-throughput binding affinity screening, IgGs were immobilized on AHQ sensors (Pall Life Sciences) and exposed to 100 nM ZIKV E (Meridian Life Science, Inc.), DENV1-4 E (The Native Antigen Company), or NS1 proteins (The Native Antigen Company) in PBS containing 0.1% BSA (PBSF) for an association step, followed by a dissociation step in PBSF buffer. Data was analyzed using the FortéBio Data Analysis Software 7. The data was fit to a 1:1 binding model to calculate an association and dissociation rate, and binding KDs were calculated using the ratio kd/ka.

Antibody competition assays

Antibody competition assays were performed as previously described (54). Antibody competition was measured by the ability of a control anti-ZIKV E Fab to inhibit binding of yeast surface-expressed anti-ZIKV E IgGs to ZIKV E (Meridian Life Science, Inc.). 50 nM biotinylated ZIKV E was pre-incubated with 1 μM competitor Fab for 30 min at RT and then added to a suspension of yeast-expressed anti-ZIKV E IgG. After a 5 min incubation, unbound antigen was removed by washing with PBSF. After washing, bound antigen was detected using Streptavidin Alexa Fluor 633 (Life Technologies) at a 1:500 dilution and analyzed by flow cytometry using a BD FACS Canto II. Results are expressed as the fold reduction in antigen binding in the presence of competitor Fab relative to an antigen-only control.

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism. Statistical significance was determined using an unpaired nonparametric Mann-Whitney test or Kruskal-Wallis test. P values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Supplementary Material

Fig. S1. Binding of acute serum to ZIKV and DENV1-4 viral particles and NS1 proteins.

Fig. S2. Plasmablast sorting.

Fig. S3. Binding of plasmablast-derived mAbs to ZIKV-Para by ELISA.

Fig. S4. Western Blot analysis of mAb binding to ZIKV lysate.

Fig. S5. Heat map of mAb binding reactivity to recombinant ZIKV E, WNV E, DIII, and E-FL.

Fig. S6. MAb binding to recombinant ZIKV and DENV E proteins.

Fig. S7. ELISA binding of whole virus-specific clones to ZIKV and DENV.

Fig. S8. Somatic hypermutation of NS1-specific mAbs.

Fig. S9. Representative neutralization curves.

Fig. S10. Enhancement of ZIKV infection by plasmablast-derived mAbs isolated from DENV-experienced donors.

Fig. S11. Memory B cell sorting.

Fig. S12. Distribution of clonal lineage members across plasmablast and memory B cell subsets.

Fig. S13. Epitope mapping of ZIKV-specific mAbs derived from memory B cells.

Table S1. Clinical characteristics of ZIKV-infected donors.

Table S2. Binding properties of ZIKV E-specific mAbs isolated from plasmablasts.

Table S3. Binding characteristics of mAb 4G2.

Table S4. Sequences of ZV-67 competitor mAbs.

Table S5. Competition of ADI-24247 and ADI-24314 with each other and with control mAbs.

Table S6. Binding properties of NS1-specific mAbs isolated from plasmablasts.

Table S7. Neutralizing activity of selected plasmablast-derived mAbs.

Table S8. Binding properties of ZIKV E-specific mAbs isolated from memory B cells.

Table S9. Clonal lineages shared between plasmablast and memory B cell-derived antibodies.

Table S10. Neutralizing activity of selected memory B cell-derived mAbs.

Acknowledgments

We thank C. Williams and S.M. Eagol for assistance with figure preparation. We thank D. Watkins and D. Magnani for supplying viral stocks for these studies and T. Fredeking for assistance in sample identification. We thank D. Fremont and H. Zhao for domain III, WNV, and the E-FL proteins.

Funding: This work was supported by a grant from the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) Autonomous Diagnostics to Enable Prevention and Therapeutics: Prophylactic Options to Environmental and Contagious Threats (ADEPT-PROTECT) program (W31P4Q-13-1-0011).

Footnotes

Author contributions: L.M.W. wrote the manuscript. T.F.R., E.C.G, D.S., and D.R.B. edited the manuscript. T.F.R., E.C.G, B.B., D.S., N.B., A.S., R.N., K.L., and M.E.B. designed and performed experiments and analyzed results. L.M.W, T.F.R, B.B., D.S., and D.R.B provided intellectual oversight. L.M.W. and T.F.R. performed the statistical analyses.

Competing interests: L.M.W., M.E.B, and E.C.G. have an equity position in Adimab, LLC.

References and notes

- 1.Mlakar J, Korva M, Tul N, Popovic M, Poljsak-Prijatelj M, Mraz J, Kolenc M, Resman Rus K, Vesnaver Vipotnik T, Fabjan Vodusek V, Vizjak A, Pizem J, Petrovec M, Avsic Zupanc T. Zika Virus Associated with Microcephaly. The New England journal of medicine. 2016;374:951–958. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1600651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cao-Lormeau VM, Blake A, Mons S, Lastere S, Roche C, Vanhomwegen J, Dub T, Baudouin L, Teissier A, Larre P, Vial AL, Decam C, Choumet V, Halstead SK, Willison HJ, Musset L, Manuguerra JC, Despres P, Fournier E, Mallet HP, Musso D, Fontanet A, Neil J, Ghawche F. Guillain-Barre Syndrome outbreak associated with Zika virus infection in French Polynesia: a case-control study. Lancet. 2016;387:1531–1539. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00562-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sirohi D, Chen Z, Sun L, Klose T, Pierson TC, Rossmann MG, Kuhn RJ. The 3.8 A resolution cryo-EM structure of Zika virus. Science. 2016;352:467–470. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf5316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barba-Spaeth G, Dejnirattisai W, Rouvinski A, Vaney MC, Medits I, Sharma A, Simon-Loriere E, Sakuntabhai A, Cao-Lormeau VM, Haouz A, England P, Stiasny K, Mongkolsapaya J, Heinz FX, Screaton GR, Rey FA. Structural basis of potent Zika-dengue virus antibody cross-neutralization. Nature. 2016;536:48–53. doi: 10.1038/nature18938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dejnirattisai W, Supasa P, Wongwiwat W, Rouvinski A, Barba-Spaeth G, Duangchinda T, Sakuntabhai A, Cao-Lormeau VM, Malasit P, Rey FA, Mongkolsapaya J, Screaton GR. Dengue virus sero-cross-reactivity drives antibody-dependent enhancement of infection with zika virus. Nat Immunol. 2016;17:1102–1108. doi: 10.1038/ni.3515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Priyamvada L, Quicke KM, Hudson WH, Onlamoon N, Sewatanon J, Edupuganti S, Pattanapanyasat K, Chokephaibulkit K, Mulligan MJ, Wilson PC, Ahmed R, Suthar MS, Wrammert J. Human antibody responses after dengue virus infection are highly cross-reactive to Zika virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:7852–7857. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1607931113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stettler K, Beltramello M, Espinosa DA, Graham V, Cassotta A, Bianchi S, Vanzetta F, Minola A, Jaconi S, Mele F, Foglierini M, Pedotti M, Simonelli L, Dowall S, Atkinson B, Percivalle E, Simmons CP, Varani L, Blum J, Baldanti F, Cameroni E, Hewson R, Harris E, Lanzavecchia A, Sallusto F, Corti D. Specificity, cross-reactivity, and function of antibodies elicited by Zika virus infection. Science. 2016;353:823–826. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf8505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Halstead SB. Neutralization and antibody-dependent enhancement of dengue viruses. Adv Virus Res. 2003;60:421–467. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3527(03)60011-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kliks SC, Nimmanitya S, Nisalak A, Burke DS. Evidence that maternal dengue antibodies are important in the development of dengue hemorrhagic fever in infants. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1988;38:411–419. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1988.38.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simmons CP, Chau TN, Thuy TT, Tuan NM, Hoang DM, Thien NT, Lien le B, Quy NT, Hieu NT, Hien TT, McElnea C, Young P, Whitehead S, Hung NT, Farrar J. Maternal antibody and viral factors in the pathogenesis of dengue virus in infants. J Infect Dis. 2007;196:416–424. doi: 10.1086/519170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kawiecki AB, Christofferson RC. Zika Virus-Induced Antibody Response Enhances Dengue Virus Serotype 2 Replication In Vitro. J Infect Dis. 2016;214:1357–1360. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Castanha PM, Nascimento EJ, Cynthia B, Cordeiro MT, de Carvalho OV, de Mendonca LR, Azevedo EA, Franca RF, Rafael D, Marques ET., Jr Dengue virus (DENV)-specific antibodies enhance Brazilian Zika virus (ZIKV) infection. J Infect Dis. 2016 doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Durbin AP. Dengue Antibody and Zika: Friend or Foe? Trends Immunol. 2016;37:635–636. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2016.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bardina SV, Bunduc P, Tripathi S, Duehr J, Frere JJ, Brown JA, Nachbagauer R, Foster GA, Krysztof D, Tortorella D, Stramer SL, Garcia-Sastre A, Krammer F, Lim JK. Enhancement of Zika virus pathogenesis by preexisting antiflavivirus immunity. Science. 2017;356:175–180. doi: 10.1126/science.aal4365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Muller DA, Young PR. The flavivirus NS1 protein: molecular and structural biology, immunology, role in pathogenesis and application as a diagnostic biomarker. Antiviral Res. 2013;98:192–208. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2013.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beltramello M, Williams KL, Simmons CP, Macagno A, Simonelli L, Quyen NT, Sukupolvi-Petty S, Navarro-Sanchez E, Young PR, de Silva AM, Rey FA, Varani L, Whitehead SS, Diamond MS, Harris E, Lanzavecchia A, Sallusto F. The human immune response to Dengue virus is dominated by highly cross-reactive antibodies endowed with neutralizing and enhancing activity. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;8:271–283. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Priyamvada L, Cho A, Onlamoon N, Zheng NY, Huang M, Kovalenkov Y, Chokephaibulkit K, Angkasekwinai N, Pattanapanyasat K, Ahmed R, Wilson PC, Wrammert J. B Cell Responses during Secondary Dengue Virus Infection Are Dominated by Highly Cross-Reactive, Memory-Derived Plasmablasts. J Virol. 2016;90:5574–5585. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03203-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li L, Lok SM, Yu IM, Zhang Y, Kuhn RJ, Chen J, Rossmann MG. The flavivirus precursor membrane-envelope protein complex: structure and maturation. Science. 2008;319:1830–1834. doi: 10.1126/science.1153263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Modis Y, Ogata S, Clements D, Harrison SC. Structure of the dengue virus envelope protein after membrane fusion. Nature. 2004;427:313–319. doi: 10.1038/nature02165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sapparapu G, Fernandez E, Kose N, Cao B, Fox JM, Bombardi RG, Zhao H, Nelson CA, Bryan AL, Barnes T, Davidson E, Mysorekar IU, Fremont DH, Doranz BJ, Diamond MS, Crowe JE. Neutralizing human antibodies prevent Zika virus replication and fetal disease in mice. Nature. 2016 doi: 10.1038/nature20564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bhatt S, Gething PW, Brady OJ, Messina JP, Farlow AW, Moyes CL, Drake JM, Brownstein JS, Hoen AG, Sankoh O, Myers MF, George DB, Jaenisch T, Wint GR, Simmons CP, Scott TW, Farrar JJ, Hay SI. The global distribution and burden of dengue. Nature. 2013;496:504–507. doi: 10.1038/nature12060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lustig Y, Zelena H, Venturi G, Van Esbroeck M, Rothe C, Perret C, Koren R, Katz-Likvornik S, Mendelson E, Schwartz E. Sensitivity and kinetics of a NS1-based Zika virus ELISA in Zika infected travelers from Israel, Czech Republic, Italy, Belgium, Germany and Chile. J Clin Microbiol. 2017 doi: 10.1128/JCM.00346-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huzly D, Hanselmann I, Schmidt-Chanasit J, Panning M. High specificity of a novel Zika virus ELISA in European patients after exposure to different flaviviruses. Euro Surveill. 2016;21 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2016.21.16.30203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wrammert J, Onlamoon N, Akondy RS, Perng GC, Polsrila K, Chandele A, Kwissa M, Pulendran B, Wilson PC, Wittawatmongkol O, Yoksan S, Angkasekwinai N, Pattanapanyasat K, Chokephaibulkit K, Ahmed R. Rapid and massive virus-specific plasmablast responses during acute dengue virus infection in humans. J Virol. 2012;86:2911–2918. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06075-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wrammert J, Smith K, Miller J, Langley WA, Kokko K, Larsen C, Zheng NY, Mays I, Garman L, Helms C, James J, Air GM, Capra JD, Ahmed R, Wilson PC. Rapid cloning of high-affinity human monoclonal antibodies against influenza virus. Nature. 2008;453:667–671. doi: 10.1038/nature06890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee FE, Halliley JL, Walsh EE, Moscatiello AP, Kmush BL, Falsey AR, Randall TD, Kaminiski DA, Miller RK, Sanz I. Circulating human antibody-secreting cells during vaccinations and respiratory viral infections are characterized by high specificity and lack of bystander effect. J Immunol. 2011;186:5514–5521. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dejnirattisai W, Wongwiwat W, Supasa S, Zhang X, Dai X, Rouvinski A, Jumnainsong A, Edwards C, Quyen NT, Duangchinda T, Grimes JM, Tsai WY, Lai CY, Wang WK, Malasit P, Farrar J, Simmons CP, Zhou ZH, Rey FA, Mongkolsapaya J, Screaton GR. A new class of highly potent, broadly neutralizing antibodies isolated from viremic patients infected with dengue virus. Nat Immunol. 2015;16:170–177. doi: 10.1038/ni.3058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dejnirattisai W, Jumnainsong A, Onsirisakul N, Fitton P, Vasanawathana S, Limpitikul W, Puttikhunt C, Edwards C, Duangchinda T, Supasa S, Chawansuntati K, Malasit P, Mongkolsapaya J, Screaton G. Cross-reacting antibodies enhance dengue virus infection in humans. Science. 2010;328:745–748. doi: 10.1126/science.1185181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rouvinski A, Guardado-Calvo P, Barba-Spaeth G, Duquerroy S, Vaney MC, Kikuti CM, Navarro Sanchez ME, Dejnirattisai W, Wongwiwat W, Haouz A, Girard-Blanc C, Petres S, Shepard WE, Despres P, Arenzana-Seisdedos F, Dussart P, Mongkolsapaya J, Screaton GR, Rey FA. Recognition determinants of broadly neutralizing human antibodies against dengue viruses. Nature. 2015;520:109–113. doi: 10.1038/nature14130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhao H, Fernandez E, Dowd KA, Speer SD, Platt DJ, Gorman MJ, Govero J, Nelson CA, Pierson TC, Diamond MS, Fremont DH. Structural Basis of Zika Virus-Specific Antibody Protection. Cell. 2016;166:1016–1027. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gentry MK, Henchal EA, McCown JM, Brandt WE, Dalrymple JM. Identification of distinct antigenic determinants on dengue-2 virus using monoclonal antibodies. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1982;31:548–555. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1982.31.548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robbiani DF, Bozzacco L, Keeffe JR, Khouri R, Olsen PC, Gazumyan A, Schaefer-Babajew D, Avila-Rios S, Nogueira L, Patel R, Azzopardi SA, Uhl LFK, Saeed M, Sevilla-Reyes EE, Agudelo M, Yao K-H, Golijanin J, Gristick HB, Lee YE, Hurley A, Caskey M, Pai J, Oliveira T, Wunder EA, Jr, Sacramento G, Nery N, Jr, Orge C, Costa F, Reis MG, Thomas NM, Eisenreich T, Weinberger DM, de Almeida ARP, West AP, Jr, Rice CM, Bjorkman PJ, Reyes-Teran G, Ko AI, MacDonald MR, Nussenzweig MC. Recurrent Potent Human Neutralizing Antibodies to Zika Virus in Brazil and Mexico. Cell. 169:597–609.e511. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oliphant T, Nybakken GE, Engle M, Xu Q, Nelson CA, Sukupolvi-Petty S, Marri A, Lachmi BE, Olshevsky U, Fremont DH, Pierson TC, Diamond MS. Antibody recognition and neutralization determinants on domains I and II of West Nile Virus envelope protein. J Virol. 2006;80:12149–12159. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01732-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McHeyzer-Williams LJ, Milpied PJ, Okitsu SL, McHeyzer-Williams MG. Class-switched memory B cells remodel BCRs within secondary germinal centers. Nat Immunol. 2015;16:296–305. doi: 10.1038/ni.3095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zuccarino-Catania GV, Sadanand S, Weisel FJ, Tomayko MM, Meng H, Kleinstein SH, Good-Jacobson KL, Shlomchik MJ. CD80 and PD-L2 define functionally distinct memory B cell subsets that are independent of antibody isotype. Nat Immunol. 2014;15:631–637. doi: 10.1038/ni.2914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pape KA, Taylor JJ, Maul RW, Gearhart PJ, Jenkins MK. Different B cell populations mediate early and late memory during an endogenous immune response. Science. 2011;331:1203–1207. doi: 10.1126/science.1201730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Garcia-Bates TM, Cordeiro MT, Nascimento EJ, Smith AP, Soares de Melo KM, McBurney SP, Evans JD, Marques ET, Jr, Barratt-Boyes SM. Association between magnitude of the virus-specific plasmablast response and disease severity in dengue patients. J Immunol. 2013;190:80–87. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Blanchard-Rohner G, Pulickal AS, Jol-van der Zijde CM, Snape MD, Pollard AJ. Appearance of peripheral blood plasma cells and memory B cells in a primary and secondary immune response in humans. Blood. 2009;114:4998–5002. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-211052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim JH, Skountzou I, Compans R, Jacob J. Original antigenic sin responses to influenza viruses. J Immunol. 2009;183:3294–3301. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.de St Fazekas G, Webster RG. Disquisitions of Original Antigenic Sin. I. Evidence in man. J Exp Med. 1966;124:331–345. doi: 10.1084/jem.124.3.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Choi YS, Baek YH, Kang W, Nam SJ, Lee J, You S, Chang DY, Youn JC, Choi YK, Shin EC. Reduced antibody responses to the pandemic (H1N1) 2009 vaccine after recent seasonal influenza vaccination. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2011;18:1519–1523. doi: 10.1128/CVI.05053-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Midgley CM, Bajwa-Joseph M, Vasanawathana S, Limpitikul W, Wills B, Flanagan A, Waiyaiya E, Tran HB, Cowper AE, Chotiyarnwong P, Grimes JM, Yoksan S, Malasit P, Simmons CP, Mongkolsapaya J, Screaton GR. An in-depth analysis of original antigenic sin in dengue virus infection. J Virol. 2011;85:410–421. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01826-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Halstead SB, Rojanasuphot S, Sangkawibha N. Original antigenic sin in dengue. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1983;32:154–156. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1983.32.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Abbink P, Larocca RA, De La Barrera RA, Bricault CA, Moseley ET, Boyd M, Kirilova M, Li Z, Ng’ang’a D, Nanayakkara O, Nityanandam R, Mercado NB, Borducchi EN, Agarwal A, Brinkman AL, Cabral C, Chandrashekar A, Giglio PB, Jetton D, Jimenez J, Lee BC, Mojta S, Molloy K, Shetty M, Neubauer GH, Stephenson KE, Peron JP, Zanotto PM, Misamore J, Finneyfrock B, Lewis MG, Alter G, Modjarrad K, Jarman RG, Eckels KH, Michael NL, Thomas SJ, Barouch DH. Protective efficacy of multiple vaccine platforms against Zika virus challenge in rhesus monkeys. Science. 2016;353:1129–1132. doi: 10.1126/science.aah6157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dowd KA, Ko SY, Morabito KM, Yang ES, Pelc RS, DeMaso CR, Castilho LR, Abbink P, Boyd M, Nityanandam R, Gordon DN, Gallagher JR, Chen X, Todd JP, Tsybovsky Y, Harris A, Huang YS, Higgs S, Vanlandingham DL, Andersen H, Lewis MG, De La Barrera R, Eckels KH, Jarman RG, Nason MC, Barouch DH, Roederer M, Kong WP, Mascola JR, Pierson TC, Graham BS. Rapid development of a DNA vaccine for Zika virus. Science. 2016;354:237–240. doi: 10.1126/science.aai9137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Larocca RA, Abbink P, Peron JP, Zanotto PM, Iampietro MJ, Badamchi-Zadeh A, Boyd M, Ng’ang’a D, Kirilova M, Nityanandam R, Mercado NB, Li Z, Moseley ET, Bricault CA, Borducchi EN, Giglio PB, Jetton D, Neubauer G, Nkolola JP, Maxfield LF, De La Barrera RA, Jarman RG, Eckels KH, Michael NL, Thomas SJ, Barouch DH. Vaccine protection against Zika virus from Brazil. Nature. 2016;536:474–478. doi: 10.1038/nature18952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kim E, Erdos G, Huang S, Kenniston T, Falo LD, Jr, Gambotto A. Preventative Vaccines for Zika Virus Outbreak: Preliminary Evaluation. EBioMedicine. 2016;13:315–320. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.09.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pardi N, Hogan MJ, Pelc RS, Muramatsu H, Andersen H, DeMaso CR, Dowd KA, Sutherland LL, Scearce RM, Parks R, Wagner W, Granados A, Greenhouse J, Walker M, Willis E, Yu JS, McGee CE, Sempowski GD, Mui BL, Tam YK, Huang YJ, Vanlandingham D, Holmes VM, Balachandran H, Sahu S, Lifton M, Higgs S, Hensley SE, Madden TD, Hope MJ, Kariko K, Santra S, Graham BS, Lewis MG, Pierson TC, Haynes BF, Weissman D. Zika virus protection by a single low-dose nucleoside-modified mRNA vaccination. Nature. 2017 doi: 10.1038/nature21428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Richner JM, Himansu S, Dowd KA, Butler SL, Salazar V, Fox JM, Julander JG, Tang WW, Shresta S, Pierson TC, Ciaramella G, Diamond MS. Modified mRNA Vaccines Protect against Zika Virus Infection. Cell. 2017;169:176. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fuss IJ, Kanof ME, Smith PD, Zola H. Isolation of whole mononuclear cells from peripheral blood and cord blood. Curr Protoc Immunol. 2009;Chapter 7(Unit7):1. doi: 10.1002/0471142735.im0701s85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tiller T, Meffre E, Yurasov S, Tsuiji M, Nussenzweig MC, Wardemann H. Efficient generation of monoclonal antibodies from single human B cells by single cell RT-PCR and expression vector cloning. J Immunol Methods. 2008;329:112–124. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2007.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Briney B, Le K, Zhu J, Burton DR. Clonify: unseeded antibody lineage assignment from next-generation sequencing data. Sci Rep. 2016;6:23901. doi: 10.1038/srep23901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Brien JD, Lazear HM, Diamond MS. Propagation, quantification, detection, and storage of West Nile virus. Curr Protoc Microbiol. 2013;31:15D 13 11–15D 13 18. doi: 10.1002/9780471729259.mc15d03s31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bornholdt ZA, Turner HL, Murin CD, Li W, Sok D, Souders CA, Piper AE, Goff A, Shamblin JD, Wollen SE, Sprague TR, Fusco ML, Pommert KB, Cavacini LA, Smith HL, Klempner M, Reimann KA, Krauland E, Gerngross TU, Wittrup KD, Saphire EO, Burton DR, Glass PJ, Ward AB, Walker LM. Isolation of potent neutralizing antibodies from a survivor of the 2014 Ebola virus outbreak. Science. 2016;351:1078–1083. doi: 10.1126/science.aad5788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gietz RD, Schiestl RH. High-efficiency yeast transformation using the LiAc/SS carrier DNA/PEG method. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:31–34. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1. Binding of acute serum to ZIKV and DENV1-4 viral particles and NS1 proteins.

Fig. S2. Plasmablast sorting.

Fig. S3. Binding of plasmablast-derived mAbs to ZIKV-Para by ELISA.

Fig. S4. Western Blot analysis of mAb binding to ZIKV lysate.

Fig. S5. Heat map of mAb binding reactivity to recombinant ZIKV E, WNV E, DIII, and E-FL.

Fig. S6. MAb binding to recombinant ZIKV and DENV E proteins.

Fig. S7. ELISA binding of whole virus-specific clones to ZIKV and DENV.

Fig. S8. Somatic hypermutation of NS1-specific mAbs.

Fig. S9. Representative neutralization curves.

Fig. S10. Enhancement of ZIKV infection by plasmablast-derived mAbs isolated from DENV-experienced donors.

Fig. S11. Memory B cell sorting.

Fig. S12. Distribution of clonal lineage members across plasmablast and memory B cell subsets.

Fig. S13. Epitope mapping of ZIKV-specific mAbs derived from memory B cells.

Table S1. Clinical characteristics of ZIKV-infected donors.

Table S2. Binding properties of ZIKV E-specific mAbs isolated from plasmablasts.

Table S3. Binding characteristics of mAb 4G2.

Table S4. Sequences of ZV-67 competitor mAbs.

Table S5. Competition of ADI-24247 and ADI-24314 with each other and with control mAbs.

Table S6. Binding properties of NS1-specific mAbs isolated from plasmablasts.

Table S7. Neutralizing activity of selected plasmablast-derived mAbs.

Table S8. Binding properties of ZIKV E-specific mAbs isolated from memory B cells.

Table S9. Clonal lineages shared between plasmablast and memory B cell-derived antibodies.

Table S10. Neutralizing activity of selected memory B cell-derived mAbs.