Abstract

Health plan policies can influence delivery of integrated behavioral health and general medical care. This study provides national estimates for the prevalence of practices used by health plans that may support behavioral health integration. Results indicate that health plans employ financing and other policies likely to support integration. They also directly provide services that facilitate integration. Behavioral health contracting arrangements are associated with use of these policies. Delivery of integrated care requires systemic changes by both providers and payers thus health plans are key players in achieving this goal.

Keywords: health insurance, mental health, substance use, integration, health reform

Introduction

Delivery of clinically integrated behavioral health and general medical care often results in improved clinical outcomes and patient care experiences.1–8 Evidence for cost-effectiveness of integrated care is mixed with many studies limited by short time horizons and others finding cost reductions only for subsets of patients.7–12 Recent market and delivery system reforms encourage a move to more integrated behavioral health and primary care by expanding access to behavioral health care and supporting alternative delivery and payment systems. Specifically, the 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) expanded benefits by including mental health and substance use disorder services in the essential benefits package. The ACA also encouraged the development and diffusion of new delivery and financing models such as Patient-Centered Medical Homes (PCMH) and Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs)13 which emphasize the delivery of care that is patient-centered, team-based, and well-coordinated—important concepts in all models of integrated care.14,15

Clinical integration exists along a continuum from basic through fully integrated. When care is fully clinically integrated primary and behavioral health providers collaborate closely and develop shared treatment plans.3 Key features of clinically integrated care models include coordination between behavioral health and primary care and delivering necessary services where patients seek care.3 Despite evidence for improved health outcomes and support for behavioral health integration in the ACA, many health care delivery systems have yet to adopt integrated models of care.16 In many cases, delivery systems are not organized in ways that are supportive of integration and tend to rely on payment structures (e.g., fee-for-service) that do not reimburse for care coordination and other key tasks involved in integration.17,18

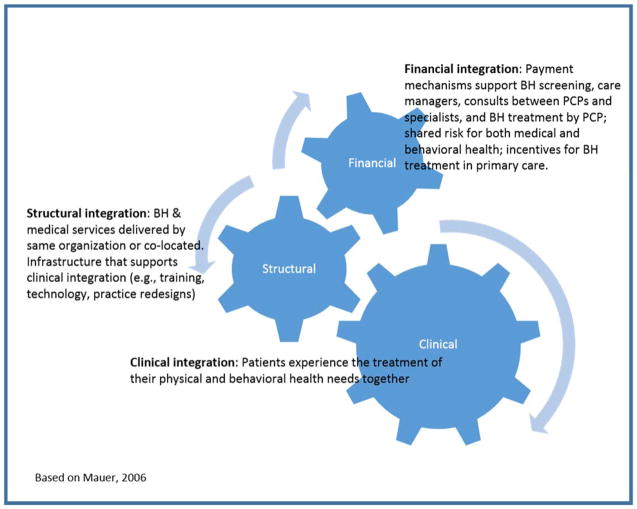

Clinical integration is more likely to occur when financial and structural integration exist (see Figure 1). Financial policies and structural systems can be barriers to achieving integrated care. Changes to these policies in order to establish financial and structural integration are required to move toward clinical integration.19. Although financial and structural integration are necessary, they are not sufficient to achieve clinical integration.19 While some structural barriers to clinical integration--such as workforce preparedness and training, leadership and data systems—require changes by delivery systems and providers, financial barriers require changes by payers and health insurance companies. As intermediaries between payers, providers, and patients, health insurance companies are uniquely positioned to implement payment and contracting policies that support integrated care along the continuum, and may be driven to do so to meet the demands of their purchasers and the needs of their beneficiaries.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework

The aim of this study is to present nationally representative estimates of the prevalence of health plan policies related to integration of behavioral health and primary care. The two main research questions we explore are first, to what extent do health plans employ payment policies supportive of integration and second, to what extent do health plans directly provide services to coordinate behavioral health and general medical care?

Study Data and Methods

Data are from the third round of a nationally representative survey of commercial health plans regarding mental health and substance use services (together called behavioral health services) for the 2010 benefit year. The phone survey was administered to senior health plan executives from September 2010 – June 2011. Executive directors primarily responded concerning administrative issues (e.g., plan characteristics, benefit design) and the medical director or the behavioral health medical director addressed clinical questions (e.g., utilization management). Plans occasionally referred interviewers to their managed behavioral health organization (MBHO) contractor for additional information. For some national or regional plans, respondents were interviewed regarding multiple sites.

Items were asked at the product level (e.g., health maintenance organization (HMO), preferred provider organization (PPO), point of service (POS) product) within each market-area-specific plan. For all products, plans were asked whether they covered behavioral health services and the proportion of members with behavioral health coverage. All other questions focused on the plan’s top three commercial products. Data were also collected by contracting type because health plans may manage behavioral health services internally or contract with a MBHO, which may affect their ability to support delivery of integrated care. Contracting approaches fell into one of three categories: external (contracted with an MBHO for delivery and management of behavioral health); hybrid internal (behavioral health services managed by a specialty behavioral health organization that is part of the same parent organization as the health plan, and which also contracts with other health plans); or traditional internal (all behavioral health services provided by plan employees or a network of providers administered by the plan). Products with specialty external contracts were more likely to report not knowing answers to several integration-related questions, perhaps reflecting that the respondent was focused on behavioral health (or was part of the MBHO) so did not know details about policies related to primary care. Therefore, for some tables, the percent of products that were unable to respond to specific questions is included.

This study employed a panel survey design with replacement and has been described previously.20 For 2010, 438 eligible plans were identified, of which 389 responded (89% response rate) to the administrative potion of the survey and reported on 939 insurance products. For the clinical portion of the survey, 385 plans responded (88% response rate), reporting on 925 products.

Measures

The behavioral health integration survey module was newly developed for this round of the survey through literature review and key informant interviews, with support from an expert panel of researchers and clinicians working on integrated care. Questions were developed, reviewed, pilot tested with health plans not selected for the study sample, and revised in consultation with these experts before fielding the survey. The questions focused on health plan activities related to financial and clinical integration. Structural integration was not addressed in this survey. The questions focused on activities that can support delivery of care along the continuum of integration. The continuum ranges from basic, in which there is minimal collaboration with behavioral health providers and patients are referred out for treatment; to collocated care, in which providers collaborate, but still have separate cultures and treatment plans; through fully integrated care in which primary and behavioral health providers collaborate closely and develop shared treatment plans.3 Together with the expert panel, health plan activities to support care delivery along this continuum were identified. While much of the work of integration happens within the delivery system, financial integration is required to support clinical integration and our expert panel identified health plan reimbursement and payment policies that support and encourage a move toward integrated care.

In order to examine the extent to which health plans employ payment policies supportive of integration the survey asked, 1) whether health plans reimburse primary care providers for services to coordinate behavioral health care; 2) if PCPs are offered financial incentives to meet pre-announced quality or outcome standards focusing on primary care treatment of behavioral health conditions; and 3) whether, to facilitate coordination between PCPs and specialty behavioral health providers, PCPs are given increased reimbursement for care delivered in integrated settings of behavioral health with medical care. To examine the extent to which health plans directly provide services to coordinate behavioral health and general medical care, the survey queried health plans about their own activities such as providing 1) case management, 2) behavioral health interventionists and 3) consultation that are designed to directly support coordination of behavioral health and primary care. Finally, the survey examined three specific examples of how health plans might support incorporating evidence-based practices for behavioral health into primary care. Specifically, we examined how health plans encourage the use of substance use screening and brief intervention (SBI) by primary care providers, an important initial service for risky drinking, and medication management for alcohol and opiate dependence in primary care.

Most questions were yes/no, and some also included follow-up to gather more detail. The tables use the specific language from the questions. For the payment policies in table 1 and direct service provision policies in table 3, index variables were constructed representing the number of policies within the type that the product endorsed. For example, within payment policies, how many different policies did a product endorse? These index variables indicate products’ overall support for the two types of policies and are shown at the bottom of each table.

Table 1.

Health plan financing policies that facilitate a continuum of behavioral health (BH) and general medical care integration practices, 2010

| Contracting Arrangements | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Specialty External | Hybrid Internal | Internal | |||||

| % | SE | % | SE | % | SE | % | SE | |

| N | 8,427 | 1,219 | 5,899 | 1,278 | ||||

| Reimbursement policies supporting delivery of BH services within primary care | ||||||||

| Talking to patients by phone or email for issues specific to BH | ||||||||

| Yes | 21.7 | 1.6 | 11.8 | 6.5 | 25.7 c | 1.2 | 7.4 c | 5.2 |

| No | 49.8 | 2.0 | 48.6 | 9.4 | 41.4 | 2.1 | 92.2 | 5.2 |

| Don’t know | 28.6 | 1.4 | 39.6 b | 9.9 | 33.0 c | 1.7 | 0.4 b,c | 0.3 |

| Case managers to address BH issues in primary care | ||||||||

| Yes | 36.7 | 1.8 | 3.1 a,b | 2.3 | 47.3 a,c | 1.2 | 16.0 b,c | 3.3 |

| No | 63.1 | 1.8 | 94.8 | 3.4 | 52.7 | 1.2 | 84.0 | 3.3 |

| Don’t know | 0.3 | 0.3 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Consultation between primary care provider/staff & BH provider to support BH services in primary care | ||||||||

| Yes | 8.8 | 1.4 | 18.9 a | 4.0 | 4.0 a,c | 0.9 | 23.7 c | 5.9 |

| No | 90.9 | 1.4 | 79.0 | 4.5 | 96.0 | 0.9 | 76.4 | 5.9 |

| Don’t know | 0.3 | 0.3 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Provide financial incentives to primary care providers focused on treatment of | ||||||||

| Depression | ||||||||

| Yes | 18.3 | 1.2 | 0.3 a,b | 0.2 | 24.9 a,c | 1.2 | 5.5 b,c | 1.5 |

| No | 77.2 | 1.4 | 74.9 | 6.8 | 75.1 | 1.2 | 88.5 | 4.9 |

| Don’t know | 4.5 | 1.6 | 24.8 a,b | 6.8 | 0.0 a | 0.0 | 6.1 b | 5.1 |

| Substance use disorders* | ||||||||

| Yes | 17.7 | 1.2 | 0.0 b | 0.0 | 24.9 c | 1.2 | 1.5 b,c | 1.0 |

| No | 77.8 | 1.4 | 75.2 | 6.8 | 75.1 | 1.2 | 92.4 | 5.1 |

| Don’t know | 4.5 | 1.6 | 24.8 a,b | 6.8 | 0.0 a | 0.0 | 6.1 b | 5.1 |

| Reimbursement policies supporting coordination between primary and specialty BH care | ||||||||

| Increased reimbursed for care delivered in integrated settings of BH with medical care (e.g. medical home) | ||||||||

| Yes | 34.5 | 1.5 | 22.7 | 7.6 | 39.9 c | 1.5 | 13.3 c | 2.9 |

| No | 62.4 | 1.6 | 42.3 | 9.2 | 60.1 | 1.5 | 85.9 | 3.0 |

| Don’t know | 3.1 | 1.0 | 35.0 a,b | 9.7 | 0.0 a | 0.0 | 0.9 b | 0.5 |

| Services delivered by BH provider co-located in medical practice | ||||||||

| Yes | 66.0 | 2.1 | 30.0 a,b | 5.3 | 67.1 a,c | 1.7 | 96.4 b,c | 1.5 |

| No | 33.8 | 2.1 | 67.9 | 5.6 | 33.0 | 1.7 | 3.6 | 1.5 |

| Don’t know | 0.3 | 0.3 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 |

| BH therapy and medical evaluation & management codes billed on same day | ||||||||

| Yes | 89.1 | 2.0 | 36.2 a,b | 5.7 | 98.5 a | 0.4 | 94.2 b | 2.0 |

| No | 10.6 | 2.0 | 61.7 | 6.0 | 1.5 | 0.4 | 5.8 | 2.0 |

| Don’t know | 0.3 | 0.3 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Composite measure of queried financing policies to support integration (0 to 6)** | ||||||||

| 0 | 1.3 | 0.5 | 16.4 a,b | 6.6 | 0.0 a,c | 0.0 | 0.8 b,c | 0.4 |

| 1 | 24.3 | 1.7 | 12.7 b | 3.0 | 17.3 c | 1.0 | 63.3 b,c | 5.8 |

| 2 | 46.5 | 1.5 | 40.4 b | 10.7 | 53.5 c | 1.2 | 14.8 b,c | 2.2 |

| 3 | 27.0 | 1.6 | 29.4 | 9.1 | 29.2 c | 1.6 | 15.8 c | 5.5 |

| 4 or more | 0.9 | 0.2 | 1.2 b | 1.4 | 0.0 c | 0.0 | 5.2 b,c | 1.5 |

N represents weighted total number of products

Pairs that share a superscript letter within row are significantly different (P<0.05); “No” responses not tested.

Asked separately for alcohol dependence and drug use disorders; responses were identical

Index variable of the following reimbursement policies: (1) taking to patients by phone or email, (2) case manager, (3) consultation, (4) any financial incentives, (5) care in integrated settings, and (6) care in co-located settings

Percentages are based on reported data with missing data excluded. Missing data are less than 3% except for talking to patients by phone or email (8%) and increased reimbursement for care delivered in integrated settings (9%)

Table 3.

Services health plans provide to coordinate behavioral health and general medical care, 2010

| Contracting Arrangements | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Specialty External | Hybrid Internal | Internal | |||||

| % | SE | % | SE | % | SE | % | SE | |

| N | 8,427 | 1,219 | 5,899 | 1,278 | ||||

| Case management | ||||||||

| Yes | 94.3 | 1.3 | 62.3 a | 9.9 | 100.0 a,c | 0.0 | 84.3 c | 2.3 |

| No | 2.6 | 0.5 | 2.8 | 2.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 14.8 | 2.3 |

| Don’t know | 3.1 | 1.1 | 34.9 a,b | 9.8 | 0.0 a | 0.0 | 0.9 b | 0.5 |

| Interventionist | ||||||||

| Yes | 35.1 | 2.2 | 28.7 | 7.9 | 40.7 c | 2.2 | 8.8 c | 5.5 |

| No | 61.8 | 1.9 | 36.5 | 9.0 | 59.3 | 2.2 | 90.3 | 5.5 |

| Don’t know | 3.1 | 1.1 | 34.9 a,b | 9.8 | 0.0 a | 0.0 | 0.9 b | 0.5 |

| Consultation | ||||||||

| Yes | 42.9 | 1.7 | 40.1 b | 9.3 | 49.5 c | 1.2 | 9.1 b,c | 5.6 |

| No | 54.0 | 1.4 | 25.1 | 6.8 | 50.5 | 1.2 | 90.0 | 5.6 |

| Don’t know | 3.1 | 1.1 | 34.9 a,b | 9.8 | 0.0 a | 0.0 | 0.9 b | 0.5 |

| Composite measure of queried services to support integration (0 to 3)* | ||||||||

| 0 | 2.4 | 0.5 | 0.8 b | 0.6 | 0.0 c | 0.0 | 14.8 b,c | 2.4 |

| 1 | 33.4 | 2.1 | 37.8 b | 9.6 | 25.6 c | 1.4 | 75.6 b,c | 6.4 |

| 2 | 48.1 | 1.8 | 21.0 a | 10.5 | 58.6 a, c | 2.1 | 1.5 c | 1.3 |

| 3 | 16.1 | 1.3 | 40.5 a,b | 9.8 | 15.8 a | 1.9 | 8.2 b | 5.5 |

N represents weighted total number of products

Pairs that share a superscript letter within row are significantly different (P<0.05); “No” responses not tested.

Index variable of the following three services: (1) case management, (2) interventionist, (3) consultation.

Percentages are based on reported data with missing data excluded (9% for each variable)

Statistical analysis

Univariate and bivariate statistics were calculated. The data are shown by behavioral health contracting arrangement. The data are weighted to be nationally representative of commercial managed care products in the continental United States, resulting in a weighted sample of 8,427 products. The weights were computed at the plan level according to (1) probability of a site being selected and (2) probability of a health plan being selected within a selected site. Analyses were conducted in SUDAAN 11.0.1 because of the complex sampling design. Significance is based on pairwise t-tests with a .05 significance level, adjusted for multiple comparisons (three pairwise tests for each comparison by behavioral health management arrangement) using the Bonferroni correction.

Study Results

Do health plans engage in activities related to financial integration?

Health plans can institute a range of payment policies and incentives that support delivery of behavioral health services within primary care, or that encourage coordination between primary care and specialty behavioral health care (Table 1). These policies fall under the domain of financial integration. The reported prevalence of these activities varied depending on the specific activity and products’ behavioral health contracting arrangement. About one fifth of all products offered reimbursement for PCPs to talk with patients by phone or e-mail regarding behavioral health issues. This was most common among hybrid internal products. About one third of all products offered reimbursement for a case manager to address behavioral health issues. This was reported by nearly half of the hybrid internal products, significantly more than other products. Paying for consultation between primary care and specialty behavioral health providers was rare overall (8.8%) and highest in the internal products (23.7%). Financial incentives focused on treatment of depression or substance use disorders were not common. The prevalence of these incentives was concentrated in hybrid internal products, of which about 25% offered such incentives.

Increased reimbursement for care delivered in integrated settings was offered by 34.5% of all products. This was significantly more common among products with hybrid internal rather than internal arrangements. About two thirds (66.0%) of products reimbursed for services delivered by a behavioral health specialist co-located in a medical practice. This policy was found in over 95% of products with an internal arrangement, compared with only a third of products with an external specialty contract. The vast majority (89.1%) of products accepted billing for behavioral health therapy and medical evaluation and management on the same day. However, only a third of products with specialty external contracts accepted this billing compared with nearly all products with hybrid internal or internal behavioral health arrangements.

Overall, nearly three quarters of products reported two or more of these reimbursement policies or incentives to support a continuum of integration practices. Less than 1% of products had 4 to 6 policies. Products with specialty external contracts were significantly more likely than products with hybrid internal or internal contracts to have no policies to support integration practices. The majority of hybrid internal products had two policies, while the majority of internal products had one policy supporting integration.

Medical home activities

About three quarters of products reported a formal program to encourage practices to become medical homes, although this was significantly less prevalent among products with external specialty contracts (Table 2). Those products with formal programs reported a wide range of policies to encourage medical homes. Over 60% of products with a formal program to encourage medical homes reported paying a per member per month management fee, other financial incentives, or technical assistance with meeting the criteria for a medical home. About 30% of these products paid an enhanced visit fee or used nonfinancial incentives to encourage medical homes. The prevalence of these activities varied significantly by contracting arrangement, with patterns varying depending on the specific activity. It is notable that a third of respondents reported not knowing the policies to encourage medical homes, with the products with internal arrangements being the most likely not to report their specific policies. The criteria used to define medical home were most often defined by the National Committee on Quality Assurance (NCQA), with 89% of products with a formal program encouraging medical homes reporting this. Nearly all products with a formal medical home program encouraged inclusion of mental health and/or substance abuse in the medical home.

Table 2.

Medical Home Activities, 2010

| Contracting Arrangements | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Specialty External | Hybrid Internal | Internal | |||||

| % | SE | % | SE | % | SE | % | SE | |

| N | 8,427 | 1,219 | 5,899 | 1,278 | ||||

| Health plan has formal program to encourage practices to become medical homes | ||||||||

| Yes | 77.2 | 1.7 | 34.5 a,b | 8.4 | 82.0 a | 1.8 | 80.7 b | 2.5 |

| No | 20.1 | 1.6 | 36.7 | 7.1 | 18.0 | 1.8 | 19.3 | 2.5 |

| Don’t know | 2.7 | 1.0 | 28.5 a,b | 8.7 | 0.0 a | 0.0 | 0.0 b | 0.0 |

| If yes, policies to encourage medical homes: | ||||||||

| Per-member, per-month fee | 61.6 | 1.6 | 39.0 | 15.2 | 69.6 c | 1.5 | 26.7 c | 7.1 |

| Enhanced visit fee | 29.6 | 1.7 | 47.4 | 14.4 | 31.2 c | 1.6 | 16.9 c | 3.8 |

| Other financial incentives | 60.6 | 2.2 | 24.3 a | 10.2 | 69.6 a,c | 1.5 | 23.4 c | 8.8 |

| Non-financial incentives | 30.1 | 2.0 | 47.4 | 14.4 | 31.2 | 1.6 | 19.8 | 8.8 |

| Technical assistance | 62.8 | 2.0 | 74.3 b | 9.1 | 69.6 c | 1.5 | 24.6 b,c | 8.7 |

| Don’t know | 33.7 | 2.0 | 7.6 a,b | 3.2 | 30.4 a,c | 1.5 | 59.0 b,c | 8.8 |

| If yes, criteria used to define “medical home:” | ||||||||

| NCQA | 89.0 | 2.0 | 89.9 a,b | 3.9 | 100.0 a,c | 0.0 | 31.7 b,c | 8.7 |

| Self-developed | 2.1 | 1.0 | 3.6 | 2.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 12.9 | 6.4 |

| Other | 1.8 | 0.8 | 26.1 | 14.4 | 0.0 c | 0.0 | 3.5 c | 1.0 |

| Don’t know | 9.2 | 1.9 | 1.2 b | 0.6 | 0.0 c | 0.0 | 59.4 b,c | 8.7 |

| If yes, health plan formally encourages inclusion of MH and/or SA in the medical home | ||||||||

| Yes | 98.5 | 0.8 | 74.5 | 14.5 | 100.0c | 0.0 | 97.9c | 0.5 |

N represents weighted total number of products

Pairs that share a superscript letter within row are significantly different (P<0.05)

Percentages are based on reported data with missing data excluded. 7% missing data for formal program to encourage medical home. No missing data for other variables.

Do health plans engage in activities related to clinical integration by directly providing services to coordinate behavioral health and general medical care?

Health plans can also support PCPs’ provision of behavioral health services by directly offering a variety of services at the health plan level (Table 3) including case management, interventionists, and consultation. Case management provided by the health plan was the most commonly reported of the three health plan services included on the survey (94.3% of all products). Hybrid internal products had significantly higher prevalence of plan-provided case management compared to both other types of products. Behavioral health interventionists were provided by 35.1% of products. This practice was significantly more common among hybrid internal products than for products with internal behavioral health arrangements. Behavioral health consultation for PCPs was offered by 42.9% of all products. Prevalence of consultation services was significantly higher for hybrid internal products than for internal products.

Only 16.1% of products provided case management, interventionists, and consultation. A significantly higher proportion of specialty external products (40.5%) provided all three services, while the majority of hybrid internal products provided two services, and the vast majority of internal products provided one. Prevalence of providing no services was significantly higher for internal products than other product types.

How do health plans support delivery of evidence-based practices for behavioral health conditions in primary care?

To further hone in on the role of health plans in supporting integration, we asked specifically about how health plans work to encourage primary care practices to delivery three evidence-based practices for substance use. Most products (69.1%) reimbursed for screening and brief intervention conducted in primary care (Table 4). Products with internal behavioral health arrangements were by far the most likely to do this (91.0% compared to 42.2% of products with specialty external contracts and 68.1% of products with hybrid internal arrangements). Nearly all products encouraged screening and brief intervention for alcohol problems. Among products that did encourage this, virtually all provided guidelines. About half of products that encouraged screening and brief intervention did so through financial incentives. About 40% of products that encouraged the practice gave feedback to PCPs. Products with specialty external contracts were significantly less likely than other products to use financial incentives or give provider feedback. Very few products overall offered training or recognition programs, but there were differences by contracting arrangement. Training was significantly more common among specialty external and internal products, compared to products with hybrid internal arrangements. Almost one quarter of products with internal behavioral health arrangements offered recognition programs, while no products in the other categories did so.

Table 4.

Health plan support for substance use screening and brief intervention, 2010

| Contracting Arrangements | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Specialty External | Hybrid Internal | Internal | |||||

| % | SE | % | SE | % | SE | % | SE | |

| N | 8,427 | 1,219 | 5,899 | 1,278 | ||||

| Plan reimburses for substance use screening and brief intervention | ||||||||

| Yes | 69.1 | 1.6 | 42.2 a,b | 8.9 | 68.1 a,c | 1.5 | 91.0 b,c | 2.1 |

| No | 26.1 | 1.3 | 8.2 | 2.6 | 31.2 | 1.5 | 6.0 | 1.5 |

| Don’t know | 4.8 | 1.2 | 49.6 a,b | 9.3 | 0.0 a,c | 0.0 | 3.0 b,c | 1.3 |

| Plan encourages screening and brief intervention for alcohol problems | ||||||||

| Yes | 95.0 | 0.8 | 90.1 | 3.6 | 97.8 c | 0.7 | 87.2 c | 2.6 |

| No | 3.9 | 0.7 | 1.7 | 0.7 | 2.2 | 0.7 | 12.8 | 2.6 |

| Don’t know | 1.1 | 0.4 | 8.2 a,b | 3.4 | 0.0 a | 0.0 | 0.0 b | 0.0 |

| If yes, encouraged through: | ||||||||

| Feedback to providers | 39.4 | 1.9 | 9.1 a,b | 5.1 | 42.3 a | 2.0 | 39.6 b | 8.5 |

| Provision of guidelines | 96.0 | 1.1 | 55.4 a,b | 10.5 | 100.0 a,c | 0.0 | 95.4 b,c | 1.8 |

| Financial incentives | 49.8 | 1.9 | 11.8 a,b | 7.7 | 51.7 a | 1.2 | 60.5 b | 8.4 |

| Recognition programs | 3.3 | 1.2 | 0.0 b | 0.0 | 0.0 c | 0.0 | 23.4 b,c | 7.7 |

N represents weighted total number of products

Pairs that share a superscript letter within row are significantly different (P<0.05); “No” responses not tested.

Index variable of the following SBI supports: (1) reimburse, (2) encourage, (3) encouraged through feedback, (4) encouraged through training, (5) encouraged through financial incentives, and (6) encouraged through recognition programs. Excludes provision of guidelines due to high frequency of products that do this.

Percentages are based on reported data with missing data excluded. Missing data are 9% for substance use screening and brief intervention reimbursement, 2% for screening and brief intervention encouragement, and 6% for methods of encouragement.

Over 90% of all products reimbursed for medication management provided by PCPs for mental health and substance use problems (Table 5). This was universal in products with hybrid internal arrangements. About half (52.4%) of products encouraged pharmacotherapy for alcohol dependence. This was most common among internal products (75.1%). Among products encouraging pharmacotherapy for alcohol dependence, nearly all provided guidelines and most (81.9%) offered feedback to providers. Hybrid internal products were significantly more likely than specialty external and internal plans to give feedback to providers: 100% of hybrid internal products gave feedback while only 24.1% of specialty external and 34.7% of internal products did. Overall, 42.1% offered training, but internal products were significantly less likely than other products to do so. Financial incentives were offered by half of products overall, but no specialty external products did so. Offering recognition programs was rare.

Table 5.

Health plan support for medication management for MH/SUD conditions in primary care, 2010

| Contracting Arrangements | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Specialty External | Hybrid Internal | Internal | |||||

| % | SE | % | SE | % | SE | % | SE | |

| N | 8,427 | 1,219 | 5,899 | 1,278 | ||||

| Plan reimburses for medication management for MH/SUD problems provided by PCP | ||||||||

| Yes | 93.8 | 1.2 | 61.1 a | 9.7 | 100.0 a,c | 0.0 | 82.6 c | 2.1 |

| No | 2.9 | 0.5 | 2.3 | 2.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 16.2 | 2.1 |

| Don’t know | 3.4 | 1.1 | 36.6 a,b | 9.5 | 0.0 a | 0.0 | 1.3 b | 1.1 |

| Plan encourages pharmacotherapy for alcohol dependence in primary care | ||||||||

| Yes | 52.4 | 1.5 | 29.8 a,b | 7.5 | 50.5 a,c | 1.2 | 75.1 b,c | 4.5 |

| No | 43.4 | 1.6 | 35.7 | 8.5 | 49.5 | 1.2 | 16.6 | 3.3 |

| Don’t know | 4.2 | 1.1 | 34.5 a,b | 9.7 | 0.0 a,c | 0.0 | 8.3 b,c | 2.4 |

| If yes, encouraged through: | ||||||||

| Feedback to providers | 81.9 | 2.9 | 24.1 a | 11.0 | 100.0 a,c | 0.0 | 34.7 c | 9.9 |

| Provision of guidelines | 98.8 | 0.6 | 81.6 | 10.6 | 100.0 c | 0.0 | 98.4 c | 0.6 |

| Financial incentives | 50.0 | 2.6 | 0.0 a,b | 0.0 | 50.7 a | 2.3 | 59.8 b | 9.6 |

| Recognition programs | 1.8 | 1.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 8.4 | 6.5 |

| Plan encourages pharmacotherapy for opiate dependence in primary care | ||||||||

| Yes | 78.7 | 1.7 | 41.8 a,b | 9.5 | 82.0 a | 1.8 | 83.4 b | 3.3 |

| No | 18.4 | 1.6 | 22.8 | 6.7 | 18.0 | 1.8 | 16.6 | 3.3 |

| Don’t know | 3.0 | 1.0 | 35.5 a,b | 9.9 | 0.0 a | 0.0 | 0.0 b | 0.0 |

| If yes, encouraged through: | ||||||||

| Feedback to providers | 56.5 | 2.0 | 18.4 a | 9.0 | 61.2 a,c | 1.3 | 41.9 c | 8.7 |

| Provision of guidelines | 99.2 | 0.4 | 88.9 | 8.2 | 100.0 c | 0.0 | 97.9 c | 0.7 |

| Financial incentives | 36.2 | 2.2 | 26.0 a | 13.9 | 31.2 c | 1.6 | 63.8 a,c | 8.9 |

| Recognition programs | 2.8 | 1.1 | 0.0 a | 0.0 | 0.0 c | 0.0 | 17.6 a,c | 6.4 |

N represents weighted total number of products

Pairs that share a superscript letter within row are significantly different (P<0.05)

Percentages are based on reported data with missing data excluded. Missing data range between 8% and 9% for all variables except encouragement method (i.e. “if yes…”) variables, for which there are no missing data.

Plan encouragement of pharmacotherapy for opiate dependence was more common, reported by 78.7% of all products. This was significantly higher among hybrid internal and internal products compared to specialty external products. Among products that encouraged pharmacotherapy for opiate dependence, nearly all provided guidelines. Over half (56.5%) gave feedback to providers and about a third offered training or financial incentives. Compared to other product types, hybrid internal products were significantly more likely to give feedback to providers, specialty external products were significantly more likely to offer training, and internal products were significantly more likely to offer financial incentives. Nearly one fifth (17.6%) of internal products offered recognition programs.

Discussion

Delivery of clinically integrated care requires systemic changes by both health plans and providers in order to achieve financial, structural and clinical integration. A number of barriers to delivery of integrated care21 have been overcome through the federal parity law and the ACA including lack of coverage for mental health and substance use disorders and differential cost-sharing between behavioral health and general medical care. Health plan contracting arrangements and payment policies remain key to supporting a move toward more integrated care.21

Health plan payment policies have been identified as a significant barrier to effectively integrating care because collaboration among providers is often not reimbursed and because health plan contracting arrangements may separate the financial risk for and management of behavioral health and general medical services.16,22,23 When plans contract out behavioral health care, there may be less incentive for the health plan to support delivery of integrated care because separate organizations--the health plan and the MBHO--are at risk for medical and behavioral health costs. Health plans that see value in more integrated care but are hampered by challenges in changing provider payment systems may choose to coordinate care themselves or to reimburse providers on a fee-for-service basis for coordination.

Health plans have multiple levers to choose from in supporting care across the integration continuum including providing information to providers, offering care coordination services themselves, incentivizing specific practices, and modifying payment systems. Health plans alert primary care practices to the importance of integrating care and addressing behavioral health conditions by attaching financial incentives to specific activities. They may encourage coordination through fee-for-service reimbursement of specific tasks or through provision of guidelines. Plans may further support integration efforts by incentivizing care coordination. In this way plans are putting additional financial support behind the encouragement. Finally, plans may encourage practice transformation by using alternative payment models, which may motivate primary care providers to deliver care that is more integrated.

The findings from this study suggest few health plans have payment policies that support the more limited approach of basic integration such as paying for consultations between PCPs and behavioral health specialists. More plans support reimbursement of case management, which is necessary for delivery of partially and fully integrated care.24 Health plans are most supportive of care further along the integration spectrum as evidenced by polices to reimburse for behavioral health providers co-located in primary care practices and to provide increased reimbursement for care delivered in integrated settings and supporting medical homes. These findings suggest health plan payment policies are more focused on supporting fully integrated care rather than making changes to support basic integration, for example, by allowing providers to bill for conversations with specialists.

Another way for health plans to improve integration is to directly provide services to facilitate coordination between behavioral health specialists and primary care providers. This study found extensive use of health plan provided case management and substantial use of health plan provided consultations and interventionists to coordinate behavioral health and primary care. This may be because health plans may have more resources than providers to initiate care coordination programs. Depending on how these programs work and where the case managers and interventionists are located, these initiatives may improve coordination or may result in partially integrated care if these behavioral health providers are located in the primary care practice and work in consultation with primary care. However, when health plans provide their own case management and interventionist services, there may be concern about the incentive to focus these services on limiting utilization. These arrangements are in need of further study.

Health plan’s organizational structures may affect their efforts to support integration.21 The number of financing policies, health plan provided services and supports of screening and brief intervention that products reported using varied by contracting arrangement. Internal products were more likely to have none or few financing policies or health plan provided services to support the integration continuum compared to specialty external and hybrid internal products. Internal products may have fewer reimbursement policies and health plan provided services because they have an alternative payment arrangement that supports integration already (e.g., salaried providers vs. fee-for-service). Specialty external products, in contrast, were less likely to have policies supporting screening and brief intervention compared to other product types. Since specialty external products contract out for delivery and management of behavioral health services it is possible that the survey respondent was less familiar with the specific strategies and policies addressed in the survey. The higher proportion of ‘don’t know’ responses among specialty external products provides some support for this conclusion.

This study did not identify extensive use of health plan payment policies that support integration. However, as health plans move from fee-for-service payment to alternative payment arrangements, providers’ incentives for delivering clinically integrated care will increase. Alternative payments arrangements such as global payments and accountable care models are supportive of clinically integrated care because health plans no longer pay providers piece-meal, based on individual services, but instead pay a fixed amount per patient. This shift in payment policies has the potential to result in important delivery system changes toward more clinically integrated care and will be important to track.

Financial integration has the potential to result in important delivery system changes toward more clinically integrated care and will be important to track. While delivery of integrated behavioral health and primary care has been shown to improve outcomes, challenges remain even in an integrated system. For example, a study following implementation of a chronic care management system in primary care found low uptake of pharmacotherapy for substance use.25 Our findings indicate plans support delivery of mental health and substance use pharmacotherapy through training and financial incentives. It may be helpful for health plans to expand these programs to try to increase SUD pharmacotherapy.

This study has some limitations. Primary care practices work with multiple health plans which have varying levels of market share and therefore carry more or less weight in the practices. Findings are based on self-reported information from health plan executives; the policies health plans report may or may not be communicated to providers and it is not known whether primary care practices are aware of these health plan policies and services. It is also not known whether primary care or multispecialty practices that include primary care are implementing integration approaches, regardless of health plan encouragement. Despite these limitations, this nationally representative survey provides a general indication of health plan support for integrated behavioral health care.

Delivery of integrated care requires systemic changes and health plans are key players because of their role in providing financial integration. Financial integration is necessary to achieve clinical integration. The findings suggest plans are supportive of a move toward integration and some plans put financial resources behind this support. Primary care practices that are interested in delivering care that is more integrated may benefit from financial and technical support offered by health plans. As implementation of integrated care continues, more research of the impact on cost and quality of care will be needed.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by grant R01AA010869 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism and grants R01DA029316 and P30DA035772 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Preliminary versions of these data were presented at the Addiction Health Services Research Conference in October 2014, Boston, MA; the American Public Health Association Annual Meeting in November 2013, Boston, MA; the AcademyHealth Annual Research Meeting in June 2012, Orlando, FL and the Research Society on Alcoholism Scientific Meeting in June 2012, San Francisco, CA. The authors acknowledge the contributions of Pat Nemeth, Frank Potter, Ph.D., and staff at Mathematica Policy Research, Inc., for survey design, statistical consultation, and data collection; Grant Ritter, Ph.D. for statistical consultation, and Galina Zolutusky, M.S., for statistical programming.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Butler M, Kane RL, McAlpine D, et al. Integration of mental health/substance abuse and primary care. Nov, 2008. AHRQ Evidence Reports/Technology Assessments; #173. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chi FW, Parthasarathy S, Mertens JR, Weisner CM. Continuing care and long-term substance use outcomes in managed care: early evidence for a primary care-based model. Psychiatric Services. 2011;62(10):1194–1200. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.62.10.1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gerrity M. Evolving Models of Behavioral Health Integration: Evidence Update 2010–2015. Milbank Memorial Fund; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim TW, Saitz R, Cheng DM, Winter MR, Witas J, Samet JH. Effect of quality chronic disease management for alcohol and drug dependence on addiction outcomes. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2012;43:389–396. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oslin D, Lynch K, Maisto S, et al. A Randomized Clinical Trial of Alcohol Care Management Delivered in Department of Veterans Affairs Primary Care Clinics Versus Specialty Addiction Treatment. J GEN INTERN MED. 2014;29(1):162–168. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2625-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saitz R, Horton NJ, Larson MJ, Winter M, Samet JH. Primary medical care and reductions in addiction severity: a prospective cohort study. Addiction. 2005;100:70–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.00916.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weisner C, Mertens J, Parthasarathy S, Moore C, Lu Y. Integrating Primary Medical Care With Addiction Treatment. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2001;286(14):1715–1723. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.14.1715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Woltmann E, Grogan-Kaylor A, Perron B, Georges H, Kilbourne AM, Bauer MS. Comparative Effectiveness of Collaborative Chronic Care Models for Mental Health Conditions Across Primary, Specialty, and Behavioral Health Care Settings: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2012;169(8):790–804. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.11111616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Steenbergen-Weijenburg KM, van der Feltz-Cornelis CM, Horn EK, et al. Cost-effectiveness of collaborative care for the treatment of major depressive disorder in primary care. A systematic review. BMC Health Services Research. 2010;10(1):19. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grochtdreis T, Brettschneider C, Wegener A, et al. Cost-Effectiveness of Collaborative Care for the Treatment of Depressive Disorders in Primary Care: A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(5):e0123078. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0123078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parthasarathy S, Mertens J, Moore C, Weisner C. Utilization and cost impact of integrating substance abuse treatment and primary care. Medical Care. 2003;41(3):357–367. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000053018.20700.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Melek SP, Norris DT, Paulus J. Economic Impact of Integrated Medical-Behavioral Healthcare: Implications for Psychiatry. Milliman American Psychiatric Association Report; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alakeson V, Frank RG. Health care reform and mental health care delivery. Psychiatric Services. 2010;61(11):1063. doi: 10.1176/ps.2010.61.11.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Collins C, Hewson DL, Munger R, Wade T. Evolving Models of Behavioral Health Integration in Primary Care. New York, NY: Milbank Memorial Fund; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beronio K, Glied S, Frank R. How the Affordable Care Act and Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act Greatly Expand Coverage of Behavioral Health Care. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research. 2014;41(4):410–428. doi: 10.1007/s11414-014-9412-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lewis VA, Colla CH, Tierney K, Van Citters AD, Fisher ES, Meara E. Few ACOs Pursue Innovative Models That Integrate Care For Mental Illness And Substance Abuse With Primary Care. Health Affair. 2014;33(10):1808–1816. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katon W, Russo J, Lin EHB, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a Multicondition Collaborative Care Intervention A Randomized Controlled Trial. Arch Gen Psychiat. 2012;69(5):506–514. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.1548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kirchner JE, Ritchie MJ, Pitcock JA, Parker LE, Curran GM, Fortney JC. Outcomes of a Partnered Facilitation Strategy to Implement Primary Care-Mental Health. J GEN INTERN MED. 2014;29:S904–S912. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-3027-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mauer B. Finance, Policy and Integration of Services. Rockville, MD: National Council for Community Behavioral Healthcare; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Horgan CM, Stewart MT, Reif S, et al. Behavioral Health Services in the Changing Landscape of Private Health Plans. Psychiatr Serv. 2016;67(6):622–629. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201500235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mauer B, Druss B. Mind and Body Reunited: Improving Care at the Behavioral and Primary Healthcare Interface. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research. 2010;37(4):529–542. doi: 10.1007/s11414-009-9176-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Horvitz-Lennon M, Kilbourne AM, Pincus HA. From silos to bridges: meeting the general health care needs of adults with severe mental illnesses. Health Affairs (Millwood) 2006;25(3):659–669. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.25.3.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kessler R, Stafford D, Messier R. The problem of integrating behavioral health in the medical home and the questions it leads to. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings. 2009;16(1):4–12. doi: 10.1007/s10880-009-9146-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bower P, Gilbody S, Richards D, Fletcher J, Sutton A. Collaborative care for depression in primary care. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;189(6):484–493. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.023655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Park TW, Samet JH, Cheng DM, et al. The Prescription of Addiction Medications After Implementation of Chronic Care Management for Substance Dependence in Primary Care. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2015;52:17–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2014.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]