Abstract

Arctic tundra landscapes are composed of a complex mosaic of patterned ground features, varying in soil moisture, vegetation composition, and surface hydrology over small spatial scales (10–100 m). The importance of microtopography and associated geomorphic landforms in influencing ecosystem structure and function is well founded, however, spatial data products describing local to regional scale distribution of patterned ground or polygonal tundra geomorphology are largely unavailable. Thus, our understanding of local impacts on regional scale processes (e.g., carbon dynamics) may be limited. We produced two key spatiotemporal datasets spanning the Arctic Coastal Plain of northern Alaska (~60,000 km2) to evaluate climate-geomorphological controls on arctic tundra productivity change, using (1) a novel 30 m classification of polygonal tundra geomorphology and (2) decadal-trends in surface greenness using the Landsat archive (1999–2014). These datasets can be easily integrated and adapted in an array of local to regional applications such as (1) upscaling plot-level measurements (e.g., carbon/energy fluxes), (2) mapping of soils, vegetation, or permafrost, and/or (3) initializing ecosystem biogeochemistry, hydrology, and/or habitat modeling.

Subject terms: Ecosystem ecology, Climate-change ecology

Background & Summary

Arctic polygonal tundra landscapes are highly heterogeneous, disproportionately distributed across mesotopographic gradients, varying in surficial geology, ground ice content, and soil thermal regimes1,2. The high density of ice wedges present in this low relief landscape facilitates subtle variations (~0.5 m) in surface microtopography, markedly influencing hydrology3,4, biogeochemistry5–10, and vegetation structure11,12. Fine-scale differences in microtopography have been shown to control a variety of key ecosystem attributes and processes that influence ecosystem function, such as snow distribution and depth13, surface and subsurface hydrology13,14, vegetation composition2,11,12, carbon dioxide and methane fluxes5,6,15,16, soil carbon and nitrogen content17–19, and an array of soil characteristics18,20. Despite the prominent control of microtopography and associated geomorphology on ecosystem function, land cover data products available to represent landforms across the Pan-Arctic are strikingly limited21. The relative absence of these key geospatial datasets characterizing permafrost lowlands, may severely limit our ability to understand local scale controls on regional to global scale patterns and processes21.

Datasets presented here were developed to investigate the potential local to regional controls on past and future trajectories of arctic tundra vegetation productivity22, inferred from spatiotemporal patterns of change in the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI). We present two geospatial data products, (1) a 30 m resolution tundra geomorphology map, and (2) a decadal scale NDVI trend map (1999–2014), developed to represent the landform heterogeneity and associated productivity change across the Arctic Coastal Plain (ACP) of northern Alaska (~60,000 km2). We validated the tundra geomorphology map using 1000 reference sites, and evaluated the sensor bias used to develop the NDVI trend map. Produced geospatial datasets will be useful for an array of applications, some of which may include the (1) upscaling of plot-level measurements (e.g., carbon and energy fluxes), (2) mapping of soils, vegetation, or permafrost, and/or (3) initializing ecosystem biogeochemistry, hydrology, and/or habitat modeling.

Methods

Polygonal tundra geomorphology mapping

We focused this mapping initiative on the Arctic Coastal tundra region of northern Alaska, which stretches from the western coast along the Chukchi sea to the Beaufort coastal plains at the Alaskan-Canadian border (latitude: 68–71˚ N; longitude: 140–167˚ W). Two ecological landscape units (~60,000 km2), the Arctic peaty lowlands and the Arctic sandy lowlands were used to define the spatial extent of the ACP23. The region is dominated by continuous permafrost several hundred meters thick24. Permafrost ground ice content ranges from low in sandy lowlands to very high in peaty lowlands23,25, while the maximum active layer depth ranges from 20–120 cm26. These two arctic tundra regions (i.e., sandy and peaty lowlands) were specifically targeted in this analysis, due to their geomorphologic similarity to ~1.9 million km2 of tundra across the Pan-Arctic27. The tundra mapping approach described here will be useful for the development of comparable products across northern latitudes. Refer to the primary research article22, for detailed site descriptions.

Image processing

Twelve cloud free Landsat 8 satellite images were acquired during the summers of 2013 and 2014, used in the tundra geomorphology classification (Table 1). All Landsat data products were downloaded from the United States Geological Survey (USGS) earth explorer web-based platform (https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov). We used only the 9 spectral bands provided by the Operational Land Imager (OLI) instrument for mapping, while ignoring the 2 additional Thermal Infrared Sensor (TIRS) bands due to defective optics in the infrared sensor28. Landsat 8 OLI spectral bands include (1) coastal/aerosol (Ultra blue), (2) blue, (3) green, (4) red, (5) near infrared (NIR), (6) shortwave infrared 1 (SWIR1), (7) shortwave infrared 2 (SWIR2), (8) panchromatic, and (9) cirrus. Prior to image mosaicking, reflectance values were normalized across satellite scenes, by calculating top-of-atmosphere reflectance29, which minimized the radiometric difference between images associated with varying atmospheric conditions, acquisition dates, and solar zenith angles29, while the Landsat Surface Reflectance Code (LaSRC) was used for atmospheric correction. Images were mosaicked within ArcGISTM 10.4 (ESRI).

Table 1. Mosaicked Landsat scenes used to create the tundra geomorphology map.

| Product ID | Sensor | Satellite | Year* | Month* | Day* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LC80690112013249LGN00 | OLI/TIRS | Landsat 8 | 2013 | Sept. | 5 |

| LC80720112013254LGN00 | OLI/TIRS | Landsat 8 | 2013 | Sept. | 10 |

| LC80740112014191LGN00 | OLI/TIRS | Landsat 8 | 2014 | July | 9 |

| LC80770102013193LGN00 | OLI/TIRS | Landsat 8 | 2013 | July | 11 |

| LC80770112013193LGN00 | OLI/TIRS | Landsat 8 | 2013 | July | 11 |

| LC80790102013191LGN00 | OLI/TIRS | Landsat 8 | 2013 | July | 9 |

| LC80800102014217LGN00 | OLI/TIRS | Landsat 8 | 2014 | Aug. | 4 |

| LC80800112014249LGN00 | OLI/TIRS | Landsat 8 | 2014 | Sept. | 5 |

| LC80820122013244LGN00 | OLI/TIRS | Landsat 8 | 2013 | Aug. | 31 |

| LC80830102014222LGN00 | OLI/TIRS | Landsat 8 | 2014 | Aug. | 9 |

| LC80830112014190LGN00 | OLI/TIRS | Landsat 8 | 2014 | July | 8 |

| LC80840122013194LGN00 | OLI/TIRS | Landsat 8 | 2013 | July | 12 |

*Acquisition date.

Image classification

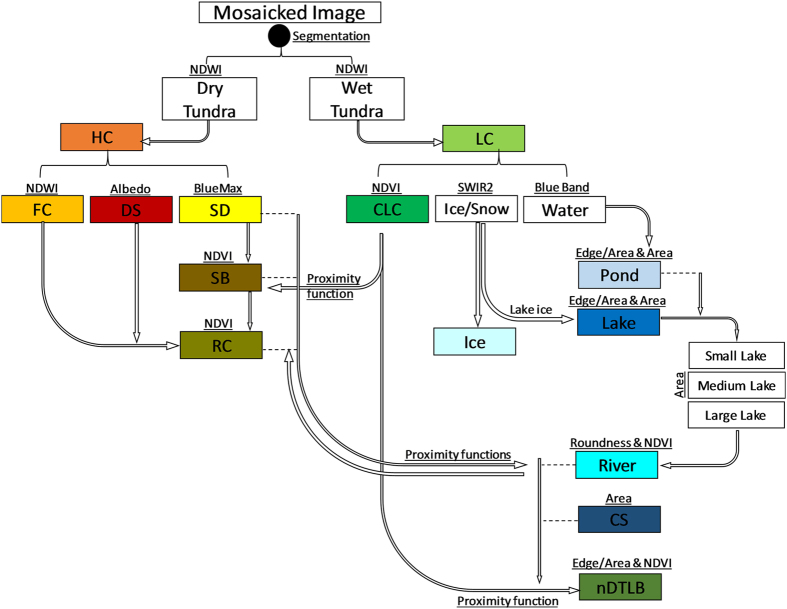

We expand upon geomorphic mapping procedures developed for a subregion of the ACP of northern Alaska on the Barrow Peninsula (1800 km2)5, using a novel automated object based image analysis (OBIA) approach for tundra geomorphic mapping across the ACP (58,691 km2). The OBIA land cover classifier (eCognition™ version 9.1, Trimble) was parameterized using various rules, thresholds, spectral indices, and proximity functions using individual and combined spectral bands, spectral indices, and geometric object shapes/sizes (i.e., perimeter, area, roundness) and corresponding reference data (i.e., field/ground truth points and high resolution aerial/satellite imagery) to differentiate between geomorphic landforms (Fig. 1). Fifteen tundra geomorphic landforms were mapped at 30×30 m spatial resolution (Fig. 2a), including (qualitatively ranked from wet to dry), coastal saline water (CS), lakes (large:>90 ha, medium:≤90 and >20 ha, small:≤20 ha), rivers, ponds, coalescent low-center polygons (CLC), nonpatterned drained thaw lake basins (nDTLB), low-center polygons (LC), sandy barrens (SB), flat-center polygons (FC), riparian corridors (RC), high-center polygons (HC), drained slopes (DS), sand dunes (SD), ice/snow (Ice), and urban. Spectral indices used in image classification included Albedo30, Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI)31 (), Normalized Difference Water Index (NDWI)32 (), and BlueMax (), where MaxDiff refers to the maximum difference between all bands (1-9).

Figure 1. Simplistic schematic representation of the classification procedure used to map polygonal tundra geomorphology on the ACP.

Underlined text represents Band, Area, Function, or Index thresholds used for assigning classes. Proximity functions are used to reclassify image objects based on distance from another geomorphic landform. See ‘Tundra Classification’ section for acronym definitions.

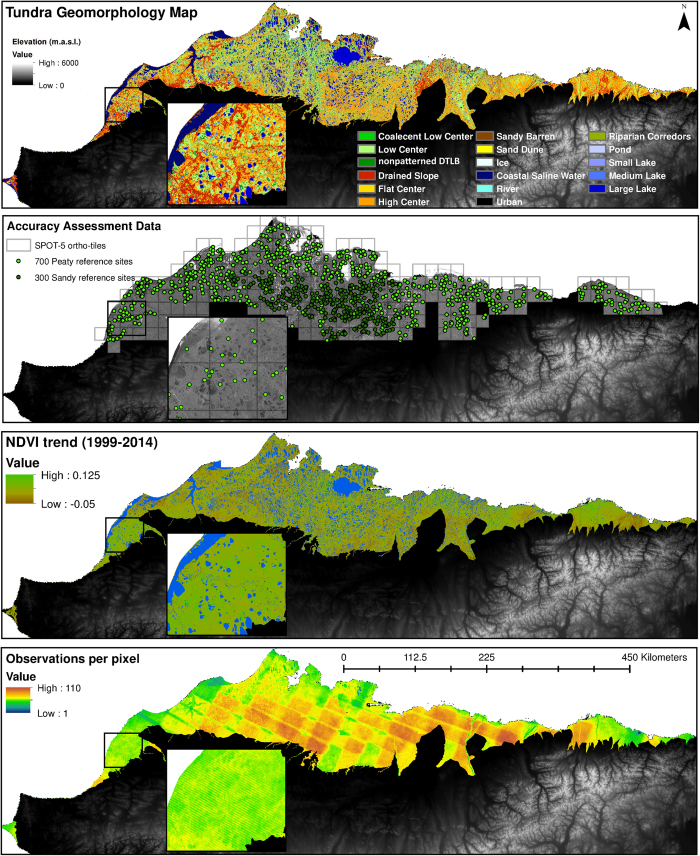

Figure 2. Geospatial datasets representing the heterogeneity in both landform and NDVI across the ACP of northern Alaska.

The tundra geomorphology map (a) was validated with 1000 reference sites (700 and 300 in the Arctic Peaty Lowlands and Arctic Sandy Lowlands, respectively) using 249 SPOT-5 ortho-tiles (b), while the NDVI trend map (c) was developed using between 40 to 110 image observations per 30 m pixel (d).

All pixels within the processed Landsat 8 image mosaic were aggregated into clusters or image ‘objects’ based on similar spectral properties of neighbouring pixels using multiresolution segmentation and spectral difference algorithms. These segmentation algorithms were parameterized to represent object characteristics such as shape, compactness, and spectral similarity. We split all image objects into two broad classes, wet tundra and dry tundra using NDWI thresholds, identified using landform specific field observations5,15. The following classification procedure (Fig. 1, Supplementary File 1), extracts all image objects from wet and dry tundra and reclassifies them into specific geomorphic landforms.

Wet Tundra Classification

We decomposed our classification of wet tundra into three steps, (1) extraction of CLC and nDTLB, (2) open water body differentiation, and (3) rectification of misclassifications. Initially, we differentiated CLC from all wet tundra objects using a low productivity (NDVI) threshold, which was associated with sparse vegetation cover and the presence of open water. Although, both CLC and nDTLB are found in aquatic to wet environments, we differentiated CLC from nDTLB landforms using the characteristically high NDVI values of nDTLB5,15 and morphological features. Due to the rapid formation of nDTLB following lake drainage33, this young geomorphic landform often contains a relatively large non-polygonal surface area34 (i.e., limited effects of ice aggregation and heaving processes associated with microtopographic variability), thus we use a moderate edge to area ratio and high NDVI threshold for nDTLB feature extraction.

All unvegetated open water pixels were extracted using a low-moderate blue band threshold (Fig. 1). A spectral difference segmentation algorithm, was looped 5x to iteratively combine all neighbouring open water objects with similar spectral properties. This object merging process enabled the identification of each spatially isolated water body (i.e., lake, pond, or river), where structural properties such as area, perimeter, or edge (i.e., perimeter) to area ratio can be used to differentiate waterbodies. Therefore, we defined CS, lakes, and ponds using structural properties, area and edge to area ratio. Water bodies were decomposed into CS (>100,000 ha) large lakes (≤ 100,000 > 90 ha), medium lakes (≤ 90 > 20 ha), small lakes (≤ 20 >1 ha), and ponds (≤ 1 ha). The 100,000 ha area threshold was used to define CS to avoid large lake misclassification errors, as Teshekpuk Lake (70.61˚ N, −153.56˚ W), has an area of ~83,000 ha. Due to misclassifications of ponds as lakes, associated with the high interconnectivity between irregularly structured open water objects, we used a low edge to area ratio on lakes, to ensure accurate classification of ponds. Rivers were differentiated from all open water objects using a NDVI threshold and a ‘roundness’ function. Integrating both approaches successfully extracted rivers, as high NDVI thresholds were used to differentiate open water from vegetated aquatic standing water objects, and low roundness values identified the characteristic elongated and meandering structure of rivers. Despite the late summer image acquisition dates used in this classification (Table 1), ice/snow image objects identified using high SWIR2 thresholds, were found in large lakes or adjacent to steep topographic gradients such as river valleys or near a snow fence. All ice/snow objects that occurred on lakes were reclassified as lake area, while the remaining ice/snow was reclassified as Ice.

Although, classification functions developed for wet tundra performed well, the majority of misclassifications were associated with the relatively course spatial resolution object patch size (30 m). To rectify these misclassifications, we used neighborhood or proximity functions to develop relationships between nearby geomorphic landforms using spectral and structural parameters for nDTLB, CLC, pond, and lakes. For example, nDTLB was often misclassified as CLC or pond, occurring near lake perimeters. Because aquatic-wet landforms occurring near lake perimeters are typically represented by nDTLB, having recently formed after partial or complete lake drainage, we reclassified older landforms such as CLC and ponds adjacent to lakes as nDTLBs. All remaining unclassified wet tundra objects that did not meet the criteria for nDTLB, CLC, pond, river, CS, or lakes in wet tundra were classified as LC (i.e., dominant wet geomorphic landform).

Dry Tundra Classification

We differentiated landforms in dry tundra following two steps, (1) threshold identification and extraction of FC and RC, and (2) rectification of misclassifications. A series of reference sites identified from ground based observations and/or oblique aerial photography were used to define NDWI and NDVI thresholds needed to extract FC and RC, respectively. These two geomorphic landforms were difficult to classify due to the similarity in vegetation composition and surface hydrology. However, we were able to differentiate between these two landforms, as FC was slightly higher in surface wetness, associated with the 2 fold difference in trough area relative to HC5. The high variability in NDVI of shrub canopies in RC relative to other landforms, made RC difficult to extract. Nevertheless, because RC typically occurred near riverine environments, we used both a low-moderate NDVI threshold and a proximity function adjacent to rivers to extract RC. Sand and gravel objects were easily extracted using a high BlueMax threshold. All lightly vegetated wet-moist sand and gravel objects were classified as SB using a moderate-high NDVI threshold, whereas drier sand and gravel objects were classified as SD. Due to the use of sand and gravel in the development of urban infrastructure such as roads and buildings, automated procedures initially classified these feature as SD, as they had a similar spectral signature. However, we manually reclassified SD as Urban near native Alaskan villages and oil drilling platforms (i.e., near Prudhoe Bay). Although, we made significant progress with the development of classification procedures for Urban landforms using spectral patterns and geometric structures, we abandoned this development due to the relatively limited area impacted by urban infrastructure across the ACP. Additionally, DS was extracted using a high albedo threshold, as this landform was very dry and often dominated by lichen plant communities, which are highly reflective15. Similar to misclassifications associated with object patch size identified in wet tundra, we found analogous misclassifications of SB near rivers as CLC and ponds. Therefore, we reclassified CLC and pond classes that were adjacent to rivers as SB. All remaining unclassified dry tundra objects not classified as DS, FC, RC, SB, SD, or Urban were classified as HC (i.e., dominant dry geomorphic landform).

Decadal scale NDVI trend analysis

Following the approach of Nitze & Grosse35, the NDVI trend map (Fig. 2d) was computed using all available imagery collected from the Landsat sensors Thematic Mapper (TM), Enhanced Thematic Mapper+ (ETM+), and Observing Land Imager (OLI), acquired between July 1st and August 30th (i.e., peak growing season) of 1999-2014, across the ACP. We excluded imagery preceding 1999 due to the paucity of image acquisition and limited coverage across the ACP. All surface reflectance data used to derive this product were downloaded as radiometrically and geometrically terrain-corrected product from the USGS EROS Science Processing Architecture interface (https://espa.cr.usgs.gov). The ‘FMask’ algorithm36 was used to detect and mask out all non-valid data, such as clouds, shadows, snow/ice, and nodata pixels. For each pixel, linear trends of NDVI were calculated using the non-parametric Theil-Sen linear regression method, which calculates the median of all possible slopes across every point in time37,38. The Theil-Sen regression is robust against outliers and outperforms least-squares regression in remote sensing data39. Each pixel within the NDVI trend map was based on a total of 40-110 Landsat images (Fig. 2c) for the Theil-Sen slope calculation. The final NDVI trend product was spatiotemporally similar to coarser resolution products40,41 identifying heterogeneous patterns of greening and browning across the ACP of northern Alaska.

Data Records

The presented ACP tundra geomorphology map (Data Citation 1), NDVI trend map (Data Citation 2) and all spatial and climate data used in Lara et al.22 are archived at the Scenarios Network of Alaska and Arctic Planning (SNAP) data portal. These spatial data products were clipped to the ACP domain and formatted as geotiff rasters.

Although the tundra geomorphic map was developed using OBIA which clusters spectrally similar nearby pixels into objects, the final map was resampled at the original 30×30 m pixel resolution and presented as a single-band raster (Fig. 2a). The map attribute table includes the following data columns: geomorphic landform (i.e., sand dune, low-center polygon), area (km2), and soil moisture regime (SMR). In addition, a color palette file (.clc) is provided to reproduce map (Fig. 2a). The annotated functions and code used for the classification of tundra landforms within eCognition™ v. 9.1, are made available in the supplementary information. All threshold values were replaced with qualitative ranges (i.e., low, low-moderate, moderate, moderate-high, or high) as reflectance values and image statistics will vary between scenes, thus user specific refinement will be required. Further, it is important to note that the classification procedure developed here has only been evaluated in lowland arctic tundra ecosystems and misclassifications may arise if applied in dissimilar tundra environments. For example, we applied the developed classification procedure to higher elevation drier hillslope tundra, south of the ACP, finding the rate of misclassification to increase, as algorithms/functions were initially developed explicitly for polygonal tundra similar to the ACP of northern Alaska. To include different tundra landforms with different vegetation, hydrology, and soil characteristics, further development will be required.

The NDVI trend map is presented as a four-band raster (Fig. 2d). Band 1 represents the decadal scale rate of change or slope calculated by the Theil-Sen regression. Band 2 represents the intercept or the NDVI data scaled to the year 2014. While, Band 3 and 4 are the upper and lower 95% confidence intervals of the slope of each individual pixel.

Technical Validation

Tundra Geomorphology Map

To validate the tundra geomorphology map, we used an array of oblique aerial/ground based photography and 249 high resolution Satellite Pour l’Observation de la Terre 5 (SPOT-5) orthorectified image tiles covering >80% of the ACP, provided by the Geographic Information Network of Alaska (GINA, gina.alaska.edu). A stratified random sampling of 700 and 300 reference sites in the Arctic peaty lowlands and Arctic sandy lowlands23, respectively (Fig. 2b), were used for the accuracy assessment. At each of the 1000 sites, we manually generated a reference dataset for geomorphic landforms using high resolution products (Table 2, Supplementary Table 2). This process has been used previously5, identifying 95.5% agreement between reference sites (e.g., geomorphology) generated from satellite platforms relative to that observed on the ground.

Table 2. Example of the reference dataset generated to validate the tundra geomorphology map.

| Ecological Landscape | Landform | Latitude | Longitude |

|---|---|---|---|

| The complete (1000 point) reference dataset can be found in the Supplementary Table 2. | |||

| Arctic Peaty Lowland | non-patterned Drained Thaw Lake Basin | 71.236855 | −156.3785131 |

| Arctic Peaty Lowland | High-center polygon | 71.210642 | −156.4676783 |

| Arctic Peaty Lowland | Pond | 71.191358 | −156.3469935 |

| Arctic Peaty Lowland | River | 70.181085 | −147.2617363 |

| Arctic Peaty Lowland | Riparian corridor | 70.165456 | −148.4265964 |

| Arctic Sandy Lowland | Lake | 70.166375 | −154.2431094 |

| Arctic Sandy Lowland | Drained slope | 70.160143 | −153.6316156 |

| Arctic Sandy Lowland | Sand dune | 70.3493 | −152.7590333 |

Overall map accuracy was 75.7% and Cohens Kappa was 0.725 (Table 3), suggesting the strength of agreement between the independent validation (i.e., reference) dataset and classification to be good to very good42,43. Our map had relatively high user and producer accuracies (Table 3), with the exception of FC, which had a producer accuracy of 40.5%. This relatively low producer accuracy was expected as we had difficulties identifying unique spectral and structural characteristics of FC that that differed from HC. This identification challenge was highlighted in the accuracy assessment, as 64% of misclassified FC were classified as HC, similar to other tundra geomorphic classifications5. The relatively low producer accuracies for FC, CLC, and DS are likely associated with the challenge of decomposing a complex continuously evolving geomorphic landscape13,33,44,45 such as the Arctic tundra into discrete landform units. Despite these difficulties, our accuracy assessment suggests the tundra geomorphology map well represented the spatial distribution and heterogeneity of tundra landforms. We present for the first time, a detailed framework for characterizing arctic tundra landforms across the Pan-Arctic.

Table 3. Accuracy assessment represented as a confusion matrix.

|

Reference Sites |

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geomorphic type | SB | SD | RC | DS | HC | FC | LC | nDTLB | CLC | Pond | River | Lake | CS | User accuracy |

| Bolded diagonal values within the matrix represent correctly identified pixels, where User and Producer accuracies are presented on the right vertical axis and bottom horizontal axis. | ||||||||||||||

|

Classification |

||||||||||||||

| SB | 12 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 63% | |||||||||

| SD | 3 | 12 | 2 | 71% | ||||||||||

| RC | 4 | 1 | 80% | |||||||||||

| DS | 50 | 19 | 4 | 69% | ||||||||||

| HC | 35 | 215 | 30 | 22 | 2 | 70% | ||||||||

| FC | 11 | 32 | 3 | 71% | ||||||||||

| LC | 1 | 6 | 34 | 11 | 152 | 5 | 7 | 2 | 70% | |||||

| nDTLB | 3 | 16 | 53 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 70% | |||||||

| CLC | 2 | 2 | 15 | 2 | 71% | |||||||||

| Pond | 18 | 100% | ||||||||||||

| River | 2 | 2 | 2 | 10 | 63% | |||||||||

| Lake | 1 | 1 | 156 | 99% | ||||||||||

| CS | 1 | 28 | 97% | |||||||||||

| Producer accuracy | 71% | 100% | 80% | 55% | 75% | 41% | 77% | 82% | 56% | 100% | 83% | 96% | 100% | 1000 |

| Overall accuracy | 76% | |||||||||||||

| Cohens Kappa | 0.73 |

NDVI Trend Map

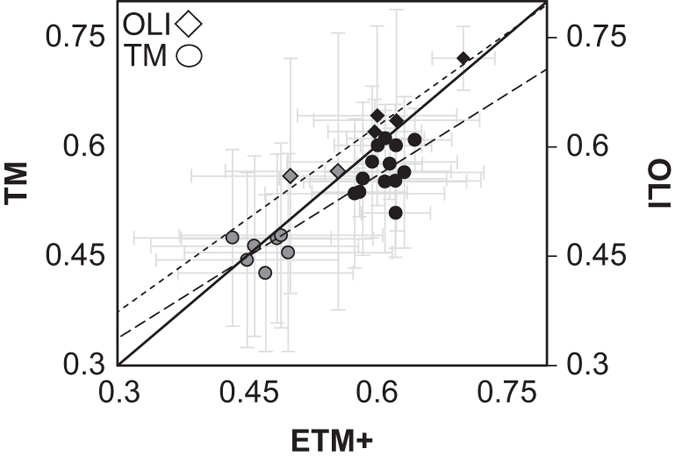

We evaluated the potential sensor bias between TM, ETM+, and OLI, used to derive the NDVI Trend Map by comparing the mean value for each pixel, year, and sensor computed from three different locations in northern Alaska (Fig. 3). Each location was composed of 40,000 pixels (~36 km2). The three centroids of each location are found in the (1) Arctic sandy lowlands of the ACP (longitude: −154.50, latitude: 70.09), (2) foothills of the Brooks Range on the North Slope (longitude: -159.61, latitude: 66.60), and (3) Selawik lowlands in northwestern Alaska (longitude: −152.92, latitude: 69.29). Minor discrepancies were to be expected between sensor platforms as the images were not acquired at the same time or day.

Figure 3. Estimate of NDVI bias between Landsat sensors, represented at three subregions of northern Alaska.

Each point represents the mean (±standard deviation) of NDVI for a single year and subregion. Circles and diamonds represent TM and OLI plotted against ETM+. Grey points represent means from polygonal tundra within the ACP, while black points represent more southerly sites (i.e., foothills of the Brooks Range and Selawik lowlands). Dashed and dotted lines represent trend lines for TM and ETM+ and OLI and ETM+, respectively. The solid black line indicates a 1:1 line.

We identified minor NDVI sensor biases between sensors (Fig. 3), while sensor specific NDVI distributions were consistent. Most of the data used to generate the NDVI trend map was acquired from the ETM+ sensor, as it was available throughout our data acquisition window (i.e., 1999–2014), whereas data from TM and OLI were only available between 2005-2011 and 2013-2014, respectively. Mean sensor bias estimates for TM and OLI across all subregions of Alaska, indicate NDVI to be slightly under- and overestimated relative to ETM+, though the variability was high within each year and subregion (Fig. 3). The minor sensor bias identified here, was similar to that identified across North American high latitude terrestrial ecosystems41. Although, it is likely that sensors are slightly positively (OLI) and negatively (TM) biased with respect to ETM+ across northern Alaska, sensor calibrations appeared to well represent the tundra subregion on the ACP (Fig. 3). NDVI values from both TM and OLI sensors clustered above and below the 1 to 1 line for the subregion on the ACP (Fig. 3), suggesting NDVI data was not positively or negatively skewed between sensors. A slight positive linear NDVI bias (+0.00063) was detected across all sensor data, suggesting a satisfactory agreement between sensors used to compute NDVI on the ACP.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Lara, M. J. et al. Tundra landform and vegetation productivity trend maps for the Arctic Coastal Plain of northern Alaska. Sci. Data 5:180058 doi: 10.1038/sdata.2018.58 (2018).

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

M.J.L. was supported by the Department of Interior’s Arctic Landscape Conservation Cooperative, U.S. Department of Energy Next-Generation Ecosystem Experiments (NGEE-arctic) project, and UI School of Integrative Biology STEM Diversity program. I.N. and G.G. were supported by ERC #338335, HGF ERC-0013, and ESA GlobPermafrost. A.D.M. was supported by a grant from the U.S. Geological Survey’s Alaska Climate Science Center. We thank Philip Martin for initial discussions that lead to the conceptualization of the polygonal tundra map. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interests.

Data Citations

- Lara M. J. 2017. SNAP Data Portal. https://doi.org/10.21429/C9JS8S

- Lara M. J. 2017. SNAP Data Portal. https://doi.org/10.21429/C9F04D

References

- Farquharson L. M., Mann D. H., Grosse G., Jones B. M. & Romanovsky V. E. Spatial distribution of thermokarst terrain in Arctic Alaska. Geomorphology 273, 116–133 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- Walker D. A. Hierarchical subdivision of Arctic tundra based on vegetation response to climate, parent material and topography. Global Change Biology 6, 19–34 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liljedahl A. K., Hinzman L. D. & Schulla J. Ice-Wedge Polygon Type Controls Low-Gradient Watershed-Scale Hydrology. Tenth International Conference on Permafrost, 1-6, (2012).

- Engstrom R., Hope A., Kwon H., Stow D. & Zamolodchikov D. Spatial distribution of near surface soil moisture and its relationship to microtopography in the Alaskan Arctic coastal plain. Nord Hydrol 36, 219–234 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Lara M. J. et al. Polygonal tundra geomorphological change in response to warming alters future CO2 and CH4 flux on the Barrow Peninsula. Global Change Biology 21, 1634–1651 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zona D., Lipson D. A., Zulueta R. C., Oberbauer S. F. & Oechel W. C. Microtopographic controls on ecosystem functioning in the Arctic Coastal Plain. Journal of Geophysical Research-Biogeosciences 116 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Olivas P. C. et al. Effects of Fine-Scale Topography on CO2 Flux Components of Alaskan Coastal Plain Tundra: Response to Contrasting Growing Seasons. Arct Antarct Alp Res 43, 256–266 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Rhew R. C., Teh Y. A. & Abel T. Methyl halide and methane fluxes in the northern Alaskan coastal tundra. Journal of Geophysical Research-Biogeosciences 112, G02009 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Lipson D. A. et al. Water-table height and microtopography control biogeochemical cycling in an Arctic coastal tundra ecosystem. Biogeosciences 9, 577–591 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Newman B. D. et al. Microtopographic and depth controls on active layer chemistry in Arctic polygonal ground. Geophysical Research Letters 42, 1808–1817 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Villarreal S. et al. Tundra vegetation change near Barrow, Alaska (1972-2010). Environ Res Lett 7, 015508 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Brown J., Miller P. C., Tieszen L. L. & Bunnell F. L. An Arctic Ecosystem: the Coastal Tundra at Barrow, Alaska. Dowden, Hutchinson and Ross, Inc. (Stroundsburg, PA), (1980). [Google Scholar]

- Liljedahl A. K. et al. Pan-Arctic ice-wedge degradation in warming permafrost and its influence on tundra hydrology. Nat Geosci 9, 312-+ (2016). [Google Scholar]

- Throckmorton H. M. et al. Active layer hydrology in an arctic tundra ecosystem: quantifying water sources and cycling using water stable isotopes. Hydrol Process 30, 4972–4986 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- Lara M. J. et al. Estimated change in tundra ecosystem function near Barrow, Alaska between 1972 and 2010. Environ Res Lett 7, 015507 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Wainwright H. M. et al. Identifying multiscale zonation and assessing the relative importance of polygon geomorphology on carbon fluxes in an Arctic tundra ecosystem. Journal of Geophysical Research-Biogeosciences 120, 788–808 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Bockheim J. G., Hinkel K. M., Eisner W. R. & Dai X. Y. Carbon pools and accumulation rates in an age-series of soils in drained thaw-lake basins, Arctic Alaska. Soil Sci Soc Am J 68, 697–704 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Bockheim J. G., Everett L. R., Hinkel K. M., Nelson F. E. & Brown J. Soil organic carbon storage and distribution in Arctic Tundra, Barrow, Alaska. Soil Sci Soc Am J 63, 934–940 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Biasi C. et al. Microtopography and plant-cover controls on nitrogen dynamics in hummock tundra ecosystems in Siberia. Arct Antarct Alp Res 37, 435–443 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Johnson K. D. et al. Soil carbon distribution in Alaska in relation to soil-forming factors. Geoderma 167-68, 71–84 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Bartsch A., Hofler A., Kroisleitner C. & Trofaier A. M. Land Cover Mapping in Northern High Latitude Permafrost Regions with Satellite Data: Achievements and Remaining Challenges. Remote Sens-Basel 8, 979 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- Lara M. J., Nitze I., Grosse G., Martin P. & McGuire A. D. Reduced arctic tundra productivity linked with landform and climate change interactions. Sci Rep 8, 2345 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgenson T. M. & Grunblatt J. Landscape-Level Ecological Mapping of Northern Alaska and Field Site Photography (2013).

- Sellmann P. V. & Brown J. Stratigraphy and diagenesis of perennially frozen sediment in the Barrow, Alaska, region. In Permafrost: North American Contribution to the Second International Conference. Washington, D.C.: National Academy of Sciences, 171-181, (1973).

- Jorgenson M. T. et al. Permafrost characteristics of Alaska. Ninth International Conference on Permafrost, 121-122, (2008).

- Nelson F. E. et al. Active-layer thickness in north central Alaska: Systematic sampling, scale, and spatial autocorrelation. Journal of Geophysical Research-Atmospheres 103, 28963–28973 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- Walker D. A. et al. The Circumpolar Arctic vegetation map. J Veg Sci 16, 267–282 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Montanaro M., Gerace A., Lunsford A. & Reuter D. Stray Light Artifacts in Imagery from the Landsat 8 Thermal Infrared Sensor. Remote Sens-Basel 6, 10435–10456 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Chavez P. S. Image-based atmospheric corrections revisited and improved. Photogramm Eng Rem S 62, 1025–1036 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- Liang S. L. Narrowband to broadband conversions of land surface albedo I Algorithms. Remote Sens Environ 76, 213–238 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- Rouse D. A., Haas R. H., Schell J. A. & Deering D. W. Monitoring vegetation systems in the Great Plains with ERTS. Proceedings, Third Earth Resources Technology Satellite-1 Symposium 301–317 (1974). [Google Scholar]

- Gao B. C. NDWI- A normalized difference water index for remote sensing of vegetation liquid water from space. Remote Sens Environ 58, 257–266 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- Jorgenson M. T. & Shur Y. Evolution of lakes and basins in northern Alaska and discussion of the thaw lake cycle. J Geophys Res-Earth 112, F02S17 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Bockheim J. G. & Hinkel K. M. Accumulation of Excess Ground Ice in an Age Sequence of Drained Thermokarst Lake Basins, Arctic Alaska. Permafrost Periglac 23, 231–236 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Nitze I. & Grosse G. Detection of landscape dynamics in the Arctic Lena Delta with temporally dense Landsat time-series stacks. Remote Sens Environ 181, 27–41 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Z., Wang S. X. & Woodcock C. E. Improvement and expansion of the Fmask algorithm: cloud, cloud shadow, and snow detection for Landsats 4-7, 8, and Sentinel 2 images. Remote Sens Environ 159, 269–277 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Sen P. K. Estimates of Regression Coefficient Based on Kendalls Tau. J Am Stat Assoc 63, 1379-& (1968). [Google Scholar]

- Theil H. A rank-invariant method of linear and polynomial regression analysis. Henri Theil's Contributions to Economics and Econometrics 23, 345–381 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes R. & Leblanc S. G. Parametric (modified least squares) and non-parametric (Theil-Sen) linear regressions for predicting biophysical parameters in the presence of measurement errors. Remote Sens Environ 95, 303–316 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt U. S. et al. Recent Declines in Warming and Vegetation Greening Trends over Pan-Arctic Tundra. Remote Sens-Basel 5, 4229–4254 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Ju J. C. & Masek J. G. The vegetation greenness trend in Canada and US Alaska from 1984-2012 Landsat data. Remote Sens Environ 176, 1–16 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- Fleiss J. L., Cohen J. & Everitt B. S. Large sample standard errors of kappa and weighted kappa. Psychological Bulletin 72, 323–327 (1969). [Google Scholar]

- Congalton R. G. A Comparison of Sampling Schemes Used in Generating Error Matrices for Assessing the Accuracy of Maps Generated from Remotely Sensed Data. Photogramm Eng Rem S 54, 593–600 (1988). [Google Scholar]

- Billings W. D. & Peterson K. M. Vegetational Change and Ice-Wedge Polygons through the Thaw-Lake Cycle in Arctic Alaska. Arctic and Alpine Research 12, 413–432 (1980). [Google Scholar]

- Jorgenson M. T., Shur Y. L. & Pullman E. R. Abrupt increase in permafrost degradation in Arctic Alaska. Geophysical Research Letters 33, L02503 (2006). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Lara M. J. 2017. SNAP Data Portal. https://doi.org/10.21429/C9JS8S

- Lara M. J. 2017. SNAP Data Portal. https://doi.org/10.21429/C9F04D