Abstract

Light-harvesting complexes (LHCs) serve a dual role in photosynthesis, depending on the prevailing light conditions. In low light, they ensure photosynthetic efficiency by maximizing the light absorption cross-section and subsequent energy storage. Under excess light conditions, LHCs perform photoprotective quenching functions to prevent harmful chemical species such as triplet chlorophyll and singlet oxygen from forming and damaging the photosynthetic apparatus. In this Minireview, various photoprotective quenching mechanisms that have been identified in different photosynthetic organisms are surveyed and summarized, and implications for improving photosynthetic productivity are briefly discussed.

Keywords: photosynthesis, photosynthetic pigment, carotenoid, chlorophyll, redox regulation, antenna, non-photochemical quenching, xanthophyll cycle

Introduction

Photosynthesis is the process by which photosynthetic organisms transform light energy into chemical energy, which powers essentially all life on Earth (1). Light is absorbed by (bacterio)chlorophylls ((B)Chls),2 bilins, and carotenoids (Cars) in antenna pigment–protein complexes and transferred to the reaction center (RC), the site of primary charge separation (2). Although the overall features of the RC are similar in various organisms, the antenna complexes for light harvesting are extremely diverse and highly dependent on where the organism lives (3, 4). This is because organisms can adapt to the quality and amount of light available to them. However, under conditions that limit RC productivity, such as high light or other stress conditions, light harvesting must be modulated to prevent excess excitation from reaching the RC. The most rapid mechanisms involve the safe dissipation of excess energy as heat, also observed as a reduction in fluorescence, in the process collectively known as non-photochemical quenching (NPQ) (5). NPQ is a general term that includes mechanistically distinct processes that almost certainly have independent evolutionary origins. The molecular mechanisms of antenna fluorescence quenching are still not completely understood, partly because they differ depending on the antenna system and the organism from which they originate (6, 7). Some of these mechanisms overlap in certain organisms, which has evolutionary implications (8). The overall concept of photoprotective quenching is illustrated in Fig. 1. In this Minireview, protective quenching components and mechanisms in various photosynthetic organisms are discussed.

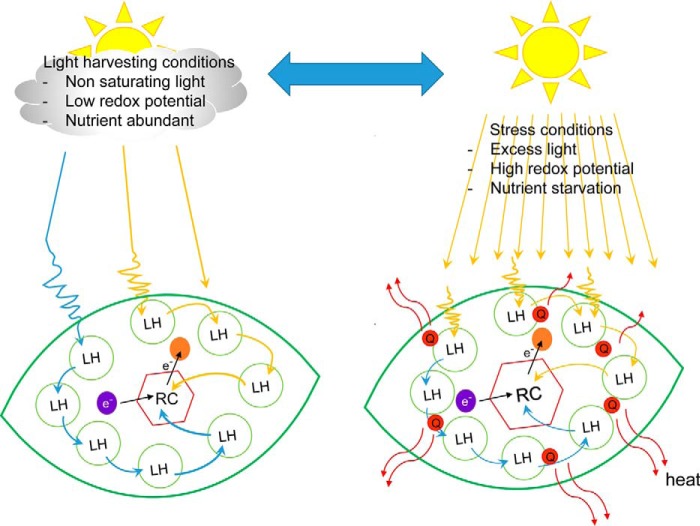

Figure 1.

Generalized diagram of light-harvesting regulation under normal and stress conditions. Quenching centers (Q) are formed in the light-harvesting antenna to dissipate excess excitation safely as heat (red wiggly arrows) during stress conditions. LH, light-harvesting antenna; RC, reaction center; e, electron; violet circle, electron donor; orange circle, electron acceptor.

Green bacteria

The green photosynthetic bacteria are composed of the distantly related green sulfur Chlorobiaceae and green filamentous anoxygenic Chloroflexaceae (9). The green bacteria and an aerobic Acidobacterium, Chloracidobacterium (Cab.) thermophilum (10), have a light-harvesting antenna called the chlorosome. Chlorosomes consist of a large number of aggregated BChls (c, d, or e) enveloped by a lipid monolayer with some proteins and a Bchl a-containing CsmA protein called the baseplate in addition to carotenoids, lipids, and quinones (11, 12). Chlorosomes are remarkable in that the BChl aggregates self-assemble without a protein scaffold. The energy absorbed by the chlorosomes is transferred to the reaction center (a type I iron–sulfur cluster for Chlorobi and Cab. thermophilum; type II for Chloroflexi), which in Chlorobi and Cab. thermophilum is mediated by the molecular wire known as the Fenna-Matthews-Olson (FMO) complex (13). The FMO complex is trimeric in structure, with each monomer enclosing seven BChl a molecules in mostly β-pleated sheet polypeptides and an eighth BChl a located between the monomer interfaces (14, 15).

Under oxidizing conditions, green sulfur bacteria have a redox-regulated fluorescence quenching at the level of the light-harvesting complexes that inhibits energy transfer to the reaction center (9, 16). Quinones mediate this fluorescence quenching (17), which was observed to be much stronger in the chlorosomes from Chlorobaculum tepidum than in Chloroflexus aurantiacus (17, 18), presumably due to the chlorobium quinone that is present only in Chlorobi. It may be that the quenching mechanism is attenuated in Chloroflexi because they are found in oxic habitats, compared with the strictly anaerobic Chlorobi. However, addition of exogenous quinones to whole cells of Cfx. aurantiacus showed specific quenching of BChl c, and the effect is similar to that observed in the green sulfur bacteria (19). Subsequently, the quenching effect of chlorobium quinone was suggested to be associated with the 1′-oxo group in the molecule (20). Chlorosomes from Cab. thermophilum, which has menaquinone-8, also exhibit fluorescence quenching under oxic conditions (21), despite being in aerobic environments.

BChl c radicals have also been detected in oxidized chlorosomes and implicated in the quenching process (22). However, it was suggested that BChl c radicals are possibly artifacts of the extraction process, when considering that the fluorescence quenching effect is larger in the isolated chlorosomes than in whole cells (23). Another proposed mechanism of photoprotection in chlorosomes involves BChl triplet state quenching, because BChl triplets are able to sensitize the formation of harmful singlet oxygen species (12). In this regard, carotenoids are important molecules that either directly quench BChl triplets or scavenge any singlet oxygen produced. In chlorosomes, however, the photoprotection function of carotenoids was found necessary for the baseplate BChl a rather than the BChl aggregates (24). Another mechanism that may protect chlorosomes is the formation of triplet excitons that arise from the interactions among the closely packed BChl pigments (25).

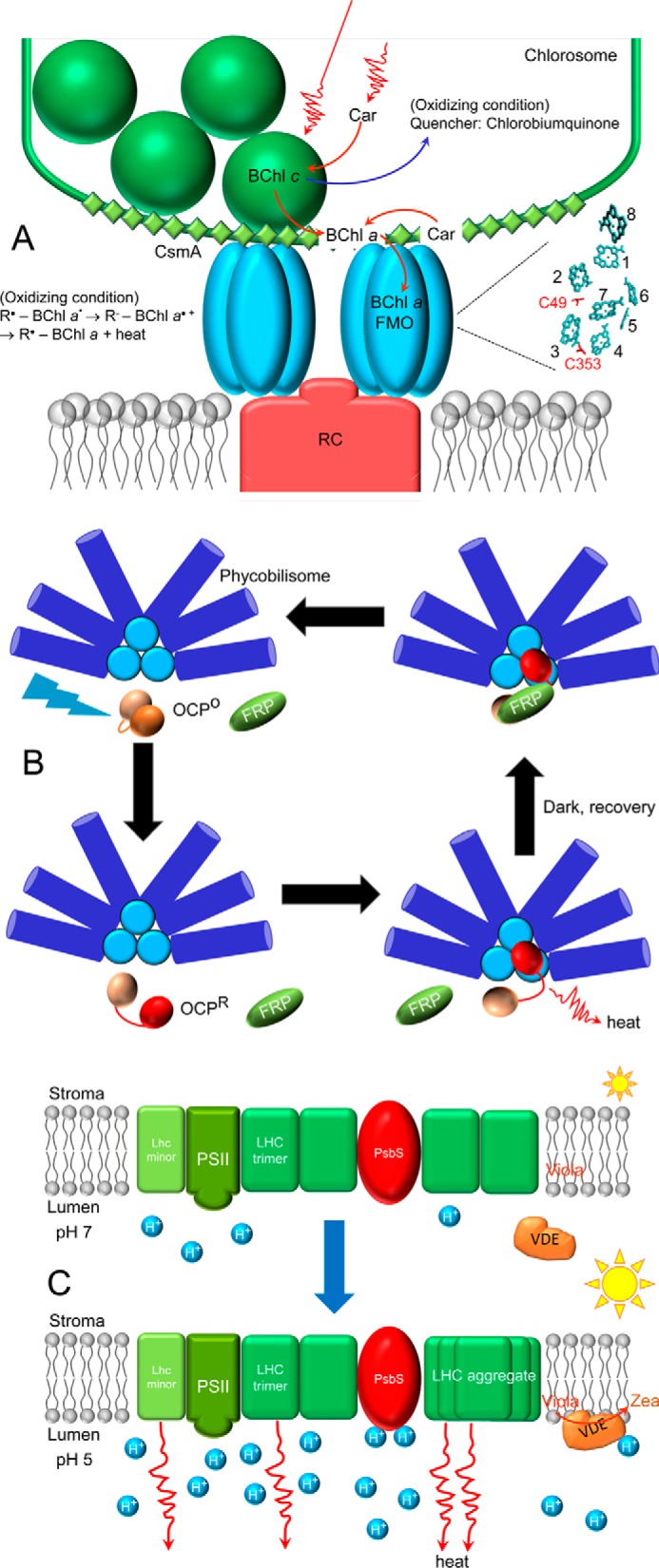

Similar to the chlorosomes, the FMO complex also exhibits redox-dependent quenching, although the mechanism of action is different. Spectroscopic experiments have shown that the fluorescence lifetime of the protein shortens to ∼60 ps under oxidizing conditions as opposed to the ∼2-ns lifetime observed under reducing conditions (26). The quenching mechanism is different from that in the chlorosomes as it is proposed to be mediated by cysteine residues located near the lowest energy BChl a molecules (BChls 2 and 3) (27). The proposed mechanism is such that under oxidizing conditions, the cysteine thiol is converted to a thiyl radical that abstracts an electron from the excited BChl a to safely dissipate excess excitation: R• − BChl a* → R− − BChl a+· → R• − BChl a + heat. These findings point to a simple yet elegant approach of regulating excitation energy in a photosynthetic light-harvesting antenna. Fig. 2A illustrates the quenching mechanisms in green bacteria.

Figure 2.

Schematic illustration of quenching mechanisms in selected organisms. A, quenching in green bacteria located in chlorosomes and FMO complex under oxidizing conditions. For clarity, only the macrocyclic rings (cyan) of the various BChl a molecules of FMO are shown numbered 1–8, with the Cys residues (C49 and C353) involved in the redox-regulated quenching. BChl, bacteriochlorophyll; Car, carotenoid; RC, reaction center. B, cyanobacterial orange carotenoid protein (OCP)-mediated quenching of phycobilisome fluorescence after activation by blue-green light. OCPO, orange form; OCPR, red form; FRP is fluorescence recovery protein. C, components of NPQ in higher plants upon acidification of the lumen, including PsbS protonation, violaxanthin (Viola) to zeaxanthin (Zea) conversion by VDE, and subsequent formation of quenching centers that dissipate excess excitation energy as heat.

Cyanobacteria and red algae

Cyanobacteria are oxygenic prokaryotes that have water-soluble extramembrane light-harvesting antenna complexes called phycobilisomes (PBs). Phycobilisomes are composed of phycobiliproteins that covalently bind linear tetrapyrrole pigments called bilins, as well as linker proteins (28). Phycobilisomes have a core made up of allophycocyanin (APC), from which phycocyanin (PC) rods project. In some organisms, the rods also contain phycoerythrin (PE), in addition to PC.

Blue-green light-induced quenching of PB fluorescence in cyanobacteria is mediated by the orange carotenoid protein (OCP) (29), as shown schematically in Fig. 2B. OCP contains a non-covalently bound ketocarotenoid, which in the inactive orange form (OCPo) traverses both the N- and C-terminal domains (NTD and CTD) (30). Photoactivation converts OCPo into the red form (OCPr), with the protein undergoing substantial conformational changes and domain rearrangements (31–33) that may lead to a ∼12-Å pigment translocation into the NTD (34). The OCPr then binds to the phycobilisome and quenches excitations of the bilins before they are transferred to chlorophylls. The overall process of OCP regulation has been intensely studied (35, 36), although the physical mechanism of excited-state quenching of bilins is still not certain. Recent dynamic crystallography data provide a glimpse into the initial events of OCP photoactivation (37). It is proposed that there is a transient keto-enol shift upon photoactivation that disrupts the interactions between the conjugated carbonyl group of the carotenoid β1 ring and the protein, which in turn drives the separation of the N- and C-terminal domains. Previously, it was suggested that the rotation of the β-ionylidene ring drives the structural rearrangement (38), but what exactly leads to the global structural rearrangement remains to be determined. OCP was shown to burrow into the APC core of the PB, bringing the carotenoid in close proximity to the excited bilin for quenching (39). OCP-PB binding is reversible with OCP detachment from the PB aided by the fluorescence recovery protein (FRP) (40). Although FRP was previously found to bind to the CTD of OCPr, the latest mass spectrometry results suggest that FRP also interacts with the NTD after CTD binding (41) and that facilitates the bridging of the two domains to recover the compact OCPo. Although OCP has been widely studied, there are still unresolved questions, such as the site and the mechanism of quenching by the carotenoid. The site has been narrowed down to the APC core (29, 42) with either APC 660 or 680 as the quenching site (43–45). Several hypotheses have been proposed for the carotenoid-mediated quenching: charge transfer (46, 47) and energy transfer from the APC-excited bilin to Car followed by internal conversion to the ground state (42, 48), yet there is no experimental evidence to confirm the involvement of any of these mechanisms. In addition to PB fluorescence quenching, OCP has also been shown to quench damaging singlet oxygen in the thylakoid membranes under strong orange-red light when OCP is not activated (49).

A non-OCP-related PB quenching was recently reported (50) using single molecule spectroscopy. Results from this study suggest a novel strategy for cyanobacterial photoprotection that is light-controlled. Fluorescence data show that PBs have multiple intrinsic channels in its subunits and that quenching can occur in any of them, although the core is the frequent target. This is a unique mechanism that provides rapid photoprotection before the OCP mechanism is activated.

Other photoprotective mechanisms operating in cyanobacteria involve high-light–inducible (Hli) and iron starvation-inducible (IsiA) proteins. Cyanobacterial Hlips, or small Cab-like proteins, are single helix proteins that bind Chl a, which are ancestors of the LHC superfamily (51). Hlips are not involved in light harvesting but are necessary for cyanobacterial survival under high light illumination and other stress conditions (52–54). In particular, Hlips are suggested to have a photoprotective role related to Chl biosynthesis and PSII assembly (55). Energy dissipation in Hlips occurs via direct energy transfer from the Chl a Qy excited-state to the carotenoid (β-carotene) S1 state based on transient absorption data (56). This study provided the first direct experimental evidence for such a mechanism. Subsequently, transient absorption studies on purified FLAG-tagged chlorophyll synthase (f.ChlG) with high-light–inducible proteins HliD/C also confirmed the Chl a to Car energy transfer at room and cryogenic temperatures (57). Resonance Raman spectroscopy identified two forms of β-carotene in Hlips, one of which has a twisted conformation that lowers its S1 energy and may act as the quencher (58).

During iron starvation conditions, cyanobacteria produce the IsiA protein (59), which forms a ring around photosystem I trimers (60). IsiA is a pigment–protein complex with high sequence similarity to CP43, a core antenna of PSII, containing Chl a and carotenoids (61). IsiA uncoupled to PSI exhibits quenching of Chl a fluorescence, with carotenoids previously identified as energy dissipators via transfer of Chl a Qy to the carotenoid S1 state (62, 63). In these studies, however, no spectral signature from the carotenoid was observed in the transient absorption data but otherwise incorporated in the fitting models, by assuming that the quencher cannot be sufficiently populated due to a slow rate of Car–Chl a transfer. More recently, results from Chen et al. (64) have shown that the quenching mechanism does not involve the carotenoids and is instead regulated through Chl a–protein interactions by cysteine residues in the IsiA protein. This is analogous to the redox-dependent quenching mechanism first observed in the FMO complex (27) from green sulfur bacteria and now appears to be present in an oxygenic photosynthetic organism as well. It remains to be determined how prevalent Cys-regulated quenching mechanisms are in nature.

Red algae have two light-harvesting antennas, phycobilisomes and LHCI complex that are connected to the RCs of PSII and PSI, respectively (65). Red algae do not have OCP, however, and little is known about their photoprotection mechanisms. Decoupling of PE from the PB core was proposed as a strategy in Porphyridium cruentum, according to single molecule fluorescence data (66). State transitions involving PB mobility remain a matter of debate in cyanobacteria (67) but were shown to be important for the mesophilic red algae P. cruentum and Rhodella violacea (68). In the thermophilic red algae (Cyanidium caldarium and Cyanidioschyzon merolae), NPQ is the main mechanism for excess energy dissipation, but it is located in the PSII reaction center and not the antenna (68, 69).

Green algae, moss, and diatoms

In higher plants, NPQ is constitutive, whereas in green algae it is inducible and takes effect after a few hours of high-light exposure or decreased CO2 supply (70, 71). NPQ in eukaryotic algae is regulated by the light-harvesting complex stress-related (LHCSR) protein (72), an ancient member of the LHC family that binds Chls (a and b) and xanthophylls (73). In Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, two types are expressed: constitutive LHCSR1 and high-light–induced LHCSR3 (72, 74). In addition to LHCSR, C. reinhardtii has nine LHCBM (1–9) genes that code for LHCII, each with distinct roles and a different involvement in NPQ (75–77), which will not be detailed here. The VAZ xanthophyll cycle involving the enzymatic conversion of violaxanthin → antheraxanthin → zeaxanthin by violaxanthin de-epoxidase also plays a role in green algae NPQ. However, zeaxanthin-dependent NPQ in green algae is highly variable depending on the organism (78).

A proposed model (70) for NPQ activation in C. reinhardtii begins with light-harvesting complex stress-related 3 expression under high light, followed by association with PSII-LHCII to form the PSII–LHCII–LHCSR3 supercomplex. LHCSR3 protonation occurs upon acidification of the lumen that leads to the formation of the quenching center. The quenching mechanism was proposed to be due to charge transfer from Chl to Car (73).

In a recent study, it was determined that LHCSR3 production is induced by the blue light phototropin receptor (79). Using a mutagenesis approach, the pH-sensing region was localized to the C terminus of LHCSR3, as it is particularly rich in acidic residues that can be protonated (80). More recently, this has been narrowed down to three (Asp-177, Glu-221, and Glu-224) residues (81). Although LHCSR associates with PSII, it can also move to PSI as shown by Allorent et al. (82). After heterologous overexpression in Nicotiana sp., LHCSR1 was shown to bind Chl a only and that it is involved in NPQ (83). In vivo studies in C. reinhardtii were conducted using a “minimal NPQ cell” lacking PSI and PSII to demonstrate that LHCSR1 was also pH-sensitive and that it induces LHCII quenching (84), which supports the previous observation of NPQ in an LHCSR3-lacking mutant (85). Results from single molecule spectroscopy revealed the presence of two dissipative states in LHCSR1, controlled by pH and carotenoid composition (86).

Although C. reinhardtii has the gene for the photosystem II subunit S (PsbS), it does not express the protein (71). PsbS was expressed in C. reinhardtii, and it was determined that PsbS affects the induction of the LHCSR3 mechanism in green algae (87). However, PsbS alone is not enough to carry out LHCSR-regulated NPQ.

LHCSR genes are also present in moss and diatoms, but not in higher plants. The moss Physcomitrella patens utilizes both LHCSR and PsbS proteins in NPQ, in addition to the xanthophyll cycle (88). LHCSR-dependent quenching was shown to be enhanced by zeaxanthin binding to LHCSR (89), which is not the case for green algae (73). Because mosses are evolutionary intermediates between algae and higher plants, the presence of both LHCSR and PsbS-mediated NPQ mechanisms provides some insight into the evolution of photosynthesis from aquatic to land environments (6).

The diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum has an LHCSR ortholog denoted LHCX1 protein that controls NPQ (51), but with a few differences. Unlike LHCSR3, it is expressed constitutively and is most likely not a pH sensor because there are no lumenal residues that can be protonated (90). The presence of flexible and rapid quenching mechanisms is essential for diatoms because they are found in highly fluctuating light environments. In addition to LHCX, NPQ in diatoms is dependent on a variant of the xanthophyll cycle activated by light-driven ΔpH, involving the de-epoxidation of diadinoxanthin to diatoxanthin (DT). DT binds to LHCX to induce the aggregation and formation of quenching centers (6, 91). Based on time-resolved fluorescence data, the following two quenching centers were proposed: Q1 found in detached LHC oligomers and Q2 located in LHCX–DT–PSII (92). Exactly how DT is involved in the quenching is still not clear (6, 91). LHCX1 involvement in antenna aggregation and altered pigment interactions was recently shown in Cyclotella meneghiniana (93).

Higher plants

The requirements for the energy-dependent component of NPQ called qE in higher plants include ΔpH, PsbS protein, and the VAZ xanthophyll cycle. Activation of qE depends on PsbS (94, 95), a member of the LHC superfamily but with four instead of three transmembrane α-helices (51), which is the evolutionary counterpart of LHCSR from green algae (8). The availability of the PsbS crystal structure (96) has clarified some of the questions regarding PsbS. For instance, it was initially thought that PsbS was a pigment-binding protein (94), but the compact PsbS structure appears to preclude the formation of pigment-binding sites (96). This supports the observation that PsbS in reconstituted liposomes is stable without pigments (97). PsbS was also determined to be dimeric in both inactive and active forms (96), in contrast to the previous suggestion that monomerization of PsbS happens upon NPQ activation. Still, PsbS remains enigmatic, and among the issues that are still being debated involve PsbS localization and its interaction with other photosynthetic complexes (95). Recent cross-linking data from dark- and light-adapted thylakoids show that in the dark unquenched state, PsbS associates with the PSII supercomplex, whereas in the quenched state, it predominantly interacts with LHCII trimers (98). More recently, pulldown experiments have revealed that ΔpH and zeaxanthin affects PsbS–antenna interactions (99).

Activation of NPQ that occurs upon the generation of ΔpH leads to the protonation of PsbS (Glu-122 and Glu-226) (100) and the activation of the xanthophyll (VAZ) cycle (5, 6). At low pH, the enzyme violaxanthin de-epoxidase (VDE) is protonated, undergoes conformational rearrangement, and associates with the MGDG-rich region of the thylakoid membrane, where VDE uses ascorbate as a co-substrate to convert violaxanthin to antheraxanthin and to zeaxanthin (101, 102). Together, PsbS and the VAZ cycle facilitate the structural rearrangement of PSII antenna complexes to generate quenching centers (78, 95). The molecular mechanisms and nature of these quenching centers remain a subject of intense investigation and discussion, however, and are detailed elsewhere (4, 5, 7, 78).

Concluding remarks/future directions

Over the years, extensive research on non-photochemical quenching has led to a better understanding of the machineries and mechanisms driving this process, although questions still remain. In particular, the location and molecular mechanism of quenching in the various antenna complexes still need to be determined. How and where the different protein complexes involved in NPQ interact remain open questions. The availability of increasingly advanced techniques in spectroscopy, molecular biology and biochemistry, and computational modeling are very important tools in tackling these unknowns (5, 103–105).

Photosynthesis is a dynamic and complex process that requires several strategies for improvement of yield and efficiency, among which involve light harvesting optimization and non-photochemical quenching manipulations (103, 104, 106). For instance, new results indicate that NPQ can be exploited for improving photosynthetic productivity as shown in the work of Kromdijk et al. (107). By increasing the rate of xanthophyll cycle conversion and the amount of PsbS, an increase in the biomass yield of tobacco was achieved. In green algae, NPQ was also down-regulated to increase biomass production (85). Knowledge obtained about regulation of antennas can also be used for designing bioreactors to improve cyanobacterial biomass or metabolite production (108).

Although efficient light harvesting ensures photosynthetic efficiency, exposure to excess light and other stress conditions render the organisms susceptible to photooxidative damage. Therefore, mechanisms to balance between light harvesting and photoprotection must be in place to ensure the protection of the photosynthetic apparatus and survival of the organism. Photosynthetic organisms have evolved different light-harvesting capabilities to adapt to the varying environments in which they are found. Although light-harvesting antennas are structurally diverse, they are basically variations on a theme. Ultimately, antenna complexes function to maximize as well as regulate light absorption for the reaction center. Moreover, molecules such as carotenoids and quinones, together with the tuning effect of protein amino acid residues, are key players in the regulation of light harvesting in the antenna systems described herein. The diverse mechanisms of regulating excess excitation provide clues from which to borrow and may be used to improve photosynthetic efficiency, particularly in crop plants.

This work was supported by the Photosynthetic Antenna Research Center, an Energy Frontier Research Center funded by the United States Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences under Award Number DE-SC 0001035. This is the first article in the Thematic Minireview series “Green biological chemistry.” The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

- BChl

- bacteriochlorophyll

- LHC

- light-harvesting complex

- Car

- carotenoid

- RC

- reaction center

- Chl

- chlorophyll

- NPQ

- non-photochemical quenching

- OCP

- orange carotenoid protein

- PB

- phycobilisome

- NTD

- N-terminal domain

- CTD

- C-terminal domain

- OCPo

- inactive orange form

- OCPr

- orange carotenoid protein, red form

- FRP

- fluorescence recovery protein

- APC

- allophycocyanin

- PC

- phycocyanin

- Hli

- high-light–inducible

- VDE

- violaxanthin de-epoxidase

- FMO

- Fenna-Matthews-Olson

- LHCSR

- light-harvesting complex stress-related.

References

- 1. Blankenship R. E. (2014) Molecular Mechanisms of Photosynthesis, 2nd Ed., Wiley Interscience, New York [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mirkovic T., Ostroumov E. E., Anna J. M., van Grondelle R., Govindjee and Scholes G. D. (2017) Light absorption and energy transfer in the antenna complexes of photosynthetic organisms. Chem. Rev. 117, 249–293 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Croce R., and van Amerongen H. (2014) Natural strategies for photosynthetic light harvesting. Nat. Chem. Biol. 10, 492–501 10.1038/nchembio.1555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Büchel C. (2015) Evolution and function of light harvesting proteins. J. Plant Physiol. 172, 62–75 10.1016/j.jplph.2014.04.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Demmig-Adams B. Garab G., and Adams W. III, and Govindjee (eds) (2014) Non-photochemical Quenching and Energy Dissipation in Plants, Algae and Cyanobacteria. Springer, Dordrecht, the Netherlands [Google Scholar]

- 6. Goss R., and Lepetit B. (2015) Biodiversity of NPQ. J. Plant Physiol. 172, 13–32 10.1016/j.jplph.2014.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ruban A. V. (2016) Nonphotochemical chlorophyll fluorescence quenching: mechanism and effectiveness in protecting plants from photodamage. Plant Physiol. 170, 1903–1916 10.1104/pp.15.01935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Niyogi K. K., and Truong T. B. (2013) Evolution of flexible non-photochemical quenching mechanisms that regulate light harvesting in oxygenic photosynthesis. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 16, 307–314 10.1016/j.pbi.2013.03.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Blankenship R. E., and Matsuura K. (2003) in Light-Harvesting Antennas in Photosynthesis (Green B. R., and Parson W. W., eds) pp. 195–217, Springer, Dordrecht, the Netherlands [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bryant D. A., Costas A. M., Maresca J. A., Chew A. G., Klatt C. G., Bateson M. M., Tallon L. J., Hostetler J., Nelson W. C., Heidelberg J. F., and Ward D. M. (2007) Candidatus Chloracidobacterium thermophilum: an aerobic phototrophic acidobacterium. Science 317, 523–526 10.1126/science.1143236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Orf G. S., and Blankenship R. E. (2013) Chlorosome antenna complexes from green photosynthetic bacteria. Photosynth. Res. 116, 315–331 10.1007/s11120-013-9869-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pšenčík J., Butcher S. J., and Tuma R. (2014) in The Structural Basis of Biological Energy Generation (Hohmann-Marriott M. F., ed) pp. 77–109, Springer Science and Business, Dordrecht, the Netherlands [Google Scholar]

- 13. Olson J. M. (2004) The FMO protein. Photosynth. Res. 80, 181–187 10.1023/B:PRES.0000030428.36950.43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tronrud D. E., Wen J., Gay L., and Blankenship R. E. (2009) The structural basis for the difference in absorbance spectra for the FMO antenna protein from various green sulfur bacteria. Photosynth. Res. 100, 79–87 10.1007/s11120-009-9430-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wen J., Zhang H., Gross M. L., and Blankenship R. E. (2011) Native electrospray mass spectrometry reveals the nature and stoichiometry of pigments in the FMO photosynthetic antenna protein. Biochemistry 50, 3502–3511 10.1021/bi200239k [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hohmann-Marriott M. F., and Blankenship R. E. (2007) Variable fluorescence in green sulfur bacteria. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1767, 106–113 10.1016/j.bbabio.2006.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Frigaard N.-U., Takaichi S., Hirota M., Shimada K., and Matsuura K. (1997) Quinones in chlorosomes of green sulfur bacteria and their role in the redox-dependent fluorescence studied in chlorosome-like bacteriochlorophyll c aggregates. Arch. Microbiol. 167, 343–349 10.1007/s002030050453 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Frigaard N.-U., Matsuura K., Hirota M., Miller M., and Cox R. P. (1998) Studies of the location and function of isoprenoid quinones in chlorosomes from green sulfur bacteria. Photosynth. Res. 58, 81–90 10.1023/A:1006043706652 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Frigaard N., Tokita S., and Matsuura K. (1999) Exogenous quinones inhibit photosynthetic electron transfer in Chloroflexus aurantiacus by specific quenching of the excited bacteriochlorophyll c antenna. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1413, 108–116 10.1016/S0005-2728(99)00094-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tokita S., Frigaard N.-U., Hirota M., Shimada K., and Matsuura K. (2000) Quenching of bacteriochlorophyll fluorescence in chlorosomes from Chloroflexus aurantiacus by exogenous quinones. Photochem. Photobiol. 72, 345–350 10.1562/0031-8655(2000)072%3C0345:QOBFIC%3E2.0.CO%3B2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Garcia Costas A. M., Tsukatani Y., Romberger S. P., Oostergetel G. T., Boekema E. J., Golbeck J. H., and Bryant D. A. (2011) Ultrastructural analysis and identification of envelope proteins of “Candidatus Chloracidobacterium thermophilum” chlorosomes. J. Bacteriol. 193, 6701–6711 10.1128/JB.06124-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. van Noort P. I., Zhu Y., LoBrutto R., and Blankenship R. E. (1997) Redox effects on the excited-state lifetime in chlorosomes and bacteriochlorophyll c oligomers. Biophys. J. 72, 316–325 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78670-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Melø T. B., Frigaard N. U., Matsuura K., and Razi Naqvi K. (2000) Electronic energy transfer involving carotenoid pigments in chlorosomes of two green bacteria: Chlorobium tepidum and Chloroflexus aurantiacus. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 56A, 2001–2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Arellano J. B., Melø T. B., Borrego C. M., Garcia-Gil J., and Naqvi K. R. (2000) Nanosecond laser photolysis studies of chlorosomes and artificial aggregates containing bacteriochlorophyll e: evidence for the proximity of carotenoids and bacteriochlorophyll a in chlorosomes from Chlorobium phaeobacteroides strain CL1401. Photochem. Photobiol. 72, 669–675 10.1562/0031-8655(2000)072%3C0669:NLPSOC%3E2.0.CO%3B2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kim H., Li H., Maresca J. A., Bryant D. A., and Savikhin S. (2007) Triplet exciton formation as a novel photoprotection mechanism in chlorosomes of Chlorobium tepidum. Biophys. J. 93, 192–201 10.1529/biophysj.106.103556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhou W., LoBrutto R., Lin S., and Blankenship R. E. (1994) Redox effects on the bacteriochlorophyll a-containing Fenna-Matthews-Olson protein from Chlorobium tepidum. Photosynth. Res. 41, 89–96 10.1007/BF02184148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Orf G. S., Saer R. G., Niedzwiedzki D. M., Zhang H., McIntosh C. L., Schultz J. W., Mirica L. M., and Blankenship R. E. (2016) Evidence for a cysteine-mediated mechanism of excitation energy regulation in a photosynthetic antenna complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, E4486–E4493 10.1073/pnas.1603330113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Adir N. (2005) Elucidation of the molecular structures of components of the phycobilisome: reconstructing a giant. Photosynth. Res. 85, 15–32 10.1007/s11120-004-2143-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wilson A., Ajlani G., Verbavatz J.-M., Vass I., Kerfeld C. A., and Kirilovsky D. (2006) A soluble carotenoid protein involved in phycobilisome-related energy dissipation in cyanobacteria. Plant Cell 18, 992–1007 10.1105/tpc.105.040121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kerfeld C. A., Sawaya M. R., Brahmandam V., Cascio D., Ho K. K., Trevithick-Sutton C. C., Krogmann D. W., and Yeates T. O. (2003) The crystal structure of a cyanobacterial water-soluble carotenoid binding protein. Structure 11, 55–65 10.1016/S0969-2126(02)00936-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gupta S., Guttman M., Leverenz R. L., Zhumadilova K., Pawlowski E. G., Petzold C. J., Lee K. K., Ralston C. Y., and Kerfeld C. A. (2015) Local and global structural drivers for the photoactivation of the orange carotenoid protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, E5567–E5574 10.1073/pnas.1512240112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Liu H., Zhang H., Orf G. S., Lu Y., Jiang J., King J. D., Wolf N. R., Gross M. L., and Blankenship R. E. (2016) Dramatic domain rearrangements of the cyanobacterial orange carotenoid protein upon photoactivation. Biochemistry 55, 1003–1009 10.1021/acs.biochem.6b00013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Maksimov E. G., Sluchanko N. N., Mironov K. S., Shirshin E. A., Klementiev K. E., Tsoraev G. V., Moldenhauer M., Friedrich T., Los D. A., Allakhverdiev S. I., Paschenko V. Z., and Rubin A. B. (2017) Fluorescent labeling preserving OCP photoactivity reveals its reorganization during the photocycle. Biophys. J. 112, 46–56 10.1016/j.bpj.2016.11.3193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Leverenz R. L., Sutter M., Wilson A., Gupta S., Thurotte A., Bourcier de Carbon C., Petzold C. J., Ralston C., Perreau F., Kirilovsky D., and Kerfeld C. A. (2015) A 12 Å carotenoid translocation in a photoswitch associated with cyanobacterial photoprotection. Science 348, 1463–1466 10.1126/science.aaa7234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kirilovsky D., and Kerfeld C. A. (2012) The orange carotenoid protein in photoprotection of photosystem II in cyanobacteria. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1817, 158–166 10.1016/j.bbabio.2011.04.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kirilovsky D., and Kerfeld C. A. (2016) Cyanobacterial photoprotection by the orange carotenoid protein. Nat. Plants 2, 16180 10.1038/nplants.2016.180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bandara S., Ren Z., Lu L., Zeng X., Shin H., Zhao K.-H., and Yang X. (2017) Photoactivation mechanism of a carotenoid-based photoreceptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, 6286–6291 10.1073/pnas.1700956114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Maksimov E. G., Shirshin E. A., Sluchanko N. N., Zlenko D. V., Parshina E. Y., Tsoraev G. V., Klementiev K. E., Budylin G. S., Schmitt F.-J., Friedrich T., Fadeev V. V., Paschenko V. Z., and Rubin A. B. (2015) The signaling state of orange carotenoid protein. Biophys. J. 109, 595–607 10.1016/j.bpj.2015.06.052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Harris D., Tal O., Jallet D., Wilson A., Kirilovsky D., and Adir N. (2016) Orange carotenoid protein burrows into the phycobilisome to provide photoprotection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, E1655–E1662 10.1073/pnas.1523680113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sutter M., Wilson A., Leverenz R. L., Lopez-Igual R., Thurotte A., Salmeen A. E., Kirilovsky D., and Kerfeld C. A. (2013) Crystal structure of the FRP and identification of the active site for modulation of OCP-mediated photoprotection in cyanobacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 10022–10027 10.1073/pnas.1303673110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lu Y., Liu H., Saer R., Li V. L., Zhang H., Shi L., Goodson C., Gross M. L., and Blankenship R. E. (2017) A molecular mechanism for nonphotochemical quenching in cyanobacteria. Biochemistry 56, 2812–2823 10.1021/acs.biochem.7b00202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Scott M., McCollum C., Vasil'ev S., Crozier C., Espie G. S., Krol M., Huner N. P., and Bruce D. (2006) Mechanism of the down regulation of photosynthesis by blue light in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Biochemistry 45, 8952–8958 10.1021/bi060767p [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gwizdala M., Wilson A., and Kirilovsky D. (2011) In vitro reconstitution of the cyanobacterial photoprotective mechanism mediated by the orange carotenoid protein in Synechocystis PCC 6803. Plant Cell 23, 2631–2643 10.1105/tpc.111.086884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kuzminov F. I., Karapetyan N. V., Rakhimberdieva M. G., Elanskaya I. V., Gorbunov M. Y., and Fadeev V. V. (2012) Investigation of OCP-triggered dissipation of excitation energy in PSI/PSII-less Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 mutant using non-linear laser fluorimetry. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1817, 1012–1021 10.1016/j.bbabio.2012.03.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Zhang H., Liu H., Niedzwiedzki D. M., Prado M., Jiang J., Gross M. L., and Blankenship R. E. (2014) Molecular mechanism of photoactivation and structural location of the cyanobacterial orange carotenoid protein. Biochemistry 53, 13–19 10.1021/bi401539w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Tian L., van Stokkum I. H., Koehorst R. B., Jongerius A., Kirilovsky D., and van Amerongen H. (2011) Site, rate, and mechanism of photoprotective quenching in cyanobacteria. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 18304–18311 10.1021/ja206414m [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Berera R., van Stokkum I. H., Gwizdala M., Wilson A., Kirilovsky D., and van Grondelle R. (2012) The photophysics of the orange carotenoid protein, a light-powered molecular switch. J. Phys. Chem. B 116, 2568–2574 10.1021/jp2108329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Maksimov E. G., Schmitt F. J., Shirshin E. A., Svirin M. D., Elanskaya I. V., Friedrich T., Fadeev V. V., Paschenko V. Z., and Rubin A. B. (2014) The time course of non-photochemical quenching in phycobilisomes of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 as revealed by picosecond time-resolved fluorimetry. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1837, 1540–1547 10.1016/j.bbabio.2014.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Sedoud A., López-Igual R., Ur Rehman A., Wilson A., Perreau F., Boulay C., Vass I., Krieger-Liszkay A., and Kirilovsky D. (2014) The cyanobacterial photoactive orange carotenoid protein is an excellent singlet oxygen quencher. Plant Cell 26, 1781–1791 10.1105/tpc.114.123802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Gwizdala M., Berera R., Kirilovsky D., van Grondelle R., and Krüger T. P. (2016) Controlling light harvesting with light. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 11616–11622 10.1021/jacs.6b04811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Engelken J., Funk C., and Adamska I. (2012) in Functional Genomics and Evolution of Photosynthetic Systems (Burnap R., and Vermaas W., eds) pp. 265–284, Springer, Dordrecht, the Netherlands [Google Scholar]

- 52. He Q., Dolganov N., Bjorkman O., and Grossman A. R. (2001) The high light-inducible polypeptides in Synechocystis PCC 6803: expression and function in high light. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 306–314 10.1074/jbc.M008686200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Bhaya D., Dufresne A., Vaulot D., and Grossman A. (2002) Analysis of the hli gene family in marine and freshwater cyanobacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 215, 209–219 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2002.tb11393.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Komenda J., and Sobotka R. (2016) Cyanobacterial high-light-inducible proteins–protectors of chlorophyll–protein synthesis and assembly. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1857, 288–295 10.1016/j.bbabio.2015.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Knoppová J., Sobotka R., Tichy M., Yu J., Konik P., Halada P., Nixon P. J., and Komenda J. (2014) Discovery of a chlorophyll binding protein complex involved in the early steps of photosystem II assembly in Synechocystis. Plant Cell 26, 1200–1212 10.1105/tpc.114.123919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Staleva H., Komenda J., Shukla M. K., Šlouf V., Kaňa R., Polívka T., and Sobotka R. (2015) Mechanism of photoprotection in the cyanobacterial ancestor of plant antenna proteins. Nat. Chem. Biol. 11, 287–291 10.1038/nchembio.1755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Niedzwiedzki D. M., Tronina T., Liu H., Staleva H., Komenda J., Sobotka R., Blankenship R. E., and Polívka T. (2016) Carotenoid-induced non-photochemical quenching in the cyanobacterial chlorophyll synthase–HliC/D complex. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1857, 1430–1439 10.1016/j.bbabio.2016.04.280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Llansola-Portoles M. J., Sobotka R., Kish E., Shukla M. K., Pascal A. A., Polívka T., and Robert B. (2017) Twisting a β-carotene, an adaptive trick from nature for dissipating energy during photoprotection. J. Biol. Chem. 292, 1396–1403 10.1074/jbc.M116.753723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Wilson A., Boulay C., Wilde A., Kerfeld C. A., and Kirilovsky D. (2007) Light-induced energy dissipation in iron-starved cyanobacteria: roles of OCP and IsiA proteins. Plant Cell 19, 656–672 10.1105/tpc.106.045351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Wang Q., Hall C. L., Al-Adami M. Z., and He Q. (2010) IsiA is required for the formation of photosystem I supercomplexes and for efficient state transition in Synechocystis PCC 6803. PLoS ONE 5, e10432 10.1371/journal.pone.0010432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Murray J. W., Duncan J., and Barber J. (2006) CP43-like chlorophyll binding proteins: structural and evolutionary implications. Trends Plant Sci. 11, 152–158 10.1016/j.tplants.2006.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Berera R., van Stokkum I. H., d'Haene S., Kennis J. T., van Grondelle R., and Dekker J. P. (2009) A mechanism of energy dissipation in cyanobacteria. Biophys. J. 96, 2261–2267 10.1016/j.bpj.2008.12.3905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Berera R., van Stokkum I. H., Kennis J. T., van Grondelle R., and Dekker J. P. (2010) The light-harvesting function of carotenoids in the cyanobacterial stress-inducible IsiA complex. Chem. Phys. 373, 65–70 10.1016/j.chemphys.2010.01.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Chen H.-Y., Liberton M., Pakrasi H. B., and Niedzwiedzki D. M. (2017) Reevaluating the mechanism of excitation energy regulation in iron-starved cyanobacteria. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1858, 249–258 10.1016/j.bbabio.2017.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Neilson J. A., and Durnford D. G. (2010) Structural and functional diversification of the light-harvesting complexes in photosynthetic eukaryotes. Photosynth. Res. 106, 57–71 10.1007/s11120-010-9576-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Liu L.-N., Elmalk A. T., Aartsma T. J., Thomas J.-C., Lamers G. E., Zhou B.-C., and Zhang Y.-Z. (2008) Light-induced energetic decoupling as a mechanism for phycobilisome-related energy dissipation in red algae: a single molecule study. PLoS ONE 3, e3134 10.1371/journal.pone.0003134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Kirilovsky D. (2015) Modulating energy arriving at photochemical reaction centers: orange carotenoid protein-related photoprotection and state transitions. Photosynth. Res. 126, 3–17 10.1007/s11120-014-0031-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Kaňa R., Kotabová E., Lukeš M., Papáčekˇ S., Matonoha C, Liu L.-N., Prášil O., and Mullineaux C. W. (2014) Phycobilisome mobility and its role in the regulation of light harvesting in red algae. Plant Physiol. 165, 1618–1631 10.1104/pp.114.236075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Krupnik T., Kotabová E., van Bezouwen L. S., Mazur R., Garstka M., Nixon P. J., Barber J., Kaňa R., Boekema E. J., and Kargul J. (2013) A reaction center-dependent photoprotection mechanism in a highly robust photosystem II from an extremophilic red alga, Cyanidioschyzon merolae. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 23529–23542 10.1074/jbc.M113.484659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Tokutsu R., and Minagawa J. (2013) Energy-dissipative supercomplex of photosystem II associated with LHCSR3 in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 10016–10021 10.1073/pnas.1222606110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Minagawa J., and Tokutsu R. (2015) Dynamic regulation of photosynthesis in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant J. 82, 413–428 10.1111/tpj.12805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Peers G., Truong T. B., Ostendorf E., Busch A., Elrad D., Grossman A. R., Hippler M., and Niyogi K. K. (2009) An ancient light-harvesting protein is critical for the regulation of algal photosynthesis. Nature 462, 518–521 10.1038/nature08587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Bonente G., Ballottari M., Truong T. B., Morosinotto T., Ahn T. K., Fleming G. R., Niyogi K. K., and Bassi R. (2011) Analysis of LhcSR3, a protein essential for feedback de-excitation in the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. PLoS Biol. 9, e1000577 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Xue H., Bergner S. V., Scholz M., and Hippler M. (2015) Novel insights into the function of LHCSR3 in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant Signal. Behav. 10, e1058462 10.1080/15592324.2015.1058462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Ferrante P., Ballottari M., Bonente G., Giuliano G., and Bassi R. (2012) LHCBM1 and LHCBM2/7 polypeptides, components of major LHCII complex, have distinct functional roles in photosynthetic antenna system of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 16276–16288 10.1074/jbc.M111.316729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Natali A., and Croce R. (2015) Characterization of the major light-harvesting complexes (LHCBM) of the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. PLoS ONE 10, e0119211 10.1371/journal.pone.0119211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Girolomoni L., Ferrante P., Berteotti S., Giuliano G., Bassi R., and Ballottari M. (2017) The function of LHCBM4/6/8 antenna proteins in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. J. Exp. Bot. 68, 627–641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Derks A., Schaven K., and Bruce D. (2015) Diverse mechanisms for photoprotection in photosynthesis. Dynamic regulation of photosystem II excitation in response to rapid environmental change. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1847, 468–485 10.1016/j.bbabio.2015.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Petroutsos D., Tokutsu R., Maruyama S., Flori S., Greiner A., Magneschi L., Cusant L., Kottke T., Mittag M., Hegemann P., Finazzi G., and Minagawa J. (2016) A blue-light photoreceptor mediates the feedback regulation of photosynthesis. Nature 537, 563–566 10.1038/nature19358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Liguori N., Roy L. M., Opacic M., Durand G., and Croce R. (2013) Regulation of light harvesting in the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii: the C terminus of LHCSR is the knob of a dimmer switch. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 18339–18342 10.1021/ja4107463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Ballottari M., Truong T. B., De Re E., Erickson E., Stella G. R., Fleming G. R., Bassi R., and Niyogi K. K. (2016) Identification of pH-sensing sites in the light-harvesting complex stress-related 3 protein essential for triggering non-photochemical quenching in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 7334–7346 10.1074/jbc.M115.704601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Allorent G., Tokutsu R., Roach T., Peers G., Cardol P., Girard-Bascou J., Seigneurin-Berny D., Petroutsos D., Kuntz M., Breyton C., Franck F., Wollman F.-A., Niyogi K. K., Krieger-Liszkay A., Minagawa J., and Finazzi G. (2013) A dual strategy to cope with high light in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant Cell 25, 545–557 10.1105/tpc.112.108274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Pinnola A., Ghin L., Gecchele E., Merlin M., Alboresi A., Avesani L., Pezzotti M., Capaldi S., Cazzaniga S., and Bassi R. (2015) Heterologous expression of moss LHCSR1: the chlorophyll a-xanthophyll pigment–protein complex catalyzing non-photochemical quenching, in Nicotiana sp. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 24340–24354 10.1074/jbc.M115.668798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Dinc E., Tian L., Roy L. M., Roth R., Goodenough U., and Croce R. (2016) LHCSR1 induces a fast and reversible pH-dependent fluorescence quenching in LHCII in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, 7673–7678 10.1073/pnas.1605380113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Berteotti S., Ballottari M., and Bassi R. (2016) Increased biomass productivity in green algae by tuning non-photochemical quenching. Sci. Rep. 6, 21339 10.1038/srep21339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 86. Kondo T., Pinnola A., Chen W. J., Dall'Osto L., Bassi R., and Schlau-Cohen G. S. (2017) Single-molecule spectroscopy of LHCSR1 protein dynamics identifies two distinct states responsible for multi-time scale photosynthetic photoprotection. Nat. Chem. 9, 772–778 10.1038/nchem.2818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Correa-Galvis V., Redekop P., Guan K., Griess A., Truong T. B., Wakao S., Niyogi K. K., and Jahns P. (2016) Photosystem II subunit PsbS is involved in the induction of LHCSR protein-dependent energy dissipation in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 17478–17487 10.1074/jbc.M116.737312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Alboresi A., Gerotto C., Giacometti G. M., Bassi R., and Morosinotto T. (2010) Physcomitrella patens mutants affected on heat dissipation clarify the evolution of photoprotection mechanisms upon land colonization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 11128–11133 10.1073/pnas.1002873107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Pinnola A., Dall'Osto L., Gerotto C., Morosinotto T., Bassi R., and Alboresi A. (2013) Zeaxanthin binds to light-harvesting complex stress-related protein to enhance nonphotochemical quenching in Physcomitrella patens. Plant Cell 25, 3519–3534 10.1105/tpc.113.114538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Bailleul B., Rogato A., de Martino A., Coesel S., Cardol P., Bowler C., Falciatore A., and Finazzi G. (2010) An atypical member of the light-harvesting complex stress-related protein family modulates diatom responses to light. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 18214–18219 10.1073/pnas.1007703107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Lavaud J., and Goss R. (2014) in Non-photochemical Quenching and Energy Dissipation in Plants, Algae and Cyanobacteria (Demmig-Adams B., Garab G., Adams W., and Govindjee, eds) pp. 421–443, Springer, Dordrecht, the Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- 92. Miloslavina Y., Grouneva I., Lambrev P. H., Lepetit B., Goss R., Wilhelm C., and Holzwarth A. R. (2009) Ultrafast fluorescence study on the location and mechanism of non-photochemical quenching in diatoms. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1787, 1189–1197 10.1016/j.bbabio.2009.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Ghazaryan A., Akhtar P., Garab G., Lambrev P. H., and Büchel C. (2016) Involvement of the Lhcx protein Fcp6 of the diatom Cyclotella meneghiniana in the macro-organisation and structural flexibility of thylakoid membranes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1857, 1373–1379 10.1016/j.bbabio.2016.04.288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Li X.-P., Björkman O., Shih C., Grossman A. R., Rosenquist M., Jansson S., and Niyogi K. K. (2000) A pigment-binding protein essential for regulation of photosynthetic light harvesting. Nature 403, 391–395 10.1038/35000131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Brooks M. D., Jansson S., and Niyogi K. K. (2014) in Non-photochemical Quenching and Energy Dissipation in Plants, Algae and Cyanobacteria (Demmig-Adams B., Adams W., and Garab G., eds) pp. 297–314, Springer, Dordrecht, the Netherlands [Google Scholar]

- 96. Fan M., Li M., Liu Z., Cao P., Pan X., Zhang H., Zhao X., Zhang J., and Chang W. (2015) Crystal structures of the PsbS protein essential for photoprotection in plants. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 22, 729–735 10.1038/nsmb.3068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Wilk L., Grunwald M., Liao P.-N., Walla P. J., and Kühlbrandt W. (2013) Direct interaction of the major light-harvesting complex II and PsbS in nonphotochemical quenching. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 5452–5456 10.1073/pnas.1205561110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Correa-Galvis V., Poschmann G., Melzer M., Stühler K., and Jahns P. (2016) PsbS interactions involved in the activation of energy dissipation. Nat. Plants 2, 15225 10.1038/nplants.2015.225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Sacharz J., Giovagnetti V., Ungerer P., Mastroianni G., and Ruban A. V. (2017) The xanthophyll cycle affects reversible interactions between PsbS and light-harvesting complex II to control non-photochemical quenching. Nat. Plants 3, 16225 10.1038/nplants.2016.225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Li X.-P., Gilmore A. M., Caffarri S., Bassi R., Golan T., Kramer D., and Niyogi K. K. (2004) Regulation of photosynthetic light harvesting involves intrathylakoid lumen pH sensing by the PsbS protein. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 22866–22874 10.1074/jbc.M402461200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Müller P., Li X.-P., and Niyogi K. K. (2001) Non-photochemical quenching. A response to excess light energy. Plant Physiol. 125, 1558–1566 10.1104/pp.125.4.1558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Jahns P., Latowski D., and Strzalka K. (2009) Mechanism and regulation of the violaxanthin cycle: the role of antenna proteins and membrane lipids. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1787, 3–14 10.1016/j.bbabio.2008.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Murchie E. H., and Niyogi K. K. (2011) Manipulation of photoprotection to improve plant photosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 155, 86–92 10.1104/pp.110.168831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Ort D. R., Merchant S. S., Alric J., Barkan A., Blankenship R. E., Bock R., Croce R., Hanson M. R., Hibberd J. M., Long S. P., Moore T. A., Moroney J., Niyogi K. K., Parry M. A., Peralta-Yahya P. P., et al. (2015) Redesigning photosynthesis to sustainably meet global food and bioenergy demand. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, 8529–8536 10.1073/pnas.1424031112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Tietz S., Hall C. C., Cruz J. A., and Kramer D. M. (2017) NPQ(T): a chlorophyll fluorescence parameter for rapid estimation and imaging of non-photochemical quenching of excitons in photosystem-II-associated antenna complexes. Plant Cell Environ. 40, 1243–1255 10.1111/pce.12924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Long S. P., Marshall-Colon A., and Zhu X.-G. (2015) Meeting the global food demand of the future by engineering crop photosynthesis and yield potential. Cell 161, 56–66 10.1016/j.cell.2015.03.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Kromdijk J., Głowacka K., Leonelli L., Gabilly S. T., Iwai M., Niyogi K. K., and Long S. P. (2016) Improving photosynthesis and crop productivity by accelerating recovery from photoprotection. Science 354, 857–861 10.1126/science.aai8878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Lea-Smith D. J., Bombelli P., Dennis J. S., Scott S. A., Smith A. G., and Howe C. J. (2014) Phycobilisome-deficient strains of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 have reduced size and require carbon-limiting conditions to exhibit enhanced productivity. Plant Physiol. 165, 705–714 10.1104/pp.114.237206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]