Abstract

Enfuvirtide (T20) is the only viral fusion inhibitor approved for clinical use, but it has relatively weak anti-HIV activity and easily induces drug resistance. In succession to T20, T1249 has been designed as a 39-mer peptide composed of amino acid sequences derived from HIV-1, HIV-2, and simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV); however, its development has been suspended due to formulation difficulties. We recently developed a T20-based lipopeptide (LP-40) showing greatly improved pharmaceutical properties. Here, we generated a T1249-based lipopeptide, termed LP-46, by replacing its C-terminal tryptophan-rich sequence with fatty acid. As compared with T20, T1249, and LP-40, the truncated LP-46 (31-mer) had dramatically increased activities in inhibiting a large panel of HIV-1 subtypes, with IC50 values approaching low picomolar concentrations. Also, LP-46 was an exceptionally potent inhibitor against HIV-2, SIV, and T20-resistant variants, and it displayed obvious synergistic effects with LP-40. Furthermore, we showed that LP-46 had increased helical stability and binding affinity with the target site. The crystal structure of LP-46 in complex with a target surrogate revealed its critical binding motifs underlying the mechanism of action. Interestingly, it was found that the introduced pocket-binding domain in LP-46 did not interact with the gp41 pocket as expected; instead, it adopted a mode similar to that of LP-40. Therefore, our studies have provided an exceptionally potent and broad fusion inhibitor for developing new anti-HIV drugs, which can also serve as a tool to exploit the mechanisms of viral fusion and inhibition.

Keywords: human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), HIV-1, HIV-2, antiviral agent, membrane fusion, inhibitor, peptides, structure-function, crystal structure, fusion inhibitor, lipopeptide, T1249, T20

Introduction

The first step of HIV infection involves virus-cell or cell-cell fusion mediated by the trimeric viral envelope (Env)3 glycoproteins gp120 and gp41 (1–3). Binding of the surface subunit gp120 to the cell receptor CD4 along with a chemokine receptor (CCR5 or CXCR4) triggers a series of conformational changes in the gp120/gp41 complex and further activates the fusogenic activity of the transmembrane subunit gp41. The fusion peptide located at the N terminus of gp41 is exposed and inserts into the cell membrane so that the gp41 ectodomain undergoes a prehairpin intermediate state to bridge the viral and cell membranes. Then the C-terminal heptad repeats (CHR) of gp41 collapse in an antiparallel fashion into the inner hydrophobic grooves created by the trimeric N-terminal heptad repeat (NHR) helices, leading a stable six-helix bundle (6-HB) that pulls two membranes into close proximity for fusion (4–6). The crystal structures of 6-HBs have revealed a deep hydrophobic pocket on the C-terminal portion of NHR helices, which is inserted by the hydrophobic residues from the pocket-binding domain (PBD) of the CHR helix (4–7). Recently, we and others identified a subpocket located immediately downstream of the deep pocket, which also stabilizes the interactions of the NHR and CHR helices (8–10). Both pockets play essential roles in viral fusion and entry, thus offering ideal target sites for developing anti-HIV agents (7, 8, 10–12).

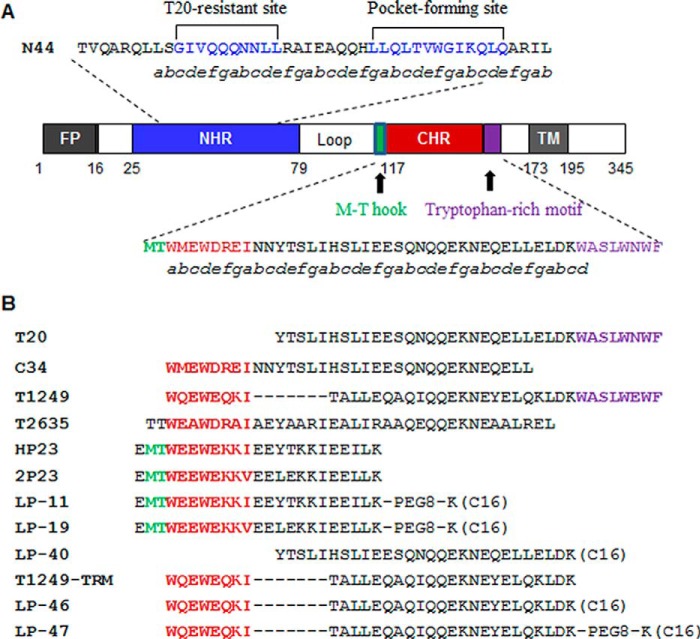

Serendipitous discovery of the peptide drug T20 (enfuvirtide) from the CHR of HIV-1 gp41 did open an avenue for developing a new class of antiviral drugs (13–15). Also importantly, T20 and its derivatives have been used as powerful tools to explore the mechanisms of viral fusion and inhibition (7, 11, 16). It is accepted that CHR- or NHR-derived peptides act through binding to the prehairpin intermediate to form a heterogeneous 6-HB, thus arresting viral membrane fusion in a dominant-negative manner (11, 17, 18). Approved in 2003, T20 remains the only membrane fusion inhibitor available for the treatment of viral infection; however, T20 has multiple defects that significantly limit its clinical application. First, it has relatively weak antiviral activity and a short in vivo half-life, thus requiring frequent injections at a high dosage (90 mg, twice daily) (19–22); second, it has a low genetic barrier for drug resistance, thus resulting in the emergence of diverse HIV-1 mutants (18, 20, 21, 23); third, T20 is not efficient on HIV-2 isolates that have already spread to different regions worldwide and caused millions of infections (24–27). In succession to T20, T1249 (tifuvirtide) was designed as a second-generation fusion inhibitor with significantly improved pharmaceutical profiles (28, 29). As depicted in Fig. 1, it is a 39-amino acid polypeptide composed of mixed amino acid sequences derived from HIV-1, HIV-2, and SIV strains. Specially, T1249 contains three discontinuous functional sites based on their positioning on the NHR target: an introduced PBD at its N terminus, an NHR-binding sequence (CHR core) in the middle site, and a tryptophan-rich motif (TRM) at the C terminus. Preclinical and clinical studies demonstrated that T1249 exhibited significantly increased antiviral activity, including its inhibition on T20-resistant HIV-1 mutants and HIV-2 isolates (28–31). Unfortunately, T1249 underwent considerable difficulties of formulation and production, and thus its clinical development was halted. Nevertheless, its unique structure and antiviral spectrum remain highly attractive for exploring the mechanisms of viral fusion and inhibition and as a template to design new fusion inhibitors.

Figure 1.

Schematic view of HIV-1 gp41 and its NHR- and CHR-derived peptides. A, the functional domains of gp41 protein. The gp41 numbering of HIV-1HXB2 was used. FP, fusion peptide; TM, transmembrane domain. The positions and amino acid sequences corresponding to the T20-resistant site and pocket-forming site in the NHR are marked in blue. The positions and amino acid sequences corresponding to the M-T hook structure, PBD, and tryptophan-rich motif (TRM) in the CHR are marked in green, red, and purple, respectively. B, primary structure of gp41 CHR-derived viral fusion inhibitors. The dashed lines in T1249 indicate the missed residues corresponding to the functional domains of the CHR; the C16 in parentheses represents a fatty acid group; PEG8 represents a linker of 8-unit polyethylene glycol.

Earlier works demonstrate that genetically anchoring fusion inhibitor peptides to the membrane of target cells can greatly increase the antiviral activity (32, 33). Emerging studies suggest that lipid conjugation is a more efficient approach to design viral fusion inhibitors (34–39). It is thought that the resulting lipopeptides can interact with the cell membranes, thus raising the local concentration of the inhibitors at the fusion site (34, 38). By conjugating different lipids (fatty acid, cholesterol, sphingolipids) to the C terminus of short peptides that mainly target the NHR pocket site, we previously developed the lipopeptides LP-11 and LP-19 (Fig. 1), which did show markedly increased anti-HIV potency and in vivo half-lives (36, 37). Promisingly, a short-term monotherapy of LP-19 could reduce viral loads to undetectable levels in both acutely and chronically simian-human immunodeficiency virus–infected rhesus monkeys (37). Very recently, we developed a T20-based lipopeptide termed LP-40, which demonstrated a binding mode different from that of LP-11 and LP-19 (40). Interestingly, LP-40 was more potent than LP-11 in inhibiting HIV-1 Env-mediated cell-cell fusion, whereas it was less active at inhibiting viral entry, and the two classes of inhibitors displayed synergistic and complementary antiviral effects. However, LP-40 had no appreciable improvement on T20-resistant mutants and HIV-2 isolates.

In this study, we focused on developing a more potent and broad viral fusion inhibitor by using T1249 as a template. A novel lipopeptide, termed LP-46, was created by replacing its TRM with a C16 fatty acid group. Impressively, LP-46 showed exceptionally potent activities in inhibiting HIV-1, HIV-2, SIV, and T20-resistant viruses and displayed synergistic effects with LP-40. Consistent with its inhibitory activity, LP-46 had greatly increased helical stability and binding affinity with the target site. The crystal structure of LP-46 revealed that the introduced PBD in the N terminus of LP-46 did not bind to the hydrophobic pocket site as expected but rather adopted a binding mode, as did LP-40. Therefore, our studies have generated the most potent and broad HIV-1/2 and SIV fusion inhibitor known to date, which not only provides an ideal candidate for drug development, but also serves as a critical tool to investigate the mechanisms of viral fusion and inhibition.

Results

Generation of an exceptionally potent T1249-based lipopeptide fusion inhibitor

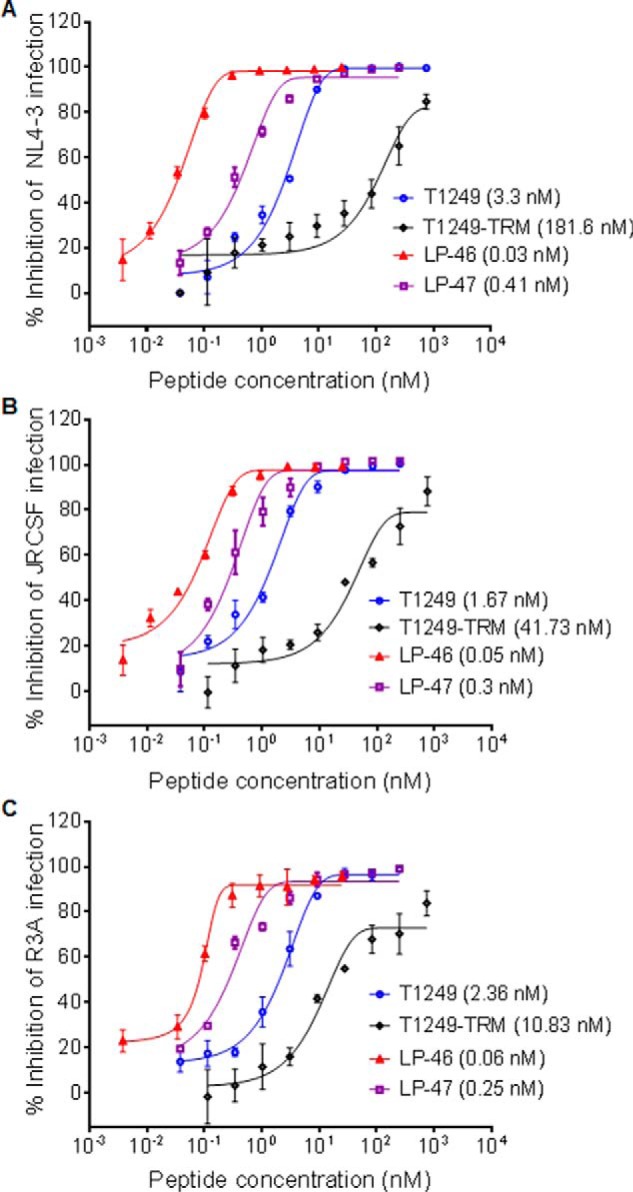

We recently verified the importance of the TRM in T20 for its anti-HIV activity (40). To validate the function of the TRM in T1249, we synthesized the truncated peptide T1249-TRM by deleting the TRM from T1249 (Fig. 1), and their antiviral activities were compared with three replicative HIV-1 strains. As expected, T1249-TRM showed a markedly decreased inhibitory activity (Fig. 2). Specifically, T1249 inhibited NL4-3 (subtype B, X4), JRCSF (subtype B, R5), and R3A (subtype B, R5X4) with mean 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) values of 3.3, 1.67, and 2.36 nm, respectively, whereas T1249-TRM had mean IC50 of 181.6, 41.73, and 10.83 nm, respectively. To develop a more efficient fusion inhibitor, we generated the lipopeptide LP-46 by replacing the TRM of T1249 with a C16 fatty acid, and its anti-HIV activity was then determined. Impressively, LP-46 inhibited NL4-3, JRCSF, and R3A with mean IC50 of 0.03, 0.05, and 0.06 nm, respectively, which were 110-, 33.4-, and 39.33-fold, respectively, lower than T1249. Moreover, a flexible linker (8-unit polyethylene glycol, PEG8) was introduced between the peptide sequence and the lipid moiety of LP-46; however, the resulting lipopeptide LP-47 showed an obviously reduced inhibitory activity, suggesting that a linker is not required for the antiviral activity of LP-46, similar to the T20-based lipopeptide LP-40.

Figure 2.

Inhibitory activities of T1249-based inhibitors against HIV-1 infection. A, inhibitory activities of inhibitors on HIV-1 NL4–3 (subtype B, X4). B, inhibitory activities of inhibitors on HIV-1 JRCSF (subtype B, R5). C, inhibitory activities of inhibitors on HIV-1 R3A (subtype B, R5X4). The experiments were performed in triplicate and repeated three times. The percentage inhibition of the inhibitors and IC50 values were calculated. Data are expressed as means ± S.D. (error bars). The solid lines represent sigmoidal non-linear regression analysis. The mean numbers are presented in parentheses for convenience.

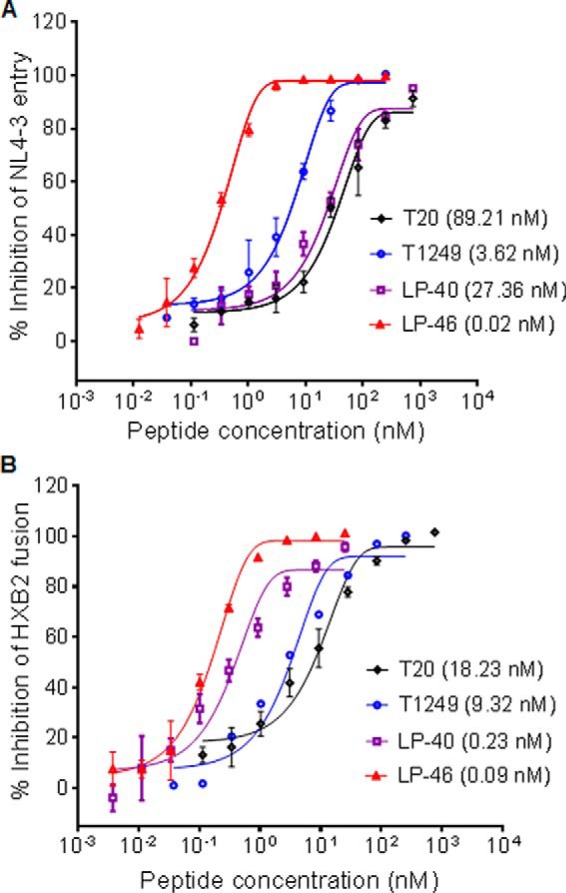

We further compared the inhibitory activities of T1249 and LP-46 against Env-mediated virus entry and cell-cell fusion. Here, T20 and LP-40 were included as controls. As shown in Fig. 3, LP-46 inhibited NL4-3 pseudovirus entry with a mean IC50 of 0.02 nm, which was 4460.5-fold lower than T20 (89.21 nm), 181-fold lower than T1249 (3.62 nm), and 1368-fold lower than LP-40 (27.36 nm). LP-46 inhibited HXB2 Env-mediated cell-cell fusion with a mean IC50 of 0.09 nm, which was 202.56-fold lower than T20 (18.23 nm), 103.56-fold lower than T1249 (9.32 nm), and 2.56-fold lower than LP-40 (0.23 nm). Meanwhile, the cytotoxicity of T1249 and LP-46 was determined, which indicated that both inhibitors had a 50% cytotoxic concentration (CC50) of greater than 140 μm, suggesting an extremely high therapeutic selectivity index (CC50/IC50 ratio).

Figure 3.

Inhibitory activities of LP-46 and control inhibitors against HIV-1–mediated cell entry and fusion. A, inhibitory activities of LP-46 and control inhibitors on NL4-3 pseudovirus. B, inhibitory activities of LP-46 and control inhibitors on HXB2 Env-mediated cell-cell fusion. The experiments were performed in triplicate and repeated three times. The percentage inhibition of the inhibitors and IC50 values were calculated. Data are expressed as means ± S.D. (error bars). The solid lines represent sigmoidal non-linear regression analysis. The mean numbers are presented in parentheses for convenience.

LP-46 is an exceptionally potent inhibitor of diverse primary HIV-1 subtypes

HIV-1 evolves with great genetic diversity and can be classified into multiple groups and subtypes, including the subtype A, B, and C viruses that dominate the AIDS epidemic worldwide and the recombinant viruses of CRF01A_E and CRF07B_C that are currently circulating in China. To further validate the antiviral activity of LP-46, we constructed a large group of pseudoviruses with diverse subtypes of viral Envs, including a so-called “global panel” recently selected based on the genetic and antigenic variability of the viral Envs representing the global AIDS epidemic (41). For comparison, the inhibitory activities of T20, T1249, and LP-40 were also determined by single-cycle infection assays. As shown in Table 1, LP-46 inhibited diverse HIV-1 isolates with a mean IC50 of 0.08 nm, which was 334.13-fold lower than T20 (26.73 nm), 43-fold lower than T1249 (3.44 nm), and 49.25-fold lower than LP-40 (3.94 nm).

Table 1.

Inhibitory activities of LP-46 and control peptides against primary HIV-1 isolates

A global panel of HIV-1 isolates representing the genetic and antigenic diversities worldwide was used. The assay was performed in triplicate and repeated three times. Data are expressed as means ± S.D.

| Primary Env | Subtype | IC50 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T20 | T1249 | LP-40 | LP-46 | ||

| nm | |||||

| 92RW020 | A | 2.03 ± 0.93 | 2.48 ± 0.04 | 1.2 ± 0.22 | 0.08 ± 0 |

| 92UG037.8 | A | 9.58 ± 3.85 | 2.93 ± 0.28 | 4.27 ± 2.16 | 0.06 ± 0 |

| 398-F1_F6_20 | A | 22.51 ± 7.17 | 1.36 ± 0.12 | 5.49 ± 0.77 | 0.03 ± 0 |

| AC10.0.29 | B | 1.86 ± 1.21 | 0.96 ± 0.11 | 1.35 ± 0.29 | 0.04 ± 0 |

| SC422661.8 | B | 13.26 ± 8.57 | 0.89 ± 0.1 | 15.08 ± 2.44 | 0.04 ± 0 |

| X2278_C2_B6 | B | 6.01 ± 1.24 | 2.74 ± 0.03 | 1.35 ± 0.44 | 0.03 ± 0 |

| TRO.11 | B | 7.4 ± 3.3 | 2.92 ± 0.11 | 2.03 ± 0.29 | 0.06 ± 0.02 |

| B02 | B′ | 11.69 ± 1.17 | 4.4 ± 0.08 | 1.01 ± 0.16 | 0.09 ± 0.01 |

| B04 | B′ | 5.05 ± 2.75 | 1.86 ± 0.27 | 1.34 ± 0.14 | 0.08 ± 0 |

| CAP45.2.00.G3 | C | 126.8 ± 28.83 | 2.48 ± 0.1 | 13.59 ± 1.39 | 0.07 ± 0.01 |

| ZM53M.PB12 | C | 16.66 ± 3.42 | 2.68 ± 0.28 | 3.39 ± 0.35 | 0.08 ± 0.01 |

| HIV_25710-2.43 | C | 11.88 ± 1.15 | 1.8 ± 0.01 | 4.82 ± 0.4 | 0.05 ± 0 |

| CE1176_A3 | C | 15.34 ± 11.54 | 3.83 ± 0.15 | 1.1 ± 0.28 | 0.08 ± 0 |

| CE703010217_B6 | C | 41.14 ± 7.57 | 2.52 ± 0.33 | 3.67 ± 0.5 | 0.06 ± 0.01 |

| X1632-S2-B10 | G | 10.09 ± 4.64 | 5.75 ± 0.3 | 1.57 ± 0.09 | 0.13 ± 0 |

| 246_F3_C10_2 | A/C | 33.81 ± 3.88 | 2.77 ± 0.32 | 7.99 ± 0.45 | 0.07 ± 0 |

| AE03 | CRF01_AE | 12.42 ± 3.51 | 3.22 ± 0.33 | 2.87 ± 0.45 | 0.1 ± 0 |

| AE04 | CRF01_AE | 21.16 ± 0.97 | 6.68 ± 0.18 | 2.43 ± 0.34 | 0.22 ± 0 |

| CNE8 | CRF01_AE | 20.66 ± 1.37 | 3.83 ± 0.18 | 3.69 ± 0.56 | 0.17 ± 0.01 |

| CNE55 | CRF01_AE | 24.55 ± 9.85 | 1.66 ± 0.11 | 1.91 ± 0.24 | 0.04 ± 0 |

| CH64.20 | CRF07_BC | 32.88 ± 5.3 | 2.42 ± 0.39 | 3.11 ± 0.12 | 0.06 ± 0 |

| CH070.1 | CRF07_BC | 136.65 ± 18.88 | 14.61 ± 0.76 | 3.55 ± 1.18 | 0.21 ± 0.01 |

| CH119.10 | CRF07_BC | 12.37 ± 7.23 | 0.88 ± 0.08 | 2.18 ± 0.33 | 0.04 ± 0 |

| CH120.6 | CRF07_BC | 59.06 ± 2.63 | 6.64 ± 0.33 | 3.87 ± 0.53 | 0.13 ± 0.01 |

| BJOX002000.03.2 | CRF07_BC | 13.48 ± 5.1 | 3.66 ± 0.17 | 5.71 ± 1.81 | 0.07 ± 0 |

| Mean | 26.73 | 3.44 | 3.94 | 0.08 | |

We previously found that T20 and LP-40 were more potent inhibitors of HIV-1 Env-mediated cell-cell fusion than of cell-free virus infection. Here, we were interested to determine the inhibitory activities of LP-46 and the control inhibitors against a panel of Envs by a dual split protein (DSP)-based cell-cell fusion assay. As shown in Table 2, T20 and LP-40 inhibited cell-cell fusion with mean IC50 of 11 and 0.25 nm, respectively, which were 2.43- and 15.76-fold lower, respectively, than their IC50 on pseudoviruses. Differently, T1249 and LP-46 showed mean IC50 of 8.69 and 0.16 nm, respectively, which were 2.53- and 2-fold higher, respectively, than their IC50 on pseudoviruses. Specifically, the IC50 of LP-46 was 68.75-fold lower than T20, 54.31-fold lower than T1249, and 1.56-fold lower than LP-40. Thus, LP-46 was also an exceptional potent inhibitor of cell-cell fusion but differed from LP-40, which had dramatically increased activities in inhibiting cell-cell fusion relative to its inhibition on pseudoviruses.

Table 2.

Inhibitory activities of LP-46 and control peptides on Env-mediated cell fusion

The assay was performed in triplicate and repeated three times. Data are expressed as means ± S.D.

| Primary Env | Subtype | IC50 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T20 | T1249 | LP-40 | LP-46 | ||

| nm | |||||

| 92RW020 | A | 0.93 ± 0.15 | 4.40 ± 0.36 | 0.03 ± 0.01 | 0.13 ± 0.11 |

| 92UG037.8 | A | 5.14 ± 0.12 | 2.63 ± 0.94 | 0.16 ± 0.01 | 0.06 ± 0.02 |

| 398-F1_F6_20 | A | 7.26 ± 0.77 | 6.47 ± 2.34 | 0.39 ± 0.03 | 0.07 ± 0.01 |

| AC10.0.29 | B | 5.41 ± 4.1 | 1.60 ± 0.01 | 0.06 ± 0.04 | 0.04 ± 0 |

| SC422661.8 | B | 2.11 ± 0.63 | 1.75 ± 1.62 | 0.13 ± 0.01 | 0.03 ± 0.02 |

| X2278_C2_B6 | B | 5.35 ± 0.18 | 3.30 ± 1.73 | 0.24 ± 0.06 | 0.05 ± 0.02 |

| TRO.11 | B | 18.45 ± 1.13 | 17.62 ± 8.2 | 0.64 ± 0.29 | 0.28 ± 0.06 |

| B02 | B′ | 5.17 ± 0.9 | 8.80 ± 6.48 | 0.09 ± 0.06 | 0.16 ± 0.13 |

| B04 | B′ | 9.50 ± 1.98 | 13.50 ± 6.63 | 0.14 ± 0.02 | 0.13 ± 0.11 |

| CAP45.2.00.G3 | C | 20.45 ± 9.71 | 21.48 ± 13.2 | 0.59 ± 0.17 | 0.39 ± 0.22 |

| ZM53M.PB12 | C | 37.11 ± 7.16 | 14.77 ± 2.29 | 0.32 ± 0.05 | 0.17 ± 0.18 |

| HIV_25710–2.43 | C | 15.79 ± 4.66 | 3.88 ± 0.18 | 0.09 ± 0.03 | 0.11 ± 0 |

| CE1176_A3 | C | 6.85 ± 1.42 | 5.53 ± 1.12 | 0.14 ± 0.01 | 0.25 ± 0.12 |

| CE703010217_B6 | C | 5.89 ± 0.47 | 4.42 ± 0.95 | 0.09 ± 0.01 | 0.12 ± 0.07 |

| X1632-S2-B10 | G | 10.36 ± 0.55 | 3.52 ± 0.88 | 0.29 ± 0.04 | 0.11 ± 0.07 |

| 246_F3_C10_2 | A/C | 4.74 ± 1.04 | 6.37 ± 0.5 | 0.13 ± 0.04 | 0.08 ± 0.05 |

| AE03 | CRF01_AE | 9.12 ± 1.74 | 20.77 ± 9.43 | 0.15 ± 0.04 | 0.34 ± 0.03 |

| AE04 | CRF01_AE | 8.78 ± 1.84 | 13.38 ± 2.77 | 0.27 ± 0.04 | 0.19 ± 0.06 |

| CNE8 | CRF01_AE | 42.54 ± 3.25 | 29.80 ± 19.13 | 0.30 ± 0.05 | 0.44 ± 0.06 |

| CNE55 | CRF01_AE | 11.09 ± 1.75 | 2.98 ± 1.2 | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 0.10 ± 0.01 |

| CH64.20 | CRF07_BC | 2.95 ± 0.4 | 2.09 ± 1.26 | 0.13 ± 0.01 | 0.06 ± 0 |

| CH070.1 | CRF07_BC | 24.85 ± 8.76 | 21.39 ± 9.68 | 1.60 ± 0.91 | 0.46 ± 0.36 |

| CH119.10 | CRF07_BC | 1.52 ± 0.52 | 1.58 ± 0.12 | 0.03 ± 0.01 | 0.03 ± 0.02 |

| CH120.6 | CRF07_BC | 10.26 ± 1.67 | 3.52 ± 1.24 | 0.15 ± 0.03 | 0.07 ± 0.06 |

| BJOX002000.03.2 | CRF07_BC | 3.47 ± 0.9 | 1.67 ± 0.65 | 0.09 ± 0.01 | 0.04 ± 0.02 |

| Mean | 11 | 8.69 | 0.25 | 0.16 | |

LP-46 is a highly potent inhibitor of T20-resistant mutants and HIV-2/SIV isolates

The emergence and spread of T20-resistant viruses significantly limit the clinical use of T20. Thus, we were intrigued to know the inhibitory activity of LP-46 against a panel of T20-resistant variants. HIV-1NL4-3 pseudoviruses carrying single or double T20-resistant mutations were produced and applied in single-cycle infection–based antiviral assays. As shown in Table 3, NL4–3D36G is referred to as a T20-sensitive virus because its WT virus inherited a naturally occurring aspartic acid at position 36 of gp41 that conferred high-level resistance to T20. Consistent with our previous results, LP-40 had no improvement or only minor improvement on the majority of the T20-resistant mutants (40). In sharp contrast, both T1249 and LP-46 exhibited highly potent activities in inhibiting diverse T20-resistant mutants. As compared with T1249, the inhibitory activity of LP-46 was greatly enhanced. For example, LP-46 inhibited NL4–3I37T with an IC50 of 0.13 nm, 36.46-fold lower than T1249 (4.74 nm) and 3194.38-fold lower than LP-40 (415.27 nm); LP-46 inhibited NL4–3I37T/N43K with an IC50 of 3.15 nm, 14.68-fold lower than T1249 (46.25 nm) and >634.92-fold lower than LP-40 (>2000 nm).

Table 3.

Inhibitory activity of LP-46 and control peptides on T20-resistant variants, HIV-2, and SIV isolates

The assay was performed in triplicate and repeated three times. Data are expressed as means ± S.D.

| Virus | IC50 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T20 | T1249 | LP-40 | LP-46 | |

| nm | ||||

| T20-sensitive | ||||

| NL4-3D36G | 7.52 ± 0.71 | 1.6 ± 0.29 | 0.5 ± 0.02 | 0.02 ± 0 |

| T20-resistant | ||||

| NL4-3WT | 116.23 ± 21.16 | 1.62 ± 0.27 | 36 ± 1.99 | 0.02 ± 0.01 |

| NL4-3I37T | 976.33 ± 206.78 | 4.74 ± 0.31 | 415.27 ± 70.24 | 0.13 ± 0.02 |

| NL4-3V38A | 2225 ± 530.98 | 7.82 ± 2.45 | 1548 ± 409.54 | 0.91 ± 0.02 |

| NL4-3V38M | 957.77 ± 371.69 | 4.63 ± 0.28 | 1368 ± 207.82 | 0.65 ± 0.01 |

| NL4-3Q40H | 1430.67 ± 244.66 | 4.61 ± 0.09 | 1814 ± 283.43 | 0.28 ± 0.15 |

| NL4-3N43K | 851.27 ± 37.67 | 4.49 ± 0.12 | 517.43 ± 72.71 | 0.25 ± 0.16 |

| NL4-3D36S/V38M | 388.20 ± 58.78 | 4.92 ± 0.38 | 1134.33 ± 167.82 | 0.44 ± 0.01 |

| NL4-3I37T/N43K | >2000 | 46.25 ± 1.96 | >2000 | 3.15 ± 0.21 |

| NL4-3V38A/N42T | >2000 | 36.17 ± 0.28 | >2000 | 3.75 ± 0.27 |

| HIV-2/SIV | ||||

| HIV-2ROD | 458.6 ± 41.28 | 21.95 ± 1.43 | 1566.33 ± 192.46 | 10.72 ± 1.78 |

| HIV-2ST | 1216 ± 135.5 | 31.88 ± 2.81 | >5000 | 15.95 ± 3.19 |

| SIV239 | 313.48 ± 22.53 | 1.94 ± 0.18 | 485.06 ± 13.69 | 0.01 ± 0 |

| SIVPBJ | 1225.75 ± 90.65 | 10.9 ± 1.64 | 2295.17 ± 279.47 | 0.4 ± 0.03 |

Next, we sought to determine the inhibitory activity of LP-46 against two replicative HIV-2 isolates (HIV-2ROD and HIV-2ST) and two SIV pseudoviruses (SIV239 and SIVPBJ). Consistent with our previous data (26), T20 showed poor activities, whereas T1249 possessed high potencies in inhibiting the four viruses (Table 3). As compared with T20, the activities of LP-40 on HIV-2/SIV did not increase rather than decrease; however, the inhibitory activities of LP-46 were significantly improved relative to T1249. Specifically, LP-46 inhibited HIV-2ROD, HIV-2ST, SIV239, and SIVPBJ with IC50 values of 10.9, 15.95, 0.01, and 0.4 nm, respectively, whereas T1249 had its IC50 values at 21.95, 31.88, 2.5, and 10.72 nm, respectively.

LP-46 and LP-40 display synergistic effects on viral entry and fusion

We previously showed that T20 and T1249 had no obvious synergistic anti-HIV effects (40), which contradicted the report by Pan et al. (42). Here, we were interested to know whether the two lipid derivatives had synergistic effects. To this end, both the pseudovirus-based single-cycle infection assay and the Env-based cell fusion assay were applied. As shown in Table 4, the combination of LP-40 and LP-46 resulted in synergism on a panel of pseudoviruses with different subtypes and phenotypes, with a mean combination index (CI) value of 0.56, and the mean dose reductions were 3.99-fold for LP-40 and 3.58-fold for LP-46. They also exhibited synergistic effects against Env-mediated cell-cell fusion with a mean CI of 0.67, and the mean dose reductions were 4.15-fold for LP-40 and 2.57-fold for LP-46. Therefore, these results confirmed the synergism between LP-40 and LP-46.

Table 4.

Synergistic effects of LP-40 and LP-46 in inhibiting HIV-1 Env-mediated viral entry and cell-cell fusion

The assay was performed in triplicate and repeated three times. Data are expressed as means.

| Env | Subtype | CI | LP-40 inhibition (IC50) |

LP-46 inhibition (IC50) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alone | In mixture | Dose reduction | Alone | In mixture | Dose reduction | |||

| nm | nm | n-fold | nm | nm | n-fold | |||

| Pseudovirus entry | ||||||||

| 92RW020 | A | 0.30 | 2.21 | 0.33 | 6.61 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 6.58 |

| 92UG037.8 | A | 0.56 | 5.64 | 1.58 | 3.56 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 3.55 |

| AC10.0.29 | B | 0.59 | 1.72 | 0.38 | 4.52 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 2.72 |

| X2278_C2_B6 | B | 0.54 | 2.77 | 0.78 | 3.54 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 3.93 |

| TRO.11 | B | 0.52 | 3.13 | 0.71 | 4.41 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 3.42 |

| NL4-3D36G | B | 0.71 | 1.41 | 0.49 | 2.91 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 2.72 |

| JRFL | B | 0.57 | 1.44 | 0.45 | 3.21 | 0.17 | 0.04 | 3.84 |

| SF162 | B | 0.60 | 4.45 | 1.3 | 3.42 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 3.28 |

| CE703010217_B6 | C | 0.72 | 5.91 | 1.63 | 3.63 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 2.23 |

| CE1176_A3 | C | 0.46 | 2.02 | 0.48 | 4.26 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 4.48 |

| X1632-S2-B10 | G | 0.64 | 2.37 | 0.62 | 3.80 | 0.17 | 0.06 | 2.69 |

| Mean | 0.56 | 3.01 | 0.8 | 3.99 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 3.58 | |

| Cell-cell fusion | ||||||||

| 398-F1_F6_20 | A | 0.77 | 0.12 | 0.04 | 3.00 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 2.00 |

| NL4–3D36G | B | 0.68 | 0.12 | 0.02 | 6.00 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 2.00 |

| JRFL | B | 0.55 | 0.15 | 0.04 | 3.75 | 0.15 | 0.04 | 3.75 |

| SF162 | B | 0.72 | 0.16 | 0.04 | 4.00 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 2.25 |

| CE703010217_B6 | C | 0.63 | 0.13 | 0.04 | 3.35 | 0.10 | 0.04 | 2.50 |

| 246_F3_C10_2 | A/C | 0.75 | 0.11 | 0.03 | 3.67 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 2.33 |

| Mean | 0.67 | 0.13 | 0.04 | 4.15 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 2.57 | |

LP-46 exhibits markedly increased helical stability and binding affinity with the target site

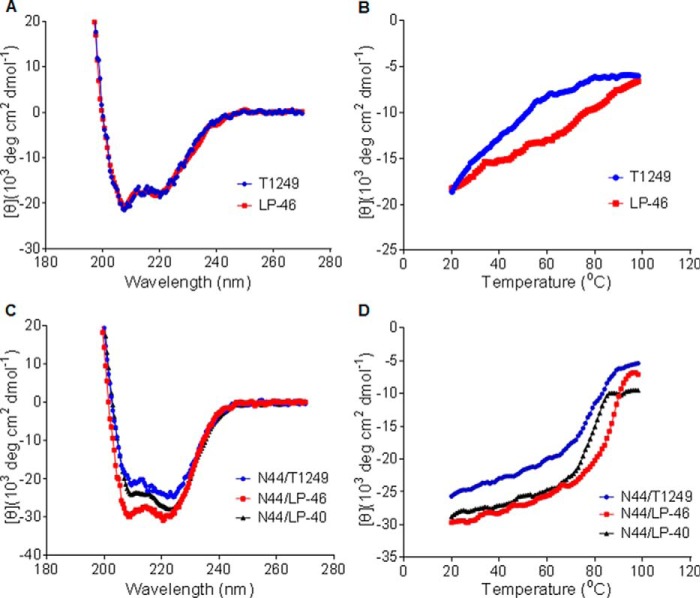

To understand the structural properties and its mechanism of action, we used CD spectroscopy to examine the secondary structure and thermal stability of T1249 and LP-46 in the absence or presence of a target mimic peptide. Different from T20 and LP-40, which are known to be unstructured in themselves, both the isolated T1249 and LP-46 displayed typical double minima at 208 and 222 nm (Fig. 4A), which indicated their α-helical characteristics. Although T1249 and LP-46 showed similar α-helical contents, LP-46 was more stable than T1249 as judged by their melting temperature curves (Fig. 4B). Then, we compared the interactions of T1249, LP-46, and LP-40 with a target mimic peptide (N44). It was found that both the N44/LP-46 and N44/LP-40 complexes displayed markedly increased α-helicity and thermostability compared with the N44/T1249 complex (Fig. 4, C and D). Specifically, the N44/LP-46 complex showed an α-helical content of 89.62% and a Tm of 87.09 °C, the N44/LP-40 complex showed an α-helical content of 83.81% and a Tm of 81.1 °C, and the N44/T1249 complex showed an α-helical content of 74.99% and a Tm of 78.05 °C.

Figure 4.

Secondary structure and stability of LP-46 determined by CD spectroscopy. The α-helicity (A) and thermostability (B) of the isolated T1249 and LP-46 were measured in PBS, with a final concentration of inhibitor at 20 μm. The α-helicity (C) and thermostability (D) of T1249, LP-46, and LP-40 in complexes with the NHR-derived peptide N44 were measured in deionized water, with the final concentration of each inhibitor at 10 μm. The experiments were performed two times, and representative data are shown.

Structural insights into the mechanism of action of LP-46

To elucidate the structural properties of LP-46 and its precise binding mode with the target site, we performed crystallographic studies of its complex with the NHR-derived peptide N44. The crystal of the N44/LP-46 complex belonged to the space group of P1, contained six pairs of N44/LP-46 peptides (two complete 6-HBs) per asymmetric unit, and diffracted X-rays to a resolution of 2.0 Å. Although the crystal structure had relatively high quality, we could not observe the fatty acid group at the C terminus of LP-46, probably due to its flexible character. Other than that, we could build all of the important residues of LP-46/N44 peptides in the electron density map. The refined model has good refinement statistics and stereochemistry qualities (Table 5).

Table 5.

Crystallographic data collection and refinement statistics for N44/LP-46

Rwork and Rfree are defined by r = Σhkl‖Fobs| − |Fcalc‖/Σhkl|Fobs|, where h, k, and l are the indices of the reflections (used in refinement for Rwork; 5%, not used in refinement for Rfree) and Fobs and Fcalc are the structure factors, deduced from intensities and calculated from the model, respectively. RMSD, root mean square deviation. Values in parentheses are for the highest-resolution shell.

| Data collection | |

| Beamline | SSRF BL17U |

| Wavelength | 0.9796 Å |

| Resolution range | 27.1–2.0 (2.072–2.0) |

| Space group | P 1 |

| Unit cell | 34.09 53.26 59.34 94.42 96.52 90.02 |

| Redundancy | 2 |

| Total reflections | 52,201 |

| Unique reflections | 26,727 (2579) |

| Completeness (%) | 96 (95) |

| Rmerge (%) | 8.0 (41.5) |

| I/σI | 12.3 (2.0) |

| Refinement | |

| Reflections used in refinement | 26,691 |

| Rwork | 0.220 |

| Rfree | 0.256 |

| No. of non-hydrogen atoms | 3846 |

| Macromolecules | 3652 |

| Protein residues | 433 |

| RMSD bonds (Å) | 0.003 |

| RMSD angles (degrees) | 0.44 |

| Ramachandran favored (%) | 99.52 |

| Ramachandran allowed (%) | 0.48 |

| Ramachandran outliers (%) | 0 |

| Rotamer outliers (%) | 4.1 |

| Clashscore | 7.71 |

| Average B-factor (Å2) | 32.46 |

| Macromolecules | 32.27 |

| Solvent | 36.05 |

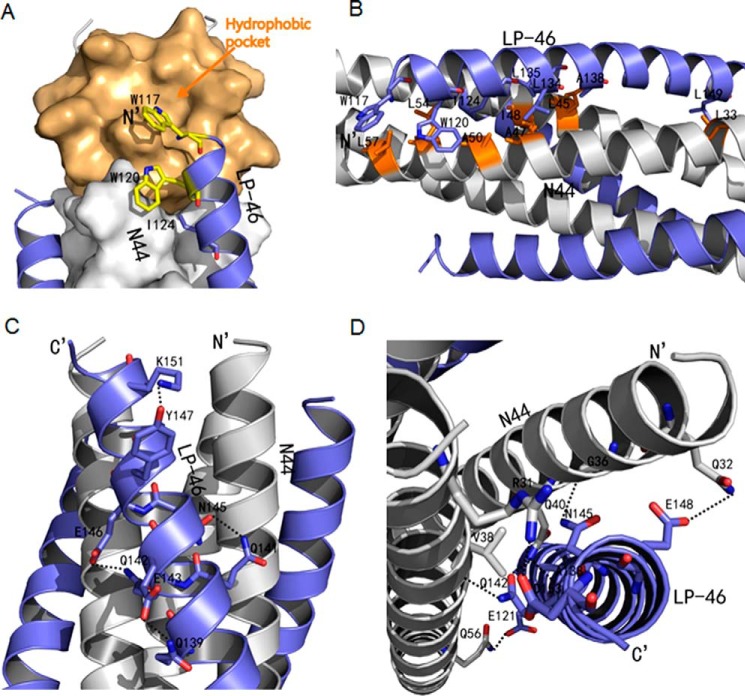

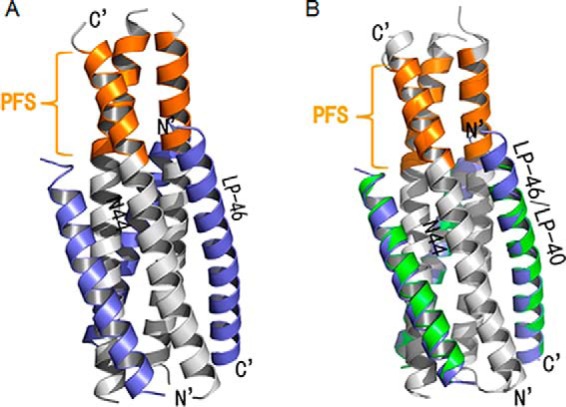

Similar to other structures of the HIV gp41 core, LP-46 and N44 formed a typical 6-HB conformation, in which three N44 helices formed an interior, trimeric coiled-coil with three conserved, hydrophobic grooves and three LP-46 helices packed into each of the grooves antiparallely in a left-handed direction around the outside of the central trimer (Fig. 5A). Surprisingly, the introduced PBD at the N terminus of LP-46 did not insert into the hydrophobic NHR pocket as expected, but aligned to the continuous NHR sequence bound by the C-terminal portion of the inhibitor. Indeed, the binding footprint of LP-46 was almost identical to that of LP-40, and the two lipopeptides could be finely overlaid together (Fig. 5B). Specifically, Trp-117, the first N-terminal residue of LP-46, had hydrophobic interactions with the residues Leu-57 and Leu-54 at the rim of the pocket; Trp-120 of LP-46, the position corresponding to the first residue (Tyr-127) of LP-40, contacted Leu-57; and Ile-124, corresponding to the Ile-131 of LP-40, contacted Ala-50 (Fig. 6, A and B). The downstream interhelical interactions between hydrophobic residues, such as Leu-134/Ala-47, Leu-135/Ile-48, Ala-138/Leu-45, and Leu-149/Leu-33, also played critical roles in the binding stability of the inhibitors.

Figure 5.

Crystal structure of 6-HB formed by N44 and LP-46. A, the crystal structure of N44/LP-46 is presented in ribbon models vertically by PyMOL. N44 peptides are colored in gray with the PFS marked in orange, and LP-46 inhibitors are colored in slate. B, comparison of the binding footprints of LP-46 and LP-40 with N44 by superimposing. The LP-46 inhibitors are colored slate, whereas the LP-40 inhibitors are colored green. Both the N and C termini of N44 and inhibitors are labeled.

Figure 6.

Interactions between N44 and LP-46. A, binding of the introduced pocket-binding sequence in LP-46 with the NHR pocket site. The N44 trimer is shown as a surface model in gray with the pocket region marked in light orange. LP-46 inhibitors are shown as ribbon models and colored in slate. Residues related to hydrophobic interactions in LP-46 are shown as stick models in yellow. B, hydrophobic contacts of LP-46 with the N44 helices in ribbon models. The N44 peptides are colored in gray with the residues related to hydrophobic interactions marked in orange, whereas the LP-46 inhibitors are in slate. C, intrahelical bonds in the LP-46 helix. The N44 helices are colored in gray, and the LP-46 inhibitors are colored in slate. The residues involving hydrogen bond formation are shown as stick models with labels. Hydrogen bonds are indicated in dashed black lines. D, interhelical bonds between N44 and LP-46. The N44 helices are colored in gray, and the LP-46 inhibitors are colored in slate. The residues involved in interhelical hydrogen bond formation are shown as stick models with labels. Hydrogen bonds are indicated in dashed black lines.

There were multiple intrahelical hydrogen bonds on LP-46 critically stabilizing the α-helical structure. As shown in Fig. 6C, the Nϵ2 atom of Gln-139 formed a hydrogen bond with the Oϵ2 atom of Glu-143; the Nϵ2 atom of Gln-141 donated a hydrogen bond to the Oδ1 atom of Asn-145; the Oϵ2 atom of Glu-146 accepted a hydrogen bond from the Nϵ2 atom of Gln-142; and the OH group of Tyr-147 accepted a hydrogen bond from the Nζ atom of Lys-151. More importantly, a mass of interhelical hydrogen bonds made the structure of the N44/LP-46 complex extremely stable (Fig. 6D). For instance, the Oϵ2 atom of Glu-121 formed a hydrogen bond with the Oϵ1 atom of Gln-56; the Nϵ2 atom of Gln-142 donated a hydrogen bond to the O atom of Val-38 while its Oϵ1 atom accepted a hydrogen bond from the Nϵ2 atom of Gln-40; and interestingly, the O atom of Ala-138 accepted a hydrogen bond from the Nϵ2 atom of Gln-40, thus forming a hand in hand conformation. At the C-terminal portion of LP-46, the Nδ2 atom of Asn-145 donated a hydrogen bond to the O atom of Gly-36; the Oϵ2 atom of Glu-148 accepted a hydrogen bond from the Nϵ2 atom of Gln-32; and the Oδ1 atom of Asp-153 accepted a hydrogen bond from the Nη1 atom of Arg-31, which strengthened the binding force of the inhibitors.

Discussion

In this study, we focused on developing a more potent and broad HIV fusion inhibitor by using T1249 as a template, with aims to overcome the problems of T20 and its lipid derivative LP-40. First, we verified the importance of the C-terminal tryptophan-rich motif in T1249, created a T1249-based lipopeptide inhibitor termed LP-46, and demonstrated that introducing a flexible linker could not increase but rather impaired the antiviral activity of LP-46. Then we showed LP-46 with dramatically increased α-helical stability, binding affinity, and antiviral activity. Promisingly, it was able to efficiently inhibit diverse HIV-1, HIV-2, SIV, and T20-resistant mutants and displayed synergistic effects with LP-40. We determined the crystal structure of LP-46 in complex with a target mimic peptide, which revealed the critical binding motifs of LP-46 underlying its mechanism of action. Especially, the structure clarified that the introduced N-terminal PBD of LP-46 did not interact with the gp41 pocket as expected; instead, it adopted a manner similar to that of LP-40. Taken together, the present studies have provided important information for understanding the structure-activity relationship of viral fusion inhibitors and offered an excellent candidate for developing an anti-HIV-1/2 and even anti-SIV drug.

The clinical use of T20 has been challenged by its multiple drawbacks, including the low genetic barrier for drug resistance, poor bioavailability, and dramatically decreased activity on HIV-2 isolates (17, 18, 43). As a second-generation fusion inhibitor, T1249 was designed with a chimeric amino acid sequence derived from the consensus CHR sequences of HIV-1, HIV-2, and SIV; thus, it showed potent activities on HIV-1, HIV-2, and T20-resistant viruses; however, its clinical development was stopped due to the formulation problems associated with the large size, calling for a significant optimization. Currently, two design strategies have been widely applied for the development of peptide-based viral fusion inhibitors with improved pharmaceutical profiles. First, a number of new fusion inhibitors have been generated through engineering the peptide sequences, such as T1249 (29), T2635 (44), sifuvirtide (45), SC34EK (46), and CP32M (47). Without exception, the N-terminals of these inhibitors contain a PBD, which is not included in T20. Recently, the M-T hook structure has been applied to develop short peptides that mainly target the pocket site, resulting in the inhibitors with markedly improved binding and inhibitory activities, such as MT-SC22EK (48), HP23 (49), and 2P23 (26). The second strategy is conjugating the peptides with different classes of lipids, generating a group of lipopeptides with dramatically increased antiviral activities and extended half-lives, such as C34-Chol (34), sphinganine-N17 (38), HIVP4 (35), LP-11 (36), LP-19 (37), and LP-40 (40). As a T20-based lipopeptide, LP-40 showed improvements over its template, including the significantly increased activity on HIV-1 and synergistic effect with LP-11; however, LP-40 remained poorly active on T20-resistant mutants and HIV-2 isolates. Therefore, we decided to develop a T1249-based lipopeptide with the aim of overcoming the defects of T20, T1249, and LP-40. As anticipated, LP-46 had dramatically increased antiviral activities, with the IC50 values approaching low picomolar concentrations on diverse HIV-1 isolates. Also, it was much better than T20, T1249, and LP-40 in inhibiting HIV-2 and SIV isolates. Interestingly, our studies demonstrated that LP-40 and LP-46 exhibited a synergistic anti-HIV activity, which was different from their templates, T20 and T1249, which did not show obvious synergistic effects (40). Therefore, it will be helpful to characterize the mechanisms underlying the differences between the conjugated and unconjugated inhibitors.

Although T20 was found over 20 years ago, its mechanism of action remains elusive, and structural information is lacking. We recently obtained the crystal structure of LP-40 in complex with the target mimic peptide N44, which provided important information for elucidating the mechanisms of T20 and LP-40 (40). Similarly, little information is currently available about the structural properties of T1249. In this study, we first determined the secondary structure and thermal stability of T1249 and LP-46 by CD spectroscopy. Unlike T20 and LP-40, which are unstructured in isolation, our results demonstrated that both the isolated T1249 and LP-46 adopted typical α-helical conformations. Obviously, LP-46 was more stable than T1249, and it had greatly enhanced binding affinity either. Before a crystal structure was available, we were wondering how T1249 interacted with the NHR target in terms of its discontinuous sequence, and thus we had proposed three binding modes for T1249 and LP-46 based on the rationale of the coiled-coil interactions in a helical wheel (Fig. S1). In binding mode I, the N-terminal PBD of LP-46 inserted into the deep pocket of the NHR helices to make extensive hydrophobic interactions like that of other CHR-derived peptide inhibitors, whereas its C-terminal sequence interacted with the counterpart located upstream of the NHR helices. In such a manner, it was conceivable that the unmatched sequence between the NHR upstream and the pocket site was not targeted by the inhibitor and thus might protrude out. In binding mode II, the large C-terminal portion of LP-46 bound the NHR upstream to dominate the helical interactions, resulting, and as a result, its PBD could not insert into the pocket as expected. Binding mode III was the least likely possibility, in which the PBD of LP-46 inserted regularly into the pocket, whereas its large C-terminal sequence was pulled down to align with the NHR sequence neighboring the pocket. In both mode II and III, it was very interesting to know how the unusual matched residues interacted with each other, thus determining the high binding and antiviral activities of inhibitors. Unexpectedly, the crystal structure of LP-46 in complex with N44 demonstrated that LP-46 bound to the NHR as a proposed binding model II, in which the C-terminal portion of the inhibitor aligned well with the NHR upstream and pulled its PBD to the pocket upstream, similar to the binding mode of the N-terminal segment of LP-40. Therefore, the crystal structure has provided new insights into the mechanisms of action of T1249 and LP-46 and will definitely guide the design of novel fusion inhibitors with potent and broad anti-HIV activities.

Experimental procedures

Cell lines and plasmids

The following reagents were obtained through the AIDS Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, National Institutes of Health: TZM-bl indicator cells, which stably express large amounts of CD4 and CCR5, along with endogenously expressed CXCR4 (from John C. Kappes and Xiaoyun Wu); HL2/3 cells, which contain stably integrated copies of the HIV-1 molecular clone HXB2/3gpt that express high levels of HIV Gag, Env, Tat, Rev, and Nef proteins (from Barbara K. Felber and George N. Pavlakis); U87 CD4+CCR5+ cells stably transduced to express CD4 and CCR5 (from Hongkui Deng and Dan R. Littman); the Panel of Global HIV-1 Env Clones, which contains 12 envelope clones as reference strains representing the global epidemic (from David Montefiori); the molecular clone of HIV-1 NL4-3 (from Malcolm Martin); the molecular clone of HIV-1 JRCSF (from Irvin S. Y. Chen and Yoshio Koyanagi); and the molecular clone of HIV-2 ST (from Beatrice Hahn and George Shaw). A molecular clone of HIV-2 strain ROD was kindly provided by Nuno Taveira (Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Lisbon, Portugal). Two plasmids encoding SIV Env (pSIVpbj-Env and pSIV239-Env) were kindly provided by Jianqing Xu (Shanghai Public Health Clinical Center and Institutes of Biomedical Sciences, Fudan University, China). The plasmids DSP1–7 and DSP8–11 for the DSP-based fusion assay were provided by Zene Matsuda (Institute of Medical Science of the University of Tokyo, Japan).

Peptide synthesis and lipid conjugation

Peptides were synthesized on Rink amide 4-methylbenzhydrylamine resin by using a standard solid-phase Fmoc (N-(9-fluorenyl)methoxycarbonyl ) method as described previously (36). All peptides were acetylated at the N terminus and amidated at the C-terminal. For synthesizing a lipopeptide (LP-40, LP-46, or LP-47), the template peptide contains lysine residue at its C terminus with a 1-(4,4-dimethyl-2,6-dioxocyclohexylidene)ethyl side chain–protecting group, enabling the conjugation of a fatty acid (C16) that requires a deprotection step in a solution of 2% hydrazinehydrate-N,N-dimethylformamide (36). Peptides were purified by reverse-phase HPLC to >95% homogeneity and were characterized by mass spectrometry. The concentrations of the peptides were measured by UV absorbance (A280) and a theoretically calculated molar extinction coefficient based on the tryptophan and tyrosine residues.

Inhibition of replicative HIV-1 and HIV-2 isolates

Inhibition of peptides on replication-competent HIV-1 (NL4–3, JRCSF, and R3A) and HIV-2 (ROD and ST) isolates was determined as described previously (37). Briefly, the plasmids were transfected into HEK239T cells (American Type Culture Collection; Manassas, VA), and virus stocks were harvested and quantified 48 h post-transfection. A total of 100 50% tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50) viruses was used to infect TZM-bl cells in the presence or absence of serially 3-fold diluted peptides. Cells were harvested 2 days postinfection and lysed in cell lysis buffer, and luciferase activity was measured. The assays were performed in triplicate and repeated three times. The percentage inhibition and IC50 values were calculated using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA).

Single-cycle infection–based antiviral assay

Inhibition of peptides on HIV-1 or HIV-2 Env-mediated entry was determined by a single-cycle infection assay as described previously (50). Briefly, pseudoviruses were generated via cotransfection of HEK293T cells with an Env-expressing plasmid and a backbone plasmid pSG3Δenv that encoded Env-defective, luciferase-expressing HIV-1 genome. Supernatants were harvested 48 h after transfection, and the TCID50 was determined in TZM-bl cells. Peptides were prepared in 3-fold dilutions and mixed with 100 TCID50 viruses and then incubated for 1 h at room temperature. The mixture was added to TZM-bl cells (104/well) in triplicate and incubated for 48 h at 37 °C, and luciferase activity was measured. The assays were performed in triplicate and repeated three times, and the percentage inhibition and IC50 values were calculated with GraphPad Prism.

Cell-cell fusion assays

Inhibition of peptides on HIV-1HXB2 Env-mediated cell-cell fusion was measured using a reporter gene assay based on the activation of an HIV long terminal repeat–driven luciferase cassette in TZM-bl cells (target) by HIV-1 tat from HL2/3 cells (effector) (48). TZM-bl cells were seeded in 96-well plates (1 × 104/well) and incubated at 37 °C overnight. The target cells were cocultured with HL2/3 cells (3 × 104/well) for 6 h at 37 °C in the presence or absence of serially 3-fold diluted inhibitors. Luciferase activity was measured using luciferase assay regents and a luminescence counter (Promega, Madison, WI). A DSP-based fusion assay was also conducted to determine the inhibitory activity of peptides, as described previously (51, 52). Briefly, a total of 1.5 × 104 HEK293T cells (effector cells) were seeded on 96-well plates, and a total of 8 × 104 U87 CD4+CCR5+ cells (target cells) were seeded on a 24-well plate. On the following day, the effector cells were transfected with a mixture of an Env-expressing plasmid and a DSP1–7 plasmid, and the target cells were transfected with a DSP8–11 plasmid. Forty-eight hours post-transfection, the target cells were resuspended in 300 μl of prewarmed culture medium, and 0.05 μl of EnduRen live cell substrate (Promega) was added to each well. Then aliquots of 75 μl of the target cell suspension were transferred over each well of the effector cells in the presence or absence of a test inhibitor at graded concentrations. The cells were then spun down to maximize cell-cell contact and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C, and then luciferase activity was measured. Both fusion assays were performed in triplicate and repeated three times, and the percentage inhibition and IC50 values were calculated using GraphPad Prism.

Cytotoxicity assay

The cytotoxicity of T1249 and LP-46 on TZM-bl cells was measured using a CellTiter 96 AQueous One Solution Cell proliferation assay (Promega). In brief, 50 μl of peptides at graded concentrations was added to TZM-bl cells, which were seeded on a 96-well tissue culture plate (1 × 104 cells/well). After incubation at 37 °C for 2 days, 20 μl of CellTiter 96® AQueous One Solution Reagent was pipetted into each well and further incubated at 37 °C for 2 h. The absorbance was measured at 490 nm using a SpectraMax M5 microplate reader.

CD spectroscopy

The α-helicity and thermostability of inhibitors in the presence or absence of a target mimic peptide (N44) were determined by CD spectroscopy, as described previously (36). The peptides were desolved in PBS (pH 7.2) or double-distilled and deionized water and incubated for 30 min at 37 °C. CD spectra were acquired on a Jasco spectropolarimeter (model J-815) using a 1-nm bandwidth with a 1-nm step resolution from 195 to 260 nm at room temperature. Spectra were corrected by subtraction of a solvent blank. The α-helical content was calculated from the CD signal by dividing the mean residue ellipticity [θ] at 222 nm by the value expected for 100% helix formation (−33,000 degrees cm2 dmol−1). Thermal denaturation was conducted by monitoring the ellipticity change at 222 nm from 20 to 98 °C at a rate of 1.2 °C/min, and Tm is defined as the midpoint of the thermal unfolding transition.

Synergistic effects of inhibitors

The synergistic effects of two inhibitors (LP-40 and LP-46) on HIV-1 Env-based pseudoviruses and cell-cell fusion were determined by a single-cycle infection assay and a DSP-based cell fusion assay, respectively, as described above. Peptides were tested individually and in combination at a fixed molar ratio, which was based on the IC50 of single drugs that were tested separately over a range of serial dilutions. The inhibition data were analyzed for cooperative effects by using the method of Chou and Talalay (53, 54). The analysis was conducted in a stepwise fashion by calculating IC50 values based on the dose-response curves of single drugs that were tested separately and two drugs tested in combination. Then the CI was calculated by using the median effect equation with the CalcuSyn program to assess the synergistic effect of combinations. A CI of <1 indicates synergism (CI values were interpreted as follows: 0.1, very strong synergism; 0.1–0.3, strong synergism; 0.3–0.7, synergism; 0.7–0.85, moderate synergism; and 0.85–0.90, slight synergism), a CI of 1 or close to 1 indicates additive effects, and a CI of >1 indicates antagonism. Dose reduction was calculated by dividing the IC50 value of a peptide when it was tested alone by that of the same peptide tested in combination with another peptide(s).

Assembly and crystallization of the N44/LP-46 complex

The N44/LP-46 complex was assembled by dissolving equal amounts (1:1 molecular ratio) of the peptides (N44 and LP-46) in denaturing buffer (100 mm NaH2PO4, 10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 8 m urea). To refold the peptides, the mixture was dialyzed against buffer containing 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 100 mm NaCl at 4 °C overnight. The dialyzed sample was concentrated by centrifugation and then subjected to a size-exclusion chromatography column (Superdex 75 10/300 GL, GE Healthcare). An elution corresponding to the molecular weight of 6-HB was collected and concentrated before the crystallization trials. The N44/LP-46 complex was crystallized by mixing equal volumes (0.2 μl) of purified peptide complex (∼10 mg/ml) and reservoir solution (0.1 m Tris-HCl, pH 8.5, 10% (w/v) PEG4000) in a sitting drop vapor diffusion system at 18 °C. Cryocooling of the crystals was achieved by soaking the crystal for 5 s in reservoir solution containing 30% glycerol (v/v) followed by flash freezing to 100 K in liquid nitrogen. All data sets were collected on beamline BL17U at the Shanghai Synchrotron Research Facility and processed with the program HKL2000 (55). All data collection and processing statistics are listed in Table 5.

Structural determination and refinement

The crystal structure of N44/LP-46 was solved by molecular replacement with the crystallographic software PHASER (56). The search model was the gp41 core structure (Protein Data Bank accession number 1AIK). Iterative refinement with the program PHENIX and model building with the program COOT were performed to complete the structure refinement (57, 58). Structure validation was performed with the program PROCHECK (59), and all structural figures were generated with PyMOL.

Author contributions

Y. Z., X. Z., X. D., H. C., S. C., J. H., and X. W. investigation; Y. Z., X. Z., X. D., H. C., S. C., J. H., and X. W. methodology; Y. H. conceptualization; Y. H. supervision; Y. H. funding acquisition; Y. H. writing-original draft; Y. H. project administration.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Zene Matsuda (Institute of Medical Science of the University of Tokyo) for providing the DSP plasmids and the scientists at beamline BL17U (Shanghai Synchrotron Research Facility) for assistance in diffraction data collection.

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China Grants 81630061, 81473255, and 81673484 and Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (CAMS) Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences Grant 2017-I2M-1-014. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

This article contains Fig. S1.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (code 5YC0) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (http://wwpdb.org/).

- Env

- envelope

- CHR

- C-terminal heptad repeat(s)

- NHR

- N-terminal heptad repeat

- 6-HB

- six-helix bundle

- PBD

- pocket-binding domain

- TRM

- tryptophan-rich motif

- DSP

- dual split protein

- CI

- combination index

- SIV

- simian immunodeficiency virus.

References

- 1. Colman P. M., and Lawrence M. C. (2003) The structural biology of type I viral membrane fusion. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 4, 309–319 10.1038/nrm1076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Eckert D. M., and Kim P. S. (2001) Mechanisms of viral membrane fusion and its inhibition. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 70, 777–810 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yahi N., Fantini J., Baghdiguian S., Mabrouk K., Tamalet C., Rochat H., Van Rietschoten J., and Sabatier J. M. (1995) SPC3, a synthetic peptide derived from the V3 domain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) gp120, inhibits HIV-1 entry into CD4+ and CD4− cells by two distinct mechanisms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 4867–4871 10.1073/pnas.92.11.4867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chan D. C., Fass D., Berger J. M., and Kim P. S. (1997) Core structure of gp41 from the HIV envelope glycoprotein. Cell 89, 263–273 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80205-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tan K., Liu J., Wang J., Shen S., and Lu M. (1997) Atomic structure of a thermostable subdomain of HIV-1 gp41. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 12303–12308 10.1073/pnas.94.23.12303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Weissenhorn W., Dessen A., Harrison S. C., Skehel J. J., and Wiley D. C. (1997) Atomic structure of the ectodomain from HIV-1 gp41. Nature 387, 426–430 10.1038/387426a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chan D. C., Chutkowski C. T., and Kim P. S. (1998) Evidence that a prominent cavity in the coiled coil of HIV type 1 gp41 is an attractive drug target. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 15613–15617 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Qiu Z., Chong H., Yao X., Su Y., Cui S., and He Y. (2015) Identification and characterization of a subpocket on the N-trimer of HIV-1 Gp41: implication for viral entry and drug target. AIDS 29, 1015–1024 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Crespillo S., Caḿara-Artigas A., Casares S., Morel B., Cobos E. S., Mateo P. L., Mouz N., Martin C. E., Roger M. G., El Habib R., Su B., Moog C., and Conejero-Lara F. (2014) Single-chain protein mimetics of the N-terminal heptad-repeat region of gp41 with potential as anti-HIV-1 drugs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 18207–18212 10.1073/pnas.1413592112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chu S., and Gochin M. (2013) Identification of fragments targeting an alternative pocket on HIV-1 gp41 by NMR screening and similarity searching. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 23, 5114–5118 10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.07.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chan D. C., and Kim P. S. (1998) HIV entry and its inhibition. Cell 93, 681–684 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81430-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Weng Y., and Weiss C. D. (1998) Mutational analysis of residues in the coiled-coil domain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 transmembrane protein gp41. J. Virol. 72, 9676–9682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wild C. T., Shugars D. C., Greenwell T. K., McDanal C. B., and Matthews T. J. (1994) Peptides corresponding to a predictive α-helical domain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp41 are potent inhibitors of virus infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 91, 9770–9774 10.1073/pnas.91.21.9770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wild C., Greenwell T., and Matthews T. (1993) A synthetic peptide from HIV-1 gp41 is a potent inhibitor of virus-mediated cell-cell fusion. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 9, 1051–1053 10.1089/aid.1993.9.1051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jiang S., Lin K., Strick N., and Neurath A. R. (1993) HIV-1 inhibition by a peptide. Nature 365, 113 10.1038/365113a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Furuta R. A., Wild C. T., Weng Y., and Weiss C. D. (1998) Capture of an early fusion-active conformation of HIV-1 gp41. Nat. Struct. Biol. 5, 276–279 10.1038/nsb0498-276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. He Y. (2013) Synthesized peptide inhibitors of HIV-1 gp41-dependent membrane fusion. Curr. Pharm. Des. 19, 1800–1809 10.2174/1381612811319100004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Eggink D., Berkhout B., and Sanders R. W. (2010) Inhibition of HIV-1 by fusion inhibitors. Curr. Pharm. Des. 16, 3716–3728 10.2174/138161210794079218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rimsky L. T., Shugars D. C., and Matthews T. J. (1998) Determinants of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 resistance to gp41-derived inhibitory peptides. J. Virol. 72, 986–993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Baldwin C. E., Sanders R. W., Deng Y., Jurriaans S., Lange J. M., Lu M., and Berkhout B. (2004) Emergence of a drug-dependent human immunodeficiency virus type 1 variant during therapy with the T20 fusion inhibitor. J. Virol. 78, 12428–12437 10.1128/JVI.78.22.12428-12437.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Greenberg M. L., and Cammack N. (2004) Resistance to enfuvirtide, the first HIV fusion inhibitor. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 54, 333–340 10.1093/jac/dkh330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Berkhout B., Eggink D., and Sanders R. W. (2012) Is there a future for antiviral fusion inhibitors? Curr. Opin. Virol. 2, 50–59 10.1016/j.coviro.2012.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Xu L., Pozniak A., Wildfire A., Stanfield-Oakley S. A., Mosier S. M., Ratcliffe D., Workman J., Joall A., Myers R., Smit E., Cane P. A., Greenberg M. L., and Pillay D. (2005) Emergence and evolution of enfuvirtide resistance following long-term therapy involves heptad repeat 2 mutations within gp41. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49, 1113–1119 10.1128/AAC.49.3.1113-1119.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Witvrouw M., Pannecouque C., Switzer W. M., Folks T. M., De Clercq E., and Heneine W. (2004) Susceptibility of HIV-2, SIV and SHIV to various anti-HIV-1 compounds: implications for treatment and postexposure prophylaxis. Antivir. Ther. 9, 57–65 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Borrego P., Calado R., Marcelino J. M., Pereira P., Quintas A., Barroso H., and Taveira N. (2013) An ancestral HIV-2/simian immunodeficiency virus peptide with potent HIV-1 and HIV-2 fusion inhibitor activity. AIDS 27, 1081–1090 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32835edc1d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Xiong S., Borrego P., Ding X., Zhu Y., Martins A., Chong H., Taveira N., and He Y. (2017) A helical short-peptide fusion inhibitor with highly potent activity against human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1), HIV-2, and simian immunodeficiency virus. J. Virol. 91, e01839–01816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. de Silva T. I., Cotten M., and Rowland-Jones S. L. (2008) HIV-2: the forgotten AIDS virus. Trends Microbiol. 16, 588–595 10.1016/j.tim.2008.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lalezari J. P., Bellos N. C., Sathasivam K., Richmond G. J., Cohen C. J., Myers R. A. Jr., Henry D. H., Raskino C., Melby T., Murchison H., Zhang Y., Spence R., Greenberg M. L., Demasi R. A., Miralles G. D., and T1249-102 Study Group (2005) T-1249 retains potent antiretroviral activity in patients who had experienced virological failure while on an enfuvirtide-containing treatment regimen. J. Infect. Dis. 191, 1155–1163 10.1086/427993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Eron J. J., Gulick R. M., Bartlett J. A., Merigan T., Arduino R., Kilby J. M., Yangco B., Diers A., Drobnes C., DeMasi R., Greenberg M., Melby T., Raskino C., Rusnak P., Zhang Y., et al. (2004) Short-term safety and antiretroviral activity of T-1249, a second-generation fusion inhibitor of HIV. J. Infect. Dis. 189, 1075–1083 10.1086/381707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Eggink D., Baldwin C. E., Deng Y., Langedijk J. P., Lu M., Sanders R. W., and Berkhout B. (2008) Selection of T1249-resistant human immunodeficiency virus type 1 variants. J. Virol. 82, 6678–6688 10.1128/JVI.00352-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Peterson K., and Rowland-Jones S. (2012) Novel agents for the treatment of HIV-2 infection. Antiviral Ther. 17, 435–438 10.3851/IMP2031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hildinger M., Dittmar M. T., Schult-Dietrich P., Fehse B., Schnierle B. S., Thaler S., Stiegler G., Welker R., and von Laer D. (2001) Membrane-anchored peptide inhibits human immunodeficiency virus entry. J. Virol. 75, 3038–3042 10.1128/JVI.75.6.3038-3042.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Egelhofer M., Brandenburg G., Martinius H., Schult-Dietrich P., Melikyan G., Kunert R., Baum C., Choi I., Alexandrov A., and von Laer D. (2004) Inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 entry in cells expressing gp41-derived peptides. J. Virol. 78, 568–575 10.1128/JVI.78.2.568-575.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ingallinella P., Bianchi E., Ladwa N. A., Wang Y. J., Hrin R., Veneziano M., Bonelli F., Ketas T. J., Moore J. P., Miller M. D., and Pessi A. (2009) Addition of a cholesterol group to an HIV-1 peptide fusion inhibitor dramatically increases its antiviral potency. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 5801–5806 10.1073/pnas.0901007106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Augusto M. T., Hollmann A., Castanho M. A., Porotto M., Pessi A., and Santos N. C. (2014) Improvement of HIV fusion inhibitor C34 efficacy by membrane anchoring and enhanced exposure. J. Antimicrobial Chemother. 69, 1286–1297 10.1093/jac/dkt529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Chong H., Wu X., Su Y., and He Y. (2016) Development of potent and long-acting HIV-1 fusion inhibitors. AIDS 30, 1187–1196 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chong H., Xue J., Xiong S., Cong Z., Ding X., Zhu Y., Liu Z., Chen T., Feng Y., He L., Guo Y., Wei Q., Zhou Y., Qin C., and He Y. (2017) A lipopeptide HIV-1/2 fusion inhibitor with highly potent in vitro, ex vivo, and in vivo antiviral activity. J. Virol. 91, e00288–00217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ashkenazi A., Viard M., Unger L., Blumenthal R., and Shai Y. (2012) Sphingopeptides: dihydrosphingosine-based fusion inhibitors against wild-type and enfuvirtide-resistant HIV-1. FASEB J. 26, 4628–4636 10.1096/fj.12-215111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wexler-Cohen Y., and Shai Y. (2009) Membrane-anchored HIV-1 N-heptad repeat peptides are highly potent cell fusion inhibitors via an altered mode of action. PLoS Pathog. 5, e1000509 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ding X., Zhang X., Chong H., Zhu Y., Wei H., Wu X., He J., Wang X., and He Y. (2017) Enfuvirtide (T20)-based lipopeptide is a potent HIV-1 cell fusion inhibitor: implication for viral entry and inhibition. J. Virol. 91, e00831–00817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. deCamp A., Hraber P., Bailer R. T., Seaman M. S., Ochsenbauer C., Kappes J., Gottardo R., Edlefsen P., Self S., Tang H., Greene K., Gao H., Daniell X., Sarzotti-Kelsoe M., Gorny M. K., et al. (2014) Global panel of HIV-1 Env reference strains for standardized assessments of vaccine-elicited neutralizing antibodies. J. Virol. 88, 2489–2507 10.1128/JVI.02853-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Pan C., Cai L., Lu H., Qi Z., and Jiang S. (2009) Combinations of the first and next generations of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) fusion inhibitors exhibit a highly potent synergistic effect against enfuvirtide- sensitive and -resistant HIV type 1 strains. J. Virol. 83, 7862–7872 10.1128/JVI.00168-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Steffen I., and Pöhlmann S. (2010) Peptide-based inhibitors of the HIV envelope protein and other class I viral fusion proteins. Curr. Pharm. Des. 16, 1143–1158 10.2174/138161210790963751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Dwyer J. J., Wilson K. L., Davison D. K., Freel S. A., Seedorff J. E., Wring S. A., Tvermoes N. A., Matthews T. J., Greenberg M. L., and Delmedico M. K. (2007) Design of helical, oligomeric HIV-1 fusion inhibitor peptides with potent activity against enfuvirtide-resistant virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 12772–12777 10.1073/pnas.0701478104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. He Y., Xiao Y., Song H., Liang Q., Ju D., Chen X., Lu H., Jing W., Jiang S., and Zhang L. (2008) Design and evaluation of sifuvirtide, a novel HIV-1 fusion inhibitor. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 11126–11134 10.1074/jbc.M800200200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Otaka A., Nakamura M., Nameki D., Kodama E., Uchiyama S., Nakamura S., Nakano H., Tamamura H., Kobayashi Y., Matsuoka M., and Fujii N. (2002) Remodeling of gp41-C34 peptide leads to highly effective inhibitors of the fusion of HIV-1 with target cells. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 41, 2937–2940 10.1002/1521-3773(20020816)41:16%3C2937::AID-ANIE2937%3E3.0.CO%3B2-J [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. He Y., Cheng J., Lu H., Li J., Hu J., Qi Z., Liu Z., Jiang S., and Dai Q. (2008) Potent HIV fusion inhibitors against Enfuvirtide-resistant HIV-1 strains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 16332–16337 10.1073/pnas.0807335105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Chong H., Yao X., Qiu Z., Sun J., Zhang M., Waltersperger S., Wang M., Liu S. L., Cui S., and He Y. (2013) Short-peptide fusion inhibitors with high potency against wild-type and enfuvirtide-resistant HIV-1. FASEB J. 27, 1203–1213 10.1096/fj.12-222547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Chong H., Qiu Z., Su Y., Yang L., and He Y. (2015) Design of a highly potent HIV-1 fusion inhibitor targeting the gp41 pocket. AIDS 29, 13–21 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Chong H., Yao X., Zhang C., Cai L., Cui S., Wang Y., and He Y. (2012) Biophysical property and broad anti-HIV activity of albuvirtide, a 3-maleimimidopropionic acid-modified peptide fusion inhibitor. PLoS One 7, e32599 10.1371/journal.pone.0032599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ishikawa H., Meng F., Kondo N., Iwamoto A., and Matsuda Z. (2012) Generation of a dual-functional split-reporter protein for monitoring membrane fusion using self-associating split GFP. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 25, 813–820 10.1093/protein/gzs051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kondo N., Miyauchi K., Meng F., Iwamoto A., and Matsuda Z. (2010) Conformational changes of the HIV-1 envelope protein during membrane fusion are inhibited by the replacement of its membrane-spanning domain. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 14681–14688 10.1074/jbc.M109.067090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Chou T. C., and Talalay P. (1984) Quantitative analysis of dose-effect relationships: the combined effects of multiple drugs or enzyme inhibitors. Adv. Enzyme Regul. 22, 27–55 10.1016/0065-2571(84)90007-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Chou T. C. (2006) Theoretical basis, experimental design, and computerized simulation of synergism and antagonism in drug combination studies. Pharmacol. Rev. 58, 621–681 10.1124/pr.58.3.10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Otwinowski Z., and Minor W. (1997) Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 276, 307–326 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. McCoy A. J., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., Adams P. D., Winn M. D., Storoni L. C., and Read R. J. (2007) Phaser crystallographic software. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 40, 658–674 10.1107/S0021889807021206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Emsley P., and Cowtan K. (2004) Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2126–2132 10.1107/S0907444904019158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Adams P. D., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., Hung L. W., Ioerger T. R., McCoy A. J., Moriarty N. W., Read R. J., Sacchettini J. C., Sauter N. K., and Terwilliger T. C. (2002) PHENIX: building new software for automated crystallographic structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 58, 1948–1954 10.1107/S0907444902016657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Laskowski R. A., MacArthur M. W., Moss D. S., and Thornton J. M. (1993) PROCHECK: a program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 26, 283–291 10.1107/S0021889892009944 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.