Abstract

ATP-sensitive K+ (KATP) channels uniquely link cellular energy metabolism to membrane excitability and are expressed in diverse cell types that range from the endocrine pancreas to neurons and smooth, skeletal, and cardiac muscle. A decrease in the surface expression of KATP channels has been linked to various disorders, including dysregulated insulin secretion, abnormal blood pressure, and impaired resistance to cardiac injury. In contrast, up-regulation of KATP channel surface expression may be protective, for example, by mediating the beneficial effect of ischemic preconditioning. Molecular mechanisms that regulate KATP channel trafficking are poorly understood. Here, we used cellular assays with immunofluorescence, surface biotinylation, and patch clamping to demonstrate that Eps15 homology domain-containing protein 2 (EHD2) is a novel positive regulator of KATP channel trafficking to increase surface KATP channel density. EHD2 had no effect on cardiac Na+ channels (Nav1.5). The effect is specific to EHD2 as other members of the EHD family—EHD1, EHD3, and EHD4—had no effect on KATP channel surface expression. EHD2 did not directly affect KATP channel properties as unitary conductance and ATP sensitivity were unchanged. Instead, we observed that the mechanism by which EHD2 increases surface expression is by stabilizing KATP channel–containing caveolar structures, which results in a reduced rate of endocytosis. EHD2 also regulated KATP channel trafficking in isolated cardiomyocytes, which validated the physiologic relevance of these observations. Pathophysiologically, EHD2 may be cardioprotective as a dominant-negative EHD2 mutant sensitized cardiomyocytes to ischemic damage. Our findings highlight EHD2 as a potential pharmacologic target in the treatment of diseases with KATP channel trafficking defects.—Yang, H. Q., Jana, K., Rindler, M. J., Coetzee, W. A. The trafficking protein, EHD2, positively regulates cardiac sarcolemmal KATP channel surface expression: role in cardioprotection.

Keywords: caveolae, endocytosis, ischemic preconditioning, endocytic recycling

By coupling cellular intracellular energy metabolism to membrane excitability, ATP-sensitive K+ (KATP) channels regulate diverse physiologic processes, including glucose homeostasis, by actions on pancreatic β-cells and the hypothalamus, blood flow by affecting vascular smooth muscle and endothelial cells, neurotransmitter release from sympathetic and parasympathetic nerves and centrally in the brain, and action potential duration adaptation in the heart in response to elevated heart rates (1, 2). Sarcolemmal KATP channels also participate in the adaptation to stress and are involved in the protective mechanisms of ischemic preconditioning (2–4); however, certain pathophysiologic conditions lead to a decrease in the density of plasmalemmal/sarcolemmal KATP channels, including hyperinsulinemia and cardiac ischemia (1, 3). A decrease in surface expression can also result from trafficking defects that are caused by genetic variation associated with hypoglycemia, diabetes mellitus, atrial fibrillation, and dilated cardiomyopathy (1). In contrast, maintaining surface KATP channel density is linked to the cardioprotective effects of ischemic preconditioning (3). Therefore, strategies to rescue trafficking disorders and/or to increase KATP channel surface expression have a high therapeutic potential; however, the molecular mechanisms that are involved in KATP channel trafficking are poorly understood.

Our previously published proteomics experiments—designed to identify components of the KATP channel macromolecular complex—suggest that members of the Eps15 homology domain (EHD) protein family (EHD1–4) may fulfill this role (5, 6). EHD proteins are known trafficking proteins that induce and maintain membrane shape (bending, vesiculation, and tubulation). Each of the 4 EHD protein members participate in intracellular trafficking of protein cargo, but act at distinct trafficking steps. For example, EHD1, also named Rme1, regulates the exit of protein cargo from the endocytic recycling compartment (ERC) on its way to the surface membrane and may also participate in endocytosis (7). Its closest paralog, EHD3, regulates cargo that traffics from early endosomes to the ERC and to the Golgi apparatus (8, 9). EHD4 participates in the transport of cargo from the early endosome to the recycling endosome (10). EHD2 is interesting in that, as the most distant paralog of the EHDx family, it stabilizes the transferrin receptor by preventing endocytosis (11–13). EHD2 has also been described to regulate the exit of cargo from the ERC en route to the cell surface (10). Each of the 4 EHD proteins are expressed in the heart (14); however, to date, only EHD3 has been characterized and demonstrated to regulate the surface density of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger and the T-type Ca2+ channel (14, 15). Given that EHD proteins are components of the KATP channel macromolecular complex (5, 6), we examined the possibility that they regulate KATP channel trafficking and surface density. We focused on KATP channels that consist of Kir6.2/SUR2A subunits, as they are the molecular candidates for cardiac ventricular KATP channels (2). Our data demonstrate that, of the 4 family members, only EHD2 affects the cardiac KATP channel by increasing its surface density. The mechanism by which EHD2 increases surface expression is by stabilizing KATP channel–containing caveolar structures, which results in a reduced rate of endocytosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

cDNA constructs and mutagenesis

EHD1–4 cDNAs were obtained commercially (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Their coding regions were subcloned with PCR using primer pairs 1636–1639 (Supplemental Table 1) into the pcDNA3.2/V5/GW/D-TOPO vector. Mutations of the conserved glycine residue to an alanine in the catalytic ATP binding site were made by means of site-directed mutagenesis (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and primer pairs 1640–1643 (Supplemental Table 1). All constructs were verified by sequencing (Macrogen, New York, NY, USA). We also generated a new Avi-Kir6.2 cDNA in which the extracellular hemagglutinin (HA) epitope of Kir6.2-HA11+ (kindly supplied by Dr. Lily Jan, University of California, San Francisco, CA, USA) (16, 17) was replaced by a 15 aa Avi tag to which a single biotin can be enzymatically bound with biotin ligase. A derivative—Avi-Kir6.2-PAmCherry—was generated by fusing photoactivatable mCherry to its C terminus. We also used the Kir6.2-myc construct, in which 6 myc epitopes were introduced at the Kir6.2 C terminus. GFP-EEA1 (42307) for sorting endosome, EGFP-Rab7a (28047) for late endosome, Lamp1-mGFP (34831) for lysosome, mWasabi-Golgi7 (56504) for Golgi, GFP-Rab11 (12674) for ERC, and GFP-Rab11–S25N (12678) were all obtained from Addgene (Cambridge, United Kingdom).

Electrophysiology

Standard patch clamping was performed by using an Axopatch-200B amplifier and data were recorded with a Digidata 1550A and Clampex 10 software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). For inside-out KATP current recordings, pipette resistance was 3∼4 MΩ when filled with pipette solution that consisted of (in millimolar) 110 potassium gluconate, 30 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, and pH 7.4. Bath solution consisted of (in millimolar) 110 potassium gluconate, 30 KCl, 1 EGTA, 1 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, and pH 7.2. After patch excision, pipette potential was held at +80 mV and current was digitized at 5 kHz. Currents were recorded immediately after patch excision and recordings with any sign of rundown were discarded. The cytosolic ATP concentration was changed by a rapid solution changer (RSC200; Bio-logic SAS, Seyssinet-Pariset, France). For whole-cell Na+ current recordings, a standard Tyrode solution was used. Pipette resistance was ∼2.0 MΩ with a pipette solution that consisted of (in millimolar) 50 CsCl, 60 CsF, 10 NaCl, 20 EGTA, 10 HEPES, and pH 7.2. After whole-cell capacitance and series resistance compensation (80%), depolarizing voltage steps (from −100 to +100 mV in 10-mV increments) were applied with a holding potential of −100 mV.

Biotinylation assay

HEK293 cells that expressed Avi-tagged Kir6.2 were incubated with 0.33 mM biotin for 1 h at 4°C. After washing with PBS, cells were homogenized in RIPA buffer. Equal amounts of biotinylated proteins were incubated with neutravidin agarose beads (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 4°C overnight. Supernatants were discarded and biotinylated proteins were eluted by a mixture of loading buffer and 200 mM DTT. For internalization assays, cells were incubated at 37°C for 1–15 min after biotinylation and additionally incubated at 4°C with streptavidin to block surface biotin. Western blots were quantified by using ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Immunofluorescence microscopy

We used COS7 cells that were transfected with C-terminal myc-tagged Kir6.2 and SUR2A (Lipofectamine 2000) or isolated mouse or rat cardiomyocytes on glass coverslips. Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 15 min, and blocked with 5% goat or donkey serum in PBS for 30 min at room temperature. Primary Abs—anti-myc, anti-Kir6.2, anti-EHD2, or anti-caveolin3—that were buffered in blocking solution were applied for 1 h. After washing with PBS, secondary Abs in blocking solution were applied for 45 min. After washing and mounting, images were obtained by using a Zeiss 700 confocal microscope (Zeiss, Jena, Germany). Colocalization of KATP channels and intracellular compartments was quantified by Mander’s coefficients using ImageJ.

Ab uptake assay

Cos7 cells that expressed extracellular HA-tagged KATP channels were first blocked with 5% goat serum and incubated with mouse anti-HA Abs at room temperature. HA labeling of the channel was specific, as HA staining colocalized with staining that was performed with anti-Kir6.2 Abs (data not shown). After washing with ice-cold PBS to remove unbound Abs, cells were incubated at 37°C to induce channel internalization, then immediately fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. Cells were incubated with Cy3-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary Abs to label surface KATP channels and, after permeabilization, were incubated with Dylight488 secondary Abs to label internalized KATP channels. After washing, coverslips were mounted on slides and imaged by confocal microscopy.

Subcellular fractionation of caveolin-enriched membranes

Cardiomyocytes were washed twice with ice-cold PBS and incubated in 0.5 M sodium carbonate (pH 11) for 30 min on ice. Additional homogenization was performed with a loose-fitting Dounce homogenizer for ∼10 strokes. Lysate was sonicated for 10 s at maximal energy. A discontinuous OptiPrep gradient was prepared with a 60% OptiPrep solution (D1556; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) that was diluted to 20, 25, and 30% with 0.25 M sodium carbonate solution. The homogenate was adjusted to 35% OptiPrep (1 ml) and placed at the bottom of an ultracentrifuge tube, overlaid with 30% (1 ml), 25% (1 ml), 20% (1 ml), and 0% (0.5 ml). Tubes were centrifuged at 39,000 rpm for 18 h in a TH660 rotor (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Nine fractions (0.5 ml each) were collected from top to bottom for Western blot analysis.

Vesicle tracking assay

The extracellular surface of live HEK293 cells that expressed extracellular HA-tagged Kir6.2 (with SUR2A) was blocked with 5% goat serum before cells were incubated with mouse anti-HA Abs at 37°C for 30 min. After washing with normal medium to remove unbound Abs, cells were incubated at room temperature with Cy3-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary Abs to label surface KATP channels. Immediately after washing with normal medium, a series of images were obtained by confocal microscopy, focusing on the bottom of cells. The image series was analyzed by TrackMate (ImageJ) to calculate the velocity of vesicle movement.

Isolation and infection of mouse or rat ventricular myocytes

Mouse or rat ventricular cardiomyocytes were enzymatically isolated as previously described (5). Cells were plated on laminin-coated coverslips and cultured in Eagle’s Minimum Essential Medium. Adenoviruses that carry PAmCherry-labeled wild-type or dominant-negative EHD2 (Vector Biolabs, Malvern, PA, USA) were added at a multiplicity of infection of 1000 for a 12-h incubation. An mCherry-expressing adenovirus was used as control. Cultured cardiomyocytes were used for experiments at 48 h postinfection.

Cellular ischemia model

We used a cellular ischemia model (18) in which cultured rat cardiomyocytes were pelleted—centrifugation at 1500 rpm for 30 s at room temperature—and overlaid with mineral oil (200 µl) to prevent gas exchange. In a group of cells, pharmacologic preconditioning was achieved by pretreatment with phenylephrine (5 μM) incubation for 10 min followed by Tyrode solution for 5 min. After a 15-min ischemic period (at 35°C), 2-µl cell aliquots were sampled through the oil, resuspended in hypotonic Tyrode solution that contained 0.002% Trypan blue, and visualized microscopically to count the number of viable cells.

Abs and reagents used

Primary Abs used were as follows: goat anti-EHD2 (SAB2500345; 1:50; Sigma-Aldrich), goat anti-EHD2 (ab23935; 1:50; Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom), mouse anti-caveolin3 (610421; BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA; 1:200 for immunocytochemistry and 1:20,000 for Western blot), chicken anti-Kir6.2 (C62; 1:50), goat anti-Kir6.2 (N18; 1:200; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA), goat anti-SUR2A (M19; 1:1000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), mouse anti-GADPH (GAPDH; 1:10,000; EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA), mouse anti–c-Myc (M4439; 1:800; Sigma-Aldrich), and mouse anti-HA (MMS-101P; 1:800; Covance, Princeton, NJ, USA). Secondary Abs used were donkey anti–mouse horseradish peroxidase (sc-2096; 1:50,000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), donkey anti–goat horseradish peroxidase (sc-2056; 1:5000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), donkey anti–goat Cy3 (705-165-147; 1:200; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA, USA), donkey anti–chicken Alexa Fluor488 (703-545-155; 1:200; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories), goat anti–mouse Cy3 (115-165-146; 1:400; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories), and goat anti–mouse Dylight488 (115-485-205; 1:400; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories). Dynasore and methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MβCD) were from Sigma-Aldrich and pitstop 2 was obtained from Abcam.

Statistics

When comparing 2 groups, we used the Student’s t test. A 1- or 2-way ANOVA was used for the comparison of multiple groups, followed by ad hoc pairwise comparison using Tukey’s t test, or Dunnett’s t test for comparisons with a single control. Values of P < 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

EHD2 positively regulates KATP channel current density

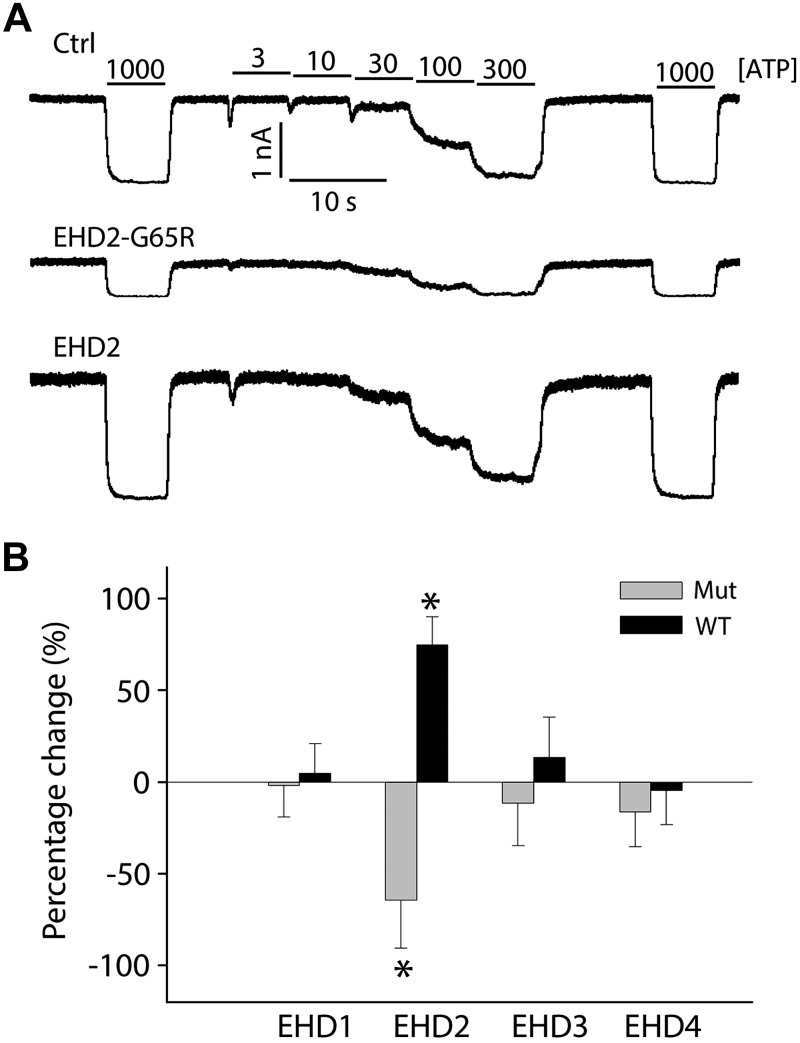

Our proteomics data have identified EHD trafficking proteins in KATP channel immunoprecipitates. To examine whether they regulate KATP channel trafficking and result in changes in surface density, we individually coexpressed EHD proteins—EHD1, EHD2, EHD3 or EHD4—with KATP channel subunits (Kir6.2/SUR2A) in HEK293 cells. We assessed KATP channel current density with inside-out membrane patches by recording the mean patch current in ATP-free solutions. KATP channel mean patch current was significantly increased in cells that expressed EHD2, whereas EHD1, EHD3, or EHD4 had no effect on KATP channel current amplitude (Fig. 1). We also investigated dominant-negative EHDx subunits in which a conserved glycine in the ATP-binding region within the N-terminal P-loop was mutated to an arginine residue to disrupt nucleotide binding (8, 12). Consistent with a selective role for EHD2 in the regulation of KATP channel surface density, expression of the EHD2-G65R mutant led to a marked reduction of KATP channel mean patch current (Fig. 1A, B), whereas EHD1-G65R, EHD3-G65R, and EHD4-G68R did not produce this response.

Figure 1.

Of EHDx family members, only EHD2 regulates KATP current density. A) Representative inside-out current recordings obtained from HEK293 cells that stably expressed Kir6.2/SUR2A in control, EHD2-G65R, and wild-type (WT) EHD2 groups. ATP concentrations were switched as indicated. B) Summary data of mean patch currents for all WT (black) and dominant-negative (mut; gray) EHDs, shown as percentage changes relative to control group (n > 8 patches in each group). *P < 0.05 vs. the control group.

EHD2 does not affect Na+ current density

We investigated whether the effects of EHD2 are indiscriminate by examining its impact on Nav1.5, a subunit of the cardiac Na+ current. When coexpressed with Nav1.5 in HEK293 cells, neither wild-type EHD2, nor EHD2-G65R had any effect on whole-cell Nav1.5 current density or on the inactivation time course (Supplemental Fig. 1). Thus, not all ion channels are similarly affected by EHD2.

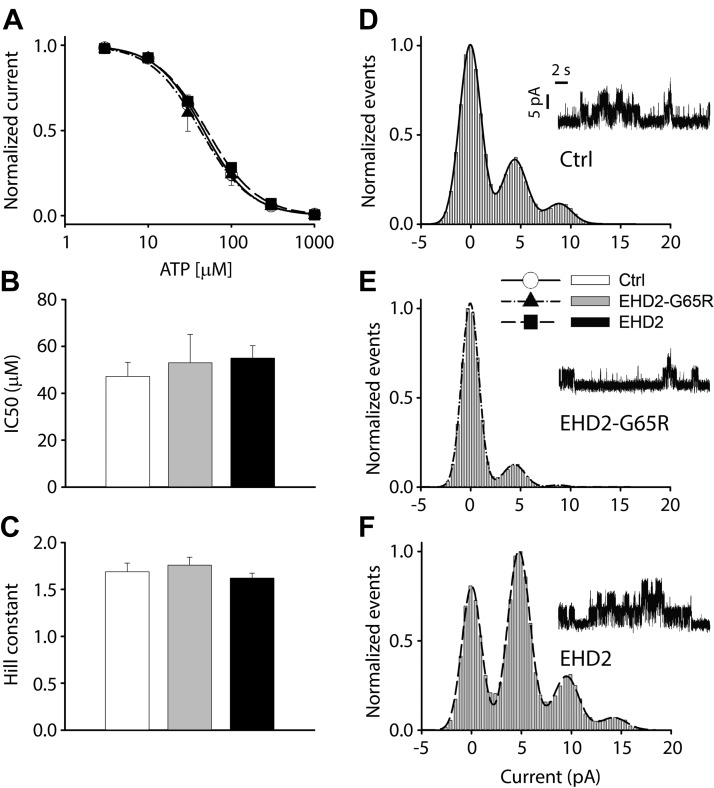

EHD2 does not affect the intrinsic properties of the KATP channel

We next determined whether EHD2 has a direct effect on the KATP channel. We measured the ATP sensitivity of the channel by varying the ATP levels at the cytosolic face of excised membrane patches (Fig. 2A). Mean patch current was plotted as a function of the ATP concentration and data were fitted to a curve of a modified Hill equation (Fig. 2A). IC50 value under control conditions was 50 ± 5.8 μM, with a Hill coefficient of 1.7 ± 0.10 (n = 11; Fig. 2B, C). Neither EHD2 (n = 19), nor EHD2-G65R (n = 7) affected the IC50 value (55 ± 5 and 53 ± 12 μM, respectively) or the Hill coefficient (1.6 ± 0.06 and 1.8 ± 0.09, respectively). These experiments also allowed us to measure the amplitudes of sporadic KATP channel events that occur in the presence of 1 mM ATP using all-point histograms and curve fitting to gaussian distributions (Fig. 2D–F). The unitary KATP channel current was 4.4 ± 0.04 pA for control (n = 6) and was unaffected by coexpression with EHD2 or EHD2-G65R (4.6 ± 0.08 pA; n = 3; and 4.4 ± 0.08 pA; n = 5, respectively).

Figure 2.

EHD2 does not directly affect KATP channel properties. A) Fractional currents—normalized by the mean patch current in the absence of ATP—was plotted as a function of ATP concentration. B, C) These data were fitted to a curve of a modified Hill equation to obtain IC50 values and Hill constants for each trace. Aggregate data are depicted as bar graphs (means ± sem) for the control group (white, n = 11), EHD2-G65R (gray, n = 7), and wild-type EHD2 (black, n = 19). D–F) Representative recordings of residual single KATP channel openings in the presence of 1 mM ATP. All-points histograms were constructed from these events and fitted to a curve fitting of a gaussian distribution to determine the unitary current amplitude (n > 3 patches in each group).

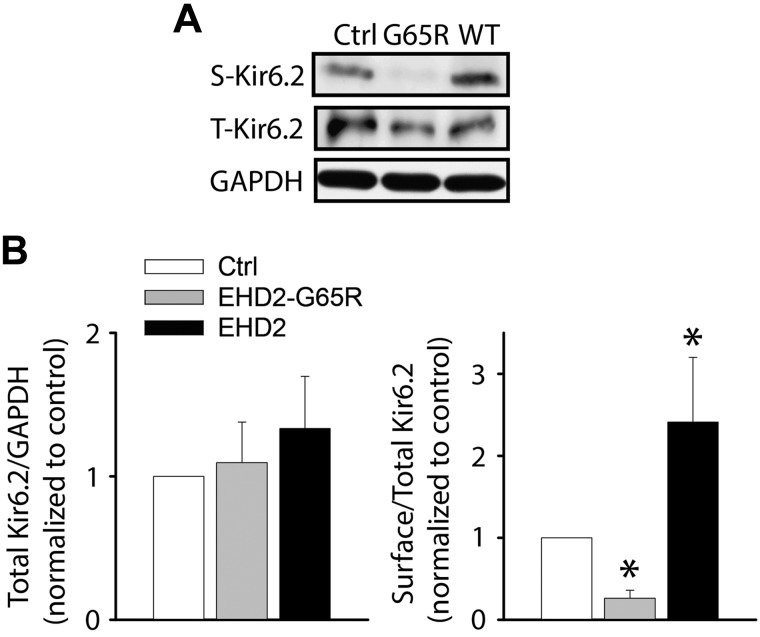

EHD2 up-regulates KATP channel surface density

Electrophysiologic data are consistent with the concept that EHD2 enhances KATP channel surface expression—we tested this possibility biochemically. To this end, we engineered an Avi tag in the extracellular loop of Kir6.2 (Avi-Kir6.2) that allows for specific BirA-mediated biotinylation of surface KATP channels. This tag had no effect on KATP channel properties or subcellular distribution (data not shown). Avi-Kir6.2/SUR2A channels were expressed in HEK293 cells and surface biotinylated after 48 h. Biotinylated proteins were purified with streptavidin agarose beads and subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with anti-Kir6.2 Abs. We first verified the validity of the assay. Little surface expression was observed in cells that were transfected only with Avi-Kir6.2, whereas coexpression with SUR2A significantly increased surface expression (Supplemental Fig. 2). This observation is consistent with the fact that coexpression of Kir6.2 and SURx is needed to facilitate surface expression (16). We next assessed the effects of EHD2. We found that coexpression of Avi-Kir6.2/SUR2A with wild-type EHD2 significantly increased surface expression, whereas EHD2-G65R decreased surface expression (Fig. 3). Similar data were obtained with Kir6.2/SUR1 combinations (Supplemental Fig. 2). These data corroborate the electrophysiologic data and demonstrate that EHD2 positively regulates KATP channel surface density.

Figure 3.

EHD2 increases KATP channel surface expression. A) HEK293 cells were transfected with Avi-Kir6.2/SUR2A (extracellular Avi tag) and the surface channel was biotinylated. Biotinylated proteins were enriched with neutravidin beads and subjected with immunoblotting with anti-Kir6.2 Abs. Shown are representative blots of total (T) and biotinylated surface (S) Avi-Kir6.2 expression. B) Ratios of total Kir6.2 to GAPDH and biotinylated to total Avi-Kir6.2 are shown for control (white), EHD2-G65R (gray), and wild-type EHD2 (black; n = 3 blots/group). *P < 0.05 vs. control.

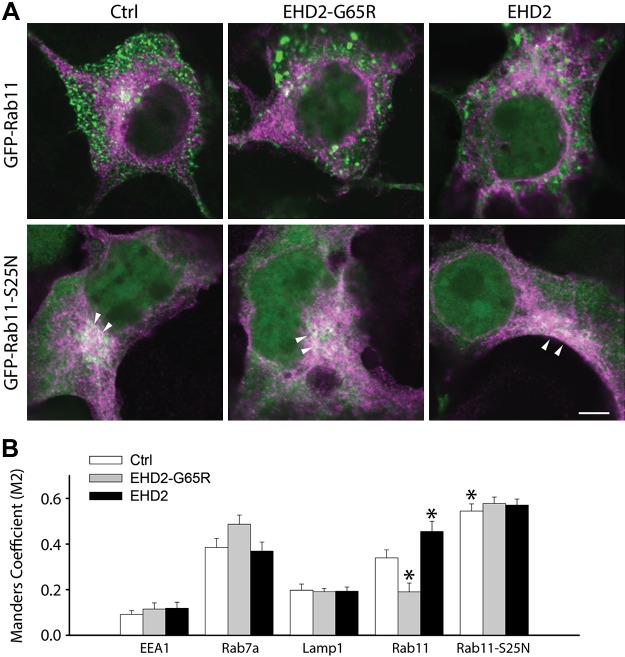

Effects of EHD2 on the subcellular localization of KATP channel subunits

Mechanisms of trafficking proteins can be studied by examining the subcellular localization of trafficked cargo. A previous report has suggested that EHD2 may participate in the exit of cargo from the ERC en route to the cell surface (10). We performed immunofluorescence microscopy experiments to test this possibility. For these experiments, we used a Kir6.2 subunit with 6 C-terminal myc epitopes to facilitate specific intracellular detection. COS7 cells were cotransfected with Kir6.2-myc/SUR2A and the cDNAs of markers of specific subcellular trafficking organelles, including GFP-EEA1 (early endosomes or sorting endosomes), EGFP-Rab7a (late endosomes), GFP-Rab11 (ERC), and LAMP1-GFP (lysosomes). As previously reported (17), we observed KATP channels (myc staining) in Rab7a+ late endosomes and in LAMP1+ lysosomes (Fig. 4). A novel finding is the presence—at steady state—of KATP channel subunits in the Rab11+ ERC, which suggests that endocytosed KATP channels traffic via the ERC. In support, the GFP-Rab11-S25N dominant interfering Rab11 mutant, known to prevent exit of cargo from the ERC (19), accumulates KATP channels in the ERC (Fig. 4). In general, EHD2 or EHD2-G65R has little effect on the subcellular distribution of KATP channels, with the exception that, similar to GFP-Rab11-S25N, EHD2 caused accumulation in the ERC. The presence of Kir6.2-myc in the ERC was also reduced by EHD2-G65R (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

KATP channels cycle through the ERC and accumulate in the ERC in the presence of EHD2. A) Representative images of COS7 cells that were transfected with myc-tagged Kir6.2 (magenta) and GFP-tagged wild-type and dominant-negative Rab11-S25N (green). Note the intense labeling of Kir6.2 in a perinuclear region, especially in the Rab11-S25N–expressing cells (arrows). B) Manders M2 coefficient of colocalization was calculated as an index of the presence of Kir6.2-myc in various subcellular compartments. Scale bar, 5 μm. *P < 0.05 vs. control or Rab11 groups.

KATP channel endocytosis is minimized in the presence of EHD2

As EHD2 has previously been assigned a role in the endocytosis of the transferrin receptor (11), we investigated whether EHD2 influences KATP channel endocytosis. Surface proteins of live HEK293 cells—transfected with Avi-Kir6.2/SUR2A—were biotinylated at room temperature, which diminished the rate of endocytic recycling. Temperature was then restored to 37°C to allow endocytosis to resume. Extracellular biotin was quenched at various time points to ensure that the only biotin molecules that were available for chemical reactions were those that had been internalized. Cells were lysed and biotinylated proteins were enriched with neutravidin agarose beads, followed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with anti-Kir6.2 Abs. As expected, the amount of internalized Avi-Kir6.2 protein gradually increased over a 15-min rewarming period as endocytosis proceeded (Fig. 5A). The rate of KATP channel endocytosis was greatly inhibited by EHD2 and accelerated by EHD2-G65R (Fig. 5B).

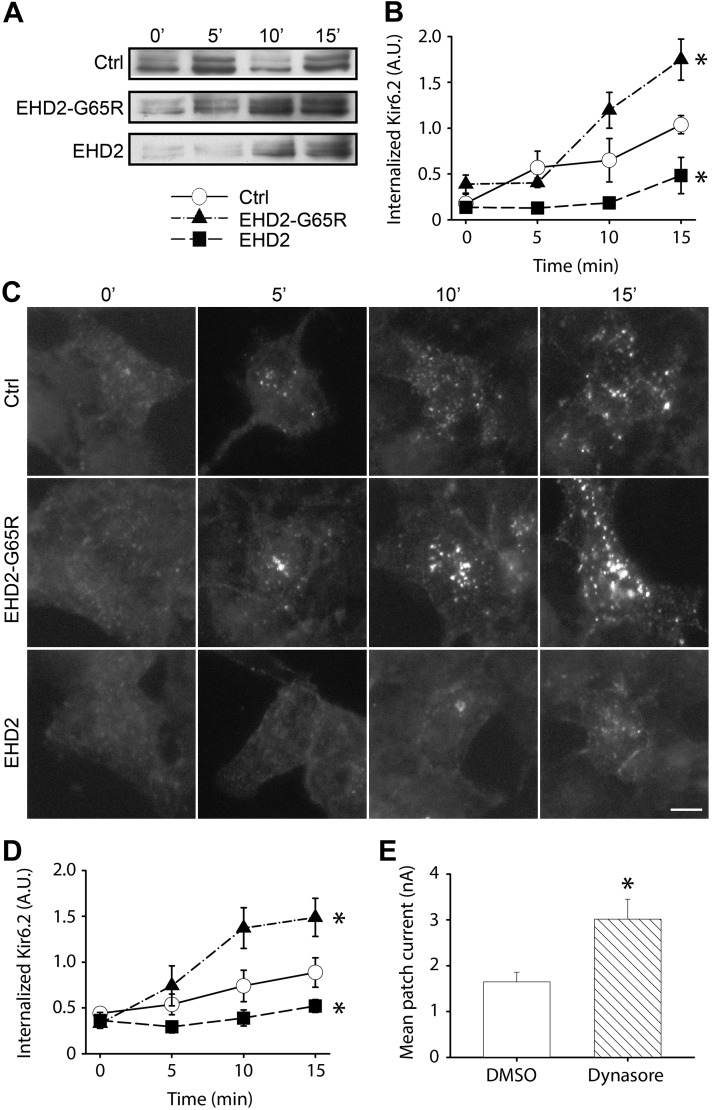

Figure 5.

KATP channel endocytosis is minimized in the presence of EHD2. A) Live HEK293 cells—transfected with Avi-Kir6.2/SUR2A—were surface biotinylated and the rate of biotinylated Avi-Kir6.2 was observed over time by immunoblot analysis—with anti-Kir6.2 Abs—of internalized biotinylated Avi-Kir6.2. B) Band intensities were quantified and plotted in the right panel (n = 3/group). C) Ab (anti-HA) uptake experiments with HEK293 cells that were transfected with Kir6.2-HA (extracellular tag) and SUR2A. Endocytosed Kir6.2-HA in vesicles was labeled and visualized with DyLight488-conjugated secondary Ab. D) Quantification of the endocytosed Kir6.2 in control (open circle), EHD2-G65R (closed triangle), and wild-type EHD2 (closed square) groups. E) Mean patch current was recorded in excised patches from HEK293 cells that were transfected with Kir6.2/SUR2A. Cells were pretreated with a dynamin inhibitor, Dynasore (80 µM for 2 h), or with DMSO as control. Scale bar, 10 μm. *P < 0.05 vs. control groups.

We independently confirmed biotinylation data with an Ab uptake assay using a Kir6.2 subunit with an extracellular HA tag (16). Surface Kir6.2 in live HEK293 cells—transfected with Kir6.2-HA/SUR2A—was labeled with an anti-HA Ab. Cells were incubated at 37°C to allow endocytosis of Ab-labeled Kir6.2. Cells were fixed and the remaining surface HA Abs were blocked by using Cy3-conjugated secondary Abs. After permeabilization, endocytosed HA Abs were detected with Dylight488-conjugated secondary Abs (Fig. 5C). As previously reported (17), Kir6.2 accumulated in intracellular vesicles as endocytosis proceeded. Consistent with the negative regulation of EHD2 on KATP channel endocytosis, the rate of vesicle formation was attenuated by EHD2 and strongly increased by EHD2-G65R (Fig. 5C, D). To confirm that endocytosis was sufficient to regulate KATP channel surface density, we used Dynasore to inhibit dynamin-dependent endocytosis. Treatment of Kir6.2/SUR2A-transfected HEK293 cells with 80 μM Dynasore for 2 h increased KATP channel mean patch current (Fig. 5E); thus, it is feasible for EHD2 to increase KATP channel surface density by inhibiting endocytosis of the channel.

EHD2 stabilizes KATP channels in caveolae

The rate of endocytosis can be diminished by direct effect on the endocytic machinery, or indirectly by stabilizing membrane cargo at the membrane. KATP channels have previously been reported to localize to caveolae (20). Indeed, we observed a reasonable degree of colocalization of Kir6.2 and caveolin3 in isolated cardiomyocytes, which was most notable at the periphery of the myocyte (Fig. 6A). EHD2 has previously been reported to stabilize caveolar structures in Hela cells (21–23). Therefore, we investigated whether EHD2 influences caveolae in heart cells. By using a detergent-free OptiPrep density gradient extraction procedure with homogenates from isolated cardiomyocytes, we found enrichment of Kir6.2 in caveolar fractions—identified by the presence of caveolin3 (Fig. 6B, Ctrl). Disruption of caveolae by cholesterol depletion with MβCD shifted both caveolin3 and Kir6.2 to higher density fractions. Similarly, after adenoviral delivery of Ad-EHD2-G65R to cardiomyocytes for 48 h, both caveolin3 and Kir6.2 shifted to higher density fractions (Fig. 6B). This result demonstrated a key role for EHD2 to stabilize caveolae in heart cells and to maintain KATP channels in these sarcolemmal microdomains.

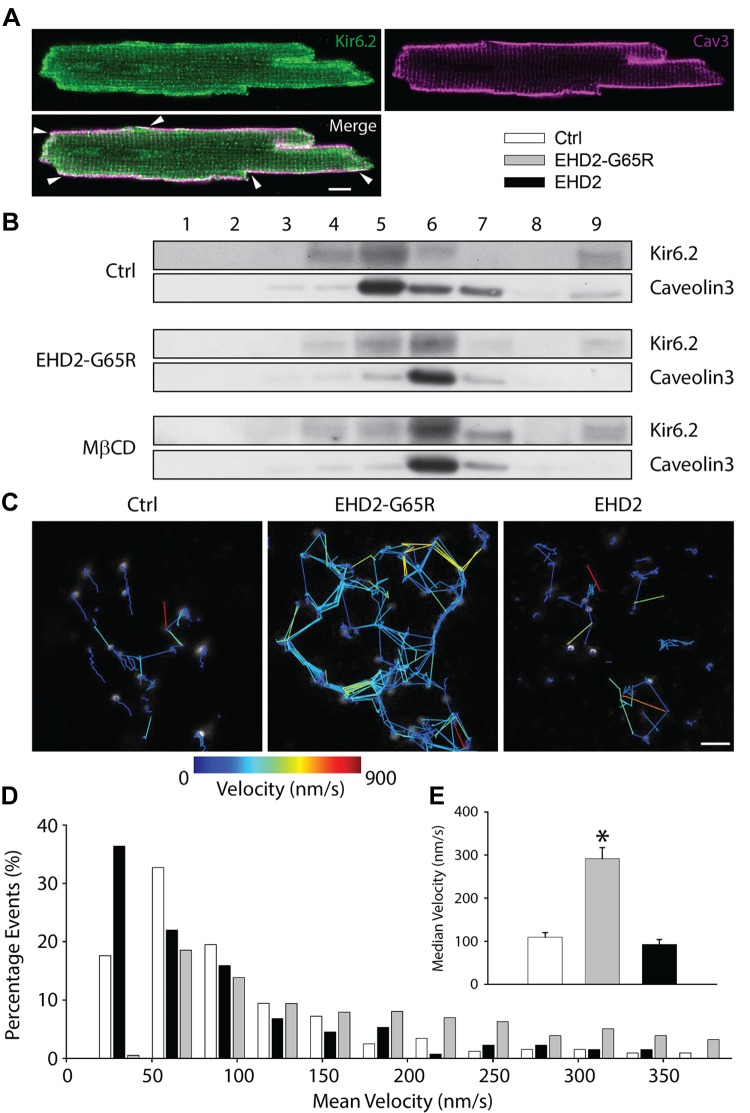

Figure 6.

EHD2 stabilizes KATP channels in caveolae. A) Representative images obtained with Abs against Kir6.2 (green) and caveolin3 (magenta) showing colocalization on the cell periphery (arrowheads). Scale bar, 10 μm. B) Fractions after OptiPrep gradient ultracentrifugation collected from top to bottom were analyzed with Abs against Kir6.2 and caveolin3 in control, EHD2-G65R, and myocytes that were pretreated with 10 mM MβCD for 1 h. C–E) Representative images showing the tracking routes of surface KATP channel vesicles (C), histogram distribution of vesicle mean velocity (D), and average median velocities in control, EHD2-G65R, and wild-type EHD2 groups (E; n > 132 vesicles in each group). *P < 0.05 vs. control group.

We directly investigated whether surface channels are stabilized by EHD2 by tracking KATP channel motility with live cell imaging. We expressed a Kir6.2 subunit with an extracellular HA tag and used anti-HA Abs to label surface channels, which appeared as membrane-associated vesicles (Fig. 6C). We dynamically tracked these vesicles and calculated their average velocities. In the presence of EHD2-G65R, Kir6.2-containing vesicles were significantly more mobile (Fig. 6D). On average, median velocity with EHD2-G65R was 291 ± 26 vs. 109 ± 11 nm/s in the control group (Fig. 6E). These data are consistent with previous reports that caveolin-labeled vesicles become more dynamic when EHD2 function is disrupted by a dominant-negative variant (22).

Clathrin-mediated endocytosis is enhanced when caveolae are destabilized

Thus far, our data demonstrate that EHD2 stabilizes KATP channel–containing caveolae, which is associated with increased KATP channel surface density. Disrupting EHD2 function disrupts caveolae, displaces KATP channels from these structures, and increases surface mobility of KATP channels. To provide insight into the mechanism by which EHD2-G65R decreases KATP channel surface density, we investigated whether intracellular uptake is involved. We used pitstop2, an inhibitor of clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Similar to Dynasore (Fig. 5), pitstop2 increased KATP channel current density in the absence of EHD2-G65R (Fig. 7), whereas EHD2-G65R caused a decrease in KATP channel current density and an increase in KATP channel uptake as assessed with an Ab uptake assay (Fig. 7); however, in the presence of pitstop2, EHD2-G65R neither reduced KATP channel current density, nor did it stimulate KATP channel uptake (Fig. 7). This result demonstrated that EHD2-G65R dislodges KATP channels from caveolae, which causes enhanced surface mobility of KATP channels, thereby predisposing the channels to endocytosis via clathrin-mediated endocytosis.

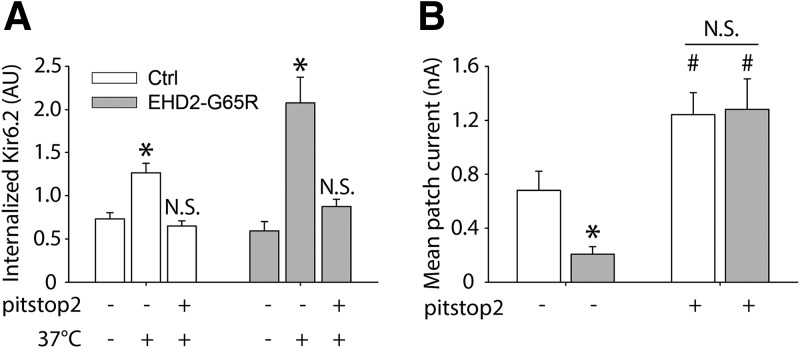

Figure 7.

Effect of dominant-negative EHD2 on KATP surface expression is dependent on clathrin-medicated endocytosis. A) HEK293 cells were transfected with Kir6.2-HA (extracellular tag) and SUR2A, and surface channels were labeled with anti-HA Abs at room temperature. Ab uptake was stimulated by warming cells to 37°C (as in Fig. 5C). Shown are groups of cells that were cotransfected with EHD2-G65R (shaded bars) or with empty vector as a control (ctrl; open bars). Experiments were performed in the presence of pitstop2 (preincubation with 30 µM for 2 h) or with solvent (DMSO) alone as control. *P < 0.05 vs. no treatment groups (n > 7 cells in each group). B) HEK-293 cells transfected with Kir6.2/SUR2A, co-transfected with EHD2-G65R or empty vector, were pretreated with pitstop 2 (30 µM for 2 h) before being patch clamped. Mean patch current was measured in inside-out patches immediately after patch excision and in the absence of ATP. *P < 0.05 vs. control group; #P < 0.05 vs. no pitstop 2 groups (n > 11 patches in each group).

EHD2 participates in the cardioprotective role of sarcolemmal KATP channels

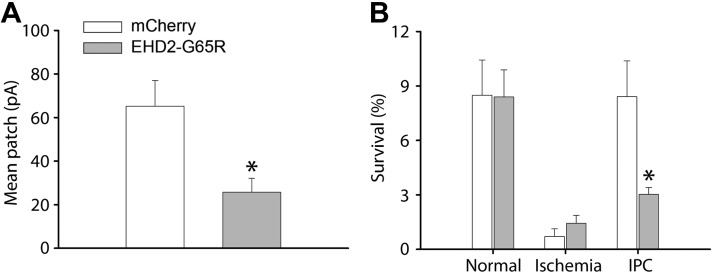

We have previously demonstrated that up-regulated KATP channel density is involved in the mediation of the protective effect of ischemic preconditioning (3). As EHD2 regulates KATP channel surface density, we investigated whether it has a role in ischemic preconditioning. Indeed, EHD2 is positioned to be able to regulate native KATP channels as it partially colocalizes with Kir6.2 at the periphery of isolated cardiomyocytes (Fig. 8A). We then studied the functional role of EHD2 by adenoviral delivery of wild-type EHD2, the dominant-negative EHD2-G65R, or mCherry as a control. KATP channel mean patch current was significantly reduced by EHD2-G65R (Fig. 8B) without changing intrinsic KATP channel properties (unitary conductance and ATP sensitivity; Fig. 8C, D). We used a cellular model of ischemia and pharmacologic preconditioning (18) to investigate the possibility that the overexpression of EHD2-G65R may limit the protective effects of preconditioning. Isolated cardiomyocytes were virally infected for 48 h by Ad-mCherry—as a control—or Ad-EHD2-G65R. Ischemia was mimicked by pelleting cardiomyocytes, followed by incubation with a mineral oil overlay to prevent gas exchange. Preconditioning was mimicked by preincubating cells with phenylephrine, which is known to pharmacologically precondition hearts (24). As expected in the control group, cellular ischemia caused significant loss of cardiomyocyte viability (assessed by Trypan blue staining), whereas phenylephrine preincubation protected against ischemia-induced cell death. A similar degree of cell death was observed in the Ad-EHD2-G65R group, but the protective effect of pharmacologic preconditioning was lost (Fig. 9B). Thus, EHD2-G65R leads to both a decrease of native KATP channel current density and a loss of the cardioprotective effect of preconditioning.

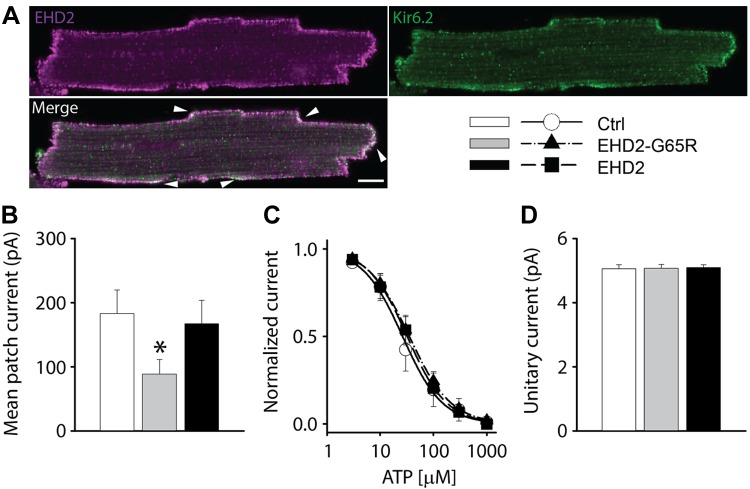

Figure 8.

EHD2 positively regulates the density of native KATP channels in ventricular cardiomyocytes. A) Representative images obtained with antibodies against Kir6.2 (green) and EHD2 (magenta) showing co-localization on cell periphery (arrowheads). Scale bar, 10 μm. B–D) KATP channel mean patch currents (B), fractional currents (normalized by the mean patch current in the absence of ATP) plotted as a function of ATP concentration (C), and unitary currents (D) in cardiomyocytes infected with mCherry (ctrl, white, open circle), EHD2-G65R (gray, closed triangle) or wild type EHD2 adenoviruses (black, closed square). *P < 0.05 vs. control group.

Figure 9.

EHD2-G65R abolished the cardioprotective effect of ischemic preconditioning. A) KATP channel mean patch currents in Ad-EHD2-G65R and Ad-mCherry groups (n = 4 patches in each group). B) Comparation of survival rates on rat cardiomyocytes infected with Ad-EHD2-G65R or Ad-mCherry in conditions without ischemia, with ischemia, and phenylephrine preconditioning before ischemia (n = 3 rats/group). *P < 0.05 vs. mCherry group.

DISCUSSION

A novel finding of this study is that EHD2 up-regulates the surface expression of KATP channels. A subpopulation of KATP channels are localized within caveolar microdomains, and EHD2 appears to stabilize these structures, thereby reducing channel mobility and availability for endocytosis and recycling. This phenomenon is physiologic as a dominant-negative form of EHD2 reduces native KATP channel density and limits the protective effect of cardiac preconditioning.

KATP channels traffic via the ERC

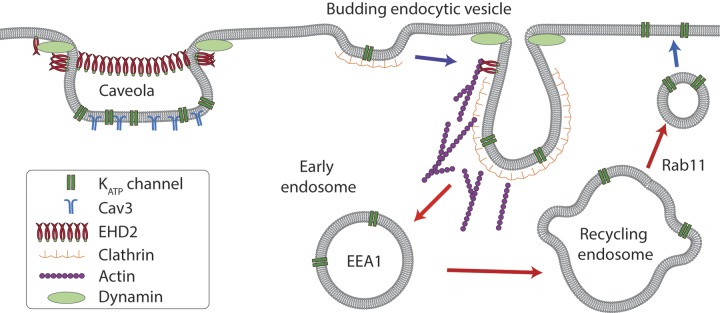

Endocytic recycling represents a potentially powerful mechanism by which to regulate surface density and the availability of ion channels. Cells internalize the equivalent of their entire surface area up to 5 times per hour and most endocytosed proteins are recycled back to the membrane (25). Not only is endocytic recycling a rapid process, but the rates of endocytosis and exocytosis are tightly controlled by specialized trafficking proteins and signaling pathways (25). Little is known about the processes that control the subcellular trafficking of KATP channels, and the relevant literature has recently been reviewed (2). In brief, cellular studies have demonstrated that KATP channels can be endocytosed (26–28) and are subsequently recycled to the membrane (29). Membrane proteins take specific routes through ERCs, with the exact path decided by a multitude of trafficking proteins; this route has not been fully characterized for KATP channels. KATP channels are endocytosed by a dynamin-dependent mechanism as their uptake can be inhibited by dominant-negative dynamin constructs or peptides or by the dynamin inhibitor, Dynasore (26–28, 30). Most studies support a dynamin/clathrin-mediated uptake process, as KATP channel endocytosis is inhibited by cytosolic K+ depletion, by exposure of cells to hypertonic medium, and by a dominant-negative form of the μ2 subunit of the adaptor protein 2 adaptor complex; internalized channels also colocalize with clathrin (27). Indeed, we observed that an inhibitor of clathrin-mediated endocytosis—pitstop2—inhibits KATP channel endocytosis and increases KATP channel surface expression. After endocytosis, KATP channels traffic through early endosomes, as evidenced by their partial colocalization with EEA1 [Fig. 5; discussed previously (31)]. From the early endosomes, internalized KATP channels traffic to late endosomes and lysosomes (17, 26), as demonstrated by their colocalization with Rab7a and LAMP1 (Fig. 5). The recycling route to the surface membrane has not been described. We found that KATP channels traffic via the ERC. Not only do KATP channels colocalize with the ERC marker, Rab11, but the dominant-negative Rab11-S25N accumulates KATP channels in these structures and decreases surface expression. Thus, KATP channel recycling resembles that of the transferrin receptor (19). These findings provide a better understanding of the endocytic trafficking mechanisms of KATP channels (Fig. 10) and identify steps that may be targeted to regulate surface density of the channel.

Figure 10.

Proposed mechanism by which EHD2 affects KATP channel subcellular trafficking. KATP channels are internalized via dynamin and clathrin-mediated endocytosis uptake mechanism. Our data demonstrate that KATP channels recycle through the ERC (or recycling endosome) en route to the surface membrane. Dominant-negative constructs of Rab11 and EHD2 have opposite effects on KATP channel distribution and surface density, which demonstrates that EHD2 acts upstream of this step. Although it is possible that EHD2 may influence endocytosis by promoting actin nucleation, the expected result—enhanced endocytosis by EHD2—is not supported by our data. Instead, we found that EHD2 stabilizes KATP channel–containing caveolae, thereby limiting surface channel mobility. The result is a reduced rate of endocytosis and an increased density of surface KATP channels.

EHD2 does not stimulate re-expression of KATP channels from the ERC

Surface expression can potentially be increased by stimulating the delivery of protein cargo from the ERC to the membrane. As EHD stimulates surface expression, we investigated this possibility by using immunofluorescence confocal microscopy. We found that KATP channels accumulated in the ERC in the presence of a dominant interfering Rab11 mutant—GFP-Rab11-S25N—that is known to prevent the exit of cargo from the ERC. EHD2 also caused the accumulation of KATP channels in the ERC. At face value, this experiment suggests that, similar to GFP-Rab11-S25N, EHD2 inhibits the exit of the channel from the ERC. There are several arguments to be made against this possibility. First, EHD2 and Rab11 do not colocalize (10) as would be expected if these 2 proteins played key roles in this subcellular compartment. Second, Rab11-S25N causes the aggregation of ERC vesicles within the perinuclear region (Supplemental Fig. 3A) (32), whereas EHD2-G65R did not share this effect (Supplemental Fig. 3A). Third, whereas Rab11-S25N increases ERC vesicle size (33), such a phenomenon was not observed for EHD2-G65R (Supplemental Fig. 3) or EHD2 (data not shown). Fourth, wild-type EHD2 did not rescue the trafficking defects that were caused by Rab11-S25N (Fig. 5). Finally, Rab11-S25N decreases KATP channel mean patch current (Supplemental Fig. 4), whereas EHD2 increases the current (Fig. 1). We therefore conclude that the effect of EHD2 on KATP channel ERC localization is not as a consequence of a direct effect on the ERC, but rather is secondary to other upstream trafficking mechanisms, such as stabilizing channels at the surface membrane.

EHD2 enhances KATP channel surface density by stabilizing caveolae and limiting endocytosis

Caveolae are small (50–100 nm), lipid raft-like invaginations of the plasma membrane. Although initially thought to be dynamic endocytic carriers, live-cell imaging studies have demonstrated that caveolae are inherently stable membrane structures (34). The role of EHD2 in stabilizing membrane invagination and caveolar structures is well documented. Proteomic analysis of caveolae that were isolated from adipocytes identified EHD2 as a caveolar component (35). Moreover, transfected GFP-EHD2 localizes to and restrains caveolar dynamics (21, 22, 36). In the absence of EHD2, live-cell imaging indicates that caveolae became more dynamic, exhibiting increased motility (21). The mechanism by which EHD2 restricts caveolar mobility is by the negative regulation of dynamin, which otherwise may pinch off the vesicles (37). EHD2 may also recruit the F-BAR domain-containing protein, syndapin2, which promotes membrane curvature (36). Several observations are consistent with the concept that surface KATP channels, which are present in caveolae, are stabilized by EHD2. First, we observed colocalization of KATP channel subunits with the caveolar marker, caveolin3. This observation is consistent with published reports that have localized KATP channels to caveolae (20, 38). Second, with density gradient flotation assays, we found a proportion of KATP channel subunits in the same membrane fractions as the caveolar marker, caveolin3. Third, disrupting caveolae by cholesterol depletion with MβCD shifted both proteins to denser fractions, which would increase the mobility of channels and their availability for endocytosis. In support of this, MβCD has been reported to reduce KATP channel density (39). Fourth, similar to MβCD, we found that disrupting EHD2 function in cardiomyocytes with Ad-EHD2-G65R also shifted caveolin3 and KATP channels to denser membrane fractions. Overall, we conclude that EHD2 stabilizes caveolae, which contain KATP channels. The result is a decrease in KATP channel mobility (Fig. 7D), which renders the channel less susceptible to endocytosis and increases surface KATP channel density.

Does EHD2 directly affect endocytosis?

We observed that EHD2 decreases the rate of KATP channel endocytosis. This observation can be fully explained by the caveolae hypothesis described in the preceding section, in which surface density is increased because channels are stabilized in caveolar structures. Our data also demonstrate that the EHD2-G65R–mediated decrease of KATP channel density is prevented by pitstop2, an inhibitor of clathrin-mediated endocytosis. This observation is consistent with the interpretation that EHD2-G65R displaces KATP channels from caveolae, which increases their surface mobility and, consequently, their susceptibility to clathrin-mediated endocytosis; however, these data do not rule out the possibility that EHD2 directly regulates endocytosis. In fact, EHD2 has been described to physically interact with adaptor protein 2 subunits (40), but the functional consequence of this interaction has not been described. EHD2 may also regulate actin nucleation—needed for endocytosis—by interacting with actin-binding partner proteins, such as EHBP1 (EHD2-binding protein 1), which, in turn, promotes actin dynamics by recruiting Arp2/3 (11). EHD2 has also been described to bind to the serine/threonine kinase, Nek3 (13), which activates members of the Vav protein family (41). Vav proteins, in turn, activate small Rho GTPases, including Rac1, which is a key cytoskeletal regulatory protein. Given the role of Arp2/3 and Rac1 in actin nucleation, which promotes endocytosis, one would expect EHD2 to promote internalization. This idea is supported by the finding that the disruption of EHD2 or EHBP1 by small interfering RNA–mediated gene silencing inhibits endocytosis of transferrin and GLUT4 (11); however, another study found that EHD2 actually inhibits the endocytosis of transferrin (13). On balance, therefore, the evidence that directly links EHD2 to KATP channel endocytosis is not strong.

EHD2 regulates endogenous cardiomyocyte KATP channels and participates in cardioprotection

Each of the 4 EHDx family members of trafficking proteins are expressed in the heart (14). To date, only EHD3 has been described to have a functional role in this tissue. EHD3 binds to ankyrins, which, in turn, stabilizes the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (NCX1) and Ca2+ channels at the sarcolemma (14, 15). Expression of EHD2 has previously been noted in isolated adult cardiac myocytes, including human, with subcellular localization to perinuclear regions and z lines (14). Our data—obtained with 2 separate Abs—demonstrate that EHD2 is expressed at the z lines, but that more intense staining occurs at the myocyte periphery (Supplemental Fig. 5), where it partially colocalizes with Kir6.2. Others have also previously noted a plasmalemmal localization of EHD2 (22, 23). Viral delivery of EHD2-G65R decreases native KATP channel current density, which is consistent with our findings in transfected cells. We and others have shown that sarcolemmal KATP channels are linked to the protective effect of ischemic preconditioning (2, 3). As EHD2-G65R decreases endogenous ventricular KATP channel current, we predict that it would also diminish the protective effect of ischemic preconditioning. Indeed, our data indicate this to be the case, which leads to the suggestion that trafficking proteins, such as EHD2, may represent future targets for treating cardiac disorders.

CONCLUSIONS

There is an emerging role for the trafficking of ion channels as an important regulator of function. Understanding the endocytic recycling pathways and the individual trafficking proteins involved is a major step in developing strategies to regulate, or possibly correct defects in, channel surface expression. The EHD protein family only recently came into focus as regulators of endocytic recycling. Our findings provide new insights into the function of EHD2 to regulate KATP channel trafficking.

Supplementary Material

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the U.S. National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (Grant HL126905; to W.A.C.) and an American Heart Association Postdoctoral Fellowship Award (17POST33370050; to H.Q.Y.).

Glossary

- EHD

Eps15 homology domain-containing protein

- ERC

endocytic recycling compartment

- HA

hemagglutinin

- KATP channel

ATP-sensitive K+ channel

- MβCD

methyl-β-cyclodextrin

- PFA

paraformaldehyde

Footnotes

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

H. Q. Yang was involved in the study design, data collection and analysis, and writing and revising the manuscript; K. Jana produced data; and M. J. Rindler and W. A. Coetzee were involved in all aspects of the study, including conception, design, data analysis and interpretation, and writing and revising the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Nichols C. G. (2006) KATP channels as molecular sensors of cellular metabolism. Nature 440, 470–476https://doi.org/10.1038/nature04711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Foster M. N., Coetzee W. A. (2016) KATP channels in the cardiovascular system. Physiol. Rev. 96, 177–252https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00003.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang H. Q., Foster M. N., Jana K., Ho J., Rindler M. J., Coetzee W. A. (2016) Plasticity of sarcolemmal KATP channel surface expression: relevance during ischemia and ischemic preconditioning. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 310, H1558–H1566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zingman L. V., Hodgson D. M., Bast P. H., Kane G. C., Perez-Terzic C., Gumina R. J., Pucar D., Bienengraeber M., Dzeja P. P., Miki T., Seino S., Alekseev A. E., Terzic A. (2002) Kir6.2 is required for adaptation to stress. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 13278–13283https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.212315199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hong M., Kefaloyianni E., Bao L., Malester B., Delaroche D., Neubert T. A., Coetzee W. A. (2011) Cardiac ATP-sensitive K+ channel associates with the glycolytic enzyme complex. FASEB J. 25, 2456–2467https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.10-176669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kefaloyianni E., Lyssand J. S., Moreno C., Delaroche D., Hong M., Fenyö D., Mobbs C. V., Neubert T. A., Coetzee W. A. (2013) Comparative proteomic analysis of the ATP-sensitive K+ channel complex in different tissue types. Proteomics 13, 368–378https://doi.org/10.1002/pmic.201200324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lin S. X., Grant B., Hirsh D., Maxfield F. R. (2001) Rme-1 regulates the distribution and function of the endocytic recycling compartment in mammalian cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 3, 567–572https://doi.org/10.1038/35078543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Naslavsky N., Rahajeng J., Sharma M., Jovic M., Caplan S. (2006) Interactions between EHD proteins and Rab11-FIP2: a role for EHD3 in early endosomal transport. Mol. Biol. Cell 17, 163–177https://doi.org/10.1091/mbc.E05-05-0466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Naslavsky N., McKenzie J., Altan-Bonnet N., Sheff D., Caplan S. (2009) EHD3 regulates early-endosome-to-Golgi transport and preserves Golgi morphology. J. Cell Sci. 122, 389–400https://doi.org/10.1242/jcs.037051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.George M., Ying G., Rainey M. A., Solomon A., Parikh P. T., Gao Q., Band V., Band H. (2007) Shared as well as distinct roles of EHD proteins revealed by biochemical and functional comparisons in mammalian cells and C. elegans. BMC Cell Biol. 8, 3.https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2121-8-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guilherme A., Soriano N. A., Bose S., Holik J., Bose A., Pomerleau D. P., Furcinitti P., Leszyk J., Corvera S., Czech M. P. (2004) EHD2 and the novel EH domain binding protein EHBP1 couple endocytosis to the actin cytoskeleton. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 10593–10605https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M307702200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daumke O., Lundmark R., Vallis Y., Martens S., Butler P. J., McMahon H. T. (2007) Architectural and mechanistic insights into an EHD ATPase involved in membrane remodelling. Nature 449, 923–927https://doi.org/10.1038/nature06173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benjamin S., Weidberg H., Rapaport D., Pekar O., Nudelman M., Segal D., Hirschberg K., Katzav S., Ehrlich M., Horowitz M. (2011) EHD2 mediates trafficking from the plasma membrane by modulating Rac1 activity. Biochem. J. 439, 433–442https://doi.org/10.1042/BJ20111010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gudmundsson H., Hund T. J., Wright P. J., Kline C. F., Snyder J. S., Qian L., Koval O. M., Cunha S. R., George M., Rainey M. A., Kashef F. E., Dun W., Boyden P. A., Anderson M. E., Band H., Mohler P. J. (2010) EH domain proteins regulate cardiac membrane protein targeting. Circ. Res. 107, 84–95https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.216713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Curran J., Musa H., Kline C. F., Makara M. A., Little S. C., Higgins J. D., Hund T. J., Band H., Mohler P. J. (2015) Eps15 homology domain-containing protein 3 regulates cardiac T-type Ca2+ channel targeting and function in the atria. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 12210–12221https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M115.646893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zerangue N., Schwappach B., Jan Y. N., Jan L. Y. (1999) A new ER trafficking signal regulates the subunit stoichiometry of plasma membrane KATP channels. Neuron 22, 537–548https://doi.org/10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80708-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bao L., Hadjiolova K., Coetzee W. A., Rindler M. J. (2011) Endosomal KATP channels as a reservoir after myocardial ischemia: a role for SUR2 subunits. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 300, H262–H270https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpheart.00857.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Turrell H. E., Rodrigo G. C., Norman R. I., Dickens M., Standen N. B. (2011) Phenylephrine preconditioning involves modulation of cardiac sarcolemmal KATP current by PKC delta, AMPK and p38 MAPK. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 51, 370–380https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yjmcc.2011.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ullrich O., Reinsch S., Urbé S., Zerial M., Parton R. G. (1996) Rab11 regulates recycling through the pericentriolar recycling endosome. J. Cell Biol. 135, 913–924https://doi.org/10.1083/jcb.135.4.913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garg V., Jiao J., Hu K. (2009) Regulation of ATP-sensitive K+ channels by caveolin-enriched microdomains in cardiac myocytes. Cardiovasc. Res. 82, 51–58https://doi.org/10.1093/cvr/cvp039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stoeber M., Stoeck I. K., Hänni C., Bleck C. K., Balistreri G., Helenius A. (2012) Oligomers of the ATPase EHD2 confine caveolae to the plasma membrane through association with actin. EMBO J. 31, 2350–2364https://doi.org/10.1038/emboj.2012.98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morén B., Shah C., Howes M. T., Schieber N. L., McMahon H. T., Parton R. G., Daumke O., Lundmark R. (2012) EHD2 regulates caveolar dynamics via ATP-driven targeting and oligomerization. Mol. Biol. Cell 23, 1316–1329https://doi.org/10.1091/mbc.E11-09-0787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ludwig A., Howard G., Mendoza-Topaz C., Deerinck T., Mackey M., Sandin S., Ellisman M. H., Nichols B. J. (2013) Molecular composition and ultrastructure of the caveolar coat complex. PLoS Biol. 11, e1001640.https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1001640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsuchida A., Liu Y., Liu G. S., Cohen M. V., Downey J. M. (1994) alpha 1-adrenergic agonists precondition rabbit ischemic myocardium independent of adenosine by direct activation of protein kinase C. Circ. Res. 75, 576–585https://doi.org/10.1161/01.RES.75.3.576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maxfield F. R., McGraw T. E. (2004) Endocytic recycling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 5, 121–132https://doi.org/10.1038/nrm1315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hu K., Huang C. S., Jan Y. N., Jan L. Y. (2003) ATP-sensitive potassium channel traffic regulation by adenosine and protein kinase C. Neuron 38, 417–432https://doi.org/10.1016/S0896-6273(03)00256-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mankouri J., Taneja T. K., Smith A. J., Ponnambalam S., Sivaprasadarao A. (2006) Kir6.2 mutations causing neonatal diabetes prevent endocytosis of ATP-sensitive potassium channels. EMBO J. 25, 4142–4151https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.emboj.7601275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bruederle C. E., Gay J., Shyng S. L. (2011) A role of the sulfonylurea receptor 1 in endocytic trafficking of ATP-sensitive potassium channels. Traffic 12, 1242–1256https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0854.2011.01227.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manna P. T., Smith A. J., Taneja T. K., Howell G. J., Lippiat J. D., Sivaprasadarao A. (2010) Constitutive endocytic recycling and protein kinase C-mediated lysosomal degradation control KATP channel surface density. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 5963–5973https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M109.066902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sierra A., Zhu Z., Sapay N., Sharotri V., Kline C. F., Luczak E. D., Subbotina E., Sivaprasadarao A., Snyder P. M., Mohler P. J., Anderson M. E., Vivaudou M., Zingman L. V., Hodgson-Zingman D. M. (2013) Regulation of cardiac ATP-sensitive potassium channel surface expression by calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 1568–1581https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M112.429548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Park S. H., Ryu S. Y., Yu W. J., Han Y. E., Ji Y. S., Oh K., Sohn J. W., Lim A., Jeon J. P., Lee H., Lee K. H., Lee S. H., Berggren P. O., Jeon J. H., Ho W. K. (2013) Leptin promotes KATP channel trafficking by AMPK signaling in pancreatic β-cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 110, 12673–12678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moore R. H., Millman E. E., Alpizar-Foster E., Dai W., Knoll B. J. (2004) Rab11 regulates the recycling and lysosome targeting of beta2-adrenergic receptors. J. Cell Sci. 117, 3107–3117https://doi.org/10.1242/jcs.01168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sorvina A., Shandala T., Brooks D. A. (2016) Drosophila Pkaap regulates Rab4/Rab11-dependent traffic and Rab11 exocytosis of innate immune cargo. Biol. Open 5, 678–688https://doi.org/10.1242/bio.016642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thomsen P., Roepstorff K., Stahlhut M., van Deurs B. (2002) Caveolae are highly immobile plasma membrane microdomains, which are not involved in constitutive endocytic trafficking. Mol. Biol. Cell 13, 238–250https://doi.org/10.1091/mbc.01-06-0317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brasaemle D. L., Dolios G., Shapiro L., Wang R. (2004) Proteomic analysis of proteins associated with lipid droplets of basal and lipolytically stimulated 3T3-L1 adipocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 46835–46842https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M409340200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hansen C. G., Howard G., Nichols B. J. (2011) Pacsin 2 is recruited to caveolae and functions in caveolar biogenesis. J. Cell Sci. 124, 2777–2785https://doi.org/10.1242/jcs.084319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jakobsson J., Ackermann F., Andersson F., Larhammar D., Löw P., Brodin L. (2011) Regulation of synaptic vesicle budding and dynamin function by an EHD ATPase. J. Neurosci. 31, 13972–13980https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1289-11.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sampson L. J., Hayabuchi Y., Standen N. B., Dart C. (2004) Caveolae localize protein kinase A signaling to arterial ATP-sensitive potassium channels. Circ. Res. 95, 1012–1018https://doi.org/10.1161/01.RES.0000148634.47095.ab [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jiao J., Garg V., Yang B., Elton T. S., Hu K. (2008) Protein kinase C-epsilon induces caveolin-dependent internalization of vascular adenosine 5′-triphosphate-sensitive K+ channels. Hypertension 52, 499–506https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.110817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Park S. Y., Ha B. G., Choi G. H., Ryu J., Kim B., Jung C. Y., Lee W. (2004) EHD2 interacts with the insulin-responsive glucose transporter (GLUT4) in rat adipocytes and may participate in insulin-induced GLUT4 recruitment. Biochemistry 43, 7552–7562https://doi.org/10.1021/bi049970f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miller S. L., DeMaria J. E., Freier D. O., Riegel A. M., Clevenger C. V. (2005) Novel association of Vav2 and Nek3 modulates signaling through the human prolactin receptor. Mol. Endocrinol. 19, 939–949https://doi.org/10.1210/me.2004-0443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.