Abstract

Objectives

Prevention of unplanned pregnancy is a crucial aspect of preventing mother-to-child HIV transmission. There are few data investigating how HIV status and use of antiretroviral therapy (ART) may influence pregnancy planning in high HIV burden settings. Our objective was to examine the prevalence and determinants of unplanned pregnancy among HIV-positive and HIV-negative women in Cape Town, South Africa.

Design

Cross-sectional analysis.

Settings

Single primary-level antenatal care clinic in Cape Town, South Africa.

Participants

HIV-positive and HIV-negative pregnant women, booking for antenatal care from March 2013 to August 2015, were included.

Main outcome measures

Unplanned pregnancy was measured at the first antenatal care visit using the London Measure of Unplanned Pregnancy (LMUP). Analyses examined LMUP scores across four groups of participants defined by their HIV status, awareness of their HIV status prior to the current pregnancy and/or whether they were using antiretroviral therapy (ART) prior to the current pregnancy.

Results

Among 2105 pregnant women (1512 HIV positive; 593 HIV negative), median age was 28 years, 43% were married/cohabiting and 20% were nulliparous. Levels of unplanned pregnancy were significantly higher in HIV-positive versus HIV-negative women (50% vs 33%, p<0.001); and highest in women who were known HIV positive but not on ART (53%). After adjusting for age, parity and marital status, unplanned pregnancy was most common among women newly diagnosed and women who were known HIV positive but not on ART (compared with HIV-negative women, adjusted OR (aOR): 1.43; 95% CI 1.05 to 1.94 and aOR: 1.57; 95% CI 1.13 to 2.15, respectively). Increased parity and younger age (<24 years) were also associated with unplanned pregnancy (aOR: 1.42; 95% CI 1.25 to 1.60 and aOR: 1.83; 95% CI 1.23 to 2.74, respectively).

Conclusions

We observed high levels of unplanned pregnancy among HIV-positive women, particularly among those not on ART, suggesting ongoing missed opportunities for improved family planning and counselling services for HIV-positive women.

Keywords: unplanned pregnancy, contraception, family planning, HIV, women

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is one of the first studies to examine pregnancy intentions in a large sample of HIV-positive and HIV-negative women aged 18–44 in South Africa.

This study used a robust pregnancy intention instrument fairly new to our study setting; the London Measure of Unplanned Pregnancy, to measure levels of unplanned pregnancy.

The cross-sectional design of this study means that causal associations of unplanned pregnancy could not be determined.

Participants were selected using convenience sampling from a single urban setting, therefore findings may not be generalisable to other resource-limited settings.

Our retrospective self-reported measurement of pregnancy intentions after pregnancy recognition and entering antenatal care may have increased acceptance of the pregnancy and resulted in over reporting of planned pregnancy.

Introduction

Efforts to eliminate mother-to-child transmission of HIV (MTCT) continue to escalate globally and advances in prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) services have led to significant reductions in the number of new paediatric infections across resource-limited settings including Africa.1 In South Africa, over 95% of HIV-infected pregnant women receive triple drug antiretroviral therapy (ART) during pregnancy and breast feeding and the rate of MTCT declined from 8% in 2008 to 1.3% in 2016.1 2

South Africa has the highest number of individuals living with HIV worldwide with up to 18.8% prevalence among women of childbearing age.3 HIV prevalence is particularly high among pregnant women, with almost 30% of those seeking antenatal care (ANC) testing HIV positive nationally.4 Despite the substantial efforts of national PMTCT programmes in high-burden countries, new paediatric infections remain a major public health concern.2 5

Even where ART is widely available to pregnant and breastfeeding women, the timing and planning of a pregnancy may be important determinants of MTCT.6 7 Unplanned pregnancies predict maternal health behaviours during pregnancy and in the postpartum period, including late presentation for ANC, reduced ART adherence and suboptimal breastfeeding practices.7–10 Preventing unplanned pregnancies among HIV-positive women through addressing the unmet need for family planning is a relatively low-cost, effective method for preventing new paediatric HIV infections.11–13 Contraceptive use is high in South Africa with an estimated 65% of sexually active women using at least one method and studies have shown an association between contraception and pregnancy intentions.14 15 Modern contraceptive methods are freely available at public sector healthcare facilities in South Africa with short-acting methods—primarily injectable contraceptives being the most commonly used by sexually active women in South Africa.16

An estimated 40% of all pregnancies worldwide and 35% of pregnancies in Africa are unplanned.17 In comparison, 35%–65% of pregnancies among HIV-positive women across sub-Saharan Africa may be unplanned,18–21 with up to two-thirds of HIV-positive women reporting unplanned pregnancies in South Africa.14 22 However, the current evidence for the association between HIV status, ART use and unplanned pregnancy remains inconsistent.23 While some previous studies documented higher levels of unplanned pregnancies among HIV-positive compared with HIV-negative women,20 others found no association between HIV status and unplanned pregnancy.24

Women who are not aware of their HIV status prior to conception may be more likely to have an unplanned pregnancy. Findings from a recent study in Botswana demonstrated an almost twofold increase in the likelihood of unplanned pregnancy among women unaware of their HIV-positive serostatus prior to conception compared with those who were aware.19 In contrast, there is also some evidence to suggest that pregnancy incidence is significantly higher for women after ART initiation compared with those not on ART, and approximately 60% of HIV-positive women on ART experience an unplanned pregnancy.18 22 25 There are few robust data on pregnancy planning among HIV-positive women initiating ART in the current era of PMTCT. In this context, there is a clear need for further insights into pregnancy planning and associated factors among HIV-positive women in high HIV burden settings. To address this, we examined the prevalence and determinants of unplanned pregnancy among HIV-positive and HIV-negative women in Cape Town, South Africa.

Methods

Study setting and design

This cross-sectional analysis used data obtained from the enrolment visit of the Maternal-Child Health Antiretroviral Therapy (MCH-ART) study, a multicomponent implementation science study investigating optimal strategies for delivering ART services to HIV-positive pregnant and postpartum women (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01933477). The study took place in the community of Gugulethu, a historically disadvantaged community with a high burden of HIV. The MCH-ART study methods have been described in detail previously.26 Briefly, 1554 HIV-positive pregnant women above 18 years of age were consecutively enrolled at their first ANC visit. In addition, this analysis used data from a parallel substudy to MCH-ART, the HIV-unexposed, uninfected (HU2) study which enrolled 612 HIV-negative women attending their first ANC visit, to provide a comparison group.26 For this analysis we restricted the sample to 1512 HIV-positive women and 593 HIV-negative women who had complete data on pregnancy planning.

Data collection

Following enrolment at their first ANC visit, all participants completed a structured interviewer-administered questionnaire in their language of choice—isiXhosa or English. Information collected included basic sociodemographic characteristics, medical history, pregnancy intentions and contraceptive use. All measures were translated into isiXhosa, and back-translated into English by a second translator, to ensure accuracy.

Contraceptive use was defined as any contraceptive method used in the 12 months prior to pregnancy recognition. A categorical variable was created for socioeconomic status (SES) based on employment status, years of education, housing type and number of amenities in the household, and was categorised into quartiles.27 Pregnancy intentions were assessed using a validated 6-item questionnaire, the London Measure of Unplanned Pregnancy (LMUP). This instrument asked women to report the circumstances of their most recent pregnancy, with each item in the tool scored 0, 1 or 2 according to published scoring guidelines.28 Womens' scores were summed across all six items, resulting in a total score from 0 to 12 with each point increase representing an increase in pregnancy intention. Total LMUP scores were divided into categories of pregnancy intentions: unplanned (0–3), ambivalent (4–9) and planned (10–12), based on the scoring used in the original development of the scale.28 A separate single-item, three-level response question (current pregnancy intended: yes, no, unsure) was used to examine the performance of the LMUP.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using STATA V.12.0 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA). In this analysis, participants were categorised into four groups based on routine public sector HIV testing at entry into ANC, and self-reported ART use: (1) known HIV positive and established on ART; (2) known HIV positive but not on ART; (3) newly diagnosed HIV positive during the current pregnancy; and (4) HIV negative, used as the reference category. Sociodemographic characteristics at enrolment were compared across these four groups. Cronbach’s α was used to assess the reliability of the isiXhosa translated LMUP in this context, and bivariate analysis using a χ2 test compared the isiXhosa LMUP with the single three-level response question. Associations between characteristics at enrolment and unplanned pregnancy were explored using χ2 and Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables, and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests for continuous variables. A multivariable log-binomial regression model was built to examine independent predictors of unplanned pregnancy, with maternal age and SES considered as a priori confounders. Model fit was explored using Akaike’s information criterion and a priori hypothesis about confounders namely age and SES. For the log-binomial regression analysis, LMUP scores were dichotomised into unplanned/ambivalent (LMUP score 0–9) versus planned pregnancy (LMUP score 10–12).

Results

A total of 2105 women (1512 HIV positive and 593 HIV negative), enrolled between March 2013 and August 2015, were included in this analysis. The median age of participants was 28 (IQR 24–33) years, 29% had completed high school, 61% were unemployed and 43% were married or cohabiting. Across all groups, 20% were nulliparous (table 1). Among the overall group of HIV-positive women, 37% were on ART at entry into ANC, 29% were not on ART but previously diagnosed with HIV and 34% were newly diagnosed. Compared with HIV-negative women, HIV-positive women were slightly older, less likely to be employed and more likely to live in informal housing. Among the HIV-infected women, those who were newly diagnosed were more likely to be younger, have completed high school and less likely to be married/cohabiting.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of women booking for antenatal care stratified by HIV status and antiretroviral treatment

| Womens' characteristics | Total (n=2105) |

Known HIV+ on ART (n=556) |

Known HIV+ not on ART (n=444) |

Newly diagnosed (n=512) |

HIV negative (n=593) |

P values* |

| Age (years) | 28 (24–33) | 31 (28–34) | 29 (26–32) | 26 (22–30) | 27 (23–32) | |

| Age category | ||||||

| 18–24 | 532 (25) | 51 (9) | 77 (17) | 187 (37) | 217 (37) | <0.001 |

| 25–34 | 1235 (59) | 368 (66) | 307 (69) | 276 (54) | 284 (48) | |

| 35–44 | 338 (16) | 137 (25) | 60 (14) | 49 (9) | 92 (15) | |

| Parity | 1 (1–2) | 2 (1–2) | 2 (1–2) | 1 (0–2) | 1 (0–2) | <0.001 |

| Completed high school | 601 (29) | 109 (20) | 103 (23) | 359 (70) | 236 (40) | <0.001 |

| Employment status | ||||||

| Employed | 833 (39) | 210 (38) | 144 (32) | 200 (39) | 275 (46) | <0.001 |

| Housing | ||||||

| Informal | 1100 (52) | 318 (57) | 236 (53) | 270 (53) | 276 (47) | 0.005 |

| Socioeconomic status (SES) | ||||||

| Low | 524 (25) | 166 (30) | 132 (30) | 139 (27) | 87 (15) | |

| Low-moderate | 469 (22) | 134 (24) | 103 (23) | 108 (21) | 124 (21) | |

| Moderate-high | 565 (27) | 164 (30) | 116 (26) | 127 (25) | 158 (27) | |

| High | 541 (26) | 92 (16) | 93 (21) | 138 (27) | 218 (37) | |

| Married/cohabiting | 882 (43) | 258 (47) | 200 (47) | 180 (36) | 244 (42) | <0.001 |

| Disclosed HIV status to current partner | 816 (55) | 462 (84) | 289 (67) | 65 (13) | NA | <0.001 |

| Single-item question—current pregnancy | ||||||

| Unintended | 1347 (64) | 310 (56) | 291 (66) | 343 (67) | 403 (68) | <0.001 |

| Intended | 752 (36) | 244 (44) | 152 (34) | 167 (33) | 189 (32) | |

| Unsure | 5 (0) | 2 (0) | 1 (0) | 2 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Used contraceptives in the past 12 months | 1459 (69) | 414 (74) | 287 (65) | 320 (63) | 438 (74) | <0.001 |

| Contraceptive method used in the past 12 months | ||||||

| None | 646 (31) | 142 (26) | 157 (36) | 192 (38) | 155 (26) | <0.001 |

| Oral contraceptive | 57 (3) | 5 (1) | 8 (2) | 12 (3) | 32 (5) | |

| Injectable | 752 (36) | 152 (27) | 139 (31) | 155 (30) | 306 (52) | |

| IUD | 8 (0) | 0 | 2 | 2 (0) | 4 (1) | |

| Sterilisation | 1 (0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0) | |

| Condom | 641 (30) | 257 (46) | 138 (31) | 151 (29) | 95 (16) | |

| Discussed family planning with partner in the past 12 months | 964 (49) | 275 (54) | 198 (49) | 235 (50) | 256 (44) | 0.006 |

Values are given as number (percentage) or median (IQR).

*Χ2 or Fisher’s exact tests were used to assess bivariate associations.

ART, antiretroviral therapy; HIV+, HIV positive; IUD, intrauterine device; NA, not applicable.

Overall, 69% of women reported using at least one contraceptive method in the 12 months prior to pregnancy recognition. HIV-positive women on ART and HIV-negative women were more likely to report using a contraceptive method than those who were HIV positive not on ART or newly diagnosed (74% and 74% vs 65% and 63%, p<0.001). Injectable hormonal contraceptives were the most common contraceptive methods used by both HIV-positive and HIV-negative women, followed by condom use; hormonal injections were more commonly reported by HIV-negative women.

The LMUP performed well (Cronbach’s α: 0.84), with similar levels of internal consistency across HIV status. The LMUP performed well in comparison to the χ2 test assessing the single-item three-level response question on pregnancy intention: 99% of women who had an unplanned pregnancy based on LMUP score also reported unplanned pregnancies based on the three-level response question; 91% of women classified as having a planned pregnancy by the LMUP score responded similarly to the three-level response question (p<0.001; table 2). Item-rest correlations were ≥0.7 for all items of the LMUP.

Table 2.

The London Measure of Unplanned Pregnancy (LMUP) intention scores in comparison with the single item measure of pregnancy intentions

| Single-itemmeasure of pregnancy intention | London Measure of Unplanned Pregnancy | |||

| Total (n=2105) |

Unplanned (n=959) |

Ambivalent (n=607) |

Planned (n=539) |

|

| No | 1347 (64) | 950 (99) | 346 (57) | 51 (9) |

| Yes | 752 (36) | 8 (1) | 256 (42) | 488 (91) |

| Unsure | 5 (0) | 0 (0) | 5 (1) | 0 (0) |

Values are given as number (percentage).

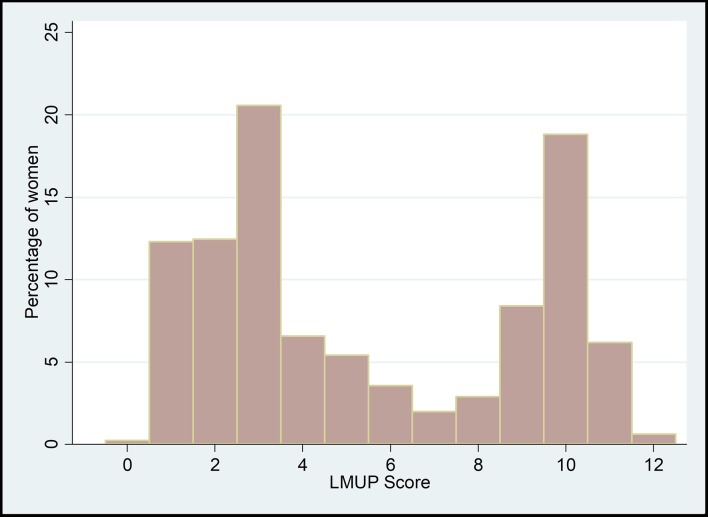

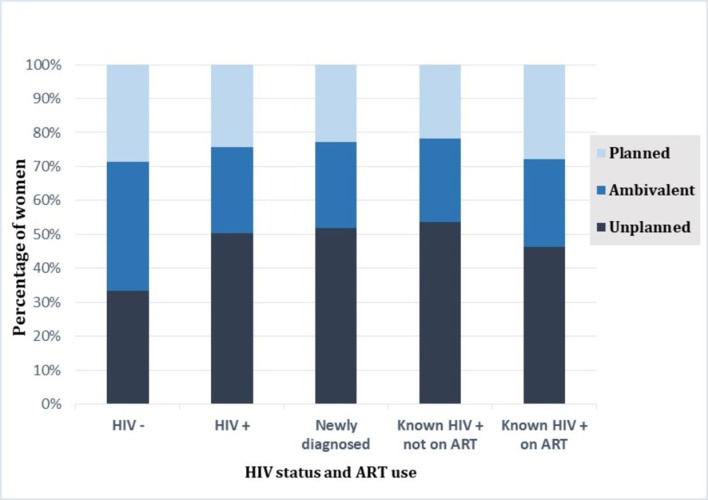

The median LMUP score in the total sample was 4 (IQR 3–10; figure 1). Nearly half (46%) of all pregnancies were unplanned (LMUP score: 0–3); 29% of women had ambivalent pregnancy intentions (LMUP score: 4–9); and 25% had a planned pregnancy (LMUP score: 10–12). Compared with HIV-positive women, fewer HIV-negative women experienced an unplanned pregnancy (33% vs 50%, p<0.001). Across the four comparison groups, the highest level of unplanned pregnancy was observed in women who were HIV positive not on ART while HIV-negative women were the least likely to report an unplanned pregnancy (54% vs 33%, p<0.001; figure 2).

Figure 1.

The distribution of the London Measure of Unplanned Pregnancy (LMUP) scores in HIV-positive and HIV-negative pregnant women booking for antenatal care, 2013–2015.

Figure 2.

The London Measure of Unplanned Pregnancy (LMUP) score categories stratified by HIV status and antiretroviral therapy (ART) use.

Women with planned pregnancies were older and more likely to be married/cohabiting. Among those with an unplanned pregnancy, 75% (721/959) reported using at least one contraceptive method in the year prior to pregnancy recognition, compared with 58% (257/539) of those reporting a planned pregnancy. Women who had discussed family planning with their partner in the past year, and HIV-positive women who had disclosed their HIV status to their male partner, were less likely to have an unplanned pregnancy (table 3).

Table 3.

Demographic characteristics of participants stratified by the London Measure of Unplanned Pregnancy (LMUP) intention score categories

| Women’s characteristics | Total (n=2105) |

Unplanned (n=959) |

Ambivalent (n=607) |

Planned (n=539) |

P values* |

| Age (years) | 28 (24–33) | 28 (24–32) | 28 (25–33) | 29 (25–33) | <0.001 |

| Age category | |||||

| 18–24 | 532 (25) | 274 (29) | 150 (25) | 108 (20) | |

| 25–34 | 1235 (59) | 548 (57) | 356 (59) | 331 (61) | 0.004 |

| 35–44 | 338 (16) | 137 (14) | 101 (17) | 100 (19) | |

| Parity | 1 (1–2) | 1 (1–2) | 1 (1–2) | 1 (1–2) | <0.001 |

| Completed high school | |||||

| Yes | 601 (29) | 236 (25) | 205 (34) | 160 (30) | <0.001 |

| Level of education | |||||

| Primary | 73 (3) | 38 (4) | 16 (3) | 19 (3) | |

| Secondary | 1973 (94) | 889 (93) | 574 (94) | 510 (95) | 0.309 |

| Tertiary | 59 (3) | 32 (3) | 17 (3) | 10 (2) | |

| Employment status | |||||

| Employed | 833 (39) | 352 (37) | 265 (44) | 212 (39) | 0.022 |

| Housing | |||||

| Informal | 1100 (52) | 476 (50) | 307 (51) | 317 (59) | 0.002 |

| Socioeconomic status | |||||

| Low | 524 (25) | 274 (29) | 118 (19) | 132 (25) | |

| Low-moderate | 469 (22) | 195 (20) | 143 (24) | 131 (24) | 0.004 |

| Moderate-high | 565 (27) | 251 (26) | 167 (28) | 147 (27) | |

| High | 541 (26) | 238 (25) | 175 (29) | 128 (24) | |

| Married/cohabiting | |||||

| Yes | 882 (43) | 273 (30) | 242 (40) | 367 (69) | <0.001 |

| Disclosed HIV status to current partner (HIV+ women) | 816 (55) | 367 (50) | 214 (56) | 235 (64) | <0.001 |

| Intention of current pregnancy | |||||

| Unintended | 1347 (64) | 950 (99) | 346 (57) | 51 (9) | |

| Intended | 752 (36) | 8 (1) | 256 (42) | 488 (91) | <0.001 |

| Unsure | 5 (0) | 0 (0) | 5 (1) | 0 (0) | |

| Used contraceptive in the past 12 months | 1459 (69) | 721 (75) | 427 (70) | 311 (58) | <0.001 |

| Contraceptive method used in the past 12 months | |||||

| None | 646 (31) | 238 (25) | 180 (30) | 228 (42) | |

| Oral contraceptive | 57 (3) | 26 (3) | 16 (3) | 15 (3) | |

| Injectable | 752 (36) | 335 (35) | 233 (38) | 184 (34) | <0.001 |

| IUD | 8 (0) | 4 (0) | 2 (0) | 2 (0) | |

| Sterilisation | 1 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Condom | 641 (30) | 356 (37) | 175 (29) | 110 (20) | |

| Discussed family planning with partner in the past 12 months | 964 (49) | 234 (26) | 347 (60) | 383 (78) | <0.001 |

Values are given as number (percentage) or median (IQR).

*Χ2 or Fisher’s exact tests were used to assess bivariate associations.

IUD, intrauterine device.

In a multivariable log-binomial regression model adjusted for age, parity, relationship status and SES, unplanned pregnancy was associated with HIV-ART status. Compared with HIV-negative women, HIV-positive women not receiving ART were most likely to have an unplanned pregnancy (adjusted OR (aOR): 1.57; 95% CI 1.13 to 2.15), followed by women newly diagnosed with HIV (aOR: 1.43; 95% CI 1.05 to 1.94). There were no apparent differences in unplanned pregnancy between HIV-negative and HIV-positive women established on ART. Unplanned pregnancy was also associated with increasing parity (aOR 1.42; 95% CI 1.25 to 1.60) and younger age (compared with 35–44 years of age: 18–24 years, aOR 1.83; 95% CI 1.23 to 2.74; 25–34 years, aOR 1.29; 95% CI 0.95 to 1.75) (table 4). Recent contraceptive use and marital status (married/cohabiting) reduced the odds of unplanned pregnancy.

Table 4.

Multivariable log-binomial regression model predicting unplanned pregnancy among HIV-positive and HIV-negative women

| Variables | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||

| OR | 95% CI | P values | aOR | 95% CI | P values | |

| HIV status and ART use | ||||||

| HIV negative | ||||||

| Newly diagnosed | 1.35 | 1.03 to 1.78 | 0.028 | 1.43 | 1.05 to 1.94 | 0.020 |

| Known HIV+—no ART | 1.43 | 1.08 to 1.92 | 0.013 | 1.57 | 1.13 to 2.15 | 0.006 |

| Known HIV+—on ART | 1.03 | 0.80 to 1.34 | 0.766 | 1.10 | 0.82 to 1.47 | 0.513 |

| Age category | ||||||

| 35–44 | ||||||

| 25–34 | 1.14 | 0.88 to 1.49 | 0.309 | 1.29 | 0.95 to 1.75 | 0.099 |

| 18–24 | 1.64 | 1.20 to 2.26 | 0.002 | 1.83 | 1.23 to 2.74 | 0.003 |

| Parity | 1.07 | 0.97 to 1.17 | 0.136 | 1.42 | 1.25 to 1.60 | 0.000 |

| Married/cohabiting | ||||||

| No | ||||||

| Yes | 0.23 | 0.19 to 0.29 | 0.000 | 0.19 | 0.15 to 0.24 | 0.000 |

| Used contraceptive in the past 12 months | ||||||

| No | ||||||

| Yes | 0.73 | 0.59 to 0.91 | 0.005 | 1.94 | 1.55 to 2.43 | 0.000 |

| Socioeconomic status | ||||||

| Low | ||||||

| Low-middle | 0.86 | 0.65 to 1.15 | 0.329 | 0.79 | 0.58 to 1.08 | 0.151 |

| Middle-high | 0.95 | 0.73 to 1.26 | 0.755 | 0.74 | 0.54 to 1.00 | 0.054 |

| High | 1.08 | 0.82 to 1.44 | 0.561 | 0.84 | 0.61 to 1.16 | 0.301 |

| Finished high school | ||||||

| No | ||||||

| Yes | 0.92 | 0.74 to 1.15 | 0.499 | – | – | – |

| Employed | ||||||

| No | ||||||

| Yes | 1.00 | 0.81 to 1.22 | 0.994 | – | – | – |

| Housing | ||||||

| Informal | ||||||

| Formal | 1.42 | 1.17 to 1.73 | 0.000 | – | – | – |

| Gravidity | 1.06 | 0.97 to 1.16 | 0.201 | – | – | – |

aOR, adjusted OR; ART, antiretroviral therapy.

Including individual proxy measures of SES (employment, education and home type) in the adjusted model did not change our main findings. The aOR of an unplanned pregnancy with individual proxy measures of SES (compared with HIV-negative women) was aOR 1.43; 95% CI 1.05 to 1.94 in newly diagnosed HIV-positive women, 1.56; 95% CI 1.13 to 2.15 for previously diagnosed HIV-positive women not on ART and 1.10 95% CI 0.82 to 1.47 for previously diagnosed HIV-positive women on ART. In comparison, SES was included as a composite measure, the aOR of an unplanned pregnancy (compared with HIV-negative women) (aOR 1.43; 95% CI 1.05 to 1.94 in newly diagnosed HIV-positive women, 1.56; 95% CI 1.13 to 2.15 for previously diagnosed women not on ART and 1.10; 95% CI 0.82 to 1.47 for previously diagnosed HIV-positive women on ART).

Discussion

This study provides valuable insights into unplanned pregnancy among HIV-positive and HIV-negative women in periurban South Africa. Similar to high levels of approximately 56%–60% of unplanned pregnancy previously reported in South Africa, nearly half (46%) of all pregnancies in this study were reported as unplanned, evidence that levels of unplanned pregnancy remain unacceptably high in South Africa.14 22 Of note, levels of unplanned pregnancy were considerably higher among HIV-positive compared with HIV-negative women, particularly among those HIV-positive women not on ART. Contraceptive use mirrored these results, with the lowest levels of use reported among HIV-positive women newly diagnosed or previously diagnosed but not using ART.

This study is one of the first to examine pregnancy intentions by HIV status and ART use in South Africa. The finding that levels of unplanned pregnancy may be higher among HIV-positive compared with HIV-negative women has been previously documented in other African countries as well as in high-income countries,24 but has not been previously documented in this high HIV burden setting. Although previous research across sub-Saharan Africa has demonstrated slightly higher levels of unplanned pregnancy reaching up to 62% among HIV-positive women,14 19 21 the current study provides additional evidence that women who were not aware of their HIV status prior to conception and those HIV positive not on ART may be more likely to have an unplanned pregnancy.19 The lower prevalence of unplanned pregnancy observed among ART users compared with those not yet on ART could potentially be linked to the family planning services received by HIV-positive women engaged in care. However, one-third of women were only diagnosed HIV positive at their first ANC visit, highlighting possible missed opportunities for HIV diagnosis before pregnancy. Our finding that unplanned pregnancy is associated with younger age, increasing parity and contraceptive use in the year prior to conception is consistent with previous research.18 29 30 One study found that HIV-positive Rwandan women with two or more children were four times more likely to have an unplanned pregnancy,18 while evidence from a study in Botswana and Swaziland demonstrated that younger age (<20 years old) and low level of education (not beyond high school) were associated with an increased odds of an unplanned pregnancy.19 21 Similar findings were reported from a high-income country.30 Supporting our findings of high unplanned pregnancy levels despite high uptake of contraceptives, a South African study found up to 62% of HIV - positive and HIV- negative women experienced an unplanned pregnancy despite high contraceptive uptake of 89%.14

Reported use of contraceptives prior to unplanned pregnancy was high across all groups, similar to findings from a study conducted in Swaziland,21 and may have resulted in women being more likely to consider their pregnancy unplanned. The high level of unplanned pregnancy despite high uptake of contraceptives in our study population could potentially be linked to high contraceptive failure rates, incorrect use or poor adherence to short-acting methods, presenting an opportunity for improving family planning services. The high levels of unplanned pregnancy observed among newly diagnosed HIV-positive women and HIV-positive women not on ART suggest a potential difference in risk factors, specifically poorer health-seeking behaviours compared with HIV-positive women who have engaged with the healthcare facility and are on ART.8 10 29 Women on ART have also been shown to be twice as likely to use contraceptive methods compared with HIV-negative women.15 Even among HIV-positive women on ART in this study who routinely receive family planning services alongside HIV care services, unplanned pregnancy rate was considerably high. Levels and methods of contraceptive use differed slightly by HIV status, with use of hormonal injections more frequently reported by HIV-negative women. Similar to our findings, previous studies in Southern Africa have shown that uptake of long-acting contraceptive methods such as intrauterine devices and hormonal implants among HIV-positive women is relatively low, possibly due to low availability of these options and poorly integrated reproductive health and HIV services.22 31 32 In addition, there is a high reliance on injectable hormonal contraceptives in South Africa which may be because this method is routinely offered at no cost, after delivery in most public health sector facilities, reflecting the general contraceptive method use patterns across the country.33 Similar to findings from this study, uptake of contraceptives is generally high (65%); however, uptake of efficient long-acting contraceptive methods has been shown to be relatively low, with majority of women relying on the male condom.15 34 A study conducted in Cape Town found that only 6% of 538 HIV-positive and HIV-negative women used long-acting and permanent contraceptive methods and this finding was mainly driven by poor knowledge of more efficient long-acting and permanent contraceptive methods. Choice of contraceptive method was primarily based on healthcare provider recommendations and convenience.33

While this study focused on women, the involvement of male partners and education around family planning and prevention of unplanned pregnancy also requires attention. Our results illustrate that women who were married or living with their male partners, those who had discussed family planning with their partners before conception and HIV-positive women who had disclosed their HIV status to their partners were less likely to have an unplanned pregnancy. Similar results from other studies have shown that male partners’ attitudes towards contraception impact strongly on pregnancy planning and contraceptive use among both HIV-positive and HIV-negative women in other settings.32

Finally, this study is one of the first to examine the validity of the LMUP in a low-income and middle-income country in Africa. The translated LMUP proved to be a reliable measure of pregnancy intention in this sample, similar to results obtained from another validation study conducted in Malawi.35 The LMUP is therefore recommended for use in research across similar settings in South Africa.

This study has some limitations. The cross-sectional design means that causal associations could not be examined and the significance of some of the predictors identified needs to be further explored using longitudinal studies. This study was specific to a single urban setting in South Africa and although it may be representative of existing knowledge of contraceptive methods, uptake and method preference within similar settings across the country,33 34 further research is needed in other countries. As women were asked to report on pregnancy intentions after pregnancy recognition and entering ANC, acceptance of the pregnancy during this time may have resulted in over-reporting of planned pregnancy. In contrast, women who terminated their pregnancy without presenting for ANC were not included in this study; therefore, the prevalence of unplanned pregnancy may have been underestimated. Finally, as contraceptive use was assessed only as any use of a contraceptive method in the 12 months prior to pregnancy recognition, our data are not robust to assess consistent contraceptive use during this time.

Despite some limitations, this study is notable and presents key differences between HIV-positive and HIV-negative women regarding pregnancy intentions and family planning practices. It is evident from our findings that HIV-positive women regardless of ART use require additional support to avoid unplanned pregnancy. While further research is required, young HIV-positive women and those with previous pregnancies may be particularly vulnerable. Moreover, our results suggest that HIV-negative women also require improved engagement in reproductive health services for HIV testing and prevention, as well as family planning services. There is an urgent need to empower all women in this context with appropriate and effective tools to prevent unplanned pregnancies. Focused and innovative interventions may be required to improve women’s understanding of various options for effective family planning.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all members of the research team who made data collection for this analysis possible, as well as all the women who consented to participate in the studies from which these data were obtained.

Footnotes

Contributors: EJA and LM conceptualised the study. TKP, SLR and AZ directed data collection. VI conducted the analysis, led data interpretation and drafted the manuscript, with critical inputs from KB, TKP, SLR, JAM, AZ, GP, EJA and LM. All authors read and approved the final manuscript to be published.

Funding: This work was supported by the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief through the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (grant 1R01HD074558). Additional funding comes from the Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation, the South African Medical Research Council, the Fogarty Foundation (NIH Fogarty International Center grant 5R25TW009340), and the Office of AIDS Research.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Detail has been removed from this case description/these case descriptions to ensure anonymity. The editors and reviewers have seen the detailed information available and are satisfied that the information backs up the case the authors are making.

Ethics approval: Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of Cape Town, Faculty of Health Sciences, and the Columbia University Medical Centre Institutional Review Board.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. UNAIDS. Global AIDS update 2016. Geneva: UNIADS, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2. UNAIDS. UNAIDS data 2017: UNAIDS, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shisana O, Rehle T, Simbayi L, et al. South African national HIV prevalence, incidence and behaviour survey, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. National Department of Health. The national antenatal sentinel HIV prevalence survey, South Africa, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bhardwaj S, Barron P, Pillay Y, et al. Elimination of mother-to-child transmission of HIV in South Africa: rapid scale-up using quality improvement. S Afr Med J 2014;104:239–43. 10.7196/SAMJ.7605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Joyce T, Kaestner R, Korenman S. The stability of pregnancy intentions and pregnancy-related maternal behaviors. Matern Child Health J 2000;4:171–8. 10.1023/A:1009571313297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mohllajee AP, Curtis KM, Morrow B, et al. Pregnancy intention and its relationship to birth and maternal outcomes. Obstet Gynecol 2007;109:678–86. 10.1097/01.AOG.0000255666.78427.c5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gipson JD, Koenig MA, Hindin MJ. The effects of unintended pregnancy on infant, child, and parental health: a review of the literature. Stud Fam Plann 2008;39:18–38. 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2008.00148.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kost K, Landry DJ, Darroch JE. Predicting maternal behaviors during pregnancy: does intention status matter? Fam Plann Perspect 1998;30:79–88. 10.2307/2991664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wado YD, Afework MF, Hindin MJ. Unintended pregnancies and the use of maternal health services in Southwestern Ethiopia. BMC Int Health Hum Rights 2013;13:36 10.1186/1472-698X-13-36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. World Health Organization. PMTCT strategic vision 2010-2015: preventing mother-to-child transmission of HIV to reach the UNGASS and Millennium Development Goals: World health Organization, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Reynolds HW, Janowitz B, Wilcher R, et al. Contraception to prevent HIV-positive births: current contribution and potential cost savings in PEPFAR countries. Sex Transm Infect 2008;84(Suppl 2):ii49–53. 10.1136/sti.2008.030049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Reynolds HW, Janowitz B, Homan R, et al. The value of contraception to prevent perinatal HIV transmission. Sex Transm Dis 2006;33:350–6. 10.1097/01.olq.0000194602.01058.e1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Credé S, Hoke T, Constant D, et al. Factors impacting knowledge and use of long acting and permanent contraceptive methods by postpartum HIV positive and negative women in Cape Town, South Africa: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2012;12:197 10.1186/1471-2458-12-197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kaida A, Laher F, Strathdee SA, et al. Contraceptive use and method preference among women in Soweto, South Africa: the influence of expanding access to HIV care and treatment services. PLoS One 2010;5:e13868 10.1371/journal.pone.0013868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. National Department of Health. South African demographic and health survey. South Africa, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sedgh G, Singh S, Hussain R. Intended and unintended pregnancies worldwide in 2012 and recent trends. Stud Fam Plann 2014;45:301–14. 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2014.00393.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kikuchi K, Wakasugi N, Poudel KC, et al. High rate of unintended pregnancies after knowing of HIV infection among HIV positive women under antiretroviral treatment in Kigali, Rwanda. Biosci Trends 2011;5:255–63. 10.5582/bst.2011.v5.6.255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mayondi GK, Wirth K, Morroni C, et al. Unintended pregnancy, contraceptive use, and childbearing desires among HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected women in Botswana: across-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2016;16:44 10.1186/s12889-015-2498-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. McCoy SI, Buzdugan R, Ralph LJ, et al. Unmet need for family planning, contraceptive failure, and unintended pregnancy among HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected women in Zimbabwe. PLoS One 2014;9:e105320 10.1371/journal.pone.0105320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Warren CE, Abuya T, Askew I. Family planning practices and pregnancy intentions among HIV-positive and HIV-negative postpartum women in Swaziland: a cross sectional survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2013;13:150 10.1186/1471-2393-13-150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Schwartz SR, Rees H, Mehta S, et al. High incidence of unplanned pregnancy after antiretroviral therapy initiation: findings from a prospective cohort study in South Africa. PLoS One 2012;7:e36039 10.1371/journal.pone.0036039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Loutfy M, Raboud J, Wong J, et al. High prevalence of unintended pregnancies in HIV-positive women of reproductive age in Ontario, Canada: a retrospective study. HIV Med 2012;13:107–17. 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2011.00946.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sutton MY, Patel R, Frazier EL. Unplanned pregnancies among HIV-infected women in care-United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2014;65:350–8. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Myer L, Morroni C, Rebe K. Prevalence and determinants of fertility intentions of HIV-infected women and men receiving antiretroviral therapy in South Africa. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2007;21:278–85. 10.1089/apc.2006.0108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Myer L, Phillips TK, Zerbe A, et al. Optimizing Antiretroviral Therapy (ART) for Maternal and Child Health (MCH): rationale and design of the MCH-ART Study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2016;72(Suppl 2):S189 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Myer L, Stein DJ, Grimsrud A, et al. Social determinants of psychological distress in a nationally-representative sample of South African adults. Soc Sci Med 2008;66:1828–40. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.01.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Barrett G, Smith SC, Wellings K. Conceptualisation, development, and evaluation of a measure of unplanned pregnancy. J Epidemiol Community Health 2004;58:426–33. 10.1136/jech.2003.014787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Raifman J, Chetty T, Tanser F, et al. Preventing unintended pregnancy and HIV transmission: effects of the HIV treatment cascade on contraceptive use and choice in rural KwaZulu-Natal. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2014;67(Suppl 4):S218–27. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Oulman E, Kim TH, Yunis K, et al. Prevalence and predictors of unintended pregnancy among women: an analysis of the Canadian Maternity Experiences Survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015;15:260 10.1186/s12884-015-0663-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cooper D, Harries J, Myer L, et al. "Life is still going on": reproductive intentions among HIV-positive women and men in South Africa. Soc Sci Med 2007;65:274–83. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.03.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wall KM, Haddad L, Vwalika B, et al. Unintended pregnancy among HIV positive couples receiving integrated HIV counseling, testing, and family planning services in Zambia. PLoS One 2013;8:e75353 10.1371/journal.pone.0075353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. National Department of Health. South Africa demographic and health survey 2016: key indicator report, statistics South Africa, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Chersich MF, Wabiri N, Risher K, et al. Contraception coverage and methods used among women in South Africa: a national household survey. S Afr Med J 2017;107:307–14. 10.7196/SAMJ.2017.v107i4.12141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hall J, Barrett G, Mbwana N, et al. Understanding pregnancy planning in a low-income country setting: validation of the London measure of unplanned pregnancy in Malawi. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2013;13:200 10.1186/1471-2393-13-200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.