Abstract

Objectives

Despite global efforts to increase facility-based delivery (FBD), 90% of women in rural Ethiopia deliver at home without a skilled birth attendant. Men have an important role in increasing FBD due to their decision-making power, but this is largely unexplored. This study aimed to determine the FBD care attributes preferred by women and men, and whether poverty or household decision-making are associated with choice to deliver in a facility.

Setting and participants

We conducted a cross-sectional discrete choice experiment in 109 randomly selected households in rural Ethiopia in September–October 2015. We interviewed women who were pregnant or who had a child <2 years old and their male partners.

Results

Both women and men preferred health facilities where medications and supplies were available (OR=3.08; 95% CI 2.03 to 4.67 and OR=2.68; 95% CI 1.79 to 4.02, respectively), a support person was allowed in the delivery room (OR=1.69; 95% CI 1.37 to 2.07 and OR=1.74; 95% CI 1.42 to 2.14, respectively) and delivery cost was low (OR=1.15 95% CI 1.12 to 1.18 and OR=1.14; 95% CI 1.11 to 1.17, respectively). Women valued free ambulance service (OR=1.37; 95% CI 1.09 to 1.70), while men favoured nearby facilities (OR=1.09; 95% CI 1.06 to 1.13) with friendly providers (OR=1.30; 95% CI 1.03 to 1.64). Provider preferences were complex. Neither women nor men preferred female doctors to health extension workers (HEW) (OR=0.92; 95% CI 0.59 to 1.42 and OR=0.74; 95% CI 0.47 to 1.14, respectively), male doctors to HEW (OR=1.33; 95% CI 0.89 to 1.99 and OR=0.75; 95% CI 0.50 to 1.12, respectively) or female over male nurses (OR=0.68; 95% CI 0.94 to 1.71 and OR=1.03; 95% CI 0.77 to 2.94, respectively). While both women and men preferred male nurses to HEW (OR=1.86; 95% CI 1.23 to 2.80 and OR=1.95; 95% CI 1.30 to 2.95, respectively), men (OR=1.89; 95% CI 1.29 to 2.78), but not women (OR=1.47; 95% CI 1.00 to 2.13) preferred HEW to female nurses. Both women and men preferred female doctors to male nurses (OR=1.71; 95% CI 1.27 to 2.29 and OR=1.44; 95% CI 1.07 to 1.92, respectively), male doctors to female nurses (OR=1.95; 95% CI 1.44 to 2.62 and OR=1.41; 95% CI 1.05 to 1.90, respectively) and male doctors to male nurses (OR=2.47; 95% CI 1.84 to 3.32 and OR=1.46; 95% CI 1.09 to 1.95, respectively), while only women preferred male doctors to female doctors (OR=1.45; 95% CI 1.09 to 1.93 and OR=1.01; 95% CI 0.76 to 1.35, respectively) and only men preferred female nurses to female doctors (OR=1.34; 95% CI 0.98 to 1.84 and OR=1.39; 95% CI 1.02 to 1.89, respectively). Men were disproportionately involved in making household decisions (X2 (1, n=216)=72.18, p<0.001), including decisions to seek healthcare (X2 (1, n=216)=55.39, p<0.001), yet men were often unaware of their partners’ prenatal care attendance (X2 (1, n=215)=82.59, p<0.001).

Conclusion

Women’s and men’s preferences may influence delivery service choices. Considering these choices is one way the Ethiopian government and health facilities may encourage FBD in rural areas.

Keywords: maternal Health, ethiopia, delivery services, discrete choice experiment

Strengths and limitations of this study.

First known discrete choice experiment to test preferences of both women and men around choice of facility-based delivery services.

Acknowledges role men play in making delivery decisions for their families.

Tests preferences predicted by the Three Delays model and based on literature to influence use of delivery services.

Limited generalisability due to difference in wealth between study sample and general population.

Background/rationale

Maternal mortality ratio in Ethiopia decreased from 871 deaths/100 000 live births in 2000 to 676/100 000 in 2011,1 but still remains above the 75% Millennium Development Goal (MDG) target reduction (218).2 Neonatal mortality rate has remained relatively unchanged since 2005 (39 deaths/1000 live births)1 despite Ethiopia having achieved the MDG for infant mortality in 2013.2 More than 90% of rural women deliver at home, a known barrier to reducing maternal and neonatal mortality.1

Recommendations for reducing maternal and neonatal mortality focus on skilled birth attendants (SBA) conducting delivery and referral care availability for emergencies.3 While the SBA definition does not preclude home delivery,4 conditions in many low/middle-income countries make skilled birth attendance synonymous with facility-based delivery (FBD). If women are not delivering at facilities, they do not have access to emergency interventions.5

Despite government efforts to improve FBD by increasing health facility numbers and training health staff in emergency obstetric and neonatal care services provision,6 home delivery remains a strong tradition in Ethiopia.7 8 In a setting where home deliveries were also common, community members and providers identified FBD changes that would make FBD services more culturally acceptable and convenient to families. Changes that were both safe and acceptable to patients were instituted. Between 1999 and 2007, FBD increased from 6% to 83% in targeted rural communities.9 Kenya’s programme to increase dialogue between communities and health services increased FBD in the rural community by 6.1%.10 Community mobilisation increased FBD by 30% in Burkina Faso.11 No studies were found that tested community-directed facility-based interventions to improve FBD in Ethiopia. An increased understanding of factors underlying delivery place choice may help Ethiopian health facilities to better respond to families’ preferences.

The expanded Three Delays model12 describes delays in receiving emergency and preventative FBD services: (1) deciding to seek care, (2) reaching the health facility and (3) receiving appropriate treatment. The decision to seek care may be influenced by sociocultural factors, perceived benefits and needs, perceived economic and physical accessibility, and perceived quality of care. A literature review including 54 studies examined factors associated with delivery location in Ethiopia’s unique cultural context. Changeable FBD factors included cultural barriers, perceived benefits and barriers, economic accessibility, and physical accessibility. Cultural barriers to FBD identified in qualitative studies were examinations by male providers,13 14 facility rules limiting support from family and friends during delivery,8 14–22 and medical culture that allows mistreatment of pregnant women by providers.13–15 18 20 Conversely, facilities offering delivery by higher level providers18 21–23 and which were consistently stocked with medications and supplies were appreciated.18 23 Quantitative measures of cultural factors include women’s autonomy and involvement in deciding where to deliver. Women’s autonomy was not generally found to be associated with FBD.24–28 However, women involved in deciding where to deliver were more likely to have FBDs.15 17 29–33

Perceived benefits and need for FBD may be influenced by access to mass media, antenatal care (ANC) use and previous FBD. FBD may be more common among families who own radios and/or televisions,17 34 35 but more frequently no association was found.29 33–38 ANC use, which may both increase knowledge of perceived benefits and need for FBD, and increase comfort with facility staff, was frequently,15 27 31 33 38–47 but not always,25 29 48–50 associated with FBD. Previous experience with FBD varied in its association with FBD from positive40 49 to negative43 to no association.29

Although the Three Delays model shows that perceived, rather than actual, economic accessibility predicts care-seeking behaviour, most Ethiopian studies measure economic accessibility as mother’s occupation,17 24–26 33 36 37 42 44 45 51 52 husband’s occupation,31 33 35 37 45 48 51 52 monthly income17 25 29 31 36 40 45 53 or wealth quintile.24 30 32 34 38 39 46 47 52

As with economic accessibility, physical accessibility to health facilities is most often measured as actual, rather than perceived, accessibility. Women living in urban areas are more likely to have FBDs.15 24 26–31 34–39 43–45 48–50 52 53 Less time to reach facilities30 43 49 52 and closer distance17 34 36 were associated with FBD, but associations between time to facility36 40 48 and distance36 37 43 52 54 with FBD were not always significant. Transportation availability increased FBD likelihood.36

Several weaknesses in research methodology limit interpretation of Ethiopian studies. First, research participants were almost exclusively women, yet male partners often make household decisions55–57 including delivery location.58 Second, cultural practices identified in qualitative studies as barriers to FBD have not been included in quantitative studies. Third, descriptive studies that base data collection on the Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey (EDHS) limit new knowledge generation by asking the same questions in the same way. A discrete choice experiment (DCE) conducted by Kruk et al 59 in rural Ethiopia overcame this weakness. Women who had delivered in the last 5 years were asked to choose between two hypothetical facilities with varying distance, provider type, provider attitude, drug and medical equipment availability, transportation availability and cost attributes, thus identifying women’s priorities in the context of multiple factors.

We collected data from both women and men and used DCE methodology to elicit preferences for delivery service attributes, specifically, allowing support persons in the delivery room, provider gender, distance, provider type, provider attitude, drug and medical equipment availability, free transportation availability and delivery cost. Our study aims were to determine: (a) the FBD care attributes preferred by women and men, (b) whether gender differences exist in attribute preferences and (c) whether poverty levels or household decision-making involvement are associated with facility choice.

Methods

Research design

This cross-sectional DCE had three parts: household survey, individual surveys of men and women, and DCE task set. Questions in household and individual surveys were drawn from the EDHS.

DCE study design

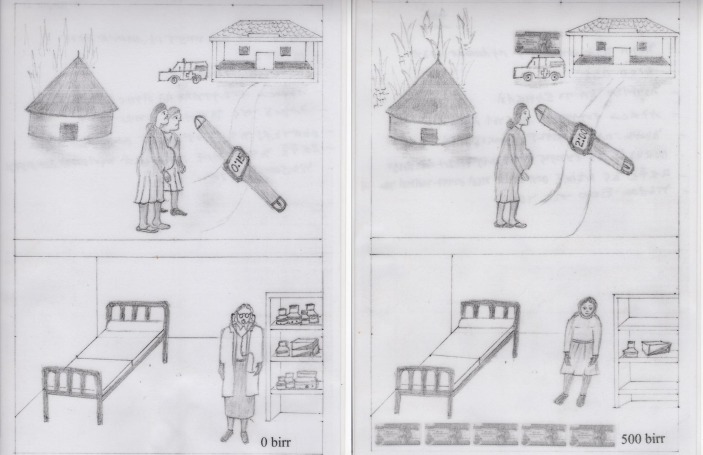

Respondents were shown pictures of two facilities (figure 1) and asked to imagine they were deciding where they would deliver their next baby. They were asked to choose between facility A, facility B or neither facility. Facility A and facility B were described using a script.

Figure 1.

Sample task set for discrete choice experiment.

Table 1 lists attributes and levels included in the experimental design and were selected to produce a reasonable number of scenarios to test with respondents.60–62 Given that all attributes had either two or five levels, 10 tasks were required for attribute level balance. Pilot testing with local women and men indicated 10 tasks did not cause respondent fatigue.

Table 1.

Attributes and levels for discrete choice experiment

| Attribute | Levels |

| Distance to health facility | 30 min 1 hour 1½ hours 2 hours 3 hours |

| Type of provider* | Female doctor Male doctor Female nurse Male nurse Female health extension worker |

| Provider attitude | Provider smiles, is kind and respectful, speaks softly Provider does not smile, uses a harsh tone, harsh language |

| Availability of medication and supplies | Drugs and medical equipment always available Drugs and medical equipment not always available |

| Availability of free transport | Free ambulance available Free ambulance not available |

| Support persons | Family and friends allowed in delivery room Family and friends not allowed in delivery room |

| Cost (cost of user charges, labour-related supplies and non-ambulance transportation) | No cost 50 Ethiopian birr† 100 Ethiopian birr 200 Ethiopian birr 300 Ethiopian birr |

*Nurse was used to indicate both nurses and midwives on the advice of Ethiopian staff as patients generally did not understand the difference between nurses and midwives.

†Approximately 20 birr/US$1.

Quality of care was represented by medications and supplies’ availability, provider attitude and provider type. Presence of support persons in the delivery room and provider gender tested cultural preferences. Perceived accessibility was represented by cost, distance to facility and free ambulance availability.

Design decisions

A d-efficient design (d-error=0.3) that allows for smaller sample size, while still estimating attributes at a statistically significant level,62 was produced based on prior probabilities established through a review of the literature63 using nGene software.64

Sample size

A sample size of mean=36 820, median=314, ranging from minimum=8 to maximum=5 162 097 was calculated by nGene to detect statistically significant differences between women and men. Examining the equation for sample size provides an explanation for the wide range:

Nk=(Tk2×sek2)/betak

where Nk is the sample size, Tk2 is the t-ratio required for significance, sek2 is the SE for the prior parameter and betak is the prior parameter. Therefore, as beta approaches zero, the sample size needed to detect statistical difference increases.

Several of the priors range from −1 to 1, reflecting the degree of uncertainty in the priors, which in turn results in a large sample size requirement (J Rose, personal communication, 18 August 2015).65

Given the logistical impossibility of collecting a large sample for this pilot study, J Rose (personal communication, 20 May 2015) recommended 100 respondents for each group (women and men) based on expected improved statistical properties of basing the design on prior parameters. Assuming a 20% non-response rate, 120 households were selected, representing 240 respondents.

Subjects and setting

The target population was women and their male partners in two rural kebeles defined by the most recent census (2007)66 in Sidama zone, Southern Nations, Nationalities and People’s region, Ethiopia. Kebeles are the smallest administrative unit in Ethiopia. Inclusion criteria were women and men who were expecting a child or had a child less than 2 years old. Eligible participants were excluded if unable to answer questions due to mental or physical disabilities. Informed consent and household interviews were conducted in participants’ homes in October 2015.

Sample plan

Health extension workers (HEW) from two kebeles listed eligible households using clinic and home visit records. Households were randomly selected by assigning each household a random number using the Excel random number generator and then sorting numerically.

Informed consent procedures

Informed oral consent was obtained before the survey. Common River, a local non-governmental organisation, facilitated logistical arrangements with community participants.

Validity and reliability

Validity

Questions from the EDHS were used for this study, thus building on EDHS’ strong validity.67–76 Demographic, health, education and living standard variables were collected. Additional EDHS questions were used to assess participation in decision-making, mass media exposure, danger signs knowledge, ANC use and delivery history.

Attributes and levels for this DCE study were based on review of Ethiopian literature and the Three Delays model77 and were refined during informant interviews and survey pilot testing to discern which attributes and levels were valid in this setting.61 Pictures drawn by a local artist were used to ensure understanding in this low-literacy population and were pretested with a local women’s group and male staff at a local non-governmental organization.

Reliability

Experienced data collectors, fluent in both Amharic and Sidaminya (local languages) were trained using a written protocol to ask questions in a standardised manner. Study materials were translated into Amharic and Sidaminya and back-translated into English by local and professional translators. Questionnaires were pretested for clarity to ensure interviewers and participants easily understood questions. In addition to pretesting with male and female community members that took place during the translation and testing of the DCE pictures, the entire instrument was pretested during a day of field-testing. Pretesting was conducted at households that had not been selected as part of the sample. Approximately 12 men and 12 women participated in pretesting. Questionnaires were reviewed daily for completeness; when errors were found, interviewers were asked for clarification.

To reduce socially desirable answers and response bias, interviewer and respondent genders were matched, interviewers were trained to be non-judgemental, privacy was ensured and sensitive questions were asked later in the interview after respondent’s trust had been gained. To reduce non-response bias, households were revisited up to three times to contact eligible participants.

Multidimensional Poverty Index

The Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) combines poverty aspects not captured by income-based poverty measures into one number.78 The MPI combines deprivations at household level in education, health and living standard.79 The deprivation score is calculated by summing 10 component weighted scores in three indicator areas80 (table 2).

Table 2.

The Multidimensional Poverty Index deprivation score indicators

| Definition | Weights (%) |

| Health | |

| A household member is malnourished | 16.7 |

| A child has died in the last 5 years | 16.7 |

| Education | |

| No one in the household has completed at least 6 years of school | 16.7 |

| A school-age child (7–15) is not enrolled in school | 16.7 |

| Living standard | |

| No electricity | 5.6 |

| No access to clean drinking water or source of clean drinking water >30 min walk | 5.6 |

| Household lacks improved sanitation, or shares with other households | 5.6 |

| Dirty cooking fuel is used (dung, wood or charcoal) | 5.6 |

| Household has a dirt, sand or dung floor | 5.6 |

| Household does not own a radio, television or telephone, and does not own a means of transportation (bike, motorbike, car, truck, animal cart, motorboat) or a means of livelihood (refrigerator, arable land, livestock) | 5.6 |

Health, education and living standard indicators were collected to compare the sample population to the national MPI. Malnutrition data could not be collected due to time and cost restraints. In addition, sanitation questions were discarded due to misinterpretation. Therefore, the sample MPI was not directly comparable with the reported national MPI. Instead, individual indicators in the sample were compared with EDHS data. The sample MPI served as a poverty indicator in the analysis.

Household Decision-Making score

During the EDHS, women are asked about who makes decisions around obtaining healthcare for themselves, large household purchases and visits to relatives. Women who make decisions on all three indicators, either solely or jointly with their husbands, are considered to have the highest autonomy. Men are asked about their participation in large household purchases and obtaining healthcare for themselves.1 In this study, both women and men were asked about their involvement in decisions regarding obtaining healthcare for themselves, large household purchases and visits to relatives.

Data management and analysis

Study household characteristics were calculated and compared with the 2011 EDHS of rural households using χ2 and t-tests to determine statistically significant differences. Similar analysis was conducted to describe and compare characteristics and reported pregnancy and delivery care practices of female and male study participants.

We used multilevel mixed-effects logistic regression with QR decomposition. QR decomposition improves convergence when random-effects variance is small.81 Unlike other models, which assume independence, multilevel models take dependency of multiple observations from single respondents into account.62 Level 1 included choices made by each respondent, level 2 included respondent’s gender and level 3 included household characteristics.

The analysis was conducted in four parts, which are described in more detail below. First, separate multivariate analyses of women and men’s data were conducted to determine their preferences. Second, the data were combined, and gender was introduced as a level-2 variable to determine whether a statistical difference existed between women and men’s preferences. Third, a level-2 analysis of various decision-making measures were tested to determine their effect on facility choice. Finally, the effect of household poverty on preferences was tested in a level-3 analysis.

Women and men’s responses were analysed separately to determine the utility of specific level-1 attributes for each group that significantly contributed to facility choice. Adjusted ORs were calculated to provide a more intuitive presentation of strength and direction of utility coefficients (eβ). Bonferroni method was used to control alpha for multiple comparisons.

A multilevel model was constructed by adding individual and random intercept terms. Level-2 interaction terms, combining attributes with gender, were introduced into the model one by one to test whether women and men differed significantly on preferences for facility characteristics. Predictor interactions with involvement in household decision-making (level 2) were also tested.

Household poverty level (level 3), main effect on facility choice, was tested by creating a poverty variable. First, household deprivation per cent was calculated using MPI deprivation indicators using reweighted variables to reflect use of fewer variables. Next, a dichotomous variable, poverty, was created to divide households into those with per cent deprivation ≥33.3%, the definition for multidimensional poverty and those who were not multidimensionally poor. In addition to adding poverty to the model to test the effect on facility choice, the interaction between poverty and gender was also tested to determine whether multidimensional poverty effected women and men differently.

Akaike’s information criterion (AIC) was estimated and likelihood-ratio (LR) tests were conducted to test improvement in model fit. A decrease in AIC with a significant LR test indicates improvement in model fit.

Data were double-entered in REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture), a secure web-based programme for managing surveys and databases82 and analysed using Stata V.14.

Results

Participant eligibility

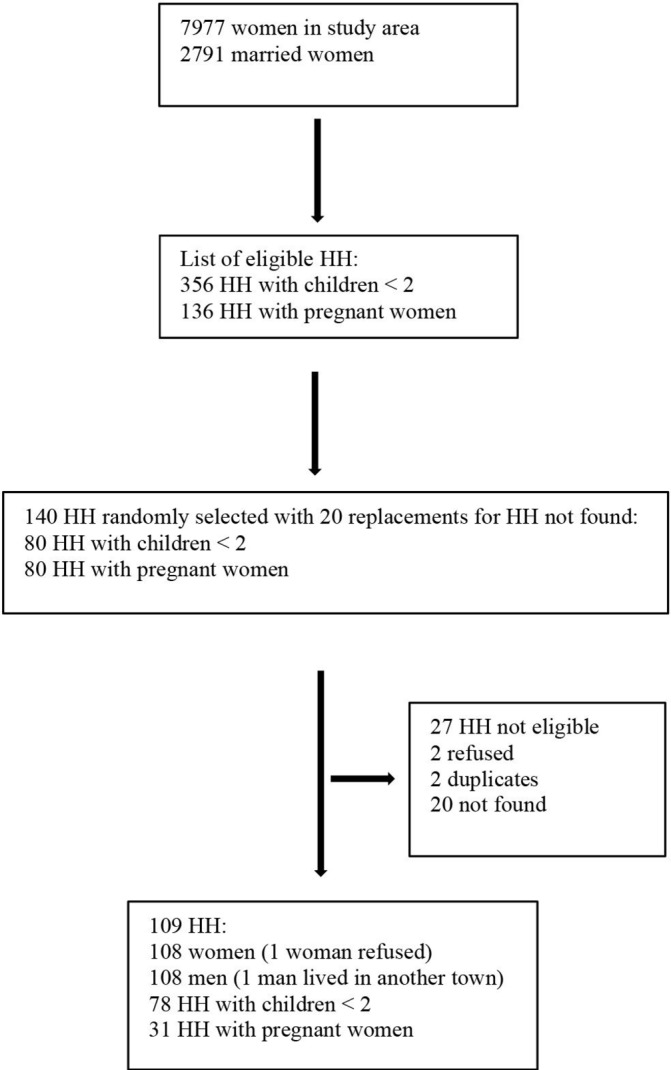

Households with children <2 years old (n=356) and households with pregnant women (n=136) were eligible to participate (figure 2). For 20 households not located due to incomplete addresses, the next randomly selected household was approached. Participation rate for locatable, eligible households was 98%. Household and individual surveys took approximately 5 min, and the DCE portion took approximately 10 min to complete.

Figure 2.

Study flow diagram. HH, households.

Study participants’ characteristics

Household characteristics

Study sample household characteristics were compared with household characteristics from the EDHS (table 3). Study sample participants generally had better living conditions and more access to radios and mobile phones than those in the EDHS sample. However, a significantly greater per cent of study sample households lacked land and livestock.

Table 3.

Characteristics of households in Sidama Zone, SNNPR sample compared with EDHS rural subsample

| Variable | Study sample*(n=109) | EDHS 2011 (n=11 590) | P values |

| Household size, mean (SD) | 5.4 (2.1) | 4.9 | <0.05 |

| Living conditions | |||

| Use solid fuel for cooking† | 109 (100) | 11 474 (99.0) | ns |

| Dirt or dung floor | 81 (74.3) | 11 068 (95.5) | <0.001 |

| Non-improved drinking water‡ | 21 (19.27) | 6734 (58.1) | <0.001 |

| Walk ≥30 min to drinking water | 61 (56.0) | 7232 (62.4) | <0.001 |

| No electricity | 78 (71.6) | 11 034 (95.2) | <0.001 |

| Access to information | |||

| No radio | 50 (45.9) | 7684 (66.3) | <0.001 |

| No mobile phone | 35 (32.1) | 10 106 (87.2) | <0.001 |

| No landline | 109 (100) | 11 567 (99.8) | ns |

| No television | 107 (98.2) | 11 463 (98.9) | ns |

| Access to transportation | |||

| No bicycle | 108 (99.1) | 11 428 (98.6) | ns |

| No motorcycle | 107 (98.2) | 11 578 (99.9) | <0.001 |

| No vehicle | 109 (100) | 11 578 (99.9) | ns |

| No animal cart | 108 (99.1) | 11 463 (98.9) | ns |

| Means of livelihood | |||

| No refrigerator | 109 (100) | 11 520 (99.4) | ns |

| No agricultural land | 25 (22.9) | 1414 (12.2) | <0.001 |

| No livestock | 40 (36.7) | 1217 (10.5) | <0.001 |

Results are presented as n (%) unless otherwise specified.

*Study sample had no missing data except Dirt or dung floor: 10 missing; owns land: 25 don’t know.

†Includes wood, charcoal, straw/shrubs/grass, agricultural crops and animal dung.

‡Includes piped into dwelling, piped to yard/plot, public tap/standpipe, borehole, protected well, protected spring, rainwater, bottled water.

EDHS, Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey; ns, not significant; SNNPR, Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples' Region.

Female and male participants’ characteristics

Ninety-seven per cent of women and 99% of men were from Sidama. All women and 96% of men were Protestant. Women were on average 7 years younger and had 1 year less education than their husbands had. Men had two to three times more exposure to mass media and participated more in household decisions compared with women. Men were more likely to believe their wife had received prenatal care during their pregnancy (89.8%) than women reported having done so (29.0%) (table 4).

Table 4.

Characteristics of female and male study participants in Sidama Zone, SNNPR, Ethiopia

| Characteristic | Study sample* | ||

| Women (n=108) | Men (n=108) | P values | |

| Age, mean (SD) | 24.7 (4.6) | 32.1 (8.5) | t=−7.85 (211), p<0.001 |

| Per cent who never attended school | 14 (13.0) | 2 (1.9) | X 2 (1, n=215)=9.72, p<0.05 |

| Years of education, mean (SD) | 5.5 (3.5) (n=93) |

6.8 (3.3) (n=106) |

t=−2.75(197), p<0.05 |

| Mass media exposure | |||

| Never reads paper | 93 (86.1) | 50 (46.3) | X 2 (1, n=216)=38.26, p<0.001 |

| Never listens to radio | 81 (75.0) | 28 (25.9) | X 2 (1, n=216)=52.02, p<0.001 |

| Never watches television | 99 (91.7) | 36 (33.3) | X 2 (1, n=216)=78.40, p<0.001 |

| No mass media exposure at least once/week | 72 (66.7) | 57 (52.8) | X 2 (1, n=216)=4.33, p<0.05 |

| Involved in decisions about: | |||

| Seeking healthcare for self† | 48 (44.4) | 99 (91.7) | X 2 (1, n=216)=55.39, p<0.001 |

| Respondent alone | 4 (3.7) | 23 (21.3) | |

| Partner or someone else | 60 (55.6) | 9 (8.3) | |

| Jointly with spouse | 44 (40.7) | 76 (70.4) | |

| Major household purchases† | 66 (61.1) | 106 (98.1) | X 2 (1, n=216)=45.67, p<0.001 |

| Respondent alone | 7 (6.5) | 14 (13.0) | |

| Partner or someone else | 42 (38.9) | 2 (1.8) | |

| Jointly with spouse | 59 (54.6) | 92 (85.2) | |

| Visiting friends and family† | 84 (77.8) | 103 (95.4) | X 2 (1, n=216)=14.38, p<0.001 |

| Respondent alone | 26 (24.1) | 22 (20.4) | |

| Partner or someone else | 24 (22.2) | 5 (4.7) | |

| Jointly with spouse | 58 (53.7) | 81 (75.0) | |

| Full decision-making capacity‡ | 35 (32.4) | 96 (88.9) | X 2 (1, n=216)=72.18, p<0.001 |

| Participated in none of the three decisions | 18 (16.7) | 1 (0.9) | X 2 (1, n=216)=16.68, p<0.001 |

| Pregnancy and delivery care characteristics§ | |||

| Prenatal care during last or current pregnancy | 31 (29.0) | 97 (89.8) | X 2 (1, n=215)=82.59, p<0.001 |

| Place of last delivery | |||

| Home¶ | 51 (65.4) | 46 (59.7) | X 2 (1, n=155)=0.53, p=ns |

| Health facility | 27 (34.6) | 31 (40.3) | X 2 (1, n=155)=0.53, p=ns |

| Delivered by a skilled birth attendant | 25 (23.2) | 30 (27.8) | X 2 (1, n=216)=0.61, p=ns |

Data are n (%) unless otherwise specified.

*Study sample had no missing data except—Women: Age 2; Years of education 15; Prenatal 1; Men: Age 1; Years of education 2.

†Alone or jointly with spouse.

‡Defined as participating in making decisions about healthcare, major household purchases and visits to family or relatives alone or jointly with spouse.

§Women and men were asked these questions separately.

¶Home includes participant’s home or another home.

ns, not significant; SNNPR, Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples' Region.

DCE results

Women’s preferences

Women’s odds of choosing to deliver at a facility were 3.08 (2.03 to 4.67) times greater if medications and supplies were always available, 1.69 (1.37 to 2.07) times greater if support persons were allowed in delivery room, 1.37 (1.09 to 1.70) times greater if a free ambulance was available and 1.15 (1.12 to 1.18) times greater for every 50-birr (US $2.50) reduction in cost (table 5).

Table 5.

Results from mixed-effects logistic regression model for utility of attributes of health facilities for delivery, reported for 108 women* from Sidama zone, SNNPR, Ethiopia

| Variable | OR | P values | 95% CI |

| Medications and supplies | |||

| Always available | 3.08 | 0.000 | 2.03 to 4.67 |

| Support person | |||

| Allowed in delivery room | 1.69 | 0.000 | 1.37 to 2.07 |

| Ambulance | |||

| Free | 1.37 | 0.006 | 1.09 to 1.70 |

| Cost (per 50-birr decrease) | 1.15 | 0.000 | 1.12 to 1.18 |

| Provider | |||

| Female doctor versus HEW |

0.92 | 0.702 | 0.59 to 1.42 |

| Male doctor versus HEW |

1.33 | 0.169 | 0.89 to 1.99 |

| Female nurse versus HEW |

0.68 | 0.050 | 0.47 to 1.00 |

| Male nurse versus HEW |

0.54 | 0.003 | 0.36 to 0.81 |

| Female doctor versus male doctor |

0.69 | 0.011 | 0.52 to 0.92 |

| Female doctor versus female nurse |

1.34 | 0.064 | 0.98 to 1.84 |

| Female doctor versus male nurse |

1.71 | 0.000 | 1.27 to 2.29 |

| Male doctor versus female nurse |

1.95 | 0.000 | 1.44 to 2.62 |

| Male doctor versus male nurse |

2.47 | 0.000 | 1.84 to 3.32 |

| Female nurse versus male nurse |

0.68 | 0.120 | 0.94 to 1.71 |

| Attitude | |||

| Smiles, listens | 1.24 | 0.075 | 0.98 to 1.56 |

| Distance (per 15 min decrease in walking time) |

0.99 | 0.383 | 0.86 to 1.05 |

AIC decreased from 2960 (null) to 2762 (level 1). Likelihood ratio χ2(10)=218.30, p<0.0001. Bolded values are significant at the p<0.05 level.

*Twenty-one missing responses and 99 neither responses out of 3240 options.

AIC, Akaike’s information criterion; HEW, health extension worker; SNNPR, Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples' Region.

Provider type was significant using the Wald test (p<0.0001) followed by Bonferroni-protected multiple comparisons. Women were 1.86 (1.23 to 2.80) times more likely to prefer delivery by HEW than male nurses, 1.45 (1.09 to 1.93) times more likely to prefer male doctors to female doctors, 1.71 (1.27 to 2.29) times more likely to prefer female doctors to male nurses, 1.95 (1.44 to 2.62) times more likely to prefer male doctors to female nurses and 2.47 (1.84 to 3.32) times more likely to prefer male doctors to male nurses.

Men’s preferences

For men (table 6), odds of choosing a facility were 2.68 (1.79 to 4.02) times greater when medications and supplies are always available, 1.74 (1.42 to 2.14) times greater when a support person is allowed in delivery room, 1.30 (1.03 to 1.64) times greater when provider smiles and listens well, 1.09 (1.06 to 1.13) times greater for each 15 min reduction in walking distance and 1.14 (1.11 to 1.17) times greater for every 50-birr reduction in cost.

Table 6.

Results from mixed-effects logistic regression model for utility of attributes of health facilities for delivery, reported for 108 men* from Sidama zone, SNNPR, Ethiopia

| Variable | OR | P values | 95% CI |

| Medication and supplies | |||

| Always available | 2.68 | 0.000 | 1.79 to 4.02 |

| Support person | |||

| Allowed in delivery room | 1.74 | 0.000 | 1.42 to 2.14 |

| Attitude | |||

| Smiles, listens | 1.30 | 0.030 | 1.03 to 1.64 |

| Distance (per 15 min decrease in walking time) |

1.09 | 0.000 | 1.06 to 1.13 |

| Cost (per 50-birr decrease) |

1.14 | 0.000 | 1.11 to 1.17 |

| Provider | |||

| Female doctor versus HEW |

0.74 | 0.169 | 0.47 to 1.14 |

| Male doctor versus HEW |

0.75 | 0.155 | 0.50 to 1.12 |

| Female nurse versus HEW |

0.53 | 0.001 | 0.36 to 0.78 |

| Male nurse versus HEW |

0.51 | 0.001 | 0.34 to 0.77 |

| Female doctor versus male doctor |

0.99 | 0.929 | 0.74 to 1.31 |

| Female doctor versus female nurse |

1.39 | 0.035 | 1.02 to 1.89 |

| Female doctor versus male nurse |

1.44 | 0.014 | 1.07 to 1.92 |

| Male doctor versus female nurse |

1.41 | 0.022 | 1.05 to 1.90 |

| Male doctor versus male nurse |

1.46 | 0.012 | 1.09 to 1.95 |

| Female nurse versus male nurse |

1.03 | 0.832 | 0.77 to 2.94 |

| Ambulance | |||

| Free | 0.95 | 0.679 | 0.76 to 1.19 |

AIC decreased from 2960 (null) to 2781 (level 1). Likelihood ratio χ2(10)=234.49, p<0.0001. Bolded values are significant at the p<0.05 level.

*No missing responses and 37 neither responses out of 3240 options.

AIC, Akaike’s information criterion; HEW, health extension worker; SNNPR, Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples' Region.

Provider type was significant overall using the Bonferroni Omnibus test (p<0.0001). Men were 1.89 (1.29 to 2.78) times more likely to prefer their wives be delivered by HEW than female nurses, 1.95 (1.30 to 2.95) times as likely to prefer delivery by HEW to male nurses, 1.39 (1.02 to 1.89) times as likely to prefer female doctors to female nurses, 1.44 (1.07 to 1.92) times as likely to prefer female doctors to male nurses, 1.41 (1.05 to 1.90) times as likely to prefer male doctors to female nurses and 1.46 (1.09 to 1.95) times as likely to prefer male doctors to male nurses.

Significant differences between predictors of women and men’s choices

Only distance, provider type and ambulance cost were significantly different between women and men. Women’s odds of selecting a facility increased 1.08 times for every 15 min increase in distance compared with men (1.03 to 1.14). Women were 1.70 (1.15 to 2.52) times more likely than men to prefer male doctors to male nurses and 1.36 (1.05 to 1.75) times more likely to prefer a facility with free ambulance service. AIC decreased from the level-1 model (5551) to a level-2 model adding gender at level 2 (5536), and the LR was significant (X2(10)=28.54, p=0.0002) indicating improved model fit with the addition of significant cross-level interactions.

Decision-making

While table 4 illustrated significant differences between women and men’s involvement in decision-making, decision-making involvement did not significantly influence facility choice, whether measured as none versus any (p=0.496); involved in healthcare decisions for self versus not involved (p=0.653); involved in healthcare decisions for self versus not involved, women versus men (p=0.189); number of decisions involved in (continuous) (p=0.930) or number of decisions involved in (categorical) (p=0.133).

Poverty and facility choice

Facility choice did not differ between multidimensionally poor and not multidimensionally poor households (p=0.170), but facility choice was associated weakly with per cent household deprivation (p=0.055). In addition, facility choice did not differ between women and men based on household deprivation (p=0.672).

Discussion

DCE preferences

In this study, both women and men placed the highest value on health facilities that always had medications and supplies available and allowed support persons into the delivery room. Women’s facility choice was also influenced by free ambulance availability and low cost, while men were more likely to choose nearer, less expensive delivery services with friendly providers.

In contrast, in a DCE in rural Ethiopia, Kruk et al 59 found women preferred high-quality delivery services such as available drugs and medical equipment, doctors or nurses rather than HEW, and friendly providers, with lower value placed on accessibility indicators when selecting facilities. Neither support person presence nor provider gender was included in their study.

In our study, preferences for provider type were complex. In order to have a reasonable number of scenarios, provider type and gender were linked in the study design, making provider preferences difficult to interpret. Women generally preferred doctors to nurses, although no significant difference in preference was found between delivery by female doctors or female nurses. Men preferred facilities with doctors to nurses regardless of gender. Nurse’s gender did not affect women’s facility preference, but male doctors were selected over female doctors. While preference for more highly skilled providers noted by Kruk et al 59 generally held between doctors and nurses; HEW were either preferred or chosen equally to doctors and nurses.

Interpreting findings within the Three Delays model: implications for services and research

Perceived quality of care

In our study, reliable medications and supplies’ availability was the strongest facility choice indicator for both women and men. This important element of the Three Delays model’s perceived quality of care12 83 has been reported by other researchers.8 13 23 59 Government and facility administrators should prioritise supply chain management when making budget allocations. A study comparing actual and perceived stocks of medications and supplies’ impact on FBD rates and cost analysis of lives saved through improving supply chains would add further information on this intervention’s effectiveness.

Provider attitude was a significant facility choice predictor for men, but not women. However, no significant difference was found between women and men’s facility choice based on provider attitude. Qualitative researchers have reported mistreatment by staff, ranging from yelling to physical abuse, made women distrustful of health facilities.13–15 18 21 Roro et al 20 reported this was true for men also. Lack of significance of provider attitude for women in this study may result from considering this aspect of care in the context of other variables, which were more important. It may also be that women in this area have had little experience with unfriendly providers, so they are not concerned with this attribute.

Both women and men valued doctors more than nurses, but preferred or were neutral on selecting facilities with HEW compared with more skilled providers. While appreciation of skilled providers is not uncommon,15 16 18 21 22 36 HEW’s ability to perform safe deliveries has been questioned.8 14 20 21 Preference for HEW may reflect the desire to be delivered by someone they know, or greater flexibility by HEW in accommodating cultural birth practices84 such as allowing support persons to be present in the delivery room. Both women and men may be more comfortable with HEW who are local women,84 85 and provide antenatal and postnatal services,85 trusting them to refer mothers in emergencies.85 Our findings suggest inherent trust in providers, who understand the cultural context and needs, is more important than procedural skill and knowledge.

The apparent preference for HEW and doctors over nurses is concerning. Nurses offer the lowest cost solution to providing skilled care in most low/middle-income countries. Research is needed to better understand why nurses were least preferred and how to address this issue, as it could have implications for women’s health outcomes and workforce training.

Cultural factors

Cultural preference for being surrounded by family and friends during delivery8 14–19 21 22 was voiced by both women and men. Excluding support persons from the delivery room is incompatible with cultural norms and is likely to decrease FBD uptake.86 A cluster randomised controlled trial comparing facilities implementing family-centred delivery policies with those that are not could test this finding.

Preference for male over female providers contradicts reports in qualitative literature.8 14 15 29 One explanation for this difference may lie in the study design. When asked directly about provider gender preferences, respondents may say they are ashamed to be delivered by a man.13 14 29 However, when given more complex scenarios, underlying biases, such as sexism, may have greater influence on respondent choices, leading them to choose male providers as being more qualified.

Perceived accessibility

Both women and men preferred lower cost services. However, distance and free ambulance availability had mixed influences on facility choice with women preferring facilities with free ambulance service, while men were more influenced by distance. Other Ethiopian research has shown either no effect37 40 41 48 54 or increases in FBD when facilities are closer.17 27 30 36 43 49 52 Women may prioritise free ambulance service due to greater concern for their own comfort as other free transportation, such as riding in animal carts or being carried on stretchers, are very uncomfortable.18 20 50 At the community meeting held at the completion of the study, men complained that ambulances were unavailable for deliveries as has been found in other areas of Ethiopia.84 87

Perceived benefits and needs

We found men are primarily responsible for making household decisions, including decisions about whether their wives seek healthcare. Yet, 90% of men believed their wives had attended ANC during their pregnancy, while only 29% of women reported doing so. Educating men on home delivery’s potential dangers and FBD’s benefits could potentially increase families choosing FBD. Barry et al 88 showed women who attended two or more family education meetings on maternal health with family members were nearly twice as likely to deliver with SBA or HEW compared with women who attended fewer than two meetings, but no difference for women who attended alone. Intervention studies involving partners or other family support in maternal education are needed.

Limitations

Generalisability

Based on household characteristics, our study population appears wealthier than the 2011 rural Ethiopian population. However, Ethiopia’s economy has experienced 10.8% average growth from 2003–2004 to 2013–2014.89 Therefore, other rural areas in Ethiopia may have also experienced similar improvements in living standards. The high percentage of Protestants in this study may limit generalisability to Orthodox or Moslem communities. Also, much of Sidama has a much higher population density than other areas, such as Afar Region, so distance may be less of a concern for women giving birth in Sidama.

The household list used to select participants came from paper-based registers and patient charts, which made identifying eligible participants difficult. Families who lived near health posts or attended clinic may have been over-represented. Although the health workers were expected to visit every home, staffing limitations make this difficult to accomplish. This may limit generalisability.

Missing variables

The ability to recognise emergencies may influence the decision of where to deliver.83 The original study plan included a DCE in which respondents were asked where they would deliver if they believed the mother or baby’s life was in danger. This portion was dropped due to interview length. In addition, the perceived need measure, which the Three Delays model predicts influences decisions to seek care, was not included in the analysis due to discrepancies in interpreting the danger signs’ questions. Finally, while this study included men, mothers-in-law, traditional birth attendants and other older women may also influence birth place decisions.18 19 58

Conclusion

This study makes a unique contribution to the literature as the first known DCE to test both women and men’s preferences in choosing FBD services. Including men acknowledged the role men play in making decisions for their families either alone or in collaboration with their partner. Women and men were found to agree on preferring facilities that always had medications and supplies available and allowed support persons in the delivery room. Facilities that respond to these preferences for higher quality and culturally appropriate care may increase FBD uptake.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Dr John Rose advised on the design of the discrete choice experiment (DCE). Getahun Wajebo and Worke Mekuriya conducted the interviews and gave invaluable advice on Ethiopian culture, translation and survey organisation. Donna Sillan and Tsegaye Bekele and the staff of Common River provided entrée to the community and logistical support. Finally, this research would not have been possible without the support of the leadership of Titira and Woto, and the women and men in these communities who opened their homes to the research team.

Footnotes

Contributors: Nancy K Beam, Gezahegn Bekele Dadi, Sally H Rankin, Sandra Weiss, Bruce Cooper and Lisa M Thompson participated in the conception of the study. NKB and GBD participated in the acquisition of the data. NKB designed the DCE. BC and NKB participated in the analysis and interpretation of the data. All authors participated in drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content. All authors gave final approval of the version to be published. All authors agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding: This work was supported by Sigma Theta Tau International (STTI) Small Grant, STTI Alpha Eta Chapter, and UCSF Century Fund.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: UCSF CHR and Hawassa University IRB.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Raw data are available by request from the corresponding author.

References

- 1. CSA [Ethiopia] and ICF International. Ethiopia demographic and health survey 2011. Maryland, USA: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia and Calverton, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2. WHO. Ethiopia | Maternal health [Internet]. 2015. http://www.afro.who.int/en/ethiopia/country-programmes/topics/4459-maternal-health.html (accessed 14 Sep 2016).

- 3. Campbell OM, Graham WJ; Lancet Maternal Survival Series steering group. Strategies for reducing maternal mortality: getting on with what works. Lancet 2006;368:1284–99. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69381-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. WHO. Making pregnancy safer : the critical role of the skilled attendant: a joint statement by WHO, ICM and FIGO [Internet. Geneva, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Admasu K, Haile-Mariam A, Bailey P. Indicators for availability, utilization, and quality of emergency obstetric care in Ethiopia, 2008. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2011;115:101–5. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2011.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ethiopian Federal Ministry of Health. Health sector transformation plan (2015/16-2019/20, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Federal Ministry of Health, UNICEF, UNFPA, WHO A. National baseline assessment for emergency obstetric & newborn care: Ethiopia 2008: Addis Ababa, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shiferaw S, Spigt M, Godefrooij M, et al. . Why do women prefer home births in Ethiopia? BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2013;13:5 10.1186/1471-2393-13-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gabrysch S, Lema C, Bedriñana E, et al. . Cultural adaptation of birthing services in rural Ayacucho, Peru. Bull World Health Organ 2009;87:724–9. 10.2471/BLT.08.057794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Olayo R, Wafula C, Aseyo E, et al. . A quasi-experimental assessment of the effectiveness of the Community Health Strategy on health outcomes in Kenya. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14 (Suppl 1):S3 10.1186/1472-6963-14-S1-S3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hounton S, Byass P, Brahima B. Towards reduction of maternal and perinatal mortality in rural Burkina Faso: communities are not empty vessels. Glob Health Action 2009;2:1947 10.3402/gha.v2i0.1947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gabrysch S, Campbell OM. Still too far to walk: literature review of the determinants of delivery service use. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2009;9:34 10.1186/1471-2393-9-34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. King R, Jackson R, Dietsch E, et al. . Barriers and facilitators to accessing skilled birth attendants in Afar region, Ethiopia. Midwifery 2015;31:540–6. 10.1016/j.midw.2015.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sipsma H, Thompson J, Maurer L, et al. . Preferences for home delivery in Ethiopia: provider perspectives. Glob Public Health 2013;8:1014–26. 10.1080/17441692.2013.835434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Abera M, Gebremariam A, Belachew T. Predictors of safe delivery service utilization in arsi zone, South-East ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci 2011;21(Suppl 1):95–106. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bedford J, Gandhi M, Admassu M, et al. . “A normal delivery takes place at home”: a qualitative study of the location of childbirth in rural Ethiopia. Matern Child Health J 2013;17:230–9. 10.1007/s10995-012-0965-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Birmeta K, Dibaba Y, Woldeyohannes D. Determinants of maternal health care utilization in Holeta town, central Ethiopia. BMC Health Serv Res 2013;13:256 10.1186/1472-6963-13-256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gebrehiwot T, Goicolea I, Edin K, et al. . Making pragmatic choices: women’s experiences of delivery care in Northern Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2012;12:113 10.1186/1471-2393-12-113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jackson R. The place of birth in Kafa Zone, Ethiopia. Health Care Women Int 2014;35:728–42. 10.1080/07399332.2014.914940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Roro MA, Hassen EM, Lemma AM, et al. . Why do women not deliver in health facilities: a qualitative study of the community perspectives in south central Ethiopia? BMC Res Notes 2014;7:556 10.1186/1756-0500-7-556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gebrehiwot T, San Sebastian M, Edin K, et al. . Health workers’ perceptions of facilitators of and barriers to institutional delivery in Tigray, Northern Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014;14:137 10.1186/1471-2393-14-137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Warren C. Care seeking for maternal health: challenges remain for poor women. Ethiop J Heal Dev 2010;24:100–4. 10.4314/ejhd.v24i1.62950 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bradley E, Thompson JW, Byam P, et al. . Access and quality of rural healthcare: Ethiopian Millennium Rural Initiative. Int J Qual Health Care 2011;23:222–30. 10.1093/intqhc/mzr013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ethiopian Society of Population Studies. Maternal health care seeking behaviour in Ethiopia : findings from EDHS 2005, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dutamo Z, Assefa N, Egata G. Maternal health care use among married women in Hossaina, Ethiopia. BMC Health Serv Res 2015;15:365 10.1186/s12913-015-1047-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Woldemicael G. Do women with higher autonomy seek more maternal health care? Evidence from Eritrea and Ethiopia. Health Care Women Int 2010;31:599–620. 10.1080/07399331003599555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wado YD, Afework MF, Hindin MJ. Unintended pregnancies and the use of maternal health services in Southwestern Ethiopia. BMC Int Health Hum Rights 2013;13:36 10.1186/1472-698X-13-36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yebyo H, Alemayehu M, Kahsay A. Why do women deliver at home? Multilevel modeling of Ethiopian National Demographic and Health Survey data. PLoS One 2015;10:e0124718 10.1371/journal.pone.0124718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hailu D, Berhe H. Determinants of institutional childbirth service utilisation among women of childbearing age in urban and rural areas of Tsegedie district, Ethiopia. Midwifery 2014;30:1109–17. 10.1016/j.midw.2014.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wilunda C, Quaglio G, Putoto G, et al. . Determinants of utilisation of antenatal care and skilled birth attendant at delivery in South West Shoa Zone, Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. Reprod Health 2015;12:74 10.1186/s12978-015-0067-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nigussie M, Mariam DH, Mitike G. Assessment of safe delivery service utilization among women of childbearing age in north Gondar Zone, north west Ethiopia. Ethiop J Heal Dev 2004;18:145–52. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hagos S, Shaweno D, Assegid M, et al. . Utilization of institutional delivery service at Wukro and Butajera districts in the Northern and South Central Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014;14:178 10.1186/1471-2393-14-178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tekelab T, Yadecha B, Melka AS. Antenatal care and women’s decision making power as determinants of institutional delivery in rural area of Western Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes 2015;8:769 10.1186/s13104-015-1708-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mekonnen ZA, Lerebo WT, Gebrehiwot TG, et al. . Multilevel analysis of individual and community level factors associated with institutional delivery in Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes 2015;8:376 10.1186/s13104-015-1343-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mengesha ZB, Biks GA, Ayele TA, et al. . Determinants of skilled attendance for delivery in Northwest Ethiopia: a community based nested case control study. BMC Public Health 2013;13:130 10.1186/1471-2458-13-130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Feyissa TR, Genemo GA. Determinants of institutional delivery among childbearing age women in Western Ethiopia, 2013: unmatched case control study. PLoS One 2014;9:e97194 10.1371/journal.pone.0097194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Amano A, Gebeyehu A, Birhanu Z. Institutional delivery service utilization in Munisa Woreda, South East Ethiopia: a community based cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2012;12:105 10.1186/1471-2393-12-105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tarekegn SM, Lieberman LS, Giedraitis V. Determinants of maternal health service utilization in Ethiopia: analysis of the 2011 Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014;14:161 10.1186/1471-2393-14-161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Afework MF, Admassu K, Mekonnen A, et al. . Effect of an innovative community based health program on maternal health service utilization in north and south central Ethiopia: a community based cross sectional study. Reprod Health 2014;11:28 10.1186/1742-4755-11-28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Asres A, Davey G. Factors associated with safe delivery service utilization among women in Sheka zone, southwest Ethiopia. Matern Child Health J 2015;19:859–67. 10.1007/s10995-014-1584-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bayou NB, Gacho YH. Utilization of clean and safe delivery service package of health services extension program and associated factors in rural kebeles of Kafa Zone, Southwest Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci 2013;23:79–89. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bayu H, Adefris M, Amano A, et al. . Pregnant women’s preference and factors associated with institutional delivery service utilization in Debra Markos Town, North West Ethiopia: a community based follow up study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015;15:15 10.1186/s12884-015-0437-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kebede B, Gebeyehu A, Andargie G. Use of previous maternal health services has a limited role in reattendance for skilled institutional delivery: cross-sectional survey in Northwest Ethiopia. Int J Womens Health 2013;5:79–85. 10.2147/IJWH.S40335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Melaku YA, Weldearegawi B, Tesfay FH, et al. . Poor linkages in maternal health care services-evidence on antenatal care and institutional delivery from a community-based longitudinal study in Tigray region, Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014;14:418 10.1186/s12884-014-0418-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Teferra AS, Alemu FM, Woldeyohannes SM. Institutional delivery service utilization and associated factors among mothers who gave birth in the last 12 months in Sekela District, north west of Ethiopia: a community-based cross sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2012;12:74 10.1186/1471-2393-12-74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Worku AG, Yalew AW, Afework MF. Maternal complications and women’s behavior in seeking care from skilled providers in North Gondar, Ethiopia. PLoS One 2013;8:e60171 10.1371/journal.pone.0060171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Worku AG, Yalew AW, Afework MF. Factors affecting utilization of skilled maternal care in Northwest Ethiopia: a multilevel analysis. BMC Int Health Hum Rights 2013;13:20 10.1186/1472-698X-13-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Tsegay Y, Gebrehiwot T, Goicolea I, et al. . Determinants of antenatal and delivery care utilization in Tigray region, Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Int J Equity Health 2013;12:30 10.1186/1475-9276-12-30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Habte F, Demissie M. Magnitude and factors associated with institutional delivery service utilization among childbearing mothers in Cheha district, Gurage zone, SNNPR, Ethiopia: a community based cross sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015;15:299 10.1186/s12884-015-0716-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Fikre AA, Demissie M. Prevalence of institutional delivery and associated factors in Dodota Woreda (district), Oromia regional state, Ethiopia. Reprod Health 2012;9:33 10.1186/1742-4755-9-33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Abeje G, Azage M, Setegn T. Factors associated with Institutional delivery service utilization among mothers in Bahir Dar City administration, Amhara region: a community based cross sectional study. Reprod Health 2014;11:22 10.1186/1742-4755-11-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Tura G, Afework MF, Yalew AW. The effect of birth preparedness and complication readiness on skilled care use: a prospective follow-up study in Southwest Ethiopia. Reprod Health 2014;11:60 10.1186/1742-4755-11-60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Abebe F, Berhane Y, Girma B. Factors associated with home delivery in Bahirdar, Ethiopia: a case control study. BMC Res Notes 2012;5:653 10.1186/1756-0500-5-653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ballard K, Gari L, Mosisa H, et al. . Provision of individualised obstetric risk advice to increase health facility usage by women at risk of a complicated delivery: a cohort study of women in the rural highlands of West Ethiopia. BJOG 2013;120:971–8. 10.1111/1471-0528.12190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Holden ST, Tefera T. From being property of men to becoming equal owners? early impacts of land registration and certification on women, 2008:1–110. http://www.unhsp.org/downloads/docs/10768_1_594333.pdf

- 56. Kumar N, Quisumbing AR. Policy reform toward gender equality in ethiopia: little by little the egg begins to walk. World Dev 2015;67:406–23. 10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.10.029 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Biratu B, Lindstrom D. The influence of husbands’ approval on women’s use of prenatal care: Results from Yirgalem and Jimma towns, south west Ethiopia. Ethiop J Heal Dev 2007;20:84–92. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Jackson R, Tesfay FH, Godefay H, et al. . and Mothers’ Attitudes to Maternal Health Service Utilization and Acceptance in Adwa Woreda, Tigray Region, Ethiopia. Roy JK, editor. PLoS One 2016;11:e0150747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Kruk ME, Paczkowski MM, Tegegn A, et al. . Women’s preferences for obstetric care in rural Ethiopia: a population-based discrete choice experiment in a region with low rates of facility delivery. J Epidemiol Community Health 2010;64:984–8. 10.1136/jech.2009.087973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Ryan M, Scott DA, Reeves C, et al. . Eliciting public preferences for healthcare: a systematic review of techniques. Health Technol Assess 2001;5:1-186 10.3310/hta5050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Bridges JFP, Hauber AB, Marshall D, et al. . Conjoint analysis applications in health-a checklist: a report of the ISPOR good research practices for conjoint analysis task force. Value in Health 2011;14:403–13. 10.1016/j.jval.2010.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Rose JM, Bliemer MCJ. Sample size requirements for stated choice experiments. Transportation 2013;40:1021–41. 10.1007/s11116-013-9451-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Beam NK. Women and men’s preferences for delivery services in rural Ethiopia (Doctoral dissertation) [Internet]. California, San Francisco: University of California, 2016. https://pqdtopen.proquest.com/doc/1801982908.html?FMT=ABS [Google Scholar]

- 64. Rose JM, Collins AT, Bliemer MCJ, et al. ; Ngene [Internet]: ChoiceMetrics, 2014. http://www.choice-metrics.com [Google Scholar]

- 65. ChoiceMetrics. Ngene 1.1.2 User Manual & Reference Guide [Internet: ChoiceMetrics, 2014. http://www.choice-metrics.com [Google Scholar]

- 66. Population Census Commission. The population and housing census of Ethiopia: SNNPR [Internet]. 2007. phe-ethiopia.org/pdf/snnpr.pdf

- 67. Bradley SEK, Winfrey W. TNC. Contraceptive Use and Perinatal Mortality in the DHS: An Assessment of the Quality and Consistency of Calendars and Histories [Internet]. DHS Methodological Reports No. 17. Rockville, Maryland, USA: ICF International, 2015. http://dhsprogram.com/publications/publication-MR17-Methodological-Reports.cfm [Google Scholar]

- 68. Assaf S, Kothari MT. TP. An Assessment of the Quality of DHS Anthropometric Data, 2005-2014 [Internet]. DHS Methodological Reports No. 16. Rockville, Maryland, USA: ICF International, 2015. http://dhsprogram.com/publications/publication-MR16-Methodological-Reports.cfm#sthash.PLYVphzr.dpuf [Google Scholar]

- 69. Rutstein SO. Potential bias and selectivity in analyses of children born in the past five years using DHS data. DHS Methodol Reports No 14 [Internet]. 2014. http://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/MR14/MR14.pdf

- 70. Ahmed S, Li Q, Scrafford C, et al. . An assessment of DHS maternal mortality data and estimates [Internet]. DHS Methodological Reports No. 13. 2014. http://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/MR13/MR13.pdf

- 71. Schoumaker B. Quality and consistency of DHS fertility estimates, 1990 to 2012. DHS Methodol Reports No 12 [Internet]. 2014. http://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/MR12/MR12.pdf

- 72. Pullum TW, Becker S. Evidence of omission and displacement in DHS birth histories. DHS Methodol Reports No 11 [Internet]. 2014. http://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/MR11/MR11.pdf

- 73. Pullum TW. An assessment of the quality of data on health and nutrition in the DHS Surveys, 1993-2003 [Internet]. DHS methodological reports no. 6. Calverton, Maryland, USA: Macro International, 2008:1–139. [Google Scholar]

- 74. Pullum TW. An assessment of age and date reporting in the DHS surveys, 1985-2003. DHS Methodol Reports No 5 [Internet]. 2006;4 http://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/MR5/MR5.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 75. Boerma J, Ties A, Sommerfelt E, et al. ; Stewart and SOR-S more at: http://dhsprogram.com/publications/publicatio.-M-M-R cfm#sthash. 9SKwUnbk. dpu. An assessment of the quality of health data in DHS-I surveys [internet]. DHS methodological reports no. 2. Calverton, Maryland, USA: Macro International, 1994. http://dhsprogram.com/publications/publication-MR2-Methodological-Reports.cfm#sthash.9SKwUnbk.dpuf [Google Scholar]

- 76. Rutstein SO, Bicego GT, Blanc AK, et al. . An assessment of DHS-I data quality. DHS methodological reports No.1, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 77. Mangham LJ, Hanson K, McPake B. How to do (or not to do)… Designing a discrete choice experiment for application in a low-income country. Health Policy Plan 2009;24:151–8. 10.1093/heapol/czn047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Alkire S. The Missing Dimensions of Poverty Data: Introduction to the Special Issue. Oxford Dev Stud 2007;35:347–59. 10.1080/13600810701701863 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Alkire S, Foster J. Counting and multidimensional poverty measurement. J Public Econ 2011;95:476–87. 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2010.11.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80. UNDP. Human development report 2015: technical notes [Internet]. 2015.

- 81. StataCorp. Stata Multilevel mixed-effects reference manual. 13th ed College Station, TX: StataCorp LP, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 82. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. . Research electronic data capture (REDCap)-a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42:377–81. 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Thaddeus S, Maine D. Too far to walk: maternal mortality in context. Soc Sci Med 1994;38:1091–110. 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90226-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Jackson R, Hailemariam A. The role of health extension workers in linking pregnant women with health facilities for delivery in rural and pastoralist areas of Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci 2016;26:471 10.4314/ejhs.v26i5.9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Kok MC, Kea AZ, Datiko DG, et al. . A qualitative assessment of health extension workers’ relationships with the community and health sector in Ethiopia: opportunities for enhancing maternal health performance. Hum Resour Health 2015;13:80 10.1186/s12960-015-0077-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Rogers EM. Diffusion of innovations. Fifth New York: Free Press, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 87. Jackson R, Tesfay FH, Gebrehiwot TG, et al. . Factors that hinder or enable maternal health strategies to reduce delays in rural and pastoralist areas in Ethiopia. Trop Med Int Heal 2017;22:148–60. 10.1111/tmi.12818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Barry D, Frew AH, Mohammed H, et al. . The effect of community maternal and newborn health family meetings on type of birth attendant and completeness of maternal and newborn care received during birth and the early postnatal period in rural Ethiopia. J Midwifery Womens Health 2014;59 (Suppl 1):S44–S54. 10.1111/jmwh.12171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. World Bank. Ethiopia overview [Internet]. 2015. http://www.worldbank.org/

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.