Abstract

Objectives

This paper investigates (1) how social relationships (SRs) relate to the frequency of general practitioner (GP) visits among middle-aged and older adults in Europe, (2) if SRs moderate the association between self-rated health and GP visits, and (3) how the associations vary regarding employment status.

Methods

Data stem from the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe project (wave 4, 56 989 respondents, 50 years or older). GP use was assessed by frequency of contacts with GPs in the last 12 months. Predictors were self-rated health and structural (Social Integration Index (SII), social contact frequency) and functional (emotional closeness) aspects of SR. Regressions were used to measure the associations between GP use and those predictors. Sociodemographic and socioeconomic factors were used as covariates. Additional models were computed with interactions.

Results

Analyses did not reveal significant associations of functional and structural aspects of SR with frequency of GP visits (SII: incidence rate ratio (IRR)=0.99, 95% CI 0.97 to 1.01, social contact frequency: IRR=1.04, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.07, emotional closeness: IRR=1.02, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.04). Moderator analyses showed that ‘high social contact frequency people’ with better health had more statistically significant GP visits than ‘low social contact frequency people’ with better health. Furthermore, people with poor health and an emotionally close network showed a significantly higher number of GP visits compared with people with same health, but less close networks. Three-way interaction analyses indicated employment status specific behavioural patterns with regard to SR and GP use, but coefficients were mostly not significant. All in all, the not employed groups showed a higher number of GP visits.

Conclusions

Different indicators of SR showed statistically insignificantly associations with GP visits. Consequently, the relevance of SR may be rated rather low in quantitative terms for investigating GP use behaviour of middle-aged and older adults in Europe. Nevertheless, investigating the two-way and three-way interactions indicated potential inequalities in GP use due to different characteristics of SR accounting for health and employment status.

Keywords: social relationships, general practitioners, health services research, employment status, middle-aged and older adults, self-rated health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is one of the first studies to systematically analyse the associations between self-rated health, social relationship (SR), employment status and frequency of general practitioner use of middle-aged and older adults in Europe.

Applying a survey design to account for the stratification in the sample allows drawing conclusions about non-institutionalised adults aged 50 years or older in 16 European countries.

In contrast to other studies, SRs were assessed multidimensionally focusing on both, structural and functional aspects.

The cross-sectional design of the study does not allow drawing conclusions about causalities.

Introduction

According to the ‘Behavioural Model of Health Services Use’ by Andersen, utilisation of health services is influenced by a variety of predisposing, enabling and need characteristics.1 Existing literature has highlighted that health status, defined as a ‘need factor’, is the most powerful predictor of health services use in older age.2–6 Furthermore, adults within their 50s or older show more chronic illnesses and increased rates of healthcare use compared with younger cohorts.7 Consequently, healthcare systems are challenged by increasing health needs and rising demands for health services in ageing societies.8 In particular, the sector of primary healthcare is affected by these developments, since general practitioners (GPs) are the first contact to healthcare, acting as gatekeepers and navigators.

Within Andersen’s model, social relationships (SRs) are defined as ‘enabling resources’ for health and the use of health services.1 International studies suggest substantial impact of SRs on morbidity and mortality.9–12 Moreover, research indicates the significance of SRs by enhancing patient care, improving compliance with medical schemes and fostering shorter hospital stays.13–15 SRs can be divided into structural and functional elements.9 Structural aspects of SRs, for example, the degree of social network integration, are assessed by quantitative measures (eg, living arrangements, social network size and frequency of social participation). Received and perceived social support is defined as a functional element, and includes aspects of financial, instrumental, informational or emotional support. Both aspects of SRs can be subject to change due to life events across the life span, especially in older age,16 as they are affected and modified by events, such as widowhood, unemployment or retirement.16–18

So far, studies on older adults’ GP use have shown an ambiguous role of SRs.19–22 In most cases, regression models were applied to show that various aspects of SRs are associated with the frequency of health services consultations within a certain time span.23–26 Andersen’s model suggests a variety of interactions between predisposing, enabling and need factors on health services use, but only a few studies adopted analyses to capture potential moderating or mediating action.27–33 As mentioned before, health status is strongly associated with the frequency of using health services, on the one hand. On the other hand, SRs are closely linked to health.10 12 34 Consequently, SRs might influence the scope of action, such as using GP services, depending on varying self-rated health status. Do SRs have an impact on the strong link between self-rated health and health services use? And, if applicable, does that implicate anything for public health policy and healthcare providers? So far, the association between SRs, self-rated health and GP visits among middle-aged and older adults is poorly understood.

Focusing on adults 50 years or older, this paper investigates (1) how SRs relate to the frequency of GP visits and (2) if SRs moderate the association between self-rated health and GP visits. Since, SRs are subject to change due to age-related life events, such as retirement, unemployment and permanent disability, this study additionally analyses (3) how the associations vary through subgroups of different employment status. Hence, this study may contribute to a better understanding of the behavioural patterns of using GP services within the middle-aged and olderi European population.

Data and methods

Data

Analyses are based on data from the fourth wave of the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE).35–38 ’SHARE has been submitted to, and approved by, the ethics committee at the University of Mannheim which was the legally responsible entity for SHARE during wave four’.38 Following the SHARE conditions of use, the ethical approval for the SHARE study also applies to this analysis.39 Data were collected in 2010 and 2011 from 16 European countries (Austria, Germany, Sweden, the Netherlands, Spain, Italy, France, Denmark, Switzerland, Belgium, Czech Republic, Poland, Hungary, Portugal, Slovenia and Estonia). Based on population registers, SHARE uses probability samples within the countries and includes non-institutionalised adults aged 50 years or older and, if available, their partners. Further exclusion criteria are being incarcerated, moved abroad, unable to speak the language of questionnaire, deceased, hospitalised, moved to an unknown address or not residing at the sampled address.36 38 By focusing on an older age group, SHARE matches our research questions very well, since health needs increase significantly and crucial changes in the life course occur (eg, retirement). Furthermore, SHARE offers a substantial sample size (wave 4: 56 989 main interviews of respondents aged 50 years or older in 39 807 households).

SHARE uses an ex ante harmonisation regarding the survey design, which means that questionnaires and field procedures are standardised across countries to maximise options for cross-national comparisons40 to ensure the ex ante harmonisation of the survey, ‘(…) SHARE employs three instruments: the SHARE Model Contract provides the legal framework for standards and quality control; the SHARE Survey Specifications define the quality standards of the survey ex ante; and the SHARE Compliance Profiles report adherence to those standards ex post’.40 In wave 4, ‘(…) contact rates of households were satisfactory (≥90%) in almost all countries, both in panel and refreshment samples. Refusal rates ranged from 22% to 49% and were the prime reason for sampled households not providing an interview’.40 To handle possible selection and participation biases, SHARE offers sample design weights35 38 (for further details please see analyses section).

Patient and public involvement

Patients and public were not involved in the development of the research question and the selection of outcome measures. On the basis of the SHARE documentation there is no detailed information available on the role of patients and the public designing and conducting the study.41 42 All in all, SHARE is based on the US Health and Retirement Study and the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing.41

Measures

Interviews of the fourth SHARE wave included several items concerning healthcare. Before asking explicitly for GP visits, the following more general question was asked: ‘During the last twelve months, about how many times in total have you seen or talked to a medical doctor about your health (exclude: dentist visits and hospital stays, include emergency room or outpatient clinic visits)?’. If respondents accounted for more than 98 contacts, the number 98 was entered. The dependent variable, GP visits, was assessed by the reported number of contacts with GPs or doctors at healthcare centres in the last 12 months prior to the interview: ‘How many of these contacts were with a general practitioner or with a doctor at your healthcare centre?’.

Predictors were self-rated health and SRs with a focus on structural (Social Integration Index (SII), social contact frequency in the social network) and functional (number of emotionally close ties) dimensions.

SII by Berkman et al43 has been shown to be a reliable and robust approach to represent the multidimensional construct of social integration. The index consists of three domains (1: marital status and cohabitation, 2: contacts with friends and family, 3: affiliation with voluntary associations; each scored from 0 to 2) ranging from 0 to 6, with 0 points meaning low integration and 6 points meaning high integration into their social environment.

First domain: if the respondent was single, divorced or widowed, 0 points were given, and 2 points, if the person was married or living with a partner. ‘What is your marital status? 1. Married and living together with spouse, 2. Registered partnership, 3. Married, living separated from spouse, 4. Never married, 5. Divorced, 6. Widowed’. This item was dichotomised to having a partner or not. Second domain: the number of social ties to different people was counted and transformed into three categories connected to different scores (0: 0 contacts, 1: 1–2 contacts, 2: three or more contacts). This categorisation is based on the answers to the following question: ‘Please give me the first name of the person with whom you often discuss things that are important to you’. Respondents could name up to seven people. Third domain: the affiliation with voluntary organisations was measured by activities in any of the five social groups: ‘Which of the activities have you done in the past twelve months? 1. Done voluntary or charity work, 2. Attended an educational or training course, 3. Gone to a sport, social or other kind of club, 4. Taken part in activities of a religious organisation (church, synagogue, mosque etc.), 5. Taken part in a political or community-related organisation’. Being part of no organisation resulted in a score of 0, one organisation meant 1 point and two or more memberships scored 2 points.

Furthermore, the survey included items on the characteristics of SRs, for example, social contact frequency and emotional closeness to people in the personal network. This module was based on other similar studies, such as the National Social Life, Health and Ageing Project,44 the American General Social Survey and the Longitudinal Ageing Study Amsterdam.45–47 Social contact frequency was assessed by the following question: ‘During the past twelve months, how often did you have contact with (person XY) either personally, by phone or mail? 1. Daily, 2. Several times a week, 3. About once a week, 4. About every 2 weeks, 5. About once a month, 6. Less than once a month or never’. The analyses include the average social contact frequency in the personal network. The question on emotional closeness to the personal network members is: ‘How close do you feel to (person XY)? 1. Not very close, 2. Somewhat close, 3. Very close, 4. Extremely close’. For the analyses, the number of very or extremely close people in the personal network was counted (range: 0 to 7). Consequently, it represents a structural and functional dimension of SRs.

We used self-rated health (‘Would you say your health is…?’) on a 5-point-scale (‘0. Poor, 1. Fair, 2. Good, 3. Very good, 4. Excellent’) to assess the peoples’ health status.

Sociodemographic (gender, age) and socioeconomic (education, employment status, income: make ends meet) factors were used as covariates (online supplementary table 1). Education was based on the International Standard Classification of Education (1997) and ranged from 0 to 6 (low to higher education). Employment status was split into five categories (0=employed, 1=retired, 2=unemployed, 3=permanently sick or disabled and 4=homemaking respondents). Material well-being of individuals was measured by the question: ‘Thinking of your household’s total monthly income, would you say that your household is able to make ends meet…?’ (0=with great or some difficulty, 1=fairly easy or easy).

bmjopen-2017-018854supp001.pdf (62.7KB, pdf)

The correlation matrix of the covariates did not reveal strong or very strong associations between similar variables (online supplementary table 1). The highest correlation was found between education and financial distress (r=0.22). Hence, the level of confounding within the following analyses can be rated as low to moderate.

Analyses

Regression models were used to analyse the associations between GP use and the predictors. The dependent variable ‘reported number of GP visits in the last 12 months’ is a discrete count variable following a Poisson distribution. As the variance of the dependent variable is greater than its mean, negative binomial regression was used to account for the significant evidence of overdispersion. Furthermore, negative binomial regression models include a parameter that reflects unobserved heterogeneity among observations.48

Due to the complex sample structure, including individual level, household level and country level, a survey design was implemented.35 49To account for within-household correlations and between-country differences, households were defined as primary sampling unit and countries as strata. Furthermore, to adjust for variation in selection probabilities by design and for variation in participation probabilities caused by non-response, sample design weights were used.38 In the case of Stata the survey command and in R the survey package were used to adequately handle weighted and stratified data.50–52

Since this study aimed to analyse potential moderation of SRs on the association between self-rated health and GP use, interaction terms were introduced.53 Three different two-way interaction terms were calculated: (1) self-rated health*SII, (2) self-rated health*average of social contact frequency in social networks and (3) self-rated health*number of very to extremely close people in social networks. Finally, three-way interactions were computed to elaborate the role of the employment status within the interaction between health and SRs (health*social relationship*employment status). The analyses were performed with Stata V.12 and were replicated with R.54

Results

Our descriptive results are based on the unweighted sample (table 1). The median of the reported number of GP visits in the last 12 months was 3. More than half of the participants were female and the mean age was about 66.4 years; 26% were employed and 39% had difficulty to make ends meet with regard to their income.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of the sample (SHARE, wave 4, 2011, 16 countries)

| Variables | |

| GP visits*, median/25th centile/75th centile/mean (SD) | 3/2/6/5.08 (7.38) |

| Female, N (%) | 31 969 (56.10) |

| Age in years†, mean (SD) | 66.37 (10.05) |

| Education‡ (ISCED-1997 coding: 0=low – 6=high), mean (SD) | 2.77 (1.44) |

| Preprimary | 1682 (2.95) |

| ISCED-1997 code 1 (primary) | 10 943 (19.20) |

| ISCED-1997 code 2 (lower-secondary) | 10 804 (18.96) |

| ISCED-1997 code 3 (upper-secondary) | 18 751 (32.90) |

| ISCED-1997 code 4 (postsecondary and non-tertiary) | 2597 (4.56) |

| ISCED-1997 code 5 (first stage of tertiary) | 10 514 (18.45) |

| ISCED-1997 code 6 (second stage of tertiary) | 454 (0.80) |

| Job status§, N (%) | |

| Employed | 14 736 (25.86) |

| Retired | 35 207 (61.78) |

| Unemployed | 1.821 (3,20) |

| Permanently sick or disabled | 1.863 (3.27) |

| Homemaker | 2265 (3.97) |

| Income: make ends meet¶, N (%) | |

| With great or some difficulty | 22 319 (39.16) |

| Fairly easy or easy | 33 157 (58.18) |

| Self-rated health (0=poor to 4=excellent)**, mean (SD) | 1.74 (1.08) |

| Poor | 7307 (12.82) |

| Fair | 16 841 (29.55) |

| Good | 19 754 (34.66) |

| Very good | 9066 (15.91) |

| Excellent | 3744 (6.57) |

| Social Integration Index (0=low to 6=high)††, mean (SD) | 3.55 (1.39) |

| Average of social contact frequency in social network (0=less than once per month or never to 5=daily)‡‡, mean (SD) | 4.07 (0.99) |

| Number of very to extremely close people in the social network (0–7)§§, mean (SD) | 2.16 (1.45) |

| Unweighted sample (number of observations) | n=56 989 |

Missing values (out of 56 989): *7296, †5, ‡1244, §1097, ¶1513, **277, ††1024, ‡‡4451, §§3385.

GP, general practitioner; ISCED, International Standard Classification of Education; SHARE, Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe.

Associations between SRs and GP visits

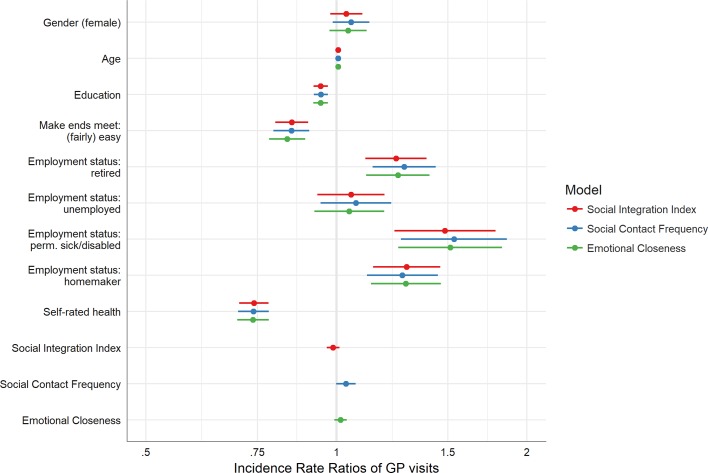

To answer research question (1), figure 1 shows the forest plots of incidence rate ratios of negative binomial regression models for GP use, for the different SR indicators (model 1: SII, model 2: average social contact frequency in social network and model 3: number of emotionally very close contacts).

Figure 1.

Forest plots of incidence rate ratios for general practitioner (GP) use.

The regression analysis of model 1 (figure 1, online supplementary table 2) shows that the SII is not statistically significantly associated with the rate of GP visits (IRR=0.99, 95% CI 0.97 to 1.01). Better self-rated health (IRR=0.74, 95% CI 0.70 to 0.78), easily making ends meet (IRR=0.85, 95% CI 0.80 to 0.90) and higher educational status (IRR=0.94, 95% CI 0.92 to 0.97) are strongly associated with lower frequency of GP visits. Older age shows a slightly positive association with a higher rate of GP visits (IRR=1.01, 95% CI 1.0 to 1.01). Not-employed persons show higher frequency of GP visits (employed: reference, retired: IRR=1.24, 95% CI 1.11 to 1.39, unemployed: IRR=1.05, 95% CI 0.93 to 1.19, permanently sick or disabled: IRR=1.48, 95% CI 1.24 to 1.78, homemaker: IRR=1.29, 95% CI 1.14 to 1.46). The regression analysis of model 2 (figure 1, online supplementary table 2) shows that the social contact frequency within a social network is not statistically significantly associated with the rate of GP visits (IRR=1.04, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.07). The regression analysis of model 3 (figure 1, online supplementary table 2) indicates that being closely connected is not statistically significantly associated with the rate of GP visits (IRR=1.02, 95% CI 0.99 to 1.04). In all three models, SR coefficients showed low magnitude and narrow CIs.

bmjopen-2017-018854supp002.pdf (54.4KB, pdf)

Moderation of SRs on health and GP use

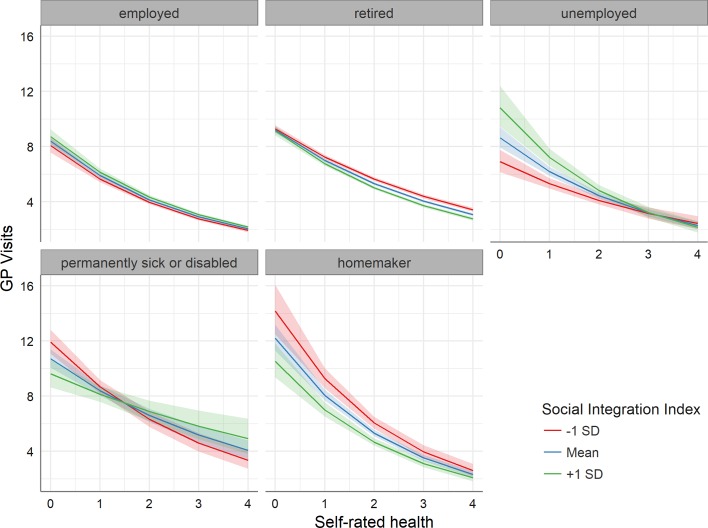

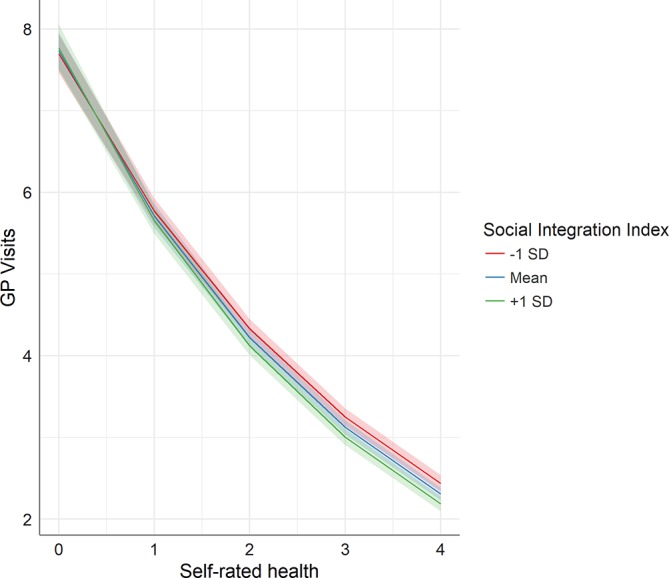

To answer research question (2), figure 2 shows the expected number of GP visits depending on the two-way interaction between health status and SII (online supplementary table 3). The blue line represents people with a mean level of social integration. The red line is based on a lower level of social integration (mean−SD), whereas the green line stands for a higher level of social integration (mean+SD).

Figure 2.

Number of general practitioner (GP) visits on health and social integration.

bmjopen-2017-018854supp003.pdf (56.5KB, pdf)

Starting at nearly eight visits per year for people with poor health, the estimated average number of visits steadily decreases with better health status, ending at about two visits for people with excellent self-rated health. This trend can be observed for all three levels of social integration, but taking the CIs into account, the divergence of the groups is not statistically significant at any level of health status. Nevertheless, the largest slope is detected for less socially integrated people and the smallest slope is documented for more socially integrated people.

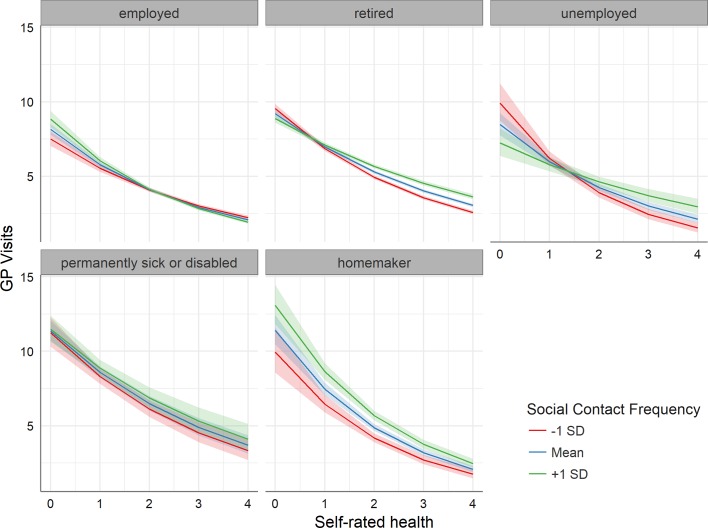

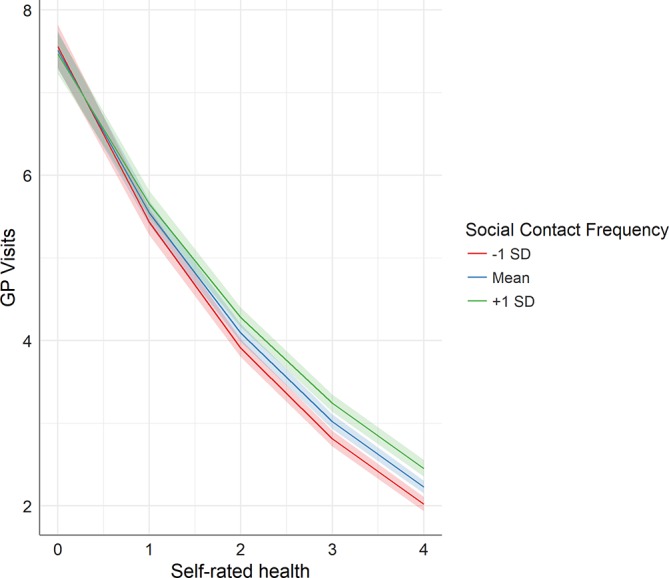

Figure 3 shows the number of GP visits in dependence of health and social contact frequency in social networks (online supplementary table 3).

Figure 3.

Number of general practitioner (GP) visits on health and social contact frequency.

All in all, the patterns are similar to figure 2, but the slopes of the groups with lower and higher contact frequencies are the other way round. The slope of estimated number of GP visits on self-rated health is steeper for those with lower social contact frequency. This association is statistically significant for people with a very good and excellent health, although the differences in the slopes are relatively small.

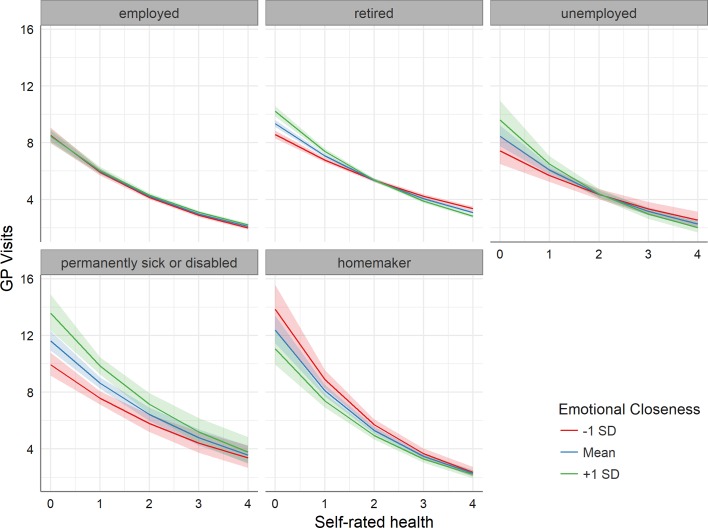

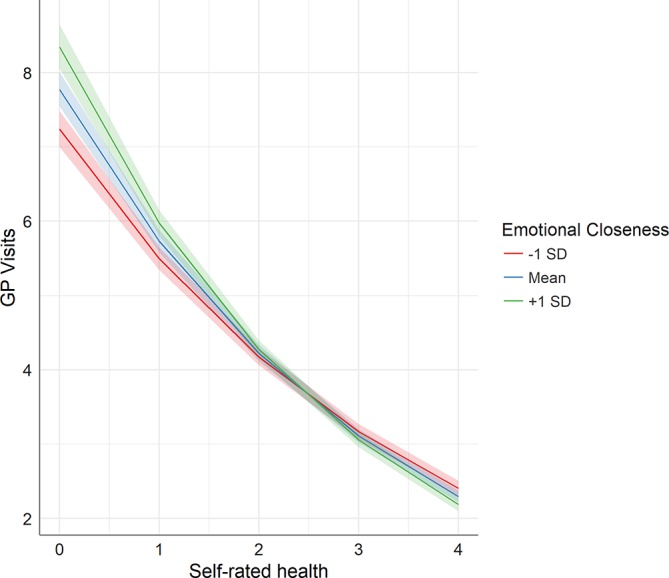

Figure 4 shows the expected number of GP visits according to various levels of subjective health and the number of very close people in social networks (online supplementary table 3).

Figure 4.

Number of general practitioner (GP) visits on health and emotional closeness.

Again, we see the downward trend of estimated average number of GP visits from poor to excellent health. In contrast to figure 3, group differences are only observable for people with poor health. People with poor health and an emotionally close network show a significantly higher number of GP visits compared with people with poor health and less closeness.

Moderation of SRs and employment types on health and GP visits

To answer research question (3), figures 5–7 incorporate the three-way interactions between health, SRs and employment status in relation to the number of GP visits. Figure 5 shows the expected number of GP visits depending on the three-way interaction between health, SII and employment status based on the full sample (online supplementary table 4).

Figure 5.

Number of general practitioner (GP) visits on health, social integration and employment status.

Figure 6.

Number of general practitioner (GP) visits on health, social contact frequency and employment status.

Figure 7.

Number of general practitioner (GP) visits on health, closeness and employment status.

bmjopen-2017-018854supp004.pdf (80.7KB, pdf)

The slopes of the different employment status groups are very diverse, in particular, when the disparate levels of social integration are taken into account. Retired, unemployed, permanently sick or disabled and homemaking people show higher numbers of GP visits on average compared with employed people. Furthermore, the diverging slopes of various social integration indices of those groups also indicate more between-group differences than employed people. Retired people with good, very good or excellent health, for instance, have more GP visits if they are less integrated than retirees who are socially well integrated. This association is inverse with regard to unemployed people with a lower health status.

Considering the social contact frequency, group differences depending on employment status and different grades of contact frequencies in social networks are similar to those seen for social integration (figure 6, online supplementary table 4).

Retired people with good to excellent health, for example, show more GP visits if their social contact frequency in their social network is high on average compared with lower contact frequencies. This association is also observable for homemaking people with an intermediate health status.

Figure 7 shows the estimated average number of GP visits depending on the three-way interaction between health, number of very close contacts and employment status (online supplementary table 4).

The slopes in the group of retired people show statistically significant differences between various levels of emotional closeness. A higher number of emotionally close contacts increases the expected number of GP visits, if retired people are characterised by poor or fair self-rated health. This association is also shown within the group of permanently sick or disabled people.

Discussion

Summary

Focusing on older adults in Europe, this was the first study to investigate (1) how SRs are associated with the frequency of GP visits, (2) if social ties moderate the association between self-rated health and GP use, and (3) how these associations vary in subgroups of different employment status.

Regarding research question (1), the structural (social integration, social contact frequency) and functional (number of emotionally close contacts) dimensions of SRs under investigation are not statistically significantly associated with GP use frequency. On the one hand, our results are in line with a number of studies on structural and functional aspects of SRs.5 24 55–57 Studies on structural aspects of SRs, for example, marital status, living arrangements and family size, showed no statistically significant associations with the frequency of physician use.55–57 Furthermore, studies on functional aspects of SRs, for example, social anchorage, social support and emotional, instrumental and informational support, demonstrated no statistically significant associations with regard to the use of primary care services.5 24 On the other hand, and with regard to structural measures of SRs, empirical results are inconsistent until now. Various studies on outpatient care use showed that older people living alone are more likely to consult a physician.23 58 59 One study showed that married older people have a lower probability of using GP services.24 Others demonstrated that older people living in a marriage or with their children present a higher frequency of physician consultations.25 26 With regard to the size of the social network, studies found negative associations,19 20 and others ambiguous21 or positive associations.22 Moreover, Kim and Konrath60 did not find a statistically significant association between volunteering and the frequency of doctor visits. A possible explanation for these inconsistent empirical patterns can be seen in the quality dimension of SRs to partners, family and social network members. For instance, Foreman et al26 found a negative association between harmonious family relationships and the number of physician visits. International studies on functional dimensions of SRs demonstrated that different aspects of received social support (eg, material, instrumental and informational support) are positively linked with GP use.3 32 61 Frequent and close social contacts are a potential source of social support, and for psychological distress and physical discomfort, conceivably leading to higher GP use rates.62 63

Regarding research question (2), the analyses show hardly any substantial and statistically significant moderating effects of different aspects of social relations on the link between self-rated health and frequency of GP visits. Only for older adults with poor self-rated health, an increase of the number of emotionally close members in the social network is associated with a growing rate of GP visits (figure 4). Furthermore, older adults with very good or excellent health show a higher rate of GP visits with an increase of their social contact frequency in the social network (figure 3), while social contact frequency seems to play a less important role for people with poorer health. Potentially, a higher density of social networks fosters GP use by providing support and resources, but only for people with better health. The differences are statistically significant, but they have a lower magnitude.

Three-way interaction analyses regarding research question (3) indicate employment status specific behavioural patterns with regard to SRs and GP use, but coefficients were mostly not significant. Analyses focusing on older people who are retired, unemployed, permanently sick or disabled or homemakers, show various results. All in all, the groups of retired, unemployed, permanently sick/disabled and homemaking people show a higher estimated average number of GP visits. Comparing those groups with each other also presents diverging patterns of associations. A higher level of social integration was associated with lower rates of GP use for retirees, but was associated with a higher frequency of visits for unemployed older adults, especially for unemployed older people with poor self-rated health (figure 5). ‘Having a partner’, which is included in the SII, contributed the most to this association. Atkinson et al18 showed that unemployment has a negative effect on marital and family support and a positive effect on the utilisation of external help including emotional support, information or advice and concrete assistance. Potentially, unemployed people struggle with their psychological well-being and with their SRs. Consequently, they use more external help including the consultation of GPs. Homemakers use more GP visits, if their social contact frequency is higher, especially, if their health status is rated as fair or good. This also holds true for retirees with a higher self-rated health status (figure 6). The more emotionally close are the contacts present, the higher is the use for GP doctors by retired and permanently sick or disabled people with lower health status (figure 7).

Limitations

When interpreting the results, some methodological limitations need to be taken into account. First, our analyses were based on cross-sectional data, forbidding statements on causal directions and changes over time. The cross-sectional design was chosen due to the inclusion of SR variables from SHARE’s ‘social networks’ module which was applied only in wave 4.35 36 64 Therefore, the postulated buffer function of social integration (of retirees and homemakers) on the reported number of GP visits in the last 12 months, for instance, has only one possible explanation. Another scenario may be the healthy user effect due to volunteering activities which are included in SII. Healthier people with less GP visits have more resources to invest into their social integration. Furthermore, some of the differences between employment types may be related to temporary resources, since employed people have less time available to consult their GP.

SHARE is an international survey aiming for high methodological standards by using ex ante harmonisation to minimise ‘artefacts in cross-national comparisons that are created by country-specific survey design’,40 but the schedule for data collection in wave 4 was only partly synchronised and household response rates vary between countries (39% to 63%). Due to unit non-response and panel attrition, sample selection bias is a potential problem limiting the representativeness of the data and the generalisability of results.36 However, non-response analyses taking various variables into account (gender, age, health, employment, number of children and income) showed only little evidence for non-response bias (eg, a slightly larger number of men among respondents than non-respondents).38

The question of assessing the use of GP doctors across 12 months is established in health services research,4 20 21 65 but has some methodological drawbacks. The question is narrowed to the reported number of GP or doctor visits at a healthcare centre. Contacts with nurses at GP practices are not taken into account. Potentially, the level of using primary care is underestimated. The time span covering the GP contacts is quite long, and considering the older age of the interviewed individuals, risk of memory bias is existent with regard to self-reported utilisation.66 Bhandari and Wagner found in their systematic review on self-reported utilisation of healthcare services that ‘(…) age was the most consistent demographic factor associated with self-report inaccuracy (…)’ by older adults under-reporting their use.66 Consequently, intercepts and age coefficients in our models could be potentially underestimated.

The limited level of information of self-reported data also holds also true for all other variables in our analyses, especially for the variable ‘self-rated health’.67 Self-rated health status is based on a single item, but it is considered a suitable summary of health status.68 Studies on several representative samples showed that self-rated health ratings can be used as valid measures of health status regardless of different cultures and social conditions69–71 and that they may correspond well to the objective health status.72 73 Caution is needed drawing conclusions from analyses using self-rated health. The same holds true for the variable ‘make ends meet’, since the assessment of self-perceived financial distress compared with income represents an adequate and direct measure of the economic situation of individuals, especially among older individuals.74

Furthermore, SHARE data did not provide information on the reasons for using health services or the quality and adequacy of healthcare services. Consequently, the reported number of GP visits in the last 12 months represents a proxy for ‘realised access’1 only.

Another point that can be discussed is that one out of three domains of SII focused on marital and partnership status and cohabitation. That focus cannot capture the whole variety of non-married or non-partner cohabiting household structures. Potentially, this lack of information is buffered by the other two domains, and especially, by the second domain of SII by including the number of social ties. Nevertheless, the level of social integration could be slightly higher than illustrated by our index. In particular, this could be true for countries with a higher number of ‘non-traditional’ living arrangements.

Finally, and though SHARE strived to combine the indirect and direct approach of social network analysis,64 it does not offer sufficient and longitudinal data on functional and qualitative aspects of SRs.75 The synthesis of the indirect approach (referring on sociodemographic proxies) and the direct approach (linking meaningfulness and importance to social relations) still lacks valuable information about the quality of SRs and perceived support.

Conclusions

Our results demonstrate that different indicators of SRs are not associated with higher or lower frequency of GP visits. The magnitude of the associations is relatively low and most of the investigated associations are statistically insignificant. Nevertheless, the investigation of the two-way and three-way interactions showed a complex, but interesting picture. This study indicates potential inequalities in GP use due to different dimensions and characteristics of SRs, especially considering self-rated health and employment status of older adults.

Since, SRs influence patient’s motives for visits and the patient’s compliance with regard to future visits for treatment, prevention and rehabilitation,76 77 it may be helpful for healthcare providers to assess information on the patient’s ‘social background’. A patient, for instance, characterised by poor health and no emotionally close ties, visits a GP less frequently than his/her counterpart with poor health and closely connected within a social network. Potentially, these differences may produce inequalities in medical care and treatments. In healthcare, it is obligatory, for example, for treatment planning, to decide in line with the patient on the adequacy of treatment and to incorporate the patient’s needs and resources to reach that goal. Therefore, the GP may want to know if a patient is socially integrated or isolated, and may want to evaluate if a patient needs or wants more or less social support. It is important to emphasise that the observed behavioural differences of GP use, within the limits of the SHARE data set, do not implicate inadequacies in GP doctor services, such as overuse or underuse.

Future surveys should aim at assessing functional and quality dimensions of SRs linked to health services use to shed more light on the underlying mechanisms. Finally, to define potential improvements in health systems and to inform health policy makers and health practitioners adequately, health services research needs to integrate information on the patient’s motives for visits and on the levels, quality and outcomes of the treatments.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This paper uses data from SHARE Wave 4 (DOIs: 10.6103/SHARE.w4.500), see Börsch-Supan et al (2013) for methodological details. The SHARE data collection has been primarily funded by the European Commission through FP5 (QLK6-CT-2001-00360), FP6 (SHARE-I3: RII-CT-2006-062193, COMPARE: CIT5-CT-2005-028857, SHARELIFE: CIT4-CT-2006-028812) and FP7 (SHARE-PREP: N°211909, SHARE-LEAP: N°227822, SHARE M4: N°261982). Additional funding from the German Ministry of Education and Research, the US National Institute on Aging (U01_AG09740-13S2, P01_AG005842, P01_AG08291, P30_AG12815, R21_AG025169, Y1-AG-4553-01, IAG_BSR06-11, OGHA_04-064) and from various national funding sources is gratefully acknowledged (see www.share-project.org).

Footnotes

For the sake of readability, we refer to ‘middle-aged and older adults’ or ‘adults 50 years or older’ when we write about ‘older adults’ in this paper.

Contributors: DB, NV, DL and OvdK developed the research question. DB prepared, analysed and interpreted the data, and drafted and finalised the manuscript. DL made an essential contribution to data analyses and interpretation, drafting the manuscript, and critically revised and approved the final manuscript. OvdK and NV substantially contributed to interpreting the data, drafting the manuscript, and critically revised and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? J Health Soc Behav 1995;36:1–10. 10.2307/2137284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fernández-Olano C, Hidalgo JD, Cerdá-Díaz R, et al. . Factors associated with health care utilization by the elderly in a public health care system. Health Policy 2006;75:131–9. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2005.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harris T, Cook DG, Victor CR, et al. . Linking survey data with computerised records to predict consulting by older people. Br J Gen Pract 2004;54:928–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Korten AE, Jacomb PA, Jiao Z, et al. . Predictors of GP service use: a community survey of an elderly Australian sample. Aust N Z J Public Health 1998;22:609–15. 10.1111/j.1467-842X.1998.tb01447.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rennemark M, Holst G, Fagerstrom C, et al. . Factors related to frequent usage of the primary healthcare services in old age: findings from the Swedish national study on aging and care. Health Soc Care Community 2009;17:304–11. 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2008.00829.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lüdecke D, Mnich E, Kofahl C. How do socioeconomic factors influence the amount and intensity of service utilization by family caregivers of elderly dependents? Health care utilization in Germany: Springer, 2014:171–89. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Freid VM, Bernstein AB. Health care utilization among adults aged 55-64 years: how has it changed over the past 10 years? NCHS Data Brief 2010:1-8 Report No.: 32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beaglehole R, Irwin A, Prentice T. The world health report 2003: Shaping the future. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Layton JB. Social relationships and mortality risk: a meta-analytic review. PLoS Med 2010;7:e1000316 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hemingway H, Marmot M. Evidence based cardiology: psychosocial factors in the aetiology and prognosis of coronary heart disease. Systematic review of prospective cohort studies. BMJ 1999;318:1460–7. 10.1136/bmj.318.7196.1460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berkman LF, Leo-Summers L, Horwitz RI. Emotional Support and Survival after Myocardial Infarction. Ann Intern Med 1992;117:1003–9. 10.7326/0003-4819-117-12-1003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Melchior M, Berkman LF, Niedhammer I, et al. . Social relations and self-reported health: a prospective analysis of the French Gazel cohort. Soc Sci Med 2003;56:1817–30. 10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00181-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DiMatteo MR. Social support and patient adherence to medical treatment: a meta-analysis. Health Psychol 2004;23:207–18. 10.1037/0278-6133.23.2.207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murphy BM, Elliott PC, Le Grande MR, et al. . Living alone predicts 30-day hospital readmission after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 2008;15:210–5. 10.1097/HJR.0b013e3282f2dc4e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lett HS, Blumenthal JA, Babyak MA, et al. . Social support and prognosis in patients at increased psychosocial risk recovering from myocardial infarction. Health Psychol 2007;26:418–27. 10.1037/0278-6133.26.4.418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wrzus C, Hänel M, Wagner J, et al. . Social network changes and life events across the life span: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull 2013;139:53–80. 10.1037/a0028601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van Tilburg T. Consequences of men’s retirement for the continuation of work-related personal relationships. Ageing Int 2003;28:345–58. 10.1007/s12126-003-1008-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Atkinson T, Liem R, Liem JH. The social costs of unemployment: implications for social support. J Health Soc Behav 1986;27:317–31. 10.2307/2136947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hand C, McColl MA, Birtwhistle R, et al. . Social isolation in older adults who are frequent users of primary care services. Can Fam Physician 2014;60:e322–e9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li Y, Chi I. Correlates of physician visits among older adults in China: the effects of family support. J Aging Health 2011;23:933–53. 10.1177/0898264311401390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miltiades HB, Wu B. Factors affecting physician visits in Chinese and Chinese immigrant samples. Soc Sci Med 2008;66:704–14. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.10.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Park JM. Equity of access to primary care among older adults in Incheon, South Korea. Asia Pac J Public Health 2012;24:953–60. 10.1177/1010539511409392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stoller EP. Patterns of physician utilization by the elderly: a multivariate analysis. Med Care 1982;20:1080–9. 10.1097/00005650-198211000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ezeamama AE, Elkins J, Simpson C, et al. . Indicators of resilience and healthcare outcomes: findings from the 2010 health and retirement survey. Qual Life Res 2016;25:1007–15. 10.1007/s11136-015-1144-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wolinsky FD, Coe RM. Physician and hospital utilization among noninstitutionalized elderly adults: an analysis of the Health Interview Survey. J Gerontol 1984;39:334–41. 10.1093/geronj/39.3.334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Foreman SE, Yu LC, Barley D, et al. . Use of health services by Chinese elderly in Beijing. Med Care 1998;36:1265–82. 10.1097/00005650-199808000-00014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin N, Ye X, Ensel WM. Social support and depressed mood: a structural analysis. J Health Soc Behav 1999;40:344–344-59. 10.2307/2676330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Orth-Gomér K. Are social relations less health protective in women than in men? Social relations, gender, and cardiovascular health. J Soc Pers Relat 2009;26:63–71. 10.1177/0265407509105522 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.von dem Knesebeck O, Geyer S. Emotional support, education and self-rated health in 22 European countries. BMC Public Health 2007;7:272 10.1186/1471-2458-7-272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rosner TT, Namazi KH, Wykle ML. Physician use among the old-old. Factors affecting variability. Med Care 1988;26:982–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cafferata GL. Marital status, living arrangements, and the use of health services by elderly persons. J Gerontol 1987;42:613–8. 10.1093/geronj/42.6.613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krause N. Stressful life events and physician utilization. J Gerontol 1988;43:S53–S61. 10.1093/geronj/43.2.S53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schafer MH. Discussion networks, physician visits, and non-conventional medicine: probing the relational correlates of health care utilization. Soc Sci Med 2013;87:176–84. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.03.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Almedom AM. Social capital and mental health: an interdisciplinary review of primary evidence. Soc Sci Med 2005;61:943–64. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.12.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Börsch-Supan A. Survey of health, ageing and retirement in Europe (SHARE) Wave 4. Release version: 5.0.0. SHARE-ERIC. Data set, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Börsch-Supan A, Brandt M, Hunkler C, et al. . Data resource profile: the survey of health, ageing and retirement in Europe (SHARE). Int J Epidemiol 2013;42:992–1001. 10.1093/ije/dyt088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Börsch-Supan A, Brandt M, Litwin H, et al. . Active ageing and solidarity between generations in Europe, First results from SHARE after the economic crisis, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Malter F, Börsch-Supan A. SHARE wave 4: innovations & methodology. Munich: MEA, Max Planck Institute for Social Law and Social Policy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 39.SHARE-ERIC. SHARE conditions of Use. 2017. http://www.share-project.org/data-access/share-conditions-of-use.html (updated 22 Feb 2017).

- 40.Malter F, Börsch-Supan A. SHARE compliance profiles – Wave 4. Munich: MEA, Max Planck Institute for Social Law and Social Policy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 41.SHARE-ERIC. Multi-Stage Development of the SHARE questionnaire. http://www.share-project.org/fileadmin/pdf_questionnaire_wave_1/Multi-Stage_Development_of_the_SHARE_questionnaire.pdf.

- 42.: Börsch-Supan A, Jürges H, The survey of health, ageing and retirement in europe – methodology. Mannheim: MEA, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Berkman LF, Melchior M, Chastang JF, et al. . Social integration and mortality: a prospective study of french employees of electricity of france-gas of France: the GAZEL Cohort. Am J Epidemiol 2004;159:167–74. 10.1093/aje/kwh020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cornwell B, Schumm LP, Laumann EO, et al. . Social Networks in the NSHAP Study: rationale, measurement, and preliminary findings. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2009;64 Suppl 1:i47–i55. 10.1093/geronb/gbp042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Van Tilburg TG. Delineation of the social network and differences in network size Living arrangements and social networks of older adults, 1995:83–96. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Burt RS. A note on sociometric order in the general social survey network data. Soc Networks 1986;8:149–89. 10.1016/S0378-8733(86)80002-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Burt RS, Guilarte MG. A note on scaling the general social survey network item response categories. Soc Networks 1986;8:387–96. 10.1016/0378-8733(86)90004-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Long JS, Freese J. Regression models for categorical dependent variables using stata. College Station, Texas: Stata Press, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lumley T, Scott A. Fitting regression models to survey data. Statistical Science 2017;32:265–78. 10.1214/16-STS605 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stata A. Stata survey data reference manual release 13, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lumley T. Analysis of complex survey samples. J Stat Softw 2004;9:1–19. 10.18637/jss.v009.i08 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lumley T. Survey: analysis of complex survey samples. R package version 3, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol 1986;51:1173–82. 10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.R-Core-Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing Vienna. Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Strain LA. Physician visits by the elderly: testing the andersen-newman framework. Canadian Journal of Sociology / Cahiers canadiens de sociologie 1990;15:19 10.2307/3341171 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Levkoff SE, Cleary PD, Wetle T. Differences in determinants of physician use between aged and middle-aged persons. Med Care 1987;25:1148–60. 10.1097/00005650-198712000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wolinsky FD, Coe RM, Miller DK, et al. . Health services utilization among the noninstitutionalized elderly. J Health Soc Behav 1983;24:325–37. 10.2307/2136399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Crespo-Cebada E, Urbanos-Garrido RM. Equity and equality in the use of GP services for elderly people: the Spanish case. Health Policy 2012;104:193–9. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2011.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jordan K, Jinks C, Croft P. A prospective study of the consulting behaviour of older people with knee pain. Br J Gen Pract 2006;56:269–76. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kim ES, Konrath SH. Volunteering is prospectively associated with health care use among older adults. Soc Sci Med 2016;149:122–9. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.11.043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fritel X, Panjo H, Varnoux N, et al. . The individual determinants of care-seeking among middle-aged women reporting urinary incontinence: analysis of a 2273-woman cohort. Neurourol Urodyn 2014;33:1116–22. 10.1002/nau.22461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Arling G. Strain, social support, and distress in old age. J Gerontol 1987;42:107–13. 10.1093/geronj/42.1.107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kawachi I, Berkman LF. Social ties and mental health. J Urban Health 2001;78:458–67. 10.1093/jurban/78.3.458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Litwin H, Stoeckel K, Roll A, et al. . Social network measurement in share wave four SHARE wave 4: innovations & methodology. Munich: MEA, MaxPlanckInstitute for Social Law and Social Policy, 2013:18–37. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gobbens RJ, van Assen MA. Frailty and its prediction of disability and health care utilization: the added value of interviews and physical measures following a self-report questionnaire. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2012;55:369–79. 10.1016/j.archger.2012.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bhandari A, Wagner T. Self-reported utilization of health care services: improving measurement and accuracy. Med Care Res Rev 2006;63:217–35. 10.1177/1077558705285298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jylhä M, Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, et al. . Is self-rated health comparable across cultures and genders? J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 1998;53:S144–S152. 10.1093/geronb/53B.3.S144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Singh-Manoux A, Martikainen P, Ferrie J, et al. . What does self rated health measure? Results from the British Whitehall II and French Gazel cohort studies. J Epidemiol Community Health 2006;60:364–72. 10.1136/jech.2005.039883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Miilunpalo S, Vuori I, Oja P, et al. . Self-rated health status as a health measure: the predictive value of self-reported health status on the use of physician services and on mortality in the working-age population. J Clin Epidemiol 1997;50:517–28. 10.1016/S0895-4356(97)00045-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mossey JM, Shapiro E. Self-rated health: a predictor of mortality among the elderly. Am J Public Health 1982;72:800–8. 10.2105/AJPH.72.8.800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.DeSalvo KB, Bloser N, Reynolds K, et al. . Mortality prediction with a single general self-rated health question. A meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med 2006;21:267–75. 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.00291.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hunt SM, McKenna SP, McEwen J, et al. . A quantitative approach to perceived health status: a validation study. J Epidemiol Community Health 1980;34:281–6. 10.1136/jech.34.4.281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Johnson RJ, Wolinsky FD. The structure of health status among older adults: disease, disability, functional limitation, and perceived health. J Health Soc Behav 1993;34:105–21. 10.2307/2137238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Börsch-Supan A, Brugiavini A, Jürges H, et al. . First results from the survey of health, ageing and retirement in Europe (2004-2007). Starting the longitudinal dimension Mannheim: MEA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pescosolido B. Social connectedness in health, morbidity and mortality, and health care - the contributions, limits and further potential of health and retirement study. Forum Health Econ Policy 2011;14 10.2202/1558-9544.1264 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cornwell EY, Waite LJ. Social network resources and management of hypertension. J Health Soc Behav 2012;53:215–31. 10.1177/0022146512446832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zhang AY, Siminoff LA. The role of the family in treatment decision making by patients with cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum 2003;30:1022–8. 10.1188/03.ONF.1022-1028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-018854supp001.pdf (62.7KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-018854supp002.pdf (54.4KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-018854supp003.pdf (56.5KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-018854supp004.pdf (80.7KB, pdf)