Abstract

Objective

After cross-cultural adaption for the German translation of the Ankle-Hindfoot Scale of the American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society (AOFAS-AHS) and agreement analysis with the Foot Function Index (FFI-D), the following gait analysis study using the Oxford Foot Model (OFM) was carried out to show which of the two scores better correlates with objective gait dysfunction.

Design and participants

Results of the AOFAS-AHS and FFI-D, as well as data from three-dimensional gait analysis were collected from 20 patients with mild to severe ankle and hindfoot pathologies.

Kinematic and kinetic gait data were correlated with the results of the total AOFAS scale and FFI-D as well as the results of those items representing hindfoot function in the AOFAS-AHS assessment. With respect to the foot disorders in our patients (osteoarthritis and prearthritic conditions), we correlated the total range of motion (ROM) in the ankle and subtalar joints as identified by the OFM with values identified during clinical examination ‘translated’ into score values. Furthermore, reduced walking speed, reduced step length and reduced maximum ankle power generation during push-off were taken into account and correlated to gait abnormalities described in the scores. An analysis of correlations with CIs between the FFI-D and the AOFAS-AHS items and the gait parameters was performed by means of the Jonckheere-Terpstra test; furthermore, exploratory factor analysis was applied to identify common information structures and thereby redundancy in the FFI-D and the AOFAS-AHS items.

Results

Objective findings for hindfoot disorders, namely a reduced ROM, in the ankle and subtalar joints, respectively, as well as reduced ankle power generation during push-off, showed a better correlation with the AOFAS-AHS total score—as well as AOFAS-AHS items representing ROM in the ankle, subtalar joints and gait function—compared with the FFI-D score.

Factor analysis, however, could not identify FFI-D items consistently related to these three indicator parameters (pain, disability and function) found in the AOFAS-AHS. Furthermore, factor analysis did not support stratification of the FFI-D into two subscales.

Conclusions

The AOFAS-AHS showed a good agreement with objective gait parameters and is therefore better suited to evaluate disability and functional limitations of patients suffering from foot and ankle pathologies compared with the FFI-D.

Keywords: gait analysis, foot and ankle surgery, questionnaires, scores, patient reported outcome measures

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Strengths of this study are the objective gait parameters,

Strengths of this study are as well the extensive statistical procedures.

Limitations of this study are the inhomogeneity of the group and the limited number of patients. When focusing on a certain group of foot disorders, a more homogeneous group should be examined. In order to develop a new score dealing with different kinds of foot disorders using gait analysis, a larger group should be taken into account.

Introduction

A variety of questionnaires are available for assessing pain, disability and functional limitations of patients suffering from foot and ankle pathologies. The Ankle-Hindfoot Scale of the American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society (AOFAS-AHS) is one of them and is commonly used to estimate and describe the outcome of conservative or surgical treatment of ankle or hindfoot pathologies.1 This score is widely used despite the legitimate criticism of its theoretical mathematical weaknesses, such as over-representation of the pain question and the limited number of feature expressions, leading to a floor and ceiling effect.2 3 In contrast, several publications have shown a high level of responsiveness and acceptable criterion validity for the AOFAS-AHS,4 as well as a satisfactory degree of reliability for the subjective component of the AOFAS scale,5 which justifies its application. In addition, the Foot Function Index (FFI) is also commonly used in the clinical setting.6–9

Cross-cultural adaption of the AOFAS-AHS in its German translation and agreement analysis with the FFI-D by Naal et al 10 were previously performed and published.11 12 The agreement analysis showed that the scores are not interchangeable, but rather complementary.12 However, these self-reported questionnaires assess patient perception and are not necessarily indicative of actual disabilities. Therefore, it is important that research considers other methods of assessing functionality. Gait analysis has widely been accepted as an objective measure of physical function,13 allowing researchers and clinicians to better understand the biomechanics of gait. In particular, the Oxford Foot Model (OFM)14 is a multisegment kinematic model that can be used to quantify the functionality of the foot complex during gait in patients with different pathologies.15–17 In patients with osteoarthritis and pre-osteoarthritis disorders in the ankle and subtalar joints, reduced walking speed, reduced step length, reduced range of motion (ROM) within different sections of the foot and ankle joint and reduced ankle power generation during push-off have been shown.18–21

Since agreement analysis12 did not determine which of the two scores is better suited to reflect function in patients with ankle and hindfoot disorders, the aim of the present study was to determine the association between physical foot dysfunction using the OFM and perceived disability in patients with mild to severe ankle and hindfoot pathologies. Higher correlation was expected for the FFI-D with respect to its rather elaborate scoring system as compared with the AOFAS-AHS scale system. In addition, exploratory factor analysis was applied to identify common information structures and redundancy contained in the FFI-D and the AOFAS-AHS items.

Methods and materials

Subjects

AOFAS-AHS and FFI-D results were consecutively collected from 20 patients with mild to severe ankle and hindfoot pathologies (10 female and 10 male patients) and a median age of 45 (IQR 35–54) years. Body mass index was 27.8 (24.7–31.6) kg/cm2 in median. We deliberately chose a heterogeneous group of patients to reflect the wide range of patients who were evaluated using the AOFAS-AHS. The 20 patients suffered from pathologies such as primary or post-traumatic osteoarthritis (10/20), osteochondral lesions/subchondral cysts (5/20), chondromatosis/corpora libra (2/20) or osteoarthritis due to haemophilia (3/20). Exclusion criteria included neuromuscular dysfunction (eg, Parkinson’s disease, stroke, epilepsy and Alzheimer’s disease), a leg length discrepancy of more than 1 cm and chronic joint infection. All selected patients were recruited during a polyclinic consultation by an experienced foot and ankle surgeon and demonstrated pain, stiffness or reduced ROM in different sections of the foot and ankle joint. They all showed clearly osteoarthritis or prearthritic conditions in X-rays as well as MRI scans. All patients underwent three-dimensional gait analysis on the same day the two questionnaires AOFAS-AHS and FFI-D were applied.

The study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Accordingly, written informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to participation in the study.

Questionnaires

The FFI-D questionnaire is based on a 10-point scale for each item and enables overall continuous scoring by means of an equally weighted normalising evaluation system and providing two subscales including 8 items for pain and 10 items for disability, respectively. The AOFAS-AHS includes nine items (five to be answered by patients and four to be answered by the physician) with two to four possible responses and an asymmetric assignment of score points. The AOFAS-AHS over-represents the pain item with 40 of the maximum 100 score points assigned to this item alone.

Gait analysis methods

Three-dimensional gait analysis was performed using a 200 Hz, eight-camera motion capture system (VICON Motion Systems, Oxford, UK) in combination with a 1000 Hz AMTI force plate (Advanced Mechanical Technology, Watertown, Massachusetts, USA) to detect gait cycle events and to calculate ankle power generation during the push-off phase. Reflective markers were placed over prominent anatomical landmarks along the lower extremity, as well as the ankle and foot complex according to the multisegment OFM.14 22 The OFM allows for a differentiated analysis of movement within different sections of the foot and ankle joint. Repeatability of the OFM has been demonstrated for healthy children and adults18 23 24 and has also been applied in patients with foot pathologies/disorders16 22 25.

Kinematic and data that represent mobility in the ankle and subtalar joints (eg, the ROM plantarflexion to dorsiflexion for the hindfoot vs tibia as well as inversion to eversion or forefoot vs hindfoot adduction to abduction) and that are relevant for patients with osteoarthritis were collected from barefoot participants during level walking at a self-selected speed. In cases with bilateral pathology, the more severely affected side was analysed. After each acquisition session, 3D marker trajectories were reconstructed and missing frames were handled with a fill-gap procedure. The data were smoothed with a Woltring filter and using spline smoothing.26 Average values from three trials were selected based on good quality of marker trajectories and ground reaction forces.

Statistical analysis

A sample size calculation was performed based on the fact that an AOFAS score of 80–100 points is expected for healthy people, while in patients with relevant foot and ankle disorders a score of 30–35 points is expected. The power was assumed to be 80%. A group of 20 patients was calculated as suitable.

In a first step, basic spatiotemporal gait parameters (ie, walking speed, cadence, step length, stride length, step width) as well as discrete kinematic and kinetic gait data were correlated with the total scores for the AOFAS-AHS (range 0–100 points) and the FFI-D. The FFI-D scale was transformed to the range 0–100 points with 100 points indicating optimum rating in all items to make the scores directly comparable to those derived from the AOFAS-AHS. Both overall scores were handled as continuous endpoints, that is, methods for continuous data evaluation were applied. This means that score descriptions were based on medians and quartiles (graphic description on non-parametric box whisker plots, accordingly) with regard to the moderate sample size. Bivariate correlations between gait parameters and the total FFI-D and AOFAS-AHS scores were estimated by means of the Spearman coefficient and its asymptotic 95% CI. For the sake of aggregation and interpretation of the various bivariate correlation profiles a previously established categorisation of correlation ranges based on the Spearman point estimates was adopted27 28: correlations were classified ‘low’ for Spearman coefficients less than 0.30, as ‘medium’ for coefficients between 0.30 and 0.65 and otherwise as high.

For further correlation analyses, AOFAS-AHS items were taken into account that represent the function of the subtalar and ankle joints, and were related to the corresponding gait analysis parameters representing the function of the respective joints. The respective bivariate associations were described by means of gait parameter distribution (medians and quartiles) stratified for the respective AOFAS item scale levels. Furthermore, Jonckheere-Terpstra test was applied to test for trends in the gait parameters levels alongside the respective AOFAS item scale levels. The results of these trend tests were summarised by means of P values. In accordance with the exploratory character of this evaluation, the latter were not formally adjusted for multiplicity, but rather considered as indicators of local statistical significance in the case of P≤0.05.

To determine those FFI-D items representing the ROM in the ankle and the subtalar joints as well as gait function—note that these can be derived from the AOFAS items, but not from the FFI-D assessment—exploratory factor analysis for the total set of the 9 AOFAS-AHS and the 18 FFI-D items was performed. In the case of several FFI-D items being aggregated with the AOFAS item(s) of interest, these FFI-D items could be considered as ROM related. Since the AOFAS-AHS individual items are more or less categorical, whereas the FFI-D parameters should be treated as continuous, both score systems’ items were binarised for simultaneous use in factor analysis by means of the following criteria: the AOFAS-AHS item dealing with pain was defined to indicate a ‘negative response’ for a score of 20 points or less. Accordingly, a score representing pathological findings (0–4 points) in one of the remaining AOFAS-AHS items was defined as a ‘negative response’. For the FFI-D, results of five or more points were regarded as a ‘negative response’ (note the scaling direction of the FFI-D items). The total set of 9 binarised AOFAS-AHS items and of 18 binarised FFI-D items was then analysed by means of exploratory factor analysis, where factors were identified by means of principle component analysis and application of the varimax criterion (75% variance to be explained by identified factors).

Statistical and graphic analyses were performed using SPSS for Windows V.21.0. (IBM Corporation].

Results

Gait analysis

Only moderate correlation coefficients (r=0.51–0.64) could be found between the total AOFAS-AHS/total FFI-D score and objective gait parameters as shown in table 1. With moderate correlation coefficients between the AOFAS-AHS total score and six gait parameters representing mobility in the ankle joint, two representing the ROM in the subtalar joint, as well as ankle maximum power generation during the push-off phase (table 1), the AOFAS-AHS showed slightly more and higher correlation coefficients with the gait parameters than the FFI-D total score. Regarding the FFI-D, only six moderate correlations could be found between the overall score and gait parameters representing mobility in the ankle (one parameter) and subtalar joints (five parameters, table 1).

Table 1.

Spearman correlation coefficients with 95% CIs between the AOFAS-AHS total score as well as the FFI-D total score, respectively, and selected gait parameters representing mobility in the ankle (six parameters) and the subtalar joint (five parameters) as well as the ankle osteoarthritis indicator parameter ankle maximum power generation during stance (W/kg), respectively

| Parameter | AOFAS-AHS total score r (95% CI) |

FFI-D total score r (95% CI) |

| Hindfoot versus tibia maximum dorsiflexion during stance (°) | 0.51 (−0.15 to 0.83) | 0.16 (−0.40 to 0.66) |

| Hindfoot versus tibia ROM (plantarflexion/dorsiflexion) during gait cycle (°) | 0.53 (0.18 to 0.75) | 0.47 (0.00 to 0.78) |

| Hindfoot versus tibia ROM (inversion/eversion) during gait cycle (°) | 0.55 (0.24 to 0.78) | 0.55 (0.02 to 0.85) |

| Hindfoot versus tibia ROM (internal/external rotation) during gait cycle (°) | 0.41 (−0.06 to 0.78) | 0.51 (0.03 to 0.83) |

| Forefoot versus hindfoot maximum dorsiflexion during stance (°) | −0.57 (−0.83 to 0.07) | −0.36 (−0.72 to 0.3) |

| Forefoot versus hindfoot maximum plantarflexion during push-off phase (°) | −0.64 (−0.87 to −0.25) | −0.26 (−0.76 to 0.26) |

| Forefoot versus hindfoot ROM (adduction/abduction) during gait cycle (°) | 0.63 (0.28 to 0.86) | 0.57 (0.12 to 0.84) |

| Forefoot versus hindfoot ROM (supination/pronation) during gait cycle (°) | 0.45 (0.14 to 0.72) | 0.52 (0.10 to 0.80) |

| Forefoot versus tibia ROM (adduction/abduction) during gait cycle (°) | 0.45 (0.05 to 0.77) | 0.57 (0.21 to 0.79) |

| Forefoot versus tibia maximum plantarflexion during push-off phase (°) | −0.61 (−0.88 to −0.29) | −0.55 (−0.84 to −0.09) |

| Forefoot versus tibia ROM (plantarflexion/dorsiflexion) during gait cycle (°) | 0.57 (0.13 to 0.87) | 0.38 (−0.10 to 0.78) |

| Ankle maximum power generation during push-off phase (W/kg) | 0.55 (0.18 to 0.84) | 0.34 (−0.11 to 0.72) |

Significant correlations (>0.5/<−0.5) are shown in bold.

AOFAS-AHS, Ankle-Hindfoot Scale of the American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society; FFI-D, Foot Function Index; ROM, range of motion.

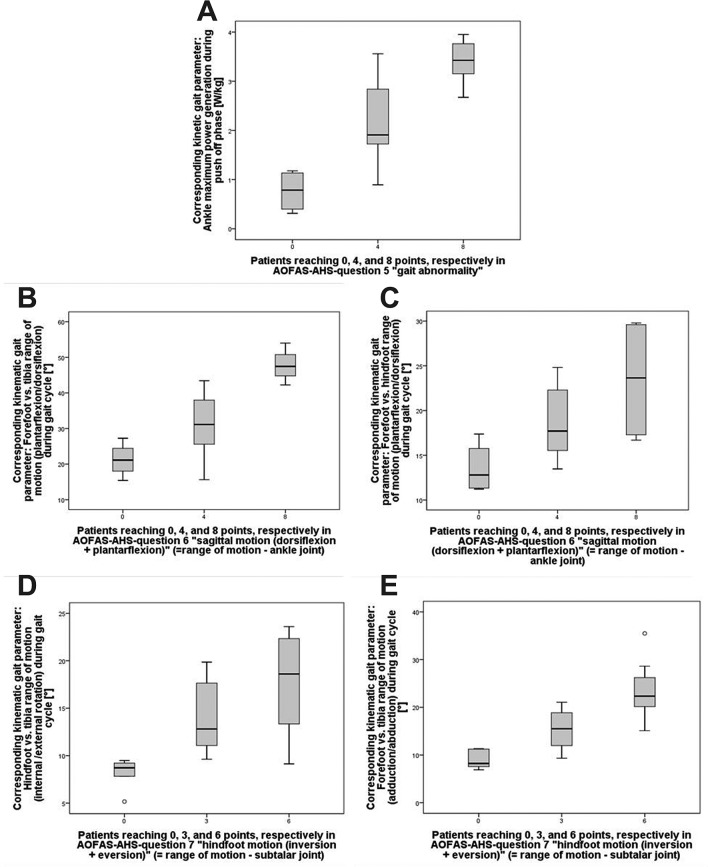

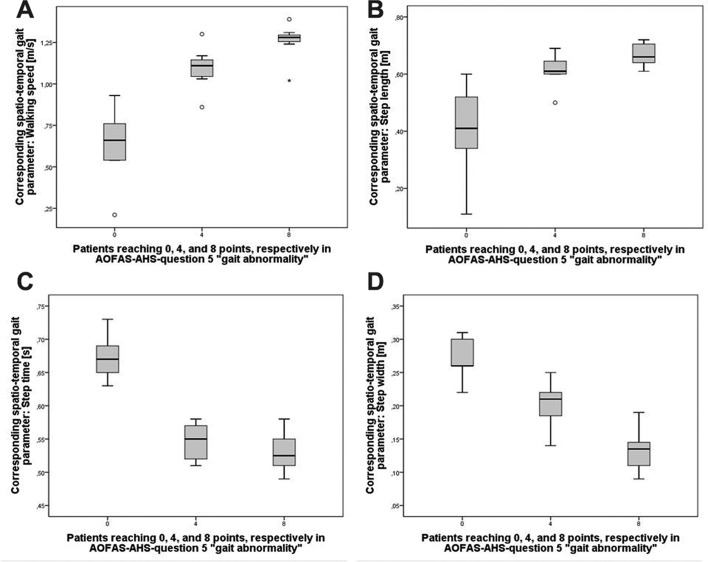

In addition, we focused on the individual items of the AOFAS-AHS that represent gait function and passive ROM (AOFAS-AHS items 5–7). The AOFAS-AHS items representing passive ROM in the ankle joint complex and the corresponding gait parameters representing the total ROM during the gait cycle in the ankle joint and the subtalar joints, respectively, as well as spatiotemporal gait parameters, showed encouraging association (figures 1 and 2; all presented trends were found locally significant), as also demonstrated in terms of the Jonckheere-Terpstra test with a significance at the 5% level between the three groups (equals to three different items for the answer) indicating monotonic association. As a result of extensive exploratory analysis those gait parameters were taken into account, which best represented mobility (figure 1) and gait function (figure 2) in the respective joints.

Figure 1.

Non-parametric box plots for an association analysis between Ankle-Hindfoot Scale of the American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society (AOFAS-AHS) items 5–7 and respective content-corresponding gait parameters. Box plot horizontals indicate medians and quartiles, verticals indicate minimum and maximum observations, circles indicate statistical outliers with a deviation of at least 1.5× IQR from the respective median. AOFAS-AHS item 5 (gait abnormality) represents a normal gait or slight gait abnormality with 8 points, an obvious gait abnormality (walking/running is possible but irregular) with 4 points and a considerable gait abnormality with 0 points. AOFAS-AHS item 6 (sagittal motion, flexion plus extension) represents a normal or mild restriction (30° or more) with 8 points, a moderate restriction (15°–29°) with 4 points and a severe restriction (less than 15°) with 0 points. AOFAS-AHS item 7 (hindfoot motion, inversion plus eversion) represents a normal or mild restriction (75%–100% normal) with 6 points, a moderate restriction (25%–74% normal) with 3 points and a severe restriction (less than 25% normal) with 0 points. (A) Box plots for the maximum ankle power generation during push-off stratified for AOFAS-AHS points achieved by 20 patients. (B) Box plots for the total range of motion during gait cycle in dorsiflexion to plantarflexion of the forefoot versus the tibia angle stratified for AOFAS-AHS points achieved by 20 patients. (C) Box plots for the total range of motion during gait cycle in dorsiflexion to plantarflexion of the forefoot versus the hindfoot angle stratified for AOFAS-AHS points achieved by 20 patients. (D) Box plots for the total range of motion during gait cycle in internal to external rotation of the hindfoot versus the tibia angle stratified for AOFAS-AHS points achieved by 20 patients. (E) Box plots for the total range of motion during gait cycle in adduction to abduction of the forefoot versus the tibia angle stratified for AOFAS-AHS points achieved by 20 patients.

Figure 2.

Non-parametric box plots for an association analysis between Ankle-Hindfoot Scale of the American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society (AOFAS-AHS) item 5 and corresponding spatiotemporal gait parameters with regard to content. Box plot horizontals indicate medians and quartiles, verticals indicate minimum and maximum observations, circles and asterisks indicate statistical outliers with a deviation of 1.5 and 2.0 x IQR from the respective median. AOFAS-AHS item 5 (gait abnormality) represents normal gait or a slight gait abnormality with 8 points, an obvious gait abnormality (walking/running is possible but irregular) with 4 points and a considerable gait abnormality with 0 points. (A) Box plots for walking speed stratified for AOFAS-AHS points achieved by 20 patients. (B) Box plots for step length stratified for AOFAS-AHS points achieved by 20 patients. (C) Box plots for step time stratified for AOFAS-AHS points achieved by 20 patients. (D) Box plots for step width stratified for AOFAS-AHS points achieved by 20 patients.

Factor analysis

Factor analysis based on the binarised individual AOFAS-AHS and FFI-D items proposed three factors arising out of the joint information pattern, but could not reveal any FFI-D items to represent either mobility in the ankle and subtalar joints or gait function (table 2). Furthermore, although the FFI-D is divided into the two subscales ‘pain’ and ‘disability’7 10 by its authors, this subdivision could not be reproduced in the factor analysis patterns. Only three items of the FFI-D pain subscale showed an involvement in factor 2 (representing ‘pain and disability’). In addition, only one item from the pain subscale and one item from the disability subscale were involved with factor 3 (representing ‘mobility and gait function’), while all remaining questions from the subscales were aggregated into factor 1. The authors could not construct a generic term for this predominant factor 1, as it encompasses a wide variety of items, which could hardly be assigned to one common category (table 2). In contrast, the AOFAS-AHS items showed either a high involvement with factor 2 (representing ‘pain and disability’) or with factor 3 (representing ‘mobility and gait function’).

Table 2.

Factor analysis results for the respective binarised 9 items of the AOFAS-AHS and the binarised 18 items of the FFI-D: rotated factor weights for the 9+18 items after identification of three joint factors by means of the variance maximisation criterion

| (Binarised) score items | Factor and factor weight | ||

| 1 | 2 ‘Pain and disability’ |

3 ‘Mobility and gait function’ |

|

| AOFAS-AHS ‘pain’ | 0.810 | ||

| AOFAS-AHS ‘activity restriction’ | 0.807 | ||

| AOFAS-AHS ‘walking distance’ | 0.597 | ||

| AOFAS-AHS ‘walking surfaces’ | 0.780 | ||

| AOFAS-AHS ‘gait abnormality’ | 0.747 | ||

| AOFAS-AHS ‘sagittal motion’ | 0.747 | ||

| AOFAS-AHS ‘hindfoot motion’ | 0.780 | ||

| AOFAS-AHS ‘ankle-hindfoot stability’ | 0.480 | ||

| AOFAS-AHS ‘alignment’ | 0.508 | ||

| FFI-D pain ‘worst pain’ | 0.792 | ||

| FFI-D pain ‘pain in the morning’ | 0.446 | ||

| FFI-D pain ‘pain while walking barefoot’ | 0.741 | ||

| FFI-D pain ‘pain while standing barefoot’ | 0.620 | ||

| FFI-D pain ‘pain while walking with shoes’ | 0.741 | ||

| FFI-D pain ‘pain while standing with shoes’ | 0.704 | ||

| FFI-D pain ‘pain at the end of the day’ | 0.824 | ||

| FFI-D pain ‘pain during the night’ | 0.477 | ||

| FFI-D disability ‘problems while walking outside’ | 0.656 | ||

| FFI-D disability ‘problems while walking on uneven ground’ | 0.846 | ||

| FFI-D disability ‘problems while walking distances ≥1 km’ | 0.846 | ||

| FFI-D disability ‘problems while walking up the stairs’ | 0.690 | ||

| FFI-D disability ‘problems while walking down the stairs’ | 0.767 | ||

| FFI-D disability ‘problems while walking on tiptoes’ | 0.767 | ||

| FFI-D disability ‘problems while standing up from a chair’ | 0.442 | ||

| FFI-D disability ‘problems while walking fast or during running’ | 0.846 | ||

| FFI-D disability ‘problems during leisure activities or sports’ | 0.846 | ||

| FFI-D disability ‘problems while wearing special shoes (high heels, sandals etc)’ | |||

Factor weights <0.500 have been omitted to emphasise the rotation-based aggregation of the 9+18 items into three factors, a posteriori declared representing ‘pain and disability’ (factor 2) and ‘mobility and gait function’ (factor 3), respectively.

AOFAS-AHS, Ankle-Hindfoot Scale of the American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society; FFI-D, Foot Function Index.

Discussion

Since both scores are still used throughout the world to evaluate treatment outcomes of foot and ankle disorders and a validated German translation of the AOFAS-AHS did not yet exist, we carried out a validation study for the German language version of the AOFAS-AHS.12 The present study was the final step in this procedure. The main goal was to determine the association between objective foot function using the OFM and perceived disability in patients with mild to severe ankle and hindfoot pathologies.

Our expectation that—due to its better evaluation methodology and the two respective subscales—the FFI-D, in comparison with the AOFAS-AHS, is better suited to assess the functionality of the foot could not be supported. The comparison of the Spearman correlations between the overall results of both scores and functionality during gait indicates a slightly better suitability of the AOFAS-AHS. In particular, the analysis of the respective functional pattern under consideration of the individual items from the AOFAS-AHS was able to show good agreement with objective parameters from gait analysis. Additionally, the moderate positive correlation between the AOFAS-AHS and ankle power generation during push-off indicates that the AOFAS-AHS is well suited to evaluate limitations in foot function during gait.

Although the FFI-D is divided into two subscales, this could not be confirmed by factor analysis. The opposite was found for the AOFAS-AHS, which represents pain and ability issues on the one hand and questions dealing with hindfoot and ankle function on the other hand. This was shown in the factor analysis for the transformed individual questions, even if this was not postulated by its developers themselves.1

The mathematical weaknesses of the AOFAS-AHS—especially the over-representation of the pain question and the limited number of feature expressions, leading to a floor and ceiling effect—are undeniable.2 Nevertheless, the items in the AOFAS-AHS give a good representation of ankle and hindfoot disorders, as shown by the Spearman correlations with gait function, ROM in the ankle and subtalar joints, as well as by the Jonckheere-Terpstra test. Reduced ankle power generation during push-off is discussed as a possible indicator for ankle arthritis.17 19 21 Since reduced ankle power generation during push-off showed a significant correlation with the AOFAS-AHS total score, this suggests that the AOFAS-AHS total score might be an indicator of ankle osteoarthritis.

Due to its mathematical weaknesses, the AOFAS-AHS should be applied with care, even if its individual questions show a good representation of pain, disability and function. These items can be used, but should be combined with better methods for scoring and interpreting the results. In contrast, the FFI-D did not show the same clear correlations for these three items (pain, disability and function). In addition, the FFI-D did not demonstrate any clear items representing gait function or ROM in the ankle and subtalar joints in the factor analysis. Therefore, it did not make any sense to compare the results of individual questions to corresponding gait parameters. As a consequence, the application of the FFI-D as a score to evaluate disability and functional limitations of patients suffering from foot and ankle pathologies should be critically discussed.

Our findings show that the use of gait analysis in combination with theoretical mathematical considerations for the evaluation of scores will make a valuable contribution to the development and evaluation of survey instruments and patient-reported outcome questionnaires in clinical research. The best consequence would be to develop a new score with items derived from objective measurements such as gait analysis including mature biometrical means for scoring and evaluating results.

Limitations

Limitations of this study are the inhomogeneity of the group and the limited number of patients. Nevertheless, we deliberately choose a heterogeneous group of patients to reflect the wide range of patients who were evaluated using the AOFAS-AHS. For focusing on a certain group of foot disorders, a more homogeneous group should be examined. In order to develop a new score dealing with different kinds of foot disorders using gait analysis, a bigger group should be taken into account.

Conclusion

The AOFAS-AHS showed a good agreement with objective gait parameters and is therefore better suited to evaluate disability and functional limitations of patients suffering from foot and ankle pathologies compared with the FFI-D.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The gait analysis study was the subject of the doctoral thesis of coauthor KAH.

Footnotes

Contributors: The authors declare the following contribution of authorship: TK: substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work, drafting the article, final approval of the version published. FS, KAH: acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data from gait laboratory, revising it critically for important intellectual content and final approval of the version published. FK, MA, MHB: acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data from gait laboratory, revising it critically for important intellectual content. AM: provided the gait laboratory for carrying out the study (owner of gait laboratory), made substantial contributions to data interpretation. KS: acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data with respect to statistics (Jonckheere-Terpstra test, exploratory factor analysis), revising it critically for important intellectual content. SL: substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work, revising it critically for important intellectual content.

Funding: In order to conduct this study, the ethics committee required participants to be insured for the procedure due to the fact that the gait laboratory examination was done for this study only. This insurance was funded through a research grant from the German Foot and Ankle Society.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The approval of the local independent Ethics Committee (Ruhr University Bochum ICE; vote reference number 4126-11) was obtained in 2011.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. Kitaoka HB, Alexander IJ, Adelaar RS, et al. . Clinical rating systems for the ankle-hindfoot, midfoot, hallux, and lesser toes. Foot Ankle Int 1994;15:349–53. 10.1177/107110079401500701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Guyton GP. Theoretical limitations of the AOFAS scoring systems: an analysis using Monte Carlo modeling. Foot Ankle Int 2001;22:779–87. 10.1177/107110070102201003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. SooHoo NF, Shuler M, Fleming LL. Evaluation of the validity of the AOFAS Clinical Rating Systems by correlation to the SF-36. Foot Ankle Int 2003;24:50–5. 10.1177/107110070302400108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Madeley NJ, Wing KJ, Topliss C, et al. . Responsiveness and validity of the SF-36, Ankle Osteoarthritis Scale, AOFAS Ankle Hindfoot Score, and Foot Function Index in end stage ankle arthritis. Foot Ankle Int 2012;33:57–63. 10.3113/FAI.2012.0057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ibrahim T, Beiri A, Azzabi M, et al. . Reliability and validity of the subjective component of the American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society clinical rating scales. J Foot Ankle Surg 2007;46:65–74. 10.1053/j.jfas.2006.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Agel J, Beskin JL, Brage M, et al. . Reliability of the Foot Function Index:: A report of the AOFAS Outcomes Committee.. Foot Ankle Int 2005;26:962–7. 10.1177/107110070502601112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Budiman-Mak E, Conrad KJ, Roach KE. The Foot Function Index: a measure of foot pain and disability. J Clin Epidemiol 1991;44:561–70. 10.1016/0895-4356(91)90220-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Budiman-Mak E, Conrad K, Stuck R, et al. . Theoretical model and Rasch analysis to develop a revised Foot Function Index. Foot Ankle Int 2006;27:519–27. 10.1177/107110070602700707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kuyvenhoven MM, Gorter KJ, Zuithoff P, et al. . The foot function index with verbal rating scales (FFI-5pt): A clinimetric evaluation and comparison with the original FFI. J Rheumatol 2002;29:1023–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Naal FD, Impellizzeri FM, Huber M, et al. . Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the Foot Function Index for use in German-speaking patients with foot complaints. Foot Ankle Int 2008;29:1222–31. 10.3113/FAI.2008.1222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kostuj T, Schaper K, Baums MH, et al. . Eine Validierung des AOFAS-Ankle-Hindfoot-Scale für den deutschen Sprachraum. Original Research Article. Fuß & Sprunggelenk 2014;12:107–12. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kostuj T, Krummenauer F, Schaper K, et al. . Analysis of agreement between the German translation of the American Foot and Ankle Society’s Ankle and Hindfoot Scale (AOFAS-AHS) and the Foot Function Index in its validated German translation by Naal et al. (FFI-D). Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2014;134:1205–10. 10.1007/s00402-014-2046-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Baker R. Gait analysis methods in rehabilitation. J Neuroeng Rehabil 2006;3:4 10.1186/1743-0003-3-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Stebbins J, Harrington M, Thompson N, et al. . Repeatability of a model for measuring multi-segment foot kinematics in children. Gait Posture 2006;23:401–10. 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2005.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Stebbins J, Harrington M, Thompson N, et al. . Gait compensations caused by foot deformity in cerebral palsy. Gait Posture 2010;32:226–30. 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2010.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Levinger P, Murley GS, Barton CJ, et al. . A comparison of foot kinematics in people with normal- and flat-arched feet using the Oxford Foot Model. Gait Posture 2010;32:519–23. 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2010.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nüesch C, Valderrabano V, Huber C, et al. . Gait patterns of asymmetric ankle osteoarthritis patients. Clin Biomech 2012;27:613–8. 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2011.12.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Barton T, Lintz F, Winson I. Biomechanical changes associated with the osteoarthritic, arthrodesed, and prosthetic ankle joint. Foot Ankle Surg 2011;17:52–7. 10.1016/j.fas.2011.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Valderrabano V, Nigg BM, von Tscharner V, et al. . Gait analysis in ankle osteoarthritis and total ankle replacement. Clin Biomech 2007;22:894–904. 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2007.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Piriou P, Culpan P, Mullins M, et al. . Ankle replacement versus arthrodesis: a comparative gait analysis study. Foot Ankle Int 2008;29:3–9. 10.3113/FAI.2008.0003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Segal AD, Shofer J, Hahn ME, et al. . Functional limitations associated with end-stage ankle arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2012;94:777–83. 10.2106/JBJS.K.01177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Carson MC, Harrington ME, Thompson N, et al. . Kinematic analysis of a multi-segment foot model for research and clinical applications: a repeatability analysis. J Biomech 2001;34:1299–307. 10.1016/S0021-9290(01)00101-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Curtis DJ, Bencke J, Stebbins JA, et al. . Intra-rater repeatability of the Oxford foot model in healthy children in different stages of the foot roll over process during gait. Gait Posture 2009;30:118–21. 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2009.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wright CJ, Arnold BL, Coffey TG, et al. . Repeatability of the modified Oxford foot model during gait in healthy adults. Gait Posture 2011;33:108–12. 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2010.10.084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mindler GT, Kranzl A, Lipkowski CA, et al. . Results of gait analysis including the Oxford foot model in children with clubfoot treated with the Ponseti method. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2014;96:1593–9. 10.2106/JBJS.M.01603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Woltring HJ. Representation and calculation of 3-D joint movement. Hum Mov Sci 1991;10:603–16. 10.1016/0167-9457(91)90048-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioural sciences: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Philadelphia, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gaus W, Rainer M. 9 Korrelationen und einfache, lineare Regression, in: Medizinische Statistik – angewandte Biometrie für Ärzte und Gesundheitsberufe 1st edn: Schattauer Stuttgart, 2014:172. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.