Abstract

Introduction

Transdisciplinary teams are increasingly regarded as integral to conducting effective research. Similarly, knowledge translation is often seen as a solution to improving the relevance and benefits of health research. Yet, whether, how, for whom and under which circumstances transdisciplinary research influences knowledge translation is undertheorised, which limits its potential impact. The proposed research aims to identify the contexts and mechanisms by which transdisciplinary research contributes to developing shared understandings and behaviours of knowledge translation between team members.

Methods and analysis

Using a longitudinal case-study design approach to realist evaluation, we outline a study protocol examining whether, how, if and for whom transdisciplinary collaboration can impact knowledge translation understandings and behaviours within a 5-year transdisciplinary Centre of Research Excellence. Data are being collected between February 2017 and December 2020 over four rounds of theory development, refinement and testing using interviews, observation, document review and visual elicitation as data sources.

Ethics and dissemination

The Health Research Ethics Committee of the University of Adelaide approved this study. Findings will be communicated with team members at scheduled intervals throughout the study verbally and by means of creative reflective approaches (eg, arts elicitation, journalling). This research will be used to help support optimal team functioning by identifying strategies to support knowledge sharing and communication within and beyond the team to facilitate attainment of research objectives. Academic dissemination will occur through publication and presentations.

Keywords: knowledge translation, frailty, transdisciplinary, collaboration, realist evaluation

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This evaluation will be one of the first internationally to examine if, how, for whom and why transdisciplinary research collaboration impacts knowledge translation understandings and behaviours.

This research will provide insight into understandings of knowledge translation within a transdisciplinary team, thereby identifying (developmentally) misaligned understandings of knowledge translation processes and activities, and concurrent strategies for supporting shared understandings.

Although realist evaluation can provide insights into which conditions impact which outcomes (and how), no single study cannot produce universally transferable findings.

Despite its strengths, participant observation can limit both the depth of data provided to the researcher and the extent of confidentiality afforded to participating members given the researchers position.

Introduction

Transdisciplinary research and knowledge translation are common terms in health research, but what do they have in common? Both terms are increasingly used in the conduct of research.1–4 Both terms represent complex social processes. Both terms are frequently misunderstood and misapplied. Based on growing attention received from funding bodies and research sectors, both terms are recognised for their potential for doing things ‘better’: better research, better impact and better investment. Although the relationship between transdisciplinary collaboration and knowledge translation is often assumed or implied in research, funding and policy documents, this does little to explicate the complex relationship between the concepts. Given the growing emphasis on transdisciplinary paradigms, research is needed to develop stronger theoretical explanations of if, how, why, for whom and under what circumstances transdisciplinary collaboration influences knowledge translation. Such an understanding can be generated through realist evaluation and could be used to inform collaborative teams with the greatest potentials for impact.

Maximising the benefits of collaboration in health research requires attention to internal group activities.5 This may be particularly true within transdisciplinary research teams where the effectiveness of collaboration is contingent upon shared understandings (eg, the nature of the research problem, roles of team members, team objectives and translational goals).1 How diverse team members understand and enact the concept and process of knowledge translation (ie, the interactive and iterative process of knowledge creation, sharing and use for better health outcomes, and involving multiple system stakeholders)6 can produce barriers to knowledge creation and knowledge sharing activities conducted within the team. Such barriers may have subsequent downstream effects on the uptake and impact of the knowledge produced.

Barriers to intraorganisational knowledge translation have been studied outside of the health context. For example, Carlile,7 in an ethnographic study of product development, identified three types of boundaries, described as syntactic (eg, language and terminology), semantic (eg, interpretation of knowledge) and pragmatic (eg, the nature of knowledge; organisational politics and culture; roles and responsibilities). Similar boundaries—each with different levels of complexity—are likely to exist in collaborative academic environments.5 Understanding more about such boundaries and resultant barriers to internal knowledge translation activities can inform planning and facilitate collaboration across disciplines.

There is an erroneous tendency to regard academics as homogenous groups with shared understandings of knowledge translation.5 Consequently, little is known about knowledge translation within academic communities, and very little research has explored processes of knowledge translation within transdisciplinary research teams. Since teams are assumed to be working towards a common goal, often focused around effective research communication and translational activities, establishing a stronger theoretical basis for the relationship between transdisciplinary research and knowledge translation is critical.

Transdisciplinary research represents a promising approach for advancing knowledge translation in relation to complex, multifactorial health problems that often exceed the capacity of any single discipline.8 9 In a recent review of transdisciplinary translational research in a biomedical context, Ciesielski et al10 (p. 10)stated that ‘transdisciplinary collaboration can help in some situations, and failing to enhance cross-disciplinary communication and subsequent research approaches may slow down our progress’. Despite the assumed benefits of transdisciplinary research (eg, increased collaboration, diverse assessment, greater relevance to intended end-users), the development of transdisciplinarity often poses considerable challenges to researchers and institutions.1 3 11 Such challenges may relate to divergent knowledge, beliefs and assumptions among team members, or arise through a lack of appropriate infrastructure and support, among other factors.12 Although several studies have outlined models for training and evaluating transdisciplinary collaboration, little empirical evidence exists on whether (and how) transdisciplinary collaboration influences research outcomes, including those typically associated with translation, such as research productivity (eg, number of publications).1 An explanatory theory of how, for whom and under what circumstances transdisciplinary collaboration can impact knowledge translation is necessary to support such processes, and to identify which outcomes are affected by transdisciplinary team approaches in certain contexts.

Findings from this research can guide the implementation of responsive, context-driven strategies to maximise the impact of collaborative efforts across research arenas. With the broader emphasis on the need for transdisciplinary approaches and associated mantra regarding research use and implementation, researchers and practitioners may find utility in such findings. Results will also support the internal functioning of the Centre of Research Excellence (CRE) in Transdisciplinary Frailty Research by knowledge sharing and communication, but will likely be relevant to other practice and research contexts.

Realist evaluation

Realist evaluation is a type of theory-driven evaluation method used to understand if, how, for whom and under what circumstances an intervention ‘works’ to produce an intended outcome.13 We chose this approach because unlike other forms of theory-driven evaluation, realist approaches have a particular focus on understanding how causation works and why programme outcomes work or do not work in different contexts. In realist evaluations, researchers seek to uncover how various contexts (C) work with underlying mechanisms (M) to produce particular outcomes (O), which are theorised through possible CMO interactions or configurations. Such CMO configurations are explanatory pathways, underpinned by implicit theories that can be made explicit through the realist evaluation process.

The philosophical premise of scientific realism distinguishes realist evaluation from other types of theory-driven evaluations.14 Here, reality is both knowable yet relative to the researcher, and actors possess innate capacity for change. Causal mechanisms are embedded in ‘social relationships and contexts as much as individuals’15 (p. 195), which makes realist evaluation a highly appropriate approach to developing an explanation about the impact of transdisciplinary collaboration on knowledge translation within a team setting.

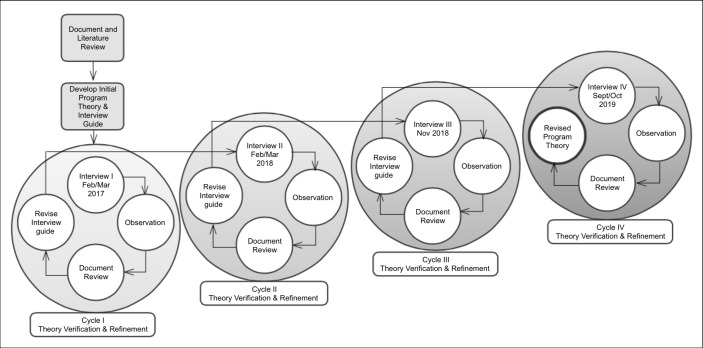

The process of realist evaluation is iterative, cycling between (1) theory development (ie, generating a working theory/hypothesis), (2) theory verification (ie, hypothesis/theory testing throughout data collection), and (3) theory refinement (ie, refining the hypothesis/theory based on emerging data). A middle-range theory is generated, which lies between the working hypothesis and a fully operational, explanatory theory.15 16 Data collection is pragmatic and method-neutral—selection of data sources and methods is guided by what is needed to test the working hypothesis.17

Aims, research questions and objectives

Aims and research questions

The aims of this study are to understand: (i) various perspectives of knowledge translation within a transdisciplinary research team and (ii) if, how, for whom and under what circumstances a transdisciplinary research approach and associated knowledge sharing activities can contribute to a shared understanding of knowledge translation. Our research questions are as follows:

Does transdisciplinary collaboration impact knowledge translation and if so, by which mechanisms is this achieved?

What contextual factors determine whether the identified mechanisms produce their intended outcomes?

In what circumstances (ie, combination(s) of context factors and mechanisms) are transdisciplinary teams most likely to be effective in terms of impacting knowledge translation?

Objectives

To develop an initial programme theory (IPT) of if and how transdisciplinary collaboration impacts knowledge translation.

To iteratively refine the IPT through longitudinal case study research to generate a programme theory for whom, how and why transdisciplinary collaboration impacts knowledge translation.

Methods and analysis

Study design

We will conduct a realist evaluation with an embedded longitudinal case study of the transdisciplinary knowledge translation processes within the CRE, over its approximate lifespan as determined by National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) funding period (2015–2020). Data collected over the course of the study will be used to develop, refine and test programme theories for the relationship between trandisciplinary research collaboration and knowledge translation.

Intervention

We conceptualise the approach used in this research as a ‘naturalistic’ intervention because it does not involve the use of systematic and formal strategies to facilitate knowledge translation. Rather, we use informal, low-level facilitation from knowledge translation researchers. In this study context, we define low-level facilitation as the CRE knowledge exchange activities designed to feedback the teams’ cognitive and behavioural responses related to knowledge translation (eg, current understandings of knowledge translation) following each data collection time point.

Findings may have relevance in other settings where researchers, funders, executive leaders and others assume a positive relationship between transdisciplinary collaboration and impact, and where processes and strategies at different phases of team-based research are not explicit or deliberate.

Data collection

Data collection is underway with the first data cycle completed, and will continue over four rounds of theory development, refinement and testing using the following data sources: interviews, visual data, observation and document review (figure 1). Participants were contacted over email; consent for audio recording of interviews, professional interview transcription and release of any visually generated data was obtained. Verbal consent will be obtained prior to each new data collection cycle.

Figure 1.

Process cycles.

Document review

The CRE NHMRC grant application, the CRE website and a broad range of literature sources pertinent to knowledge translation, collaboration, transdisciplinary teams, organisational management and high-performing teams were reviewed prior to baseline data collection. This literature was used to devise a preliminary working hypothesis and informed the development of an initial interview guide. Between each data collection time point and at the end of the study period, we will review a range of CRE-related documents to provide context and further information to interpret the other data sources. For instance, we will conduct citation counting and case-by-case researcher productivity mapping (eg, number of publications per investigator per year) to allow pre-CRE productivity and post-CRE productivity comparisons. We will work in conjunction with a research librarian to develop a search strategy for identifying literature relevant to transdisciplinary team-based research and knowledge translation. It is anticipated that the search strategy will be iteratively refined over time based on emerging findings. Ongoing sources for document review will include for example team outputs (eg, manuscripts, published abstracts, website updates), management documents (eg, meeting agendas, notes) and research updates (eg, progress reports).

Semi-structured interviews

Semi-structured individual interviews were conducted at baseline (February–March 2017), and will continue at 10-month increments (February–March 2018, November 2018, September–October 2019) with consenting CRE Chief Investigators (CIs), Associate Investigators (AIs), International AIs and active research fellows (ie, purposively sampled based on funding status, research contributions and extent of participation with CRE activities). The initial interview guide was developed based on the IPT, derived from a review of the literature and through consultation with team members. The preliminary interview guide was exploratory, reflecting the emergent state of the IPT and varied somewhat between participants depending on their roles, context and involvement. Data analysis from each data collection time point will be used to refine the working hypothesis and refine the programme theory, and will be reflected through revised interview guides. Interviews will be audio-recorded and conducted in-person for local collaborators. Telephone or video interviews will be conducted with interstate, national and international team members.

In subsequent interviews (cycles 2–4), working programme theories will be presented to participants to provide opportunity to refute, amend and refine working hypotheses relating to team functioning.

Visual data

Visual elicitation will be conducted alongside the semi-structured interviews. We will use visual elicitation based on the premise that visual expression can provide insights into representations and narratives that may be inaccessible using exclusively verbal means.18 In the first visual elicitation exercise, participants will be asked to draw how they understand knowledge translation. The second visual elicitation activity involves asking participants to draw the relationship between transdisciplinary collaboration and knowledge translation. Verbal prompts will be made to inquire into specific aspects of the visualisation during and after its completion.

Observation

Data will be collected through participant observation of various CRE events and meetings. Scheduled events include monthly management meetings (eg, CIs, AIs and some early career researchers in attendance), and mentoring events (eg, early career researchers and mentors in attendance) occurring approximately three times annually. A participant as observer stance will be used, wherein the observing researcher is a participating member of the group under study (ie, the CRE) and the group is aware of the research study and activities.19

Information collected during participant observation will reflect the categories of interest to the study, for instance, how the team perceives knowledge translation and transdisciplinarity and how these understandings and behaviours are reflected during group dynamics. This could include narrative data pertaining to the general areas of study (as highlighted in categories in the baseline interview guide), body language (eg, signs of agreement, disagreement), leadership styles, group dynamics, openness to new ideas or content in what people speak about regarding teamwork or knowledge translation. Observations will be recorded as field notes, and include detailed descriptions of the actions and interactions of participants, with reflexive notes about how participants’ practices might be interpreted in relation to the notions of transdisciplinarity or knowledge translation.20

Sample

Our sample size and frame is directed by the size and composition of the already established CRE, and the study purpose. To understand the role of context on the transdisciplinary collaboration-knowledge translation relationship, we will sample across a breadth of CRE subgroups, including: Australian-based CIs and AIs (n=10); international AIs (n=4); funded postdoctoral research fellows, and graduate students (n=2–4). We project a sample size of 16–20 based on this sampling frame.

Data analysis

Data analysis is iterative and will take place after each data collection time point to generate an explanatory theory via the development of CMO configurations. Ongoing refinement of CMO configurations over time will help focus subsequent data collection in areas of productive inquiry. Although data will be analysed within sources and cases, we will iteratively develop theoretical explanations across cases, consistent with the realist objective of highlighting the conditions and contingencies that affect outcomes.

The main analysis structure will involve mapping of data by context (C) (eg, disciplinary orientations, practice environments), outcome (O) (eg, cognitive and behavioural responses) and mechanisms (M) (eg, hypothesised logic of how change occurs) configurations in relation to the preliminary programme theory. Using this process and through the development and refinement CMO configurations, patterns of outcomes will be identified to determine how particular contexts influence the activation of mechanisms.21 To achieve this, we will analyse qualitative data from interview and document sources, following a coding framework of intervention description, observed outcomes, context conditions and underlying mechanisms.17 Observational data will be coded according to a framework informed by Spradley’s20 dimensions. This coding will be conducted with continual reference to potential CMO configurations that either support or refute the working hypothesis.

Visual data will be inductively analysed by two researchers using a visual content analysis framework, adapted from inductive qualitative approaches used by other researchers and in our previous work.22 23 Using this framework, data are coded according to three overarching components of constituent elements (eg, all components included in the drawing), configuration (eg, positioning of constituent elements relative to one another) and size (in millimetres). The coding framework will be iteratively revised to reflect new categories. Researchers will use a constant comparison method, wherein the coding is continually compared with the framework and with previously coded visual data. Results from the visual content analysis, interview data and document review will be compiled into cross-tabulations and narrative summaries to identify plausible patterns to be circulated back to the emerging programme theory for revision and subsequent testing.

Initial programme theory development

The literature review and first phase of narrative and visual data collection was completed in April 2017. We consulted closely with two experts in knowledge translation (ALK and GH), who were instrumental in eliciting this initial theory. We generated a working hypothesis that transdisciplinary research teams, combined with low-level facilitation from knowledge translation researchers (MMA and ALK) and implemented within a favourable team environment (C) will contribute to a shared perspective of knowledge translation as a collaborative, complex and iterative process (M), and be reflected in behaviours (eg, communication and collaboration methods) and successful implementation of study findings in line with this perspective (O).

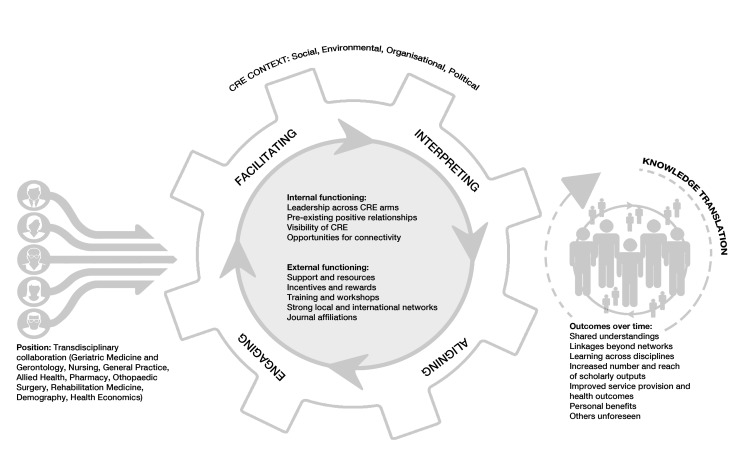

The context for this research is a 5-year NHMRC funded CRE in Transdisciplinary Frailty Research to Achieve Healthy Ageing. The CRE comprises researchers from various disciplines including: nursing, medicine, general practice, demography, orthopedic surgery, pharmacy and health economics. This large-scale collaboration receives institutional support in South Australia and interstate, and involves the consolidation of an international frailty research network. Contextual factors for effective internal and external functioning in this context may include pre-existing positive relationships between team members, leadership across all arms of the CRE, high visibility of the CRE and established clinical and academic partnerships between and beyond investigators and their local and international networks. Potential outcomes include: improved learning across disciplines through copublication, enhanced scholarly output through copublication and copresentation platforms, lateral and vertical learning opportunities, meaningful engagement with multiple stakeholders and the development of diverse links beyond pre-existing networks for greater impact. The initial programme theory is represented visually in figure 2.

Figure 2.

Initial programme theory of transdisciplinary research collaboration on knowledge translation.

We note that this initial programme theory is intended only to provide a provisional structure for the evaluation. We anticipate that additional, as-yet unforeseen contextual factors, mechanisms and outcomes will be identified, and that these will be reflected in ongoing theory expansion, testing and refinement using data collected at each time point.

Discussion, ethics and dissemination

In this paper, we have outlined a realist evaluation protocol for the study of transdisciplinary collaboration and its relationship with knowledge translation, within a 5-year NHMRC funded CRE. The unique integration of data sources, including visual methods, with multiple data-collection time points, are used to provide insight into the organic development of a researcher-clinician team initially designed for research impact. The developmental and longitudinal design provides opportunities for insights into changing group dynamics, methods of enhancing productivity, collaboration and research use, to leverage the potential benefits of transdisciplinary research.

This study commenced in February 2017 and will conclude in December 2020. While participant anonymity cannot be guaranteed given the small sample and use of participant observation, we will take caution to de-identify data, for instance, by generically referring to participant disciplines as ‘medical subspecialties’ rather than using potentially identifiable details (eg, orthopaedic surgery). Participants were explicitly informed of this approach to maintain anonymity prior to commencing their baseline interviews.

Challenges and limitations associated with the chosen methodology may arise; emerging findings should be interpreted in the context of such limitations. Because we are conducting an in-depth evaluation of a single collaborative team, it will not be possible to make claims about the universal transferability of the findings to other settings. We may also encounter practical challenges associated with the collection of observational data (eg, infrequent meetings). Despite these possible limitations, we believe that this evaluation—one of the first internationally to examine the complex relationship between transdisciplinary collaboration and knowledge translation—will provide important insight into team members’ understandings of knowledge translation over time, thereby informing the development of strategies to maximise the effectiveness and impact of collaborative efforts.

Emerging findings will be shared and discussed with team members at scheduled intervals throughout the study by way of verbal, written, and creative reflective approaches (eg, arts elicitation, journalling). This research will be used to help support optimal team functioning by identifying strategies to support knowledge sharing and communication within and beyond the team to facilitate attainment of research objectives. Academic dissemination will occur through publication and presentations across disciplines.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

MMA acknowledges fellowship support received from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

Footnotes

‘Transdisciplinary’, ‘interdisciplinary’ and ‘multidisciplinary’ are often used interchangeably in funding and policy documents, research and practice settings. Transdisciplinary approaches have been generally defined as those that integrate perspectives of multiple disciples and in doing so transcend each traditional disciplinary boundary.24 Transdisciplinary approaches are distinct from multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary approaches, which involve disciplinary interaction, but do not break with disciplinary thinking.25

Contributors: MMA led the design of the study, initial interview schedule, development of the initial program theory, secured ethics approval and led the protocol writing. ML contributed to the initial programme theory, protocol writing and revision. ALK and GH contributed to study design and made important intellectual contributions to the interview schedule, initial programme theory and protocol writing. All authors read, revised and approved the final protocol manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia via funding provided for the Centre of Research Excellence in Transdisciplinary Frailty Research to Achieve Healthy ageing, grant number GNT 1102208.

Competing interests: MMA and ML are NHMRC postdoctoral research officers with the CRE. ALK is a chief investigator with the CRE.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: University of Adelaide Human Research Ethics Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; peer reviewed for ethical and funding approval prior to submission.

References

- 1.Hall KL, Stokols D, Stipelman BA, et al. . Assessing the value of team science: a study comparing center- and investigator-initiated grants. Am J Prev Med 2012;42:157–63. 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.10.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stokols D, Misra S, Moser RP, et al. . The Ecology of Team Science. Am J Prev Med 2008;35:S96–S115. 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Urquhart R, Grunfeld E, Jackson L, et al. . Cross-disciplinary research in cancer: an opportunity to narrow the knowledge-practice gap. Curr Oncol 2013;20:512 10.3747/co.20.1487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Bewer V. Transdisciplinarity in health care: a concept analysis. Nurs Forum 2017;52:339–47. 10.1111/nuf.12200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harvey G, Marshall RJ, Jordan Z, et al. . Exploring the hidden barriers in knowledge translation. Qual Health Res 2015;25:1506–17. 10.1177/1049732315580300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kitson A, Brook A, Harvey G, et al. . Using complexity and network concepts to inform healthcare knowledge translation. Int J Health Policy Manag 2017;6:1–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carlile PR. A pragmatic view of knowledge and boundaries: boundary objects in new product development. Organization Science 2002;13:442–55. 10.1287/orsc.13.4.442.2953 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Austin W, Park C, Goble E. From interdisciplinary to transdisciplinary research: a case study. Qual Health Res 2008;18:557–64. 10.1177/1049732307308514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murphy K, Wolfus B, Loftus A. et al. . From complex problems to complex problem-solving: Transdisciplinary practice as knowledge translation : Kirst M, Schaefer-McDaniel N, Hwang S, O’Campo P, Converging disciplines: a transdisciplinary research approach to urban health problems. Toronto: Centre for Research on Inner City Health, 2011:111–29. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ciesielski TH, Aldrich MC, Marsit CJ, et al. . Transdisciplinary approaches enhance the production of translational knowledge. Transl Res 2017;182:123–34. 10.1016/j.trsl.2016.11.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mâsse LC, Moser RP, Stokols D, et al. . Measuring collaboration and transdisciplinary integration in team science. Am J Prev Med 2008;35(2 Suppl):S151–S160. 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.05.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Archibald MM. Investigator triangulation: a collaborative strategy with potential for mixed methods research. J Mix Methods Res 2016;10:228–50. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pawson R. The science of evaluation: A realist manifesto. London: SAGE, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greenhalgh T, Wong G, Jagosh J, et al. . Protocol--the RAMESES II study: developing guidance and reporting standards for realist evaluation. BMJ Open 2015;5:e008567 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marchal B, van Belle S, van Olmen J, et al. . Is realist evaluation keeping its promise? A review of published empirical studies in the field of health systems research. Evaluation 2012;18:192–212. 10.1177/1356389012442444 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pawson R, Tilley N. An introduction to scientific realist evaluation. London: Sage, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gilmore B, McAuliffe E, Larkan F, et al. . How do community health committees contribute to capacity building for maternal and child health? A realist evaluation protocol. BMJ Open 2016;6:e011885 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Archibald MM, Caine V, Scott SD. Intersections of the arts and nursing knowledge. Nurs Inq 2017;24:e12153 10.1111/nin.12153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kawulich B. Participant observation as a data collection method. Forum Qualitative Social Research 2005;6:2–45. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spradley JP. Participant observation. Minnesota: Holt, Rhinehart & Winston, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marchal B, Van Belle S, Westhop G. Realist Evaluation. Better Evaluation. 2015. http://betterevaluation.org/en/approach/realist_evaluation (accessed Oct 2016).

- 22.Archibald MM, Caine V, Scott SD. The development of a classification schema for arts-based approaches to knowledge translation. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs 2014;11:316–24. 10.1111/wvn.12053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luthy C, Cedraschi C, Pasquina P, et al. . Perception of chronic respiratory impairment in patients' drawings. J Rehabil Med 2013;45:694–700. 10.2340/16501977-1179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Choi BC, Pak AW. Multidisciplinarity, interdisciplinarity and transdisciplinarity in health research, services, education and policy: 1. Definitions, objectives, and evidence of effectiveness. Clin Invest Med 2006;29:351–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ramadier T. Transdisciplinarity and its challenges: the case of urban studies. Futures 2004;36:423–39. 10.1016/j.futures.2003.10.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.